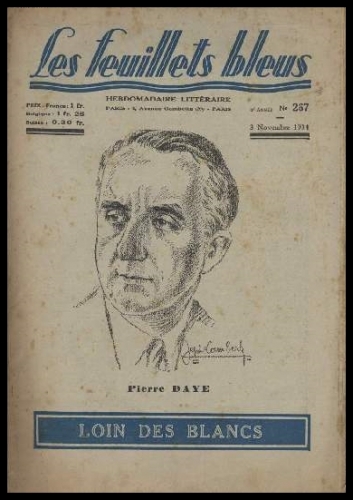

Pierre Daye, un esthète dans la tourmente

par Christophe Dolbeau

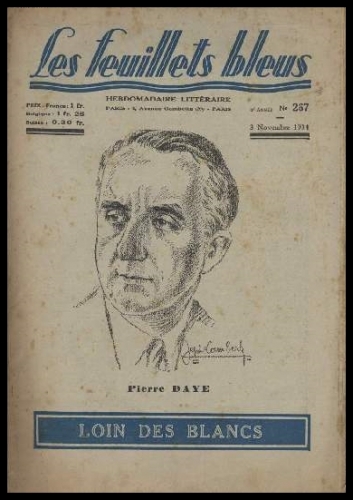

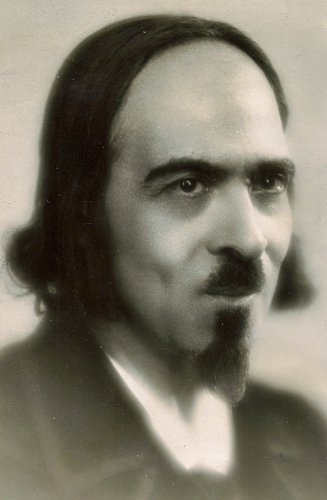

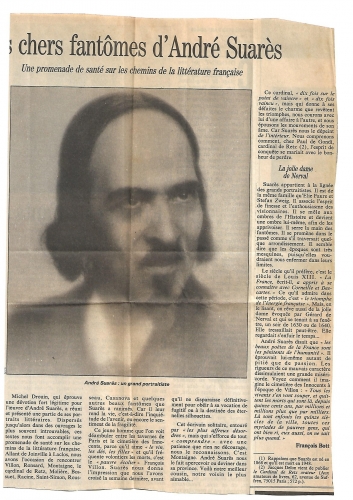

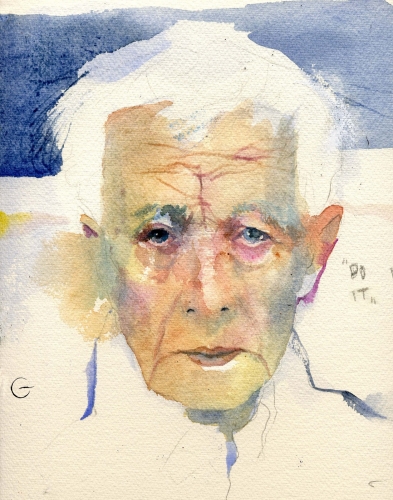

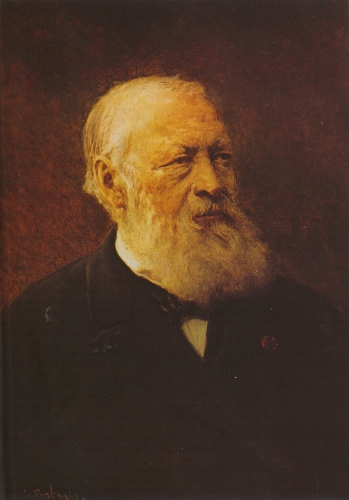

Lorsque le 28 février 1960, le très discret Pierre Daye s’est éteint à Buenos-Aires, très peu de Belges se souvenaient probablement de lui. Et pourtant ce Porteño d’adoption avait été l’un des journalistes européens les plus brillants de la première moitié du XXe siècle, ainsi qu’un protagoniste majeur de la vie politique bruxelloise d’avant-guerre. Grand reporter à la façon d’un Albert Londres, d’un Paul Morand ou d’un Henri Béraud, brillant causeur et plaisant conférencier, il avait également été député et avait même occupé des fonctions gouvernementales sous l’Occupation. Effacé de la mémoire collective comme des annales littéraires belges, ce personnage aux multiples facettes mérite amplement, 60 ans après sa disparition, de sortir du purgatoire.

Un globe-trotter

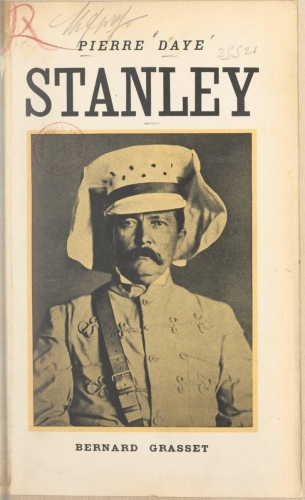

C’est dans une famille très bourgeoise de Schaerbeek, l’une des communes de Bruxelles, que Pierre Daye vient au monde le 24 juin 1892. Scolarisé chez les pères jésuites du Collège Saint-Michel, il se voit offrir, dès l’enfance, la possibilité de faire plusieurs beaux voyages. À une époque où l’on circule bien moins qu’aujourd’hui, le jeune Pierre découvre Venise (août 1901), la Bretagne et les pistes de ski de Kandersteg (1904). Il assiste même à une audience du Pape Saint Pie X. À 17 ans, il passe des vacances à Tanger (1909) puis intègre l’Institut Saint-Louis où il va suivre deux années de droit. Appelé ensuite sous les drapeaux, il se trouve donc fin prêt, en juillet 1914, pour répondre à la mobilisation générale. Le jeune homme prend part aux batailles de Namur, d’Anvers et de l’Yser, puis son goût pour l’exotisme le conduit à se porter volontaire pour rejoindre, en Afrique, les troupes du général Charles Tombeur (1867-1947). Ces unités (la Force publique congolaise) se battent contre le célèbre général allemand Paul Emil von Lettow-Vorbeck (1870-1964). Mitrailleur, Pierre Daye participe à la prise de Tabora (19 septembre 1916), le principal fait d’armes des bataillons belges. Il consacrera plus tard un livre à cette épopée tropicale (1). Promu officier mais sévèrement atteint par la malaria, il est alors rapatrié en Europe. Au terme de sa convalescence, le conflit n’est pas achevé, ce qui lui vaut d’effectuer encore une dernière mission, nettement moins périlleuse celle-là : assurer, à Washington, la promotion de la Belgique, en qualité d’attaché militaire adjoint. C’est à ce titre qu’il est reçu, en décembre 1918, par le président cubain García Menocal (1866-1941). De son séjour américain, il tirera matière à un livre, Sam ou le voyage dans l’optimiste Amérique, qui paraîtra en 1922.

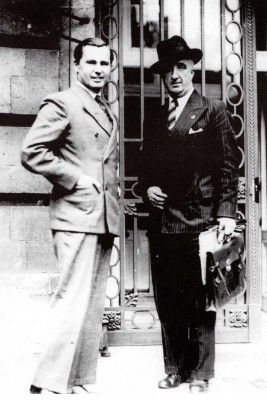

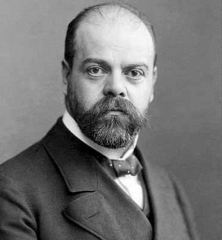

Pierre Daye, officier de la "Force publique" congolaise.

Rendu à la vie civile en 1919, Pierre Daye s’intéresse dès lors aux joutes politiques. Membre de la Ligue de la Renaissance nationale, où il côtoie Pierre Nothomb (2), l’aviateur Edmond Thieffry (3) et le peintre Delville (4), il en est candidat suppléant lors des élections de novembre 1919. On le trouve ensuite au Comité de politique nationale, un groupe qui milite, sous la houlette de Pierre Nothomb, pour « la plus grande Belgique », et il collabore à l’hebdomadaire La Politique (1921). Très sédentaire, cette activité n’est toutefois pas à même de le retenir bien longtemps car, au fond, sa véritable passion, ce sont les voyages. Dès 1922, il embarque donc sur l’Élisabethville et repart pour l’Afrique : durant plusieurs mois, il sillonne le Congo, en voiture, en train, à pied ou en « typoï » (chaise à porteurs), et navigue sur le lac Tanganyika. Puis, avant de rentrer en métropole, il fait un crochet par l’Union sud-africaine où il s’entretient avec le Premier ministre Jan Smuts.

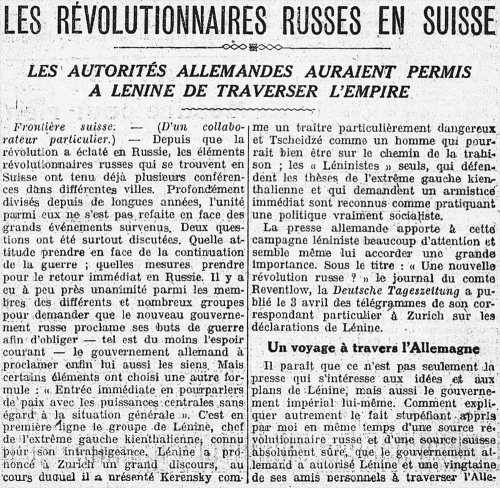

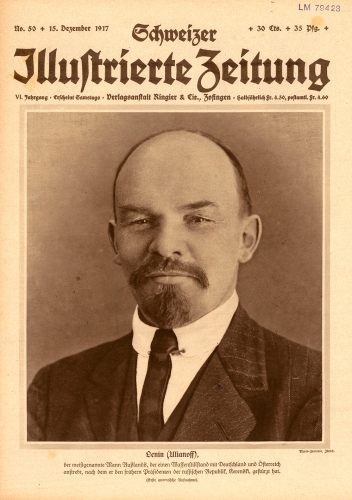

Embauché comme reporter par le grand quotidien Le Soir, il va désormais multiplier les expéditions les plus lointaines et les entrevues exclusives. En une quinzaine d’années, ses pérégrinations vont l’emmener aux quatre coins de l’univers et lui permettre de rencontrer un nombre incroyable de personnalités de premier plan. Après le Congo (où il retournera plusieurs fois), Pierre Daye visite ainsi le Maroc, où il s’entretient avec le sultan Moulay Youssef (1881-1927), les Balkans, où il est reçu par le Premier ministre bulgare Alexandre Tsankov (1879-1959), et l’Argentine, où il se rend, en 1925, en faisant le subrécargue sur un modeste cargo. Après Buenos-Aires, où il se lie avec l’écrivain nationaliste Leopoldo Lugones (1874-1938), il traverse la Cordillière des Andes et découvre le Chili, puis se rend en Uruguay et au Brésil. En 1926, il est à Moscou, approche Léon Trotsky, Leonid Krassine (5) et Maxime Litvinov (6), puis passe par la Pologne et s’y entretient avec Sikorski (7), avant de regagner Bruxelles pour y faire rapport au roi Albert Ier. D’autres expéditions le conduisent en Angola, en Nubie mais aussi au Maroc espagnol, où il rencontre le général Primo de Rivera, et en Asie qu’il visite en qualité de chargé de mission. Après une escale à Ceylan, il passe par les Indes britanniques, la Malaisie, Sumatra, le Japon, la Chine et la Mandchourie. Dans l’Empire du Milieu, il va voir les tombes des Mings, rencontre Pou-yi (8) et obtient une entrevue avec le président Tchang Tso-lin (9). D’une curiosité insatiable, Pierre Daye effectue ensuite un tour du monde par les îles, périple original qui le conduit au Cap Vert, aux Antilles, à Panama, à Tahiti, aux îles Fidji, aux Nouvelles-Hébrides, en Nouvelle-Calédonie, en Australie et à Java. Il va sans dire que toutes ces étapes donnent naissance à autant d’articles ou de livres captivants (10). Notre impénitent voyageur connaît également bien Constantinople et le Moyen-Orient. Passé par la Syrie, la Palestine et Jérusalem, il séjourne assez longuement en Égypte (1931), ce qui lui permet de visiter Memphis (avec le peintre Herman Richir), Thèbes, Abou Simbel et le temple d’Edfou.

