Les Francs, les Saxons et les Scandinaves sont venus s'installer sur nos cotes et dans l'intérieur de nos terres, on pense généralement qu'ils oublièrent très rapidement leurs anciennes traditions. Il s'agit là de conceptions simplistes ; les Traditions ne sont pas une mode que l'on change au gré du temps et des vents. Nos Traditions sont éternelles ; elles sont au plus profond de nous même. Nos Ancêtres les ont exprimées suivant leurs instincts et leurs aspirations profondes. Elles nous conviennent parce que liées à notre tempérament. Si elles sont momentanément étouffées, elles sont latentes en nous et ressurgiront car notre Etre est éternel et ne peut être modifié dans son essence profonde. Le Peuple les a maintenues avec obstination alors que leur sens était oublié, mais leur maintien était un besoin impératif ; quelquefois elles se manifestent inconsciemment. Nos Traditions sont nos façons de concevoir le monde et de vivre en harmonie avec lui.

Les Francs, les Saxons et les Scandinaves sont venus s'installer sur nos cotes et dans l'intérieur de nos terres, on pense généralement qu'ils oublièrent très rapidement leurs anciennes traditions. Il s'agit là de conceptions simplistes ; les Traditions ne sont pas une mode que l'on change au gré du temps et des vents. Nos Traditions sont éternelles ; elles sont au plus profond de nous même. Nos Ancêtres les ont exprimées suivant leurs instincts et leurs aspirations profondes. Elles nous conviennent parce que liées à notre tempérament. Si elles sont momentanément étouffées, elles sont latentes en nous et ressurgiront car notre Etre est éternel et ne peut être modifié dans son essence profonde. Le Peuple les a maintenues avec obstination alors que leur sens était oublié, mais leur maintien était un besoin impératif ; quelquefois elles se manifestent inconsciemment. Nos Traditions sont nos façons de concevoir le monde et de vivre en harmonie avec lui.

Ainsi, les Vikings ne purent être aussi facilement « assimilés » qu'on le dit - l'assimilation totale est impossible car il y a toujours des caractères irréductibles incompressibles, ce qu'on appelle le « tempérament normand ».

Arrivés dans une population en fait peu différente, puisque sur le vieux fond originel étaient venus se greffer les Celtes, puis les Saxons et les Francs, de même origine et Civilisation que les Scandinaves, nos Vikings défendirent leurs traditions. Rioulf se souleva avec les Normands de l'Ouest contre la dynastie ducale et fut défait avec ses troupes au Pré-de-la-Bataille en 935 après avoir fait le siège de Rouen, un siècle plus tard Guillaume écrasait les Cotentinais et Bayeusins révoltés. Ils transmirent bien autre chose à leurs descendants qu'un « tempérament » et une pigmentation à dominante « claire ».

Ils marquèrent de leur empreinte les noms de champs, le vocabulaire agricole et maritime et, surtout, ils transmirent à leurs descendants une partie de leur mythologie et de leurs croyances religieuses. Pour qui sait chercher on peut trouver dans nos traditions normandes des traces de l'ancienne religion nordique ; à notre connaissance cette question n'a encore jamais été étudiée d'une manière sérieuse et approfondie. Jusqu'à présent quelques rares publications ont examinées les faits folkloriques en tâchant de leur donner un certain nombre d'explications. Nous procéderons d'une manière plus logique - en étudiant l'origine de nos Traditions, puis en examinant leurs survivances.

Parmi les traditions normandes, en feuilletant les recueils de contes et légendes, nous découvrons des histoires de Varous. Ce nom d'origine germanique désigne un « homme-loup » et correspond exactement au danois moderne varulv, werwolf en allemand, (wair/wer : homme, wolf/ulf/ulv : loup). Il s'agit donc là d'une tradition Scandinave qui a traversé les siècles.

Les antiques confréries...

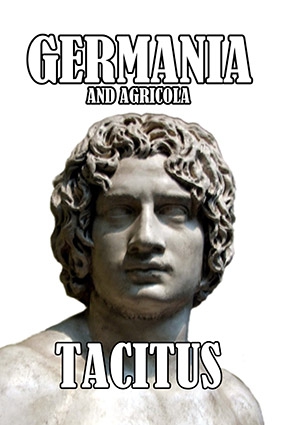

Dans la Germanie (C XLIV), l'historien latin Tacite nous donne la plus ancienne mention d'une confrérie guerrière, celle des Harii (dont le nom signifie probablement les « guerriers ») : « Quant aux Haries, leur âme farouche enchérit encore sur leur sauvage nature en empruntant les secours de l'art et du moment: boucliers noirs, corps peints ; pour combattre, ils choisissent des nuits noires ; l'horreur seule et l'ombre qui accompagnent cette année de lémures suffisent à porter l'épouvante, aucun ennemi ne soutenant cette vue étonnante et comme infernale, car en toute bataille les premiers vaincus sont les yeux ».

Dans la Germanie (C XLIV), l'historien latin Tacite nous donne la plus ancienne mention d'une confrérie guerrière, celle des Harii (dont le nom signifie probablement les « guerriers ») : « Quant aux Haries, leur âme farouche enchérit encore sur leur sauvage nature en empruntant les secours de l'art et du moment: boucliers noirs, corps peints ; pour combattre, ils choisissent des nuits noires ; l'horreur seule et l'ombre qui accompagnent cette année de lémures suffisent à porter l'épouvante, aucun ennemi ne soutenant cette vue étonnante et comme infernale, car en toute bataille les premiers vaincus sont les yeux ».

