La notion d’identité, qui a massivement investi le champ des sciences sociales depuis une quarantaine d’années, apparaît aujourd’hui comme une notion incontournable, tant au niveau individuel que collectif, dans l’analyse des conflits, tensions, crises, dans un contexte de changements sociétaux rapides et déstabilisateurs et de remise en cause des « grands récits » caractéristiques de la Modernité.

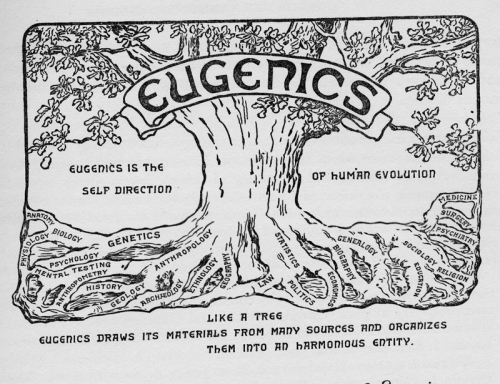

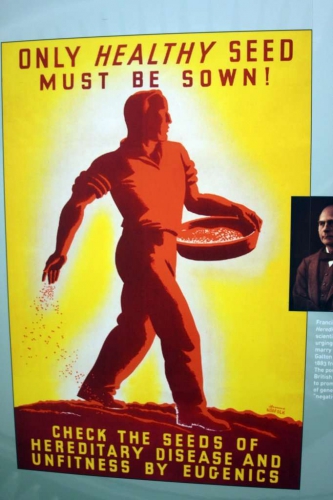

Ainsi, ce recours croissant à la notion d’identité apparaît en grande partie lié à la réhabilitation de la notion de sujet qui, au sortir de la Seconde Guerre mondiale, avait été occultée, du fait de son caractère prétendument illusoire, par plusieurs courants de pensée alors dominants (marxisme, behaviorisme, structuralisme, etc.) [1]. Ces courants de pensée issus des « grands récits » qui se sont constitués au XIXème siècle comme autant de religions séculières (libéralisme, scientisme, marxisme…) postulaient, conformément à l’idéologie du Progrès, que l’avenir serait nécessairement meilleur que le présent et affirmaient dans le même temps la possibilité d’un salut dans l’ici-bas [2]. Les évènements tragiques du XXème siècle ont cruellement infirmé la vision optimiste, progressiste du devenir du monde portée par ces religions séculières.

Omniprésente dans les débats contemporains, la notion d’identité apparaît, toutefois, difficile à cerner dans la mesure où elle résulte de constructions historiques particulières et comporte de multiples facettes. Dans une approche très générale, comme le relève Samuel Huntington, l’identité est ce qui nous distingue des autres [3]. Plus spécifiquement, le philosophe Charles Taylor l’envisage comme un cadre, un horizon au sein duquel l’individu est en mesure de prendre des engagements, une posture morale, souvent en référence à une communauté [4].

Sans doute ce cadre, pour partie hérité, pour partie choisi, n’est-il pas immuable, intemporel mais au contraire évolutif : l’identité n’est pas une essence ; elle se construit historiquement « dans le dialogue ou la confrontation avec l’Autre » [5]. De plus, la narration apparaît comme le principal mode de construction de cette identité évolutive, ainsi que l’a montré Paul Ricoeur en introduisant la distinction entre « l’identité ipse » et « l’identité idem » : « A la différence de l’identité abstraite du Même, l’identité narrative, constitutive de l’ipséité, peut inclure le changement, la mutabilité, dans la cohésion d’une vie. » [6] Ce caractère narratif de l’identité vaut aussi bien au plan individuel que s’agissant de l’identité collective [7].

Les questionnements, les débats qui surgissent actuellement dans les pays européens [8] et aux Etats-Unis [9] sur l’identité sont le plus souvent interprétés, à raison, comme un symptôme de crise d’une société en pleine mutation. L’affirmation, la revendication d’une identité est alors présentée selon les cas, soit comme une menace supplémentaire et une aggravation de la crise, soit comme une réponse légitime à cette crise, voire comme une solution (c’est notamment la question de la reconnaissance symbolique ou même juridique de l’identité des minorités ethniques, sexuelles etc.). Cette crise, vue sous l’angle de l’identité peut être appréhendée à un double niveau, individuel et collectif.

