Robert Steuckers:

Answers Given to the Scandinavian Group and Internet Forum “Oskorei / motpol.nu”)

Picture: Walking along Heidegger's path in Todtnauberg, Germany, July 2010 (Photo, copyright: AnaR).

Picture: Walking along Heidegger's path in Todtnauberg, Germany, July 2010 (Photo, copyright: AnaR).

Why did you found « Synergies Européennes » ?

Initially I had no intention to found any group or subgroup in the broad family of New Right clubs and caucuses. But as, for many reasons, cooperation with the French branch around Alain de Benoist seemed to be impossible to resume, I first decided to retire completely and to devote myself to other tasks, such as translations or private teaching. This transition period of disabused withdrawal lasted exactly one month and one week (from December 6th, 1992 to begin January 1993). When friends from Provence phoned me during the first days of 1993 to express their best wishes for the New Year to come and when I told them what kind of decision I had taken, they protested heavily, saying that they preferred to rally under my supervision than under the one of the always mocked “Parisians”. I answered that I had no possibility to rent places or find accommodations in their part of France. One day after, they found a marvellous location to organise a summer course. Other people, such as Gilbert Sincyr, generously supported this initiative, which six months later was a success due to the tireless efforts of Christiane Pigacé, a university teacher in political sciences in Aix-en-Provence, and of a future lawyer in Marseille, Thierry Mudry, who both could obtain the patronage of Prof. Julien Freund. The summer course was a success. But no one had still the idea of founding a new independent think tank. It came only one year later when we had to organise several preparatory meetings in France and Belgium for a next summer course at the same location. Things were decided in April 1994 in Flanders, at least for the Belgians, Italians, Spaniards, Portuguese and French. A German-Austrian team joined in 1995 immediately after a summer course of the German weekly paper “Junge Freiheit”, that organized a short trip to Prague for the participants (including Sunic, the Russian writer Vladimir Wiedemann and myself); people of the initial French team, under the leading of Jean de Bussac, travelled to the Baltic countries, to try to make contacts there. In 1996, Sincyr, de Bussac and Sorel went to Moscow to meet a Russian team lead by Anatoly Ivanov, former Soviet dissident and excellent translator from French and German into Russian, Vladimir Avdeev and Pavel Tulaev. We had also the support of Croatians (Sunic, Martinovic, Vujic) and Serbs (late Dragos Kalajic) despite the war raging in the Balkans between these two peoples. In Latin America we’ve always had the support of Ancient Greek philosophy teacher Alberto Buela, who is also an Argentinian rancher leading a small ranch of 600 cows, and his old fellow Horacio Cagni, an excellent connoisseur of Oswald Spengler, who has been able to translate the heavy German sentences of Spengler himself into a limpid Spanish prose. The meetings and summer courses lasted till 2003 and the magazines were published till 2004. Of course, personal contacts are still held and new friends are starting new initiatives, better adapted to the tastes of younger people. In 2007 we started to blog on the net with “euro-synergies.hautetfort.com” in seven languages with new texts every day and with “vouloir.hautetfort.com” only in French with all the articles in our archives. This latest initiative is due to a rebuilt French section in Paris. These blogging activities bring us more readers and contacts than the old ways of working. Postage costs were in the end too high to let the printed stuff survive. The efforts of our American friend Greg Johnson, excellent translator from French into English, has opened us new horizons in the world, where English is more largely known than other European languages, except Spanish. The translations of Greg can be read on “counter-currents.com”. Tomislav Sunic with all his connections in the New World, in England and Scandinavia has played a key role in this step forward. He will force me to write in English in the next future, just as you do now, and to abandon my habit to write mainly in French and sometimes in German, languages that I master better that English. The next long interview in English will be the one that Pavel Tulaev submitted to me some days ago (January 2011). In fact, when I entered as a full member the New Right groups in September 1980, after having been drilled during a special summer course in Provence in July 1980 in the frame of the so-called “Temistoklès Savas Promotion” (T. Savas was a Greek friend who had just died in a motorbike accident in the Northern Greek mountains), I promised to Prof. Pierre Vial, who was at that time one of the main leaders of the celebrated GRECE-group, to lead a metapolitical battle till my last breath. So things are still going on as they ought to.

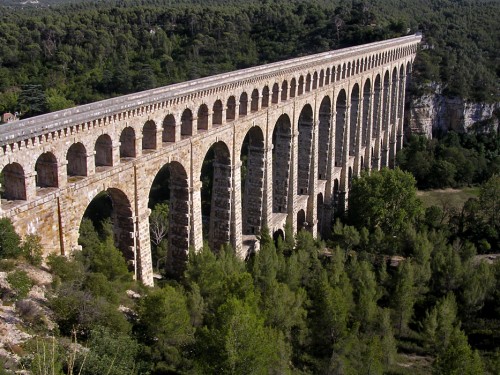

The marvellous water bridge of Rocquevafour were formerly the GRECE Summer Courses were given

Now the very purposes of “Synergies Européennes” or “Euro-Synergies” were to enable all people in Europe (and outside Europe) to exchange ideas, books, views, to start personal contacts, to stimulate the necessity of translating a maximum of texts or interviews, in order to accelerate the maturing process leading to the birth of a new European or European-based political think tank. Another purpose was to discover new authors, usually rejected by the dominant thoughts or neglected by old right groups or to interpret them in new perspectives.

“Synergy” means in the Ancient Greek language, “work together” (“syn” = “together” and “ergon” = “to work”); it has a stronger intellectual and political connotation than its Latin equivalent “cooperare” (“co” derived from “cum” = “with”, “together” - and “operare” = “to work”). Translations, meetings and all other ways of cooperating (for conferences, individual speeches or lectures, radio broadcasting or video clips on You Tube, etc.) are the very keys to a successful development of all possible metapolitical initiatives, be they individual, collegial or other. People must be on the move as often as possible, meet each other, eat and drink together, camp under poor soldierly conditions, walk together in beautiful landscapes, taste open-mindedly the local kitchen or liquors, remembering one simple but o so important thing, i. e. that joyfulness must be the core virtue of a good working metapolitical scene. When sometimes things have failed, it was mainly due to humourless, snooty or yellow-bellied guys, who thought they alone could grasp one day the “Truth” and that all others were gannets or cretins. Jean Mabire and Julien Freund, Guillaume Faye and Tomislav Sunic, Alberto Buela and Pavel Tulaev were or are joyful people, who can teach you a lot of very serious things or explain you the most complicated notions without forgetting that joy and gaiety must remain the core virtues of all intellectual work. If there is no joy, you will inevitably be labelled as dull and lose the metapolitical battle. Don’t forget that medieval born initiatives like the German “Burschenschaften” (Students’ Corporations) or the Flemish “Rederijkers Kamers” (“Chambers of Rhetoric”) or the Youth Movements in pre-Nazi Germany were all initiatives where the highest intellectual matters were discussed and, once the seminary closed, followed by joyful songs, drinking parties or dance (Arthur Koestler remembers his time spent at Vienna Jewish Burschenschaft “Unitas” as the best of his youth, despite the fact that the Jewish students of Vienna considered in petto that the habits of the Burschenschaften should be adopted by them as pure mimicking). Humour and irony are also keys to success. A good cartoonist can reach the bull’s eye better than a dry philosopher.

Provence village of Lourmarin where three Summer courses of "Synergies Européennes" were held

How do you view the proper relationship between the national state and the European Community?

