por Adriano Erriguel

Ex: https://culturatransversal.wordpress.com

“Soy un hombre enfermo, soy un hombre rabioso. No soy nada atractivo. Creo que estoy enfermo del hígado. Sin embargo no sé nada de mi enfermedad y tampoco puedo precisar qué es lo que me duele…” Así arrancan las “Memorias del subsuelo”, la obra que en menor número de páginas concentra más contenido filosófico de todas las que escribió Fiodor M. Dostoyevski. Estas páginas vigorosas y dramáticas constituyen la más potente carga de profundidad que desde la literatura se haya lanzado jamás contra los pilares antropológicos del liberalismo moderno: el mito de la felicidad, el mito del interés individual, el mito del progreso.

A través del narrador anónimo de estas memorias Dostoyevski se interna en los meandros del subconsciente para iluminar los aspectos más incoherentes, sórdidos y contradictorios de la naturaleza humana. Y la perorata del “hombre del subsuelo” – este individuo lúgubre, retorcido, quisquilloso y cruel – nos muestra que la ensoñación de un mundo pacificado por la razón universal, por la consciencia moral y por la armonía de los intereses individuales no es más que una hipócrita impostura, un horror aún peor que los horrores que depara la vida real. Porque los dogmas sedantes de la fraternidad universal y el moralismo invasivo del hombre progresista quedan desarmados frente a una pregunta muy simple: ¿Y qué sucede si el hombre, a fin de cuentas, prefiere sufrir?

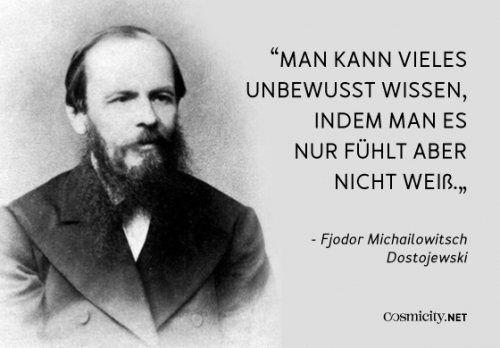

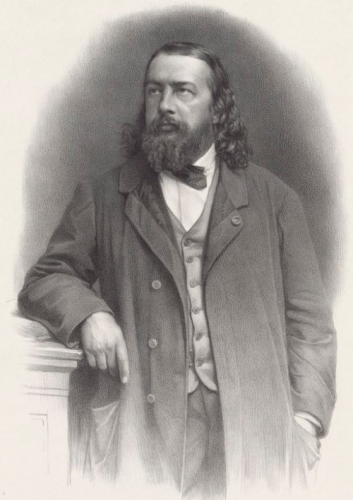

En materia de sufrimiento Fiodor M. Dostoyevski no hablaba de oídas.

En materia de sufrimiento Fiodor M. Dostoyevski no hablaba de oídas.

Más allá de la casa de los muertos

¡Alto! ¡Este es tu dolor! ¡Aquí está! ¡No intentes salir de esta como hacen los muertos vivientes! ¡Sin dolor y sacrificio no tendríamos nada! ¡Te estás perdiendo el momento más grande de tu vida!

TYLOR DURDEN en el film: “El club de la lucha”

Hijo de un médico de hospital, la infancia de Dostoyevski transcurrió en las proximidades de un orfanato, de un manicomio y de un cementerio de criminales. Epiléptico desde los 18 años, a los 28 fue arrestado por formar parte de un grupo de conspiradores y fue sometido a un simulacro de ejecución. Cuatro años de prisión y de trabajos forzados en Siberia arruinaron su salud. Durante gran parte de su vida se vio asediado por las deudas, por la adicción al juego y por sus tendencias depresivas, y hubo además de padecer las muertes de su primera mujer y de dos de sus hijos. Falleció a los 59 años. “Para ser buen escritor es preciso haber sufrido”, dijo hacia el final de su vida. Él se encargó de demostrarlo. Con creces.

¿Un buen escritor? En su caso mejor decir: un gran escritor. Porque el autor ruso es la demostración más rotunda de que escribir bien y ser escritor son cosas diferentes. De hecho, probablemente él escribía mal. Su prosa fluye espasmódica y a borbotones, en tiradas que se disparan en todas direcciones para condensarse de nuevo en un amasijo caótico, al límite de la coherencia. Desde el punto de vista de pura técnica novelista la arquitectura de sus historias es a veces deficiente, la caracterización de sus personajes errática y los recursos dramáticos que emplea discutibles (1). Dicho lo cuál, da igual. Porque lo de Dostoyevski era otra cosa.

Realismo superior. Así definía el autor ruso su arte. Su objetivo no era experimentar con el lenguaje sino dar salida a su cosmovisión. En su escritura no hay lugar para manierismos ni para gorgoritos literarios. Las descripciones del tiempo o de la naturaleza, los cuadros costumbristas o los inventarios de valor sociológico brillan por su ausencia. Toda la acción transcurre en el interior de las personas. Porque ésa es la única realidad que a él le interesa: la oculta y espiritual, y ésta se revela a través de las acciones, las palabras y los pensamientos de sus personajes. Unos personajes casi siempre al límite yque se bañan en una atmósfera alucinada, como si vivieran “en espacios y en tiempos muy diversos de los reales, más consonantes con su existencia espiritual y profunda”. En las novelas de Dostoyevski – dice el filósofo Luigi Pareyson – “todo lo visible se transforma en fantasma y a su vez ese fantasma se convierte en la figura de una realidad superior. La visión de esa realidad superior es tan vigorosa que nos hace olvidar la visión de lo visible”. Nada es lo que parece. Los héroes de Dostoyevski “no trabajan en el sentido literal del término. No tienen ocupaciones, obligaciones o labores, pero van y vienen, se encuentran y entrecruzan, no cesan jamás de hablar (…) ¿Qué hacen? …meditan sobre la tragedia del hombre, descifran el enigma del mundo ¿Quiénes son en realidad? Son ideas personificadas, ideas en movimiento” (2).

¿Qué ideas? Con su largo historial de penalidades a cuestas Dostoyevski bien podría haberse entregado a una literatura dolorista y lastimera, a un mensaje filantrópico y edificante de denuncia social – como toda esa literatura oficial que hoy se cotiza en galardones “a la coherencia personal” o “al compromiso”. Pero el autor ruso era demasiado grande como para caer en bagatelas progresistas. Cuando Dostoyevski volvió de la casa de los muertos – el presidio siberiano a donde fue condenado por las autoridades zaristas – lo hizo convertido en un patriota, en un defensor de la misión universal de Rusia ante una Europa en la que él ya veía el germen de la decadencia. ¿Cómo fue eso posible?

Amor fati – la ley más fecunda de la vida, según Nietzsche. El amor por su destino – dice Stefan Zweig – “impedía a Dostoyevski ver en la adversidad algo diferente a la plenitud, y ver en la desgracia otra cosa que un camino de salvación”. Protestar contra el sufrimiento sería como protestar contra la lluvia. No hay en toda su obra un ápice de exhibicionismo victimista. Ni tampoco de orgullo o vanidad personal. Siempre practicó una impersonalidad activa. Volcó todo su orgullo en aquello que le sobrepasaba: en la idea de su pueblo y en la misión que a éste atribuía. Si bien la preocupación moral es una constante en su obra, no hay en ella rastro alguno de moralina. Porque vivir bien, para él, era “vivir intensamente en el bien y en el mal, incluidas sus formas más violentas y embriagadoras; nunca buscó la regla, sino la plenitud” (3). Siempre a la escucha de su lado oscuro, en perpetuo diálogo con su parte maldita, Dostoyevski es el escritor dionisíaco por excelencia. Odia los términos medios, abomina de todo lo que es moderado, armonioso. Sólo lo extraordinario, lo invisible, lo demoníaco le interesa. Sus obras nos muestran las puertas de salida del mundo burgués. Y la primera puerta se abre desde el subsuelo.

El reaccionario salvaje

Se me ocurre plantear ahora una pregunta ociosa: ¿Qué resultaría mejor? ¿Una felicidad barata o unos sufrimientos elevados?

FIODOR M. DOSTOYEVSKI

Un individuo resentido, cicatero, cruel. Una risotada brutal que procede de la noche de los tiempos. El “hombre del subsuelo” es el primer antihéroe de la historia de la literatura. Con él Dostoyevski comienza a ser Dostoyevski. Décadas antes de Sigmund Freud el autor ruso desciende al sótano del subconsciente y da la palabra a ese hombrecillo oculto, aherrojado en los grilletes de la civilización y del progreso. Un individuo que se revela como un reaccionario salvaje. Y que la emprende contra una de las manías favoritas de la modernidad y del progreso: ¿a qué viene esa obligación de ser, a toda costa, felices? ¿Es eso de verdad lo que queremos?

Un individuo resentido, cicatero, cruel. Una risotada brutal que procede de la noche de los tiempos. El “hombre del subsuelo” es el primer antihéroe de la historia de la literatura. Con él Dostoyevski comienza a ser Dostoyevski. Décadas antes de Sigmund Freud el autor ruso desciende al sótano del subconsciente y da la palabra a ese hombrecillo oculto, aherrojado en los grilletes de la civilización y del progreso. Un individuo que se revela como un reaccionario salvaje. Y que la emprende contra una de las manías favoritas de la modernidad y del progreso: ¿a qué viene esa obligación de ser, a toda costa, felices? ¿Es eso de verdad lo que queremos?

“¿Por qué estamos tan firmemente convencidos – dice el hombre del subsuelo – de que sólo lo que es normal y positivo, de que sólo el bienestar es ventajoso para el hombre? ¿No pudiera ser que el hombre no ame sólo el bienestar, sino también el sufrimiento? Porque ocurre que a veces el hombre ama terrible y apasionadamente el sufrimiento (…) Podrá estar bien o mal, pero la destrucción resulta también a veces algo muy agradable. (…) Yo no defiendo aquí ni el sufrimiento ni el bienestar. Yo defiendo…mi propio capricho”.

¿Qué diría el hombre del subsuelo sobre nuestra época? La felicidad como deber, la euforia como disciplina, el festivismo como religión. He ahí nuestros horizontes insuperables. Ninguna época anterior a la nuestra había convertido la infelicidad en un signo de anormalidad o en un estigma de oprobio. Y sin embargo la depresión es nuestro “mal del siglo”. Dostoyevski ya lo había previsto. Porque él sabía que el hombre “no busca ni la felicidad ni la quietud. Lo que desea es una existencia a su medida, realizarse conforme a su voluntad, abrazar lo irracional y lo absurdo de su naturaleza” (4). Sin embargo Occidente es la única civilización que ha querido eliminar la tragedia de la faz de la tierra. ¿Y luego qué? ¿Para qué nos serviría ese único, universal e imperecedero universo de la razón y de la ciencia, si su único fruto será la grisácea uniformidad de una sociedad tabulada, aseptizada y computarizada? ¿Qué sucederá cuando ya no existan aventuras, ni pueblos, ni religiones, ni actos individuales y descabellados… cuando todo esté explicado y calculado a la perfección – incluido el propio aburrimiento?

