Café Het Goudblommeke (55 rue des Alexiens 1000 Brussel) maart 1953. Van links naar rechts: Marcel Mariën, Camille Goemans, Gérard Van Bruaene, Irène Hamoir, Georgette Magritte, E.L.T. Mesens, Louis Scutenaire, René Magritte en Paul Colinet.

Tout comme l'histoire de la peinture et de la sculpture symbolistes belges doit encore être écrite, cela en dépit de nombreux et parfois remarquables travaux d'approche tels des catalogues d'expositions et de savantes monographies de détail ou d'ensemble, l'histoire de l'art surréaliste de Belgique reste encore à écrire. Certes, il existe déjà pas mal de publications à ce sujet, ne serait-ce que les innombrables livres parus à la louange de la peinture de René Magritte ou de Paul Delvaux. Il y a eu de même des esquisses de travaux d'ensemble qui pèchent, hélas, par manque d'objectivité ou d'information. Le travail le plus complet jusqu'ici est le beau livre de Madame José Vovelle, actuellement professeur en Sorbonne. Ce livre, édité en 1972 aux Editions André De Rache à Bruxelles, n'est toutefois qu'une thèse de doctorat de troisième cycle soutenue en 1968 à Paris.

Comme le dit un modeste "avertissement" en tête de ce très remarquable travail, "Depuis des documents inédits ont été divulgués et des études particulières ont précisé tel ou tel point de la matière envisagée". Et en effet, de nombreuses perspectives nouvelles se sont ouvertes, tandis que des faits tout aussi nouveaux ont tenté de brouiller celles-ci depuis la rédaction de l'ouvrage de Madame Vovelle.

Puisse le catalogue pour la présente exposition des oeuvres qui ont fait l'objet du legs Hamoir-Scutenaire rectifier quelque peu ces perspectives, et d'abord en précisant que ce que l'on présente généralement comme le surréalisme en Belgique n'est le plus souvent que le surréalisme de la "Société du mystère" (selon l'expression de Patrick Waldberg) de l'entourage de Magritte, et encore ... Bien souvent on oublie d'y ajouter le surréalisme du "Groupe surréaliste du Hainaut", en ignorant à peu près complètement l'éphémère effloraison du surréalisme liégeois avec Auguste Mambour, qui fut un remarquable surréaliste durant environ trois ans, et le couple Delbrouck-Defize qui exposa même un jour à Paris sous l'égide d'André Breton.

Deux femmes surréalistes wallonnes, qui relèvent plutôt du groupe surréaliste parisien, sont la Namuroise Marianne Van Hirtum et la Liégeoise Alika Lindberg, fille du poète Hubert Dubois, l'inspirateur du surréalisme de Mambour. Cette dernière figure toutefois dans les annales du surréalisme parisien sous le nom de Monique Watteau. Toutes deux semblent des inconnues pour les historiens du surréalisme belge, tout comme la Gantoise Suzanne Van Damme, l'épouse du surréaliste italien Bruno Capacci et l'amie des surréalistes bruxellois Paul Colinet et Marcel Lecomte. ·

C'est par ailleurs un lieu commun d'affirmer que si l'expressionnisme belge est flamand, le surréalisme belge serait wallon. Rien n'est moins vrai, car le maître à penser du surréalisme bruxellois, Paul Nougé, bien que d'origine française, avait une mère flamande, tout comme l'historiographe officiel du surréalisme belge, Marcel Mariën est anversois. Il en est de même pour son homonyme (également un oublié quoique surréaliste depuis 1926-1927), le collagiste Georges Mariën, chef de file de plusieurs collagisles surréalistes anversois.

N'oublions pas que Camille Goemans est le fils du Secrétaire perpétuel de l'Académie royale de Langue et de Littérature flamandes de Belgique et que E.L.T. Mesens se proclamait volontiers, ne serait-ce que par bravade ou provocation, "le flamingant de Londres". Fait est qu'en sa jeunesse présurréaliste celui-ci avait été un intime des poètes expressionnistes flamands Wies Moens et Paul Van Ostaijen ainsi que du futur chef fasciste flamand Joris Van Severen dont une grande amie de Magritte, la Flamande, quoique francophone Rachel Baes a été la fidèle égérie au point de se faire enterrer à ses côtés au cimetière d'Abbeville en France.

