Tecnicidad, Biopolítica y Decadencia.

Comentarios al libro "El Hombre y la Técnica" de Oswald Spengler.

Carlos Javier Blanco Martín

Resumen. El presente artículo es un comentario detenido de la pequeña obra de Oswald Spengler "El Hombre y la Técnica". En él desarrollamos el concepto de tecnicidad, necesario para comprender la amplia perspectiva (zoológica, naturalista, dialéctica, operatiológica) esbozada por el filósofo alemán. No se trata de un ensayo sobre la Técnica en el sentido artefactual y objetivo sino sobre el desarrollo de las capacidades operatorias (viso-quirúrgicas) de los ancestros del hombre, que lo llevaron desde la depredación hasta la Cultura, y desde la Cultura hasta la decadencia. Especialmente la decadencia de los pueblos occidentales que más han contribuido al despegue de esa tecnicidad.

Abstract. This article is a detailed commentary on Oswald Spengler's little work "The Man and the Technique". In it we develop the concept of technicality, necessary to understand the broad perspective (zoological, naturalistic, dialectic, operatiological) outlined by the German philosopher. This is not an essay on the Technique in the objective and artifactual sense, but rather on the development of the operative capacities (visual and manual) of the ancestors of man, which led him from predation to Culture, and from Culture to decline: especially the decadence of the western peoples that have contributed most to the takeoff of this technicality

Introducción. Justificación del presente comentario. Indagaciones sobre la Tecnicidad según Oswald Spengler.

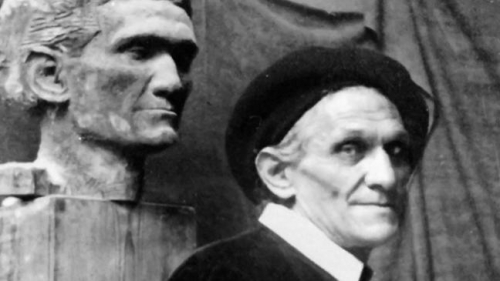

En un trabajo anterior ya quisimos hacer una aproximación antropológica al concepto spengleriano de la Técnica[i] . El presente trabajo quiere ser una prolongación del mismo, profundizando en los conceptos spenglerianos sobre la tecnicidad y lo hacemos por medio de un comentario detenido de las páginas de su pequeña obra El Hombre y la Técnica.[ii] Este breve texto spengleriano aclara muchos aspectos de la filosofía, poco sistemática y, a veces, impresionista, del gran pensador alemán, el creador de la magna obra La Decadencia de Occidente. Este breve libro traza un cuadro evolutivo de la técnica en la historia natural y cultural del hombre. Pero hace algo más: esboza de una manera dialéctica el destino fatal de los pueblos de Occidente, pueblos que han desarrollado toda su tecnicidad hasta ponerla en manos de sus enemigos. Este examen detenido de los párrafos enérgicos y vibrantes del librito puede ayudar a comprender la peculiar dialéctica pesimista –a diferencia de la optimista hegeliana- del pensador alemán Oswald Spengler. En vez de alcanzar un progresivo dominio técnico del mundo, encaminado a su mayor comodidad y salud, el hombre y sus antepasados simplemente han ido diferenciando cualidades sensitivo-etológicas desde hace millones de años, cualidades en las que ya está presente la tecnicidad, aun cuando todavía nuestros antepasados no era capaces de fabricar herramientas, o sólo empleaban órganos y partes sensomotoras de su cuerpo para ejercer su dominio. Por ello, en nuestro comentario empleamos el término tecnicidad, contrapuesto a "técnica" para hacer referencia a esas capacidades generales implícitas a la hora de ejercer dominio, control o alteración del propio medio envolvente, con independencia de la existencia de herramientas, armas u otros objetos extra-somáticos. La tecnicidad es la cualidad o el carácter técnico de algo o alguien, y no se debe circunscribir a los productos de las artes humanas o proto-humanas ni al aspecto normativo o envolvente del Espíritu Objetivo. Nuestro comentario, pues, se enmarca en el espacio antropológico. Queremos ahondar en la antropología spengleriana, tal y como llevamos haciendo desde hace unos años. [iii]

En un trabajo anterior ya quisimos hacer una aproximación antropológica al concepto spengleriano de la Técnica[i] . El presente trabajo quiere ser una prolongación del mismo, profundizando en los conceptos spenglerianos sobre la tecnicidad y lo hacemos por medio de un comentario detenido de las páginas de su pequeña obra El Hombre y la Técnica.[ii] Este breve texto spengleriano aclara muchos aspectos de la filosofía, poco sistemática y, a veces, impresionista, del gran pensador alemán, el creador de la magna obra La Decadencia de Occidente. Este breve libro traza un cuadro evolutivo de la técnica en la historia natural y cultural del hombre. Pero hace algo más: esboza de una manera dialéctica el destino fatal de los pueblos de Occidente, pueblos que han desarrollado toda su tecnicidad hasta ponerla en manos de sus enemigos. Este examen detenido de los párrafos enérgicos y vibrantes del librito puede ayudar a comprender la peculiar dialéctica pesimista –a diferencia de la optimista hegeliana- del pensador alemán Oswald Spengler. En vez de alcanzar un progresivo dominio técnico del mundo, encaminado a su mayor comodidad y salud, el hombre y sus antepasados simplemente han ido diferenciando cualidades sensitivo-etológicas desde hace millones de años, cualidades en las que ya está presente la tecnicidad, aun cuando todavía nuestros antepasados no era capaces de fabricar herramientas, o sólo empleaban órganos y partes sensomotoras de su cuerpo para ejercer su dominio. Por ello, en nuestro comentario empleamos el término tecnicidad, contrapuesto a "técnica" para hacer referencia a esas capacidades generales implícitas a la hora de ejercer dominio, control o alteración del propio medio envolvente, con independencia de la existencia de herramientas, armas u otros objetos extra-somáticos. La tecnicidad es la cualidad o el carácter técnico de algo o alguien, y no se debe circunscribir a los productos de las artes humanas o proto-humanas ni al aspecto normativo o envolvente del Espíritu Objetivo. Nuestro comentario, pues, se enmarca en el espacio antropológico. Queremos ahondar en la antropología spengleriana, tal y como llevamos haciendo desde hace unos años. [iii]

- El concepto de tecnicidad.

Spengler comienza su estudio sobre la técnica mostrando su olímpico desprecio hacia las charlas del siglo XVIII y XIX sobre la "cultura". Desde las robinsonadas al mito del "buen salvaje", los "hombres de cultura" que habían llenado los salones europeos de aquellos años habían olvidado por completo el verdadero papel de la técnica en la civilización. El arte, la poesía, la novela, la cultura entendida como segunda naturaleza sublime del hombre, relumbraban en la mente de ilustrados y románticos, y con ese resplandor se cegaban a las realidades terribles de que estaba preñado el siglo XX, cuando el contexto geopolítico, social y económico ya había mutado por completo y la Ilustración o el romanticismo sólo habitaba en la mente retardataria de los demagogos y los "intelectuales", no en los hombres fácticos y de acción. El escalpelo de Spengler se extiende hasta los utilitaristas ingleses. Para ellos la técnica era el recurso idóneo para instaurar la holgazanería en el mundo:

Aber nützlich war, was dem »Glück der Meisten« diente. Und Glück bestand im Nichtstun. Das ist im letzten Grunde die Lehre von Bentham, Mill und Spencer. Das Ziel der Menschheit bestand darin, dem einzelnen einen möglichst großen Teil der Arbeit abzunehmen und der Maschine aufzubürden. Freiheit vom »Elend der Lohnsklaverei« und Gleichheit im Amüsement, Behagen und »Kunstgenuß«: das »panem et circenses« der späten Weltstädte meldet sich an. Die Fortschrittsphilister begeisterten sich über jeden Druckknopf, der eine Vorrichtung in Bewegung setzte, die – angeblich – menschliche Arbeit ersparte. An Stelle der echten Religion früher Zeiten tritt die platte Schwärmerei für die »Errungenschaften der Menschheit«, worunter lediglich Fortschritte der arbeitersparenden und amüsierenden Technik verstanden wurden. Von der Seele war nicht die Rede.

"Útil, empero, era lo que sirve a la "felicidad del mayor número". Y esta felicidad consistía en no hacer nada. Tal es, en último término, la doctrina de Bentam, Mill y Spencer, El fin de la Humanidad consistía en aliviar al individuo de la mayor cantidad posible de trabajo, cargándola a la máquina. Libertad de "la miseria, de la esclavitud asalariada" [Elend der Lohnsklaverei] e igualdad en diversiones, bienandanza y “deleite artístico”. Anúnciase el panem et circenses de las urbes mundiales en las épocas de decadencia. Los filisteos de la cultura se entusiasmaban a cada botón que ponía en marcha un dispositivo y que, al parecer, ahorraba trabajo humano. En lugar de la auténtica religión de épocas pasadas, aparece el superficial entusiasmo “por las conquistas de la Humanidad” [Errungenschaften der Menschheit], considerando como tales exclusivamente los progresos de la técnica, destinados a ahorrar trabajo y a divertir a los hombres. Pero del alma, ni una palabra." [iv]

La técnica para el utilitarismo inglés era vista como instancia ahorradora de trabajo, como mera herramienta liberadora de esclavitud del trabajo asalariado, pero no como la esencia misma del hombre fáustico, del hombre que transforma el mundo, que lo modifica substancialmente. Oswald Spengler repudia con toda su rabia y fuerzas ese sentimentalismo vulgar que arranca de Rousseau, de los románticos y también de los "progresistas". Un sentimentalismo que reduce la filosofía de la Historia a mero "optimismo", esto es, un estado de ánimo confiado y tranquilizador en el cual ya no habrá más guerras ni dominaciones de unos pueblos sobre otros. Un estado de quietud que, al modo más nietzscheano, Spengler intuye como deprimente, laminador, una antesala de un suicidio colectivo, un estado alienado y de falsedad. La Historia de los hombres sigue su curso con completa independencia de sus deseos, anhelos y expectativas. Como acontece con las leyes de la naturaleza, inexorables y devoradoras de civilizaciones, razas y universos enteros, las "leyes" de la historia siguen su marcha con independencia absoluta de nuestra mente.