Dans un autre passage, Tacite présente des traditions analogues adoptées par tout un peuple, celui des Haltes (les ancêtres des hessois actuels) - « dès qu'ils sont parvenus à l'âge d'homme, ils laissent pousser cheveux et barbe et c'est seulement après avoir tué un ennemi qu'ils déposent un aspect pris par vœu et consacré à la vertu. Sur leurs sanglants trophées ils se découvrent le front, alors ils croient avoir enfin payé le prix de leur naissance, être dignes de leur patrie et de leurs parents ; les lâches et les poltrons restent dans leur salelé. Les plus braves portent en outre un anneau de fer, ce qui est ignominieux chez cette nation, en guise de chaîne, jusqu'à ce qu'ils se rachètent par la mort d'un ennemi (C. XXXI)».

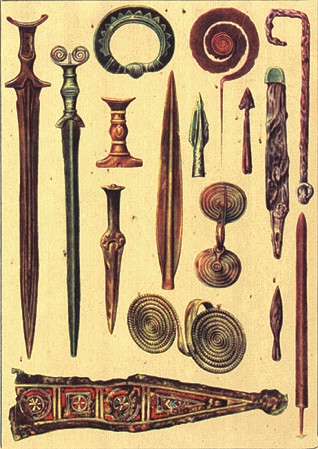

L'archéologie nous apporte aussi sa contribution, sur des plaques de bronze du 7e siècle de notre ère provenant de l'île d'Oland (Suède), nous voyons quelques scènes qui doivent se rattacher à des danses rituelles. Sur ces quatre plaques nous apercevons :

- un personnage tenant en laisse un animal ou un monstre,

- un guerrier entre deux ours ;

- deux guerriers porteurs d'une lance et coiffés d'un casque à cimier en forme de sanglier.

- un personnage, porteur de deux lances et coiffé d'un curieux casque, qui exécute une sorte de danse, à côté de lui, un guerrier est revêtu d'une peau de loup - il s'agit probablement d'une danse rituelle.

On pense que le casque, dont proviennent ces plaques, devait appartenir à un membre d'une confrérie cultuelle. Sur le casque de Sutton-Hoo (Cf. Heimdal N° 7, p. 8) nous trouvons des guerriers, analogues à celui de la quatrième plaque, qui exécutent une danse.

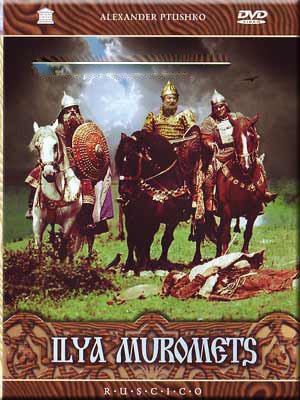

Plus tard, à l'époque des Vikings, nous apprenons que les Chefs Scandinaves aiment s'entourer d'une garde formée de guerriers d'élite, les Bersekir. Comme leur nom l'indique, ces guerriers sont vêtus d'une peau d'ours. Ils sont insensibles aux armes et au feu, dans le combat ils sont pris de « fureur » et ne craignent aucun danger ; ils en ressortent complètement épuisés. A la même époque nous trouvons un autre type de guerriers qui eux s'identifient à des loups. Les Ulfhedhnar. Tacite notait déjà que les princes s'entouraient de suites de jeunes guerriers et les Sagas nous racontent les aventures des Vikings de Jomsburg qui formaient une sorte de confrérie.

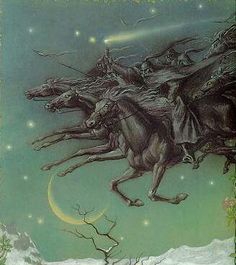

La mythologie nous apprend que les guerriers morts étaient dédiés à Odin. Les Valkyries venaient les chercher sur le champ de bataille pour les emmener au Valhal. Pour se préparer au Ragnarök, le « crépuscule des dieux », ils passaient la journée à se battre, le soir les morts ressuscitaient. Ces Einherjar formaient l'armée d'Odin, l'armée des morts

La philologie nous apportera un dernier élément ; le terme hansa n'a pas à l'origine un sens commercial, il signifie «suite, cohorte, troupe». Sur une pierre runique de Bjälbo nous trouvons le terme kiltar, une guilde de Frisons, mais dans les anciens glossaires du vieil-haut-allemand, gelt est synonyme de bluostar (« sacrifice »). Ainsi, à l'origine, les hanses et guildes sont des confréries cultuelles qui exécutent des sacrifices rituels.

... au rituel initiatique

Les travaux des spécialistes de la religion nordique, ceux du grand savant néerlandais Jan de Vries, ont permis de mettre en évidence l'importance des confréries cultuelles chez les anciens peuples du Nord.

A première vue on serait tenté de les répartir en deux catégories - les confréries guerrières et les confréries cultuelles En fait, cela serait peu fondé car à cette époque tout homme libre est un guerrier, d'autre part le sacré est présent dans toute action guerrière. Avant la bataille, pour dédier les ennemis à Odin, on envoie une lance (son attribut) au dessus d'eux. La coutume des Haries a plus un sens religieux que celui d'une ruse de guerre ; ils s'identifient magiquement à l'armée des esprits, la « Chasse sauvage ».

