jeudi, 13 janvier 2022

La noologie : la discipline philosophique des structures de l’esprit

La noologie : la discipline philosophique des structures de l’esprit

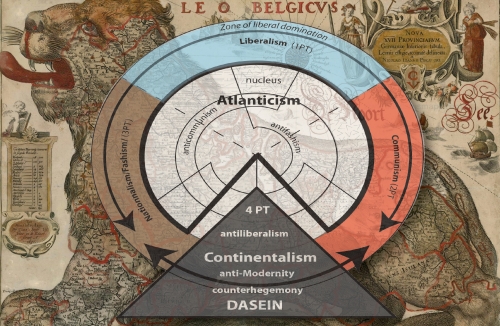

Plan des cours de noologie/noomachie donnés par Alexandre Douguine

Cours # 1. Introduction.

- La noologie est la science de la multiplicité de la pensée humaine.

La base philosophique de la multipolarité.

La réflexion des cultures sur elles-mêmes et le territoire d’un possible dialogue et polylogue.

La noologie est la base essentielle de la Théorie du Monde Multipolaire et de la Quatrième Théorie Politique.

- La noologie se préoccupe de concepts à niveaux multiples qui incluent :

- la philosophie

- l’histoire des religions

- la géopolitique

- l’histoire du monde

- la sociologie

- l’anthropologie

- l’ethnosociologie

- la théorie de l’imagination

- la phénoménologie

- le structuralisme.

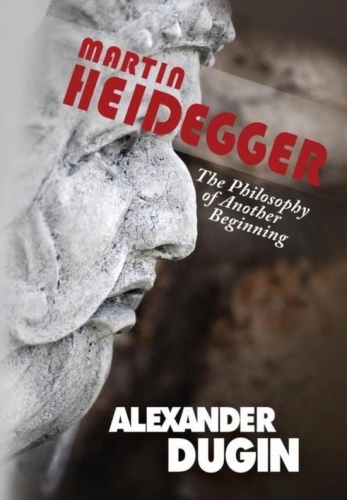

- Elle utilise l’analyse existentielle de Heidegger, le traditionalisme (Guénon, Evola), les concepts de Bachofen, le structuralisme de Dumézil et Lévi-Strauss.

- Le concept principal est le Noûs – mot grec pour Intellect, Intelligence, Esprit, Pensée, Conscience. Il est uni en lui-même et représente l’Humain. Le Noûs est l’Humain. La pensée est un Homme. Tout ce qui appartient exclusivement à l’être humain est la Pensée. Tout le reste, l’homme le partage avec d’autres.

- Le Noûs est triple. Il peut exister en tant que tel ; il existe à travers ses figures, ses formes, ses manifestations. La noologie nomme ces manifestations : le Logos.

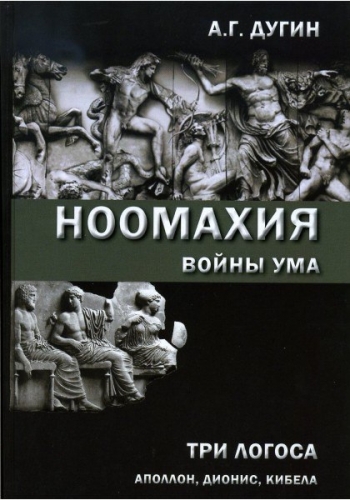

- L’idée basique de la noologie est : il y a trois Logos principaux qui contiennent des variantes innombrables.

- Le Logos d’Apollon. Définition – Lumière. Verticalité. Pur patriarcat. Androcratie. Le concept de Gilbert Durand – le régime diurne. Le jour, le Ciel. Le platonisme. Le Dieu Père. La Loi. La ligne droite. Le mouvement de haut en bas.

- Le Logos de Dionysos. Définition. Clair-obscur, aube, dualité, dialectique. Terre et Ciel. Paire. Homme et femme. Androgyne. La danse. Le rythme. Le cercle. La courbe.

- Le Logos de Cybèle. La Grande Mère. Le matriarcat. La Terre et l’enfer. Ce qui est souterrain, le Tartare. Hadès. Matérialisme, croissance, progrès. Mouvement de bas en haut.

- Le principe essentiel de la noomachie : trois Logos sont en conflit insoluble, ils se combattent. Ils combattent pour la forme de Noûs qui dominera la culture.

Le combat des trois Logos est la clé pour la structure interne de la culture, de la civilisation et de l’identité de la société. Et l’explication des relations interethniques et interculturelles. La noomachie explique tout ce qui est humain, et explique comment l’humain explique ce qui n’est pas humain.

Introduction à la Noomachie. Cours # 2. Géosophie.

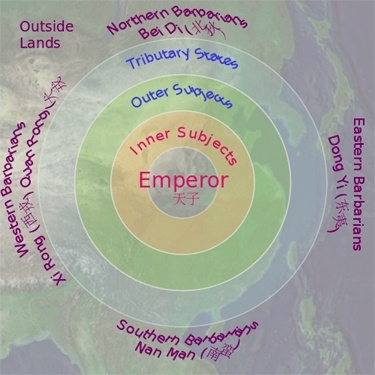

- La géosophie est le domaine d’application de la noologie (le principe de la noomachie) pour l’étude des cultures, des peuples et des civilisations. C’est le plus profond niveau de l’ethnosociologie.

- L’idée basique de la géosophie est qu’il y a des organisations différentes de l’équilibre des trois Logos qui définissent l’identité de la société humaine concrète. La culture apollinienne, la culture de Cybèle, etc.

- La société où le Logos domine peut changer de forme dans l’espace et dans le temps. L’équilibre de la noomachie peut changer aussi. Ici c’est Apollon qui règne, là c’est Cybèle. Ou bien c’est Dionysos qui domine, et Apollon lui fait contrepoids. Donc la noomachie est essentiellement dynamique, c’est un processus.

- Les frontières des peuples ou des cultures au moment de la noomachie dans l’espace sont définies comme horizon existentiel. C’est une structure à niveaux multiples, proche du concept de Dasein. C’est la base du peuple, ses racines. Le Logos est bâti et fondé sur l’horizon existentiel. C’est l’espace vivant. Da-sein, être-là dans le monde concret organisé à l’aide du Logos dominant. Donc c’est aussi l’espace onto-logique. Il n’y a pas d’espace universel. L’espace est existentiel et compris et étudié à travers le Logos dominant.

- Les frontières des peuples ou des cultures au moment de la noomachie dans le temps sont définies comme l’Historique (pas l’historique). Le terme français est : l’historial. C’est ainsi qu’Henry Corbin a traduit le terme heideggérien de Seynsgeschichtliche ou simplement de das Geschichtliche par opposition à das Historische. Donc l’histoire des peuples est définie par le Logos dominant. L’histoire n’est pas la conséquence de faits mais la conséquence de significations, de sens. L’histoire est une chaîne sémantique, une structure. Donc dans l’histoire – comme histoire sémantique ou sur l’histoire, l’histoire de l’être – nous pouvons retracer la manifestation du Logos dominant. Il n’y a pas de temps universel. Le temps est existentiel et compris et étudié à travers le Logos dominant.

- Le principe essentiel de la géosophie est le perspectivisme. Nous n’avons pas affaire à un espace et un temps uniques, différemment compris par des temps et des espaces différents, parce qu’ils n’ont pas d’existence en-dehors de leur interprétation dans le contexte d’une culture concrète, factuelle. Nous pensons autrement simplement parce que nous sommes sous l’influence écrasante de la culture moderne (au sens historique) et occidentale (au sens de l’horizon existentiel). Nous croyons que la compréhension occidentale moderne de la nature de l’espace et du temps est universelle. Tout homme d’un espace et d’un temps particuliers croit la même chose. C’est l’ethnocentrisme.

- La géosophie ne combat pas l’ethnocentrisme : sans lui, il n’y a pas d’humain. Etre ethnocentrique est la même chose qu’avoir le Da dans le Dasein, être-là. Le Da est défini par l’ethnos – l’éthique, la culture, le peuple, la langue. Mais la géosophie reflète la nature ethnocentrique de toute pensée. C’est donc du perspectivisme : il n’y a pas un monde unique, il y a de nombreux mondes emboîtés les uns dans les autres – autant qu’il y a de peuples. Nous ne pouvons pas être et penser sans une structure culturelle qui soit ethnocentrique. Nous devons pleinement comprendre cela.

- La géosophie en tant que perspectivisme n’est pas anti-ethnocentrique : elle est anti-raciste et anti-universaliste. Nous acceptons la pluralité de l’ethnocentrisme comme quelque chose de factuel, donné comme une condition inévitable. Mais nous devons fixer des frontières ou des limites. L’universalisme est en lui-même titanique. Il tente de dépasser les frontières d’Apollon. L’hybris est le péché essentiel des titans, il est excessif. Donc l’ethnocentrisme est légitime tant qu’il reconnaît ses limites. Quand il sort de ses frontières, il devient raciste et universaliste. Et donc il perd sa légitimité.

Introduction à la Noomachie. Cours # 3. Le Logos de la civilisation indo-européenne.

- L’espace existentiel et ses classes. Grands et petits espaces existentiels. Le facteur linguistique. Le langage comme maison de l’être.

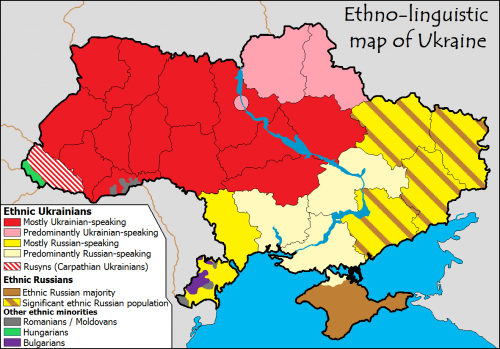

- Le plus grand espace existentiel. L’espace indo-européen. Le Dasein indo-européen. Les frontières.

- Qu’est-ce que le Touran ? Iran et Touran chez Firdûsî. L’ancien nom de l’Avesta. Peuple nomade indo-européen et peuple sédentaire indo-européen.

- La mère-patrie indo-européenne. Le Berceau des Indo-Européens. Touran et Eurasie. La théorie des kourganes de Maria Gimbutas. Les trois civilisations d’Oswald Spengler : atlantique, kouchite et touranienne.

- La structure du Logos indo-européen. Le patriarcat. La théorie de George Dumézil. Les trois fonctions.

• prêtres : Apollon

• guerriers : Apollon/Dionysos

• simples éleveurs : Apollon/Dionysos – plus matériels. - L’« idéologie » indo-européenne est basée sur trois fonctions. Tous les mythes, contes, récits historiques, institutions politiques, religions et rites sont basés sur la logique trifonctionnelle.

