France gave the world the French Revolution in 1789. It was an epochal event, albeit a symptom of a line of cultural decadence that gave birth to both liberalism and Communism, and which remains a pall over the entire West and wherever the West reaches. It is ironic that those who were condemned as “collaborators” in France during and after the Second World War were for years prior to the war the most vociferous in their lamentations regarding the decadence of the French Republic. None lamented more the rapidity with which France had fallen to the Germans; it was regarded as a national dishonor and the result of France’s moral, spiritual, and cultural rot.

Among those who had brought ruin to France, Freemasonry had a prominent role.[1] [2] Rationalism, secularism, scientism, and materialism were used as methods of subversion by occult forces in a struggle between Counter-Tradition and the few remaining vestiges of the Traditional.[2] [3]

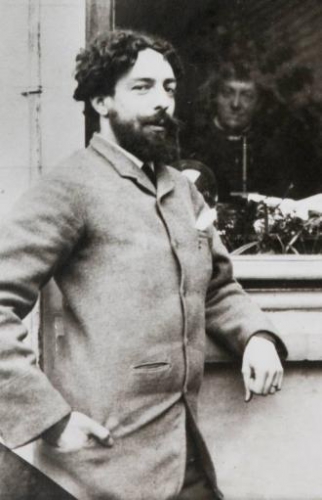

In France during the decades leading up to another epochal catastrophe, the First World War, this occult war between Tradition and Counter-Tradition intensified. Since Counter-Tradition makes use of Counterfeit-Tradition, it is often difficult to discern what role sundry secret societies and individuals play in this conflict. For example, what side is Nicholas Roerich on, and what side the apparently “sinister” Aleister Crowley?[3] [4] The answer is not as obvious as one might suppose. At the time, there was an occult revival; a product of a civilization in crisis, and the existential angst of those who could not endure the tedium of scientism, secularism, rationalism, and atheism, which since the time of the French Revolution had been heralded as new religions. In the liberal ideal of the “happiness of the greatest number,” few are happy with the tedium of equality and democracy. While in Britain, William Butler Yeats, Crowley, and sundry other eccentric and intellectual figures were responding to the age of Darwin, industrialism, and science through the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn, a remarkable individual emerged from the occult revival in France: Joséphin Péladan.

Péladan was the head of the Ordre Kabbalistique Rose-Croix (Kabbalistic Order of the Rosicrucian), succeeding his brother Adrien. While the original Rosicrucians, who had appeared mysteriously in Europe during the early seventeenth century and issued anonymous manifestos, seem to have been among the precursors of the Masonry and Illuminism that fermented the French Revolution against the Church and the Monarch, Péladan, on the contrary, was a Catholic traditionalist who repudiated the ideals of the French Revolution and the “Liberty, Equality, Fraternity” of the Grand Orient of Masonry, stating in 1883, “I believe in the Ideal, Tradition and Hierarchy.”[4] [5]

Péladan was the head of the Ordre Kabbalistique Rose-Croix (Kabbalistic Order of the Rosicrucian), succeeding his brother Adrien. While the original Rosicrucians, who had appeared mysteriously in Europe during the early seventeenth century and issued anonymous manifestos, seem to have been among the precursors of the Masonry and Illuminism that fermented the French Revolution against the Church and the Monarch, Péladan, on the contrary, was a Catholic traditionalist who repudiated the ideals of the French Revolution and the “Liberty, Equality, Fraternity” of the Grand Orient of Masonry, stating in 1883, “I believe in the Ideal, Tradition and Hierarchy.”[4] [5]

Interestingly, when a schism occurred within the Order, one of the reasons was that among what was regarded as Péladan’s eccentric behavior was his having issued a public condemnation against a female member of the Rothschild banking dynasty. Among the leaders of the schism were the morphine-addicted Marquis Stanislas de Guaita, an individual who was to display decidedly Satanic convictions,[5] [6] and the conspiratorial figure Papus, who brought Martinist Freemasonry to Russia with decidedly subversive results, culminating in Bolshevism. Under their control, the Ordre Kabbalistique worked the degrees of this Martinist Masonry, which had a linage reaching back to the infamous Illuminati via the Kabbalist, Martinez de Pasqually.

At the time of the schism, Péladan and de Guaita had been involved in “magical warfare” against another sinister character, the apostate priest, the Abbé Boullan, who was the head of a depraved Satanic cult (this description is without sensationalism). However, de Guaita was himself interested in the Left-Hand Path magic of Boullan.

Leaving the Ordre Kabbalistique, Péladan founded the Ordre de la Rose-Croix catholique et esthétique du Temple et du Graal (Order of the Temple and the Graal and of the Catholic Order of the Rose-Croix), the title explicitly explaining the character of this Order.

