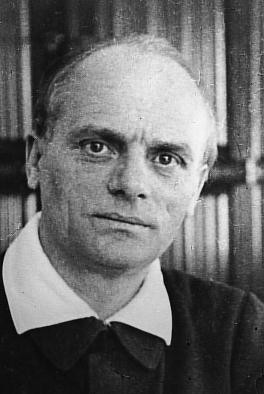

Othmar Spann was an Austrian philosopher who was a key influence on German conservative and traditionalist thought in the period after World War I, and he is thus considered a representative of the intellectual movement known as the “Conservative Revolution.” Spann was a professor of economics and sociology at the University of Vienna, where he taught not only scientific social and economic theories, but also influenced many students with the presentation of his worldview in his lectures. As a result of this he formed a large group of followers known as the Spannkreis (“Spann Circle”). This circle of intellectuals attempted to influence politicians who would be sympathetic to “Spannian” philosophy in order to actualize its goals.[1]

Othmar Spann was an Austrian philosopher who was a key influence on German conservative and traditionalist thought in the period after World War I, and he is thus considered a representative of the intellectual movement known as the “Conservative Revolution.” Spann was a professor of economics and sociology at the University of Vienna, where he taught not only scientific social and economic theories, but also influenced many students with the presentation of his worldview in his lectures. As a result of this he formed a large group of followers known as the Spannkreis (“Spann Circle”). This circle of intellectuals attempted to influence politicians who would be sympathetic to “Spannian” philosophy in order to actualize its goals.[1]

Othmar Spann himself was influenced by a variety of philosophers across history, including Plato, Aristotle, Thomas Aquinas, J. G. Fichte, Franz von Baader, and most notably the German Romantic thought of Adam Müller. Spann called his own worldview “Universalism,” a term which should not be confused with “universalism” in the vernacular sense; for the former is nationalistic and values particularity while the latter refers to cosmopolitan or non-particularist (even anti-particularist) ideas. Spann’s term is derived from the root word “universality,” which is in this case synonymous with related terms such as collectivity, totality, or whole.[2] Spann’s Universalism was expounded in a number of books, most notably in Der wahre Staat (“The True State”), and essentially taught the value of nationality, of the social whole over the individual, of religious (specifically Catholic) values over materialistic values, and advocated the model of a non-democratic, hierarchical, and corporatist state as the only truly valid political constitution.

Social Theory

Othmar Spann declared: “It is the fundamental truth of all social science . . . that not individuals are the truly real, but the whole, and that the individuals have reality and existence only so far as they are members of the whole.”[3] This concept, which is at the core of Spann’s sociology, is not a denial of the existence of the individual person, but a complete denial of individualism; individualism being that ideology which denies the existence and importance of supra-individual realities. Classical liberal theory, which was individualist, held an “atomistic” view of individuals and regarded only individuals as truly real; individuals which it believed were essentially disconnected and independent from each other. It also held that society only exists as an instrumental association as a result of a “social contract.” On the other hand, sociological studies have disproven this theory, showing that the whole (society) is never merely the sum of its parts (individuals) and that individuals naturally have psychological bonds with each other. This was Othmar Spann’s position, but he had his own unique way of formulating it.[4]

While the theory of individualism appears, superficially, to be correct to many people, an investigation into the matter shows that it is entirely fallacious. Individuals never act entirely independently because their behavior is always at least in part determined by the society in which they live, and by their organic, non-instrumental (and thus also non-contractual) bonds with other people in their society. Spann wrote, “according to this view, the individual is no longer self-determined and self-created, and is no longer based exclusively and entirely on its own egoicity.”[5] Spann conceived of the social order, of the whole, as an organic society (a community) in which all individuals belonging to it have a pre-existing spiritual unity. The individual person emerges as such from the social whole to which he was born and from which he is never really separated, and “thus the individual is that which is derivative.”[6]

Therefore, society is not merely a mechanical aggregate of fundamentally disparate individuals, but a whole, a community, which precedes its parts, the individuals. “Universalists contend that the mental or spiritual associative tie between individuals exists as an independent entity . . .”[7] However, Spann clarified that this does not mean that the individual has “no mental self-sufficiency,” but rather that he actualizes his personal being only as a member of the whole: “he is only able to form himself, is only able to build up his personality, when in close touch with others like unto himself; he can only sustain himself as a being endowed with mentality or spirituality, when he enjoys intimate and multiform communion with other beings similarly endowed.”[8] Therefore,

All spiritual reality present in the individual is only there and only comes into being as something that has been awakened . . . the spirituality that comes into being in an individual (whether directly or mediated) is always in some sense a reverberation of that which another spirit has called out to the individual. This means that human spirituality exists only in community, never in spiritual isolation. . . . We can say that individual spirituality only exists in community or better, in ‘spiritual community’ [Gezweiung]. All spiritual essence and reality exists as ‘spiritual community’ and only in ‘communal spirituality’ [Gezweitheit].[9]