- Pure verticalité. Le Père est transcendant. Le Fils est immanent. Il n’y a pas d’antagonisme entre eux.

- Le monde indo-européen est nomade. Mais il y a le centre qui est éternel. La mère-patrie sacrée.

- Le symbole du soleil – le cercle, la roue. La roue solaire. Le char.

- Platon – les trois mondes du Timée : paradigmes, images et khora – la matière. Les trois espèces de la « République » : Prêtres-philosophes, gardiens, auxiliaires, assistants – guerriers et producteurs. Le Phédon : l’âme a trois principes: le cheval noir (epithymia), le cheval blanc (le thumos), et le conducteur du char (kybernautos).

- La triade est présente chez tous les peuples indo-européens – Hittites, Germains, Celtes, Grecs, Thraces, Latins, Slaves, Baltes, Iraniens, Indiens, Illyriens, Arméniens, etc.

- Mais le problème est que la troisième fonction est représentée par les paysans sédentaires, les fermiers. Ils furent intégrés dans les sociétés indo-européennes il y a longtemps. Ainsi ils devinrent la troisième fonction avec les pasteurs/éleveurs.

Ici c’est la Terre elle-même qui se manifeste. Dionysos est maintenant la vigne, la grappe de raisin.

Introduction à la Noomachie. Cours # 4. Le Logos de Cybèle.

- Les guerriers indo-européens envahirent les peuples sédentaires, dont la plupart vivaient dans une société matriarcale. Maria Gimbutas. Bachofen.

- Le concept de paléo-européen. La population européenne avant l’arrivée des guerriers touraniens.

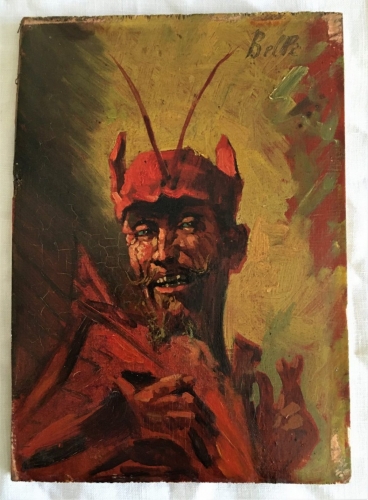

- Les principaux centres de la civilisation matriarcale étaient en Anatolie et dans les Balkans. C’était l’ancienne civilisation de Cybèle. La Déesse Mère avait différents noms, mais le même Logos. La naissance et la mort. Donc l’absence de traits sur le visage et la tête de la Déesse était le signe que cela n’avait pas d’importance. Il y avait seulement un Pouvoir de manifestation.

- La Déesse était immanente, chtonienne, terrestre. Les figures mâles étaient absentes. Mais il y avait des animaux – surtout deux, de chaque coté de la Grande Mère. Ensuite ils se transformèrent en une figure mi-bête, mi-humaine. Ils appartenaient à la Grande Mère.

- La figure d’Attis. Il y avait l’androgyne femelle Agdytis qui avait donné naissance à un beau jeune homme. Cybèle était tombée amoureuse de ce jeune. Mais il voulait épouser une femme terrestre. Cybèle jalouse lui envoya la folie. Il se castra et mourut. Cybèle le ressuscita. Il devint le prêtre de la Déesse – le sort de l’homme dans le monde de Cybèle.

- Un autre type de figure mâle dans le monde de la Grande Mère est le Titan. C’est une créature chtonienne avec des traits de serpent montant à l’assaut du Ciel. Le Dragon.

- Le matriarcat n’est pas la version féminine de la domination masculine (indo-européenne). C’est un type particulier de société basé sur l’euphémisation, l’utilisation des euphémismes. La mort est la vie, l’obscurité est la lumière, la douleur est la joie, le passif est actif. Le régime nocturne dans la sociologie de l’imagination de Gilbert Durand.

- La paysannerie. La paysannerie était basée sur le pouvoir de la Terre de créer l’épi de blé, la tige de la plante. Les premiers fermiers étaient des femmes travaillant comme auxiliaires de naissance (doula) plutôt que cultivateur. Le principal outil était la houe, pas la charrue. Aucun animal n’était utilisé, ni cheval ni bœuf.

- Donc la paysannerie correspond au matriarcat paléo-européen.

- Quand les envahisseurs indo-européens surgirent du Touran et entrèrent en Anatolie et dans les Balkans, ils rencontrèrent la Grande Mère – Chatal-Hüyuk , Lepenski Vir, Vincha. Ce fut le moment décisif de la noomachie. Le combat des dieux célestes et des déités chtoniennes.

Le résultat de la bataille fut l’apparition de la paysannerie européenne. La Mère fut détrônée et soumise. La société mixte apparut. F.G. Jünger dit que l’ordre divin est créé sur les corps des Titans vaincus. Il n’est pas créé sur le vide. Il est basé sur la nature subordonnée de la Grande Mère.

Introduction à la Noomachie. Cours # 5. Le Logos de Dionysos.

- La superposition de deux horizons existentiels crée un champ noologique de titanomachie. Le Logos d’Apollo affronte le Logos de Cybèle dans la troisième fonction – dans la culture de la paysannerie européenne.

- C’est le moment de Dionysos. Le raisin et le blé. Court-circuit. Bachofen explique Dionysos comme étant la forme de la victoire patriarcale sur la société agraire matriarcale. Le Ciel devient immanent. Dans l’histoire de Dionysos, il y a l’épisode de l’appel de Dionysos. C’est le moment où les bacchantes entendent son appel lointain et deviennent folles. C’est la folie de la présence mâle.

- Dionysos est le dieu du cycle agraire. C’est le dieu de l’intégration de Cybèle dans l’horizon existentiel indo-européen.

- Le culte de Dionysos n’a pas de traits particuliers : tous les symboles et les rites de Dionysos sont empruntés au culte de la Grande Mère. On les appelle les rites pré-dionysiaques. K. Kerenyi et Vyach. Ivanov consacrèrent d’importantes études à cet aspect. Le pré-dionysiaque est cybélien. Dans le culte de Dionysos, il y a une interprétation patriarcale du culte matriarcal.

- Dans les mystères d’Eleusis, Dionysos est la figure principale avec Déméter. La vigne et le pain, venant du blé. C’est le culte agrarien transformé, par la présence de Dionysos, en culture paysanne mâle.

- La figure de Déméter n’est pas la même que Cybèle. Déméter est la Mère domestiquée, intégrée dans le patriarcat, dans la hiérarchie des trois fonctions. Il y a la Mère souterraine (Cybèle) et la Mère en surface – le sol cultivé soumis au Père céleste. Dionysos est la semence.

- Dans le contexte néoplatonicien, Dionysos est l’esprit détourné par les titans et présent chez les hommes en tant qu’étincelle de la conscience. Le but est de restaurer l’intégrité de Dionysos.

- Un Dionysos transcendantal dans l’hénologie de Plotin ?

- Le double de Dionysos. La figure de Dionysos dans la perspective de Cybèle est son double obscur. Cybèle voit la figure de Dionysos comme Attis, comme Adonis. C’est un simulacre matériel et chtonien de Dionysos.

- Le niveau de Dionysos est l’espace où la noomachie atteint son moment le plus intense. Ici le Logos d’Apollon touche le Logos de Cybèle. C’est un monde intermédiaire, l’imaginaire.

Dans la structure des sociétés sédentaires indo-européennes – si mélangées ! –, la zone de Dionysos devient le lieu essentiel pour la décision métaphysique. Dionysos est le Dasein à l’état pur.

www.geopolitica.ru

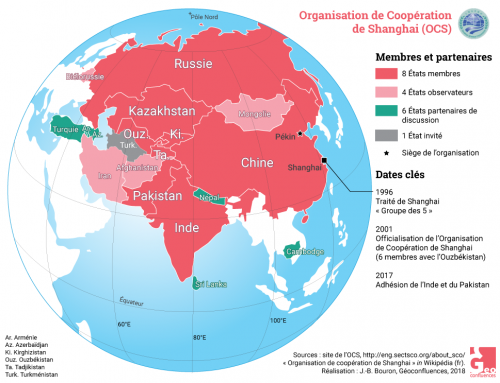

Geopolitica.ru est une plateforme pour une surveillance continue de la situation géopolitique dans le monde, basée sur l’application des méthodes de la géopolitique classique et postclassique. Le portail suit la ligne de l’approche eurasienne. Le groupe analytique coopère étroitement avec le Mouvement Eurasien International, ainsi qu’avec le Centre d’Expertises Géopolitiques, le Centre d’Etudes Conservatrices et certains anciens membres du think-tank Katehon.

10:53 Publié dans Nouvelle Droite | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : nouvelle droite, nouvelle droite russe, alexandre douguine, noologie, noomachie |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

mercredi, 12 janvier 2022

Alexandre Douguine: textes sur les événements du Kazakhstan

Alexandre Douguine: textes sur les événements du Kazakhstan

Tout ce qui se passe au Kazakhstan est le prix à payer pour s'être éloigné de Moscou

Alexandre Douguine

Source: https://www.geopolitica.ru/article/aleksandr-dugin-vsyo-proishodyashchee-v-kazahstane-cena-za-otdalenie-ot-moskvy

Les autorités kazakhes sont en partie responsables de la crise et de la tentative de coup d'État du début de l'année 2022. La Russie doit fournir à la république toute l'aide possible mais non pas gratuitement et seulement sous certaines conditions, déclare le politologue, leader du Mouvement international eurasien et philosophe Alexandre Douguine. Dans une interview accordée à Tsargrad, Douguine ne se contente pas de nommer la voie de sortie de la crise et les raisons de celle-ci mais répond également à la question de savoir ce que la Russie doit faire dans cette situation.

Une tentative de s'asseoir sur trois chaises

Tsargrad : Alexandre G. Douguine, quelles sont, selon vous, les principales raisons des troubles, des tentatives de prise de pouvoir et des actes de terrorisme au Kazakhstan ?

Alexandre Douguine: Il est nécessaire de comprendre que la politique internationale du Kazakhstan ces dernières années était basée sur une relation trilatérale - avec la Chine, avec la Russie et avec l'Occident. Et tant Nazarbayev, qui est l'architecte de cette politique, que Tokayev, qui est le successeur de Nazarbayev, ont estimé que cette "triple orientation" ne laisserait aucune de ces puissances mondiales devenir hégémonique et prédéterminer complètement la politique du Kazakhstan de l'extérieur.