Au plan individuel, le questionnement identitaire révèle un sentiment de perte de sens au sein des sociétés modernes. Dans son ouvrage Les sources du moi. La formation de l’identité moderne, Charles Taylor, en faisant la généalogie de l’identité moderne, a montré que celle-ci s’est notamment construite sur une conception instrumentale du monde, c’est-à-dire un monde vu comme un simple mécanisme que la raison doit s’attacher à objectiver et à contrôler. Or, cette vision instrumentale du monde, héritée du cartésianisme, et qui a connu son plein épanouissement au XXème siècle, s’est révélée un puissant facteur de désymbolisation [10], synonyme de perte de sens. Ainsi, cette crise, interprétée à travers le prisme de l’identité, apparaît dans une large mesure comme une crise de la modernité, une crise affectant l’homme faustien dont parlait Spengler dans Le Déclin de l’Occident, c’est-à-dire « un individu caractérisé par une insatisfaction devant tout ce qui est fini, terminé », un homme qui « ne croit plus qu’il peut savoir ce qui est bien et mal, ce qui est juste et injuste. » [11]

Au plan individuel, le questionnement identitaire révèle un sentiment de perte de sens au sein des sociétés modernes. Dans son ouvrage Les sources du moi. La formation de l’identité moderne, Charles Taylor, en faisant la généalogie de l’identité moderne, a montré que celle-ci s’est notamment construite sur une conception instrumentale du monde, c’est-à-dire un monde vu comme un simple mécanisme que la raison doit s’attacher à objectiver et à contrôler. Or, cette vision instrumentale du monde, héritée du cartésianisme, et qui a connu son plein épanouissement au XXème siècle, s’est révélée un puissant facteur de désymbolisation [10], synonyme de perte de sens. Ainsi, cette crise, interprétée à travers le prisme de l’identité, apparaît dans une large mesure comme une crise de la modernité, une crise affectant l’homme faustien dont parlait Spengler dans Le Déclin de l’Occident, c’est-à-dire « un individu caractérisé par une insatisfaction devant tout ce qui est fini, terminé », un homme qui « ne croit plus qu’il peut savoir ce qui est bien et mal, ce qui est juste et injuste. » [11]

Au plan collectif, de puissants mouvements d’homogénéisation, dont la mondialisation constitue l’une des manifestations les plus notables, contribuent à dissoudre les identités, en particulier nationales [12]. Ces mouvements d’homogénéisation apparaissent comme le produit d’une idéologie égalitariste, ce qu’Alain de Benoist appelle « l’idéologie du Même » [13], qui tend à nier les différences, qu’elles soient d’ailleurs individuelles ou collectives, en les considérant comme insignifiantes. Ces deux dimensions, individuelles et collectives, sont liées : le processus d’homogénéisation tendant à faire disparaître les identités collectives contribue par là même au sentiment de perte de sens ressenti par les individus [14].

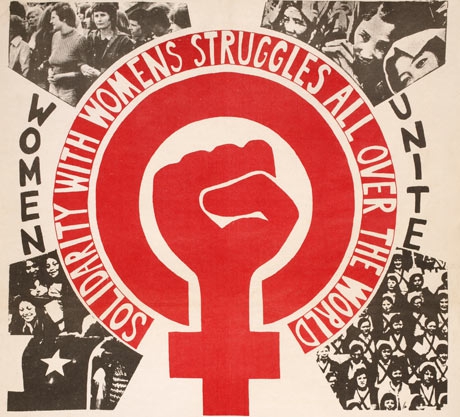

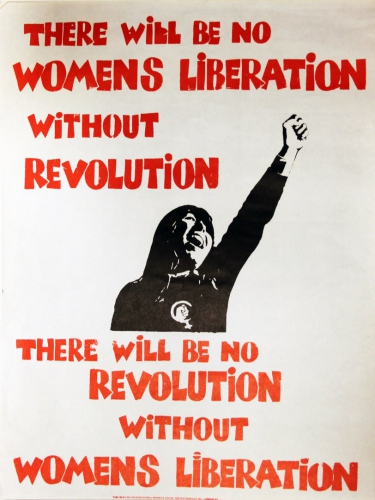

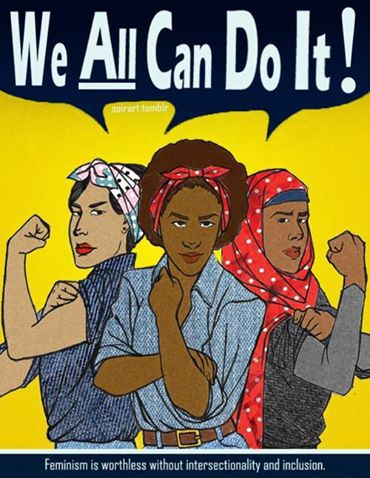

C’est donc à l’aune de cette crise, considérée dans ses deux dimensions, qu’il convient d’apprécier les réactions, les questionnements et les recompositions identitaires qui se manifestent aujourd’hui. Ainsi, on assiste, dans la période actuelle, à des réveils identitaires multiformes : réveil des régionalismes contre l’Etat-Nation, par exemple au Royaume-Uni ou encore en Espagne, réveil des identités nationales face à la mondialisation avec la montée des partis qualifiés de populistes, émergence d’un « tribalisme » qui serait le signe d’un déclin de l’individualisme et de la raison instrumentale et utilitaire [15], affirmation des identités religieuses, ethniques ou encore des identités liées au genre [16].

