Parution du numéro 438 du Bulletin Célinien

Sommaire :

Céline et Gide

András Hevesi, premier traducteur de Céline en hongrois (2e partie)

L’Éternel féminin dans Voyage au bout de la nuit

En poursuivant votre navigation sur ce site, vous acceptez l'utilisation de cookies. Ces derniers assurent le bon fonctionnement de nos services. En savoir plus.

Ex: https://www.breizh-info.com/

Bernard Rio mène une double carrière d’écrivain et de journaliste. Il est l’auteur d’une soixantaine de livres, et a été couronné par plusieurs prix littéraires pour ses essais historiques et ethnologiques, notamment « Voyage dans l’au-delà : les Bretons et la mort » en 2013 (prix Histoire de l’Académie littéraire de Bretagne et des Pays de la Loire), et « Pèlerins sur les chemins du Tro Breiz » en 2016 (Prix du salon du Livre de Vannes). Il est aussi l’auteur de quatre romans : « Un dieu sauvage » publié chez Coop Breizh en 2020, « Le voyage de Mortimer » et « Les masques irlandais » publiés aux éditions Balland en 2017 et 2018, « Vagabond de la belle étoile » aux éditions L’Age d’Homme en 2005.

Nous l’avons interrogé au sujet de son dernier ouvrage, « Un dieu sauvage ».

Breizh-info.com : D’où vous est venue l’idée d’écrire « un dieu sauvage » ?

C’est une question que je ne m’étais pas encore posée. D’où vient l’idée d’écrire une fiction ? Il y a des livres qui s’inscrivent dans une actualité, ceux publiés à l’occasion du bicentenaire de la mort de Napoléon Bonaparte par exemple. Il y en a d’autres qui correspondent à une recherche personnelle et originale, ce fut le cas par exemple de mes essais « L’arbre philosophal », « Voyage dans l’au-delà » ou encore « Le cul bénit, amour sacré et passions profanes ». Mes romans relèvent d’une autre perspective. Ils s’imposent à moi. Pour chacun d’entre eux, j’ai dérogé à mes règles d’écriture, abandonnant ainsi la recherche préliminaire et le plan, pour privilégier l’intuition et l’imagination. Ceci dit, « Un dieu sauvage » est un roman à part car je ne l’ai pas écrit d’un seul jet. Je l’ai pris et repris périodiquement pendant plusieurs années jusqu’à la dernière version achevée en décembre 2019. Il a été chroniqué qu’il s’agissait d’un roman prémonitoire Le récit a certes été écrit avant la crise sanitaire du Coronavirus, et contient des correspondances avec la situation actuelle. Néanmoins, les mesures politico-sanitaires qui attentent aux libertés de l’homme de la rue et que celui-ci découvre, avec ingénuité aujourd’hui, ont été décrites depuis des années dans des sphères aussi différentes que des revues scientifiques ou des ouvrages de science-fiction. Sans doute ai-je été plus attentif aux intersignes de l’invisible (le monde des dieux) et ai-je exercé mon esprit critique sur ce que je voyais et entendais depuis des lustres (le monde des hommes), ce qui m’a conduit a écrire cette dystopie. Ce roman participe cependant moins de la veine d’Aldous Huxley ou de George Orwell que d’un autre genre. Selon une critique littéraire, « Un dieu sauvage » serait plus proche d’« Au château d’Argol » (Julien Gracq), « Sur les falaises de marbre » (Ernst Junger) et « Le désert des tartares » (Dino Buzatti). J’y souscris pleinement.

Breizh-info.com : Peut-on dire que votre livre est archéofuturiste, dans le sens où il mêle notre Antiquité la plus profonde, et notre futur le plus proche… ?

Oui, vous pouvez le qualifier ainsi. Mon récit revisite les mythes antiques tout en s’inscrivant dans une réflexion contemporaine : le devenir de l’homme dans un monde totalitariste et ses capacités de survie, d’évasion et de liberté.

Le récit fonctionne sur trois plans : la terre, l’homme et le divin. De même que les hommes croient dominer le monde et le temps alors qu’ils ne sont que des marionnettes entre les mains des dieux (selon l’heureuse formule d’Alain Daniélou), la caste au pouvoir que je décris est davantage dans l’illusion que dans la réalité. Le matérialisme recouvert d’un vernis moral n’est qu’un faux semblant. Je développe aussi dans cette fiction une idée qui m’est chère, et qui pourrait s’apparenter à la physique quantique. Et si le temps n’était pas linéaire ? Si une autre logique inversait la cause et la conséquence ? Si le futur était déjà réalisé, si le passé était encore là, si le présent était une chimère ? Ce qui n’est pas la conséquence du passé pourrait-il être la conséquence du futur ?

Le roman illustre le concept de rétro-causalité. Il revisite le concept de l’espace-temps en lui octroyant une flexibilité par commutation de lignes d’univers. Dans le livre, le personnage du mystérieux Ignotus, invisible pour les Prêcheurs au pouvoir mais réel aux yeux des femmes, incarne cette permanence du passé, ce futur réalisé et ce présent illusoire. Il est le messager, celui qui condamne, celui qui enfante, celui qui fait peur et celui qui enchante.

Ce serait une sinistre infirmité que de penser la réalité comme un temps fini et un espace réduit au visible. La raison est ici soumise à la critique de l’illusion. La matière est assujettie à la conscience. L’ordre, qui n’est qu’un désordre organisé par le pouvoir, se décompose. La peur qui cimente le pouvoir disparait mot après mot, image après image. Albert Camus écrivait dans « L’homme révolté » (1951) que tout blasphème était une participation au sacré.

Breizh-info.com : En choisissant un personnage féminin comme élément déclencheur de la révolte, ne faites-vous pas du conformisme dans les temps actuels, bénis pour les femmes ?

Ah Ah ! Me tenant éloigné des faux-débats télévisés, je me contrefous de ce qui est bien ou mal pensant, normé, genré ou je ne-sais-quoi encore. Senta la tisseuse est à l’image de la Pythie de Delphes ou de la Morrigan irlandaise.

L’histoire est « animée » par sept personnages : Quatre femmes symbolisant les trois Grâces et leur muse, et un trio d’hommes composé de l’inconnu incarnant un cavalier de l’Apocalypse ainsi que du duo de médecins représentant l’antagonisme du pouvoir. Ces septénaires contribuent tous, délibérément ou involontairement, à la destruction de l’ordre correspondant à chacune des sept étapes de l’évolution spirituelle : pulsion (conscience du corps physique), émotion (conscience des sentiments), raison (conscience de l’intelligence), intuition (conscience de l’inconscient), spiritualité (conscience du détachement), volonté (conscience de l’action), réalisation (conscience de l’éternité). Les quatre femmes ouvrent ainsi la voie à une spiritualisation, au renversement du positivisme des Prêcheurs, au retour de la conscience. Pour les suivre dans cette voie, il suffit simplement de changer de perspective et de se laisser emporter par l’intuition dans un univers elliptique où le visible et l’invisible s’enchevêtrent, où l’esprit domine la matière.

Chacun de mes personnages se pose des questions au fur et à mesure que les événements improbables emportent la raison. Le hasard bouleverse la vie de celui qui l’accepte pour ce qu’il n’est pas, c’est-à-dire un simple hasard, et pour ce qu’il est : le destin, une correspondance qui vient du futur. En se déconditionnant, les quatre femmes se laissent emporter par la crue des mots qui charrie les épaves du vieux monde. La résilience opère alors. La vie ne se profile plus comme une ligne droite mais se déroule comme une spirale. L’être humain est dans la main des dieux et cependant doté d’un libre-arbitre. Il a toujours le choix du chemin qu’il emprunte.

Breizh-info.com : Votre roman est une profonde critique de notre monde moderne. L’écrivain que vous êtes s’y sent-il étranger ? Qu’est-ce qui vous dérange le plus ?

Le monde occidental est désenchanté et même déprimant si on ne prend pas un peu de recul. C’est l’aboutissement d’une idéologie matérialiste apparue à la Renaissance qui a culminé à la Révolution française et a gangréné l’ensemble des classes sociales. Cependant je trouve la situation actuelle passionnante. J’estime d’ailleurs avoir eu la chance d’assister en direct en 1989 à l’effondrement du bloc soviétique (lequel a pris à contrepied tous les experts qui occupent les plateaux de télévision). Un de mes plus beaux souvenirs de journalisme fut la comparaison que je fis entre deux voyages à Berlin-Est, avant et après la chute du mur. Aujourd’hui, bis repetitae, c’est le capitalisme qui va s’effondrer. Je n’ai pas peur de ce qui va se passer et je n’entends pas jouer le rôle de supplétit pour conserver les petits privilèges matériels d’un monde voué à sa perte. Et il n’y a pas lieu à mes yeux de sauver ce système où plus rien n’est sacré. Dans ce système, j’inclus toutes les institutions civiles et religieuses. Il est symptomatique qu’en France toutes les églises et religions, (y compris les groupuscules néodruidiques qui se sont particulièrement ridiculisés en officiant masqués dans la nature), aient collaboré obséquieusement avec le pouvoir, en appelant leurs fidèles à courber l’échine. Ces « gens d’église » ont oublié que les sanctuaires ne relèvent pas du profane mais du sacré. Lors des épidémies, dans l’antiquité et au Moyen Age, il y avait une lecture magico-symbolique des événements, et donc une interprétation et une réponse appropriée. Par exemple, je pense notamment aux cultes et vertus prophylactiques de saint Sébastien et saint Roch. Les légendes hagiographiques sont comparables à des palimpsestes qui recèlent sous le vernis de la reformulation chrétienne, la présence de substrats mythologiques anciens. En l’occurence, saint Sébastien s’apparente au Sagittaire (du latin saggitarius, l’archer), dans le calendrier zodiacal, c’est-à-dire dans la mémoire d’un temps mythique. Le martyre par sagittation du saint peut être mis en parallèle avec le dieu archer de la mythologie grecque Apollon et ses flèches pourvoyeuses de la peste. Dans l’Iliade, le dieu à l’arc d’argent assouvit sa vengeance contre les Achéens en les frappant de ses flèches qui répandent l’épidémie dans la ville. Cette allégorie ne peut être qu’un motif littéraire si on se place sur un plan profane. Elle peut être aussi interprétée sur un plan sacré. Dans la mythologie, l’archer a une vocation particulière : contrôler, réactiver ou prendre l’énergie vitale de la nature. Lancer une flèche est une opération magique qui permet d’agir à distance, de réactiver le saint (Sébastien), le dieu (Apollon), le soleil en le piquant avec des flèches par une opération relevant de la magie sympathique, afin que l’astre ne meure pas et que le printemps advienne. Or, pendant l’épidémie, les sanctuaires ont été fermés avec la complicité du clergé. Ce qui est un sacrilège. Il a été interdit aux dévots d’honorer les saints protecteurs, ce qui est un non sens. Cette absence de sacralité et de mystère, voilà ce qui me gêne le plus dans la société contemporaine.

