Présidentielles : station “État de Grâce” supprimée

Ex: http://www.dedefensa.org

Dans un texte mêlant dérision et gravité que le New York Times nous restitue en français qui est sa langue du cœur autant que de l’esprit, l’écrivain algérien Boualem Sansal constate : « En France, on change de président tous les cinq ans, mais rien ne change jamais qui vienne vraiment d’eux. » ... On notera que, sans le vouloir précisément même s’il le sait évidemment, l’écrivain a signifié ce nouveau phénomène de la politique française, qui est la durabilité extrêmement réduite des présidents. Depuis Sarko, le président n’est plus réélu même s’il se présente, – et nous pourrions dire jusqu’au paradoxe, “même s’il ne se représente pas”. Nous disons cela comme s’il s’agissait d’une règle nouvelle alors que la démission de De Gaulle, la mort de Pompidou et même l’échec de Giscard de 1981, devraient être considérés comme autant d’avatars accidentels dont certains tragiques. Désormais, ce n’est plus l’accident : la règle semble être devenue, aujourd’hui, que le président est comme un Kleenex, jetable après emploi et qui ne vaut que pour un seul emploi.

(La prochaine étape pourrait être et devrait être, en bonne logique subversive, le président-kleenex impropre à la consommation, jeté avant de s’en servir, bref par interruption du quinquennat pour cause de crise de régime. Macron, le président qui innove en tout, pourrait bien nous apporter également cette “modernisation” décisive de la postmodernité. Il aurait alors bien mérité de la République française, européenne et laïque.)

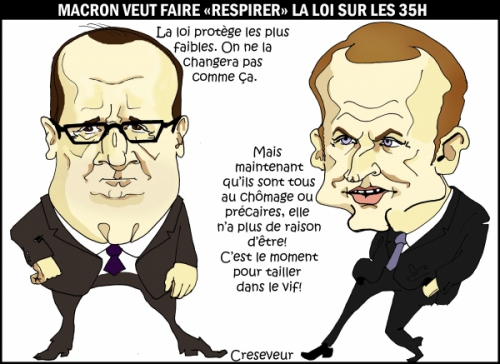

Plus encore et mieux encore, car l’on nous dit, dans le chef de certaines plumes inspirées, qu’il s’agit de l’élection “triomphale” d’un président. (Dixit sans crainte de la réalité des chiffres qui ridiculise la qualification de la performance l’organe de référence du Système ; le quotidien Le Monde dans sa newsletter d’information pour les les lecteurs réticents : « Le triomphe de Macron, les défis du président »)... Eh bien, ce “triomphe” est immédiatement suivie (le lendemain) d’une manifestation de contestation d’une politique d’ores et déjà condamnée avant que d’exister, avec des accusations redoutables (« En marche vers la guerre sociale »), que même les sites US se font un plaisir de détailler, – ZeroHedge.com, par exemple. On ne parle même pas des horions qu’ont aussitôt échangé ceux qui avaient soutenu Macron par inadvertance, et notamment ceux qui, dans cette diversité de circonstance, ont aussitôt proclamé que leur ralliement s’arrêtait là et qu’ils reprenaient aussitôt leur (vraie ?) bataille ; il suffisait d’entendre un Barouin avertissant que tout soutien à Macron pour les législatives signifierait l’exclusion immédiate du fautif du parti LR. Autrement dit, non seulement il n’y a pas d’état de grâce mais il y aurait plutôt un immédiat état de disgrâce qui suivrait, vingt-quatre plus tard, “le triomphe de Macron”.

(Certes, nous avons compris la finesse du titreur qui suit le déterminisme imposé par la narrative [déterminisme-narrativiste]. Le triomphe est celui de l’homme sans équivalent, la pure merveille sortie de la glèbe franco-globalisée qui a réussi cet exploit sans précédent de séduire un peuple entier, – et quel peuple, mazette, selon les statistiques de l’élection, – alors que “les défis” sont ceux de cette fonction suprême que le monde entier nous envie.)