¡Qué no se inventará por aburrimiento! dice el hombre del subsuelo. En contra de lo que enseña la filosofía del liberalismo, el móvil profundo de las grandes hazañas del hombre nunca ha sido el interés racional e individual. Sólo así se explica que, a lo largo de la historia, tantos y tantos que comprendieron perfectamente en qué consistían sus auténticos intereses individuales “los dejaran en segundo plano y se precipitaran por otro camino en pos del riesgo y del azar, sin que nada les obligara a ello, más que el deseo de esquivar el camino señalado y de probar terca y voluntariamente otro, más difícil y disparatado” (5). Sólo así se explican las ideas – disparatadas y absurdas desde el estricto punto de vista del interés individual – que han llevado a tantos hombres, a lo largo de la historia, a matar y a morir. Y así se explican, en última instancia, las patrias, las religiones y todas las constelaciones de mitos y de creencias que conforman las identidades de los pueblos y que tantas veces pertenecen al dominio de lo arbitrario y absurdo. “Ni un solo pueblo se ha estructurado hasta ahora sobre los principios de la ciencia y de la razón”, afirma Dostoyevski (6). De ahí la ineptitud última del empeño liberal en sostener toda convivencia colectiva sobre un contrato social, sobre un “patriotismo constitucional” racionalista y aséptico. Porque un proyecto colectivo, si ha de ser duradero, sólo puede sostenerse sobre un núcleo pasional más allá de la razón, sobre las creencias y sobre los mitos.

El sueño del progreso produce monstruos

El sueño del progreso produce monstruos

El antiprogresismo de las “Memorias del subsuelo” no se queda en una diatriba contra la felicidad. En sus páginas aparece una imagen premonitoria: el “Palacio de Cristal” como símbolo del progreso, del fin de la historia. El Palacio de Cristal – pabellón de la exposición universal de Londres que Dostoyevski visitó en 1863– es la representación del universo definitivamente pacificado, estandarizado, homogeneizado. La mirada profética de Dostoyevski anticipa así la desazón posmoderna y nos alerta sobre el mundo del futuro: la sociedad de la transparencia, un inmenso panóptico nivelado y desinteriorizado en el que todos somos vigilados y vigilantes. Un mundo en el que las inquietudes y las apetencias humanas estarán totalmente codificadas – digitalizadas, diríamos nosotros – de forma que, al final, lo más probable es que el habitante de este mundo deje ya de desear, porque “todo se ha disuelto ya en una descomposición química, junto al instinto básico de supervivencia, pues para entonces ya se tendrá todo bien asegurado al milímetro. En cuestión de poco tiempo se pasará de la bulimia a la abulia más cruel con que las salvajes leyes de la naturaleza amenazarán al civilizado homúnculo, producto artificial de una probeta de laboratorio” (7).

Dostoyevski intuye la edad del vacío. La época en la que se abandona cualquier búsqueda de sentido, la época en la que el individuo es rey y maneja su existencia a la carta… pero también la edad en que el individuo es más banal, mediocre y limitado; en la que el hombre es más pusilánime, más dependiente del confort y del consumo; en la que el hombre es menos autónomo en sus juicios, más gregario, servil y victimista. “¡Nos pesa ser hombres, hombres auténticos, de carne y hueso” – exclama el “hombre del subsuelo” –. “Nos avergonzamos de ello, lo tomamos por algo deshonroso y nos esforzamos en convertirnos en una nueva especie de omnihumanos. Hemos nacido muertos y hace tiempo que ya no procedemos de padres vivos, cosa que nos agrada cada vez más. Le estamos cogiendo el gusto”.

El homúnculo: la palabra que el autor ruso acuña para designar al habitante de ese mundo transparente en el que la felicidad dosificada lo es todo. Una criatura en la que Dostoyevski barrunta ya ese “Último hombre” que guiña un ojo y piensa que ha inventado la felicidad (8). A ese “Homo Festivus” del que hablaba Philippe Muray: el consumidor en bermudas,flexible, elástico y cool, desprovisto de toda trascendencia y destinado a heredar la tierra (9).

El homúnculo vive de espaldas a la “auténtica vida”, a la “vida viva”: dos conceptos clave para Dostoyevski. “No hay nada más triste para el autor de Memorias del subsuelo – señala Bela Martinova – que una persona que no sabe vivir; que un hombre que ha perdido el instinto, la intuición certera de saber dónde habita la “fuente viva de la vida”. Dostoyevski es uno de los primeros que olfatea ese progresivo distanciamiento entre el hombre europeo y la realidad primigenia, ese ocultamiento de lo real. Dostoyevski ya había calado al urbanita de nuestros días, desarraigado y alienado, perdido en una realidad virtual de necesidades inducidas, arrancado de la “vida viva”. El hombre del subsuelo agarra al ese hombre por las solapas, lo zarandea violentamente y le obliga a mirarse en el espejo: ¡Ecce Homo Festivus!

El homúnculo vive de espaldas a la “auténtica vida”, a la “vida viva”: dos conceptos clave para Dostoyevski. “No hay nada más triste para el autor de Memorias del subsuelo – señala Bela Martinova – que una persona que no sabe vivir; que un hombre que ha perdido el instinto, la intuición certera de saber dónde habita la “fuente viva de la vida”. Dostoyevski es uno de los primeros que olfatea ese progresivo distanciamiento entre el hombre europeo y la realidad primigenia, ese ocultamiento de lo real. Dostoyevski ya había calado al urbanita de nuestros días, desarraigado y alienado, perdido en una realidad virtual de necesidades inducidas, arrancado de la “vida viva”. El hombre del subsuelo agarra al ese hombre por las solapas, lo zarandea violentamente y le obliga a mirarse en el espejo: ¡Ecce Homo Festivus!

Pero Dostoyevski siempre atisba una salida. Tarde o temprano – nos dice el hombre del subsuelo “aparecerá un caballero que, con una fisonomía vulgar, o con un aspecto retrógrado y burlón (un reaccionario, diríamos nosotros…) se pondrá brazos en jarras y nos dirá a todos: “bueno señores ¿y por qué no echamos de una vez abajo toda esa cordura, para que todos esos logaritmos se vayan al infierno y podamos finalmente vivir conforme a nuestra absurda voluntad?”” ¡Dos más dos son cuatro! Sí, ya lo sabemos. Pero el hombre del subsuelo escupe sobre eso. Tal vez le resulte más atractivo el “dos más dos son cinco”. Porque el “dos más dos son cuatro” ya no es vida… sino el inicio de la muerte.

El grito del hombre del subsuelo es un grito de rebelión contra la futura armonía universal, contra la religión del progreso, contra el mundo de los esclavos felices. Porque la auténtica libertad del espíritu humano – viene a decirnos Dostoyevski – es incompatible con la felicidad. O libres o felices. Y la libertad es aristocrática, no existe más que para algunos elegidos. Algo que sabía muy bien el personaje mítico que culmina su obra, y el que mejor compendia la dialéctica de sus ideas.

Grandes y pequeños Inquisidores

La era tecnotrónica implica la aparición gradual de una sociedad cada vez más controlada y dominada por una elite desembarazada de los valores tradicionales. Esa élite no dudará en alcanzar sus fines políticos mediante el uso de las tecnologías más avanzadas (…) para modelar los comportamientos públicos y mantener a la sociedad bajo estrecha supervisión y control.

ZBIGNIEW BRZEZINSKI

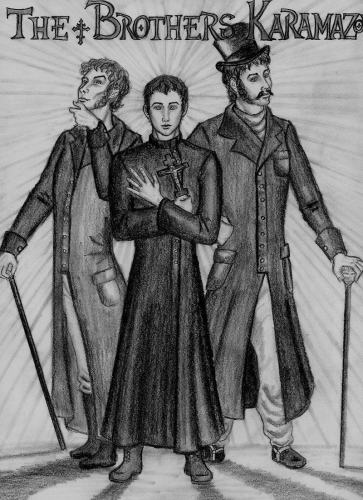

El Gran Inquisidor es demócrata y socialista a su manera. Está lleno de compasión por la gente, alienta un sueño de fraternidad universal y su objetivo es asegurar la felicidad del género humano. El Gran Inquisidor toma el partido de los humildes, de los débiles, de la mayoría. La idea de superación personal le indigna por aristocrática. El Gran Inquisidor guarda un secreto: no cree en Dios. Pero tampoco cree en el hombre. Su misión es organizar el hormiguero humano en una tierra sin Dios.

La “Leyenda del Gran Inquisidor” – inserta en la novela “Los hermanos Karamazov” – consiste en el largo monólogo de este enigmático personaje ante otro al que ha hecho arrestar y que permanece en silencio: Jesucristo, de nuevo entre los hombres. Y en su monólogo el Gran Inquisidor se justifica. Y explica por qué se ha visto obligado a corregir Su obra, por qué ha instaurado una tiranía en Su nombre, en el nombre de una religión puramente formal.

Se trata, según él, de una tiranía necesaria. Porque él sabe que los hombres no quieren ser libres sino felices. Y sabe que no hay nada que torture más al hombre que la ausencia de un porqué, que la falta de un sentido. Pero Cristo, en vez de abrumar al hombre con las pruebas de su divinidad, ha dejado las puertas abiertas a todas las dudas. Porque Él ha querido que la fe sea un acto de libertad. Y el Gran Inquisidor sabe que esa libertad de espíritu es incompatible con la felicidad. Y sabe que los hombres no quieren la libertad, sino la certeza. O mejor aún: sabe que en realidad prefieren no tener que pensar. Y por eso les ha convertido en una masa domesticada.

La felicidad en la tierra. Ésa es la única preocupación del Gran Inquisidor, la única verdad que él reconoce. Porque él sabe que Dios no existe. Y él – un asceta, un hombre de ideas – oculta esa dolorosa verdad al resto de los hombres. Además él sabe que la fe es una responsabilidad con consecuencias demasiado gravosas, y que no está al alcance de todos. Y el Gran Inquisidor, lleno de compasión por los hombres, no puede tolerarlo. ¿Por qué sólo algunos serían los elegidos? ¿Por qué no todos? Y por ello proporciona a los hombres un cúmulo de verdades maleables, flexibles y confortables, adaptadas a la debilidad de la mayoría. Y frente a la religión del pan celestial les ofrece la religión del pan terrenal, el dogma del bienestar en la tierra, la felicidad del rebaño.

“Les daremos una felicidad tranquila, resignada, la felicidad de unos seres débiles, tal y como han sido creados…les obligaremos a trabajar, pero en las horas libres les organizaremos la vida como un juego de niños, con canciones infantiles y danzas inocentes. Les permitiremos también el pecado… ¡son tan débiles e impotentes! y ellos nos amarán como niños a causa de nuestra tolerancia (…) y ya nunca tendrán secretos para nosotros (…) y nos obedecerán con alegría” (10). Un paraíso de beatitud y de simplicidad infantil. ¿Una crítica a la Iglesia católica?