Breizh-info.com : « Finalement, tout devient possible lorsque le monde se transforme en chaos » dites-vous. C »est à la fois un message terrifiant, mais aussi porteur d’énormément d’espoir non ?

Dans ce roman, la révolte solitaire devient universelle. Au sentiment de l’absurde d’une situation succèdent les temps de la rébellion, de la mort puis de la renaissance.

La révolte de mes héroïnes ne se résume pas à une contestation des esclaves, à une colère et à un affrontement, elle se place entre deux temps, le temps d’avant, la guerre, et le temps d’après, l’unité. Cette révolte des femmes prend peu à peu les allures d’une délivrance tandis que la révolte d’un autre personnage, le docteur, s’avère une aliénation. La première est métaphysique et suit les voies du sacré, c’est une évolution acceptée qui ne cherche pas à nier ou à tuer Dieu mais à intégrer et à manifester une part d’éternité. La seconde est une révolution manichéenne. Elle se limite à une alternative entre le bien et le mal, c’est un rapport de force entre le maître et l’esclave, le second n’aspirant qu’à remplacer le premier dans cette relation dominant-dominé. Dans la mythologie, l’un des travaux d’Hercule/Héraklès est de nettoyer les écuries du roi Augias, dont le nom signifie « brillant, rayonnant ». Le roi voit (il rayonne) ses 3000 bœufs mais ne sent pas leurs déjections. Ressentir, c’est sentir la chose (du latin res). Aujourd’hui les politiciens ne sentent plus la chose publique (res publica). Il appartient au héros de détourner les eaux des fleuves pour purger l’immonde.

« Un dieu sauvage », Bernard Rio, éditions Coop Breizh, 208 pages, 18 euros

Crédit photo : DR

[cc] Breizh-info.com, 2021, dépêches libres de copie et de diffusion sous réserve de mention et de lien vers la source d’origine

00:12 Publié dans Entretiens, Littérature, Livre, Livre, Traditions | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : bernard rio, livre, littérature, lettres, lettres françaises, littérature française, bretagne, tradition |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

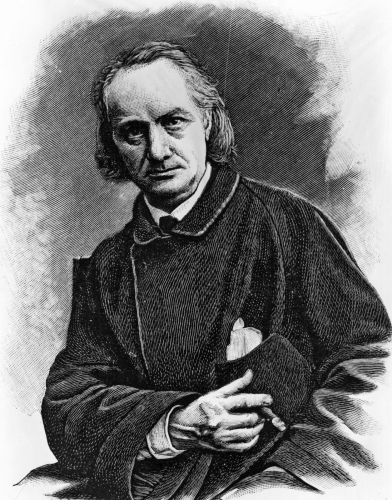

Aujourd'hui, Baudelaire serait la victime de la ‘’cancel culture‘’ et des ligues de vertu

par Giulio Meotti

Source : Il Foglio & https://www.ariannaeditrice.it/

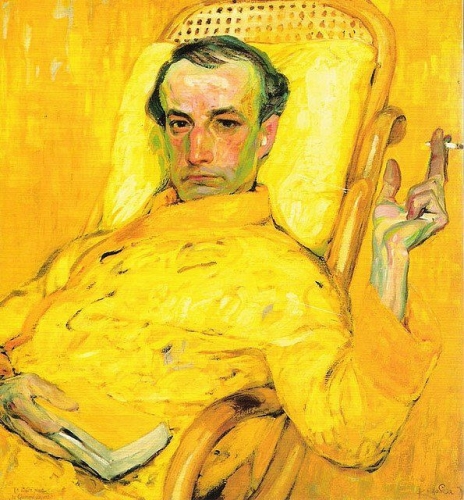

C'est l'époque où Peter Pan est interdit aux enfants par la bibliothèque publique de Toronto, où l'éditeur néerlandais Blossom Books retire Mahomet de l'Enfer de Dante et où l'on enregistre chaque jour une censure pour satisfaire les indignés professionnels. C'est le moment où Dan Franklin, qui a publié Ian McEwan et Salman Rushdie aux éditions Jonathan Cape, déclare: "Je ne publierais pas Lolita aujourd'hui. Avec MeToo et les médias sociaux, vous pouvez susciter l'indignation en un clin d'œil. Si on me proposait Lolita aujourd'hui, je ne le ferais jamais passer et un comité de trentenaires dirait: "Si vous publiez ce livre, nous allons tous démissionner". Presque normal alors de lire Michel Schneider, biographe de Charles Baudelaire, qui dans le Point déclare que son favori, l'auteur des Fleurs du mal, serait aujourd'hui fustigé et censuré.

Rédacteur des lettres à la mère de Baudelaire ("Cette maladresse maternelle me fait t'aimer davantage") et auteur du livre Baudelaire. Les années profondes, Schneider écrit qu'’’en ces temps d'insignifiance où l'on ne croit plus ni à Dieu ni au Diable, ni au bien ni au mal, ces Fleurs du mal, ce livre d'une vie condamnée en justice, mélange impur de sublime et de satanique, se sont effacées." C'est le bicentenaire de la naissance de Baudelaire et l'édition, qu'il voulait "définitive" mais n'a pas réussi à faire publier, est rééditée. "Baudelaire a vomi le progressisme et l'égalitarisme triomphants de notre monde postmoderne, et il est difficile d'entendre son dégoût et sa haine (de lui-même avant tout) sans frémir devant une telle prescience".

Rédacteur des lettres à la mère de Baudelaire ("Cette maladresse maternelle me fait t'aimer davantage") et auteur du livre Baudelaire. Les années profondes, Schneider écrit qu'’’en ces temps d'insignifiance où l'on ne croit plus ni à Dieu ni au Diable, ni au bien ni au mal, ces Fleurs du mal, ce livre d'une vie condamnée en justice, mélange impur de sublime et de satanique, se sont effacées." C'est le bicentenaire de la naissance de Baudelaire et l'édition, qu'il voulait "définitive" mais n'a pas réussi à faire publier, est rééditée. "Baudelaire a vomi le progressisme et l'égalitarisme triomphants de notre monde postmoderne, et il est difficile d'entendre son dégoût et sa haine (de lui-même avant tout) sans frémir devant une telle prescience".

Voici l'édition publiée par Calmann-Lévy en 1868 et jamais réimprimée depuis. Il comprend les poèmes rejetés par la censure. Un volume restauré par Pierre Brunel, professeur émérite à la Sorbonne. "'Les Fleurs du mal' serait censuré aujourd'hui", écrit Schneider. "Leur contenu ferait probablement l'objet de demandes d'interdiction et de campagnes vindicatives de la part des ligues de vertu du féminisme radical et de la ‘cancel culture’" Ce "Dante d'un âge déchu", comme Baudelaire est appelé par Barbey d'Aurevilly, a été envoyé devant les magistrats pour "offense à la morale chrétienne", tandis que le procureur Pinard (le même que dans le procès de Madame Bovary) s'exclame: "Croyons-nous que certaines fleurs au parfum étourdissant soient bonnes à respirer ?".

Aujourd'hui, écrit Michel Schneider, on lirait dans les vers de Baudelaire un hymne au harcèlement de rue et une justification de l'inceste. "J'ai toujours été surpris que les femmes soient autorisées à entrer dans les églises", écrit Baudelaire. Ça ne passerait jamais.

"Et pour ne pas offenser les "racisés", poursuit Schneider dans le Point, ces lignes devraient être réécrites dans des éditions destinées à un "public sensible": « Je pense au nègre, décharné et céphalique qui foule la boue et regarde, d'un œil ahuri, les cocotiers... ».

Et même si nous ne trouvions pas dans les vers du poète un hymne à quelque méfait idéologique, Baudelaire serait fustigé pour sa haine mesquine de la démocratie: "Nous avons tous l'esprit républicain dans les veines, comme la variole dans les os. Nous sommes démocratisés et syphilisés". Un réactionnaire baudelairien, donc. "Oui, vive la révolution!" écrit-il encore. "Toujours ! Mais je ne suis pas dupe! Je dis: vive la Révolution! Comme je le dirais: vive la destruction ! Vive l'expiation ! Vive la punition ! Vive la mort !".

Et même si nous ne trouvions pas dans les vers du poète un hymne à quelque méfait idéologique, Baudelaire serait fustigé pour sa haine mesquine de la démocratie: "Nous avons tous l'esprit républicain dans les veines, comme la variole dans les os. Nous sommes démocratisés et syphilisés". Un réactionnaire baudelairien, donc. "Oui, vive la révolution!" écrit-il encore. "Toujours ! Mais je ne suis pas dupe! Je dis: vive la Révolution! Comme je le dirais: vive la destruction ! Vive l'expiation ! Vive la punition ! Vive la mort !".

De plus, un ennemi haineux de la fraternité entre les peuples: "Il est difficile d'assigner une place au Belge dans l'échelle des êtres vivants. Cependant, nous pouvons dire qu'il doit être classé entre le singe et le mollusque. C'est un ver que nous avons oublié d'écraser. Il est complètement stupide, mais il est aussi résistant que les mollusques". Mais le plus grand péché de Baudelaire est de nous rappeler que croire au progrès, à l'amélioration de l'humanité, débarrassée de ses erreurs et de ses malheurs, est l'un des meilleurs moyens de faire tourner les guillotines.