Effectivement, la situation est singulière, le gênant n’étant pas l’élection face à la contestation, mais le “triomphe” de l’élection salué aussitôt par la contestation très organisée par des acteurs sociaux habituels (syndicats) et selon une thématique dont l’extrême est du type “vers la guerre sociale”. L’esprit de la Vème République est bien que l’élection présidentielle constitue effectivement un moment sacré (mais laïque, certes car l’on tient aux contradictions du genre) où un personnage identifié à un parti ou à une tendance devient par la grâce de la fonction, et au moins pour une période symbolique (justement dit-“état de grâce”), le président de “tous les Français” ; Hollande lui-même y avait eu droit bien que fort courtement, c’est dire si l’esprit a le cuir épais et ne meurt pas facilement... La postmodernité a finalement balayé tout cela avec le “président Macron” (il sera difficile de se passer de guillemets) comme déjà l’élection de Trump l’annonçait (quoique d’une façon encore ambiguë tant l’opposition publique, – dans la rue et dans les médias, – était ouvertement organisée, manipulée et financée par des manipulateurs idéologisés). L’élection de Macron inaugure donc une époque nouvelle, ce qui fait d’ailleurs partie de son programme.

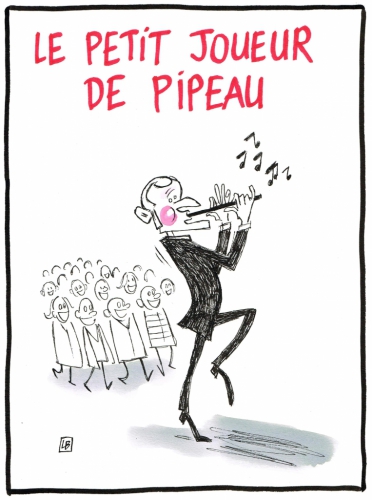

Il est vrai que le texte de Sansal est intéressant par ce mélange de dérision et de gravité, ce qui est au fond parfaitement définir la forme de l’opération. Aux USA, il y a quelques mois, pour l’élection de Trump, ce fut assez semblable si l’on veut bien s’en souvenir, au point que nous jugeâmes judicieux d’inclure dans notre Glossaire.dde l’expression volontairement paradoxale sinon oxymorique de “tragédie-bouffe”. Au fond, ce phénomène de suppression d’un temps d’armistice pour cause d’“état de grâce” qui renvoie à un processus de modernisation et de rentabilisation, – comme l’on supprime les arrêts pour les bus et les trains, et les stations de métro, – signifie simplement que le temps métahistorique ne prend plus de gants, un peu comme s’il disait : “on n’arrête pas une crise en cours, même pour un nouveau président” ; simplement, enfin, parce que le temps métahistorique est également et nécessairement un temps crisique, et que, par conséquent il ne souffre aucune interruption de la crise.

Ainsi avons-nous de ces contradictions presque immédiates, y compris dans le propos et assumées comme telles, qui rendent compte de cette cohabitation du dérisoire et du tragique. Sans en rendre compte par la logique précise de son analyse le commentateur en rend compte effectivement en faisant défiler ces contradictions. Nous ignorons si cela est voulu, mais dans tous les cas cela a la vertu du vrai (d’une vérité-de-situation fondatrice du caractère tragédie-bouffe). Ainsi nous dit-il que les présidents changent et ne changent rien, parce que « la France ne se gouverne plus elle-même », qu’il y a l’Europe qui donne ses consignes et la “mondialisation” (le globalisation) qui fait que « la terre ne tourne plus que dans un sens », celui du « cartel des banques » ; puis il enchaîne aussitôt par la proposition de bon aloi mais tout de même assez paradoxale « Voilà pourquoi il importait que soient débattus durant la campagne présidentielle tous ces thèmes mondialisés... », pour aussitôt émettre la réserve évidente qui explique tout : « Mais ceux-ci ont été à peine évoqués. Peut-être est-ce à cause d’un sentiment d’impuissance face à ces problèmes. »

Ainsi avons-nous de ces contradictions presque immédiates, y compris dans le propos et assumées comme telles, qui rendent compte de cette cohabitation du dérisoire et du tragique. Sans en rendre compte par la logique précise de son analyse le commentateur en rend compte effectivement en faisant défiler ces contradictions. Nous ignorons si cela est voulu, mais dans tous les cas cela a la vertu du vrai (d’une vérité-de-situation fondatrice du caractère tragédie-bouffe). Ainsi nous dit-il que les présidents changent et ne changent rien, parce que « la France ne se gouverne plus elle-même », qu’il y a l’Europe qui donne ses consignes et la “mondialisation” (le globalisation) qui fait que « la terre ne tourne plus que dans un sens », celui du « cartel des banques » ; puis il enchaîne aussitôt par la proposition de bon aloi mais tout de même assez paradoxale « Voilà pourquoi il importait que soient débattus durant la campagne présidentielle tous ces thèmes mondialisés... », pour aussitôt émettre la réserve évidente qui explique tout : « Mais ceux-ci ont été à peine évoqués. Peut-être est-ce à cause d’un sentiment d’impuissance face à ces problèmes. »

