History is the record of what men do. Scientific discoveries and technological applications of them are often events of historical importance, but do not affect our understanding of the historical process since they shed no light on the behavior of men in civilized societies.

History is the record of what men do. Scientific discoveries and technological applications of them are often events of historical importance, but do not affect our understanding of the historical process since they shed no light on the behavior of men in civilized societies.

For example, the recent use of atomic fission to produce a more powerful explosive has no significance for a philosophy of history. Like the many changes in the technology of war that have occurred throughout history, this one will call for changes in tactics and strategy, alters to some extent the balance of power in the world, and may well occasion the fall and extinction of a world power so fat-headed that it does not understand the importance of technological superiority in warfare. But all this is merely history repeating itself. It is true that the improved weapons set bands of addle-pated neurotics throughout the country shrieking as wildly as a tribe of banshees out on a week-end spree; but that is merely another instance of the rather puzzling phenomenon of mass hysteria. It is also true that Communist agents have been scurrying about the country to brandish the phrase “nuclear holocaust” as a kind of up-to-date Jack-o’-Lantern to scare children. But while it is the historian’s task to understand the International Conspiracy in the light of such partial precedents as are available, the new weapon will not help him in that. He will merely marvel that a large part of our population is not only ignorant of history in general, but evidently has not read even the Old Testament, from which it would have learned that atomic bombs, as instruments of extermination, are much less efficient that a tribe of Israelites armed with the simplest weapons (see Joshua vi. 20 et passim).

As an exception to the general rule, however, our century has brought one new area of knowledge in the natural sciences that must profoundly affect our understanding of history both past and present–that is as relevant to the rise and fall of the Mitanni and the Hittites as it is to our future. Distressingly enough, the new science of genetics raises for the historian many more questions than it answers, but it discloses the existence of a force that must be taken into account in any philosophy of history.

Multiplex Man

Civilized human beings have long been puzzled by the mysterious diversity of human beings. It is possible, indeed, that mystery was part of the process by which some people were able to rise from barbarism to civilization. The perception requires mental powers that are by no means universal. The aborigines of Australia, for example, who are probably the lowest from of human life still extant, have a consciousness so dim and rudimentary that they multiplied on that continent for fifty thousand years without ever suspecting that sexual intercourse had anything to do with reproduction. Most savages, to be sure, are somewhat above that level, but no tribe appears to have been aware of its own diversity, let alone capable of thinking about it.

Human beings capable of reflective thought, however, must have begun early to marvel, as we still do, at the great differences obvious among the offspring of one man by one woman. Of two brothers, one may be tall and the other short; one stolid and the other alert; one seemingly born with a talent for mathematics and the other with a love of music.

Many were the theories that men excogitated to explain so strange a phenomenon. One of the principal grounds for the once widespread and persistent belief in astrology was the possibility of explaining the differences between two brothers by noting that, although engendered by the same parents, they were conceived and born under different configurations of the planets. In the Seventeenth Century, indeed, Campanella, whose plan for a Welfare State is the source of many of our modern “Liberal” crotchets and crazes, devised a whole system of eugenics to be enforced by bureaucrats who would see to it that human beings were engendered only at moments fixed by expert astrologers.

Again, the doctrine of metempsychosis, once almost universally held over a wide belt of the earth from India to Scandinavia, seemed to be confirmed by the same observations; for the differences between brothers were understandable, if their bodies were animated by souls that had had far different experiences in earlier incarnations.

There were also some theoretical explanations, such as the one that you may remember having read in the stately verse of Lucretius, that were sound bases for scientific inquiry, but they were not followed up. Until the last third of the Nineteenth Century, men learned nothing of the basic laws of heredity. Darwin’s knowledge of the subject was no better than Aristotle’s, and Galton’s enthusiasm for eugenics was no more firmly founded than was Plato’s. It remained for a humble and too modest priest, Father Johann Gregor Mendel, to make one of the most important scientific discoveries ever made by man.

Father Mendel’s Versuche über Pflanzen hybriden was published in 1886, but the famous professors in the great universities could not take a mere priest seriously–certainly not a priest so impudent as to contradict Darwin–and so they went on for decades pawing over problems that father Mendel had made obsolete as the epicycles of Ptolemaic astronomy. He was simply ignored and forgotten until 1900, when three distinguished biologists discovered independently and almost simultaneously some of the laws that he had ascertained and formulated.

It required some time for systematic study of genetics to get under way, and research has been greatly impeded by two catastrophic World Wars and by the obscurantism of Communists and “Liberal intellectuals.”

In Russia and other territories controlled by the Conspiracy, Marx’s idiotic mumbo-jumbo is official doctrine and the study of genetics is therefore prohibited. There are, however, some indications that research may be going on secretly, and it is even possible that, so far as human genetics are concerned, the knowledge thus obtained may exceed our own; for the Soviet, though usually inept in scientific work, has facilities for experiments that civilized men cannot perform. In the mid-1930′s, for example, there were reports that experiment stations in Asiatic Russia had pens of human women whom the research workers were trying to breed with male apes in the hope of producing a species better adapted to life under Socialism than human beings. It was reported a few years ago that the Soviet is now trying to create subhuman mutations by exposing their human breeding stock to various forms of irradiation. One cannot exclude the possibility that the monsters who conduct such experiments may incidentally find some significant data.

In the United States, the situation differs somewhat from that in Russia. Geneticists are permitted to continue their studies in peace so long as they communicate only with one another and do not disclose to the public facts of which the American boobs must be kept ignorant. Since it requires rare courage to provoke a nest of “Liberal intellectuals” or rattlesnakes, the taboo thus imposed is generally observed.

Grim Genetics

Despite the restraints placed on scientific investigation, and despite the awesome complexity of genetic factors in so complicated a creature as man, it is now virtually certain that all of the physiological structure of human beings, including such details as color of eyes, acuity of vision, stature, susceptibility to specific diseases, and formation of the brain are genetically determined beyond possibility of modification or alteration except by physical injury or chemical damage. Some of the processes involved have been well ascertained; others remain unknown. No one knows, for example, why the introduction of minute quantities of fluorine into drinking water will prevent development of the brain in some children and so roughly double the number of mongolian idiots born in a given area.

It is far more difficult to investigate intellectual capacities, since these must involve a large number of distinct elements, no one of which can be physically observed; but all of the evidence thus far available indicates that intelligence is as completely and unalterable determined by genetic inheritance as physical traits.

Moral qualities are even more elusive than intellectual capacity. There is evidence which makes it seem extremely probable that criminal instincts, at least, are inherited, but beyond this we can only speculate by drawing an analogy between moral and intellectual potentialities.