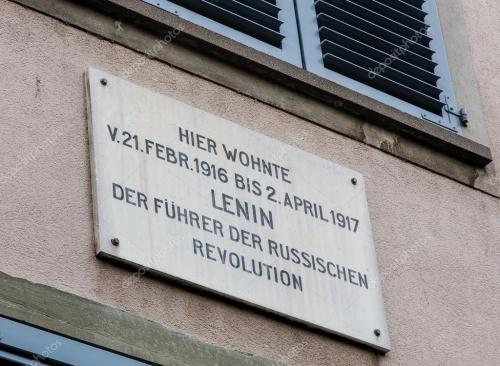

Embauché comme reporter par le grand quotidien Le Soir, il va désormais multiplier les expéditions les plus lointaines et les entrevues exclusives. En une quinzaine d’années, ses pérégrinations vont l’emmener aux quatre coins de l’univers et lui permettre de rencontrer un nombre incroyable de personnalités de premier plan. Après le Congo (où il retournera plusieurs fois), Pierre Daye visite ainsi le Maroc, où il s’entretient avec le sultan Moulay Youssef (1881-1927), les Balkans, où il est reçu par le Premier ministre bulgare Alexandre Tsankov (1879-1959), et l’Argentine, où il se rend, en 1925, en faisant le subrécargue sur un modeste cargo. Après Buenos-Aires, où il se lie avec l’écrivain nationaliste Leopoldo Lugones (1874-1938), il traverse la Cordillière des Andes et découvre le Chili, puis se rend en Uruguay et au Brésil. En 1926, il est à Moscou, approche Léon Trotsky, Leonid Krassine (5) et Maxime Litvinov (6), puis passe par la Pologne et s’y entretient avec Sikorski (7), avant de regagner Bruxelles pour y faire rapport au roi Albert Ier. D’autres expéditions le conduisent en Angola, en Nubie mais aussi au Maroc espagnol, où il rencontre le général Primo de Rivera, et en Asie qu’il visite en qualité de chargé de mission. Après une escale à Ceylan, il passe par les Indes britanniques, la Malaisie, Sumatra, le Japon, la Chine et la Mandchourie. Dans l’Empire du Milieu, il va voir les tombes des Mings, rencontre Pou-yi (8) et obtient une entrevue avec le président Tchang Tso-lin (9). D’une curiosité insatiable, Pierre Daye effectue ensuite un tour du monde par les îles, périple original qui le conduit au Cap Vert, aux Antilles, à Panama, à Tahiti, aux îles Fidji, aux Nouvelles-Hébrides, en Nouvelle-Calédonie, en Australie et à Java. Il va sans dire que toutes ces étapes donnent naissance à autant d’articles ou de livres captivants (10). Notre impénitent voyageur connaît également bien Constantinople et le Moyen-Orient. Passé par la Syrie, la Palestine et Jérusalem, il séjourne assez longuement en Égypte (1931), ce qui lui permet de visiter Memphis (avec le peintre Herman Richir), Thèbes, Abou Simbel et le temple d’Edfou.

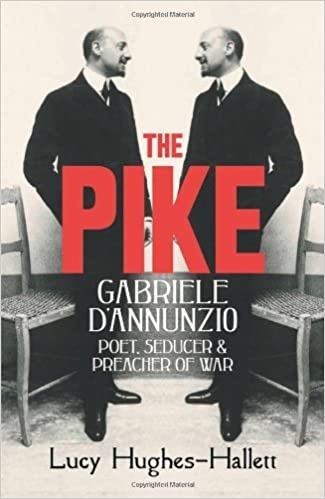

Ajoutons encore à la liste de ses voyages mémorables, la traversée de la Sibérie par 30° au-dessous de zéro, et un séjour en Perse qui lui offre l’occasion de converser avec Reza Chah Pahlavi. Son goût affirmé pour les contrées lointaines ne l’empêche pas d’apprécier aussi les découvertes européennes. Angleterre, Portugal, Italie, Autriche, Hongrie et pays scandinaves n’ont guère de secrets pour lui ; en août 1932, il est même en Lituanie, à Nida, où l’a invité Thomas Mann, tandis qu’en 1935, il visite les Pays-Bas et l’Allemagne en compagnie de Pierre Gaxotte. À Berlin, les deux hommes auront l’occasion d’échanger quelques propos avec Ribbentrop et Otto Abetz. Aventurier dans l’âme, Pierre Daye ne se contente pas de flâner nonchalamment mais il n’hésite pas, le cas échéant, à se rendre sur le théâtre de certains conflits : on le verra par exemple, en pleine guerre civile espagnole, faire la tournée des lignes de front avec Gaxotte et José Félix de Lequerica (11).

Ajoutons encore à la liste de ses voyages mémorables, la traversée de la Sibérie par 30° au-dessous de zéro, et un séjour en Perse qui lui offre l’occasion de converser avec Reza Chah Pahlavi. Son goût affirmé pour les contrées lointaines ne l’empêche pas d’apprécier aussi les découvertes européennes. Angleterre, Portugal, Italie, Autriche, Hongrie et pays scandinaves n’ont guère de secrets pour lui ; en août 1932, il est même en Lituanie, à Nida, où l’a invité Thomas Mann, tandis qu’en 1935, il visite les Pays-Bas et l’Allemagne en compagnie de Pierre Gaxotte. À Berlin, les deux hommes auront l’occasion d’échanger quelques propos avec Ribbentrop et Otto Abetz. Aventurier dans l’âme, Pierre Daye ne se contente pas de flâner nonchalamment mais il n’hésite pas, le cas échéant, à se rendre sur le théâtre de certains conflits : on le verra par exemple, en pleine guerre civile espagnole, faire la tournée des lignes de front avec Gaxotte et José Félix de Lequerica (11).

Un homme du monde

Chroniqueur réputé et homme du monde, Pierre Daye est également un habitué des dîners en ville où ses commensaux sont généralement des personnes de qualité. On l’apercevra ainsi à la table du maréchal Joffre ou à celle de Raymond Poincaré. Ami de Pierre Gaxotte (qui le fera bientôt entrer à Je suis partout), il est également lié au poète Éric de Haulleville, à Pierre Drieu la Rochelle, Maurice Mæterlinck et Georges Remi (Hergé). Sa popularité de journaliste et ses talents de causeur en font par ailleurs l’un des hôtes les plus réguliers des salons à la mode de la capitale belge. Membre assidu du très chic Cercle Gaulois, que fréquentent André Tardieu, Paul Claudel ou Pierre Benoit, il est aussi l’un des convives attitrés des dîners que donne Isabelle Errera (Goldschmidt), des soirées de prestige qu’organise Madame Jules Destrée, ou encore des réunions qu’orchestre la belle Lucienne Didier (Bauwens). Très éclectiques, ces rendez-vous accueillent aussi bien des notables de gauche, comme Henri De Man (12) et Paul-Henri Spaak (13), que des intellectuels de droite, comme Louis Carette (le futur Félicien Marceau), Brasillach, Montherlant et Fabre-Luce, ou des penseurs indépendants, comme Emmanuel Mounier (14). Dans les années 1930, il n’est pas excessif de dire que Daye est un homme arrivé. Un peu sarcastique, Jean-Léo le présente ainsi : « Grand bourgeois catholique, un peu précieux, toujours habillé avec recherche (sauf quand il pratique le nudisme), il affectionne les cravates club et ne fume que des ‘Abdalla’ à bout doré » (15). « Gentleman globe-trotter », précise-t-il encore, « habitué des sleepings, des paquebots, des palaces et des restaurants quatre étoiles (…) il est un peu boudé par la bonne société qui lui reproche ‘des mœurs dissolues’ (L’expression, à une époque où l’on ne s’éclate pas encore dans les Gay pride, désigne son homosexualité que Marcel Antoine, dans ses caricatures, suggère en le représentant jouant du bilboquet » (16). Confirmant ce portrait, l’historien Jean-Michel Etienne ajoute que l’homme est sans conteste intelligent et bon connaisseur des milieux diplomatiques belges et étrangers (17).

Disons aussi que si Pierre Daye est effectivement familier de la haute société, il ne succombe jamais à ce miroir aux alouettes qu’il observe un peu comme une sorte d’entomologiste. Parlant des « gens du monde », voici d’ailleurs ce qu’il en dit : « … vains, souvent paresseux, certains ont pour excuse sinon leur fortune, tout au moins leur culture ou leur goût, qui sont parfois réels. Snobs, comme on dit, ils se nourrissent néanmoins d’idées toutes faites, à condition qu’elles soient à la mode (…) On trouve chez eux, souvent, de l’élégance extérieure, du brillant, du charme, ce que l’on a appelé la douceur de vivre, et parfois du comique involontaire. C’est pourquoi je les ai beaucoup fréquentés, et ils m’ont beaucoup amusé. À condition de les juger pour ce qu’ils sont et de ne rien leur demander, les gens du monde apparaissent d’un utile et agréable commerce pour un célibataire qui se pique d’être en même temps un observateur professionnel » (18)

Au demeurant, il serait injuste et inexact de ne voir en Pierre Daye qu’un voyageur nanti et un mondain frivole : il s’agit aussi et surtout d’un écrivain talentueux dont les nombreux livres se vendent très bien. Auteur de multiples récits de voyage (19), il a également consacré plusieurs ouvrages aux souverains belges (20), ainsi que plusieurs essais à l’Afrique (21). Dans la première partie de sa vie, il a, en revanche, peu abordé la politique dans ses livres, et lorsqu’il l’a fait, ce fut plutôt sous l’angle de la politique étrangère (22). Il s’est par ailleurs peu intéressé à la fiction, sinon sous la forme de quelques nouvelles et contes. L’un de ceux-ci, Daïnah, la métisse (1932), sera même adapté au cinéma par Jean Grémillon (avec Charles Vanel dans l’un des rôles principaux).

Au demeurant, il serait injuste et inexact de ne voir en Pierre Daye qu’un voyageur nanti et un mondain frivole : il s’agit aussi et surtout d’un écrivain talentueux dont les nombreux livres se vendent très bien. Auteur de multiples récits de voyage (19), il a également consacré plusieurs ouvrages aux souverains belges (20), ainsi que plusieurs essais à l’Afrique (21). Dans la première partie de sa vie, il a, en revanche, peu abordé la politique dans ses livres, et lorsqu’il l’a fait, ce fut plutôt sous l’angle de la politique étrangère (22). Il s’est par ailleurs peu intéressé à la fiction, sinon sous la forme de quelques nouvelles et contes. L’un de ceux-ci, Daïnah, la métisse (1932), sera même adapté au cinéma par Jean Grémillon (avec Charles Vanel dans l’un des rôles principaux).