... Ce qui fait bouffe encore plus dans cette affaire, bien entendu, c’est qu’on se précipite en désespoir de cause mais pour une si belle cause, jusqu’aux plus extrêmes hystériques contre la chose la plus sérieuse du monde qui est, comme on le sait, la “menace fasciste”. La campagne se fit donc, surtout au second tour, comme si on nous étions en 1924 ou en 1933, ce qui ne gêne pas trop les tenants la globalisation tous comptes faits. Mélenchon s’est vanté, après le résultat final, d’être celui qui avait permis d’arrêter le fascisme (celui de 1924-33, donc) ; bien sûr, puisque c’est lui qui a permis en bonne partie de faire élire l’homme de la globalisation ; la belle intelligence de Mélenchon ne hume-t-elle pas ce que cette contradiction peut avoir de bouffe, à côté de la tragédie ? A peine indirectement, Sansal met cela en évidence lorsqu’il salue plutôt ironiquement le talent rassembleur de Mélenchon (« En tout cas, il a formidablement égayé la campagne. Quel bateleur, quel stratège, ce Jean-Luc! Merci pour ces bons moments »), puis en signale aussitôt la conséquence qui n’est pas des plus habiles (« En affaiblissant les Républicains, le Parti socialiste et le Front national, Mélenchon aura profité à Macron ainsi qu’aux oligarques »). Tout cela crève tellement les yeux que plus personne ne voit distinctement, – ceci explique cela, – que cette bataille si furieuse contre un danger vieux de 80 ans et totalement anéanti dans sa véritable puissance il y a 60 ans est conduite au profit exclusif du seul danger planétaire et sans aucun précédent pour aujourd’hui même. Et pourtant, nombre de ces combattants du passé (les “antifafs”) connaisse parfaitement et dénoncent à mesure l’existence de cette puissance destructrice d’aujourd’hui même qui passe tout puisqu’elle menace le monde lui-même, toutes espèces et idéologies bouffe-fantasmagoriques confondues.

Sans doute se trouve-t-il une frustration secrète de devoir tenir un rôle si faussaire et, en combattant l’ennemi imaginaire, de favoriser non seulement “l’ennemi principal” mais le seul Ennemi possible ; laquelle frustration, à cause de son ampleur, fait souvent tomber le débat “contre le fascisme” dans l’ivresse de l’outrance et du bombastique, – le bruit remplit le vide et écarte les pensées qui pourraient s’aventurer sous l’écume des jours, – qui nous restitue le style tragédie-bouffe qui est le nôtre.

