Yerevan is anxiously watching developments in neighbouring Turkey. Destabilization in a neighbouring country is in nobody’s interests, but events there are developing rapidly, and it is unlikely that there is anything good in store for Ankara, which has got involved in a whole range of conflicts in the region.

It seems that the truly strong and popular Turkish leader has overestimated his strength and, having unleashed a war on all fronts, both internal and external, now risks if not losing power, then facing very serious problems.

What has happened that the President of Turkey, formerly prime minister, and most importantly, continuous leader of the country for almost fifteen years, should suddenly find himself in such a difficult situation? The answer is both simple and complicated. R. T. Erdogan came to power at the beginning of the twenty-first century as an exponent for the professedly down-trodden Muslim masses of Turkish citizens, who are both relatively poor and followers of the religious ideals of Islam, to which his Justice and Development Party (AKP) gave a political “mould”.

By all accounts, the success of the last decade has gone to the Turkish politician’s head, and he decided to go after internal achievements as well as external. Beyond Turkey’s borders, he set himself the task of overthrowing the Bashar al-Assad’s secular regime in Syria, in the hope of bringing kindred Sunni “Muslim brothers” to power there and inside Turkey he set upon completely changing the political landscape of the country and, having achieved absolute majority in the parliamentary elections of 7 June 2015, changing the country’s constitution so that the Parliament’s basic powers were transferred to the president.

However, Erdogan clearly never studied the Coup of 18 Brumaire. The June elections not only didn’t allow him to become the sole ruler of the country, but he couldn’t even form a government, and now he has been forced to hold new elections, which are scheduled for November 1, where he plans to take revenge. But are his hopes justified?

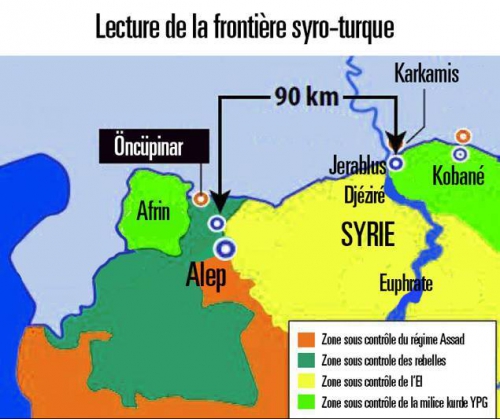

Firstly, outside the country, the support for all anti-governmental forces in Syria has led to the fact that Turkey has become almost an accessory to the ISIS terrorist movement, which until very recently received the supply of militants and weapons via the 900-kilometre Turkish-Syrian border. This led, in turn, to tensions between Erdogan and his NATO allies, primarily the United States, whom Turkey did not allow to bomb ISIS from its territory or use its Incirlik air base. Relations between the Turkish president and the Kurds have sharply deteriorated. The latter believed, they were receiving insufficient support from the Turkish authorities in the battle against ISIS for the town of Kobanî (Ayn al-Arab), where Washington itself had staunchly supported the Kurds.

The situation changed only after July 20 of this year, when an ISIS militant bombed Kurdish volunteers who had got together to help with the rebuilding of Kobanî, killing 32 of them. However, the attitude of the Turkish authorities to ISIS members had soured even earlier, when on July 17 an ISIS publication in Turkish entitled Konstantiniyye called for a fatwa against the “caliphate” and for a boycott of “unclean” Turkish meat.

The authorities couldn’t leave this with no response Immediately after the terrorist attack, and a telephone conversation between Erdogan and Obama, an agreement was signed according to which the United States was finally granted the right to use the Turkish Incirlik, Diyarbakir, Batman and Malatya air bases to bomb ISIS, and Turkey pledged to directly take part in these bombings. In Turkey, for the first time after the appearance of ISIS on the political map of the Middle East in June 2014, large-scale arrests of supporters of terrorist quasi-state commenced (to be fair, it must be said that the first dozens of radical Islamists were arrested as early as mid-July, before the terrorist attack). More than 500 people were imprisoned; and the border control was tightened: By the end of July, 500 foreigners had been deported for relations with ISIS, 1,100 were denied entry to Turkey, and 15,000 were put on the “black list”. ISIS did not forgive this and on July 23 the first clashes between the Turkish army and ISIS members took place. Scorpion bit the one who hid it in his sleeve, as B. Assad figuratively said speaking on the terrorist attacks in an interview with Russian journalists.

