Kerry BOLTON

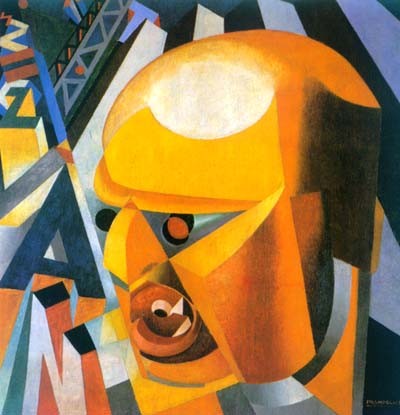

Filippo Marinetti is unlike most of the post-nineteenth Century cultural avant-garde who were rebelling against the spirit of several centuries of liberalism, rationalism, the rise of the democratic mass, industrialism, and the rule of the moneyed elite. His revolt against the leveling impact of the democratic era was not to hark back to certain perceived ‘golden ages’ such as the medieval eras upheld by Yeats and Evola, or to reject technology in favor of a return to rural life, as advocated by Henry Williamson and Knut Hamsun. To the contrary, Marinetti embraced the new facts of technology, the machine, speed, and dynamic energy, in a movement called Futurism.

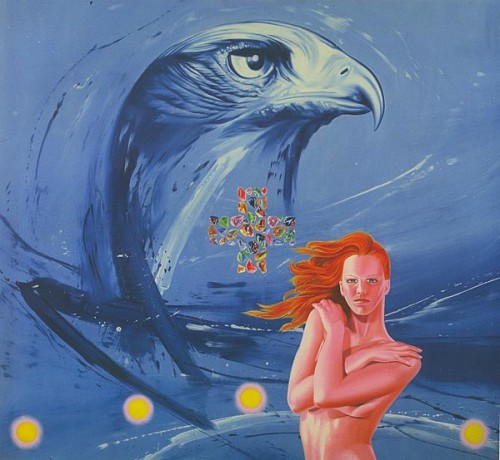

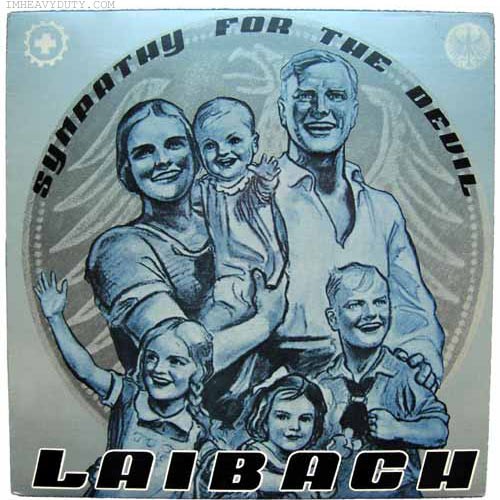

The futurist response to the facts of the new age is therefore a quite unique reaction from the anti-liberal literati and artists and one that continues to influence certain aspects of industrial and post-industrial sub cultures. An example of a contemporary cultural movement paralleling Futurists is New Slovenian Art, which like futurism embodies music, graphic arts, architecture, and drama. It is a movement whose influence is felt beyond the borders of Slovenia. The best-known manifestation of this art form is the industrial music group Laibach.

Marinetti is also the inventor of free verse in poetry, and Futurist adherents have had a lasting impact on architecture, motion pictures and the theater. The Futurists were the pioneers of street theatre. They inspired both the Constructivist movement in the USSR and the English Vorticists Ezra Pound and Wyndham Lewis.

Marinetti was born in Alexandria Egypt in 1876. He graduated in law in Genoa in 1899. Although the political and philosophical aspects of the course held his interest, he traveled frequently between France and Italy and interested himself in the avant-garde arts of the later nineteenth Century promoting young poets in both countries. He was already a strong critic of the conservative and traditional approaches of Italian poets. He was at this time an enthusiast for the modern, revolutionary music of Wagner, seeing it as assailing “equilibrium and sobriety . . . meditation and silence . . . ”

By 1904, Futurist elements had manifested in his writing, particularly in his poem Destruction that he called “an erotic and anarchist poem,” a eulogy to the “avenging sea” as a symbol of revolution. After an apocalyptic destruction, the process of rebuilding begins on the ruins of the “Old World.” Here already is the praise of death as a dynamic and transformative.

With the death of Marinetti’s father in 1907, his wealth allowed him to travel widely and he became a well-known cultural figure throughout Europe. Nietzsche was at this time one of the most well-known intellectuals who desired liberation from the old order. Nietzsche was widely read among the literati of Italy, and D’Annunzio was the most prominent in promoting Nietzsche. Among the other philosophers of particular importance whom Marinetti studied was the French syndicalist theorist Georges Sorel, who inclined towards the anarchism of Proudhon. This rejected Marxism in favor of a society comprised of small productive, cooperative units or syndicates; and founded a new myth of heroic action and struggle. Rejecting much of the pacifism of the left. Sorel viewed war as a dynamic of human action. Sorel in turn was himself influenced by Nietzsche, and applying the Nietzschean Overman to socialism, states that the working class revolution requires heroic leaders. Sorel became influential not only among Left wing syndicalists but also among certain radical nationalists in both France and Italy.

With the death of Marinetti’s father in 1907, his wealth allowed him to travel widely and he became a well-known cultural figure throughout Europe. Nietzsche was at this time one of the most well-known intellectuals who desired liberation from the old order. Nietzsche was widely read among the literati of Italy, and D’Annunzio was the most prominent in promoting Nietzsche. Among the other philosophers of particular importance whom Marinetti studied was the French syndicalist theorist Georges Sorel, who inclined towards the anarchism of Proudhon. This rejected Marxism in favor of a society comprised of small productive, cooperative units or syndicates; and founded a new myth of heroic action and struggle. Rejecting much of the pacifism of the left. Sorel viewed war as a dynamic of human action. Sorel in turn was himself influenced by Nietzsche, and applying the Nietzschean Overman to socialism, states that the working class revolution requires heroic leaders. Sorel became influential not only among Left wing syndicalists but also among certain radical nationalists in both France and Italy.