Si les Américains exercent trop de pression, le Kazakhstan a recours à Moscou et, sur le plan économique, à la Chine. Quand la Russie a trop avancé ses pions - au contraire, l'anglais a été enseigné dans les écoles et l'économie chinoise a pénétré le pays de plus en plus profondément. Lorsque la Chine a commencé à parler de ses prétentions à prendre le contrôle de cette puissance plutôt faible économiquement, les facteurs américains sont revenus sur le tapis.

Il s'agissait d'une politique multisectorielle. C'était assez efficace à l'époque. Mais elle était différente de l'initiative eurasienne, que Nursultan Nazarbayev avait lui-même formulée dans les années 1990. En fait, l'équilibre entre multipolarité et unipolarité, entre l'Occident, la Chine et la Russie, s'est avéré très fragile du point de vue politique.

Couleur ou noir et blanc ?

- On entend beaucoup dire maintenant que la tentative de coup d'État a été largement inspirée de l'extérieur, que nous sommes confrontés à une nouvelle "révolution orange", que c'est simplement le tour du Kazakhstan. Pensez-vous que c'est vrai ?

- La politique tripartite du Kazakhstan a eu des résultats négatifs. Mais le plus important est que cette politique est allée à l'encontre de la déclaration d'unification de l'espace eurasien - principalement avec la Russie et avec les autres pays de l'EurAsEC et de l'OTSC. Nazarbayev et son successeur Tokayev ont ralenti de nombreux processus d'intégration. Bien que l'eurasisme ait été formellement déclaré comme l'objectif à poursuivre.

La rupture de l'intégration a rendu les relations avec Moscou problématiques. Environ le même modèle a été utilisé par Minsk. Et tout comme Lukashenko a obtenu ainsi sa révolution de couleur, maintenant le Kazakhstan, Tokayev et Nazarbayev ont obtenu leur propre révolution de couleur! Cela a été rendu possible parce que l'Occident a été autorisé à pénétrer trop profondément au Kazakhstan. Et bien sûr, il a fait son travail habituel.

Il est certain que ce à quoi nous avons affaire au Kazakhstan est une révolution de couleur. Du point de vue géopolitique, il s'agit d'une extension du front occidental contre la Russie. L'Occident, comme il le dit lui-même, a peur de l'invasion de l'Ukraine par la Russie et de la renaissance de la Novorossia, le "printemps russe". Pour déjouer l'attention et disperser la volonté de la Russie, des attaques sont lancées le long du périmètre - non seulement en Ukraine, mais aussi au Belarus et en Géorgie.

Et maintenant, un autre front de l'Atlantisme s'ouvre contre l'Eurasisme, au Kazakhstan. Bien sûr, cette opération est dirigée contre la Russie. Les manifestants ont déjà avancé les thèses évooquant la nécessité pour le Kazakhstan de quitter l'Union économique eurasienne. C'est une révolution de couleur typique, parrainée par l'Occident à des fins géopolitiques, comme toutes les autres.

Tsargrad est prévenu ! Petit rappel: Alexei Toporov, en 2018, disait que "Nazarbayev finirait comme Ianoukovitch et Chevardnadze".

Les problèmes internes du Kazakhstan

- Au Kazakhstan, les gens considèrent que la crise est due à des problèmes internes de la république. Nous comprenons qu'ils sont là, mais lesquels, à votre avis, ont eu un impact significatif ?

- Les problèmes intérieurs sont le troisième facteur après la politique étrangère et l'ingérence occidentale. Ensuite, il y a certainement un conflit qui se forme au Kazakhstan entre Tokayev et Nazarbayev. Nazarbayev veut - il serait plus correct de dire qu'il voulait - contrôler toute la politique, tandis que Tokayev se sent progressivement plus indépendant. Il n'est donc pas exclu que le président kazakh lui-même soit derrière ces protestations.

Les premiers jours, nous avons assisté à une étrange réaction : le renvoi du gouvernement, l'ouverture de négociations avec les manifestants. Seul un dirigeant qui a un certain intérêt à ce que l'effondrement et la crise se poursuivent peut le faire. Peut-être que sur cette vague, Tokayev lui-même cherche à se débarrasser de Nazarbayev, celui qui l'a porté au pouvoir.

Le quatrième facteur est la situation sociale et économique problématique du Kazakhstan. L'absence de politique sociale, le caractère fermé des élites, l'absence d'une idée nationale et la transformation de l'eurasisme déclaré en un simulacre d'idéologie - tout cela a conduit à une société plutôt corrompue au Kazakhstan, où l'élite est intégrée à l'Occident et garde son argent dans des sociétés offshore.

La situation au Kazakhstan est typique

- Dans une certaine mesure, ces problèmes ont touché toutes les républiques post-soviétiques ?

- Bien sûr, ces régimes post-soviétiques ont cependant épuisé leur potentiel. Tôt ou tard, ils devront être remplacés par quelque chose. L'Occident veut qu'ils soient remplacés par un processus de désintégration et de démocratie libérale contrôlé par lui.

Tous les États de l'espace post-soviétique ont enfait moins d'une semaine d'existence. Ils ont vécu au sein d'un système unique au cours des derniers siècles - l'Empire russe, puis l'Union soviétique. Et maintenant, ils sont subitement devenus de nouvelles formations politiques.

Pratiquement aucun de ces États n'a jamais existé dans ses frontières actuelles. Ce sont des frontières conditionnelles, des frontières administratives. Par conséquent, pour s'établir en tant qu'État, il doit d'abord établir une relation avec Moscou, le principal facteur de stabilité et de prospérité.

En fait, au Kazakhstan ou dans toute autre république post-soviétique, il est tout à fait possible de créer un système efficace, orienté vers le peuple, avec une idée nationale et une idéologie multipolaire. D'autant plus que l'eurasisme est très populaire au Kazakhstan. Ils ont très bien commencé, de manière très convaincante. Et il n'y a pas eu de gros problèmes avec la population russe, et les relations avec Moscou sont restées bonnes. À un moment donné, il semblait que le Kazakhstan était l'antithèse de l'espace post-soviétique : si l'un des Etats post-soviétiques avait du succès, c'était le Kazakhstan. Mais il s'est avéré que la simple incohérence d'un eurasisme de pure déclaration émis par Nazarbayev a joué un tour cruel au Kazakhstan.

Plus loin de Moscou, plus près des problèmes

- Pour quelle raison la situation au Kazakhstan a-t-elle radicalement changé ?

- À un moment donné, les autorités kazakhes ont considéré Moscou comme un partenaire secondaire, même si elles ont continué à utiliser certains modèles économiques. Au lieu de promouvoir l'intégration, ils l'ont parfois sabotée. Si, dans un premier temps, Nazarbayev a été le créateur de ce modèle eurasien, construit sur les principes de l'Union européenne, et a été à l'avant-garde des processus d'intégration, il s'est progressivement retiré de ce rôle.

Ainsi, au lieu d'une intégration eurasienne efficace et d'un rapprochement avec Moscou, on a assisté à des processus de corruption de plus en plus nationaux et paroissiaux.

Je connais Nazarbayev personnellement. J'ai écrit un livre sur lui, j'ai une très bonne relation avec lui. Et jusqu'à un certain point, Nazarbayev avait une compréhension brillante de l'eurasisme. Il a construit sa politique exactement sur ce principe : si nous sommes d'accord avec Moscou, nous vivrons heureux pour toujours, tout ira bien. Si nous suivons l'intégration eurasienne, tout ira bien. Nazarbayev a écrit un article merveilleux et brillant sur la multipolarité monétaire. Nous défendons les grands espaces, nous défendons l'identité grande-eurasienne, une civilisation indépendante: dans ce cas, le Kazakhstan prospérera.

Mais dès qu'ils s'en éloignent, dès que les petites élites commencent à se battre entre elles pour certains aspects de l'économie, dès que l'argent est retiré du pays pour disparaître dans des zones offshore, alors les fonds occidentaux et les valeurs occidentales commencent à pénétrer dans le pays, et la langue anglaise commence à remplacer le russe. Une telle orientation ne relève pas du tout de l'eurasisme. Et vous en récolterez les fruits dans ce cas.

La Russie doit aider, mais pas sans raison

- Il s'avère que le Kazakhstan, à un moment donné, s'est apparemment détourné de la Russie. Que doit donc faire Moscou maintenant pour rétablir la stabilité et ne pas permettre une répétition de la situation actuelle ?

- Je pense que la Russie devrait aider le Kazakhstan à maintenir l'ordre. Nous devons contribuer à préserver l'intégrité territoriale du Kazakhstan, nous devons soutenir les dirigeants actuels, mais pas pour rien. Nous devons poser une condition très stricte : si nous vous aidons, alors vous devez en finir avec l'orientation à trois vecteurs, vous suivez strictement votre idée eurasienne - et nous nous intégrerons pour de bon. Alors nous vous aiderons.

Nous ne devons pas oublier que la Russie est le garant de l'intégrité territoriale de tous les États post-soviétiques. Cela a été prouvé à de nombreuses reprises. Si la Russie ne remplit pas cette fonction, si elle n'est pas appelée à préserver son intégrité territoriale, alors cette intégrité territoriale est attaquée. Nous le voyons en Moldavie, en Géorgie, en Ukraine, en Azerbaïdjan.

Ceux qui ignorent la Russie en tant que principal gardien de l'intégrité territoriale du pays, gardien qui a le plus de principes, en paient le prix.

- La Russie doit donc agir, mais sans les bonnes politiques du Kazakhstan, ce ne sera pas possible ?

- Oui. Si les dirigeants kazakhs ne peuvent garantir la poursuite du processus d'intégration et d'allégeance à la ligne eurasienne, la situation s'aggravera. Le sort de l'intégrité territoriale du Kazakhstan sera remis en question.

Bien sûr, la Russie n'est pas derrière tout cela. La Russie est précisément la victime de cette agression. Mais je pense que la Russie a déjà épuisé la limite historique pour tolérer toutes ces hésitations à la Ianoukovitch. La politique de Loukachenko a fini par hésiter elle aussi, mais la Russie ne le tolère tout simplement plus.

Si vous êtes nos amis, vous n'êtes pas seulement nos amis, mais aussi les ennemis de nos ennemis. C'est ce qu'on appelle une alliance eurasienne. Et si c'est le cas, ayez la courtoisie d'agir en conséquence dans le cadre des traités et dans la sphère internationale.