Député rexiste

Dans les années 1930, la politique, qu’il avait autrefois délaissée au profit des voyages, l’attire de nouveau. Secrétaire du socialiste Jules Destrée, Daye se refuse toutefois à rallier le Parti Ouvrier Belge (POB). En fait, il se range parmi les conservateurs « éclairés » : membre (depuis 1926) de l’Union paneuropéenne, il se montre sensible aux questions sociales, mais à la façon des catholiques, et reste très fidèle au roi comme à l’unité nationale. Partisan de la colonisation et hostile à une émancipation rapide du Congo, il n’est cependant absolument pas raciste et ne témoigne d’aucune hostilité de principe à l’égard des Noirs. Dès 1921 et dans un article consacré au mouvement « pan-nègre » (23), il souligne qu’ « il serait vain de croire que la suprématie de la race blanche pourra se maintenir intacte », proclame que « les préjugés de race sont absurdes » et s’affirme partisan « des généreuses idées de collaboration des races ». À propos des Africains, il déclare : « Nous sommes les premiers à vouloir que le sort de la race noire soit amélioré ; que là où des abus existent, ils soient redressés ; que l’on s’occupe de l’éducation, de la formation intellectuelle et – par après – de la liberté des nègres. Mais il faut procéder avec ordre ». Car, ajoute-t-il, « il nous faut veiller à ce qu’au nom de principes sentimentaux, on n’aille pas saper notre autorité en Afrique ». Si nous insistons quelque peu sur ces opinions, disons paternalistes, de Pierre Daye, c’est afin de mieux souligner toute l’absurdité qu’il y a à le qualifier de « nazi » comme d’aucuns le feront un jour…

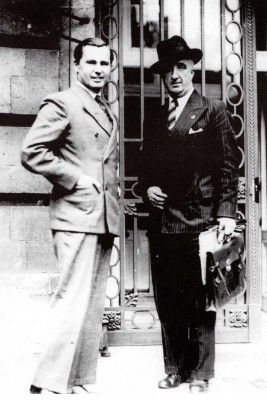

Désireux de descendre dans l’arène pour y défendre ses idées catholiques, sociales et nationales, Pierre Daye découvre en 1935 le nouveau phénomène politique qu’est Léon Degrelle. Le 24 janvier, il le voit, pour la première fois, à Louvain où le jeune orateur l’impressionne beaucoup. « J’attendais depuis plusieurs années », racontera-t-il, « que se manifestât dans mon pays un effet de ce grand mouvement européen dont j’avais découvert en tant de nations les signes tangibles » (24). Séduit, l’écrivain n’est pas long à rejoindre les rangs de Rex où il siège d’emblée au Conseil politique (mais pas au Bureau exécutif). Aux élections du 24 mai 1936, le mouvement, qui a le vent en poupe, obtient du premier coup 33 élus (21 députés et 12 sénateurs). « Nous étions partis, nous pouvons bien le dire », se souvient-il, « sans aucun moyen ; nous n’avions pas d’argent, aucune expérience, très peu d’hommes, pas de journaux. Mais nous avions la foi. Et la jeunesse aussi… » (25). Et le 27 mai, dans les colonnes du Pays réel, le nouveau député bruxellois se montre plus laudatif encore, affirmant entre autres que « Léon Degrelle est devenu l’interprète de tout ce qui, dans la nation, est jeune, vivant, audacieux, tourné vers l’avenir » (26). L’Assemblée que découvre Pierre Daye n’a rien de bien attrayant : selon lui, « les trucs, les combinaisons, l’intérêt personnel, la stérilité, la suffisance, la vulgarité, tels étaient quelques-uns des traits que révélait l’examen de l’institution parlementaire » (27). Il semble néanmoins tout à fait décidé à jouer le jeu et à faire sérieusement son travail de député. Placé à la tête du groupe parlementaire, il s’efforce donc, en premier lieu, de discipliner ses collègues rexistes qui font souvent preuve d’une nonchalance et d’un amateurisme consternants. Auteur d’un projet de loi réduisant la durée du service militaire, il s’exprime aussi au sein de la Commission des Colonies et de celle des Affaires Étrangères où il plaide fougueusement pour l’Espagne nationaliste. Assez proche du chef, il est souvent associé aux grandes manœuvres de ce dernier. En septembre 1936, par exemple, il est aux côtés de Degrelle lorsque celui-ci est reçu par Hitler (invité par Rudolf Hess, il profite du déplacement pour assister au 8e congrès de Nuremberg). C’est par ailleurs autour de la table de Pierre Daye que se nouent certains contacts discrets entre des gens comme Gustave Sap (28), Hendrik Borginon (29), Gérard Romsée (30), Joris van Severen (31), Charles-Albert d’Aspremont-Lynden (32), et Léon Degrelle. Plus tard, et au grand dam du Quai d’Orsay, il demandera la dénonciation de l’accord militaire franco-belge, ainsi que des accords de Locarno (33).

Désireux de descendre dans l’arène pour y défendre ses idées catholiques, sociales et nationales, Pierre Daye découvre en 1935 le nouveau phénomène politique qu’est Léon Degrelle. Le 24 janvier, il le voit, pour la première fois, à Louvain où le jeune orateur l’impressionne beaucoup. « J’attendais depuis plusieurs années », racontera-t-il, « que se manifestât dans mon pays un effet de ce grand mouvement européen dont j’avais découvert en tant de nations les signes tangibles » (24). Séduit, l’écrivain n’est pas long à rejoindre les rangs de Rex où il siège d’emblée au Conseil politique (mais pas au Bureau exécutif). Aux élections du 24 mai 1936, le mouvement, qui a le vent en poupe, obtient du premier coup 33 élus (21 députés et 12 sénateurs). « Nous étions partis, nous pouvons bien le dire », se souvient-il, « sans aucun moyen ; nous n’avions pas d’argent, aucune expérience, très peu d’hommes, pas de journaux. Mais nous avions la foi. Et la jeunesse aussi… » (25). Et le 27 mai, dans les colonnes du Pays réel, le nouveau député bruxellois se montre plus laudatif encore, affirmant entre autres que « Léon Degrelle est devenu l’interprète de tout ce qui, dans la nation, est jeune, vivant, audacieux, tourné vers l’avenir » (26). L’Assemblée que découvre Pierre Daye n’a rien de bien attrayant : selon lui, « les trucs, les combinaisons, l’intérêt personnel, la stérilité, la suffisance, la vulgarité, tels étaient quelques-uns des traits que révélait l’examen de l’institution parlementaire » (27). Il semble néanmoins tout à fait décidé à jouer le jeu et à faire sérieusement son travail de député. Placé à la tête du groupe parlementaire, il s’efforce donc, en premier lieu, de discipliner ses collègues rexistes qui font souvent preuve d’une nonchalance et d’un amateurisme consternants. Auteur d’un projet de loi réduisant la durée du service militaire, il s’exprime aussi au sein de la Commission des Colonies et de celle des Affaires Étrangères où il plaide fougueusement pour l’Espagne nationaliste. Assez proche du chef, il est souvent associé aux grandes manœuvres de ce dernier. En septembre 1936, par exemple, il est aux côtés de Degrelle lorsque celui-ci est reçu par Hitler (invité par Rudolf Hess, il profite du déplacement pour assister au 8e congrès de Nuremberg). C’est par ailleurs autour de la table de Pierre Daye que se nouent certains contacts discrets entre des gens comme Gustave Sap (28), Hendrik Borginon (29), Gérard Romsée (30), Joris van Severen (31), Charles-Albert d’Aspremont-Lynden (32), et Léon Degrelle. Plus tard, et au grand dam du Quai d’Orsay, il demandera la dénonciation de l’accord militaire franco-belge, ainsi que des accords de Locarno (33).

Dévoué mais exigeant, Pierre Daye va vite se lasser des carences profondes du groupe parlementaire rexiste dont il abandonne d’ailleurs la présidence dès juin 1937. Cela ne l’empêche cependant pas de continuer son travail à la Chambre. Dans le même temps, il poursuit son activité de chroniqueur et d’essayiste. En octobre 1936, il joue un rôle clef dans la parution d’un numéro spécial de Je suis partout entièrement consacré à Rex, avec une « Lettre aux Français » de Léon Degrelle et des articles de Serge Doring, Carlos Leruitte et Lucien Rebatet [La même année, Robert Brasillach fait paraître Léon Degrelle et l’avenir de Rex (Plon) et l’année suivante (3 novembre 1937), il dédiera toute une page de Je suis partout au mouvement belge]. Régulièrement présent dans les colonnes de l’hebdomadaire parisien, Pierre Daye signe également, en 1937, un livre sur Léon Degrelle et le rexisme (Fayard), suivi en 1938 d’une Petite histoire parlementaire belge. Malgré cet engagement sans faille, les erreurs répétées de Rex et de son chef finissent toutefois par user sa patience. Ce désenchantement le conduit même, en 1939, à refuser de se représenter aux élections et à quitter le mouvement. Le 10 mars, il prend donc définitivement congé du groupe parlementaire et se tourne dès lors vers le parti catholique où il a conservé nombre d’amis. Il s’en va, certes, mais demeure en excellents termes avec Degrelle, ce que la suite des événements ne va pas tarder à démontrer.

Dévoué mais exigeant, Pierre Daye va vite se lasser des carences profondes du groupe parlementaire rexiste dont il abandonne d’ailleurs la présidence dès juin 1937. Cela ne l’empêche cependant pas de continuer son travail à la Chambre. Dans le même temps, il poursuit son activité de chroniqueur et d’essayiste. En octobre 1936, il joue un rôle clef dans la parution d’un numéro spécial de Je suis partout entièrement consacré à Rex, avec une « Lettre aux Français » de Léon Degrelle et des articles de Serge Doring, Carlos Leruitte et Lucien Rebatet [La même année, Robert Brasillach fait paraître Léon Degrelle et l’avenir de Rex (Plon) et l’année suivante (3 novembre 1937), il dédiera toute une page de Je suis partout au mouvement belge]. Régulièrement présent dans les colonnes de l’hebdomadaire parisien, Pierre Daye signe également, en 1937, un livre sur Léon Degrelle et le rexisme (Fayard), suivi en 1938 d’une Petite histoire parlementaire belge. Malgré cet engagement sans faille, les erreurs répétées de Rex et de son chef finissent toutefois par user sa patience. Ce désenchantement le conduit même, en 1939, à refuser de se représenter aux élections et à quitter le mouvement. Le 10 mars, il prend donc définitivement congé du groupe parlementaire et se tourne dès lors vers le parti catholique où il a conservé nombre d’amis. Il s’en va, certes, mais demeure en excellents termes avec Degrelle, ce que la suite des événements ne va pas tarder à démontrer.

La catastrophe de 1940

À nouveau libre de ses initiatives et très hostile à l’idée d’un nouveau conflit avec l’Allemagne, Pierre Daye s’associe, le 23 septembre 1939, au manifeste des intellectuels (34) « pour la neutralité belge, contre l’éternisation de la guerre européenne et pour la défense des valeurs de l’esprit ». Le texte paraît le 29 septembre dans la Revue catholique des idées et des faits, puis dans Cassandre, le Pays réel, les Cahiers franco-allemands, et ses treize signataires se voient aussitôt interdire l’accès au territoire français. En décembre, Daye rejoint Robert Poulet, Hergé, Gaston Derijcke (Claude Elsen) et Raymond De Becker, au nouvel hebdomadaire L’Ouest qui se veut le prolongement du manifeste. La France, la Grande-Bretagne et l’Allemagne étant entrées en guerre le 3 septembre, la situation devient dès lors chaotique en Belgique où partis politiques et ministres ne parviennent pas à faire des choix clairs et consensuels.

