Entretien avec Robert Steuckers sur la réception de l’œuvre de Julius Evola en Belgique

Propos recueillis par Denis Ilmas

Q. : Monsieur Steuckers, comment avez-vous découvert Julius Evola ? Quand en avez-vous entendu parler pour la première fois ?

RS : Dans la Librairie Devisscher, au coin de la rue Franz Merjay et de la Chaussée de Waterloo, dans le quartier « Ma Campagne », à cheval sur Saint-Gilles et Ixelles. « Frédéric Beerens », un camarade d’école, un an plus âgé que moi, avait découvert « Les hommes au milieu des ruines » dans cette librairie, l’avait lu, et m’en avait parlé tandis que nous faisions la queue pour commander d’autres ouvrages ou quelques manuels scolaires. Ce fut la toute première fois que j’entendis prononcer le nom d’Evola. J’avais dix-sept ans. Nous étions en septembre 1973 et nous étions tout juste revenus d’un voyage scolaire en Grèce. Pour Noël, le Comte Guillaume de Hemricourt de Grünne, le patron de mon père, m’offrait toujours un cadeau didactique : cette année-là, pour la première fois, j’ai pu aller moi-même acheter les livres que je désirais, muni de mon petit budget. Je me suis rendu en un endroit qui, malheureusement, n’existe plus à Bruxelles, la grande librairie Corman, et je me suis choisi trois livres : « L’Etat universel » d’Ernst Jünger, « Un poète et le monde » de Gottfried Benn et « Révolte contre le monde moderne » de Julius Evola. L’année 1973 fut, rappelons-le, une année charnière en ce qui concerne la réception de l’œuvre d’Evola en Italie et en Flandre : tour à tour Adriano Romualdi, disciple italien d’Evola et bon connaisseur de la « révolution conservatrice » allemande grâce à sa maîtrise de la langue de Goethe, décéda dans un accident d’auto, tout comme le correspondant flamand de Renato del Ponte et l’animateur d’un « Centro Studi Evoliani » en Flandre, Jef Vercauteren. Je n’ai forcément jamais connu Jef Vercauteren et, là, il y a eu une rupture de lien, fort déplorable, entre les matrices italiennes de la mouvance évolienne et leurs antennes présentes dans les anciens Pays-Bas autrichiens.

Je dois vous dire qu’au départ, la lecture de « Révolte contre le monde moderne » nous laissait perplexes, surtout Beerens, le futur médecin chevronné, féru de sciences biologiques et médicales : on trouvait que trop d’esprits faibles, après lecture de ce classique, se laisseraient peut-être entrainer dans une sorte de monde faussement onirique ou acquerraient de toutes les façons des tics langagiers incapacitants et « ridiculisants » (à ce propos, on peut citer l’exemple d’un Arnaud Guyot-Jeannin, tour à tour fustigé par Philippe Baillet, qui lui reprochait l’ « inculture pédante du Sapeur Camember », ou par Christopher Gérard, qui le traitait d’ « aliboron » ou de « chaouch »). Une telle dérive, chez les aliborons pédants, est évidemment tout à fait possible et très aisée parce qu’Evola présentait à ses lecteurs un monde très idéal, très lumineux, je dirais, pour ma part, très « archangélique » et « michaëlien », afin de faire contraste avec les pâles figures subhumaines que génère la modernité ; aujourd’hui, faut-il s’empresser de l’ajouter, elle les génère à une cadence accélérée, Kali Yuga oblige. L’onirisme fait que bon nombre de médiocres s’identifient à de nobles figures pour compenser leurs insuffisances (ou leurs suffisances) : c’est effectivement un risque bien patent chez les évolomanes sans forte épine dorsale culturelle.

Mais, chose incontournable, la lecture de « Révolte » marque, très profondément, parce qu’elle vous communique pour toujours, et à jamais, le sens d’une hiérarchie des valeurs : l’Occident, en optant pour la modernité, a nié et refoulé les notions de valeur, d’excellence, de service, de sublime, etc. Après lecture de « Révolte », on ne peut plus que rejeter les anti-valeurs qui ont refoulé les valeurs impérissables, sans lesquelles rien ne peut plus valoir quoi que ce soit dans le monde.

« Révolte » et la notion de numineux

Plus tard, « Révolte » satisfera davantage nos aspirations et nos exigences de rigueur, tout simplement parce que nous n’avions pas saisi entièrement, au départ, la notion de « numineux », excellemment mise en exergue dans le chapitre 7 du livre et que je médite toujours lorsque je longe un beau cours d’eau ou quand mes yeux boivent littéralement le paysage à admirer du haut d’un sommet, avec ou sans forteresse (dans l’Eifel, les Vosges, le Lomont, le Jura ou les Alpes ou dans une crique d’Istrie ou dans un méandre de la Moselle ou sur les berges de la Meuse ou du Rhin). « Masques et visages du spiritualisme contemporain » nous a apporté une saine méfiance à l’endroit des ersatz de religiosité, souvent « made in USA », alternatives très bas de gamme que nous fait miroiter un vingtième siècle à la dérive : songeons, toutefois dans un autre contexte, à la multiplication des temples scientologiques, évangéliques, etc. ou à l’emprise des « Témoins de Jéhovah » sur des pays catholiques comme l’Espagne ou l’Amérique latine, qui, de ce fait, subissent une subversion sournoise, disloquant leur identité politique.

Nous n’avons découvert le reste de l’œuvre d’Evola que progressivement, au fil du temps, avec les traductions françaises de Philippe Baillet mais aussi parce que les latinistes de notre groupe, dont le regretté Alain Derriks et moi-même, commandaient les livres non traduits du Maître aux Edizioni di Ar (Giorgio Freda) ou aux Edizioni all’Insegno del Veltro (Claudio Mutti). Je crois n’avoir atteint une certaine (petite) maturité évolienne qu’en 1998, quand j’ai été amené à prendre la parole à Vienne en cette année-là, et à Frauenfeld, près de Zürich, en 1999, respectivement pour le centième anniversaire de la naissance d’Evola et pour le vingt-cinquième anniversaire de son absence. L’idée centrale est celle de l’ « homme différencié », qui pérégrine, narquois, dans un monde de ruines. Evola nous apprend la distance, à l’instar de Jünger, avec sa figure de l’ « anarque ».

Q. : Quelques années plus tard, la revue « Totalité » sera la première, dans l’espace linguistique francophone, à publier régulièrement des textes d’Evola. De « Totalité » émergeront une série de revues, telles « Rebis », « Kalki », « L’Age d’Or », puis les Editions Pardès. Comment tout cela a-t-il été perçu en Belgique à l’époque ?

RS : Le coup d’envoi de cette longue série d’initiatives, qui nous ramène à l’actualité éditoriale que vous évoquez, a été, à Bruxelles du moins, une prise de parole de Daniel Cologne et Georges Gondinet, dans une salle de l’Helder, rue du Luxembourg, à un jet de pierre de l’actuel Parlement Européen, qui n’existait pas à l’époque. C’était en octobre 1976. Depuis, le quartier vit à l’heure de la globalisation, échelon « Europe », Europe « eurocratique » s’entend. A l’époque, c’était un curieux mixte : fonctionnaires de plusieurs ministères belges, étudiants de l’école de traducteurs/interprètes (dont j’étais), derniers résidents du quartier se côtoyaient dans les estaminets de la Place du Luxembourg et, dans les rues adjacentes, des hôteliers peu regardants louaient des chambres de « 5 à 7 » pour bureaucrates en quête d’érotisme rapide camouflé en « heures supplémentaires », tout cela en face d’un vénérable lycée de jeunes filles, qui faisait également fonction d’école pour futures professeurs féminins d’éducation physique (le « Parnasse »). En arrière-plan, la gare dite du Quartier Léopold ou du Luxembourg, vieillotte et un peu sordide, flanquée d’un bureau de poste crasseux, d’où j’ai envoyé quantité de mandats dans le monde pour m’abonner à toutes sortes de revues de la « mouvance » ou pour payer mes dettes auprès du bouquiniste nantais Jean-Louis Pressensé. En cette soirée pluvieuse et assez froide d’octobre 1976, Daniel Cologne et Georges Gondinet étaient venus présenter leur « Cercle Culture & Liberté », à l’invitation de Georges Hupin, animateur du GRECE néo-droitiste à l’époque. Dans la salle, il y avait le public « nouvelle droite » habituel mais aussi Gérard Hupin, éditeur de « La Nation Belge » et, à ce titre, héritier de Fernand Neuray, le correspondant belge de Charles Maurras (Georges Hupin et Daniel Cologne étaient tous deux collaborateurs occasionnels de « La Nation Belge »). Maître Gérard Hupin était flanqué du Général Janssens, dernier commandant de la « Force Publique » belge du Congo. J’étais accompagné d’Alain Derriks, qui deviendra aussitôt le correspondant belge du « Cercle Culture & Liberté ». Les contacts étaient pris et c’est ainsi qu’en 1977, je me retrouvai, pour représenter en fait Derriks, empêché, à Puiseaux dans l’Orléanais, lors de la journée qui devait décider du lancement de la revue « Totalité ». Il y avait là Daniel Cologne (alors résident à Genève), Jean-François Mayer (qui fera en Suisse une brillante carrière de spécialiste ès religions), Eric Vatré de Mercy (à qui l’on devra ultérieurement quelques bonnes biographies d’auteurs), Philippe Baillet (traducteur d’Evola) et Georges Gondinet (futur directeur des éditions Pardès et, en cette qualité, éditeur de Julius Evola).