Well, it depends which national state you are talking about. Some states have a strong political personality, born out of their own history. Others are remnants of former greater empires, like many states in Central Europe, which once upon a time were parts of the Austrian-Hungarian Habsburgs Empire. France, Britain and Sweden, for instance, have such a well-defined strong personality. Belgium, the country in which I was born, is a more or less artificial state, being a remnant entity of the Austrian-Hungarian Empire and of the medieval German Holy Roman Empire but having been strongly under the influence of France due to the use of French language in the Southern part of the kingdom and among the elites, even in Flemish speaking provinces. Croatia has been part of the Hungarian Crown’s Lands within the Austrian-Hungarian Empire and still desires to have closer links with Austria, Germany and Italy. Bosnia cultivates both the nostalgia of the Austrian-Hungarian Empire and of the Ottoman Empire. The Netherlands has certainly a stronger identity than Belgium or Croatia but this identity has the tendency to develop in two very different directions: a see-oriented direction towards Britain and the United States, or a land-oriented direction towards Germany and Flanders in Belgium. Countries with a weaker identity have the tendency to be more pro-European than the ones that have this strong history born personality I’ve just mentioned. But on the other hand Britain is experimenting nowadays a process of devolution, especially in Scotland and in a lesser extent in Wales. France is still theoretically the embodiment of a strongly centralised state but regional and local identities are flourishing as an alternative to the official universalistic ideology of the “République”, leading to a compelled acceptation of mass immigration imposed to the native populations, that, as a result, instinctively take up local or regional roots, which look more genuine and gentle, being seen as in complete accordance with one’s “deepest heart”.

To theorise the “proper relationship” between the national state and the European Union, you have to look out for a functioning model, in which several types of identities, be they linguistic or confessional, are overlapping and displaying a kind of mosaic patchwork on a smaller scale than Europe, which is obviously such a patchwork, especially in its central continental areas. The only functioning model we have is the Swiss model. This democratic model was born in an intersection area in the middle of the European continent, where three main European languages and one local language meet as well as two different Christian faiths, Protestantism and Catholicism, Swiss Protestantism being once more divided between Lutherans in German speaking Basle and Calvinist in French speaking Geneva, with remnants of Zwingli’s Protestantism around Zurich. Most German speaking Swiss are otherwise Roman Catholics, while most French speaking Swiss are Protestants except in the Canton of Jura. To coordinate optimally all these differences, what could lead to endless conflicts, the Swiss political system invented a form of federalism that allowed people to live in peace while keeping their differences alive. This could be a model for all European states and for regions within these states. The federal level in Switzerland is a “slim” and efficient level. Most matters are left in the hands of local politicians and officials. Moreover the Swiss system foresees the referendum as a decision making instrument at both federal and cantonal levels. The people can introduce a claim at local or national level, leading to the organisation of a referendum for all kind of matters: the building of a bridge, ecological problems, introduction or suppression of a railway or a bus connection, etc. In 2009 and in 2010, two referendums took place at federal level: the first one was introduced by a rightist populist party to forbid the building of minarets in Swiss cities and towns, in accordance to the very old ecological and town-planning laws of the Swiss Confederation, mostly accepted or introduced by leftist “progressive” political forces in former times. In November 2010, also very recently, people voted to expel all criminal foreigners out of the country, avoiding in this way the most painful effects of mass immigration. Such people’s initiatives would be impossible in other European countries, despite the fact that expelling criminals cannot be considered as “racist” (as non criminal foreigners cannot be expelled) or as hostile to particular religious faiths, as no religion tolerates crimes as acceptable patterns of behaviour.

Therefore, the possible adoption of this Swiss model, beyond its latest anti-immigration aspects, would allow other European peoples to vote in order to coin a policy-making decision about actual problems and so to avoid being arrogantly ordained by ukases imagined by the fertile fantasy of Eurocratic eggheads in Brussels. The adoption of the Swiss model implies of course to reduce most of the biggest states in Europe into smaller entities or to adopt a federal system like in Spain, Austria, Belgium or Germany, plus the possibility to organise referendums like in Switzerland, as this is not the case in the otherwise complete federal states I’ve just mentioned. This is a lack of democracy. The main problem would be France, where this kind of federalism and of democracy has never been introduced. Nevertheless, the demand for the referendum system is growing in France, as you can read it on www.polemia.com, where former New Right exponent Yvan Blot is currently resuming all his ideas, suggestions and critics about this topic.

Picture: The Splügenpass at the Italian-Swiss boarder where Synergon's Summer Course 1996 was held (Photo: RS)

Picture: The Splügenpass at the Italian-Swiss boarder where Synergon's Summer Course 1996 was held (Photo: RS)

The introducing of a general federal system in Europe with broad devolution within the existing states is not accepted everywhere. In Italy, where the federalist Lega Nord is continuously successful in the Northern provinces of the country, partisans of a strong state argue that a balkanization in the disguise of a general federalisation would weaken many state’s instruments that have been firmly settled in former times and enable the present-day state foundations or practices to avoid absorption by globalist American-lead agencies or concerns. This is of course an actual risk. So all the state institutions having been developed in Europe to enhance autarky (self-sufficiency) at whatever level possible must be kept out of any dissolution process implied by any form of devolution.

A policy consisting of introducing a referendum to avoid people being crushed by too centralised states or by eurocrats, of a devolution allowing this genuine form of democracy to be established everywhere and of keeping alive all institutions aiming at self-sufficiency was perhaps the hope of Solzhenitsyn for his dear old Russia. Such a policy ought to be made secure according to historical Russian and Swiss models, but cannot of course be implemented by the current political personnel. Needless to say that such a personnel is corrupt but not only that. It is brainwashed and duped by all kind of silly ready-made ideologies or blueprints, invented mostly in American think tanks, their European counter-parts and the main media agencies. To summarize it, these ideologies aim at weakening the societies by mocking their traditional patterns of behaviour, at generalizing the ideological assets of neo-liberalism in order to let globalization be thoroughly implemented in every corner of the world and at reducing Europe to remain once for ever a disguised colony of the United States.

Therefore, there is the need to replace such a deceiving personnel by new teams in every European country. These new teams cannot be the usual populist alternative parties as they are mostly unaware of the dangers of neo-liberalism, i.e. the new universalistic ideology suggested and imposed by the most dangerous think tanks of the left and of the establishment: from the camouflaged Trotskites within the social-democratic parties to the “new philosophers” in France, who paved the way to a subtle mixture of “political correctness”, apparent libertarianism, an apparently vehement and staunch defence of the human rights, avowed antifascism and anticommunism (communism being the result of a worship of mostly German “thought masters” (“maîtres-à-penser”) like Hegel or Marx). The usual populist parties never managed to develop a discourse about and against this real danger jeopardizing Europe’s future. They were each time trapped by one aspect or another of this subtle mixture, especially all the anticommunist aspects.

A “new team” should give following answer to the now well-established official ideology of the main medias:

- A defence of the social systems in Europe or of an adaptation/modernization of them, erasing the corruptions that deposited during several decades; the model would be of course the partnership existing since the foundation of the Federal Republic of Germany between workers and bosses; the investment model called the “Rhine Model” by the French thinker Michel Albert, where the capital is permanently invested in new technologies, in Research & Development, in academic think tanks, etc. The defence of the so-called socialist social systems in Europe aims essentially at preserving the families’ patrimony (especially modest working-class families because it gives them a safe security net in case of recession), at securing the future of the school and academic networks (now disintegrating under the iron heel of the banksters’ neoliberalism) and at securing a free and good functioning medical system in all European countries. It has often been said that the “non merchant sectors” were suffering due to all kind of imposed shortages (in the name of an alleged economic efficiency) and to the poor salaries earned by teaching or medical personnel. The “anti-shopkeeper” mentality of the so-called “right” or “new right” is an old heritage linking us to the ideals of the Scotsman Thomas Carlyle and the American poet Ezra Pound. If we want to translate these core ideas into a political programme, we’ll have to elaborate in each European country a specific defence of the “non merchant sectors”, as a civilization is measured not by material and transient productions but by the excellence of its medical and academic systems. We always were defenders of the primacy of culture against the iron heel of banks and economics.