Para comprender los tiempos, al hombre, a la vida que nos toca –históricamente- vivir, se precisa de una facultad especial, el "tacto fisiognómico":

Der physiognomische Takt, wie ich das bezeichnet habe, was allein zum Eindringen in den Sinn alles Geschehens befähigt, der Blick Goethes, der Blick geborener Menschenkenner, Lebenskenner, Geschichtskenner über die Zeiten hin erschließt im einzelnen dessen tiefere Bedeutung.

"El tacto fisiognómico, como he denominado la facultad que nos permite penetrar en el sentido de todo acontecer; la mirada de Goethe, la mirada de los que conocen a los hombres y conocen la vida, y conocen la Historia y contemplan los tiempos, es la que descubre en lo particular su significación profunda" [v].

El naturalismo, el determinismo, de la misma manera que el "culturalismo", se mostrarán incapaces de comprender el significado de la técnica en la historia de los hombres. Hace falta el tacto fisiognómico, es preciso sentir esa especie de empatía o intuición hacia lo que hacen las distintas clases de hombres, para así poder insertar adecuadamente el papel de la técnica en la cultura. La técnica no es la pariente pobre de la Cultura. No se trata de la versión ínfima de "cuanto puede hacer el Homo sapiens". Esta especie "sapiente" que construye catedrales góticas, compone sinfonías, escribe El Quijote, la Suma Teológica o la Ilíada, es también la especie que ha comenzado empuñando palos, forjado espadas o construido cañones anti-aéreos. La técnica –y de entre ella, la técnica depredatorio-bélica- sería la versión grisácea, deprimente, prosaica de la sublime Cultura. El naturalismo verá la evolución desde la maza asesina hasta el cohete espacial (recordemos la genial escena cinematográfica de Stanley Kubrick en 2001, Una Odisea Espacial). El determinismo, cercano al naturalismo y, a veces, complementario de éste, verá en la técnica una condición sine qua non de la Cultura sublime, condición que habrá que retirar del escenario convenientemente cuando ya actúe la Cultura sublime (Bellas Artes, Poesía, Espíritu, etc.). Finalmente, el "culturalismo", que Spengler detesta, pues representa el idealismo y la ceguera ignorante de los "literatos", escinde en dos la vida humana, una mitad sublime y otra prosaica; la mitad "prosaica" es condenada a la oscuridad por el idealismo rampante (pero también por el utilitarismo y el materialismo dialéctico) una vez que ha brotado la Cultura. Pero he aquí que el Filósofo de la Historia no puede ni debe dejar de lado aquello que es consustancial a la vida humana en su devenir. La técnica, reivindicada ahora por Spengler desde un naturalismo mucho más profundo, es esencial a la vida misma de todos los animales. La técnica no es la colección de "cosas" que ha producido el hombre para matar, destruir, crear, dominar. La técnica no se deja reducir a un estudio "supra-orgánico", "extra-somático", "objetivo". En la propia organicidad animal ya está presente la técnica:

Das ist der andre Fehler, der hier vermieden werden muß: Technik ist nicht vom Werkzeug her zu verstehen. Es kommt nicht auf die Herstellung von Dingen an, sondern auf das Verfahren mit ihnen, nicht auf die Waffe, sondern auf den Kampf

Das ist der andre Fehler, der hier vermieden werden muß: Technik ist nicht vom Werkzeug her zu verstehen. Es kommt nicht auf die Herstellung von Dingen an, sondern auf das Verfahren mit ihnen, nicht auf die Waffe, sondern auf den Kampf

"Este es el otro error que debe evitarse aquí: la técnica no debe comprenderse partiendo de la herramienta. No se trata de la fabricación de cosas, sino del manejo de ellas; no se trata de las armas, sino de la lucha."[vi]

La técnica no es la herramienta [Werkzeug], una suerte de prolongación extra-somática y objetiva del sujeto humano. La técnica, en realidad, es el manejo [Verfahren] con las cosas. Este es el corazón del comienzo del librito de Spengler: la técnica es la táctica de la vida. La vida no es una colección de cosas, a saber: sujetos corpóreos y objetos producidos por esos sujetos corpóreos. Esta sería la miope visión compartida al alimón por idealistas y por realistas. Los primeros se fijan en la "creatividad" del sujeto hacedor (se "crean" tanto obras de arte como misiles de cabeza nuclear), y los segundos paran mientes en lo creado. Pero en medio está la vida misma, la acción, a saber, el uso de los medios para la lucha.

- La Biopolítica spengleriana. Un naturalismo dialéctico.

La vida es comprendida como una guerra ya en sus más arcaicos estratos zoológicos.

Es gibt keinen »Menschen an sich«, wie die Philosophen schwatzen, sondern nur Menschen zu einer Zeit, an einem Ort, von einer Rasse, einer persönlichen Art, die sich im Kampfe mit einer gegebenen Welt durchsetzt oder unterliegt, während das Weltall göttlich unbekümmert ringsum verweilt. Dieser Kampf ist das Leben, und zwar im Sinne Nietzsches als ein Kampf aus dem Willen zur Macht, grausam, unerbittlich, ein Kampf ohne Gnade.

"No existe el “hombre en sí” — palabrería de filósofos —, sino sólo los hombres de una época, de un lugar, de una raza, de una índole personal, que se imponen en lucha con un mundo dado, o sucumben, mientras el universo prosigue en torno su curso, como deidad erguida en magnífica indiferencia. Esa lucha es la vida; y lo es, en el sentido de Nietzsche, como una lucha que brota de la voluntad de poderío; lucha cruel, sin tregua; lucha sin cuartel ni merced" [vii] .

Si Spengler rechaza tanto el idealismo como el realismo en su tratamiento de la técnica, otro tanto se ha de decir de la "antropología predicativa". "El hombre"… ¿qué es? Si hablamos de un Homo faber –hombre fabricante- pensado con el mismo formato que el concepto de Homo sapiens, sapiente, estamos eligiendo un predicado esencial que definirá a esta especie animal concreta a la que pertenecemos. Hay poca ganancia con respecto a estas antropologías tradicionales si al Homo, a nuestro género, le añadimos el predicado de "animal técnico". No existe el "hombre en sí" [Es gibt keinen »Menschen an sich«]. No hay tal cosa previamente definida, recortada, a la cual podamos asignarle (casi, podríamos decir "inyectarle") la cualidad esencial de su tecnicidad, de la misma manera que antaño se decía del hombre que era un "animal social" o "animal racional". No hay que hablar de tecnicidad de ese "Hombre" pre-dado . De lo que se ha de hablar es de una lucha cósmica eterna, en la que se insertan los seres vivos de todas las escalas zoológicas. A las enormes galaxias y a los descomunales astros les resulta por completo indiferente el resultado de esta minúscula guerra, una contienda ésta que para sus héroes y víctimas sin embargo les es esencial. La antroposfera de éste diminuto planeta es una capa extrafina y efímera que nada importa en el decurso del universo. Los hombres mueren por "pequeñas cosas" desde el punto de vista cósmico, aun cuando esas "pequeñeces" como la defensa de la patria, la preservación de un ideal, de una civilización o una fe comporten un valor infinito a los actores humanos.

Y estos supuestos valores supremos, relativos entre las mismas culturas humanas, y susceptibles de relativización a escalas supra-humanas, cósmicas, son en gran medida "mentira" si tras de ellos captamos su esencia: la voluntad de poder. En efecto, según Spengler, "el hombre es un animal de rapiña" [viii] [Denn der Mensch ist ein Raubtier.]. Depredador, es la palabra castellana que de la manera más neutra y zoológica describe nuestra condición. A años luz nos hallamos de los herbívoros. La clave de nuestra evolución como primates estriba en la depredación. El hombre como depredador encarna un estilo de vida, una complexión físico-espiritual que los métodos naturalistas groseros no podrán captar. Sabido es que Spengler apuesta por el naturalismo de Goethe y de la fisiognómica, y no por el materialismo de Linneo y de Darwin. Las "ciencias de la vida" estudian cadáveres y compuestos físico-químicos, diseccionan y clasifican, buscan causas deterministas al modo mecanicista, pero renuncian y hasta desprecian "el tacto fisiognómico". Este tacto, imprescindible para la comprensión de la vida, nos da la clave de la tecnicidad. La clave consiste en una superación del carácter pasivo de los sujetos vivos. De la planta podemos decir que "en ella y en torno a ella está la vida" más que afirmar, propiamente, que es un ser vivo[ix]. En rigor, es un "escenario" [Schauplatz] de los procesos vivientes.

Eine Pflanze lebt, obwohl sie nur im eingeschränkten Sinne ein Lebewesen ist. In Wirklichkeit lebt es in ihr oder um sie herum. »Sie« atmet, »sie« nährt sich, »sie« vermehrt sich, und trotzdem ist sie ganz eigentlich nur der Schauplatz dieser Vorgänge, die mit solchen der umgebenden Natur, mit Tag und Nacht, mit Sonnenbestrahlung und der Gärung im Boden eine Einheit bilden, so daß die Pflanze selbst nicht wollen und wählen kann. Alles geschieht mit ihr und in ihr. Sie sucht weder den Standort, noch die Nahrung, noch die andere Pflanze, mit welcher sie die Nachkommen erzeugt. Sie bewegt sich nicht, sondern der Wind, die Wärme, das Licht bewegen sie.