Et puis survient soudain le cataclysme, avec l’attaque allemande du 10 mai 1940 et la débandade quasi immédiate du gouvernement belge. Avant de filer vers Paris, Poitiers, Limoges ou Vichy, les autorités ont tout de même fait appréhender tous ceux qu’elles soupçonnent – à tort le plus souvent – d’appartenir à la cinquième colonne. Averti de l’arrestation de nombre de ses amis mais épargné par la première rafle, Pierre Daye juge dès lors prudent de s’éloigner au plus vite de Bruxelles. Accompagné de son neveu, Jacques Lesigne, il part donc, le 12 mai, pour La Panne, dans le but de trouver asile en France. Refoulé car il ne possède pas les visas nécessaires, il parvient cependant, le 14 mai, à franchir la frontière à Poperinghe et à filer vers Eu. Après une étape de cinq jours à Lisieux, il reprend la route, le 20 mai, traverse Nantes et atteint La Rochelle où son ami Pierre Bonardi (35) lui offre le vivre et le couvert. Le 24 mai, il pousse encore jusqu’à la périphérie de Bordeaux, laisse son neveu à Libourne, puis rebrousse chemin et regagne La Rochelle où les Bonardi le dirigent vers l’île de Ré où ils possèdent un moulin.

Daye va donc séjourner plusieurs semaines à Saint-Clément-des-Baleines. Loin des combats, il fait de la bicyclette, se balade avec Henri Béraud et aperçoit de temps en temps Suzy Solidor ou le peintre Paul Colin. Cette paisible villégiature s’achève toutefois vers la fin juin car avec l’armistice, le journaliste souhaite désormais rentrer chez lui. Le 8 juillet 1940, il remonte donc sur Paris, s’y arrête le temps de voir Jean Chiappe, puis regagne Bruxelles. Informé du massacre d’Abbeville (36) et du décès de Léon Degrelle, le journaliste ne tarde pas à réapparaître à Paris où l’ambassadeur Abetz, une vieille connaissance, lui apprend incidemment que Degrelle n’est absolument pas mort, mais probablement interné dans un camp du sud de la France. En dépit des divergences politiques qui ont pu opposer les deux hommes, Daye estime alors de son devoir de se porter au secours du chef de Rex et part aussitôt à sa recherche. Accompagné de Jacques Crokaert et Carl Doutreligne, il file à Vichy, rencontre Adrien Marquet mais aussi plusieurs ministres belges en déréliction… L’administration française n’ayant pas mis longtemps à localiser Degrelle qui se trouve dans l’Ariège, au camp du Vernet, le trio de sauveteurs (« mes trois mousquetaires » dira Degrelle dans La cohue de 40) s’empresse de reprendre la route. Quelques heures plus tard, ils sont à Carcassonne où ils retrouvent enfin Léon Degrelle, « sale, amaigri, méconnaissable » (37), ainsi que l’ex-député rexiste Gustave Wyns.

Daye va donc séjourner plusieurs semaines à Saint-Clément-des-Baleines. Loin des combats, il fait de la bicyclette, se balade avec Henri Béraud et aperçoit de temps en temps Suzy Solidor ou le peintre Paul Colin. Cette paisible villégiature s’achève toutefois vers la fin juin car avec l’armistice, le journaliste souhaite désormais rentrer chez lui. Le 8 juillet 1940, il remonte donc sur Paris, s’y arrête le temps de voir Jean Chiappe, puis regagne Bruxelles. Informé du massacre d’Abbeville (36) et du décès de Léon Degrelle, le journaliste ne tarde pas à réapparaître à Paris où l’ambassadeur Abetz, une vieille connaissance, lui apprend incidemment que Degrelle n’est absolument pas mort, mais probablement interné dans un camp du sud de la France. En dépit des divergences politiques qui ont pu opposer les deux hommes, Daye estime alors de son devoir de se porter au secours du chef de Rex et part aussitôt à sa recherche. Accompagné de Jacques Crokaert et Carl Doutreligne, il file à Vichy, rencontre Adrien Marquet mais aussi plusieurs ministres belges en déréliction… L’administration française n’ayant pas mis longtemps à localiser Degrelle qui se trouve dans l’Ariège, au camp du Vernet, le trio de sauveteurs (« mes trois mousquetaires » dira Degrelle dans La cohue de 40) s’empresse de reprendre la route. Quelques heures plus tard, ils sont à Carcassonne où ils retrouvent enfin Léon Degrelle, « sale, amaigri, méconnaissable » (37), ainsi que l’ex-député rexiste Gustave Wyns.

Au cœur des intrigues

La petite troupe ne s’attarde pas dans l’Aude et remonte aussitôt vers Paris où une brève escale permet à Degrelle de remercier Abetz et de s’entretenir avec Fernand de Brinon. De retour à Bruxelles le 30 août, Pierre Daye reçoit bientôt la visite du comte Robert Capelle auquel il relate la triste épopée de Degrelle. À cette occasion, le secrétaire du roi lui fait part de la position circonspecte et réservée du souverain, et lui conseille de collaborer à la presse. « Le patriotisme », énonce-t-il, « commande que les patriotes s’emparent des journaux, au lieu de les laisser à d’autres » (38). Là-dessus, Daye effectue un nouveau séjour à Paris, sa terre d’élection. Le 7 août 1940, il présente Degrelle à Pierre Laval, puis déjeune avec Bertrand de Jouvenel, et dîne un soir avec Abetz, Degrelle et Henri de Man. Le 12 août, enfin, il est chez le comte de Beaumont où il passe la soirée en compagnie de Pierre Drieu la Rochelle, avant de regagner Bruxelles.

Loin d’être le pestiféré qu’il deviendra bientôt, Pierre Daye conserve en cette époque troublée de nombreuses relations mondaines : il organise, chez lui, une rencontre entre le comte Capelle et le chef de Rex, dîne avec les frères Heymans (dont l’un, Corneille, est prix Nobel) et séjourne au Zoute, chez le banquier Wauters. Invité chez le vicomte Jacques Duvignon, ancien ambassadeur à Berlin, il revoit également Mme Destrée et Robert Poulet, tandis que lors d’un enième séjour à Paris, il croise Alphonse de Chateaubriant (qui l’accueille dans les locaux de La Gerbe), Bernard Grasset, l’historien Pierre Bessand-Massenet et Stanislas de la Rochefoucauld. Si, en dépit des circonstances, Pierre Daye est quelqu’un qui demeure attaché aux petits plaisirs de la vie et aux relations sociales, il serait erroné de ne voir en lui qu’un second couteau falot et superficiel. En fait, il sert de passerelle entre beaucoup d’acteurs importants du jeu politico-diplomatique et maintient notamment d’étroits contacts avec les proches du roi. En relation avec les secrétaires du souverain, il voit aussi, très régulièrement, les anciens ministres Maurice Lippens et Henri De Man, ainsi que le général Van Overstræten, aide-de-camp de Léopold III. Pour le palais royal, Daye est donc une précieuse source de renseignements : « Je servis bien souvent d’informateur au souverain », écrit-il, « et le bloc-notes en main, le comte Capelle prenait des indications ‘pour sa Majesté’ durant la plupart de nos entretiens » (39). Il facilite par ailleurs certains contacts improbables comme cette entrevue, chez lui, le 22 mai 1943, entre Capelle et l’abbé Louis Fierens, l’aumônier (non rexiste) de la Légion Wallonie… Aucun reproche, explicite ou implicite, ne lui ayant jamais été exprimé, le journaliste s’étonnera plus tard des accusations de félonie formulées à son encontre : « Pouvais-je n’être pas convaincu », demande-t-il dans ses mémoires, « après tous mes rapports plus ou moins directs avec lui (le roi), par l’intermédiaire de son entourage, que ma conduite était approuvée ? Ou que tout au moins, elle n’était pas blamée ? » (40). Et pour être encore plus clair, il ajoute : « Si des ‘collaborationnistes’ sincères se trompaient, Léopold III aurait dû les avertir, ou les faire avertir, même au risque de déplaire aux Allemands » (41).

Loin d’être le pestiféré qu’il deviendra bientôt, Pierre Daye conserve en cette époque troublée de nombreuses relations mondaines : il organise, chez lui, une rencontre entre le comte Capelle et le chef de Rex, dîne avec les frères Heymans (dont l’un, Corneille, est prix Nobel) et séjourne au Zoute, chez le banquier Wauters. Invité chez le vicomte Jacques Duvignon, ancien ambassadeur à Berlin, il revoit également Mme Destrée et Robert Poulet, tandis que lors d’un enième séjour à Paris, il croise Alphonse de Chateaubriant (qui l’accueille dans les locaux de La Gerbe), Bernard Grasset, l’historien Pierre Bessand-Massenet et Stanislas de la Rochefoucauld. Si, en dépit des circonstances, Pierre Daye est quelqu’un qui demeure attaché aux petits plaisirs de la vie et aux relations sociales, il serait erroné de ne voir en lui qu’un second couteau falot et superficiel. En fait, il sert de passerelle entre beaucoup d’acteurs importants du jeu politico-diplomatique et maintient notamment d’étroits contacts avec les proches du roi. En relation avec les secrétaires du souverain, il voit aussi, très régulièrement, les anciens ministres Maurice Lippens et Henri De Man, ainsi que le général Van Overstræten, aide-de-camp de Léopold III. Pour le palais royal, Daye est donc une précieuse source de renseignements : « Je servis bien souvent d’informateur au souverain », écrit-il, « et le bloc-notes en main, le comte Capelle prenait des indications ‘pour sa Majesté’ durant la plupart de nos entretiens » (39). Il facilite par ailleurs certains contacts improbables comme cette entrevue, chez lui, le 22 mai 1943, entre Capelle et l’abbé Louis Fierens, l’aumônier (non rexiste) de la Légion Wallonie… Aucun reproche, explicite ou implicite, ne lui ayant jamais été exprimé, le journaliste s’étonnera plus tard des accusations de félonie formulées à son encontre : « Pouvais-je n’être pas convaincu », demande-t-il dans ses mémoires, « après tous mes rapports plus ou moins directs avec lui (le roi), par l’intermédiaire de son entourage, que ma conduite était approuvée ? Ou que tout au moins, elle n’était pas blamée ? » (40). Et pour être encore plus clair, il ajoute : « Si des ‘collaborationnistes’ sincères se trompaient, Léopold III aurait dû les avertir, ou les faire avertir, même au risque de déplaire aux Allemands » (41).

Engagé mais avec raison

Il faut dire que conformément aux conseils de Capelle, Pierre Daye s’engage assez nettement dans la « politique de présence » en rejoignant, à l’automne 1940, la rédaction du Nouveau Journal que lance Paul Colin, son ancien condisciple de l’Institut Saint-Louis. Déjà patron de l’hebdomadaire Cassandre, ce dernier est, selon Jean-Léo, un véritable « Frégoli polygraphe, merveilleusement à l’aise une plume à la main » (42). Rescapé du camp du Vernet, il a réuni autour de lui une équipe brillante où figurent entre autres Robert Poulet, le rédacteur en chef, Nicolas Barthélémy, Guido Eeckels, Paul Herten, Joseph Jumeau (alias Pierre Hubermont) et Paul Werrie (43). Son quotidien revendique « un esprit nouveau » et veut « montrer aux Belges que leur pays doit réclamer et prendre sa place dans l’économie continentale à l’érection de laquelle le Reich allemand – c’est un fait – consacre aujourd’hui une grande partie de son effort » (44). Partisan d’une collaboration digne et relativement modérée, il s’agit néanmoins, aux yeux des résistants et des Belges de Londres, d’un journal « emboché ».