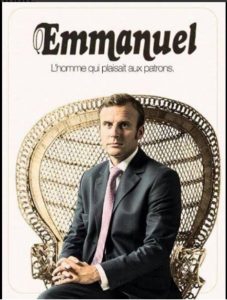

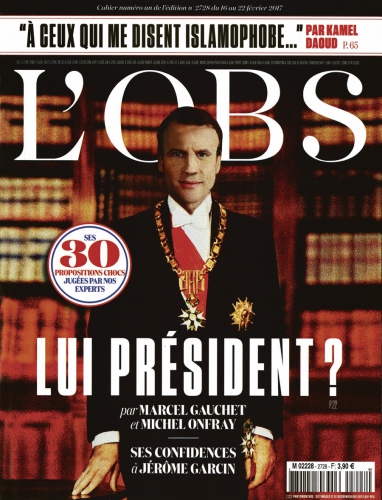

Quoi qu’il en soit, pour les lecteurs avisés, on trouve dans le texte de Sansal plusieurs marques de cette situation attristante. Homme courageux et grand écrivain qui ne craint pas de dénoncer le pouvoir corrompu en Algérie tout en restant sur place au risque des contraintes et des pressions qu’on imagine, Sansal est acclamé par le monde culturel et littéraire (et progressiste-sociétal) français et européen, et les institutions qui vont avec. Il constitue une de ces situations paradoxales si nombreuses où le Système chérie certains critiques de lui-même dans une position spécifique, parce que le jeu de billard pratiqué entre les diverses tromperies et simulacres des situations lui permet tout de même (au Système) d’en tirer avantage du point de vue de la vertu apparente qu’il veut conserver dans le domaine de la communication. Il n’empêche, cet article qui dit une bonne partie de son fait à un nouveau président si exceptionnel par son “triomphe” de jeune homme quasiment “sorti de rien” (les banques, une belle fortune qu’il s’est faite, un an à Bercy mais jamais d’élection, un rassemblement d’influence et de fortunes pour l’encourager de consignes diverses, une presseSystème déchaîné pour le promouvoir et détruire ses adversaires, cela vous donne un innocent aux mains propres, un être d’exception et un “inconnu” vertueux pour une présidentielle), – cet article-là a dû faire penser au Système, où l’on est très strict en ce moment pour maintenir la discipline dans ces moments très difficiles, que la vertu dont on parlait plus haut, dont il a besoin, est parfois payée un peu cher.

Ainsi nous permettons-nous d’emprunter cet article de Boualem Sansal, écrivain, auteur dernièrement de 2084, du 8 mai 2017...

dedefensa.org

La France, état altéré

Il y a du nouveau en France: un nouveau système pour désigner le président de la république. Ni plus réellement une démocratie, ni une dictature, c’est quelque chose qui n’a pas encore de nom. Un acronyme ou un mot porte-manteau construit de «démocratie», «dictature» et «ploutocratie» ferait bien l’affaire.

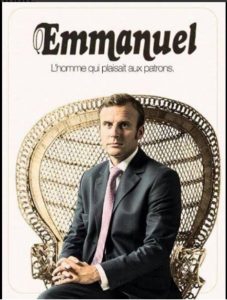

Le mécanisme fonctionne ainsi: des patrons de grands groupes financiers, industriels et commerciaux, ainsi que d’éminents conseillers habitués de l’Elysée, de Matignon et de Bercy ont choisi le futur président de la république — Emmanuel Macron, en l’occurrence — et l’ont instruit de sa mission. Ensuite ces oligarques ont mobilisé l’Etat, le gouvernement, la justice, les médias, les communicants, les artistes, les cachetiers, les sondeurs, les sociétés de Paris et les grands noms de la société civile pour le porter à la magistrature suprême. La machine s’est mise au travail et en un tour de piste a fait de l’impétrant le candidat du peuple, le favori, le héros indépassable. Lui-même en est devenu convaincu.

Le reste était une simple formalité: il suffisait juste d’éliminer les autres candidats. On en a mis beaucoup sur la ligne de départ, désespérant le peuple en lui donnant l’image de la déplorable division dans laquelle les partis politiques ont entrainé le pays. Puis on a promis des primaires pour remédier à ça: il y aura un tri impitoyable! En effet: les candidats sérieux — Manuel Valls, Alain Juppé — ont été éliminés.

Le reste était une simple formalité: il suffisait juste d’éliminer les autres candidats. On en a mis beaucoup sur la ligne de départ, désespérant le peuple en lui donnant l’image de la déplorable division dans laquelle les partis politiques ont entrainé le pays. Puis on a promis des primaires pour remédier à ça: il y aura un tri impitoyable! En effet: les candidats sérieux — Manuel Valls, Alain Juppé — ont été éliminés.

La justice a ensuite lancé des fatwas contre les gros candidats qui restaient, et la presse, bras séculier de l’oligarchie, les a traqués. François Fillon et Marine Le Pen ont été poursuivis pour vol à l’étalage, leurs photos placardées à la une des journaux.

On accuse aussi Jean-Luc Mélenchon de pas mal de crimes. Il aurait assassiné le Parti socialiste, caporalisé les communistes, volé des troupes aux Républicains et aux frontistes et contrevenu aux règles de la soumission en appelant son mouvement La France insoumise.

En tout cas, il a formidablement égayé la campagne. Quel bateleur, quel stratège, ce Jean-Luc! Merci pour ces bons moments. Notre côté romantique invétéré a apprécié ton mot en forme de salut à la veille du premier tour: «Allez, viennent les jours heureux et le goût du bonheur!»

