Whatever its contemporary associations, the natural home of political ecology lies on the Right – not the false Right associated with the Republican Party in America, of course, whose conservatism is little more than a desperate and self-destructive attachment to the liberal principles of the Enlightenment, but what Julius Evola has called the True Right: The timeless devotion to order, hierarchy, and justice, entailing implacable hostility against the anarchic and disintegrating principles of the modern age.

However, while a commitment to ecological integrity has long been a mainstay of the European Right, in the United States it is typically regarded as a plank in the progressive political platform – part of its prepackaged offering of open borders, economic redistribution, and amoral individualism. The absence of any broad Right-wing consensus on environmental questions in this country is partially due to the fact that our mainstream conservative party, a tense coalition of Protestant fundamentalists and neoliberal oligarchs, has proven unable (or unwilling) to actually conserve most vestiges of traditional society. This includes the purity, wholeness, and integrity of our native land, which constitute a significant part of the American national heritage. Articulating a Rightist approach to ecology while exposing its subversion by the political Left therefore remains a necessary task, due to its invariably progressive connotations in this country.

My argument for the essential place of ecology in any program of American Restoration, as well as my ideas concerning the form it should take, will differ markedly from other well-known “conservative” approaches. It is not premised merely upon our duty to wisely conserve natural resources for future human use, nor upon the restorative power of natural beauty and recreation, nor is it a patriotic commitment to preserve the heritage of our native land. These have their place, but are subordinate to the ultimate principle of ecology rightly understood: that the natural world and its laws are a primordial expression of the cosmic order and accordingly deserve our respect. Recapturing the metaphysical and ethical outlook of the traditional world, and restoring a society in accordance with it, therefore demands a defense of the natural order from those who would seek to subvert it.

To begin, it is necessary to distinguish between the Right- and Left-wing variants of political ecology, which differ so greatly in their metaphysical foundations and political ramifications as to constitute two wholly separate approaches to ecological preservation.

Leftist or progressive ecology is essentially an outgrowth of Enlightenment ideals of liberty and egalitarianism, extended to the natural world. Progressive ecology comes in two guises. The most well-publicized is the elite, technocratic, internationalist version associated with the European Greens, the American Democratic Party, and myriad NGOs, international agencies, and celebrity advocates across the globe. When it is sincere (and not merely a power grab or a cross upon which to nail ecocidal white patriarchs), this variant of progressive ecology pins its hopes on clean energy, international accords, sustainable development, and humanitarian aid as the necessary means by which to usher in an ecologically sound society. Its symbolic issue is global warming, fault for which is assigned almost exclusively to the developed world and which can be defeated through regulations penalizing these nations for their historic sins.

The other version is more avowedly radical in its political prescriptions, and might best be understood as the ecological arm of the New Left. It finds its army among the adherents of the post-1980s Earth First! and the Earth and Animal Liberation fronts, as well as green anarchists, anarcho-primitivists, and ecofeminists; its tactics are mass demonstrations, civil disobedience, and minor acts of sabotage that are sometimes branded “eco-terrorism.” Activists subscribing to these views tend to reject civilization altogether, and work to combat its many evils – hierarchy, racism, patriarchy, speciesism, homophobia, transphobia, classism, statism, fascism, white privilege, industrial capitalism, and so on – in order to end the exploitation and oppression of all life on Earth. “Total liberation” is their rallying cry. Though drawing upon romantic primitivism and New England Transcendentalism, the philosophical foundations of Leftist ecology can be traced more directly to the ‘60s counter-culture, critical race theory, feminism, and the peace and civil rights movements.

Despite their ostensible commitment to natural preservation, both variants of Leftist ecology (for reasons discussed below) ultimately devolve into a fixation on “environmental justice” and facile humanitarianism, lacking the features of a genuinely holistic, integral ecological worldview. However, despite the apparently monolithic nature of American environmentalism, the progressive understanding of ecology is not the only one to take root in this country.

To many of its earliest prophets, such as the Romantic poets and New England Transcendentalists, as well as nineteenth-century nature philosophers and wilderness advocates, nature mysticism was the contemporary expression of a primordial doctrine, one that emphasizes natural order and a devotion to forces that transcend mankind. For men of the West, this ancient doctrine and its understanding of the cosmos are expressed, symbolically and theoretically, in the traditional Indo-European religions and their philosophical offshoots.

According to some proponents of this tradition, while primordial man – with his unfettered access to divine reality – might have possessed this wisdom in its entirely, when mankind fell from his early state, these ancient teachings receded into distant memory. They are dimly echoed in the traditional religious doctrines of the ancient world, such as the old European paganisms, Vedic Hinduism, and early Buddhism. Philosophical traces of this old wisdom can also be discerned in the metaphysics of the Pythagoreans, Neoplatonists, and Stoics.

