Filip MARTENS:

De trotskistische wortels van het neoconservatisme

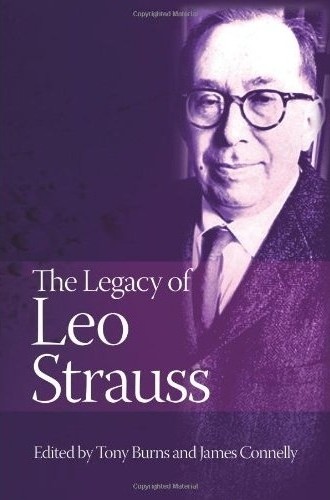

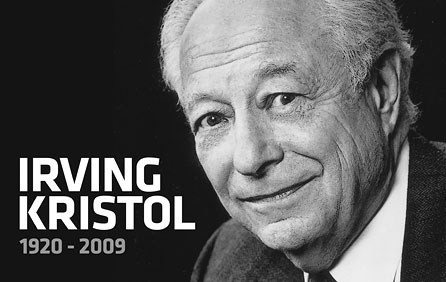

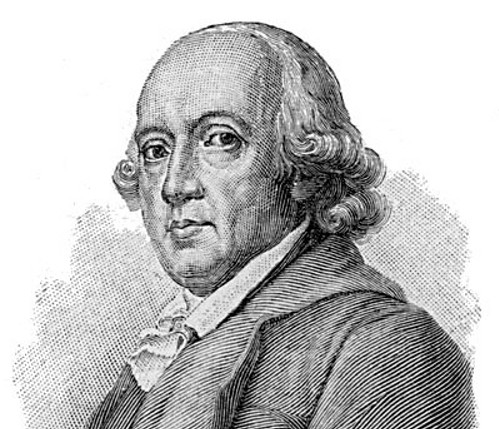

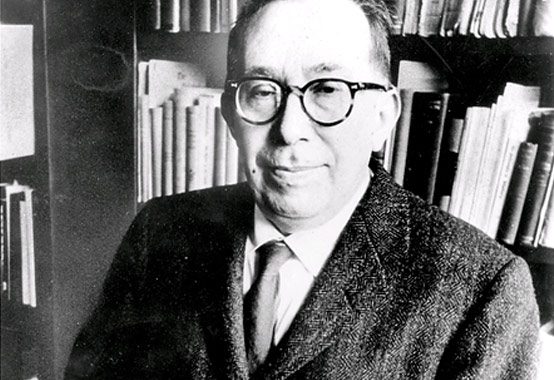

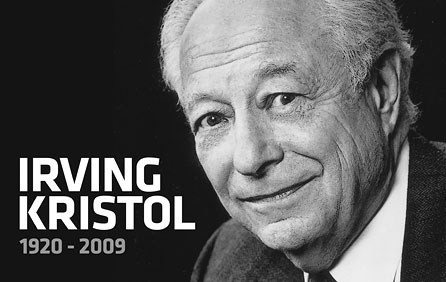

De neoconservatieve ideologie kreeg vanaf het begin der jaren 1980 een toenemende invloed in de internationale politiek. Ondanks de misleidende naam is het neoconservatisme echter helemaal niet conservatief, maar wel een linkse ideologie die het Amerikaanse conservatisme kaapte. Hoewel het neoconservatisme niet tot één bepaalde denker te herleiden valt, worden de politieke filosoof Leo Strauss (1899-1973) en de socioloog Irving Kristol (1920-2009) algemeen als grondleggers beschouwd.

1. De stichters van het neoconservatisme

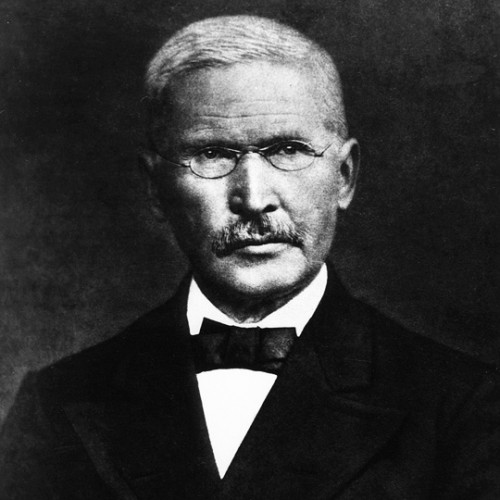

Leo Strauss werd in een joods gezin in de Duitse provincie Nassau geboren. Hij was een actieve zionist tijdens zijn studentenjaren in het Duitsland van na de Eerste Wereldoorlog. In 1934 emigreerde Strauss naar Groot-Brittannië en in 1937 naar de VS, waar hij aanvankelijk aangesteld werd aan de Colombia University in New York. In 1938-1948 was hij hoogleraar politieke filosofie aan de New School for Social Research in New York en in 1949-1968 aan de University of Chicago.

Aan de University of Chicago leerde Strauss zijn studenten dat het Amerikaanse secularisme zijn eigen vernietiging inhield: het individualisme, egoïsme en materialisme ondermijnden immers alle waarden en moraal en leidden in de jaren 1960 tot enorme chaos en rellen in de VS. De creatie en cultivering van religieuze en vaderlandslievende mythes zag hij als oplossing. Strauss stelde dat leugens om bestwil geoorloofd zijn om de maatschappij samen te houden en te sturen. Bijgevolg waren volgens hem door politici geponeerde en niet te bewijzen mythes noodzakelijk om de massa een doel te geven, wat tot een stabiele maatschappij zou leiden. Staatslieden moesten dus sterke inspirerende mythes creëren, die niet noodzakelijk met de waarheid moesten overeenstemmen. Strauss was hiermee één der inspirators achter het neoconservatisme dat in de jaren 1970 opkwam in de Amerikaanse politiek, hoewel hij zelf nooit aan actieve politiek deed en altijd een academicus bleef.

Aan de University of Chicago leerde Strauss zijn studenten dat het Amerikaanse secularisme zijn eigen vernietiging inhield: het individualisme, egoïsme en materialisme ondermijnden immers alle waarden en moraal en leidden in de jaren 1960 tot enorme chaos en rellen in de VS. De creatie en cultivering van religieuze en vaderlandslievende mythes zag hij als oplossing. Strauss stelde dat leugens om bestwil geoorloofd zijn om de maatschappij samen te houden en te sturen. Bijgevolg waren volgens hem door politici geponeerde en niet te bewijzen mythes noodzakelijk om de massa een doel te geven, wat tot een stabiele maatschappij zou leiden. Staatslieden moesten dus sterke inspirerende mythes creëren, die niet noodzakelijk met de waarheid moesten overeenstemmen. Strauss was hiermee één der inspirators achter het neoconservatisme dat in de jaren 1970 opkwam in de Amerikaanse politiek, hoewel hij zelf nooit aan actieve politiek deed en altijd een academicus bleef.

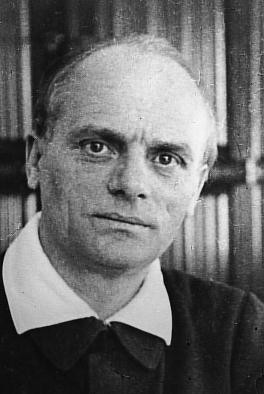

Irving Kristol was de zoon van Oost-Europese joden die in de jaren 1890 emigreerden naar Brooklyn, New York. In de eerste helft der jaren 1940 was hij lid van de Vierde Internationale van Leon Trotski (1879-1940), de door Stalin uit de USSR verbannen bolsjewistische leider die met deze rivaliserende communistische beweging Stalin bestreed. Vele vooraanstaande Amerikaans-joodse intellectuelen traden toe tot de Vierde Internationale.

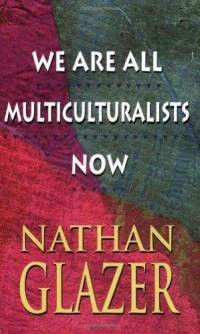

Kristol was tevens lid van de invloedrijke New York Intellectuals, een eveneens anti-stalinistisch en anti-USSR collectief van trotskistische joodse schrijvers en literaire critici uit New York. Naast Kristol behoorden hier ook Hannah Arendt, Daniel Bell, Saul Bellow, Marshall Berman, Nathan Glazer, Clement Greenberg, Richard Hofstadter, Sidney Hook, Irving Howe, Alfred Kazin, Mary McCarthy, Dwight MacDonald, William Phillips, Norman Podhoretz, Philip Rahy, Harold Rosenberg, Isaac Rosenfeld, Delmore Schwartz, Susan Sontag, Harvey Swados, Diana Trilling, Lionel Trilling, Michael Walzer, Albert Wohlstetter en Robert Warshow toe. Velen van hen hadden gestudeerd aan het City College of New York, de New York University en de Colombia University in de jaren 1930 en 1940. Ze woonden tevens voornamelijk in de New Yorkse stadsdelen Brooklyn en de Bronx. Tijdens de Tweede Wereldoorlog groeide bij deze trotskisten het besef dat de VS nuttig kon zijn om de door hen gehate USSR te bestrijden. Sommigen van hen, zoals Glazer, Hook, Kristol en Podhoretz, ontwikkelden later het neoconservatisme, dat het trotskistische universalisme en zionisme behield.

Kristol begon als een overtuigd marxist bij de Democratische Partij. Hij was in de jaren 1960 een leerling van Strauss. Hun neoconservatisme bleef geloven in de marxistische maakbaarheid van de wereld: de VS moest internationaal actief optreden om de parlementaire democratie en het kapitalisme te verspreiden. Daarom was Kristol een fel voorstander van de Amerikaanse oorlog in Vietnam. Strauss en Kristol verwierpen bovendien de liberale scheiding van Kerk en Staat, daar de seculiere maatschappij tot individualisme leidde. Zij maakten religie weer bruikbaar voor de Staat.

Kristol verspreidde zijn gedachtegoed als hoogleraar sociologie aan de New York University, via een column in de Wall Street Journal, via de door hem gestichte tijdschriften The Public Interest en The National Interest en via het door zijn zoon William Kristol gestichte invloedrijke neocon-weekblad The Weekly Standard (dat gefinancierd wordt door mediamagnaat Rupert Murdoch).

Kristol was tevens betrokken bij het in 1950 door de CIA opgerichte en gefinancierde Congress for Cultural Freedom. Deze in ca. 35 landen actieve anti-USSR organisatie gaf het Britse blad Encounter uit, dat Kristol samen met de Britse ex-marxistische dichter en schrijver Stephen Spender (1909-1995) oprichtte. Spender voelde zich door zijn gedeeltelijke joodse afkomst erg aangetrokken tot het jodendom en was ook gehuwd met de joodse concertpianiste Natasha Litvin. Toen in 1967 de betrokkenheid van de CIA bij het Congress for Cultural Freedom uitlekte in de pers, trok Kristol zich er uit terug en engageerde zich in de neocon-denktank American Enterprise Institute.

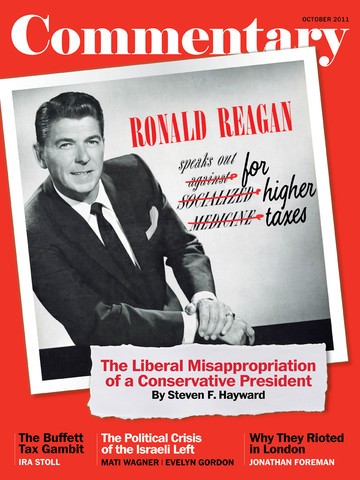

Kristol redigeerde tevens samen met Norman Podhoretz (°1930) het maandblad Commentary in 1947-1952. Podhoretz was de zoon van joodse marxisten uit Galicië, die zich in Brooklyn vestigden. Hij studeerde aan de Columbia University, het Jewish Theological Seminary en de University of Cambridge. In 1960-1995 was Podhoretz hoofdredacteur van Commentary. Zijn invloedrijke essay ‘My Negro Problem – And Ours’ uit 1963 bepleitte een volledige raciale vermenging van het blanke en zwarte ras daar voor hem “the wholesale merging of the 2 races the most desirable alternative” was.