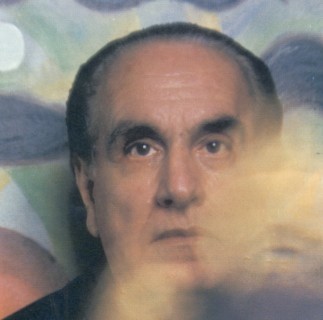

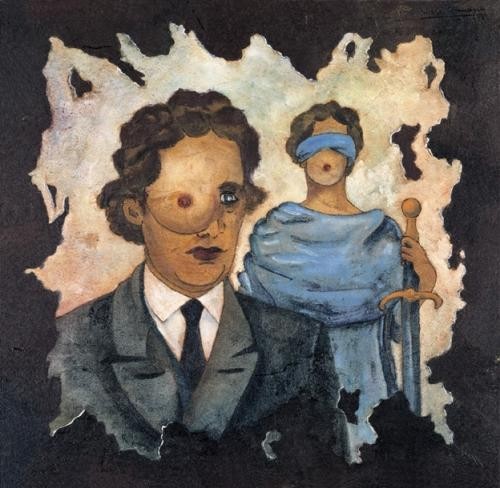

Je rencontre Eemans dans une Galerie de la Chaussée de Charleroi

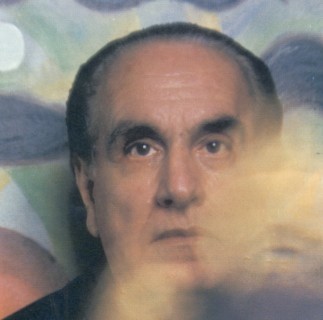

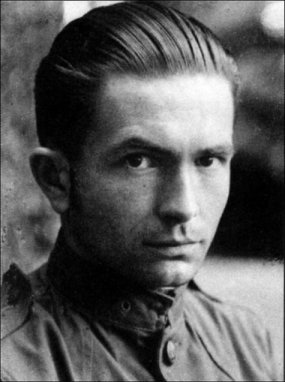

Tout cela a, vaille que vaille, formé un petit réseau. Mais il faut avouer, avec le recul, qu’il n’a pas véritablement fonctionné, mis à part des échanges épistolaires et quelques contributions à « Totalité » (une recension, un seul article et une traduction en ce qui me concerne…). Rapidement, Georges Gondinet deviendra le seul maître d’œuvre de l‘initiative, en prenant en charge tout le boulot et en recrutant de nouveaux collaborateurs, dont celle qui deviendra son épouse, Fabienne Pichard du Page. Lorsqu’il revenait de Suisse à Bruxelles, en passant par Paris, Cologne faisait office de messager. Il nous racontait surtout les mésaventures des cercles suisses autour du NOS (« Nouvel Ordre Social ») et de la revue « Le Huron », qu’il animait là-bas avec d’autres. Ainsi, en 1978, par un coup de fil, Cologne m’annonce avec fracas, avec ce ton précipité et passionné qui le caractérisait en son jeune temps, qu’il avait pris contact avec un certain Marc. Eemans, peintre surréaliste, historien de l’art et détenteur de savoirs voire de secrets des plus intéressants. A peine rentré dans la « mouvance », j’ai tout de suite eu envie de la sortir de ses torpeurs et de ses ritournelles : alors, vous pensez, un « surréaliste », un artiste qui, de plus, exposait officiellement ses œuvres dans une galerie de la Chaussée de Charleroi, voilà sans nul doute l’aubaine que nous attendions, Derriks et moi. J’étais à Wezembeek-Oppem quand j’ai réceptionné le coup de fil de Cologne : j’ai sauté sur mes deux jambes, couru à l’arrêt de bus et foncé vers la Chaussée de Charleroi, ce qui n’était pas une mince affaire à l’époque du « 30 » qui brinquebalait bruyamment, crachant de noires volutes de mazout, dans toutes les rues et ruelles de Wezembeek-Oppem avant d’arriver à Tomberg, première station de métro en ce temps-là. Il faisait déjà sombre quand je suis arrivé à la Galerie, Chaussée de Charleroi. Eemans était seul au fond de l’espace d’exposition ; il lisait, comme je l’ai déjà expliqué, « le nez chaussé de lunettes à grosses montures d’écaille noire ». Agé de 71 ans à l’époque, Eemans (photo en 1930) m’a accueilli gentiment, comme un grand-père affable, heureux qu’Evola ait de jeunes lecteurs en Belgique, ce qui lui permettrait d’étoffer son projet : prendre le relais de Jef Vercauteren, décédé depuis cinq ans, sans laisser de grande postérité en pays flamand. Cologne disparu, amorçant sa « vie cachée » qui durera plus de vingt ans, le groupe bruxellois n’a pratiquement plus entretenu de liens avec l’antenne française du réseau « Culture & Liberté ». Il restait donc lié à Eemans seul et à ses initiatives. Gondinet, bien épaulé par Fabienne Pichard du Page, lancera « Rebis », « L’Age d’or », « Kalki » et les éditions Pardès (avec leurs diverses collections, dont « B-A-BA » et « Que lire ? »). Baillet continuera à traduire des ouvrages italiens (dont un excellent ouvrage de Claudia Salaris sur l’aventure de d’Annunzio à Fiume) puis participera à la revue « Politica Hermetica » et fera un passage encore plus bref que le mien au secrétariat de rédaction de « Nouvelle école », la revue de l’inénarrable de Benoist (cf. infra). Et les autres s’éparpilleront dans des activités diverses et fort intéressantes.

Tout cela a, vaille que vaille, formé un petit réseau. Mais il faut avouer, avec le recul, qu’il n’a pas véritablement fonctionné, mis à part des échanges épistolaires et quelques contributions à « Totalité » (une recension, un seul article et une traduction en ce qui me concerne…). Rapidement, Georges Gondinet deviendra le seul maître d’œuvre de l‘initiative, en prenant en charge tout le boulot et en recrutant de nouveaux collaborateurs, dont celle qui deviendra son épouse, Fabienne Pichard du Page. Lorsqu’il revenait de Suisse à Bruxelles, en passant par Paris, Cologne faisait office de messager. Il nous racontait surtout les mésaventures des cercles suisses autour du NOS (« Nouvel Ordre Social ») et de la revue « Le Huron », qu’il animait là-bas avec d’autres. Ainsi, en 1978, par un coup de fil, Cologne m’annonce avec fracas, avec ce ton précipité et passionné qui le caractérisait en son jeune temps, qu’il avait pris contact avec un certain Marc. Eemans, peintre surréaliste, historien de l’art et détenteur de savoirs voire de secrets des plus intéressants. A peine rentré dans la « mouvance », j’ai tout de suite eu envie de la sortir de ses torpeurs et de ses ritournelles : alors, vous pensez, un « surréaliste », un artiste qui, de plus, exposait officiellement ses œuvres dans une galerie de la Chaussée de Charleroi, voilà sans nul doute l’aubaine que nous attendions, Derriks et moi. J’étais à Wezembeek-Oppem quand j’ai réceptionné le coup de fil de Cologne : j’ai sauté sur mes deux jambes, couru à l’arrêt de bus et foncé vers la Chaussée de Charleroi, ce qui n’était pas une mince affaire à l’époque du « 30 » qui brinquebalait bruyamment, crachant de noires volutes de mazout, dans toutes les rues et ruelles de Wezembeek-Oppem avant d’arriver à Tomberg, première station de métro en ce temps-là. Il faisait déjà sombre quand je suis arrivé à la Galerie, Chaussée de Charleroi. Eemans était seul au fond de l’espace d’exposition ; il lisait, comme je l’ai déjà expliqué, « le nez chaussé de lunettes à grosses montures d’écaille noire ». Agé de 71 ans à l’époque, Eemans (photo en 1930) m’a accueilli gentiment, comme un grand-père affable, heureux qu’Evola ait de jeunes lecteurs en Belgique, ce qui lui permettrait d’étoffer son projet : prendre le relais de Jef Vercauteren, décédé depuis cinq ans, sans laisser de grande postérité en pays flamand. Cologne disparu, amorçant sa « vie cachée » qui durera plus de vingt ans, le groupe bruxellois n’a pratiquement plus entretenu de liens avec l’antenne française du réseau « Culture & Liberté ». Il restait donc lié à Eemans seul et à ses initiatives. Gondinet, bien épaulé par Fabienne Pichard du Page, lancera « Rebis », « L’Age d’or », « Kalki » et les éditions Pardès (avec leurs diverses collections, dont « B-A-BA » et « Que lire ? »). Baillet continuera à traduire des ouvrages italiens (dont un excellent ouvrage de Claudia Salaris sur l’aventure de d’Annunzio à Fiume) puis participera à la revue « Politica Hermetica » et fera un passage encore plus bref que le mien au secrétariat de rédaction de « Nouvelle école », la revue de l’inénarrable de Benoist (cf. infra). Et les autres s’éparpilleront dans des activités diverses et fort intéressantes.

Q. : Parlez-nous davantage de Marc. Eemans…

RS : Eemans a donc lancé son « Centro Studi Evoliani », que nous suivions avec intérêt. La tâche n’a pas été facile : Eemans se heurtait à une difficulté majeure ; en effet, comment importer le corpus d’un penseur traditionaliste italien, de surcroît ancien de l’avant-garde dadaïste de Tristan Tzara, dans un contexte belge qui ignorait tout de lui. Quelques livres seulement étaient traduits en français mais rien, par exemple, de son œuvre majeure sur le bouddhisme, « La doctrine de l’Eveil ». En néerlandais, il n’y avait rien, strictement rien, sinon quelques reprints tirés à la hâte et en très petites quantités à Anvers : il s’agissait des éditions allemandes de ses ouvrages, dont « Heidnischer Imperialismus ». En français, l’œuvre n’était que très incomplètement traduite et nous n’avions aucun travail sérieux d’introduction à celle-ci, à part un excellent essai de Philippe Baillet (« Julius Evola ou l’affirmation absolue »), paru d’abord comme cahier, sous la houlette du « Centro Studi Evoliani » français, dirigé par Léon Colas. Ni Boutin ni Lippi n’avaient encore sorti leurs thèses universitaires solidement charpentées sur Evola. Gondinet et Cologne, dans le cadre de leur « Cercle Culture & Liberté » n’avaient édité que quelques bonnes brochures et les tout premiers numéros de « Totalité » étaient fort artisanaux, faute de moyens. En fait, Eemans n’avait pas de véritable public, ne pouvait en trouver un en Belgique, en une telle époque de matérialisme et de gauchisme, où les grandes questions métaphysiques n’éveillaient plus le moindre intérêt. Mais il n’a pas reculé : il a organisé ses réunions avec régularité, même si elles n’attiraient pas un grand nombre d’intéressés. Au cours de l’une de celle-ci, j’ai présenté un article de Giorgio Locchi sur la notion d’empire, paru dans « Nouvelle école », la revue d’Alain de Benoist. Dans la salle, il y avait Pierre Hubermont, l’écrivain prolétarien et communiste d’avant-guerre, auteur de « Treize hommes dans la mine », ouvrage couronné d’un prix littéraire à la fin des années 20. Hubermont, comme beaucoup de militants ouvriers communistes de sa génération, avait été dégoûté par les purges staliniennes, par la volte-face des communistes à Barcelone pendant la guerre civile espagnole, où ils avaient organisé la répression contre les socialistes révolutionnaires du POUM et contre les anarchistes. Mais Hubermont ne choisit pas l’échappatoire facile d’un trotskisme figé et finalement à la solde des services anglais ou américains : il tâtonne, trouve dans le néo-socialisme de De Man des pistes utiles. Pendant la seconde conflagration intereuropéenne, Hubermont se retrouve à la tête de la revue « Wallonie », qui préconise un socialisme local, adapté aux circonstances des provinces industrielles wallonnes, dans le cadre d’un « internationalisme » non plus abstrait mais découlant de l’idée impériale, rénovée, en ces années-là, par l’européisme ambiant, notamment celui véhiculé par Giselher Wirsing. Hubermont était heureux qu’un gamin comme moi eût parlé de l’idée impériale et, avec une extrême gentillesse, m’a prodigué des conseils. D’autres fois, le Professeur Piet Tommissen est venu nous parler de Carl Schmitt et de Vilfredo Pareto. Une dame est également venue nous lire des textes de Heidegger, à l’occasion de la parution du livre de Jean-Michel Palmier, « Les écrits politiques de Heidegger ». Les thèmes abordés à la tribune du « Centro Studi Evoliani » n’étaient donc pas exclusivement « traditionalistes » ou « évoliens ». Eemans lance également l’édition d’une série de petites brochures et, plus tard, nous bénéficierons de l’appui généreux de Salvatore Verde, haut fonctionnaire italien de ce qui fut la CECA et futur directeur de la revue italienne « Antibancor », consacrée aux questions économiques et éditée par les Edizioni di Ar (cette revue éditera notamment en version italienne une de mes conférences à l’Université d’été 1990 du GRECE sur les « hétérodoxies » en sciences économiques, que l’inénarrable de Benoist n’avait bien entendu pas voulu éditer, en même temps que d’autres textes, de Nicolas Franval et de Bernard Notin, sur les « régulationnistes » ; je précise qu’il s’agissait de la « cellule » mise sur pied à l’époque par le GRECE pour étudier les questions économiques). Toutes les activités du « Centro Studi Evoliani » de Bruxelles ne m’ont évidemment laissé que de bons souvenirs.