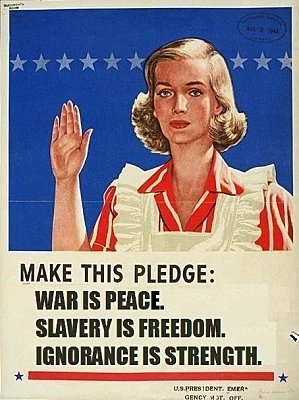

Chargé de la rubrique de politique étrangère, Pierre Daye en sera l’un des principaux chroniqueurs jusqu’en avril 1943. Le Nouveau Journal n’est pas le seul organe de presse à accueillir sa prose puisque l’on trouve également sa signature dans Junges Europa, Das Neue Europa, Europäische Revue, Signal, Actu, le Petit Parisien, Je suis partout, et qu’il s’exprime de temps à autres au micro de Radio-Bruxelles. Quoique très dense, cette activité journalistique ne l’empêche pas de publier aussi quelques nouveaux livres. En 1941, il fait ainsi paraître un essai politique, Guerre et révolution, lettre d’un Belge à un ami français, suivi d’un Rubens, puis de Par le monde qui change, un ouvrage où il évoque quelques-uns des pays qu’il a visités, décerne au passage quelques compliments au Reich pour avoir encouragé la jeunesse et amélioré la race, et décrit Adolf Hitler comme « un homme simple, très différend des hobereaux allemands d’autrefois » (45). Si l’homme de lettres ne fait pas mystère de ses sympathies, il s’abstient toutefois de franchir certaines limites : il garde notamment ses distances avec la Légion Wallonie et fait même publiquement savoir qu’il n’est jamais intervenu en sa faveur auprès du palais royal. Il admire, dit-il, le courage des volontaires mais ne comprend pas vraiment leur démarche. Très attaché à l’unité et à l’intégrité de la Belgique comme à la personne du roi, il prend grand soin de ne jamais cautionner une autre ligne que celle-là. Hostile à la persécution des Juifs comme à tout démembrement du royaume, Pierre Daye considère globalement les affaires politiques d’un œil sévère : « Trop de gens aux dents longues, trop de bonshommes intéressés. Trop de tripotages. Trop de fortunes aussi gigantesques que rapides » (46). Désireux de voir la Belgique se réorganiser sur un schéma centralisateur, monarchique et corporatif, il regroupe autour de lui un « Bureau politique », auquel prennent part ses amis Gustave Wyns et Jacques Crokaert, puis s’associe, en mai 1941, à la tentative de créer un Parti des Provinces Romanes. Ce dernier doit soutenir l’Ordre Nouveau européen, protéger la race et favoriser la fondation d’un État autoritaire, corporatif et chrétien (47). Le projet fera long feu car le 5 août 1941, les autorités allemandes y opposent leur veto. Autre geste politique de Pierre Daye : le 1er février 1943, il adhère à la Société Européenne des Écrivains (48) et plus précisément à l’une de ses deux sections belges, la Communauté Culturelle Wallonne (49). Cet engagement sans détour ne fait cependant pas de lui un fanatique ou un ultra, et c’est assez souvent, il faut le dire, qu’il intervient en faveur de certains Israélites ou de résistants (dont le communiste Albert Marteaux et le socialiste Victor Larock).

Chargé de la rubrique de politique étrangère, Pierre Daye en sera l’un des principaux chroniqueurs jusqu’en avril 1943. Le Nouveau Journal n’est pas le seul organe de presse à accueillir sa prose puisque l’on trouve également sa signature dans Junges Europa, Das Neue Europa, Europäische Revue, Signal, Actu, le Petit Parisien, Je suis partout, et qu’il s’exprime de temps à autres au micro de Radio-Bruxelles. Quoique très dense, cette activité journalistique ne l’empêche pas de publier aussi quelques nouveaux livres. En 1941, il fait ainsi paraître un essai politique, Guerre et révolution, lettre d’un Belge à un ami français, suivi d’un Rubens, puis de Par le monde qui change, un ouvrage où il évoque quelques-uns des pays qu’il a visités, décerne au passage quelques compliments au Reich pour avoir encouragé la jeunesse et amélioré la race, et décrit Adolf Hitler comme « un homme simple, très différend des hobereaux allemands d’autrefois » (45). Si l’homme de lettres ne fait pas mystère de ses sympathies, il s’abstient toutefois de franchir certaines limites : il garde notamment ses distances avec la Légion Wallonie et fait même publiquement savoir qu’il n’est jamais intervenu en sa faveur auprès du palais royal. Il admire, dit-il, le courage des volontaires mais ne comprend pas vraiment leur démarche. Très attaché à l’unité et à l’intégrité de la Belgique comme à la personne du roi, il prend grand soin de ne jamais cautionner une autre ligne que celle-là. Hostile à la persécution des Juifs comme à tout démembrement du royaume, Pierre Daye considère globalement les affaires politiques d’un œil sévère : « Trop de gens aux dents longues, trop de bonshommes intéressés. Trop de tripotages. Trop de fortunes aussi gigantesques que rapides » (46). Désireux de voir la Belgique se réorganiser sur un schéma centralisateur, monarchique et corporatif, il regroupe autour de lui un « Bureau politique », auquel prennent part ses amis Gustave Wyns et Jacques Crokaert, puis s’associe, en mai 1941, à la tentative de créer un Parti des Provinces Romanes. Ce dernier doit soutenir l’Ordre Nouveau européen, protéger la race et favoriser la fondation d’un État autoritaire, corporatif et chrétien (47). Le projet fera long feu car le 5 août 1941, les autorités allemandes y opposent leur veto. Autre geste politique de Pierre Daye : le 1er février 1943, il adhère à la Société Européenne des Écrivains (48) et plus précisément à l’une de ses deux sections belges, la Communauté Culturelle Wallonne (49). Cet engagement sans détour ne fait cependant pas de lui un fanatique ou un ultra, et c’est assez souvent, il faut le dire, qu’il intervient en faveur de certains Israélites ou de résistants (dont le communiste Albert Marteaux et le socialiste Victor Larock).

La guerre n’a pas émoussé le goût pour les voyages de Pierre Daye qui continue, dans la mesure où les événements le permettent, à se déplacer en Europe. Début 1942, il est par exemple au Portugal, puis en août en Hongrie, et séjourne, en fin d’année, à Rome. Dans la ville éternelle, il renoue avec de vieux amis, comme la duchesse de Villarosa ou le sénateur Aldobrandini Rangoni, tous très anglophiles, et s’entretient, le 10 janvier 1943, avec le prince Umberto. Quatre jours auparavant, il a pu être reçu par le Souverain Pontife, ce qui revêt pour lui une importance toute particulière. Grâce à un proche du Pape, le père jésuite Tacchi-Venturi, il a en effet obtenu de voir brièvement Sa Sainteté Pie XII qui l’a interrogé sur la situation belge et lui a donné sa bénédiction. « Ce qui m’avait le plus ému durant cette entrevue », rapporte-t-il, « c’est la grande allure du Saint-Père, son air de seigneur, la beauté de son visage ascétique et blême, avec ses yeux d’un noir brillant, sa longue bouche volontaire, son nez en bec d’aigle, la noblesse de ses gestes » (50). Peu de temps après cette promenade italienne, en février-mars 1943, Pierre Daye se rend à Madrid. N’étant inféodé à aucune faction politique, il profite de ce passage dans un pays non-belligérant pour adresser, de son propre chef, un courrier à Paul van Zeeland : « Il faut souhaiter », lui écrit-il, « que des éléments provenant des deux clans entre lesquels se divise aujourd’hui la Belgique, celui des “gens de Londres“ et celui de ceux que vous appelez, je crois, les “collaborationnistes“ (je suis pour ma part convaincu que tous deux comptent des patriotes sincères) puissent bientôt, à l’issue des hostilités, se comprendre et collaborer, autour du Roi, dans l’intérêt même de notre pays » (51). Par le biais de l’armateur Pierre Grisar, il envoie une missive du même genre à Hubert Pierlot, le chef du gouvernement belge en exil. Faut-il préciser qu’il n’obtiendra aucune réponse…

La guerre n’a pas émoussé le goût pour les voyages de Pierre Daye qui continue, dans la mesure où les événements le permettent, à se déplacer en Europe. Début 1942, il est par exemple au Portugal, puis en août en Hongrie, et séjourne, en fin d’année, à Rome. Dans la ville éternelle, il renoue avec de vieux amis, comme la duchesse de Villarosa ou le sénateur Aldobrandini Rangoni, tous très anglophiles, et s’entretient, le 10 janvier 1943, avec le prince Umberto. Quatre jours auparavant, il a pu être reçu par le Souverain Pontife, ce qui revêt pour lui une importance toute particulière. Grâce à un proche du Pape, le père jésuite Tacchi-Venturi, il a en effet obtenu de voir brièvement Sa Sainteté Pie XII qui l’a interrogé sur la situation belge et lui a donné sa bénédiction. « Ce qui m’avait le plus ému durant cette entrevue », rapporte-t-il, « c’est la grande allure du Saint-Père, son air de seigneur, la beauté de son visage ascétique et blême, avec ses yeux d’un noir brillant, sa longue bouche volontaire, son nez en bec d’aigle, la noblesse de ses gestes » (50). Peu de temps après cette promenade italienne, en février-mars 1943, Pierre Daye se rend à Madrid. N’étant inféodé à aucune faction politique, il profite de ce passage dans un pays non-belligérant pour adresser, de son propre chef, un courrier à Paul van Zeeland : « Il faut souhaiter », lui écrit-il, « que des éléments provenant des deux clans entre lesquels se divise aujourd’hui la Belgique, celui des “gens de Londres“ et celui de ceux que vous appelez, je crois, les “collaborationnistes“ (je suis pour ma part convaincu que tous deux comptent des patriotes sincères) puissent bientôt, à l’issue des hostilités, se comprendre et collaborer, autour du Roi, dans l’intérêt même de notre pays » (51). Par le biais de l’armateur Pierre Grisar, il envoie une missive du même genre à Hubert Pierlot, le chef du gouvernement belge en exil. Faut-il préciser qu’il n’obtiendra aucune réponse…

Face à l’orage

La destination préférée de Pierre Daye reste la France où le Belge a ses habitudes depuis des lustres et où il compte de nombreux amis. À Paris, il rencontre bien sûr les gens de Je suis partout : Lucien Rebatet (« bouillant, grinçant, belliqueux, rageur »), Brasillach, Lesca (« serein, définitif et magnifique »), Georges Blond, Pierre-Antoine Cousteau, Claude Jeantet et Alain Laubreaux (« féroce, débordant d’esprit, d’érudition théâtrale »). À La Gerbe, il rend visite à Alphonse de Chateaubriant qu’il invitera bientôt à Bruxelles. Toujours friand de distractions, il retrouve aussi son complice Carl Doutreligne et dîne parfois avec lui chez Maxim’s où les deux compères coudoient Cécile Sorel et Maurice Chevalier, mais aussi Fernand de Brinon, Alice Cocéa, Serge Lifar et l’ambassadeur Scapini. Sans parler de quelques Belges comme les barons Jean Empain et de Becker-Remy… Doué pour les croquis, Pierre Daye en parsème les articles qu’il donne alors au Nouveau Journal et au Petit Parisien. On y voit défiler Fernand de Brinon, « la taille moyenne, le profil aquilin, la voix un peu haute », Pierre Laval, « l’œil plein d’ironie » et presque « asiatique », Jean Chiappe, avec « ses souliers vernis à tiges de drap mastic et ses hauts talons, son melon un peu penché sur l’oreille, sa canne à bague d’or », ou encore Robert Brasillach, « le regard toujours ingénu derrière ses grosses lunettes à monture d’écaille ». De cette galerie, le chroniqueur n’omet pas le maréchal, « figure ferme, au teint mat et sain », ni Jacques Doriot, « grand, de visage plus martelé que sur les photos, agile, quoique puissant (…), l’œil très noir derrière les verres ronds, le geste sobre » (52).