On néglige également l'apport pourtant important au surréalisme belge des Flamands Fritz Van den Berghe, tout au moins en son ultime période (1927-1939), de Maxime Van de Woestijne (il est le seul à représenter le surréalisme belge dans une petite monographie allemamle consacrée à l'ar1 surréaliste) et de nous-même, auteur d'un album contenant "dix formes linéaires influencées par dix formes verbales" (1930), le seul recueil vraiment surréaliste paru en langue néerlandaise, tout au moins en Flandre.

Comme on a bien voulu conférer à un dessinateur quelque peu naïf et sans le moindre talent le statut de surréaliste à part entière pour la seule raison qu'il est le neveu de Paul Colinet, pourquoi ne nous permettrions-nous pas de joindre également aux surréalistes belges un Jules Lempereur qui inspira par certains de ses dessins le livre de Marcel Lecomte intitulé "Connaissance des degrés", paru toutefois sans les arts dessins. Même dans les milieux officiels (Administration des Beaux-Arts et Musées) le surréalisme belge est devenu ûn vrai fourre-tout. C'est ainsi, par exemple, qu'à l'exposition "Werkelijkheid en verbeelding - Belgische Surrealisten" (Réalité et imagination - Surréalistes belges), qui s'est tenue à Arnhem du 12 juillet au 6 septembre 1964, nous retrouvons parmi les exposants James Ensor, Léon Spilliaert, Victor Servranckx , Jan Burssens, Marcel Delmotte et Octave Landuyt, sans oublier plusieurs peintres qur fréquentaient la taverne bruxelloise "Le Petit Rouge", promus surréalistes par E.L.T. Mesens du fait qu'il y avait ses habitudes lors de ses séjours, après guerre, dans sa ville natale...

***

Si l'on veut vraiment écrire une histoire objective des "surréalismes de Belgique", il conviendrait d'y reconnaître trois courants dont les prodromes sont un courant dadaïste ("Oesophage", "Marie"), un courant rationaliste , très valéryen ("Correspondance") et un courant métaphysique, proche des vues sur la poésie du poète flamand Paul Van Ostaijen ("Hermès").

Des trois courants seuls les deux premiers ont requis l'attention des historiens du surréalisme belge (voir e.a. le livre de José Vovelle et le catalogue de l'exposition "René Magritte et le Surréalisme en Belgique" (Musées royaux des Beaux-Arts de Belgrque, Bruxelles 24 septembre - 5 décembre 1982). Quant au troisième courant, fort proche du surréalisme de l'André Breton du "Second manifeste du Surréalisme", 1929, il ne prit vraiment corps qu'en 1930, lorsque Camille Goemans et Marc. Eemans eurent pris congé", du surréalisme à la Nougé-Magritte et Scutenaire, en fondant les Editions "Hermès".

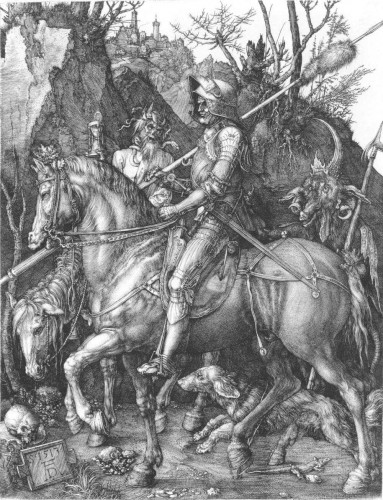

La vraie soudure entre les surréalistes bruxellois se fit à l'occasion de ce qu'il est convenu d'appeler la "bataille du Casino de Saint Josse" (novembre 1926): Les futurs membres du groupe vinrent à cette manifestation en char à bancs (une initiative de Geert van Bruaene) accompagnés d'un "chevalier" mercenaire en armure, car les acteurs du "Groupe Libre" avaient averti leurs adversaires qu'ils seraient reçus sans ménagement. Il y eut en effet non seulement chahut, mais aussi bataille avec quelques blessés légers de part et d'autre, dont Camille Goemans.