The Varese Lake, Lombardia, where Synergon's Seminar 1995 and Synergon's Summer Course 2000 was held

- The notion of human rights, as they are propagated by the mainstream medias and by the official American think tanks, is a would-be universalistic ideology, aiming at replacing all the old messianic faiths, be they a religious bias or a Hegelian or Marxist tinted ideology (“the main narratives” of Jean-François Lyotard). But the mainstream notion of human rights are not merely an ideology, it is an instrument fabricated by strategists at the time of President Jimmy Carter, in order to have a constant opportunity to meddle in the affairs of alien countries, in order to weaken them (a strategy already suggested by Sun Tzu). The Chinese could observe very early that drift from a pious reference to human rights towards manipulation and subversion and reacted in arguing that every civilization should be permitted to adapt the notion of human rights to its own core cultural patterns. If the Chinese have the right to adapt, why wouldn’t we Europeans not be entitled to give our own interpretation of human rights within the frame of our own civilization? And above all to be allowed to make a clear distinction, when human rights are evoked, between what is genuine in the true defence of citizens’ rights and obligations and what is the result of an offensive attack perpetrated by an alien “soft power” in order to destabilize our countries’ policy in whatever matters. We should have the courage to denounce every abuse in the manipulating of the human rights’ topic when they are solemnly summoned up only in order to promote any American imperialist project in Europe, as, for instance, the war against Yugoslavia in 1999 was. The justification put forward to start this war was the so-called breach of human rights committed by the Serbian government against the Albanians composing the majority of Kosovo’s population. But in the end it brought to power an infamous gang in this American-backed secessionist province of Kosovo, currently accused of trafficking human organs, weapons and prostitutes. Where are the rights of the people having been bereft of their organs by force or of the poor girls attracted by seducing work contracts in Western Europe, then beaten, locked up in some dreary cellar and finally forced to be on the game? All the media orchestrated humbug about human rights promoted by Carter, Clinton and Albright ended exactly in the worst breaches in common law, that were deleterious for thousands and thousands of victims. The American discourse about human rights is deceitfulness and cant and nothing else. The real purpose was to establish a gigantic military base in Kosovo, namely “Camp Bondsteel”, in order to replace the abandoned bases in Germany after the Cold War and the German reunification and to occupy the Balkans, an area which, since Alexander the Great, allows every audacious conqueror to control Anatolia and all areas beyond it, namely Iraq and Persia. A “new team” in Europe should ceaselessly stigmatize and vilify these abuses and clearly tell the public opinion of their respective countries what are the real purposes behind each American human rights policy. The “new team” should work a bit like Noam Chomsky in the United States, who indefatigably reveals what is Washington’s hidden agenda in every part of the world.

To adopt a Swiss model with referendum at local and national level, to reject vehemently the anti-autarky policies induced by the neo-liberal ideology and economical theory, to reject also the mainstream bias of “political correctness” and to perceive the real geopolitical and strategic intentions hidden behind each American step are not capabilities that the political personnel in Europe can currently display. Therefore you won’t have a proper relationship between the national states (and the people as an ethnic reality) and the highest institutions of the European Union, as long as a fooled political pseudo-elite is ruling these latest. You need “new teams” to induce a “proper relationship”.

What is your analysis of the current European Union and it’s future and potential?

The answer to the question you ask here could be the stuff of a whole book. Indeed to answer it properly and in a complete way, you need to evoke the all story of the European integration process, starting with the founding act of the CECA/EGKS, i.e. the “European Community of Coal and Steel”, in 1951. After that you had the “Treaty of Rome” in 1957, launching the so-called “Common Market” and, later, the “Treaty of Maastricht” and the “Treaty of Lisbon”. It seems useless to resume now the entire history of the European “Eurocratic” institutions, especially at a present time when they are totally degenerated by liberal and neo-liberal ideas that of course weaken them and make them in a certain way superfluous. The core idea at the very beginning was to create an “autonomous market”, leading to a certain autarky, which was absolutely possible when the six founding countries possessed large parts of Africa and could so exploit the most important industrial and mineral resources. The decolonization and the support that the United States provided to the independence movements in Africa bereft Europe of a direct access to the main resources. The core idea of an autarky within a certain “Eurafrican” commonwealth has no real significance anymore. This new situation could already have been foreseen in October 1956 when the United States tolerated (and indirectly supported) the Soviet invasion of Hungary despite the opinion of their main allies in Europe and condemned the French-British intervention in Egypt. The year 1956 announced the fate of Europe: the European powers had no right to intervene within Europe itself, as Hungary had freed itself from Soviet yoke and as the treaties signed after 1945 foresaw the withdrawal of all Soviet troops out of the country after some months. The European powers, including Britain, had no right anymore to intervene in Africa in order to keep order.

The decolonization process left Europe without a necessary “Ergänzungsraum”, i. e. a “complementary space”, that could be administrated from European capitals and give African people the efficiency of well drilled executives, what they lack since then, precipitating the whole Black continent into a terrible misery. But autarky doesn’t mean the direct access to mineral resources: it means first of all “food autarky”. Few European countries are (or were at the end of the 80s, just before the collapse of the Soviet block) really independent at food level or are now able to produce food excesses. Only Sweden, Hungary, France and Denmark were. For the excellent French demographist Gaston Bouthoul Denmark is the best example of a well-balanced agriculture. This small Scandinavian country is able to produce food excesses that make of it an “agricultural superpower” in Europe: one should simply remember that Danish peasants furnished 75% of the food for the German Wehrmacht during WW2. Without the Danish food excesses, Hitler’s armies wouldn’t have resisted so long in Russia, in Northern Africa and in the West (Italy).

Perugia, Umbria (Italy) where the common "New Right" Conference (with Dr. Marco Tarchi, Dr. Alessandro Campi, Alain de Benoist, Michael Walker and Robert Steuckers) was held in February 1991 and where Synergon's Summer Course 1999 took place

The core idea of autarky survived quite long within the European institutions. We should remember the last plan trying to materialise autarky, the so-called “Plan Delors”, proposing a policy of large scaled public works and of favouring telecommunications and public transports within the EU area. The EU has no future if it remains what American economists called “a penetrated system” at the time of the Weimar Republic in Germany when American big business tried a disguised colonisation of the defeated Reich through the Young and Dawes Plans. The EU is now a penetrated system where not only American multinationals are carving important segments of the inner European market but also the new Chinese State’s companies and where the textile industry is now entirely dependant from delocalized factories settled in Turkey or Pakistan. Unemployment reaches astronomical figures in Europe because of delocalisation.

Recently the German weekly magazine “Der Spiegel” has published figures showing that Europe is experimenting now a real decay. More and more European countries are leaving the hit parade of the 20 most important economies on the world. The results of the PISA inquiry about the levels reached by school systems reveals also a general decay of the European standards. University teacher and former student and translator of Carl Schmitt, Julien Freund, thought us in his important book “La fin de la Renaissance” (1981) that decay comes when you begin to hate yourself, to despise what you are and to abhor your own past. The whole “Vergangenheitsbewältigung” not only in Germany but in all European countries, where children and teenagers are subtly induced to loathe themselves and their fatherlands, has repercussions on the general economics of the entire continent. The EU can only survive when it finds its ideological roots again, i. e. the very notion of autarky. Otherwise the process of decay will amplify tremendously and lead to the complete disappearance of the European peoples and civilisation. In this process the EU area may become, as a kind of new “Eurabia” or Euro-Turkey or Afro-Europe, an appendix of a “Transatlantic Union” under US leadership.