Présent dans les gazettes, Pierre Daye l’est tout autant aux devantures des librairies : en 1942, il fait paraître deux essais politiques (L ‘Europe aux Européens et Trente-deux mois chez les députés), puis en 1943, un texte sur l’Afrique (Problèmes congolais), et en 1944, un recueil de contes (D’ombre et de lumière). À compter de 1943, son engagement se concrétise aussi par son accession à un poste officiel dans l’administration belge. Sur recommandation du Flamand Gérard Romsée, il est en effet nommé, le 25 juin 1943, au poste un peu inattendu de … commissaire général à l’Éducation Physique et aux Sports. En soi, il s’agit d’une fonction peu compromettante et qui fournit à son titulaire d’excellentes justifications pour voyager. Reste qu’elle fait de Pierre Daye un fonctionnaire officiel de la collaboration, ce qui peut se révéler extrêmement dangereux. De fait, loin d’aller vers l’apaisement qu’il souhaitait, la situation se dégrade et les rivalités belges se muent désormais en sanglants règlements de compte. « Les hitlériens de nationalité belge [sont] plus abjects encore que leurs maîtres allemands », proclame un journal clandestin communiste. « Cette vermine immonde doit être écrasée (…) Les Partisans belges se sont juré de liquider ces bêtes puantes » (53) L’année 1942 est ponctuée d’au moins 67 attentats et l’année 1943 connaît une recrudescence vertigineuse des actes violents, au point que le chef de l’administration allemande, Eggert Reeder, parle carrément d’une vague de meurtres ou Mordwelle. « Dans la rue et les campagnes, surtout à partir de 1943 », écrit une historienne belge, « règne une atmosphère de guerre civile : rexistes et nationalistes flamands, ainsi que les membres de leurs familles, sont abattus, sans autre forme de procès, sans distinction d’âge ou de sexe » (54).

Présent dans les gazettes, Pierre Daye l’est tout autant aux devantures des librairies : en 1942, il fait paraître deux essais politiques (L ‘Europe aux Européens et Trente-deux mois chez les députés), puis en 1943, un texte sur l’Afrique (Problèmes congolais), et en 1944, un recueil de contes (D’ombre et de lumière). À compter de 1943, son engagement se concrétise aussi par son accession à un poste officiel dans l’administration belge. Sur recommandation du Flamand Gérard Romsée, il est en effet nommé, le 25 juin 1943, au poste un peu inattendu de … commissaire général à l’Éducation Physique et aux Sports. En soi, il s’agit d’une fonction peu compromettante et qui fournit à son titulaire d’excellentes justifications pour voyager. Reste qu’elle fait de Pierre Daye un fonctionnaire officiel de la collaboration, ce qui peut se révéler extrêmement dangereux. De fait, loin d’aller vers l’apaisement qu’il souhaitait, la situation se dégrade et les rivalités belges se muent désormais en sanglants règlements de compte. « Les hitlériens de nationalité belge [sont] plus abjects encore que leurs maîtres allemands », proclame un journal clandestin communiste. « Cette vermine immonde doit être écrasée (…) Les Partisans belges se sont juré de liquider ces bêtes puantes » (53) L’année 1942 est ponctuée d’au moins 67 attentats et l’année 1943 connaît une recrudescence vertigineuse des actes violents, au point que le chef de l’administration allemande, Eggert Reeder, parle carrément d’une vague de meurtres ou Mordwelle. « Dans la rue et les campagnes, surtout à partir de 1943 », écrit une historienne belge, « règne une atmosphère de guerre civile : rexistes et nationalistes flamands, ainsi que les membres de leurs familles, sont abattus, sans autre forme de procès, sans distinction d’âge ou de sexe » (54).

Le 14 avril 1943, Paul Colin, le patron et l’ami de Pierre Daye, est abattu dans sa librairie. L’un de ses employés, Gaston Bekeman, tombe sous les balles du même assassin. Le meurtrier, Arnaud Fraiteur, un étudiant de 22 ans (55), et ses deux complices, André Bertulot et Maurice Raskin, seront condamnés à mort et pendus. « Paul Colin », écrit Pierre Daye, « n’était pas seulement le premier critique d’art de Belgique (…) l’auteur de tant d’essais littéraires, artistiques, politiques, l’historien profond des ducs de Bourgogne, l’éditeur, le directeur du Nouveau Journal et de Cassandre, le chroniqueur et le pamphlétaire, le fondateur et le président de l’Association des journalistes belges, mais un amateur éclairé, un homme de goût et surtout un être terriblement intelligent, un des plus intelligents que j’ai rencontrés dans cette partie agitée de ma carrière » (56) « Il était détesté, naturellement », ajoute-t-il, « car il haïssait la médiocrité et ne se privait pas de le montrer, avec une verve, un éclat terribles. Il avait la dent dure et adorait se faire des ennemis » (57).

Profondément choqué par le déferlement de violence auquel il assiste, Pierre Daye en juge sévèrement les inspirateurs : « Il fallait », constate-t-il amèrement, « par la provocation, empoisonner une atmosphère trop paisible, donc trop favorable à l’occupant. Il fallait susciter des vengeances, allumer l’esprit de représailles » (58). Et confronté à cet engrenage fatal (59), il en décrit tristement le mécanisme : « De braves gens, mûs uniquement par le sentiment patriotique, ne se doutaient point du vrai rôle qu’on leur faisait ainsi jouer. Et des canailles trouvaient, en se glissant parmi eux, le moyen de commettre les plus bas crimes (…) Se sentant sans protection, d’autres braves gens, de l’autre idéologie, se dirent alors qu’il fallait se défendre soi-même ; non pas se venger, mais si l’on voulait vivre, répondre à la terreur par la terreur » (60).

Profondément choqué par le déferlement de violence auquel il assiste, Pierre Daye en juge sévèrement les inspirateurs : « Il fallait », constate-t-il amèrement, « par la provocation, empoisonner une atmosphère trop paisible, donc trop favorable à l’occupant. Il fallait susciter des vengeances, allumer l’esprit de représailles » (58). Et confronté à cet engrenage fatal (59), il en décrit tristement le mécanisme : « De braves gens, mûs uniquement par le sentiment patriotique, ne se doutaient point du vrai rôle qu’on leur faisait ainsi jouer. Et des canailles trouvaient, en se glissant parmi eux, le moyen de commettre les plus bas crimes (…) Se sentant sans protection, d’autres braves gens, de l’autre idéologie, se dirent alors qu’il fallait se défendre soi-même ; non pas se venger, mais si l’on voulait vivre, répondre à la terreur par la terreur » (60).

Sa charge administrative facilitant les déplacements, Pierre Daye ne se prive pas de revenir en France autant qu’il le souhaite. Le 29 novembre 1943, il est à Vichy où il déjeune avec Pierre Laval, « la mèche napoléonienne sur la lippe fatiguée (…) Ironique, sans illusion, finaud » (61). Le soir, il dîne au Chantecler avec Stanislas de la Rochefoucauld, l’ambassadeur Gaston Bergery (« toujours l’air d’un jeune père jésuite, sec, précis et désabusé, strictement vêtu de drap sombre ») et son épouse, Bettina Jones, ancienne égérie de Schiaparelli. Au retour, le Belge s’arrête bien sûr à Paris où il rend visite à Drieu, avenue de Breteuil. « Il m’effraye », note-t-il, « par sa lucidité triste : la guerre, la décadence des possédants, la lourdeur des Allemands, l’incompréhension des femmes, le préoccupent. Son scepticisme me désespère et me séduit à la fois » (62). De retour chez lui, avenue de Tervueren, à Etterbeek, Pierre Daye n’est pas rasséréné par l’atmosphère ambiante. Les attentats se multiplient et les positions des uns et des autres se crispent jusqu’à l’absurde. Même les nuits ne laissent désormais plus aucun répit : « Qui n’a pas connu », raconte-t-il, « l’angoisse causée par des centaines d’avions passant sur les têtes, tandis que roulait à travers les nuages un bruit sourd, dominant tous les autres, et la sensation de la mort qui pouvait vous atteindre à chaque seconde, alors que l’on se sentait accablé d’impuissance, hors de toute possibilité de fuite ou de recours quelconque, ne sait pas ce que furent pour les nerfs ces heures démoralisantes » (63).

Loin des épurateurs

Dans ces conditions, et compte tenu de l’avenir immédiat de la Belgique tel qu’il l’anticipe, Daye songe de plus en plus à mettre quelque distance entre les futurs libérateurs du royaume et lui-même. En mai 1944, l’occasion s’offre à lui d’effectuer une tournée officielle en Espagne en qualité de commissaire aux sports, déplacement qui possède l’immense avantage de le mettre à l’abri des pistoleros du Front de l’Indépendance, comme des bombes de la RAF et de l’US Air Force. Le 19 mai, le quotidien madrilène ABC rapporte que le Belge a donné une conférence de presse dans la capitale ibérique, et quant à l’intéressé lui-même, il signale qu’il passe ensuite quelques jours à Barcelone afin de s’entretenir avec le général Moscardo (1878-1956), délégué national aux sports. Peu pressé de rentrer en Belgique, Pierre Daye se trouve encore à Madrid le 6 juin lorsque tombe la nouvelle du débarquement allié en Normandie. Ses supérieurs le pressent de rentrer au pays, mais l’écrivain n’en a cure : « J’étais venu librement comme les autres fois », commente-t-il. « Nul ne m’avait donné d’ordres, et je ne me sentais pas d’humeur à commencer à en recevoir » (64). D’ailleurs, un retour impliquerait de traverser une France en pleine insurrection et comme il le souligne : « Je possédais les meilleures raisons du monde pour ne pas tomber entre les mains d’excités pris de folie sanguinaire » (65). À cette époque commence donc pour Pierre Daye une seconde existence, celle d’un émigré politique. Elle va durer un peu plus de quinze ans.