Parmi les amis des futurs surréalistes il y avait outre Van Bruaene , trors Flamands, les poètes Gaston Burssens et Paul Van Ostaijen (à cette époque un associé de van Bruaene) ainsi que l'auteur de ces lignes qui fut le seul de ceux-ci à rejoindre le groupe.

Marc. Eemans entraîna dans son sillage son amie Irène Hamoir laquelle il venait d'apprendre les rudiments du surréalisme selon les préceptes du premier "Manifeste du surréalisme" de Breton, d'où la "Lettre à Irène sur l'automatisme". Hélas, pour Eernans ! l'"automatisme" n'était pas tout à fait à l'ordre du jour de surréalistes bruxellois loin de là ! Il avait oublié que ceux-ci étaient surtout férus d'insolite et de spéculations diverses sur les apparences des choses et de leur réalité la plus banale possible tout en les rangeant dans un ordre peu habituel. Seconde bévue d'Eemans au sein du groupe, fut sa traduction d'une "Vision" d'une mystique médiévale brabançonne, Soeur Hadewych. Selon lui, le déroulement de cette vision rejoignait la quête du mervetlleux des surréalistes. Il suivait en cela une des thèses de son ami Van Ostaijen selon laquelle, tout en n'accordant que peu de crédit à l'écriture automatique à la Breton, celui-ci prônait en poésie une exploitation consciente du subconscient, en faisant une distinction nette entre la poésie subconsciemment inspirée et la poésie consciemment construite. Selon Van Ostaijen, la première de ces deux poésies procéderait d'un état extatique et, si l'on n'est pas un mystique, cette poésie pourrait procéder d'un fonds de mythes et d'archétypes selon une psychologie des profondeurs comme l'a formulée un Carl Gustav Jung.

A l'époque, Eemans et Van Ostaijen étaient encore ignorants de la psychologie jungienne, mais en bon surréaliste Eemans se croyait autorisé à se référer au freudisme et à ses vues sur l'inconscient. Toutefois, sans connaître Jung, Van Ostaijen et Eemans s'étaient déjà convertis aux vertus de tout ce qui relèverait de l'irrationnel, du métaphysique el de l'hermétique : aussi bien la mystique, orthodoxe ou non, que l'occultisme, l'alchimie, la parapsychologie, le romantisme, surtout allemand, et le symbolisme, sans oublier l'art des fous et ce que l'on appellerait plus tard l'"art brut", bref tout ce qui. s'insère dans l'imaginaire, le féerique du "hasard objectif', le fantastique et le merveilleux visionnaire.

Que nous sommes loin d'un surréalisme à la Nougé - Magritte et surtout de la gratuité du dadaïsme à la Mariën ! mais proche du surréalisme du Breton qui croit à ce fameux "point suprême d'où la vie et la mort, le réel et l'imaginaire, le passé et le futur, le communicable et l'incommunicable cessent d'être perçus contradictoirement".

Et aussi que nous sommes encore loin de ce futur surréalisme "non-dit" de la revue "Hermès", celle-ci consacrée à l'étude comparée de la poésie, de la mystique el de la philosophie.

Marc. Eemans en devint un des deux directeurs et Camille Goemans y fut l'auteur des "Notes des Editeurs" ainsi que des "Notes sur la poésie et l'expérience" rédig ées en collaboration avec l'essayiste Joseph Capuano. Henri Michaux, ami de collège de Goemans, devint le secrétaire de rédaction de la revue et André Rolland de Renéville, l'auteur de "Rimbaud le Voyant", ainsi que Bernard Groethuysen et quelques autres spécialistes en la matière y entrèrent au comité de rédaction. La revue compta parmi ses collaborateurs Marcel Lecomte qui entretint ainsi certains contacts avec le groupe Nougé, Magritte et Scutenalre. Que de sérieux peu "surréaliste" dans tout cela dira-t-on ! Aussi le ludique E.L.T. Mesens fut-il, "très fâché" en traitant ses anciens amis de "petits curés"... Plus tard tout rentra toutefois dans l'ordre surréaliste et Camille Goemans re devint à la grande joie de celui-ci un riche acheteur d'oeuvres de Magritte. Quant à Eemans, il redevint l'ami intime de Mesens et l'on sait que le couple Scutenaire-Hamoir, ainsi que le brave et gentil Colinet, cessèrent de bouder le vieux complice de leur "Bande Bonnot".