Well, let us now turn to the real question, the question that matters. Are we socialists or not? If we are, what’s the difference between us and the conventional socialists or social democrats? What’s the difference between the synergist anti-liberal with his New Right background and the Marxist or Post-Marxist we find in all the parliaments in Europe and of course in the European Parliament where they constitute the second main group after the Christian Democrats of the EPP? Well, the conventional socialists would say that they get their inspiration from their holy icon Marx and from his followers of the 2nd International, even if a born-again Marx would fiercely mock their liberal and permissive bias with the acidity he always used to lash verbally his foes. The problem is that the socialism of the direct heirs of the 2nd International is a type of socialism without a frame, consisting mainly of irresponsible promises emitted by cynical politicians in order to grasp as many mandates or seats as possible. Long before Marx wrote his well-known communist manifesto, there was an economical genius in Germany called Friedrich List, who opposed the free trade ideology of Britain at that time. Free trade meant in the first half of the 19th Century a generalized colonial system in the entire world, where Britain would have been the world only workshop or factory, while the rest would have remained underdeveloped only producing raw materials for the Sheffield or Manchester mills. Included all European countries of course. List asserted that every country had the genuine right to develop its own territorial assets. As the British fleet was the instrument enabling the British Crown to be ubiquitous and reach the harbours on all shores where it could get the raw materials and sell the products of England’s factories, List suggested an inner development of all countries in the world by inner colonization (fertilization and cultivation of all abandoned lands), building of railways and canals in order to boost communications. List inspired the German government under the leading of Bismarck, the small Belgian kingdom which was an economical power having experimented an actual industrial revolution immediately after Britain, the French positivists for the necessity of starting an inner agricultural colonization of the former Gallic mainland and above all the US government that had to face the huge problem of developing the gigantic land space between the Atlantic and the Pacific. List is the intellectual father of the Transcontinental Railway and of the canals linking the Lakes and the Saint Lawrence River. He is the real intellectual father of the industrial power of the United States. On the other hand he inspired anti-colonialists in the former Third World, especially India and China: Gandhi, who wanted the Indians to cultivate cotton and weave their own clothes with it, and Dr. Sun Ya Tsen, founder of the Chinese Republic in 1911, were more or less inspired by List’s theories and practical suggestions. The Chinese National-Republican economist Kai Sheng Chen, who theorized the very important notion of “armed economy”, was a pupil of List and of Ludendorff, who adapted the peaceful ideas of List in the context of WW1. Taiwan and South Korea have proved that Kai Sheng Chen’s ideas can be successfully realized.

In the present-day United States the caucus around Lyndon LaRouche has produced an excellent analysis of the opposition between the Free Trade system and List’s practical views of a world of free autarkic areas. You can find a long documentary on the Internet about this dual interpretation given by the LaRouche’s group. Many Europeans would of course object that LaRouche’s vision of the economical history of the Western World during these two last centuries is quite over-simplified. Of course it is. But the core of this interpretation is correct and sound, whereas the over-simplification made of the all corpus a good didactical instrument. There is indeed an opposition between Free Trade (neo-liberalism, reaganomics, thatcherite economics, Chicago Boys, Hayek’s theories, etc.) and List’s idea of a harmonious juxtaposition of autarkies on the world map. The LaRouche caucus never quotes List (as far as I know) and says Lincoln and McKinley were opponents to the Free Trade, a position that, according to Lyndon LaRouche, explains their assassinations. Both were killed after a plot aiming at cancelling all political steps towards a North American autarkist system. Teddy Roosevelt and Woodrow Wilson were supporters of the Free Trade system and of a British-American alliance along the lines theorized by an almost forgotten proponent of geopolitics, Homer Lea, author of a key book, “The Day of the Saxons”. Lea, having got a degree in West Point, had been dismissed for medical reasons and turned to pure theory, advocating an eternal alliance of Britain and the United States. We can read in his book today the general principles of a control of the South Asian “rimlands” by both Anglo-Saxon sea powers, especially Afghanistan, and of a control of the Low Countries and Denmark to avoid any push forward of Germany in the direction of the North Sea or any push forward of France in the direction of the harbours of Antwerp and Rotterdam.

The LaRouche caucus aims obviously at emphasizing the role in history of some icon figures of America like Abraham Lincoln of Franklin Delano Roosevelt. Nevertheless Free Trade and Continental Autarky are truly a couple of opposites that you cannot deny, even if the binary antagonism isn’t certainly so sharp as explained by LaRouche’s team. For instance, it is true that F. D. Roosevelt started his career as a US President by launching the huge project of the “Tennessee Valley”, foreseeing the building of a series of colossal dams to tame the violent waters of the Tennessee, Mississippi and Missouri rivers. The New Deal and the “Tennessee Valley Project” were distinctly continental purposes but they were torpedoed by the proponents of Free Trade, who in the end imposed a new Free Trade policy, an alliance with Britain, despite the fact that Chamberlain tried to create an inner Commonwealth autarky. This shift in Roosevelt’s policy lead to war with Japan and Germany because the failure of the New Deal policy implied to choose for exportations and to abandon the project of developing the inner Northern American market. If you have to prevent other areas in the world to develop their own closed markets, you must destroy them, according to the good old colonial logics, and get them as exportation markets. So the United States were doomed to destroy the European system of the Germans and the “Co-Prosperity Sphere of East Asia” under the leadership of Japan.

To summarize our position, let us remember that Russia developed and came out of underdevelopment under the “Continental Project” of Serguei Witte and Arkady Stolypin, who were either dismissed after a gossip campaign or assassinated by a crazy revolutionist. China after its communist isolation under Mao turned to a form of autarkist model under Deng Xiao Ping, leading the country to an unchallenged economical success. Putin in Russia is trying, with less success, to adopt the same guidelines. But the “Continental Autarkists” are assembling nowadays under the direction of the informal Shanghai Group or of the BRIC (Brazil, Russia, India, China). Europe and the United States will have to adapt in order to avoid complete decay. The key idea to successfully perform this adaptation is the good old project of Friedrich List. And the American can refer to one of his most brilliant students: Lawrence Dennis, who coined a project for “continental autarky”, being influenced by the “continentalist” school of South America, where he lived for a quite long time as a diplomat.

The Flemish village of Munkzwalm where many technical meetings and several Spring Courses were held between 1989 and 1995

Q.: Is it important for the pro-European activist to be familiar with geopolitics?

Of course. If you are a pro-European activist, you should perceive Europe as a geopolitical entity, surrounded by possible foes and having to control militarily its periphery, for instance by preventing the North African states to become sea powers again or to prevent any alien power to provide them sea power tools or missiles able to strike the Mediterranean coasts of Europe. The whole history of Europe is the history of a long defence battle against Barbary Coast pirates and their Ottoman rulers. Once this danger eliminated, Europe could develop and prosper. Nowadays mass immigration within the boarders of European countries replace the external danger of Barbary Coast piracy or of Ottoman threat by introducing parallel economical circuits and mafia systems of drug bosses, the so-called “diaspora mafias”, who weaken the whole social system by literally milking money from the well established European social security system and by earning colossal fortunes from drug dealing (Moroccan cannabis which amounts to 70% of the entire European consumption or Central Asian heroin dispatched by Turkish mafias). The type of danger has changed but comes always from the very next periphery of Europe. Racialist as well as so-called anti-racist arguments are preposterous in such matters, as you don’t need to develop a “racialist argumentation” to criticize mass immigration: you simply have to stress the fact that international authorities like the UNESCO or the UNO have urged the EU to finance alternative crops in Morocco, in order to replace the huge fields of cannabis in the Northern parts of the country by useful plantations. But the money given by the EU has been used to triple the area where cannabis crops are cultivated! So Morocco, the Moroccan citizens or the European citizens of Moroccan origin who trust drugs from the Rif area are lawbreakers in front of the EU, UNESCO and UNO policy. Anti-racist arguments, caucuses and legislations, trying to crush all people criticizing mass immigration, are in fact tools in the hand of the secret lobbies and the drug bosses that try to weaken Europe and to maintain our homelands in a permanent state of debility and decrepitude.