15:07 Publié dans Actualité, Littérature | Lien permanent | Commentaires (1) | Tags : actualité, baudelaire, charles baudelaire, littérature, littérature française, poésie, lettres, lettres françaises, ligues de vertu, cancel culture, censure |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

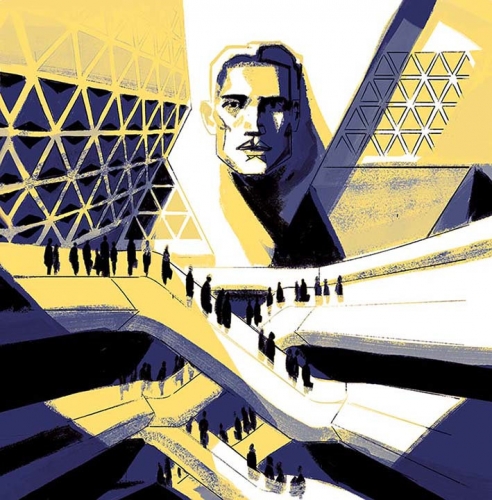

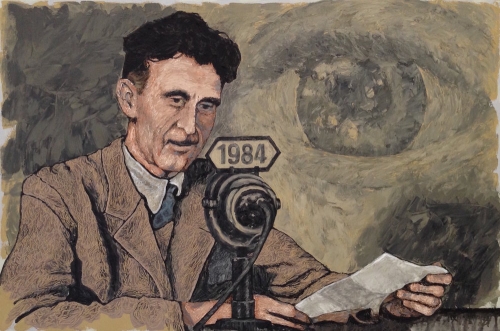

1984, le chef-d'œuvre de George Orwell maintenant en bande dessinée

Par Marco Valle

Ex : https://blog.ilgiornale.it/valle/2021/04/06/

Emilio Cecchi, grand critique littéraire du vingtième siècle, n'avait aucun doute. À sa sortie, il a défini 1984, comme un "livre mémorable". Un livre d'une tristesse désespérée, obsessionnelle, qui place définitivement George Orwell à l'une des toutes premières places de la littérature anglaise d'aujourd'hui. Un jugement clair et fulminant qui a déplu à une grande partie de la scène intellectuelle de l'époque, très attachée au socialisme réel et pas du tout enthousiasmée par ce chef-d'œuvre anti-utopique qui annonçait un monde sombre, plombé, sans espoir. Trop d'analogies avec le "paradis soviétique", trop de similitudes entre l'omniprésent "Big Brother" et l'omniscient camarade Joseph Staline. Ce n'est pas un hasard si Palmiro Togliatti a rejeté le roman d’Orwell comme "une flèche de plus tirée par la bourgeoisie avec son arc déglingué". Au Royaume-Uni, pour les snobs pro-communistes d'Oxford et des cercles similaires - pour la Happy society des années 40 et 50, le marxisme était un partenaire social amusant et parfois un hobby, celui de faire de l'espionnage... - George n'était rien de plus qu'un tory anarchist, un anarchiste conservateur. Une nuisance à éviter. Un écrivain à ne pas lire.

Heureusement, les exorcismes communistes et les délires des "idiots utiles" de l'Albionique (et pas seulement), ont été vains. Inutiles. Depuis plus de soixante-dix ans, 1984 reste l'un des livres les plus lus (et souvent mal cité...) au monde. Une victoire posthume pour le tuberculeux George, qui meurt le 21 janvier 1950 à seulement quarante-six ans, après une vie mouvementée entre l'Inde (il est né à Motihari en 1903), l'Angleterre, la Birmanie coloniale, la France, l'Espagne et à nouveau la Grande-Bretagne, dernière étape.

Le passage ibérique pendant la guerre civile fut fondamental, où il assista, à Barcelone en 1937, au massacre par les staliniens des anarchistes du POUM, le pittoresque parti anarcho-syndicaliste de Catalogne. Une tragédie dans la tragédie qui lui a fait comprendre comment les prétendus "champions" des opprimés, une fois l'oppresseur chassé, se révélaient être les pires tyrans: au nom de leurs "vertus", tout pouvoir devait être délégué au parti unique, une autorité absolue, inhumaine, qui surveillerait et contrôlerait les choses, les mots, les sentiments. Des vies. D'où Hommage à la Catalogne et, surtout, La Ferme des animaux, allégorie féroce mais sublime du régime soviétique, lieu où "tous les animaux sont libres, mais certains sont plus égaux que d'autres".

Puis ce fut le tour de 1984, l'impossible révolte de Winston et Julia dans le monde dominé par l’ Ingsoc (acronyme de "socialisme anglais"), le parti maître de l'Océanie, le super-État de l'hémisphère occidental. Entrons dans l'histoire. Ici, chaque pensée, chaque parole est scrutée par la psycho-police et par les différents ministères, celui de l'Amour, celui de la Vérité, de l'Abondance, etc.

En Océanie, le passé est continuellement réécrit à travers la "Novlangue", un idiome de base destiné à remplacer l'Oldpseak, la langue des souvenirs. Tout doit être effacé et réécrit comme le souhaite l'autorité. Le doute n'est pas permis. Une discipline inexorable est imposée aux membres du parti : celui qui n'obtempère pas, celui qui hésite, celui qui ne comprend pas, celui qui a une lueur d'intelligence, est vaporisé. Éliminé. Effacé. Les adeptes de l’Ingsoc se voient même refuser une vie affective, et encore moins une vie sexuelle. L'amour est un blasphème. En effet, une offense au chef suprême, le Big Brother qui se tient au-dessus de tout et de tous. Une image qui apparaît à travers les télé-écrans (autre intuition géniale) dans les places, dans les bureaux, dans les maisons. Partout. Le golem qui domine la vie publique et privée de chacun. Le moloch qui voit tout et ne pardonne rien.

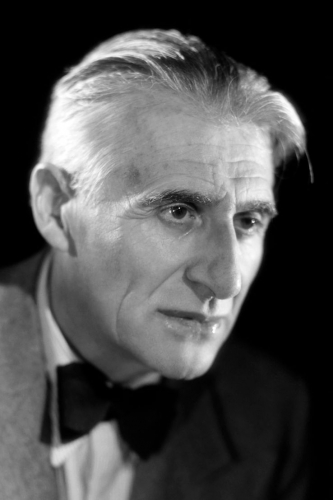

Xavier Coste.

Le cauchemar - ou la vision - d'Orwell est désormais, grâce aux crayons de l'artiste français Xavier Coste, un splendide roman graphique, un conte parfait sur les nuages parlants, absolument fidèle au texte original. Pas une tâche facile après le splendide film de Michael Radford avec Richard Burton (sa dernière et touchante apparition) et John Hurt. Pourtant, l'effet est aussi impressionnant qu'engageant. Coste a reconstitué avec audace et rigueur les décors - un Londres sinistre parsemé d'inquiétants bâtiments ministériels, d'intérieurs claustrophobiques et de petits jardins tristes - donnant vie aux personnages principaux et à leur environnement humain misérable - les deux amants, les bureaucrates, les prolétaires, les flics et les espions - ; un jeu habile que l'artiste a segmenté en quatre gammes de couleurs qui rythment parfaitement le développement de l'intrigue.

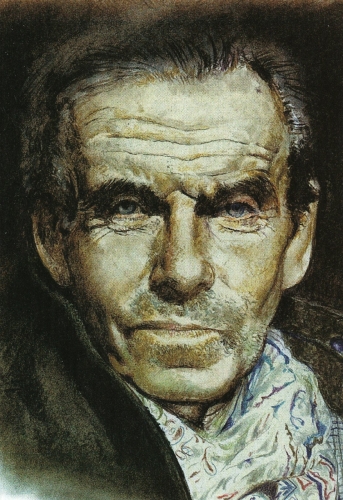

Stefano Zecchi.

L'album, publié en France par Sarbacane, est maintenant également publié en Italie par Ferrogallico editrice (Milan, 2021. 240 pages, € 25.00) avec une préface précieuse de Stefano Zecchi. Dans sa note dense, le professeur prévient: "1984 est une dénonciation atroce non seulement du totalitarisme, de la communication globale et de Big Brother qui nous observe inlassablement d'on ne sait où, écrit Zecchi, mais, en particulier, de la stupidité et de la misère de l'homme. D'un homme incapable de croire en lui-même, d'avoir du courage, de voir grand, d'un homme capable de ne défendre que sa misérable médiocrité (spirituelle), de peur de perdre la santé de son corps, d’un homme vil et traître. Une description lucide et dramatique d'une humanité indifférente et lâche, prête à livrer sa propre personne à n'importe qui afin de se libérer du poids de la responsabilité de choisir et de décider avec sa propre tête. C'est cela, 1984: une accusation effrayante et inapplicable de l'être humain".

Comme d'habitude, le professeur vénitien a raison. Ajoutons, à la lumière de l'actualité décourageante qui nous entoure et nous afflige, une petite note. L'ouvrage, mille huit cent quarante-quatre, est bien plus (comme on le prétend encore) qu'un livre anticommuniste et Orwell n'est pas seulement un critique acerbe, à juste titre impitoyable, du soviétisme, mais il est bien plus encore. Orwell est le héraut de vérités profondes et dérangeantes. Tous sont mal à l'aise à sa lecture. Ennuyeux. Orwell est terriblement d'actualité.

Voix solitaire, il y a déjà sept décennies que l'écrivain a compris comment la technologie au service de l'idéologie (quelle qu'elle soit) donne naissance et forme à un mélange aussi efficace qu'étouffant et inhumain. Extrêmement cruel et anonyme. Dans un écrit peu connu de 1946 - Second thoughts on James Burnham -, George mettait en garde contre le danger qui guette (aussi ou surtout) ces entités étatiques qui (hier comme aujourd'hui) se racontent et se représentent comme des démocraties accomplies, respectueuses des droits, des lois, des constitutions. Du pacte social.

"S'il n'est pas combattu, le totalitarisme peut triompher partout". Un avertissement plus valable que jamais en cette première partie du millénaire, alors que partout en Occident des dérives sont en cours - accélérées, ce n'est pas un hasard, par la pandémie, un fait sanitaire transformé en hystérie médiatique – dérives qui visent de plus en plus à restreindre les libertés individuelles, à modifier les langues et les relations sociales, à imposer de nouveaux régimes de travail et, surtout, à recomposer idéologiquement l'Histoire. L'objectif final, le véritable pari de tout projet totalitaire, car "qui contrôle le passé contrôle le futur: qui contrôle le présent contrôle le passé". Orwell dixit.

11:50 Publié dans Bandes dessinées, Littérature, Livre, Livre | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : george orwell, 1984, lettres, lettres anglaises, littérature, littérature anglaise, bande dessinée, graphic novel |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

11:08 Publié dans Littérature | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : michel houellebecq, littérature, lettres, lettres françaises, littérature française |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

Parution du numéro 438 du Bulletin Célinien

Sommaire :

Céline et Gide

András Hevesi, premier traducteur de Céline en hongrois (2e partie)

L’Éternel féminin dans Voyage au bout de la nuit

Au-delà de la mort, la fidélité de Bernard Morlino à Emmanuel Berl (1892-1976) est admirable. Ses nombreuses conversations rue de Montpensier, où Berl habita pendant 40 ans, furent son université. Outre une biographie, il poussa cette fidélité jusqu’à récolter à la Bibliothèque Nationale les articles de Berl pour en faire un recueil qui fut édité par Bernard de Fallois. Aujourd’hui, il est à l’origine de la réédition de Prise de sang, initialement paru en 1946, dans lequel Berl s’interroge sur la place des juifs en France, lui qui s’était toujours considéré français avant d’être juif. Curieux personnage qu’Emmanuel Berl. Appartenant à la même génération que Céline, il devint, comme lui, un pacifiste viscéral après avoir connu l’horreur de la Grande Guerre. Raison pour laquelle il soutint les accords de Munich. « J’ai été munichois. Il est étrange qu’en écrivant cette phrase, j’éprouve presque la sensation de faire un aveu ; l’immense majorité des Français fut non seulement résignée à Munich, mais exaltée par lui. » Au début de l’année 1939, ce pacifisme l’amena à accuser un certain Bollack, directeur d’une importante agence de presse, de corrompre des journalistes français pour qu’ils incitassent à la guerre contre l’Allemagne, accusation qui s’avéra fondée. Cela ne l’empêcha pas d’être l’un de ceux qui dénoncèrent très tôt le caractère militariste et antisémite du national-socialisme.