Podhoretz was in 1981-1987 adviseur van de US Information Agency, een Amerikaanse propagandadienst die tot doel had om buitenlandse publieke opinies en staatsinstellingen op te volgen en te beïnvloeden. In 2007 kreeg Podhoretz de Guardian of Zion Award, een jaarlijkse prijs die de Israëlische Bar-Ilan Universiteit schenkt aan een belangrijke steunpilaar van de staat Israël.

Andere leidende namen in deze nieuwe ideologie waren Allan Bloom, Podhoretz’ vrouw Midge Decter en Kristols vrouw Gertrude Himmelfarb. Bloom (1930-1992) werd geboren in een joods gezin in Indiana. Aan de University of Chicago werd hij sterk beïnvloed door Leo Strauss. Later werd Bloom hoogleraar filosofie aan diverse universiteiten. De latere hoogleraar Francis Fukuyama (°1952) was een van zijn studenten. De joodse feministische journaliste en schrijfster Midge Decter (°1927) was een der stichters van de neocon-denktank Project for the New American Century en zetelt tevens in de raad van bestuur van de neocon-denktank Heritage Foundation. De joodse historica Gertrude Himmelfarb werd in 1922 geboren in Brooklyn. Tijdens haar studies aan de University of Chicago, het Jewish Theological Seminary en de University of Cambridge was ze een actieve trotskiste. Later was Himmelfarb actief in de neocon-denktank American Enterprise Institute.

2. De trotskistische wortels van het neoconservatisme

Het neoconservatisme wordt onterecht als ‘rechts’ beschouwd vanwege het voorvoegsel ‘neo’, dat verkeerdelijk een nieuw conservatief denken suggereert. Vele neocons hebben echter integendeel een extreem-links verleden, namelijk in het trotskisme. De meeste neocons stammen immers af van trotskistische joodse intellectuelen uit Oost-Europa (voornamelijk Polen, Litouwen en Oekraïne). Daar de USSR in de jaren 1920 het trotskisme verbande, is het begrijpelijk dat zij in de VS actief werden als anti-USSR lobby binnen de links-liberale Democratische Partij en in andere linkse organisaties.

Irving Kristol definieerde een neocon als “een progressief die getroffen werd door de realiteit”. Dit wijst er op dat een neocon iemand is die wisselde van politieke strategie om zo beter zijn doelen te kunnen bereiken. In de jaren 1970 ruilden de neocons immers het trotskisme in voor het liberalisme en verlieten de Democratische Partij. Vanwege hun sterke aversie tegen de USSR en tegen de verzorgingsstaat sloten zij om strategische redenen aan bij het anticommunisme der Republikeinen.

Als voormalige trotskist bleef de neocon Kristol marxistische ideeën promoten, zoals reformistisch socialisme en internationale revolutie via natievorming en militair opgelegde democratische regimes. Daarnaast verdedigen de neocons progressieve eisen als abortus, euthanasie, massa-immigratie, mondialisering, multiculturalisme en vrijhandelskapitalisme. Ook de verzorgingsstaten worden gezien als overbodig, hoewel de bevolking liefst haar moeizaam opgebouwde sociale zekerheid ziet blijven bestaan. De neocons zwaaien daarom met zwaar overdreven doemscenario’s – zoals vergrijzing en mondialisering – om de bevolking rijp te maken voor een slachtpartij in de overheidssector en in de sociale voorzieningen. Ze zoeken daarvoor steun bij de liberaal-kapitalistische politieke krachten. Ook de term ‘armoedeval’ (poverty trap), die slaat op werklozen die niet gaan werken omdat de daardoor veroorzaakte kosten hun iets hogere inkomen uit arbeid afzwakken, werd uitgevonden door neocons.

Stuk voor stuk zijn dit kernconcepten van de neocon-filosofie. In 1979 noemde het tijdschrift Esquire Irving Kristol “the godfather of the most powerful new political force in America: neoconservatism”. Dat jaar verscheen ook Peter Seinfels’ boek ‘The Neoconservatives: The Men Who Are Changing America’s Politics’, dat wees op de toenemende politieke en intellectuele invloed der neocons.

Het maandblad Commentary was de opvolger van het in 1944 stopgezette blad Contemporary Jewish Record en werd in 1945 gesticht door het American Jewish Committee. Onder hoofdredacteur Elliot Cohen (1899-1959) richtte Commentary zich op de traditioneel zeer linkse joodse gemeenschap, terwijl het tegelijk de ideeën van jonge joodse intellectuelen bij een breder publiek wou bekendmaken. Norman Podhoretz, die in 1960 hoofdredacteur werd, stelde dan ook terecht dat Commentary de radicaal-trotskistische joodse intellectuelen verzoende met het liberaal-kapitalistische Amerika. Commentary vaarde een anti-USSR koers en ondersteunde volop de 3 pilaren van de Koude Oorlog: de Truman-doctrine, het Marshallplan en de NAVO.

Dit tijdschrift over politiek, maatschappij, jodendom en sociaal-culturele onderwerpen speelt sinds de jaren 1970 een leidinggevende rol in het neoconservatisme. Commentary vormde het joodse trotskisme om tot het neoconservatisme en is het invloedrijkste Amerikaanse blad van de voorbije halve eeuw omdat het het Amerikaanse politieke en intellectuele leven grondig veranderde. Immers, het verzet tegen de Vietnamoorlog, tegen het aan die oorlog ten grondslag liggende kapitalisme en vooral de vijandigheid tegen Israël in de Zesdaagse Oorlog van 1967 wekten de woede van hoofdredacteur Podhoretz. Commentary schilderde deze oppositie daarom af als anti-amerikaans, antiliberaal en antisemitisch. Dit leidde tot het ontstaan van het neoconservatisme, dat hevig de liberale democratie verdedigde en zich afzette tegen de USSR en tegen Derde Wereldlanden die het neokolonialisme bestreden. Strauss’ studenten – onder meer Paul Wolfowitz (°1943) en Allan Bloom – stelden dat de VS een strijd tegen ‘het Kwade’ moest voeren en de als ‘Goed’ beschouwde parlementaire democratie en kapitalisme in de wereld verspreiden.

Daarnaast praatten zij de Amerikaanse bevolking een – fictief – islamgevaar aan, op basis waarvan ze Amerikaanse interventie in het Nabije Oosten voorstaan. Maar bovenal pleiten neocons voor enorme en onvoorwaardelijke steun van de VS aan Israël, zelfs in die mate dat de traditionele conservatief Russel Kirk (1918-1994) ooit stelde dat neocons de Amerikaanse hoofdstad verwarden met Tel-Aviv. Volgens Kirk was dit zelfs het hoofdonderscheid tussen neocons en de oorspronkelijke Amerikaanse conservatieven. Hij waarschuwde reeds in 1988 dat het neoconservatisme zeer gevaarlijk en oorlogszuchtig was. De door de VS gevoerde Golfoorlog van 1990-1991 gaf hem meteen gelijk.

Neocons streven nadrukkelijk naar macht om hun hervormingen te kunnen doordrukken in de verwachting dat de kwaliteit der samenleving daardoor zal verbeteren. Daarbij zijn ze zozeer overtuigd van hun eigen gelijk dat ze niet wachten tot er brede steun is voor hun ingrepen, ook niet bij ingrijpende hervormingen. Daardoor is neoconservatisme een marxistische maakbaarheidsutopie.

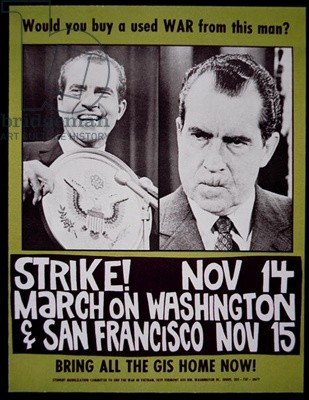

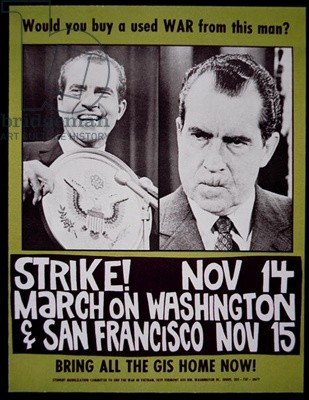

3. De neocons in het verzet tegen president Richard Nixon

In de jaren 1970 kwam het neoconservatisme op als verzetsbeweging tegen president Nixons beleid. De Republikein Richard Nixon (1913-1994) voerde samen met Henry Kissinger (°1923) – nationaal veiligheidsadviseur in 1969-1975 en minister van Buitenlandse Zaken in 1973-1977 – immers een volkomen ander buitenlands beleid door relaties aan te knopen met maoïstisch China en een détente te starten met de USSR. Daarnaast voerde Nixon ook een sociaal beleid en schafte hij de goudstandaard af, waardoor dollars niet langer inwisselbaar waren in goud.

Nixon en Kissinger maakten gebruik van de hoogoplopende spanningen en grensconflicten tussen de USSR en China om in 1971 in het diepste geheim relaties aan te knopen met China, waarna Nixon in februari 1972 als eerste Amerikaanse president maoïstisch China bezocht. Mao Zedong bleek enorm onder de indruk van Nixon. Uit vrees voor een Chinees-Amerikaanse alliantie zwichtte de USSR nu voor het Amerikaanse streven naar détente, waardoor Nixon en Kissinger de bipolaire wereld – het Westen vs. het communistische blok – omvormden in een multipolair machtsevenwicht. Nixon bezocht in mei 1972 Moskou en onderhandelde er met Sovjetleider Brezjnev handelsakkoorden en 2 baanbrekende wapenbeperkingsverdragen (SALT I en het ABM-verdrag). De vijandigheid van de Koude Oorlog werd nu vervangen door de détente, die de spanningen deed luwen. De relaties tussen USSR en VS verbeterden vanaf 1972 dan ook sterk. Eind mei 1972 kwam al een vijfjarig samenwerkings-programma inzake ruimtevaart tot stand. Dit leidde tot het Apollo-Sojoez-testproject in 1975, waarbij een Amerikaanse Apollo en een Sovjet-Sojoez een gezamenlijke ruimtevaartmissie uitvoerden.

China en de USSR bouwden nu hun steun af voor Noord-Vietnam, dat geadviseerd werd om vredesbesprekingen te starten met de VS. Hoewel Nixon aanvankelijk de oorlog in Zuid-Vietnam nog ernstig had doen escaleren door ook de buurlanden Laos, Cambodja en Noord-Vietnam aan te vallen, trok hij geleidelijk zijn troepen terug en kon Kissinger in 1973 een vredesakkoord sluiten. Nixon begreep immers dat voor een succesvolle vrede de USSR en China er bij betrokken moesten worden.

Nixon was voorts de overtuiging toegedaan dat een verstandig regeringsbeleid de gehele bevolking kon ten goede komen. Hij hevelde federale bevoegdheden over naar de deelstaten, zorgde voor meer voedselhulp en sociale hulp en stabiliseerde de lonen en prijzen. De defensieuitgaven daalden van 9,1% tot 5,8% van het BNP en het gemiddelde gezinsinkomen steeg. In 1972 werd de sociale zekerheid sterk uitgebreid door een minimuminkomen te garanderen. Nixon werd vanwege zijn succesvolle sociaal-economische beleid zeer populair. Hij werd dan ook in november 1972 herkozen met een van de allergrootste verkiezingsoverwinningen uit de Amerikaanse geschiedenis.