"La planta vive; aunque sólo en sentido limitado, es un ser viviente. En realidad, más que vivir puede decirse que en ella y en torno a ella está la vida. “Ella” respira, “ella” se alimenta, “ella” se multiplica; y, sin embargo, no es propiamente más que el escenario de esos procesos, que constituyen una unidad con los procesos de la naturaleza circundante, con el día y la noche, con los rayos del sol y la fermentación del suelo; de suerte que la planta misma no puede ni querer ni elegir. Todo acontece con ella y en ella. Ella no busca ni su lugar propio, ni su alimento, ni las demás plantas con quienes engendra su sucesión. No se mueve, sino que son el viento, el calor, la luz, quienes la mueven." [x]

"La planta vive; aunque sólo en sentido limitado, es un ser viviente. En realidad, más que vivir puede decirse que en ella y en torno a ella está la vida. “Ella” respira, “ella” se alimenta, “ella” se multiplica; y, sin embargo, no es propiamente más que el escenario de esos procesos, que constituyen una unidad con los procesos de la naturaleza circundante, con el día y la noche, con los rayos del sol y la fermentación del suelo; de suerte que la planta misma no puede ni querer ni elegir. Todo acontece con ella y en ella. Ella no busca ni su lugar propio, ni su alimento, ni las demás plantas con quienes engendra su sucesión. No se mueve, sino que son el viento, el calor, la luz, quienes la mueven." [x]

La vida, pues, en su estrato ínfimo, vegetal, si bien es un entrecruzamiento de procesos vitales (ellos mismos activos), el sujeto o "escenario" donde acontecen consiste, no obstante, en un mero receptáculo dominado por la pasividad. La vida vegetal es sometimiento al mundo-entorno [umgebenden Natur], a la naturaleza envolvente. A su vez, la vida vegetal es el sustrato sobre el que se asienta la "vida movediza" [freibewegliche Leben], esto es, el Reino animal. El carácter móvil, auto-portátil por así decir, de la vida animal es ya una forma de libertad, de sobre-posición, por encima de la situación pasiva y sometida del vegetal. Pero la movilidad libre de las criaturas animales está, a su vez, dividida en dos escalones: la vida del herbívoro, hecha para huir, y la vida del carnívoro, para depredar.

Es a través de la primacía de alguno de los sentidos como se crea un mundo-entorno específico para cada uno de los dos escalones de lo animal. El oído para los herbívoros, nacidos para huir o caer como presas, y el ojo –la mirada- para los cazadores, los más libres y sagaces de entre los animales. Este predominio sensorial unilateral, según parece decirnos Spengler, determina los distintos mundos-entorno.

Erst durch die geheimnisvolle und von keinem menschlichen Nachdenken zu erklärende Art der Beziehungen zwischen dem Tier und seiner Umgebung mittels der tastenden, ordnenden, verstehenden Sinne entsteht aus der Umgebung eine Umwelt für jedes einzelne Wesen. Die höheren Pflanzenfresser werden neben dem Gehör vor allem durch die Witterung beherrscht, die höheren Raubtiere aber herrschen durch das Auge. Die Witterung ist der eigentliche Sinn der Verteidigung. Die Nase spürt Herkunft und Entfernung der Gefahr und gibt damit der Fluchtbewegung eine zweckmäßige Richtung von etwas fort.

"La misteriosa índole — por ninguna reflexión humana explicable — de las relaciones entre el animal y su contorno, mediante los sentidos palpadores, ordenadores e intelectivos, es la que convierte el contorno en un mundo circundante para cada ser en particular. Los herbívoros superiores son dominados por el oído y, sobre todo, por el olfato. Los rapaces superiores, en cambio, dominan por la mirada. El olfato es el sentido propio de la defensa. Por la nariz rastrea el animal el origen y la distancia del peligro, dando así a los movimientos de huida una dirección conveniente: la dirección que se aleja del peligro. [xi]

El "contorno" [Umgebung] al cual todavía se veía sometida la planta, es en el animal un mundo-entorno [Umwelt]. Cada especie animal lo percibe a su modo. Las teorías de von Uexküll, conocidas por Spengler, resuenan aquí. Pero ese mundo percibido de manera distinta por cada especie determina, a su vez, una básica relación de poder, la relación de dominante a dominado. De la Biología teórica se pasa recta y necesariamente a una Biopolítica. En la propia Biología teórica se pre-contiene la base zoológica del Poder. La mirada del animal de presa es ya una mirada que busca obtener botín y dominio, que fija rectilínea y frontalmente sus objetivos.

Para el depredador, "el mundo es la presa" [Die Welt ist die Beute]. Spengler nos describe así el origen de la Cultura, la raíz del mundo histórico específico del ser humano. Justamente como el hueso-maza, el arma letal en manos de un simio, se transforma en la película 2001 Una Odisea Espacial, en un artefacto cosmonáutico, la tecnicidad del hombre hunde sus raíces en el propio escalonamiento superior del ancestro, el homínida comedor y cazador de otros animales.

Ein unendliches Machtgefühl liegt in diesem weiten ruhigen Blick, ein Gefühl der Freiheit, die aus Überlegenheit entspringt und auf der größeren Gewalt beruht, und die Gewißheit, niemandes Beute zu sein. Die Welt ist die Beute, und aus dieser Tatsache ist letzten Endes die menschliche Kultur erwachsen

"Un sentimiento infinito de poderío palpita en esa mirada larga y tranquila; un sentimiento de libertad que brota de la superioridad y descansa en el mayor poder, en la certidumbre de no ser nunca botín ni presa de nadie. El mundo es la presa; y de este hecho, en último término, ha nacido toda la cultura humana." [xii]

Esa mirada poderosa, unida a ese sentimiento de poder, es el germen de la Historia. Y la Historia se individualiza. No se trata de una historia de las masas. Las masas no poseen la historia. Antes de alzarse culturas individualizadas, en la fase zoológica y pre-cultural, la Historia la hacen los individuos. El animal de presa destaca y se recorta ante el animal de rebaño. El herbívoro precisa de muchos como él, y entre ellos (como luego, en las sociedades de masas) una muchedumbre de iguales constituye ya el individuo. Ha de verse aquí, en El Hombre y la Técnica, no una teoría, en el sentido riguroso o científico, sino una analogía. Spengler discurre por analogías, y esas analogías presiden toda su filosofía de la historia. Si una Cultura es, toda ella, un ser vivo dotado de su morfología propia y de su propio ciclo vital, un herbívoro es un análogo de un "hombre masa". El hombre masa del siglo XIX y XX es un retroceso hacia la animalización, pero hacia la animalización del escalón inferior, la de la presa, la del cobarde herbívoro.

Esa mirada poderosa, unida a ese sentimiento de poder, es el germen de la Historia. Y la Historia se individualiza. No se trata de una historia de las masas. Las masas no poseen la historia. Antes de alzarse culturas individualizadas, en la fase zoológica y pre-cultural, la Historia la hacen los individuos. El animal de presa destaca y se recorta ante el animal de rebaño. El herbívoro precisa de muchos como él, y entre ellos (como luego, en las sociedades de masas) una muchedumbre de iguales constituye ya el individuo. Ha de verse aquí, en El Hombre y la Técnica, no una teoría, en el sentido riguroso o científico, sino una analogía. Spengler discurre por analogías, y esas analogías presiden toda su filosofía de la historia. Si una Cultura es, toda ella, un ser vivo dotado de su morfología propia y de su propio ciclo vital, un herbívoro es un análogo de un "hombre masa". El hombre masa del siglo XIX y XX es un retroceso hacia la animalización, pero hacia la animalización del escalón inferior, la de la presa, la del cobarde herbívoro.

La analogía naturalista de Spengler discurre por canales muy diversos al naturalismo metafísico de Schopenhauer, aunque también conduce al pesimismo, o el de Darwin que induce a pensar en términos progresistas y, por ende, optimistas. El hombre es más que un mono. El hombre es más que un cuerpo que, por búsqueda de homologías rigurosas, esté próximo a los primates. La anatomía evolucionista, y, antes que ella, el comparatismo linneano, tratan ante todo con cadáveres. Los cuerpos estáticos de los científicos naturales son, en opinión de Spengler, naturalezas muertas. Frente a esta biología cadavérica Spengler busca el contacto con una filosofía de la biología de los cuerpos en acción. Tal concepción encuentra analogías en las acciones mismas. De tales analogías no hay razones para quejarse de un "antropomorfismo". Decir que es antropomorfismo que ciertos insectos "conocen la agricultura" o "practican la esclavitud", por ejemplo, sólo podría justificarse si admitiéramos que el hombre es un punto de vista privilegiado. De manera cerrada, y por tanto "ilógica", el círculo del antropomorfismo ve antropomorfismo en nuestras atribuciones acerca de las acciones de los animales. Lo que Spengler quiere decirnos simplemente es que la aparición de instituciones culturales, históricas, cuenta siempre con análogos zoológicos. El plano institucional en el que se puede hablar, como historiador, de una agricultura, una milicia, un Estado, una técnica, una esclavitud en una cultura humana es un plano que "corta" geométricamente con el plano zoológico y con el cual, al menos, hay una recta, una línea de puntos muy reales, donde también estarán presentes esos análogos.

- La tecnicidad y la analogía zoológica.

Ciñéndonos a la tecnicidad, Spengler la quiere ver en las más diversas escalas zoológicas, como ya llevamos visto. Pero no obstante se trata de una tecnicidad muy diversa. Y es que el método analógico, de gran aplicación en filosofías muy distintas a la spengleriana (p.e. en el tomismo) nos recuerda que la relación entre dos términos en parte distintos y en parte semejantes puede establecerse en orden a penetrar de alguna manera en un sector ignoto del mundo. Esta relación de analogía, y no de identidad, es legítima, cuidando de no bascular nunca hacia la univocidad ni hacia la equivocidad. Es una relación susceptible de quedar establecida en función de una proporción o regla. La técnica de los animales es análoga a la de los animales, pero no lo es en todos los aspectos ni en la misma medida. Los castores hacen presas y los ingenieros humanos también. Pero no igual, no en la misma medida. La tecnicidad del hombre es, por así decir, diferenciada. En el hombre se da la individualidad mientras que en el animal esa individualidad se pierde y se difumina en la especie:

Die Technik dieser Tiere ist Gattungstechnik.