Au-delà de la mort, la fidélité de Bernard Morlino à Emmanuel Berl (1892-1976) est admirable. Ses nombreuses conversations rue de Montpensier, où Berl habita pendant 40 ans, furent son université. Outre une biographie, il poussa cette fidélité jusqu’à récolter à la Bibliothèque Nationale les articles de Berl pour en faire un recueil qui fut édité par Bernard de Fallois. Aujourd’hui, il est à l’origine de la réédition de Prise de sang, initialement paru en 1946, dans lequel Berl s’interroge sur la place des juifs en France, lui qui s’était toujours considéré français avant d’être juif. Curieux personnage qu’Emmanuel Berl. Appartenant à la même génération que Céline, il devint, comme lui, un pacifiste viscéral après avoir connu l’horreur de la Grande Guerre. Raison pour laquelle il soutint les accords de Munich. « J’ai été munichois. Il est étrange qu’en écrivant cette phrase, j’éprouve presque la sensation de faire un aveu ; l’immense majorité des Français fut non seulement résignée à Munich, mais exaltée par lui. » Au début de l’année 1939, ce pacifisme l’amena à accuser un certain Bollack, directeur d’une importante agence de presse, de corrompre des journalistes français pour qu’ils incitassent à la guerre contre l’Allemagne, accusation qui s’avéra fondée. Cela ne l’empêcha pas d’être l’un de ceux qui dénoncèrent très tôt le caractère militariste et antisémite du national-socialisme.

Ses relations avec Céline furent pour le moins étonnantes. Lorsque parut Bagatelles pour un massacre, il publia un article dans lequel il relevait que « le lyrisme emporte dans son flux la malice et la méchanceté ». Et d’ajouter : « Juif ou pas juif, zut et zut ! j’ai dit que j’aimais Céline. Je ne m’en dédirai pas ¹. » Un an plus tard, son libéralisme l’incita à condamner l’abus de censure que constituait, à ses yeux, le décret Marchandeau ² qui visait notamment les pamphlets céliniens. Il acceptait, en effet, l’idée de l’antisémitisme politique. Comme le lui reprochait son ami Malraux, il n’avait pas le sens de l’ennemi. Ce qu’il reconnaissait volontiers : « La haine n’est pas mon fort. » La mansuétude dont il fit preuve envers Céline n’était pas un cas particulier si l’on en juge par ces lignes : « Je suis persuadé que son cœur est pur de haine et que la provocation au meurtre fut toujours chez lui, figure de rhétorique. Les Juifs le croient antisémite Ils ont tort. Maurras n’est pas antisémite parce qu’il aime la Raison et qu’il n’est pas démagogue. Il ne vous reproche d’être juif que si vous ne dites pas comme lui… ». Aveuglement ? Libéralisme poussé jusqu’à l’outrance ? Les deux, sans doute… Après la guerre, il considéra que le racisme fut une formidable épidémie des années trente : « On ne parle pas avec indignation d’une épidémie. » Il dira à Bernard Morlino qu’il faut passer l’éponge sur Bagatelles pour ne retenir de Céline que l’inventeur d’un nouveau langage. Mais que restera-t-il de Berl ? Non pas ses pamphlets contre l’esprit bourgeois ou ses essais historiques, mais deux superbes récits parus après la guerre, Sylvia (1952) et Rachel et autres grâces (1965), sortes de confession d’un homme en quête de lui-même. Il rejoint ainsi Céline qui, après la guerre, rejetait la littérature des idées pour ne valoriser que celle où l’émotion prime.

• Emmanuel BERL, Prise de sang (présentation et bio-chronologie de Bernard Morlino ; postface de Bernard de Fallois), Les Belles Lettres, coll. “Le goût des idées”, 2020 (13,90 €)

00:36 Publié dans Littérature, Revue | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : louis-ferdinand céline, revue, lettres, lettres françaises, littérature, littérature française |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

00:49 Publié dans Littérature | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : hans fallada, littérature, littérature allemande, lettres, lettres allemandes |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

00:05 Publié dans Littérature | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : maurice barrès, littérature, littérature française, lettres, lettres française, nationalisme |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

00:58 Publié dans Littérature, Philosophie, Révolution conservatrice | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : ernst jünger, révolution conservatrice, philosophie, nationalisme révolutionnaire, lettres, lettres allemandes, littérature, littérature allemande |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

par Martin Sieff

Ex: https://reseauinternational.net/

La British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC), heureusement amplifiée par le Public Broadcasting System (PBS) aux États-Unis qui diffuse ses World News, continue de déverser régulièrement ses larmes sur le prétendu chaos économique en Russie et sur l’état misérable imaginaire du peuple russe.

Ce ne sont que des mensonges, bien sûr. Les mises à jour régulières de Patrick Armstrong, qui font autorité, y compris ses rapports sur ce site web, sont un correctif nécessaire à une propagande aussi grossière.

Mais au milieu de tous leurs innombrables fiascos et échecs dans tous les autres domaines (y compris le taux de mortalité par habitant le plus élevé de COVID-19 en Europe, et l’un des plus élevés au monde), les Britanniques restent les leaders mondiaux dans la gestion des fake news. Tant que le ton reste modéré et digne, littéralement toute calomnie sera avalée par le crédule et chaque scandale et honte grossière pourra être dissimulée en toute confiance.

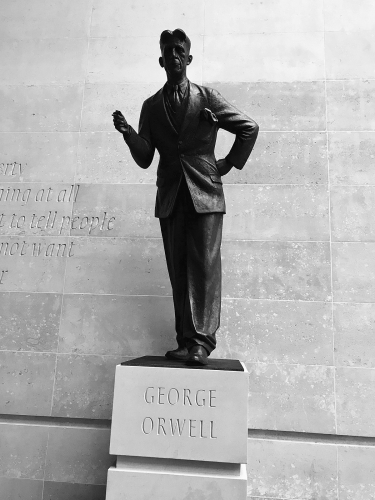

Rien de tout cela n’aurait surpris le grand George Orwell, aujourd’hui décédé. Il est à la mode ces jours-ci de le présenter sans cesse comme un zombie (mort mais prétendument vivant – de sorte qu’il ne peut pas remettre les pendules à l’heure lui-même) critique de la Russie et de tous les autres médias mondiaux échappant au contrôle des ploutocraties de New York et de Londres. Et il est certainement vrai que Orwell, dont la haine et la peur du communisme étaient très réelles, a servi avant sa mort comme informateur au MI-5, la sécurité intérieure britannique.

Mais ce n’est pas l’Union soviétique, les simulacres de procès de Staline ou ses expériences avec le groupe trotskiste POUM à Barcelone et en Catalogne pendant la guerre civile espagnole qui ont « fait de Orwell Orwell », comme le dit le récit de sagesse conventionnelle anglo-américain. C’est sa haine viscérale de l’Empire britannique – aggravée pendant la Seconde Guerre Mondiale par son travail pour la BBC – qu’il a finalement abandonnée par dégoût.

Et ce sont ses expériences à la BBC qui ont donné à Orwell le modèle de son inoubliable Ministère de la Vérité dans son grand classique « 1984 ».

George Orwell avait travaillé dans l’un des plus grands centres mondiaux de Fake News. Et il le savait.

Plus profondément, le grand secret de la vie de George Orwell se cache à la vue de tous depuis sa mort, il y a 70 ans. Orwell est devenu un tortionnaire sadique au service de l’Empire britannique pendant ses années en Birmanie, le Myanmar moderne. Et en tant qu’homme fondamentalement décent, il était tellement dégoûté par ce qu’il avait fait qu’il a passé le reste de sa vie non seulement à expier, mais aussi à se suicider lentement et délibérément avant de mourir prématurément, le cœur brisé, alors qu’il avait encore la quarantaine.

La première percée importante dans cette réévaluation fondamentale de Orwell provient de l’un des meilleurs livres sur lui. « Finding George Orwell in Burma » a été publié en 2005 et écrit par « Emma Larkin », pseudonyme d’une journaliste américaine exceptionnelle en Asie dont je soupçonne depuis longtemps l’identité d’être un vieil ami et un collègue profondément respecté, et dont je respecte l’anonymat.

« Larkin » a pris la peine de beaucoup voyager en Birmanie pendant la dictature militaire répressive et ses superbes recherches révèlent des vérités cruciales sur Orwell. D’après ses propres écrits et son roman profondément autobiographique « Burmese Days », Orwell détestait tout son temps en tant que policier colonial britannique en Birmanie, le Myanmar moderne. L’impression qu’il donne systématiquement dans ce roman et dans son essai classique « Shooting an Elephant » est celle d’un homme amèrement solitaire, aliéné, profondément malheureux, méprisé et même détesté par ses collègues colonialistes britanniques dans toute la société et d’un ridicule échec dans son travail.

Ce n’est cependant pas la réalité que « Larkin » a découverte. Tous les témoins survivants s’accordent à dire que Orwell – Eric Blair comme il était alors encore – est resté très estimé pendant ses années de service dans la police coloniale. C’était un officier supérieur et efficace. En effet, c’est précisément sa connaissance du crime, du vice, du meurtre et des dessous de la société humaine pendant son service de police colonial, alors qu’il avait encore la vingtaine, qui lui a donné l’intelligence de la rue, l’expérience et l’autorité morale pour voir à travers tous les innombrables mensonges de la droite et de la gauche, des capitalistes américains et des impérialistes britanniques ainsi que des totalitaires européens pour le reste de sa vie.

La deuxième révélation qui permet de comprendre ce que Orwell a dû faire au cours de ces années provient d’une des scènes les plus célèbres et les plus horribles de « 1984 ». En effet, presque rien, même dans les mémoires des survivants des camps de la mort nazis, ne ressemble à cette scène : C’est la scène où « O’Brien », l’officier de police secrète, torture le « héros » (si on peut l’appeler ainsi) Winston Smith en l’enfermant le visage dans une cage dans laquelle un rat affamé est prêt à bondir et à le dévorer si on l’ouvre.

Je me souviens avoir pensé, lorsque j’ai été exposé pour la première fois au pouvoir de « 1984 » dans mon excellente école d’Irlande du Nord : « Quel genre d’esprit pourrait inventer quelque chose d’aussi horrible que cela ?) La réponse était si évidente que, comme tout le monde, je l’ai complètement ratée.