It is also important to clarify that Spann’s concept of society did not conceive of society as having no other spiritual bodies within it that were separate from each other. On the contrary, he recognized the importance of the various sub-groups, referred to by him as “partial wholes,” as constituent parts and elements which are different yet related, and which are harmonized by the whole under which they exist. Therefore, the whole or the totality can be understood as the unity of individuals and “partial wholes.” To reference a symbolic image, “Totality [the Whole] is analogous to white light before it is refracted by a prism into many colors,” in which the white light is the supra-temporal totality, while the prism is cosmic time which “refracts the totality into the differentiated and individuated temporal reality.”[10]

Nationality and Racial Style

Volk (“people” or “nation”), which signifies “nationality” in the cultural and ethnic sense, is an entirely different entity and subject matter from society or the whole, but for Spann the two had an important connection. Spann was a nationalist and, defining Volk in terms of belonging to a “spiritual community” with a shared culture, believed that a social whole is under normal conditions only made up of a single ethnic type. Only when people shared the same cultural background could the deep bonds which were present in earlier societies truly exist. He thus upheld the “concept of the concrete cultural community, the idea of the nation – as contrasted with the idea of unrestricted, cosmopolitan, intercourse between individuals.”[11]

Spann advocated the separation of ethnic groups under different states and was also a supporter of pan-Germanism because he believed that the German people should unite under a single Reich. Because he also believed that the German nation was intellectually superior to all other nations (a notion which can be considered as the unfortunate result of a personal bias), Spann also believed that Germans had a duty to lead Europe out of the crisis of liberal modernity and to a healthier order similar to that which had existed in the Middle Ages.[12]

Concerning the issue of race, Spann attempted to formulate a view of race which was in accordance with the Christian conception of the human being, which took into account not only his biology but also his psychological and spiritual being. This is why Spann rejected the common conception of race as a biological entity, for he did not believe that racial types were derived from biological inheritance, just as he did not believe an individual person’s character was set into place by heredity. Rather what race truly was for Spann was a cultural and spiritual character or type, so a person’s “racial purity” is determined not by biological purity but by how much his character and style of behavior conforms to a specific spiritual quality. In his comparison of the race theories of Spann and Ludwig Ferdinand Clauss (an influential race psychologist), Eric Voegelin had concluded:

In Spann’s race theory and in the studies of Clauss we find race as the idea of a total being: for these two scholars racial purity or blood purity is not a property of the genetic material in the biological sense, but rather the stylistic purity of the human form in all its parts, the possession of a mental stamp recognizably the same in its physical and psychological expression.[13]

However, it should be noted that while Ludwig Clauss (like Spann) did not believe that spiritual character was merely a product of genetics, he did in fact emphasize that physical race had importance because the bodily racial form must be essentially in accord with the psychical racial form with which it is associated, and with which it is always linked. As Clauss wrote,

The style of the psyche expresses itself in its arena, the animate body. But in order for this to be possible, this arena itself must be governed by a style, which in turn must stand in a structured relationship to the style of the psyche: all the features of the somatic structure are, as it were, pathways for the expression of the psyche. The racially constituted (that is, stylistically determined) psyche thus acquires a racially constituted animate body in order to express the racially constituted style of its experience in a consummate and pure manner. The psyche’s expressive style is inhibited if the style of its body does not conform perfectly with it.[14]

Likewise Julius Evola, whose thought was influenced by both Spann and Clauss, and who expanded Clauss’s race psychology to include religious matters, also affirmed that the body had a certain level of importance.[15]

On the other hand, the negative aspect of Othmar Spann’s theory of race is that it ends up dismissing the role of physical racial type entirely, and indeed many of Spann’s major works do not even mention the issue of race. A consequence of this was also the fact that Spann tolerated and even approved of critiques made by his students of National Socialist theories of race which emphasized the role of biology; an issue which would later compromise his relationship with that movement even though he was one of its supporters.[16]

The True State

Othmar Spann’s Universalism was in essence a Catholic form of “Radical Traditionalism”; he believed that there existed eternal principles upon which every social, economic, and political order should be constructed. Whereas the principles of the French Revolution – of liberalism, democracy, and socialism – were contingent upon historical circumstances, bound by world history, there are certain principles upon which most ancient and medieval states were founded which are eternally valid, derived from the Divine order. While specific past state forms which were based on these principles cannot be revived exactly as they were because they held many characteristics which are outdated and historical, the principles upon which they were built and therefore the general model which they provide are timeless and must reinstituted in the modern world, for the systems derived from the French Revolution are invalid and harmful.[17] This timeless model was the Wahre Staat or “True State” – a corporative, monarchical, and elitist state – which was central to Universalist philosophy.