Futurist Manifesto

Marinetti’s artistic ideas crystallized in the Futurist movement that originated from a meeting of artists and musicians in Milan in 1909 to draft a Futurist Manifesto. With Marinetti were Carlo Carra, Umberto Boccioni, Luigi Russolo and Gino Severini. The manifesto was first published in the Parisian paper Le Figaro, and exhorted youth to, “Sing the love of danger, the habit of energy and boldness.”

The Futurists were contemptuous of all tradition, of all that is past:

The Futurists were contemptuous of all tradition, of all that is past:

We want to exult aggressive motion . . . we affirm that the magnificence of the world has been enriched by a new beauty: the beauty of speed.

The machine was poetically eulogized. The racing car became the icon of the new epoch, “which seems to run as a machine gun.” The Futurist aesthetic was to be joy in violence and war, as “the sole hygiene of the world.” Motion, dynamic energy, action, and heroism were the foundations of “the culture of the Futurist future. The fisticuffs, the sprint and the kick were expressions of culture. The Futurist Manifesto is as much a challenge to the political and social order as it is to the status quo in the arts.

It declared:

1. We intend to sing the love of danger, the habit of energy and fearlessness.

2. Courage, audacity, and revolt will be essential elements of our poetry.

3. Up to now literature has exalted a pensive immobility, ecstasy, and sleep. We intend to exalt aggressive action, a feverish insomnia, the racer’s stride, the mortal leap, the punch and the slap.

4. We affirm that the world’s magnificence has been enriched by a new beauty: the beauty of speed A racing car whose hood is adorned with great pipes, like serpents of an explosive breath–a roaring car that seems to ride on grape shot is more beautiful than the victory of Samothrace.

5. We want to hymn the man at the wheel, who hurls the lance of his spirit across the Earth, along the circle of its orbit.

6. The poet must spend himself with ardor, splendor, and generosity, to swell the enthusiastic fervor of the primordial elements. Except in struggle, there is no more beauty. No work without an aggressive character can be a masterpiece. Poetry must be conceived as a violent attack on unknown forces, to reduce and prostrate them before man.

7. We stand on the last promontory of the centuries. Why should we look back when what we want is to break down the mysterious doors of the impossible? Time and space died yesterday. We already live in the absolute, because we have created eternal, omnipresent speed.

8. We will glorify war–the world’s only hygiene–militarism, patriotism, the destructive gesture of freedom-bringers, the beautiful ideas that kill, and scorn for women.

9. We will destroy the museums libraries academies of every kind, will fight moralism feminism, every opportunistic or utilitarian cowardice.

10. We will sing of great crowds excited by work, by pleasure, and by riot. We will sing of the multi-colored, polyphonic tides of revolution in the modem capitals, we will sing of the vibrant nightly fervor of arsenals and shipyards blazing with violent electric motors, greedy railway stations that devour smoke-plumed serpents, factories hung on clouds by the crooked lines of their smoke; bridges that stride the rivers like giant gymnasts, flashing in the sun with a glitter of knives; adventurous steamers that sniff the horizon: deep-chested locomotives whose wheels paw the tracks like the hooves of enormous steel horses bridled by tubing: and the sleek flight of planes whose propellers chatter in the wind like banners and seem to cheer like an enthusiastic crowd.

It is from Italy that we launch through the world this violently upsetting incendiary manifesto of ours. With it, today, we establish Futurism, because we want to free this land from its smelly gangrene of professors, archaeologists, ciceroni and antiquarians. For too long has Italy been a dealer in second-hand clothes. We mean to free her from the numberless museums that cover her like so many graveyards.

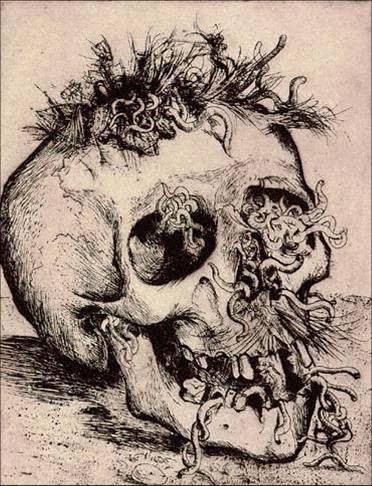

Museums: cemeteries! . . . Identical, surely, in the sinister promiscuity of so many bodies unknown to one another. Museums: public dormitories where one lies forever beside hated or unknown beings. Museums: absurd abattoirs of painters and sculptors ferociously slaughtering each other with color-blows and line-blows, the length of the fought-over walls!

That one should make an annual pilgrimage, just as one goes to the graveyard on All Souls’ Day, that we grant. That once a year one should leave a floral tribute beneath the Gioconda, I grant you that . . . but I don’t admit that our sorrows, our fragile courage, our morbid restlessness should be given a daily conducted tour through the museums. Why poison ourselves? Why rot? And what is there to see in an old picture except the laborious contortions of an artist throwing himself against the barriers that thwart his desire to express his dream completely? Admiring an old picture is the same as pouring our sensibility into a funerary urn instead of hurtling it far off in violent spasms of action and creation.

Do you then wish to waste all your best powers in this eternal and futile worship of the past, from which you emerge fatally exhausted, shrunken, beaten down?

In truth we tell you that daily visits to museums, libraries, and academies (cemeteries of empty exertion, Calvaries of crucified dreams, registries of aborted beginnings!) are, for artists, as damaging as the prolonged supervision by parents of certain young people drunk with their talent and their ambitious wills. When the future is barred to them, the admirable past may be a solace for the ills of the moribund, the sickly, the prisoner . . . But we want no part of it, the past, we the young and strong Futurists!