Many persons find the conclusions thus suggested unpleasant, just as all of us, I am sure, would be much happier if the earth were the immobile center of the universe and the heavens revolved about it. But although vast areas in the new science of genetics remain unexplored, and although the complexity of many problems is such that we cannot hope to know in our lifetime many of the things that we most urgently need to know, the principles of heredity have been determined with a fairly high degree of scientific probability. They are, furthermore, in accord with what common sense has always told us and also with the rational perception of our place in the universe that underlies religion.

We can blind children, but we cannot give them sight. We can stunt their minds in “progressive” schools, but we cannot give them an intelligence they did not inherit at birth. It is likely that we can make criminals of them by putting them (like the somewhat improbable Oliver Twist) in Fagin’s gang or its equivalent, but we cannot induce a moral sense in one who was born without it. We have always known that it is easy for man to destroy what he can never create.

One Certainty

The Mendelian laws and hence the finding that human beings, physically and intellectually, at least, are absolutely limited to the potentialities they have inherited — which may be impaired by external action but cannot be increased — are the accepted basis of all serious biological study today. From the standpoint of scientific opinion, to deny heredity is about equivalent to insisting that the earth is flat or that tadpoles spring from the hair of horses.

The point is worth noting, for even if you choose to reject the findings of genetics, that science will enable you to demonstrate one very important truth.

Our “liberal intellectuals,” who have done all in their power to deride, defile, and destroy all religion, are now sidling about us with hypocritical whimpers that the facts of genetics ain’t “Christian.” This argument does work with those whose religion is based on the strange faith that God wouldn’t have dared to create a universe without consulting their wishes. But if you inquire of the “intellectual,” as though you did not know, concerning scientific evidence in these matters, the chances are that he will assure you, with a very straight face, that he is, as always, the Voice of Science. Thus you will know that he still is what he has always been: a sneak and a liar.

The Warp of Culture

Given the facts that all men are born unequal; that the inequality, apparent even among children of the same parents, increases with differences in genetic strains; that civilization, by the very fact of social organization and the variety of human activity thus made possible, accentuates such differences; and that the continuity of a culture depends on a more or less instinctive acceptance of the common values of that culture — given those facts, it becomes clear that historians who try to account for the rise and fall of civilizations by describing political, economic, philosophic, and religious changes without reference to genetic changes in the population are simply excluding what must have been a very important factor, however little we may be able to measure it in the past or the present.

Whatever should be true of statutory and often ephemeral enactments in human jurisprudence, it is undoubtedly true of all the laws of nature that ignorance of the law excuses no-one from the consequences of violating it. And it may be unjust, as it is certainly exasperating, that we must often act with only a partial and inaccurate knowledge of such laws. But that is a condition of life. Societies are like individuals in that they must make decisions as best they can on the basis of such information as is available to them. You may have stock in a corporation whose future you may find it very difficult to estimate, but you must decide either (a) to sell, or (b) to buy more, or (c) to hold what you have. What you cannot do is nothing.

The scope of genetic forces in the continuity of a civilization, and, more particularly, of Western civilization, and, especially, of that civilization in the United States was illustrated by one of the most brilliant of American writers, Dr. Lothrop Stoddard, in The Revolt Against Civilization (Scribner’s, New York, 1922). The book was out of print for many years, for our “liberal intellectuals” promptly decided that the subject was one that American boobs should not be permitted to think about, and accordingly shovelled their malodorous muck on both book and author, in the hope of burying both forever. Copies of it disappeared from many libraries, and the book became hard to find on the secondhand market (I obtained my copy from a dealer in Italy).

I commend The Revolt Against Civilization, not as a revelation of ultimate truth, but as a cogent and illuminating discussion of some very grim problems that we must face, if we intend to have a future. The book, you must remember, was written when problems in genetics seemed much simpler than they do now in the light of later research, and when Americans felt a confidence and an optimism that we of a later generation can scarcely reconstruct in imagination. Some parts of the book will seem quaint and old-fashioned. Dr. Stoddard assumes, for example, that the graduates of Harvard are a group intellectually and morally above the average: That probably was true when he was an undergraduate and when he took his doctorate; he did not foresee what loathesome and reptilian creatures would slither out of Harvard to infest the Dismal Swamp in Washington. And when he urged complete toleration of Communist talk (as distinct from violence), he was thinking of soap-box oratory in Bug-House Square and the shrill chatter of parlor-pinks over their teacups; he did not foresee penetration and capture of schools, churches, newspapers, and political organizations by criminals who disseminate Communist propaganda perfunctorily disguised as “progressive education,” “social gospel,” and “economic democracy.”

But the book remains timely. What were sins of omission in 1922, when we were, with feckless euphoria, repeating the blunders that destroyed past civilization, are now sins of commission, committed with deliberate and malicious calculation by the enemies whom we have given power over us. And we should especially perpend Dr. Stoddard’s distinction between the ignorant or overly-emotional persons who “blindly take Bolshevism’s false promises at their face value,” and the real Bolshevik, who “are mostly born and not made.” That dictum is as unimpeachable as the poeta nascitur, non fit, that it echoes.

The Optimistic Pessimist

Since Stoddard wrote, the horizons have darkened around us. A recent and stimulating book is Dr. Elmer Pendell’s The Next Civilization. The title may remind you of an article that Arthur Koestler published in the New York Times on November 7, 1943 — an article whose bleak pessimism startled all but the very few readers who were in a position to surmise, form the hints which Koestler was able to smuggle into the pages of the Times, that he, an ex-Communist, was able to estimate the extent to which the Communist Conspiracy had already taken control of the government of the United States. Koestler, stating flatly that we would soon be engulfed in a Dark Age of barbarism and indescribable horror, called for the establishment of monasteries that, like the monasteries of the early Middle Ages, would preserve some part of human culture as seed for a new Renaissance in some distant future. Dr. Pendell, although he does not entirely deny us hope for ourselves, is primarily concerned with preserving the better part of our genetic heritage as seed for a future civilization that may have the intelligence to avoid the follies by which we are decreeing our own doom.

Dr. Pendell very quickly reviews the historical theories of Brook Adams, Spengler, Toynbee, and others to show that they all disregard the fact that decline in a civilization is always accompanied by a change in the composition, and deterioration in the quality, of the population.

We know that such changes took place in every civilization of which we have record. The majority of Roman citizens in 100 A.D. were not related at all to the Roman citizens in 100 B.C. We know that the great Roman families died out from sheer failure to have enough children to reproduce themselves, and we have reason to believe that all classes of responsible Romans, regardless of social or economic position, followed the fashion of race suicide.

Since the Romans had the preposterous notion that any person of any race imported from any part of the world could be transformed into a Roman by some magic in the legal phrases by which he was made a Roman citizen, the children that the Romans did not have were replaced by a mass of very diverse origins. Some of the importations undoubtedly brought with them fresh vigor and talent; some were incapable of assimilating civilization at all and could only imitate its outer forms without understanding its meaning; and some, while by no mens inferior in intelligence and energy, had a temperament which, although eminently suited to some other civilization, was incompatible with the Roman. For some estimates of the deterioration of the population of the empire that the Romans founded, see the late Tenny Frank’s History of Rome (Holt, New York) and Martin P. Nilsson’s Imperial Rome (Schocken, New York).