While certain strains of Christianity have emphasized a strictly dualistic and anti-natural conception of the cosmos, this is not the only or even the predominant view. The more esoteric Christian theologians and mystics (largely Europeans influenced by their ancestral pantheism or Neoplatonism) have also regarded the natural world as an unfolding of divine reality, expressed in the theology of Franciscan and Rhineland mysticism, as well as the Christian Hermetism of the Renaissance.

Finally, to counter the development of Enlightenment liberalism, socialism, scientific materialism, and industrialism in the modern era, Romanticism and German Idealism offered a new artistic and philosophical iteration of the ancient holistic worldview, which later achieved its most radical expression in the anti-anthropocentrism of Nietzsche, Heidegger, and Robinson Jeffers.

Of course it would be an exaggeration to claim that all of these thinkers were proto-ecologists or, for that matter, even remotely concerned with the preservation of wild nature. The point is rather to understand how they all offer, in languages and concepts adapted to different cultures and epochs, a particular way of approaching one primordial truth: that the cosmos is an interconnected, organic whole, a natural order which demands our submission.

The fundamental metaphysical orientation of the traditional world, and therefore of the True Right, might be technically described as “panentheistic emanationism.” Simply put, there is an ultimate reality, a silent ground that contains and transcends all that is, known variously as God, Brahman, the Absolute, the Tao, the One, or Being. All that exists is an unfolding or emanation of this primordial oneness, from the highest deities and angels to material elements in the bowels of the Earth. While there is a hierarchy of being, all that exists has dignity insofar as it participates in this divine unfolding. Everything in the cosmos is an emanation of this transcendent reality, including all things on Earth and in heaven: the animals, the plants, the mountains, the rivers and seas, and weather patterns, as well as the biological, chemical, and ecosystemic processes that give them order and being.

This includes the race of man, which occupies a unique station in the cosmic hierarchy. Into the primordial oneness, the seamless garment that linked all other known creatures in their unbroken fealty to the natural law, human self-consciousness arose. Though partaking of the material form of other animals and “lower” orders of creation, mankind also possesses reason and self-will, introducing multiplicity into the divine unity. We find ourselves between Earth and Heaven, as it were.

On the one hand, this renders us capable of transcending the limitations of the material world and obtaining insight into higher levels of being, thereby functioning as an aspect of “nature reflecting on itself.” By the same token, unique among other known emanations of the Godhead, we are capable of acting out of self-will, violating natural law and setting ourselves and our own intelligence up as rivals to the Absolute. In addition, given our self-will, artificial desires, and unnaturally efficient means of obtaining them, humans cannot in good conscience pursue the purely natural ends of propagation, hedonism, and survival at any costs. To truly achieve his nature, to reintegrate himself into that primordial oneness from which he is presently alienated, man must transcend the merely human and align his will with that of the Absolute. Certain humans are capable of approaching this state: These are the natural aristocrats, the arhats, the saints, the Übermenschen.

Of course, given our flawed and fallen nature, most humans will remain attached to their self-will and material interests. Thus, while the religion of egalitarianism proposes a basic anthropocentrism whereby all humans are equal simply by virtue of being human, in the traditional doctrine this is negated by the fact of human inequality. As Savitri Devi observed, a beautiful lion is of greater worth than a degenerate human, given the lion’s greater conformity to the natural order and divine Eidos. For this reason, both traditional metaphysics and an ecology viewed from the Right require that we reject the sentimental humanitarianism of the modern Left, according to which each and every human life (or, indeed, non-human life, in the case of animal rights) has equal value.

An additional implication of this view is that, humans being unequal in their ability to approach the divine and to exercise power justly, social arrangements must ensure rule by the higher type. This is the essence of the tripartite Indo-European social structure; the caste system of priest, warrior, and merchant/artisan that formed the basis of traditional societies. The regression of castes characteristic of the modern world, the collapse of all traditional social structures and the enshrinement of democratic rule, does not truly mean we are self-ruled. It merely means that instead of being ruled by priestly (spiritual) or kingly (noble) values, we are ruled at best by bourgeois (economic) or at worst by plebeian (anarchic) values. The values of the bourgeois and the plebeian are invariably oriented towards comfort, pleasure, and acquisition, rather than transcendence or honor. The tripartite organization is therefore necessary in order to place a check on humanity’s most profane and destructive impulses, towards itself and towards the natural world.

The corollary to this outlook is a suspicion of the philosophical underpinnings of late modernity, with its unbridled reductionism, atomism, and purely instrumental view of man. Other sociopolitical implications follow.

Rightist ecology entails a rejection of both Marxist-Communist and neoliberal economics, the former for its egalitarian leveling and both for their reduction of man to a purely economic being. In addition to its toxicity for the human spirit, this tyranny of economics leads humans to regard the world not as the garment of God but as a mere standing reserve, a collection of resources for the satisfaction of human desires.