En affaiblissant les Républicains, le Parti socialiste et le Front national, Mélenchon aura profité à Macron ainsi qu’aux oligarques — mais tout en gagnant lui-même aussi. Maintenant, les législatives.

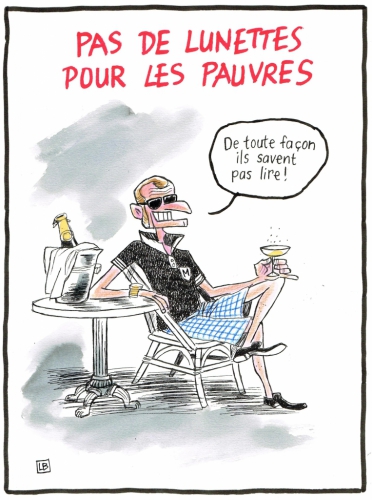

L’autre inconnue dans l’affaire aura été le peuple. Il est trop bête, dit-on; c’est un troupeau angoissé, qui peut réagir n’importe comment. D’ailleurs, le moment est peut-être venu d’en changer. Ce peuple-ci a fait son temps. Il parle encore de de Gaulle, Jaurès, Jeanne d’Arc. C’est vrai qu’il rechigne un peu: dimanche, les électeurs se sont abstenus de voter en nombre record.

Le résultat de ce méli-mélo c’est Macron. Jamais élu auparavant, tête d’un mouvement vieux de juste un an, le voilà président de la République. On ne faisait semblant de douter de son ultime succès que pour écarter la suspicion de manipulation politique. Alors que Fillon a été mis en examen et que la justice française a demandé la levée de l’immunité parlementaire de Le Pen à l’Union européenne, elle a refusé d’ouvrir une enquête sur le patrimoine de Macron, pourtant demandée par de nombreux candidats.

Mais au fond tout ça c’est du frichti, des amusettes, des histoires de carrières personnelles. Valls, Juppé, Le Pen, Fillon, Macron, Mélenchon, Hamon, Tartempion — tout ça c’est pareil, à peu de choses près. En France, on change de président tous les cinq ans, mais rien ne change jamais qui vienne vraiment d’eux.

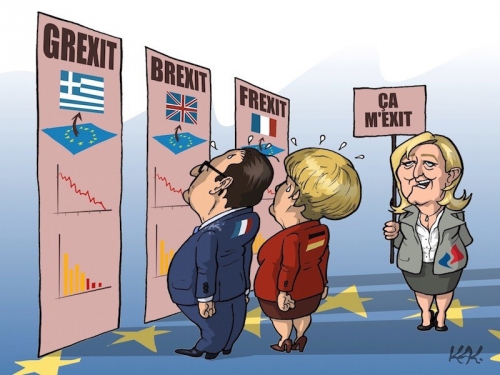

La France ne se gouverne plus elle-même; l’Europe a toujours son mot à dire. La mondialisation fait que la terre ne tourne plus que dans un sens — le sens du cartel des banques, qui a pris le relais du cartel des compagnies pétrolières, qui avait pris le relais du cartel des compagnies minières.

Voilà pourquoi il importait que soient débattus durant la campagne présidentielle tous ces thèmes mondialisés: l’islamisation, le terrorisme, le réchauffement climatique, la migration, l’affaiblissement des institutions multilatérales. Mais ceux-ci ont à peine été évoqués. Peut-être était-ce à cause d’un sentiment d’impuissance face à ces problèmes. Mais le fait de ne pouvoir rien y changer n’est pas une raison de ne pas y regarder.

Cette campagne présidentielle n’aura pas non plus confronté les options stratégiques de la France à moyen et long terme. La France saura-t-elle réinventer ses institutions? Et surtout: saura-t-elle enrayer son déclin? Saura-t-elle retrouver son rôle de moteur de l’Europe, surtout face à l’Allemagne? Cette campagne présidentielle aura été une campagne de gouvernement qui discute de gestion des ressources et d’équilibre des comptes. On a parlé boutique avec quelques accents lyriques pour faire grandiose. Mais tout du long on a plié sous la tyrannie du court-termisme et du pas-de-vague.