Dans ce contexte, on peut se demander comment susciter, accompagner, orienter les réveils identitaires des peuples européens en vue de reconstituer un cadre, un horizon commun, pour reprendre la terminologie de Charles Taylor, qui soit en mesure de préserver leur liberté. Ainsi, il parait nécessaire d’identifier non seulement les modèles pertinents qui pourraient inspirer la redéfinition d’un tel cadre mais également les leviers d’action métapolitiques permettant la mise en œuvre concrète d’une telle reconstruction.

Printemps identitaires : identités glorifiées, victimaires ou menacées

Schématiquement, on peut distinguer au moins trois sources auxquelles puisent les mouvements identitaires en plein développement aujourd’hui. Ainsi, les réveils identitaires que l’on observe peuvent se fonder principalement sur une identité glorifiée, sur une identité victimaire ou encore sur une identité menacée.

Tout d’abord, certains réveils identitaires se fondent sur la mise en récit d’une identité glorifiée qui prend appui sur la puissance actuelle et les succès d’une collectivité vécus comme des motifs de fierté pour les membres de cette collectivité renforçant par là même leur sentiment d’appartenance au groupe. En se limitant au cadre national, il s’agit là d’un ressort exploité par D. Trump aux Etats-Unis et que traduit son slogan de campagne « Make America Great Again ». C’est également à ce type de réveil identitaire que l’on assiste en Russie : après l’effondrement du communisme et les années noires de la période Eltsine (1991-1998), la politique de V. Poutine a consisté à restaurer la puissance de la Russie en vue d’en faire un acteur majeur au sein d’un monde multipolaire, non seulement en s’attachant à renforcer sa puissance militaire et énergétique, mais aussi en réaffirmant les valeurs traditionnelles de l’identité russe : « le peuple, la patrie, la religion orthodoxe et le souvenir des gloires impériales d’antan » [17]. Ainsi, la Russie s’est en quelque sorte érigée en contre-modèle de la postmodernité décadente d’un Occident dénué d’optimisme et d’énergie. Si bien que l’institut Levada estimait en 2009 que 80% des Russes considéraient leur pays comme une grande puissance contre seulement 30% huit ans auparavant [18].

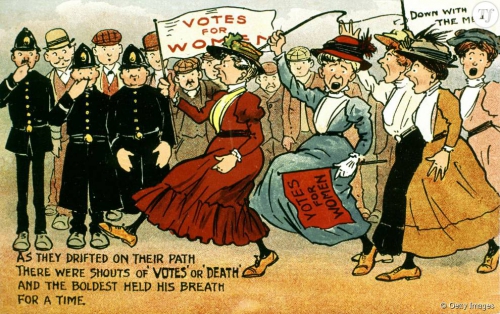

En second lieu, on observe le développement de mouvements identitaires, notamment à caractère ethnique, reposant sur la mise en récit d’un passé interprété comme humiliant et qui justifierait en tant que tel une reconnaissance non seulement symbolique mais aussi juridique. Il s’agit là de l’exploitation (non exempte, bien souvent, d’instrumentalisation) d’une mémoire, d’un imaginaire victimaire visant à réclamer des compensations aux supposés coupables (ou à leurs descendants), et aboutissant à nourrir un sentiment de revanche voire de haine et ainsi à fortifier une identité collective autour d’un ennemi commun. Aux Etats-Unis des mouvements de ce type invoquent la mémoire de l’esclavage pour dénoncer le traitement supposément spécifique dont feraient l’objet, de la part de la police, les membres de la communauté noire (cf. le mouvement Black Lives Matter). C’est aussi la voie suivie par une partie des populations immigrées issues des pays anciennement colonisés à l’encontre des ex-pays colonisateurs comme la France. Ces revendications identitaires trouvent un écho favorable, notamment parmi les élites politiques, économiques, judiciaires et médiatiques qui conçoivent l’affirmation identitaire des minorités comme une réaction légitime face à une culture occidentale européocentriste considérée comme un système de domination aliénant, oppressant par nature pour ces minorités. Ainsi, le traitement médiatique des faits de délinquance tend à occulter délibérément le nom des délinquants quand ils sont d’origine étrangère avec en arrière-fond l’idée que ces délinquants sont et restent par essence des victimes qu’il convient de protéger [19]. Les politiques de quota et de discrimination positive dans l’accès à l’emploi ou à l’université s’inscrivent également dans ce schéma de pensée. Comme le relève Christopher Lasch, on est passé d’une demande d’égalité et d’abolition des discriminations fondées sur la race (mouvement des droits civiques aux Etats-Unis dans les années 1960) à la revendication et à l’instauration d’un traitement de faveur au profit des minorités raciales au motif que ces minorités, éternelles victimes du racisme des Blancs, auraient par nature un droit à réparation [20]. Ce type de mesure qui avalise les revendications identitaires de nature victimaire tend à nourrir les conflits ethniques au sein de la société [21].