For you Swedes, as fellow countrymen of Rudolf Kjellén and Sven Hedin, geopolitics is of course a genuine part of your political and cultural heritage. Moreover the Russian Yuri Semionov, author of a tremendously interesting book on Siberia, was a refugee in Sweden in the Thirties. In Swedish libraries you must find a lot about the first theories on geopolitics (as it was Kjellén who coined the word), about the travelogues of Hedin, explorer of Central Asia and Tibet, and maybe about Semionov’s works. At the very beginning of the so-called New Right project, geopolitics was still taboo. There was certainly an implicit geopolitics among diplomats or generals, which was not genuinely different from the former geopolitical endeavours of the previous decades, but the very word was taboo. You couldn’t talk about geopolitics without being accused of trying to resume Nazi geopolitics, which had been set once for all as “esoteric”. Karl Haushofer, the German pupil of Kjellén, had been depicted as a crazy mystical mage having disguised his belonging to a so-called secret society of the “Green Dragon” behind a weak discourse about history, geography and international affairs. When you read Haushofer and his excellent “Zeitschrift für Geopolitik” (which survived him under the name of “Geopolitik” in the Fifties), you find comments on current affairs, reasonable reflections about frontiers within and outside Europe, interviews of foreign diplomats and excellent analyses about the Pacific area but no pseudo-Chinese or neo-Teutonic esoteric humbug. At the end of the Seventies, things changed. In the United States, Colin S. Gray decided to break definitively the taboo on geopolitics. As an Anglo-Saxon proponent of geopolitics, Gray was of course a pupil of Sir Halford John MacKinder, of Homer Lea and of their pupil Spykman. But he explained that Haushofer’s geopolitics was a continental reaction against MacKinder’s sea power geopolitics. Haushofer was so rehabilitated and could be studied again as a normal proponent of geopolitics and not as a mystical crackpot.

In the group of students, who followed the works of the New Right groups in Brussels at the end of the Seventies and was lead by late Alain Derriks, we had of course purchased a copy of Gray’s book but, at the same time, we discovered the book of an Italian general, Guido Giannettini, “Dietro la Grande Muraglia” (“Beyond the Great (Chinese) Wall”). This book was extremely well written, offered simultaneously a historical approach and present-day analyses, and opened wide perspectives. Giannettini had observed how the whole international chessboard had been turned upside down in 1972, when Kissinger and Nixon had coined a new implicit alliance with communist China. Formerly, the American lead Western world had faced a giant Eurasian communist block, embracing China and the USSR, even when the relationship between Moscow and Beijing wasn’t optimal anymore or could even become sometimes frankly antagonist (with a clash between both armies along the River Amur in Far Eastern Siberia). After the defeat of Germany in 1945, Europe had been divided, according to the rules settled at Teheran and Yalta, into a Western part dominated by NATO and an Eastern part under the direction of the Warsaw Pact. At that time Euro-nationalists around my fellow countryman Jean Thiriart, rejected both systems and pleaded for an alliance with China and the Arab world (Egypt, Syria and Iraq) in order to loose the choking entanglement of both NATO and Warsaw Pact. In Thiriart’s clearly outlined strategy for his Europe-wide but tiny movement, Chinese and Arabs would have had for task to keep Americans and Soviets busy outside Europe, so that the pressure would be lighter to bear in Europe and lead, if possible, to a successful liberation movement, aiming at restoring Europe’s independence and sovereignty. When Americans and Chinese joined their forces to contain and encircle Soviet Russia, the wished Euro-Chinese alliance to disentangle Yalta’s yoke in Europe became a sheer impossibility. On the other side, the Arabs were too weak and not interested in a European revival, as they feared a come back of the colonial powers in their area, as during the Suez affair in October 1956. Giannettini’s option for a Euro-Russian block became the only possible choice. Thiriart agreed. So did we. But our views about a possible future Euro-Russian alliance were confused at the very beginning: we couldn’t accept the occupation of Eastern Europe and even less the partition of Germany that is, geographically speaking, the core of Europe. On the other hand, the American disguised occupation was also for us an unacceptable situation, especially after De Gaulle’s breach with NATO and the new independent course in international affairs that it induced, according to Dr. Armin Mohler. After the Israeli victory of June 1967 with the help of Mirage III fighters and bombers, France’s new world policy lead to the exportation of Dassault jet fighters in Latin America, South Africa, India and Australia. It could have generated a new European based aeronautical industry, as in 1975 the Scandinavian and Low Countries air forces had the choice between the Mirage IV, the Saab Viggen jet, a new model produced by a future common French-Swedish project, or the American F-16. European independence was only possible if Europe could build an independent aeronautical industry, based on merges between already existing aeronautical companies. The fact that after corruption affairs the Scandinavian and Low Countries armies opted for the American F-16 jet ruined the possibility of a jointed independent European aeronautical industry. It was the purchase of the F-16 jets and the subsequent ruin of a possible French-Swedish fighter project that induces our small group to reject definitively all forms of pendency in front of the Western hegemonic power. But what else if the Iron Curtain seemed to be not removable and if the inner European situation was apparently a stalemate, bound to remain as such eternally?

Other readings helped us to improve our views. I’ll quote here two key books that shifted unequivocally our viewpoints: Prof. Louis Dupeux’ doctor paper on German “national bolshevism” at the time of the Weimar Republic in the Twenties and Prof. Alexander Yanov’s UCLA paper on the Russian “New Right” in the last years of Soviet rule, at the end of Brezhnev’s era and just before Gorbachev’s perestroika. Dupeux helped us to understand the relevancy of the Soviet-German tandem in the Twenties, starting with the Rapallo Treaty of 1922 (between Rathenau and Chicherin). This relevancy could explain us the cause of the ephemeral Ribbentrop-Molotov Pact of August 1939. A European-Russian tandem could therefore offer the possibility of independence and Continental-Eurasian strength. But such a tandem was impossible under communist rule. But was communism as monolithic as it was described in the Western press and medias? In his paper Yanov divided Soviet-Russian political thought into two categories and each of these two categories again in two others: the Zapadniki (the Westerners) and the Narodniki (the proponents of Russian identity). You could find dissident Zapadniki in the emigration and pro-regime Zapadniki within the Soviet institutions (i. e. Marxist of the old school as Marxism was a Western importation). You could also find dissident Narodniki in the emigration, such as Solzhenitsyn, and pro-regime Narodniki in the Soviet-Russian academic world, such as the writer Valentin Rasputin, who wrote “rural” novels criticizing the reckless industrialisation and “electrification” of old traditional Russian villages or areas. For Yanov the Russian New Right was incarnated in all the Narodniki, be they dissidents or not, and all Narodniki were of course dangerous compeers and rascals as they challenged dominant Western as well as Soviet principles. So our position, and the one staunchly defended in Germany by former Gulag prisoner Wolfgang Strauss (arrested during the East German riots of June 1953), was to hope for a Narodniki political or metapolitical revolution in Russia and in Eastern Europe, giving the possibility to create an International of Narodniki, from the Atlantic coasts to the Pacific Ocean, challenging the Western hemisphere and its liberal leftist ideology. Meanwhile after Reagan’s election in November 1981 the missile crisis swept all over Europe. The piling up of missiles on both sides of the Iron Curtain risked in case of war to destroy definitively all European countries. The reaction was passionate especially in Germany: more and more puzzled voices required a new neutrality status, to avoid implication in a military system of warmongers, and pleaded for a withdrawal from NATO, as the Treaty’s Organisation was lead by an external hegemonic power, which didn’t care for the safety of Europe and was ready to unleash a horrible nuclear apocalypse upon our countries. A neutrality status, as suggested by General Jochen Löser in Germany (in “Neutralität für Mitteleuropa”), implied also to promote a kind of “Third Way” system, which would have been a synthesis between state socialism and market capitalism. “Wir Selbst” of Siegfried Bublies (Koblenz) was the leading magazine, which backed a policy of NATO withdrawal and Central European neutrality, a “Third Way” (for instance the one theorized by the Slovak economist Ota Sik), a reconciliation with Russia (according to Ernst Niekisch or Karl-Otto Paetel as dissidents both of the Weimar Republic and of the Third Reich), the devolution movements in Western and Eastern Europe, and the new dissidents in the Soviet dominated block. The magazine had been created in 1979 and remained till the very beginning of the 21st Century the main forum for alternative thought with a humanist touch in all Europe. I mean “humanist” in the sense given to this word by the main non Westernized dissidents of Eastern Europe, being no Narodniki in the narrow sense of this expression. The years 1982 and 1983 were determined by the pacifist revolt throughout Europe, especially in Germany around an interesting thinker like air force Lieutenant-Colonel Alfred Mechtersheimer, and in the Low Countries but also in Britain, where huge demonstrations were held to prevent the dispatch of American missiles. Our small group supported the pacifist movement against the conventional positions of many other Rightist or even New Right clubs (including de Benoist at that time, who accused us of being the “Trotskites” of the movement, positioning himself as a kind of Stalin-like Big Brother!). The new pacifism and neutralism ceased to thrive when Gorbachev declared he intended to launch a glasnost and perestroika policy to soften the Soviet rule. Once Gorbachev promised a new policy, we could only wait and see, without abandoning all necessary scepticism.