Quels sont les rites de ces confréries ? Nous avons peu de documents sur cette question : il s'agit de rites occultes (donc secrets), christianisés ou poursuivis quand ils ne pouvaient être assimilés, bien des éléments ont disparu. Toutefois. Jan de Vries (Altg. Rel., T. 1, pp 454 et 499) a pu établir qu'il existait une coutume initiatique. L'admission dans une confrérie est considérée comme l'entrée dans la communauté des esprits des Ancêtres. « Le postulant est coupé du monde auquel il appartenait et pour pénétrer dans le monde des ancêtres il connaît la mort symbolique puis la renaissance qui est liée à l'attribution d'un nouveau nom. Les mystères de la Tribu lui sont alors dévoilés ; on lui montre les objets sacrés, on lui apprend les rites et on l'informe de l'Histoire mythique de la Nation, des dieux et de la création du monde, des règles de morale et des tabous. Enfin des rites particuliers doivent le réintroduire dans le monde profane » (op. cit. p. 499). Ainsi, nous remarquons le rôle prééminent donné au culte des Ancêtres au sein de ces confréries, la communauté des morts et des vivants forme un tout (Cf. notre article sur le clan dans le N° 7 de Heimdal), cette communauté a sa source dans un mythe originel.

Des défilés rituels...

Quant aux manifestations de ces rituels, les membres des confréries défilent recouverts de peaux de bêtes - peaux de loup (animal d'Odin), d'ours, de cerf... - ou même de feuillage. Ils s'identifient à l'armée des morts mais aussi à des animaux ou à des éléments naturels car le culte des morts est lié au culte de la nature et de la fécondité - il s'agit de penser à la mort et à la renaissance de la nature qui trouve son parallèle dans la mort des Ancêtres et leur réincarnation dans un de leurs descendants.

Quant aux manifestations de ces rituels, les membres des confréries défilent recouverts de peaux de bêtes - peaux de loup (animal d'Odin), d'ours, de cerf... - ou même de feuillage. Ils s'identifient à l'armée des morts mais aussi à des animaux ou à des éléments naturels car le culte des morts est lié au culte de la nature et de la fécondité - il s'agit de penser à la mort et à la renaissance de la nature qui trouve son parallèle dans la mort des Ancêtres et leur réincarnation dans un de leurs descendants.

S'identifiant aux morts et aux animaux dont ils portent la dépouille, ils parcourent le pays en exécutant des danses rituelles au caractère magique et sont transportés par une « fureur sacrée ». Dans la Saga d'Egill on parle de Kveldulfr (« loup du soir ») qui, d'après Gamillscheg, serait à l'origine de l'expression française « courir le guilledou »

... au Carnaval

Ces processions avaient lieu pendant les douze jours de chaos qui se situent entre le Jul (Noël) et la nouvelle année, le Carnaval avec ses corporations, ses personnages étranges, son « déchaînement » en est une manifestation maintenue à travers les siècles mais vidée d'une partie de son sens. En Norvège, pendant la période du Jul, des groupes, grimés en animaux, traversent les villages. Le carnaval vit encore dans une bonne partie de l'Europe du Nord - défilé du Jol, défilé de Perchta, Fastnacht...

Mais on trouve d'autres survivances. La Hanse, les guildes et corporations médiévales sont les héritières des confréries de l'ancien Nord. Jusqu'à une époque récente, les corporations d'étudiants, avec leur « bizutage », leurs « beuveries rituelles » et leurs défilés colorés n'étaient pas sans rappeler cette tradition. On pense même que les danses rituelles christianisées seraient à l'origine des mystères médiévaux.

En Normandie, les varous

Mais ces croyances ont bien souvent été rejetées et qualifiées de « démoniaques » après l'implantation du christianisme.

Tel est le cas des Varous, tradition bien attestée en Normandie. Le Varou « Tous les soirs, au coucher du soleil il revêt une peau de loup, de chèvre ou de mouton. Cette peau s'appelle une hure. Le diable, auquel ce malheureux est échu en partage, le traite fort durement ; les coups de bâton trottent, les croquignoles et les nasardes ne sont point épargnées ; les gourmades et les horions pleuvent à foison : le pauvre patient souffre cruellement. C'est ce qui arrive surtout, si à l'heure que Satan lui a fixée, le possédé ne se trouve pas exactement au rendez-vous qui est ordinairement le pied d'un if; le malin va et pour le bon exemple, au centre de chaque carrefour, et devant toutes les croix du voisinage ». (Du Bois, Recherches.-, sur la Normandie, p 299).

Dans les anciennes lois normandes (Leges régis Henrici primi), pour le châtiment de certains crimes, il est dit que le coupable soit traité comme loup) («Wargus habeatur »).

Jusqu'au 18e siècle, des prêtres, se faisant l'auxiliaire de la justice, tenaient des monitoires, cérémonies au cours desquelles ils adjuraient les témoins de certains crimes de se faire connaître ; ceux qui n'obéissaient pas « aux injonctions d'un monitoire étaient excommuniés, changés en loup et forcés de courir la nuit dans les campagnes pendant un certain nombre d'années» (J. Lecceur, Esquisses du Bocage Normand, II, p. 403). Ils devenaient varous.

Le thème du Varou a donné naissance à de nombreuses histoires et légendes, entre autres celle du Varou de Gréville recueilli par J. Fleury et celle de la jeune fille Varou de Clécy présentée par Jules Lecoeur (Ces deux textes sont rassemblés dans l'ouvrage de Marthe Moricet).