When Dr. Stoddard wrote, we were merely behaving as thoughtlessly as the Romans: Carpe diem and let tomorrow take care of itself. But now, as Dr. Pendell hints and could have stated more emphatically, the power of government over us is being used, with a consistency and efficiency that must be intentional, to accelerate our deterioration and hasten our disappearance as a people by every means short of mass massacre that geneticists could suggest. To mention but one small example, many states now pick the pockets of their taxpayers to subsidize and promote the breeding of bastards, who, with only negligible exceptions, are the product of the lowest dregs of our population, the morally irresponsible and mentally feeble. An attorney informs me that in his state and others the rewards for such activity are so low that a female of this species has to produce about a dozen bastards before it can afford a Cadillac, and will have to go on producing to take care of the maintenance. Intensive breeding is therefore going on, and the legislation that was designed to stimulate it may therefore be said to be highly successful.

The United States is now engaged in an insane, but terribly effective, effort to destroy the American people and Western civilization by subsidizing, both at home and abroad, the breeding of the intellectually, physically, and morally unfit; while at the same time inhibiting, by taxation and in many other ways, the reproduction of the valuable parts of the population — those with the stamina and the will to bear the burden of high civilization. We, in our fatuity, but under the control of persons who must know that they are doing, are working to create a future in which our children, if we have any, will curse us for having given them birth.

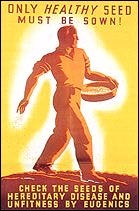

When Dr. Pendell tells us what we must do, if we are to survive or even if we limit ourselves to the more modest hope that human civilization may survive on our planet, is to reverse the process — to encourage the reproduction of the superior stock and to check the multiplication of the inferior — he is unquestionably right. He may also be right when he urges that we must do more than desist from interfering with nature for the purpose of producing biological deterioration — that we must, instead, interfere with nature to ameliorate and improve our race. But here, I fear, Dr. Pendell, although he almost despairs of our civilization and looks to the next one, is yet too optimistic. There are two practical difficulties.

Our Coup d’Etat

Dr. Pendell proposes voluntary eugenic associations and “heredity corporations,” which, no doubt, would help a little, as he argues, but which, as he is aware, would not have much more effect than a few buckets of water thrown into the crater of Mauna Loa. At this late date, to accomplish much for ourselves or even for our putative successors, we must use at least the taxing power of government, if not its powers of physical coercion, to induce or compel the superior to have children and to prevent the inferior from proliferating. So here enters on the stage that most unlovely product of human evolution, the bureaucrat, whom we shall need to apply whatever rules we may devise. And –if you can stand a moment of sheer nightmare, dear reader — imagine, just for five seconds or so, what mankind would be like, if the power to decide who was or was not to have children fell into the hands of a Senator Fulbright, a Walt Rostow, and Adam Yarmolinsky, a Jack Kennedy, or a Jack The Ripper.

For that dilemma, of course, there is an obvious solution — but, so far as I can see, only one. You, my dear reader, Dr. Pendell, and I must form a triumvirate and seize absolute power over the United States. Unfortunately, I can’t at the moment think of a way of carrying out our coup d’etat, but let’s leave such details until later. Assume that we have that power, which we, certainly, are determined to use wisely and well. What shall we do with it?

Dr. Pendell is certainly right. We must breed for brain-power: We must see to it that the most intelligent men and women mate with one another and have many children. And we can identify the intelligent by testing their “I.Q.” and by their grades in honest college courses (as distinguished from the childish or fraudulent drivel that forms so large a part of the college curriculum today).

Let us not digress from the subject by questioning the relative validity of the various tests used to determine an “intelligence quotient.” And we shall ignore the exceptions which, as every teacher knows, sometimes make the most conscientious grading misleading. Father Mendel, to whom we owe the greatest discovery ever made in biology, failed to pass the examination for a teacher’s license in that field. A.E. Houseman, one of the greatest classical scholars in the world, failed to obtain even second-class honors at Oxford, and was given a mere “pass.” But such exceptions are rare. Let us assume that we can test intelligence infallibly. Is that enough?

It is always helpful to reduce generalizations to specific examples. Percy Bysshe Shelley was one of the great English poets; Albert Einstein, although fantastically over-advertised by yellow journalism, was a great mathematician. Both were brilliant men in more than one field of intellectual activity (Shelley is said to have exhibited a considerable talent for chemistry, among other things, and Einstein is said to have done well in courses on the Classics). Both, I am sure, would have placed themselves in the very highest bracket of any intelligence test, and (if so minded) could have been graduated summa cum laude from any college curriculum that you may advise. Both were, in their judgement of social and political problems, virtually morons. Merely a deficiency of practical common sense, you say? Yes, no doubt, but both acted on the basis of that deficiency and used their intellectual powers to exert a highly pernicious influence. One need not underestimate either the beauty of Shelley’s poems or the importance of the two theories of relativity to conclude that the world would be better off, had neither man existed.

But we must go farther than that. It is odd that most of the persons who urge us to foster “superior intellect” and “genius,” whether they recommend eugenics or educational subsidies or other means, simply ignore the phenomenon of the mattoid (see Lothrop Stoddard, op. cit., pp. 102-106, and the article by Max Nordau there cited).

A mattoid is a person possessed of a mentality that is, in the strict sense of the word, unbalanced. He is a Shelley or Einstein tilted just a few more degrees. He exhibits an extremely high talent, often amounting to genius, in one kind of mental activity, such as poetry or mathematics, while the other parts of his mind are depressed to the level of imbecility or insanity. Nordau, who was an acutely observant physician, noted that such unbalanced beings are usually, if not invariably, “full of organic feelings of dislike” and tend to generalize their subjective state of resentment against the civilized world into some cleverly devised pseudo-philosophic or pseudo-aesthetic system that will erode the very foundations of civilized society. Since civilized people necessarily set a high value on intellect, but are apt to venerate “genius” uncritically and without discrimination, the mattoid’s influence can be simply deadly. Nordau, indeed, saw in the activity of mattoids the principal reason why “people [as a whole] lose the power of moral indignation, and accustom themselves to despise it as something banal, unadvanced, and unintelligent.”

Nordau’s explanation may be satisfactory so far as it goes, but moral insanity is not by any means confined to minds that show an extraordinary disproportion among the faculties that can properly be called intellectual and can be measured by such things as intelligence tests, academic records, proficiency in a profession, and outstanding research. The two young degenerates, Loev and Leopold, whose crime shocked the nation some decades ago although the more revolting details could not be reported in the Press, were reputed to be not only among the most brilliant undergraduates ever enroled in the University of Chicago, but to be almost equally proficient in every branch of study. One could cite hundreds of comparable examples.