During the second half of the Eighties, we hoped for a new world, in which the Iron Curtain would one day disappear and the dominant systems would gently evolve towards a “Third Way”. In 1989, when the Berlin Wall was suppressed, we all thought very naively that the liberation of Europe and of Russia was imminent. The Gulf War and the dissolution of Yugoslavia, the invasion of Iraq and of Afghanistan proved that Europe was in fact totally unable to take an original decision in front of the world events, with the slight exception of the short French, German and Russian opposition to the invasion of Iraq in 2003, an opposition naively hailed as the new “Paris-Berlin-Moscow Axe” but an Axe that couldn’t of course prevent the unlawful invasion of Saddam Hussein’s country. So we still are in a desolate state of subjugation despite the fact that Europe now counts 27 states in full membership.

Let us come back to geopolitical theory. In 1979, when we discovered Giannettini’s book, I read General Heinrich Jordis von Lohausen’s book “Mut zur Macht”, which was a very good summary and actualisation of Kjellen’s ideas, as well as of all notions formerly defined by Haushofer and his broad team (Walter Pahl, Gustav Fochler-Hauke, Otto Maull, Walter Wüst, R. W. von Keyserlingk, Erich Obst, etc.). I wrote a small paper for my end examination of “International Affairs”, which was read with interest by the teacher, who found Lohausen’s positions interesting but still “dangerous”. Geopolitics in June 1980, date when I passed the examination with brio (18/20! Thank you, dear General von Lohausen!), was still taboo in “poor little Belgium”. It wouldn’t last a long time before this “dangerousness” would definitively belong to the past. The French intellectual world produced successively many excellent geopolitical studies: I’ll only quote here Yves Lacoste’s journal “Hérodote”, the accurate maps of Michel Foucher, the encyclopaedic studies of Hervé Coutau-Bégarie and the courses of Ayméric Chauprade (who, as a teacher in the French High Military Academy, was recently sacked by Sarközy because he couldn’t accept the coming back of France in the commanding structures of NATO as a full member state). In the Anglo-Saxon world, the best books on the matter are those produced by the British publishing house “I. B. Tauris” (London).

You cannot concentrate only on geopolitics as a mean strategic way of thinking. To use the tools properly you need an accurate knowledge in history that the shelves in Anglo-Saxon bookshops offer you in abundance. Then to be a good proponent of geopolitics you need to study lots of maps, especially historical maps. I therefore collect historical atlases since I got the first one in my life, the official one you had to buy when you reached the third year in the secondary school. When I was 15, I bought my very first German book, volume two of the “DTV-Atlas zur Weltgeschichte”, at Brussels’ flea market. The book lies now since about forty years on my desk! Indispensable tools are also the atlases of the British University teacher Colin McEvedy, which were translated into Dutch for Holland’s schools. McEvedy sees history as a regular succession of collisions between “core peoples” (Indo-Europeans, Turkish-Mongolic tribes, Semitic nomads of the Arabic peninsula, etc.), which he perceives as balls moving on a kind of huge billiard table, which is Eurasia with all its highways across the steppes. By reading McEvedy’s comments on the maps he draws we can understand history as permanent systolic and diastolic movements of “core peoples” (together with assimilated alien tribes or vanquished former foes) against each other, in order to control land, highways or sea accesses to them. And what is European history if not a long process of resisting more or less successfully Mongolic or Turkish assaults in the East and Hamito-Semitic incursions in the South? Next to McEvedy, the most interesting historical atlas in my collection is the one that a Swiss professor produced, namely Jacques Bertin’s “Atlas historique universel – Panorama de l’histoire du monde”, where you’ll find even more precise maps than the ones of McEvedy. Also, the German DTV-Atlas (which exists in an English version published at Penguin’s publishing house in Britain), McEvedy’s works and Bertin’s panorama are the tools that I use since many years. They have been my paper companions since I was a teenager.

What is your analysis of the actual and ideal relationship of Europe and Russia, Turkey and the United States?

To answer your question here in a complete and satisfying way, I should rather write a couple of thick books instead of babbling some insufficient explanations! Indeed your question asks me in fact to summarize in some short sentences the whole history of mankind. I suppose that, for historical reasons, Swedes don’t perceive Russia and Turkey as citizens of Central or Western Europe would perceive these countries. Swedes must remember the attempt of King Charles XII to restore what was seen as the “Gothic Link” between the Baltic and the Black Sees by becoming the heir of the Polish-Lithuanian State in decay at his time: therefore he had to wage war against Russia and try to obtain the Turkish alliance. During the Soviet-Finnish war of winter 1939-40, Swedes were terribly worried because the move of Stalin’s Red Army to recuperate Finland as a former Tsarist province implied a future Soviet control of the Baltic See reducing simultaneously Swedish sovereignty and room for manoeuvre in these waters. It was also jeopardizing the fragile independence of the Baltic States.

Vlotho, Low Saxony (Germany) where a lot of meetings, conferences and Summer courses took place

Russia still wants to have access to the Atlantic via the Baltic see routes but in a less aggressive way than in Soviet times, when a messianic ideology was running the agenda. After the disappearing of the Iron Curtain, we are back to the situation we had in 1814. Once Napoleon Bonaparte had been eliminated and together with him the tone-downed Bolshevism of his time, i. e. the blood drenched French revolution ideology, Europe was a more or less united block nicknamed in Ancient Greek language the “Pentarchy” (The “Five Powers”), stretching from the Atlantic to the Pacific coasts. We often forget nowadays that Europe was a strategic united block between 1814 and 1830, i. e. only during fifteen years. This unity allowed the pacification of Spain in 1822-23, the Greek independence from the Ottoman Empire in 1828 and later the crushing of Barbary Coast piracy by the landing of French troops in present-day Algeria in 1832. But the “Pentarchy” ceased to be a harmonious symphony of allied traditional powers when Belgium become independent from the King of Holland: indeed, Britain (in order to destroy the sea power of Holland, the industrial capacities in present-day Belgium’s Walloon provinces and the potentialities of the Indonesian colonial realm of the United Low Countries Kingdom) and France (aiming at recuperating Belgium and the harbour of Antwerp as well as a portion of the Mosel Valley in Luxemburg, leading to the very middle of German Rhineland in Koblenz) supported the rather incoherent Belgian independence movement while the other powers (Prussia, Austria and Russia) supported the Dutch King and his United Kingdom of the Low Countries. France, which started in the Thirties of the 19th Century to carve its African Empire not only in Algeria but also in present-day Gabon and Senegal, and Britain, which was already a world empire whose cornerstone was India, became very soon Extra-European realms deriving their power from wealthy colonies and were therefore not more interested in the strategic unity of Europe, as the genuine civilisation area of all the people of our Caucasian kinship. The competition between European powers to get colonies implied that colonial rivalries could perhaps end in inner European conflicts, what happened indeed in 1914. The spirit of 1814 was kept alive by the “Drei Kaisersbund”, the “Alliance of the three Emperors” (United Germany after 1871, Austria-Hungary and Russia), which unfortunately started to disintegrate after Bismarck’s withdrawal in 1891 and due to the French-Russian economical-financial alliance under Tsar Alexander III (cf. the limpid book of Gordon Craig and Alexander L. George, “Zwischen Krieg und Frieden. Konfliktlösung in Geschichte und Gegenwart”, C. H. Beck, Munich, 1984; this book is a history of European diplomacy from the Treaty of Vienna in 1814 to WW1, where the authors describe the gradual disintegration of the “Pentarchy”, leading to the explosion of 1914; both authors remember also that Nixon and Kissinger tried to re-establish a kind of “Pentapolarity”, with China, Japan, the United States, Europe and Soviet Russia, but the attempt failed or was reduced to nought by the new human rights’ diplomacy of Carter. The only possible present-day “Pentapolarity” is represented by the “BRIC”-system, with Brazil, Russia, Iran, India, China and maybe, in a next future, post-Mandela South Africa).