A gauche comme à droite, les grands partis d’antan ont été brisés, discrédités. La recomposition politique en France ressemble à un nettoyage par le vide. Entre-temps la fonction présidentielle a aussi été considérablement affaiblie. Merci Nicolas Sarkozy et François Hollande. Macron, héritier d’une fonction qui a été mise au plus bas, va vite découvrir l’étroitesse de sa marge de manœuvre — d’autant plus qu’il sera l’otage de la troupe disparate qui l’a fait arriver là.

Boualem Sansal

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

Ainsi avons-nous de ces contradictions presque immédiates, y compris dans le propos et assumées comme telles, qui rendent compte de cette cohabitation du dérisoire et du tragique. Sans en rendre compte par la logique précise de son analyse le commentateur en rend compte effectivement en faisant défiler ces contradictions. Nous ignorons si cela est voulu, mais dans tous les cas cela a la vertu du vrai (d’une vérité-de-situation fondatrice du caractère tragédie-bouffe). Ainsi nous dit-il que les présidents changent et ne changent rien, parce que « la France ne se gouverne plus elle-même », qu’il y a l’Europe qui donne ses consignes et la “mondialisation” (le globalisation) qui fait que « la terre ne tourne plus que dans un sens », celui du « cartel des banques » ; puis il enchaîne aussitôt par la proposition de bon aloi mais tout de même assez paradoxale « Voilà pourquoi il importait que soient débattus durant la campagne présidentielle tous ces thèmes mondialisés... », pour aussitôt émettre la réserve évidente qui explique tout : « Mais ceux-ci ont été à peine évoqués. Peut-être est-ce à cause d’un sentiment d’impuissance face à ces problèmes. »

Ainsi avons-nous de ces contradictions presque immédiates, y compris dans le propos et assumées comme telles, qui rendent compte de cette cohabitation du dérisoire et du tragique. Sans en rendre compte par la logique précise de son analyse le commentateur en rend compte effectivement en faisant défiler ces contradictions. Nous ignorons si cela est voulu, mais dans tous les cas cela a la vertu du vrai (d’une vérité-de-situation fondatrice du caractère tragédie-bouffe). Ainsi nous dit-il que les présidents changent et ne changent rien, parce que « la France ne se gouverne plus elle-même », qu’il y a l’Europe qui donne ses consignes et la “mondialisation” (le globalisation) qui fait que « la terre ne tourne plus que dans un sens », celui du « cartel des banques » ; puis il enchaîne aussitôt par la proposition de bon aloi mais tout de même assez paradoxale « Voilà pourquoi il importait que soient débattus durant la campagne présidentielle tous ces thèmes mondialisés... », pour aussitôt émettre la réserve évidente qui explique tout : « Mais ceux-ci ont été à peine évoqués. Peut-être est-ce à cause d’un sentiment d’impuissance face à ces problèmes. » Le reste était une simple formalité: il suffisait juste d’éliminer les autres candidats. On en a mis beaucoup sur la ligne de départ, désespérant le peuple en lui donnant l’image de la déplorable division dans laquelle les partis politiques ont entrainé le pays. Puis on a promis des primaires pour remédier à ça: il y aura un tri impitoyable! En effet: les candidats sérieux — Manuel Valls, Alain Juppé — ont été éliminés.

Le reste était une simple formalité: il suffisait juste d’éliminer les autres candidats. On en a mis beaucoup sur la ligne de départ, désespérant le peuple en lui donnant l’image de la déplorable division dans laquelle les partis politiques ont entrainé le pays. Puis on a promis des primaires pour remédier à ça: il y aura un tri impitoyable! En effet: les candidats sérieux — Manuel Valls, Alain Juppé — ont été éliminés.