Seul le caractériel Marcel Mariën (en raison d'une jalousie d'ordre sentimental!) et ses jeunes séides d'après-guerre ne cessèrent de harceler Eemans de leur hargne, bien que Tom Gutt lui ait toul récemment adressé quelques lettres fort courtoises...

Mais arrêtons ici ces trop brèves el peul-être trop subjectives notes sur les "surréalismes de Belgique". N'empêche qu'en dépit de récentes lois en matière de révisionnisme politique, il conviendrait de pratiquer pas mal de révisionnisme surréaliste en réagissant contre certaines déviations el dérives vers la facilité pseudo- ou néo-dadaïste et la grossièreté pure et simple sous prétexte de faire de l'anti-esthétique el de l'antifascisme.

Et souvenons-nous du fameux pamphlet de Salvador Dali à l'adresse des "cocus du vieil art moderne". Quoique l'on puisse en penser, il ne s'agit pas que d'humour "paranoïa-critique"…

Marc. Eemans

Mai 1995

Uit: Eemans, M. (1995), Une approche des surréalismes de Belgique. Bruxelles: Fondation Marc. Eemans : archives de l’art idéaliste et symboliste.

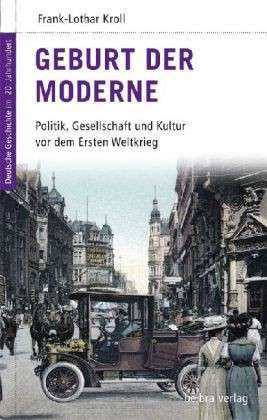

Der Nationalsozialismus ist der absolute Fixpunkt der deutschen Geschichte – wirklich alles ballt sich zu ihm hin. Alle zeitlich daran angrenzenden Epochen verschwinden in seinem Schatten.

Der Nationalsozialismus ist der absolute Fixpunkt der deutschen Geschichte – wirklich alles ballt sich zu ihm hin. Alle zeitlich daran angrenzenden Epochen verschwinden in seinem Schatten.

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

Zusammen mit

Zusammen mit

Eemans romantische en aristocratische gezindheid doen hem evolueren naar een eerder mythisch geïnspireerd nationaalsocialisme. “Eemans [zag] in het nazisme vooral een terugkeer tot de oertraditie, de wedergeboorte van een sacrale en magische wereld die ten onder was gegaan aan de technische, democratische maatschappij.” (1) Het in 1944 verschenen L'épreuve du feu: à la recherche d'une éthique

Eemans romantische en aristocratische gezindheid doen hem evolueren naar een eerder mythisch geïnspireerd nationaalsocialisme. “Eemans [zag] in het nazisme vooral een terugkeer tot de oertraditie, de wedergeboorte van een sacrale en magische wereld die ten onder was gegaan aan de technische, democratische maatschappij.” (1) Het in 1944 verschenen L'épreuve du feu: à la recherche d'une éthique

Le témoignage de George Rémi JUNIOR, le neveu d'Hergé, fils de son frère cadet, un militaire haut en couleur, cavalier insigne, auteur d'un manuel du parfait cavalier, est poignant, non seulement parce qu'il nous révèle un Hergé "privé", différent de celui vendu par "Moulinsart", mais aussi parce qu'il révèle bien des aspects d'une Belgique totalement révolue: sévérité de l'enseignement, difficulté pour un jeune original de se faire valoir dans son milieu parental, sauf s'il persévère dans sa volonté d'originalité (comme ce fut le cas...).

Le témoignage de George Rémi JUNIOR, le neveu d'Hergé, fils de son frère cadet, un militaire haut en couleur, cavalier insigne, auteur d'un manuel du parfait cavalier, est poignant, non seulement parce qu'il nous révèle un Hergé "privé", différent de celui vendu par "Moulinsart", mais aussi parce qu'il révèle bien des aspects d'une Belgique totalement révolue: sévérité de l'enseignement, difficulté pour un jeune original de se faire valoir dans son milieu parental, sauf s'il persévère dans sa volonté d'originalité (comme ce fut le cas...).