For his consent to the bombing of ISIS, Erdogan was allegedly granted the right to create a kind of no-fly zone over the western 90-km stretch of the Syrian-Turkish border officially to protect 1.8 million Syrian refugees from Assad, but in fact to help the anti-governmental forces (mainly the Free Syrian army). But this fig leaf was of little help to the Turkish president.

Having smoothed out his relations with the West and the United States over ISIS, and having thus obtained a pardon from the USA for taking a tougher stance on his domestic policies, Erdogan opened, apparently inadvertently, a new front, this time with the Kurds, and in particular with the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK).

They perceived the attack of July 20 as a provocation by the authorities (after all, ISIS was called the organiser by the Turkish authorities, not the Islamic State itself) and responded to terror with terror, killing a couple of police officers. And this is where the Turkish president seems to have made a fatal mistake, which hasn’t backfired on him yet.

Instead of allaying the situation, he decided to punish the power that he believes is interfering with his plans to overthrow Assad and is preventing political hegemony inside the country (in the elections of June 7, the People’s Democratic Party (HDP) won 80 seats in parliament, depriving Erdogan’s party of the majority), he broke the ceasefire with the Kurds that had been in effect since 2012 and unleashed military actions on those who stood for the HDP and the PKK. AKP activists simultaneously attacked the offices of the Democratic People’s Party across the country. Legal proceedings were filed against the party leader, S. Demirtas, for “inciting violence”.

In response, the Turkish Kurds, who decided that they were deceived when they were called for peace, but were declared war instead, took up arms and sabotaged a pipeline, along which oil flows to the camp of supporters of an independent Iraqi Kurdistan – Turkey and Israel (thanks to which 77% of the needs of the Jewish state are met) from its leader, M. Barzani, with whom Ankara shares special relationship. They do not believe in the anti-ISIS policies of the authorities, because they supposedly consider ISIS an Ankara’s tool in the fight against them. According to them, by encouraging the PKK to resume the civil war, they want to discredit the HDP, and then ban it and prevent them from taking part in elections. There are already calls for this from the Turkish ultra-nationalists, who have decided to support Erdogan. They demonise the HDP, declaring it a supporter of separatism.

There is every reason to believe that pursuing this policy of aggravation, Erdogan risks losing the upcoming parliamentary elections. In the current climate he is unlikely to succeed in unifying the nation, while fighting on three fronts – against Syria, ISIS and the PKK. Reforms are stalling in the country, the economic situation is not improving, and the desire to impose an ideology on the whole nation that not everyone shares (at least not the Kurds and the Kemalists) and monopolize power, could lead to increased social unrest. Bonapartism is not fashionable these days…

Pogos Anastasov, political analyst, Orientalist, exclusively for the online magazine “New Eastern Outlook.”

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

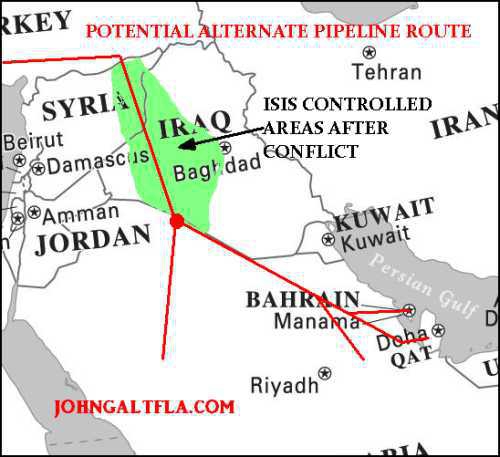

Le gazoduc Qatar-Turquie est un projet allant du champ irano-qatari «South Pars / North Dome» vers la Turquie, où il pourrait se connecter avec le gazoduc Nabucco pour fournir les clients européens ainsi que la Turquie.