"La técnica de los animales es técnica de la especie". [xiii]

La de los animales no humanos es técnica genérica (Gattung). Está incorporada en su instinto, y es invariable. El sujeto es aquí, como vimos en el caso de las plantas, un vehículo o escenario de la voz de la especie. Es una técnica no individualizada, invariable.[xiv]

Die Menschentechnik und sie allein aber ist unabhängig vom Leben der Menschengattung. Es ist der einzige Fall in der gesamten Geschichte des Lebens, daß das Einzelwesen aus dem Zwang der Gattung heraustritt. Man muß lange nachdenken, um das Ungeheure dieser Tatsache zu begreifen. Die Technik im Leben des Menschen ist bewußt, willkürlich, veränderlich, persönlich, erfinderisch. Sie wird erlernt und verbessert. Der Mensch ist der Schöpfer seiner Lebenstaktik geworden. Sie ist seine Größe und sein Verhängnis. Und die innere Form dieses schöpferischen Lebens nennen wir Kultur, Kultur besitzen, Kultur schaffen, an der Kultur leiden. Die Schöpfungen des Menschen sind Ausdruck dieses Daseins in persönlicher Form.

"La técnica humana, y sólo ella, es, empero, independiente de la vida de la especie humana. Es el único caso, en toda la historia de la vida, en que el ser individual escapa a la coacción de la especie. Hay que meditar mucho para comprender lo enorme de este hecho. La técnica en la vida del hombre es consciente, voluntaria, variable, personal, inventiva. Se aprende y se mejora. El hombre es el creador de su táctica vital. Esta es su grandeza y su fatalidad. Y la forma interior de esa vida creadora llamémosla cultura, poseer cultura, crear cultura, padecer por la cultura. Las creaciones del hombre son expresión de esa existencia, en forma personal."[xv]

El hombre es artífice de su táctica vital [Der Mensch ist der Schöpfer seiner Lebenstaktik geworden]. Esta palabra, "táctica", es crucial para comprender la gran analogía belicista que recorre por igual la filosofía de la naturaleza y la filosofía de la historia spenglerianas. De esa creación libre brota, no obstante, un plano nuevo de coacción y de condena sobre los aprendices de brujo que son los humanos. El Espíritu Objetivo podrá verse, hegelianamente, como un fruto de la libertad esencial de los hombres, pero, a la par, se alza como envoltorio determinante y coactivo que canaliza y bloquea los cursos en principio libres de los sujetos. Es una libertad que se auto-restringe al devenir objetivo. La cultura no es ya, sin más, el Reino de la Libertad confrontado al Reino de la Necesidad (material y físico-química). La optimista dualidad kantiana, como en general la optimista y felicitaría dualidad teológico-cristiana de la que partía, ya ha quedado atrás. De la cultura también procede un destino, una fatalidad [Verhängnis].

El hombre es artífice de su táctica vital [Der Mensch ist der Schöpfer seiner Lebenstaktik geworden]. Esta palabra, "táctica", es crucial para comprender la gran analogía belicista que recorre por igual la filosofía de la naturaleza y la filosofía de la historia spenglerianas. De esa creación libre brota, no obstante, un plano nuevo de coacción y de condena sobre los aprendices de brujo que son los humanos. El Espíritu Objetivo podrá verse, hegelianamente, como un fruto de la libertad esencial de los hombres, pero, a la par, se alza como envoltorio determinante y coactivo que canaliza y bloquea los cursos en principio libres de los sujetos. Es una libertad que se auto-restringe al devenir objetivo. La cultura no es ya, sin más, el Reino de la Libertad confrontado al Reino de la Necesidad (material y físico-química). La optimista dualidad kantiana, como en general la optimista y felicitaría dualidad teológico-cristiana de la que partía, ya ha quedado atrás. De la cultura también procede un destino, una fatalidad [Verhängnis].

- El hombre se ha hecho hombre por la mano.

Del carnívoro y depredador, cuyo órgano señorial es el ojo, pasamos al animal de la técnica en el sentido propio y formal, el animal que domina por medio de sus manos. Ese animal es ya el hombre. Dice Spengler que "el hombre se ha hecho hombre por la mano" [Durch die Entstehung der Hand.][xvi].

El ojo y la mano se complementan en lo que respecta a la dominación del mundo-entorno. El ojo domina desde el punto de vista teórico, y la mano desde el punto de vista práctico, nos dice el autor de El Hombre y la Técnica. El relato que nuestro filósofo nos brinda respecto a la aparición de la mano es de todo punto inaceptable. En el texto que comentamos se habla de una aparición repentina. A Spengler no se le pasa por la cabeza, al menos en relación con éste tema, la existencia de una causalidad circular alternativa a la "aparición súbita". La mano, junto con la marcha erguida, la técnica, la posición de la cabeza, etc. son novedades ellas que se podrían explicar de forma evolucionista pero no necesariamente en términos de sucesión lenta y gradual. En la antropología evolucionista se pueden establecer modelos de realimentación causal en donde las novedades "empujan" a otras, ofreciendo ventajas sinérgicas en cuanto a adaptación. Así parece haber sido el proceso de hominización, ciertamente un proceso acelerado, en donde el ritmo del cambio se hace vertiginoso. El papel de la mano en ese conjunto de procesos sinérgicos parece haber sido determinante. En esta misma revista hemos dado noticia de las investigaciones del profesor Manuel Fernández Lorenzo en ese sentido.[xvii]

Por el contrario, los prejuicios anti-evolucionistas de Spengler, y su apuesta por el mutacionismo de Hugo de Vries, hoy tan desacreditado, lastran la genial intuición. La mano hizo al hombre: he aquí una proposición que damos como cierta siempre y cuando no se oscurezcan las otras novedades bioculturales que, en sinergia con la conversión de la garra en mano, nos diferenciaron de manera muy notable dentro del grupo de los primates. Lo que Spengler ve como simultaneidad, nosotros deberíamos hoy analizarlo (con los enormes datos disponibles hoy por la paleoantropología, inexistentes en la época en que nuestro filósofo vivió) en términos de causalidad circular y sinérgica. De hecho, en el siguiente párrafo se podría vislumbrar este enfoque sustituyendo la simultaneidad repentina por este tipo de causalidad:

Aber nicht nur müssen Hand, Gang und Haltung des Menschen gleichzeitig entstanden sein, sondern auch – und das hat bis jetzt niemand bemerkt – Hand und Werkzeug. Die unbewaffnete Hand für sich allein ist nichts wert. Sie fordert die Waffe, um selbst Waffe zu sein. Wie sichdas Werkzeug aus der Gestalt der Hand gebildet hat, so umgekehrt die Hand an der Gestalt des Werkzeugs. Es ist sinnlos, das zeitlich trennen zu wollen. Es ist unmöglich, daß die ausgebildete Hand auch nur kurze Zeit hindurch ohne Werkzeug tätig war. Die frühesten Reste des Menschen und seiner Geräte sind gleich alt.

"Pero no sólo la mano, la marcha y la actitud del hombre debieron surgir a la vez, sino también — y esto es lo que nadie ha observado hasta hoy — la mano y la herramienta. La mano inerme no tiene valor por sí sola. La mano exige el arma, para ser ella misma arma. Así como la herramienta se ha formado por la figura de la mano, así inversamente la mano se ha hecho sobre la figura de la herramienta. Es absurdo pretender separarlas en el tiempo. Es imposible que la mano ya formada haya actuado ni aun por poco tiempo sin herramienta. Los más antiguos restos humanos y las más antiguas herramientas tienen la misma edad." [xviii]

La forma o figura [Gestalt] de la mano determina la de la herramienta, y viceversa. La garra no precisa de herramientas. Cuando la garra del simio comienza a tomar palos y emplearlos, inicial y esencialmente como armas, ésta garra ya deviene mano. Y en este momento ya nace un nuevo tipo de depredador: no es sólo el depredador de los ojos, con un pensamiento ocular, sino un pensar de la mano. Ojo y manos, en el plano sensomotor, representan por analogía la doble faceta del pensar humano, el plano cognoscitivo: el pensar intelectual (relaciones causa-efecto) y el pensar práctico (relaciones medio-fin).

La forma o figura [Gestalt] de la mano determina la de la herramienta, y viceversa. La garra no precisa de herramientas. Cuando la garra del simio comienza a tomar palos y emplearlos, inicial y esencialmente como armas, ésta garra ya deviene mano. Y en este momento ya nace un nuevo tipo de depredador: no es sólo el depredador de los ojos, con un pensamiento ocular, sino un pensar de la mano. Ojo y manos, en el plano sensomotor, representan por analogía la doble faceta del pensar humano, el plano cognoscitivo: el pensar intelectual (relaciones causa-efecto) y el pensar práctico (relaciones medio-fin).

- Intelecto y Praxis.

Ambas formas de pensamiento representan una liberación frente al "pensar de la especie" de los demás animales. En el pensar de la especie no hay individuación. La especie "piensa" por el individuo y ese pensar es acción instintiva. En cambio, en el hombre el pensar es acción personal y creativa. Y desde la lejana prehistoria parece prepararse una doble clase o condición en el ser de los hombres: el hombre teórico (sacerdote, científico y filósofo) que busca y atesora verdades, y el hombre fáctico, el de los hechos (negociante, general, estadista)[xix].