Mais ce qui nous semble encore plus intéressant c'est l'étude des « périodes d'activité » des Varous. Ils courent la nuit comme les Harii ou la « Chasse Sauvage » et particulièrement autour de la période de Noël, pendant l'Avent du côté de Pont-Audemer, de Noël à la Chandeleur dans la Manche. Il est un dicton du Bessin qui dit : « A la Chandeleur, toutes bêtes sont en horreur ». M. Moricet s'en étonne, en fait cela correspond à la période de chaos des douze nuits pendant laquelle Odin faisait chevaucher l'armée des morts. Tout est clair.

Mais ce qui nous semble encore plus intéressant c'est l'étude des « périodes d'activité » des Varous. Ils courent la nuit comme les Harii ou la « Chasse Sauvage » et particulièrement autour de la période de Noël, pendant l'Avent du côté de Pont-Audemer, de Noël à la Chandeleur dans la Manche. Il est un dicton du Bessin qui dit : « A la Chandeleur, toutes bêtes sont en horreur ». M. Moricet s'en étonne, en fait cela correspond à la période de chaos des douze nuits pendant laquelle Odin faisait chevaucher l'armée des morts. Tout est clair.

Nous pouvons aussi supposer qu'une partie de ces traditions n'a pas été rejetée dans la « démonologie ». Les Confréries de Charitons, typiquement normandes, sont apparues dès l'époque ducale alors que les traditions nordiques étaient encore relativement vivaces, ce sont des confréries à caractère religieux et qui sont chargés du « culte des morts », donc sur le plan chrétien l'exact correspondant des confréries initiatiques cultuelles originelles. On peut même envisager une étape intermédiaire, il y a à Jumièges une antique confrérie qui élit son Grand Maître lors du feu de la Saint-Jean, le Confrérie du Loup Vert, nous en reparlerons... Dans notre prochain numéro, pour la période du Jul, nous étudierons le mythe normand de la Mesnie Hellequin, nous suivrons Odin et sa chasse sauvage.

Georges BERNAGE.

BIBLIOGRAPHIE :

Louis de BEACKER, de la Religion du Nord de la France avant le christianisme, p. 189 à 193 (le Weerwolven flamand).

Amélie BOSQUET, La Normandie Romantique et Merveilleuse -

rééd. Le Portulan, Brionne, 1971. p. 223 à 243.

Marthe MORICET, Récits et Contes des Veillées Normandes, Caen, 1963. p. 65 à 75.

Jan de VRIES, Altgermanische Religionsgeschichte, p. 488 à 505. Roy CHRISTIAN, Old English Customs, 1972. p. 21 à 26.

Source : HEIMDAL (Normandie-Europe du nord) N° 13 – Automne 1974

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

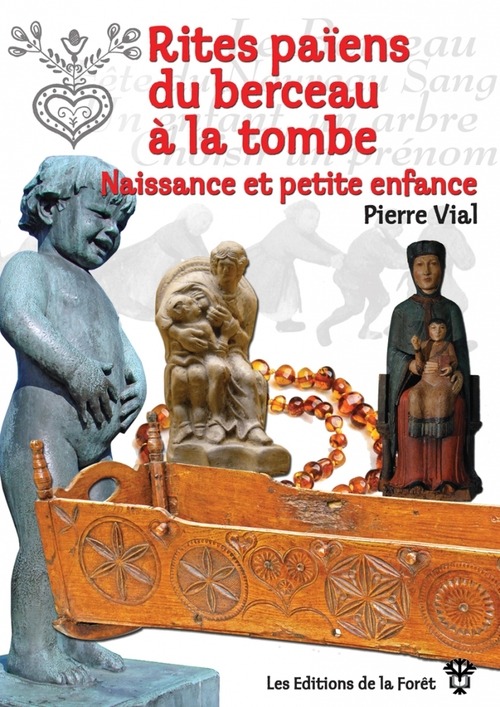

Cette industrie artistique a aidé à comprendre (même si elle a parfois caricaturé ou recyclé) la beauté du monde ancien, tellurique et agricole qui allait disparaître. Le cinéma japonais est magnifique dans ce sens jusqu’au début des années soixante. Et donc l’objet de ce livre est de pousser la jeunesse à redécouvrir l’esprit de la Genèse, la nature, les animaux, les cycles, les hauts faits, les voyages et les grandes aventures initiatiques. Les romains, dit déjà Juvénal dans ses Satires, connurent le même problème, les enfants ne croyant même plus aux enfers ! C’est un livre sur la poésie de la vie et des images qui nous aident à l’affronter aux temps de l’existence zombie et postmoderne.

Cette industrie artistique a aidé à comprendre (même si elle a parfois caricaturé ou recyclé) la beauté du monde ancien, tellurique et agricole qui allait disparaître. Le cinéma japonais est magnifique dans ce sens jusqu’au début des années soixante. Et donc l’objet de ce livre est de pousser la jeunesse à redécouvrir l’esprit de la Genèse, la nature, les animaux, les cycles, les hauts faits, les voyages et les grandes aventures initiatiques. Les romains, dit déjà Juvénal dans ses Satires, connurent le même problème, les enfants ne croyant même plus aux enfers ! C’est un livre sur la poésie de la vie et des images qui nous aident à l’affronter aux temps de l’existence zombie et postmoderne. Qu’il est dur d’être païen ! Ou plus exactement « néo-païen ». Qu’est-ce que cela peut bien dire d’ailleurs « néo-païen » ? Peut-on être culturellement et/ou cultuellement « néo-païen » ? Et surtout à quoi cela peut-il « servir » d’être ou de se proclamer du paganisme en général ?

