Ex: http://www.counter-currents.com

Known mostly as a novelist, memoirist, and historian, Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn had actually completed four plays before his first novel, One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich, was published in 1962. He composed his first two, Victory Celebrations and Prisoners, while a zek in the Soviet Gulag system in 1952. These Solzhenitsyn composed in verse and memorized before burning since prisoners were forbidden to own even scraps of paper. His third play, the title of which is most commonly translated into English as The Love-Girl and the Innocent, he composed outside of the gulag in 1954 while recovering from cancer. In writing Love-Girl, he rejoiced in his ability to actually type and hide his manuscript, rather than keep it all bottled up in his head. [1] [1] Solzhenitsyn composed his final play, Candle in the Wind, in 1960 in an earnest attempt to become a Soviet playwright. Where his earlier plays exposed the evil and corruption of the gulag system — and beyond that, impugned the Soviet Union for its unworkable Marxist-Leninist ideology, disastrous collectivization policies, totalitarian government, and ubiquitous cult of personality in Stalinism — Candle in the Wind avoided politics altogether. It takes place in an unspecified international setting and focuses on the dangerous effects of untrammeled technological progress on the human soul. Of all his plays, Candle in the Wind has the least relevance to the political Right. It also cannot be classified as a prison play, despite how its main character had recently been released from prison.

It would be fair to describe Solzhenitsyn’s first two prison plays as “apprentice works,” in the words of his biographer Michael Scammell. [2] [2] And this is not just in comparison to Solzhenitsyn’s most famous and successful volumes such as One Day and the sprawling Gulag Archipelago. Victory Celebrations and Prisoners do come across as uneven and amateurish. Excessive dialogue makes the reading tedious at times. Solzhenitsyn always had the historian’s impulse to explain and the prophet’s impulse to warn, and seemed to doggedly follow both impulses while writing these plays. As a result, purely narrative elements such as plot and character tend to suffer. Further, many of the themes appearing in his prison plays resurface in more complete form in both One Day and Gulag as well as in his other early novels Cancer Ward and In the First Circle.

Regardless, it is in his three prison plays where Solzhenitsyn’s conservative, Christian, ethnonationalist, and anti-Leftist outlook appears as firm as it does in his later works. It’s as if the man never changed, other than spending the last forty-eight years of his life not writing plays. Even if he had stopped writing altogether by 1960, his prison plays still would have had value to the Right for their keen perception of human nature under the most trying circumstances as well as for their conveyance of the cruelties and absurdities brought about by an oppressive communist ideology that is wholly at odds with human nature. That Solzhenitsyn had produced works that were much greater than these three plays later in his career is no reason for any student of the Right to exclude them from study.

Victory Celebrations

Burdened with a loose plot, excessive dialogue, and an awkwardly large cast of characters, Victory Celebrations (also called Feast of the Conquerors) takes place during the last days of World War II in which a Soviet artillery battalion prepares a lavish victory banquet in the Prussian mansion they had just captured. The play switches back and forth from the minor characters opining their various frustrations with the Soviet regime to what could be a political — potentially deadly — love triangle. This relationship is the heart of the play and produces its only real suspense, brief and poignant as it is.

Galina, a Russian girl living in Vienna, had traveled to Prussia to be with her fiancé who is fighting with the doomed Russian Liberation Army (a force of disgruntled Red Army POWs and anti-Soviet, pro-White Russian émigrés whom had been conscripted by the Germans). Before the story begins, however, she is captured by the battalion and convinces them that she had been a prisoner of the Germans working as a slave girl. Believing her, they invite her to take part in the upcoming celebration.

Counter-intelligence officer Gridnev, however, sees through her and suspects that she is a spy. Any Russian person who has had exposure to the enemy must be held suspect, and Gridnev quickly threatens her with imprisonment if she does not confess all. But Galina is also beautiful, and Gridnev soon finds himself falling in love (or lust) with her. This causes him to append a promise to his threats — if she sleeps with him, he’ll protect her.

While agonizing over this dilemma, Galina meets Captain Nerzhin, a childhood friend of hers. To him, she tells the truth. Nerzhin, being an honest and honorable soldier, empathizes and sees the justice in her position. How could not when Galina delivers a speech such as this?

The U.S.S.R.! It’s impenetrable forest! A forest. It has no laws. All it has is power — power to arrest and torture, with or without laws. Denunciations, spies, filling in of forms, banquets and prizewinners, Magnitogorsk and birch-bark shoes. A land of miracles! A land of worn-out, frightened, bedraggled people, while all those leaders on their rostrums. . . each one’s a hog. The foreign tourists who see nothing but well organized collective farms, Potyemkin style. The school-children who denounce their parents, like that boy Morozov. Behind black leather doors there are traps rather than rooms. Along the rivers Vychegda and Kama there are camps five times the size of France. Wherever you look you see epaulettes with that poisonous blue strip; you see widows, whose husbands are still alive. . .

Now Nerzhin faces a dilemma of his own: shepherding this woman to her fiancé just as Soviet forces are about to crush the Russian Liberation Army will not only be physically dangerous but will make himself vulnerable to a charge of treason. Can he trust anyone in his battalion? Yes, his fellows may see through the corruption and hypocrisy of the Soviet authorities or find fault with Marxism. For example, one tells the harrowing story of how a series of unjust NKVD arrests nearly wiped out an entire town. Another relays the humorous story of how, as an art student, his instructors imagined they saw a swastika in his painting. Despite this, these men wish to survive in the current system, as absurd as it is. They just don’t want to think about it, and thus choose to bow to evil.

Major Vanin says it best:

Thinking is the last thing you want to do. There is authority. There are orders. No one grows fat from thinking. You’ll get your fingers burnt from thinking. The less you know, the better you sleep. When ordered to turn that steering wheel, you turn it.

But with Galina, there is clearly so much more. During her dialogue with Nerzhin, she keeps distinguishing “us” from “them,” and soon a leitmotiv evolves involving loyalty. Galina expresses loyalty to the Russian people and never doubts herself. Nerzhin professes loyalty to the Russian nation — or, at the very least, its military. Meanwhile, Gridnev expresses loyalty to the current Russian government and its inhuman machinations as laid down by the genocidal Stalin. Of course, Gridnev never strays far from his own selfish designs.

Contemporary Soviet audiences, likely still bruising from the Second World War, would most likely have reacted negatively to the Galina character simply for her traitorous support of the RLA. Nevertheless, later audiences, even Russian ones, carry less baggage and will likely see her as the most sympathetic character in the play. At one point, she rejects the terms “Comrade” and “Citizen” and avers that the more traditional courtesy titles of “Sir” and “Madam” are more civilized. She had studied music in Vienna and remains in thrall of great Germanic classical composers such as Mozart and Haydn despite her love of Russia. Clearly, she represents the world that preceded the Soviets. She is the only tragic character in the story, since she symbolizes Solzhenitsyn’s own ethnonationalism, but only under a cloud of death or unspeakable oppression. She’s also the only character moved enough by romantic love to put herself at great risk — even if all it will amount to is her dying by her lover’s side in a hail of artillery fire.

Solzhenitsyn could express his sympathy for this heartbreaking character (and presage the stirring ending of his story Matryona’s House) no better than in the admiring words of Nerzhin:

“I’ve no fears for the fate of Russia while there are women like you.”

Prisoners

Originally titled Decembrists Without December, Prisoners suffers to a greater extent than Victory Celebrations from a thin, meandering plot, a bloated dramatis personae, and excessive dialogue. It lacks even the scraps of narrative formalism found in the earlier play, and instead resembles the dialogues of Plato for of its reliance upon dialectic. The events take place in a gulag wherein the mostly-male cast discuss the absurdities of Soviet oppression, argue the merits and demerits of communism, and endure ludicrous interrogations from counter-intelligence officers. Most of the characters were based on people Solzhenitsyn himself knew. Further, several of the characters appear in later, more famous works, such as Vorotyntsev (The Red Wheel), Rubin (In the First Circle), and Pavel Gai (The Love-Girl and the Innocent).

While much weaker than Victory Celebrations in terms of plot, character, and resolution, Prisoners far surpasses it in astute political commentary as well as in philosophical and historical discourse. In its many debates, Solzhenitsyn does not always demonize the representatives of the Soviet system and sometimes puts wise, thoughtful, or otherwise honest words in their mouths. This leads to some fascinating reading (as opposed to what would seem like tedious chatting onstage). On the whole, however, Prisoners devastates the Soviet Union in a way that would have invited much more than mere censure in that repressive regime. Solzhenitsyn had to keep the play close to his chest for many years, and revealed its existence only after his exile in the West during the 1970s. Had the KGB ever acquired the play, it is likely there would not have been an exile for Solzhenitsyn at all.

Due to the narrative’s unmoored rambling, examples of Solzhenitsyn’s incisive observations can appear with little context and in list form. The relevance to the broader struggle of the Right in all cases should become clear.

We clutch at life with convulsive intensity — that’s how we get caught. We want to go on living at any, any price. We accept all the degrading conditions, and this way we save — not ourselves — we save the persecutor. But he who doesn’t value his life is unconquerable, untouchable. There are such people! And if you become one of them, then it’s not you but your persecutor who’ll tremble!

Far too many on the Right today meekly accept the degrading, second-class citizenship imposed upon us by the racial egalitarian Left. If more of us could value our lives a little less and the Truth a little more, perhaps this unnatural state of affairs could be overturned.

Here, now, we’re all traitors to our country. Cut down the raspberries — mow down the blackcurrants. But that’s not what I got arrested for. I got arrested for infringing on the regulations. I issued extra bread to the collective farm women. Without it, they would have died before the spring. I wasn’t doing it for my own good — I had enough food at home.

Aside from revealing the murderous lack of concern that the Soviet authorities had for their own people, this passage reveals how the Left does not merely value some lives over others but becomes by policy quite hostile to those lives it values least. In today’s struggles, whites in the West who act in their racial interests are meeting with increasing hostility from our Leftist elites, while these same elites actively encourage non-whites to act in their racial interests.

Of course, Solzhenitsyn’s proud ethnonationalism (as expressed by his angst-filled love for Russia) shines through the text as well.

They are ringing the bell. They are ringing for Vespers. . . O Russia, can this ever come back again? Will you ever be yourself? I have lived on your soil for twenty-six years, I spoke Russian, listened to Russian, but never knew what you were, my country! . . .