Si vous êtes membres de l'OTSC, alors les Américains devraient sortir du Kazakhstan. Pas un seul Américain, pas un seul représentant de l'OTAN, de l'UE. Si c'est le cas, nous vous aiderons dans toute situation difficile - non seulement sur le plan militaire, mais aussi sur le plan économique, politique et social. Mais si vous cherchez un endroit où vous serez mieux payé ou où vous ferez de meilleures affaires, je suis désolé. Cela ne s'appelle ni un partenaire, ni un ami, ni un frère - cela porte un autre nom.

Il est temps d'abandonner le mot "économique" de l'Union économique eurasienne. D'ailleurs, les mêmes Kazakhs ont déjà insisté sur ce point antérieurement. Nous devrions simplement parler de l'Union eurasienne comme d'un nouvel État confédéral. L'intégration eurasienne elle-même est mise à l'épreuve dans la situation du Kazakhstan. Oui, nous devons certainement soutenir le Kazakhstan. Mais pas pour rien.

https://tsargrad.tv/articles/aleksandr-dugin-vsjo-proishodjashhee-v-kazahstane-cena-za-otdalenie-ot-moskvy_474087

Reconquista eurasienne

Alexandre Douguine

Ex: https://www.geopolitica.ru/article/evraziyskaya-rekonkista

Les troubles au Kazakhstan ont mis en exergue le problème de l'espace post-soviétique à l'attention de tous. Il est clair qu'il doit être traité de manière globale. L'escalade des relations avec l'Occident au sujet de l'Ukraine et de la prétendue "invasion russe", ainsi que les "lignes rouges" définies par Poutine, font partie de ce contexte géopolitique.

Que voulait dire Poutine par ces "lignes rouges"? Il ne s'agit pas simplement d'un avertissement selon lequel toute tentative d'étendre la zone d'influence de l'OTAN vers l'est, c'est-à-dire sur le territoire post-soviétique (ou post-impérial, ce qui revient au même), entraînera une réponse militaire de Moscou. Il s'agit d'un refus de reconnaître le statu quo stratégique établi après l'effondrement de l'URSS, ainsi que d'une remise en question de la légitimité de l'adhésion des États baltes à l'OTAN et, par conséquent, de l'ensemble de la politique américaine dans cette zone. M. Poutine est clair : "Lorsque nous étions faibles, vous en avez profité et vous nous avez pris ce qui, historiquement, nous appartenait logiquement et à nous seuls ; maintenant, nous nous sommes remis de la folie libérale et des tendances atlantistes traîtresses des années 1980 et 1990 au sein même de la Russie et nous sommes prêts à entamer un dialogue à part entière en position de force. Il ne s'agit pas d'une simple revendication. La thèse est confirmée par des étapes réelles - Géorgie 2008, Crimée et Donbass 2014, la campagne de Syrie. Nous avons rétabli notre position dans certains endroits, et l'Occident ne nous a rien fait - nous avons fait face aux sanctions. Ni les menaces de provoquer une révolte des oligarques contre Poutine ni celles de déclencher une révolution de couleur au nom des libéraux de la rue (la 5ème colonne) n'ont fonctionné. Nous avons consolidé nos succès de manière sûre et inébranlable.

La Russie est maintenant prête à poursuivre la Reconquista eurasienne, c'est-à-dire à éliminer définitivement les réseaux pro-américains de toute notre zone d'influence.

Dans l'ensemble de la géopolitique, l'aspect juridique de la question est secondaire. Les accords et les normes juridiques ne font que légitimer le statu quo qui émerge au niveau du pouvoir. Les perdants n'ont pas leur mot à dire, "malheur à eux". Les gagnants, par contre, ont ce droit. Et ils l'utilisent toujours activement. Que le pouvoir qui s'impose aujourd'hui, sera le pouvoir juste demain. C'est ça le réalisme.

Sous la direction de M. Poutine, la Russie est passée d'un statut de looser en politique internationale à celui d'un des trois pôles complets du monde multipolaire. Et Poutine a décidé que le moment était venu de consolider cette position. Être un pôle signifie contrôler une vaste zone qui se situe parfois bien au-delà de ses propres frontières nationales. C'est pourquoi les bases militaires américaines sont dispersées dans le monde entier. Et Washington et Bruxelles sont prêts à défendre et à renforcer cette présence. Non pas parce qu'ils en ont le "droit", mais parce qu'ils le veulent et le peuvent. Et puis la Russie de Poutine apparaît sur leur chemin et leur dit : stop, il n'y a pas d'autre chemin ; de plus, vous êtes priés de réduire votre activité dans notre zone d'intérêt dès que possible. Toute puissance faible, pour avoir fait de telles déclarations, aurait été détruite. Poutine a donc attendu avec eux pendant 21 ans jusqu'à ce que la Russie retrouve sa puissance géopolitique. Nous ne sommes plus faibles. Vous ne le croyez pas ? Essayez de vérifier.

Tout ceci explique la situation autour du Belarus, de l'Ukraine, de la Géorgie, de la Moldavie et maintenant du Kazakhstan. En fait, le moment est venu pour Moscou de déclarer le changement de nom de la CEI en Union eurasienne (non seulement économique, mais réelle, géopolitique), comprenant toutes les unités politiques de l'espace post-soviétique. Les russophobes les plus obstinés peuvent être laissés dans un statut neutre - mais toute la zone post-soviétique devrait être nettoyée de la présence américaine. Elle devrait être éliminée non seulement sous la forme de bases militaires, mais aussi dans le cadre d'éventuelles opérations de changement de régime, dont la version la plus courante sont les "révolutions de couleur" - comme le Maïdan de 2013-2014 en Ukraine, les manifestations de 2020 en Biélorussie et les derniers développements au Kazakhstan au tout début de 2022.

L'Occident s'insurge contre notre soutien à Loukachenko, contre la prétendue "invasion" de l'Ukraine et, maintenant, contre l'envoi de troupes de l'OTSC au Kazakhstan pour réprimer les insurrections terroristes, islamistes, nationalistes et gulénistes, que, comme on pouvait s'y attendre, l'Occident soutient - comme il soutient ses autres mandataires - de Zelensky et Maia Sandu à Saakashvili, Tikhanovskaya et Ablyazov. En d'autres termes, les États-Unis et l'OTAN se soucient de ce qui se passe dans l'espace post-soviétique, et ils fournissent toutes sortes de soutien à leurs clients. Et Moscou, pour une raison quelconque, selon leur logique, ne devrait pas s'en soucier. C'est vrai, si Moscou n'était qu'un objet de la géopolitique et gouverné de l'extérieur, comme c'était le cas dans les années 90 sous la domination pure et simple de la 5ème colonne atlantiste dans le pays, plutôt qu'un sujet comme aujourd'hui, alors ce serait le cas. Mais le moment décisif est venu de consolider ce statut de sujet. C'est maintenant ou jamais.

Qu'est-ce que cela signifie ?

Cela signifie que Moscou met fin à l'interminable processus d'intégration eurasienne par un accord d'action plus décisif. Si Washington n'accepte pas de garantir le statut de neutralité de l'Ukraine, alors - pour citer Poutine - elle devra répondre militairement et techniquement. Si vous ne voulez pas une bonne réponse, ce n'est pas comme ça que ça marche. D'autres scénarios vont de la libération complète de l'Ukraine de l'occupation américaine et du régime libéral-nazi corrompu et illégitime, à la création de deux entités politiques à sa place - à l'Est (Novorossia) et à l'Ouest (sans la Podkarpattya ruthène). Mais en aucun cas moins. Et aucune reconnaissance de la DPR et de la LPR, bien sûr, ne sera suffisante. La "finlandisation" de l'Ukraine, dont notre sixième colonne a souvent parlé ces derniers temps, ne sera pas non plus achevée tant qu'il n'y aura pas un argument vraiment fort - c'est-à-dire une nouvelle entité non indépendante - sur ce territoire, toute la rive gauche, ainsi qu'Odessa et les provinces adjacentes.

Oui, la décision est impopulaire, mais historiquement inévitable. Lorsque la Russie est dans une spirale ascendante (et c'est là qu'elle se trouve actuellement), les régions occidentales sont inévitablement - tôt ou tard - libérées de la présence atlantiste - polonaise, suédoise, autrichienne ou américaine. C'est une loi géopolitique.

Un tel exemple serait une grande leçon pour la Géorgie et la Moldavie : soit vous neutralisez, soit nous venons à vous. Et c'est tout. L'exemple des pays voisins permet de voir comment nous y parvenons. Et il vaut mieux ne pas tenter le sort - la Géorgie est passée par là sous Saakashvili. La tentative d'Erevan de flirter avec l'Occident s'est soldée par le feu vert donné par Moscou à Bakou pour restaurer son intégrité territoriale. Et puis nous avons la Transnistrie. Les signes sont partout. Et c'est seulement à Moscou de déterminer dans quel état ils se trouvent. Aujourd'hui, Poutine perd patience face aux provocations continues de l'Occident. Il est possible de décongeler un produit congelé. Et ce ne sera pas un petit prix à payer.

Maintenant le Kazakhstan. Nazarbayev a bien commencé - mieux que les autres, et même mieux que la Russie elle-même, qui était aux mains de l'agence atlantiste dans les années 90. C'est lui qui a avancé l'idée de l'Union eurasienne, de l'ordre mondial multipolaire, de l'intégration eurasienne, et qui a même rédigé la Constitution de l'Union eurasienne. Hélas, ces dernières années, il s'est éloigné de sa propre idée. Nazarbayev m'a un jour promis personnellement lors d'une conversation qu'après sa retraite, il dirigerait le Mouvement eurasien, car c'était son destin. Mais au cours des dernières années de son gouvernement, pour une raison quelconque, il s'est tourné vers l'Occident et a soutenu la nationalisation des élites kazakhes. Les agents de l'Atlantisme n'ont pas manqué d'en profiter et, par l'intermédiaire de leurs mandataires - islamistes, gulénistes et nationalistes kazakhs, ainsi qu'en utilisant l'élite libérale kazakhe cosmopolite - ont commencé à préparer un "plan B" pour renverser Nazarbayev lui-même et son successeur Kassym-Jomart Tokayev. Le plan a été lancé début 2022, juste avant les entretiens fatidiques de Poutine avec Biden, dont dépendra le sort de la guerre et de la paix.