De neocons vormden toen nog binnen de Democratische Partij een oppositiebeweging, die hevig anti-USSR was en de détente van Nixon en Kissinger met de USSR afwees. Neocon-zakenlui stelden enorme geldsommen beschikbaar voor neocon-denktanks en -tijdschriften. In 1973 vroegen de Straussianen dat de VS druk zou uitoefenen op de USSR om Sovjetjoden te laten emigreren. Minister van Buitenlandse Zaken Kissinger – nochtans zelf een jood – vond echter dat de situatie der Sovjetjoden niets met Amerika’s belangen van doen had en weigerde dan ook de USSR hierop aan te spreken. De Democratische senator Henry Jackson (1912-1983) ondergroef de détente door het Jackson-Vanik-amendement van 1974, dat détente afhankelijk maakte van de bereidheid der USSR om Sovjetjoden te laten emigreren. Jackson werd in de Democratische Partij bekritiseerd vanwege zijn nauwe banden met de wapenindustrie en zijn steun voor de Vietnamoorlog en voor Israël. Voor dit laatste kreeg hij tevens aanzienlijke financiële steun van Amerikaanse joden. Diverse medewerkers van Jackson, zoals Elliot Abrams, Richard Perle (°1941), Benjamin Wattenberg (°1933) en Wolfowitz, zouden later leidinggevende neocons worden.

Kissinger was ook niet opgezet met de aanhoudende Israëlische verzoeken voor Amerikaanse steun en noemde de Israëlische regering “a sick bunch”: “We have vetoed 8 resolutions for the past years, given them 4 billion dollar in aid (…) and we still are treated as if we have done nothing for them”. Uit diverse bandopnames van het Witte Huis uit 1971 blijkt dat ook president Nixon ernstige twijfels had over de Israëllobby in Washington en over Israël.

Kissinger weerhield er Israël tijdens de Yom Kippoeroorlog van 1973 van om het omsingelde Egyptische 3de Leger in de Sinaï te vernietigen. Toen ook de USSR zijn pro-Arabische retoriek niet durfde hardmaken, kon hij Egypte uit het Sovjetkamp losweken en omvormen tot een bondgenoot der VS, wat een ernstige verzwakking van de Sovjetinvloed in het Nabije Oosten betekende.

Nixon zette ondertussen zijn sociale hervormingen voort. Zo voerde hij in februari 1974 een ziekteverzekering in op basis van werkgevers- en werknemersbijdragen. Hij diende echter in augustus 1974 af te treden vanwege het Watergate-schandaal, dat begon in juni 1972 en bestond uit een meer dan 2 jaar aanhoudende reeks sensationele media-‘onthullingen’ die diverse Republikeinse regeringsfunctionarissen en uiteindelijk president Nixon zelf in zeer ernstige moeilijkheden brachten.

In het bijzonder de krant Washington Post bevuilde het blazoen van de regering-Nixon aanzienlijk: de redacteuren Howard Simons (1929-1989) en Harry Rosenfeld (°1929) organiseerden al in een heel vroeg stadium de buitengewone berichtgeving over wat het Watergate-schandaal zou worden en zetten de journalisten Bob Woodward (°1943) en Carl Bernstein (°1944) op de zaak. Onder het goedkeurend oog van hoofdredacteur Benjamin Bradlee (°1921) suggereerden Woodward en Bernstein op basis van anonieme bronnen talloze verdachtmakingen tegen de regering-Nixon. Rosenfeld kwam uit een familie van Duitse joden die zich in 1939 in de Bronx, New York vestigden. Bernsteins joodse ouders waren lid van de Communist Party of America en werden gedurende 30 jaar geschaduwd door het FBI wegens subversieve activiteiten, waardoor zij een FBI-dossier van meer dan 2.500 bladzijden hadden. Woodward wordt al decennia beschuldigd van overdrijvingen en verzinsels in zijn verslaggeving, vooral inzake zijn anonieme bronnen over het Watergate-schandaal.

Door dit media-offensief tegen de regering-Nixon werd een intensief gerechtelijk onderzoek gevoerd en richtte de Senaat zelfs een onderzoekscommissie op die overheidsmedewerkers begon te dagvaarden. Nixon diende bijgevolg in 1973 diverse topmedewerkers te ontslaan en kwam uiteindelijk zelf onder vuur te liggen, hoewel hij niets te maken had met de inbraak en de smeergeldaffaire die aan de basis van het Watergate-schandaal lagen. Vanaf april 1974 werd openlijk gespeculeerd over de afzetting van Nixon en toen dit in de zomer van 1974 effectief dreigde te gebeuren, nam hij op 9 augustus zelf ontslag. Minister van Buitenlandse Zaken Kissinger voorspelde tijdens deze laatste dagen dat de geschiedschrijving Nixon zou herinneren als een groot president en dat het Watergate-schandaal slechts een voetnoot zou blijken te zijn.

Nixon werd opgevolgd door vicepresident Gerald Ford (1913-2006). De neocons oefenden aanzienlijke druk uit op Ford om George Bush sr. (°1924) als nieuwe vicepresident aan te stellen, doch Ford ontstemde hen door voor de gematigder Nelson Rockefeller (1908-1979), ex-gouverneur van de staat New York, te kiezen. Daar ondanks Nixons aftreden het parlement en de media er bleven naar streven om hem voor het gerecht te brengen, verleende Ford in september 1974 een presidentieel pardon aan Nixon voor diens vermeende rol in het Watergate-schandaal. Ondanks de enorme impact van dit schandaal werden de wortels ervan nooit blootgelegd. Nixon bleef tot zijn dood in 1994 zijn onschuld volhouden, hoewel hij wel beoordelingsfouten in de aanpak van het schandaal toegaf. De resterende 20 jaar van zijn leven zou hij besteden aan het herstel van zijn zwaar gehavende imago.

Nixon werd opgevolgd door vicepresident Gerald Ford (1913-2006). De neocons oefenden aanzienlijke druk uit op Ford om George Bush sr. (°1924) als nieuwe vicepresident aan te stellen, doch Ford ontstemde hen door voor de gematigder Nelson Rockefeller (1908-1979), ex-gouverneur van de staat New York, te kiezen. Daar ondanks Nixons aftreden het parlement en de media er bleven naar streven om hem voor het gerecht te brengen, verleende Ford in september 1974 een presidentieel pardon aan Nixon voor diens vermeende rol in het Watergate-schandaal. Ondanks de enorme impact van dit schandaal werden de wortels ervan nooit blootgelegd. Nixon bleef tot zijn dood in 1994 zijn onschuld volhouden, hoewel hij wel beoordelingsfouten in de aanpak van het schandaal toegaf. De resterende 20 jaar van zijn leven zou hij besteden aan het herstel van zijn zwaar gehavende imago.

In oktober 1974 werd Nixon getroffen door een levensbedreigende vorm van flebitis, waarvoor hij geopereerd diende te worden. President Ford kwam hem bezoeken in het ziekenhuis, maar de Washington Post – opnieuw – vond het nodig om de zwaar zieke Nixon te bespotten. In het voorjaar van 1975 verbeterde Nixons gezondheid en begon hij aan zijn memoires te werken, hoewel zijn bezittingen opgevreten werden door onder meer hoge advocatenkosten. Op een bepaald moment had ex-president Nixon nog amper 500 dollar op zijn bankrekening staan. Vanaf augustus 1975 verbeterde zijn financiële toestand door een reeks interviews voor een Brits televisieprogramma en door de verkoop van zijn buitenverblijf. Zijn in 1978 verschenen autobiografie ‘RN: The Memoirs of Richard Nixon’ werd een bestseller.

Chinese staatsleiders als Mao Zedong en Deng Xiaoping bleven Nixon nog jarenlang dankbaar voor de verbeterde relaties met de VS en nodigden hem herhaaldelijk uit naar China. Nixon slaagde er pas halfweg de jaren 1980 in om zijn geschonden reputatie enigszins te herstellen na druk in de media becommentarieerde reizen naar het Nabije Oosten en de USSR.

President Ford en Kissinger zetten Nixons détente voort door onder meer de Helsinki-Akkoorden te sluiten met de USSR. En toen Israël bleef weigeren om vrede te sluiten met Egypte, schortte Ford in 1975 onder hevig protest der neocons gedurende 6 maanden alle Amerikaanse militaire en economische steun aan Israël op. Dit was een waar dieptepunt in de Israëlisch-Amerikaanse relaties.

4. De opmars van het neoconservatisme

Neocons als stafchef van het Witte Huis Donald Rumsfeld (°1932), presidentieel adviseur Dick Cheney (°1941), senator Jackson en diens medewerker Paul Wolfowitz duidden tijdens de regering-Ford (1974-1977) de USSR aan als ‘het Kwade’, ook al stelde de CIA dat er géén bedreiging uitging van de USSR en er geen enkel bewijs voor te vinden was. De CIA werd dan ook verweten – onder meer door de Straussiaanse neocon-hoogleraar Albert Wohlstetter (1913-1997) – dat het eventuele bedreigende intenties van de USSR onderschatte.

De Republikeinse Partij verloor door het Watergate-schandaal zwaar bij de parlementsverkiezingen van november 1974, waardoor de neocons de kans kregen om meer invloed te verwerven in de regering. Toen William Colby (1920-1996), hoofd van de CIA, bleef weigeren om een ad hoc studiegroep van externe experten het werk van zijn analisten te laten overdoen, ijverde Rumsfeld in 1975 met succes bij president Ford voor een grondige herschikking van de regering. Op 4 november 1975 werden in dit ‘Halloween Massacre’ diverse gematigde ministers en topambtenaren vervangen door neocons. Onder meer Colby werd vervangen door Bush sr. als hoofd van de CIA, Kissinger bleef minister van Buitenlandse Zaken maar verloor zijn functie van nationaal veiligheidsadviseur aan generaal Brent Scowcroft (°1925), James Schlesinger werd opgevolgd door Rumsfeld als minister van Defensie, Cheney kreeg Rumsfelds vrijgekomen plaats van stafchef van het Witte Huis en John Scali stond zijn plaats als ambassadeur bij de VN af aan Daniel Moynihan (1927-2003). Vicepresident Rockefeller kondigde tevens onder druk der neocons aan dat hij niet zou opkomen als running mate van Ford bij de presidentsverkiezingen van 1976.

Het nieuwe CIA-hoofd Bush sr. vormde de anti-USSR studiegroep Team B onder leiding van de joodse hoogleraar Russische geschiedenis Richard Pipes (°1923) om de intenties der USSR te ‘herbestuderen’. Alle leden van Team B waren a priori al anti-USSR gezind. Pipes nam op aanraden van Richard Perle Wolfowitz op in Team B. Het zwaar omstreden rapport uit 1976 van deze studiegroep beweerde “een ononderbroken streven van de USSR naar wereldhegemonie” en “een falen der inlichtingendiensten” vastgesteld te hebben.

Achteraf bleek Team B op alle vlakken volkomen fout geweest te zijn. De USSR had immers helemaal geen “toenemend BNP waarmee het zich steeds meer wapens aanschafte”, maar verzonk langzaam in economische chaos. Ook een vermeende vloot niet door radar detecteerbare kernonderzeeërs heeft nooit bestaan. Door deze pure verzinsels praatten de Straussianen de VS bijgevolg een fictieve bedreiging door ‘het Kwade’ aan. Team B’s rapport werd gebruikt om de massale (en onnodige) investeringen in bewapening te rechtvaardigen, die begonnen op het einde der regering-Carter (1977-1981) en explodeerden tijdens de regering-Reagan (1981-1989).