In some cases, the dialogue becomes downright witty. Take, for example, the absurd interrogation scene between intelligence officer Mymra and Sergeant Klimov, who had been captured in battle by the Germans:

Mymra: Prisoner Klimov. You are here to answer questions, not to ask them. You could be locked up in a cell for refusing to answer questions. Personally, we are ready to die for our leader. Question three: what was your aim when you gave yourself up? Why didn’t you shoot yourself?

Klimov: I was waiting to see if the Divisional Commander would shoot himself first. However, he managed to escape to Moscow by ‘plane out of the encirclement and then got promoted.

Mymra (writing down): Answer. I gave myself up, my aim being to betray my socialist country. . .

Klimov: We-ell, well. You can put it like that…

The Rubin character in Prisoners is no different than his namesake in In the First Circle — a friendly, erudite apologist for communism, and clearly Jewish. Just as in the novel, Prisoner’s Rubin insists that he’d been incarcerated by mistake and that, regardless of his personal circumstances, he remains a true believer in the Soviet system. At one point, in the middle of the play, he is beset upon by his angry co-inmates who challenge him to defend Soviet atrocities such as blockading Ukraine and starving millions into submission. Rubin explains that the great socialist revolutions and slave rebellions of the past had failed because they showed too much leniency towards their former oppressors. They doubted the justice of their cause. He then praises the Soviet Revolution as the product of “unconquerable” science and laments that it has had only twenty-five years to produce results.

. . . you unhappy, miserable little people, whose petty lives have been squeezed by the Revolution, all you can do is distort its very essence, you slander its grand, bright march forward, you pour slops over the purple vestments of humanity’s highest dreams!

Rubin fixates upon the same wide, historical vista that all Leftists do when they wish to explain away failure or atrocity. Conservative debunking of this arrogant folly is as old as Edmund Burke. In Solzhenitsyn’s case, however, he depicts it with almost cringe-worthy realism when he humanizes Rubin as a reasonable and enthusiastic, if misguided, adherent of the Left. We actually grow to like Rubin, especially at the end of the play when he leads a choir of zeks in song as Vorotyntsev contemplates his fate with the others.

The most memorable scene in Prisoners occurs towards the end when Vorotyntsev debates a dying counter-intelligence officer named Rublyov. In this debate we have perhaps Solzhenitsyn’s most eloquent affirmation of the Right as a way of life, and not just as a reaction to the totalitarian Left. Vorotyntsev claims to have fought in five wars on the side of Monarchy or Reaction — all of which were ultimately lost: the Russian-Japanese War, World War I, the Russian Civil War, the Spanish Civil War, World War II (on the side of the Russian Liberation Army). When Rublyov taunts him for this colossal losing streak, Vorotyntsev speaks of “some divine and limitless plan for Russia which unfolds itself slowly while our lives are so brief” and then responds that he never wavered in his fight against the Left because he felt the truth was always on his side. All that Rublyov ever had on his side was ideology. He explains:

You persecuted our monarchy, and look at the filth you established instead. You promised paradise on earth, and gave us Counter-Intelligence. What is especially cheering is that the more your ideas degenerate, the more obviously all your ideology collapses, the more hysterically you cling to it.

When Rublyov accuses the Right of having its own executioners, Vorotyntsev responds, “not the same quantity. Not the same quality,” and proceeds to compare the twenty thousand political prisoners of the Tsar to the twenty million political prisoners of the Soviets.

The horror is that you grieve over the fate of a few hundred Party dogmatists, but you care nothing about twelve million hapless peasants, ruined and exiled in the Tundra. The flower, the spirit of an annihilated nation do not exude curses on your conscience.

In this, Vorotyntsev makes the crucial point of the Right’s moral superiority to the Left. Note his similarity to Rubin in positing a plan as broad as history. For Rubin, however, it is Man’s plan, an atheist’s plan. It is hubris in action, a contrivance of pride. For Vorotyntsev, on the other hand, it is God’s plan — not something he can begin to understand. All he can do is to live according to Truth as he sees it and according to his nature as a human being.

It’s hard to find a more stark distinction between Left and Right than this.

The Love-Girl and the Innocent

Of Solzhenitsyn’s prison plays, The Love-Girl and the Innocent works best. This perhaps explains why it has been staged most often and continues to be put on today. Notably, the BBC produced a television adaptation of Love-Girl in 1973. Love-Girl resembles most closely what most people expect when they read or see a play: Four acts; a beginning, middle, and end; three-dimensional, evolving characters; and a plot filled with conflict, action, and suspense. We could quibble with some of Solzhenitsyn’s authorial choices, such as making the lead character Nerzhin too passive towards the end, employing too many characters (again), or his general lack of focus regarding some of the plot. Nevertheless, that Solzhenitsyn manages to pursue many of the profound themes from Victory Celebrations and Prisoners to their poignant conclusions in Love-Girl as well as explore new ones that would reach their apotheosis in later works such as Gulag Archipelago makes Love-Girl and the Innocent, in this reviewer’s opinion, the first of Solzhenitsyn’s great narrative works.

As in Victory Celebrations, we have a potentially deadly love triangle — but one that achieves greater meaning since the audience can now experience the love and all its wide-ranging consequences. In Victory Celebrations, the story takes place during a lull in the action, with all the real action having already happened or will happen in the near future. The battalion had just captured a mansion and plans to advance on the RLA’s position the next day. By the play’s end, Galina’s fate swings between Gridnev’s protection and Nerzhin’s. Will she become Gridnev’s mistress? Will she be shot or be incarcerated in a gulag? Will Nerzhin take her to her fiancé before the Soviet forces attack? Will she even survive? Note also how this love triangle is not entirely real since Nerzhin, despite his demonstrable affection for Galina, can only serve as a stand-in for her fiancé.

In Love-Girl, all the appropriate action happens on stage and in the here and now. There are no stand-ins. It takes place in a gulag in 1945 where the love is real, agonizing, and immediate. It is also multifaceted, since there are technically two love triangles occurring simultaneously. The “love-girl” of the title is a beautiful and compassionate female inmate named Lyuba, while the “innocent” is Rodion Nemov, an officer recently taken in from the front who is committed to behaving as honorably as possible while in the gulag. The third point in the triangle is Timofey Mereshchun, the prison’s fat, repulsive doctor who promises Lyuba privileges and protection in return for sex. He also has the power to send her off to camps in much harsher climates where her chances of survival would become drastically reduced.

The other love triangle involves another beautiful female inmate named Granya. She is a former Red Army sniper incarcerated not for political reasons, like many of the others, but because she murdered her husband while on furlough after finding him in flagrante delicto with another woman. It’s as if Solzhenitsyn could not decide which woman he was in love with more while writing the play. The men vying for Granya’s affections are an honest and feisty bricklaying foreman named Pavel Gai (first seen in Prisoners) and the corrupt and cruel camp commandant Boris Khomich.

Aside from Solzhenitsyn’s now-familiar themes of ethnonationalism, ethno-loyalty, exposing Soviet atrocities, and impugning communist ideology, Love-Girl also introduces the theme of honor vs. corruption. When the play begins, Nemov is responsible for increasing efficiency in prison work. And he does a fine job, noting how the camp authorities could increase productivity by easing up on the harsh exploitation of the prisoners and cutting much of the self-serving and politically-appointed administrative personnel. He quickly runs afoul of the shady and perfidious ruling class of the camp, however, when he demands that the bookkeeper Solomon turn over a recent shipment of boots to the workers rather than divvy them up among his cronies.

Solomon, along with Mereshchun and Khomich, take their revenge soon after when they manipulate the drunken and irresponsible camp commandant Ovchukhov into transferring Nemov to general work duties while replacing him with the depraved Khomich. In the battle between honor and corruption, honor never has a chance. And, as if to infuriate the audience even further, Solzhenitsyn reveals how Khomich has a few ideas for the commandant, all of which involve increasing the corruption in the camp and turning the screws harder on the prisoners. These ideas include:

- Issuing the minimum bread guarantee after 101 percent work fulfillment, instead of 100 percent.

- Forcing the workers to over-fulfill their work requirements to have an extra bowl of porridge.

- Not allowing prisoners to receive parcels from the post office unless they have fulfilled 120 percent of their work norms.

- Not allowing men and women to meet unless they have fulfilled 150 percent of their work norms.

- Building a grand house for Commandant Ovchukhov in time for the anniversary of the October Revolution.

Khomich puts it succinctly and smugly: “They’ll realize: either work like an ox or drop dead.”

The Love-Girl and the Innocent is also notable because of how Solzhenitsyn employs its Jewish characters. Prisoners’ Rubin certainly defends the Soviet orthodoxy and the atrocities it entailed. But at least he’s honest, thoughtful, and friendly about it — which certainly counterbalances some of the audience’s negative feelings for him. Love-Girl’s Jews, however, are not only ugly, corrupt, and cruel, they’re stereotypical as well.

Scammell, in summarizing Jewish-Soviet émigré Mark Perakh’s analysis [3] [5] of Solzhenitsyn’s supposed anti-Semitism, writes:

It was in certain of Solzhenitsyn’s other works, however, the Perhakh found the most to criticize, notably in Solzhenitsyn’s early play The Tenderfoot and the Tart. [4] [6] Again, the three Jews in the play — Arnold Gurvich, Boris Khomich, and the bookkeeper named Solomon — were all representatives of evil, but this time grossly and disgustingly so, and Solomon was the very incarnation of the greedy, crafty, influential “court Jew,” manipulating the “simple” Russian camp commandant and oozing guile and corruption. As it happened, Solomon was modeled on the real-life prototype of Isaak Bershader, [5] [7] whom Solzhenitsyn had met at Kaluga Gate and later described at length in volume 3 of The Gulag Archipelago. . . [6] [8]

Solzhenitsyn’s habit during his early period was to include characters based on people he personally knew. In this reviewer’s opinion, he often did so to the detriment of the work itself. Why include such a bewildering array of characters in his already wordy volumes when he could have condensed them into fewer characters for more pithy and forceful results? In some cases, Solzhenitsyn didn’t even bother to change his characters’ names: for example, the fervent Christian Evgeny Divnich (Prisoners) and the Belgian theater director Camille Gontoir (Love-Girl).

Thus, when Solzhenitsyn portrays gulag Jews doing evil things in recognizably Jewish ways, it’s probably because he was being true to what he witnessed in the gulag. It was not Solzhenitsyn’s style to invent a Shylock or Fagin out of thin air just to annoy Jewish people, just as he did not employ anti-Russian stereotypes for the sake of stereotyping. He portrays the Russian thieves in Love-Girl as particularly vile. And the simple-minded, corrupt, and drunken commandant Ovchukhov is no better. There should be no doubt that prisoner Solzhenitsyn had known and dealt with the flesh-and-blood prototypes of many of the characters appearing in his plays.