On March 24, 1893, the Supreme Council of the Ordre Kabbalistique issued a public statement signed by Stanislas de Guaita and Papus, condemning Péladan as a “usurper, schismatic, and apostate,” and denouncing his Ordre de la Rose-Croix catholique. The battle lines between Tradition and Counter-Tradition had been drawn publicly.

Péladan saw the purpose of his Rosicrucian Order as being to encourage the resurgence of the arts that were in decay. A novelist himself, he was a central figure in the Symbolist art movement, and many artists, musicians, and poets of note were initiated into his Order. Péladan considered the artist to be the embodiment of king, priest, and magus; the nexus with the divine. He explained:

Art is man’s effort to realize the Ideal, to form and represent the supreme idea, the Idea par excellence, the abstract idea, and great artists are religious, because to materialize the idea of God, the idea of an angel, the idea of the Virgin Mother, requires an incomparable psychic effort and procedure. Making the invisible visible: that is the true purpose of art and its only reason for existence.[6] [7]

Péladan saw art as the religion that persists above all atheistic efforts to repress the spirit. He called for spiritual battle against the profane:

Artist, you are a priest: Art is the great mystery and, if your effort results in a masterpiece, a ray of divinity will descend as on an altar. Artist, you are a king: Art is the true empire, if your hand draws a perfect line, the cherubim themselves will descend to revel in their reflection . . . They may one day close the Church, but [what about] the Museum? If Notre-Dame is profaned, the Louvre will officiate . . . Humanity, oh citizens, will always go to mass, when the priest will be Bach, Beethoven, Palestrina: one cannot make the sublime organ into an atheist! Brothers in all the arts, I am sounding a battle cry: let us form a holy militia for the salvation of idealism . . . we will build the Temple of Beauty . . . for the artist is a priest, a king, a mage, for art is a mystery, the only true empire, the great miracle.[7] [8]

The Salon de la Rose et Croix was established in 1892 to exhibit Symbolist art to the public. Art was magic, not rituals and incantations. It was intended as the harbinger of a spiritual revolution that would overthrow the materialistic and the decadent, and as the antithesis to the art of the other salons. The first exhibition drew fifty thousand visitors. Clearly, the French yearned for something transcending the crassness of Grand Orient liberalism and secularism, which had rotted France for a century; the “disenchantment of the world,” as he called it. Richard Wagner’s music had a special place, Péladan regarding Wagner as “a therapeutic detoxifier of France’s materialism.” Erik Satie was the Order’s official composer, and Debussy was a close colleague. Péladan defined what was required in his appeal for exhibitors: “The order favors the Catholic Ideal and mysticism. After that, Legends, Myths, Allegory, Dreams, the paraphrasing of great poets, and finally, all lyricism.”

The Salon de la Rose et Croix was established in 1892 to exhibit Symbolist art to the public. Art was magic, not rituals and incantations. It was intended as the harbinger of a spiritual revolution that would overthrow the materialistic and the decadent, and as the antithesis to the art of the other salons. The first exhibition drew fifty thousand visitors. Clearly, the French yearned for something transcending the crassness of Grand Orient liberalism and secularism, which had rotted France for a century; the “disenchantment of the world,” as he called it. Richard Wagner’s music had a special place, Péladan regarding Wagner as “a therapeutic detoxifier of France’s materialism.” Erik Satie was the Order’s official composer, and Debussy was a close colleague. Péladan defined what was required in his appeal for exhibitors: “The order favors the Catholic Ideal and mysticism. After that, Legends, Myths, Allegory, Dreams, the paraphrasing of great poets, and finally, all lyricism.”

Péladan’s fight for the recovery of Tradition from the corruption of those Black Adepts (to use Crowley’s term) who had engineered the French Revolution – which in a proto-Bolshevik reign of terror destroyed churches, killed priests, and performed a virtual Black Mass on the altar of Notre Dame – was echoed by another famous French occultist, Éliphas Levi, also a Catholic and who was perhaps an initiate into the Rose Cross’ eighteenth degree,[8] [9] where one at last learns the true subversive character of Masonry:

Masonry has not merely been profaned but has served as the veil and pretext of anarchic conspiracies . . . The anarchists have resumed the rule, square and mallet, writing upon them the words Liberty, Equality, Fraternity – Liberty, that is to say, for all the lusts, Equality in degradation and Fraternity in the work of destruction. Such are the men whom the Church has condemned justly and will condemn forever.[9] [10]

August Strindberg, the Swedish novelist, playwright, poet, and painter who turned to the occult during an existential crisis, later returned to Catholicism as a Traditional anchor in a decaying world. Upon visiting Paris, he also noted the decadence there in an autobiographical account in which he indicated his intention of returning to the Church. On reading Péladan, he remarked:

On May 1st I read for the first time in my life Sar Péladan’s Comment on devient un Mage.