Esta distinción presenta un carácter universal, pues entrecruza las más diversas culturas y civilizaciones. En todas ellas hay la suficiente diversidad humana como para que uno pueda nacer en el grupo "contemplativo" o en el "fáctico" y desarrollarse cada individuo según ese particular destino. De todas las maneras da la impresión de que las civilizaciones, esto es, las culturas rígidas que ya han iniciado su inexorable declive, propenden a extender y encumbrar un tipo de hombre contemplativo progresivamente ciego y sordo ante los hechos, y tienden igualmente a favorecer modos de vida poco realistas, poco pragmáticos e incluso modos de vida claramente contrarios a la adaptación y al más básico instinto de supervivencia. Modos de vida en los cuales se extienden los sabios "que huyen del mundo" y de otros muchos papanatas que les imitan, mientras a las puertas de sus ciudades o en el limes cada vez peor defendido, aguardan los bárbaros, sedientos de sangre, hambrientos de riquezas o simplemente hambrientos. Y en ese momento crucial del declive de una civilización, cuando los sabios huyen del mundo, vale decir simplemente que "huyen", y ya no hay hombres de hechos que sepan afrontarse con el abismo, se puede decir que todo está perdido. La sabiduría del ojo, que inicialmente fue la sagacidad y claridad del animal de presa, no se ha visto debidamente potenciada por la astucia de la mano, la del animal de acción, facta et non verba.

Nuestro filósofo remonta la tecnicidad hasta los estratos más básicos de la vida, y sólo en la animalidad superior, depredadora, encuentra la verdadera base sensomotora para la técnica –el ojo y la mano. Sin embargo no cifra en esta base la aparición del "arte". El "arte" es enfrentamiento con la naturaleza. Ya no es sólo la lucha contra el animal (caza) y contra el semejante (guerra), es la guerra contra la naturaleza. Es una guerra que se alza cuando la propia cultura objetiva extiende su capa sobre la historia de los hombres, y los hombres se desdoblan en teóricos y prácticos, y aun la propia práctica se desdobla en la praxis constructiva y en la praxis ejecutiva (como dice Spengler, hay quien sabe fabricar un violín y hay quien sabe tocarlo). Lo mismo hemos de ver con las armas: quienes las inventaron, quienes desarrollaron las bases científico-tecnológicas para su existencia –la cultura occidental- pueden ser hoy las víctimas de sus propios ingenios. A la tecnicidad le sucede lo mismo que al pensamiento entero. Los sabios que huyen del mundo se exponen a encontrarse con masas de bárbaros dispuestos a violar todo su saber, a rebanarles el cuello y a incendiar sus bibliotecas y laboratorios. La tecnicidad es el comienzo mismo de la divergencia entre naturaleza e historia, es el punto en que comienza la tragedia esencial de los hombres. Y las culturas que, como la europea, más han logrado domeñar la naturaleza, acaso por su falta de benignidad climática, más habrán de sufrir la venganza de ésta naturaleza. La cultura europea y su extensión, la civilización occidental, ha creado todo el arsenal con el cual se puede liquidar el mundo. Pero este arsenal no es poseído por un Imperio que lo administre, que sea el prudente ejecutor de los actos de defensa común de los valores civilizatorios. No. Este arsenal se ha "difundido". Culturas y potencias por completo ajenas a Europa y a sus valores se han apropiado de la técnica –y muy especialmente de la técnica destructiva- para sojuzgar Europa, y destruir, en el límite, el mundo mismo.

- El lenguaje. La concepción operatoria según Spengler.

Formando parte de la tecnicidad está el lenguaje mismo. Y Spengler se apresura a deslindar su concepción operatoria del lenguaje frente a otras muy usuales como son la romántica y la racionalista. La concepción romántica se fija sólo en el aspecto expresivo, el origen del habla está en la función poética y mitológica. En el otro extremo, la concepción racionalista considera que el lenguaje es un sistema de proposiciones. Las palabras son meros vehículos que transmiten pensamientos. Por el contrario, la concepción operatoria del lenguaje que en breves pinceladas (pues eso son, nada más, unas breves pinceladas) nos ofrece Spengler es dialógica. El lenguaje existe para comunicarse dos o más individuos, y no para expresarse o para meditar aisladamente. En lugar de un enfoque monológico, hay que hablar aquí de un enfoque dialógico. El lenguaje, y con él la operatoriedad que lleva implícita consta de preguntas y respuestas, mandatos, instrucciones, apremios. El lenguaje primitivo era extraordinariamente parco y conciso. Por eso dice Spengler que antaño, acaso en la Prehistoria, sólo se hablaba lo estrictamente necesario y que aún hoy los aldeanos son personas muy silenciosas. Y por supuesto, el medio ambiente y el alma de cada pueblo exige un "medio" lingüístico completamente distinto, pues diversas son las necesidades (pueblo de cazadores, pueblo de pastores, labradores, nómadas…).[xx] La base del lenguaje es completamente práctica-operatoria. En este sentido, las ideas lingüísticas de de Spengler son muy cercanas a las del materialismo filosófico de Gustavo Bueno o, más aún, a las ideas de la Operatiología de Manuel Fernández Lorenzo. Al igual que éste último, Spengler dice explícitamente que el hombre "piensa con la mano":

Der ursprüngliche Zweck des Sprechens ist die Durchführung einer Tat nach Absicht, Zeit, Ort, Mitteln. Die klare, eindeutige Fassung derselben ist das Erste, und aus der Schwierigkeit, sich verständlich zu machen, den eigenen Willen anderen aufzuerlegen, ergibt sich die Technik derGrammatik, die Technik der Bildung von Sätzen und Satzarten, des richtigen Befehlens, Fragens, Antwortens, der Ausbildung von Wortklassen auf Grund der praktischen, nicht der theoretischen Absichten und Ziele. Das theoretische Nachdenken hat am Entstehen des Sprechens in Sätzen so gut wie gar keinen Anteil. Alles Sprechen ist praktischer Natur und geht vom »Denken der Hand« aus.

Der ursprüngliche Zweck des Sprechens ist die Durchführung einer Tat nach Absicht, Zeit, Ort, Mitteln. Die klare, eindeutige Fassung derselben ist das Erste, und aus der Schwierigkeit, sich verständlich zu machen, den eigenen Willen anderen aufzuerlegen, ergibt sich die Technik derGrammatik, die Technik der Bildung von Sätzen und Satzarten, des richtigen Befehlens, Fragens, Antwortens, der Ausbildung von Wortklassen auf Grund der praktischen, nicht der theoretischen Absichten und Ziele. Das theoretische Nachdenken hat am Entstehen des Sprechens in Sätzen so gut wie gar keinen Anteil. Alles Sprechen ist praktischer Natur und geht vom »Denken der Hand« aus.

"La finalidad primitiva del lenguaje es la ejecución de un acto, según propósito, tiempo, lugar y medios. La concepción clara e inequívoca del acto es lo primero; y la dificultad de hacerse comprender, de imponer a los demás la propia voluntad, produce la técnica de la gramática, la técnica de la formación de oraciones y cláusulas, la técnica del correcto mandato, de la interrogación, de la respuesta, de la formación de las palabras generales, sobre la base de los fines y propósitos prácticos, no de los teóricos. La meditación teorética no tiene participación alguna en el origen del lenguaje oracional. Todo lenguaje es de naturaleza práctica; su base es el “pensar de la mano"". [xxi]

Para eso está el lenguaje: para realizar un acto [Durchführung einer Tat]. Hablamos de un pensamiento "ejecutivo". La propia mano ya "piensa" en el momento en que realiza sus diversas ejecuciones. La gramática es una técnica, y su existencia original, antes de asumir otras funciones, es puramente práctica. El lenguaje, incluso si está basado en lo sensible, adquiere una autonomía por razón a su entrelazamiento colectivo. De la acción de muchos surge la empresa [Das Tun zu mehreren nennen wir Unternehmen]. [xxii].

- Biopolítica jerárquica.

Se da aquí, del paso de la mano al lenguaje, una segunda clase de Espíritu Objetivo: a parte de las máquinas, objetos, artefactos y cultura material "extra-objetiva", se da una cultura estrictamente institucional, lingüística, en la cual el propio hombre individual puede quedar atrapado. En esa realidad institucional y objetivada aparecen las dos clases fundamentales de hombres: la clase de los gobernantes y la de los gobernados. Todas las sociedades "sanas" han reconocido esta diferencia, la cual se funda en la más práctica escisión entre talentos: unos talentos saben dirigir y otros saben ejecutar. En toda empresa, además del ojo que ve y de la mano que ejecuta, hay "hombres oculares" que se invisten de talento práctico en virtud de su función de mando, y "hombres manuales", que ejecutan en medio de la red normativa e institucional que implica una ejecución. Existe, a nuestro modo de ver, una antropología materialista spengleriana que va montando, en función de una jerarquía sensorial (el ojo del depredador, relegado luego al ojo del hombre teórico) y operatoria (la mano que crea y que se ve armada, relegada luego a la mano del ejecutor obediente) explica el rebasamiento del naturalismo y su superación por un plano institucional. El filósofo germano no desarrolla este proceso, y lo expone de forma demasiado apretada, aunque lo escrito por él contiene muchas enseñanzas.

Es gibt zuletzt einen natürlichen Rangunterschied zwischen Menschen, die zum Herrschen und die zum Dienen geboren sind, zwischen Führern und Geführten des Lebens. Er ist schlechthin vorhanden und wird in gesunden Zeiten und Bevölkerungen von jedermann unwillkürlich anerkannt, als Tatsache, obgleich sich in Jahrhunderten des Verfalls die meisten zwingen, das zu leugnen oder nicht zu sehen. Aber gerade das Gerede von der »natürlichen Gleichheit aller« beweist, daß es hier etwas fortzubeweisen gibt.