Dans une telle situation, Moscou devrait apporter à Tokayev son soutien militaire total. Mais les demi-mesures du Kazakhstan en matière de politique d'intégration - Glazyev montre en détail et objectivement comment elle est sabotée au niveau des mesures concrètes par nos partenaires de l'UEE - ne sont plus acceptables. Tout comme l'hésitation de Lukashenko. Les Russes (OTSC) font, volens nolens, partie du Kazakhstan et y resteront. Jusqu'à ce que les terroristes soient éliminés, et en même temps, jusqu'à ce que tous les obstacles à une intégration complète et véritable soient levés. Et que l'Ouest fasse autant de bruit qu'il le veut ! Ce n'est pas son affaire : nos alliés nous ont invités à sauver le pays. Mais toutes les fondations et structures occidentales, ainsi que les cellules des organisations terroristes (tant libérales qu'islamistes et gulénistes) au Kazakhstan doivent être abolies et écrasées.

Lorsque la guerre nous est déclarée et qu'il n'y a aucun moyen de l'éviter, nous n'avons plus qu'à la gagner. Par conséquent, l'UEE ou, pour être plus précis, une Union eurasienne à part entière doit devenir une réalité. Minsk et la capitale du Kazakhstan, quel que soit son nom, ainsi qu'Erevan et Bichkek, doivent prendre conscience qu'elles font désormais partie d'un seul et même "grand espace". Il s'agit des amis et des problèmes qu'ils rencontrent sous l'influence de l'atlantisme, qui tente par tous les moyens possibles de saboter et de démolir les régimes existants - bien que relativement pro-russes. Ces problèmes prendront fin au moment où l'intégration deviendra réelle.

Dans ce cas, c'est le côté militaire qui s'avère être le plus efficace en la matière. Les Russes ne sont pas forts en négociations, mais ils se montrent meilleurs dans une guerre de libération juste - défensive, en fait, qui leur est imposée.

Ensuite, nous en arrivons logiquement aux États baltes. Leur présence au sein de l'OTAN, compte tenu du nouveau statut de la Russie en tant que pôle du monde tripolaire, est une anomalie. Il faut également leur proposer un choix : neutralisation ou... Laissez-les découvrir par eux-mêmes ce qui se passera s'ils ne choisissent pas volontairement la neutralisation.

Enfin, l'Europe de l'Est. La participation de ses pays à l'OTAN est également un gros problème pour la Grande Russie. Nombre de ces pays sont profondément liés à nous : certains par le slavisme, d'autres par l'orthodoxie, d'autres encore par leurs origines eurasiennes. En un mot, ce sont nos peuples frères. Et voici l'OTAN... Ce n'est pas une bonne chose. Il serait préférable qu'ils soient un pont amical entre nous et l'Europe occidentale. Et il n'y aurait pas besoin de Nord Stream 2. Notre peuple sera toujours d'accord avec son propre peuple. Mais non. Aujourd'hui, ils jouent le rôle d'un "cordon sanitaire" - un outil classique de la géopolitique anglo-saxonne, conçu pour séparer l'Europe centrale et l'Eurasie russe. De temps en temps, les vrais pôles déchirent ce cordon. Aujourd'hui, elle est temporairement revenue aux Anglo-Saxons. Mais si la montée en puissance de la Russie, comme sujet géopolitique, se poursuit, ce ne sera pas pour longtemps.

Cependant, les pays baltes et l'Europe de l'Est sont l'agenda géopolitique de demain. Aujourd'hui, le destin de l'espace post-soviétique - post-impérial - est en jeu. Notre maison commune eurasienne. La première tâche consiste à y mettre de l'ordre.

12:18 Publié dans Actualité, Eurasisme, Géopolitique | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : alexandre douguine, actualité, géopolitique, politique internationale, kazakhstan, asie centrale, eurasie, eurasisme, russie, asie, affaires asiatiques |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

samedi, 08 janvier 2022

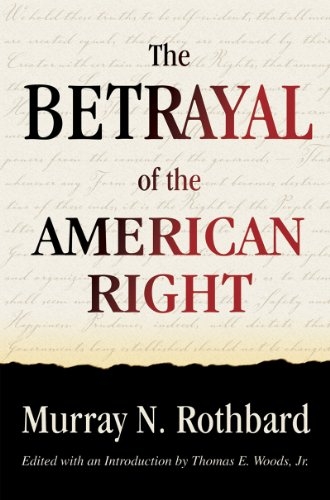

Recension: Alexandre Douguine, Contre le Great Reset, le Manifeste du Grand Réveil

Recension: Alexandre Douguine, Contre le Great Reset, le Manifeste du Grand Réveil

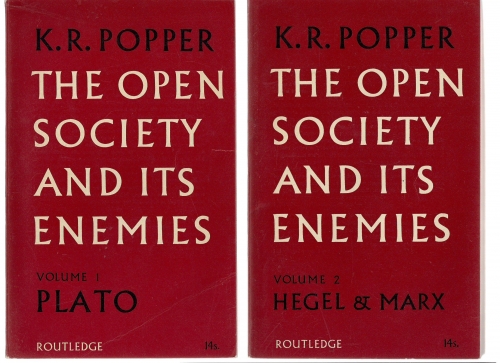

Alexandre Douguine, Contre le Great Reset, le Manifeste du Grand Réveil, Ars Magna, 2021, pp. 70, € 15,00

par Claudio Mutti

En réponse au projet de ce qu'on appelle le Great Reset, projet présenté en mai 2020 par le prince Charles d'Angleterre et le directeur du Forum économique mondial, Klaus Schwab, Alexandre Douguine avance la "thèse du Grand Réveil" (p. 37). L'usage anglais de ce terme, Great Awakening, n'est nullement accidentel: il désigne les différents mouvements de renouveau qui ont eu lieu aux 18e et 19e siècles dans le monde protestant et est actuellement en grande circulation dans les milieux trumpistes, tant protestants que catholiques. ("Que peuvent faire concrètement les Fils de Lumière du Grand Réveil?" a demandé l'archevêque pro-Trump Carlo Maria Viganò à l'agitateur bien connu Steve Bannon).

En fait, le Grand Réveil, explique Douguine lui-même, "vient des États-Unis, de cette civilisation dans laquelle le crépuscule du libéralisme est plus intense qu'ailleurs" (p. 47); et l'intensité de ce crépuscule serait démontrée, selon Douguine, précisément par le phénomène représenté par Donald Trump, "un centre d'attraction pour tous ceux qui étaient conscients du danger venant des élites mondialistes" (p. 37). De plus, poursuit Douguine, "un rôle important dans ce processus a été joué par l'intellectuel américain d'orientation conservatrice Steve Bannon" (p. 37), qui, selon Douguine, a été "inspiré par d'éminents auteurs antimodernes tels que Julius Evola, de sorte que son opposition au mondialisme et au libéralisme avait des racines assez profondes" (p. 37). (Sur la prétendue inspiration évolienne de l'agit-prop américain, voir AA. VV., Deception Bannon, CinabroEdizioni, 2019, passim).

Selon la conception géopolitique qui caractérisait la pensée d'Alexandre Douguine avant que Donald Trump ne devienne président des États-Unis, si l'Eurasie se trouve exposée à l'agression continue de l'expansionnisme américain, cela est dû au fait que la puissance américaine est poussée vers la conquête du pouvoir mondial par sa propre nature thalassocratique (et non simplement par l'orientation idéologique d'une partie de sa classe politique). Puis, adoptant un critère conditionné davantage par des abstractions idéologiques que par le réalisme géopolitique, Douguine a indiqué que l'"ennemi principal" n'était plus les États-Unis d'Amérique, mais le globalisme libéral ; c'est ainsi qu'il a accueilli avec enthousiasme la relève de la garde à la présidence américaine, archivant en même temps ses plus de vingt ans d'anti-américanisme. "Pour moi, déclarait Douguine en novembre 2016, il est évident que la victoire de Trump a marqué l'effondrement du paradigme politique mondialiste et, simultanément, le début d'un nouveau cycle historique (...). À l'ère de Trump, l'antiaméricanisme est synonyme de mondialisation (...) l'antiaméricanisme dans le contexte politique actuel devient une partie intégrante de la rhétorique de l'élite libérale elle-même, pour qui l'arrivée de Trump au pouvoir a été un véritable coup dur". Pour les adversaires de Trump, le 20 janvier [2017] était la 'fin de l'histoire', alors que pour nous, il représente une porte vers de nouvelles opportunités et options".

Cette position n'a cessé d'être soutenue et développée par Douguine tout au long de la présidence de Donald Trump ; et si ce dernier (à qui Douguine a souhaité "Quatre années de plus" le jour même de l'assassinat du général Soleimani) a dû renoncer à une répétition du mandat présidentiel, "le trumpisme est bien plus important que Trump lui-même, c'est à Trump que revient le mérite de lancer le processus". Maintenant, nous devons aller plus loin (Now we need to go further)". C'est ce que l'on peut lire dans un article de Douguine du 9 janvier 2021 intitulé Great Awakening : the future starts now (www.geopolitica.ru), dans lequel l'auteur répète : "Notre combat n'est plus contre l'Amérique".

Le présent Manifeste du Grand Réveil constitue donc une reconfirmation de la position de Douguine, inaugurée avec le tournant pro-Trumpiste d'il y a cinq ans. On y répète en effet la thèse selon laquelle ce ne sont pas les États-Unis qui représentent l'ennemi fondamental de l'Eurasie: "Ce n'est pas l'Occident contre l'Orient, ni les États-Unis et l'OTAN contre tous les autres, mais ce sont les libéraux contre l'humanité - y compris cette partie de l'humanité qui se trouve sur le territoire même de l'Occident" (p. 40). Dans l'affrontement idéologique esquissé par Douguine, le présage le plus favorable est vu dans le fait que le Grand Réveil a été annoncé sur le sol américain: "Le fait qu'il ait un nom, et que ce nom soit apparu à l'épicentre même des transformations idéologiques et historiques aux États-Unis, dans le contexte de la défaite dramatique de Trump, de la prise désespérée du Capitole et de la vague croissante de répression libérale, (...) est d'une grande (peut-être cruciale) importance. (p. 49).

12:50 Publié dans Actualité, Eurasisme, Livre, Livre, Nouvelle Droite | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : actualité, politique internationale, livre, alexandre douguine, claudio mutti, eurasisme, nouvelle droite, nouvelle droite russe |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

vendredi, 07 janvier 2022

La condition postmoderne chez Alexandre Douguine

La condition postmoderne chez Alexandre Douguine

par Luca Leonello Rimbotti

Source : Italicum & https://www.ariannaeditrice.it/articoli/la-condizione-postmoderna-in-alexandr-dugin

La nécessité de donner une réponse à la décadence de l'Europe impose à toute sorte de contre-culture de passer au crible toutes les possibilités offertes par l'histoire, la géographie et la pensée européennes, afin de façonner de nouvelles idées, de nouvelles solutions ou, comme on dit mieux, une "nouvelle synthèse" des valeurs anciennes. L'objectif est de remettre sur pied à tout prix une civilisation qui a été désintégrée de manière presque irréversible par l'hégémonie politique de la "gauche" cosmopolite corrosive. Dans un tel contexte, Alexandre Douguine représente l'un des rares moments idéologiques où la pensée européenne de l'an 2000 a pu se donner une physionomie et un objectif et est désormais en mesure de constituer une alternative qui ne soit pas seulement hypothétique. Avec lui, il s'agit de voir ce qu'il est possible de faire, après que la pensée de l'homme blanc, disons, s'est épuisée en quelques siècles de tension politique continue, atteignant finalement, avec la prédominance actuelle du globalisme des Lumières, la phase finale de la crise de l'Occident, qu'il y a un siècle Spengler signalait avec son pronostic précoce.