1. Economics

In terms of economics, Spann, like Adam Müller, rejected both capitalism and socialism, advocating a corporatist system relatable to that of the guild system and the landed estates of the Middle Ages; a system in which fields of work and production would be organized into corporations and would be subordinated in service to the state and to the nation, and economic activity would therefore be directed by administrators rather than left solely to itself. The value of each good or commodity produced in this system was determined not by the amount of labor put into it (the labor theory of value of Marx and Smith), but by its “organic use” or “social utility,” which means its usefulness to the social whole and to the state.[18]

Spann’s major reason for rejecting capitalism was because it was individualistic, and thus had a tendency to create disharmony and weaken the spiritual bonds between individuals in the social whole. Although Spann did not believe in eliminating competition from economic life, he pointed out that the extreme competition glorified by capitalists created a market system in which there occurred a “battle of all against all” and in which undertakings were not done in service to the whole and the state but in service to self-centered interests. Universalist economics aimed to create harmony in society and economics, and therefore valued “the vitalising energy of the personal interdependence of all the members of the community . . .”[19]

Furthermore, Spann recognized that capitalism also did result in an unfair treatment by capitalists of those underneath them. Thus while he believed Marx’s theories to be theoretically flawed, Spann also mentioned that “Marx nevertheless did good service by drawing attention to the inequality of the treatment meted out to worker and to entrepreneur respectively in the individualist order of society.”[20] Spann, however, rejected socialist systems in general because while socialism seemed superficially Universalistic, it was in fact a mixture of Universalist and individualist elements. It did not recognize the primacy of the State over individuals and also held that all individuals in society should hold the same position, eliminating all class distinctions, and should receive the same amount of goods. “True universalism looks for an organic multiplicity, for inequality,” and thus recognizes differences even if it works to establish harmony between the parts.[21]

2. Politics

Spann asserted that all democratic political systems were an inversion of the truly valuable political order, which was of even greater importance than the economic system. A major problem of democracy was that it allowed, firstly, the manipulation of the government by wealthy capitalists and financiers whose moral character was usually questionable and whose goals were almost never in accord with the good of the community; and secondly, democracy allowed the triumph of self-interested demagogues who could manipulate the masses. However, even the theoretical base of democracy was flawed, according to Spann, because human beings were essentially unequal, for individuals are always in reality differentiated in their qualities and thus are suited for different positions in the social order. Democracy thus, by allowing a mass of people to decide governmental matters, meant excluding the right of superior individuals to determine the destiny of the State, for “setting the majority in the saddle means that the lower rule over the higher.”[22]

Finally, Spann noted that “demands for democracy and liberty are, once more, wholly individualistic.”[23] In the Universalist True State, the individual would subordinate his will to the whole and would be guided by a sense of selfless duty in service to the State, as opposed to asserting his individual will against all other wills. Furthermore, the individual did not possess rights because of his “rational” character and simply because of being human, as many Enlightenment thinkers asserted, but these rights were derived from the ethics of the particular social whole to which he belonged and from the laws of the State.[24] Universalism also acknowledged the inherent inequalities in human beings and supported a hierarchical organization of the political order, where there would be only “equality among equals” and the “subordination of the intellectually inferior under their intellectual betters.”[25]

In the True State, individuals who demonstrated their leadership skills, their superior nature, and the right ethical character would rise among the levels of the hierarchy. The state would be led by a powerful elite whose members would be selected from the upper levels of the hierarchy based on their merit; it was essentially a meritocratic aristocracy. Those in inferior positions would be taught to accept their role in society and respect their superiors, although all parts of the system are “nevertheless indispensable for its survival and development.”[26] Therefore, “the source of the governing power is not the sovereignty of the people, but the sovereignty of the content.”[27]

Othmar Spann, in accordance with his Catholic religious background, believed in the existence of a supra-sensual, metaphysical, and spiritual reality which existed separately from and above the material reality, and of which the material realm was its imperfect reflection. He asserted that the True State must be animated by Christian spirituality, and that its leaders must be guided by their devotion to Divine laws; the True State was thus essentially theocratic. However, the leadership of the state would receive its legitimacy not only from its religious character, but also by possessing “valid spiritual content,” which “precedes power as it is represented in law and the state.”[28] Thus Spann concluded that “history teaches us that it is the validity of spiritual values that constitutes the spiritual bond. They cannot be replaced by fire and sword, nor by any other form of force. All governance that endures, and all the order that society has thus achieved, is the result of inner domination.”[29]