While advocating for technology that genuinely improves human life and lessens human impact on other species, the Right-wing ecologist rejects technology which encourages ugliness, hedonism, weakness, and feckless destruction.

While understanding the importance of cities as centers of culture and commerce, the Right-wing ecologist prefers the Italian hill town, attuned to the contours of the land, with a cathedral standing at its highest point, over the inhuman modernist metropolis or manufactured suburb.

This ecology also entails an opposition to excessive human population growth, which threatens spiritual solitude, the beauty of the wilderness, and the space needed for speciation to continue. Quality and quantity are mutually exclusive.

Additionally, contrary to the “totalitarian” slur often employed against it, the True Right believes that difference and variety is a gift from God. Rather than viewing this as a categorical imperative to bring as much diversity as possible into one place, the right seeks to preserve cultural, ethnic, and racial distinctions. It should therefore also strive to preserve the world’s distinct ecosystems and species, as well as human diversity of race and culture, against feckless destruction by human actors (unavoidable natural catastrophes are another matter). As the world of mankind sinks into greater corruption, the natural world remains as a reflection of eternal, higher values, a unified whole unfolding in accordance with the divine order.

A possible objection bears discussion. All Indo-European beliefs, and indeed most traditional doctrines the world over, posit an inevitable end to this world. Whether it comes to a close with the Age of Iron, the Second Coming, the Age of the Wolf, or the Kali Yuga, most teach that this cosmic cycle must end in order to make way for a new one. This generally entails the destruction of the Earth and everything on it. How can this be reconciled with a Right-wing ecology, which posits a duty to preserve those vestiges of pure nature most reflective of the divine order? What, indeed, is the point, if it is all destined to be destroyed anyway?

First of all, this apocalyptic scenario is also a dogma of modern science, inescapably implied by its theories of cosmic evolution. Life on Earth will be destroyed, if not by some anthropogenic insanity then by the expansion of the Sun or the heat death of the universe. The difference is that the progressive ecologist has no abiding, objective reason to preserve the pristine and the authentic in nature beyond personal taste; no escape, in fact, from the jaws of complete subjectivity and nihilism. This is why progressive ecology typically devolves into a concern with social justice, when it is not merely a personal preference for pretty scenery or outdoor recreational opportunities.

For the ecologist of the Right, however, the end of all things human is no argument against living with honor and fighting dispassionately against the forces of disintegration and chaos. The Man Against Time may, in the long run, be destined to fail in his earthly endeavors, but that does not lessen his resolve. This is because he acts out of a sense of noble detachment – the karma yoga of the Bhagavad Gita, Lao-tzu’s wu-wei, or Meister Eckhart’s Abgeschiedenheit – whereby action flows from the purity of his being and his role in the cosmos rather than from utilitarian calculus or willful striving. Upholding the natural order demands that we defend its purest expressions: the holy, innocent, and noble among mankind, as well as the trees and wolves and rocks that were here before us, which abide in an unconscious harmony with the cosmic order to which man can only aspire.

In his commitment to live in conformity with the natural order and to uphold it against the arrogance of modern man, the Right-wing ecologist accepts the role of detached violence. Most environmentalist rhetoric one hears nowadays is couched in the effete verbiage of contemporary Leftism: rights, equality, anti-oppression, “ethics of care,” and so forth. In addition to its stronger metaphysical bent, the ecology of the Right also offers a more virile ecology, a creed of iron which disdains the technologization and overpopulation of the world because it leads to the diminishment of all life; which upholds the iron laws of nature, of blood and sacrifice, of order and hierarchy; and which is contemptuous of human hubris because of its very pettiness. It is an ecology that loves the wolf, the bear, the warrior, as well as the thunderstorm and the forest fire, for the role they play in maintaining the natural order; that wants to keep large tracts of the Earth wild and free, that cannot bear to see it rationalized, mechanized, and domesticated. It is ecology that disdains softness, ease, sentimentalism, and weakness.

The ecologist of the Right knows that “life in accordance with nature” is no Rousseauian idyll or neo-hipster imperative to “let it all hang out,” but demands stoicism, hardness, and conformity to a thousand stern laws in the pursuit of strength and beauty. This is a virile religiosity, an ascesis of action rather than mere personal salvation or extinction.