À vrai dire, pour Douguine, il s'agit en réalité d'une sortie de l'Occident et de la signification même de l'Occident, rendu méconnaissable et même hostile à une véritable Europe, précisément en raison de son identification désormais totale avec l'atlantisme et les politiques capitalistes-internationalistes. Comme ce fut le cas, il y a plusieurs décennies, dans le processus d'évolution politique qui a conduit à la Seconde Guerre mondiale, penser l'Europe comme un anti-Occident et comme la reconquête d'un patrimoine autochtone signifie planifier un choc idéologique planétaire, capable de concevoir ce qu'on appelle l'identification : clarifier qui l'on est, donner des contours précis à l'idem, au nous communautaire, et donc, nécessairement, définir ce que l'on n'est pas et n'entend pas devenir.

Le facteur discriminant à la base de tout raisonnement, et considéré par Douguine comme le fondement d'une nouvelle réappropriation des termes politiques universels, est l'idée de tradition. La tradition, qui est l'identité dans tout son déploiement de forme, de destin et d'histoire, centralise la possibilité d'une emprise culturelle qui désamorce et dépasse les dérives menaçantes de la modernité. La tâche consiste à contrôler cette modernité, à la circonscrire. A la limite, de manière évolutive, de la chevaucher pour la maîtriser et finalement l'apprivoiser. Nous savons que, ce n'est pas un hasard, Evola a été l'un des phares principaux dans la formation de Dugin, ce qui explique aussi le développement même de sa pensée. L'arrivée actuelle à la Quatrième théorie politique, que Douguine envisage comme l'aboutissement d'une prise de possession progressive des motifs idéologiques, a en soi une tendance évolienne, ne serait-ce qu'en référence à la possibilité, que Douguine souligne, de concevoir l'influence sur la réalité en termes d'action. Réalisme, c'est le mot. La "Voie de la main gauche", dirait l'essai, s'impose comme le trait saillant d'un interventionnisme qui ne doit jamais s'abandonner à la phase contemplative, donnant à l'action, à l'incision de la volonté dans la réalité, le sens d'un devoir existentiel.

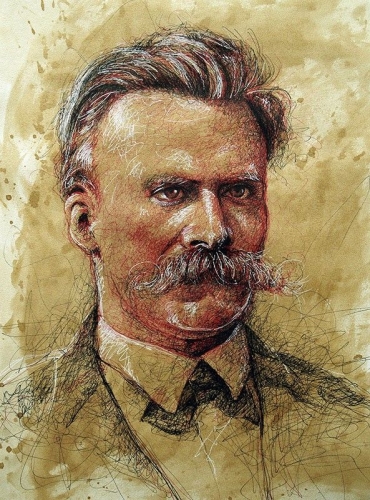

Il y a en fait beaucoup d'éléments ontologiques, "existentialistes" et même heideggériens chez Douguine. Par exemple, son acceptation du Dasein comme être-au-monde en qualité de sujets et non d'objets, dans le déploiement d'une volonté de réalisme froid, accroché au logos plutôt qu'au mythos, visant la constitution d'un type humain apte à la lecture de la réalité. Et il y a ceux qui ont parlé, à propos de cette ontologie présente dans la Quatrième théorie politique de Dugini, d'une véritable "anthropologie existentielle". Il faut un homme nouveau, d'un autre calibre que le bourgeois universel, pour pousser la réalité à son maximum de contradiction. Une nouvelle volonté est nécessaire pour plonger notre regard dans les profondeurs et accompagner la post-modernité jusqu'à sa désintégration finale. Favoriser l'avènement du Kali-Yuga, en somme, faire du nihilisme actif, comme Nietzsche l'indiquait déjà, battre les nihilistes du progressisme cosmopolite sur leur propre terrain, en précipitant leur catastrophe. Y a-t-il quelque chose de nouveau dans tout cela ? Ou s'agit-il de mots, d'idées, déjà entendus, de fresques d'époque déjà observées ? Bien sûr, tout a déjà été dit, assimilé, et tout est déjà en circulation depuis un certain temps. Mais je ne pense pas qu'il soit intéressant de faire une nouveauté de l'idéologie anti-monde, et donc de Douguine. Plutôt que la nouveauté, ce qui nous intéresse ici, c'est la vérité, c'est-à-dire le maintien du pérenne.

Mais ce qui est nouveau, en tout cas, et même très nouveau, c'est l'effort fait par Douguine pour maintenir certaines significations liées entre elles, pour éviter qu'elles ne tombent dans la poubelle de l'histoire enterrée par la haine biblique qui éclate toujours dès que certaines valeurs semblent résister. Le communautarisme identitaire traditionnel, greffé sur la préservation du contact avec la terre, le lien qui s'établit entre un grand espace existentiel et la coexistence impériale d'ethnies solidaires: voilà la formule qui va au-delà de la révolution et de la préservation, les fusionnant simplement en une seule formation politique d'opposition à la mondanité défigurée.

Douguine manipule des matériaux anciens, c'est vrai, il travaille avec des archaïsmes, mais il élabore aussi des solutions transgressives par rapport aux formules déjà expérimentées dans le passé. Au-delà du libéralisme (de droite et de gauche), au-delà du communisme et au-delà du fascisme (dans toutes ses déclinaisons internationales), Douguine apprend l'histoire, mais il sait l'utiliser comme une chose vivante dans son traçage du moment de rupture: la " métaphysique du Chaos ", la condition proposée comme terrain sur lequel jouer les possibilités de l'avenir, est remplie d'un esprit combatif et oppositionnel, elle est proposée comme un climax idéologique. La ruine de la post-modernité est acceptée pour ce qu'elle est, et c'est de là qu'il faut repartir pour détourner la marche progressiste et la convertir en son contraire. Il s'agirait d'une opération d'ingénierie politique et sociale pour esprits révolutionnaires, façonnée par le désir de préserver ce qui peut encore palpiter de vie : la solidarité du lignage, la communauté d'histoire, de sol et de destin. Quoi d'autre ? La volonté des semblables de convoquer les semblables.

Afin d'identifier, il est donc nécessaire de définir, de délimiter, voire de fixer des limites. L'Eurasie est l'espace identifié par Douguine comme essentiel pour une reconquête humaine de l'identité. C'est le destin d'une histoire et d'une famille de peuples et de cultures qui est en jeu. L'empire est le lieu de vie et de développement d'une "anthropologie pluraliste" qui, tout en rejetant l'universalisme catholique-progressiste-libéral, assure la protection d'ethnocultures complémentaires. Dugin, en exposant la philosophie politique de l'Eurasisme, pense au co-partenariat de diverses réalités - essentiellement, la russe et la touranienne - maîtres de leur espace géo-historique macro-continental capable, du point de vue de la grande politique mondiale, d'assurer le rôle antagoniste contre l'empire maritime atlantiste. Comme chacun peut le constater, il se reflète, dans ces cadrages géopolitiques douguiniens, ici à peine esquissés, le travail conceptuel de rivages idéologiques proches de ce qu'on a appelé la Révolution conservatrice, où, avec Schmitt et sa théorie de l'opposition Terre/Mer ou avec Moeller van den Bruck ou les nationaux-bolcheviks, avec leur vision de l'espace russe comme allié d'une Allemagne anti-atlantiste, l'alternative cardinale à la canalisation forcée de l'Europe dans la tenaille libérale de l'Occident démocratique était configurée. En fait, on peut très bien considérer Douguine comme un continuateur, un prolongement, de certaines positions révolutionnaires-conservatrices de l'époque précédant la Seconde Guerre mondiale.

La conjugaison des valeurs, en tout cas, devient une thérapie politique à adapter aux contingences: Douguine, l'ennemi de l'internationalisme et de l'universalisme abstrait, parle le langage concret de ceux qui sont philosophes, mais politiques, qui conçoivent aussi des doses d'eschatologie messianique et d'orthodoxie religieuse, mais bien liées au volontarisme concret d'un certain peuple, d'un groupe de peuples, précis et identifié. Douguine est un Russe, et il traite de la Russie. Il n'élabore pas de recettes universelles, ni ne présente de formules indifférenciées. Il sait où se tourner :

"Pour mon pays, la Russie, la Quatrième théorie politique a une énorme signification pratique. Le peuple russe a presque entièrement rejeté l'idéologie libérale des années 1990, mais il est également clair qu'un retour aux idéologies politiques illibérales du 20e siècle, telles que le communisme ou le fascisme, n'est pas une perspective probable, car ces idéologies ont déjà échoué et se sont révélées indignes du défi que représente l'opposition au libéralisme, sans parler du coût humain du totalitarisme".

L'effort d'identification de Douguine est donc très clair. Il porte la critique de la civilisation mondiale (qui est aujourd'hui le modèle occidental exporté et imposé, et volontairement accepté, et élevé au rang de fonction universelle incontestée) sur le terrain de l'échec du système américain généré par l'optimisme des Quakers et des Lumières. Douguine jette son regard dans le ravin qui sépare les bonnes intentions propagandistes du mondialisme de ses réalisations concrètes, fondées sur la violence et la prévarication et marquées par la vieille barbarie inégalée et pas du tout "libérale". C'est ainsi qu'il souligne "la différence frappante entre le comportement concret des États et des sociétés, fait de guerres, d'oppression, de cruauté et d'accès sauvages de terreur, qui entraînent des troubles psychologiques de plus en plus graves, et les prétentions rationalistes d'une existence harmonieuse, pacifique et éclairée sous la bannière du progrès et du développement".