Most monsters that become notorious have to be highly intelligent to gain and retain power. Lenin and Trotsky must have had very active minds, and the latter, at least, according to persons who knew him, was able on occasion to pass as a cultivated man. Both probably had a very high “I.Q.” All reports from China indicate that Mao Tse-tung is not only extremely astute, but even learned in the Chinese culture that he is zealously extirpating. A few Communists or crypto-Communists who have been put in prominent positions may be mere stooges, but the directors of the Conspiracy and their responsible subordinates must be persons of phenomenally high intelligence.

It is clear that there is in the human species some biological strain of either atavism or degeneracy that manifests itself in a hatred of mankind and a list for evil for its own sake. It produced the Thugs in India and the Bolsheviks in Russia (cf. Louis Zoul, Thugs and Communists, Public Opinion, Long Island City). It appears in such distinguished persons as Giles de Rais, who was second only to the king of France, and in such vulgar specimens as Fritz Haarmann, a homosexual who attracted some attention in Germany in 1924, when it was discovered that for many years he had been disposing of his boy-friends, as soon as he became tired of them, by tearing their throats open with his teeth and then reducing them to sausage, which he sold in a delicatessen. And it animates the many crypto-Communist who hold positions of power or influence in the United States.

It is probable that this appalling viciousness is transmitted by the organic mechanisms of heredity, and although no geneticist would now even speculate about what genes or lack of genes produce such biped terrors, I think it quite likely that the science of genetics, if study and research are permitted to continue, may identify the factors involved eventually — say in two or three hundred years. I know that we most urgently and desperately need to know now. But it will do no good to kick geneticists: The most infinite complexity of human heredity makes it impossible to make such determinations more quickly by the normal techniques of research. (Of course, a brilliant discovery that would transcend those methods is always possible, but we can’t count on it.)

It is quite likely that at the present rate, as eugenicists predict, civilization is going to collapse from sheer lack of brains to carry it on. But it is now collapsing faster and harder from a super-abundance of brains of the wrong kind. Granting that we can test intelligence, we must remember that at or near the top of the list, by any test that we can devise, will be a flock of diabolically ingenious degenerates. And even if we could find a way to identify and eliminate the spawn of Satan, we should still have problems.

What causes genuine “liberal intellectuals”? Many are pure Pragmatists. They have no lust for evil for its own sake; they wouldn’t betray their country or their own parents for less than fifty dollars — and not for that, if they thought they could get more by bargaining. Others are superannuated children who want to go on playing with fairies and pixies, and are ready to kick and bite when disturbed at play; but they have the combination of lachrymose sentimentality and thoughtless cruelty that one so often finds in children before they become capable of the rational morality of adults. But all of our “liberal intellectuals” were graduated from a college of some sort, and many of them, I am sure, have a fairly high “intelligence quotient” by modern tests. I do not claim or suggest that they are the result of hereditary defects; I merely point out that we do not know and have no means of finding out. We can’t be sure of anything except that our society now has as many of those dubious luxuries as it can endure. And yet we are going to encourage them to raise the intellectual level.

Come to think of it, my friends, I guess we’d better postpone our coup d’etat for a couple of centuries.

The Shape of Things to Come

For a neat antithesis to Dr. Pendell’s book and, at the same time, a very significant application of genetics, I suggest Roderick Seidenberg’s Anatomy of the Future (University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill; 175 pages). Mr. Seidenberg — I call him that because I haven’t been able to find out whether or not it should be “Dr.” — told us what our future was going to be in an earlier book, Posthistoric Man (same publisher; 256 pages), which, according to the “liberal” reviewers, made him a gigantic “philosopher of history.” In the present volume, however, he has condescended to tell us again and in fewer pages — which may make this one the better bargain.

Mr. Seidenberg, according to Mr. Seidenberg, has surveyed with his eagle eye the whole course of human history and, what is more, the whole course of biological evolution since life first appeared on this planet. That is how he knows about the “ineluctable determinism” that is going to put us in our places.

The Prophet takes his departure from the now familiar phenomenon called the “population explosion” (see American Opinion, April 1960, pp. 33 f.). He says that an increase in the number of human beings automatically increases the “complexity” of society.

Of course, we have been hearing about this “complexity” for years. I am sure that you, poor harried reader, have reflected, every time that you leap into your automobile, how much simpler life would be, if you had to worry about the health of your horses, the condition of your stable, the quality of your oats and hay, the disposition and sobriety of your coachman, the efficiency of your ostlers, and the reliability of the scavengers whom you have hired to keep clean your mews. And I know that whenever you, in Chicago, pick up the telephone to call your aunt in Miami, you remark, with may a bitter oath, how much less complex everything would be, if all that you had to do was find and hire a reliable messenger who would ride express to her house and deliver your hand-written note in a month or so — if he was not waylaid on the road, and if his horse did not break a leg or cast a shoe, and if he did not decide to pause at some bowsing-ken en route for an invigorating touch of delirium tremens. Sure, life’s gettin’ awfully complicated these days; ain’t it a fact?

Well, as we all know, life’s getting complexer every minute ’cause there are more Chinese and Congolese and Sudanese than there were a minute ago; and that means, according to Mr. Seidenberg, that we have just got to become more and more organized by the minute. And the proof of this is that, if you want to resist the ever increasing organization and socialization of society, you have to join some organization, such — I interpolate, for I need not tell you that Mr. Seidenberg would never mention anything so horrid — such as The John Birch Society. The need to join organizations to resist the organization of society proves the point, for, as is obvious, if you in 1776 had wished to resist the rule of George III, you would not have needed to join the patriots of your colony. And if, in 490 B.C., you had wished to resist the Persian invasion of Europe, you would have had no need to join, or cooperate with, your fellow Athenians who marched to Marathon. In those days of greater individualism, you, as an individual, could have stood up alone on your hind legs and stuck out your tongue — and that, presumably, would have scared Darius and his armies right into the middle of the Hellespont. But alas, no more! So, you see, History proves that the day of the individual has passed forever, and the day of Organization has come.

You must not smile, for Mr. Seidenberg is in earnest, and even if he is a bit weak in knowledge of past and present, his projection of the future has seemed cogent not merely to “liberals,” but even to thoughtful readers.

Forward to Irkalla!

Mr. Seidenberg bases his argument on inferences that he draws with apparent logic from three indisputably correct statements about the contemporary world and from a widely accepted biological theory.

1) We have all observed that we are being more and more subjected to a Welfare State, which, with Fabian patience, takes away each year some part of our power to make decisions for ourselves regarding our own lives. It is perfectly obvious that if this process continues for a few more decades (as our masters’ power to take our money to bribe and bamboozle the masses may make inevitable), we shall have lost the right to decide anything at all, and shall have become mere human livestock managed by a ruthless and inhuman bureaucracy at the orders of an even more inhuman master.