Sar Péladan, hitherto unknown to me, overcomes me like a storm, a revelation of the higher man, Nietzsche’s Superman, and with him Catholicism makes its solemn and victorious entry into my life.

Has “He who should come” come already in the person of Sar Péladan? The Poet-Thinker-Prophet – is it he, or do we wait for another?[10] [11]

Péladan’s salon exhibitions were an enormous success. However, by the sixth and final exhibition in 1896, he had become worn out with the very public so-called “War of the Two Roses” between his “Catholic Rose-Cross,” as he called it,[11] [12] and the Martinist-Masonry of the Ordre Kabbalistique. For someone such as Péladan, such psychic conflicts, whatever we may think of their mundane reality, and likely augmented by Papus’ Masonic friends and Rothschild influences in the press, would have taken a heavy toll.

Notes

[1] [13] K. R. Bolton, The Occult and Subversive Movements (London: Black House Press, 2017), pp. 175-189.

[2] [14] Ibid., pp. 9-13.

[3] [15] Ibid., p. 12.

[4] [16] Joséphin Péladan, “L’esthetique au salon de 1883,” L’Artiste, Vol. 1, May 1883, cited in Richard Cavendish (ed.), Encyclopaedia of the Unexplained (New York: Arkana, 1974), p. 216.

[5] [17] Ibid., p. 217.

[6] [18] Péladan, “L’esthetique au salon de 1883.”

[7] [19] Péladan, Catalogue du Salon de la Rose + Croix (Paris: Galerie Durand-Ruel, 1892), pp. 7-11, cited by Sasha Chaitow, “Making the Invisible Visible: Péladan’s Vision of Ensouled Art [20],” August 6, 2015.

[8] [21] This is indicated in a footnote to his History of Magic, where Levi states, “Having attained by our efforts to a grade of knowledge which imposes silence, we regard ourselves as pledged by our convictions even more than by an oath. . . . and we shall in no wise fail to deserve the princely crown of the Rosy Cross . . .” (London: Rider, 1982, p. 286).

[9] [22] Ibid., p. 310.

[10] [23] August Strindberg, The Inferno (New York: Knickerbocker Press, 1913), concluding passages.

[11] [24] Péladan, letter to Papus, February 17, 1891 in L’Initiation (May 8, 1891).

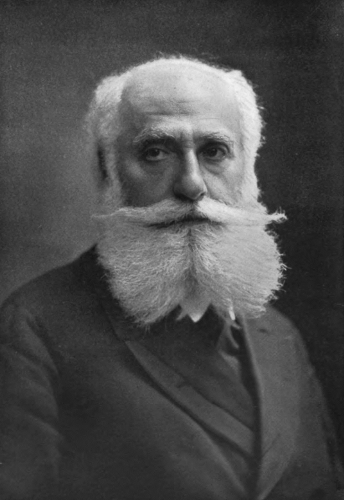

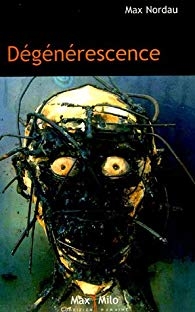

En effet, ajoute Nordau :

En effet, ajoute Nordau :

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

On a peu vu ces rebellocrates – une espèce qui prolifère de nos jours (ça ne risque rien et ça peut rapporter gros) – en faire autant devant une mosquée ou une synagogue.

On a peu vu ces rebellocrates – une espèce qui prolifère de nos jours (ça ne risque rien et ça peut rapporter gros) – en faire autant devant une mosquée ou une synagogue.

Les imposteurs culturels promus par la République attaquent directement cette clé de voûte fondamentale de la culture autochtone. Ils posent une nouvelle culture, culture artificielle et féministe valable pour tous, dans laquelle les rôles sociaux masculins et féminins sont abolis, les pères sont déclassés, les hommes sont stigmatisés, les femmes sont versées dans un monde du travail oppressif leur interdisant de faire des enfants (mieux vaut pour elles « faire une carrière »)... Conséquence logique des nouvelles normes sociales, la démographie européenne périclite, nos libertés se restreignent et l’insécurité, pas seulement culturelle, grandit.

Les imposteurs culturels promus par la République attaquent directement cette clé de voûte fondamentale de la culture autochtone. Ils posent une nouvelle culture, culture artificielle et féministe valable pour tous, dans laquelle les rôles sociaux masculins et féminins sont abolis, les pères sont déclassés, les hommes sont stigmatisés, les femmes sont versées dans un monde du travail oppressif leur interdisant de faire des enfants (mieux vaut pour elles « faire une carrière »)... Conséquence logique des nouvelles normes sociales, la démographie européenne périclite, nos libertés se restreignent et l’insécurité, pas seulement culturelle, grandit.