Regardless, that Solzhenitsyn refused to self-censor his negative Jewish characters while also refusing to include positive ones for the sake of political correctness should tell us something about the ethnocentric line he drew between Russians and Jews. He did not consider Jews as Russians, and he did not care if certain Jews got upset over this. If being labeled an anti-Semite by some is the price to pay for his honesty, his rejection of civic nationalism, and his profound love for his nation and his people, then so be it. [7] [9]

There is quite a bit in The Love-Girl and the Innocent that will resonate with the Right. It was probably unintended by Solzhenitsyn that such a meta-analysis of the Jewish Question would do so as well.

If you want to support our work, please send us a donation by going to our Entropy page [10] and selecting “send paid chat.” Entropy allows you to donate any amount from $3 and up. All comments will be read and discussed in the next episode of Counter-Currents Radio, which airs every Friday.

Don’t forget to sign up [11] for the twice-monthly email Counter-Currents Newsletter for exclusive content, offers, and news.

Notes

[1] [12] Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, The Oak and the Calf. New York: Harper & Row, 1975, p. 4.

[2] [13] Michael Scammell, Solzhenitsyn: A Biography. New York: W. W. Norton and Company, 1984, p. 330.

[3] [14] Scammell writes of Perakh’s analysis (page 960):

Perakh’s article, a kind of summa of those that had gone before, had appeared in Russian in the émigré magazine Vrennia i My (Time and We) in February 1976 before being published in English in Midstream.

[4] [15] The Love-Girl and the Innocent appears under several titles in English. These include The Tenderfoot and the Tart (as preferred by Scammell), The Greenhorn and the Camp-Whore, and The Paragon and the Paramour. Scammell (on page 217) has this to say about it:

The question of what to call this play in English is problematical. Solzhenitsyn’s Russian title Olen’ I shalashovka is based on camp slang. Olen’ (literally “deer”) means a camp novice, and shalashovka (derived from shalash, meaning a rough hunter’s cabin or bivouac) means a woman prisoner who agrees to sleep with a trusty or with trusties in exchange for food and privileges—not quite a whore, more a tart or tramp. The published English title The Love-Girl and the Innocent seems to me to catch none of this raciness.

[5] [16] I believe that both Scammell and Solzhenitsyn biographer D.M. Thomas overlooked something regarding Solzhenitsyn’s basing of Solomon on Bershader in Love-Girl. It seems to me that Solzhenitsyn based both the bookkeeper Solomon and the doctor Mereshchun on Bershader. The connection with Solomon is based on their shared profession (bookkeeping) and the fact that they were both corrupt, cunning, manipulative trusties in the gulag. But Solomon only appears in two scenes in Love-Girl and has nothing to do with any of the female inmates (Thomas falsely claims that Solomon was “adept at corrupting women prisoners”). The episode with Bershader in The Gulag Archipelago depicts him laying siege to and ultimately corrupting a beautiful and virtuous Russian woman prisoner, which Solomon does not do. Bershader is also described by Solzhenitsyn as “a fat, dirty old stock clerk” who is “nauseating in appearance.” Solzhenitsyn first describes Solomon, on the other hand, as carrying himself “with great dignity” and looking “sharp by camp standards.” Later, he describes Solomon as “very neatly dressed.”

On the other hand, Mereshchun is described as a “fat, thick-set fellow,” which is more in keeping with Bershader’s appearance. Further, Mereshchun enthusiastically corrupts the female inmates. In fact, in his first line of dialogue, he announces: “I cannot sleep without a woman.” After being reminded that he had kicked his last woman out of bed, he responds, “I’d had enough of her, the shit bag.” Clearly, Mereshchun is as revolting as Bershader. He also engages in the same exploitive behavior with women. Could Mereshchun also have been based on Bershader?

In a curious moment in Love-Girl, Solzhenitsyn describes how Mereshchun immediately strikes up a friendship with Khomich the moment he meets him. It was as if they recognized and understood each other without the need of a formal introduction. Could it be that in Solzhenitsyn’s mind they were both Jewish? It’s hard to say. Mereshchun is an odd name, but it could be a Russianized Jewish one, and in the Soviet Union during that time, doctors were disproportionately Jewish. On the other hand, few Russian Jews would be named Timofey. Perhaps Solzhenitsyn meant for this character to have enigmatic origins.

M. Thomas, Alexander Solzhenitsyn: A Century in his Life. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1998, p. 492.

[6] [17] Scammell, pp. 960-961.

[7] [18] Thomas (page 490) conveys an astonishingly hysterical example of gentile-bashing from Jewish writer Lev Navrozov who really did not like Solzhenitsyn:

An émigré from 1972, Navrozov denounced Solzhenitsyn’s “xenophobic trash.” He is “a Soviet small-town provincial who doesn’t know any language except his semiliterate Russian and fantasizes in his xenophobic insulation”; August 1914 was as intellectually shabby as The Protocols of the Elders of Zion — but that turn-of-the-century forgery, purporting to show that the Jews were plotting world domination, was actually “superior” in its language to the Solzhenitsyn. . . . His style shows a “comical ineptness”; Navrozov writes that when Ivan Denisovich appeared, he thought its author might develop into a minor novelist, but Khrushchev’s use of him to strike the Stalinists, and his subsequent persecution, made him strut like a bearded Tolstoy, so “this semiliterate provincial, who has finally found his vocation — anti-Semitic hackwork — has been sensationalized into an intellectual colossus. . .

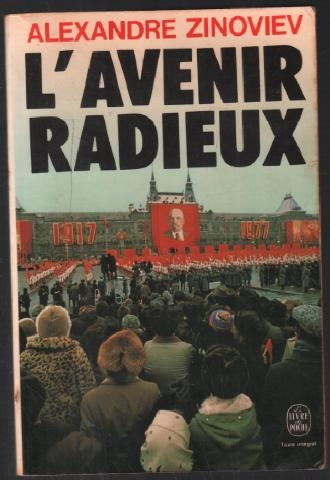

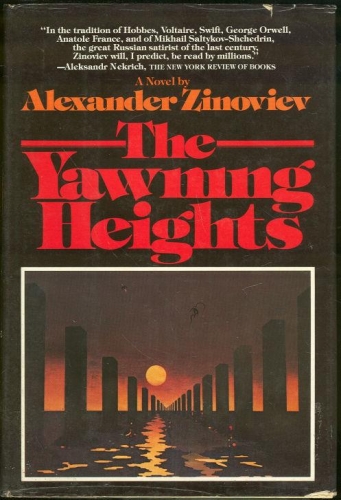

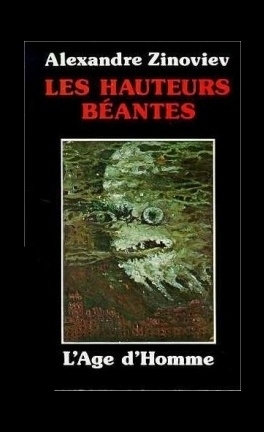

Zinoviev décrit très bien le redoutable mondialisme qui naît du défunt et redouté communisme :

Zinoviev décrit très bien le redoutable mondialisme qui naît du défunt et redouté communisme :

A la fin des années 90 les socialistes sont de pures canailles (voyez aussi les excellents pamphlets de Guy Hocquenghem et de mon éditeur Thierry Pfister qui datent des années 80) :

A la fin des années 90 les socialistes sont de pures canailles (voyez aussi les excellents pamphlets de Guy Hocquenghem et de mon éditeur Thierry Pfister qui datent des années 80) :

« En littérature, c’est la même chose. La domination mondiale s’exprime, avant tout, par le diktat intellectuel ou culturel si vous préférez. Voilà pourquoi les Américains s’acharnent depuis des décennies à faire baisser le niveau culturel et intellectuel du monde : ils veulent baisser au leur pour pouvoir exercer ce diktat. »

« En littérature, c’est la même chose. La domination mondiale s’exprime, avant tout, par le diktat intellectuel ou culturel si vous préférez. Voilà pourquoi les Américains s’acharnent depuis des décennies à faire baisser le niveau culturel et intellectuel du monde : ils veulent baisser au leur pour pouvoir exercer ce diktat. »

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

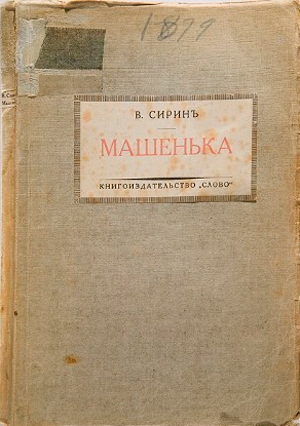

His first Russian literary publications, signed with pseudonym Syrin (the name of the mythological paradise bird), were printed by emigrant press (“Mashenka”, “The Defence”). Some short stories and lyrical poems where he depicted the drama and tragedy of the Russian refugees, the downfall of their first hopes and their despair (an emigrant chess-player Luzhin in “The Defence” committed a suicide by jumping out of the window) were accepted with understanding by readers. One of them was Ivan Bunin, the Noble Prize winner for literature and one of Nabokov’s authorities of that time.

His first Russian literary publications, signed with pseudonym Syrin (the name of the mythological paradise bird), were printed by emigrant press (“Mashenka”, “The Defence”). Some short stories and lyrical poems where he depicted the drama and tragedy of the Russian refugees, the downfall of their first hopes and their despair (an emigrant chess-player Luzhin in “The Defence” committed a suicide by jumping out of the window) were accepted with understanding by readers. One of them was Ivan Bunin, the Noble Prize winner for literature and one of Nabokov’s authorities of that time. “The Gift” ’s author doesn’t say many words about his favorite writers in a direct way. You just see their reflections or allusions to their aesthetics, feel their invisible breathing. At the same time he dedicates the whole chapter 4 to the biography of Nikolai Chernyshevskiy, a famous revolutionary-populist (narodnik) and a spiritual father in the person of Lenin that becomes the negative center of the novel. Nabokov follows the example of Dostoevskiy’s “Demons” and gives a caricature portrait of the revolutionary, but he makes it in a different manner. Not to be boring, Nabokov retells the Cherdyntsev’s utilitarian and socially limited ideas in the black ironic verse.