Dostoyevski, ortodoxo militante, no albergaba simpatías por la Iglesia de Roma. Pero es imposible reducir el mito del Gran Inquisidor a una crítica pasajera del catolicismo. Tampoco puede reducirse – como han hecho algunos comentaristas – a una premonición de las utopías totalitarias y socialistas que por aquél entonces ya despuntaban en Rusia. El potencial visionario de Dostoyevski exige una lectura postmoderna, mucho más ambiciosa.

Lo que el autor ruso vaticina – en una intuición tan pasmosa como profética – son los principios básicos de una sociedad de control total, postreligiosa y posthistórica. Una sociedad de la que el espíritu – o cualquier otro elemento de auténtica trascendencia – ha quedado desterrado. El Gran Inquisidor es la primera aparición literaria del Gran Hermano.

Y un mentor para los tiempos actuales. El Gran Inquisidor se alza contra Dios y corrige Su obra en el nombre del hombre. Sus ideas se resumen en dos: rechazo de la libertad en nombre de la felicidad y rechazo de Dios en nombre de la humanidad (11). Su objetivo es globalizador: la unión de todos los hombres en un “hormiguero indiscutible, común y consentidor, porque la necesidad de una unión universal es el último tormento de la raza humana”. El único paraíso posible está aquí, en la tierra. Y la única beatitud posible consiste en el retorno a la inocencia infantil.

¿Y qué mejor para ello que un totalitarismo soft? Un totalitarismo hecho de hipertrofia sentimental, de intervencionismo humanitario, de felicidad como imperativo y de infantilización en el gigantesco parque de atracciones del hiperfestivismo. ¿Algo que ver con los tiempos actuales?

Pero hoy ya no se trata de un Gran inquisidor, sino de muchos. En nuestros días los Grandes Inquisidores anidan en las estructuras de poder del Nuevo Orden Mundial y forman parte de un directorio tecnocrático, financiero y policíaco que vela por la pureza del pensamiento global único. Un pensamiento New Age, festivo y nihilista que se acompaña de un moralismo agresivo. Y armado, si es preciso.

El Gran Inquisidor de Dostoyevski es un personaje trágico, no exento de cierta grandeza. Toma sobre sí toda la carga de la dolorosa verdad y dispensa una felicidad en la que él no puede participar. Pero nuestros tiempos son prosaicos. Los Grandes Inquisidores de nuestros días están encantados de haberse conocido, se reúnen y ríen entre ellos sus ocurrencias, como la de aquél conocido Gran Inquisidor que anunció la buena nueva del “Entetanimiento” (tittytainment): una mezcla de entretenimiento vulgar, propaganda, bazofia intelectual y elementos psicológica y físicamente nutritivos, la fórmula ideal para mantener sedada a la mayoría de la población y evitar estallidos sociales (12).

Pero por muy importante que sea el papel de los Grandes Inquisidores, lo que hace realmente posible que el entetanimiento funcione es todo el entramado de pequeños inquisidores – políticos y economistas, intelectuales de derecha y de izquierda, periodistas y think-tanks, ONGs, “sociedad civil” a sueldo, miembros del show-busines, corporaciones de ocio y entretenimiento – que funcionan como terminales de los poderes hegemónicos, como sus vigilantes, pequeños inquisidores domésticos cuya función consiste en encuadrar a la población en el discurso de valores dominante, en la idea de que no hay alternativas al pensamiento único: un pensamiento liberal-libertario, que no de libertad.

El problema de la libertad es precisamente el gran tema de la obra de Dostoyevski, la cuestión que más le obsesiona. La libertad entendida siempre como libre albedrío, como capacidad de opción moral. Un problema que se sitúa en el núcleo de su concepción religiosa. Una concepción mesiánico-apocalíptica – al decir de sus críticos – que, unida a su intenso patriotismo ruso, es la que más le ha valido su sulfurosa reputación de reaccionario.

Para acabar con el buenismo

Dostoyevski es un escritor del lado oscuro. Sus novelas exploran el componente maligno y demoníaco que anida en la naturaleza humana. Por eso pocas cosas le indignaban tanto como los intentos de “contextualizar” o de negar el mal en el hombre, de atribuirlo a las “condiciones sociales” o a las “circunstancias del entorno”. Dostoyevski se subleva contra esa visión humanitario-progresista – tan vieja como recurrente – según la cuál bastaría con transformar las mencionadas condiciones sociales para que el mal desaparezca, porque en el fondo “todo el mundo es bueno”. Para el autor ruso el mal no es el resultado inevitable de unos condicionantes sociales sino una opción del hombre. El mal es hijo de la libertad, y si reconocemos que el hombre es un ser libre estamos obligados a admitir la existencia del Mal.

La lectura de Dostoyevski es el mejor antídoto contra el buenismo. El autor ruso consideraba el no-reconocimiento del mal como una negación de la naturaleza profunda del hombre, como un atentado contra su responsabilidad y dignidad. Su postura no es ni optimista ni pesimista: no es optimista porque no se minimiza la realidad del mal, y no es pesimista porque no se afirma que el mal sea insuperable. Se trata más bien de una concepción trágica: la vida del hombre está bajo el signo de la lucha entre el bien y el mal (13).

Una concepción trágica y también dialéctica: el bien no sería tal – en expresión de Luigi Pareyson – si no incluye en sí mismo la realidad o posibilidad del mal como momento vencido y superado. Y el dolor es el punto de inflexión de esa dialéctica: al hombre no le queda otra posibilidad para llegar al bien que padecer hasta el fondo el proceso autodestructivo del mal. Porque el mal, por su propia naturaleza, tiende a autodestruirse (14). Dostoyevski siempre encuentra una salida.

Dostoyevski es un pensador cristiano. Y ello a pesar de que el mal y el sufrimiento humano – constantemente presentes en su obra – son los mayores obstáculos para la fe en cuanto conducen a la desesperanza. Pero no es el suyo un cristianismo melifluo del tipo “sonríe Dios te ama”. El suyo es un cristianismo trágico, agónico, forjado en el sufrimiento y en la duda.Dostoyevski quería – dice Nikolay Berdiaev – que toda fe fuese aquilatada en el crisol de las dudas. Porque para él convertir el mensaje de Cristo en verdad jurídica y racional significaba pasar del camino de la libertad al camino de la coacción – como en el caso del Gran Inquisidor –. El autor ruso fue probablemente el más apasionado defensor de la libertad de conciencia que ha conocido el mundo cristiano, y sabía que “si en el mundo hay tanto mal y sufrimiento es porque en la base del mundo se encuentra la libertad. En la libertad está toda la dignidad del mundo y la dignidad del hombre. Sólo sería posible evitar el mal y los sufrimientos al precio del rechazo de la libertad” (15).

“Rusia es un pueblo portador de Dios”, afirma Dostoyevski. El cristianismo y la idea de Rusia se funden para él en una visión mesiánica en la que reverbera la vieja idea de Moscú como “Tercera Roma”, portadora de un mensaje de salvación universal. Una visión en la que asoma ese fondo místico-apocalíptico del espíritu tradicional ruso que resulta tan chocante para el hombre actual. ¿Rusia como nuevo pueblo elegido? ¿Rusia como portadora de un dogma universalista? ¿Rusia destinada a unificar la humanidad, a concluir la historia? Veremos que, como casi todo en Dostoyevski, el camino utilizado es el más tortuoso para decirnos algo bastante diferente. Casi incluso lo contrario.

Los dioses y los pueblos

Quien renuncia a su tierra renuncia también a su Dios

FIODOR M. DOSTOYEVSKI

“El pueblo ruso cree en un cristo ruso. Cristo es el dios nacional, el dios de los campesinos rusos, con rasgos rusos en su imagen. Se observa en ello una tendencia pagana en el seno de la ortodoxia”. El filósofo Nikolay Berdiaev explicaba en esos términos la importancia del cristianismo ortodoxo en la formación de la identidad rusa. La religión ortodoxa hizo a Rusia, y en ese sentido se trata de una religión con un carácter comunitario y patriótico similar al que antaño tenían las religiones paganas que eran, ante todo, religiones de la polis. Rusia se celebra a sí misma a través del Dios ortodoxo, por el cuál participa en el misterio de lo sagrado.

Pero según el cristianismo la verdad es sólo una, la misma para todos los pueblos. De la identificación de Rusia con esa verdad universal nace su conciencia mesiánica, la misma que el monje Filoteo sintetizó en el siglo XVII en la idea de Moscú como “Tercera Roma”. La ortodoxia rusa oscila por tanto entre esos dos polos: por un lado ese populismo religioso que hace de ella una especie de religión tribal, y por otro lado el mensaje universalista y expansivo propio del cristianismo. Esa bipolaridad se da también en Dostoyevski. El autor ruso se adhiere a la verdad universal del cristianismo, pero al mismo tiempo – y ahí está lo novedoso de su pensamiento – parece rechazar el universalismo, es decir, la pretensión de homogeneizar a la humanidad en torno a un único credo. Más bien el contrario, lo que hace es una defensa de las religiones enraizadas: cuanto más vigorosa sea una nación tanto más particular será su Dios.

Especialmente reveladoras son las siguientes frases de su novela Demonios: “Dios constituye la personalidad sintética de todo un pueblo desde su nacimiento hasta su fin. Nunca se ha dado el caso de que todos los pueblos, o muchos de ellos, hayan adorado a un mismo Dios, sino que cada uno de ellos ha tenido siempre el suyo propio (…) Cuando los dioses comienzan a ser comunes es el inicio de la destrucción de las nacionalidades. Y cuando lo son plenamente, mueren los dioses y la fe en ellos, junto con los mismos pueblos”.

¿Instinto pagano en Dostoyevski? El autor ruso expresa la idea de que todos los grandes pueblos tienen que sentirse portadores, de un modo u otro, de una simiente divina, tienen que rodear sus orígenes de un aura mítica. “Ni un solo pueblo se ha estructurado hasta ahora sobre los principios de la ciencia y de la razón”. Siempre había sido así en el pasado hasta que la modernidad comenzó a desencantar el mundo.

Y prosigue:

“Jamás ha existido un pueblo sin religión. O sea, sin un concepto del mal y del bien. Cada pueblo posee su noción del mal y del bien y un bien y un mal propios. Cuando muchas naciones empiezan a comulgar en un mismo concepto del mal y del bien, perecen los pueblos y comienzan a desdibujarse y a desaparecer las diferencias entre el mal y el bien”.

¿Pronóstico de futuro? La época de relativismo en la que vivimos es a su vez la época en la que el sistema de valores occidental – la moralina “derecho-humanista”, la corrección política, la ideología de género y similares – intentan imponerse, por la fuerza incluso, sobre toda la humanidad. Lo que el autor ruso parece decirnos es que, para frenar el relativismo – es decir, para restaurar las ideas del mal y del bien – sería más bien preciso adoptar el enfoque contrario: aceptar el pluralismo de los valores, respetar las sensibilidades de los pueblos, reconocer el mundo como pluriverso.