Q. : Mais qui fut Eemans au-delà de ses activités au sein du « Centro Studi Evoliani » ?

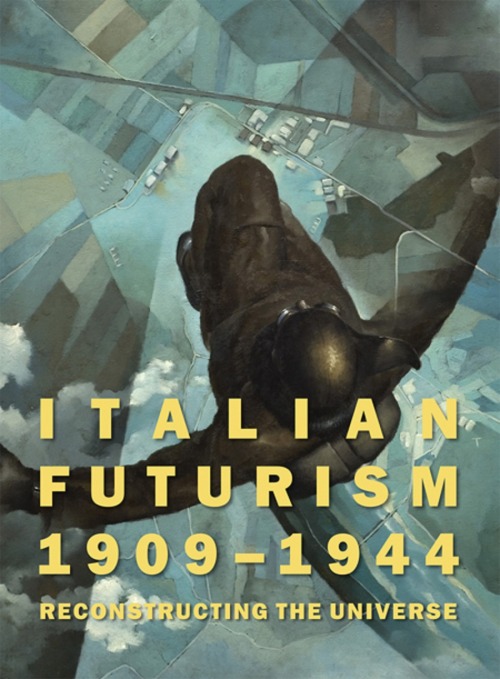

RS : J’ai très vite su qu’Eemans avait été, après guerre, un véritable encyclopédiste des arts en Belgique. Plusieurs ouvrages luxueux sur l’histoire de l’art sont dus à sa plume. Ils ont été écrits avec grande sérénité et avec le souci de ménager toutes les susceptibilités d’un monde foisonnant, où les querelles de personnes sont légion. Ces livres font référence encore aujourd’hui. Dans un coin de son salon, où était placé un joli petit meuble recouvert d’une plaque de marbre, Eemans gardait les fichiers qu’il avait composés pour rédiger cette œuvre encyclopédique. Toutefois, il n’en parlait guère. Il m’a toujours semblé que la rédaction de ces ouvrages d’art appartenait pour lui à un passé bien révolu, pourtant plus récent que l’aventure de la revue « Hermès », qui ne cessait de le hanter. J’aurais voulu qu’il m’en parle davantage car j’aurais aimé connaître le lien qui existait entre cette peinture et ces avant-gardes et les positions évoliennes qu’il défendait fin des années 70, début des années 80. J’aurais aimé connaître les étapes de la maturation intellectuelle d’Eemans, selon une chronologie bien balisée : je suis malheureusement resté sur ma faim. Apparemment, il n’avait pas envie de répéter inlassablement l’histoire des aventures intellectuelles qu’il avait vécues dans les années 10, 20 et 30 du 20ème siècle, et dont les protagonistes étaient presque tous décédés. Au cours de nos conversations, il rappelait que, comme bon nombre de dadaïstes autour de Tzara et de surréalistes autour de Breton, il avait eu son « trip » communiste et qu’il avait réalisé un superbe portrait de Lénine, dont il m’a plusieurs fois montré une vignette. Il a également évoqué un voyage à Londres pour aller soutenir des artistes anglais avant-gardistes, hostiles à Marinetti, venu exposer ses thèses futuristes et machinistes dans la capitale britannique : le culte des machines, disaient ces Anglais, était le propre d’un excité venu d’un pays non industriel, sous-développé, alors que tout avant-gardiste anglais se devait de dénoncer les laideurs de l’industrialisation, qui avait surtout frappé le centre géographique de la vieille Angleterre.

L’influence décisive d’un professeur du secondaire

Eemans évoquait aussi le wagnérisme de son frère Nestor, un wagnérisme hérité d’un professeur de collège, le germaniste Maurits Brants (1853-1940). Brants, qui avait décoré sa classe de lithographies et de chromos se rapportant aux opéras de Wagner, fut celui qui donna à l’adolescent Marc. Eemans le goût de la mythologie, des archétypes et des racines. Pour le Prof. Piet Tommissen, biographe d’Eemans, ce dernier serait devenu un « surréaliste pas comme les autres », du moins dans le landerneau surréaliste belge, parce qu’il avait justement, au fond du cœur et de l’esprit, cet engouement tenace pour les thèmes mythologiques. Tommissen ajoute qu’Eemans a été marqué, très jeune, par la lecture des dialogues de Platon, de Spinoza et puis des romantiques anglais, surtout Shelley ; comme beaucoup de jeunes gens immédiatement après 1918, il sera également influencé par l’Indien Rabindranath Tagore, lequel, soit dit en passant, était vilipendé dans les colonnes de la « Revue Universelle » de Paris, comme faisant le lien entre les mondes non occidentaux (et donc non « rationnels ») et le mysticisme pangermaniste d’un Hermann von Keyserlinck, dérive actualisée du romantisme fustigé par Charles Maurras.

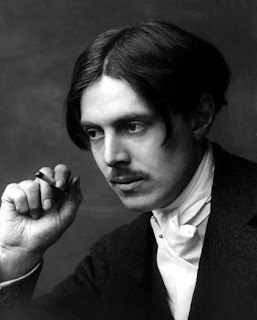

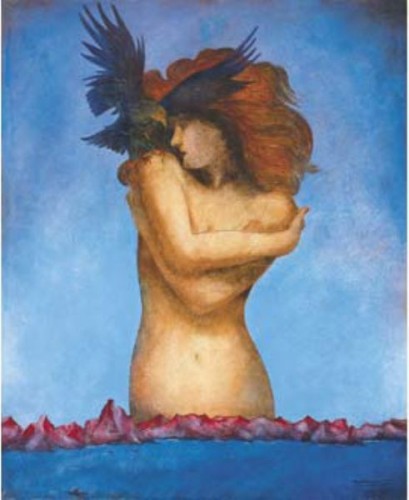

Eemans a souvent revendiqué les influences néerlandaises (hollandaises et flamandes) sur son propre itinéraire intellectuel, dont Louis Couperus et Paul Van Ostaijen. Ce dernier, rappelle fort opportunément Tommissen, avait élaboré un credo poétique, où il distinguait entre la « poésie subconsciemment inspirée » (et donc soumise au pouvoir des mythes) et la « poésie consciemment construite » ; Van Ostaijen appelait ses éventuels disciples futurs à étudier la véritable littérature du peuple thiois des Grands Pays-Bas en commençant par se plonger dans leurs auteurs mystiques. Injonction que suivra le jeune Eemans, qui, de ce fait, se place, à son corps défendant, en porte-à-faux avec un surréalisme cultivant la provocation de « manière consciente et construite » ou ne demeurant, à ses yeux, que « conscient » et « construit ». A l’instigation surtout du deuxième manifeste surréaliste d’André Breton, lancé en 1929, un an après le décès de Van Ostaijen, Eemans explorera d’autres pistes que les surréalistes belges, dont Magritte, ce qui, au-delà des querelles entre personnes et au-delà des clivages politiques/idéologiques, consommera une certaine rupture et expliquera l’affirmation, toujours répétée d’Eemans, qu’il est, lui, un véritable surréaliste dans l’esprit du deuxième manifeste de Breton —qui évoque le poète romantique allemand Novalis— et que les autres n’en ont pas compris la teneur et n’ont pas voulu en adopter les injonctions implicites. Si l’étape abstraite de la « plastique pure » a été une nécessité, une sorte d’hygiène pour sortir des formes stéréotypées et trop académiques de la peinture de la fin du 19ème siècle, le surréalisme ne doit pas se complaire définitivement dans cette esthétique-là. Il doit, comme le préconisait Breton, s’ouvrir à d’autres horizons, jugés parfois « irrationnels ».

Quand Sœur Hadewych hérisse les surréalistes installés

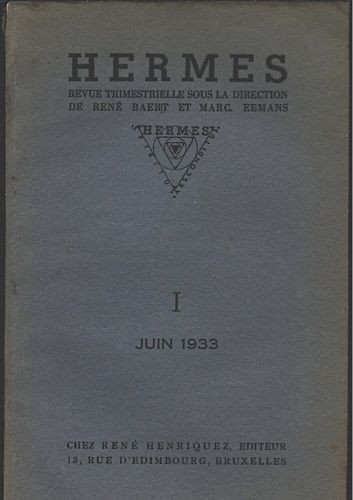

Fidèle au credo poétique de Van Ostaijen (photo ci-dessus), Eemans s’était plongé, fin des années 20, dans l’œuvre mystique de Sœur Hadewych (13ème siècle), dont il lira des extraits lors d’une réunion de surréalistes à Bruxelles. L’accueil fut indifférent sinon glacial ou carrément hostile : pour Tommissen, c’est cette soirée consacrée à la grande mystique flamande du moyen âge qui a consommé la rupture définitive entre Eemans et les autres surréalistes de la capitale belge, dont Nougé, Magritte et Scutenaire. Toute l’animosité, toutes les haines féroces qui harcèleront Eemans jusqu’à sa mort proviennent, selon Tommissen, de cette volonté du jeune peintre de faire franchir au surréalisme bruxellois une limite qu’il n’était pas prédisposé à franchir. Pour les tenants de ce surréalisme considéré par Eemans comme « fermé », le jeune peintre de Termonde basculait dans le mysticisme et les bondieuseries, abandonnait ainsi le cadre soi-disant révolutionnaire, communisant, du surréalisme établi : Eemans tombait dès lors, à leurs yeux, dans la compromission (qui chez les surréalistes conduit automatiquement à l’exclusion et à l’ostracisme) et dans l’idéalisme magique ; il trahissait aussi la « révolution surréaliste » avec son adhésion plus ou moins formelle et provocatrice à l’Internationale stalinienne. Pour Eemans, les autres restaient campés sur des positions figées, infécondes, non inspirées par la notion d’Amour selon Dante (à ce propos, cf. notre « Hommage à Marc. Eemans sur http://marceemans.wordpress.com/ ). Pour poursuivre leur œuvre de contestation du monde moderne (ou monde bourgeois), les surréalistes, selon Eemans, doivent obéir à une suggestion (diffuse, lisible seulement entre les lignes) de Breton : occulter le surréalisme et s’ouvrir à des sciences décriées par le positivisme bourgeois du 19ème siècle. Breton, en 1929, en appelle à la notion d’Amour, telle que l’a chantée Dante. La voie d’Eemans est tracée : il sera le disciple de Van Ostaijen et du Breton du deuxième manifeste surréaliste de 1929. Pour concrétiser cette double fidélité, il fonde avec René Baert la revue « Hermès ».