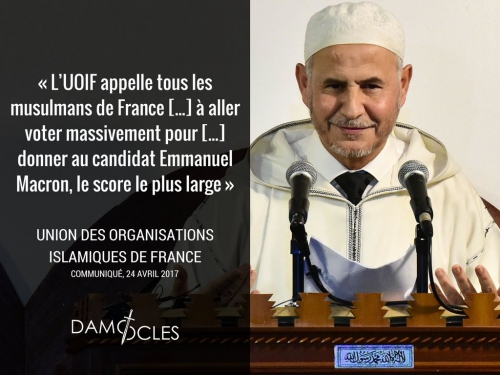

En vérité, les jeux sont faits, parce que Macron est tout ce qu’on veut : de gauche, de droite, du centre, hétéro, homo, gendre idéal, fils rêvé, intello, pragmatique, « prodige », marié avec sa mère, mais pas encore père, et tout dévoué pour finir d’évacuer l’idée de nation française dans un « espace France » ouvert au grand rut migratoire et à la soumission. Macron est vide ; mais c’est un vide sémillant, donc acceptable. Macron n’est qu’un Fillon qui a 25 ans de moins que l’ex-candidat de la droite officielle, pour qui il était impossible de voter, me dit une amie, depuis qu’on avait appris que ses discours étaient réécrits par une ordure telle que Macé-Scaron. Ce simple fait en dit long sur la décomposition morale d’une France où les musulmans s’apprêtent à voter pour Macron – raison suffisante pour ne pas le soutenir, me dit encore cette amie ; car partager un bulletin de vote avec un musulman est non seulement une faute, mais une soumission au muezzin du totalitarisme mondialisé.

En vérité, les jeux sont faits, parce que Macron est tout ce qu’on veut : de gauche, de droite, du centre, hétéro, homo, gendre idéal, fils rêvé, intello, pragmatique, « prodige », marié avec sa mère, mais pas encore père, et tout dévoué pour finir d’évacuer l’idée de nation française dans un « espace France » ouvert au grand rut migratoire et à la soumission. Macron est vide ; mais c’est un vide sémillant, donc acceptable. Macron n’est qu’un Fillon qui a 25 ans de moins que l’ex-candidat de la droite officielle, pour qui il était impossible de voter, me dit une amie, depuis qu’on avait appris que ses discours étaient réécrits par une ordure telle que Macé-Scaron. Ce simple fait en dit long sur la décomposition morale d’une France où les musulmans s’apprêtent à voter pour Macron – raison suffisante pour ne pas le soutenir, me dit encore cette amie ; car partager un bulletin de vote avec un musulman est non seulement une faute, mais une soumission au muezzin du totalitarisme mondialisé.

RT France :

RT France :

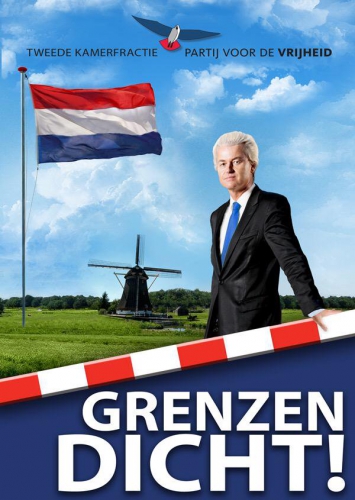

De Particratie (Aspekt 2016) is een werk van de aanstormende intellectueel Arnout Maat. Vanuit zijn achtergrond in geschiedenis, politicologie en politieke communicatie presenteert hij een relaas over het huidige politieke bestel. De essentie is dat politieke partijen al een eeuw lang een véél grotere rol spelen in de representatieve democratie dan ooit door onze grondwet is bedoeld. “De particratie van binnenuit omvormen to een democratie, zoals D66 ooit poogde te doen, is onmogelijk: alsof men een rijdende auto probeert te repareren”, zo vat Maat zijn relaas op de achterflap samen.

De Particratie (Aspekt 2016) is een werk van de aanstormende intellectueel Arnout Maat. Vanuit zijn achtergrond in geschiedenis, politicologie en politieke communicatie presenteert hij een relaas over het huidige politieke bestel. De essentie is dat politieke partijen al een eeuw lang een véél grotere rol spelen in de representatieve democratie dan ooit door onze grondwet is bedoeld. “De particratie van binnenuit omvormen to een democratie, zoals D66 ooit poogde te doen, is onmogelijk: alsof men een rijdende auto probeert te repareren”, zo vat Maat zijn relaas op de achterflap samen.