Los dioses y los pueblos. Dos conceptos que discurren en paralelo y que en Dostoyevski se ligan de forma indisoluble: los pueblos nacen como resultado de una búsqueda de Dios. Continúa el personaje de Demonios:

“Los pueblos se constituyen y mueven en virtud de otra fuerza imperativa y dominante, cuyo origen es tan desconocido como inexplicable. Esa fuerza radica en el inextinguible afán de llegar hasta el fin, más al mismo tiempo niega el fin (…) el objetivo de este movimiento popular, en todas las naciones y en cualquier período de su existencia, se reduce a la búsqueda de Dios, de un Dios propio, infaliblemente propio, y a la fe en él como único verdadero” (16).

Lo que Dostoyevski parece afirmar es que la fuerza del cristianismo – religión de la divinidad encarnada, encastrada por tanto en el tiempo histórico –, consiste en encarnarse a su vez en esas grandes fuerzas motrices de la historia que son las naciones y los pueblos. El momento triunfal del cristianismo se produce cuando toma como vehículo a naciones poderosas, cuando se convierte a su vez en hacedor de naciones. Pero cuando el cristianismo pasa a convertirse en un mero gestor de buenos sentimientos, en un moralismo universalista y desencarnado, entonces se diluye y muere. La historia de Europa es un buen ejemplo de ello.

Una Europa que en tiempos de Dostoyevski se encontraba en la cúspide de su poder. Pero él veía más allá de eso.

Por Europa, contra occidente

“Quiero ir a Europa. Sé que sólo encontraré un cementerio, pero ¡qué cementerio más querido! Allí yacen difuntos ilustres; cada losa habla de una vida pasada ardorosa, de una fe apasionada en sus ideales, de una lucha por la verdad y la ciencia. Sé de antemano que caeré al suelo y que besaré llorando esas piedras convencido de todo corazón de que todo aquello, desde hace tiempo, es ya un cementerio y nada más que un cementerio” (17).

Estas palabras resumen a la perfección los sentimientos de su autor frente a Europa. Dostoyevski fue un ferviente y apasionado patriota europeo. Frente a la imagen que suele tenerse de los eslavófilos como chauvinistas antieuropeos, el autor de Crimen y Castigo dedica sus páginas más tiernas y vehementes a hacer el elogio de Europa en términos que pocos occidentales han empleado jamás.

Estas palabras resumen a la perfección los sentimientos de su autor frente a Europa. Dostoyevski fue un ferviente y apasionado patriota europeo. Frente a la imagen que suele tenerse de los eslavófilos como chauvinistas antieuropeos, el autor de Crimen y Castigo dedica sus páginas más tiernas y vehementes a hacer el elogio de Europa en términos que pocos occidentales han empleado jamás.

“Europa, ¡qué cosa tan terrible y santa es Europa! ¡Si supieran ustedes, señores, hasta que punto nos es querida – a nosotros, los soñadores eslavófilos, odiadores de Europa según ustedes – esa Europa! (…) ¡Como amamos y honramos, de un amor y una estima más que fraternales, las grandes razas que la habitan y todo lo que ellas han culminado de grande y de bello! Si supieran ustedes hasta que punto nos desgarran el corazón (…) las nubes sombrías que cada vez más velan su firmamento” (18).

Dostoyevski nunca llegó a ser un auténtico eslavófilo – o fue tan sólo un eslavófilo sui generis –. Mucho menos era occidentalista. Rechazaba el europeísmo mimético que consistía en importar a Rusia las ideas y la forma de vida occidentales. Para él ser radical y apasionadamente ruso era la mejor forma de servir a Europa. Una civilización sobre la cuál él ya veía abatirse una implacable condena a muerte. La Europa “occidentalista” – la Europa del “Palacio de cristal” y de la triunfante civilización burguesa – no era ya su Europa.

¿Europa u Occidente? Conviene tener bien clara esta distinción. Europa es una cultura y una civilización milenaria, geográficamente delimitada. Occidente es un proyecto de civilización global y homogénea fundada sobre la economía. La victoria de la segunda representa la muerte de la primera. Y eso Dostoyevski lo vio perfectamente. Y no sólo él, en Rusia. Pero lo que él hizo fue expresar, de la forma más contundente y más literariamente elevada, esa idea que ya estaba presente en los principales filósofos religiosos y en el pensamiento metapolítico del país euroasiático. Ese pensamiento era hostil a la Europa Occidental sólo y en la medida en la que en ella triunfa la civilización burguesa. Dostoyevski – al igual que Nietzsche – levantó acta de la muerte de Dios. Y vio que Europa había dejado de ser cristiana. También vio que los proclamados ideales de libertad, igualdad y fraternidad que habían sustituido al cristianismo no eran más que una farsa, en cuanto no puede haber auténtica libertad sin poder económico – idea ésta en la que curiosamente coincidía con Karl Marx – (19).

En ese tesitura ¿qué hacer? ¿Cuál sería la misión de Rusia? Para Dostoyevski la idea de patria es inseparable de la idea de misión. Su patriotismo – y en eso se separaba de los eslavófilos – era ajeno a toda connotación etnicista o nacionalista. Para él la misión de Rusia es universal, ajena a cualquier autoafirmación nacional exclusiva. “Todo gran pueblo ha de creer, si quiere seguir vivo mucho tiempo, que en él y sólo en él está la salvación del mundo; que vive para estar a la cabeza de los pueblos, para unirlos en un común acuerdo y conducirlos hacia el objetivo que les está predestinado”. En el caso contrario “la nación deja de ser una gran nación y se transforma en simple material etnográfico. Una gran nación, cuando verdaderamente lo es, nunca se conforma con un papel secundario en la historia de la humanidad” (20). En un célebre discurso pronunciado meses antes de morir, declaraba:

“Creo firmemente que los rusos del futuro comprenderán en qué consiste ser un verdadero ruso: en esforzarse por aportar la reconciliación definitiva a las contradicciones europeas, en mostrar ante el malestar europeo la salida que ofrece el alma rusa, humana, universal y unificadora (…) pronunciar la palabra definitiva… de la concordia fraternal de todas las razas según la Ley evangélica de Cristo” (21).

Ahí reside la célebre concepción mesiánico-apocalíptica de Dostoyevski, que tan extravagante resulta a los ojos actuales. Una idea en la que confluyen siglos de pensamiento tradicional ruso. ¿Rusia como pueblo elegido? ¿Un ideal de dictadura teocrática? ¿Una justificación del imperialismo ruso?

El mesianismo del autor de Crimen y castigo es grandioso, resplandeciente, místico, apasionado, paradójico… y totalmente utópico. Es decir, está más allá de cualquier análisis racional. Parece además contradictorio con otras posiciones de su autor. ¿Acaso no se rebelaba el “hombre del subsuelo” contra los cánticos a la armonía universal? ¿Acaso no era Dostoyevski – señalábamos antes – partidario de un pluralismo de los valores, absolutamente contrario a cualquier forma de imposición hegemónica? ¿Cómo se concilia eso con su idea del pueblo ruso como agente mesiánico-universal?

El mesianismo del autor de Crimen y castigo es grandioso, resplandeciente, místico, apasionado, paradójico… y totalmente utópico. Es decir, está más allá de cualquier análisis racional. Parece además contradictorio con otras posiciones de su autor. ¿Acaso no se rebelaba el “hombre del subsuelo” contra los cánticos a la armonía universal? ¿Acaso no era Dostoyevski – señalábamos antes – partidario de un pluralismo de los valores, absolutamente contrario a cualquier forma de imposición hegemónica? ¿Cómo se concilia eso con su idea del pueblo ruso como agente mesiánico-universal?

En realidad su mesianismo está alejado de cualquier espíritu de cruzada. También de cualquier idea de totalitarismo teocrático. Sí tiene mucho que ver con una idea central en su pensamiento: la visión del mundo como “una unidad espiritual y moral, una “comunidad fraternal” que debería existir de forma natural, pero que no puede ser creada artificialmente” (22). Una idea que no cesa de repetir en su obra al mostrar una y otra vez lo nefasto de cualquier intento de forzar esa unidad: tal es el caso de los protagonistas de Demonios con su violencia revolucionaria; y – el ejemplo más notorio – tal es el caso del Gran Inquisidor. Tanto el catolicismo como el socialismo eran a sus ojos intentos de imponer la unidad del género humano por medios mecánicos y externos – lo que él llamaba “la hermandad del hormiguero”–. Por el contrario la Iglesia Ortodoxa rusa – de carácter más “nacional” que proselitista – era para él más respetuosa con la libertad, porque siempre habría esperado que la unidad venga por sí sola, de forma espontánea y sin coacciones.

El mesianismo de Dostoyevski se formula en términos más bien humildes: “lo que más tememos es que Europa no nos comprenda y que, como antaño y como siempre, nos acoja desde su orgullo, desde su desprecio y desde su espada, como a bárbaros salvajes indignos de tomar la palabra delante de ella” (23). Se trata de un mesianismo que aspira ante todo a dar testimonio. Testimonio de la existencia de una vía alternativa, específicamente rusa, que trataría de alcanzar una síntesis de elementos espirituales y comunitarios frente al individualismo y el materialismo occidentales. Rusia como nación “portadora de Dios” (nación teófora) que estaría llamada a dar testimonio y a sufrir en nombre de la humanidad. Una intuición que, a tenor de la historia rusa en el siglo XX, parece que tampoco iba tan descaminada.

En Dostoyevski nada hay lineal y cartesiano, todo es complejo y tortuoso. Aunque pueda parecer lo contrario no predica el angelismo. Mucho menos la globalización y el “fin de la historia”. Todo lo contrario. Para él la nación – ese vector de la historia – es la condición del retorno a Dios. Y Dios es “la condición de la perennidad de la nación. Ni un Dios tribal, ni un pueblo-dios, sino el Dios de un pueblo elegido por ese Dios que ha sido, a su vez, reconocido por ese pueblo” (24). El ideal mesiánico de Dostoyevski es una llamada a actuar sobre la historia, no a salir de ella; es una invocación a la fraternidad entre los pueblos, no a su homogeneización o mestizaje.

Y es también una llamada a Europa. Para que ataje su decadencia, para que asuma las riendas de su misión, codo con codo junto a Rusia. Como todos los eslavófilos el autor de Crimen y Castigo era un acérrimo defensor de lo que consideraba como misión histórica de Rusia: la defensa de los pueblos eslavos y de la religión ortodoxa. En su labor de publicista siempre señaló como objetivo de Rusia la reconquista de Constantinopla para la cristiandad: unas páginas tal vez obsoletas que denotan, no obstante, el entusiasmo de un espíritu quijotesco al servicio de Europa (25).