So let them come, the gay incendiaries with charred fingers! Here they are! Here they are! . . . Come on! set fire to the library shelves! Turn aside the canals to flood the museums! . . . Oh, the joy of seeing the glorious old canvases bobbing adrift on those waters, discolored and shredded! . . . Take up your pickaxes, your axes and hammers and wreck, wreck the venerable cities, pitilessly!

The oldest of us is thirty so we have at least a decade for finishing our work. When we are forty, other younger and stronger men will probably throw us in the wastebasket like useless manuscripts–we want it to happen!

They will come against us, our successors will come from far away, from every quarter, dancing to the winged cadence of their first songs, flexing the hooked claws of predators, sniffing dog-like at the academy doors the strong odor of our decaying minds which will have already been promised to the literary catacombs.

But we won’t be there . . . At last they’ll find us–one winter’s night–in open country, beneath a sad roof drummed by a monotonous rain. They’ll see us crouched beside our trembling aeroplanes in the act of warming our hands at the poor little blaze that our books of today will give out when they take fire from the flight of our images.

They’ll storm around us, panting with scorn and anguish, and all of them, exasperated by our proud daring, will hurtle to kill us. Driven by a hatred the more implacable the more their hearts will be drunk with love and admiration for us.

Injustice, strong and sane, will break out radiantly in their eyes. Art, in fact, can be nothing but violence, cruelty, and injustice.

The oldest of us is thirty: even so we have already scattered treasures, a thousand treasures of force, love, courage, astuteness, and raw will-power, have thrown them impatiently away, with fury, carelessly, unhesitatingly, breathless, and unresting . . . Look at us We are still untired! Our hearts know no weariness because they are fed with fire, hatred, and speed . . . Does that amaze you? It should, because you can never remember having lived! Erect on the summit of the world, once again, we hurl our defiance at the stars.

You have objections?–Enough! Enough! We know them . . . We’ve understood! . . . Our fine deceitful intelligence tells us that we are the revival and extension of our ancestors–Perhaps! . . . If only it were so!–But who cares? We don’t want to understand! . . . Woe to anyone who says those infamous words to us again! Lift up your heads. Erect on the summit of the world, once again we hurl our defiance after stars!”

A plethora of manifestos by Marinetti and his colleagues followed, futurist cinema, painting, music (“noise”), prose, plus the political and sociological implications.

War, the World’s Only Hygiene

War, the World’s Only Hygiene

Marinetti’s manifesto on war shows the central place violence and conflict have in the Futurist doctrine.

We Futurists, who for over two years, scorned by the Lame and Paralyzed, have glorified the love of danger and violence, praised patriotism and war, the hygiene of the world, are happy to finally experience this great Futurist hour of Italy, while the foul tribe of pacifists huddles dying in the deep cellars of the ridiculous palace at The Hague. We have recently had the pleasure of fighting in the streets with the most fervent adversaries of the war and shouting in their faces our firm beliefs:

1. All liberties should be given to the individual and the collectivity, save that of being cowardly.

2. Let it be proclaimed that the word Italy should prevail over the word Freedom.

3. Let the tiresome memory of Roman greatness be canceled by an Italian greatness a hundred times greater.

For us today, Italy has the shape and power of a fine Dreadnought battleship with its squadron of torpedo-boat islands. Proud to feel that the martial fervor throughout the nation is equal to ours, we urge the Italian government, Futurist at last, to magnify all the national ambitions, disdaining the stupid accusations of piracy, and proclaim the birth of Pan-Italianism.

Futurist poets, painters, sculptors, and musicians of Italy! As long as the war lasts let us set aside our verse, our brushes, scapulas, and orchestras! The red holidays of genius have begun! There is nothing for us to admire today but the dreadful symphonies of the shrapnel and the mad sculptures that our inspired artillery molds among the masses of the enemy.

Artistic Storm Trooper

Marinetti brought his dynamic character into an aggressive campaign to promote Futurism. The Futurists aimed to aggravate society out of bourgeoisie complacency and the safe existence through innovative street theater, abrasive art, speeches, and manifestos. The speaking style of Marinetti was itself bombastic and thunderous. The art was aggravating to conventional society and the art establishment. If a painting was that of a man with a mustache, the whiskers would be depicted with the bristles of a shaving brush pasted onto the canvas. A train would be depicted with the words “puff, puff.”

Both the words and deeds of the Futurists matched the nature of the art in expressing contempt for the status quo with its preoccupation with “pastism” or the “passe.” Marinetti for example, described Venice as “a city of dead fish and decaying houses, inhabited by a race of waiters and touts.”

To the Futurist Boccioni, Dante, Beethoven and Michelangelo were “sickening” Whilst Carra set about painting sounds, noises and even smells. Marinetti traversed Europe giving interviews, arranging exhibitions, meetings and dinners. Vermilion posters with huge block letters spelling ‘futurism’ were plastered throughout Italy on factories, in dance halls, cafes and town squares. Futurist performances were organized to provoke riot. Glue was put onto seats. Two tickets for the same seat would be sold to provoke a fight. “Noise music” would blare while poetry or manifestos were recited and paintings shown. Fruit and rotten spaghetti would be thrown from the audience, and the performances would usually end in brawls.

Marinetti replied to jeers with humor. He ate the fruit thrown at him. He welcomed the hostility as proving that Futurism was not appealing to the mediocre.

Politics

The first political contacts of Marinetti and the Futurists were from the Left rather than the Right, despite Marinetti’s extreme nationalism and call for war as the “hygiene of mankind.” There were syndicalists and even some anarchists who shared Marinetti’s views on the energizing and revolutionary nature of war and gave him a reception.

In 1909, Marinetti entered the general elections and issued a “First Political Manifesto” which is anti-clerical and states that the only Futurist political program is “national pride,” calling for the elimination of pacifism and the representatives of the old order. During that year, Marinetti was heavily involved in agitating for Italian sovereignty over Austrian-ruled Trieste. The political alliance with the extreme Left began with the anarcho-syndicalist Ottavio Dinale, whose paper reprinted the Futurist manifesto. The paper, La demolizione was not especially anarcho-syndicalist, but of a general combative nature, aiming to unite into one “fascio” all those of revolutionary tendencies, to “oppose with full energy the inertia and indolence that threatens to suffocate all life.” The phrase is distinctly Futurist.