Les premiers temps d’exil ne sont pas trop durs car l’expatrié possède encore quelques relations : il est reçu chez le phalangiste Eugenio d’Ors (66) ou chez le général Eugenio Espinosa de los Monteros, ancien ambassadeur à Berlin, et dîne même parfois avec Walter Starkie (67), le directeur de l’Institut Britannique de Madrid. Plus tard, il verra de temps en temps François Piétri et l’académicien Abel Bonnard. Quelles que soient les difficultés qu’il rencontre et la peine qu’il éprouve, cet exil lui épargne à tout le moins un sort funeste. L’épuration belge se veut en effet particulièrement vindicative puisque, si l’on en croit Paul Sérant, un certain Marcel Houtman exige par exemple que soient exécutés tous les Belges ayant combattu sur le front de l’Est, tous les écrivains et journalistes de la collaboration et tous les fonctionnaires ayant servi les desseins de l’occupant ! (68) Les intellectuels ne peuvent donc guère espérer de mansuétude. Le poète René Baert a été sommairement abattu au coin d’un bois, quelque part en Allemagne, plusieurs journalistes sont condamnés à la peine capitale et fusillés (Paul Herten, José Sreel, Jules Lhoste, Victor Meulenyser, Charles Nisolles, Paul Lespagnard), d’autres échappent de très peu au poteau (Robert Poulet, Paul Jamin), et quelques-uns, comme Pierre Hubermont et Gabriel Figeys, écopent de lourdes peines de détention. Le peintre Marc Eemans est frappé d’une peine de huit ans de prison, tandis que le dramaturge Michel de Ghelderode se fait copieusement insulter et chasser de son emploi. Beaucoup ne retrouveront un peu de tranquillité qu’à l’étranger : Simenon, Hergé et Henri de Man en Suisse, Paul Werrie en Espagne puis en France, Raymond de Becker (condamné à mort puis à la détention perpétuelle), Claude Elsen (condamné à mort par contumace) et Louis Carette (condamné par contumace à 15 ans de travaux forcés) en France. Certains feront malgré tout, hors de Belgique, de brillantes carrières : émigré à Paris, Oscar Van Godtsenhoven, alias Jan Van Dorp, y remportera un prix (1948) pour son Flamand des vagues ; Louis Carette, alias Félicien Marceau, sera élu à l’Académie française (1975), tandis que Jean Libert et Gaston Vandenpanhuyse vendront des milliers de livres sous les noms d’emprunt de Paul Kenny et Jean-Gaston Vandel. « La répression contre les intellectuels », note Elsa Van Brusseghem-Loorne, « surtout en Wallonie (69), prendra (…) une tournure dramatique et particulièrement cruelle, comme si le pouvoir, détenu par des classes en déclin, voulait éliminer par tous les moyens ceux qui, par leurs efforts, étaient la preuve vivante de son infériorité culturelle » (70)…

Les premiers temps d’exil ne sont pas trop durs car l’expatrié possède encore quelques relations : il est reçu chez le phalangiste Eugenio d’Ors (66) ou chez le général Eugenio Espinosa de los Monteros, ancien ambassadeur à Berlin, et dîne même parfois avec Walter Starkie (67), le directeur de l’Institut Britannique de Madrid. Plus tard, il verra de temps en temps François Piétri et l’académicien Abel Bonnard. Quelles que soient les difficultés qu’il rencontre et la peine qu’il éprouve, cet exil lui épargne à tout le moins un sort funeste. L’épuration belge se veut en effet particulièrement vindicative puisque, si l’on en croit Paul Sérant, un certain Marcel Houtman exige par exemple que soient exécutés tous les Belges ayant combattu sur le front de l’Est, tous les écrivains et journalistes de la collaboration et tous les fonctionnaires ayant servi les desseins de l’occupant ! (68) Les intellectuels ne peuvent donc guère espérer de mansuétude. Le poète René Baert a été sommairement abattu au coin d’un bois, quelque part en Allemagne, plusieurs journalistes sont condamnés à la peine capitale et fusillés (Paul Herten, José Sreel, Jules Lhoste, Victor Meulenyser, Charles Nisolles, Paul Lespagnard), d’autres échappent de très peu au poteau (Robert Poulet, Paul Jamin), et quelques-uns, comme Pierre Hubermont et Gabriel Figeys, écopent de lourdes peines de détention. Le peintre Marc Eemans est frappé d’une peine de huit ans de prison, tandis que le dramaturge Michel de Ghelderode se fait copieusement insulter et chasser de son emploi. Beaucoup ne retrouveront un peu de tranquillité qu’à l’étranger : Simenon, Hergé et Henri de Man en Suisse, Paul Werrie en Espagne puis en France, Raymond de Becker (condamné à mort puis à la détention perpétuelle), Claude Elsen (condamné à mort par contumace) et Louis Carette (condamné par contumace à 15 ans de travaux forcés) en France. Certains feront malgré tout, hors de Belgique, de brillantes carrières : émigré à Paris, Oscar Van Godtsenhoven, alias Jan Van Dorp, y remportera un prix (1948) pour son Flamand des vagues ; Louis Carette, alias Félicien Marceau, sera élu à l’Académie française (1975), tandis que Jean Libert et Gaston Vandenpanhuyse vendront des milliers de livres sous les noms d’emprunt de Paul Kenny et Jean-Gaston Vandel. « La répression contre les intellectuels », note Elsa Van Brusseghem-Loorne, « surtout en Wallonie (69), prendra (…) une tournure dramatique et particulièrement cruelle, comme si le pouvoir, détenu par des classes en déclin, voulait éliminer par tous les moyens ceux qui, par leurs efforts, étaient la preuve vivante de son infériorité culturelle » (70)…

Au pays de Martin Fierro

Faute d’avoir pu épingler Pierre Daye à leur tableau de chasse, les nouvelles autorités belges se penchent néanmoins sur son cas, et la 4e Chambre du Conseil de Guerre n’éprouve aucun scrupule à le condamner par contumace, le 18 décembre 1946, à la peine de mort. Des pressions sont exercées sur l’Espagne qui ne peut décemment, sous le nez des Alliés, offrir l’hospitalité à tous les proscrits d’Europe et se voit donc contrainte d’effectuer des choix. Si le Caudillo a accordé l’asile politique à Léon Degrelle, Jean Bichelone ou Abel Bonnard, il n’a pas gardé Pierre Laval qui a fini devant un peloton d’exécution… Malgré le soutien de quelques dignitaires franquistes, comme José Félix de Lequerica, Manuel Aznar et José María de Areilza, Pierre Daye fait lui aussi partie des gens que l’on incite vivement à quitter l’Espagne. Muni d’un passeport espagnol libellé au nom de Pedro Adán, l’ancien commissaire aux sports s’envole donc pour Buenos Aires où il arrive le 21 mai 1947. En Argentine, le nouveau venu n’est pas livré à lui-même car plusieurs amis et connaissances l’ont précédé et sont là pour l’accueillir. Au nombre de ces fidèles, citons Charles Lesca (71), alias Carlos Levray ou Pedro Vignau, ancien directeur de Je suis partout, Georges Guilbaud (72), alias Jorge Degay, et Robert Pincemin (73), alias Rives ; dans le comité d’accueil figure également Mario Octavio Amadeo (74), l’un des proches conseillers du Président Perón. À peu près à la même époque, Buenos Aires voit aussi arriver Jean-Jules Lecomte, alias Jean Degraaf Verhegen, ancien bourgmestre rexiste de Chimay ; plus tard, en 1949, débarquera encore Henri Collard-Bovy, un avocat bruxellois d’un certain renom. Avisée de l’arrivée de Pierre Daye, Bruxelles se manifeste aussitôt auprès du gouvernement argentin et réclame son extradition (17 juin 1947). Cette demande ayant été rejetée, l’écrivain est alors tout simplement déchu de sa nationalité. À compter du 24 décembre 1947, l’ancien combattant de 1914-18, vétéran de Tabora et ex-député, n’est donc plus citoyen belge, il est apatride.

Âgé de 55 ans et plutôt combatif, l’homme est cependant loin d’avoir dit son dernier mot. Le 29 juin 1948, il prend part, avec quelques autres expatriés (75), à la création de la Société Argentine pour l’Accueil des Européens ou Sociedad Argentina para la Recepción de Europeos (SARE). Jouissant de la discrète protection de l’anthropologue Santiago Peralta, patron des services d’immigration, et bénéficiant des encouragements du cardinal Santiago Luis Copello (1880-1967), cette société s’efforce d’aider les « maudits » qui continuent d’affluer sur les rives du Rio de la Plata. Pierre Daye reprend aussi son métier de journaliste et participe au lancement de plusieurs publications dont Hebdo (1947), Europe-Argentine (1948), Argentina 49, Paroles françaises et Nouvelles d’Argentine. Naturalisé argentin en 1949, il collabore également aux revues Criterio et Itinerarium, à El Economista, le journal que fonde l’ancien Premier ministre yougoslave Milan Stojadinović (1888-1961), ainsi qu’à Dinámica Social, le mensuel que lance, en 1952, l’ancien hiérarque fasciste Carló Scorza (alias Camillo Sirtori)-(76). Organe officiel du Centre d’Études Économiques et Sociales, cette revue regroupe de nombreuses plumes de talent dont celles du philosophe roumain Georges Uscatescu, d’Ante Pavelić (alias A. S. Mrzlodolski), du père Juan Ramon Sepich, de Julio Irazusta, ou encore de Jean Pleyber, André Thérive, Jacques de Mahieu et Jacques Ploncard (alias Jacques de Sainte-Marie). Pierre Daye ne délaisse pas non plus le terrain politique où il parvient, avec son entregent habituel, à rester en bons termes à la fois avec les traditionalistes catholiques et les péronistes. Durant l’été 1949, il a quelques contacts avec le Centre des Forces Nationalistes, mais s’intéresse aussi à la Troisième Position de Juan Perón. Avec Radu Ghenea, Georges Guilbaud, René Lagrou (77) et Victor de la Serna, il signe d’ailleurs à ce sujet une note qui sera remise au chef de l’État. En septembre 1950, l’écrivain a le plaisir de renouer avec le ministre belge Marcel Henri Jaspar (1901-1982) qui est de passage dans le cône sud. Autre contact important, Sir Oswald Mosley, qu’il rencontre en novembre 1950, lors de la visite que l’ancien chef de la British Union of Fascists fait en Argentine (78). Venu s’entretenir avec Hans Ulrich Rudel, l’Anglais sera reçu par Juan Perón. Installé à Buenos Aires, dans le quartier de Palermo, et nommé professeur à l’Université de La Plata (sur recommandation de son ami le ministre des Affaires Étrangères Hipólito Jesús Paz), Pierre Daye entretient d’autre part une abondante correspondance.

Âgé de 55 ans et plutôt combatif, l’homme est cependant loin d’avoir dit son dernier mot. Le 29 juin 1948, il prend part, avec quelques autres expatriés (75), à la création de la Société Argentine pour l’Accueil des Européens ou Sociedad Argentina para la Recepción de Europeos (SARE). Jouissant de la discrète protection de l’anthropologue Santiago Peralta, patron des services d’immigration, et bénéficiant des encouragements du cardinal Santiago Luis Copello (1880-1967), cette société s’efforce d’aider les « maudits » qui continuent d’affluer sur les rives du Rio de la Plata. Pierre Daye reprend aussi son métier de journaliste et participe au lancement de plusieurs publications dont Hebdo (1947), Europe-Argentine (1948), Argentina 49, Paroles françaises et Nouvelles d’Argentine. Naturalisé argentin en 1949, il collabore également aux revues Criterio et Itinerarium, à El Economista, le journal que fonde l’ancien Premier ministre yougoslave Milan Stojadinović (1888-1961), ainsi qu’à Dinámica Social, le mensuel que lance, en 1952, l’ancien hiérarque fasciste Carló Scorza (alias Camillo Sirtori)-(76). Organe officiel du Centre d’Études Économiques et Sociales, cette revue regroupe de nombreuses plumes de talent dont celles du philosophe roumain Georges Uscatescu, d’Ante Pavelić (alias A. S. Mrzlodolski), du père Juan Ramon Sepich, de Julio Irazusta, ou encore de Jean Pleyber, André Thérive, Jacques de Mahieu et Jacques Ploncard (alias Jacques de Sainte-Marie). Pierre Daye ne délaisse pas non plus le terrain politique où il parvient, avec son entregent habituel, à rester en bons termes à la fois avec les traditionalistes catholiques et les péronistes. Durant l’été 1949, il a quelques contacts avec le Centre des Forces Nationalistes, mais s’intéresse aussi à la Troisième Position de Juan Perón. Avec Radu Ghenea, Georges Guilbaud, René Lagrou (77) et Victor de la Serna, il signe d’ailleurs à ce sujet une note qui sera remise au chef de l’État. En septembre 1950, l’écrivain a le plaisir de renouer avec le ministre belge Marcel Henri Jaspar (1901-1982) qui est de passage dans le cône sud. Autre contact important, Sir Oswald Mosley, qu’il rencontre en novembre 1950, lors de la visite que l’ancien chef de la British Union of Fascists fait en Argentine (78). Venu s’entretenir avec Hans Ulrich Rudel, l’Anglais sera reçu par Juan Perón. Installé à Buenos Aires, dans le quartier de Palermo, et nommé professeur à l’Université de La Plata (sur recommandation de son ami le ministre des Affaires Étrangères Hipólito Jesús Paz), Pierre Daye entretient d’autre part une abondante correspondance.