Orwell n’a pas « inventé » ou « proposé » cette idée comme un dispositif d’intrigue fictif : Il s’agissait simplement d’une technique d’interrogatoire de routine utilisée par la police coloniale britannique en Birmanie, le Myanmar moderne. Orwell n’a jamais « brillamment » inventé une technique de torture aussi diabolique qu’un dispositif littéraire. Il n’a pas eu besoin de l’imaginer. Il l’utilisait couramment pour lui-même et ses collègues. C’est ainsi et pour cette raison que l’Empire britannique a si bien fonctionné pendant si longtemps. Ils savaient ce qu’ils faisaient. Et ce qu’ils faisaient n’était pas du tout agréable.

Une dernière étape de mon illumination sur Orwell, dont j’ai vénéré les écrits toute ma vie – et je le fais encore – a été fournie par notre fille aînée, d’une brillance alarmante, il y a environ dix ans, lorsqu’elle a elle aussi reçu « 1984 » à lire dans le cadre de son programme scolaire. En discutant avec elle un jour, j’ai fait une remarque évidente et fortuite : Orwell était dans le roman sous le nom de Winston Smith.

Mon adolescente élevée aux États-Unis m’a alors naturellement corrigé. « Non, papa », dit-elle. « Orwell n’est pas Winston, ou il n’est pas seulement Winston. C’est aussi O’Brien. O’Brien aime bien Winston. Il ne veut pas le torturer. Il l’admire même. Mais il le fait parce que c’est son devoir. »

Elle avait raison, bien sûr.

Mais comment Orwell, le grand ennemi de la tyrannie, du mensonge et de la torture, a-t-il pu s’identifier et comprendre aussi bien le tortionnaire ? C’est parce qu’il en avait lui-même été un.

Le grand livre de »Emma Larkin » fait ressortir que Orwell, en tant que haut fonctionnaire de la police coloniale dans les années 20, a été une figure de proue dans la guerre impitoyable menée par les autorités impériales britanniques contre les cartels criminels de la drogue et du trafic d’êtres humains, tout aussi vicieux et impitoyables que ceux de l’Ukraine, de la Colombie et du Mexique modernes d’aujourd’hui. C’était une « guerre contre le terrorisme » où tout et n’importe quoi était permis pour « faire le travail ».

Le jeune Eric Blair était tellement dégoûté par cette expérience qu’à son retour, il a abandonné le style de vie respectable de la classe moyenne qu’il avait toujours apprécié et est devenu, non seulement un socialiste idéaliste comme beaucoup le faisaient à l’époque, mais aussi un clochard sans le sou et affamé. Il a même abandonné son nom et son identité même. Il a subi un effondrement radical de sa personnalité : Il a tué Eric Blair. Il est devenu George Orwell.

Le célèbre livre de Orwell « Dans la dèche à Paris et à Londres » témoigne de la façon dont il s’est littéralement torturé et humilié au cours de ces premières années de son retour de Birmanie. Et pour le reste de sa vie.

Il mangeait misérablement mal, était maigre et ravagé par la tuberculose et d’autres problèmes de santé, fumait beaucoup et se privait de tout soin médical décent. Son apparence a toujours été abominable. Son ami, l’écrivain Malcolm Muggeridge, spéculait sur le fait que Orwell voulait devenir lui-même la caricature d’un clochard.

La vérité est clairement que Orwell ne s’est jamais pardonné ce qu’il a fait en tant que jeune agent de l’empire en Birmanie. Même sa décision littéralement suicidaire d’aller dans le coin le plus primitif, froid, humide et pauvre de la création dans une île isolée au large de l’Écosse pour finir « 1984 » en isolement avant de mourir était conforme aux punitions impitoyables qu’il s’était infligé toute sa vie depuis qu’il avait quitté la Birmanie.

La conclusion est claire : malgré l’intensité des expériences de George Orwell en Espagne, sa passion pour la vérité et l’intégrité, sa haine de l’abus de pouvoir n’a pas trouvé son origine dans ses expériences de la guerre civile espagnole. Elles découlaient toutes directement de ses propres actions en tant qu’agent de l’Empire britannique en Birmanie dans les années 1920 : Tout comme sa création du ministère de la vérité découle directement de son expérience de travail dans le ventre de la bête de la BBC au début des années 1940.

George Orwell a passé plus de 20 ans à se suicider lentement à cause des terribles crimes qu’il a commis en tant que tortionnaire pour l’Empire britannique en Birmanie. Nous ne pouvons donc avoir aucun doute sur l’horreur et le dégoût qu’il éprouverait face à ce que la CIA a fait sous le président George W. Bush dans sa « guerre mondiale contre la terreur ». De plus, Orwell identifierait immédiatement et sans hésitation les vraies fausses nouvelles qui circulent aujourd’hui à New York, Atlanta, Washington et Londres, tout comme il l’a fait dans les années 1930 et 1940.

Récupérons donc et embrassons le vrai George Orwell : La cause des combats visant à empêcher une troisième guerre mondiale en dépend.

source : https://www.strategic-culture.org

traduction Aube Digitale

00:50 Publié dans Histoire, Littérature | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : george orwell, lettres, lettres anglaises, littérature, littérature anglaise |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

Le 25 novembre 1970, le célèbre écrivain japonais Mishima Yukio se donnait la mort. Il protestait de la passivité de ses compatriotes. Il incitait par cet acte terrible à réveiller le vieil esprit nippon. Avant de commettre le seppuku rituel, il s’adressa aux unités d’auto-défense réunies à sa demande.

Les éditions Ars Magna viennent de traduire et de publier la dernière allocution du fondateur de la Société du Bouclier, l’organisation paramilitaire chargée de redresser l’Empire du Soleil Levant. Cet « appel aux armes » est précédé par une belle introduction de Georges Feltin-Tracol. C’est d’ailleurs la première fois que le public francophone dispose de cette intervention historique et tragique.

Mishima Yukio dénonce avec force « le Japon d’après-guerre [qui] s’est vautré dans la prospérité économique, il a oublié les fondamentaux d’une nation, perdu son esprit national, négligé ce qui est essentiel dans la poursuite de bagatelles, s’est engagé dans l’improvisé et l’hypocrisie et a perdu son âme. C’est ce que nous avons pu voir (p. 20) ». Il souhaite que la Jieitai (les forces d’auto-défense) « renoue avec l’origine des fondements de la force armée japonaise et devienne une authentique armée nationale grâce à une réforme constitutionnelle (p. 21) ». Il s’agit pour lui de réviser l’article 9 de la Constitution de 1946 qui interdit au Japon de déclarer la guerre. Mishima a raison d’avancer « que légalement et théoriquement, l’existence même du Jieitai est contraire à la Constitution d’après-guerre et que la défense nationale, comme composant fondamental d’une nation, est embrouillée par des interprétations juridiques pratiques afin d’assumer le rôle de la force armée sans employer le nom de force armée (p. 20) ».

Par-delà le rôle moteur de l’armée, Mishima Yukio défend le rétablissement de la pleine souveraineté de Tokyo. Or, il sait que son pays sorti des ruines de l’après-guerre est une colonie de l’Occident anglo-saxon. « Le soi-disant contrôle par le pouvoir civil des militaires anglais et américains est uniquement un contrôle financier (p. 25). » Il dénonce que l’île méridionale d’Okinawa soit encore sous la tutelle de Washington. Il ignore que les États-Unis la rétrocéderont au Japon en 1972. Il s’offusque que le Japon signe le traité de non-prolifération nucléaire et renonce ainsi à la détention d’une force de frappe atomique. Clairvoyant, il prévient que la soumission du Jieitai aux vainqueurs de 1945 en fera, « comme les gauchistes l’ont remarqué, une force mercenaire de l’Amérique pour toujours (p. 27) ».

Par-delà le rôle moteur de l’armée, Mishima Yukio défend le rétablissement de la pleine souveraineté de Tokyo. Or, il sait que son pays sorti des ruines de l’après-guerre est une colonie de l’Occident anglo-saxon. « Le soi-disant contrôle par le pouvoir civil des militaires anglais et américains est uniquement un contrôle financier (p. 25). » Il dénonce que l’île méridionale d’Okinawa soit encore sous la tutelle de Washington. Il ignore que les États-Unis la rétrocéderont au Japon en 1972. Il s’offusque que le Japon signe le traité de non-prolifération nucléaire et renonce ainsi à la détention d’une force de frappe atomique. Clairvoyant, il prévient que la soumission du Jieitai aux vainqueurs de 1945 en fera, « comme les gauchistes l’ont remarqué, une force mercenaire de l’Amérique pour toujours (p. 27) ».

Si, le 25 novembre 1970, Mishima Yukio demande en vain aux forces japonaises de renverser le régime parlementaire, il invite surtout les Japonais à retrouver le sens du sacrifice. Il désavoue tout « patriotisme constitutionnel ». Il se demande vraiment : « Y a-t-il quelqu‘un qui veut mourir en se sacrifiant pour la Constitution qui a privé le Japon de sa colonne vertébrale ? (p. 27) » Il lance un vrai défi à la société moderne japonaise : « Rendons au Japon son visage authentique et mourons pour lui (p. 27). » Plus que réussir un coup d’État, Mishima Yukio rappelle plutôt aux troupes que « la signification originale et fondatrice de l’armée du Japon ne consistait en rien d’autre que la “ protection de l’histoire, de la culture et des traditions du Japon centrées sur la monarchie ” (p. 22) ».

Rétif aux actes valeureux et pétri de préjugés démocratiques, l’auditoire militaire de Mishima Yukio s’irrite de l’action sublime de l’écrivain qui met alors fin à ses jours dans une mise en scène traditionnelle héroïque. Bien qu’encore aujourd’hui sous-estimée et mal jugée, la tentative de putsch de Mishima Yukio continue à secouer l’âme profonde des Japonais les plus patriotes. Son sacrifice sublime et celui des membres du Tatenokai n’ont pas été inutiles.

Bastien Valorgues

• Mishima Yukio, Un appel aux armes. Le discours final de Mishima Yukio, Ars Magna, coll. « Les Ultras », 2021, 32 p. 15 €.