Apocalíptico y no integrado

Albert Camus afirmaba que el auténtico profeta del siglo XIX no era Karl Marx, sino Dostoyevski. El rasgo más sobresaliente del autor ruso es, sin duda alguna, su talento visionario, su capacidad de situarse en el futuro y de percibir el mundo como una lejanía. Eso explica también su contemporaneidad: Dostoyevski no sólo habla al hombre de hoy sino que hace parecer irremediablemente viejos a muchos escritores actuales.

Eso es así porque la suya es una literatura de ideas, no una literatura “literaria”. Su finísima percepción podía captar las corrientes subterráneas del espíritu, las fuerzas profundas que mueven la historia. Se trata por lo tanto del primer gran escritor metapolítico de la historia. Escritor gramscista antes de Gramsci, su obra es la demostración de que toda acción verdadera viene precedida por una idea, de que las ideas tienen consecuencias. Por eso sus grandes personajes son ante todo intelectuales, ideas en acción. Él sabía que en la historia “lo que triunfa no son las masas de millones de hombres ni las fuerzas materiales, que parecen tan fuertes e irresistibles, ni el dinero ni la espada ni el poder sino el pensamiento, casi imperceptible al inicio, de un hombre que frecuentemente parece privado de importancia” (26).

¿Dostoyevski profeta? De todas sus intuiciones, la primera que alcanzó sorprendente cumplimiento fue la revolución rusa. El autor de Demonios – señala Berdiaev – fue “el profeta de la revolución rusa en el sentido más indiscutible de la palabra. La revolución se realizó según Dostoyevski: él reveló su dialéctica interior y le dio forma. Con una presciencia genial él percibió los cimientos ideológicos y el carácter de lo que se preparaba. La novela Demonios trata, no sobre el presente, sino sobre el provenir” (27).

Pero entre sus premoniciones hay otras que hoy nos tocan más a fondo. “Si Dios no existe, todo está permitido”– decía Iván Karamazov. Dostoyevski fue el primero que captó – antes que Friedrich Nietzsche – que el más incómodo de todos los huéspedes, el nihilismo, había llegado para quedarse y que ya nada sería lo mismo. Dostoyevski dedicó toda su vida a combatirlo. Como lo hizo – por un camino tan diferente como lleno de grandeza – el vagabundo de Sils-María. Sus obras son como espadas que se cruzan. Pero también hay paralelismos y coincidencias sorprendentes. Crimen y castigo nos ofrece la prefiguración – y la refutación – del superhombre. La imagen de Cristo del uno se asemeja a la del Zaratustra del otro – “el mismo espíritu de orgullosa libertad, la misma altura pasmosa, el mismo espíritu aristocrático”– (28). Y sobre todo, tanto el uno como el otro aseguraban que sólo la belleza salvaría al mundo. El litigio entre ambos no está resuelto y será posiblemente eterno. Pero la solución al problema del nihilismo, si existe, posiblemente se sitúe en alguna zona de intersección entre estos dos espíritus superiores.

Tras Dostoyevski y Nietzsche se hace imposible volver al antiguo humanismo racionalista. Una nueva corriente, el existencialismo, se abre paso de la mano del autor de Crimen y castigo. Él supo que la libertad humana es la realidad radical, que el hombre está condenado a ser libre, que la libertad es trágica, una carga y un sufrimiento. Él supo también que hoy es imposible proponerle al hombre los remedios de antaño, y eso es lo que hace de él un escritor de nuestro tiempo. Porque – en palabras de Luigi Pareyson – “tras la intensa experiencia nihilista del hombre contemporáneo, la afirmación de Dios ya no puede trasmitirse a través del dulce y familiar hábito de una costumbre o heredarse en el seguro patrimonio de una tradición. Afirmarla ahora exige el trabajo de una verdadera reapropiación personal (…) Dios debe ser objeto de una auténtica recuperación: es necesario saberlo descubrir en el corazón de la negación”. Por eso Dostoyevski – subraya Berdiaev – “no puede ser considerado un escritor pesimista y tenebroso. La luz brilla siempre en las tinieblas”. El cristianismo de Dostoyevski – aunque permanezca fiel a los dogmas milenarios – es un cristianismo de nuevo cuño, un cristianismo existencialista que no mira hacia el pasado sino hacia el nuevo milenio.

Dostoyevski rechaza los mitos optimistas de la razón y del progreso. Sabe perfectamente que el progreso sólo consiste en mera acumulación de conocimientos, y que esa acumulación no garantiza un mayor grado de desarrollo moral, de inteligencia o de felicidad. Pero eso no hace de él un reaccionario o un conservador – al menos no en el sentido habitual del término. Él era demasiado apocalíptico como para pensar que una vuelta atrás sería deseable; demasiado marginal como para pensar en la restauración del antiguo y tranquilo modo de vida. Él era un revolucionario del espíritu. No en vano su mensaje caló hondo en los movimientos vanguardistas que, a comienzos del siglo XX, orquestaron la primera gran rebelión cultural contra el orden racionalista, liberal y burgués. Paradoja suprema: a partir de Dostoyevski la mejor reacción intelectual se torna en vanguardia estética. Modernismo reaccionario o revolución conservadora, tanto da. En el imaginario de la época el autor de Crimen y Castigo representaba el “Este”: una dirección geográfica, una opción política y un universo “mágico” capaz de suministrar una alternativa enérgica frente a la decadencia occidental (29). “Doestoyevski – decía Stefan Zweig – parece abrirse las venas para pintar con su propia sangre el retrato del hombre del futuro”.

Metapolítica de Rusia

Un pueblo sólo puede tener una vida robusta y profunda si está sostenido por ideas. Toda la energía de un pueblo consiste en tomar conciencia de sus ideas ocultas.

FIODOR M. DOSTOYEVSKI

Todo en él era desmesurado, y en eso expresa como ningún otro un rasgo sustantivo de su pueblo. Rusia es un mundo cuya historia sobrepasa lo humano y lo racional, un mundo barroco y excesivo, un imaginario propenso al mito y la utopía. Con Dostoyevski penetramos en “ese mundo primario y elemental en el que nos espera la tensión cósmica del alma rusa: obsesiones, vislumbres alucinantes, humor desgarrado, inesperadas intuiciones” (30). Pero el mesianismo de Dostoyevski – por muy quijotesco, místico y lejano que nos parezca – encierra una metapolítica con contenidos ajustados a la hora actual.

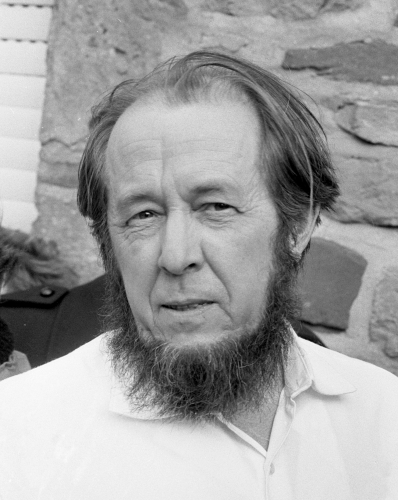

En primer lugar, la crítica de Dostoyevski hacia la civilización europea de su época prefigura algo que Alexander Solzhenitsyn expresaría un siglo más tarde: entre el socialismo totalitario – que anula la libertad humana – y el capitalismo libertario – que llama tolerancia a la permisividad moral necesaria para el desarrollo del mercado – no hay diferencia sustantiva, en cuanto ambos expresan una falta de respeto a la dignidad profunda del hombre.

En segundo lugar Dostoyevski vislumbra ya a la Europa-cementerio, la Europa-museo, esa almoneda de recuerdos santos y heroicos que sólo le inspira tristeza y compasión. Presiente un mundo en proa a la disolución y aspira a un revulsivo que le saque de su letargo.

En tercer lugar, su obra expresa un designio que explica la trayectoria histórica de Rusia a lo largo de siglos: la idea de la complementariedad profunda entre Europa y Rusia. La convicción – que aparece de forma recurrente en los mejores pensadores rusos – de que el porvenir de Rusia está vinculado al de Europa, y que el porvenir de Europa debe incluir a Rusia. Una idea que se corresponde con todas las realidades geopolíticas, históricas y culturales del viejo continente. Eso que alguien definió hace décadas como la “Europa del Atlántico hasta los Urales” (31).

Decía Ortega y Gasset que Rusia es un pueblo de una edad diferente a la nuestra, un pueblo aún en fermento, es decir, juvenil. Los pueblos jóvenes – que suelen ser considerados como pueblos “bárbaros” – son todavía capaces de experiencias radicales y se encuentran más cerca de aquello que Dostoyevski llamaba “las fuentes vivas de la vida”: los valores arquetípicos que hemos olvidado, los vínculos comunitarios que hemos perdido. Es bien sabido que, frente a la decadencia, los “bárbaros” son siempre una terapia de choque. Tal vez hoy sería conveniente “ponerse a la escucha” de lo que puedan decirnos los bárbaros. Y tal vez viendo lo que no somos podamos recuperar un día el pulso de lo que fuimos.

Por de pronto los hombres del fin de historia – los “hombres festivos”, los “homúnculos” – continúan su progreso hacia el Palacio de Cristal, pastoreados por los Grandes Inquisidores de turno. Pero puede que algún día se oiga un grito procedente del subsuelo. Un grito que parezca venir de la noche de los tiempos; o tal vez de un hombrecillo de ojos rasgados como los de un tártaro; o tal vez desde el fondo de nuestra conciencia. Y será una llamada a recomenzar la historia. Como Dostoyevski no cesaba de repetir, tarde o temprano siempre hay una salida.

Notas:

(1) El profesoral y relamido Vladimir Nabokov califica a Dostoyevski de “escritor mediocre” en su Curso de literatura rusa, Ediciones B 1997, pags 193 y ss. Por su parte el crítico Solomon Volkov hace un símil eficaz: “la gente que se maravilla en los museos ante la densidad de los originales de Van Gogh y siente la descarga de cada brochazo nervioso, y luego ve esos mismos originales en reproducciones, entenderá lo que digo: Dostoyevski debe leerse en ruso”. Solomon Volkov, Romanov Riches. Russian Writers and artists under the Tsars. Kindle Edition.

(2) “En Dostoyevski – añade Pareyson – los príncipes no son príncipes, los empleados no son empleados, las prostitutas no son prostitutas, sino que todos tienen algo de otro y todos poseen algo de más, y solamente ese algo de más es lo que cuenta.”. Luigi Pareyson, Dostoievski. Filosofía, novela y experiencia religiosa. Ediciones Encuentro 2007, pags. 34 -40

(3) Stefan Zweig, Dostoïevski. Essais III. La Pochotèque- Le Livre de Poche1996, pags 127 y 135.

(4) Sémion Frank, en La legende du Grand Inquisiteur de Dostoïevski, commentée par Léontiev, Soloviev, Rozanov, Boulgakov, Berdiaev, Frank. L´Age d´Homme 2004, pag 365.

(5) Dostoyevski, Memorias del subsuelo.

(6) En la novela Demonios.

(7) Bela Martinova, Introducción a Memorias del subsuelo. Dostoyevski. Cátedra Letras universales 2009, pag. 60.