2) Our Big Brains agree with Mr. Seidenberg in believing, or pretending to believe, that “the kernel of marxism…consists in elaborating…the social message of Christ.” They assure us, therefore, that it is simply unthinkable that Americans could ever be so wicked as to fight to survive. Thus we have got to be scared or beaten into One World of universal socialism in which, as Walt Rostow, Jack Kennedy, and others now gloatingly and openly tell us, not only our nation but our race must be liquidated and dissolved in a vast and mongrel mass of pullulating bipeds.

3) The number of human beings — anatomically human, at least — is undoubtedly increasing at an appalling rate. The United States is already overpopulated for optimum life, although no critical reduction in our standard of living would be necessary for the better part of a century, if our masters permitted us to remain an independent nation. But our increase is nothing compared to the terrible multiplication of the populations of Asia and Africa, caused, for the most part, by our export to those regions of our medical knowledge, medicines, food, and money. Although we Westerners might stave off a crisis for a few decades by working harder and ever harder to support our betters and to speed up the rate at which they are breeding, it is clear that we (unless we do something unthinkable) must soon be drowned in the flood that we, like the Sorcerer’s Apprentice, started but did not know how to stop. So, even if we did not have Master Jack and his accomplices or employers to arrange for our liquidation, the sheer multiplication of the human species would produce the same result anyway.

One has but to glance at a graph of the world’s population to see that it is rapidly approaching the point at which the vast human swarm can be kept alive, even on the level of barest animal subsistence, only by the most expert management of every square inch of earth’s arable surface plus expert harvest of the very oceans themselves. In that monstrous human swarm jammed together on our planet, like a swarm of bees hanging from a limb, there can be no privacy, no individuality, no slightest deviation from the routine that must be maintained just to keep alive the maximum number that can subsist at all.

Now the theory of biological evolution, as usually stated, provides that species must adapt themselves to the conditions of survival. Men, having bred themselves into a maximum swarm, become mere units of the species, and will obviously be most efficient when they perform every action of the routine by an automatic reflex. This means that thought and even consciousness will become not only unnecessary but intolerable impediments to the efficient functioning of the human animals. Obviously, the human minds must disappear in order to permit billions of human ants to make the globe an ant-hill in which they can all live in perfect socialism.

That is what “ineluctable determinism” makes ineluctable, but Mr. Seidenberg, who is as adroit in twisting words as any editor of the New York Times, shows you how nice that will be. The Revelations of Freud have shown that we are now just bundles of instincts. Mankind will necessarily evolve to the higher state of what Mr. Seidenberg calls “pure reason.” As he explains, “pure reason” is now found only among the forms of life that are biologically superior to us because better adapted to environment. The examples which he gives are “ants, bees, and termites,” whose “essentially unchanged survival during sixty million years testifies to the perfection of their adjustment…to the conditions of life.” We must strive to become like them — nay, the “ineluctable determinism” inherent in the “population explosion” and the need for a “more advanced society” will make us, willy nilly, just like ants and termites — intellectually and spiritually, that is, for Mr. Seidenberg does not seem to entertain a hope that human beings will ever be able to crawl about on six legs.

In this perfected socialist world there can be no change and hence no history: That is why the perfect man of the near future will be, in Seidenbergian terminology, “post-historic.” Everybody will be happy, because there will be no individuals — only organisms that are part of a species and have no separate consciousness. To see how attractive the inevitable future is, you have only to reflect, dear reader, how much happier you would be, if you were an ant or a cockroach in your basement. You could operate by what Mr. Seidenberg calls “pure reason.” You could not possibly be affected by religion, art, literature, philosophy, science, capitalism, racial discrimination, or any of the other horrid things that will have to be blotted out anyway in the interests of Equality and Social Justice. You could never have a thought to trouble you. You would have no consciousness; hence you would not know that you exist, and would have no organ that could feel pain when somebody steps on you. What more could you want?

If you are so reactionary as to prefer to be conscious, even at the cost of being unhappy from time to time, you may be amused by the similarity of Mr. Seidenberg’s vision of the future to the scene described in one of the oldest of the Babylonian tablets, on which the cuneiform characters represent an oddly sibilant and staccato language: a-na maat la tari kak-ka-rifi-ti-e ila istar marat ilu sin u-zu-un-sa is- kun, etc.

“To the land whence none return, the place of darkness, Ishtar, the daughter of Sin, her ear inclined.”Then inclined the daughter of Sin her ear to the house of darkness, the domain of Irkalla; to the prison from which he that enters comes not forth; to the road whose path does not return; …to the land where filth is their bread and their food is mud. The light they behold not; in unseeingness they dwell, and are clothed, like winged things, in a garment of scales…”

Of all of mankind’s nightmarish visions of a future existence, that Babylonian conception of the dead as crawling forever, like mindless insects, in a fetid and eternal night has always seemed to me the most gruesome.

Joy is not Around the Corner

Mr. Seidenberg’s ecstatic vision of the New Jerusalem has, I am sorry to say, imposed on a least two men of scientific eminence who should have known better. They permitted themselves to be confused by the theory of biological evolution. If man evolved, over a period of 500,000 years or more, from an ape (Australopithecus) that discovered that by picking up and wielding a long bone it could increase its efficiency in killing other apes, is it not possible that our species can go on evolving and become, in another 500,000 years or less, the perfectly adjusted biped termites that Mr. Seidenberg predicts? Heavens to Betsy, I’m not going to argue that point. Granted!

And isn’t the “population explosion” a fact? Sure it is, but don’t overlook one detail — the time factor. At the present rate, the globe, sometime between 2000 and 2005 A.D. — that is to say within forty years — will be infested by 5,000,000,000 anatomically human creatures, the maximum number for which food can be supplied by even the most intensive cultivation. And then, to keep the globe inhabitable at that bare subsistence level, it will be necessary to kill every year more people than now live in the whole United States — kill them with atomic bombs or clubs, as may be more convenient.

I shall not argue about what human beings could or could not become by biological evolution in half a million years: We all know, at least, that there is going to be no biological evolution in fifty years. And, if we stop a moment to think about it, we also know that the world is not going to have a population of five billion. Not ever.

The population of the world is going to be drastically reduced before the year 2000. [See Oliver's later revision of his prediction in his article "What Hath Man Wrought? [2]" -- Editor]

The reduction could come through natural causes. It is always possible — far more possible than you imagine, if you have not investigated the relevant areas of scientific knowledge — that next week or next year may bring the onset of a new pestilence that will have a proportional mortality as great as that of the epidemic in the time of the Antonines or the Black Plaque of the Middle Ages. Alternatively, the events described in John Christopher’s brilliant novel, No Blade of Grass, could become fact, instead of fiction, at any time. And there are at least three other ways, all scientifically possible, in which the world could be partly depopulated in short order by strictly natural forces beyond our control.