Seen in this light, ecology is a necessary feature in the restoration of traditional society. By “traditional” we mean not the free-market, family values, flag-waving fundamentalist zealotry that the term implies in twenty-first century America, but rather an outlook that is grounded upon the divine and natural order, which dictates that all things abide in their proper place. With respect to man and nature, this means that mankind must acknowledge his place in the cosmic order and his role as the guardian and self-awareness of the whole, rather than seeing himself as its tyrannical overlord. It demands the wisdom and introspection necessary to understand our role in the divine plan and to perform our duties well. It demands authenticity, recognizing the cultural and historical soil from which we emerged, and preserving the traditions and memory of our forefathers. This reverence towards the cosmic order demands that we respect its manifestation in the rocks, trees, and sky, whose beauty and power continually serve to remind us of the transcendent wisdom of the whole.

An earlier draft of this essay was published in Social Matter Magazine.

Pourquoi vous intéresser aux idéologies ? Ces dernières ont-elles un vrai impact sur notre société ?

Pourquoi vous intéresser aux idéologies ? Ces dernières ont-elles un vrai impact sur notre société ? Son progressisme se réclame d’une sorte de sens de l’Histoire allant vers plus de libéralisme économique et politique, de technologies douces, de multilatéralisme, de gouvernance, de performance et d’Europe. Mais, il entend aussi réaliser des « valeurs » sociétales, libertaires : ouverture, innovation, réalisation de soi, diversité, tolérance... Il est bien l’héritier des idées lib-lib qui se sont répandues peu avant ou après la chute de l’URSS et il pourrait être le symptôme d’une fin de cycle intellectuel. Pour le moment, de telles représentations convient plutôt à ceux, disons d’en haut. Elles leur garantissent à la fois la défense de leurs intérêts matériels et la satisfaction ostentatoire de se sentir supérieurs. Moralement face aux obsédés de l’identité et autres autoritaires ou intellectuellement face à ceux qui n’ont « pas compris que le monde a changé » .

Son progressisme se réclame d’une sorte de sens de l’Histoire allant vers plus de libéralisme économique et politique, de technologies douces, de multilatéralisme, de gouvernance, de performance et d’Europe. Mais, il entend aussi réaliser des « valeurs » sociétales, libertaires : ouverture, innovation, réalisation de soi, diversité, tolérance... Il est bien l’héritier des idées lib-lib qui se sont répandues peu avant ou après la chute de l’URSS et il pourrait être le symptôme d’une fin de cycle intellectuel. Pour le moment, de telles représentations convient plutôt à ceux, disons d’en haut. Elles leur garantissent à la fois la défense de leurs intérêts matériels et la satisfaction ostentatoire de se sentir supérieurs. Moralement face aux obsédés de l’identité et autres autoritaires ou intellectuellement face à ceux qui n’ont « pas compris que le monde a changé » . Vous relevez que les idéologies actuelles sont « anti » : antilibéralisme, anti-mondialisme, etc. Notre époque éprouve-t-elle des difficultés à créer de vraies idéologies, comme ont pu l’être le marxisme, le positivisme, le libéralisme ou le structuralisme ?

Vous relevez que les idéologies actuelles sont « anti » : antilibéralisme, anti-mondialisme, etc. Notre époque éprouve-t-elle des difficultés à créer de vraies idéologies, comme ont pu l’être le marxisme, le positivisme, le libéralisme ou le structuralisme ?

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

Me relisant, je me dis que j'ai finalement du mérite à m'être en fin de compte plongé dans la lecture de l'ouvrage de François Bousquet dont on ne pourra guère m'accuser, du coup, de vanter louchement les mérites qui, sans être absolument admirables ni même originaux, n'en sont pas moins bien réels : mes préventions, toujours, tombent devant ma curiosité, ma faim ogresque de lectures, et ce n'est que fort normal.

Me relisant, je me dis que j'ai finalement du mérite à m'être en fin de compte plongé dans la lecture de l'ouvrage de François Bousquet dont on ne pourra guère m'accuser, du coup, de vanter louchement les mérites qui, sans être absolument admirables ni même originaux, n'en sont pas moins bien réels : mes préventions, toujours, tombent devant ma curiosité, ma faim ogresque de lectures, et ce n'est que fort normal.

Reste une autre solution, plus fictionnelle, donc métapolitique, que réellement, modestement politique, sur le papier en tout cas ne souffrant point l'endogamie propre à l'élite française, de droite comme de gauche, solution purement romanesque qu'explore Bruno de Cessole dans son dernier livre, L'Île du dernier homme, et que nous pourrions du reste je crois sans trop de mal rapprocher de la vision de l'Islam développée depuis quelques années par Marc-Édouard Nabe, consistant à trouver, dans la vitalité incontestable des nouveaux Barbares, le sang nécessaire pour irriguer la vieille pompe à bout de force d'un Occident en déclin, d'une France complètement vidée de sa substance, d'un arbre, si cher au