(8) Nietzsche, Así habló Zaratustra.

(9) Sobre la obra de Philippe Muray, el artículo de Rodrigo Agulló: Philippe Muray y la demolición del progresismo: http://www.elmanifiesto.com/articulos.asp?idarticulo=3936

(10) Fiodor M. Dostoyevski, La leyenda del Gran Inquisidor.

(11) Nikolay Berdiaev en La legende du Grand Inquisiteur de Dostoïevski, commentée par Léontiev, Soloviev, Rozanov, Boulgakov, Berdiaev, Frank. L´Age d´Homme 2004, pag 329.

(12) Zbigniew Brzesinski – antiguo asesor del Presidente EEUU Jimmy Carter, ideólogo neoliberal y miembro de la Comisión Trilateral– formuló la doctrina del Tittytainment ante una reunión de líderes mundiales organizada por el Global Braintrust en el Hotel Fairmont de San Francisco en octubre 1995. Gabriel Sala, Panfleto contra la estupidez contemporánea. Laetoli 2007.

En un registro intelectual bastante más elevado la figura del filósofo judeo-norteamericano Leo Strauss (1899-1973) guarda una inquietante similitud con algunos aspectos del Gran Inquisidor. Strauss defendía la utilidad de la religión y la patria como instrumentos de control social, y se complacía en la idea de una elite intelectual atea y con un nivel superior de gnosis que le facultaría para guiar a la gran masa durmiente. Leo Strauss y sus discípulos serían la principal fuente intelectual del movimiento “neocon” norteamericano, una cantera especialmente fecunda de “Grandes Inquisidores”.

(13) ¿Maniqueísmo? Señala Pareyson que “Dostoyevski no quiere reducir la dialéctica del bien y del mal a un grandioso suceso cósmico, como en el maniqueísmo. Para él es una tragedia humana, más aún, la tragedia del hombre, pero es necesario que sea enteramente implantada sobre la libertad”. Luigi Pareyson, Dostoievski. Filosofía, novela y experiencia religiosa. Ediciones Encuentro 2007, pags. 96 y 187.

(14) Luigi Pareyson, Obra citada, pags. 101, 110 y 185. Para Dostoyevski el dolor forma parte de un proceso de redención. Por eso considera que, frente al delito, la imposición de castigo es mucho más respetuosa para la dignidad humana que la ausencia del mismo, porque al considerar al hombre como culpable del mal perpetrado se le reconoce libertad, dignidad y responsabilidad.

(15) Nikolay Berdiaev, El espíritu de Dostoyevski Nuevo Inicio 2008, pags 80, 89 y 217. En relación al cristianismo como experiencia dubitativa y agónica la comparación entre Dostoyevski y Miguel de Unamuno se hace inevitable.

(16) Es interesante poner en paralelo esta idea del nacimiento de los pueblos con los conceptos – cargados de mística aunque procedan de un antropólogo – de “pasionariedad” y de “etnogénesis” teorizados por el eurasista Lev Gumilev (1912-1992). Para este autor la “pasionariedad” es el fenómeno por el cuál determinadas etnias o grupos de individuos se comportan a veces, sin motivo racional aparente, de una manera extraña, acometiendo actos y realizando hazañas que sobrepasan el horizonte de su vida cotidiana. Es una especie de energía exposiva “misteriosa” e inexplicable que pone en marcha a los pueblos y a las tribus. Para Gumilev el etnos accede a la existencia por una explosión de energía de pasionariedad. (Alexandre Dougine, L´appel de L´Eurasie. Conversation avec Alain de Benoist. Avatar Éditions 2013).

Todas estas ideas – procedentes de la novela Demonios – son expresadas por Shatov: un personaje a través del cuál, según Berdiaev, Dostoyevski estaría criticando precisamente el “populismo religioso”. Conviene por tanto no descartar cierta distancia de Dostoyevski respecto a ellas. No obstante, también es cierto que este discurso está significativamente próximo a lo expresado por Dostoyevski en otras obras, así como a las ideas que expresa en primera persona en su Diario de un escritor (obra que contiene lo esencial de su pensamiento político).

(17) Fedor M. Dostoyevski, Los hermanos Karamazov.

(18) Fiodor M. Dostoyevski, Confesión de un eslavófilo, en “Diario de un escritor” (julio-agosto 1877).

(19) En la crítica rusa al occidente burgués destacan los filósofos Konstantin Léontiev (1831-1891) y Vladimir Soloviev (1853-1900). En algunos autores rusos – Dostoyevski entre ellos – se rastrean elementos del espíritu colectivista presente en la tradición rusa, de eso que Berdiaev llamaba “un anarquismo y un socialismo cristiano particulares, muy diferentes del anarquismo y del socialismo ateo”. Se trata del ideal de la obshina, la comunidad campesina popular, exaltada por los primeros eslavófilos. En Dostoyevski el “hombre del subsuelo” sería el hombre que ha roto su contacto con la obshina y que se encuentra desarraigado, perdido en la urbe.

(20) Fiodor M. Dostoyevski, en Diario de un escritor y Demonios.

(21) Discurso pronunciado el 8 de junio en Moscú ante la Sociedad de los amigos de la literatura rusa, con ocasión del aniversario de Pushkin. Este discurso conviertió a Dostoyevski en un símbolo nacional.

(22) Kyril FitzLyon, prefacio a: Winter notes on summer impressions, de Fiodor M. Dostoevsky. Alma classics 2013, pag. VIII.

(23) Fiodor M. Dostoyevski, Confesión de un eslavófilo, en “Diario de un escritor” (julio-agosto 1877).

(24) Jean-Francois Colosimo, L´Apocalypse russe. Dieu au pays de Dostoïevski. Fayard 2008, pag 198.

(25) La obra de Cervantes constituía para Dostoyevski la cima de la literatura universal. A este respecto es ilustrativo el extraordinario ensayo que en 1957 publicó el profesor Santiago Montero Díaz: Cervantes, compañero eterno (Linteo, 2005)

(26) Luigi Pareyson, Obra citada, pag. 46

(27) Nikolay Berdiaev, Obra citada, pags. 143-144.

(28) Nikolay Berdiaev, Obra citada, pag. 223.

(29) Alain de Benoist, Arthur Moeller Van der Bruck, une “question à la destinée allemande” Nouvelle Ecole numéro 35/hiver 1979-1980, pag.44.

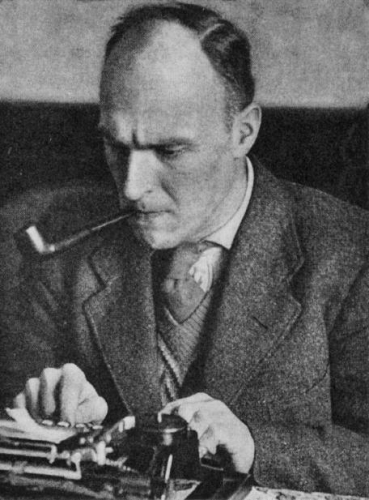

Alemania fue, con diferencia, el país donde la obra de Dostoyevski tuvo mayor impacto: en la patria del romanticismo el terreno estaba bien abonado. Especialmente relevante fue la fascinación que ejerció sobre la juventud alemana y sobre los autores de la “Revolución conservadora”, de quienes el autor ruso puede considerarse – junto a Nietzsche – como una especie de mentor. Arthur Moeller Van der Bruck (1876-1925) preparó – en colaboración con el escritor ruso Dimitri Merezhovski (1866-1941) – una edición alemana de sus obras completas en 22 tomos que obtuvo un inmenso éxito.

(30) Santiago Montero Díaz, Cervantes, compañero eterno. Linteo 2005, pag. 61.

(31) Y que más recientemente se ha reformulado en expresiones como: “el eje París-Berlín-Moscú” o “la gran Europa, desde Lisboa hasta Vladivostok”.

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

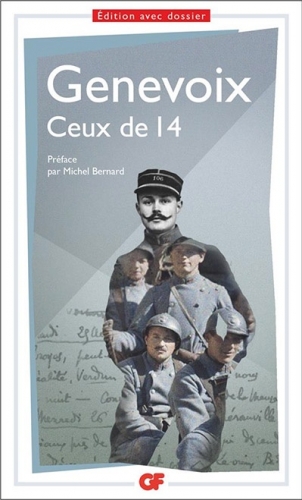

Storiavoce vous a proposé toute une programmation consacrée à la Grande Guerre notamment à ses conséquences politiques et économiques, internationales et géopolitiques… Or, il est un domaine que nous avons oublié à tort, il s’agit de la littérature.

Storiavoce vous a proposé toute une programmation consacrée à la Grande Guerre notamment à ses conséquences politiques et économiques, internationales et géopolitiques… Or, il est un domaine que nous avons oublié à tort, il s’agit de la littérature.

En materia de sufrimiento Fiodor M. Dostoyevski no hablaba de oídas.

En materia de sufrimiento Fiodor M. Dostoyevski no hablaba de oídas. Un individuo resentido, cicatero, cruel. Una risotada brutal que procede de la noche de los tiempos. El “hombre del subsuelo” es el primer antihéroe de la historia de la literatura. Con él Dostoyevski comienza a ser Dostoyevski. Décadas antes de Sigmund Freud el autor ruso desciende al sótano del subconsciente y da la palabra a ese hombrecillo oculto, aherrojado en los grilletes de la civilización y del progreso. Un individuo que se revela como un reaccionario salvaje. Y que la emprende contra una de las manías favoritas de la modernidad y del progreso: ¿a qué viene esa obligación de ser, a toda costa, felices? ¿Es eso de verdad lo que queremos?

Un individuo resentido, cicatero, cruel. Una risotada brutal que procede de la noche de los tiempos. El “hombre del subsuelo” es el primer antihéroe de la historia de la literatura. Con él Dostoyevski comienza a ser Dostoyevski. Décadas antes de Sigmund Freud el autor ruso desciende al sótano del subconsciente y da la palabra a ese hombrecillo oculto, aherrojado en los grilletes de la civilización y del progreso. Un individuo que se revela como un reaccionario salvaje. Y que la emprende contra una de las manías favoritas de la modernidad y del progreso: ¿a qué viene esa obligación de ser, a toda costa, felices? ¿Es eso de verdad lo que queremos? El sueño del progreso produce monstruos

El sueño del progreso produce monstruos El homúnculo vive de espaldas a la “auténtica vida”, a la “vida viva”: dos conceptos clave para Dostoyevski. “No hay nada más triste para el autor de Memorias del subsuelo – señala Bela Martinova – que una persona que no sabe vivir; que un hombre que ha perdido el instinto, la intuición certera de saber dónde habita la “fuente viva de la vida”. Dostoyevski es uno de los primeros que olfatea ese progresivo distanciamiento entre el hombre europeo y la realidad primigenia, ese ocultamiento de lo real. Dostoyevski ya había calado al urbanita de nuestros días, desarraigado y alienado, perdido en una realidad virtual de necesidades inducidas, arrancado de la “vida viva”. El hombre del subsuelo agarra al ese hombre por las solapas, lo zarandea violentamente y le obliga a mirarse en el espejo: ¡Ecce Homo Festivus!