En second lieu, on observe le développement de mouvements identitaires, notamment à caractère ethnique, reposant sur la mise en récit d’un passé interprété comme humiliant et qui justifierait en tant que tel une reconnaissance non seulement symbolique mais aussi juridique. Il s’agit là de l’exploitation (non exempte, bien souvent, d’instrumentalisation) d’une mémoire, d’un imaginaire victimaire visant à réclamer des compensations aux supposés coupables (ou à leurs descendants), et aboutissant à nourrir un sentiment de revanche voire de haine et ainsi à fortifier une identité collective autour d’un ennemi commun. Aux Etats-Unis des mouvements de ce type invoquent la mémoire de l’esclavage pour dénoncer le traitement supposément spécifique dont feraient l’objet, de la part de la police, les membres de la communauté noire (cf. le mouvement Black Lives Matter). C’est aussi la voie suivie par une partie des populations immigrées issues des pays anciennement colonisés à l’encontre des ex-pays colonisateurs comme la France. Ces revendications identitaires trouvent un écho favorable, notamment parmi les élites politiques, économiques, judiciaires et médiatiques qui conçoivent l’affirmation identitaire des minorités comme une réaction légitime face à une culture occidentale européocentriste considérée comme un système de domination aliénant, oppressant par nature pour ces minorités. Ainsi, le traitement médiatique des faits de délinquance tend à occulter délibérément le nom des délinquants quand ils sont d’origine étrangère avec en arrière-fond l’idée que ces délinquants sont et restent par essence des victimes qu’il convient de protéger [19]. Les politiques de quota et de discrimination positive dans l’accès à l’emploi ou à l’université s’inscrivent également dans ce schéma de pensée. Comme le relève Christopher Lasch, on est passé d’une demande d’égalité et d’abolition des discriminations fondées sur la race (mouvement des droits civiques aux Etats-Unis dans les années 1960) à la revendication et à l’instauration d’un traitement de faveur au profit des minorités raciales au motif que ces minorités, éternelles victimes du racisme des Blancs, auraient par nature un droit à réparation [20]. Ce type de mesure qui avalise les revendications identitaires de nature victimaire tend à nourrir les conflits ethniques au sein de la société [21].

Enfin, certains réveils identitaires trouvent leur source dans un futur jugé menaçant. Le terrorisme islamiste a ainsi généré un regain du patriotisme dans les pays touchés par le phénomène, notamment aux Etats-Unis depuis 2001. Selon S. Huntington, le 11 septembre a symbolisé la fin du XXème siècle, siècle des conflits idéologiques, et le début d’une nouvelle ère dans laquelle les peuples se définissent eux-mêmes d’abord en termes de culture et de religion [22]. Ainsi, selon cet auteur, les ennemis potentiels de l’Amérique aujourd’hui sont l’islamisme et le nationalisme chinois non idéologique. En Europe, la multiplication des attentats islamistes ces dernières années réveille également les consciences d’autant plus que l’identité européenne s’est forgée depuis des siècles en opposition notamment aux conquêtes musulmanes [23]. Pour J. Le Goff « une identité collective se bâtissant en général autant sur les oppositions à l’autre que sur des convergences internes, la menace turque va être un des ciments de l’Europe » [24].

A cet égard, dans son ouvrage Les vertiges de la guerre – Byron, les philhellènes et le mirage grec, Hervé Mazurel retrace une des étapes importantes de la prise de conscience d’une identité européenne à travers le combat civilisationnel du mouvement philhellène dans les années 1820 en vue de libérer la Grèce, matrice de la civilisation européenne, de l’envahisseur ottoman, jugé coupable des pires atrocités (massacres, viols), immortalisées par la Scène des massacres de Scio de Delacroix et dont témoigne également le recueil de poèmes Les Orientales de Victor Hugo. Or tout cet arrière-fond historique ré-émerge aujourd’hui dans les consciences non seulement au moment des attentats terroristes mais également à l’occasion des évènements dramatiques liés aux mouvements migratoires (viols de Cologne…).