Le gazoduc Qatar-Turquie est un projet allant du champ irano-qatari «South Pars / North Dome» vers la Turquie, où il pourrait se connecter avec le gazoduc Nabucco pour fournir les clients européens ainsi que la Turquie.

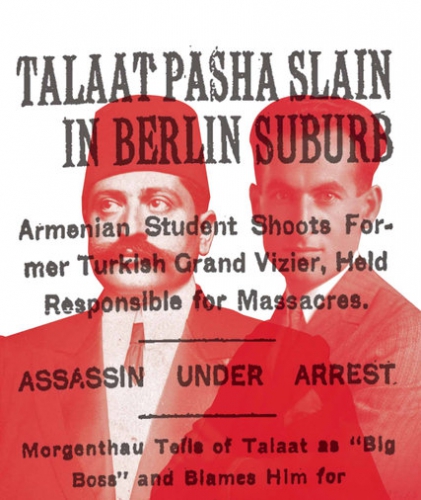

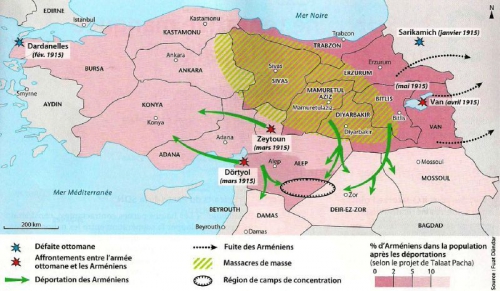

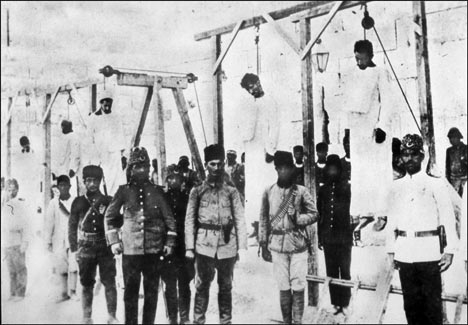

Christian soldiers — who, thanks to their new constitutional equal rights, could now serve in the military — were disarmed and put in work battalions, after which they were worked to death or slaughtered outright. On April 24, 1915, the Armenian community was decapitated. Some 250 prominent Armenians in Constantinople were arrested and subsequently murdered. In the Armenian homelands in the East, the genocide took place under the pretext of deportation and resettlement. Armenians packed and cataloged their valuables, handed over assets, and were marched out of their towns, where they were plundered and massacred, often with sickening Oriental sadism. Those who were not killed outright were marched to desert internment camps where they perished through disease, hunger, and violence. Between 800,000 and 1.4 million Armenians died, as well as more than half a million Greeks and Assyrians. Hundreds of thousands became refugees. By the end of the war, the Ottoman Empire had virtually eliminated its Armenian population.

Christian soldiers — who, thanks to their new constitutional equal rights, could now serve in the military — were disarmed and put in work battalions, after which they were worked to death or slaughtered outright. On April 24, 1915, the Armenian community was decapitated. Some 250 prominent Armenians in Constantinople were arrested and subsequently murdered. In the Armenian homelands in the East, the genocide took place under the pretext of deportation and resettlement. Armenians packed and cataloged their valuables, handed over assets, and were marched out of their towns, where they were plundered and massacred, often with sickening Oriental sadism. Those who were not killed outright were marched to desert internment camps where they perished through disease, hunger, and violence. Between 800,000 and 1.4 million Armenians died, as well as more than half a million Greeks and Assyrians. Hundreds of thousands became refugees. By the end of the war, the Ottoman Empire had virtually eliminated its Armenian population.

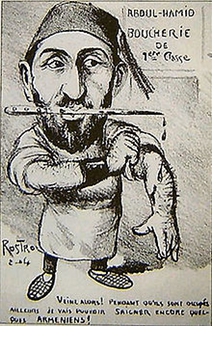

Or le malheur des Turcs, et de leurs victimes, aura été, il y a exactement un siècle, après une dernière année de règne ambigu d'Abdül-Hamid II, la victoire de ces habiles révolutionnaires. Ils admiraient la révolution jacobine française. Leur chef Enver pacha devint alors ce 24 avril 1909 le maître véritable du pouvoir. Un nouveau sultan, le fantoche Rechad Effendi allait régner nominalement sous le nom de Mehmed V jusqu'à sa mort en juillet 1918. Le grand vizir, et le parti de l'Union libérale, en même temps que les alliés de l'Ancien régime furent peu à peu éliminés, au fur et à mesure des désastres rencontrés lors des deux guerres italo-turque de 1911-1912 puis balkaniques de 1912-1913 qui avaient pratiquement mis un terme à la présence turque en Europe.