El homúnculo vive de espaldas a la “auténtica vida”, a la “vida viva”: dos conceptos clave para Dostoyevski. “No hay nada más triste para el autor de Memorias del subsuelo – señala Bela Martinova – que una persona que no sabe vivir; que un hombre que ha perdido el instinto, la intuición certera de saber dónde habita la “fuente viva de la vida”. Dostoyevski es uno de los primeros que olfatea ese progresivo distanciamiento entre el hombre europeo y la realidad primigenia, ese ocultamiento de lo real. Dostoyevski ya había calado al urbanita de nuestros días, desarraigado y alienado, perdido en una realidad virtual de necesidades inducidas, arrancado de la “vida viva”. El hombre del subsuelo agarra al ese hombre por las solapas, lo zarandea violentamente y le obliga a mirarse en el espejo: ¡Ecce Homo Festivus!

Estas palabras resumen a la perfección los sentimientos de su autor frente a Europa. Dostoyevski fue un ferviente y apasionado patriota europeo. Frente a la imagen que suele tenerse de los eslavófilos como chauvinistas antieuropeos, el autor de Crimen y Castigo dedica sus páginas más tiernas y vehementes a hacer el elogio de Europa en términos que pocos occidentales han empleado jamás.

Estas palabras resumen a la perfección los sentimientos de su autor frente a Europa. Dostoyevski fue un ferviente y apasionado patriota europeo. Frente a la imagen que suele tenerse de los eslavófilos como chauvinistas antieuropeos, el autor de Crimen y Castigo dedica sus páginas más tiernas y vehementes a hacer el elogio de Europa en términos que pocos occidentales han empleado jamás. El mesianismo del autor de Crimen y castigo es grandioso, resplandeciente, místico, apasionado, paradójico… y totalmente utópico. Es decir, está más allá de cualquier análisis racional. Parece además contradictorio con otras posiciones de su autor. ¿Acaso no se rebelaba el “hombre del subsuelo” contra los cánticos a la armonía universal? ¿Acaso no era Dostoyevski – señalábamos antes – partidario de un pluralismo de los valores, absolutamente contrario a cualquier forma de imposición hegemónica? ¿Cómo se concilia eso con su idea del pueblo ruso como agente mesiánico-universal?

El mesianismo del autor de Crimen y castigo es grandioso, resplandeciente, místico, apasionado, paradójico… y totalmente utópico. Es decir, está más allá de cualquier análisis racional. Parece además contradictorio con otras posiciones de su autor. ¿Acaso no se rebelaba el “hombre del subsuelo” contra los cánticos a la armonía universal? ¿Acaso no era Dostoyevski – señalábamos antes – partidario de un pluralismo de los valores, absolutamente contrario a cualquier forma de imposición hegemónica? ¿Cómo se concilia eso con su idea del pueblo ruso como agente mesiánico-universal?

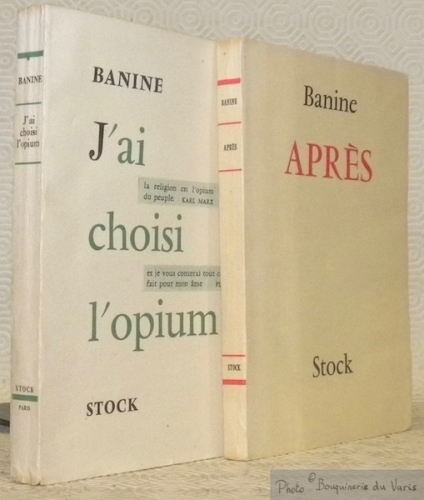

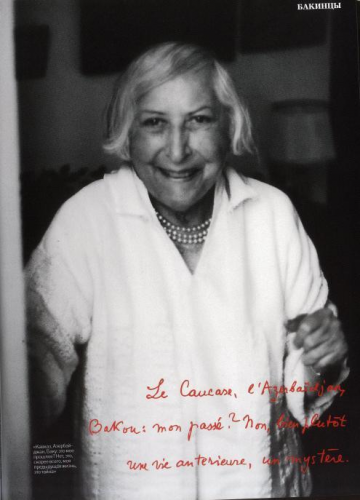

“Aujourd’hui, Jeanne Sandelion a déjeuné chez moi. Depuis qu’elle donne dans la piété, l’âge critique aidant (le Dieu du retour d’âge), elle a beaucoup gagné. Au lieu de parler de robinets détraqués ou de poêles qui se distinguent par leur mauvais tirage, elle m’entretient de la vie de son âme - qui est belle. (…) Cette conversation avec J. S m’a fait du bien. Elle prétend être passée par les mêmes tourments pour ensuite redevenir heureuse par une sorte de grâce survenue un jour, à l’improviste.” (page 29 et 30).

“Aujourd’hui, Jeanne Sandelion a déjeuné chez moi. Depuis qu’elle donne dans la piété, l’âge critique aidant (le Dieu du retour d’âge), elle a beaucoup gagné. Au lieu de parler de robinets détraqués ou de poêles qui se distinguent par leur mauvais tirage, elle m’entretient de la vie de son âme - qui est belle. (…) Cette conversation avec J. S m’a fait du bien. Elle prétend être passée par les mêmes tourments pour ensuite redevenir heureuse par une sorte de grâce survenue un jour, à l’improviste.” (page 29 et 30). Le 12 avril 1954, elle écrit : “Non seulement je n’ai pas été heureuse, mais, surtout, je n’ai pu rendre heureux personne. Si un au-delà existe et si on doit un jour comparaître devant une instance supérieure, quelle sera ma justification ? Un énorme zéro.” (page 54).

Le 12 avril 1954, elle écrit : “Non seulement je n’ai pas été heureuse, mais, surtout, je n’ai pu rendre heureux personne. Si un au-delà existe et si on doit un jour comparaître devant une instance supérieure, quelle sera ma justification ? Un énorme zéro.” (page 54).

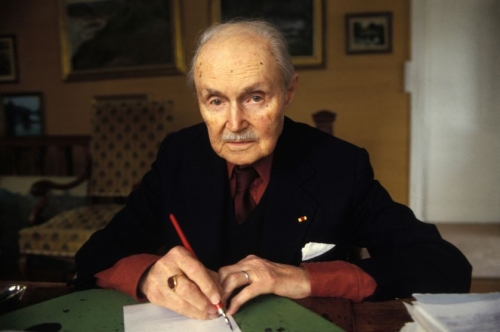

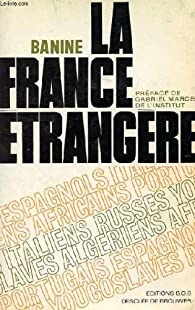

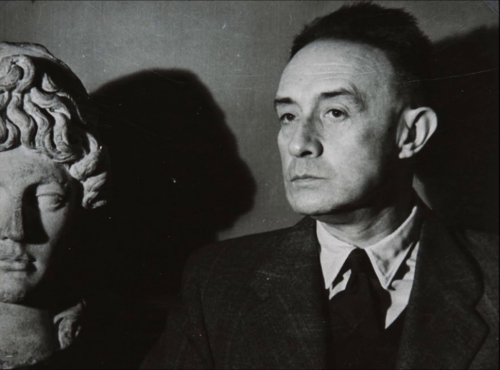

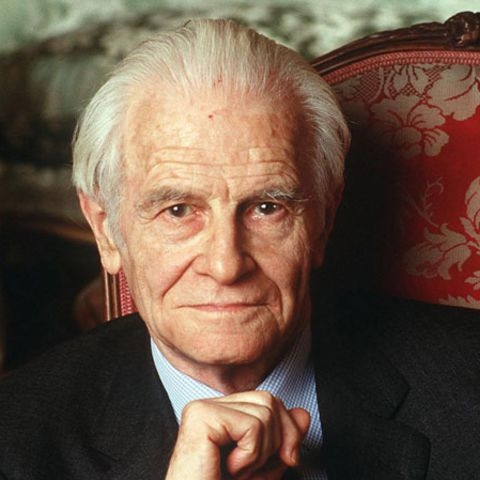

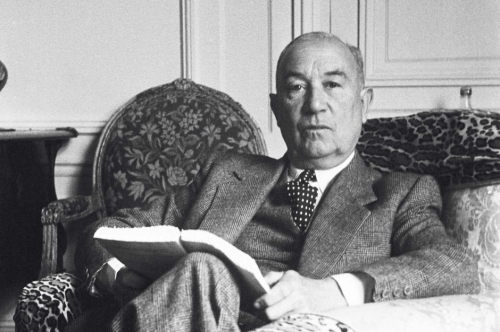

Félicien Marceau était un grand vivant qui fait honte aux moribonds, à leurs pauvres et funestes rêveries. Toutes les apparences de la santé se fixent dans ses livres, une lucidité indulgente, une gravité toujours teintée d’une sorte de tendresse ironique. Il a un air désinvolte, narquois et avide pour parler de la vie; il invente presque une façon nouvelle d’être heureux; il se compose devant l’existence une attitude goguenarde et insolente.

Félicien Marceau était un grand vivant qui fait honte aux moribonds, à leurs pauvres et funestes rêveries. Toutes les apparences de la santé se fixent dans ses livres, une lucidité indulgente, une gravité toujours teintée d’une sorte de tendresse ironique. Il a un air désinvolte, narquois et avide pour parler de la vie; il invente presque une façon nouvelle d’être heureux; il se compose devant l’existence une attitude goguenarde et insolente. S’extirpant de la glu de la camaraderie, Carette quitte donc la radio le 15 mai 1942. Il fonde sa propre maison d’édition, où il publie notamment le grand dramaturge Michel de Ghelderode, mais il ne choisit pas pour autant la voie de la Résistance. À la Libération, il apprend que la police le recherche, il fuit donc vers la France, en compagnie de sa femme, avec pour seul bien une valise et son Balzac dans l’édition de la Pléiade. En janvier 1946, il est jugé par contumace et condamné à quinze ans de travaux forcés par le conseil de guerre de Bruxelles qui, sur trois cents émissions, a retenu cinq textes à sa charge : deux chroniques sur les officiers belges restés en France, une interview d’un prisonnier de guerre revenant d’Allemagne, un reportage sur le bombardement de Liège et une actualité sur les ouvriers volontaires pour le Reich. Ces émissions ne sont pas neutres. Comme le dit l’historienne belge Céline Rase dans la thèse qu’elle vient de soutenir à l’université de Namur : « Les sujets sont anglés de façon à être favorables à l’occupant. » Cela ne suffit pas à faire de Carette un fanatique de la collaboration. Ainsi, en tout cas, en ont jugé le général de Gaulle qui, au vu de son dossier, lui a accordé la nationalité française en 1959 et Maurice Schumann, la voix de Radio Londres qui, en 1975, a parrainé sa candidature à l’Académie française.