The state which Spann aimed to restore was also federalistic in nature, uniting all “partial wholes” – corporate bodies and local regions which would have a certain level of local self-governance – with respect to the higher Authority. As Julius Evola wrote, in a description that is in accord with Spann’s views, “the true state exists as an organic whole comprised of distinct elements, and, embracing partial unities [wholes], each possesses a hierarchically ordered life of its own.”[30] All throughout world history the hierarchical, corporative True State appears and reappears; in the ancient states of Sparta, Rome, Persia, Medieval Europe, and so on. The structures of the states of these times “had given the members of these societies a profound feeling of security. These great civilizations had been characterized by their harmony and stability.”[31]

Liberal modernity had created a crisis in which the harmony of older societies was damaged by capitalism and in which social bonds were weakened (even if not eliminated) by individualism. However, Spann asserted that all forms of liberalism and individualism are a sickness which could never succeed in fully eliminating the original, primal reality. He predicted that in the era after World War I, the German people would reassert its rights and would create revolution restoring the True State, would recreate that “community tying man to the eternal and absolute forces present in the universe,”[32] and whose revolution would subsequently resonate all across Europe, resurrecting in modern political life the immortal principles of Universalism.

Spann’s Influence and Reception

Othmar Spann and his circle held influence largely in Germany and Austria, and it was in the latter country that their influence was the greatest. Spann’s philosophy became the basis of the ideology of the Austrian Heimwehr (“Home Guard”) which was led by Ernst Rüdiger von Starhemberg. Leaders of the so-called “Austro-fascist state,” including Engelbert Dollfuss and Kurt Schuschnigg, were also partially influenced by Spann’s thought and by members of the “Spann circle.”[33] However, despite the fact that this state was the only one which truly attempted to actualize his ideas, Spann did not support “Austro-fascism” because he was a pan-Germanist and wanted the German people unified under a single state, which is why he joined Hitler’s National Socialist movement, which he believed would pave the way to the True State.

Despite repeated attempts to influence National Socialist ideology and the leaders of the NSDAP, Spann and his circle were rejected by most National Socialists. Alfred Rosenberg, Robert Ley, and various other authors associated with the SS made a number of attacks on Spann’s school. Rosenberg was annoyed both by Spann’s denial of the importance of blood and by his Catholic theocratic position; he wrote that “the Universalist school of Othmar Spann has successfully refuted idiotic materialist individualism . . . [but] Spann asserted against traditional Greek wisdom, and claimed that god is the measure of all things and that true religion is found only in the Catholic Church.”[34]

Aside from insisting on the reality of biological laws, other National Socialists also criticized Spann’s political proposals. They asserted that his hierarchical state would create a destructive divide between the people and their elite because it insisted on their absolute separateness; it would destroy the unity they had established between the leadership and the common folk. Although National Socialism itself had elements of elitism it was also populist, and thus they further argued that every German had the potential to take on a leadership role, and that therefore, if improved within in the Volksgemeinschaft (“Folk-Community”), the German people were thus not necessarily divisible in the strict view of superior elites and inferior masses.[35]

As was to be expected, Spann’s liberal critics complained that his anti-individualist position was supposedly too extreme, and the social democrats and Marxists argued that his corporatist state would take away the rights of the workers and grant rulership to the bourgeois leaders. Both accused Spann of being an unrealistic reactionary who wanted to revive the Middle Ages.[36] However, here we should note here that Edgar Julius Jung, who was himself basically a type of Universalist and was heavily inspired by Spann’s work, had mentioned that:

We are reproached for proceeding alongside or behind active political forces, for being romantics who fail to see reality and who indulge in dreams of an ideology of the Reich that turns toward the past. But form and formlessness represent eternal social principles, like the struggle between the microcosm and the macrocosm endures in the eternal swing of the pendulum. The phenomenal forms that mature in time are always new, but the great principles of order (mechanical or organic) always remain the same. Therefore if we look to the Middle Ages for guidance, finding there the great form, we are not only not mistaking the present time but apprehending it more concretely as an age that is itself incapable of seeing behind the scenes.[37]

Edgar Jung, who was one of Hitler’s most prominent radical Conservative opponents, expounded a philosophy which was remarkably similar to Spann’s, although there are some differences we would like to point out. Jung believed that neither Fascism nor National Socialism were precursors to the reestablishment of the True State but rather “simply another manifestation of the liberal, individualistic, and secular tradition that had emerged from the French Revolution.”[38] Fascism and National Socialism were not guided by a reference to a Divine power and were still infected with individualism, which he believed showed itself in the fact that their leaders were guided by their own ambitions and not a duty to God or a power higher than themselves.