Marinetti announced that he intended to campaign politically as both a syndicalist and a nationalist, a synthesis that would eventually arise in Fascism. In 1910, he forged links with the Italian Nationalist Association, which from its birth also had a pro-labor, syndicalist aspect. In 1913 a Futurist political manifesto was issued which called for enlargement of the military, an “aggressive foreign policy,” colonial expansionism, and “pan-Italianism”; a “cult” of progress, speed, and heroism; opposition to the nostalgia for monuments, ruins, and museums; economic protectionism, anti-socialism, anti-clericalism. The movement gained wide enthusiasm among university students.

Interventionism

The chance for Italy’s “place in the sun” came with World War I. Not only the nationalists were demanding Italy’s entry into the war, but so too were certain revolutionary syndicalists and a faction of socialists led by Mussolini. From the literati came D’Annunzio and Marinetti.

In a manifesto addressed to students in 1914 Marinetti states the purpose of Futurism and calls for intervention in the war. Futurism was the “doctor” to cure Italy of “pastism,” a remedy “valid for every country.” The “ancestor cult far from cementing the race” was making Italians “anaemic and putrid.” Futurism was now “being fully realized in the great world war.”

The present war is the most beautiful Futurist poem which has so far been seen. Futurism was the militarization of innovating artists.

The war would sweep away all the proponents of the old and senile, diplomats, professors, philosophers, archaeologists, libraries, and museums.

The war will promote gymnastics, sport, practical schools of agriculture, business and industrialists. The war will rejuvenate Italy: will enrich her with men of action, will force her to live no longer off the past, off ruins and the mild climate, but off her own national forces.

The Futurists were the first to organize pro-war protests. Mussolini and Marinetti held their first joint meeting in Milan on March 31st 1915. In April, both were arrested in Rome for organizing a demonstration.

Futurists were no mere windbags. Nearly all distinguished themselves in the war, as did Mussolini and D’Annunzio. The Futurist architect Sant Elia was killed. Marinetti enlisted with the Alpini regiment and was wounded and decorated for valor.

Futurist Party

In 1918, Marinetti began directing his attention to a new postwar Italy. He published a manifesto announcing the Futurist Political Party, which called for “Revolutionary nationalism” for both imperialism and social revolution. “We must carry our war to total victory.”

Demands of the manifesto included the eight hour day and equal pay for women, the nationalization and redistribution of land to veterans; heavy taxes on acquired and inherited wealth and the gradual abolition of marriage through easy divorce; a strong Italy freed, from nostalgia, tourists, and priests; industrialization and modernization of “moribund cities” that live as tourist centers. A Corporatist policy called for the abolition of parliament and its replacement with a technical government of 30 or 40 young directors elected form the trade associations.

The Futurist party concentrated its propaganda on the soldiers, and recruited many war veterans of the elite Arditi (daredevils), who had been the black-shirted shock troops of the army who would charge into battle stripped to the waist, a grenade in each hand and a dagger between their teeth.

In December 1919, the Futurists revived the “Fasci” or “groups.” which had been organized in 1914 and 1915 to campaign for war intervention, and from which was to emerge the Fascists.

Futurists and Fascists

The first joint post-war action between Mussolini and Marinetti took place in 1919 when a Socialist Party rally was disrupted in Milan.

That year Mussolini founded his own Fasci di Combattimento in Milan with the support of Marinetti and the poet Ungasetti. The futurists and the Arditi comprised the core of the Fascist leadership. The first Fascist manifesto was based on that of Marinetti’s Futurist party.

In April, against the wishes of Mussolini who thought the action premature, Marinetti led Fascists and Futurists and Arditi against a mass Socialist Party demonstration. Marinetti waded in with fists, but intervened to save a socialist from being severely beaten by Arditi. (To place the post-war situation in perspective, the Socialists had regularly beaten, abused, and even killed returning war veterans). The Fascists and futurists then proceeded to the offices of the Socialist Party paper Avanti, which they sacked and burned.

Marinetti stood as a Fascist candidate in the 1919 elections and persuaded Toscanini to do so. Whilst the Fascists held back, the Futurists threw their support behind the poet-soldier D’Annunzio’s takeover of Fiume. Marinetti arrived and was warmly welcomed by D’Annunzio.

When the Fascist Congress of 1920 refused to support the Futurist demand to exile the King and the Pope, Marinetti and other Futurists resigned from the Fascist party. Marinetti considered that the Fascist party was compromising with conservatism and the bourgeoisie. He was also critical of the Fascist concentration on anti-socialist agitation and on opposition to strikes. Certain futurist factions realigned themselves specifically with the extreme Left. In 1922, there were several Futurist exhibitions and performances organized by the Communist cultural association, Pro-letkul, which also arranged a lecture by Marinetti to explain the doctrine of Futurism.

Futurism and the Fascist Regime

When the Fascists assumed power in 1922 Marinetti, like D’Annunzio, was critically supportive of the regime. Marinetti considered: “The coming to power of the Fascists constitutes the realization of the minimum futurist program.”

Of Mussolini the statesman, Marinetti wrote: “Prophets and forerunners of the great Italy of today, we Futurists are happy to salute in our not yet 40-year-old Prime Minister of marvelous futurist temperament.”

In 1923, Marinetti began a rapprochement with the Fascists and presented to Mussolini his manifesto “The Artistic Rights Promoted by Italian Futurists.” Here he rejected the Bolshevik alignment of Futurists in the USSR. He pointed to the Futurist sentiments that had been expressed by Mussolini in speeches, alluding to Fascism being a “government of speed, curtailing everything that represents stagnation in the national life.”