Le surréalisme y est « occulté », comme le demandait Breton, mais non abjuré dans sa démarche de fond et sa revendication primordiale, qui est de contester et de détruire le bourgeoisisme établi, et s’ouvre aux perspectives de Dante et de la mystique médiévale néerlandaise et rhénane. Cette situation générale du surréalisme français (et francophone) est résumée succinctement par André Vielwahr, spécialiste de ce surréalisme et professeur de français à la Fordham University de New York : « Le surréalisme éprouvait depuis plusieurs années des difficultés insolubles. Il sombrait sans majesté dans le poncif. L’écriture automatique, l’activité onirique s’étaient soldées par un supplément de ‘morceaux de bravoure ‘ destinés à relever les œuvres où ils se trouvaient sans jamais fournir la clé ‘capable d’ouvrir indéfiniment cette boîte à multiple fond qui s’appelle l’homme » (in : S’affranchir des contradictions – André Breton de 1925 à 1930, L’Harmattan, Paris, 1998, p.339). Aller au-delà des poncifs et trouver le clé (traditionnelle) qui permet de découvrir l’homme dans sa prolixité kaléidoscopique de significations et de le sortir de toute l’unidimensionnalité en laquelle l’enferme la modernité a été le vœu d’Eemans. Qui fut sans doute, à son corps défendant, l’exécuteur testamentaire de Pierre Drieu la Rochelle qui écrivait le 1 août 1925 une lettre à Aragon pour déplorer la piste empruntée par le mouvement surréaliste : Drieu reconnaissait que les surréalistes avaient eu , un moment, le sens de l’absolu, « que leur désespoir avait sonné pur », mais qu’ils avaient renié leur intransigeance et, surtout, qu’ils « avaient rejoint des rangs » et n’étaient pas « partis à la recherche de Dieu » (A. Vielwahr, op. cit., pp. 66-67). Aragon avait reproché à Drieu que s’être laissé influencé par les gens d’Action Française, qui étaient, disait-il, « des crapules ». En quémandant humblement la lecture des écrits mystiques de Sœur Hadewych, Eemans, jeune et candide, s’alignait peu ou prou sur les positions de Drieu, qu’il ne connaissait vraisemblablement pas à l’époque, des positions qui avaient hérissé les « partisans alignés du surréalisme des poncifs ». Notons qu’Eemans travaillera sur les rêves et sur l’écriture automatique, notamment à proximité d’Henri Michaux, qui sera, un moment, le secrétaire de rédaction d’ « Hermès ». Il reste encore à tracer un parallèle entre la démarche d’Eemans et celles d’Antonin Artaud, Georges Bataille, Michel Leiris et Roger Caillois. Mais c’est là un travail d’une ampleur considérable…

Eemans m’a souvent parlé de sa revue des années 30, « Hermès ». Il en possédait encore une unique collection complète. « Hermès » était une revue de philosophie, axée sur les alternatives au rationalisme et au positivisme modernes, dans une perspective apparemment traditionnelle ; en réalité, elle recourrait sans provocation à des savoirs fondamentalement différents de ceux qui structuraient un présent moderne sans relief et, partant, elle présentait des savoirs qui étaient beaucoup plus radicalement subversifs que les provocations dadaïstes ou les gestes des surréalistes établis : pour être un révolutionnaire radical, il fallait être un traditionnaliste rigoureux, frotté aux savoirs refoulés par la sottise moderne. « Hermès » voulait sortir du « carcan occidental » que dénonçaient tout à la fois les surréalistes et les traditionalistes, mais en abandonnant les postures provocatrices et en se plongeant dans les racines oubliées de traditions pouvant offrir une véritable alternative. Pour trouver une voie hors de l’impasse moderne, Eemans avait sollicité une quantité d’auteurs mais l’originalité première d’ « Hermès », dans l’espace linguistique francophone, a été de se pencher sur les mystiques médiévales flamandes et rhénanes. De tous ses articles dans « Hermès » sur Sœur Hadewych, sur Ruysbroeck l’Admirable, etc., Eemans avait composé un petit volume. Mais, malheureusement, il n’a plus vraiment eu le temps d’explorer cette veine, ni pendant la guerre ni après le conflit. Il faudra attendre les ouvrages du Prof. Paul Verdeyen (formé à la Sorbonne et professeur à l’Université d’Anvers) et de Geert Warnar (1) et celui, très récent, de Jacqueline Kelen sur Sœur Hadewych (2) pour que l’on dispose enfin de travaux plus substantiels pour relancer une étude générale sur cette thématique. Notons au passage qu’une exploration simultanée de la veine mystique flamande/brabançonne, jugée non hérétique par les autorités de l’Eglise, et des idées de « vraie religion » de l’Europe et d’ « unitarisme » chez Sigrid Hunke, qui, elle, réhabilitait bon nombre d’hérétiques, pourrait s’avérer fructueuse et éviter des dichotomies trop simplistes (telles paganisme/catholicisme ou renaissancisme/médiévisme, etc. empêchant de saisir la véritable « tradition pérenne », s’exprimant par quantité d’avatars).

Mystique flamando-rhénane et matière de Bourgogne

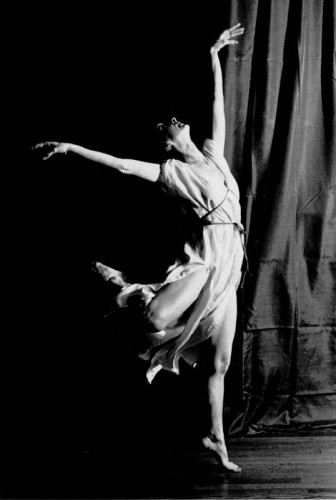

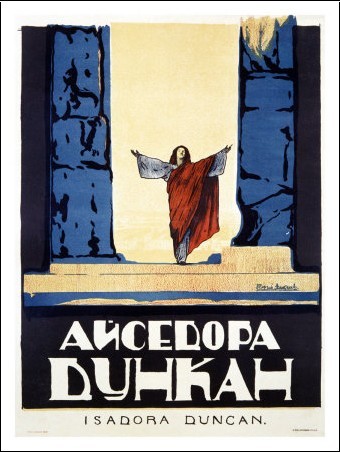

Dans l’entre-deux-guerres, l’exploration de la veine mystique flamando-rhénane, entreprise parallèlement à la redécouverte de l’héritage bourguignon, avait un objectif politique : il fallait créer une « mystique belge », non détachée du tronc commun germanique (que l’on qualifiait de « rhénan » pour éviter des polémiques ou des accusations de « germanisme » voire de « pangermanisme ») et il fallait renouer avec un passé non inféodé à Paris tout en demeurant « roman ». Les tâtonnements ou les ébauches maladroites, bien que méritoires, de retrouver une « mystique belge », chez un Raymond De Becker ou un Henry Bauchau, trop plongés dans les débats politiques de l’époque, nous amènent à poser Eemans, aujourd’hui, comme le seul homme, avec son complice René Baert, qui ait véritablement amorcé ce travail nécessaire. Autre indice : la collaboration très régulière à « Hermès » du philosophe Marcel Decorte (Université de Liège) qui donnait aussi des conférences à l’école de formation politique de De Becker et Bauchau dans les années 1937-39. Le lien, probablement ténu, entre Decorte, Eemans, Bauchau et De Becker n’a jamais été exploré : une lacune qu’il s’agira de combler. Les travaux sur l’héritage bourguignon ont été plus abondants dans la Belgique des années 30 (Hommel, Colin, etc.), sans qu’Eemans ne s’en soit mêlé directement, sauf, peut-être, par l’intermédiaire de la chorégraphe Elsa Darciel, disciple des grandes chorégraphes de l’époque dont l’Anglaise Isadora Duncan. Elsa Darciel avait entrepris de faire renaître les danses des « fastes de Bourgogne ». Malheureusement, ni l’un ni l’autre ne sont encore là pour témoigner de cette époque, où ils ont amorcé leurs recherches, ni pour évoquer le vaste contexte intellectuel où les cénacles conservateurs belges et ceux du mouvement flamand cherchaient fébrilement à se doter d’une identité bien charpentée, qui ne pouvait bien sûr pas se passer d’une « mystique » solide. Sur l’Internet, les esprits intéressés découvriront une étude substantielle du Prof. Piet Tommissen sur la personne d’Elsa Darciel, notamment sur ses relations sentimentales avec le dissident américain Francis Parker Yockey, alias Ulrick Varange.

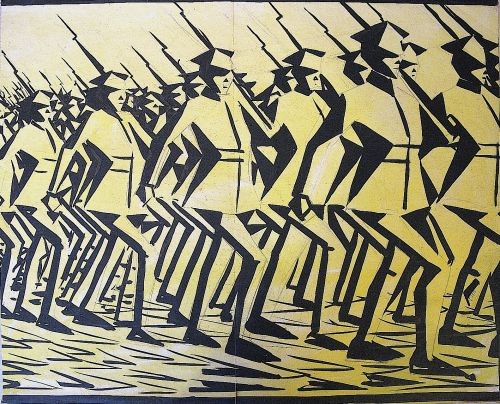

Pendant la seconde guerre mondiale, Eemans a eu des activités de « journaliste culturel ». Cette position l’a amené à écrire quantité de critiques d’art dans la presse inféodée à ce qu’il est désormais convenu d’appeler la « collaboration », phénomène qui, rétrospectivement, ne cesse d’empoisonner la politique belge depuis la fin de la seconde guerre mondiale. On ne cesse de reprocher à Marc. Eemans et à René Baert la teneur de leurs articles, sans que ceux-ci n’aient réellement été examinés et étudiés dans leur ensemble, sous toutes leurs facettes et dans toutes leurs nuances (repérables entre les lignes) : Eemans se défend en rappelant qu’il a combattu, au sein d’un « Groupe des Perséides », la politique artistique que le IIIe Reich cherchait à imposer dans tous les pays d’Europe qu’il occupait. Cette politique était hostile aux avant-gardes, considérées comme « art dégénéré ». Eemans racontait aux censeurs nationaux-socialistes qu’il n’y avait pas d’ « art dégénéré » en Belgique, mais un « art populaire », expression de l’âme « racique » (le terme est de Charles de Coster et de Camille Lemonnier), qui, au cours des quatre premières décennies du 20ème siècle, avait pris des aspects certes modernistes ou avant-gardistes, mais des aspects néanmoins particuliers, originaux, car, in fine, l’identité des « Grands Pays-Bas » résidait toute entière dans son génie artistique, un génie que l’on pouvait qualifier de « germanique », donc, aux yeux des nouvelles autorités, de « positif », les artistes d’avant-garde dans ces « Grands Pays-Bas » étant tous des hommes et des femmes du cru, n’appartenant pas à une quelconque population « nomade », comme en Europe centrale. La « bonne » nature vernaculaire de ces artistes, en Flandre, ne permettait à personne de déduire de leurs œuvres une « perversité » intrinsèque : il fallait donc les laisser travailler, pour que puisse éclore une facette nouvelle de « ce génie germanique local et particulier ». L’énoncé de telles thèses, sans doute partagées par d’autres analystes collaborationnistes des avant-gardes, comme Paul Colin ou Georges Marlier, avait pour but évident d’entraver le travail d’une censure qui se serait avérée trop sourcilleuse. Finalement, on reprochera surtout à Eemans et à Baert d’avoir rédigé des articles pour le « Pays Réel » de Léon Degrelle. Baert assassiné en 1945, Eemans reste le seul larron du tandem en piste après la guerre. Il sera arrêté pour sa collaboration au « Pays Réel » et non pour d’autres motifs, encore moins pour le contenu de ses écrits (même s’ils portaient souvent la marque indélébile de l’époque). « Je faisais partie de la charrette du ‘Pays Réel ‘ », disait-il souvent. Après la fin des hostilités, après la levée de l’état de guerre en Belgique (en 1951 !), après son incarcération qui dura quatre années au « Petit Château », Eemans revient dans le peloton de tête des critiques d’art en Belgique : ses « crimes » n’ont probablement pas été jugés aussi « abominables » car le préfacier de l’un de ses ouvrages encyclopédiques majeurs fut Philippe Roberts-Jones, Conservateur en chef des Musées royaux d’art de Belgique, fils d’un résistant ucclois mort, victime de ses ennemis, pendant la seconde grande conflagration intereuropéenne.