But if Nature does not act, men will. When things became a bit crowded in east Asia, for example, the Huns and, at a later time, the Mongols, swept a wide swath through the world as locusts sweep through a wheat field. And wherever they felt the inspiration, they were every bit as efficient as any quantity of hydrogen bombs you may care to imagine. In the natural course of human events, we shall see in the near future wars of extermination on scale and of an intensity that your mind will, at present, refuse to contemplate. The only question will be what peoples will be among the exterminated.

If the minority of the earth’s inhabitants that is capable of creating and continuing (as distinct from aping) a high civilization is exterminated (as it now seems resolved to be), or if for some reason wars of extermination fail to solve the problem, civilization will collapse from sheer lack of brains to keep it going, and the consequent reversion to global savagery will speedily take care of the excess in numbers. In a world of savages, not only would the intricate and hated technology of our civilization be abolished, but even the simplest arts might be forgotten. (Every anthropologist knows of tribes in Polynesia and Melanesia that forgot how to make canoes, although without them it became almost impossible to obtain the fish that they regard as the most delicious food, or how to make bows and arrows, although they needed them for more effective hunting and fighting.) A world of savages in 2100 probably would not have a population more numerous than the world had in 4000 B.C.

The ordinary course of nature and human events (separately or in combination) will, in one way or another, take care of the much-touted “population explosion,” and Mr. Seidenberg knows it. You have only to read him carefully to see that all his talk about history, biological evolution, and “ineluctable determinism” is strictly for the birds — or, at least, bird-brains.

Do-It-Yourself for Socialists

Like all internationalists, Mr. Seidenberg envisages a One World of universal socialism.

Every student of history and mankind (as distinct from the ignorant theorists who prefer to chirrup while hopping from cloud to cloud in Nephelococcygia) well knows what is needed for a successful and stable socialism. And our intelligent socialists know it, too. There are two essentials, viz.: (1) a mass of undifferentiated human livestock, sufficiently intelligent to be trained to perform routine and often complicated tasks, but too stupid to take thought for their own future; and (2) a small caste of highly intelligent planners, preferably of an entirely different race, who will direct the livestock and, with the aid of overseers who need be but little more intelligent than the overseen, make sure that the livestock work hard and breed properly and do not have unsocial thoughts. The owners must be so superior to the owned that the latter will not regard themselves as of the same species. The owners must be hedged about with a quasi-divinity, and their chief, therefore, must be represented as an incarnate god.

Mr. Seidenberg knows that and tells us so. Our blissful future, he says, is assured by the emergence of “administrators [whose] special talents place them above other men.” The most important of these special talents is enough intelligence to understand that “moral restraints and compassions [and] …the attitudes and values upon which they were based have become obsolete.” On the basis of such progressive thinking, “the relatively small elite of the organizers” will manipulate the “overwhelming social mass” and guide it toward its destiny, “the mute status of unconscious organisms.”

The Chosen Few will do this by promoting “the spiritual and psychological dehumanization of man” and “a vast organizational transmutation of life.” For this glorious purpose, various techniques are available; for example, as Mr. Seidenberg tells us, “there is, plainly, more than a nihilistic meaning in the challenging ambiguities of modern art.” And, in a masterfully managed society, “the gradually inculcated feeling of helplessness…will make the mass of humanity ever more malleable and dependent upon the complex functioning of society, with its ensuing regimentation under organized patterns of behavior.” But the Supermen will use, above all, “a scientific program of genetic control to assure the complete adjustment of the human mass to its destiny” and Reactionaries and other American swine, whose “anachronistic stance” and silly efforts to avoid “the mute status of unconscious organisms” show that they “belong essentially to the past.”

As for the Supermen, who form “the nucleus of an elite of administrative functionaries and organizers ruling over the vast mass of men,” you can bet your bottom dollar (so long as Master Jack permits you to have one) that that Master Race has no intention of becoming like the bipeds that it will supervise and selectively breed for more and better mindlessness until it has attained its “historic” goal, “the settling of the human race [as distinct from its owners] into an ecologic niche of permanent and static adjustment,” which, as Mr. Seidenberg says in a moment of candor, in simply “living death.” Obviously, when this goal has been achieved, human beings, deprived of mind and even consciousness, will differ from the Master Race as much as ants and bees now differ in intelligence from human beings. Glory be!

To any attentive reader of the book, it is clear that the author, under the guise of a transparently inconsistent prophecy about a distant future, is presenting a plan for a near future that is to be created, in spite of history, in spite of nature, and in spite of mankind, by the purposeful and concerted action of a small band of “elite” conspirators, comparable to, if not identical with, the directors of the International Communist Conspiracy.

To publish such a plan in a book sold to the general public seems a fantastic indiscretion, even when one allows for the breath-taking effrontery that our Internationalists are now showing in their confidence that Americans have already been so disarmed and entrapped in the “United Nations” that, for practical purposes, it’s all over except for the butchering. When I first read these books, therefore, I was inclined to believe that the author was trying to warn us.

The Veiled Prophet of Doylestown

My inquiries, necessarily hasty and perfunctory as I write this article to meet a deadline, have elicited almost no information about Mr. Seidenberg. I do not know what region on earth was blessed with his nativity, what academic institutions bestowed the benison of their degrees upon him, or even what may be his liaison with the University of North Carolina. He is said to be an architect, but he is not listed in the 1962 edition of the American Architects’ Directory. He is said to practice that art in Doylestown, Pennsylvania, but an informant in that town reports that he is not listed in the telephone directory as an architect, although there is listed under his name, without indication of profession or occupation, a telephone which did not answer, when called on successive days.

I do not have the facilities of the FBI, so all that I really know about Mr. Seidenberg, apart from his books, is that he surfaced momentarily on February 22, 1962, in the pages of the New York Times, to emit a yip for the abolition of the House Committee on Un-American Activities. (And if you wonder why anyone should now yip against a Committee that appears to have been virtually silenced by the concerted howling of our enemies after the release of Operation Abolition, I can only tell you that, according to persons who should know, the Committee has amassed in Executive Sessions testimony which, if published, would expose some of the most powerful anti-humans in Washington.)

Mrs. Sarah Watson Emery, in her excellent book, Blood on the Old Well (prospect House, Dallas, cf. American Opinion, October, 1963, pp. 67 ff.), reports that the elusive Seidenberg, in a conversation with her, “clearly implied that he wrote the books in order to bring about the ghastly future” that he “so confidently predicts.” If Mrs. Emery is right, Mr. Seidenberg’s books are inspirational literature for the Master Race of “administrators,” who are now taking over the whole world. They can own and operate the world forever in perfect Peace, if, by a scientific application of genetics, they reduce human beings to the status of mindless insects.