“The Gift” ’s author doesn’t say many words about his favorite writers in a direct way. You just see their reflections or allusions to their aesthetics, feel their invisible breathing. At the same time he dedicates the whole chapter 4 to the biography of Nikolai Chernyshevskiy, a famous revolutionary-populist (narodnik) and a spiritual father in the person of Lenin that becomes the negative center of the novel. Nabokov follows the example of Dostoevskiy’s “Demons” and gives a caricature portrait of the revolutionary, but he makes it in a different manner. Not to be boring, Nabokov retells the Cherdyntsev’s utilitarian and socially limited ideas in the black ironic verse. He finished the book of memories – its first title “Conclusive Evidence” (1951) – later changed into “Speak, Memory” by the author -, where he described in a pure classic manner his happy childhood in a family village Rozhdestveno near St. Petersburgh, portrayed with infinite tender his parents and represented the general life atmosphere of a good old pre-revolutionary Russia.

He finished the book of memories – its first title “Conclusive Evidence” (1951) – later changed into “Speak, Memory” by the author -, where he described in a pure classic manner his happy childhood in a family village Rozhdestveno near St. Petersburgh, portrayed with infinite tender his parents and represented the general life atmosphere of a good old pre-revolutionary Russia. Nabokov tried to defend himself. He said that “Lolita” couldn’t be considered as anti-American. While composing the story, he tried to be an American writer. What one should bear in mind he was not a realistic author, he wrote fiction. It had taken Nabokov some forty years to invent Russia and Western Europe. And at that moment he faced the task of inventing America. He didn’t like Humbert Humbert. Indeed that character was not an American citizen, he was a foreigner and an anarchist. Nabokov disagreed with him in many ways, besides, nymphets like his, disagreed, for example, with Freid or Marx.

Nabokov tried to defend himself. He said that “Lolita” couldn’t be considered as anti-American. While composing the story, he tried to be an American writer. What one should bear in mind he was not a realistic author, he wrote fiction. It had taken Nabokov some forty years to invent Russia and Western Europe. And at that moment he faced the task of inventing America. He didn’t like Humbert Humbert. Indeed that character was not an American citizen, he was a foreigner and an anarchist. Nabokov disagreed with him in many ways, besides, nymphets like his, disagreed, for example, with Freid or Marx. Nabokov’s critical biography by Nikolai Gogol (a non-Christian interpretation of a Christian author were the first books, published in the Soviet Union. But his “Lectures on Russian Literature”, “Lecture on Literature” (on Western Europe), “Strong Opinions” where he collected some interviews, letters and articles were unknown until post-soviet times.

Nabokov’s critical biography by Nikolai Gogol (a non-Christian interpretation of a Christian author were the first books, published in the Soviet Union. But his “Lectures on Russian Literature”, “Lecture on Literature” (on Western Europe), “Strong Opinions” where he collected some interviews, letters and articles were unknown until post-soviet times.

Rozanov développe sa pensée religieuse : elle n’est pas directement centrée sur l’Eglise orthodoxe, qu’il n’abandonnera toutefois jamais, car, malgré ses lacunes et ses travers, elle réserve pour ses fidèles un espace de chaleur inégalée : on y enterre ses parents, ses proches, on y marie ses enfants. Le corps de l’Eglise, ce sont ses rites qui rythment la vie, celle du foyer, du nid. D’emblée, on le voit, la critique antireligieuse de Rozanov n’est pas celle des positivistes et des libéraux, dont il perçoit les idées comme également pétrifiées ou en voie de pétrification. Le noyau central de sa critique de l’orthodoxie russe est vitaliste. La doctrine chrétienne est hostile à la vie, au désir. Elle s’est détachée de l’« arbre de la vie », alors que l’Ancien Testament, qu’il revalorise, y était étroitement attaché. L’Evangile, qui, pour lui est un poison mais non au sens où l’entendait Maurras, véhicule une profonde tristesse, un deuil permanent. Il n’est pas tellurique, encore moins phallique. Il méconnait le rire et l’amour charnel, seul amour véritable. Mais fidèle à sa manière de dire aussi, et dans la foulée même de ses écrits provocateurs, le contraire de ce qu’il vient d’affirmer, Rozanov chante les vertus du monachisme européen, générateur d’un être hermaphrodite et monacal, qui est parvenu à sublimer à l’extrême les instincts vitaux et, par là même, à générer la civilisation en Europe. Ce monachisme créateur a toutefois cédé le pas à l’infertilité évangélique en Europe, si bien qu’à terme tout deviendra « ombre ». Ce n’eut pas été possible si la religion avait été plus charnelle, plus solaire, plus fidèle aux cultes antiques de la fertilité, dixit Rozanov, l’inclassable, car le soleil est là, est l’élément le plus patent du réel (sans double), sans lequel aucune vie, ni élémentaire ni monacale n’est possible, sans lequel les liturgies cycliques n’ont aucun sens. Comme David Herbert Lawrence, Rozanov réclame un retour de la religion au cosmos pour que la théologie ne soit plus un grouillement sec de radotages syllogistiques mais la voix du peuple paysan qui chante le retour du printemps.

Rozanov développe sa pensée religieuse : elle n’est pas directement centrée sur l’Eglise orthodoxe, qu’il n’abandonnera toutefois jamais, car, malgré ses lacunes et ses travers, elle réserve pour ses fidèles un espace de chaleur inégalée : on y enterre ses parents, ses proches, on y marie ses enfants. Le corps de l’Eglise, ce sont ses rites qui rythment la vie, celle du foyer, du nid. D’emblée, on le voit, la critique antireligieuse de Rozanov n’est pas celle des positivistes et des libéraux, dont il perçoit les idées comme également pétrifiées ou en voie de pétrification. Le noyau central de sa critique de l’orthodoxie russe est vitaliste. La doctrine chrétienne est hostile à la vie, au désir. Elle s’est détachée de l’« arbre de la vie », alors que l’Ancien Testament, qu’il revalorise, y était étroitement attaché. L’Evangile, qui, pour lui est un poison mais non au sens où l’entendait Maurras, véhicule une profonde tristesse, un deuil permanent. Il n’est pas tellurique, encore moins phallique. Il méconnait le rire et l’amour charnel, seul amour véritable. Mais fidèle à sa manière de dire aussi, et dans la foulée même de ses écrits provocateurs, le contraire de ce qu’il vient d’affirmer, Rozanov chante les vertus du monachisme européen, générateur d’un être hermaphrodite et monacal, qui est parvenu à sublimer à l’extrême les instincts vitaux et, par là même, à générer la civilisation en Europe. Ce monachisme créateur a toutefois cédé le pas à l’infertilité évangélique en Europe, si bien qu’à terme tout deviendra « ombre ». Ce n’eut pas été possible si la religion avait été plus charnelle, plus solaire, plus fidèle aux cultes antiques de la fertilité, dixit Rozanov, l’inclassable, car le soleil est là, est l’élément le plus patent du réel (sans double), sans lequel aucune vie, ni élémentaire ni monacale n’est possible, sans lequel les liturgies cycliques n’ont aucun sens. Comme David Herbert Lawrence, Rozanov réclame un retour de la religion au cosmos pour que la théologie ne soit plus un grouillement sec de radotages syllogistiques mais la voix du peuple paysan qui chante le retour du printemps.  La disparition du cadre doux du domostroï et l’a-cosmicité, l’anti-vitalisme, de la religion officielle sont les vecteurs du déclin final de la civilisation européenne. Sans vitalité naturelle, une civilisation n’a plus l’énergie d’agir ni la force de résister. Elle a perdu toute étincelle divine. Lev Gumilev, qui déplore la disparition des passions, Edouard Limonov, récemment décédé, qui parle d’un Occident devenu un « grand hospice », Alexandre Douguine, qui développe sa critique particulière de l’Occident, sont des échos lointains de ce vitalisme de Rozanov. Préfigurant également Heidegger, Rozanov déplore l’envahissement de nos foyers par l’opinion publique/médiatique, qui décentre nos attentions et disloque la cohérence de nos nids. Nous sommes dans un processus de « sociétarisation » qui détruit les communautés archaïques, dissout les ciments irrationnels et les remplace par un bla-bla intellectuel pseudo-rationnel. La politique est dès lors dominée par cet intellectualisme infécond et tout ce qu’elle produit comme idéologies ou comme programmes mérite le mépris. Rozanov formule donc un credo apolitique. Si la révolution bolchevique, survenue pendant la rédaction des Feuilles tombées, réussit à bouleverser de fond en comble l’édifice impérial tsariste, c’est parce qu’elle est portée par la vitalité des moujiks qui se sont engagés dans l’Armée Rouge. La révolution est une manifestation de la jeunesse, écrit-il, qui veut autre chose qu’un empire sclérosé.

La disparition du cadre doux du domostroï et l’a-cosmicité, l’anti-vitalisme, de la religion officielle sont les vecteurs du déclin final de la civilisation européenne. Sans vitalité naturelle, une civilisation n’a plus l’énergie d’agir ni la force de résister. Elle a perdu toute étincelle divine. Lev Gumilev, qui déplore la disparition des passions, Edouard Limonov, récemment décédé, qui parle d’un Occident devenu un « grand hospice », Alexandre Douguine, qui développe sa critique particulière de l’Occident, sont des échos lointains de ce vitalisme de Rozanov. Préfigurant également Heidegger, Rozanov déplore l’envahissement de nos foyers par l’opinion publique/médiatique, qui décentre nos attentions et disloque la cohérence de nos nids. Nous sommes dans un processus de « sociétarisation » qui détruit les communautés archaïques, dissout les ciments irrationnels et les remplace par un bla-bla intellectuel pseudo-rationnel. La politique est dès lors dominée par cet intellectualisme infécond et tout ce qu’elle produit comme idéologies ou comme programmes mérite le mépris. Rozanov formule donc un credo apolitique. Si la révolution bolchevique, survenue pendant la rédaction des Feuilles tombées, réussit à bouleverser de fond en comble l’édifice impérial tsariste, c’est parce qu’elle est portée par la vitalité des moujiks qui se sont engagés dans l’Armée Rouge. La révolution est une manifestation de la jeunesse, écrit-il, qui veut autre chose qu’un empire sclérosé.

Anna Calosso :

Anna Calosso :

Anna Calosso :

Anna Calosso :

Extraits de Z. Marcas, petite nouvelle méconnue, prodigieuse. On commence par la chambre de bonne :

Extraits de Z. Marcas, petite nouvelle méconnue, prodigieuse. On commence par la chambre de bonne : Comme Stendhal, Chateaubriand et même Toussenel, Balzac sera un nostalgique de Charles X :

Comme Stendhal, Chateaubriand et même Toussenel, Balzac sera un nostalgique de Charles X : Il y a une vingtaine d’années j’avais rappelé à Philippe Muray que chez Hermann Broch comme chez Musil (génie juif plus connu mais moins passionnant) il y avait une dénonciation de la dimension carnavalesque dans l’écroulement austro-hongrois.