« Hamer », Farwerck et De Vries

Sous le IIIe Reich, les autorités allemandes ont fondé une revue d’anthropologie, de folklore et d’études populaires germaniques, intitulée « Hammer » (« Le Marteau », sous-entendu le « Marteau de Thor »). Pendant l’été 1940, on décide, à Berlin, de créer deux versions supplémentaires de « Hammer » en langue néerlandaise, l’une pour la Flandre et l’autre pour les Pays-Bas (« Hamer »). Quand on parle de néopaganisme aujourd’hui, surtout si l’on se réfère à l’Allemagne nationale-socialiste ou aux innombrables sectes vikingo-germanisantes qui pullulent aux Etats-Unis ou en Grande-Bretagne, tout en influençant les groupes musicaux de hard rock, cela fait généralement sourire les philologues patentés. Pour eux, c’est, à juste titre, du bric-à-brac sans valeur intellectuelle aucune. C’est d’ailleurs dans ce sens qu’Eemans adoptera les thèses d’Evola consignées, de manière succincte, dans un article titré « Le malentendu du néopaganisme ». Mais ce reproche ne peut nullement être adressé aux versions allemande, néerlandaise et flamande de « Hammer/Hamer ». Des germanistes de notoriété internationale comme Jan De Vries, auteur des principaux dictionnaires étymologiques de la langue néerlandaise (tant pour les noms communs que pour les noms propres, notamment les noms de lieux) ont participé à la rédaction de cet éventail de revues. Eemans était l’un des correspondants de « Hamer »/Amsterdam à Bruxelles. Cela lui permettait de faire la navette entre Bruxelles et Amsterdam pendant le conflit et de s’immerger dans la culture littéraire et artistique de la Hollande, qu’il adorait. Il est certain que l’on a rédigé et édité des études sur « Hammer » en Allemagne ou en Autriche, du moins sur sa version allemande ou sur certains de ses principaux rédacteurs. Je ne sais pas si une étude simultanée des trois versions a un jour été établie. C’est un travail qui mériterait d’être fait. D’autant plus que la postérité de « Hamer »/Amsterdam et « Hamer »/Bruxelles n’a certainement pas été entravée par une quelconque vague répressive aux Pays-Bas après la défaite du IIIe Reich. De Vries est demeuré un germaniste néerlandais, un « neerlandicus », de premier plan, ainsi qu’un explorateur inégalé du monde des sagas islandaises. Son œuvre s’est poursuivie, de même que celle de Farwerck, que l’on n’a commencé à dénoncer qu’à la fin des années 90 du 20ème siècle ! De l’écolier de Termonde influencé par Brants, son professeur wagnérien, du cadet de famille influencé par Nestor, son aîné, autre Wagnérien, au disciple attentif de Van Ostaijen et du lecteur scrupuleux du deuxième manifeste surréaliste de Breton au directeur d’Hermès et au rédacteur de « Hamer », du réprouvé de 1944 au fondateur du « Centro Studi Evoliani » et au collaborateur d’ « Antaios » de Christopher Gérard, il y a un fil conducteur parfaitement discernable, il y a une fidélité inébranlable et inébranlée à soi et à ses propres démarches, face à l’incompréhension généralisée qui s’est bétonnée et a orchestré le boycott de cet homme à double casquette : celle du dadaïste-surréaliste-lénino-trostkiste et celle du wagnéro-mystico-évoliano-traditionaliste. Et pourtant, il y a, derrière cette apparente contradiction une formidable cohérence que sont incapables de percevoir les esprits bigleux. Ou pour être plus précis : il y a chez Eemans, surréaliste et traditionaliste tout à la fois, une volonté d’aller au « lieu » impalpable où les contradictions s’évanouissent. Un lieu que cherchait aussi Breton dès son second manifeste.

Après la guerre, Eemans participe à la revue « Fantasmagie » ; l’étude de « Fantasmagie » mérite, à elle seule, un bon paquet de pages. L’objectif de « Fantasmagie » était de faire autre chose que de l’art bétonné en une nouvelle orthodoxie, qui tenait alors le haut du pavé, après avoir balayé toute interrogation métaphysique. Dans les colonnes de « Fantasmagie », les rédacteurs vont commenter et valoriser toutes les œuvres fantastiques, ou relevant d’une forme ou d’une autre d’ « idéalisme magique ». On notera, entre bien d’autres choses, un intérêt récurrent pour les « naïfs » yougoslaves. Quant à Eemans, il se chargeait de la recension de livres, notamment ceux de Gaston Bachelard. Je compte bien relire les exemplaires de « Fantasmagie » qui figurent dans ma bibliothèque mais je n’écrirai de monographie sur cette revue, ou sur l’action et l’influence d’Eemans au sein de sa rédaction, que lorsque j’aurai dûment complété ma collection, encore assez lacunaire.

Harcèlement et guéguerre entre surréalistes

L’après-guerre est tout à la fois paradis, purgatoire et enfer pour Eemans. Dans le monde de la critique d’art, il occupe une place non négligeable : son érudition est reconnue et appréciée. En Flandre, on ne tient pas trop compte des allusions perfides à sa collaboration au « Pays Réel » et à « Hamer ». En revanche, dans l’univers des galeries huppées, des expositions internationales, des colloques spécifiques au surréalisme en Belgique et à l’étranger, un boycott systématique a été organisé contre sa personne : manifestement, on voulait l’empêcher de vivre de sa peinture, on voulait lui barrer la route du succès « commercial », pour le maintenir dans la géhenne du travail d’encyclopédiste ou dans l’espace marginal de « Fantasmagie ». Son adversaire le plus acharné sera l’avocat Paul Gutt (1941-2000), fils du ministre des finances du cabinet belge en exil à Londres pendant la seconde guerre mondiale. En 1964, Paul Gutt organise un chahut contre deux conférences d’Eemans en diffusant un pamphlet en français et en néerlandais contre notre surréaliste mystique et traditionaliste, intitulé « Un ton plus bas ! Een toontje lager ! » et qui rappelait bien entendu le « passé collaborationniste » du conférencier. Le même Paul Gutt s’était aussi attaqué au MAC (« Mouvement d’Action Civique ») de Jean Thiriart, futur animateur du mouvement « Jeune Europe », en distribuant un autre pamphlet, intitulé, lui, « Haut les mains ! ». En 1973, Eemans intente un procès, qu’il perdra, à Marcel Mariën qui, à son tour, pour participer allègrement à la curée et traduire dans la réalité bruxelloise les principes de la « révolution culturelle » maoïste qu’il admirait, avait rappelé le « passé incivique » de Marc. Eemans. L’avocat de Mariën était Paul Gutt. En 1979, dans son livre sur le surréalisme belge, qui fait toujours référence, Marcel Mariën, pour se venger, exclut totalement le nom de Marc. Eemans de son gros volume mais encourt simultanément, mais pour d’autres motifs, la colère de Georgette Magritte et d’Irène Hamoir, ancienne amie d’Eemans et veuve du surréaliste « marxiste pro-albanais » (poncif !) Louis Scutenaire. Marcel Mariën ne s’en prenait pas qu’à Eemans quand il évoquait l’époque de la seconde occupation allemande : dans ses souvenirs, publiés en 1983 sous le titre de « Radeau de la mémoire », il accuse Magritte d’avoir fabriqué dans ses caves de faux Braque et de faux Picasso, « pour faire bouillir la marmite »…. ! Plus tard, en 1991, le provocateur patenté Jan Bucquoy brûlera une peinture de Magritte lors d’un « happening », pour fustiger le culte, à son avis trop officiel, que lui voue la culture dominante en Belgique. On le voit : le petit monde du surréalisme en Belgique a été une véritable pétaudière, un « panier à crabes », disait Eemans, qui ne cessait de s’en gausser.

Q. : Mais existe-t-il une postérité « eemansienne » ? Que reste-t-il de ce travail effectué avant et après la création du « Centro Studi Evoliani » de Bruxelles ?

RS : Eemans était désabusé, en dépit de sa joie de vivre. Il était un véritable pessimiste : joyeux dans la vie quotidienne mais sans illusion sur le genre humain. Cette posture s’explique aisément en ce qui le concerne : ses efforts d’avant-guerre pour réanimer une mystique flamando-rhénane, pour réinjecter de l’Amour selon Dante dans le monde, pour faire retenir les leçons de Sohrawardi le Perse, n’ont été suivi d’aucuns effets immédiats. De bons travaux ont été indubitablement réalisés par quantité de savants sur ces thématiques, qui lui furent chères, mais seulement, hélas, au soir de sa vie, sans qu’il ait pu prendre connaissance de leur existence, ou après sa mort, survenue le 28 juillet 1998. L’assassinat par les services belges de son ami René Baert, dans les faubourgs de Berlin fin 1945, l’a profondément affecté : il en parlait toujours avec un immense chagrin au fond de la gorge. Un embastillement temporaire et des interdictions professionnelles ont mis un terme à l’œuvre d’Elsa Darciel, qui n’aurait plus suscité le moindre intérêt après guerre, comme tout ce qui relève de la matière de Bourgogne (à la notable exception du magnifique « Je soussigné, Charles le Téméraire, Duc de Bourgogne » de Gaston Compère). Eemans s’est plongé dans son travail d’encyclopédiste de l’histoire de l’art en Belgique et dans « Fantasmagie », terrains jugés « neutres ». Ces territoires, certes fascinants, ne permettaient pas, du moins de manière directe, de bousculer les torpeurs et les enlisements dans lesquels végétaient les provinces flamandes et romanes de Belgique. Car on sentait bien qu’Eemans voulait bousculer, que « bousculer » était son option première et dernière depuis les journées folles du dadaïsme et du surréalisme jusqu’aux soirées plus feutrées (mais nettement moins intéressantes, époque de médiocrité oblige…) organisées par le « Centro Studi Evoliani ». Eemans avait en effet bousculé la bien-pensance comme les garçons de son époque, avec les foucades dadaïstes et surréalistes, auxquelles Evola lui-même avait participé en Italie. Comme Evola, il a cherché une façon plus solide de bousculer les fadeurs du monde moderne : pour Evola, ce furent successivement le recours à l’Inde traditionnelle (Doctrine de l’Eveil, Yoga tantrique, etc.) et au Tao Te King chinois ; pour Eemans, ce fut le recours à la mystique flamando-rhénane, destinée à secouer le bourgeoisisme matérialiste belge, qui n’avait pas voulu entendre les admonestations de ses écrivains et poètes d’avant 1914, comme Camille Lemonnier ou Georges Eeckhoud, et s’était empressé d’abattre bon nombre de joyaux de l’architecture « Art Nouveau » d’Horta et de ses disciples, jugeant leurs audaces créatrices peu pratiques et trop onéreuses à entretenir ! Eemans aimait dire qu’il était le véritable disciple d’André Breton, dans la mesure où celui-ci avait un jour déclaré qu’il fallait s’allier, si l’opportunité se présentait, « avec le Dalaï Lama contre l’Occident ». Pour Evola comme pour Eemans, on peut affirmer, sans trop de risque d’erreur, que le « Dalaï Lama » évoqué par Breton, n’est rien d’autre qu’une métaphore pour exprimer nostalgie et admiration pour les valeurs anté-modernes, donc non occidentales, non matérialistes, qu’il convenait d’étudier, de faire revivre dans l’âme des intellectuels et des poètes les plus audacieux.