Under Mussolini’s leadership, writes Marinetti:

Fascism has rejuvenated Italy. It is now his duty to help us overhaul the artistic establishment . . . . The political revolution must sustain the artistic revolutions Marinetti was among the Congress of Fascist Intellectuals who in 1923 approved the measures taken by the regime to restore order by curtailing certain constitutional liberties amidst increasing chaos caused by both out-of-control radical Fascist squadisti and anti-Fascists.

At the 1924 Futurist Congress, the delegates upheld Marinetti’s declaration:

The Italian Futurists, more than ever devoted to ideas and art, far removed from politics, say to their old comrade Benito Mussolini, free yourself from parliament with one necessary and violent stroke. Restore to Fascism and Italy the marvelous, disinterested, bold, anti-socialist, anti-clerical, anti-monarchical spirit . . . Refuse to let monarchy suffocate the greatest, most brilliant and just Italy of tomorrow . . . Quell the clerical opposition . . . . With a steely and dynamic aristocracy of thought.

In 1929, Marinetti accepted election to the Italian Academy, considering it important that “Futurism be represented” He was also elected secretary of the Fascist Writer’s Union and as such was the official representative for fascist culture. Futurism became a part of fascist cultural exhibitions and was utilized in the propaganda art of the regime. During the 1930s, in particular the Fascist cultural expression was undergoing a drift away from tradition and towards futurism, with the fascist emphasis on technology and modernization. Mussolini had already in 1926 defined the creation of a “fascist art” that would be based on a synthesis culturally as it was politically: “traditionalistic and at the same time modern.”

In 1943, with the Allies invading Italy, the Fascist Grand Council deposed Mussolini and surrendered to the occupation forces. The fascist faithful established a last stand, in the north, named the Italian Social Republic.

With a new idealism, even former Communist and liberal leaders were drawn to the Republic. The Manifesto of Verona was drafted, restoring various liberties, and championing labor against plutocracy within the vision of a united Europe. Marinetti continued to be honored by the Social Republic. He died in 1944.

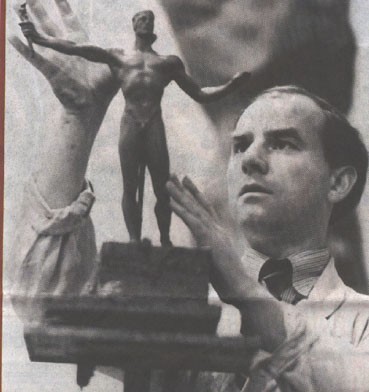

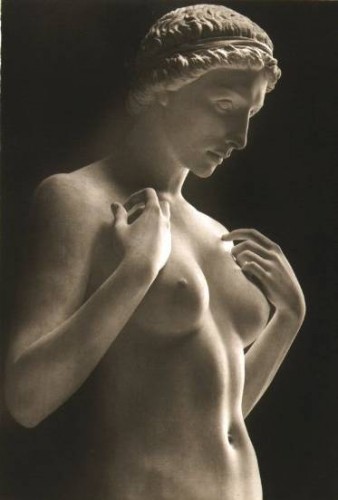

All of Breker’s pieces have precedents in the ancient world, but this has to be understood in an active rather than a passive or re-directed way. If we think of the Hellenism which Alexander’s all-conquering armies inspired deep into Asia Minor (and beyond), then pieces like the Laocoön at the Vatican or the full-nude portrait of Demetrius the First of Syria, whose modelling recalls Lysippus’ handling, are definite precursors. (This latter piece is in the National Museum in Rome.) Yet Breker’s work is quite varied, in that it contains archaic, semi-brutalist, unshorn, martial relief and post-Cycladic material. There is also the resolution of an inner tension leading to a Stoic calm, or a heroic and semi-religious rest, that recalls the Mannerist art of the sixteenth century. Certain commentators, desperate for some sort of affiliation to modernism in order to “save” Breker, speak loosely of Expressionist sub-plots. This is quite clearly going too far — but it does draw attention to one thing . . . namely, that many of these sculptures indicate an achievement of power, a rest or beatitude after turmoil. They are indicative of Hemingway’s definition of athletic beauty — that is to say, grace under pressure or a form of same.

All of Breker’s pieces have precedents in the ancient world, but this has to be understood in an active rather than a passive or re-directed way. If we think of the Hellenism which Alexander’s all-conquering armies inspired deep into Asia Minor (and beyond), then pieces like the Laocoön at the Vatican or the full-nude portrait of Demetrius the First of Syria, whose modelling recalls Lysippus’ handling, are definite precursors. (This latter piece is in the National Museum in Rome.) Yet Breker’s work is quite varied, in that it contains archaic, semi-brutalist, unshorn, martial relief and post-Cycladic material. There is also the resolution of an inner tension leading to a Stoic calm, or a heroic and semi-religious rest, that recalls the Mannerist art of the sixteenth century. Certain commentators, desperate for some sort of affiliation to modernism in order to “save” Breker, speak loosely of Expressionist sub-plots. This is quite clearly going too far — but it does draw attention to one thing . . . namely, that many of these sculptures indicate an achievement of power, a rest or beatitude after turmoil. They are indicative of Hemingway’s definition of athletic beauty — that is to say, grace under pressure or a form of same. Another interesting exchange between Muller and Breker in this interview concerns the Shoah. (It is important to realise that this highly-charged chat is not an exercise in reminiscence. It concerns the morality of revolutionary events in Europe and their aftermath.) By any stretch, Breker declares himself to be a believer and that the criminal death through a priori malice of anyone, particularly due to their ethnicity, is wrong. At first sight this appears to be an unremarkable statement. A bland summation would infer that the neo-classicist was a believer in Christian ethics, et cetera. . . . Yet, viewed again through a different premise, something much more revolutionary emerges. Breker declares himself to be a “believer” (that is to say, an “exterminationist” to use the vocabulary of Alexander Baron); yet even to affirm this is to admit the possibility of negation or revision (itself a criminal offense in the new Germany). For the most part contemporary opinion mongers don’t declare that they believe in Global warming, the moon shot, or the link between HIV and AIDS — they merely affirm that no “sane” person doubts it.