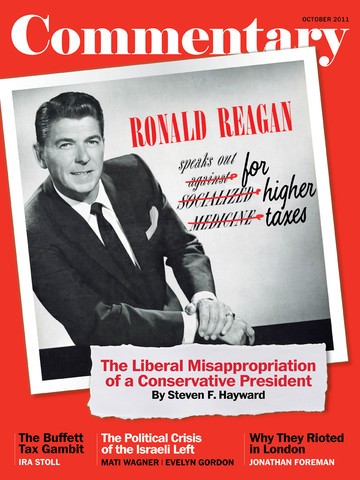

In de aanloop naar de presidentsverkiezingen van 1976 schoven de neocons ex-gouverneur van Californië én ex-Democraat (!) Ronald Reagan (1911-2004) naar voor als alternatief voor Ford, die onder meer zijn détente tegenover de USSR en het opschorten van de steun aan Israël werd verweten. Desondanks slaagde Ford er toch in om zich tot Republikeins presidentskandidaat te laten aanduiden. In de eigenlijke presidentsverkiezing verloor hij echter tegen de Democraat Jimmy Carter (°1924).

Binnen de door neocons geïnfiltreerde Republikeinse Partij kwam in de jaren 1970 de denktank American Enterprise Institute op. Deze telde invloedrijke neocon-intellectuelen als Nathan Glazer (°1924), Irving Kristol, Michael Novak (°1933), Benjamin Wattenberg en James Wilson (°1931). Zij beïnvloedden de traditioneel-conservatieve achterban der Republikeinen, waardoor het groeiende protestantse fundamentalisme aansloot bij het neoconservatisme. De protestant Reagan werd hierdoor in 1981 president en benoemde direct een reeks neocons (zoals John Bolton, Rumsfeld, Wolfowitz, Doug Feith, William Kristol, Lewis Libby en Elliot Abrams). Bush sr. werd vicepresident.

Binnen de door neocons geïnfiltreerde Republikeinse Partij kwam in de jaren 1970 de denktank American Enterprise Institute op. Deze telde invloedrijke neocon-intellectuelen als Nathan Glazer (°1924), Irving Kristol, Michael Novak (°1933), Benjamin Wattenberg en James Wilson (°1931). Zij beïnvloedden de traditioneel-conservatieve achterban der Republikeinen, waardoor het groeiende protestantse fundamentalisme aansloot bij het neoconservatisme. De protestant Reagan werd hierdoor in 1981 president en benoemde direct een reeks neocons (zoals John Bolton, Rumsfeld, Wolfowitz, Doug Feith, William Kristol, Lewis Libby en Elliot Abrams). Bush sr. werd vicepresident.

In plaats van détente kwam er nu een agressief buitenlands en fel anti-USSR beleid, dat sterk steunde op de Kirkpatrick-doctrine die de ex-marxiste en ex-Democrate (!) Jeane Kirkpatrick (1926-2006) in 1979 in haar spraakmakende artikel ‘Dictatorships and Double Standards’ in Commentary beschreef. Dit behelsde dat hoewel de meeste regeringen in de wereld autocratieën zijn én dat ook altijd waren, het mogelijk zou zijn om die op lange termijn te democratiseren. Deze Kirkpatrick-doctrine moest vooral dienen om de steun aan pro-Amerikaanse dictaturen in de Derde Wereld te rechtvaardigen.

Veel immigranten uit het Oostblok werden actief in de neocon-beweging. Zij waren eveneens hevige tegenstanders van détente met de USSR en beschouwden het progressisme als superieur. Podhoretz bekritiseerde bovendien in het begin der jaren 1980 de voorstanders van détente zeer scherp.

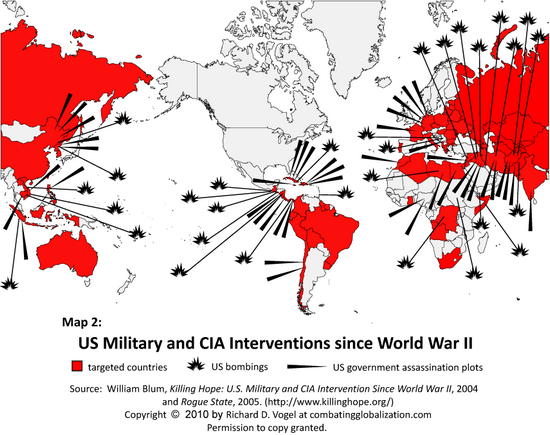

De Amerikaanse bevolking werd nu een nog grotere Sovjetbedreiging aangepraat: de USSR zou een internationaal terreurnetwerk sturen en dus achter de terreuraanslagen in de hele wereld zitten. Opnieuw deed de CIA dit af als onzin, maar verspreidde toch de propaganda van het “internationale Sovjet-terreurnetwerk”. Bijgevolg moest de VS reageren. De neocons werden nu democratische revolutionairen: de VS zou internationaal krachten steunen om de wereld te veranderen. Zo werden in de jaren 1980 de Afghaanse mudjaheddin zwaar gesteund in hun strijd tegen de USSR en de Nicaraguaanse Contra’s tegen de sandinistische regering-Ortega. Daarnaast startte de VS een wapenwedloop met de USSR, die echter tot grote begrotingstekorten en een stijgende overheidsschuld leidde: Reagans defensiebeleid deed immers de defensie-uitgaven met 40% stijgen in 1981-1985 en verdriedubbelde het begrotingstekort.

De opkomst der neocons leidde tot een jarenlange Kulturkampf in de VS. Zij verwierpen immers het schuldgevoel over de nederlaag in Vietnam, evenals Nixons buitenlandse beleid. Daarnaast ontstond er verzet tegen een actief internationaal optreden der VS en tegen de vereenzelviging van de USSR met ‘het Kwade’. Reagans buitenlands beleid werd bekritiseerd als agressief, imperialistisch en oorlogszuchtig. Bovendien werd de VS in 1986 door het Internationaal Gerechtshof veroordeeld voor oorlogsmisdaden tegen Nicaragua. Ook veel Centraal-Amerikanen veroordeelden Reagans steun aan de Contra’s en noemden hem een overdreven fanaticus die bloedbaden, martelingen en andere gruwelen over het hoofd zag. De Nicaraguaanse president Ortega gaf ooit aan te hopen dat God Reagan zou vergeven voor zijn “vuile oorlog tegen Nicaragua”.

Ook in de regering-Bush sr. (1989-1993) beïnvloedden neocons het buitenlands beleid. Bijvoorbeeld Dan Quayle (°1947) was toen vicepresident en Cheney minister van Defensie met Wolfowitz als medewerker. Wolfowitz verzette zich in 1991-1992 tegen Bush’ beslissing om het Iraakse regime niet af te zetten na de Golfoorlog van 1990-1991. Hij en Lewis Libby (°1950) stelden in 1992 in een rapport aan de regering ‘preventieve’ aanvallen om “de aanmaak van massavernietigingswapens te voorkomen” – tóen reeds! – en hogere defensie-uitgaven voor. De VS kampte door Reagans bewapeningswedloop echter met een enorm begrotingstekort.

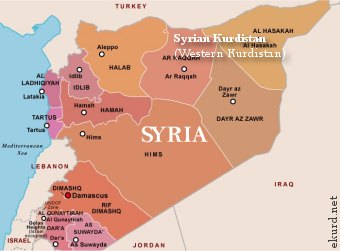

Tijdens de regering-Clinton (1993-2001) werden de neocons verdreven naar de denktanks, waar een twintigtal neocons regelmatig samenkwam, onder meer om over het Nabije Oosten te praten. Een door Richard Perle geleidde neocon-studiegroep met onder meer Doug Feith en David Wurmser stelde in 1996 het betwiste rapport ‘A Clean Break: A New Strategy for Securing the Realm’ op. Dit adviseerde de net aangestelde Israëlische premier Benjamin Netanyahu een agressief beleid tegenover zijn buren: stopzetting van de vredesonderhandelingen met de Palestijnen, afzetting van Saddam Hoessein in Irak en ‘preventieve’ aanvallen tegen de Libanese Hezbollah, Syrië en Iran. Israël moest dus volgens dit rapport streven naar een grondige destabilisering van het Nabije Oosten om zijn strategische problemen op te lossen, doch Israël kon zo’n enorme ondernemingen niet aan.

In 1998 schreef de neocon-denktank Project for the New American Century een brief aan president Clinton om Irak binnen te vallen. Deze brief was ondertekend door een reeks vooraanstaande neocons: Elliott Abrams, Richard Armitage, John Bolton, Zalmay Khalilzad, William Kristol, Richard Perle, Donald Rumsfeld, Paul Wolfowitz en Robert Zoellick. Dit toont nogmaals aan dat deze ideeën bij het aantreden van de regering-Bush jr. zeker niet uit het niets kwamen.

De obsessie der neocons voor het Nabije Oosten is te herleiden tot hun liefde voor Israël. Veel neocons zijn immers van joodse afkomst en voelen zich verbonden met Israël en met de partij Likoed. De neocons menen verder dat in de unipolaire wereld van na de Koude Oorlog de VS zijn militaire macht moet gebruiken om zelf niet bedreigd te worden en om de parlementaire democratie en het kapitalisme te verspreiden. Ook het begrip ‘regime change’ komt van hen.

Hoewel de presidenten Reagan en Bush sr. al neocon-ideeën overnamen, triomfeerde het neoconservatisme pas echt onder president George Bush jr. (°1946), wiens buitenlands en militair beleid volledig gedomineerd werd door neocons. Tijdens de zomer van 1998 ontmoette Bush jr. op voorspraak van Bush sr. diens voormalige adviseur voor Sovjet- en Oost-Europese Zaken Condoleeza Rice op het landgoed van de familie Bush in Maine. Dit leidde er toe dat Rice Bush jr. zou adviseren inzake buitenlands beleid tijdens zijn verkiezingscampagne. Hetzelfde jaar werd ook Wolfowitz aangetrokken. Begin 1999 vormde zich een volwaardige adviesgroep voor buitenlands beleid, die grotendeels afkomstig was uit de regeringen-Reagan en -Bush sr. De door Rice geleide groep omvatte verder Richard Armitage (ex-ambassadeur en ex-geheim agent), Robert Blackwill (ex-adviseur voor Europese en Sovjetzaken), Stephen Hadley (ex-adviseur voor defensie), Lewis Libby (ex-medewerker van de ministeries van Buitenlandse Zaken en Defensie), Richard Perle (adviseur voor defensie), George Schultz (ex-adviseur van president Eisenhower, ex-minister van Arbeid, Financiën en Buitenlandse Zaken, hoogleraar en zakenman), Paul Wolfowitz (ex-medewerker van de ministeries van Buitenlandse Zaken en Defensie), Dov Zakheim (ex-adviseur voor defensie), Robert Zoellick (ex-adviseur voor en ex-viceminister van Buitenlandse Zaken). Bush jr. wou op deze manier zijn gebrek aan buitenlandse ervaring ondervangen. Deze adviesgroep voor buitenlands beleid kreeg tijdens de verkiezingscampagne in 2000 de naam ‘Vulcans’ toebedeeld.

Na Bush’ verkiezingsoverwinning kregen bijna alle Vulcans belangrijke functies in zijn regering: Condoleeza Rice (nationaal veiligheidsadviseur en later Minister van Buitenlandse Zaken), Richard Armitage (viceminister van Buitenlandse Zaken), Robert Blackwill (ambassadeur en later veiligheidsadviseur), Stephen Hadley (veiligheidsadviseur), Lewis Libby (stafchef van vicepresident Cheney), Richard Perle (bleef adviseur voor defensie), Paul Wolfowitz (viceminister van Defensie en later voorzitter van de Wereldbank), Dov Zakheim (opnieuw adviseur voor defensie), Robert Zoellick (presidentieel vertegenwoordiger voor Handelsbeleid en later viceminister van Buitenlandse Zaken).