On sait notamment qu’il a de fréquents échanges épistolaires avec des gens comme Jean Azéma, Maurice Bardèche, Henri de Man, Georges Remi (Hergé), Christian du Jonchay (alias Della Torre), le père Omer Englebert, Simon Arbellot, Henri Poulain ou l’éditeur genevois Constant Bourquin. Au plan des relations sociales, il est probable qu’il rencontre assez souvent quelques collègues d’autrefois comme Henri Lèbre (alias Enrique Winter), un ancien du Cri du Peuple, Henri Janières, vétéran de Paris-Soir (et futur correspondant local du Monde) et Pierre Villette-Dorsay, ancien chroniqueur parlementaire à Je suis partout et rescapé de Radio-Patrie (79), qui tous résident dans la capitale fédérale. Il possède également d’excellents amis argentins, comme Juan Carlos Goyeneche (1913-1982), l’attaché de presse de la présidence de la République. En août 1951, il assiste sans doute, à la cathédrale de Buenos Aires, à la messe qui est célébrée, devant des milliers de fidèles, pour le repos de l’âme du maréchal Pétain, et fin 1952 à celle qui est dite pour Charles Maurras. Séparé de son lectorat habituel et résidant dans un pays hispanophone, Pierre Daye ne publie quasiment plus de livres : seul paraîtra, en 1952, un essai politique, El suicidio de la burguesía (Le suicide de la bourgeoisie). Cela ne l’empêche bien évidemment pas d’écrire et il laissera à la postérité de nombreux inédits. Parmi ceux-ci et outre divers essais (Le voyageur de la guerre, 1940-1945 ; Panorama espagnol ; En Argentine ; Pris aux autres), son long exil lui permet de rédiger d’imposants mémoires. Intitulés D’un monde à l’autre et ne comptant pas moins de 63 chapitres ou 1600 pages dactylographiées, ces mémoires sont, hélas, encore inédits et dorment toujours dans les bibliothèques bruxelloises…

La chute de Juan Perón, en septembre 1955, n’entraîne pas d’inconvénients majeurs pour Pierre Daye qui n’est pas vraiment un acteur de la vie politique locale. Tenu pour proche du péronisme, il se retrouve néanmoins marginalisé et éloigné des nouveaux cercles dirigeants. Plus que le changement de régime, c’est plutôt l’isolement et l’oubli qui le menacent désormais. Le temps fait lentement son œuvre et la plupart des Belges l’ont d’ores et déjà oublié. Pas mal d’émigrés ont regagné l’Europe, on lui demande de moins en moins d’articles et la solitude le guette. C’est dans ce contexte un peu maussade que le 20 février 1960, à un peu moins de 68 ans, une hémorragie cérébrale vient brutalement mettre un terme à son existence. Cultivé, discret et fort modéré, on se demande encore ce que cet homme avait bien pu faire pour que la Belgique d’après-guerre lui témoigne d’une vindicte aussi tenace. Se pourrait-il tout simplement que l’on ait jugé, en haut lieu, qu’il en savait beaucoup trop long sur les arcanes (et les drôles de combines) de l’Occupation et qu’il fallait le discréditer à jamais ?

La chute de Juan Perón, en septembre 1955, n’entraîne pas d’inconvénients majeurs pour Pierre Daye qui n’est pas vraiment un acteur de la vie politique locale. Tenu pour proche du péronisme, il se retrouve néanmoins marginalisé et éloigné des nouveaux cercles dirigeants. Plus que le changement de régime, c’est plutôt l’isolement et l’oubli qui le menacent désormais. Le temps fait lentement son œuvre et la plupart des Belges l’ont d’ores et déjà oublié. Pas mal d’émigrés ont regagné l’Europe, on lui demande de moins en moins d’articles et la solitude le guette. C’est dans ce contexte un peu maussade que le 20 février 1960, à un peu moins de 68 ans, une hémorragie cérébrale vient brutalement mettre un terme à son existence. Cultivé, discret et fort modéré, on se demande encore ce que cet homme avait bien pu faire pour que la Belgique d’après-guerre lui témoigne d’une vindicte aussi tenace. Se pourrait-il tout simplement que l’on ait jugé, en haut lieu, qu’il en savait beaucoup trop long sur les arcanes (et les drôles de combines) de l’Occupation et qu’il fallait le discréditer à jamais ?

Christophe Dolbeau

———————————————

(1) Avec les vainqueurs de Tabora, Paris, Perrin et Cie, 1918.

(2) Le baron Pierre Nothomb (1887-1966) fut avocat mais surtout écrivain et homme politique. Leader des nationalistes belges, il sera plus tard sénateur du Parti catholique puis du Parti social-chrétien. Voy. Lionel Baland, Pierre Nothomb, Qui suis-je, Grez-sur-Loing, Pardès, 2019.

(3) Edmond Thieffry (1892-1929) était un as de l’aviation belge. En 1925, il accomplit l’exploit de rallier Léopoldville (Kinshasa) depuis Bruxelles, à bord d’un avion Handley Page W8.

(4) Jean Delville (1867-1953) était un poète et un peintre symboliste. Il enseigna son art à l’Académie royale des beaux-arts de Bruxelles entre 1907 et 1937.

(5) L’ingénieur Leonid Krassine (1870-1926) était un dirigeant bolchevik qui fut commissaire du peuple au commerce extérieur, puis ambassadeur soviétique à Paris et Londres.

(6) Fils de banquier, Maxime Litvinov ou Meir Henoch Wallach-Finkelstein (1876-1951) fut commissaire du peuple aux Affaires Étrangères et ambassadeur soviétique à Londres, puis auprès de la SDN.

(7) Le général Wladyslaw Sikorski (1881-1943) avait été, en 1920, l’un des artisans de la défaite des bolcheviks devant Varsovie. Il sera successivement chef d’état-major, Président du Conseil et ministre des affaires militaires.

(8) Pou-yi (1906-1967) fut le dernier empereur de Chine. Destitué en 1912 puis réfugié à Tianjin, il sera placé par les Japonais à la tête du « Grand État mandchou de Chine » ou Mandchoukouo (1932).

(9) Seigneur de guerre et généralissime, Tchang Tso-lin (1875-1928) sera brièvement président de la République de Chine (juin 1927-juin 1928) après avoir été longtemps le maître de la Mandchourie.

(10) Par exemple Le Maroc s’éveille (1924), Moscou dans le souffle de l’Asie (1926), La Chine est un pays charmant (1927), Le Japon et son destin (1928), La clef anglaise (1929), Beaux jours du Pacifique (1931) et Aspects du monde (1934).

(11) José Félix de Lequerica (1891-1963) fut maire de Bilbao (1938-39), puis ambassadeur d’Espagne en France, ministre des Affaires Étrangères (1944-45) et ambassadeur aux Etats-Unis (1951-54).

(12) Président du Parti Ouvrier Belge, Henri de Man (1885-1953) sera ministre des Travaux publics (1934-35) et ministre des Finances (1936-38). Condamné en 1946 à 20 ans de détention et dix millions d’amende pour avoir « servi les desseins de l’ennemi », il finira ses jours en Suisse (écrasé par un train sur une voie de chemin de fer où sa voiture s’était immobilisée).

(13) Militant socialiste, Paul-Henri Spaak (1899-1972) sera ministre des Transports et des PTT, ministre des Affaires Étrangères et Premier ministre. Il est considéré comme l’un des « pères de l’Europe ».

(14) Voy. Bernard Delcord, « À propos de quelques ‘chapelles’ politico-littéraires en Belgique (1919-1945 », Cahiers d’Histoire de la IIe Guerre mondiale, Bruxelles, Centre de Recherches et d’Études historiques de la IIe Guerre mondiale, n° 10, octobre 1986, p. 165-168.

(15) Voy. Jean-Léo, La Collaboration au quotidien – Paul Colin et le Nouveau Journal 1940-1944, Bruxelles, Racine, 2002, p. 107.

(16) Ibid, p. 109.

(17) Voy. Jean-Michel Etienne, Le mouvement rexiste jusqu’en 1940, Paris, Armand Colin, 1968, p. 73.

(18) Voy. Le Dossier du Mois, n° 12 (décembre 1963), Bruxelles, Editions du Ponant, p. 35 – extrait du chapitre XLVII des mémoires de Pierre Daye.

(19) Voy. supra, note 10.

(20) À savoir La politique coloniale de Léopold II (1918), Léopold II (1934), Vie et mort d’Albert Ier (1934), La jeunesse et l’avènement de Léopold III (1934).

(21) Par exemple Les conquêtes africaines des Belges (1918), L’Empire colonial belge (1923), Le Congo belge (1927), Congo et Angola (1929), Stanley (1936), Livingstone retrouvé par Stanley (1936),

(22) Voy. En Espagne, sous la Dictature (1925), La Belgique et la mer (1926), La Belgique maritime (1930) et L’Europe en morceaux (1932).

(23) « Le mouvement pan-nègre », Le Flambeau, 4e année, n° 7, juillet 1921, pp. 360-375 (consultable en ligne).

(24) Pierre Daye, Léon Degrelle et le rexisme, Paris, Fayard, 1937, p. 10.

(25) Le Dossier du Mois, n° 12, p. 2 – chapitre XLII des mémoires de Pierre Daye.

(26) Voy. Jean-Michel Etienne, op.cit., p. 36.

(27) Le Dossier du Mois, n° 12, p. 4 – chapitre XXXV des mémoires de Pierre Daye.

(28) Le Flamand Gustave Sap (1886-1940) était le propriétaire du journal catholique De Standaard. Député du Parti catholique, il sera ministre des Travaux publics, de l’Agriculture et du Commerce (1932-34), ministre des Finances (1934), puis de l’Économie et du Commerce (1939-40). Ses sympathies pour la droite et le rexisme entraîneront son exclusion du Parti catholique…

(29) L’avocat Hendrik Borginon (1890-1985) était l’un des dirigeants du parti nationaliste flamand VNV.

(30) Député du Parti catholique populaire flamand, Gérard Romsée (1901-1975) fut ensuite l’une des figures de proue du parti nationaliste flamand VNV. En avril 1941, il sera nommé secrétaire général à l’Intérieur et la Santé, ce qui lui vaudra d’être condamné à mort puis à la réclusion perpétuelle en 1945.

(31) Nationaliste flamand, Joris van Severen (1894-1940) fut le fondateur du mouvement solidariste thiois Verdinaso. Arrêté en 1940 sur soupçon (totalement infondé) d’appartenance à la 5e colonne, il sera sommairement abattu par des militaires français, le 20 mai, à Abbeville.