Reste une autre solution, plus fictionnelle, donc métapolitique, que réellement, modestement politique, sur le papier en tout cas ne souffrant point l'endogamie propre à l'élite française, de droite comme de gauche, solution purement romanesque qu'explore Bruno de Cessole dans son dernier livre, L'Île du dernier homme, et que nous pourrions du reste je crois sans trop de mal rapprocher de la vision de l'Islam développée depuis quelques années par Marc-Édouard Nabe, consistant à trouver, dans la vitalité incontestable des nouveaux Barbares, le sang nécessaire pour irriguer la vieille pompe à bout de force d'un Occident en déclin, d'une France complètement vidée de sa substance, d'un arbre, si cher au

Dr Giles Fraser is a journalist, broadcaster and Rector at the south London church of St Mary’s, Newington

Dr Giles Fraser is a journalist, broadcaster and Rector at the south London church of St Mary’s, Newington Top spot must go to

Top spot must go to  Second spot is shared by two very contrasting approaches, one from the Right and one from the Left.

Second spot is shared by two very contrasting approaches, one from the Right and one from the Left.  The Road to Somewhere by David Goodhart

The Road to Somewhere by David Goodhart The defence of these ‘somewheres’, often derided as small-town, small-minded ‘deplorables’ is vividly captured by

The defence of these ‘somewheres’, often derided as small-town, small-minded ‘deplorables’ is vividly captured by

But despite the fact that many people exist within the quadrant it describes (Left on economics, Right on culture) it is still struggling to break through. It’s perhaps because it’s easier for the Right to break Left on economics than for the Left to break Right on culture — which is why the Conservative and Republican parties may be more amenable to this sort of thinking than their opponents. But even this is not a natural fit. Which brings us back to Gramsci. The old is dead. The new is yet to be born.

But despite the fact that many people exist within the quadrant it describes (Left on economics, Right on culture) it is still struggling to break through. It’s perhaps because it’s easier for the Right to break Left on economics than for the Left to break Right on culture — which is why the Conservative and Republican parties may be more amenable to this sort of thinking than their opponents. But even this is not a natural fit. Which brings us back to Gramsci. The old is dead. The new is yet to be born.

... Cette revue de détail nécessairement partielle et non limitative ne signifie en aucune façon qu’il existe, ou que va se créer un front vraiment “marxiste” contre le gauchisme-sociétal qu’on a tendance à assimiler au “marxisme culturel” pour le marier encore plus aisément à l’hypercapitalisme. (Leur “marxisme culturel” est un “marxisme de spectacle”, comme il y a la “société de spectacle” de Debord.) Seule importe cette position d'opposition très diverse à la passion fusionnelle capitalisme-gauchisme-sociétal, comme un socle continuel de critique, de mise en évidence et de dénonciation du simulacre capitalisme-gauchisme-sociétal.

... Cette revue de détail nécessairement partielle et non limitative ne signifie en aucune façon qu’il existe, ou que va se créer un front vraiment “marxiste” contre le gauchisme-sociétal qu’on a tendance à assimiler au “marxisme culturel” pour le marier encore plus aisément à l’hypercapitalisme. (Leur “marxisme culturel” est un “marxisme de spectacle”, comme il y a la “société de spectacle” de Debord.) Seule importe cette position d'opposition très diverse à la passion fusionnelle capitalisme-gauchisme-sociétal, comme un socle continuel de critique, de mise en évidence et de dénonciation du simulacre capitalisme-gauchisme-sociétal.

Robert Strausz fût en quelque sorte le père du néo-conservatisme, il théorisait l’idée d’une Europe décadente qui devait être sauvée des griffes de l’Asie russe, chinoise et arabe. Pour ce faire, l’Europe devait être gérée comme une province d’un empire américain comparable au rôle que tenait l’Empire romain pour les cités grecques face à l’empire perse asiatique. Il théorisait aussi l’idée d’un empire universel américain, éclaireur armé de la démocratie mondiale. Une idée qui sera reprise par les néo-conservateurs du Project for the New American Century (Projet pour le Nouveau Siècle Américain, PNAC) à la fin des années 1990.

Robert Strausz fût en quelque sorte le père du néo-conservatisme, il théorisait l’idée d’une Europe décadente qui devait être sauvée des griffes de l’Asie russe, chinoise et arabe. Pour ce faire, l’Europe devait être gérée comme une province d’un empire américain comparable au rôle que tenait l’Empire romain pour les cités grecques face à l’empire perse asiatique. Il théorisait aussi l’idée d’un empire universel américain, éclaireur armé de la démocratie mondiale. Une idée qui sera reprise par les néo-conservateurs du Project for the New American Century (Projet pour le Nouveau Siècle Américain, PNAC) à la fin des années 1990.