00:31 Publié dans Littérature, Livre, Livre | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : japon, mishima, yukio mishima, lettres, lettres japonaises, littérature, littérature japonaise, livre |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

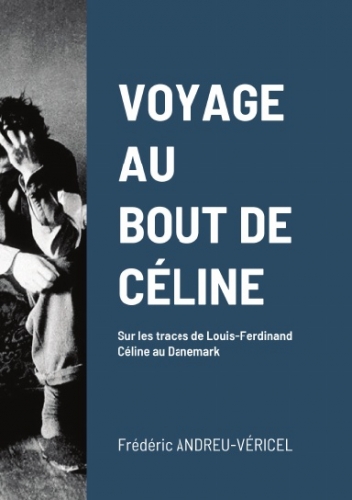

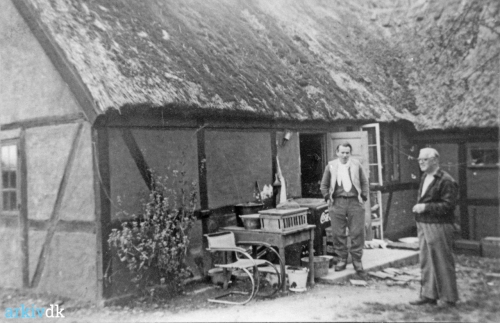

Le couple inégal ralentit le pas. Il était seul devant la forêt aux portes fermées pour eux. Je dis "inégal" car l'un d'entre eux, le plus jeune, savait des choses que le plus vieux ignorait totalement. La preuve de cet aveuglement, de ce rejet obstiné de l'invisible, ce sont ces appareils de mesure qu'il portait en permanence sur lui et qui lui donnait une allure de scaphandrier. À la campagne, ces appareils miniaturisés, micro-ordinateur, caméra avec pluviomètre intégré, entre autres prothèses, étaient le pendant de ces panneaux de circulation et autres passages piétons du monde urbain sans lesquels il ne pouvait vivre.

Le couple inégal ralentit le pas. Il était seul devant la forêt aux portes fermées pour eux. Je dis "inégal" car l'un d'entre eux, le plus jeune, savait des choses que le plus vieux ignorait totalement. La preuve de cet aveuglement, de ce rejet obstiné de l'invisible, ce sont ces appareils de mesure qu'il portait en permanence sur lui et qui lui donnait une allure de scaphandrier. À la campagne, ces appareils miniaturisés, micro-ordinateur, caméra avec pluviomètre intégré, entre autres prothèses, étaient le pendant de ces panneaux de circulation et autres passages piétons du monde urbain sans lesquels il ne pouvait vivre.

00:05 Publié dans Littérature, Livre, Livre | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : frédéric andreu, livre, littérature, lettres, lettres françaises, littérature française, forêt |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

Je remercie Bernard Baritaud et ses collaborateurs du CRAM (Centre de réflexion sur les auteurs méconnus) de m’avoir accueilli dans le numéro 16 de leur revue. Je leur dois bien une recension de La Corne de Brume (livraison d’avril 2020). On y trouve notamment des textes de Nino Frank (1904 – 1988) exaltant les beautés de Milan, Gênes et Venise, en une sorte de périple stendhalien d’où émane « une poésie délicate et plaisante ». Ce ne sont pas exclusivement des écrivains oubliés qu’évoque cette intéressante publication. On y parle aussi d’un fait d’armes que l’Histoire n’a pas retenu et qui a pour décor la Guyane en 1963. Le célèbre Max Jacob s’y invite à la faveur de la Sainte-Hermandade, « version théâtralisée d’un de ces poèmes en prose drolatiques du Carnet à dés (1917) ».

Autant ce recueil de Max Jacob est « légitimement le plus connu », autant Jean Reverzy et son roman Le Passage sont imméritoirement écartés par la postérité littéraire. Il s’agit pourtant d’un auteur qui partage avec Céline son métier initial de médecin des pauvres et son évolution vers un pessimisme décrivant « le lent travail de la vie, cet effritement invisible et ininterrompu ». Un rapprochement est aussi esquissé entre Le Passage de Reverzy et L’Étranger de Camus : « la mer, les hommes simples, une réflexion sur la vie, cet étrange cadeau empoisonné par la mort » et un personnage final d’aumônier « dépeint comme un intrus ».

Autant ce recueil de Max Jacob est « légitimement le plus connu », autant Jean Reverzy et son roman Le Passage sont imméritoirement écartés par la postérité littéraire. Il s’agit pourtant d’un auteur qui partage avec Céline son métier initial de médecin des pauvres et son évolution vers un pessimisme décrivant « le lent travail de la vie, cet effritement invisible et ininterrompu ». Un rapprochement est aussi esquissé entre Le Passage de Reverzy et L’Étranger de Camus : « la mer, les hommes simples, une réflexion sur la vie, cet étrange cadeau empoisonné par la mort » et un personnage final d’aumônier « dépeint comme un intrus ».

L’actualité éditoriale n’est pas absente et l’un des rédacteurs, Henri Cambon, souligne la récente parution des Lettres d’Indochine et de France de Georges Pancol (L’Harmattan, 2019). Avant de mourir au front en 1915 et de rejoindre les rangs de la « génération perdue », à laquelle appartiennent aussi Péguy et Alain-Fournier, Pancol fait un séjour dans le Tonkin qui lui inspire « certains jugements désobligeants » sur les Asiatiques. C’est le regard d’« un jeune Européen qui ne remet guère en cause le fait colonial ». C’est un « témoignage » dont la « valeur historique » est indéniable, même si « on se serait attendu » de la part de l’auteur « à une plus grande ouverture d’esprit devant les richesses humaines et culturelles de ces pays dans lesquels il a été plongé ».

Bernard Baritaud se souvient de sa jeunesse antillaise et son pittoresque récit autobiographique est couronné par un magnifique poème dont voici un extrait :

« Notre-Dame de la Guadeloupe

Tu portes un nom de vierge espagnole

Et de sierra

Notre-Dame de la Guadeloupe

Tu es un nom d’os et de sang.

Je ne t’ai pas vue mais je te connais et je sais

Que tu es noire, vierge d’ivoire

Drapée de pierre. »

C’est encore Henri Cambon qui ravive le souvenir de Jean Rogissart (1894 – 1961). Certes, l’auteur de la saga des Mamert a fait encore récemment l’objet d’une étude universitaire (à Dijon, en 2014). Mais cette fresque familiale reste relativement méconnue alors qu’elle s’inscrit dans un majestueux courant littéraire français dont Georges Duhamel et Roger Martin du Gard sont d’illustres représentants.

C’est encore Henri Cambon qui ravive le souvenir de Jean Rogissart (1894 – 1961). Certes, l’auteur de la saga des Mamert a fait encore récemment l’objet d’une étude universitaire (à Dijon, en 2014). Mais cette fresque familiale reste relativement méconnue alors qu’elle s’inscrit dans un majestueux courant littéraire français dont Georges Duhamel et Roger Martin du Gard sont d’illustres représentants.

L’histoire de la famille Mamert commence, dans le premier des sept volumes, par l’installation des industriels, de leurs usines et de leurs machines dans cette Vallée de la Meuse « qui remonte en méandres serrés et encaissés vers Givet, et au-delà la Belgique ». Jean Rogissart est né dans cette région, non loin de Charleville. Mais la cité de Rimbaud, ainsi que sa voisine Sedan, élisent leurs premiers députés socialistes aux alentours de 1900, tandis que « des courants anarchistes et libertaires » dénoncent déjà « certaines manœuvres politiciennes » et des dérives « bourgeoisies survenant même parmi les forces de gauche ».

Les membres de la famille Mamert se divisent parfois sur la question du choix politique, mais tout au long des quatre générations dont Jean Rogissart déroule le parcours, revient le problème « de l’engagement face à ce qui pèse sur l’homme – injustices sociales, guerres », l’obsédante interrogation sur l’attitude qu’il faut opposer aux malheurs qui accablent l’humanité. Le sixième tome intitulé L’Orage de la Saint-Jean amène le lecteur au seuil de la Seconde Guerre mondiale et le déclenchement du conflit est évoqué dans un style à al fois sobre et puissant. « Vers minuit on frappe à notre porte; on frappait à toutes les portes. C’était lugubre ces chocs sourds dans le silence. Accompagné du secrétaire de mairie, le garde-champêtre avertissait les habitants. Par ordre supérieur nous devions quitter le village avant cinq heures du matin. Tous les ponts de la Meuse sauteraient alors et les retardataires seraient bloqués sur la rive droite. »

On attribue à Jean-Baptiste Clément la création du Temps des Cerises, célèbre chanson qui aurait été inspirée par la Commune de Paris. Ce titre est aussi celui du deuxième volume du cycle romanesque de Jean Rogissart. Jean-Baptiste Clément est de passage dans la contrée mosane et y répand sa conception d’un « socialisme pur » grâce auquel « l’homme rompt ses chaînes millénaires et peut enfin croire en Dieu ». remarquons ici l’intéressant renversement de l’idée marxiste de la religion comme « opium du peuple », dont il faut se débarrasser pour mener à son terme le processus d’émancipation économique et sociale. Pour Rogissart, au contraire, il faut d’abord vaincre l’esclavage ouvrier qui pèse sur l’humanité comme une sorte de fatalité originelle, un obscur destin dont la volonté militante doit s’affranchir pour pouvoir accéder à la lumière de la Providence divine. Destin – Volonté – Providence : c’est l’une des « grandes triades » analysées par René Guénon.

On attribue à Jean-Baptiste Clément la création du Temps des Cerises, célèbre chanson qui aurait été inspirée par la Commune de Paris. Ce titre est aussi celui du deuxième volume du cycle romanesque de Jean Rogissart. Jean-Baptiste Clément est de passage dans la contrée mosane et y répand sa conception d’un « socialisme pur » grâce auquel « l’homme rompt ses chaînes millénaires et peut enfin croire en Dieu ». remarquons ici l’intéressant renversement de l’idée marxiste de la religion comme « opium du peuple », dont il faut se débarrasser pour mener à son terme le processus d’émancipation économique et sociale. Pour Rogissart, au contraire, il faut d’abord vaincre l’esclavage ouvrier qui pèse sur l’humanité comme une sorte de fatalité originelle, un obscur destin dont la volonté militante doit s’affranchir pour pouvoir accéder à la lumière de la Providence divine. Destin – Volonté – Providence : c’est l’une des « grandes triades » analysées par René Guénon.

Tirer de l’oubli des écrivains talentueux alors que les jurys et les media glorifient beaucoup de plumitifs médiocres : tel est l’immense mérite du CRAM et de sa belle revue La Corne de Brume.

Daniel Cologne.