Edgar Jung also rejected nationalism in the strict sense, although he simultaneously upheld the value of Volk and the love of fatherland, and advocated the reorganization of the European continent on a federalist basis with Germany being the leading nation of the federation. Also in contrast to Spann’s views, Jung believed that genetic inheritance did play a role in the character of human beings, although he believed this role was secondary to cultural and spiritual factors and criticized common scientific racialism for its “biological materialism.”

Jung asserted that what he saw as superior racial elements in a population should be strengthened and the inferior elements decreased: “Measures for the raising of racially valuable components of the German people and for the prevention of inferior currents must however be found today rather than tomorrow.”[39] Jung also believed that the elites of the Reich, while they should be open to accepting members of lower levels of the hierarchy who showed leadership qualities, should marry only within the elite class, for in this way a new nobility possessing leadership qualities strengthened both genetically and spiritually would be developed.[40]

Whereas Jung constantly combatted National Socialism to his life’s end, up until the Anschluss Othmar Spann had remained an enthusiastic supporter of National Socialism, always believing he could eventually influence the Third Reich leadership to adopt his philosophy. This illusion was maintained in his mind until the takeover of Austria by Germany in 1938, soon after which Spann was arrested and imprisoned because he was deemed an ideological threat, and although he was released after a few months, he was forcibly confined to his rural home.[41] After World War II he could never regain any political influence, but he left his mark in the philosophical realm. Spann had a partial influence on Eric Voegelin and also on many Neue Rechte (“New Right”) intellectuals such as Armin Mohler and Gerd-Klaus Kaltenbrunner.[42] He has also had an influence on Radical Traditionalist thought, most notably on Julius Evola, who wrote that Spann “followed a similar line to my own,”[43] although there are obviously certain marked differences between the two thinkers. Spann’s philosophy thus, despite its flaws and limitations, has not been entirely lacking in usefulness and interest.

Notes

1. More detailed information on Othmar Spann’s life than provided in this essay can be found in John J. Haag, Othmar Spann and the Politics of “Totality”: Corporatism in Theory and Practice (Ph.D. Thesis, Rice University, 1969).

2. See Othmar Spann, Types of Economic Theory (London: George Allen and Unwin, 1930), p. 61. We should note to the reader that this book is the only major work by Spann to have been published in English and has also been published under an alternative title as History of Economics.

3. Othmar Spann as quoted in Ernest Mort, “Christian Corporatism,” Modern Age, Vol. 3, No. 3 (Summer 1959), p. 249. Available online here: http://www.mmisi.org/ma/03_03/mort.pdf [2].

4. For a more in-depth and scientific overview of Spann’s studies of society, see Barth Landheer, “Othmar Spann’s Social Theories.” Journal of Political Economy, Vol. 39, No. 2 (April, 1931), pp. 239–48. We should also note to our readers that Othmar Spann’s anti-individualist social theories are more similar to those of other “far Right” sociologists such as Hans Freyer and Werner Sombart. However, it should be remembered that sociologists from nearly all political positions are opposed to individualism to some extent, whether they are of the “moderate Center” or of the “far Left.” Furthermore, anti-individualism is a typical position among many mainstream sociologists today, who recognize that individualistic attitudes – which are, of course, still an issue in societies today just as they were an issue a hundred years ago – have a harmful effect on society as a whole.

5. Othmar Spann, Der wahre Staat (Leipzig: Verlag von Quelle und Meyer, 1921), p. 29. Quoted in Eric Voegelin, Theory of Governance and Other Miscellaneous Papers, 1921–1938 (Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 2003), p. 68.

6. Spann, Der wahre Staat, p. 29. Quoted in Voegelin, Theory of Governance, p. 69.

7. Spann, Types of Economic Theory, pp. 60–61.

8. Ibid., p. 61.

9. Spann, Der wahre Staat, pp. 29 & 34. Quoted in Voegelin, Theory of Governance, pp. 70–71.

10. J. Glenn Friesen, “Dooyeweerd, Spann, and the Philosophy of Totality,” Philosophia Reformata, 70 (2005), p. 6. Available online here: http://members.shaw.ca/hermandooyeweerd/Totality.pdf [3].

11. Spann, Types of Economic Theory, p. 199.

12. See Haag, Spann and the Politics of “Totality,” p. 48.

13. Eric Voegelin, Race and State (Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 1997), pp. 117–18.

14. Ludwig F. Clauss, Rasse und Seele (Munich: J. F. Lehmann, 1926), pp. 20–21. Quoted in Richard T. Gray, About Face: German Physiognomic Thought from Lavater to Auschwitz (Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 2004), p. 307.