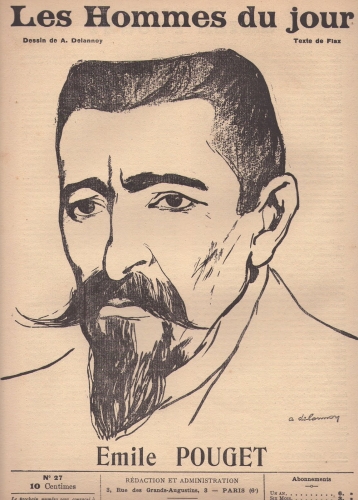

Pouget, un des pères de l'anarcho-syndicalisme la définissait ainsi :

Pouget, un des pères de l'anarcho-syndicalisme la définissait ainsi : C'est pourquoi nous laisserons la conclusion à un extrait des Justes de Camus :

C'est pourquoi nous laisserons la conclusion à un extrait des Justes de Camus :

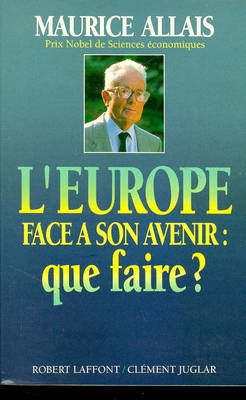

L’Europe reste toutefois l’engagement de sa vie. Il conçoit un ensemble européen, ordonné par le principe de subsidiarité, nommé la « Communauté politique européenne » (CPE). Cette CPE doit fonder à terme la « Nation européenne ». Ainsi écrit-il dans Combats pour l’Europe 1992 – 1994 (Clément Juglar, 1994) que « les Européens d’aujourd’hui veulent vivre ensemble. C’est là une réalité fondamentale qui se superpose aux liens très puissants qui se sont tissés au cours des siècles à l’intérieur de chaque Communauté nationale. […] Autant toute tentative tendant à dissoudre aujourd’hui les Nations européennes dans je ne sais quel ensemble de nature totalitaire est fondamentalement inacceptable, autant l’émergence progressive, dans les décennies qui s’approchent, d’une Nation européenne au sens d’Ernest Renan rassemblant dans une organisation décentralisée les Nations européennes et préservant leur identité ne saurait être obstinément refusée. En fait, il n’est pas du tout impossible qu’à la fin du XXIe siècle apparaisse une Nation européenne, démocratique et décentralisée, d’autant plus forte qu’elle aurait réussi à maintenir les différentes Nations qui la constituent dans leur propre identité et leur propre culture. Mais ce ne peut être là qu’un objectif éloigné. Il ne suffit pas de vouloir vivre ensemble. Il faut encore s’en donner les moyens (p. 89) ».

L’Europe reste toutefois l’engagement de sa vie. Il conçoit un ensemble européen, ordonné par le principe de subsidiarité, nommé la « Communauté politique européenne » (CPE). Cette CPE doit fonder à terme la « Nation européenne ». Ainsi écrit-il dans Combats pour l’Europe 1992 – 1994 (Clément Juglar, 1994) que « les Européens d’aujourd’hui veulent vivre ensemble. C’est là une réalité fondamentale qui se superpose aux liens très puissants qui se sont tissés au cours des siècles à l’intérieur de chaque Communauté nationale. […] Autant toute tentative tendant à dissoudre aujourd’hui les Nations européennes dans je ne sais quel ensemble de nature totalitaire est fondamentalement inacceptable, autant l’émergence progressive, dans les décennies qui s’approchent, d’une Nation européenne au sens d’Ernest Renan rassemblant dans une organisation décentralisée les Nations européennes et préservant leur identité ne saurait être obstinément refusée. En fait, il n’est pas du tout impossible qu’à la fin du XXIe siècle apparaisse une Nation européenne, démocratique et décentralisée, d’autant plus forte qu’elle aurait réussi à maintenir les différentes Nations qui la constituent dans leur propre identité et leur propre culture. Mais ce ne peut être là qu’un objectif éloigné. Il ne suffit pas de vouloir vivre ensemble. Il faut encore s’en donner les moyens (p. 89) ».

The book has given me a breakthrough in understanding why so many people who grew up under communism are unnerved by what’s going on in the West today, even if they can’t all articulate it beyond expressing intense but inchoate anxiety about political correctness. Reading

The book has given me a breakthrough in understanding why so many people who grew up under communism are unnerved by what’s going on in the West today, even if they can’t all articulate it beyond expressing intense but inchoate anxiety about political correctness. Reading

