Source : Sheldon Wolin, The Nation

Ex: http://www.les-crises.fr

Traduit par les lecteurs du site www.les-crises.fr. Traduction librement reproductible en intégralité, en citant la source.

La guerre d’Irak a tellement accaparé l’attention du public que le changement de régime en train de s’accomplir chez nous est resté dans l’ombre. On a peut-être envahi l’Irak pour y apporter la démocratie et renverser un régime totalitaire, mais, ce faisant, notre propre système est peut-être en train de se rapprocher de ce dernier et de contribuer à affaiblir le premier. Le changement s’est fait connaître par la soudaine popularité de deux expressions politiques autrefois très rarement appliquées au système politique américain. « Empire » et « superpuissance » suggèrent tous les deux qu’un nouveau système de pouvoir, intense et s’étendant au loin, a pris naissance et que les anciens termes ont été supplantés. « Empire » et « superpuissance » symbolisent précisément la projection de la puissance américaine à l’étranger, mais, pour cette raison, ces deux termes en obscurcissent les conséquences domestiques.

La guerre d’Irak a tellement accaparé l’attention du public que le changement de régime en train de s’accomplir chez nous est resté dans l’ombre. On a peut-être envahi l’Irak pour y apporter la démocratie et renverser un régime totalitaire, mais, ce faisant, notre propre système est peut-être en train de se rapprocher de ce dernier et de contribuer à affaiblir le premier. Le changement s’est fait connaître par la soudaine popularité de deux expressions politiques autrefois très rarement appliquées au système politique américain. « Empire » et « superpuissance » suggèrent tous les deux qu’un nouveau système de pouvoir, intense et s’étendant au loin, a pris naissance et que les anciens termes ont été supplantés. « Empire » et « superpuissance » symbolisent précisément la projection de la puissance américaine à l’étranger, mais, pour cette raison, ces deux termes en obscurcissent les conséquences domestiques.Imaginez comme cela paraîtrait étrange de devoir parler de “la Constitution de l’Empire américain” ou de “démocratie de superpuissance”. Des termes qui sonnent faux parce que “Constitution” signifie limitations imposées au pouvoir, tandis que “démocratie” s’applique à la participation active des citoyens à leur gouvernement et à l’attention que le gouvernement porte à ses citoyens. Les mots “empire” et “superpuissance” quant à eux sont synonymes de dépassement des limites et de réduction de la citoyenneté à une importance minuscule.

Le pouvoir croissant de l’état et celui, déclinant, des institutions censées le contrôler était en gestation depuis quelque temps. Le système des partis en donne un exemple notoire. Les Républicains se sont imposés comme le phénomène unique dans l’Histoire des États-Unis d’un parti ardemment dogmatique, fanatique, impitoyable, antidémocratique et se targuant d’incarner la quasi-majorité. A mesure que les Républicains se sont faits de plus en plus intolérants idéologiquement parlant, les Démocrates ont abandonné le terrain de la gauche et leur base électorale réformiste pour se jeter dans le centrisme et faire discrètement connaître la fin de l’idéologie par une note en bas de page. En cessant de constituer un véritable parti d’opposition, les Démocrates ont aplani le terrain pour l’accès au pouvoir d’un parti plus qu’impatient de l’utiliser pour promouvoir l’empire à l’étranger et le pouvoir du milieu des affaires chez nous. Gardons à l’esprit qu’un parti impitoyable, guidé par une idéologie et possédant une base électorale massive fut un élément-clé dans tout ce que le vingtième siècle a pu connaître de partis aspirant au pouvoir absolu.