S’extirpant de la glu de la camaraderie, Carette quitte donc la radio le 15 mai 1942. Il fonde sa propre maison d’édition, où il publie notamment le grand dramaturge Michel de Ghelderode, mais il ne choisit pas pour autant la voie de la Résistance. À la Libération, il apprend que la police le recherche, il fuit donc vers la France, en compagnie de sa femme, avec pour seul bien une valise et son Balzac dans l’édition de la Pléiade. En janvier 1946, il est jugé par contumace et condamné à quinze ans de travaux forcés par le conseil de guerre de Bruxelles qui, sur trois cents émissions, a retenu cinq textes à sa charge : deux chroniques sur les officiers belges restés en France, une interview d’un prisonnier de guerre revenant d’Allemagne, un reportage sur le bombardement de Liège et une actualité sur les ouvriers volontaires pour le Reich. Ces émissions ne sont pas neutres. Comme le dit l’historienne belge Céline Rase dans la thèse qu’elle vient de soutenir à l’université de Namur : « Les sujets sont anglés de façon à être favorables à l’occupant. » Cela ne suffit pas à faire de Carette un fanatique de la collaboration. Ainsi, en tout cas, en ont jugé le général de Gaulle qui, au vu de son dossier, lui a accordé la nationalité française en 1959 et Maurice Schumann, la voix de Radio Londres qui, en 1975, a parrainé sa candidature à l’Académie française. De la lecture d’Une ténébreuse affaire, il tira la leçon, aussitôt appliquée, que dans la mesure où ce ne sont pas des juges mais des adversaires qui siègent dans un procès politique, il est préférable de s’exiler. Ce qu’il fit à la libération de son pays, en s’installant en France. Une fois arrivé, il a voulu, avant même de reprendre la plume, tourner la page. Il s’est donc doté d’un nouveau nom pour une nouvelle naissance et ce nom n’est évidemment pas choisi au hasard : il se lit comme une promesse de gaieté et d’insouciance après les sombres temps de la politique totale. Promesse tenue pour notre bonheur dans des romans comme Les Passions partagées ou Un oiseau dans le ciel.

De la lecture d’Une ténébreuse affaire, il tira la leçon, aussitôt appliquée, que dans la mesure où ce ne sont pas des juges mais des adversaires qui siègent dans un procès politique, il est préférable de s’exiler. Ce qu’il fit à la libération de son pays, en s’installant en France. Une fois arrivé, il a voulu, avant même de reprendre la plume, tourner la page. Il s’est donc doté d’un nouveau nom pour une nouvelle naissance et ce nom n’est évidemment pas choisi au hasard : il se lit comme une promesse de gaieté et d’insouciance après les sombres temps de la politique totale. Promesse tenue pour notre bonheur dans des romans comme Les Passions partagées ou Un oiseau dans le ciel.

Mais si la forme varie, la pensée de l’écrivain se caractérise par la constance de son questionnement. La virtuosité chez lui va de pair avec l’opiniâtreté. « Tous mes livres, écrit-il en 1994, sont une longue offensive contre ce que dans L’œuf j’ai appelé le Système, c’est-à-dire le signalement qu’on nous donne de la vie et des hommes. Ces lieux communs sont plus dangereux que le mensonge parce qu’ils ont un fond de vérité mais qu’ils deviennent mensonge lorsqu’on en fait une vérité absolue. »

Mais si la forme varie, la pensée de l’écrivain se caractérise par la constance de son questionnement. La virtuosité chez lui va de pair avec l’opiniâtreté. « Tous mes livres, écrit-il en 1994, sont une longue offensive contre ce que dans L’œuf j’ai appelé le Système, c’est-à-dire le signalement qu’on nous donne de la vie et des hommes. Ces lieux communs sont plus dangereux que le mensonge parce qu’ils ont un fond de vérité mais qu’ils deviennent mensonge lorsqu’on en fait une vérité absolue. » Son roman Creezy lui vaut le Goncourt en 1969 ; en 1974, il reçoit le prix Prince Pierre de Monaco et sa course aux honneurs s’achève l’année suivante, dans un fauteuil laissé vacant par Marcel Achard, sous la plus illustre des coupoles. Cette élection n’est pas sans remuer des souvenirs. Pierre Emmanuel démissionne de l’Académie et Marceau le renvoie à son livre de souvenirs. Les Années courtes (1968), dans lequel il a fait le jour sur les engagements de sa jeunesse. Le scandale est bien vite émoussé et l’écrivain peut continuer sa vie de romancier, tenant de temps à autre une chronique au Figaro, offrant régulièrement un nouveau texte, abordant tous les genres et tous les styles, en restant cependant fidèle à ses principes: «Pour le romancier, la réalité n’est qu’un point de départ à partir de quoi il nous propose (…) une autre vie.»

Son roman Creezy lui vaut le Goncourt en 1969 ; en 1974, il reçoit le prix Prince Pierre de Monaco et sa course aux honneurs s’achève l’année suivante, dans un fauteuil laissé vacant par Marcel Achard, sous la plus illustre des coupoles. Cette élection n’est pas sans remuer des souvenirs. Pierre Emmanuel démissionne de l’Académie et Marceau le renvoie à son livre de souvenirs. Les Années courtes (1968), dans lequel il a fait le jour sur les engagements de sa jeunesse. Le scandale est bien vite émoussé et l’écrivain peut continuer sa vie de romancier, tenant de temps à autre une chronique au Figaro, offrant régulièrement un nouveau texte, abordant tous les genres et tous les styles, en restant cependant fidèle à ses principes: «Pour le romancier, la réalité n’est qu’un point de départ à partir de quoi il nous propose (…) une autre vie.»

Essais:

Essais:

De ce fait le roman présente un intérêt historique évident, qui tient pour une large part à l’acuité de son auteur et à ses ambiguïtés – surtout pour nous autres, lecteurs contemporains, à qui la Seconde Guerre mondiale apparaît volontiers comme un affrontement manichéen qui rend impossible une compréhension exacte de ses ressorts historiques.

De ce fait le roman présente un intérêt historique évident, qui tient pour une large part à l’acuité de son auteur et à ses ambiguïtés – surtout pour nous autres, lecteurs contemporains, à qui la Seconde Guerre mondiale apparaît volontiers comme un affrontement manichéen qui rend impossible une compréhension exacte de ses ressorts historiques. La condamnation pour complicité dans l'affaire Rathenau est toutefois décisive : la prison sera rétrospectivement une chance à plus d'un titre. Pour notre bonheur, d’abord, parce que cet épisode fournit le prétexte à certaines des pages les plus drôles du roman, von Salomon traitant de la vie carcérale avec un humour féroce, se réjouissant par exemple de pouvoir écrire en toute sérénité sans avoir à se soucier ni du gîte ni du couvert ; pour le sien, ensuite, parce que ce séjour en prison empêche sa réintégration au grade de sous-officier dans la Wehrmacht, lorsque la Seconde Guerre mondiale éclate (von Salomon appartient au corps royal des cadets, une expérience décrite dans le roman Les Cadets). Il peut ainsi se maintenir simultanément à l'écart de la politique, du front (il travaille pendant ces années dans l'industrie cinématographique) et par voie de conséquence, de la potence, une fois la guerre perdue.

La condamnation pour complicité dans l'affaire Rathenau est toutefois décisive : la prison sera rétrospectivement une chance à plus d'un titre. Pour notre bonheur, d’abord, parce que cet épisode fournit le prétexte à certaines des pages les plus drôles du roman, von Salomon traitant de la vie carcérale avec un humour féroce, se réjouissant par exemple de pouvoir écrire en toute sérénité sans avoir à se soucier ni du gîte ni du couvert ; pour le sien, ensuite, parce que ce séjour en prison empêche sa réintégration au grade de sous-officier dans la Wehrmacht, lorsque la Seconde Guerre mondiale éclate (von Salomon appartient au corps royal des cadets, une expérience décrite dans le roman Les Cadets). Il peut ainsi se maintenir simultanément à l'écart de la politique, du front (il travaille pendant ces années dans l'industrie cinématographique) et par voie de conséquence, de la potence, une fois la guerre perdue. On sent bien que la politique dans son sens le plus noble, celle qui s’attache aux États et aux peuples, est un tropisme de Von Salomon, et la politique occupe évidemment le devant de la scène dans la période; pourtant Le Questionnaire ne s'y résume pas, loin de là. Outre le récit des différents épisodes de la vie de l’auteur, on y trouve de nombreuses réflexions sur l'art, l'écriture et la littérature, sur l'Histoire, la société, la culture. Von Salomon est aussi un bon vivant, qui aime manger, boire, séduire, conduire des voitures avec une «gueule chromée», plutôt cigale que fourmi, et qui nous offre à l’occasion des saillies authentiquement rabelaisiennes.

On sent bien que la politique dans son sens le plus noble, celle qui s’attache aux États et aux peuples, est un tropisme de Von Salomon, et la politique occupe évidemment le devant de la scène dans la période; pourtant Le Questionnaire ne s'y résume pas, loin de là. Outre le récit des différents épisodes de la vie de l’auteur, on y trouve de nombreuses réflexions sur l'art, l'écriture et la littérature, sur l'Histoire, la société, la culture. Von Salomon est aussi un bon vivant, qui aime manger, boire, séduire, conduire des voitures avec une «gueule chromée», plutôt cigale que fourmi, et qui nous offre à l’occasion des saillies authentiquement rabelaisiennes. Von Salomon consacre près de quatre-vingt pages (642-722) à un séjour en terres basques, du côté de Saint-Jean-de-Luz (le questionnaire s'intéresse à ses séjours à l'étranger) où il fait la connaissance de Mayie, avec laquelle il entretient une relation avant de regagner l'Allemagne. Ce roman dans le roman, évocation nostalgique d'un paradis perdu, s'intercale de façon presque surréaliste entre les derniers moments du régime nazi et l'entrée des Américains dans une Allemagne défaite, et s'imprime dans ce long récit comme un songe – et c'est sans doute comme un songe que ce souvenir est resté à von Salomon, qui écrit : «Mais quand je pense à Mayie, je pense à la France et quand je pense à la France, je pense à Mayie. Ô douce Mayie, Ô Sainte France ! Vous m'avez donné le rêve de ma vie, les grandes vacances de ma vie» (pp. 719-720). Le sentiment qui s’en dégage s’approche de celui que suscite le dernier moment de L’Éducation sentimentale. Ceux qui l’auront lu se souviendront sans doute du vertigineux saut dans le temps que ménage Flaubert à la fin du roman. Proust, à ce propos, écrit en 1920 (À propos du style de Flaubert, in La Nouvelle revue française) : «Sans l’ombre d’une transition, soudain la mesure du temps devenant au lieu de quarts d’heure, des années, des décades». Eh bien cet «abîme» qui s’ouvre et nous laisse justement contempler, amer, la folie d’une vie qui s’est écoulée avec fulgurance et qui contenait, avec le recul, beaucoup plus de vide que de matière – c’est le sentiment qui surnage ici.