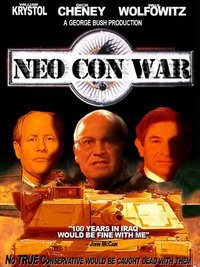

Ook andere neocons kregen hoge functies: Cheney werd vicepresident, terwijl Rumsfeld opnieuw minister van Defensie, John Bolton (°1948) viceminister van Buitenlandse Zaken, Elliot Abrams lid van de National Security Council en Doug Feith (°1953) presidentieel defensie-adviseur werden. Hierdoor was het Amerikaanse buitenlandse en militaire beleid volledig afgestemd op de geopolitieke belangen van Israël. Wolfowitz, Cheney en Rumsfeld waren de drijvende krachten achter de zogenaamde ‘Oorlog tegen het terrorisme’, die leidde tot de invasies van Afghanistan en van Irak.

Met het ‘Clean Break’-rapport uit 1996 (cfr. supra) was reeds 5 jaar vóór het aantreden van de regering-Bush jr. de blauwdruk van diens buitenlands beleid al ontworpen. Bovendien waren de 3 voornaamste auteurs van dit rapport – Perle, Feith en Wurmser – actief binnen deze regering als adviseur. Een herstructurering van het Nabije Oosten leek nu een stuk realistischer. De neocons stelden het voor alsof de belangen van Israël en de VS samenvielen. Het belangrijkste onderdeel van het rapport was de verwijdering van Saddam Hoessein als de eerste stap in de omvorming van het Israël-vijandige Nabije Oosten in een meer pro-Israëlische regio.

Diverse politieke analisten, waaronder de paleoconservatief Patrick Buchanan, wezen op de sterke overeenkomsten tussen het ‘Clean Break’-rapport en de 21ste eeuwse feiten: in 2000 blies de Israëlische leider Sharon de Oslo-akkoorden met de Palestijnen op door zijn provocatieve bezoek aan de Tempelberg, in 2003 bezette de VS Irak, in 2006 voerde Israël een (mislukte) oorlog tegen de Hezbollah en in 2011 werd Syrië ernstig bedreigd door Westerse sancties en door de VS gesteunde terreurgroepen. En daarnaast is er de aanhoudende oorlogsdreiging tegen Iran.

Vanaf 2002 beweerde president Bush jr. dat een uit Irak, Iran en Noord-Korea bestaande ‘As van het Kwade’ een gevaar voor de VS betekende. Dit moest bestreden worden door ‘preventieve’ oorlogen. De Straussianen waren van plan om in een eerste fase (hervorming van het Nabije Oosten) Afghanistan, Irak en Iran aan te vallen, in een tweede fase (hervorming van de Levant en Noord-Afrika) Libië, Syrië en Libanon en in een derde fase (hervorming van Oost-Afrika) Somalië en Soedan. Ook Podhoretz somde in Commentary deze reeks aan te vallen landen op. Het principe van een gelijktijdige aanval op Libië en Syrië werd reeds geconcipieerd in de week na de gebeurtenissen van 11 september 2001. Het werd voor het eerst publiekelijk vertolkt door viceminister van Buitenlandse Zaken John Bolton op 6 mei 2002 in zijn toespraak ‘Voorbij de As van het Kwade’. Voormalig NAVO-opperbevelhebber generaal Wesley Clark bevestigde dit nog eens op 2 maart 2007 in een televisie-interview, waarin hij tevens de lijst toonde van landen die achtereenvolgens zouden worden aangevallen door de VS in de volgende jaren.

Vanaf 2002 beweerde president Bush jr. dat een uit Irak, Iran en Noord-Korea bestaande ‘As van het Kwade’ een gevaar voor de VS betekende. Dit moest bestreden worden door ‘preventieve’ oorlogen. De Straussianen waren van plan om in een eerste fase (hervorming van het Nabije Oosten) Afghanistan, Irak en Iran aan te vallen, in een tweede fase (hervorming van de Levant en Noord-Afrika) Libië, Syrië en Libanon en in een derde fase (hervorming van Oost-Afrika) Somalië en Soedan. Ook Podhoretz somde in Commentary deze reeks aan te vallen landen op. Het principe van een gelijktijdige aanval op Libië en Syrië werd reeds geconcipieerd in de week na de gebeurtenissen van 11 september 2001. Het werd voor het eerst publiekelijk vertolkt door viceminister van Buitenlandse Zaken John Bolton op 6 mei 2002 in zijn toespraak ‘Voorbij de As van het Kwade’. Voormalig NAVO-opperbevelhebber generaal Wesley Clark bevestigde dit nog eens op 2 maart 2007 in een televisie-interview, waarin hij tevens de lijst toonde van landen die achtereenvolgens zouden worden aangevallen door de VS in de volgende jaren.

Bush jr. slaagde er door hevige tegenstand van diverse landen niet in om een resolutie van de VN-Veiligheidsraad tot stand te brengen voor een invasie van Irak. Dit leidde eind 2002 en begin 2003 zelfs tot een diplomatieke crisis. De neocons zagen de Irakoorlog als proeftuin: de VS zou proberen een parlementaire democratie te installeren in Irak om de Arabische vijandschap tegenover Israël te doen afnemen. Podhoretz pleitte in Commentary hevig voor het omverwerpen van Saddam Hoessein en prees president Bush jr., die ook het ABM-wapenbeperkingsverdrag met Rusland opzegde. Door het Amerikaanse fiasco in Irak verloor het neoconservatisme echter zijn invloed, waardoor het de tweede regering-Bush jr. veel minder domineerde.

Het buitenlands beleid van Bush jr. werd internationaal zeer zwaar bekritiseerd, vooral door Frankrijk, Oeganda, Spanje en Venezuela. Het anti-amerikanisme nam tijdens zijn presidentschap dan ook sterk toe. Ook de Democratische ex-president Jimmy Carter bekritiseerde Bush jarenlang voor een onnodige oorlog “gebaseerd op leugens en verkeerde interpretaties”.

In 2007 drong Podhoretz er op aan dat de VS Iran zou aanvallen, hoewel hij goed besefte dat dit het anti-amerikanisme in de hele wereld exponentieel zou doen toenemen.

5. Enkele neocon-denktanks

Neocons willen de parlementaire democratie en het kapitalisme internationaal verspreiden, óók in onstabiele regio’s en óók door middel van oorlog. Het American Enterprise Institute (AEI), de Heritage Foundation (HF) en het Project for the New American Century (PNAC) zijn hierbij de voornaamste denktanks.

5.1. American Enterprise Institute (AEI)

Het in 1943 opgerichte AEI streeft naar inkrimping van overheidsdiensten, een vrije markt, liberale democratie en een actief buitenlands beleid. Deze denktank werd gesticht door toplui van grote ondernemingen (onder meer Chemical Bank, Chrysler en Paine Webber) en wordt gefinancierd door bedrijven, stichtingen en particulieren. Tot op heden bestaat de raad van bestuur van het AEI uit toplui van multinationals en financiële ondernemingen, onder meer AllianceBernstein, American Express Company, Carlyle Group, Crow Holdings en Motorola.

Tot de jaren 1970 had het AEI weinig invloed in de Amerikaanse politiek. In 1972 startte het AEI echter met een onderzoeksafdeling en in 1977 deed de toetreding van ex-president Gerald Ford diverse toplui uit zijn regering in het AEI belanden. Ford bezorgde het AEI ook internationale invloed. Tevens begonnen diverse prominente neocons, zoals Irving Kristol, Gertrude Himmelfarb, Michael Novak, Benjamin Wattenberg en James Wilson, toen voor het AEI te werken. Tegelijk namen de financiële middelen en het personeelsbestand van het AEI exponentieel toe.

In de jaren 1980 traden diverse AEI-medewerkers in dienst van de regering-Reagan, waar zij een hard anti-USSR standpunt bepleitten. In de periode 1988-2000 versterkte het AEI zich met onder meer John Bolton, Lynne Cheney (echtgenote van Dick Cheney), Newt Gingrich, Frederick Kagan (zoon van PNAC-medestichter Donald Kagan) en Richard Perle, terwijl de financiële middelen verder toenamen.

Het AEI werd vooral sinds het aantreden van de regering-Bush jr. belangrijk. Diverse AEI-medewerkers maakten immers deel uit van of werkten achter de schermen voor deze regering. Ook andere regeringsmedewerkers onderhielden goede contacten met het AEI. Deze denktank besteedde steeds veel aandacht aan het Nabije Oosten en was dan ook nauw betrokken bij de voorbereiding van de invasie van Irak en de daaropvolgende burgeroorlog. Daarnaast viseerde het AEI ook Iran, Noord-Korea, Rusland, Syrië, Venezuela en bevrijdingsbewegingen als Hezbollah. Tegelijk werd gepleit voor nauwere banden met landen met gelijkaardige belangen, zoals Australië, Colombia, Georgië, Groot-Brittannië, Israël, Japan, Mexico en Polen.

5.2. Heritage Foundation (HF)

De HF werd in 1973 opgericht door Joseph Coors (1917-2003), Edwin Feulner (°1941) en Paul Weyrich (1942-2008) uit ontevredenheid over Nixons beleid. Zij wilden hiermee nadrukkelijk het overheidsbeleid in een andere richting sturen. De ondernemer Coors was geldschieter van de Californische gouverneur en latere Amerikaanse president Reagan. Hij voorzag met 250.000 dollar tevens het eerste jaarbudget van de nieuwe denktank. De liberaal-katholieken Feulner en Weyrich waren adviseurs van Republikeinse parlementsleden. In 1977 werd de invloedrijke Feulner hoofd van de HF. Door het uitbrengen van beleidsadviezen – toen een volkomen nieuwe tactiek in het wereldje van Washingtons denktanks – wekte hij nationale interesse voor de HF.

De HF was een belangrijke motor achter de opkomst van het neoconservatisme en focust vooral op economisch liberalisme. Met ‘erfgoed’ (heritage) wordt het joods-protestantse gedachtegoed en het liberalisme bedoeld. Deze denktank promoot dan ook de vrije markt, inkrimping van overheidsdiensten, individualisme en een sterke defensie. De HF wordt gefinancierd door bedrijven, stichtingen en particulieren.

De regering-Reagan werd sterk beïnvloed door ‘Mandate for Leadership’, een boek van de HF uit 1981 over inkrimping van overheidsdiensten. Ook ging de VS onder invloed van de HF actief anti-USSR verzetsgroeperingen in de hele wereld en Oostblokdissidenten ondersteunen. Het begrip ‘Rijk van het Kwade’ waarmee de USSR in deze periode omschreven werd, komt eveneens van de HF.

De HF ondersteunde tevens krachtig het buitenlands beleid van president Bush jr. en diens invasie van Irak. Diverse HF-medewerkers oefenden voorts functies uit in zijn regering, zoals Paul Bremer (°1941) die gouverneur van het bezette Irak werd. Eind 2001 richtte de HF de Homeland Security Task Force op, die de contouren uittekende voor het nieuwe ministerie van Binnenlandse Veiligheid.

Ook heden blijft de HF nog steeds één der invloedrijkste Amerikaanse denktanks. Zo keurde de HF in 2010 de hernieuwing van het START-wapenbeperkingsverdrag tussen de VS en Rusland af.

5.3. Project for the New American Century (PNAC)

Het PNAC werd in 1997 opgericht door het New Citizenship Project en heeft de internationale hegemonie der VS tot doel. Het wil dit bereiken door militaire kracht, diplomatie en morele principes. Het 90 bladzijden tellende PNAC-rapport ‘Rebuilding America’s Defenses’ uit september 2000 stelde de afwezigheid vast van een “catastrophic and catalyzing event like a new Pearl Harbor” en noemde tevens 4 militaire doeleinden: het beschermen van de VS, het overtuigend winnen van meerdere oorlogen, optreden als internationale politieagent en hervorming van het leger. Het PNAC lobbyde voor deze doelstellingen zeer intensief bij Amerikaanse en Europese politici.