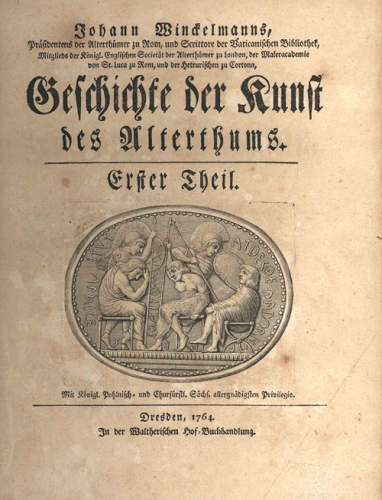

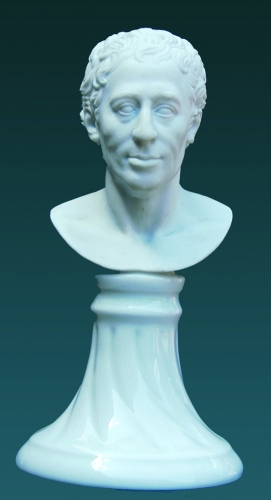

Das war insofern revolutionär, da noch im Barock die Gelehrten und Dichter am Latein festhielten und die römische Antike als Vorbild sahen. Winckelmann kam zugute, dass er, aus einfachsten Verhältnissen kommend, nicht „verbildet“ war, als er die Kunstschätze am barocken Dresdener Hof betrachtete. Statt in schwärmerische Verzückung zu geraten, richtete er einen idealisierenden Blick auf die ihm rätselhaften mythologischen Heldenfiguren, von deren nackten, muskulösen Körpern er sich wohl auch erotisch angezogen fühlte.

Das war insofern revolutionär, da noch im Barock die Gelehrten und Dichter am Latein festhielten und die römische Antike als Vorbild sahen. Winckelmann kam zugute, dass er, aus einfachsten Verhältnissen kommend, nicht „verbildet“ war, als er die Kunstschätze am barocken Dresdener Hof betrachtete. Statt in schwärmerische Verzückung zu geraten, richtete er einen idealisierenden Blick auf die ihm rätselhaften mythologischen Heldenfiguren, von deren nackten, muskulösen Körpern er sich wohl auch erotisch angezogen fühlte.

Evola, afferma Lami: “imposta…il problema filosofico in chiave individuale, o meglio, ‘esistenziale’, e risolve il metodo filosofico nella filosofia, e quest’ultima in una sorta di fenomenologia dell’individuo” . Da tale asserzione si evincono la potenza e l’originalità, nel panorama filosofico d’allora, non solo del momento speculativo evoliano, ma del suo percorso esistenziale. Infatti, l’attraversamento che egli compie dell’attualismo gentiliano, ritenuto vertice insuperato del pensiero europeo, prende le mosse, e qui Lami coglie pienamente nel segno, da Michelstaedter, dalla sua Persuasione. Questa, nell’esegesi lamiana, si configura quale: “…piacevolissima sensazione, quel piacere morale che si persegue nell’atto della liberazione, dell’auto-redenzione dal macchinamento sociale” .

Evola, afferma Lami: “imposta…il problema filosofico in chiave individuale, o meglio, ‘esistenziale’, e risolve il metodo filosofico nella filosofia, e quest’ultima in una sorta di fenomenologia dell’individuo” . Da tale asserzione si evincono la potenza e l’originalità, nel panorama filosofico d’allora, non solo del momento speculativo evoliano, ma del suo percorso esistenziale. Infatti, l’attraversamento che egli compie dell’attualismo gentiliano, ritenuto vertice insuperato del pensiero europeo, prende le mosse, e qui Lami coglie pienamente nel segno, da Michelstaedter, dalla sua Persuasione. Questa, nell’esegesi lamiana, si configura quale: “…piacevolissima sensazione, quel piacere morale che si persegue nell’atto della liberazione, dell’auto-redenzione dal macchinamento sociale” .