Qu’il est dur d’être païen ! Ou plus exactement « néo-païen ». Qu’est-ce que cela peut bien dire d’ailleurs « néo-païen » ? Peut-on être culturellement et/ou cultuellement « néo-païen » ? Et surtout à quoi cela peut-il « servir » d’être ou de se proclamer du paganisme en général ? Dans cet essai paru en 2002 dans le premier volume de la revue TYR : Myth – Culture – Tradition, Collin Cleary expose la théorie de base de ce qui deviendra son système de pensée. En premier lieu, une mise au point salutaire quant au concept de « l’ouverture aux dieux » s’impose. En effet cette dernière est le plus souvent biaisée, faisant même office de simulacre car envisagée uniquement d’un point de vue moderne, c’est-à-dire, dans ce cas précis, rationaliste, alors que « l’ouverture au divin est rendue possible par un point de vue plus fondamental : l’ouverture à l’être des choses elles-mêmes », soit un parti pris heideggerien . La compréhension du divin passe donc belle et bien par une ouverture, mais une ouverture au sensible, véritablement naturelle pour les hommes, et non pas par une ouverture rationnelle. On comprend ainsi que c’est notre fermeture qui n’est pas naturelle. Le premier pas vers une réouverture consiste en un « changement radical dans notre manière de nous orienter vis-à-vis des êtres, et ceci doit commencer par une critique radicale et impitoyable de tous les aspects de notre monde moderne. »

Dans cet essai paru en 2002 dans le premier volume de la revue TYR : Myth – Culture – Tradition, Collin Cleary expose la théorie de base de ce qui deviendra son système de pensée. En premier lieu, une mise au point salutaire quant au concept de « l’ouverture aux dieux » s’impose. En effet cette dernière est le plus souvent biaisée, faisant même office de simulacre car envisagée uniquement d’un point de vue moderne, c’est-à-dire, dans ce cas précis, rationaliste, alors que « l’ouverture au divin est rendue possible par un point de vue plus fondamental : l’ouverture à l’être des choses elles-mêmes », soit un parti pris heideggerien . La compréhension du divin passe donc belle et bien par une ouverture, mais une ouverture au sensible, véritablement naturelle pour les hommes, et non pas par une ouverture rationnelle. On comprend ainsi que c’est notre fermeture qui n’est pas naturelle. Le premier pas vers une réouverture consiste en un « changement radical dans notre manière de nous orienter vis-à-vis des êtres, et ceci doit commencer par une critique radicale et impitoyable de tous les aspects de notre monde moderne. » Ce second essai qui, à l’instar du premier, fut publié dans la revue TYR : Myth – Culture – Tradition est une continuation de Connaitre les dieux ; texte pionnier dans la démarche spirituelle de Cleary et faisant également office de « mindset ». Après un bref rappel des causes de notre « fermeture aux dieux » (« pour les modernes, la nature n’a essentiellement pas d’Être : elle attend que les humains lui confèrent une identité » et « en nous fermant à l’être de la nature, nous nous fermons simultanément à l’être des dieux. ») l’auteur rentre dans le vif en exprimant sa thèse : « notre émerveillement devant l’être de choses particulières est l’intuition d’un dieu, ou d’un être divin. »

Ce second essai qui, à l’instar du premier, fut publié dans la revue TYR : Myth – Culture – Tradition est une continuation de Connaitre les dieux ; texte pionnier dans la démarche spirituelle de Cleary et faisant également office de « mindset ». Après un bref rappel des causes de notre « fermeture aux dieux » (« pour les modernes, la nature n’a essentiellement pas d’Être : elle attend que les humains lui confèrent une identité » et « en nous fermant à l’être de la nature, nous nous fermons simultanément à l’être des dieux. ») l’auteur rentre dans le vif en exprimant sa thèse : « notre émerveillement devant l’être de choses particulières est l’intuition d’un dieu, ou d’un être divin. » Pour Alain de Benoist les dieux seraient des créations humaines dont le substantif consisterait en des valeurs anthropomorphisées, ce qui confirmerait la thèse d’un humanisme athée d’essence nietzschéenne et paganisant. Là se situe la divergence première entre Alain de Benoist et Collin Cleary : « Sa position est fondamentalement athée ; la mienne théiste ». D’où un questionnement légitime quant à la notion objective de vérité (religieuse), et encore une fois l’auteur de Comment peut-on être païen ?, au même titre que Nietzche, se complait dans un relativisme moral qui « découle de son engagement en faveur d’un relativisme général concernant la vérité en tant que telle ». « Là se trouve le problème-clé avec l’approche de Benoist concernant la vérité et les valeurs : il a simplement accepté la prémisse du monothéisme, selon laquelle le seul standard d’objectivité devrait se trouver à l’extérieur du monde. Rejetant l’idée qu’il existe un tel standard transcendant, il en tire la conclusion que l’objectivité est donc impossible ». Et en conclusion « le relativisme de Benoist concernant la vérité et les valeurs semble être tout à fait étranger au paganisme » si bien que « ces difficultés philosophiques avec cette position sont très graves, et probablement insurmontables ».