Onder de 25 oprichters van het PNAC bevonden zich onder meer John Bolton (topambtenaar onder Reagan en Bush sr.), Jeb Bush (gouverneur van Florida en broer van president Bush jr.), Dick Cheney (stafchef van het Witte Huis onder Ford en minister van Defensie onder Bush sr.), Elliot Cohen (hoogleraar politicologie), Midge Decter (journaliste, schrijfster en echtgenote van Podhoretz), Steve Forbes (hoofd van Forbes Magazine), Aaron Friedberg (hoogleraar internationale politiek), Francis Fukuyama (hoogleraar filosofie, politicologie en sociologie), Donald Kagan (hoogleraar geschiedenis), Zalmay Khalilzad (medewerker van de ministeries van Buitenlandse Zaken onder Reagan en van Defensie onder Bush sr.), William Kristol (hoofdredacteur van het neocon-blad The Weekly Standard), John Lehman (staatssecretaris voor de Marine onder Reagan en zakenman), Lewis Libby (medewerker van de ministeries van Buitenlandse Zaken onder Reagan en van Defensie onder Bush sr.), Norman Podhoretz (hoofdredacteur van het neocon-blad Commentary), Dan Quayle (vicepresident onder Bush sr.), Donald Rumsfeld (stafchef van het Witte Huis en minister van Defensie onder Ford, presidentieel adviseur onder Reagan en adviseur bij het ministerie van Defensie onder Bush sr.) en Paul Wolfowitz (medewerker van het ministerie van Defensie onder Ford en adviseur voor de ministeries van Buitenlandse Zaken onder Reagan en van Defensie onder Bush sr.). Later traden ook Richard Perle (adviseur bij het ministerie van Defensie) en George Weigel (bekende progressief-katholieke publicist en politiek commentator) toe.

Het PNAC is een zeer omstreden organisatie omdat het dominantie van de wereld, de ruimte en het internet door de VS in de 21ste eeuw voorstaat. Tegenreactie kwam er met het BRussels Tribunal en From the Wilderness. Het burgerinitiatief BRussels Tribunal werd in 2004 opgericht door onder meer cultuurfilosoof Lieven De Cauter (KULeuven) en verzet zich tegen het buitenlands beleid van de VS. Het weest dan ook het PNAC en de Amerikaanse bezetting van Irak af. BRussels Tribunal klaagde tevens de moordcampagne tegen Iraakse academici en de vernietiging van Iraks culturele identiteit door het Amerikaanse leger aan. From the Wilderness meent dat het PNAC de wereld wil veroveren en dat de aanslagen van 11 september 2011 opzettelijk werden toegelaten door leden der Amerikaanse regering met het oog op de verovering van Afghanistan en Irak en het inperken der vrijheden in de VS.

In zijn bekende boek ‘The End of History and the Last Man’ uit 1992 poneerde hoogleraar en PNAC-medestichter Francis Fukuyama dat na de teloorgang der USSR de geschiedenis geëindigd was en voortaan het kapitalisme en parlementaire democratieën zouden triomferen. Dit boek was voor de regering-Bush jr. een rechtvaardiging voor de invasie van Irak en tevens een der voornaamste inspiratiebronnen van het PNAC. Fukuyama klaagde echter in zijn boek ‘America at the Crossroads: Democracy, Power and the Neoconservative Legacy’ uit 2006 de machthebbers in het Witte Huis aan. Hij stelde dat de VS door de Irakoorlog internationaal aan geloofwaardigheid en autoriteit inboette. Wereldwijd en vooral in het Nabije Oosten werd het anti-amerikanisme er sterk door aangewakkerd. Bovendien had de VS geen stabiliseringsplan voor het bezette Irak. Fukuyama stelt tevens dat de retoriek van de regering-Bush jr. over de “internationale oorlog tegen het terrorisme” en over de “islamitische bedreiging” zwaar overdreven is. Toch blijft Fukuyama een overtuigde neocon die wereldwijde democratisering onder leiding van de VS nastreeft. Wel verweet hij de regering-Bush jr. haar unilaterale werkwijze en haar ‘preventieve’ oorlogsvoering om de liberale democratie te verspreiden. De voordien door de VS toegepaste regimewissels werden daardoor veronachtzaamd. Fukuyama wil daarom het neocon-buitenlandbeleid voortzetten op een bedachtzame wijze die geen vrees of anti-amerikanisme opwekt bij andere landen.

6. Een aantal neocon-topfiguren

Elliot Abrams werd in 1948 geboren in een joods gezin in New York en is de schoonzoon van Norman Podhoretz. Abrams werkte als adviseur inzake buitenlands beleid voor de Republikeinse presidenten Reagan en Bush jr. Tijdens de regering-Reagan raakte hij in opspraak door het verborgen houden van de wreedheden van pro-Amerikaanse regimes in Centraal-Amerika en van de Contra’s in Nicaragua. Abrams werd uiteindelijk veroordeeld voor het achterhouden van informatie en het afleggen van valse verklaringen aan het Amerikaanse parlement. Tijdens de regering-Bush jr. was hij presidentieel adviseur voor het Nabije Oosten en Noord-Afrika en inzake de wereldwijde verspreiding van democratie. Volgens de Britse krant The Observer was Abrams ook betrokken bij de mislukte couppoging tegen de Venezolaanse president Hugo Chavez in 2002.

De in 1953 geboren Jeb Bush stamt uit de rijke protestantse ondernemersfamilie Bush, die ook de presidenten Bush sr. (zijn vader) en Bush jr. (zijn broer) voortbracht. Jeb Bush was in 1997 medestichter van het Project for the New American Century. In 1999-2007 was hij gouverneur van Florida met de steun van zowel de Cubaanse als de niet-Cubaanse Latino’s, evenals van de joodse gemeenschap in Florida.

De protestantse zionist Dick Cheney werd in 1941 geboren in Nebraska. Na studies aan de Yale University en de University of Wisconsin begon hij in 1969 te werken onder presidentieel medewerker Donald Rumsfeld. In de volgende jaren bekleedde Cheney diverse andere functies in het Witte Huis om in 1974 adviseur van president Ford te worden. In 1975 werd hij stafchef van het Witte Huis.

Als minister van Defensie in de regering-Bush sr. (1989-1993) leidde Cheney de Golfoorlog van 1990-1991 tegen Irak en installeerde daarbij militaire bases in Saoedi-Arabië. Na 1993 engageerde hij zich in het American Enterprise Institute en in het Jewish Institute for National Security Affairs. In 1995-2000 stond Cheney aan het hoofd van de energiereus Halliburton.

Onder Bush jr. was Cheney in 2000-2008 vicepresident en kon tevens Rumsfeld tot minister van Defensie laten benoemen. Hij slaagde er echter niet in om Wolfowitz de leiding van de CIA te bezorgen (cfr. infra). Om de oorlogen in Afghanistan en Irak te rechtvaardigen droeg Cheney aanzienlijk bij aan de ontwikkeling van het concept ‘Oorlog tegen het Terrorisme’ en aan de valse beschuldigingen van massavernietigingswapens. Cheney was de machtigste en invloedrijkste vicepresident ooit in de Amerikaanse geschiedenis. Hij en Rumsfeld ontwikkelden tevens een martelprogramma voor krijgsgevangenen. Cheney beïnvloedde ook de belastingheffing en de begroting enorm. Na zijn aftreden bekritiseerde hij het veiligheidsbeleid van de regering-Obama sterk.

Doug Feith werd in 1953 geboren in Philadelphia als zoon van de zionistische joodse zakenman Dalck Feith, die in 1942 van Polen naar de VS emigreerde. Feith werd na studies aan de Harvard University en de Georgetown University hoogleraar veiligheidsbeleid aan deze laatste universiteit. Daarnaast schreef hij zeer pro-Israëlische bijdragen voor onder meer Commentary en de Wall Street Journal. Feith kantte zich hevig tegen de détente met de USSR, het ABM-wapenbeperkingsverdrag en het Camp David-vredesakkoord tussen Egypte en Israël. Hij verdedigt voorts intensief de Amerikaanse steun aan Israël.

Feith behoorde in 1996 tot de opstellers van het omstreden rapport ‘A Clean Break: A New Strategy for Securing the Realm’, dat agressieve beleidsaanbevelingen formuleerde voor toenmalig Israëlisch premier Netanyahu. In 2001 werd Feith benoemd tot defensie-adviseur van president Bush jr. In 2004 werd hij door het FBI ondervraagd op verdenking van het doorspelen van geheime informatie aan de zionistische lobbygroep AIPAC. Heden is Feith medewerker van de denktank Jewish Institute for National Security Affairs, die een hecht bondgenootschap tussen de VS en Israël bepleit.

De in 1947 in New Jersey geboren Steve Forbes werd in 1985 door president Reagan benoemd tot hoofd van de CIA-radiozenders Radio Free Europe en Radio Liberty, die tijdens de Koude Oorlog Amerikaanse propaganda uitzonden in diverse talen in het Oostblok. Reagan vergrootte het budget van deze anti-USSR radiozenders en deed hen meer kritiek uiten op de USSR en zijn satellietstaten.

De pro-Israëlische Forbes was in 1997 medestichter van het Project for the New American Century en zetelt tevens in de raad van bestuur van de Heritage Foundation. Hij bepleit vrijhandel, inkrimping van overheidsdiensten, strenge criminaliteitswetgeving, legalisering van drugs, homohuwelijk en inperking van de sociale zekerheid. Heden is hij hoofd van zijn eigen blad Forbes Magazine.

De joodse hoogleraar internationale politiek Aaron Friedberg (°1956) was in 1997 medestichter van het Project for the New American Century. In 2003-2005 was hij adviseur veiligheidszaken en directeur beleidsplanning van vicepresident Cheney.

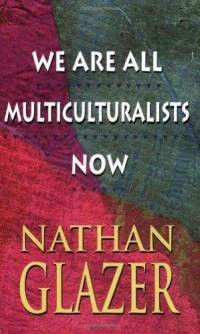

Nathan Glazer werd in 1924 geboren als zoon van joodse immigranten uit Polen. Hij studeerde in het begin der jaren 1940 aan het City College of New York, dat toen een marxistisch anti-USSR broeinest was. Glazer leerde er diverse uit Oost-Europa afkomstige joodse trotskisten kennen, zoals Daniel Bell (1919-2011), Irving Howe (1920-1993) en Irving Kristol.

Glazer was topambtenaar in de regeringen-Kennedy en –Johnson. In 1964 werd hij hoogleraar sociologie aan de University of California en in 1969 aan de Harvard University. Samen met zijn collega-hoogleraar sociologie Daniel Bell (een der belangrijkste naoorlogse joodse intellectuelen in de VS) en Irving Kristol stichtte Glazer in 1965 het invloedrijke tijdschrift The Public Interest. Glazer was tevens een sterk promotor van het multiculturalisme.

Donald Kagan werd in 1932 geboren in een joods gezin in Litouwen, maar groeide op in Brooklyn, New York. De trotskist Kagan werd in de jaren 1970 een neocon en was in 1997 een der stichters van het Project for the New American Century. Hij was eerst hoogleraar geschiedenis aan de Cornell University en vervolgens aan de Yale University.

De Afghaan Zalmay Khalilzad (° 1951) studeerde aan de American University of Beyrut en aan de University of Chicago. Aan deze laatste universiteit leerde hij de prominente nucleaire strateeg, presidentieel adviseur en hoogleraar Albert Wohlstetter kennen, die hem introduceerde in regeringskringen. Khalilzad is gehuwd met de joodse feministe en politieke analiste Cheryl Benard (°1953). Hij stichtte in Washington DC het internationale zakenadvieskantoor Khalilzad Associates, dat werkt voor bouw- en energiebedrijven.