Another interesting exchange between Muller and Breker in this interview concerns the Shoah. (It is important to realise that this highly-charged chat is not an exercise in reminiscence. It concerns the morality of revolutionary events in Europe and their aftermath.) By any stretch, Breker declares himself to be a believer and that the criminal death through a priori malice of anyone, particularly due to their ethnicity, is wrong. At first sight this appears to be an unremarkable statement. A bland summation would infer that the neo-classicist was a believer in Christian ethics, et cetera. . . . Yet, viewed again through a different premise, something much more revolutionary emerges. Breker declares himself to be a “believer” (that is to say, an “exterminationist” to use the vocabulary of Alexander Baron); yet even to affirm this is to admit the possibility of negation or revision (itself a criminal offense in the new Germany). For the most part contemporary opinion mongers don’t declare that they believe in Global warming, the moon shot, or the link between HIV and AIDS — they merely affirm that no “sane” person doubts it.

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

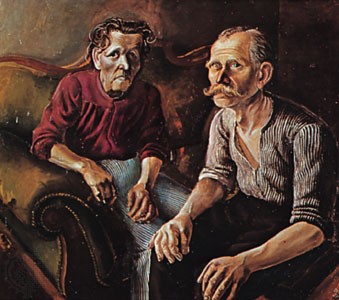

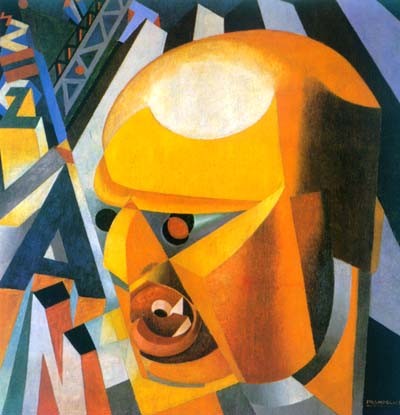

En 1914, Dix s'engageait en tant que volontaire dans l'armée. L'expérience devait, comme toute sa génération, profondément le marquer. S'il est une habitude de dépeindre Dix comme un pacifiste, son journal de guerre et sa correspondance montrent un caractère sensiblement différent. La guerre fut perçue par Dix, comme par beaucoup d'autres jeunes gens en Allemagne, comme l'offre d'un nouveau départ, d'une coupure radicale avec ce qui était ressenti comme la pesanteur de l'époque wilhelminienne, sa mesquinerie, son étroitesse, sa provincialité qu'une certaine littérature a si bien décrites. Elle annonçait la fin inévitable d'une époque. Les premiers combats, l'ampleur des destructions devaient, bien sûr, limiter l'enthousiasme des départs, mais le gigantisme des cataclysmes que réservait la guerre, n'en présentait pas moins quelque chose de fascinant. Le pacifiste Dix se rapproche par bien des aspects du Jünger des journaux de guerre. L'épreuve de la guerre pour Ernst Jünger trempe de nouveaux types d'hommes dans le monde d'orages et d'acier qu'offrent les combats dans les tranchées.

En 1914, Dix s'engageait en tant que volontaire dans l'armée. L'expérience devait, comme toute sa génération, profondément le marquer. S'il est une habitude de dépeindre Dix comme un pacifiste, son journal de guerre et sa correspondance montrent un caractère sensiblement différent. La guerre fut perçue par Dix, comme par beaucoup d'autres jeunes gens en Allemagne, comme l'offre d'un nouveau départ, d'une coupure radicale avec ce qui était ressenti comme la pesanteur de l'époque wilhelminienne, sa mesquinerie, son étroitesse, sa provincialité qu'une certaine littérature a si bien décrites. Elle annonçait la fin inévitable d'une époque. Les premiers combats, l'ampleur des destructions devaient, bien sûr, limiter l'enthousiasme des départs, mais le gigantisme des cataclysmes que réservait la guerre, n'en présentait pas moins quelque chose de fascinant. Le pacifiste Dix se rapproche par bien des aspects du Jünger des journaux de guerre. L'épreuve de la guerre pour Ernst Jünger trempe de nouveaux types d'hommes dans le monde d'orages et d'acier qu'offrent les combats dans les tranchées.  Une des peintures les plus justement célèbres de Dix, la Rue de Prague

Une des peintures les plus justement célèbres de Dix, la Rue de Prague

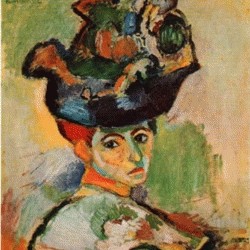

En 1911, par scission du N.K.V.M. est fondé le mouvement Le Cavalier Bleu (Der Blaue Reiter) avec August Macke, Franz Marc, Paul Klee (le moins doué) et Vassily Kandinsky. L’idée du nom vient du Cavalier Bleu de Kandinsky (1903) tout autant que de la prédilection de Franz Marc pour les dessins et peintures de chevaux (Cheval bleu, 1911). Kandinsky déclare : « Le cheval porte son cavalier avec vigueur et rapidité, mais c’est le cavalier qui conduit le cheval. Le talent conduit l’artiste à de hauts sommets, mais c’est l’artiste qui maîtrise son talent ». August Macke, qui fut une des figures du N.K.V.M. illustre superbement la vitalité du Cavalier Bleu à ses débuts (Paysage avec trois jeunes filles, 1911). Il meurt sur le front de Champagne à 27 ans. Franz Marc est un artiste majeur lui aussi, c’est sans doute un des plus doués, des plus nets et affirmés du groupe (Renard d’un bleu noir, 1911). Il meurt en 1916 près de Verdun.