Pour Alain de Benoist les dieux seraient des créations humaines dont le substantif consisterait en des valeurs anthropomorphisées, ce qui confirmerait la thèse d’un humanisme athée d’essence nietzschéenne et paganisant. Là se situe la divergence première entre Alain de Benoist et Collin Cleary : « Sa position est fondamentalement athée ; la mienne théiste ». D’où un questionnement légitime quant à la notion objective de vérité (religieuse), et encore une fois l’auteur de Comment peut-on être païen ?, au même titre que Nietzche, se complait dans un relativisme moral qui « découle de son engagement en faveur d’un relativisme général concernant la vérité en tant que telle ». « Là se trouve le problème-clé avec l’approche de Benoist concernant la vérité et les valeurs : il a simplement accepté la prémisse du monothéisme, selon laquelle le seul standard d’objectivité devrait se trouver à l’extérieur du monde. Rejetant l’idée qu’il existe un tel standard transcendant, il en tire la conclusion que l’objectivité est donc impossible ». Et en conclusion « le relativisme de Benoist concernant la vérité et les valeurs semble être tout à fait étranger au paganisme » si bien que « ces difficultés philosophiques avec cette position sont très graves, et probablement insurmontables ».

Minerva aveva la sua festa nel giorno delle Quinquatrus, giorno che cadeva, come dice il nome, il quinto giorno oscuro dopo le Eidus: il giorno era in origine sicuramente dedicato a Mars, dato che in esso i Saliari celebravano uno dei loro riti, ma venne in seguito “usurpato” da Minerva, certo in coincidenza con la sovrapposizione della Triade etrusca Juppiter-Juno-Minerva all’arcaica Triade Juppiter -Mars-Quirinus.

Minerva aveva la sua festa nel giorno delle Quinquatrus, giorno che cadeva, come dice il nome, il quinto giorno oscuro dopo le Eidus: il giorno era in origine sicuramente dedicato a Mars, dato che in esso i Saliari celebravano uno dei loro riti, ma venne in seguito “usurpato” da Minerva, certo in coincidenza con la sovrapposizione della Triade etrusca Juppiter-Juno-Minerva all’arcaica Triade Juppiter -Mars-Quirinus.

Coupled to his assertion that the Germans had no Druids, Caesar was possibly making a declaration of their apparent primitivism and lack of philosophical gods and ideals. Surely no Roman would stoop to this? Caesar had his eyes on conquest…

Coupled to his assertion that the Germans had no Druids, Caesar was possibly making a declaration of their apparent primitivism and lack of philosophical gods and ideals. Surely no Roman would stoop to this? Caesar had his eyes on conquest…

![Fludd-SublimeSun(744x721)[1].jpg](http://euro-synergies.hautetfort.com/media/02/02/2842203225.jpg)

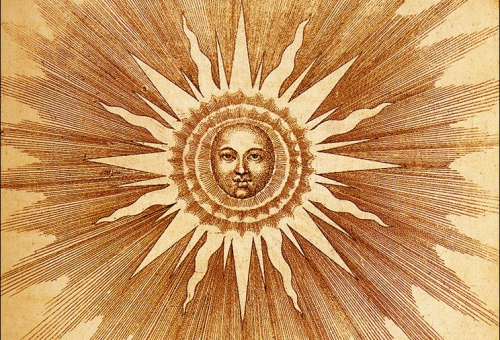

Dans la tradition égyptienne ancienne, le dieu le plus important du panthéon était le Soleil, qui était honoré sous différents noms selon les cités, mais qui portait dans toute l’Egypte le nom de Rê. En tant qu’Atoum-Rê, il apparaissait comme le dieu créateur du monde et sous les traits d’Amon-Rê comme un dieu souverain. Rê était également appelé Horus (Heru), sous la forme d’Horus l’ancien comme sous celle du fils d’Osiris et d’Isis. Le dieu Horus, son avatar sur la terre, aurait même guidé le peuple égyptien, à l’époque où ses ancêtres venaient d’Afrique du nord, sur cette nouvelle terre noire (Kemet) qui finit par porter son nom.

Dans la tradition égyptienne ancienne, le dieu le plus important du panthéon était le Soleil, qui était honoré sous différents noms selon les cités, mais qui portait dans toute l’Egypte le nom de Rê. En tant qu’Atoum-Rê, il apparaissait comme le dieu créateur du monde et sous les traits d’Amon-Rê comme un dieu souverain. Rê était également appelé Horus (Heru), sous la forme d’Horus l’ancien comme sous celle du fils d’Osiris et d’Isis. Le dieu Horus, son avatar sur la terre, aurait même guidé le peuple égyptien, à l’époque où ses ancêtres venaient d’Afrique du nord, sur cette nouvelle terre noire (Kemet) qui finit par porter son nom. IIIème siècle après J.C. L’empire romain est en crise. A l’est, les Sassanides, une Perse en pleine renaissance qui rêve de reconstituer l’empire de Darius. Au nord, les peuples européens « barbares » poussés à l’arrière par des vagues asiatiques et qui rêvent d’une place au soleil italique et/ou balkanique.

IIIème siècle après J.C. L’empire romain est en crise. A l’est, les Sassanides, une Perse en pleine renaissance qui rêve de reconstituer l’empire de Darius. Au nord, les peuples européens « barbares » poussés à l’arrière par des vagues asiatiques et qui rêvent d’une place au soleil italique et/ou balkanique.

Dans Le songe d'Empédocle, Christopher Gérard fait revivre le paganisme naturel et originel européen à la faveur d'un voyage initiatique et romanesque entrepris par un jeune homme de sa génération.