"Existe al fin una diferencia natural de rango entre los hombres que han nacido para mandar y los hombres que han nacido para servir, entre los dirigentes y los dirigidos de la vida. Esa diferencia de rango existe absolutamente; y en las épocas y en los pueblos sanos es reconocida involuntariamente por todo el mundo como un hecho, aun cuando en los siglos de decadencia la mayoría se esfuerce por negarla o no verla. Pero justamente ese continuo hablar de la “igualdad natural entre todos”, demuestra un esfuerzo que se encamina a probar la no existencia de esa diferenciación." [xxiii]

En la fase civilizada, no en la cultural-ascendente, se inicia un resentido movimiento de las masas, excitado por los talentos más mediocres, un movimiento encaminado hacia la nivelación. En la fase civilizada se deteriora de manera calculada la educación, se cuestiona la autoridad y se acorrala al autoritario, al capitán dotado de derecho natural al mando. Los lobos solitarios se ven rodeados de ovejas resentidas, feroces en su afán revanchista para con el depredador natural, pero mansas y obedientes ante los nuevos demagogos,

Spengler se sitúa resueltamente entre los filósofos anti-igualitarios, en la misma línea de los clásicos Platón y Aristóteles y seguida por Nietzsche. La diferencia entre los hombres es un "hecho" [Tatsache] acerca del cual cabe poca o nula discusión. La vida práctica de los individuos sólo empieza a comprenderse en el seno de una organización, cuya decadencia civilizada es "masa", pero cuya existencia "en forma" se denomina Estado. El origen del Estado estriba en esa tecnicidad devenida en forma de organización militar. En la milicia existe ya un Estado in nuce. La organización de la empresa humana, especialmente ante enemigos potenciales exteriores, es el Ejército, la institución que encarna la tecnicidad elevada al plano institucional, objetivo-espiritual: […] der Staat ist die innere Ordnung eines Volkes für den äußeren Zweck. Der Staat ist als Form, als Möglichkeit, was die Geschichte eines Volkes als Wirklichkeit ist. Geschichte aber ist Kriegsgeschichte, damals wie heute. Politik ist nur der vorübergehende Ersatz des Krieges durch den Kampf mit geistigeren Waffen. Und die Mannschaft eines Volkes ist ursprünglich gleichbedeutend mit seinem Heer. Der Charakter des freien Raubtieres ist in wesentlichen Zügen vom einzelnen auf das organisierte Volk übergegangen, das Tier mit einer Seele und vielen Händen. Regierungs-, Kriegs- und diplomatische Technik haben dieselbe Wurzel und zu allen Zeiten eine tief innerliche Verwandtschaft.

Spengler se sitúa resueltamente entre los filósofos anti-igualitarios, en la misma línea de los clásicos Platón y Aristóteles y seguida por Nietzsche. La diferencia entre los hombres es un "hecho" [Tatsache] acerca del cual cabe poca o nula discusión. La vida práctica de los individuos sólo empieza a comprenderse en el seno de una organización, cuya decadencia civilizada es "masa", pero cuya existencia "en forma" se denomina Estado. El origen del Estado estriba en esa tecnicidad devenida en forma de organización militar. En la milicia existe ya un Estado in nuce. La organización de la empresa humana, especialmente ante enemigos potenciales exteriores, es el Ejército, la institución que encarna la tecnicidad elevada al plano institucional, objetivo-espiritual: […] der Staat ist die innere Ordnung eines Volkes für den äußeren Zweck. Der Staat ist als Form, als Möglichkeit, was die Geschichte eines Volkes als Wirklichkeit ist. Geschichte aber ist Kriegsgeschichte, damals wie heute. Politik ist nur der vorübergehende Ersatz des Krieges durch den Kampf mit geistigeren Waffen. Und die Mannschaft eines Volkes ist ursprünglich gleichbedeutend mit seinem Heer. Der Charakter des freien Raubtieres ist in wesentlichen Zügen vom einzelnen auf das organisierte Volk übergegangen, das Tier mit einer Seele und vielen Händen. Regierungs-, Kriegs- und diplomatische Technik haben dieselbe Wurzel und zu allen Zeiten eine tief innerliche Verwandtschaft.

"[…] El Estado es el orden interior de un pueblo para los fines exteriores. El Estado es, como forma, como posibilidad, lo que la historia de un pueblo es como realidad. Pero la historia es historia guerrera, entonces lo mismo que hoy. La política es más simplemente el efímero sucedáneo de la guerra, mediante la lucha con armas espirituales. Y el conjunto de los hombres en un pueblo es originariamente equivalente a su ejército. El carácter del animal rapaz y libre se ha trasladado, con sus rasgos esenciales, desde el individuo al pueblo organizado, que es el animal con un alma y muchas manos. La técnica del gobernante, del guerrero y del diplomático tienen la misma raíz y, en todos los tiempos, una afinidad interna muy profunda."[xxiv]

Partiendo de un naturalismo –ciertamente anti-evolucionista- desde el cual se encuentran los elementos etológicos de la tecnicidad, Spengler emplea su método analógico a fondo con vistas a equiparar distintas clases de actividad práctica. Una vez equiparadas esas "técnicas", especialmente las técnicas humanas regentes (gobernante, guerrero, diplomático), se acude a la raíz [Wurzel] común. Este proceder spengleriano puede suscitar críticas merecidas si en él hay circularidad. La analogía lleva a la raíz, y la raíz alumbra la analogía. No habría círculo vicioso en la exposición sobre la evolución de la tecnicidad, desde la propia sensorialidad y operatoriedad etológicas hasta las instituciones humanas de una cultura superior (Estado, Ejército, etc.), si las meras analogías fueran transformadas en capas de complejidad creciente en las cuales los estratos inferiores (p.e. la depredación etológica) conservaran partes materiales que se integran en los estratos superiores (p.e. la conquista y dominación de un Estado sobre otros). El estilo fogoso, impresionista, en ocasiones poético, del filósofo alemán, parece impedir la paciente construcción de verdaderas homologías –y no analogías. De otra parte, la intencionalidad y estilo "belicista" de las palabras spenglerianas le llevan a insistir de manera muy particular en la propia guerra como eje en torno al cual girarán todas las demás indagaciones sobre la tecnicidad. Había tecnicidad en el ojo del cazador. Había tecnicidad en la mano armada del homínido. Había tecnicidad en la dirección de hombres armados en cooperación. Hay tecnicidad en cualquier "empresa", esto es, en cualquier cooperación que lleva a una masa organizada en la que se dan relaciones de poder (dominantes-dominados) hacia fuera y hacia dentro, etc.…Creemos no haber expuesto de forma caricaturesca la manera en que un pensamiento jerárquico y "belicista" como el de Spengler consigue reducir la tecnicidad a la lucha y la dominación. Pero se da la circunstancia de que esa lucha y ese afán de dominación (Voluntad de Poder), iniciada contra animales de otras especies y proseguida contra otros grupos de individuos de la propia especie humana crea todo un mundo artefactual, un Espíritu Objetivo que, por medio del lenguaje y de las instituciones y no sólo de armas y herramientas productivas, encierra al animal humano en su propia jaula. El hombre se encarcela: la casa y la ciudad, símbolos supremos de la Cultura, encarnan perfectamente la nueva clase de servidumbre universal de los humanos. Así, Spengler nos presenta la historia de los hombres a largo plazo, una lucha por capturar animales y hombres, una conflagración universal en pos de evitar ser esclavizado o lograr esclavizar a otros. Pero este panorama no puede conducir sino a otro, en el cual la esclavitud de una parte frente a otra parte de los hombres conduce a la esclavitud universal. Todos, con independencia de su posición económica, política, militar, todos sin excepción son esclavos de una cárcel "cultural".

In dieser wachsenden gegenseitigen Abhängigkeit liegt die stille und tiefe Rache der Natur an dem Wesen, das ihr das Vorrecht auf Schöpfertum entriß. Dieser kleine Schöpfer wider die Natur, dieser Revolutionär in der Welt des Lebens ist der Sklave seiner Schöpfung geworden. Die Kultur, der Inbegriff künstlicher, persönlicher, selbstgeschaffener Lebensformen, entwickelt sich zu einem Käfig mit engen Gittern für diese unbändige Seele. Das Raubtier, das andere Wesen zu Haustieren machte, um sie für sich auszubeuten, hat sich selbst gefangen. Das Haus des Menschen ist das große Symbol dafür.

"En esta creciente dependencia mutua reside la muda y profunda venganza de la naturaleza sobre el ser que supo arrebatarle el privilegio de la creación. Ese pequeño creador contra natura, ese revolucionario en el mundo de la vida, conviértese en el esclavo de su propia creación. La cultura, el conjunto de las formas artificiales, personales, propias de la vida, desarróllase en jaula de estrechas rejas para aquella alma indomable. El animal de rapiña, que convirtió a los otros seres en animales domésticos, para explotarlos en su propio provecho, hace aprisionado a sí mismo. La casa del hombre es el símbolo magno de este hecho." [xxv]