A cet égard, dans son ouvrage Les vertiges de la guerre – Byron, les philhellènes et le mirage grec, Hervé Mazurel retrace une des étapes importantes de la prise de conscience d’une identité européenne à travers le combat civilisationnel du mouvement philhellène dans les années 1820 en vue de libérer la Grèce, matrice de la civilisation européenne, de l’envahisseur ottoman, jugé coupable des pires atrocités (massacres, viols), immortalisées par la Scène des massacres de Scio de Delacroix et dont témoigne également le recueil de poèmes Les Orientales de Victor Hugo. Or tout cet arrière-fond historique ré-émerge aujourd’hui dans les consciences non seulement au moment des attentats terroristes mais également à l’occasion des évènements dramatiques liés aux mouvements migratoires (viols de Cologne…).

Au-delà du terrorisme islamique, d’autres menaces sans doute plus diffuses permettent d’expliquer les réveils identitaires qui ont cours aujourd’hui. Ainsi la situation de profonds bouleversements (mutations technologiques, phénomènes migratoires…) que connaissent nos sociétés génère des incertitudes croissantes et laissent entrevoir des changements majeurs dans nos modes de vie (travail, éducation, sécurité…) avec le sentiment de plus en plus largement partagé, à tort ou à raison, que ces mutations touchent d’abord les plus fragiles et toucheront à court ou moyen terme une part croissante de la population alors même qu’une petite élite au pouvoir, notamment politique et économique, reste protégée. Or, ces bouleversements en cours dans les modes de vie sont envisagés de manière négative et angoissée par de larges pans de la population des pays développés qui semblent aspirer pour le moins au statu quo et ressentent même une nostalgie vis-à-vis de modes de relations sociales qui avaient cours il y a encore quelques dizaines d’années [25]. L’une des causes profondes de ce qui est vécu aujourd’hui comme un véritable délitement social en voie d’accélération rapide semble résider, au moins en partie, dans un modèle libéral dominant qui s’est progressivement radicalisé depuis une trentaine d’années.

Dénoncer les totems du libéralisme

Par nature, le libéralisme, en tant qu’il est fondé sur une conception individualiste de l’homme, contribue à diluer sinon à détruire les identités collectives traditionnelles [26]. Les justifications qui sont invoquées pour légitimer l’approfondissement du modèle libéral et son application généralisée à tous les domaines de la vie en société sont principalement de deux ordres.

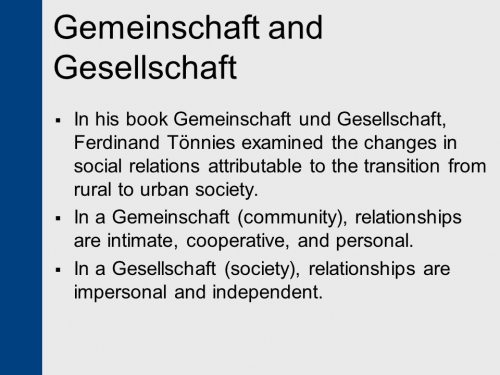

D’une part, le projet libéral est une promesse de bonheur individuel en ce qu’il se propose de libérer l’individu de tous les carcans traditionnels considérés comme attentatoires à son autonomie et à son épanouissement personnel en substituant à tous les modes de relations sociales traditionnels des relations de type contractuel régies par le marché. En bref, il s’agit de substituer des identités « choisies » aux identités héritées. Ainsi, le capitalisme marchand puis industriel et enfin financier tel qu’il s’est développé dans l’histoire et qui n’est autre que la déclinaison au plan strictement économique de l’idéologie libérale fournit de multiples illustrations de ce pouvoir censément libérateur. Boltanski et Chiapello ont notamment montré que le développement du salariat qui est allé de pair avec le développement du capitalisme industriel au XIXème siècle a constitué une forme d’émancipation, principalement de type géographique, à l’égard des communautés locales traditionnelles [27].

Plus généralement, en effet, les économistes classiques puis néo-classiques se sont attachés à montrer, depuis le XVIIIème siècle, que le marché constituait le mode optimal d’allocation des ressources en vue de favoriser le progrès global de l’humanité sur un plan matériel. En pratique, cette conception, qui dilue les identités collectives traditionnelles fondées sur des liens non marchands, tend à réduire l’individu principalement au rôle de producteur-consommateur en lui fournissant des identités de substitution [28].

D’autre part, dès l’origine, le modèle libéral, en tant qu’il a pour effet de diluer les identités collectives, a été vu comme un facteur d’apaisement et de résolution des conflits [29], notamment en référence à cette forme particulière de guerres civiles que constituaient les guerres de religion qui avaient ensanglanté l’Europe aux XVIème et XVIIèmesiècles. C’est la théorie bien connue du « doux commerce » énoncée par Adam Smith au XVIIIème siècle [30]. A ce titre, le libéralisme, qui constitue le cadre idéologique de la construction européenne telle qu’elle a été pensée depuis la fin de la Deuxième Guerre mondiale, vise à dissoudre les identités nationales au motif qu’elles seraient les principaux vecteurs des conflits mondiaux [31].