15. For an overview of Evola’s theory of race, see Michael Bell, “Julius Evola’s Concept of Race: A Racism of Three Degrees.” The Occidental Quarterly, Vol. 9, No. 4 (Winter 2009–2010), pp. 101–12. Available online here: http://toqonline.com/archives/v9n2/TOQv9n2Bell.pdf [4]. For a closer comparison between the Evola’s theories and Clauss’s, see Julius Evola’s The Elements of Racial Education (Thompkins & Cariou, 2005).

16. See Haag, Spann and the Politics of “Totality,” p. 136.

17. A more in-depth explanation of “Radical Traditionalism” can be found in Chapter 1: Revolution – Counterrevolution – Tradition” in Julius Evola, Men Among the Ruins: Postwar Reflections of a Radical Traditionalist, trans. Guido Stucco, ed. Michael Moynihan (Rochester: Inner Traditions, 2002).

18. See Spann, Types of Economic Theory, pp. 162–64.

19. Ibid., p. 162.

20. Ibid., p. 226.

21. Ibid., p. 230.

22. Spann, Der wahre Staat, p. 111. Quoted in Janek Wasserman, Black Vienna, Red Vienna: The Struggle for Intellectual and Political Hegemony in Interwar Vienna, 1918–1938 (Ph.D. Dissertion, Washington University, 2010), p. 80.

23. Spann, Types of Economic Theory, pp. 212.

24. For a commentary on individual natural rights theory, see Ibid., pp.53 ff.

25. Spann, Der wahre Staat, p. 185. Quoted in Wassermann, Black Vienna, Red Vienna, p. 82.

26. Haag, Spann and the Politics of “Totality,” p. 32.

27. Othmar Spann, Kurzgefasstes System der Gesellschaftslehre (Berlin: Quelle und Meyer, 1914), p. 429. Quoted in Voegelin, Theory of Governance, p. 301.

28. Spann, Gesellschaftslehre, p. 241. Quoted in Voegelin, Theory of Governance, p. 297.

29. Spann, Gesellschaftslehre, p. 495. Quoted in Voegelin, Theory of Governance, p. 299.

30. Julius Evola, The Path of Cinnabar (London: Integral Tradition Publishing, 2009), p. 190.

31. Haag, Spann and the Politics of “Totality,” p. 39.

32. Ibid., pp. 40–41.

33. See Günter Bischof, Anton Pelinka, Alexander Lassner, The Dollfuss/Schuschnigg Era in Austria: A Reassessment (New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Publishers, 2003), pp. 16, 32, & 125 ff.

34. Alfred Rosenberg, The Myth of the Twentieth Century (Sussex, England: Historical Review Press, 2004), pp. 458–59.

35. See Haag, Spann and the Politics of “Totality,” pp. 127–29.

36. See Ibid., pp. 66 ff.

37. Edgar Julius Jung, “Germany and the Conservative Revolution,” in: The Weimar Republic Sourcebook, edited by Anton Kaes, Martin Jay, and Edward Dimendberg (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1995), p. 354.

38. Larry Eugene Jones, “Edgar Julius Jung: The Conservative Revolution in Theory and Practice,” Conference Group for Central European History of the American Historical Association, Vol. 21, No. 02 (1988), p. 163.

39. Edgar Julius Jung, “People, Race, Reich,” in: Europa: German Conservative Foreign Policy 1870–1940, edited by Alexander Jacob (Lanham, MD, USA: University Press of America, 2002), p. 101.

40. For a more in-depth overview of Jung’s life and thought, see Walter Struve, Elites Against Democracy: Leadership Ideals in Bourgeois Political Thought in Germany, 1890–1933 (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University, 1973), pp. 317 ff. See also Edgar Julius Jung, The Rule of the Inferiour, 2 vols. (Lewiston, New York: Edwin Mellon Press, 1995).

41. Haag, Spann and the Politics of “Totality,” pp. 154–55.

42. See our previous citations of Voegelin’s Theory of Governance and Race and State; Armin Mohler, Die Konservative Revolution in Deutschland 1918–1932 (Stuttgart: Friedrich Vorwerk Verlag, 1950); “Othmar Spann” in Gerd-Klaus Kaltenbrunner, Vom Geist Europas, Vol. 1 (Asendorf: Muth-Verlag, 1987).

43. Evola, Path of Cinnabar, p. 155.

Dans son livre, Le féminisme et ses dérives, rendre un père à l’enfant-roi, le professeur d’histoire-géographie et ancien féministe Jean Gabard nous explique comment et pourquoi notre société en est arrivée là. Il ne nous donne pas de recette miracle mais il nous explique que deux idéolog

Dans son livre, Le féminisme et ses dérives, rendre un père à l’enfant-roi, le professeur d’histoire-géographie et ancien féministe Jean Gabard nous explique comment et pourquoi notre société en est arrivée là. Il ne nous donne pas de recette miracle mais il nous explique que deux idéolog

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

Surfant sur la vague de l’opuscule philosophique mi-sérieux mi-drôle (ou plutôt : traitant sérieusement d’un sujet à première vue saugrenu) comme le célèbre On Bullshit de Harry G. Frankfurt ou le récent Art of Procrastination de John Perry, Aaron James nous livre avec Assholes: A Theory une analyse d’un phénomène somme toute assez peu étudié : le connard (ma traduction de l’anglais “assholes”, même si celui-ci se traduit plus littéralement par “trou-du-cul” - j’espère que ce choix apparaîtra comme justifié à la lecture de ce qui suit ).