Is One World Feasible?

You, my patient reader, may be a member of the Radical Right and hence unenthusiastic about the happiness that is being planned for you. If so, I confess that I, whom a learned colleague recently described as a “filthy Fascist swine,” share your misgivings. But let us here consider the Seidenbergian ideal exclusively as a problem in genetics. Is it possible?

Probably not, by the hit-and-miss methods that the Conspiracy has thus far employed.

As Mr. Seidenberg carefully points out, “Russia [under Lenin, Stalin, and Khrushchev] and America [under Roosevelt, Eisenhower, and Kennedy] are basically akin by reason of the dominance of their organizational trends,” but — hélas! — even today “the collectivization of society is only in its incipient stages in Russia.” And the reason is obvious. Although Ulyanov (alias Lenin) and Bronstein (alias Trotsky) butchered millions of reactionary Russians who wanted to be individual human beings, and although Dzhugashvili (alias Stalin) butchered millions more, and although Saint Nick (formerly Khrushchev) shot, hacked to pieces, or starved seven million in the Ukraine alone when he as just a local manager for the Communist Conspiracy, the nasty Russians are still unregenerate. Although the world’s vermin have had absolute control of Russia for almost half a century and have certainly worked hard to exterminate every Russian who had in himself a spark of self-respect, human decency, or even the will to live, observers agree that the recent failure of crops would have precipitated a crisis and possibly even a revolt of blind desperation, if Master Jack had not ordered his American cattle to provide the wheat that Comrade Nick needed to keep his own restive cattle fairly quiet. And it is quite likely that if the Conspiracy were to lose control of the United States and so be forced to retreat somewhere in the world, the Russian people would revolt anyway. The most systematic butchery has not destroyed the genetic transmission of human instincts. And it is unlikely to do so for centuries, at least.

Americans are apt to be even more refractory, and I am sure that One Worlders, now that they think their final victory almost achieved, must be giving thought to the problem of what to do with them. (And I need not remind you that advanced minds are not troubled by “moral restraints” and the other “attitudes and values.”) The American kulaks were useful and even necessary to fight wars “to make the world safe for democracy” and to finance with “foreign aid” the Communist conquest of the world, but when that goal has been achieved, they are likely to be a real nuisance.

There are rumors, for example, that Master Jack is planning to send the U.S. Army — which, as purged by Yarmolinsky and his stooges, will presumably be a docile instrument for the abolition of the nation it was established to defend — to seal off one area of the country after another, drive the white swine from their homes, and search them to confiscate such firearms or other weapons as they may have in their possession. It may be necessary to beat a few hundred of the white pigs so that their squealing will teach the other livestock to obey their owner, but, according to the rumors, nothing more than that is contemplated. But even if the operation is successful, one can foresee endless trouble. Human instincts are more or less fixed by heredity.

It is no wonder, therefore, that Mr. Seidenberg foresees “long-range genetic manipulation designed not only to improve the human stock according to the social dictates of [the proprietors of] a collectivized humanity, but above all to eliminate, in one manner or another, any traces of anti-social deviation.”

Those are, doubtless, sound general principles, but what, specifically, is to be done with the Americans when the “United Nations” takes them over? One could, as Mr. Seidenberg delicately hints in one passage, just castrate all the males. (If this idea seems shocking to you, remember that that’s just your “anachronistic stance.”) Or one could adopt the policy which the Soviet, according to a report that was leaked “from U.N. official sources” and reported in the now defunct Northlander (September, 1958), uses in Lithuania, where all potentially troublesome males were rounded up and shipped to Siberia and then replaced in their own homes by public-spirited Mongolian males eager to improve the quality of the Lithuanian population. A Baluba or a Bakongo thus installed in every American home would not only effectively end “discrimination” and promote the “World Unity” desiderated by Internationalists, but would also — according to a “scientific” study made by a Professor Of Sociology in a tax-supported American university and reported both in his class-room lectures and in his broadcasts over a radio-station entirely owned by that university — fulfill the secret yearnings of all American womanhood.

This may seem a perfect solution (if you have a “One World” viewpoint), but it has, I fear, its drawbacks. Balubas and such are just fine for exterminating white men in Africa and creating chaos under direction from Washington and Moscow, but I suspect that anyone who tries to regiment them to do work is in for a powerful lot of trouble. After they have served their purpose, it will be necessary to exterminate them, too. And the Masters, after they have blotted out the civilization they hate, are going to need workers, not cannibals and other savages, if, in keeping with the Seidenbergian vision, they are to rule the world forever.

Now Americans and Europeans are excellent workers. What is needed, obviously, is not to destroy them but to convert them, as Mr. Seidenberg predicts, into true zombies, that is to say, creatures that have no will or personality of their own and therefore do whatever they are told. But that transformation, so far as I can learn from geneticists whom I have consulted, is genetically impossible by any process of selective breeding within any reasonable length of time — say a thousand years or less. This, I am sure, our author realizes, for after admitting that “the art of brainwashing and, even more so, the science of controlling society by pharmaceutical manipulation, are in their infancy,” he places his hope for the future in “the ever increasing techniques and the ever more refined arts of mental coercion.” Presumably, the human mind and will can be destroyed by drugs, or perhaps by an improved technique of lobotomy, to produce the kind of “mental health” requisite in the zombies who, like mindless insects, are to work to support the Master Race of the future. But this is not genetics, and the qualities thus induced in individuals cannot be transmitted genetically. The Masters, therefore, will be put to the trouble of operating on each generation of biped insects as it is produced — and, what is even worse, there is some reason to doubt that the zombies would or could reproduce themselves.

So, you see, the New Dispensation of which Internationalists dream is by no means assured, either historically or biologically. For that matter, it is even possible that enough Americans may object in time to frustrate the “determinism” that only their ignorance, apathy, or cowardice could make “ineluctable.” But I cannot speculate about that possibility here. I have sought only to show you, as dispassionately as possible, what kind of thoughts very advanced minds are thinking about you these days.

Source: http://www.revilo-oliver.com/news/1963/12/history-and-biology/ [3]

One of the only valid points made by the critics of Bell Curve

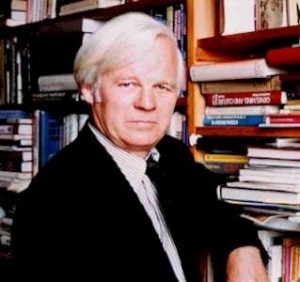

One of the only valid points made by the critics of Bell Curve was that if the science was accepted, then eugenics, which Hernstein and Murray refused to endorse, becomes the rational solution to society’s ills. Steven Pinker, the next major public thinker associated with the hereditarian position, likewise refused to follow his own logic far enough. One scholar who doesn’t flinch is psychologist Richard Lynn. Eugenics is not only right, but we have a duty to increase the frequency of genes for positive traits and reduce the frequency of genes for negative traits. Once you determine that something is a genetic problem it cries out for a genetic solution. Eugenics: A Reassessment looks at the history of eugenics, the ethical case for it and its future. Here Lynn goes beyond his role as a psychologist and gives us his own theory of the coming end of history.