Anarchico, satirico e assolutamente incompreso, almeno fino al 1929 quando Re Alberto I scelse di nominarlo barone; da quel momento James Ensor, che aveva sempre fomentato critiche asprissime nei confronti della borghesia attraverso i suoi dipinti, decise di ritirare tutte le copie de “L’alimentazione dottrinaria”(1889), un’acquaforte su carta giapponese che rappresenta tutta la malsana pidocchieria dei potenti (il re e i suoi ministri) nell’atto di defecare sui sudditi (la massa) che nel frattempo accolgono l’offesa spalancando le fauci, pronte ad ospitare gli escrementi. Un ritratto ruvidissimo della società belga di fine Ottocento che vedeva sul trono Re Leopoldo II. Ma Ensor – che da socialista umanitario passò a coltivare posizioni di totale anarchismo – aveva ben compreso che gli uomini dovevano venir tutti malmenati a colpi di pennello, eccetto rari casi. Tra questi i possibili superstiti potevano essere gli artisti, ma per raggiungere un siffatto ambiziosissimo traguardo non bastava soltanto impugnare la tavolozza e il pennello, bensì “… essere ribelli alle comunioni! Per essere artisti bisogna vivere nascosti…”; ed è sicuro che Ensor non rinunciò a vivere in solitudine compiendo una crivellatura di tutte le sue frequentazioni, tanto che quando un giornalista francese volle visitarlo nella sua dimora con degli amici parigini, dovette subire nientemeno che un rifiuto da parte del servitore Auguste, fedelissimo al padrone, il quale comunicò ai visitatori l’impossibilità di incontrare il maestro, dicendo loro: “Impossibile, sta facendo i suoi bisogni”. Ensor non era certo uno studente modello, anzi, seguiva solamente la sua indole di pictor, non compresa dall’ambiente casalingo in cui viveva – influenzato da una preponderante presenza femminile – se non dal padre, un ricco borghese di origini inglesi considerato da tutti i cittadini di Ostenda (la città natale dell’artista) come un buonannulla: quest’ultimo finirà infatti corrodendo sé medesimo nell’alcol e favorendo cospicuamente il generale schernimento nei suoi confronti. La madre, invece, gestiva un negozio dove Ensor era solito recarsi fin da giovane per fornire aiuto o anche più semplicemente per acuire la sua sensibilità artistica attraverso l’osservazione degli oggetti in vendita. Malgrado questi vaghi accenni d’affetto, la situazione familiare del pittore restò sempre molto arida e lontana dal concedergli la forza d’animo di prendere le distanze dalla sua parentela. Da ciò emerge anche il rapporto ambivalente di Ensor con le donne: “Ah, la donna e la sua maschera di carne, di carne viva diventata per davvero maschera di cartone…”. Sempre la madre, per altro, non voleva che il figlio dipingesse dei nudi femminili attingendo direttamente da modelli in carne e ossa. Nell’evoluzione pittorica di questo autore si assiste ad una fase iniziale composta da vedute paesaggistiche ispirate all’impressionismo e ritratti realistici, come quello in cui mischia narcisisticamente la sua identità con quella dell’artista fiammingo del periodo barocco Pieter Paul Rubens: otterrà in tal caso un dipinto austero ed enigmatico, ma anche faceto per via del cappello di paglia corredato di fiorellini con differenti cromie (“Ensor con il cappello fiorito” 1883-1888). Giunse poco più tardi il periodo maggiormente produttivo per Ensor, quello collocabile tra il 1885 e il 1895, anni in cui si avvicinò brevemente al gruppo avanguardistico de “I Venti”, che proponeva un’educazione culturale spaziante dalle arti visive, alla musica, alla poesia. Proprio in questo decennio l’utilizzo delle maschere rappresentò la vera svolta dell’arte ensoriana, seppur non di quelle africane che appassioneranno diversi altri artisti nel corso di tutto il Novecento. Di queste ultime ebbe a dire: “Condanno senza remissione la maschera cresciuta male degli inferni d’Africa… Al diavolo i tratti e le attrazioni facili, e il vecchio gioco del feticcio negroide o gorillato”. Venerò piuttosto le maschere capaci di evocare atmosfere carnevalesche come quelle respirabili tutt’oggi al Carnevale di Binche, in Belgio, dove una moltitudine di Gilles compiono la loro sfilata tra le profusioni dionisiache della folla. E infatti lo stesso Ensor scrisse: “Bisogna essere degni dell’Arte di casa nostra, arte sana senza paura né rimproveri. Abbasso i leopardi di contrabbando! Forza ai nostri gilles e ai nostri leoni!”