Surfant sur la vague de l’opuscule philosophique mi-sérieux mi-drôle (ou plutôt : traitant sérieusement d’un sujet à première vue saugrenu) comme le célèbre On Bullshit de Harry G. Frankfurt ou le récent Art of Procrastination de John Perry, Aaron James nous livre avec Assholes: A Theory une analyse d’un phénomène somme toute assez peu étudié : le connard (ma traduction de l’anglais “assholes”, même si celui-ci se traduit plus littéralement par “trou-du-cul” - j’espère que ce choix apparaîtra comme justifié à la lecture de ce qui suit ).

Pour la bonne forme, rappelons qu’un mot est généralement utilisé pour désigner des objets ou des réalités consacrés par l’usage. Ce qui fait que chacun peut comprendre autrui sans trop de malentendus.

Pour la bonne forme, rappelons qu’un mot est généralement utilisé pour désigner des objets ou des réalités consacrés par l’usage. Ce qui fait que chacun peut comprendre autrui sans trop de malentendus.

Perché è necessario ribadire che l’idea socialista è necessariamente legata al concetto di disciplina? A più di quarant’anni dal tristemente famoso ’68, il ribellismo anarco-libertario ha pesantemente influenzato la “forma mentis” del militante di sinistra, e ha condizionato l’azione dei gruppi-movimenti determinati a realizzare il socialismo. La disciplina, intesa come serie di regole, norme ferree ed esercizi, necessari per il corretto funzionamento di qualunque forma di organizzazione politica (partiti) e statale, è fondamento di ogni costruzione sociale. Senza di essa, non è possibile generare e mantenere in vita nulla. In Europa Occidentale il rifiuto e la condanna del modo di produzione capitalistico sono costantemente associati al disprezzo per lo Stato, per la nazione, per la Polizia e per l’Esercito. In realtà non esiste alcuna alternativa politica seria che non prenda in considerazione l’idea di poter generare una nuova formazione statale e potenziare gli organismi di Difesa e tutela dell’ordine pubblico. Idee distorte sono il riflesso di comportamenti individuali altrettanto nocivi e antisociali, tipici della sovrastruttura culturale liberalista dell’ultima borghesia, non dei socialisti. Il passaggio che ha portato molti militanti dal Partito Comunista più forte e numeroso del campo occidentale ai “centri sociali occupati” o a repliche sempre più scadenti di “Democrazia Proletaria”(1), non può essere compreso senza riflettere sull’incapacità cronica del militante o simpatizzante di “sinistra”, di concepire il socialismo come società ordinata e rigidamente organizzata, dove non esistono consumo di sostanze stupefacenti o psicotrope, “l’obiezione di coscienza” o parate dell’orgoglio omosessuale.

Perché è necessario ribadire che l’idea socialista è necessariamente legata al concetto di disciplina? A più di quarant’anni dal tristemente famoso ’68, il ribellismo anarco-libertario ha pesantemente influenzato la “forma mentis” del militante di sinistra, e ha condizionato l’azione dei gruppi-movimenti determinati a realizzare il socialismo. La disciplina, intesa come serie di regole, norme ferree ed esercizi, necessari per il corretto funzionamento di qualunque forma di organizzazione politica (partiti) e statale, è fondamento di ogni costruzione sociale. Senza di essa, non è possibile generare e mantenere in vita nulla. In Europa Occidentale il rifiuto e la condanna del modo di produzione capitalistico sono costantemente associati al disprezzo per lo Stato, per la nazione, per la Polizia e per l’Esercito. In realtà non esiste alcuna alternativa politica seria che non prenda in considerazione l’idea di poter generare una nuova formazione statale e potenziare gli organismi di Difesa e tutela dell’ordine pubblico. Idee distorte sono il riflesso di comportamenti individuali altrettanto nocivi e antisociali, tipici della sovrastruttura culturale liberalista dell’ultima borghesia, non dei socialisti. Il passaggio che ha portato molti militanti dal Partito Comunista più forte e numeroso del campo occidentale ai “centri sociali occupati” o a repliche sempre più scadenti di “Democrazia Proletaria”(1), non può essere compreso senza riflettere sull’incapacità cronica del militante o simpatizzante di “sinistra”, di concepire il socialismo come società ordinata e rigidamente organizzata, dove non esistono consumo di sostanze stupefacenti o psicotrope, “l’obiezione di coscienza” o parate dell’orgoglio omosessuale.