Les institutions représentatives ne représentent plus les électeurs. Au contraire, elles ont été court-circuitées, progressivement perverties par un système institutionnalisé de corruption qui les rend réceptives aux exigences de groupes d’intérêt puissants composés de sociétés multinationales et des Américains les plus riches. Les institutions judiciaires, quant à elles, lorsqu’elles ne fonctionnent pas encore totalement comme le bras armé des puissances privées, sont en permanence à genoux devant les exigences de la sécurité nationale. Les élections sont devenues des non-évènements largement subventionnés, attirant au mieux une petite moitié du corps électoral, dont l’information sur les affaires nationales et mondiales est soigneusement filtrée par les médias appartenant aux firmes privées. Les citoyens sont plongés dans un état de nervosité permanente par le discours médiatique sur la criminalité galopante et les réseaux terroristes, par les menaces à peine voilées du ministre de la justice, et par leur propre peur du chômage. Le point essentiel n’est pas seulement l’expansion du pouvoir du gouvernement, mais également l’inévitable discrédit jeté sur les limitations constitutionnelles et les processus institutionnels, discrédit qui décourage le corps des citoyens et les laisse dans un état d’apathie politique.

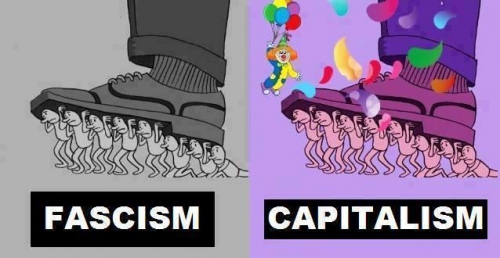

Il ne fait aucun doute que d’aucuns rejetteront ces commentaires, les qualifiant d’alarmistes, mais je voudrais pousser plus loin et nommer le système politique qui émerge sous nos yeux de “totalitarisme inversé”. Par “inversé”, j’entends que si le système actuel et ses exécutants partagent avec le nazisme la même aspiration au pouvoir illimité et à l’expansionnisme agressif, leurs méthodes et leurs actes sont en miroir les uns des autres. Ainsi, dans la République de Weimar, avant que les nazis ne parviennent au pouvoir, les rues étaient sous la domination de bandes de voyous aux orientations politiques totalitaires, et ce qui pouvait subsister de démocratie était cantonné au gouvernement. Aux États-Unis, c’est dans les rues que la démocratie est la plus vivace – tandis que le véritable danger réside dans un gouvernement de moins en moins bridé.

Autre exemple de l’inversion : sous le régime nazi, il ne faisait aucun doute que le monde des affaires était sous la coupe du régime. Aux États-Unis, au contraire, il est devenu évident au fil des dernières décennies que le pouvoir des grandes firmes est devenu si dominant dans la classe politique, et plus particulièrement au sein du parti Républicain, et si dominant dans l’influence qu’il exerce sur le politique, que l’on peut évoquer une inversion des rôles, un contraire exact de ce qu’ils étaient chez les nazis. Dans le même temps, c’est le pouvoir des entreprises, en tant que représentatif du capitalisme et de son pouvoir sans cesse en expansion grâce à l’intégration de la science et de la technologie dans sa structure même, qui produit cette poussée totalitaire qui, sous les nazis, était alimentée par des notions idéologiques telles que le Lebensraum.

On rétorquera qu’il n’y a pas d’équivalent chez nous de ce que le régime nazi a pu instaurer en termes de torture, de camps de concentration et autres outils de terreur. Il nous faudrait toutefois nous rappeler que, pour l’essentiel, la terreur nazie ne s’appliquait pas à la population de façon générale ; il s’agissait plutôt d’instaurer un climat de terreur sourde – des rumeurs de torture – propre à faciliter la gestion et la manipulation des masses. Pour le dire carrément, il s’agissait pour les nazis d’avoir une société mobilisée, enthousiaste dans son soutien à un état sans fin de guerre, d’expansion et de sacrifices pour la nation.

Tandis que le totalitarisme nazi travaillait à doter les masses d’un sens du pouvoir et d’une force collectifs, Kraft durch Freude (“la Force par la Joie”), le totalitarisme inversé met en avant un sentiment de faiblesse, d’une inutilité collective. Alors que les nazis désiraient une société mobilisée en permanence, qui ne se contenterait pas de s’abstenir de toute plainte, mais voterait “oui” avec enthousiasme lors des plébiscites récurrents, le totalitarisme inversé veut une société politiquement démobilisée, qui ne voterait quasiment plus du tout. Rappelez-vous les mots du président juste après les horribles évènements du 11 septembre : “unissez-vous, consommez, et prenez l’avion”, dit-il aux citoyens angoissés. Ayant assimilé le terrorisme à une “guerre”, il s’est dispensé de faire ce que des chefs d’États démocratiques ont coutume de faire en temps de guerre : mobiliser la population, la prévenir des sacrifices qui l’attendent, et appeler tous les citoyens à se joindre à “l’effort de guerre”.