In 1979-1989 was Khalilzad hoogleraar politieke wetenschappen aan de Columbia University. In 1984 werkte hij voor Wolfowitz op het ministerie van Buitenlandse Zaken en in 1985-1989 was hij regeringsadviseur inzake de Sovjetoorlog in Afghanistan en de Iran-Irakoorlog. In die periode werkte Khalilzad nauw samen met de strateeg Zbigniew Brzezinski, die de Amerikaanse steun aan de Afghaanse mudjaheddin uitgewerkt had. In 1990-1992 werkte hij bij het ministerie van Defensie.

Khalilzad was in 1997 medestichter van het Project for the New American Century. In 2001 was hij adviseur van president Bush jr. en lid van de National Security Council. Khalilzad was ambassadeur in Afghanistan in 2002-2005, in Irak in 2005-2007 en bij de VN in 2007-2009.

De in Oklahoma geboren Jeane Kirkpatrick (1926-2006) studeerde politieke wetenschappen aan de Columbia University en aan het Franse Institut des Sciences Politiques. Onder invloed van haar marxistische grootvader was Kirkpatrick toen lid van de Young People’s Socialist League (de jongerenafdeling van de Socialist Party of America). Aan de Columbia University werd ze sterk beïnvloed door de joodse marxistische hoogleraar politicologie Franz Neumann (1900-1954), die voordien in Duitsland in de SPD actief was geweest.

Vanaf 1967 doceerde Kirkpatrick aan de Georgetown University. In de jaren 1970 trad ze toe tot de Democratische Partij, waar ze nauw samenwerkte met senator Henry Jackson. Kirkpatrick raakte echter ontgoocheld in de Democraten vanwege de détente tegenover de USSR. Haar Kirkpatrick-doctrine, die Amerikaanse steun aan Derde Wereld-dictaturen goedpraatte en beweerde dat dit op lange termijn tot democratie zou kunnen leiden, raakte bekend door haar artikel ‘Dictatorships and Double Standards’ in Commentary in 1979. De Republikeinse president Reagan maakte haar daarom in 1981 lid van de National Security Council en ambassadeur bij de VN. De sterk pro-Israëlische Kirkpatrick verzette zich als ambassadeur bij de VN tegen iedere poging tot oplossing van het Arabisch-Israëlisch conflict. In 1985 nam ze ontslag en werd opnieuw hoogleraar aan de Georgetown University. Daarnaast was Kirkpatrick ook verbonden aan het American Enterprise Institute.

De in 1952 in New York geboren William Kristol is de zoon van de joodse neocon-peetvader Irving Kristol en historica Gertrude Himmelfarb. Kristol doceerde aanvankelijk aan de University of Pennsylvania en aan de Harvard University. In 1981-1989 was hij stafchef van minister William Bennet in de regering-Reagan en in 1989-1993 stafchef van vicepresident Dan Quayle in de regering-Bush sr. Zijn in deze laatste functie verworven bijnaam ‘Dan Quayle’s brain’ geeft aan dat Kristol een aanzienlijke invloed uitoefende.

Kristol is actief in diverse neocon-organisaties. Zo was hij in 1997-2005 voorzitter van het New Citizen Project, waardoor hij in 1997 tevens medestichter van het Project for the New American Century was en uiteraard ook de invasie van Irak verdedigde. Hij is tevens bestuurslid van het Emergency Committee for Israel’s Leadership, een neocon-lobbygroep die weerwerk levert tegen Israël-kritische parlementsleden.

Heden is Kristol politiek commentator bij de televisiezender Fox News en hoofdredacteur van de door hem gestichte neocon-periodiek The Weekly Standard. Hij pleit al jarenlang hevig voor een Amerikaanse aanval op Iran en bekritiseerde in 2010 de “lauwe aanpak van Iran” door president Obama. Ook de Amerikaanse militaire actie tegen Libië in 2011 werd door hem actief gesteund.

De in 1942 in Philadelphia geboren zakenman John Lehman was tijdens de regering-Reagan staatssecretaris voor de Marine (1981-1987). Sindsdien is hij actief in diverse neocon-denktanks, zoals het Project for the New American Century, de Heritage Foundation, het Committee on the Present Danger, …

Lewis Libby (°1950) stamt uit een rijke joodse bankiersfamilie uit Connecticut. Na studies politieke wetenschappen aan de Yale University en rechten aan de Columbia University lanceerde de bevriende Yale-professor Paul Wolfowitz vervolgens zijn advocatencarrière. Libby werkte voor Wolfowitz op het ministerie van Buitenlandse Zaken in 1981-1985 en op het ministerie van Defensie in 1989-1993.

In 1997 was Libby medestichter van het Project for the New American Century. Tijdens de verkiezingscampagne van Bush jr. behoorde hij tot de neocon-adviesgroep Vulcans. In 2001 werd Libby adviseur van president Bush jr., evenals stafchef en adviseur van vicepresident Cheney. Hij werd beschouwd als de meest fervente vertegenwoordiger der Israëllobby in de regering-Bush jr. De Britse minister van Buitenlandse Zaken Jack Straw zei zelfs over Libbys betrokkenheid bij de Israëlisch-Palestijnse onderhandelingen: “It’s a toss-up whether he is working for the Israelis or the Americans on any given day”.

In 2005 nam Libby ontslag nadat hij gedagvaard werd wegens meineed, het afleggen van valse verklaringen en het belemmeren van het gerechtelijk onderzoek in de zaak-Plame. In 2007 werd Libby schuldig bevonden en veroordeeld tot 2,5 jaar gevangenisstraf, 400 uur gemeenschapsdienst en een boete van 250.000 dollar. De gevangenisstraf werd echter door president Bush jr. kwijtgescholden.

De liberaal-katholiek Michael Novak (°1933) is van Slovaakse afkomst. Zijn progressieve geschriften over het Tweede Vaticaans Concilie, dat hij als journalist bijwoonde, werden zeer zwaar bekritiseerd door conservatieve katholieken. Het leverde hem wel de sympathie op van de protestantse theoloog Robert McAfee, die hem in 1965 aan een professoraat aan de Stanford University hielp.

In 1968 werd Novak benoemd aan de State University of New York. In 1973-1976 werkte hij voor de Rockefeller Foundation om daarna hoogleraar aan de Syracuse University te worden. In 1981-1982 zetelde Novak namens de VS in de VN-Commissie voor Mensenrechten. In 1986 leidde hij de Amerikaanse delegatie op de Conferentie voor Veiligheid & Samenwerking in Europa (CVSE). In 1987-1988 was Novak hoogleraar aan de University of Notre Dame. Sinds 1978 is hij ook verbonden aan het American Enterprise Institute. Zijn publicaties handelen over kapitalisme, democratisering en toenadering tussen protestanten en katholieken.

Richard Perle werd in 1941 in een joods gezin in New York geboren, maar groeide op in Californië. Na zijn studies politieke wetenschappen aan de University of Southern California, aan de London School of Economics en aan de Princeton University werkte Perle in 1969-1980 voor de Democratische senator Henry Jackson, voor wie hij het Jackson-Vanik-amendement opstelde dat détente met de USSR afhankelijk maakte van de mogelijkheid tot emigratie voor Sovjetjoden. Perle leidde ook het verzet tegen de ontwapeningsgesprekken van de regering-Carter met de USSR. In 1987 bekritiseerde hij het INF-ontwapeningsverdrag van de regering-Reagan met de USSR, evenals in 2010 de hernieuwing door de regering-Obama van het START-wapenbeperkingsverdrag met Rusland.

Perle werd er regelmatig van beschuldigd in werkelijkheid voor Israël te werken en er zelfs voor te spioneren. Al in 1970 betrapte het FBI hem er op geheime informatie te bespreken met iemand van de Israëlische ambassade. In 1983 lekte uit dat hij aanzienlijke geldsommen ontving om de belangen van een Israëlische wapenproducent te dienen.

Perle werkte in 1987-2004 als adviseur bij het ministerie van Defensie en is lid van diverse neocon-denktanks, zoals het American Enterprise Institute, het Project for the New American Century en het Jewish Institute for National Security Affairs. Hij verdedigde ook vurig de Amerikaanse invasie in Irak en behoorde in 1996 tot de auteurs van het controversiële rapport ‘A Clean Break: A New Strategy for Securing the Realm’, dat beleidsadviezen vervatte voor toenmalig Israëlisch premier Netanyahu.

De omstreden historicus Richard Pipes (° 1923) is de zoon van een joodse zakenman uit Polen. Het gezin Pipes immigreerde in 1940 in de VS. Na zijn studies aan Muskingum College, de Cornell University en de Harvard University doceerde Pipes in 1950-1996 Russische geschiedenis aan de Harvard University. Hij schreef tevens voor Commentary. Tijdens de jaren 1970 bekritiseerde Pipes de détente met de USSR en adviseerde hij senator Henry Jackson. In 1976 leidde Pipes de controversiële studiegroep Team B, die de geopolitieke capaciteiten en doelstellingen der USSR moest herbekijken. In 1981-1982 was hij lid van de National Security Council. Pipes was ook jarenlang lid van de necon-denktank Committee on the Present Danger.

Pipes’ wetenschappelijk werk is echter omstreden in de academische wereld. Critici stellen dat zijn historisch werk louter tot doel heeft om de USSR te bestempelen als het ‘Rijk van het Kwade’. Daarnaast schreef hij voluit over Lenins zogezegde “onuitgesproken veronderstellingen”, terwijl hij volkomen negeerde wat Lenin effectief heeft gezegd. Pipes wordt voorts beschuldigd van het selectief gebruik van documenten: wat in zijn kraam paste, werd uitgebreid beschreven en wat niet in zijn kraam paste, werd gewoon over het hoofd gezien. Ook de Russische schrijver en intellectueel Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn wees Pipes werk af als “de Poolse versie van de Russische geschiedenis”.

Dan Quayle werd in 1947 geboren in Indiana als kleinzoon van de vermogende en invloedrijke krantenmagnaat Eugene Pulliam. Na studies politieke wetenschappen aan de DePauw University en rechten aan de Indiana University zetelde Quayle vanaf 1976 in het Amerikaanse parlement. In 1989-1993 was hij vicepresident onder Bush sr. De investeringsbankier Quayle was in 1997 medestichter van het Project for the New American Century. Hij zetelt verder in diverse raden van bestuur van grote bedrijven en is bestuurder bij de Aozora Bank in Japan. Quayle schrijft ook een column die in diverse Amerikaanse kranten verschijnt.

De in 1932 in Illinois geboren Donald Rumsfeld was in 1954-1957 marinepiloot en vlieginstructeur bij de Amerikaanse marine. Daarna was hij medewerker van 2 parlementsleden (tot 1960) en van een investeringsbank (tot 1962), waarna hij Republikeins parlementslid werd. In 1969-1972 was Rumsfeld presidentieel adviseur van Nixon. In 1973 was hij ambassadeur bij de NAVO in Brussel.

Rumsfeld werd in 1974 stafchef van het Witte Huis onder president Ford. Op zijn instigatie herschikte Ford in november 1975 zijn regering grondig (wat later de naam ‘Halloween Massacre’ kreeg). Rumsfeld werd minister van Defensie. Hij stopte de geleidelijke daling van het defensiebudget en versterkte de nucleaire en conventionele bewapening der VS, waardoor hij Buitenlandminister Kissingers SALT-onderhandelingen met de USSR ondermijnde. Rumsfeld greep het controversiële rapport van Team B uit 1976 aan om kruisraketten en een groot aantal marineschepen te bouwen.