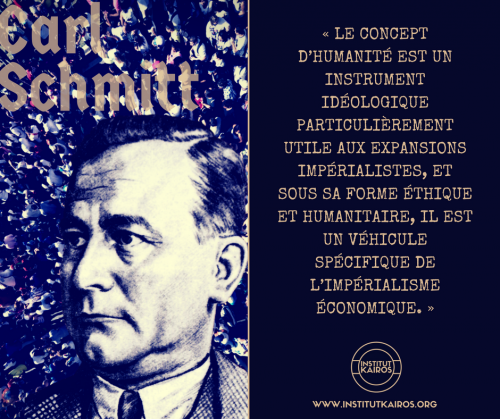

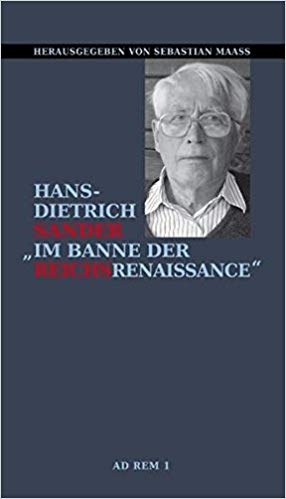

1969 promovierte Sander bei Hans-Joachim Schoeps in Erlangen zum Dr. phil. Der Titel seiner Promotionsschrift lautete „Marxistische Ideologie und allgemeine Kunsttheorie“; Sander setzte sich hier insbesondere mit der Kunstkonzeption von Marx und Engels auseinander. Es war wohl insbesondere der Einfluß des Staatsrechtlers Carl Schmitt, mit dem er bis 1981 brieflich in Kontakt stand, der ihn in dieser Zeit mehr und mehr zu rechtskonservativen Auffassungen tendieren ließ. Von 1964–1974 arbeitete er für das Deutschland-Archiv. In dieser Zeit gestaltete er gelegentlich auch Rundfunkfeuilletons für öffentlich-rechtliche Sender. Sanders „Geschichte der Schönen Literatur in der DDR“ (1972) löste eine heftige Kampagne aus, in deren Folge der Verlag das Buch aus dem Vertrieb zog. Sander verlor nun zunehmend an publizistischem Spielraum. Alternativen fand er unter anderem bei Caspar von Schrenck-Notzings Zeitschrift Criticón.

1969 promovierte Sander bei Hans-Joachim Schoeps in Erlangen zum Dr. phil. Der Titel seiner Promotionsschrift lautete „Marxistische Ideologie und allgemeine Kunsttheorie“; Sander setzte sich hier insbesondere mit der Kunstkonzeption von Marx und Engels auseinander. Es war wohl insbesondere der Einfluß des Staatsrechtlers Carl Schmitt, mit dem er bis 1981 brieflich in Kontakt stand, der ihn in dieser Zeit mehr und mehr zu rechtskonservativen Auffassungen tendieren ließ. Von 1964–1974 arbeitete er für das Deutschland-Archiv. In dieser Zeit gestaltete er gelegentlich auch Rundfunkfeuilletons für öffentlich-rechtliche Sender. Sanders „Geschichte der Schönen Literatur in der DDR“ (1972) löste eine heftige Kampagne aus, in deren Folge der Verlag das Buch aus dem Vertrieb zog. Sander verlor nun zunehmend an publizistischem Spielraum. Alternativen fand er unter anderem bei Caspar von Schrenck-Notzings Zeitschrift Criticón.  Sander hat nie einen Hehl daraus gemacht, daß er die Bundesrepublik für nicht reformierbar hielt. Beide deutsche Staaten seien unter Kuratel der Besatzer entstanden, was unter anderem für eine Negativauslese im Hinblick auf die Eliten gesorgt habe. Dennoch sei nichts verloren: Die Deutschen bräuchten „sich nur innerlich aufzuraffen“, so Sander im „Nationalen Imperativ“, „um sich der brüchigen alten Zustände der Innen- und Außenpolitik zu entledigen, wieder auf die überlieferten, immer noch wirkenden Tugenden zu setzen und neue Formen und Ziele zu wagen, die in Richtung auf einen neuen Machtstaat, eine neue Großmacht drängen, die den Nachbarn durchaus zuzumuten wäre, weil durch nichts sonst das schutzbedürftige Europa noch gerettet werden kann.“ Diese Sätze können, in einer Zeit, in der Europa durch die Auswirkungen der „Flüchtlingskrise“ schutzbedürftiger denn je ist, durchaus als Vermächtnis Sanders nicht nur an die Deutschen gelesen werden.

Sander hat nie einen Hehl daraus gemacht, daß er die Bundesrepublik für nicht reformierbar hielt. Beide deutsche Staaten seien unter Kuratel der Besatzer entstanden, was unter anderem für eine Negativauslese im Hinblick auf die Eliten gesorgt habe. Dennoch sei nichts verloren: Die Deutschen bräuchten „sich nur innerlich aufzuraffen“, so Sander im „Nationalen Imperativ“, „um sich der brüchigen alten Zustände der Innen- und Außenpolitik zu entledigen, wieder auf die überlieferten, immer noch wirkenden Tugenden zu setzen und neue Formen und Ziele zu wagen, die in Richtung auf einen neuen Machtstaat, eine neue Großmacht drängen, die den Nachbarn durchaus zuzumuten wäre, weil durch nichts sonst das schutzbedürftige Europa noch gerettet werden kann.“ Diese Sätze können, in einer Zeit, in der Europa durch die Auswirkungen der „Flüchtlingskrise“ schutzbedürftiger denn je ist, durchaus als Vermächtnis Sanders nicht nur an die Deutschen gelesen werden.