Il est clair qu'aller au-delà du libéralisme, du communisme et du fascisme, et proposer une Quatrième Voie de libération des chaînes idéologiques du vingtième siècle, peut signifier réactualiser les héritages éternels de la communauté. C'est ce que Douguine revendique comme le point commun de l'histoire, du sol et du destin. Le dépassement du nationalisme est conçu comme un élargissement à la dimension de l'empire, une réalité qui lie les semblables. Il ne s'agit pas du tout d'une négation de la donnée ethnique, mais de son harmonisation au sein d'une famille politique d'expériences distinctes mais similaires. En bref, c'est l'empire, une structure supranationale qui ne nie pas la nation, mais l'incorpore précisément, mettant un frein, une limite, même psychologique, aux utopies tragiques de l'illimitation universelle.

Élève dans une certaine mesure de Lev Gumilëv, le patriarche de la géopolitique eurasiste, Douguine échappe néanmoins aux vieilles écoles en chargeant son cadre de contributions plus subversives face à l'ordre mondial: pensons à sa proximité, maintes fois réitérée, avec la galaxie du radicalisme européiste de Thiriart, de Benoist, Steuckers et Mutti. C'est sans doute pour cela que le dosage douguinien entre le nationalisme grand-russe et le pan-touranisme eurasiste constitue l'arme la plus efficace et la plus révolutionnaire au service d'un pluralisme planétaire anti-occidental.

Le protagonisme politique du Cœur de la Terre (le Heartland de l'ancienne géopolitique Mackinder), repensé de façon moderne, n'est rien d'autre que la nouvelle fonction de collaboration et d'intégration entre la Forêt, c'est-à-dire le monde slave, et la Steppe, c'est-à-dire le monde touranien eurasien, qui comprend également des fraternités ethniques solidement et complètement européennes, comme la Finlande et la Hongrie. Cette soudure constitue l'espace impérial auquel Douguine attribue des qualités antagonistes par rapport au projet de globalisme universel. En quête d'amis sur une planète où la lutte pour les ressources devient de plus en plus serrée, dans l'apparition de sujets géopolitiques mondiaux toujours nouveaux, le modèle eurasiste proposé par Douguine, pour tout ce qu'il contient de "gnostique" et d'idéaliste, n'est pas tant une option culturelle parmi d'autres, mais un destin inévitable, si nous ne voulons pas que la diversité succombe dans le chaudron égalitaire.

11:47 Publié dans Eurasisme, Nouvelle Droite | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : eurasisme, alexandre douguine, nouvelle droite, nouvelle droite russe, quatrième théorie politique |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

jeudi, 30 décembre 2021

NOOMAKHIA : Guerres de l’Esprit - Sur le magnum opus d'Alexandre Douguine

NOOMAKHIA : Guerres de l’Esprit

Sur le magnum opus d'Alexandre Douguine

(2019)

Noomakhia: Wars of the Mind est le magnum opus en cours de publication du « philosophe le plus dangereux dans le monde », Alexandre Douguine (né en 1962). Devant bientôt entrer dans son 28e et dernier volume en russe, Noomakhia est en train de devenir l’une des contributions les plus ambitieuses et les plus complexes du XXIe siècle pour de nombreux domaines et écoles de pensée. Au-delà d’une série d’études noologiques innovantes dans l’histoire des Civilisations, et au-delà de la culmination originale d’un grand nombre d’idées et de travaux antérieurs de l’auteur, Noomakhia vise à inaugurer un nouveau paradigme philosophique, basé sur la déconstruction radicale de l’universalisme de la Modernité occidentale et sur la reconstruction audacieuse d’un modèle pluriversel des variations des Logoi qui structurent les cultures humaines. Noomakhia tente d’initier une nouvelle anthropologie, d’établir un nouveau discours sur l’histoire et les structures de la Noomachie (du grec « Guerre de l’Esprit ») qui conditionnent la diversité des civilisations humaines, et à contribuer à un Dialogue des Civilisations intercontinental.

A mesure que Noomakhia commence à entrer graduellement dans le domaine anglophone, cette section de la bibliothèque en expansion de la Eurasianist Internet Archive présentant des traductions originales des penseurs du courant eurasiste est dédiée à rassembler les premiers aperçus dans l’épicentre de Noomakhia. Dans la section qui suit, les lecteurs, les chercheurs, et les traducteurs peuvent trouver une base de données régulièrement mise à jour de Noomakhia dont des extraits sont présentés et traduits pour la première fois en langue anglaise. Comme le projet Noomakhia dans son ensemble, cette ressource est un travail en progrès. Tous les volumes de Noomakhia sont actuellement publiés en russe par Academic Project (Moscou, Fédération Russe).

Les lecteurs et les chercheurs sont aussi invités à visiter la section « Additional Materials » ci-dessous, présentant une collection croissante d’interviews, d’articles, et de cours se rapportant à Noomakhia, incluant Introduction to Noomakhia Video Lecture Series [Série de cours vidéo – Introduction à la Noomachie] ainsi que les publications du site Geopolitica.ru.

---

« Le projet Noomakhia est basé sur une étude en profondeur des différentes cultures, systèmes philosophiques, arts, religions et traits psychologiques et caractéristiques des civilisations humaines. Noomakhia examine tous les peuples – anciens et modernes, hautement sophistiqués et « primitifs », ces qui sont technologiquement hautement développés et ceux qui n’ont pas de langage écrit. Le but ultime de Noomakhia est de démontrer et de prouver d’une manière concluante qu’aucune culture singulière ne peut être considérée d’une manière hiérarchique (développée/sous-développée, supérieure/inférieure, moderne/pré-moderne, civilisée/sauvage, etc.). L’évaluation responsable de toute culture humaine doit être faite de l’intérieur, par ceux qui lui appartiennent, et sans l’imposition de préjugés extérieurs (l’interprétation est culturellement toujours partiale). Noomakhia présente une argumentation en faveur de la dignité de l’humanité qui vit à l’intérieur de l’incommensurabilité de toutes ses formes culturelles existantes.

Le point de départ – et le trait principal de Noomakhia – est le concept des Trois Logoi, les trois paradigmes noologiques qui définissent la structure de toute culture. Les Trois Logoi sont :

- L’apollinien (patriarcal, hiérarchique, androcratique, vertical, exclusif, « céleste », transcendant) – le Logos lumineux ;

- Le dionysiaque (médian, androgyne, extatique, immanent sans matérialisme, équilibré, dialectique) – le Logos obscur ;

- Le cybélien (matriarcal, horizontal, gynocratique, inclusif, chthonien, immanent, matérialiste) – le Logos noir.

Noomakhia propose que ces trois Logoi sont présents dans chaque culture, mais qu’ils sont irréductibles (invariants) et conservent toujours leur essence distincte. D’où le concept de Noomakhia (ou « Noomachie »), la bataille constante entre les Trois Logoi qui constitue la dynamique de la création des moments de la dialectique culturelle et historique. Ce sont des variables dans le déroulement historique de toute culture et ils se développent en périodes et phases différentes. Il n’existe aucune règle universelle qui ait défini ou qui puisse définir la succession et la durée de ces phases et moments dans la Noomachie. Chaque culture et civilisation possède sa propre séquence unique dans le déroulement de la Noomakhia, avec ses propres particularités uniques caractérisant les victoires et les triomphes des divers Logoi qui transforment fondamentalement tous les rôles. Chaque culture doit être étudiée et évaluée individuellement et avec un soin considérable, évitant toute tentation de projeter la structure de sa propre expérience étudiée sur la Noomakhia des autres.

Le second principe du projet Noomakhia est de définir le domaine de recherche et les limites de la civilisation. Le concept de civilisation est culturel et basé sur la présomption d’une coexistence parmi les peuples de la terre de cercles (ou horizons) existentiels différents, qui sont identifiés comme la pluralité des Dasein. L’étape suivante est la clarification du concept spatial de culture des civilisations étudiées et la présentation des séquences sémantiques (l’historial, Seinsgeschichte) des événements les plus significatifs interprétés dans l’optique de ces peuples et cultures concrets. »

– Alexandre Douguine, “The Noomakhia Project” (2019)

Source:

https://eurasianist-archive.com/item/noomakhia/

13:07 Publié dans Nouvelle Droite, Philosophie | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : alexandre douguine, nouvelledroite, nouvelle droite russe, noomachie |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

samedi, 25 décembre 2021

Biden atlantiste contre Poutine eurasien

Biden atlantiste contre Poutine eurasien

Alexandre Douguine

Source: https://www.geopolitica.ru/article/atlantist-bayden-vs-evraziec-putin

L'escalade des relations entre la Russie et les États-Unis après l'arrivée de Joe Biden à la présidence et l'aggravation de la situation autour de l'Ukraine, ainsi que la tension croissante sur le périmètre des frontières russes (actions provocatrices des navires de l'OTAN dans le bassin de la mer Noire, manœuvres agressives des forces aériennes américaines le long des frontières aériennes russes, etc.) - tout cela a une explication géopolitique tout à fait rationnelle. La racine de tout doit être recherchée dans la situation qui a émergé à la fin des années 80 du vingtième siècle, lorsque l'effondrement des structures du camp soviétique a eu lieu. En même temps que le socialisme en tant que système politique et économique, une construction géopolitique solide et de grande ampleur, qui n'a pas été créée par les communistes, mais représentait une continuation historique naturelle de la géopolitique de l'Empire russe, s'est effondrée. Il ne s'agissait pas seulement de l'URSS, qui était un successeur direct de l'Empire et comprenait des territoires et des peuples rassemblés autour du noyau russe bien avant l'établissement du pouvoir soviétique. Les bolcheviks - sous Lénine et Trotsky - en ont perdu une grande partie au début, puis avec beaucoup de difficultés - sous Staline - l'ont regagnée (avec davantage encore de territoires). L'influence de la Russie en Europe de l'Est n'a pas non plus été uniquement le résultat de la Seconde Guerre mondiale, poursuivant à bien des égards la géopolitique de la Russie tsariste. L'effondrement du pacte oriental et l'effondrement de l'URSS n'étaient donc pas seulement un événement idéologique, mais une catastrophe géopolitique (comme le président Poutine lui-même l'a déclaré sans équivoque).

Dans la Russie des années 1990, sous le règne d'Eltsine et de la toute-puissance des libéraux pro-occidentaux, le processus de désintégration géopolitique s'est poursuivi, avec en ligne de mire les territoires du Caucase du Nord (première campagne de Tchétchénie) et, à plus long terme, d'autres parties de la Fédération de Russie. Pendant cette période, l'OTAN s'étendait librement et rapidement vers l'Est, incorporant presque entièrement l'espace de l'Europe de l'Est (les anciens pays du Pacte de Varsovie) ainsi que les trois républiques baltes de l'URSS - Lituanie, Lettonie et Estonie. Ce faisant, tous les accords avec Moscou ont été rompus. Washington a promis à Gorbatchev que même une Allemagne unie gagnerait en neutralité après le retrait des troupes soviétiques de la RDA et, de plus, aucune expansion de l'OTAN n'avait été envisagée. Zbigniew Brzezinski a déclaré avec franchise et cynisme en 2005 lorsque je lui ai demandé directement comment il se faisait que l'OTAN se soit étendue au mépris de ces promesses faites à Gorbatchev : "nous l'avons trompé". Gorbatchev a également été trompé par l'Occident en ce qui concerne les trois républiques baltes.