Anarchico, satirico e assolutamente incompreso, almeno fino al 1929 quando Re Alberto I scelse di nominarlo barone; da quel momento James Ensor, che aveva sempre fomentato critiche asprissime nei confronti della borghesia attraverso i suoi dipinti, decise di ritirare tutte le copie de “L’alimentazione dottrinaria”(1889), un’acquaforte su carta giapponese che rappresenta tutta la malsana pidocchieria dei potenti (il re e i suoi ministri) nell’atto di defecare sui sudditi (la massa) che nel frattempo accolgono l’offesa spalancando le fauci, pronte ad ospitare gli escrementi. Un ritratto ruvidissimo della società belga di fine Ottocento che vedeva sul trono Re Leopoldo II. Ma Ensor – che da socialista umanitario passò a coltivare posizioni di totale anarchismo – aveva ben compreso che gli uomini dovevano venir tutti malmenati a colpi di pennello, eccetto rari casi. Tra questi i possibili superstiti potevano essere gli artisti, ma per raggiungere un siffatto ambiziosissimo traguardo non bastava soltanto impugnare la tavolozza e il pennello, bensì “… essere ribelli alle comunioni! Per essere artisti bisogna vivere nascosti…”; ed è sicuro che Ensor non rinunciò a vivere in solitudine compiendo una crivellatura di tutte le sue frequentazioni, tanto che quando un giornalista francese volle visitarlo nella sua dimora con degli amici parigini, dovette subire nientemeno che un rifiuto da parte del servitore Auguste, fedelissimo al padrone, il quale comunicò ai visitatori l’impossibilità di incontrare il maestro, dicendo loro: “Impossibile, sta facendo i suoi bisogni”. Ensor non era certo uno studente modello, anzi, seguiva solamente la sua indole di pictor, non compresa dall’ambiente casalingo in cui viveva – influenzato da una preponderante presenza femminile – se non dal padre, un ricco borghese di origini inglesi considerato da tutti i cittadini di Ostenda (la città natale dell’artista) come un buonannulla: quest’ultimo finirà infatti corrodendo sé medesimo nell’alcol e favorendo cospicuamente il generale schernimento nei suoi confronti. La madre, invece, gestiva un negozio dove Ensor era solito recarsi fin da giovane per fornire aiuto o anche più semplicemente per acuire la sua sensibilità artistica attraverso l’osservazione degli oggetti in vendita. Malgrado questi vaghi accenni d’affetto, la situazione familiare del pittore restò sempre molto arida e lontana dal concedergli la forza d’animo di prendere le distanze dalla sua parentela. Da ciò emerge anche il rapporto ambivalente di Ensor con le donne: “Ah, la donna e la sua maschera di carne, di carne viva diventata per davvero maschera di cartone…”. Sempre la madre, per altro, non voleva che il figlio dipingesse dei nudi femminili attingendo direttamente da modelli in carne e ossa. Nell’evoluzione pittorica di questo autore si assiste ad una fase iniziale composta da vedute paesaggistiche ispirate all’impressionismo e ritratti realistici, come quello in cui mischia narcisisticamente la sua identità con quella dell’artista fiammingo del periodo barocco Pieter Paul Rubens: otterrà in tal caso un dipinto austero ed enigmatico, ma anche faceto per via del cappello di paglia corredato di fiorellini con differenti cromie (“Ensor con il cappello fiorito” 1883-1888). Giunse poco più tardi il periodo maggiormente produttivo per Ensor, quello collocabile tra il 1885 e il 1895, anni in cui si avvicinò brevemente al gruppo avanguardistico de “I Venti”, che proponeva un’educazione culturale spaziante dalle arti visive, alla musica, alla poesia. Proprio in questo decennio l’utilizzo delle maschere rappresentò la vera svolta dell’arte ensoriana, seppur non di quelle africane che appassioneranno diversi altri artisti nel corso di tutto il Novecento. Di queste ultime ebbe a dire: “Condanno senza remissione la maschera cresciuta male degli inferni d’Africa… Al diavolo i tratti e le attrazioni facili, e il vecchio gioco del feticcio negroide o gorillato”. Venerò piuttosto le maschere capaci di evocare atmosfere carnevalesche come quelle respirabili tutt’oggi al Carnevale di Binche, in Belgio, dove una moltitudine di Gilles compiono la loro sfilata tra le profusioni dionisiache della folla. E infatti lo stesso Ensor scrisse: “Bisogna essere degni dell’Arte di casa nostra, arte sana senza paura né rimproveri. Abbasso i leopardi di contrabbando! Forza ai nostri gilles e ai nostri leoni!”

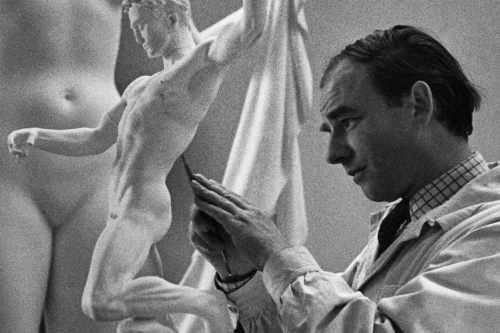

D’autant plus que le corps humain est construit selon les proportions du fameux « nombre d’or » présent partout dans la nature, à croire que la Création procède d’une intelligence faisant se conjoindre mathématiques et harmonie(1).