Or, la théorie du « doux commerce » chère aux penseurs libéraux des Lumières apparait, dans une large mesure, comme un mythe. En réalité, les intérêts commerciaux se sont révélés être de puissants facteurs d’exacerbation des conflits. Comme le relève Pascal Gauchon (photo), « pour que règne la paix, il fallait imposer le commerce par la guerre » [32]. De plus, la tendance à l’uniformisation du monde par la mondialisation libérale entraine, aujourd’hui, en retour, des mouvements de fragmentation, sources de nouveaux conflits (montée des fondamentalismes religieux notamment) [33]. Pascal Gauchon observe qu’« alors que les frontières nationales s’abaissent, les frontières intérieures se multiplient : les communautés fermées se multiplient, les immeubles s’abritent derrière des barrières digitales et le code postal définit l’identité (…) » [34]. Apparaissent donc de plus en plus clairement tous les ferments de la guerre civile à mesure que les sociétés s’hétérogénéisent sous l’effet de l’immigration de masse qu’encourage la mondialisation libérale, ce que Pascal Gauchon appelle « les guerres de la mondialisation ». Quant au projet de libération de l’individu, il apparait lui aussi très largement comme une utopie, tant il est vrai que les politiques libérales, notamment au plan économique, se sont traduites par de nouvelles aliénations ainsi que l’ont montré les travaux de Jean Baudrillard sur la société de consommation. Aliénation par la consommation via la publicité qui est infligée à l’individu-consommateur conçu comme « un système pavlovien standard, modélisable par quelques lois comportementales et cognitives simples, manipulable et orientable par les professionnels du marketing » [35]. Aliénation au travail que subit le travailleur moderne « occupant des emplois provisoires, dépersonnalisés, délocalisés en fonction des besoins de l’économie » [36].

Or, la théorie du « doux commerce » chère aux penseurs libéraux des Lumières apparait, dans une large mesure, comme un mythe. En réalité, les intérêts commerciaux se sont révélés être de puissants facteurs d’exacerbation des conflits. Comme le relève Pascal Gauchon (photo), « pour que règne la paix, il fallait imposer le commerce par la guerre » [32]. De plus, la tendance à l’uniformisation du monde par la mondialisation libérale entraine, aujourd’hui, en retour, des mouvements de fragmentation, sources de nouveaux conflits (montée des fondamentalismes religieux notamment) [33]. Pascal Gauchon observe qu’« alors que les frontières nationales s’abaissent, les frontières intérieures se multiplient : les communautés fermées se multiplient, les immeubles s’abritent derrière des barrières digitales et le code postal définit l’identité (…) » [34]. Apparaissent donc de plus en plus clairement tous les ferments de la guerre civile à mesure que les sociétés s’hétérogénéisent sous l’effet de l’immigration de masse qu’encourage la mondialisation libérale, ce que Pascal Gauchon appelle « les guerres de la mondialisation ». Quant au projet de libération de l’individu, il apparait lui aussi très largement comme une utopie, tant il est vrai que les politiques libérales, notamment au plan économique, se sont traduites par de nouvelles aliénations ainsi que l’ont montré les travaux de Jean Baudrillard sur la société de consommation. Aliénation par la consommation via la publicité qui est infligée à l’individu-consommateur conçu comme « un système pavlovien standard, modélisable par quelques lois comportementales et cognitives simples, manipulable et orientable par les professionnels du marketing » [35]. Aliénation au travail que subit le travailleur moderne « occupant des emplois provisoires, dépersonnalisés, délocalisés en fonction des besoins de l’économie » [36].

Aussi louables soient-elles, ces intentions (favoriser la libération de l’individu, garantir la paix) apparaissent donc, dans une large mesure, comme des totems visant à désamorcer, délégitimer les critiques apportées à l’extension radicale du projet libéral et particulièrement, aujourd’hui, la mise en œuvre par l’Union européenne de politiques ultra-libérales. Ces critiques visent à mettre à jour la réalité du modèle libéral en tant qu’il constitue certes un système de création de richesses et de valeur efficace mais ce au prix d’une destruction sans précédent de l’environnement [37]et d’un formidable accroissement des inégalités, cette richesse étant captée à grande échelle par un petit nombre d’individus [38]. Au sein des sociétés occidentales, il s’accompagne également d’une hausse inédite de la pauvreté [39]. En outre, ce modèle ultra-libéral favorise une immigration massive qui contribue à menacer gravement le cadre de vie et la sécurité des populations autochtones, et ce au nom du respect du principe de libre circulation des facteurs de production, qui constitue l’une des conditions essentielles permettant de caractériser un marché concurrentiel dans la théorie économique néo-classique libérale [40].