Le nouveau chef de la Russie, Boris Eltsine, s'est vu promettre une nouvelle fois qu'aucune des anciennes républiques soviétiques restantes ne serait admise dans l'OTAN. Immédiatement, l'Occident a commencé à créer, selon son habitude, divers blocs dans l'espace post-soviétique - d'abord le GUAM, puis le Partenariat oriental - avec un seul objectif : préparer ces pays à l'intégration dans l'Alliance de l'Atlantique Nord. "Nous avons triché, nous avons triché et nous continuerons à tricher", ont proclamé les atlantistes presque ouvertement, sans honte.

En Russie même, les cinquième et sixième colonnes au sein de l'État ont adouci le choc et contribué au succès de l'Occident à tous les coups. Poutine a récemment décrit comment il a éliminé les espions américains directs de la structure de gouvernance du pays, mais il est clair qu'il ne s'agit que de la partie émergée de l'iceberg - il ne fait aucun doute que la majeure partie du réseau atlantiste occupe toujours des postes influents au sein de l'élite russe.

Ainsi, dans les années 1990, l'Occident a tout fait pour transformer la Russie, sujet de la géopolitique qu'elle était à l'époque de l'URSS et de l'Empire russe (c'est-à-dire presque toujours - à l'exception de l'époque des conquêtes mongoles), en objet. C'était la "grande guerre continentale", l'encerclement du Heartland, la constriction de "l'anaconda" autour de la Russie.

Dès son arrivée au pouvoir, Poutine a entrepris de sauver ce qui pouvait encore l'être. C'était opter pour la voie de la souveraineté. Dans le cas de la Russie - compte tenu de son territoire, de son histoire, de son identité et de sa tradition - être souverain signifie être un pôle indépendant de l'Occident (car les autres pôles sont soit très inférieurs à l'Occident en termes de puissance, soit, contrairement à l'Occident, ne prétendent pas étendre agressivement leur modèle civilisationnel). L'orientation même de Poutine vers la souveraineté et le retour de la Russie dans l'histoire impliquait une augmentation de la confrontation. Et cela a eu un effet naturel sur la diabolisation croissante de Poutine et de la Russie elle-même en Occident. Comme l'a déclaré Darya Platonova dans une émission de Channel One, "la ligne rouge pour l'Occident est l'existence même d'une Russie souveraine". Et cette ligne a été franchie par Poutine presque immédiatement après son arrivée au pouvoir.

L'Occident et la Russie sont comme deux vases communicants : s'il y a du flux vers l'un, il y a du flux hors de l'autre, et vice versa. Jeu à somme nulle. Les lois de la géopolitique sont strictes, et nous en étions convaincus sous Gorbatchev et Eltsine - ils voulaient être les amis de l'Occident et partager ensemble le pouvoir sur le monde. L'Occident a pris cela comme un signe de faiblesse et de capitulation. Nous gagnons, vous perdez, signez ici. Cette formule du néoconservateur Richard Perle ("nous gagnons, vous perdez, signez ici") a été la base des relations avec la Russie post-soviétique. Mais c'était comme ça avant Poutine.

Poutine a dit "stop". Doucement et tranquillement au début. Puis il n'a pas été entendu. Puis, dans le discours de Munich, il y a été plus fort. Et encore une fois, ses propos n'ont suscité que de l'indignation, semblant être une "farce inappropriée".

Les choses sont devenues plus sérieuses en 2008, et après le Maïdan atlantiste, la réunification ultérieure avec la Crimée, et le retrait du Donbass hors de l'orbite de Kiev et le succès des forces russes en Syrie - la situation est devenue plus grave que jamais. La Russie est redevenue un pôle souverain, s'est comportée comme tel et a parlé à l'Occident en tant que tel. Trump, davantage préoccupé par la politique nationale américaine, n'y a pas prêté beaucoup d'attention car il a adopté une position réaliste sur les Relations internationales. Et cela signifie prendre au sérieux la souveraineté et une erreur de calcul purement rationnelle - comme dans les affaires - des intérêts nationaux en dehors de tout messianisme libéral. De plus, Trump n'était apparemment pas du tout conscient de l'existence de la géopolitique.

Mais l'arrivée de Biden a aggravé la situation à l'extrême. Derrière Biden aux États-Unis se profilent les faucons les plus radicaux, les néoconservateurs (qui détestent Trump pour son réalisme) et les élites mondialistes qui diffusent fanatiquement une idéologie ultra-libérale. L'impérialisme atlantiste se superpose au messianisme LGBT. Un mélange détonnant de pathologie géo-idéologique et de gendérisme. La Russie indépendante et souveraine (polaire) de Poutine est une menace directe pour ces deux éléments. Ce n'est pas une menace contre l'Amérique, mais contre l'atlantisme, le mondialisme et le libéralisme gendériste. Mais la Chine actuelle est également de plus en plus souveraine.

C'est dans cette situation que Poutine informe l'Occident de ses "lignes rouges". Et ce n'est pas quelque chose de frivole. Il y a derrière cela un contrôle concret des réalisations spécifiques de la Russie. Jusqu'à présent, il n'est pas question que l'Europe de l'Est soit écartée de l'Eurasie. Le statu quo des États baltes est reconnu. Mais l'espace post-soviétique est une zone de responsabilité exclusive de la Russie. Cela concerne principalement l'Ukraine, mais aussi la Géorgie et la Moldavie. D'autres pays n'expriment pas ouvertement leur désir d'adopter une position agressive contre Moscou et de fusionner avec l'Occident et l'OTAN.

Toute faux finit par trouver une pierre. Biden l'atlantiste contre Poutine l'eurasien. Il y a un choc entre deux points de vue totalement exclusifs l'un de l'autre - noir et blanc. "Le grand échiquier", comme l'a dit Brzezinski. L'amitié ne peut pas gagner dans une telle situation. Cela signifie deux choses : soit la guerre est inévitable, soit l'une des parties ne peut pas supporter la tension et abandonne ses positions sans se battre. Les enjeux sont extrêmement élevés : le sort de l'ordre mondial tout entier est en jeu.

L'Ukraine n'est qu'une figure mineure dans le Grand Jeu. Oui, c'est une pierre d'achoppement aujourd'hui. Pour la Russie, il s'agit d'une zone vitale en termes de géopolitique. Pour l'Occident, elle n'est qu'un des maillons de l'encerclement de la Russie-Eurasie par la "stratégie de l'anaconda" atlantiste. Laisser l'Ukraine adhérer à l'OTAN ou autoriser la présence de bases militaires américaines sur son sol est un coup fatal porté à la souveraineté de la Russie, qui annule la quasi-totalité des réalisations de Poutine. Insister sur les "lignes rouges", c'est se préparer à la guerre.

Dans une telle situation, le compromis est impossible. Certains perdent, d'autres gagnent. Avec ou sans guerre.

Il est évident que la sixième colonne (personne n'écoute la cinquième colonne au pouvoir aujourd'hui) perd tout en cas de confrontation directe avec l'Occident en Ukraine, ou simplement lorsque le conflit passe à la phase chaude. Un changement dans la politique russe est inévitable - et il est évident que les figures patriotiques vont passer au premier plan. C'est pourquoi aujourd'hui, non seulement les libéraux du système (presque officiellement enregistrés comme agents étrangers), mais aussi de nombreuses autres personnes, qui ne peuvent formellement pas être soupçonnées d'être occidentalisées, persuadent Poutine, au sein de l'élite russe, de se retirer. Toutes sortes d'arguments sont en jeu : le sort de Nord Stream 2, la déconnexion de SWIFT, le retard technologique imminent, l'isolement, etc. Les mêmes arguments ont été utilisés en 2008, et après Maidan, et en Syrie. Poutine en est probablement bien conscient, et il reconnaîtra immédiatement le pouvoir qui se cache derrière ces marcheurs d'élite de Bruxelles et de Washington. Donc ils feraient mieux de ne pas essayer.

La seule façon de gagner une guerre - de préférence sans combat - est de s'y préparer pleinement et de ne céder aucune des positions vitales.

L'espace post-soviétique ne devrait être sous le contrôle stratégique que de la Russie. Aujourd'hui, non seulement nous le voulons, mais nous pouvons le faire. Et qui plus est : nous ne pouvons pas faire autrement. Mais le statut des États baltes (déjà membres de l'OTAN) et nos projets pour l'Europe de l'Est peuvent être discutés. Cela va au-delà des "lignes rouges" - un compromis est également possible ici.

Notre bref aperçu géopolitique le montre : Poutine a changé la signification géopolitique même de la Russie, la transformant d'un objet (ce qu'était la Russie dans les années 1990) en un sujet. Le sujet, en revanche, se comporte très différemment de l'objet. Elle insiste sur les siens, découvre et désigne les tromperies, entraîne une réponse, marque sa zone de responsabilité, résiste et pose des exigences, des ultimatums. Et le plus important : le sujet a suffisamment de pouvoir, d'envergure et de volonté pour mettre tout cela en pratique.

La crise des relations avec l'Occident, que nous connaissons aujourd'hui, est un signe sans équivoque de l'énorme succès de la géopolitique de Vladimir Poutine, qui, d'une main de fer, conduit la Russie vers le renouveau et le retour à l'histoire. Et dans l'histoire, nous avons toujours été capables de défendre nos "lignes rouges". Et sont souvent allés bien au-delà. En tant que vainqueurs, nos troupes ont visité de nombreuses capitales européennes, notamment Paris et Berlin. Bruxelles, Londres et... qui sait - peut-être même Washington un jour. À des fins purement pacifiques.

13:19 Publié dans Actualité, Affaires européennes, Géopolitique | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : états-unis, russie, politique internationale, géopolitique, alexandre douguine, europe, affaires européennes |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

mercredi, 01 décembre 2021

Prince Nikolaï Trubetskoy : l'impératif eurasien

Prince Nikolaï Troubetskoï : l'impératif eurasien

Alexandre Douguine

Source: https://www.geopolitica.ru/article/knyaz-nikolay-trubeckoy-evraziyskiy-imperativ

Troubetskoï-homme politique et Troubetskoï-scientifique