D’autant plus que le corps humain est construit selon les proportions du fameux « nombre d’or » présent partout dans la nature, à croire que la Création procède d’une intelligence faisant se conjoindre mathématiques et harmonie(1). L’homme et, bien entendu, la femme sont omniprésents dans l’ornementation du cadre de vie des Européens. Du reste, les musées mais aussi les lieux publics en témoignent abondamment. Avant que l’art contemporain, sous l’effet d’une pathologie équivalente au «

L’homme et, bien entendu, la femme sont omniprésents dans l’ornementation du cadre de vie des Européens. Du reste, les musées mais aussi les lieux publics en témoignent abondamment. Avant que l’art contemporain, sous l’effet d’une pathologie équivalente au «

The ancient Greeks are more than strange beings so far as post-60s “liberal democracy” is concerned. Certainly, the Greeks had that egalitarian and individualist sensitivity that Westerners are so known for.

The ancient Greeks are more than strange beings so far as post-60s “liberal democracy” is concerned. Certainly, the Greeks had that egalitarian and individualist sensitivity that Westerners are so known for.

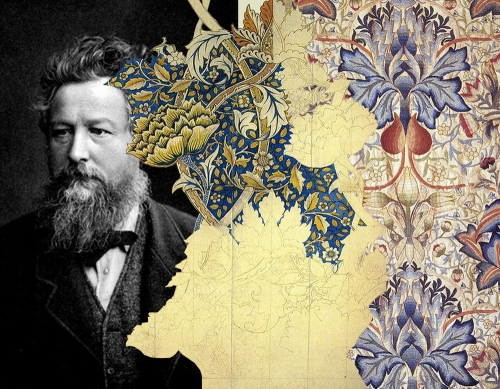

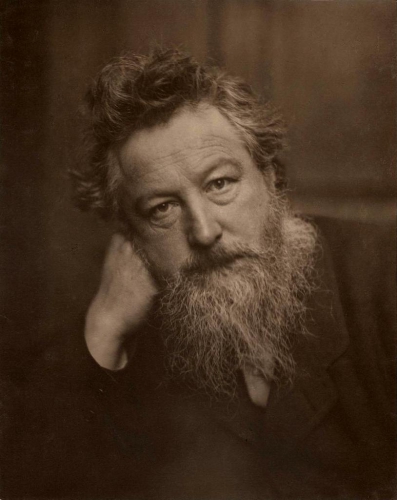

For a long time, Morris was considered the unofficial leader of the "Movement of Arts and Crafts". His main aim was the convergence of aesthetics and work, overcoming the industrialized impersonal production of the industrial age, that leads to the depersonalization of producer as well as the consumer of such goods, the transformation of work in the aesthetic and even (as it was in pre-Modern age) sacralized process. Morris was familiar with the works of Karl Marx, but he offered to solve problem of alienation, identified by socialist philosopher, by returning to manual labor and re-sacralization of production.

For a long time, Morris was considered the unofficial leader of the "Movement of Arts and Crafts". His main aim was the convergence of aesthetics and work, overcoming the industrialized impersonal production of the industrial age, that leads to the depersonalization of producer as well as the consumer of such goods, the transformation of work in the aesthetic and even (as it was in pre-Modern age) sacralized process. Morris was familiar with the works of Karl Marx, but he offered to solve problem of alienation, identified by socialist philosopher, by returning to manual labor and re-sacralization of production.

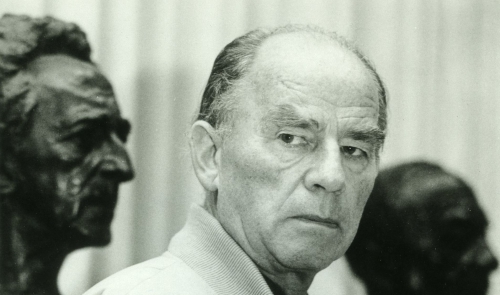

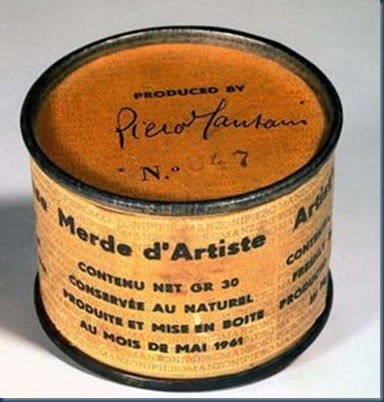

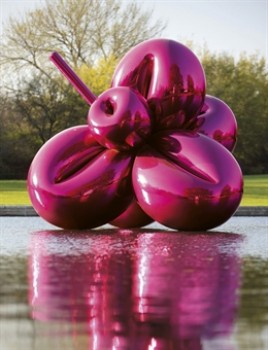

Difficile d’ignorer l’occupant. Impossible d’accepter cette métastase imbécile et envahissante qui tue l’art et les artistes et occulte la vraie création actuelle. Cette boursouflure de l’art dit contemporain est d’origine psycho-patho-sociologique et est systémique. Le Diable est d’origine mécanique… et, en l’occurrence, d’une mécanique d’ordre bureaucratique et financier où fonctionnaires, professeurs, critiques d’art et spéculateurs jouent à être plus stupides les uns que les autres pour mieux servir les appareils de pouvoir et d’argent dont ils sont les rouages. Il faut flinguer la crétinerie qui met l’art en danger, mais aussi l’humanité.