El hombre se vuelve un esclavo de su propia creación [der Sklave seiner Schöpfung geworden]. Con estas breves palabras se podría resumir todo el recorrido de la metafísica alemana desde Kant. Partiendo del idealismo clásico germano y del pensamiento romántico, regresa en Spengler el tópico del hombre como ser enfrentado metafísicamente al objeto. Si el Reino de la Libertad se llama ahora, Reino de la Cultura y éste fue entendido, bajo el humanismo idealista y romántico, como una liberación de la necesidad (naturaleza), ahora, en las postrimerías del siglo XIX corresponde a la fase "vitalista" de la metafísica germana entender la propia Cultura no como libertad sino a modo de jaula y prisión. En la medida en que el hombre ya no es Razón o Espíritu, sino un "animal depredador" [Das Raubtier], la Cultura es la cárcel que le retiene. Se ha completado el ciclo del "aprendiz de brujo". Nuestra especie pretende escapar de la naturaleza y ésta, en su lado más salvaje, sigue presente incluso habiéndose recluido en una fortaleza cultural. Dentro del recinto carcelario va creciendo la base de los subordinados. La clase dirigente, la cúpula de los depredadores, necesita cada vez más manos controladas por menos ojos. Las manos de las masas ejecutoras –esclavos, siervos, asalariados- se ven desprovistas de su consustancial inteligencia. La pre-visión, la planificación dirigente es suficiente para conducir los trabajos y las empresas. Es evidente que en tiempos de decadencia hay una rebelión de las masas. Se extiende el igualitarismo, esto es, la envidia. En la más pura línea nietzscheana, Spengler, como nuestro Ortega, vincula el triunfo de la oclocracia (el poder de la chusma) a un sentimiento exacerbado de envidia y fobia al talento. Esta rebelión de las masas no puede acaecer sino después de todo un ciclo que no dudamos en calificar sino de dialéctico. Es dialéctico puesto que incluye negaciones, rebasamientos de fases anteriores. Sin embargo es dialéctico pero no al modo hegeliano. No hay en Spengler una Teología optimista. En Hegel el dolor y el error quedaban sobradamente justificados en el largo plazo, en la consumación final, siempre victoriosa. En Spengler, en cambio, el dolor y el error no se justifican, son subproductos –al modo schopenhaueriano- que tan sólo para los sujetos pacientes y los sentimentales, poseen alguna relevancia. La dialéctica spengleriana es la de un naturalismo crudo. Es un sistema de negaciones y de rebasamientos de estratos previos, no necesariamente encaminados hacia "lo mejor". El tránsito de la Cultura hacia la Civilización no es, precisamente, el tránsito hacia capas superiores. En la propia Civilización hay recaídas en la barbarie, en el salvajismo y en la propia animalidad. Así han de contemplarse las perversiones de todas las grandes ciudades de todas las épocas civilizatorias en fase senil o terminal, infestadas de "proletarios" y desarraigados. En ellas regresa la selva y la propia animalidad, y las perversiones del hombre decadente de la ciudad son las propias de un animalismo elevado de potencia, el animalismo del frío animal post-racional encerrado en el cemento y el asfalto. La naturaleza siempre se venga: "…die stille und tiefe Rache der Natur an dem Wesen, das ihr das Vorrecht auf Schöpfertum entriß. ["…la muda y profunda venganza de la naturaleza sobre el ser que supo arrebatarle el privilegio de la creación"]. Prometeo ha robado el fuego a los dioses, y debe pagar por ello. La bestia alada que le roe sin cesar las entrañas bien puede simbolizar el retorno de "lo peor", el avance de la selva entre las selvas de asfalto de aquel que un día se autoerigió como Rey de la Creación.

- Conclusiones: Tecnicidad y decadencia.

La decadencia de Occidente se ilumina plenamente mirando esta civilización bajo el aspecto de la técnica. La técnica, nacida en toda cultura humana básicamente como arma y como potenciación del ojo y la mano depredadora, ya en fase mecanista pasa a ser la tumba de la civilización que con más energía y saña la desarrolló, la civilización europea de Occidente. Otros pueblos se beneficiarán de aquellos logros de la cultura fáustica. Los frailes escolásticos europeos, en torno a los siglos XII y XIII introdujeron el verdadero Renacimiento[xxvi]. Spengler no duda en llamarlos "vikingos del espíritu". Sin miedo a navegar todo lo lejos posible, y con el mismo afán dominador de sus antecedentes piráticos y navegantes, fueron aquellos escolásticos de la cultura fáustica quienes sentaron las bases de la ciencia moderna, mucho tiempo antes de Galileo, Copérnico, Descartes o Newton. Un Mundo y un Dios entendidos en términos de fuerza, energía, y una naturaleza entendida como botín y campo para la conquista. Los vikingos del espíritu, los escolásticos medievales, impulsaron el verdadero Renacimiento y la primera fase científico-técnica de la cultura fáustica. Ellos prepararon el terreno para la segunda oleada de descubrimientos, y con los descubrimientos, las conquistas. Los conquistadores españoles fueron, a ojos de Spengler, los nuevos vikingos, los herederos de la "sangre nórdica", destinados a revolucionar el mundo, como hicieran, unos siglos antes, sus antepasados.

La decadencia de Occidente se ilumina plenamente mirando esta civilización bajo el aspecto de la técnica. La técnica, nacida en toda cultura humana básicamente como arma y como potenciación del ojo y la mano depredadora, ya en fase mecanista pasa a ser la tumba de la civilización que con más energía y saña la desarrolló, la civilización europea de Occidente. Otros pueblos se beneficiarán de aquellos logros de la cultura fáustica. Los frailes escolásticos europeos, en torno a los siglos XII y XIII introdujeron el verdadero Renacimiento[xxvi]. Spengler no duda en llamarlos "vikingos del espíritu". Sin miedo a navegar todo lo lejos posible, y con el mismo afán dominador de sus antecedentes piráticos y navegantes, fueron aquellos escolásticos de la cultura fáustica quienes sentaron las bases de la ciencia moderna, mucho tiempo antes de Galileo, Copérnico, Descartes o Newton. Un Mundo y un Dios entendidos en términos de fuerza, energía, y una naturaleza entendida como botín y campo para la conquista. Los vikingos del espíritu, los escolásticos medievales, impulsaron el verdadero Renacimiento y la primera fase científico-técnica de la cultura fáustica. Ellos prepararon el terreno para la segunda oleada de descubrimientos, y con los descubrimientos, las conquistas. Los conquistadores españoles fueron, a ojos de Spengler, los nuevos vikingos, los herederos de la "sangre nórdica", destinados a revolucionar el mundo, como hicieran, unos siglos antes, sus antepasados.

Esa conexión entre piratería, depredación y conquista de la naturaleza, es señalada con toda su intensidad en la parte final del ensayo que comentamos. La conexión es posible precisamente por sobrevolar el aspecto racional. Spengler sobrevuela la diferencia entre la ciencia, una empresa racional de "conquista", y las exploraciones piráticas, guerreras, etc. de los pueblos europeos de todas las épocas, especialmente a partir de la emergencia de la cultura fáustica. La desconsideración hacia la razón, o el verla precisamente como una parte más de las cualidades depredadoras de esta clase de hombres que el autor llama "hombres de las comarcas del Norte", se inscribe en su teoría sobre las dos clases de hombres en general: hombres de hechos y hombres de verdades. En todas las razas humanas existen estas dos clases de individuos pero es la cultura la que otorga predominio o equilibrio diferenciado a una de ellas. En la historia específica de Occidente sucedió que no fue la clase sacerdotal (al estilo judaico) la que se impuso, pese a toda la fuerza de sus pretensiones. Las luchas entre el Papado y el Imperio, entre güelfos y gibelinos, son un aspecto de esta lucha entre hombres de verdades y hombres de hechos, a pesar del entrecruzamiento de tipos, y a pesar de que la propia Iglesia se sobrepuso a príncipes y guerreros porque en ella no faltaron clérigos que eran, netamente, verdaderos hombres de hechos. En la actualidad los estados sucumben ante demagogos, filisteos y supuestos "hombres de verdades".

Son hoy los estados inmersos en la ideología y en la palabrería, la clase de estados que existen en su condición de meras piezas al servicio del capital. El hombre occidental del siglo XXI es, en gran medida, un hombre post-técnico. Depende de la máquina, y su vida se encuentra progresivamente automatizada. Siendo un robot de carne y hueso, desprecia la técnica y ensaya el escapismo. Ese escapismo "contracultural" ya existía en la Europa de hace casi un siglo, en el mundo occidental en que se fraguó esta obrita, El Hombre y la Técnica[xxvii]. El orientalismo, el espiritismo, el neo-nomadismo y la mentalidad suicida y nihilista [xxviii]. El demiurgo que hizo posible la Gran Técnica, y por ende, la técnica de dominación, control y sometimiento sobre todas las demás razas y pueblos, ahora es esclavo de ella y se abandona a sí mismo. Ese demiurgo, el hombre europeo, fracasa, entierra sus armas, se deja invadir y comprar. Lo vemos hoy, con la civilización del petróleo. Sus autos y sus chimeneas reclaman sin cesar ese oro negro, a la vez que parlotean todos sin cesar sobre "energías alternativas" y "desarrollo sostenible". Mientras se sucede tanta charla y tantas cortinas de humo se levantan sobre la corteza terrestre, países productores de combustible compran voluntades y esclavizan naciones "blancas" enteras. De rodillas, como un perro amaestrado, el europeo lame las botas de quien posee los petrodólares.

[i] Blanco Martín (2014): "Una antropología de la Técnica. Consideraciones spenglerianas" La Razón Histórica, nº27, 2014 [117-130]. ISSN 1989-2659 [https://www.revistalarazonhistorica.com/27-8/]

[ii] La edición española que tenemos a la vista, y cuya paginación empleamos es la correspondiente al volumen editado por Ediciones Fides: Oswald Spengler, Regeneración del Imperio Alemán. El hombre y la Técnica, Torredembarra (Tarragona), 2016. En dicha edición no figura traductor pero el texto español coincide con la traducción de Manuel García Morente aparecida en la editorial Espasa Calpe, Madrid, 1934. Las citas correspondientes del original en alemán, cuya paginación no aportamos, están tomadas del siguiente sitio web :http://www.zeno.org/nid/20009270388, que reproduce la siguiente edición

Oswald Spengler: Der Mensch und die Technik. München 1931. Erstdruck: München: Beck, 1931.

[iii] Fruto de nuestras investigaciones ya ha salido un libro: Blanco Martín (2016): Oswald Spengler y la Europa Fáustica, Ediciones Fides, (Tarragona), con prólogo de Alain de Benoist; volumen que recoge diversos artículos aparecidos con anterioridad, más numerosas publicaciones en papel o en internet. Alguna de esas publicaciones están recogidas en el listado de la Oswald Spengler Society for the Study of Humanity and World Society.

https://www.oswaldspenglersociety.com/sources

[iv] El Hombre y la Técnica, a partir de ahora, según la edición citada: HT, p. 95.

[v] HT, p. 96.

[vi] HT, p. 97.

[vii] HT, p. 100.

[viii] HT, p. 100.

[ix] HT, p. 101.

[x] íbidem

[xi] HT, pps., 102-103.

[xii] HT, p. 103.

[xiii] HT, P. 105.

[xiv] HT, p. 106.

[xv] íbidem.

[xvi] HT, p. 107.