00:05 Publié dans Littérature | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : littérature, lettres, lettres françaises, littérature française, jean rogissart, jean reverzy |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

Björn Roose

Wie mijn boekbesprekingen volgt, zal zich misschien herinneren dat ik er eind augustus 2019 (het lijkt alweer een eeuwigheid geleden) een publiceerde over een ander werk van Michail Boelgakov, Zoja’s appartement . Ik verwijs graag naar die bespreking voor wie iets meer wil vernemen over de achtergrond van Boelgakov, maar begin de bespreking van Hondehart even graag met de conclusie van die vorige bespreking: “Voor de duidelijkheid: ik hoor niet tot de kaste van aan wal staande stuurlui. Het was ongetwijfeld in de Sovjet-Unie net zomin gemakkelijk voor je mening uit te komen als in nationaal-socialistisch Duitsland en er zal ook dáár weinig opdeling te maken geweest zijn tussen zwart en wit (een poging die in deze tijden uiteraard wél blijvend ondernomen wordt). Maar het is zonde gezien het talent dat Boelgakov in andere werken getoond heeft. Ik heb jaren geleden genoten van zijn Hondenhart (sic), dat in 1925 werd verboden en dat een heel erg duidelijke kritiek op het regime vormde. Of zoals de Sovjet-krant Izvestia op 15 september 1929 schreef: "Zijn talent is overduidelijk, maar zo is ook het reactionair sociaal karakter van zijn werk". Ik heb zijn voornaamste werk De Meester en Margarita nog niet gelezen - het boek waaraan hij tussen 1928 en het jaar van zijn overlijden, 1940, werkte -, maar ook dát zou een knappe parodie zijn op Stalin en het leven in de Sovjet-Unie. Dat maakt helaas dingen als deze tweede versie van Zoja's appartement én de kniebuigingen van Boelgakov voor Stalin en het regime alleen maar spijtiger.”

Wie mijn boekbesprekingen volgt, zal zich misschien herinneren dat ik er eind augustus 2019 (het lijkt alweer een eeuwigheid geleden) een publiceerde over een ander werk van Michail Boelgakov, Zoja’s appartement . Ik verwijs graag naar die bespreking voor wie iets meer wil vernemen over de achtergrond van Boelgakov, maar begin de bespreking van Hondehart even graag met de conclusie van die vorige bespreking: “Voor de duidelijkheid: ik hoor niet tot de kaste van aan wal staande stuurlui. Het was ongetwijfeld in de Sovjet-Unie net zomin gemakkelijk voor je mening uit te komen als in nationaal-socialistisch Duitsland en er zal ook dáár weinig opdeling te maken geweest zijn tussen zwart en wit (een poging die in deze tijden uiteraard wél blijvend ondernomen wordt). Maar het is zonde gezien het talent dat Boelgakov in andere werken getoond heeft. Ik heb jaren geleden genoten van zijn Hondenhart (sic), dat in 1925 werd verboden en dat een heel erg duidelijke kritiek op het regime vormde. Of zoals de Sovjet-krant Izvestia op 15 september 1929 schreef: "Zijn talent is overduidelijk, maar zo is ook het reactionair sociaal karakter van zijn werk". Ik heb zijn voornaamste werk De Meester en Margarita nog niet gelezen - het boek waaraan hij tussen 1928 en het jaar van zijn overlijden, 1940, werkte -, maar ook dát zou een knappe parodie zijn op Stalin en het leven in de Sovjet-Unie. Dat maakt helaas dingen als deze tweede versie van Zoja's appartement én de kniebuigingen van Boelgakov voor Stalin en het regime alleen maar spijtiger.” Zo, om de clue te weten te komen, moet u het boekje al niet meer lezen, maar u zal allicht ook niet meer opkijken van het feit dat dit werk in de Sovjet-Unie niet mocht gepubliceerd worden (helaas dook het in het Westen ook pas op toen hij al overleden was, net zoals De Meester en Margarita trouwens). Een duidelijker kritiek op het idee van de maakbare mens is nauwelijks denkbaar. En daarmee vormt het boek eigenlijk net zo goed een aanklacht tegen het nationaal-socialisme of tegen volstrekt waanzinnige moderne vormen van utopieën genre de veelbesproken Great Reset. Je kan de mens wel uit het vuilnis halen, maar niet het vuilnis uit de mens. Je kan de mens proberen aan te passen aan je communistische, nationaal-socialistische, post-modernistische ideetjes, maar de mens zal altijd een mens blijven en zelfs als er geen externe factoren meespelen – iets waar mensen als Klaus Schwab vurig naar streven door de hele wereld mee te slepen in hun waanzin –, zal je utopie aan dat simpele feit ten onder gaan.

Zo, om de clue te weten te komen, moet u het boekje al niet meer lezen, maar u zal allicht ook niet meer opkijken van het feit dat dit werk in de Sovjet-Unie niet mocht gepubliceerd worden (helaas dook het in het Westen ook pas op toen hij al overleden was, net zoals De Meester en Margarita trouwens). Een duidelijker kritiek op het idee van de maakbare mens is nauwelijks denkbaar. En daarmee vormt het boek eigenlijk net zo goed een aanklacht tegen het nationaal-socialisme of tegen volstrekt waanzinnige moderne vormen van utopieën genre de veelbesproken Great Reset. Je kan de mens wel uit het vuilnis halen, maar niet het vuilnis uit de mens. Je kan de mens proberen aan te passen aan je communistische, nationaal-socialistische, post-modernistische ideetjes, maar de mens zal altijd een mens blijven en zelfs als er geen externe factoren meespelen – iets waar mensen als Klaus Schwab vurig naar streven door de hele wereld mee te slepen in hun waanzin –, zal je utopie aan dat simpele feit ten onder gaan. Gevolgd door een hoofdstuk waarin het beest de operatiekamer ingelokt wordt en de chirurg er behalve wat worst ook een stukje filosofie tegenaan gooit als hij door zijn assistent gevraagd wordt hoe hij de hond heeft meegekregen: “Kwestie van aanhalen. Dat is de enige manier waarop je wat bereikt bij levende wezens. Met terreur kom je nergens, ongeacht het ontwikkelingspeil van een dier.” Waarna dat dier ook te weten komt dat hij dan wel nieuwe testikels heeft gekregen, maar ook ontmand is: “‘Pas op, jij, of ik maak je af! Weest u maar niet bang, hij bijt niet.’ ‘Bijt ik niet?’ vroeg de hond zich verbaasd af.” En waarin we kennis maken met het “huisbestuur”, de club van communistische zeloten die ervoor moeten zorgen dat Preobrazjenski datgene doet wat ook in Dokter Zjivago van Boris Pasternak een belangrijk thema is: zijn appartement delen met alsmaar meer mensen (“inwonerstalverdichting”, zoals dat in Hondehart genoemd wordt). Op het einde van dat hoofdstuk krijgen we deze heerlijke dialoog, een dialoog die ik heden ten dage eigenlijk niet genoeg hoor. Een dialoog waarin simpelweg gezegd wordt dat iemand iets ook niet kan willen omdat hij het gewoon niet wil:

Gevolgd door een hoofdstuk waarin het beest de operatiekamer ingelokt wordt en de chirurg er behalve wat worst ook een stukje filosofie tegenaan gooit als hij door zijn assistent gevraagd wordt hoe hij de hond heeft meegekregen: “Kwestie van aanhalen. Dat is de enige manier waarop je wat bereikt bij levende wezens. Met terreur kom je nergens, ongeacht het ontwikkelingspeil van een dier.” Waarna dat dier ook te weten komt dat hij dan wel nieuwe testikels heeft gekregen, maar ook ontmand is: “‘Pas op, jij, of ik maak je af! Weest u maar niet bang, hij bijt niet.’ ‘Bijt ik niet?’ vroeg de hond zich verbaasd af.” En waarin we kennis maken met het “huisbestuur”, de club van communistische zeloten die ervoor moeten zorgen dat Preobrazjenski datgene doet wat ook in Dokter Zjivago van Boris Pasternak een belangrijk thema is: zijn appartement delen met alsmaar meer mensen (“inwonerstalverdichting”, zoals dat in Hondehart genoemd wordt). Op het einde van dat hoofdstuk krijgen we deze heerlijke dialoog, een dialoog die ik heden ten dage eigenlijk niet genoeg hoor. Een dialoog waarin simpelweg gezegd wordt dat iemand iets ook niet kan willen omdat hij het gewoon niet wil: Soit, verder naar het volgende hoofdstuk. Daarin begint de langzame transformatie van hond tot mens (of van mens tot de nationaal-socialistische versie van Nietzsches Übermensch, of van koelak tot communist) en leert het beest dat het goed is geketend te zijn. Liever een dikke hond aan de ketting dan een magere wolf in het bos. “De volgende dag kreeg de hond een brede, glimmende halsband om. Toen hij zich in de spiegel bekeek, was hij het eerste moment knap uit zijn humeur. Met de staart tussen de poten trok hij zich in de badkamer terug, zich afvragend hoe hij het ding zou kunnen doorschuren tegen een kist of een hutkoffer. Maar algauw drong het tot hem door dat hij gewoon een idioot was. Zina nam hem aan de lijn mee uit wandelen door de Oboechovlaan. De hond liep erbij als een arrestant en brandde van schaamte. Maar eenmaal voorbij de Christuskerk op de Pretsjistenka was hij er al helemaal achter wat een halsband in dit leven betekent. Bezeten afgunst stond te lezen in de ogen van alle honden die hij tegen kwam en ter hoogte van het Dodenpad blafte een uit zijn krachten gegroeide straatkeffer hem uit voor ‘rijkeluisflikker’ en ‘zespoot’. Toen zij de tramrails overhuppelden keek een agent van milietsie tevreden en met respect naar de halsband (…) Zo’n halsband is net een aktentas, grapte de hond in gedachte en wiebelend met zijn achterwerk schreed hij op naar de bel-etage als een heer van stand.” Of, zoals het in het volgende hoofdstuk al heet: “Maak je zelf maar niets wijs, jij zoekt heus de vrijheid niet meer op, treurde de hond snuivend. Die ben je ontwend. Ik ben een voornaam hondedier, een intelligent wezen, ik heb een beter bestaan leren kennen. En wat is de vrijheid helemaal? Rook, een fictie, een drogbeeld, anders niet … Een koortsdroom van die rampzalige democraten …”

Soit, verder naar het volgende hoofdstuk. Daarin begint de langzame transformatie van hond tot mens (of van mens tot de nationaal-socialistische versie van Nietzsches Übermensch, of van koelak tot communist) en leert het beest dat het goed is geketend te zijn. Liever een dikke hond aan de ketting dan een magere wolf in het bos. “De volgende dag kreeg de hond een brede, glimmende halsband om. Toen hij zich in de spiegel bekeek, was hij het eerste moment knap uit zijn humeur. Met de staart tussen de poten trok hij zich in de badkamer terug, zich afvragend hoe hij het ding zou kunnen doorschuren tegen een kist of een hutkoffer. Maar algauw drong het tot hem door dat hij gewoon een idioot was. Zina nam hem aan de lijn mee uit wandelen door de Oboechovlaan. De hond liep erbij als een arrestant en brandde van schaamte. Maar eenmaal voorbij de Christuskerk op de Pretsjistenka was hij er al helemaal achter wat een halsband in dit leven betekent. Bezeten afgunst stond te lezen in de ogen van alle honden die hij tegen kwam en ter hoogte van het Dodenpad blafte een uit zijn krachten gegroeide straatkeffer hem uit voor ‘rijkeluisflikker’ en ‘zespoot’. Toen zij de tramrails overhuppelden keek een agent van milietsie tevreden en met respect naar de halsband (…) Zo’n halsband is net een aktentas, grapte de hond in gedachte en wiebelend met zijn achterwerk schreed hij op naar de bel-etage als een heer van stand.” Of, zoals het in het volgende hoofdstuk al heet: “Maak je zelf maar niets wijs, jij zoekt heus de vrijheid niet meer op, treurde de hond snuivend. Die ben je ontwend. Ik ben een voornaam hondedier, een intelligent wezen, ik heb een beter bestaan leren kennen. En wat is de vrijheid helemaal? Rook, een fictie, een drogbeeld, anders niet … Een koortsdroom van die rampzalige democraten …”