La confortable victoire de Radev - ancien chef de l'armée de l'air soutenu par les socialistes (PSB, ex-communiste) - par près de 60% des suffrages, a sonné comme un désaveu cinglant pour le premier ministre au pouvoir depuis fin 2014, qui soutenait pour sa part la candidature de la présidente du Parlement, Tsetska Tsatcheva. Roumen Radev a notamment bénéficié du mécontentement suscité par le gouvernement de centre-droit dont les efforts en matière de lutte anti-corruption et de réorganisation du secteur public auront été jugés trop lents. Cette victoire traduit également un «contexte international qui encourage la volonté de changement», selon Parvan Simeonov, directeur de l'institut Gallup, qui cite «l'écroulement des autorités traditionnelles en Europe occidentale» et l'élection de Donald Trump, aux États-Unis.

La confortable victoire de Radev - ancien chef de l'armée de l'air soutenu par les socialistes (PSB, ex-communiste) - par près de 60% des suffrages, a sonné comme un désaveu cinglant pour le premier ministre au pouvoir depuis fin 2014, qui soutenait pour sa part la candidature de la présidente du Parlement, Tsetska Tsatcheva. Roumen Radev a notamment bénéficié du mécontentement suscité par le gouvernement de centre-droit dont les efforts en matière de lutte anti-corruption et de réorganisation du secteur public auront été jugés trop lents. Cette victoire traduit également un «contexte international qui encourage la volonté de changement», selon Parvan Simeonov, directeur de l'institut Gallup, qui cite «l'écroulement des autorités traditionnelles en Europe occidentale» et l'élection de Donald Trump, aux États-Unis. La victoire annoncée d’Igor Dodon, candidat ouvertement prorusse à l’élection présidentielle moldave, a bien eu lieu. Dimanche soir 13 novembre, les premiers résultats donnaient au dirigeant du Parti des socialistes moldaves un score de 56,5 %, contre 43,5 % à sa rivale pro-européenne, Maia Sandu. Celle-ci a pu espérer un miracle avec une participation en forte hausse chez les jeunes, mais elle n’améliore que peu son résultat de 38 % obtenu lors du premier tour le 30 octobre. M. Dodon, lui, avait rassemblé 47 % des suffrages.

La victoire annoncée d’Igor Dodon, candidat ouvertement prorusse à l’élection présidentielle moldave, a bien eu lieu. Dimanche soir 13 novembre, les premiers résultats donnaient au dirigeant du Parti des socialistes moldaves un score de 56,5 %, contre 43,5 % à sa rivale pro-européenne, Maia Sandu. Celle-ci a pu espérer un miracle avec une participation en forte hausse chez les jeunes, mais elle n’améliore que peu son résultat de 38 % obtenu lors du premier tour le 30 octobre. M. Dodon, lui, avait rassemblé 47 % des suffrages.

Face à Clinton donc, mais face aussi aux caciques du parti républicain qui l’ont attaqué à chaque prétendu dérapage, Paul Ryan et John McCain en tête, alors qu’il était désavoué par les Bush et combattu par les néo-conservateurs, et que même Schwarzenegger s’est dégonflé, ne bénéficiant dès lors que du soutien explicite de Clint Eastwood et de Steven Seagal, et du soutien implicite des Stallone, Willis, Norris et autres acteurs des films d’action, il a vaincu. Il a remporté les primaires, humiliant les Kasich et les Jeb Bush. Il a su obtenir le ralliement de Ted Cruz, son adversaire le plus déterminé mais qui, une fois vaincu, s’est montré ensuite d’un soutien sans faille. Il a su conserver le soutien aussi de Priebus, le président du parti républicain, face aux manœuvres des Romney et Ryan qui voulaient au mépris du vote des citoyens le renverser.

Face à Clinton donc, mais face aussi aux caciques du parti républicain qui l’ont attaqué à chaque prétendu dérapage, Paul Ryan et John McCain en tête, alors qu’il était désavoué par les Bush et combattu par les néo-conservateurs, et que même Schwarzenegger s’est dégonflé, ne bénéficiant dès lors que du soutien explicite de Clint Eastwood et de Steven Seagal, et du soutien implicite des Stallone, Willis, Norris et autres acteurs des films d’action, il a vaincu. Il a remporté les primaires, humiliant les Kasich et les Jeb Bush. Il a su obtenir le ralliement de Ted Cruz, son adversaire le plus déterminé mais qui, une fois vaincu, s’est montré ensuite d’un soutien sans faille. Il a su conserver le soutien aussi de Priebus, le président du parti républicain, face aux manœuvres des Romney et Ryan qui voulaient au mépris du vote des citoyens le renverser.