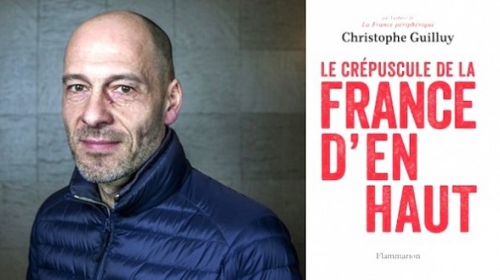

Insécurité physique, corporelle tout d’abord : un lien entre immigration massive, société multiculturelle et hausse de la délinquance semble pouvoir être établi. Dans le cas de la France, un rapport sur l’islam radical en prison rédigé par le député Guillaume Larrivé en 2014 a mis en évidence que les musulmans constituaient environ 60 % de la population carcérale totale alors même qu’ils ne représenteraient qu’environ 12% de la population française. Insécurité culturelle ensuite qui provient de la peur des populations autochtones de devenir minoritaires dans leur propre pays, c’est-à-dire de perdre leur statut de référent culturel. Comme le relève Christophe Guilluy (photo), cette crainte universelle est ressentie dans tous les pays qui subissent des flux migratoires massifs (pays occidentaux, pays du Maghreb…) [41].

Enfin, sur le plan économique, des travaux ont montré qu’une forte hétérogénéité ethnique au niveau local allait de pair avec une dégradation des services publics essentiels comme l’éducation ou encore les infrastructures routières et nécessitait des transferts sociaux plus importants que dans les zones à forte homogénéité ethnique [42]. Ainsi, les auteurs de cette étude en concluent que les sociétés à forte hétérogénéité se caractérisent par une moindre importance accordée à la qualité des biens publics, un développement du paternalisme et des niveaux de déficit et d’endettement plus élevés. Dans le même sens, Christophe Guilluy dans son ouvrage, la France périphérique, souligne que la politique de la ville s’est avérée être un puissant instrument de redistribution au profit quasi-exclusif des banlieues dites « sensibles », c’est-à-dire des zones à forte concentration immigrée [43].

Enfin, sur le plan économique, des travaux ont montré qu’une forte hétérogénéité ethnique au niveau local allait de pair avec une dégradation des services publics essentiels comme l’éducation ou encore les infrastructures routières et nécessitait des transferts sociaux plus importants que dans les zones à forte homogénéité ethnique [42]. Ainsi, les auteurs de cette étude en concluent que les sociétés à forte hétérogénéité se caractérisent par une moindre importance accordée à la qualité des biens publics, un développement du paternalisme et des niveaux de déficit et d’endettement plus élevés. Dans le même sens, Christophe Guilluy dans son ouvrage, la France périphérique, souligne que la politique de la ville s’est avérée être un puissant instrument de redistribution au profit quasi-exclusif des banlieues dites « sensibles », c’est-à-dire des zones à forte concentration immigrée [43].

En résumé, les pays européens connaissent aujourd’hui une situation dans laquelle une part croissante de la population subit de profondes mutations qui menacent son identité, avec le sentiment que seule une petite élite est capable de se mettre à l’abri des conséquences négatives de ces mutations. Cette situation apparaît de plus en plus visiblement liée à un modèle libéral qui s’avère être un système des plus profitables pour une minorité et un laminoir pour les couches populaires et la classe moyenne, comme il le fut déjà au XIXème siècle. Tous les ingrédients semblent donc réunis pour que ce que l’on qualifie généralement de populisme, souvent pour le discréditer, gagne du terrain.

Le populisme, un modèle en quête d’une troisième voie ?

En réponse à la crise identitaire causée par les bouleversements induits par la mondialisation libérale et par la perte de sens ressentie par les individus des sociétés occidentales, on observe un développement des mouvements populistes qui apparaissent ainsi comme une des formes les plus visibles des réveils identitaires en cours. En effet, les mouvements populistes actuels ont le plus souvent pour caractéristique commune de contester des élites acquises à la mondialisation libérale.

Toutefois, la notion même de populisme est problématique pour deux raisons : d’une part la très grande diversité des mouvements qualifiés de populistes et d’autre part l’usage polémique qui est fait de ce terme [44]. En effet, la réduction du populisme aux mouvements populistes des années 1930 apparaît comme un artifice rhétorique régulièrement utilisé pour discréditer le populisme, alors conçu comme une simple entreprise anti-démocratique d’instrumentalisation des masses faisant appel aux instincts les plus vils des individus plutôt qu’à leur raison.