Au contraire, le totalitarisme inversé a ses propres moyens d’instaurer un climat de peur générale ; non seulement par des “alertes” soudaines, et des annonces récurrentes à propos de cellules terroristes découvertes, de l’arrestation de personnages de l’ombre, ou bien par le traitement extrêmement musclé, et largement diffusé, des étrangers, ou de l’île du Diable que constitue la base de Guantanamo Bay, ou bien encore de la fascination vis-à-vis des méthodes d’interrogatoire qui emploient la torture ou s’en approchent, mais également et surtout par une atmosphère de peur, encouragée par une économie corporative faite de nivelage, de retrait ou de réduction sans pitié des prestations sociales ou médicales ; un système corporatif qui, sans relâche, menace de privatiser la Sécurité Sociale et les modestes aides médicales existantes, plus particulièrement pour les pauvres. Avec de tels moyens pour instaurer l’incertitude et la dépendance, il en devient presque superflu pour le totalitarisme inversé d’user d’un système judiciaire hyper-punitif, s’appuyant sur la peine de mort et constamment en défaveur des plus pauvres.

Ainsi les éléments se mettent en place : un corps législatif affaibli, un système judiciaire à la fois docile et répressif, un système de partis dans lequel l’un d’eux, qu’il soit majoritaire ou dans l’opposition, se met en quatre pour reconduire le système existant de façon à favoriser perpétuellement la classe dirigeante des riches, des hommes de réseaux et des corporations, et à laisser les plus pauvres des citoyens dans un sentiment d’impuissance et de désespérance politique, et, dans le même temps, de laisser les classes moyennes osciller entre la peur du chômage et le miroitement de revenus fantastiques une fois que l’économie se sera rétablie. Ce schéma directeur est appuyé par des médias toujours plus flagorneurs et toujours plus concentrés ; par l’imbrication des universités avec leurs partenaires privés ; par une machine de propagande institutionnalisée dans des think tanks subventionnés en abondance et par des fondations conservatrices ; par la collaboration toujours plus étroite entre la police locale et les agences de renseignement destinées à identifier les terroristes, les étrangers suspects et les dissidents internes.

Ce qui est en jeu, alors, n’est rien de moins que la transformation d’une société raisonnablement libre en une variante des régimes extrémistes du siècle dernier. Dans de telles circonstances, les élections nationales de 2004 constituent une crise au sens premier du terme, un tournant. La question est : dans quel sens ?

Source : Sheldon Wolin, The Nation, le 26/02/2012

Traduit par les lecteurs du site www.les-crises.fr. Traduction librement reproductible en intégralité, en citant la source.