Sababurg Castle, along the "Märchenstrasse" ("Fairy Tales Road"), Hessen (Germany), where the German friends usually held their regular meetings

In the first decade of the 20th Century, the “Entente” was not an obvious option at the very beginning: Russia and Britain were still rivals in Central Asia and on the rimland of South Asia; Britain and France were rivals in Sudan as Britain couldn’t tolerate a French military settlement on the Nile River (the Fashoda incident in 1898), a situation which would have cut the British possessions in the Southern part of Africa from the Egyptian protectorate in the North; we should remember here that Cecil Rhodes’ project was to link Cape Town to Cairo by a British managed Trans-African railway, after the elimination of the German colony of Tanganyka or a possible occupation of Belgian Katanga. Even if already grossly decided in 1904, the French-British-Russian alliance, known as the Entente, was far to be a sure fact before the fatidic year of 1914. The Anglo-Russian dispute in Persia had still to be settled in 1907. Moreover the three Entente powers hadn’t yet shared their part of the pie on the rimlands, as France had to accept first the de facto English protectorate in Egypt. In return for this acceptation, Britain accepted to support France’s interests in Morocco against the will of the German Emperor, who wanted to extend the Reich’s influence to the Sherifan Kingdom in North Africa, threatening to close the Mediterranean and to reduce to nought the key strategic importance of Gibraltar. For all these reasons, it is obviously not sure that Russian efficient ministers as Witte or Stolypin would have waged a war, as Russia was still economically and industrially to weak to sustain a long term war against the so-called Central Powers, i.e. Austria, Germany and the Ottomans, especially as China and Japan could possibly take advantage in the Far East of a debilitated Russia on the European stage.

The problem is that we Europeans cannot escape the necessity of using the Siberian raw materials and the gas and oil of the Caucasian, Central Asian and Russian fields. The weakness of Europe lays in its lack of raw materials (nowadays 90% of the rare earths, indispensable for high tech electronic devices, have to be bought in China). Europe could save itself from the Ottoman entanglement by conquering America and by circumnavigating Africa and arriving in the Indian harbours without having to pass through Islam dominated areas. Europeans aren’t visceral colonialists: they carved colonial empires despite their will, simply to escape an Ottoman-Muslim invasion.

The European-Turkish relationship has always been conflictual and remains today as such. It is not a question of race or even of religion, although both factors ought of course to be taken reasonably into account. Religion played certainly a key role as the Seldjuks had turned Muslim before attacking and beating the Byzantine Empire in 1071 but one forgets too often that at the same time other Turkish tribes, known as the Cumans, attacked Southern Russia and moved in the direction of the Low Danube without having turned Muslim: their faith war still Pagan-Shamanic. They nevertheless coordinated their wide scale action with their Muslim cousins. Muslim and Pagan-Shamanic Turks took the Pontic area (Black Sea as Pontus Euxinus) in a tangle: the Pagan Cumans in the North, the Muslim Seldjuks in the South. It is neither a question of race as present-day Turkey is a mix of all possible neighbouring peoples, tribes and ethnic kinships. It isn’t a joke to say that you have now Turks of all colours, like on an advertisement panel of Benetton! The European Danubian, Balkanic (Bosnians, Greeks, Albanians) and Ukrainian contribution to the ethno-genesis of the present-day Turkish population is really important, as are the parts of converted local Byzantine Greeks or Armenians or as are also the Sunni Indo-European Kurds. The Arab-Syrian influence is also clear in the South. The Turkish danger is that the Turks, whatever their real origin may be, still see themselves as the heirs of all the Hun, Mongolic and Turkish tribes that moved westwards to the Atlantic. Sultan Mehmed, who took Constantinople in 1453, kept in his mind the idea of the general move of Turkish tribes westwards but added to his geopolitical vision the one that moved the Byzantine general Justinian, who wanted at the beginning of the 7th Century to conquer again all the Mediterranean area till the shores of the Atlantic. Mehmed’s vision was also a merge of Turkish and Byzantine geopolitics. In his own eyes, he was the Sultan and the Byzantine Basileus at the same time and wanted to become also Pope and Emperor, once his armies would have taken both Rome (“the Red Apple”) and Vienna (“the Golden Apple”). Mehmed even thought that one day such a shift as a “translatio imperii ad Turcos” could happen, like there had been a “translatio imperii ad Francos” and “ad Germanos”, just after the definitive crumbling down of the Roman Empire.

The idea of moving westwards is still alive among Turks. The strong Turkish desire to become a full member of the EU means the will to pour the Anatolian demographic overpopulation into the demographically declining European states and to transform them in Muslim Turkish dominated countries. This statement of mine is not a mean reflection of an incurable “Turkophobic” obsession but is purely and simply derived from an analysis of Erdogan’s speech in Cologne in February 2008. Erdogan urged the Turkish immigration in Germany and in other European countries not to assimilate, as “assimilation is a crime against mankind” because it would wipe out the “Turkishness” of Turkish people, and urged also to create autonomous Turkish communities within the European states, that would welcome the new immigrants by marriage of by so-called “family gathering”. Later Erdogan and Davutoglu threaten to back the Turkish mafias in Europe, would the authorities of the EU postpone once more the admission of Turkey as a full member state. Every serious political personality in Europe has to reject such a project and to struggle against its possible translation into the everyday European reality. A migration flood of totally uneducated workforces into Europe would lead to high joblessness and let the social security systems collapse definitively. It would mean the end of the European civilisation.