00:01 Publié dans Littérature, Livre, Livre | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : communisme, soviétisme, russie, mikhail bulgakov, lettres, lettres russes, littérature, littérature russe, livre |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

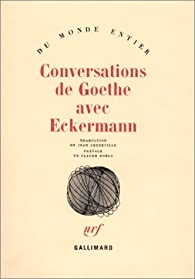

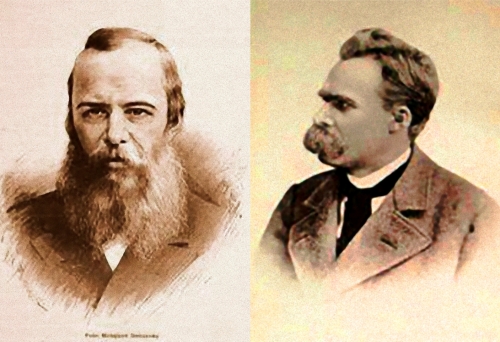

Goethe et la dévitalisation des Européens

par Nicolas Bonnal

Nous avons vu que Goethe pressent le grand déclin du monde dans ses Entretiens avec Eckermann. Concrètement nous allons rappeler qu’il pressent aussi le déclin physique hommes du continent, lié à son développement industriel. Bien avant Nietzsche ou Carrel, l’auteur de Werther, qui aspirait à un idéal classique européen, pressent cet affaissement. Et comme Rousseau, mais à sa manière, Goethe rejette le monde occidental et sa civilisation préfabriquée. Nous sommes en 1828 :

« Du reste, nous autres Européens, tout ce qui nous entoure est, plus ou moins, parfaitement mauvais ; toutes les relations sont beaucoup trop artificielles, trop compliquées ; notre nourriture, notre manière de vivre, tout est contre la vraie nature ; dans notre commerce social, il n’y a ni vraie affection, ni bienveillance. Tout le monde est plein de finesse, de politesse, mais personne n’a le courage d’être naïf, simple et sincère ; aussi un être honnête, dont la manière de penser et d’agir est conforme à la nature, se trouve dans une très-mauvaise situation. On souhaiterait souvent d’être né dans les îles de la mer du Sud, chez les hommes que l’on appelle sauvages, pour sentir un peu une fois la vraie nature humaine, sans arrière-goût de fausseté. »

D’un coup le grand homme olympien se sent neurasthénique :

D’un coup le grand homme olympien se sent neurasthénique :

« Quand, dans un mauvais jour, on se pénètre bien de la misère de notre temps, il semble que le monde soit mûr pour le jugement dernier. Et le mal s’augmente de génération en génération ! Car ce n’est pas assez que nous ayons à souffrir des péchés de nos pères, nous léguons à nos descendants ceux que nous avons hérites, augmentés de ceux que nous avons ajoutés. »

Mais Eckermann tente de le rasséréner. On n’est qu’au début du dix-neuvième siècle, au sortir des meurtrières guerres napoléoniennes qui ont fait s’effondrer la taille du soldat français (quatre pouces, dira Madison Grant en reprenant les études de Vacher de Lapouge) :

« — J’ai souvent des pensées de ce genre dans l’esprit, dis-je, mais si je viens à voir passer à cheval un régiment de dragons allemands, en considérant la beauté et la force de ces jeunes gens, je me sens un peu consolé et je me dis : l’avenir de l’humanité n’est pas encore si menacé ! »

Car Schmitt dans son grand et beau texte sur le partisan souligne le fondement : il faut garder son caractère tellurique ; c’est en effet la clé pour tromper d’un ennemi surpuissant. A l’heure où nous sommes dévitalisés par les confinements et notre addiction à la technologie, cette leçon est de toute manière bien oubliée.

Goethe fait confiance bien sûr à la solide classe paysanne qui sera exterminée par les guerres mondiales, le communisme puis par la politique agricole commune européenne :

« — Notre population des campagnes, en effet, répondit Goethe, s’est toujours conservée vigoureuse, et il faut espérer que pendant longtemps encore elle sera en état non-seulement de nous fournir de solides cavaliers, mais aussi de nous préserver d’une chute et d’une décadence absolues. Elle est comme un dépôt où viennent sans cesse se refaire et se retremper les forces alanguies de l’humanité. Mais allez dans nos grandes villes, et vous aurez une autre impression. Causez avec un nouveau Diable boiteux, ou liez-vous avec un médecin ayant une clientèle considérable, il vous racontera tout bas des histoires qui vous feront tressaillir en vous montrant de quelles misères, de quelles infirmités souffrent la nature humaine et la société. »

Le coût encore du divin Napoléon ? Eckermann en parle :

Je me rappelle aussi avoir vu sous Napoléon un bataillon d’infanterie française qui était composé uniquement de Parisiens, et c’étaient tous des hommes si petits et si grêles qu’on ne concevait guère ce qu’on voulait faire avec eux à la guerre. »

« Les montagnards écossais du duc de Wellington devaient paraître d’autres héros, dit Goethe. »

« — Je les ai vus à Bruxelles un an avant la bataille de Waterloo. C’étaient en réalité de beaux hommes ! Tous forts, frais, vifs, comme si Dieu lui-même les avait créés les premiers de leur race. — Ils portaient tous leur tête avec tant d’aisance et de bonne humeur, et s’avançaient si légèrement avec leurs vigoureuses cuisses nues, qu’il semblait que pour eux il n’y avait pas eu de péché originel, et que leurs aïeux n’avaient jamais connu les infirmités. »

Tout de même cette époque – le début du dix-neuvième siècle donc - est encore féconde en beaux hommes (voir Custine époustouflé par les russes). Et Goethe se lance dans un beau développement sur le gentleman anglais façon Jane Austen qui alors fascine l’Europe et le monde. On se rappelle du somptueux Wellington de Bondartchuk dans le film Waterloo et on laisse Goethe parler :

« — C’est un fait singulier, dit Goethe. Cela tient-il à la race ou au sol, ou à la liberté de la constitution politique, ou à leur éducation saine, je ne sais, mais il y a dans les Anglais quelque chose que la plupart des autres hommes n’ont pas. Ici, à Weimar, nous n’en voyons qu’une très-petite fraction, et ce ne sont sans doute pas le moins du monde les meilleurs d’entre eux, et cependant comme ce sont tous de beaux hommes, et solides ! Quelque jeunes qu’ils arrivent ici en Allemagne, à dix-sept ans déjà, ils ne se sentent pas hors de chez eux et embarrassés en vivant à l’étranger ; au contraire, leur manière de se présenter et de se conduire dans la société est si remplie d’assurance et si aisée que l’on croirait qu’ils sont partout les maîtres et que le monde entier leur appartient. C’est bien là aussi ce qui plaît à nos femmes, et voilà pourquoi ils font tant de ravages dans le cœur de nos jeunes dames. »

Les âges d’or ou les grands moments n’ont qu’un temps. On ne comparera pas les massacrés des tranchées aux marcheurs de Moscou.

Sources :

Conversations avec Eckermann. 1828 (Wikisource.org).

00:10 Publié dans Littérature | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : goethe, allemagne, nicolas bonnal, 19ème siècle, lettres, lettres allemandes, littérature, littérature allemande |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

Luc-Olivier d’Algange

Baudelaire, Sartre et Joseph de Maistre

Les exégètes et les biographes modernes cèdent excessivement à la suspicion, à la dépréciation, voire à une certaine acrimonie à l'égard des œuvres dont ils traitent et dont ils font à la fois leur fonds de commerce et l'exutoire de leur ressentiment à se voir bornés au rôle secondaire. Alors que le commentaire traditionnel part d'un principe de révérence et de fidélité qui l'incline, par son interprétation, à poursuivre dans la voie ouverte par l'œuvre qu'il distingue et à laquelle il se dévoue, le moderne juge en général plus « gratifiant » de suspecter l'auteur et de trouver la paille dans l'œil de l'œuvre, dont il ignore qu'elle le contemple autant qu'il l'examine. L'exégète suspicieux trace, plus souvent qu'à son tour, son propre portrait, avec sa poutre.

Lorsque Sartre suggère que la lecture baudelairienne de Maistre est sommaire, qu'elle obéit à des raisons subalternes, superficielles, il nous renseigne sur sa propre lecture de Joseph de Maistre, et nous livre, par la même occasion, son autoportrait: « un penseur austère et de mauvaise foi. ». On peut tout reprocher à Joseph de Maistre, sauf bien sûr d'être un penseur « austère ». S'il est une œuvre qui résista au puritanisme sous toutes ses formes, c'est bien celle de Joseph de Maistre: la défiance que les modernes éprouvent à son endroit ne s'explique pas autrement. Adeptes étroits de la vertu et de la terreur, de la morale dépourvue de perspective métaphysique ou surnaturelle, adversaires des esthètes et des dandies (ces ultimes gardiens de la concordance du Vrai et du Beau) les modernes firent de l'austérité et de la mauvaise-foi leurs armes théoriques et pratiques pour exterminer toutes les survivances théologiques, où qu'elles se trouvent.

L'influence de Maistre sur Baudelaire est l'une des plus profondes qu'un penseur exerça jamais sur un poète, à ceci près que l'on ne saurait oublier que Maistre, dans Les Soirées de Saint-Pétersbourg est continûment poète, de même que Baudelaire, dans ses œuvres poétiques et critiques, ses fusées et les notes de Mon cœur mis à nu, ne cessa jamais d'être un métaphysicien avisé. Baudelaire se reconnaît en Maistre autant qu'il lui doit les principes esthétiques et philosophiques principaux de sa méthode. Baudelaire eût sans doute été maistrien sans même avoir à lire Joseph de Maistre, tant il se tient par son goût, et par de mystérieuses et providentielles affinités, au diapason des préférences de Joseph de Maistre. Mais, au sens où Valéry parle de la méthode de Léonard de Vinci, il y a une méthode baudelairienne, et celle-ci doit tout à Joseph de Maistre.