Le « Centro Studi Evoliani » : la déception

Une fois son travail d’encyclopédiste achevé auprès de l’éditeur Meddens, Eemans voulait renouer avec cette audace du « bousculeur » dadaïste, en s’arc-boutant sur le terrain d’action prestigieux que constituait l’espace de réflexion évolien, et en provoquant les contemporains en reliant à l’évolisme de la fin des années 70 ses propres recherches entreprises dans les années 30 et pendant la seconde guerre mondiale. Il a été déçu. Et a exprimé cette déception dans l’entretien qu’il nous a accordé, je veux dire à Koenraad Logghe et à moi-même (et que l’on peut lire un peu partout sur l’Internet, notamment sur http://euro-synergies.hautetfort.com et sur http://www.centrostudilaruna.it , le site du Dr. Alberto Lombardo). Pourquoi cette déception ? D’une part, parce que la jeune génération ne connaissait plus rien des enthousiasmes d’avant-guerre, ne faisait pas le lien entre les avant-gardes des années 20 et le recours d’Evola, Guénon, Corbin, Eemans, etc. à la « Tradition », n’avait reçu dans le cadre de sa formation scolaire aucun indice capable de l’éveiller à ces problématiques ; d’autre part, l’espace ténu des évoliens était dans le collimateur de la nouvelle bien-pensance gauchiste, qui étrillait aussi Eemans quand elle le pouvait (alors qu’on lui avait foutu royalement la paix dans les années 50 et 60). Etre dans le collimateur de ces gens-là peut être une bonne chose, être indice de valeur face aux zélotes furieux qui propagent toutes les « anti-valeurs » possibles et imaginables mais cela peut aussi conduire à attirer vers les cercles évoliens des personnalités instables, politisées, simplificatrices, que la complexité des questions soulevées rebute et lasse. En outre, toute une propagande médiatisée a diffusé dans la société une fausse « spiritualité de bazar », où l’on mêle allègrement toute une série d’ingrédients comme le bouddhisme californien, la cruauté gratuite, le nazisme tapageur, l’occultisme frelaté, le monachisme tibétain, la runologie spéculative, etc. pour créer des espaces de relégation vers lesquelles on houspille trublions et psychopathes, les rendant ainsi aisément identifiables, criminalisables ou, pire encore, dont on peut se gausser à loisir (exemple : « extrême-droite » = « extrême-druides », intitulé tapageur d’une émission de la RTBF). Sans compter les agents provocateurs de tous poils qui font occasionnellement irruption dans les cercles non-conformistes et cherchent à prouver qu’on est en train de ressusciter des « ordres occultes », préparant le retour de la « bête immonde ».

Eemans, âgé de 71 ans quand il lance le « Centro Studi Evoliani » de Bruxelles, n’avait nulle envie de répéter à satiété le récit des phases de son itinéraire antérieur face à un public disparate qui était incapable de faire le lien entre monde des arts et écrits traditionalistes ; ensuite, lui qui avait connu une revue de qualité dans le cadre du « national-socialisme » des années 40, comme « Hammer », n’avait nulle envie d’inclure dans ses préoccupations les fabrications anglo-saxonnes qui lancent dans le commerce sordide des marottes soi-disant « transgressives » un « occultisme naziste de Prisunic ». Il a décidé de mettre un terme aux activités du « Centro Studi Evoliani », car celui-ci ne pouvait pas, via l’angle évolien, ressusciter l’esprit d’ « Hermès », faute d’intéressés compétents. Une « Fondation Marc. Eemans » prendra le relais à partir de 1982, dirigée par Jan Améry. Elle existe toujours et est désormais relayée par un site basé aux Pays-Bas (http://marceemans.wordpress.com/), qui affiche les textes d’Eemans et sur Eemans dans leur langue originale (français et néerlandais). Au début des années 80, toutes mes énergies ont été consacrées à la nouvelle antenne néo-droitiste « EROE » (« Etudes, Recherches et Orientations Européennes »), fondée par Jean van der Taelen, Guibert de Villenfagne de Sorinnes et moi-même en octobre 1983, quasiment le lendemain de ma démobilisation (2 août), de mon premier mariage (25 août & 3 septembre) et de la défense de mon mémoire (vers le 10 septembre).

La réception d’Evola en pays flamand est surtout due aux efforts des frères Logghe : Peter Wim, l’aîné, et Koenraad, le cadet. Peter Wim Logghe, au départ juriste dans une compagnie d’assurances, a fait connaître, de manière succincte et didactique, l’œuvre d’Evola dans plusieurs organes de presse néerlandophones, dont « Teksten, Kommentaren en Studies », l’organe du GRECE néo-droitiste en Flandre, et a traduit « Orientations » en néerlandais (pour le « Centro Studi Evoliani » d’Eemans). Koenraad Logghe, pour sa part, créera en Flandre un véritable mouvement traditionnel, au départ de sa première revue, « Mjöllnir », organe d’un « Orde der Eeuwige Werderkeer » (OEW) ou « Ordre de l’Eternel Retour ». Allègre et rigoureuse, païenne dans ses intentions sans verser dans un paganisme caricatural et superficiel, cette publication, artisanale faute de moyens financiers, mérite qu’on s’y arrête, qu’on l’étudie sous tous ses aspects, sous l’angle de tous les thèmes et figures abordés (essentiellement le domaine germanique/scandinave, l’Edda, Beowulf, etc. , dans la ligne de « Hamer » et du grand philologue néerlandais Jan de Vries ; une seule étude sur Evola y a été publiée dans les années 1983-85, sur « Ur & Krur » par Manfred van Oudenhove). Koenraad Logghe fondera ensuite le groupe « Traditie », suite logique de son OEW, avant de s’en éloigner et de poursuivre ses recherches en solitaire, couplant l’héritage traditionnel de Guénon essentiellement, à celui du Néerlandais Farwerck et aux recherches sur la symbolique des objets quotidiens, des décorations architecturales, des pierres tombales, etc., une science qui avait intéressé Eemans dans le cadre de la revue « Hamer », dont les thèmes ne seront nullement rejetés aux Pays-Bas et en Flandre après 1945 : de nouvelles équipes universitaires, formées au départ par les rédacteurs de « Hamer » continuent leurs recherches. Dans ce contexte, Koenraad Logghe publiera plusieurs ouvrages sur cette symbolique du quotidien, qui feront tous autorité dans l’espace linguistique néerlandais.

Eemans participera également à la revue « Antaios » que Christopher Gérard avait créée au début des années 90. Il avait repris le titre d’une revue fondée par Ernst Jünger et Mircea Eliade en 1958. Gérard bénéficiait de l’accord écrit d’Ernst Jünger et en était très fier et très reconnaissant. Lors de la fondation de l’ « Antaios » de Jünger et Eliade, ceux-ci avaient demandé la collaboration d’Eemans : il avait cependant décliné leur offre parce qu’il était submergé de travail. Dommage : la thématique de la mystique flamando-rhénane aurait trouvé dans la revue patronnée par l’éditeur Klett une tribune digne de son importance. Eemans écrivait parfaitement le français et le néerlandais mais non l’allemand. J’ai toujours supposé qu’il n’aurait pas aimé être trahi en étant traduit. C’est donc dans la revue « Antaios » de Christopher Gérard, publiée à Bruxelles/Ixelles, à un jet de pierre de son domicile, qu’Eemans publiera ses derniers textes, sans faiblir ni faillir malgré le poids des ans, jusqu’en ce jour fatidique de la fin juillet 1998, où la Grande Faucheuse l’a emporté.

Personnellement, je n’ai pas suivi un itinéraire strictement évolien après la dissolution du « Centro Studi Evoliani », dans la première moitié des années 80. Eemans m’en a un peu voulu, beaucoup au début des années 80, moins ultérieurement, et finalement, la réconciliation définitive est venue en deux temps : lors de la venue à Bruxelles de Philippe Baillet (pour une conférence à la tribune de l’EROE, chez Jean van der Taelen) puis lorsqu’il m’a invité à des vernissages, surtout celui qui fut suivi d’une magnifique soirée d’hommage, avec dîner somptueux fourni par l’édilité locale, que lui organisa sa ville natale de Termonde (Dendermonde) à l’occasion de ses 85 ans (en 1992). Pourquoi cette animosité passagère à mon égard ? Début 1981, a eu lieu à Bruxelles une conférence sur les thèmes de la défense de l’Europe, organisée conjointement par Georges Hupin (pour le GRECE-Belgique) et par Rogelio Pete (pour le compte d’une structure plus légère et plus éphémère, l’IEPI ou « Institut Européen de Politique Internationale »).

La rencontre Eemans/de Benoist

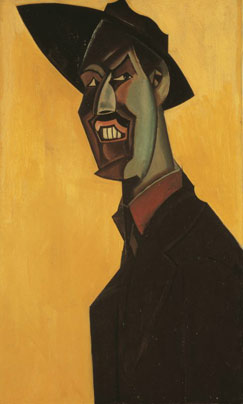

En marge de cette initiative, où plusieurs personnalités prirent la parole, dont Alain de Benoist, l’excellent et regretté Julien Freund, le Général Robert Close (du Corps des blindés belges stationnés en RFA), le Colonel Marc Geneste (l’homme de la « bombe à neutrons » au sein de l’armée française), le Général Pierre M. Gallois et le Dr. Saul Van Campen (Directeur du cabinet du Secrétaire Général de l’OTAN), j’avais vaguement organisé, en donnant deux ou trois brefs coups de fil, une rencontre entre Marc. Eemans et Alain de Benoist dans les locaux de la Librairie de Rome, dans le goulot de l’Avenue Louise, à Bruxelles, sans pouvoir y être présent moi-même (3). Visiblement, l’intention d’Eemans était de se servir de la revue d’Alain de Benoist, « Nouvelle école », dont j’étais devenu le secrétaire de rédaction, pour relancer les thématiques d’ « Hermès ». A l’époque, malgré quelques rares velléités évoliennes, Alain de Benoist n’était guère branché sur les thématiques traditionalistes ; il snobait délibérément Georges Gondinet, qualifié de « petit con qui nous insulte » (remarquez le « pluriel majestatif »…), tout simplement parce que le directeur de « Totalité » avait couché sur le papier quelques doutes quant à la pertinence métapolitique des écrits du « Pape » de la ND, marqués, selon le futur directeur des éditions Pardès, de « darwinisme ». De Benoist reprochait surtout à Gondinet et à son équipe la parution du n°11 de « Totalité », un dossier intitulé « La Nouvelle Droite du point de vue de la Tradition ». De Benoist, qui a certes eu des dadas darwiniens, sortait plutôt d’un « trip » empiriste logique, de facture anglo-saxonne et « russellienne », dont on ne saisit guère l’intérêt au vu de ses errements ultérieurs. Il tâtait maladroitement du Heidegger et voulait écrire sur le philosophe souabe un article qui attesterait de son génie dans toutes les Gaules (on attend toujours ce maître article promis sur le rapport Heidegger/Hölderlin… est germanomane par coquetterie parisienne qui veut, n’est pas germaniste de haut vol qui le prétend…). Sur les avant-gardes dadaïstes et surréalistes, de Benoist ne connaissait rien et classait tout cela, bon an mal an, dans des concepts généraux, dépréciatifs et fourre-tout, tels ceux de l’ « art dégénéré » ou du « gauchisme subversif », car, en cette époque bénie (pour lui et son escarcelle) où il oeuvrait au « Figaro Magazine », le sieur de Benoist se targuait d’appartenir à une bonne bourgeoisie installée, inculte et hostile à toute forme de nouveauté radicale, comme il se targue aujourd’hui d’appartenir à un filon gauchiste, inspiré par le Suisse Jean Ziegler, un filon tout aussi rétif à de la véritable innovation car, selon ses tenants et thuriféraires, il faut demeurer dans la jactance contestatrice habituelle des années 60 (comme certains surréalistes se complaisaient dans la jactance communisante des années 30 et n’entendaient pas en sortir).