Dans Le songe d'Empédocle, Christopher Gérard fait revivre le paganisme naturel et originel européen à la faveur d'un voyage initiatique et romanesque entrepris par un jeune homme de sa génération.

Knut Hamsun

Knut Hamsun Hamsun

Hamsun Ce n’era abbastanza perché, alla maniera con cui gli americani e i sovietici usavano trattare i loro oppositori intellettuali, nel 1945 venisse giudicato pazzo e rinchiuso in manicomio, ripetendo la medesima via di passione imposta a Ezra Pound. Nel suo libro

Ce n’era abbastanza perché, alla maniera con cui gli americani e i sovietici usavano trattare i loro oppositori intellettuali, nel 1945 venisse giudicato pazzo e rinchiuso in manicomio, ripetendo la medesima via di passione imposta a Ezra Pound. Nel suo libro  Jan Stachniuk was born in 1905 in Kowel, Wołyń (in what is today Ukraine). In 1927, he began his public activity in Poznań, where he studied economics. There, he became active in the Union of Polish Democratic Youth and published his first books: Kolektywizm a naród (1933) and Heroiczna wspólnota narodu (1935). Beginning in 1937, Stachniuk published the monthly magazine Zadruga, which gave birth to a new idea current of the same name. In 1939, two additional books were published: Państwo a gospodarstwo and Dzieje bez dziejów (“History of unhistory”). During the Second World War, he inspired the ideology of the Faction of the National Rise (Stronnictwo Zrywu Narodowego) and the Cadre of Independent Poland (Kadra Polski Niepodległej). In 1943, Stachniuk published Zagadnienie totalizmu (with the help of the Faction). He fought in the Warsaw Uprising and was wounded. After the war, he failed to resume publishing Zadruga, but before the Stalinists attained power in the country, he managed to publish three more books: Walka o zasady, Człowieczeństwo i kultura, and Wspakultura. In 1949, Stachniuk was arrested and sentenced to death in a political show trial. The sentence was not carried out, and he got out of prison in 1955, but he was no longer able to perform any kind work. He died in 1963 and was buried in the Powązki Cemetery.

Jan Stachniuk was born in 1905 in Kowel, Wołyń (in what is today Ukraine). In 1927, he began his public activity in Poznań, where he studied economics. There, he became active in the Union of Polish Democratic Youth and published his first books: Kolektywizm a naród (1933) and Heroiczna wspólnota narodu (1935). Beginning in 1937, Stachniuk published the monthly magazine Zadruga, which gave birth to a new idea current of the same name. In 1939, two additional books were published: Państwo a gospodarstwo and Dzieje bez dziejów (“History of unhistory”). During the Second World War, he inspired the ideology of the Faction of the National Rise (Stronnictwo Zrywu Narodowego) and the Cadre of Independent Poland (Kadra Polski Niepodległej). In 1943, Stachniuk published Zagadnienie totalizmu (with the help of the Faction). He fought in the Warsaw Uprising and was wounded. After the war, he failed to resume publishing Zadruga, but before the Stalinists attained power in the country, he managed to publish three more books: Walka o zasady, Człowieczeństwo i kultura, and Wspakultura. In 1949, Stachniuk was arrested and sentenced to death in a political show trial. The sentence was not carried out, and he got out of prison in 1955, but he was no longer able to perform any kind work. He died in 1963 and was buried in the Powązki Cemetery. The sensation of the creative pressure, the feeling of the cosmic mission of creation, the desire to contribute to the creative world evolution by man is, in the lens of Culturalism, a sign of health and moral youth. According to Stachniuk, this is normal, the way it should be. Human history is the eternal antagonism of two, contradictory, directions—“the first one is the blind pressure of man towards panhumanism, the second is the escape into a solidified system.”

The sensation of the creative pressure, the feeling of the cosmic mission of creation, the desire to contribute to the creative world evolution by man is, in the lens of Culturalism, a sign of health and moral youth. According to Stachniuk, this is normal, the way it should be. Human history is the eternal antagonism of two, contradictory, directions—“the first one is the blind pressure of man towards panhumanism, the second is the escape into a solidified system.” Nachdem die Zahl der Anhänger der nordischen Glaubensrichtung sich auf Island seit dem Jahr 2000 verfünffacht hat, soll in der isländischen Hauptstadt Reykjavík erstmals seit der Wikingerzeit wiedereine heidnische Kultstätte entstehen.Nach der Christianisierung Islands im Jahre 1000 durfte das Heidentum nicht mehr praktiziert werden.

Nachdem die Zahl der Anhänger der nordischen Glaubensrichtung sich auf Island seit dem Jahr 2000 verfünffacht hat, soll in der isländischen Hauptstadt Reykjavík erstmals seit der Wikingerzeit wiedereine heidnische Kultstätte entstehen.Nach der Christianisierung Islands im Jahre 1000 durfte das Heidentum nicht mehr praktiziert werden.