Difficile d’ignorer l’occupant. Impossible d’accepter cette métastase imbécile et envahissante qui tue l’art et les artistes et occulte la vraie création actuelle. Cette boursouflure de l’art dit contemporain est d’origine psycho-patho-sociologique et est systémique. Le Diable est d’origine mécanique… et, en l’occurrence, d’une mécanique d’ordre bureaucratique et financier où fonctionnaires, professeurs, critiques d’art et spéculateurs jouent à être plus stupides les uns que les autres pour mieux servir les appareils de pouvoir et d’argent dont ils sont les rouages. Il faut flinguer la crétinerie qui met l’art en danger, mais aussi l’humanité.

L’art contemporain de type français est un effet pervers de la bonne intention culturelle du socialisme mitterrandien des années 80. L’enfer est pavé de bonnes intentions merdiques, qui se retournent sur elles-mêmes puisqu’elles elles n’ont pas assez de contenu et de rigueur morale et intellectuelle. En fait la gauche culturelle a créé un appareil qui s’est mis à la remorque du grand libéralisme, de telle sorte qu’aujourd’hui le système en place allie les vertus du soviétisme et celle du capitalisme le plus débridé : c’est un comble !

L’art contemporain de type français est un effet pervers de la bonne intention culturelle du socialisme mitterrandien des années 80. L’enfer est pavé de bonnes intentions merdiques, qui se retournent sur elles-mêmes puisqu’elles elles n’ont pas assez de contenu et de rigueur morale et intellectuelle. En fait la gauche culturelle a créé un appareil qui s’est mis à la remorque du grand libéralisme, de telle sorte qu’aujourd’hui le système en place allie les vertus du soviétisme et celle du capitalisme le plus débridé : c’est un comble !

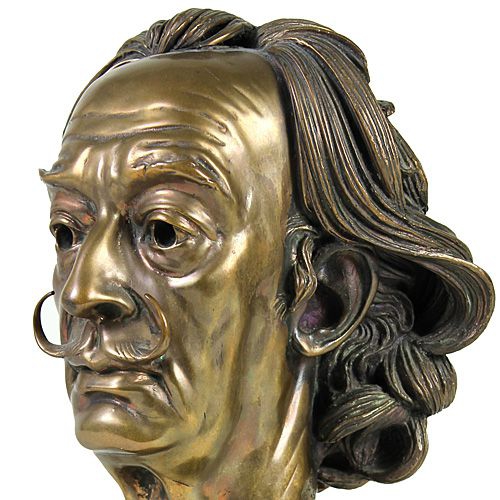

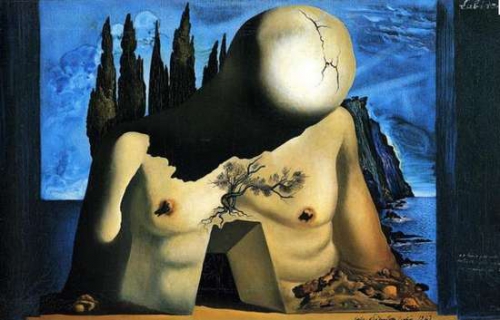

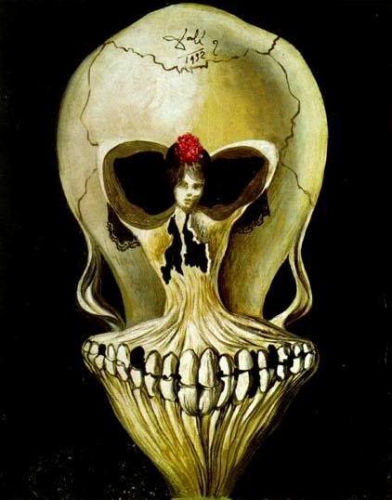

Despite his “far-out” art and aberrant — but very public — lifestyle, Dalí, like most of the Great Artists of the 20th century, was at least temperamentally a man of the Right.[20] Thus, even if you have no interest, or an active dislike, of “modern art”[21] or weirdoes, you will likely enjoy this tour through this little-known world of post-War anti-Leftists, a sort of avant-garde version of the circles of the Windsors or Mosleys.[22]

Despite his “far-out” art and aberrant — but very public — lifestyle, Dalí, like most of the Great Artists of the 20th century, was at least temperamentally a man of the Right.[20] Thus, even if you have no interest, or an active dislike, of “modern art”[21] or weirdoes, you will likely enjoy this tour through this little-known world of post-War anti-Leftists, a sort of avant-garde version of the circles of the Windsors or Mosleys.[22]