Il y a une vingtaine d’années j’avais rappelé à Philippe Muray que chez Hermann Broch comme chez Musil (génie juif plus connu mais moins passionnant) il y avait une dénonciation de la dimension carnavalesque dans l’écroulement austro-hongrois. Puis Balzac explique l’homme moderne, électeur, citoyen, consommateur, politicard, et « ce que Marcas appelait les stratagèmes de la bêtise : on frappe sur un homme, il paraît convaincu, il hoche la tête, tout va s’arranger ; le lendemain, cette gomme élastique, un moment comprimée, a repris pendant la nuit sa consistance, elle s’est même gonflée, et tout est à recommencer ; vous retravaillez jusqu’à ce que vous ayez reconnu que vous n’avez pas affaire à un homme, mais à du mastic qui se sèche au soleil. »

Puis Balzac explique l’homme moderne, électeur, citoyen, consommateur, politicard, et « ce que Marcas appelait les stratagèmes de la bêtise : on frappe sur un homme, il paraît convaincu, il hoche la tête, tout va s’arranger ; le lendemain, cette gomme élastique, un moment comprimée, a repris pendant la nuit sa consistance, elle s’est même gonflée, et tout est à recommencer ; vous retravaillez jusqu’à ce que vous ayez reconnu que vous n’avez pas affaire à un homme, mais à du mastic qui se sèche au soleil. »

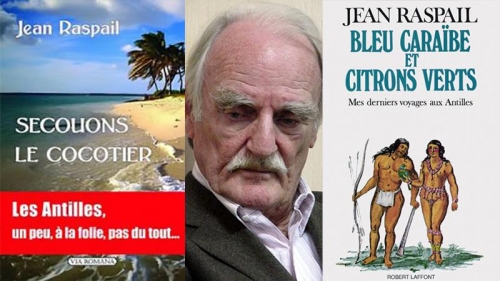

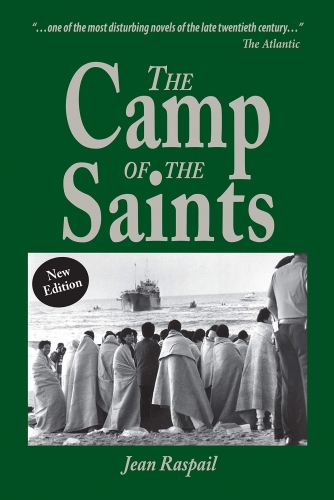

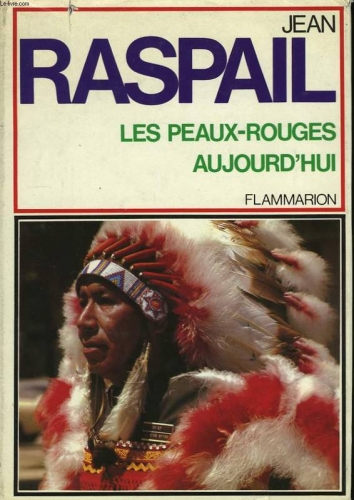

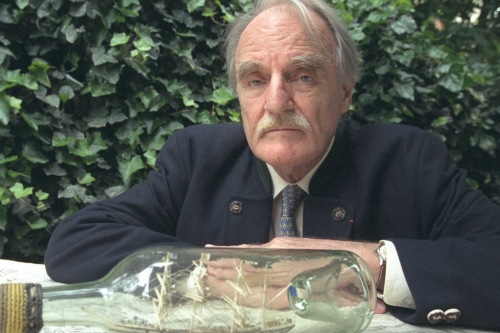

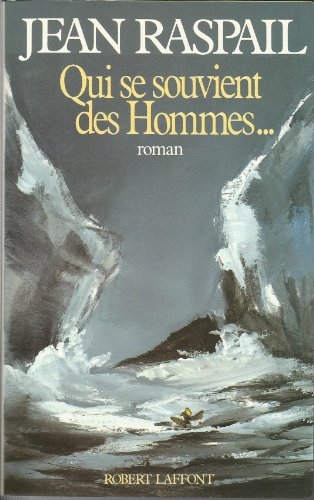

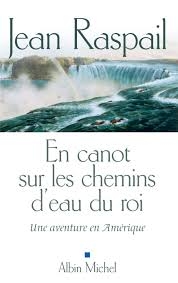

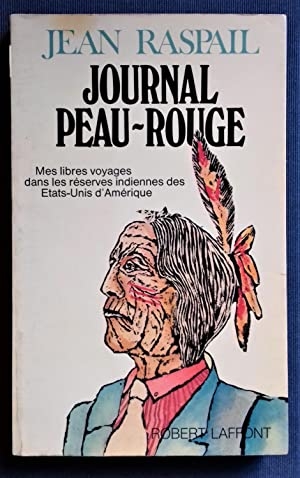

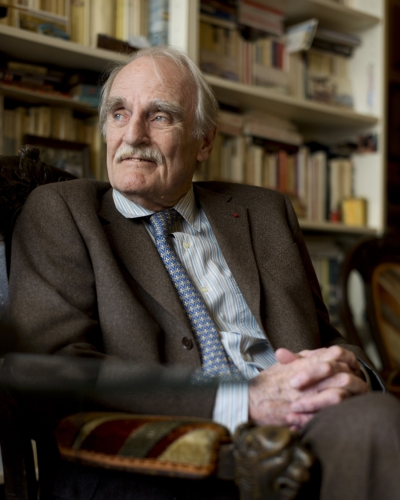

Tout au long de ses périples, il s’attache au sort des derniers peuples de moins en moins préservés de la modernité. Dans Qui se souvient des Hommes… (Robert Laffont, 1986), il retrace d’une manière poignante la fin des Alacalufs. Avec son extraordinaire Journal peau-rouge (1975, réédition en 2011 chez Atelier Fol’Fer), il témoigne de la situation inégale des tribus amérindiennes parquées dans les réserves. Certaines s’y étiolent et aspirent seulement à la fin de l’histoire. D’autres, les Navajos par exemple, formulent, grâce à l’exploitation des ressources naturelles, de grandes ambitions comme devenir le cinquante et unième État des États-Unis. Jean Raspail se plaît à romancer ses explorations quasi-anthropologiques dans La Hache des Steppes (1974, réédition en 2016 chez Via Romana), dans Les Hussards (Robert Laffont, 1982) et dans Pêcheurs de Lune (Robert Laffont, 1990).

Tout au long de ses périples, il s’attache au sort des derniers peuples de moins en moins préservés de la modernité. Dans Qui se souvient des Hommes… (Robert Laffont, 1986), il retrace d’une manière poignante la fin des Alacalufs. Avec son extraordinaire Journal peau-rouge (1975, réédition en 2011 chez Atelier Fol’Fer), il témoigne de la situation inégale des tribus amérindiennes parquées dans les réserves. Certaines s’y étiolent et aspirent seulement à la fin de l’histoire. D’autres, les Navajos par exemple, formulent, grâce à l’exploitation des ressources naturelles, de grandes ambitions comme devenir le cinquante et unième État des États-Unis. Jean Raspail se plaît à romancer ses explorations quasi-anthropologiques dans La Hache des Steppes (1974, réédition en 2016 chez Via Romana), dans Les Hussards (Robert Laffont, 1982) et dans Pêcheurs de Lune (Robert Laffont, 1990). Toujours en avance sur son époque, Jean Raspail a compris que l’État républicain tue la France et son peuple au nom de valeurs mondialistes. La République parasite la France, lui vole toute sa vitalité et contribue au changement graduel et insidieux de la population. Il n’a jamais caché son royalisme sans toutefois se lier à un prince particulier. Sa conception de la restauration royale, plus métaphysique que politique d’ailleurs, exprimée dans Sire (Éditions de Fallois, 1991) se rapproche du providentialisme si ce n’est du Grand Monarque attendu. Il témoigne aussi de sa fidélité aux rois de France. Pour commémorer les deux cents ans de l’exécution du roi Louis XVI, il organise, le 21 janvier 1993 sur la place de la Concorde, une manifestation à laquelle participe l’ambassadeur des États-Unis en personne.

Toujours en avance sur son époque, Jean Raspail a compris que l’État républicain tue la France et son peuple au nom de valeurs mondialistes. La République parasite la France, lui vole toute sa vitalité et contribue au changement graduel et insidieux de la population. Il n’a jamais caché son royalisme sans toutefois se lier à un prince particulier. Sa conception de la restauration royale, plus métaphysique que politique d’ailleurs, exprimée dans Sire (Éditions de Fallois, 1991) se rapproche du providentialisme si ce n’est du Grand Monarque attendu. Il témoigne aussi de sa fidélité aux rois de France. Pour commémorer les deux cents ans de l’exécution du roi Louis XVI, il organise, le 21 janvier 1993 sur la place de la Concorde, une manifestation à laquelle participe l’ambassadeur des États-Unis en personne. Son œuvre serait maintenant difficile à publier tant elle dérange. Elle propose une solution : l’existence d’isolats humains. Dans La Hache des Steppes, le narrateur s’échine à retrouver les lointains descendants des Huns dans le village d’Origny-le-Sec dans l’Aube. Il raconte plusieurs fois l’histoire de ces déserteurs sous Napoléon Ier qui se réfugient dans des villages russes reculés où ils font souche. Dans « Big Other », Jean Raspail annonce qu’« il subsistera ce que l’on appelle en ethnologie des isolats, de puissantes minorités, peut-être une vingtaine de millions de Français – et pas nécessairement de race blanche – qui parleront encore notre langue dans son intégrité à peu près sauvée et s’obstineront à rester conscients de notre culture et de notre histoire telles qu’elles nous ont été transmises de génération en génération (p. 37) ». L’exemple de certaines réserves peaux-rouges résilientes est à méditer…

Son œuvre serait maintenant difficile à publier tant elle dérange. Elle propose une solution : l’existence d’isolats humains. Dans La Hache des Steppes, le narrateur s’échine à retrouver les lointains descendants des Huns dans le village d’Origny-le-Sec dans l’Aube. Il raconte plusieurs fois l’histoire de ces déserteurs sous Napoléon Ier qui se réfugient dans des villages russes reculés où ils font souche. Dans « Big Other », Jean Raspail annonce qu’« il subsistera ce que l’on appelle en ethnologie des isolats, de puissantes minorités, peut-être une vingtaine de millions de Français – et pas nécessairement de race blanche – qui parleront encore notre langue dans son intégrité à peu près sauvée et s’obstineront à rester conscients de notre culture et de notre histoire telles qu’elles nous ont été transmises de génération en génération (p. 37) ». L’exemple de certaines réserves peaux-rouges résilientes est à méditer… À la notable différence d’un histrion de gauche (pléonasme !) et d’un éditorialiste sentencieux mauvais observateur patenté de l’actualité, Jean Raspail ne bénéficiera pas d’une couverture médiatique digne de son œuvre. Il n’aura pas droit à des obsèques dans la cour d’honneur des Invalides. Qu’importe si en hussard de la flotte australe, il passe à l’ère d’un monde froid, triste et si moderne pour une sentinelle postée en arrière-garde. Ses lecteurs savent pourtant que l’auteur du Roi au-delà de la mer (Albin Michel, 2000) appartient aux éclaireurs, à l’avant-garde d’une élite reconquérante, d’une élite qui applique la devise de cette famille hautement européenne de devoir, d’honneur et de courage, les Pikkendorff : « Je suis d’abord mes propres pas. » Jean Raspail l’a toujours fait sienne, du Cap Horn au Septentrion, de l’Ouest américain à L’île bleue (Robert Laffont, 1988).