En ce jour de mars 1981 donc, Alain de Benoist dédicaçait ses livres dans la Librairie de Rome et Eemans s’y est rendu, joyeux, débonnaire, chaleureux et enthousiaste, à la mode flamande, sans doute après un repas copieux et bien arrosé ou après quelques bon hanaps de « Duvel » : on est au pays des « noces paysannes » de Breughel, du « roi boit » de Jordaens et des plantureuses inspiratrices de Rubens ou on ne l’est pas ! Cette truculence a déplu au « Pape » de la « nouvelle droite », qui prenait souvent, à cette époque qui a constitué le faîte de sa gloire, les airs hautains du pisse-vinaigre parisien (nous dirions de la « Moeijer snoeijfdüüs »), se prétendant détenteur des vérités ultimes qui allaient sauver l’univers du désastre imminent qui l’attendait au tout prochain tournant. Pour de Benoist, la truculence breughelienne d’Eemans était indice de « folie ». Les airs hautains du Parisien, vêtu ce jour-là d’un affreux costume de velours mauve, sale et tout fripé, du plus parfait mauvais goût, étaient, pour le surréaliste flamand, indices d’incivilité, de fatuité et d’ignorance. Bref, la mayonnaise n’a pas pris : on ne marie pas aisément la joie de vivre et la sinistrose. Le courant n’est pas passé entre les deux hommes, éclipsant du même coup, et pour toujours, les potentialités immenses d’une éventuelle collaboration, qui aurait pu approfondir considérablement les recherches du mouvement néo-droitiste, vu que la postérité d’ « Hermès » débouche, entre bien d’autres choses, sur les activités de « Religiologiques » de Gilbert Durand ou sur les travaux d’Henri Corbin sur l’islam persan, et surtout qu’elle aurait pu démarrer tout de suite après l’écoeurante éviction de Giorgio Locchi, germaniste et musicologue, qui avait donné à « Nouvelle école » son lustre initial, éviction qu’Eemans ignorait : les arts et la musique ont de fait été quasiment absents des spéculations néo-droitistes qui ont vite viré au parisianisme jargonnant et « sociologisant » (dixit feu Jean Parvulesco), surtout après la constitution du tandem de Benoist/Champetier à la veille des années 90, tandem qui durera un peu moins d’une douzaine d’années.

La brève entrevue entre le « Pape » de la « nouvelle droite » et Eemans, à la « Librairie de Rome » de Bruxelles, n’a donc rien donné : un nouveau dépit pour notre surréaliste de Termonde, qui, une fois de plus, s’est heurté à des limites, à des lacunes, à une incapacité de clairvoyance, de lungimiranza, chez un individu qui s’affichait alors comme le grand messie de la culture refoulée. Cela a dû rappeler à notre peintre l’incompréhension des surréalistes bruxellois devant son exposé sur Sœur Hadewych…

Eemans m’en a voulu d’être parti, quelques jours plus tard, à Paris pour prendre mon poste de « secrétaire de rédaction » de « Nouvelle école ». Eemans jugeait sans doute que l’ambiance de Paris, vu le comportement malgracieux d’Alain de Benoist, n’était pas propice à la réception de thèmes propres à nos Pays-Bas ou à l’histoire de l’art et des avant-gardes ou encore aux mystiques médiévale et persane ; sans doute a-t-il cru que j’avais mal préparé la rencontre avec le « Pape » de la « nouvelle droite », qu’en ‘audience’ je ne lui avais pas assez parlé d’ « Hermès » ; quoi qu’il en soit, pour l’incapacité à réceptionner de manière un tant soit peu intelligente les thématiques chères à Eemans, notre surréaliste réprouvé avait raison : de Benoist se targue d’être une sorte d’Encyclopaedia Britannica sur pattes, en chair (flasque) et en os, mais il existe force thématiques qu’il ne pige pas, auxquelles il n’entend strictement rien ; de plus, Eemans estimait que « monter à Paris » était le propre, comme il me l’a écrit, furieux, d’un « Rastignac aux petits pieds » : ma place, pour lui, était à Bruxelles, et non ailleurs. Mais, heureusement, mon escapade parisienne, dans l’antre du « snobinard tout en mauve », n’a duré que neuf mois. Revenu en terre brabançonne, je n’ai plus jamais ravivé l’ire d’Eemans. Et c’est juste, la sagesse populaire ne nous enseigne-t-elle pas « Oost West - Thuis best ! » ?

Vienne et Zürich/Frauenfeld

Ma première activité strictement évolienne date de 1998, année du décès de Marc. Eemans. Evola suscitait à l’époque de plus en plus d’intérêt en Allemagne et en Autriche, grâce, notamment, aux efforts du Dr. T. H. Hansen, traducteur et exégète du penseur traditionaliste. Du coup, toutes les antennes germanophones de « Synergies Européennes » voulaient marquer le coup et organiser séminaires et causeries pour le centième anniversaire de la naissance du Maître. Au printemps de 1998, j’ai donc été appelé à prononcer à Vienne, dans les locaux de la « Burschenschaft Olympia », une allocution en l’honneur du centenaire de la naissance d’Evola ; on avait choisi Vienne parce qu’Evola adorait cette capitale impériale et y avait reçu, en 1945, pendant le siège de la ville, l’épreuve doublement douloureuse de la blessure et de la paralysie : un mur s’est effondré, brisant définitivement la colonne vertébrale de Julius Evola. A Vienne, il y avait, à la tribune, le Dr. Luciano Arcella (qui a tracé des parallèles entre Spengler, Frobenius et Evola dans leurs critiques de l’Occident), Martin Schwarz (toujours animateur de sites traditionalistes avec connotation islamisante assez forte), Alexandre Miklos Barti (sur la renaissance évolienne en Hongrie) et moi-même. J’ai essentiellement mis l’accent sur l’idée-force d’ « homme différencié » et entamé une exploration, non encore achevée treize ans après, des textes d’Evola où celui-ci fut le principal « passeur » des idées de la « révolution conservatrice » allemande en Italie. Cette exploration m’a rendu conscient du rôle essentiel joué par les avant-gardes provocatrices des années 1905-1935 : il faut bien comprendre ce rôle clef pour saisir correctement toute approche de l’école traditionaliste, qui en procède tant par suite logique que par rejet. En effet, on ne peut comprendre Evola et Eemans que si l’on se plonge dans les vicissitudes de l’histoire du dadaïsme, du surréalisme et de ses avatars philosophiques non communisants en marge de Breton lui-même, et du vorticisme anglo-saxon. Les éditions « L’Age d’Homme » offrent une documentation extraordinaire sur ces thèmes, dont la revue « Mélusine » et quelques bons dossiers « H ». En 1999, à Zürich/Frauenfeld, j’ai prononcé à nouveau cette même allocution de Vienne, en y ajoutant combien la notion d’ « homme différencié », proche de celle d’ « anarque » chez Ernst Jünger, a été cardinale pour certains animateurs non gauchistes de la révolte étudiante italienne de 1968. En Italie, en effet, grâce à Evola, surtout à son « Chevaucher le Tigre », le mouvement contestataire n’a pas entièrement été sous la coupe des interprètes simplificateurs de l’ « Eros et la civilisation » d’Herbert Marcuse. Dans les legs diffus de cette révolte étudiante-là, on peut, aujourd’hui encore, aller chercher tous les ingrédients pratiques d’une révolte qui s’avèrerait bien vite plus profonde et plus efficace dans la lutte contre le système, une révolte efficace qui exaucerait sans doute au centuple les vœux de Tzara et de Breton…

Deux mémoires universitaires ont été consacrés tout récemment en Flandre à Evola, celui de Peter Verheyen, qui expose un parallèle entre l’auteur flamand Ernest van der Hallen et Julius Evola, et celui de Frédéric Ranson, intitulé « Julius Evola als criticus van de moderne wereld » (4). Ranson prononce souvent des conférences en Flandre sur Julius Evola, au départ de son mémoire et de ses recherches ultérieures. En Wallonie, en Pays de Liège, l’homme qui poursuit une quête traditionnelle au sens où l’entendent les militants italiens depuis le début des années 50 ou dans le sillage de « Terza Posizione » de Gabriele Adinolfi est Philippe Banoy. La balle est désormais dans leur camp : ce sont eux les héritiers potentiels de Vercauteren et d’Eemans. Mais des héritiers qui errent dans un champ de ruines encore plus glauque qu’à la fin des années 70. Un monde où les dernières traces de l’arèté grec semblent avoir définitivement disparu, sur fond de partouze festiviste permanente, de niaiserie et d’hystérie médiatiques ambiantes et d’inculture généralisée.

Evola, Eemans et la plupart des traditionalistes historiques de leur époque sont morts. Jean Parvulesco vient de nous quitter en novembre 2010. Un mouvement authentiquement traditionaliste doit-il se complaire uniquement dans la commémoration ? Non. Le seul à avoir repris le flambeau, avec toute l’autonomie voulue, demeure un inconnu chez nous dans la plupart des milieux situés bon an mal an sur le point d’intersection entre militance politique et méditation métaphysique : je veux parler de l’Espagnol Antonio Medrano, perdu de vue depuis ses articles dans la revue « Totalité » de Georges Gondinet. Ce mois-ci, en me promenant pour la première fois de ma vie dans les rues de Madrid, je découvre une librairie à un jet de pierre de la Plaza Mayor et de la Puerta del Sol qui vendait un ouvrage assez récent de Medrano. Quelle surprise ! Il est consacré à la notion traditionnelle d’honneur. Et la jaquette mentionne plusieurs autres ouvrages d’aussi bonne tenue, tous aux thèmes pertinents (5). Aujourd’hui, il conviendrait de fonder un « Centre d’Etudes doctrinales Evola & Medrano », de manière à faire pont entre un ancêtre « en absence » et un contemporain, qui, dans le silence, édifie une œuvre qui, indubitablement, est la poursuite de la quête.

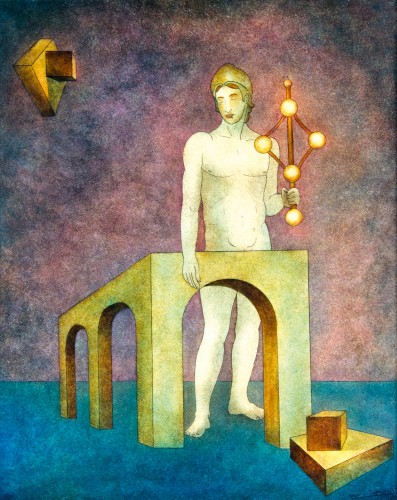

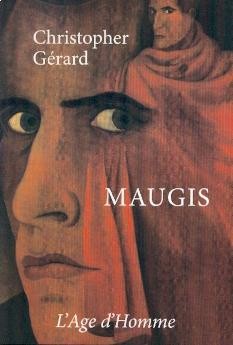

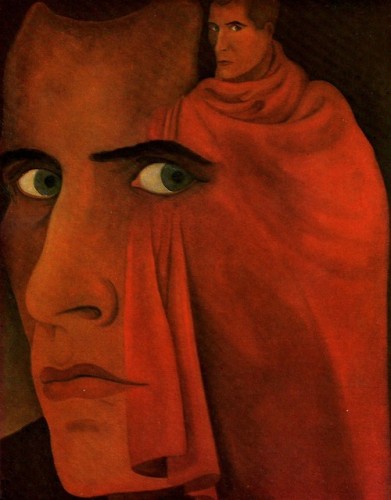

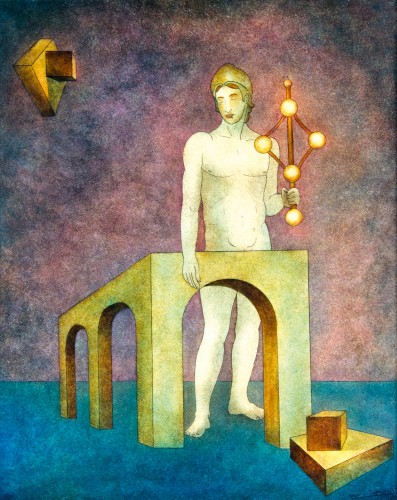

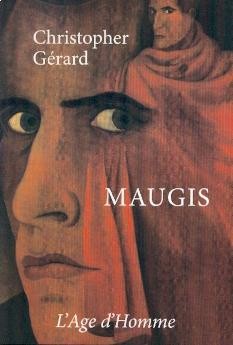

Enfin, il ne faut pas oublier de mentionner qu’Eemans survit, sous la forme d’une figure romanesque, baptisée Arminius, dans le roman initiatique de Christopher Gérard (6), rédigé après l’abandon, que j’estime malheureux, de sa revue « Antaios ». Arminius/Eemans y est un mage réprouvé (« après les proscriptions qui ont suivi les grandes conflagrations européennes »), ostracisé, qui distille son savoir au sein d’une confrérie secrète, plutôt informelle, qui, à terme, se donne pour objectif de ré-enchanter le monde (couverture du livre de Christopher Gérard avec, pour illustration, le plus beau, le plus poignant des tableaux d'Eemans: le Pélerin de l'Absolu).