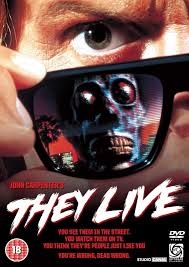

On parle beaucoup dans le monde antisystème de la chute de l’empire américain. Je m’en mêle peu parce que l’Amérique n’est pour moi pas un empire ; elle est plus que cela, elle est l’anti-civilisation, une matrice matérielle hallucinatoire, un virus mental et moral qui dévore et remplace mentalement l’humanité – musulmans, chinois et russes y compris. Elle est le cancer moral et terminal du monde moderne. Celui qui l’a le mieux montré est le cinéaste John Carpenter dans son chef-d’œuvre des années 80, They Live. Et j’ai déjà parlé de Don Siegel et de son humanité de légumes dans l’invasion des profanateurs, réalisé en 1955, année flamboyante de pamphlets antiaméricains comme La Nuit du Chasseur de Laughton, le Roi à New York de Chaplin, The Big Heat de Fritz Lang.

On parle beaucoup dans le monde antisystème de la chute de l’empire américain. Je m’en mêle peu parce que l’Amérique n’est pour moi pas un empire ; elle est plus que cela, elle est l’anti-civilisation, une matrice matérielle hallucinatoire, un virus mental et moral qui dévore et remplace mentalement l’humanité – musulmans, chinois et russes y compris. Elle est le cancer moral et terminal du monde moderne. Celui qui l’a le mieux montré est le cinéaste John Carpenter dans son chef-d’œuvre des années 80, They Live. Et j’ai déjà parlé de Don Siegel et de son humanité de légumes dans l’invasion des profanateurs, réalisé en 1955, année flamboyante de pamphlets antiaméricains comme La Nuit du Chasseur de Laughton, le Roi à New York de Chaplin, The Big Heat de Fritz Lang. Témoin donc de la désintégration de l’empire britannique causée par Churchill et Roosevelt, militaire vieille école, Glubb garde cependant une vision pragmatique et synthétique des raisons de nos décadences.

Témoin donc de la désintégration de l’empire britannique causée par Churchill et Roosevelt, militaire vieille école, Glubb garde cependant une vision pragmatique et synthétique des raisons de nos décadences.  Toutes ces causes se cumulent aujourd’hui en occident. Glubb écrit à l’époque des Rolling stones et on comprend qu’il ait été traumatisé, une kommandantur de programmation culturelle (l’institut Tavistock ?!) ayant projeté l’Angleterre dans une décadence morale, intellectuelle et matérielle à cette époque abjecte. C’est l’effarante conquête du cool dont parle le journaliste Thomas Frank. En quelques années, explique Frank notre nation (US) n’était plus la même. Idem pour la France du gaullisme, qui rompait avec le schéma guerrier, traditionnel et initiatique de la quatrième république et nous fit rentrer dans l’ère de la télé, de la consommation, des supermarchés, de salut les copains, sans oublier mai 68. Je ne suis gaulliste que géopolitiquement, pour le reste, merci… Revoyez Godard, Tati, Etaix, pour reprendre la mesure du problème gaulliste.

Toutes ces causes se cumulent aujourd’hui en occident. Glubb écrit à l’époque des Rolling stones et on comprend qu’il ait été traumatisé, une kommandantur de programmation culturelle (l’institut Tavistock ?!) ayant projeté l’Angleterre dans une décadence morale, intellectuelle et matérielle à cette époque abjecte. C’est l’effarante conquête du cool dont parle le journaliste Thomas Frank. En quelques années, explique Frank notre nation (US) n’était plus la même. Idem pour la France du gaullisme, qui rompait avec le schéma guerrier, traditionnel et initiatique de la quatrième république et nous fit rentrer dans l’ère de la télé, de la consommation, des supermarchés, de salut les copains, sans oublier mai 68. Je ne suis gaulliste que géopolitiquement, pour le reste, merci… Revoyez Godard, Tati, Etaix, pour reprendre la mesure du problème gaulliste. Détail chic pour raviver ma marotte du présent permanent, Glubb retrouve même trace des Beatles chez les califes !

Détail chic pour raviver ma marotte du présent permanent, Glubb retrouve même trace des Beatles chez les califes !