À la notable différence d’un histrion de gauche (pléonasme !) et d’un éditorialiste sentencieux mauvais observateur patenté de l’actualité, Jean Raspail ne bénéficiera pas d’une couverture médiatique digne de son œuvre. Il n’aura pas droit à des obsèques dans la cour d’honneur des Invalides. Qu’importe si en hussard de la flotte australe, il passe à l’ère d’un monde froid, triste et si moderne pour une sentinelle postée en arrière-garde. Ses lecteurs savent pourtant que l’auteur du Roi au-delà de la mer (Albin Michel, 2000) appartient aux éclaireurs, à l’avant-garde d’une élite reconquérante, d’une élite qui applique la devise de cette famille hautement européenne de devoir, d’honneur et de courage, les Pikkendorff : « Je suis d’abord mes propres pas. » Jean Raspail l’a toujours fait sienne, du Cap Horn au Septentrion, de l’Ouest américain à L’île bleue (Robert Laffont, 1988).

Qui se souvient des Hommes ? était le titre de ce « roman » consacré aux Alakalufs. Ce livre aurait pu être présenté comme une « épopée » ou une « tragédie » humaine, recréant le destin de ces êtres, nos frères, que les hommes qui les virent hésitèrent à reconnaître comme des Hommes.

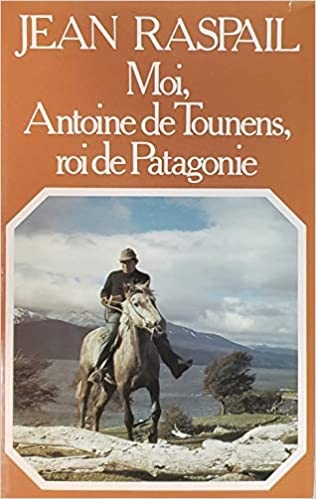

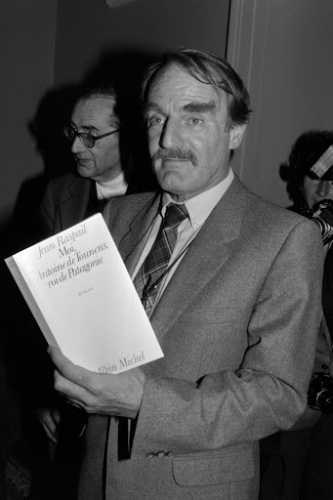

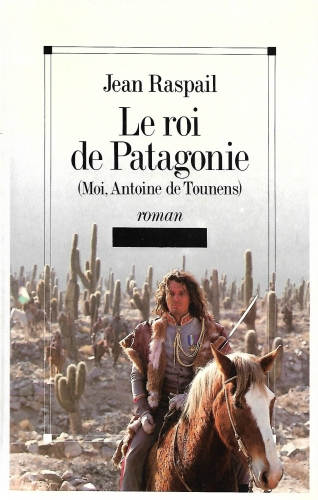

Qui se souvient des Hommes ? était le titre de ce « roman » consacré aux Alakalufs. Ce livre aurait pu être présenté comme une « épopée » ou une « tragédie » humaine, recréant le destin de ces êtres, nos frères, que les hommes qui les virent hésitèrent à reconnaître comme des Hommes. Déjà, en 1981, Jean Raspail avait publié Moi, Antoine de Tounens, roi de Patagonie ou le destin vécu d’un aventurier français qui débarqua en Argentine en 1860 et se fit proclamer roi d’Araucanie et de Patagonie par les populations indigènes locales. Ce livre avait obtenu le prix du roman de l’Académie française. Cet ouvrage relate l’histoire d’un aventurier venu du « Périgord vert » qui s’autoproclame roi, le 18 novembre 1860, par les tribus de cavaliers qui menaient contre l’Argentine et le Chili les derniers combats de la liberté et de l’identité. Il régna quelques mois, sous le nom d’Orllie-Antoine Ier (écrit parfois Orélie-Antoine Ier) galopant à leur tête en uniforme chamarré, sous les plis de son drapeau bleu, blanc, vert. Et puis, la chance l’abandonna. Trahi, jeté en prison, jugé, il parvint à regagner la France où un autre destin l’attendait, celui d’un roi de dérision en butte à tous les sarcasmes, mais jamais il ne céda. En effet, bien que le royaume n’existât plus, il créa autour de lui une petite cour, attribuant ainsi décorations et titres. Roi il resta, mais solitaire et abandonné, il mourut dans la misère le 17 septembre 1878, à Tourtoirac, en Dordogne, où il était né.

Déjà, en 1981, Jean Raspail avait publié Moi, Antoine de Tounens, roi de Patagonie ou le destin vécu d’un aventurier français qui débarqua en Argentine en 1860 et se fit proclamer roi d’Araucanie et de Patagonie par les populations indigènes locales. Ce livre avait obtenu le prix du roman de l’Académie française. Cet ouvrage relate l’histoire d’un aventurier venu du « Périgord vert » qui s’autoproclame roi, le 18 novembre 1860, par les tribus de cavaliers qui menaient contre l’Argentine et le Chili les derniers combats de la liberté et de l’identité. Il régna quelques mois, sous le nom d’Orllie-Antoine Ier (écrit parfois Orélie-Antoine Ier) galopant à leur tête en uniforme chamarré, sous les plis de son drapeau bleu, blanc, vert. Et puis, la chance l’abandonna. Trahi, jeté en prison, jugé, il parvint à regagner la France où un autre destin l’attendait, celui d’un roi de dérision en butte à tous les sarcasmes, mais jamais il ne céda. En effet, bien que le royaume n’existât plus, il créa autour de lui une petite cour, attribuant ainsi décorations et titres. Roi il resta, mais solitaire et abandonné, il mourut dans la misère le 17 septembre 1878, à Tourtoirac, en Dordogne, où il était né.

Ce goût, il l’avait pris dans sa jeunesse parisienne, quant il allait avec un petit camarade, certains après-midi, à la brasserie La Coupole, comme auditeur des réunions du club des explorateurs. Un vieux Monsieur ouvrait la séance avec la formule:

Ce goût, il l’avait pris dans sa jeunesse parisienne, quant il allait avec un petit camarade, certains après-midi, à la brasserie La Coupole, comme auditeur des réunions du club des explorateurs. Un vieux Monsieur ouvrait la séance avec la formule: Encore quelques livres de voyage, dont un grand : » les peaux-rouges aujourd’hui » en 1975. Puis c’est sa grande période de romancier, je suis un auteur tardif disait-il, pendant que ses chers peaux-rouges se révoltent à Wounded-knee, il sort ici « le jeu du roi », formidable ouvrage, tout Raspail est là, le livre s’ouvre sur une citation de Roger Caillois: « le rêve est un facteur de légitimité », les beaux livres s’enchaîneront ensuite , sept cavaliers (que j’ai adapté en BD) Moi Antoine de Tounens, où voit le jour la Patagonie littéraire, terre mythique refuge de ses lecteurs, dont il était le consul général. L’île bleu, adapté (mal) par Nadine Trintignant pour la télévision, livre directement issu de l’aventure à vélo dans la débâcle. Sire, Les Pikkendorff, famille fictive qui hante ses livres. Le plus beau pour moi : « Qui se souvient des hommes » prix du livre inter, il élève aux Alakaluffs de la terre de feu, anéantis depuis longtemps, un monument de papier. Un joli livre que je recommande pour sa partie explorateur : pêcheurs de lune. Un retour en Patagonie, avec le dernier voyage: « Adios Terra del fuego » il sait que l’âge est là, et qu’il n’y reviendra plus.

Encore quelques livres de voyage, dont un grand : » les peaux-rouges aujourd’hui » en 1975. Puis c’est sa grande période de romancier, je suis un auteur tardif disait-il, pendant que ses chers peaux-rouges se révoltent à Wounded-knee, il sort ici « le jeu du roi », formidable ouvrage, tout Raspail est là, le livre s’ouvre sur une citation de Roger Caillois: « le rêve est un facteur de légitimité », les beaux livres s’enchaîneront ensuite , sept cavaliers (que j’ai adapté en BD) Moi Antoine de Tounens, où voit le jour la Patagonie littéraire, terre mythique refuge de ses lecteurs, dont il était le consul général. L’île bleu, adapté (mal) par Nadine Trintignant pour la télévision, livre directement issu de l’aventure à vélo dans la débâcle. Sire, Les Pikkendorff, famille fictive qui hante ses livres. Le plus beau pour moi : « Qui se souvient des hommes » prix du livre inter, il élève aux Alakaluffs de la terre de feu, anéantis depuis longtemps, un monument de papier. Un joli livre que je recommande pour sa partie explorateur : pêcheurs de lune. Un retour en Patagonie, avec le dernier voyage: « Adios Terra del fuego » il sait que l’âge est là, et qu’il n’y reviendra plus.

Disons un mot de sa vie.

Disons un mot de sa vie. Raspail est un écologiste avant l’heure. Pour défendre les Royaumes « au-delà des mers », en 1981, alors que la France passe d’un socialisme larvé à un socialisme revendiqué, il se proclame Consul Général de Patagonie, ultime représentant du royaume d’Orélie-Antoine 1er.