Na het aantreden van de Democratische regering-Carter in 1977 doceerde Rumsfeld kort aan de Princeton University en de Northwestern University in Chicago om daarna topfuncties in het zakenleven op te nemen. Onder Reagan was hij in 1982-1986 presidentieel adviseur voor wapenbeheersing en kernwapens en in 1982-1984 presidentieel gezant voor het Nabije Oosten en het Internationaal Zeerechtverdrag. In de regering-Bush sr. was Rumsfeld in 1990-1993 adviseur bij het ministerie van Defensie. In 1997 was hij medestichter van het Project for the New American Century.

Onder president Bush jr. was Rumsfeld in 2001-2006 opnieuw minister van Defensie, waardoor hij de planning van de invasies van Afghanistan en Irak domineerde. Hij wordt zowel in de VS als internationaal verantwoordelijk geacht voor het opsluiten van krijgsgevangenen zonder bescherming van de Conventies van Genève, evenals voor de daaruit volgende martel- en misbruikschandalen in Abu Ghraib en Guantanamo. In 2009 werd Rumsfeld door de VN-Mensenrechtencommissie zelfs een oorlogsmisdadiger genoemd.

Benjamin Wattenberg werd in 1933 geboren in een joods gezin in New York. In 1966-1968 werkte hij als assistent en speechschrijver voor president Johnson. In 1970 tekende hij met politicoloog, verkiezingsspecialist en presidentieel adviseur Richard Scammon (1915-2001) de strategie uit die de Democraten de overwinning opleverde bij de parlementsverkiezingen van 1970 en die de Republikein Richard Nixon in 1972 opnieuw president maakte. In de jaren 1970 was Wattenberg adviseur van Democratisch senator Henry Jackson. Verder werkte hij als topambtenaar voor de presidenten Carter, Reagan en Bush sr. Heden is hij verbonden aan het American Enterprise Institute.

De hoogleraar politieke wetenschappen James Wilson (°1931) doceerde in 1961-1987 aan de Harvard University, in 1987-1997 aan de University of California, in 1998-2009 aan de Pepperdine University en daarna aan het Boston College. Daarnaast oefende hij diverse functies uit in het Witte Huis en was hij adviseur van enkele Amerikaanse presidenten. Wilson is ook gelieerd aan het American Enterprise Institute.

De toonaangevende neocon Paul Wolfowitz werd in 1943 in Brooklyn, New York geboren als zoon van joodse immigranten uit Polen. Zijn vader was professor statistiek en AIPAC-lid Jacob Wolfowitz (1910-1981), die de Sovjetjoden en Israël actief steunde. Wolfowitz studeerde eerst wiskunde aan de Cornell University in de jaren 1960, waar hij professor Allan Bloom leerde kennen en tevens lid was van de geheime studentengroepering Quil and Dragger. Tijdens zijn studies politieke wetenschappen aan de University of Chicago leerde hij de professoren Leo Strauss en Albert Wohlstetter kennen, evenals zijn medestudenten James Wilson en Richard Perle.

In 1970-1972 doceerde Wolfowitz politieke wetenschappen aan de Yale University, waar Lewis Libby een van zijn studenten was. Daarna was hij medewerker van senator Henry Jackson. In 1976 behoorde Wolfowitz tot de controversiële anti-USSR studiegroep Team B die de analyses der CIA inzake de USSR moest ‘herbestuderen’. In 1977-1980 was Wolfowitz medewerker van het ministerie van Defensie. In 1980 werd hij hoogleraar internationale betrekkingen aan de John Hopkins University.

In de regering-Reagan werd Wolfowitz in 1981 op voorspraak van John Lehman (°1942) medewerker van het ministerie van Buitenlandse Zaken. Hij wees Reagans toenadering tot China ten stelligste af, wat hem in conflict bracht met minister van Buitenlandse Zaken Alexander Haig (1924-2010). In 1982 voorspelde de New York Times dan ook dat Wolfowitz vervangen zou worden op het ministerie van Buitenlandse Zaken. In de plaats gebeurde in 1983 echter het omgekeerde: Haig – die ook overhoop lag met minister van Defensie Caspar Weinberger (1917-2006) – werd vervangen door de neocon George Schultz (°1920) en Wolfowitz werd gepromoveerd tot Schultz’ assistent voor Oost-Aziatische en Pacifische zaken. Lewis Libby en Zalmay Khalilzad werden medewerker van Wolfowitz. In 1986-1989 was Wolfowitz ambassadeur in Indonesië.

Tijdens de regering-Bush sr. (1989-1993) was Wolfowitz viceminister van Defensie onder minister Cheney met opnieuw Libby als zijn medewerker. Hierdoor waren zij nauw betrokken bij de oorlog tegen Irak in 1990-1991. Wolfowitz betreurde sterk dat de VS zich in deze oorlog beperkte tot de herovering van Koeweit en niet doorstootte naar Bagdad. Hij en Libby zouden heel de jaren 1990 door blijven lobbyen voor een ‘preventieve’ en unilaterale aanval tegen Irak.

In 1994-2001 was Wolfowitz opnieuw hoogleraar aan de John Hopkins University, waar hij zijn neocon-visie uitdroeg. In 1997 was hij medestichter van het Project for a New American Century.

Wolfowitz scheidde in 1999 van zijn vrouw Clare Selgin en begon een relatie met de Brits-Libanese Wereldbank-medewerkster Shaha Ali Riza, wat hem in 2000 en 2007 in de problemen zou brengen (cfr. infra). Tijdens de verkiezingscampagne van Bush jr. in 2000 behoorde Wolfowitz tot Bush’ adviesgroep voor buitenlands beleid Vulcans. Voor de daaropvolgende regering-Bush jr. werd Wolfowitz voorgedragen als hoofd van de CIA, doch dit mislukte doordat zijn ex-vrouw in een brief aan Bush jr. zijn relatie met een buitenlands burger een veiligheidsrisico voor de VS noemde. Hij werd dan maar in 2001-2005 opnieuw viceminister van Defensie onder minister Rumsfeld.

Wolfowitz maakte van de gebeurtenissen van 11 september 2001 handig gebruik om onmiddellijk opnieuw zijn retoriek over ‘massavernietigingswapens’ en ‘preventieve’ aanvallen tegen ‘terroristen’ boven te halen. Hij en Rumsfeld pleitten vanaf dan bij iedere gelegenheid voor een aanval op Irak. Omdat de CIA hun beweringen over ‘Iraakse massavernietigingswapens’ en ‘Iraakse steun aan terrorisme’ niet volgde, richtten zij binnen het ministerie van Defensie de studiegroep Office of Special Plans op om dit te staven. Dit OSP overvleugelde binnen de kortste keren de bestaande inlichtingendiensten en werd op basis van vaak dubieuze informatie de voornaamste inlichtingenbron van president Bush jr. inzake Irak. Dit leidde tot de beschuldiging dat de regering-Bush jr. inlichtingen creëerde om het parlement een invasie van Irak te doen goedkeuren.

In 2005 werd Wolfowitz door president Bush jr. met succes voorgedragen als voorzitter van de Wereldbank. Wolfowitz maakte zich echter onpopulair door een reeks omstreden benoemingen van neocons en het doordrukken van een neocon-beleid in de Wereldbank. Ook zijn affaire met Wereldbank-medewerkster Shaha Ali Riza leidde tot controverse daar de interne regels der Wereldbank relaties tussen leidinggevenden en personeel verbieden. Riza werd bovendien overgeplaatst naar het ministerie van Buitenlandse Zaken mét een buitenproportionele weddeverhoging. Uiteindelijk was Wolfowitz genoodzaakt om af te treden als voorzitter van de Wereldbank. Hij werd hierna onderzoeker bij het American Enterprise Institute.

7. Conclusie

Het neoconservatisme ontstond uit de virulente haat van uit Oost-Europa gevluchte joodse trotskisten voor én de stalinistische USSR én Rusland. Zij waren voornamelijk afkomstig van het grondgebied van het voormalige Pools-Litouwse rijk (Polen, Oekraïne en Litouwen). Deze joodse immigranten vestigden zich in de jaren 1920 en 1930 vooral in de New Yorkse stadsdelen Brooklyn en de Bronx. In de VS vormden zij een zeer hechte gemeenschap door vriendschappen, professionele relaties en huwelijken. Sommigen verengelsten ook hun familienaam, bijvoorbeeld ‘Leibowitz’ werd ‘Libby’ en ‘Piepes’ werd ‘Pipes’. Hun kinderen studeerden massaal aan het City College of New York en vormden de trotskistische groepering New York Intellectuals.

Om Stalin vanuit zijn Mexicaanse ballingschap te bestrijden vormde ex-Sovjetleider Leon Trotski met de Vierde Internationale een rivaliserende communistische beweging. Uit afkeer voor het stalinisme verzamelde zich in de jaren 1930 rond Trotski een aantal belangrijke Amerikaans-joodse radicaal-linkse intellectuelen, zoals de jonge communisten Irving Howe, Irving Kristol en Dwight MacDonald. In de jaren 1960 ruilden ze hun trotskisme in voor neoconservatisme.

De belangrijkste ideologen van het neoconservatisme zijn dus marxisten die zich heroriënteerden. De termen zijn veranderd, maar de doelstellingen bleven hetzelfde. De liberale thesen van het neoconservatisme ondersteunen immers evenzeer het universalisme, het materialisme en de maakbaarheidsutopie, omdat zowel marxisme als liberalisme zich op dezelfde filosofische fundamenten beroepen. De communisten zaten dus tijdens de Koude Oorlog eerder in New York dan in Moskou. Het neoconservatisme maakte tevens religie weer bruikbaar voor de Staat.

Neocons zijn democratische imperialisten die de maatschappij en de wereld willen veranderen. Hun messianisme en hun drang om wereldwijd de parlementaire democratie en het kapitalisme te verspreiden staan bovendien haaks op het conservatisme. Echte conservatieven hebben immers geen universele pretenties en verdedigen eerden non-interventionisme en isolationisme. Hun actieve steun aan Israël willen de neocons bovendien desnoods omzetten in militaire interventies in landen die zij gevaarlijk achten voor hun en Israëls belangen.

Het neocon-ideaal van multiculturalisme impliceert massa-immigratie. Culturen hebben echter een verschillend waarden-, normen- en wetgevend kader. Om sociale interactie mogelijk te maken is dus een gemene deler nodig. Bijgevolg is de finale doelstelling niet multiculturalisme, maar monoculturalisme: de neocons willen dus een eenvormige eenheidsmens creëren.

Onder de neocons bevinden zich opvallend veel intellectuelen. Ze zijn daardoor geen marginale groep, maar vormen integendeel het intellectuele kader van het Amerikaanse buitenlands beleid. President Richard Nixon had echter een heel andere benadering van de 2 grootmachten China en de USSR dan alle andere naoorlogse Amerikaanse presidenten. Tot woede der neocons knoopte hij betrekkingen aan met China en verbeterde de relaties met de USSR aanzienlijk. In de VS zelf decentraliseerde Nixon de overheid, bouwde de sociale zekerheid uit en bestreed de inflatie, de werkloosheid en de criminaliteit. Daarnaast schafte hij ook de goudstandaard af, terwijl zijn lonen- en prijzenbeleid de grootste overheidsingreep in vredestijd was in de Amerikaanse geschiedenis.

De neocons haatten de détente van de jaren 1970: ze vreesden hun favoriete vijand – de USSR – kwijt te spelen. Na Nixons aftreden wegens het Watergate-schandaal beweerden ze daarom dat de CIA veel te rooskleurige analyses over de USSR produceerde. De door hen geïnstigeerde regeringsherschikking van 1975 bracht George Bush sr. aan het hoofd van de CIA, waarna deze het a priori al anti-USSR ingestelde Team B oprichtte om een ‘alternatieve beoordeling’ van de CIA-gegevens te maken. Team B’s omstreden en volkomen foutieve rapport stelde onterecht dat de CIA het verkeerd voorhad.