En 1911, par scission du N.K.V.M. est fondé le mouvement Le Cavalier Bleu (Der Blaue Reiter) avec August Macke, Franz Marc, Paul Klee (le moins doué) et Vassily Kandinsky. L’idée du nom vient du Cavalier Bleu de Kandinsky (1903) tout autant que de la prédilection de Franz Marc pour les dessins et peintures de chevaux (Cheval bleu, 1911). Kandinsky déclare : « Le cheval porte son cavalier avec vigueur et rapidité, mais c’est le cavalier qui conduit le cheval. Le talent conduit l’artiste à de hauts sommets, mais c’est l’artiste qui maîtrise son talent ». August Macke, qui fut une des figures du N.K.V.M. illustre superbement la vitalité du Cavalier Bleu à ses débuts (Paysage avec trois jeunes filles, 1911). Il meurt sur le front de Champagne à 27 ans. Franz Marc est un artiste majeur lui aussi, c’est sans doute un des plus doués, des plus nets et affirmés du groupe (Renard d’un bleu noir, 1911). Il meurt en 1916 près de Verdun.

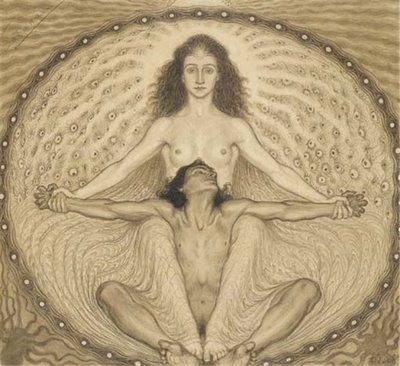

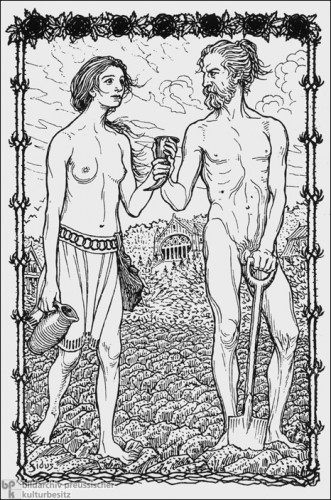

Les revenus générés par cette activité éditoriale demeurèrent assez sporadiques, ce qui obligea les habitants de la Maison Fidus, auxquels s’était jointe la femme écrivain du mouvement de jeunesse, Gertrud Prellwitz, à adopter un mode de vie très spartiate. L’avènement du national-socialisme ne changea pas grand chose à leur situation. Fidus avait certes placé quelque espoir en Adolf Hitler parce que celui-ci était végétarien et abstinent, voulait que les Allemands se penchent à nouveau sur leurs racines éparses, mais cet espoir se mua en amère déception. La politique culturelle nationale-socialiste refusa de reconnaître la pertinence des visions des ermites de Woltersdorf et stigmatisa « les héros solaires éthérés » de Fidus comme une expression de l’ « art dégénéré ». Dans le catalogue de l’exposition sur l’ « art dégénéré » de 1937, on pouvait lire ces lignes : « Tout ce qui apparaît, d’une façon ou d’une autre, comme pathologique, est à éliminer. Une figure de valeur, pleine de santé, même si, racialement, elle n’est pas purement germanique, sert bien mieux notre but que les purs Germains à moitié affamés, hystériques et occultistes de Maître Fidus ou d’autres originaux folcistes ». L’artiste ne recevait plus beaucoup de commandes. Beaucoup de revues du mouvement « Lebensreform » ou du mouvement de jeunesse, pour lesquelles il avait travaillé, cessèrent de paraître. Sa deuxième femme, Elsbeth, fille de l’écrivain Moritz von Egidy, qu’il avait épousée en 1922, entretenait la famille en louant des chambres d’hôte (« site calme à proximité de la forêt, jardin ensoleillé avec fauteuils et bain d’air, Blüthner-Flügel disponibles »). L’ « original folciste » a dû attendre sa 75ème année, en 1943, pour obtenir le titre de professeur honoris causa et pour recevoir une pension chiche, accordée parce qu’on avait finalement eu pitié de lui.

Les revenus générés par cette activité éditoriale demeurèrent assez sporadiques, ce qui obligea les habitants de la Maison Fidus, auxquels s’était jointe la femme écrivain du mouvement de jeunesse, Gertrud Prellwitz, à adopter un mode de vie très spartiate. L’avènement du national-socialisme ne changea pas grand chose à leur situation. Fidus avait certes placé quelque espoir en Adolf Hitler parce que celui-ci était végétarien et abstinent, voulait que les Allemands se penchent à nouveau sur leurs racines éparses, mais cet espoir se mua en amère déception. La politique culturelle nationale-socialiste refusa de reconnaître la pertinence des visions des ermites de Woltersdorf et stigmatisa « les héros solaires éthérés » de Fidus comme une expression de l’ « art dégénéré ». Dans le catalogue de l’exposition sur l’ « art dégénéré » de 1937, on pouvait lire ces lignes : « Tout ce qui apparaît, d’une façon ou d’une autre, comme pathologique, est à éliminer. Une figure de valeur, pleine de santé, même si, racialement, elle n’est pas purement germanique, sert bien mieux notre but que les purs Germains à moitié affamés, hystériques et occultistes de Maître Fidus ou d’autres originaux folcistes ». L’artiste ne recevait plus beaucoup de commandes. Beaucoup de revues du mouvement « Lebensreform » ou du mouvement de jeunesse, pour lesquelles il avait travaillé, cessèrent de paraître. Sa deuxième femme, Elsbeth, fille de l’écrivain Moritz von Egidy, qu’il avait épousée en 1922, entretenait la famille en louant des chambres d’hôte (« site calme à proximité de la forêt, jardin ensoleillé avec fauteuils et bain d’air, Blüthner-Flügel disponibles »). L’ « original folciste » a dû attendre sa 75ème année, en 1943, pour obtenir le titre de professeur honoris causa et pour recevoir une pension chiche, accordée parce qu’on avait finalement eu pitié de lui.