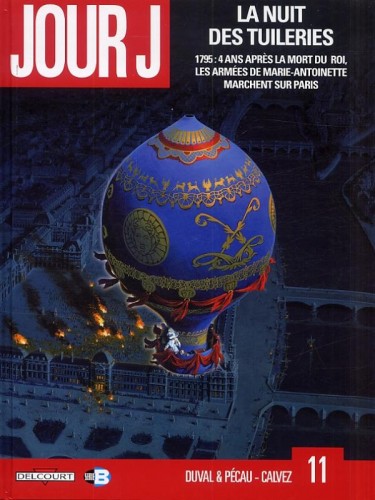

L’énigmatique Jacques Bergier est l’un des héros principaux d’une série, au succès indéniable, qui en est à son deuxième volume : Wunderwaffen. Si l’histoire concerne toujours le second conflit planétaire, les événements sont uchroniques. Le 6 juin 1944, les mauvaises conditions météo et la réaction plus rapide des Allemands empêchent le débarquement allié en Normandie. La guerre se prolonge donc au-delà de 1945 même si les États-Unis ont mis un terme à la guerre dans le Pacifique au moyen des bombes atomiques. L’Allemagne résiste grâce à la généralisation de ses armes secrètes, les « armes-miracles » : V1, V2, V3, avions monoplans à réaction… Victime d’un nouvel attentat, le 8 mai 1945, qui l’a en partie défiguré et privé d’un bras, Hitler se verra bientôt doté d’un membre supérieur artificiel.

L’énigmatique Jacques Bergier est l’un des héros principaux d’une série, au succès indéniable, qui en est à son deuxième volume : Wunderwaffen. Si l’histoire concerne toujours le second conflit planétaire, les événements sont uchroniques. Le 6 juin 1944, les mauvaises conditions météo et la réaction plus rapide des Allemands empêchent le débarquement allié en Normandie. La guerre se prolonge donc au-delà de 1945 même si les États-Unis ont mis un terme à la guerre dans le Pacifique au moyen des bombes atomiques. L’Allemagne résiste grâce à la généralisation de ses armes secrètes, les « armes-miracles » : V1, V2, V3, avions monoplans à réaction… Victime d’un nouvel attentat, le 8 mai 1945, qui l’a en partie défiguré et privé d’un bras, Hitler se verra bientôt doté d’un membre supérieur artificiel. Avec La nuit des Tuileries, la royauté française est au cœur du n° 11, récemment sorti. L’uchronie commence dans la nuit du 10 juin 1791. Des sans-culottes exaltés se dirigent sur les Tuileries, mais la famille royale parvient à s’en échapper en montgolfière. Or, au moment de l’ascension, une balle atteint le ventre de Louis XVI qui meurt en chemin. Le Dauphin devient le nouveau roi et sa mère, la reine Marie-Antoinette, la régente. Celle-ci anime l’« Armée des Princes » et la France sombre dans une terrible guerre civile. En 1795, l’armée royale, dirigée par un génial général d’origine corse, ancien mercenaire au service du Grand Turc, est aux portes de Paris, bastion sans-culotte chauffé à blanc par Robespierre. Mais Danton négocie en secret avec l’évêque d’Autun, Talleyrand, afin de rétablir la royauté dans un cadre constitutionnel.

Avec La nuit des Tuileries, la royauté française est au cœur du n° 11, récemment sorti. L’uchronie commence dans la nuit du 10 juin 1791. Des sans-culottes exaltés se dirigent sur les Tuileries, mais la famille royale parvient à s’en échapper en montgolfière. Or, au moment de l’ascension, une balle atteint le ventre de Louis XVI qui meurt en chemin. Le Dauphin devient le nouveau roi et sa mère, la reine Marie-Antoinette, la régente. Celle-ci anime l’« Armée des Princes » et la France sombre dans une terrible guerre civile. En 1795, l’armée royale, dirigée par un génial général d’origine corse, ancien mercenaire au service du Grand Turc, est aux portes de Paris, bastion sans-culotte chauffé à blanc par Robespierre. Mais Danton négocie en secret avec l’évêque d’Autun, Talleyrand, afin de rétablir la royauté dans un cadre constitutionnel.