Raspail est un écologiste avant l’heure. Pour défendre les Royaumes « au-delà des mers », en 1981, alors que la France passe d’un socialisme larvé à un socialisme revendiqué, il se proclame Consul Général de Patagonie, ultime représentant du royaume d’Orélie-Antoine 1er.

Cette faim,

Cette faim,

J’avais laissé la Patagonie. Je devais me rendre au nord, remontant le long fil de cuivre chilien. La route longiligne s’ornait de merveilleux observatoires, de brumes côtières, de déserts mystérieux jonchés des songes de voyageur. Je me sentais plus fort. Il y a comme cela des voyages qui vous révèlent ce que vous cherchez. Nous voulions le Tibet, et ce furent les Andes. Andes chrétiennes et hispaniques ou je dansai comme l’Inca la danse en l’honneur du ciel et de la vierge. J’arrivai à San Pedro d’Atacama, Mecque andine du tourisme local. Village en adobe, argile cuite sous le soleil, entouré de salars(2) de la peur, de déserts et de geysers. Une vieille église en bois de cactus, une longue messe guerrière où le bon prêtre dénonce la main noire qui contrôle son pays et qui, voilà trois ans, brûla sept statues pieuses.

J’avais laissé la Patagonie. Je devais me rendre au nord, remontant le long fil de cuivre chilien. La route longiligne s’ornait de merveilleux observatoires, de brumes côtières, de déserts mystérieux jonchés des songes de voyageur. Je me sentais plus fort. Il y a comme cela des voyages qui vous révèlent ce que vous cherchez. Nous voulions le Tibet, et ce furent les Andes. Andes chrétiennes et hispaniques ou je dansai comme l’Inca la danse en l’honneur du ciel et de la vierge. J’arrivai à San Pedro d’Atacama, Mecque andine du tourisme local. Village en adobe, argile cuite sous le soleil, entouré de salars(2) de la peur, de déserts et de geysers. Une vieille église en bois de cactus, une longue messe guerrière où le bon prêtre dénonce la main noire qui contrôle son pays et qui, voilà trois ans, brûla sept statues pieuses.

Il n’y aura pas, à l’enterrement de Jean Raspail, écrivain de marine, consul général du Royaume d’Araucanie et de Patagonie, de retransmission en direct, de larmes photogéniques, ni même d’hommage lyrique, écrit à la truelle pour un Président qui salit tout, même la grandeur. Ce qu’il y aura, outre les sujets fidèles et les soldats perdus, c’est le monde d’un romancier, romancier dont le travail est, disait son ami Volkoff, de faire « quelque chose de moins réel, mais de plus vrai ».

Il n’y aura pas, à l’enterrement de Jean Raspail, écrivain de marine, consul général du Royaume d’Araucanie et de Patagonie, de retransmission en direct, de larmes photogéniques, ni même d’hommage lyrique, écrit à la truelle pour un Président qui salit tout, même la grandeur. Ce qu’il y aura, outre les sujets fidèles et les soldats perdus, c’est le monde d’un romancier, romancier dont le travail est, disait son ami Volkoff, de faire « quelque chose de moins réel, mais de plus vrai ».

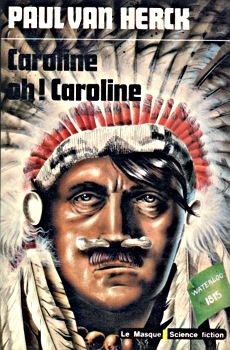

Outre sa couverture, Caroline Oh ! Caroline du Flamand Paul Van Herck (1938 – 1989) brave toutes les convenances historiques en proposant une satire déjantée proprement impubliable aujourd’hui. Inspiré à la fois par le style de Marcel Aymé et de la veine littéraire flamande souvent burlesque, Caroline Oh ! Caroline associe la farce, le fantastique, le psychadélisme et l’uchronie.

Outre sa couverture, Caroline Oh ! Caroline du Flamand Paul Van Herck (1938 – 1989) brave toutes les convenances historiques en proposant une satire déjantée proprement impubliable aujourd’hui. Inspiré à la fois par le style de Marcel Aymé et de la veine littéraire flamande souvent burlesque, Caroline Oh ! Caroline associe la farce, le fantastique, le psychadélisme et l’uchronie. Dans le cadre de sa mission secrète qui nécessite de traverser l’Atlantique par les airs grâce à l’un des tout premiers avions, on adjoint à Bill un second d’origine germanophone, prénommé Adolf, grand fan de Richard Wagner. C’est un « homme à la drôle de petite moustache et aux cheveux gris coiffés à la limande. Son regard était à la fois pénétrant et étrange (p. 46) ». Bien que regrettant la victoire franco-américaine de Waterloo, Adolf est prêt à explorer les « riches gisements au Tex-Ha, ou chez le Caliphe Hornia (p. 53) ».

Dans le cadre de sa mission secrète qui nécessite de traverser l’Atlantique par les airs grâce à l’un des tout premiers avions, on adjoint à Bill un second d’origine germanophone, prénommé Adolf, grand fan de Richard Wagner. C’est un « homme à la drôle de petite moustache et aux cheveux gris coiffés à la limande. Son regard était à la fois pénétrant et étrange (p. 46) ». Bien que regrettant la victoire franco-américaine de Waterloo, Adolf est prêt à explorer les « riches gisements au Tex-Ha, ou chez le Caliphe Hornia (p. 53) ». Dans ce monde rêvé par Houria Bouteldja, Rokhaya Diallo et Lilian Thuram, existent dorénavant « deux Europes, l’Europe Noire et l’Europe Rouge. Comme les Noirs venaient de l’ouest, et les Indiens de l’est, ce furent l’Europe occidentale et l’Europe orientale, sans aucune référence à la réalité géographique, car la ligne de démarcation avait de singulières sinuosités (p. 172) ». Les relations entre les deux ensembles victorieux se chargent de méfiance réciproque quand il n’est pas la proie d’attentats à répétition. L’un d’eux revient à Bill.

Dans ce monde rêvé par Houria Bouteldja, Rokhaya Diallo et Lilian Thuram, existent dorénavant « deux Europes, l’Europe Noire et l’Europe Rouge. Comme les Noirs venaient de l’ouest, et les Indiens de l’est, ce furent l’Europe occidentale et l’Europe orientale, sans aucune référence à la réalité géographique, car la ligne de démarcation avait de singulières sinuosités (p. 172) ». Les relations entre les deux ensembles victorieux se chargent de méfiance réciproque quand il n’est pas la proie d’attentats à répétition. L’un d’eux revient à Bill.

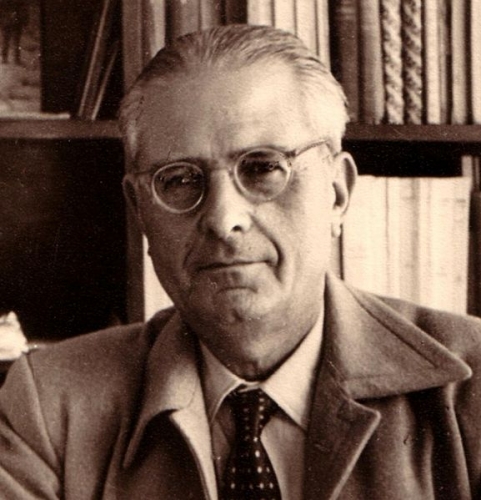

Toute œuvre romanesque qui ne se réduit pas à l’anecdote ou à de vaines complications psychologiques instaure un autre rapport au temps, s’inscrit dans une météorologie et une chronologie légendaires où l’homme cesse d’être à lui-même la seule réalité. Voici le ciel, la terre, et cette mémoire seconde, qui affleure, et qui porte les phrases ; voici cette rhétorique profonde, sur laquelle les phrases reposent comme sur une houle et vont porter jusqu’à nous, jusqu’aux rives de notre entendement, des mondes chiffrés, que notre intelligence déchiffre comme des énigmes, sans pour autant les expliquer. Ainsi les romans d’Henri Bosco nous laissent dans le suspens, dans une aporie, une attente, une attention extrêmes aux variations d’ombre et de lumière, aux états d’âme qui n’appartiennent pas seulement aux sentiments humains mais au monde lui-même, à ce Pays qui n’est pas seulement une réalité administrative ou départementale mais un don, une civilité, un commerce entre le visible et l’invisible, - le don d’une autre temporalité qui nous fait à jamais insolvables des bienfaits reçus.

Toute œuvre romanesque qui ne se réduit pas à l’anecdote ou à de vaines complications psychologiques instaure un autre rapport au temps, s’inscrit dans une météorologie et une chronologie légendaires où l’homme cesse d’être à lui-même la seule réalité. Voici le ciel, la terre, et cette mémoire seconde, qui affleure, et qui porte les phrases ; voici cette rhétorique profonde, sur laquelle les phrases reposent comme sur une houle et vont porter jusqu’à nous, jusqu’aux rives de notre entendement, des mondes chiffrés, que notre intelligence déchiffre comme des énigmes, sans pour autant les expliquer. Ainsi les romans d’Henri Bosco nous laissent dans le suspens, dans une aporie, une attente, une attention extrêmes aux variations d’ombre et de lumière, aux états d’âme qui n’appartiennent pas seulement aux sentiments humains mais au monde lui-même, à ce Pays qui n’est pas seulement une réalité administrative ou départementale mais un don, une civilité, un commerce entre le visible et l’invisible, - le don d’une autre temporalité qui nous fait à jamais insolvables des bienfaits reçus.  L’œuvre d’Henri Bosco est, comme toutes les grandes œuvres de notre littérature, une pensée en action, mais en accord avec l’étymologie même du mot pensée, qui évoque la juste pesée, ces rapports et ces proportions où la part de l’inconnu n’est pas moins grande que la part connue ; où la part de la nuit détient les secrets de la lumière provençale. Œuvre nocturne mais non point ténébreuse ou opaque, louange des nuits lumineuses, des ombres qui sauvegardent, du haut jour qui tient sa vérité comme le secret d’une plus haute clarté encore, l’œuvre d’Henri Bosco sauve les phénomènes de la représentation abstraite que nous nous en faisons, et nous sauve nous-mêmes de nos identités trop certaines qui nous enferment dans une humanité irreliée à l’ordre du monde, détachée de la sagesse profonde de la nuit foisonnante de toutes les choses vivantes qui tendent vers la lumière ou en reçoivent les éclats. « Je pus ainsi, écrit Henri Bosco, me replacer sans peine devant le décor intérieur où j’avais regardé ma propre nuit en train de descendre sur moi cependant qu’au-dessus de moi dans le ciel s’avançait la nuit sidérale ».