Mouffe: I think that criticizing an agonistic perspective for not being critical enough of capitalism is basically a difference of strategy and again this is where the strategy of ‘engagement with’ or, using a term of Gramsci - ‘a war of position’ - is what is the one I propose. I imagine that the person that you have in mind is Slavoj Žižek because he's the one who is criticising the agonistic approach for being a liberal one. But his position is a rhetorical revolutionary one which does not propose any strategy. We want the end of capitalism, sure, but how are we going to do it, with whom? It's very rhetorical to say: the end of capitalism. I think the question is to engage with existing institutions, and this requires a long process. Some people still would say we need a revolution like the Soviet revolution. If we are to learn something from the experience, the tragic experience of really existing socialism, is precisely that this strategy of making a complete new start doesn’t work. You can't just end a society in one move and start from scratch - it’s not possible. It’s only possible by using terror. ‘A war of position’ is better strategy; we need to target specific institutions in order to transform them. For me at the moment the most important task is to end the hegemony of neoliberalism and of financial capitalism. Of course that's not going to be the end of capitalism. The aim is to create a society that will not be submitted to the logic of the market. They might still remain some sectors which are going to be organised by capitalists but the main society will not be one in which the market controls everything. But that cannot be done one day. There are of course proposals in the line of Hardt and Negri who believe that the development of the self-organisation of the multitude is going to make capitalism completely irrelevant. They accept that it is going to be a process and they do not advocate any kind of Jacobin form of revolution but they believe that the state will disappear and I don't believe that. Some of those experiences of new forms of living are important but they are not enough. The power of capitalism is not going to disappear because we have a multitude of self-organizing outside the existing institutions. We need to engage with those institutions in order to transform them profoundly. I saw a few years ago a film called Was tun? (What is to be done). It was about the anti-globalization movement and the role of Hardt and Negri’s strategy. At the end of the film they asked them “what should we do?” And Negri answered “wait and be patient” and Hart answered “follow your desire.” That’s their strategy. They believe that there is some kind of law of history that is necessarily going to lead to ‘absolute democracy’. It's very similar to the traditional Marxist view that capitalism is its own gravedigger but I don't think that's the case. Capitalism is not going to disappear simply by us being patient and waiting, we need to engage with it, and that is the strategy of agonistic engagement. It's not a total revolution, that’s not possible, it's ‘a war of position’ in order to transform the existing institutions.

Mouffe: I think that criticizing an agonistic perspective for not being critical enough of capitalism is basically a difference of strategy and again this is where the strategy of ‘engagement with’ or, using a term of Gramsci - ‘a war of position’ - is what is the one I propose. I imagine that the person that you have in mind is Slavoj Žižek because he's the one who is criticising the agonistic approach for being a liberal one. But his position is a rhetorical revolutionary one which does not propose any strategy. We want the end of capitalism, sure, but how are we going to do it, with whom? It's very rhetorical to say: the end of capitalism. I think the question is to engage with existing institutions, and this requires a long process. Some people still would say we need a revolution like the Soviet revolution. If we are to learn something from the experience, the tragic experience of really existing socialism, is precisely that this strategy of making a complete new start doesn’t work. You can't just end a society in one move and start from scratch - it’s not possible. It’s only possible by using terror. ‘A war of position’ is better strategy; we need to target specific institutions in order to transform them. For me at the moment the most important task is to end the hegemony of neoliberalism and of financial capitalism. Of course that's not going to be the end of capitalism. The aim is to create a society that will not be submitted to the logic of the market. They might still remain some sectors which are going to be organised by capitalists but the main society will not be one in which the market controls everything. But that cannot be done one day. There are of course proposals in the line of Hardt and Negri who believe that the development of the self-organisation of the multitude is going to make capitalism completely irrelevant. They accept that it is going to be a process and they do not advocate any kind of Jacobin form of revolution but they believe that the state will disappear and I don't believe that. Some of those experiences of new forms of living are important but they are not enough. The power of capitalism is not going to disappear because we have a multitude of self-organizing outside the existing institutions. We need to engage with those institutions in order to transform them profoundly. I saw a few years ago a film called Was tun? (What is to be done). It was about the anti-globalization movement and the role of Hardt and Negri’s strategy. At the end of the film they asked them “what should we do?” And Negri answered “wait and be patient” and Hart answered “follow your desire.” That’s their strategy. They believe that there is some kind of law of history that is necessarily going to lead to ‘absolute democracy’. It's very similar to the traditional Marxist view that capitalism is its own gravedigger but I don't think that's the case. Capitalism is not going to disappear simply by us being patient and waiting, we need to engage with it, and that is the strategy of agonistic engagement. It's not a total revolution, that’s not possible, it's ‘a war of position’ in order to transform the existing institutions.

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

Et c’est vrai qu’il manque deux choses essentielles à un (très) bon roman : finesse et substance, tant dans les personnages (qui manquent vraiment de profondeur) que dans l’avènement du système totalitaire.

Et c’est vrai qu’il manque deux choses essentielles à un (très) bon roman : finesse et substance, tant dans les personnages (qui manquent vraiment de profondeur) que dans l’avènement du système totalitaire.

Le livre récent de Christian E. Roques

Le livre récent de Christian E. Roques