Cette fresque mystico-politique a été écrite dans un village du Nouveau-Mexique en 1925. L’action se passe au Mexique, riche de son passé, mais usé, décadent, vidé de sa substance par les trois grands maux apportés par l’homme blanc, qui sont (selon Lawrence) le Christianisme, l’

Cette fresque mystico-politique a été écrite dans un village du Nouveau-Mexique en 1925. L’action se passe au Mexique, riche de son passé, mais usé, décadent, vidé de sa substance par les trois grands maux apportés par l’homme blanc, qui sont (selon Lawrence) le Christianisme, l’ Et le jour venu, c’est sans état d’âme qu’elle accomplira son destin. Une autre nouvelle du même recueil, intitulée Soleil, reprend encore ce thème de la femme mûre insatisfaite de son existence, mais il est traité de manière beaucoup plus pacifique, comme un conte naturiste. Juliette quitte les États-Unis, où elle dépérit, pour le Soleil de la Méditerranée. Là commencera pour elle une nouvelle existence à travers un face à face quotidien avec l’Astre divin (évoquant l’expérience d’Anna de Noailles [4]). Elle s’épanouira enfin sous ses rayons qui harmonisent à la fois le corps et l’âme :

Et le jour venu, c’est sans état d’âme qu’elle accomplira son destin. Une autre nouvelle du même recueil, intitulée Soleil, reprend encore ce thème de la femme mûre insatisfaite de son existence, mais il est traité de manière beaucoup plus pacifique, comme un conte naturiste. Juliette quitte les États-Unis, où elle dépérit, pour le Soleil de la Méditerranée. Là commencera pour elle une nouvelle existence à travers un face à face quotidien avec l’Astre divin (évoquant l’expérience d’Anna de Noailles [4]). Elle s’épanouira enfin sous ses rayons qui harmonisent à la fois le corps et l’âme : Cette pensée, que Lawrence exprime de manière allégorique dans ses romans et nouvelles, sera explicite dans son dernier ouvrage, paru un an après sa mort, et qui représente son testament spirituel. Apocalypse est l’étude fouillée du texte de Jean de Patmos, qui clôt le Nouveau Testament. Si la notion même d’apocalypse lui répugne, à cause de cet « ignoble désir de fin du monde », Lawrence s’intéresse à cet écrit car il y découvre deux influences opposées. Tout d’abord, le message de ceux qui « ne peuvent même pas supporter l’existence de la Lune et du Soleil », mais par-delà la strate judéo-chrétienne, il y trouve une strate païenne. Car pour faire passer de manière frappante cette vision apocalyptique, le ou les auteurs ont eu recours à un langage, à une symbolique cosmiques, donc païens (5). L’étude de l’Apocalypse est ainsi pour Lawrence prétexte à comparer entre elles ces deux conceptions du monde antagonistes :

Cette pensée, que Lawrence exprime de manière allégorique dans ses romans et nouvelles, sera explicite dans son dernier ouvrage, paru un an après sa mort, et qui représente son testament spirituel. Apocalypse est l’étude fouillée du texte de Jean de Patmos, qui clôt le Nouveau Testament. Si la notion même d’apocalypse lui répugne, à cause de cet « ignoble désir de fin du monde », Lawrence s’intéresse à cet écrit car il y découvre deux influences opposées. Tout d’abord, le message de ceux qui « ne peuvent même pas supporter l’existence de la Lune et du Soleil », mais par-delà la strate judéo-chrétienne, il y trouve une strate païenne. Car pour faire passer de manière frappante cette vision apocalyptique, le ou les auteurs ont eu recours à un langage, à une symbolique cosmiques, donc païens (5). L’étude de l’Apocalypse est ainsi pour Lawrence prétexte à comparer entre elles ces deux conceptions du monde antagonistes :

Peter Bickenbach

Peter Bickenbach

Mythes et symboles de la tradition romaine seront étudiés sur le plan spirituel par Evola en personne, Giovanni Costa (auteur en 1923 d’une Apologie du Paganisme), Massimo Scaligero, du jeune Angelo Brelich (qui occupera après la guerre la chaire d’Histoire des Religions du Monde classique à l’Université de Rome), Guido De Giorgio, ainsi que par des collaborateurs étrangers comme Franz Altheim et Edmund Dodsworth. Mais ici, le discours est devenu purement culturel, ou, tout au plus, anthropologique : l’aspect religieux et spirituel manque et l’intérêt pour le rituel est inexistant.

Mythes et symboles de la tradition romaine seront étudiés sur le plan spirituel par Evola en personne, Giovanni Costa (auteur en 1923 d’une Apologie du Paganisme), Massimo Scaligero, du jeune Angelo Brelich (qui occupera après la guerre la chaire d’Histoire des Religions du Monde classique à l’Université de Rome), Guido De Giorgio, ainsi que par des collaborateurs étrangers comme Franz Altheim et Edmund Dodsworth. Mais ici, le discours est devenu purement culturel, ou, tout au plus, anthropologique : l’aspect religieux et spirituel manque et l’intérêt pour le rituel est inexistant.

In the Hebrew scriptures of the Jewish religion, known as the Old Testament in the Christian Bible, there occurs a single instance of the word “solstice” that is not in any way associated with the annual summer and winter astronomical events. In the book of Joshua, chapter 10 and verses 12 to 14, it is reported that the tribal deity of ancient Israel, called YHWH, caused the sun to stand still in Gibeon to give the Israelites, known to be the people of the said tribal deity, the best opportunity to slaughter and annihilate, in broad daylight, an enemy tribe called the Amorites.

In the Hebrew scriptures of the Jewish religion, known as the Old Testament in the Christian Bible, there occurs a single instance of the word “solstice” that is not in any way associated with the annual summer and winter astronomical events. In the book of Joshua, chapter 10 and verses 12 to 14, it is reported that the tribal deity of ancient Israel, called YHWH, caused the sun to stand still in Gibeon to give the Israelites, known to be the people of the said tribal deity, the best opportunity to slaughter and annihilate, in broad daylight, an enemy tribe called the Amorites.