Othmar Spann was an Austrian philosopher who was a key influence on German conservative and traditionalist thought in the period after World War I, and he is thus considered a representative of the intellectual movement known as the “Conservative Revolution.” Spann was a professor of economics and sociology at the University of Vienna, where he taught not only scientific social and economic theories, but also influenced many students with the presentation of his worldview in his lectures. As a result of this he formed a large group of followers known as the Spannkreis (“Spann Circle”). This circle of intellectuals attempted to influence politicians who would be sympathetic to “Spannian” philosophy in order to actualize its goals.[1]

Othmar Spann was an Austrian philosopher who was a key influence on German conservative and traditionalist thought in the period after World War I, and he is thus considered a representative of the intellectual movement known as the “Conservative Revolution.” Spann was a professor of economics and sociology at the University of Vienna, where he taught not only scientific social and economic theories, but also influenced many students with the presentation of his worldview in his lectures. As a result of this he formed a large group of followers known as the Spannkreis (“Spann Circle”). This circle of intellectuals attempted to influence politicians who would be sympathetic to “Spannian” philosophy in order to actualize its goals.[1] L'homme cool n'est ni le décadent pessimiste de Nietzsche ni le travailleur opprimé de Marx, il ressemble davantage au téléspectateur essayant "pour voir" les uns après les autres les programmes du soir, au consommateur remplissant son caddy, au vacancier hésitant entre un séjour sur les plages espagnoles et le camping en Corse. L'aliénation analysée par Marx, résultant de la mécanisation du travail, a fait place à une apathie induite par le champ vertigineux des possibles et le libre-service généralisé ; alors commence l'indifférence pure, débarrassée de la misère et de la "perte de réalité" des débuts de l'industrialisation.

L'homme cool n'est ni le décadent pessimiste de Nietzsche ni le travailleur opprimé de Marx, il ressemble davantage au téléspectateur essayant "pour voir" les uns après les autres les programmes du soir, au consommateur remplissant son caddy, au vacancier hésitant entre un séjour sur les plages espagnoles et le camping en Corse. L'aliénation analysée par Marx, résultant de la mécanisation du travail, a fait place à une apathie induite par le champ vertigineux des possibles et le libre-service généralisé ; alors commence l'indifférence pure, débarrassée de la misère et de la "perte de réalité" des débuts de l'industrialisation.

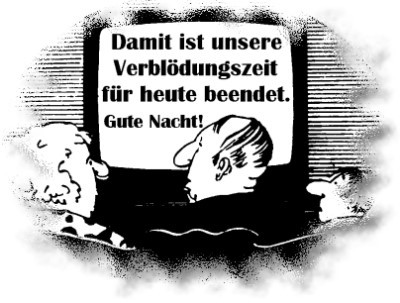

In Zeiten, in denen Politiker das gemeine Volk zum Schenkelklopfen animieren und dessen Klugheit und Macht (am Wahltag) beschwören, ist das Verdummungsrisiko allgegenwärtig. Zu den besonderen Gefahrenquellen zählen neben politischen Veranstaltungen aber vor allem die Medien. Von „digitaler Demenz“ spricht im Zusammenhang mit TV, Google und Co. der Neurowissenschaftler Manfred Spitzer. Während der Intelligenzforscher Joseph Chilton Pearce gar der Meinung ist, daß unter dem Einfluß des Fernsehens die menschliche Evolution überhaupt an ihr Ende gekommen sei.

In Zeiten, in denen Politiker das gemeine Volk zum Schenkelklopfen animieren und dessen Klugheit und Macht (am Wahltag) beschwören, ist das Verdummungsrisiko allgegenwärtig. Zu den besonderen Gefahrenquellen zählen neben politischen Veranstaltungen aber vor allem die Medien. Von „digitaler Demenz“ spricht im Zusammenhang mit TV, Google und Co. der Neurowissenschaftler Manfred Spitzer. Während der Intelligenzforscher Joseph Chilton Pearce gar der Meinung ist, daß unter dem Einfluß des Fernsehens die menschliche Evolution überhaupt an ihr Ende gekommen sei.

Marcel de Corte est un auteur inconnu du grand public même cultivé et cependant, il développe une pensée philosophique exceptionnelle du point de vue de la crise actuelle de l’intelligence et de la société.

Marcel de Corte est un auteur inconnu du grand public même cultivé et cependant, il développe une pensée philosophique exceptionnelle du point de vue de la crise actuelle de l’intelligence et de la société.