L’œuvre d’Henri Bosco est, comme toutes les grandes œuvres de notre littérature, une pensée en action, mais en accord avec l’étymologie même du mot pensée, qui évoque la juste pesée, ces rapports et ces proportions où la part de l’inconnu n’est pas moins grande que la part connue ; où la part de la nuit détient les secrets de la lumière provençale. Œuvre nocturne mais non point ténébreuse ou opaque, louange des nuits lumineuses, des ombres qui sauvegardent, du haut jour qui tient sa vérité comme le secret d’une plus haute clarté encore, l’œuvre d’Henri Bosco sauve les phénomènes de la représentation abstraite que nous nous en faisons, et nous sauve nous-mêmes de nos identités trop certaines qui nous enferment dans une humanité irreliée à l’ordre du monde, détachée de la sagesse profonde de la nuit foisonnante de toutes les choses vivantes qui tendent vers la lumière ou en reçoivent les éclats. « Je pus ainsi, écrit Henri Bosco, me replacer sans peine devant le décor intérieur où j’avais regardé ma propre nuit en train de descendre sur moi cependant qu’au-dessus de moi dans le ciel s’avançait la nuit sidérale ». Rien de muséologique dans ce Pays qui est une réalité antérieure autant qu’un « vœu de l’esprit », selon la formule de René Char. Rien qui soit de l’ordre d’une représentation, d’une identité recluse sur elle-même, mais la pure et simple présence réelle qui ne s’éprouve que par la brusque flambée portée dans la rumeur du vent et dans l’amitié qui nous unit au monde, dans ces affinités dont nous sommes les élus bien plus que nous ne les choisissons. Ce qui nous est conté est un recours au cours de la tradition, de sa solennité légère, et non plus un discours ; une conversation et non pas une discussion, si bien que l’intelligence se laisse empreindre par les lieux qu’elle fréquente dans le temps infiniment recommencé de la promenade. C’est dans la connivence des éléments, de l’air, de l’eau, du feu et de la terre, en leurs inépuisables métamorphoses, que le temps se renouvelle et s’enchante au lieu de n’être que le signe de l’usure, d’une finalité malapprise, insultante au regard du libre cours qui conduit à elle.

Rien de muséologique dans ce Pays qui est une réalité antérieure autant qu’un « vœu de l’esprit », selon la formule de René Char. Rien qui soit de l’ordre d’une représentation, d’une identité recluse sur elle-même, mais la pure et simple présence réelle qui ne s’éprouve que par la brusque flambée portée dans la rumeur du vent et dans l’amitié qui nous unit au monde, dans ces affinités dont nous sommes les élus bien plus que nous ne les choisissons. Ce qui nous est conté est un recours au cours de la tradition, de sa solennité légère, et non plus un discours ; une conversation et non pas une discussion, si bien que l’intelligence se laisse empreindre par les lieux qu’elle fréquente dans le temps infiniment recommencé de la promenade. C’est dans la connivence des éléments, de l’air, de l’eau, du feu et de la terre, en leurs inépuisables métamorphoses, que le temps se renouvelle et s’enchante au lieu de n’être que le signe de l’usure, d’une finalité malapprise, insultante au regard du libre cours qui conduit à elle.

Le temps qualifié, la géographie sacrée, les ressources secrètes des êtres et des choses singuliers, qui vont s’accordant avec les forces impersonnelles, ouvrent un espace, celui du roman, où le monde intérieur et le monde extérieur cessent d’être séparés par d’irréfragables frontières. Le soleil, le fleuve, les arbres, le vent, la nuit sont des présences sacrées car leur réalité symbolise avec une réalité plus haute, hors d’atteinte, que les phrases mélodieuses, selon la formule héraclitéenne, « voilent et dévoilent en même temps ». Entre le sensible et l’intelligible, entre la nuit profonde et l’éblouissante clarté, toutes les gradations s’emparent des songes, des effrois, des attentes ardentes des personnages devenus, par le génie romanesque, fabuleux instruments de perception des variations météorologiques. La vérité humaine est d’autant plus profonde et nuancée qu’elle est située, qu’elle cesse, par un suspens, de se référer exclusivement à elle-même. Les hommes ne sont humblement et souverainement présents que par ce partage de leur règne qu’ils consentent avec la terre et le ciel.

Le temps qualifié, la géographie sacrée, les ressources secrètes des êtres et des choses singuliers, qui vont s’accordant avec les forces impersonnelles, ouvrent un espace, celui du roman, où le monde intérieur et le monde extérieur cessent d’être séparés par d’irréfragables frontières. Le soleil, le fleuve, les arbres, le vent, la nuit sont des présences sacrées car leur réalité symbolise avec une réalité plus haute, hors d’atteinte, que les phrases mélodieuses, selon la formule héraclitéenne, « voilent et dévoilent en même temps ». Entre le sensible et l’intelligible, entre la nuit profonde et l’éblouissante clarté, toutes les gradations s’emparent des songes, des effrois, des attentes ardentes des personnages devenus, par le génie romanesque, fabuleux instruments de perception des variations météorologiques. La vérité humaine est d’autant plus profonde et nuancée qu’elle est située, qu’elle cesse, par un suspens, de se référer exclusivement à elle-même. Les hommes ne sont humblement et souverainement présents que par ce partage de leur règne qu’ils consentent avec la terre et le ciel.  Contre la clarté monocorde, ennemie des ombres, Henri Bosco invoque non seulement le frémissement de l’eau, mais aussi le feu, là même où s’opère la coalescence de l’Eros et du Logos : « J’étais fasciné par le feu. Il pénétrait en moi, immobilisait mon cerveau sur une seule idée. Cette idée n’était qu’une braise… Terrible, mais si vive, si envahissante qu’elle ne soulevait aucune épouvante. J’étais devenu feu, corps de feu, cœur de feu, esprit-feu, et toute la forêt en flammes. Si l’incendie se fut propagé jusqu’à moi, je n’aurais pas fui, j’aurai attendu, embrassé le feu, et pris feu pour disparaître dans mon propre feu au milieu d’une gerbe d’étincelles. »

Contre la clarté monocorde, ennemie des ombres, Henri Bosco invoque non seulement le frémissement de l’eau, mais aussi le feu, là même où s’opère la coalescence de l’Eros et du Logos : « J’étais fasciné par le feu. Il pénétrait en moi, immobilisait mon cerveau sur une seule idée. Cette idée n’était qu’une braise… Terrible, mais si vive, si envahissante qu’elle ne soulevait aucune épouvante. J’étais devenu feu, corps de feu, cœur de feu, esprit-feu, et toute la forêt en flammes. Si l’incendie se fut propagé jusqu’à moi, je n’aurais pas fui, j’aurai attendu, embrassé le feu, et pris feu pour disparaître dans mon propre feu au milieu d’une gerbe d’étincelles. » Tel est peut-être un des secrets le mieux gardés de la littérature française, de sa tant et si mal vantée « clarté classique », de n’être, en sa beauté ordonnatrice, qu’un surgeon d’intuitions plus profondes et plus sauvages, où l’art du sourcier, l’oniromancie, viennent irriguer la plénitude des formes du jour. Ce qui distingue l’art romanesque d’Henri Bosco, son poiein, sa pensée en action, n’est peut-être rien d’autre le sens des contiguïtés, et l’on pourrait presque dire de la consanguinité, du monde du rêve et du monde de la réalité. Ce qui unit les personnages et leurs ombres, qui parfois semblent leur échapper, n’est pas de l’ordre de la nécessité ou du déterminisme, disposé en discours, mais bien de celui d’une recouvrance. Si , comme dans l’œuvre de Gérard de Nerval, le songe et la réalité en sont pas séparés ce n’est point par artifice littéraire, mais parce que dans la vision et la pensée d’Henri Bosco, ils ne se distinguent qu’en se graduant. Le rêve est la réalité d’un autre rêve, et notre songe humain des songes du Pays reçoit ses messages. Nous ne commençons à habiter véritablement les lieux, c’est-à-dire que nous n’en devenons les hôtes que si hôtes à notre tour, nous recevons les légendes qui sont dans l’arbre des mots, comme l’envers argenté des feuilles.

Tel est peut-être un des secrets le mieux gardés de la littérature française, de sa tant et si mal vantée « clarté classique », de n’être, en sa beauté ordonnatrice, qu’un surgeon d’intuitions plus profondes et plus sauvages, où l’art du sourcier, l’oniromancie, viennent irriguer la plénitude des formes du jour. Ce qui distingue l’art romanesque d’Henri Bosco, son poiein, sa pensée en action, n’est peut-être rien d’autre le sens des contiguïtés, et l’on pourrait presque dire de la consanguinité, du monde du rêve et du monde de la réalité. Ce qui unit les personnages et leurs ombres, qui parfois semblent leur échapper, n’est pas de l’ordre de la nécessité ou du déterminisme, disposé en discours, mais bien de celui d’une recouvrance. Si , comme dans l’œuvre de Gérard de Nerval, le songe et la réalité en sont pas séparés ce n’est point par artifice littéraire, mais parce que dans la vision et la pensée d’Henri Bosco, ils ne se distinguent qu’en se graduant. Le rêve est la réalité d’un autre rêve, et notre songe humain des songes du Pays reçoit ses messages. Nous ne commençons à habiter véritablement les lieux, c’est-à-dire que nous n’en devenons les hôtes que si hôtes à notre tour, nous recevons les légendes qui sont dans l’arbre des mots, comme l’envers argenté des feuilles.

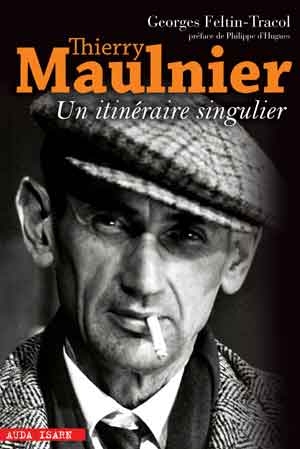

Thierry Maulnier, nom de plume de Jacques Louis André Talagrand (1909 – 1988), a rédigé de nombreux essais, écrit plusieurs pièces de théâtre et donné bien des préfaces. Sa bibliographie comporte cependant une omission de taille : l’absence de Révolution Nationale. L’avenir de la France. Cet ouvrage s’apparente à une sorte de fantôme dont diverses personnes ont nié son existence réelle.