Enfin, il ne faut pas oublier de mentionner qu’Eemans survit, sous la forme d’une figure romanesque, baptisée Arminius, dans le roman initiatique de Christopher Gérard (6), rédigé après l’abandon, que j’estime malheureux, de sa revue « Antaios ». Arminius/Eemans y est un mage réprouvé (« après les proscriptions qui ont suivi les grandes conflagrations européennes »), ostracisé, qui distille son savoir au sein d’une confrérie secrète, plutôt informelle, qui, à terme, se donne pour objectif de ré-enchanter le monde (couverture du livre de Christopher Gérard avec, pour illustration, le plus beau, le plus poignant des tableaux d'Eemans: le Pélerin de l'Absolu).

Pour conclure, je voudrais citer un extrait extrêmement significatif de la monographie que le Prof. Piet Tommissen a consacré à Marc. Eemans, extrait où il rappelait combien l’œuvre de Julius Langbehn avait marqué notre surréaliste de Termonde : « Au moment où il préparait son recueil ‘Het bestendig verbond’ en vue de publication, Eemans fit d’ailleurs la découverte, grâce à son ami le poète flamand Wies Moens, du livre posthume ‘Der Geist des Ganzen’ de Julius Langbehn (1851-1907) (…) Langbehn y analyse le concept de totalité à partir de la signification du mot grec ‘Katholon’. Selon lui, le ‘tout’ travaille en fonction des parties subordonnées et se manifeste en elles tandis que chaque partie travaille dans le cadre du ‘tout’ et n’existe qu’en fonction de lui. Le ‘mal’ est déviation, négation ou haine de la totalité organique dans l’homme et dans l’ordre temporel ; le ‘mal’ engendre la division et le désordre, aussi tout ce qui s’oppose à l’esprit de totalité crée tension et lutte. Pour que l’esprit de totalité règne, il faut que disparaisse la médiocrité intellectuelle car elle est le fruit d’hommes sans épine dorsale ou caractère et sans attaches avec la source de toute créativité qu’est la vie vraiment authentique de celui qui assume la totalité de sa condition humaine. Langbehn rappelle que les mots latins ‘vis’, ‘vir’ et ‘virtus’, soit force, homme et vertu, ont la même racine étymologique. Oui, l’homme vraiment homme est en même temps force et vertu, et tend ainsi vers le surhomme, par les voies d’un retour aux sources tel que l’entend le mythe d’Anthée ». Dans ces lignes, l’esprit averti repèrera bien des traces, bien des indices, bien des allusions…

(propos recueillis en avril et en mai 2011).

Bibliographie :

- Gérard DUROZOI, Histoire du mouvement surréaliste, Hazan, Paris, 1997 (Eemans est totalement absent de ce volume).

- Marc. EEMANS, La peinture moderne en Belgique, Meddens, Bruxelles, 1969.

- Piet TOMMISSEN, Marc. Eemans – Un essai de biographie intellectuelle, suivi d’une esquisse de biographie spirituelle par Friedrich-Markus Huebner et d’une postface de Jean-Jacques Gaillard, Sodim, Bruxelles, 1980.

- André VIELWAHR, S’affranchir des contradictions – André Breton de 1925 à 1930, L’Harmattan, Paris, 1998.

Notes :

(1) Geert WARNAR, Ruusbroec – Literatuur en mystiek in de veertiende eeuw, Athenaeum/Polak & Van Gennep, Amsterdam, 2003 ; Paul VERDEYEN, Jan van Ruusbroec – Mystiek licht uit de Middeleeuwen, Davidsfonds, Leuven, 2003.

(2) Jacqueline KELEN, Hadewych d’Anvers et la conquête de l’Amour lointain, Albin Michel, Paris, 2011.

(3) Mis à toutes les sauces, fort sollicité, j’ai également organisé ce jour-là un entretien entre Alain de Benoist et le regretté Alain Derriks, alors pigiste dans la revue du ministre Lucien Outers, « 4 millions 4 ». Soucieux de servir d’écho à tout ce qui se passait à Paris, le francophile caricatural qu’était Outers avait autorisé Derriks à prendre un interview du leader de la « Nouvelle Droite » qui faisait pas mal de potin dans la capitale française à l’époque. On illustra les deux ou trois pages de l’entretien d’une photo d’Alain de Benoist, les bajoues plus grassouillettes en ce temps-là et moins décharné qu’aujourd’hui (le « Fig Mag » payait mieux…), tirant goulument sur un long et gros cigare cubain.

(4) Frederik RANSON, « Julius Evola als criticus van de moderne wereld », RUG/Gent ; promoteur : Prof. Dr. Rik Coolsaet – année académique 2009-2010 ; Peter VERHEYEN, « Geloof me, we zijn zat van deze beschaving » - de performatieve cultuurkritiek van Ernest van der Hallen en Julius Evola tijdens het interbellum », RUG/Gent ; promoteur : Rajesh Heynick – année académique 2009-2010.

(5) Le livre découvert à Madrid est : Antonio Medrano, La Senda del Honor, Yatay, Madrid, 2002. Parmi les livres mentionnés sur la jaquette, citons : La lucha con el dragon (sur le mythe universel de la lutte contre le dragon), La via de la accion, Sabiduria activa, Magia y Misterio del Liderazgo – El Arte de vivir en un mondi en crisis, La vida como empressa, tous parus chez les même éditeur : Yatay Ediciones, Apartado 252, E-28.220 Majadahonda (Madrid) ; tél. : 91.633.37.52. La librairie de Madrid que j’ai visitée : Gabriel Molina – Libros antiguos y modernos – Historia Militar, Travesia del Arenal 1, E-28.013 Madrid – Tél/Fax : 91.366.44.43 – libreriamolina@yahoo.es .

(6) Christopher GERARD, Le songe d’Empédocle, L’Age d’Homme, Lausanne, 2003.

Een tweede man die een pen kan voeren vertoont zich als Brusselkenner. Naast Geert van Istendael en zijn trefzekere en te prijzen 'Arm Brussel', van oude datum (1992) met heruitgaven, heeft Eric Min een ronduit fantastische biografie geschreven over Vlaanderens trots en schande. Eric Min en zijn fraaie, rijke zinnen ken ik sedert zijn waardevolle en vernieuwende levensverhaal over James Ensor. Men zou denken dat over die Oostendse schilder van bizarrerieën alles in veelvoud was herkauwd, niets bleek minder waar te zijn. Ensor was het eerste boek van Min, die ambtenaar is van de Vlaamse regering, en in zijn vrije tijd cultuurmedewerker van De Morgen. Wat Min leerde uit Ensor, een opdracht van uitgever Meulenhoff (nu Bezige Bij), is hoeveel braakgrond, hoeveel sluimerende bronnen en teksten er blijven voor het portretteren van kunstenaars, schrijvers, prominenten waarover men denkt alles geschreven te zijn. Fout. Soms zijn er honderden brieven nooit gelezen, bestudeerd of geannoteerd bij de familie, op zolderkamers, in archieven waar geen professor of assistent binnen wil. Dat is ook de ervaring die Min opdeed bij het schrijven van de biografie van Brussel.

Een tweede man die een pen kan voeren vertoont zich als Brusselkenner. Naast Geert van Istendael en zijn trefzekere en te prijzen 'Arm Brussel', van oude datum (1992) met heruitgaven, heeft Eric Min een ronduit fantastische biografie geschreven over Vlaanderens trots en schande. Eric Min en zijn fraaie, rijke zinnen ken ik sedert zijn waardevolle en vernieuwende levensverhaal over James Ensor. Men zou denken dat over die Oostendse schilder van bizarrerieën alles in veelvoud was herkauwd, niets bleek minder waar te zijn. Ensor was het eerste boek van Min, die ambtenaar is van de Vlaamse regering, en in zijn vrije tijd cultuurmedewerker van De Morgen. Wat Min leerde uit Ensor, een opdracht van uitgever Meulenhoff (nu Bezige Bij), is hoeveel braakgrond, hoeveel sluimerende bronnen en teksten er blijven voor het portretteren van kunstenaars, schrijvers, prominenten waarover men denkt alles geschreven te zijn. Fout. Soms zijn er honderden brieven nooit gelezen, bestudeerd of geannoteerd bij de familie, op zolderkamers, in archieven waar geen professor of assistent binnen wil. Dat is ook de ervaring die Min opdeed bij het schrijven van de biografie van Brussel.

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

Eemans romantische en aristocratische gezindheid doen hem evolueren naar een eerder mythisch geïnspireerd nationaalsocialisme. “Eemans [zag] in het nazisme vooral een terugkeer tot de oertraditie, de wedergeboorte van een sacrale en magische wereld die ten onder was gegaan aan de technische, democratische maatschappij.” (1) Het in 1944 verschenen L'épreuve du feu: à la recherche d'une éthique

Eemans romantische en aristocratische gezindheid doen hem evolueren naar een eerder mythisch geïnspireerd nationaalsocialisme. “Eemans [zag] in het nazisme vooral een terugkeer tot de oertraditie, de wedergeboorte van een sacrale en magische wereld die ten onder was gegaan aan de technische, democratische maatschappij.” (1) Het in 1944 verschenen L'épreuve du feu: à la recherche d'une éthique

In Italia gli anni fra il 1927 ed il 1929 sono segnati da una vicenda spirituale, esoterica e culturale, sconosciuta al grande pubblico e poco esaminata dagli storici, ma che, nondimeno, è una esperienza importante perché é la più significativa della cultura esoterica italiana (ed anche europea) del Novecento: il Gruppo di Ur, diretto dal filosofo

In Italia gli anni fra il 1927 ed il 1929 sono segnati da una vicenda spirituale, esoterica e culturale, sconosciuta al grande pubblico e poco esaminata dagli storici, ma che, nondimeno, è una esperienza importante perché é la più significativa della cultura esoterica italiana (ed anche europea) del Novecento: il Gruppo di Ur, diretto dal filosofo

Le monografie della rivista furono poi raccolte in volume col titolo della rivista e poi, nella loro prima riedizione (1955, a cura dell’editore Bocca di Milano, poi per le Edizioni Mediterranee di Roma nel 1971) presero il titolo di Introduzione alla Magia, aggiungendo come sottotitolo “quale Scienza dell’Io”.