The Futurists were contemptuous of all tradition, of all that is past:

The Futurists were contemptuous of all tradition, of all that is past:

Georges Remi (devenu Hergé par inversion des initiales) est né à Etterbeek (Bruxelles) le 22 mai 1907 à 7h30. Il aimait à rappeler cette naissance sous le signe des Gémeaux (1). Peut-être explique-t-elle la récurrence du thème de la gémellité dans ses albums (les DupontDupond, les frères Halambique, etc.).

Georges Remi (devenu Hergé par inversion des initiales) est né à Etterbeek (Bruxelles) le 22 mai 1907 à 7h30. Il aimait à rappeler cette naissance sous le signe des Gémeaux (1). Peut-être explique-t-elle la récurrence du thème de la gémellité dans ses albums (les DupontDupond, les frères Halambique, etc.).

Indeed, as Griffin makes clear, fascists and para-fascists are usually, by their very nature, bitter enemies. While para-fascists may co-opt some superficial characteristics of their fascist opponents, in power they tend to ruthlessly suppress the expression of revolutionary fascism. When para-fascism attempts to co-opt fascism by sharing power – as Antonescu attempted in Romania with the Legionaries — conflict is inevitable, since the objectives of the two parties are completely different: para-fascist ossification vs. fascist palingenetic regeneration. Thus, in Romania, civil war between para-fascists and fascists led to the victory of the para-fascists, and the exile of the fascist forces. The idea that Antonescu was “fascist” is a byproduct of either ideological ignorance or ideological mendacity, a Marxist desire to strip their fascist competitors of revolutionary dynamism and reduce them to mere “bourgeois hooligans.”

Indeed, as Griffin makes clear, fascists and para-fascists are usually, by their very nature, bitter enemies. While para-fascists may co-opt some superficial characteristics of their fascist opponents, in power they tend to ruthlessly suppress the expression of revolutionary fascism. When para-fascism attempts to co-opt fascism by sharing power – as Antonescu attempted in Romania with the Legionaries — conflict is inevitable, since the objectives of the two parties are completely different: para-fascist ossification vs. fascist palingenetic regeneration. Thus, in Romania, civil war between para-fascists and fascists led to the victory of the para-fascists, and the exile of the fascist forces. The idea that Antonescu was “fascist” is a byproduct of either ideological ignorance or ideological mendacity, a Marxist desire to strip their fascist competitors of revolutionary dynamism and reduce them to mere “bourgeois hooligans.” In some sense, perhaps the “purest” brand of fascism was that of

In some sense, perhaps the “purest” brand of fascism was that of With respect to Antliff’s book itself, chapter topics include

With respect to Antliff’s book itself, chapter topics include

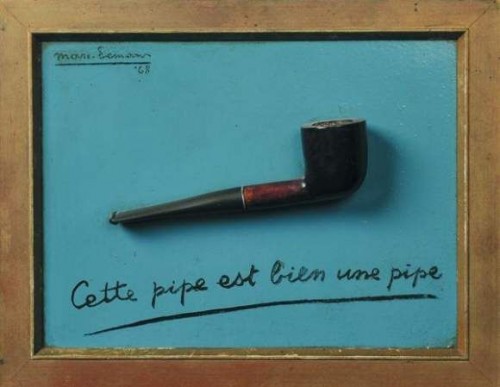

C'est grâce à la rencontre de Geert Van Bruaene, alors directeur du Cabinet Maldoror en l'Hôtel Ravenstein, que le jeune Marc Eemans a été intié à la poésie présurréaliste des «Chants de Maldoror» et c'est également alors qu'il entra en contact avec Camille Goemans et E.L.T. Mesens qui allaient bientôt devenir ses compagnons de

C'est grâce à la rencontre de Geert Van Bruaene, alors directeur du Cabinet Maldoror en l'Hôtel Ravenstein, que le jeune Marc Eemans a été intié à la poésie présurréaliste des «Chants de Maldoror» et c'est également alors qu'il entra en contact avec Camille Goemans et E.L.T. Mesens qui allaient bientôt devenir ses compagnons de

LAIBACH: «Was ist Kunst?»

LAIBACH: «Was ist Kunst?» D'inspiration authentiquement totalitaire et avant-gardiste, ce concert devait durablement marquer les critiques slovènes, et asseoir la notoriété laibachienne. Sa contribution artistique au renouveau culturel slovène allait préparer les esprits à l'inéluctable et indubitablement favoriser le réveil de la petite république. Bientôt la Yougoslavie imploserait, débandade initiée par Ljubljana, qui déclarerait son indépendance le 2 juillet 1990: «L'esthétique nationaliste romantique est une phobie du service culturel progressiste. LAIBACH est organiquement lié à son environnement natal et entretient jalousement un lien instinctif avec la nation slovène et son passé, tout en étant constamment conscient de son rôle dans le polygone culturel et politique de la Slovénie» (entretien paru en 1986 pour la revue HHT). Une fois supplémentaire, le renouveau culturel identitaire allait préparer et jeter les bases des futures révolutions politiques.

D'inspiration authentiquement totalitaire et avant-gardiste, ce concert devait durablement marquer les critiques slovènes, et asseoir la notoriété laibachienne. Sa contribution artistique au renouveau culturel slovène allait préparer les esprits à l'inéluctable et indubitablement favoriser le réveil de la petite république. Bientôt la Yougoslavie imploserait, débandade initiée par Ljubljana, qui déclarerait son indépendance le 2 juillet 1990: «L'esthétique nationaliste romantique est une phobie du service culturel progressiste. LAIBACH est organiquement lié à son environnement natal et entretient jalousement un lien instinctif avec la nation slovène et son passé, tout en étant constamment conscient de son rôle dans le polygone culturel et politique de la Slovénie» (entretien paru en 1986 pour la revue HHT). Une fois supplémentaire, le renouveau culturel identitaire allait préparer et jeter les bases des futures révolutions politiques.