The Turks are plenty aware of the key position their country has on the world map. Would I be a Turk, I would of course staunchly support Erdogan and Davutoglu. But I am not and cannot identify myself to such an alien vision of geopolitics. I wouldn’t care if all the efforts of the new Turkish geopolitics would be directed towards the Near East, as the Near East needs a hegemonic regional power to get rid of the awful chaos in which it is now desperately squiggling. It wouldn’t perhaps not be so easy for the Turks to become again the hegemonic power in an Arab Near East as conflicts were frequent between Ottomans and Arab nationalists, especially since the end of the 19th Century when Sultan Abdulhamid started a centralisation policy, which was achieved by the strongly nationalist Young Turks in power since 1908. Arab liberal nationalists contended this new Young Turkish nationalist rule, which was not more genuinely Islamic, universal and Imperial-Ottoman but strictly Turkish national, stressing the superiority of the Turks within the Ottoman Empire, reducing simultaneously the Arabs to second-class citizens. The challenging Arab nationalists were severely crushed at the eve of WW1 (public hangings of Arab liberal intellectuals were common in Syrian or Lebanese towns at that time). But a renewed Turkish policy in the Near East cannot in principle collide frontally with the vital and paramount European interests, except of course if it would dominate the Suez Canal zone and control this essential portion of the sea route leading from West Europe to the Far East: one should not forget that the Zionist idea, i. e. the idea of settling Jews in the area between Turkish Anatolia and Mehmet Ali’s successful Egypt of the first half of the 19th Century, that was supported by France, was an idea shaped in the late 1830s in the English press and not in the mind of Rabbis in Eastern European ghettos. The idea had already been evoked by Prince Charles de Ligne during the war between the Ottoman Empire and the coalition of Russia and Austria in the 1780s as a means to weaken the Turks and to create a focal point of troubles on another front, far from the Balkans, Crimea and the Caucasus; Napoleon wanted also to settle Jews in Palestine in order to prevent a future Turkish domination in the Suez area, as the French at that time, by supporting the Mameluks of Egypt against their Turkish masters, already had the intention to dig a canal between the Mediterranean and the Red Sea. Zionism is also not a genuine ideology born in Jewish ghettos but an idea forged artificially by the British to use the Jews as mere puppets. This role of Israel as a simple puppet state explains also why the relationship between Turkey and Israel are worsening now as the renewed Ottoman diplomacy of Davutoglu induces the Turkish state to resume his previous influences in the Arab Near East or Fertile Crescent. This could lead to a complete reverse of alliances in the region: voices in the United States are pleading for a new Iranian-American tandem between Mesopotamia and the Indus River which would fade or dim the usual alliance between Ankara, Washington and Tel Aviv. Such a shift would be as important as the Nixon-Kissinger renewed diplomacy of 1971-72, when suddenly China, the former “rogue state”, turned instantaneously to be the best ally of the States. It would also rule out many oversimplifying ideologists who have opted for cartoonlike pro-Zionist, pro-Palestinian (or pro-Hamas or pro-Hizbollah) or pro-Iranian positions in order to support either a Western Alliance or an Anti-Western/Anti-American coalition on the international chessboard. Things might or even may be completely turned upside down within a single decade. The Anti-American pro-Iranian ideologist of today may become a pro-Zionist Anti-American tomorrow if he wants to remain Anti-American and if he is not turned still crazier by the crumbling down of his too schematic worldview as many Western Maoists did in the 1970s, when their former anti-American anti-imperialist perorations coined on the Chinese model of Mao’s cultural revolution became totally outdated and preposterous once Kissinger had forged an alliance with communist China, that wasn’t ready anymore to support Maoist zealots and puppets in the Western world. Indeed, the United States would better than now contain Russia, China and India in case of a renewed alliance with Teheran. And using the quite wide influence sphere of the “Iranian civilization” (as the former Shah used to say), they could extend more easily their preponderance in Central Asia, in the Fertile Crescent, in Lebanon (with the Shiite minority armed by the Hizbollah) and in the Gulf where Shiite minorities are important. But Iran would then become a too powerful ally, exactly like China, the new ally of 1972, does. And before Iran would become a new China and develop naval capacities in the Gulf and in the Oman Sea, i. e. in one of the main areas of the Indian Ocean, like China wants to control entirely the Southern Chinese Sea in the Pacific, Europe would have to unite with Russia and India to contain a pro-American Iran! Stephen Kinzer, former “New York Times” bureau chief in Turkey, celebrated analyst of Iran’s turmoil in 1953 (the Mossadegh case) and International relations teacher at Boston University, pleads in his very recent book “Reset Middle East” for a general alliance on the Near East, Middle East and South Asian rimlands between Turks, Iranians and Americans (which would include also Pakistan and so re-establish the containing bolt that the Bagdad Treaty formerly was). When you are interested in geopolitics you should have fine observing skills and foresee all possible shifts in alliances that could occur in a very near future. It is also obvious that if Washington continues to treat Teheran as a “rogue state”, the Iranians will be compelled to play the game with Russia that remains nevertheless historically a foe of the Persians. Each Russian-Persian tandem would split in its very middle the rimland’s room that was organised by the Bagdad Treaty of the Fifties and give the Russians indirectly a broad “window” on the Indian Ocean, which is a state of things totally contrary to the principles settled by Homer Lea in 1912 and since then cardinal to all the Anglo-Saxon sea powers.

The relationship with the United States is a quite complex one. Two main ideas must be kept in mind if you want to understand our position:

1) Like the British historian Christopher Hill brilliantly demonstrated in his books “The World Turned Upside Down – Radical Ideas During the English Revolution” and “Society and Puritanism in Pre-Revolutionary England”, the core ideas that lead to the foundation of the British Thirteen Colonies in the Northern part of the New World was “dissidence” in front of all the European political systems inherited from the past. Later Clifford Longley in “Chosen People – The Big idea that Shapes England and America” produced an very accurate historical analysis of this Biblical idea of a Chosen People that leads Britons and Americans to perceive themselves not as a particular people of the European Caucasian family but as a “lost tribe of Israel”. Longley explains us that state of affairs by writing that Britons and Americans don’t have an identity, as other European people have, but thinks that they have a particular destiny, i. e. to build an aloof “New Jerusalem” and not a concrete defensive Empire of the European people, that would be born out of the genuine historical traditions of the subcontinent and simultaneously the legitimate, syncretic, Continental and Insular (Britain, Ireland, Sicily, Crete, Cyprus, etc.) heir of the Roman Empire and of the medieval Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation. The very idea of incarnating a “New Jerusalem” leads to despise the “non chosen”, even if they are akin people having importantly contributed to the ethno-genesis of the English or American nation (Dutch, Flemings, Northern Germans as Hanovrian or Low Saxons, Danes and Norwegians). Kevin Phillips, former Republican strategist in the United States and political commentator in leading American papers, in his fascinating book “American Theocracy – The Peril and Politics of Radical Religion, Oil and Borrowed Money in the 21st Century”, criticizes the new political theology induced by the several Bush’s Administrations between 2000 and 2008, that have bereft the Republicans from the last remnants of traditional diplomacy, leading to what he calls an “Erring Republican Majority”. Indeed each chosen people’s theology introduced in the events of the international chessboard destroys all the traditional ways of practising diplomacy, as surely as French Sans-Culottes’ Republicanism or Bolshevism did or Islam Fundamentalism does. Europe, as a continent that has a long memory, cannot admit a scheme that rejects vehemently all the heritages of the past to replace them by mere artificial myths, that were moreover imported from the Near East in Roman times and have received a still faker interpretation in the decades just after Reformation.

2) The second main fact of history to keep in mind in order to understand the complex Euro-American relationship is the effect the Monroe Doctrine had on the international chessboard from the second quarter of the 19th Century onwards. In principle the Monroe Doctrine aimed at preventing European interventions in the New World or the Western Hemisphere as the Spanish “creole” countries had rebelled against Madrid and gained their independence and as the British had burnt Washington in 1812, after having invaded the States from Canada, and the Russians were still formally in California and Alaska. Monroe feared a general intervention of the “Pentarchy” powers everywhere in the new World that would have prevented the former Thirteen Colonies to develop and would synchronously have choked any attempt to rise as a Northern American continental and bi-oceanic power. Indeed the young Northern American Republic faced at that time a huge Eurasian block that seemed definitively indomitable, with British room projections in India and Southern Africa. The American historian Dexter Perkins in his book “Hands off: A History of the Monroe Doctrine” (1955) explains us that President Monroe got the audacity to challenge the European/Eurasian block at a time when the United States couldn’t actually assert any well-grounded power on the international chessboard. Monroe’s bold affirmation created US power in the world, simply because a pure will, expressed in plain words, can really anticipate actual power, be the very first step towards it. It is not a simple matter of chance that Carl Schmitt stressed the uttermost importance of the Monroe Doctrine in the genesis of the geopolitical shape of present-day world. Jordis von Lohausen says in his book “Mut zur Macht” that if Monroe wanted to preserve the New World from any European intervention, he wanted simultaneously to keep this New World for the USA themselves as sole hegemonic power. But if the New World is united under the leadership of Washington, it must control the other banks of the Oceans in a way or another to prevent any concentration of power able to disturb US hegemony or to regain authority in Latin America, be it directly political (like during the attempt of Maximilian of Hapsburg to create a European-dominated Empire in Mexico in 1866-67 with the support of France, Belgium, Spain and Austria) or indirectly by trade and economical means (as Germany did just before the two World Wars). So in the end effect, the Monroe Doctrine implies that the United States have to control the shores of Western Europe and of Morocco and the ones of Japan, China, Indochina and the Philippines in order to survive a the main superpower in the world.

The critical attitude we always have developed in front of the US American fact derives from these two core ideas. We cannot accept a Biblical ideology refusing to take into account our real roots and reducing all the institutions generated by our history to worthless rubbish. We can neither accept an affirmation of power that denies us the right to be ourselves a power on political, military and cultural levels. Would America get rid of the former British dissident ideology and adopt the principles of continental autarky, as Lawrence Dennis taught to do, there wouldn’t be any problem anymore. It would even be of great benefit for the US American population itself.

In your many articles you have exhibited an impressive knowledge of European thinkers from Hamsun and Evola to Spengler and Schmitt. Do you consider some of them more important, and a good starting-point for the pro-European individual?