Or le malheur des Turcs, et de leurs victimes, aura été, il y a exactement un siècle, après une dernière année de règne ambigu d'Abdül-Hamid II, la victoire de ces habiles révolutionnaires. Ils admiraient la révolution jacobine française. Leur chef Enver pacha devint alors ce 24 avril 1909 le maître véritable du pouvoir. Un nouveau sultan, le fantoche Rechad Effendi allait régner nominalement sous le nom de Mehmed V jusqu'à sa mort en juillet 1918. Le grand vizir, et le parti de l'Union libérale, en même temps que les alliés de l'Ancien régime furent peu à peu éliminés, au fur et à mesure des désastres rencontrés lors des deux guerres italo-turque de 1911-1912 puis balkaniques de 1912-1913 qui avaient pratiquement mis un terme à la présence turque en Europe.

Yet, in Iraq, Libya, Egypt and Syria you have various regional nations and outside NATO powers (Turkey is a regional NATO power) that have different objectives. This reality is hindering the Muslim Brotherhood dream of America, Qatar and Turkey and this is clearly visible by the tenacity of Syria and the growing centralization of Egypt under el-Sisi. Therefore, while America, Qatar, Saudi Arabia and Turkey had no qualms in destabilizing Libya and Syria, the conflicting interests of so many nations is enabling a counter-revolution. This counter-revolution applies to Egypt and Syria fighting for independence because current political elites in both nations understand that failed states and subjugation awaits both nations if they fail.

Yet, in Iraq, Libya, Egypt and Syria you have various regional nations and outside NATO powers (Turkey is a regional NATO power) that have different objectives. This reality is hindering the Muslim Brotherhood dream of America, Qatar and Turkey and this is clearly visible by the tenacity of Syria and the growing centralization of Egypt under el-Sisi. Therefore, while America, Qatar, Saudi Arabia and Turkey had no qualms in destabilizing Libya and Syria, the conflicting interests of so many nations is enabling a counter-revolution. This counter-revolution applies to Egypt and Syria fighting for independence because current political elites in both nations understand that failed states and subjugation awaits both nations if they fail.

Ce sont finalement, la géopolitique et l’économie qui dictent l’agenda de la politique étrangère de l’Occident (et par extension de la Turquie) en Asie centrale et en Chine. Il s’agit d’une tentative d’étouffer le développement économique, tant de la Russie que de la Chine, et d’empêcher les deux puissances de poursuivre leur double démarche de coopération et d’intégration régionale. Ainsi considérée, la Turquie devient une pièce géante instrumentalisée pour garder la Russie et la Chine séparées mais aussi garder séparées la Chine et l’Europe. Il y a beaucoup de magie derrière le rideau proverbial.

Ce sont finalement, la géopolitique et l’économie qui dictent l’agenda de la politique étrangère de l’Occident (et par extension de la Turquie) en Asie centrale et en Chine. Il s’agit d’une tentative d’étouffer le développement économique, tant de la Russie que de la Chine, et d’empêcher les deux puissances de poursuivre leur double démarche de coopération et d’intégration régionale. Ainsi considérée, la Turquie devient une pièce géante instrumentalisée pour garder la Russie et la Chine séparées mais aussi garder séparées la Chine et l’Europe. Il y a beaucoup de magie derrière le rideau proverbial.

Nasrallah himself stated: “I want to ask the Christians before the Muslims: You are seeing what is taking place in Syria. I am not causing sectarian evocations. Let no one say that Sayyed is doing so. Not at all! Where are your churches? Where are your patriarchs? Where are your nuns? Where are your crosses? Where are the statues of Mary (pbuh)? Where are your sanctities? Where are all of these? What has the world done for them? What did the world do for them previously in Iraq? Aren’t these groups causing all of this in all the regions?”