[xvii] Blanco Martín (2017): El pensamiento “a mano”. En torno al “Pensamiento Hábil”. Reseña de dos libros de Manuel Fernández Lorenzo y su contraste con el Materialismo Filosófico , Revista La Razón Histórica, Número 35, Año 2017, páginas 20-35 [https://www.revistalarazonhistorica.com/35-2/]

[xviii] HT, p. 108.

[xix] HT, p. 110.

[xx] HT, pps. 115-116.

[xxi] HT, P. 116

[xxii] ibídem.

[xxiii] HT, p. 120.

[xxiv] HT, p. 121.

[xxv] HT, p. 122.

[xxvi] HT, pps. 128-129.

[xxvii] Esta obra fue publicada por primera vez en 1931. Véase nota 1.

[xxviii] HT, p. 136.

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

En un trabajo anterior ya quisimos hacer una aproximación antropológica al concepto spengleriano de la Técnica[i] . El presente trabajo quiere ser una prolongación del mismo, profundizando en los conceptos spenglerianos sobre la tecnicidad y lo hacemos por medio de un comentario detenido de las páginas de su pequeña obra El Hombre y la Técnica.[ii] Este breve texto spengleriano aclara muchos aspectos de la filosofía, poco sistemática y, a veces, impresionista, del gran pensador alemán, el creador de la magna obra La Decadencia de Occidente. Este breve libro traza un cuadro evolutivo de la técnica en la historia natural y cultural del hombre. Pero hace algo más: esboza de una manera dialéctica el destino fatal de los pueblos de Occidente, pueblos que han desarrollado toda su tecnicidad hasta ponerla en manos de sus enemigos. Este examen detenido de los párrafos enérgicos y vibrantes del librito puede ayudar a comprender la peculiar dialéctica pesimista –a diferencia de la optimista hegeliana- del pensador alemán Oswald Spengler. En vez de alcanzar un progresivo dominio técnico del mundo, encaminado a su mayor comodidad y salud, el hombre y sus antepasados simplemente han ido diferenciando cualidades sensitivo-etológicas desde hace millones de años, cualidades en las que ya está presente la tecnicidad, aun cuando todavía nuestros antepasados no era capaces de fabricar herramientas, o sólo empleaban órganos y partes sensomotoras de su cuerpo para ejercer su dominio. Por ello, en nuestro comentario empleamos el término tecnicidad, contrapuesto a "técnica" para hacer referencia a esas capacidades generales implícitas a la hora de ejercer dominio, control o alteración del propio medio envolvente, con independencia de la existencia de herramientas, armas u otros objetos extra-somáticos. La tecnicidad es la cualidad o el carácter técnico de algo o alguien, y no se debe circunscribir a los productos de las artes humanas o proto-humanas ni al aspecto normativo o envolvente del Espíritu Objetivo. Nuestro comentario, pues, se enmarca en el espacio antropológico. Queremos ahondar en la antropología spengleriana, tal y como llevamos haciendo desde hace unos años. [iii]

En un trabajo anterior ya quisimos hacer una aproximación antropológica al concepto spengleriano de la Técnica[i] . El presente trabajo quiere ser una prolongación del mismo, profundizando en los conceptos spenglerianos sobre la tecnicidad y lo hacemos por medio de un comentario detenido de las páginas de su pequeña obra El Hombre y la Técnica.[ii] Este breve texto spengleriano aclara muchos aspectos de la filosofía, poco sistemática y, a veces, impresionista, del gran pensador alemán, el creador de la magna obra La Decadencia de Occidente. Este breve libro traza un cuadro evolutivo de la técnica en la historia natural y cultural del hombre. Pero hace algo más: esboza de una manera dialéctica el destino fatal de los pueblos de Occidente, pueblos que han desarrollado toda su tecnicidad hasta ponerla en manos de sus enemigos. Este examen detenido de los párrafos enérgicos y vibrantes del librito puede ayudar a comprender la peculiar dialéctica pesimista –a diferencia de la optimista hegeliana- del pensador alemán Oswald Spengler. En vez de alcanzar un progresivo dominio técnico del mundo, encaminado a su mayor comodidad y salud, el hombre y sus antepasados simplemente han ido diferenciando cualidades sensitivo-etológicas desde hace millones de años, cualidades en las que ya está presente la tecnicidad, aun cuando todavía nuestros antepasados no era capaces de fabricar herramientas, o sólo empleaban órganos y partes sensomotoras de su cuerpo para ejercer su dominio. Por ello, en nuestro comentario empleamos el término tecnicidad, contrapuesto a "técnica" para hacer referencia a esas capacidades generales implícitas a la hora de ejercer dominio, control o alteración del propio medio envolvente, con independencia de la existencia de herramientas, armas u otros objetos extra-somáticos. La tecnicidad es la cualidad o el carácter técnico de algo o alguien, y no se debe circunscribir a los productos de las artes humanas o proto-humanas ni al aspecto normativo o envolvente del Espíritu Objetivo. Nuestro comentario, pues, se enmarca en el espacio antropológico. Queremos ahondar en la antropología spengleriana, tal y como llevamos haciendo desde hace unos años. [iii]

Das ist der andre Fehler, der hier vermieden werden muß: Technik ist nicht vom Werkzeug her zu verstehen. Es kommt nicht auf die Herstellung von Dingen an, sondern auf das Verfahren mit ihnen, nicht auf die Waffe, sondern auf den Kampf

Das ist der andre Fehler, der hier vermieden werden muß: Technik ist nicht vom Werkzeug her zu verstehen. Es kommt nicht auf die Herstellung von Dingen an, sondern auf das Verfahren mit ihnen, nicht auf die Waffe, sondern auf den Kampf "La planta vive; aunque sólo en sentido limitado, es un ser viviente. En realidad, más que vivir puede decirse que en ella y en torno a ella está la vida. “Ella” respira, “ella” se alimenta, “ella” se multiplica; y, sin embargo, no es propiamente más que el escenario de esos procesos, que constituyen una unidad con los procesos de la naturaleza circundante, con el día y la noche, con los rayos del sol y la fermentación del suelo; de suerte que la planta misma no puede ni querer ni elegir. Todo acontece con ella y en ella. Ella no busca ni su lugar propio, ni su alimento, ni las demás plantas con quienes engendra su sucesión. No se mueve, sino que son el viento, el calor, la luz, quienes la mueven." [x]

"La planta vive; aunque sólo en sentido limitado, es un ser viviente. En realidad, más que vivir puede decirse que en ella y en torno a ella está la vida. “Ella” respira, “ella” se alimenta, “ella” se multiplica; y, sin embargo, no es propiamente más que el escenario de esos procesos, que constituyen una unidad con los procesos de la naturaleza circundante, con el día y la noche, con los rayos del sol y la fermentación del suelo; de suerte que la planta misma no puede ni querer ni elegir. Todo acontece con ella y en ella. Ella no busca ni su lugar propio, ni su alimento, ni las demás plantas con quienes engendra su sucesión. No se mueve, sino que son el viento, el calor, la luz, quienes la mueven." [x] Esa mirada poderosa, unida a ese sentimiento de poder, es el germen de la Historia. Y la Historia se individualiza. No se trata de una historia de las masas. Las masas no poseen la historia. Antes de alzarse culturas individualizadas, en la fase zoológica y pre-cultural, la Historia la hacen los individuos. El animal de presa destaca y se recorta ante el animal de rebaño. El herbívoro precisa de muchos como él, y entre ellos (como luego, en las sociedades de masas) una muchedumbre de iguales constituye ya el individuo. Ha de verse aquí, en El Hombre y la Técnica, no una teoría, en el sentido riguroso o científico, sino una analogía. Spengler discurre por analogías, y esas analogías presiden toda su filosofía de la historia. Si una Cultura es, toda ella, un ser vivo dotado de su morfología propia y de su propio ciclo vital, un herbívoro es un análogo de un "hombre masa". El hombre masa del siglo XIX y XX es un retroceso hacia la animalización, pero hacia la animalización del escalón inferior, la de la presa, la del cobarde herbívoro.

Esa mirada poderosa, unida a ese sentimiento de poder, es el germen de la Historia. Y la Historia se individualiza. No se trata de una historia de las masas. Las masas no poseen la historia. Antes de alzarse culturas individualizadas, en la fase zoológica y pre-cultural, la Historia la hacen los individuos. El animal de presa destaca y se recorta ante el animal de rebaño. El herbívoro precisa de muchos como él, y entre ellos (como luego, en las sociedades de masas) una muchedumbre de iguales constituye ya el individuo. Ha de verse aquí, en El Hombre y la Técnica, no una teoría, en el sentido riguroso o científico, sino una analogía. Spengler discurre por analogías, y esas analogías presiden toda su filosofía de la historia. Si una Cultura es, toda ella, un ser vivo dotado de su morfología propia y de su propio ciclo vital, un herbívoro es un análogo de un "hombre masa". El hombre masa del siglo XIX y XX es un retroceso hacia la animalización, pero hacia la animalización del escalón inferior, la de la presa, la del cobarde herbívoro. El hombre es artífice de su táctica vital [Der Mensch ist der Schöpfer seiner Lebenstaktik geworden]. Esta palabra, "táctica", es crucial para comprender la gran analogía belicista que recorre por igual la filosofía de la naturaleza y la filosofía de la historia spenglerianas. De esa creación libre brota, no obstante, un plano nuevo de coacción y de condena sobre los aprendices de brujo que son los humanos. El Espíritu Objetivo podrá verse, hegelianamente, como un fruto de la libertad esencial de los hombres, pero, a la par, se alza como envoltorio determinante y coactivo que canaliza y bloquea los cursos en principio libres de los sujetos. Es una libertad que se auto-restringe al devenir objetivo. La cultura no es ya, sin más, el Reino de la Libertad confrontado al Reino de la Necesidad (material y físico-química). La optimista dualidad kantiana, como en general la optimista y felicitaría dualidad teológico-cristiana de la que partía, ya ha quedado atrás. De la cultura también procede un destino, una fatalidad [Verhängnis].