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

En effet, cette étude démontre qu'une région cérébrale et des neurones, impliqués dans un sens précis peuvent aussi interpréter d'autres types d'informations sensorielles. « Les nerfs ont répondu en même temps au toucher et à la lumière infrarouge. Ceci montre que le cerveau humain peut acquérir de nouvelles capacités qui n'ont jamais été expérimentées sur l'animal avant cela », a ajouté le scientifique. En théorie, une personne aveugle pour cause de dommage au niveau du cortex visuel pourrait recouvrer la vue en utilisant un implant sur une autre partie de son cerveau. Tout comme pourrait le faire une personne devenue sourde en raison de dommages au niveau du cortex auditif. « Ceci suggère que, dans le futur, il serait possible d'utiliser des dispositifs de type prothèses pour restaurer des modalités sensorielles qui ont été perdues, telles que la vision, en utilisant une partie cérébrale différente », a confirmé le

En effet, cette étude démontre qu'une région cérébrale et des neurones, impliqués dans un sens précis peuvent aussi interpréter d'autres types d'informations sensorielles. « Les nerfs ont répondu en même temps au toucher et à la lumière infrarouge. Ceci montre que le cerveau humain peut acquérir de nouvelles capacités qui n'ont jamais été expérimentées sur l'animal avant cela », a ajouté le scientifique. En théorie, une personne aveugle pour cause de dommage au niveau du cortex visuel pourrait recouvrer la vue en utilisant un implant sur une autre partie de son cerveau. Tout comme pourrait le faire une personne devenue sourde en raison de dommages au niveau du cortex auditif. « Ceci suggère que, dans le futur, il serait possible d'utiliser des dispositifs de type prothèses pour restaurer des modalités sensorielles qui ont été perdues, telles que la vision, en utilisant une partie cérébrale différente », a confirmé le

History is the record of what men do. Scientific discoveries and technological applications of them are often events of historical importance, but do not affect our understanding of the historical process since they shed no light on the behavior of men in civilized societies.

History is the record of what men do. Scientific discoveries and technological applications of them are often events of historical importance, but do not affect our understanding of the historical process since they shed no light on the behavior of men in civilized societies.

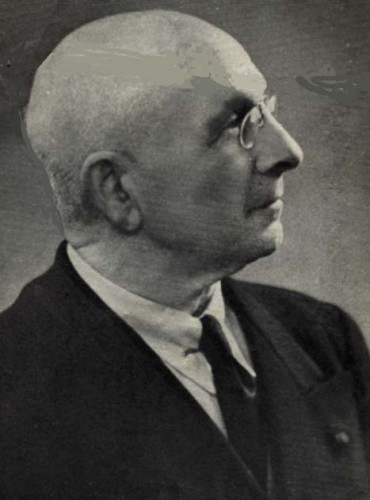

.jpg)

Alexis Carrel, an observer of the material universe, was one among a unique lineage of scientists who sought out solutions to what they considered were the primary problems confronting the modern world. For Carrel the material progress that was jumping by leaps and bounds from the 19th century across into his century was causing moral, physical and spiritual degeneration. While scientists, then as now overspecialized, and devoid of a broad perspective, were making new discoveries in the physical and social sciences, problems of degeneration and its ultimate consequences were not being sufficiently addressed in a holistic manner.

Alexis Carrel, an observer of the material universe, was one among a unique lineage of scientists who sought out solutions to what they considered were the primary problems confronting the modern world. For Carrel the material progress that was jumping by leaps and bounds from the 19th century across into his century was causing moral, physical and spiritual degeneration. While scientists, then as now overspecialized, and devoid of a broad perspective, were making new discoveries in the physical and social sciences, problems of degeneration and its ultimate consequences were not being sufficiently addressed in a holistic manner. While Carrel has been deemed since 1944 to be a “fascist,” a “collaborator,” and a “Nazi,” his championing of the individual rather than the mass does not sit well with stereotypical images. Like others skeptical of democracy and equality, he opposed the leveling tendencies of the modern era, be they in the form of capitalism or Marxism, both of which had accepted the same formulation of man and society, Carrel in Reflections on Life calling the Liberal bourgeois the elder brother of the Bolshevist.

While Carrel has been deemed since 1944 to be a “fascist,” a “collaborator,” and a “Nazi,” his championing of the individual rather than the mass does not sit well with stereotypical images. Like others skeptical of democracy and equality, he opposed the leveling tendencies of the modern era, be they in the form of capitalism or Marxism, both of which had accepted the same formulation of man and society, Carrel in Reflections on Life calling the Liberal bourgeois the elder brother of the Bolshevist. Carrel proceeds with the first chapter to trace the dissolution of traditional communal bonds with the ancestral traditions being undermined from the time of the Renaissance, through to the Reformation, and the revolutions of France and America, enthroning of rationalism and heralding the rise of liberalism and Marxism:

Carrel proceeds with the first chapter to trace the dissolution of traditional communal bonds with the ancestral traditions being undermined from the time of the Renaissance, through to the Reformation, and the revolutions of France and America, enthroning of rationalism and heralding the rise of liberalism and Marxism:

Die Pentagon-Behörde für fortschrittliche Verteidigungsforschung DARPA (Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency) stößt oftmals in utopisch wirkende Dimensionen vor, um zu zeigen, was prinzipiell machbar ist. Und genau damit rücken diese Utopien bereits wieder in greifbare Nähe. Die militärische Forschergilde findet zunehmend Geschmack an ganz besonderen Rezepten, wie sie derzeit in ganz besonderen »Kochkursen« ersonnen werden. Denn neue DNA-Cocktails, künstliche Ursüppchen und mehrgängige Biosynthese-Menüs erfreuen sich bei den militärischen Gen-Gourmets wachsender Beliebtheit.

Die Pentagon-Behörde für fortschrittliche Verteidigungsforschung DARPA (Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency) stößt oftmals in utopisch wirkende Dimensionen vor, um zu zeigen, was prinzipiell machbar ist. Und genau damit rücken diese Utopien bereits wieder in greifbare Nähe. Die militärische Forschergilde findet zunehmend Geschmack an ganz besonderen Rezepten, wie sie derzeit in ganz besonderen »Kochkursen« ersonnen werden. Denn neue DNA-Cocktails, künstliche Ursüppchen und mehrgängige Biosynthese-Menüs erfreuen sich bei den militärischen Gen-Gourmets wachsender Beliebtheit. Archives de SYNERGIES EUROPEENNES - 1988

Archives de SYNERGIES EUROPEENNES - 1988