Nasrallah himself stated: “I want to ask the Christians before the Muslims: You are seeing what is taking place in Syria. I am not causing sectarian evocations. Let no one say that Sayyed is doing so. Not at all! Where are your churches? Where are your patriarchs? Where are your nuns? Where are your crosses? Where are the statues of Mary (pbuh)? Where are your sanctities? Where are all of these? What has the world done for them? What did the world do for them previously in Iraq? Aren’t these groups causing all of this in all the regions?”

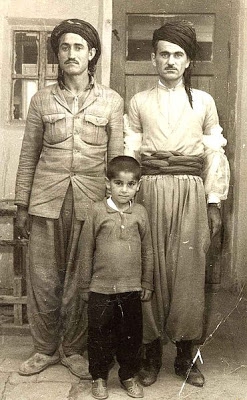

A partir de 1847, l’Empire ottoman connaît une zone administrative nommé « Kurdistan » mais elle est dissoute en 1864. Après l’effondrement de l’empire ottoman en 1918, les Alliés occidentaux victorieux promettent aux Kurdes de leurs accorder un Etat propre et le droit à l’auto-détermination mais, en bout de course, de larges portions de l’aire de peuplement kurde ont été attribuées à la Syrie (sous mandat français) et surtout à l’Irak (sous mandat britannique). Par ailleurs, les Turcs de Mustafa Kemal, par leur victoire dans leur guerre d’indépendance, conservent le reste du Kurdistan et contraignent les franco-britanniques à accepter une révision du Traité de Sèvres. Sous l’impulsion d’Atatürk, leader des forces indépendantistes et nationalistes turques, de nombreux Kurdes se joignent au mouvement antioccidental parce qu’on leur promet simultanément de larges droits à l’autonomie dans l’Etat turc nouveau qui doit s’établir après la victoire des forces nationalistes. Les kémalistes avaient en effet promis aux Kurdes que cet Etat nouveau serait binational. Ces promesses n’ont pas été tenues : le jeune Etat, né de la victoire des armes kémalistes, ne reconnait pas les Kurdes comme minorité ethnique lors de la signature du Traité de Lausanne de 1923. La réaction ne se fait pas attendre : plusieurs insurrections éclatent entre 1925 et 1938 dans l’aire de peuplement kurde de la nouvelle Turquie. Toutes sont matées par l’armée turque, supérieure en nombre et en matériels.

A partir de 1847, l’Empire ottoman connaît une zone administrative nommé « Kurdistan » mais elle est dissoute en 1864. Après l’effondrement de l’empire ottoman en 1918, les Alliés occidentaux victorieux promettent aux Kurdes de leurs accorder un Etat propre et le droit à l’auto-détermination mais, en bout de course, de larges portions de l’aire de peuplement kurde ont été attribuées à la Syrie (sous mandat français) et surtout à l’Irak (sous mandat britannique). Par ailleurs, les Turcs de Mustafa Kemal, par leur victoire dans leur guerre d’indépendance, conservent le reste du Kurdistan et contraignent les franco-britanniques à accepter une révision du Traité de Sèvres. Sous l’impulsion d’Atatürk, leader des forces indépendantistes et nationalistes turques, de nombreux Kurdes se joignent au mouvement antioccidental parce qu’on leur promet simultanément de larges droits à l’autonomie dans l’Etat turc nouveau qui doit s’établir après la victoire des forces nationalistes. Les kémalistes avaient en effet promis aux Kurdes que cet Etat nouveau serait binational. Ces promesses n’ont pas été tenues : le jeune Etat, né de la victoire des armes kémalistes, ne reconnait pas les Kurdes comme minorité ethnique lors de la signature du Traité de Lausanne de 1923. La réaction ne se fait pas attendre : plusieurs insurrections éclatent entre 1925 et 1938 dans l’aire de peuplement kurde de la nouvelle Turquie. Toutes sont matées par l’armée turque, supérieure en nombre et en matériels.