Or, cette conception réductrice du populisme, à visée idéologique, ne permet pas de caractériser l’ensemble des mouvements populistes, et notamment pas le populisme russe et nord-américain de la seconde moitié du XIXèmesiècle ni même les mouvements latino-américains du XXème siècle [45]. En outre, elle tend à masquer la critique pertinente, portée par les mouvements populistes, qui consiste à mettre en lumière la crise de légitimité qui affecte les démocraties représentatives dans les pays occidentaux, en tant qu’elles sont confisquées par des oligarchies étatiques ou transnationales [46]. La profonde remise en cause des identités nationales causée par la mondialisation libérale constitue donc le principal facteur explicatif non seulement de la crise des démocraties occidentales mais aussi en retour, du développement du populisme. Ainsi, comme le remarque Guy Hermet, « le populisme comme la démocratie est intrinsèquement lié au cadre national » [47].

Si la très grande diversité des mouvements populistes rend illusoire tout accord sur une définition unique, on peut néanmoins tenter d’énoncer les principales caractéristiques du populisme. Tout d’abord, il s’agit d’un style de discours, un appel au peuple qui exalte une communauté (peuple demos, c’est-à-dire la communauté des citoyens et/ou peuple ethnos, c’est-à-dire une communauté ethno-culturelle) en tant qu’elle est porteuse de valeurs positives (vertu, bon sens, simplicité, honnêteté,…) et qu’elle s’oppose à une élite au pouvoir, considérée comme délégitimée. Ensuite, le populisme ne s’incarne pas dans un régime politique particulier (une démocratie ou une dictature peuvent avoir une orientation populiste) ni même ne revêt en soi un contenu idéologique déterminé : il se caractérise par la recherche d’une 3ème voie entre le libéralisme et le marché d’une part et le socialisme et l’Etat-Providence de l’autre [48]. En cela, il se veut un dépassement du clivage droite-gauche [49].

Si la très grande diversité des mouvements populistes rend illusoire tout accord sur une définition unique, on peut néanmoins tenter d’énoncer les principales caractéristiques du populisme. Tout d’abord, il s’agit d’un style de discours, un appel au peuple qui exalte une communauté (peuple demos, c’est-à-dire la communauté des citoyens et/ou peuple ethnos, c’est-à-dire une communauté ethno-culturelle) en tant qu’elle est porteuse de valeurs positives (vertu, bon sens, simplicité, honnêteté,…) et qu’elle s’oppose à une élite au pouvoir, considérée comme délégitimée. Ensuite, le populisme ne s’incarne pas dans un régime politique particulier (une démocratie ou une dictature peuvent avoir une orientation populiste) ni même ne revêt en soi un contenu idéologique déterminé : il se caractérise par la recherche d’une 3ème voie entre le libéralisme et le marché d’une part et le socialisme et l’Etat-Providence de l’autre [48]. En cela, il se veut un dépassement du clivage droite-gauche [49].

Enfin, le populisme tend à émerger dans des périodes de changements profonds et/ou de crise de légitimité c’est-à-dire, en particulier, de crise du système de représentation [50]. Pour Christopher Lasch, la cause profonde du développement actuel du populisme, ainsi d’ailleurs que du communautarisme, résiderait dans le déclin des Lumières que révèlent les doutes croissants sur l’existence d’un système de valeurs qui transcenderait les particularismes [51].

Les populismes qui s’affirment actuellement, notamment dans les pays occidentaux, combinent pour beaucoup une double dimension protestataire et identitaire. La dimension protestataire se manifeste par un appel au peuple demos (les citoyens) à l’encontre d’élites accusées d’avoir confisqué le pouvoir par le biais de fausses alternances et ainsi d’avoir transformé la démocratie en une oligarchie. La dimension identitaire se manifeste par un appel au peuple ethnos qui vise à critiquer les effets néfastes de l’immigration massive ainsi que les politiques prônant le multiculturalisme et la diversité. C’est en jouant sur ces deux registres que Donald Trump a pu remporter l’élection présidentielle américaine de 2016. En effet, la campagne de Trump a été, en quelque sorte, la mise en application des analyses développées en 2004 par Samuel Huntington dans son ouvrage Who are we ? America’s Great Debate, traduit en Français sous le titre Qui somme nous ? Identité nationale et choc des cultures.

Pour Huntington, depuis la fin du mouvement des droits civiques dans les années 1965 qui a fait des Afro-Américains des citoyens de plein exercice, l’identité nationale américaine ne se définit plus par un critère racial et ne revêt plus que deux dimensions : une dimension culturelle (c’est-à-dire la culture anglo-protestante des XVIIème-XVIIIème siècles, héritée des Pères fondateurs) et une dimension politique (« the Creed ») constituée des grands principes à vocation universaliste que sont la liberté, l’égalité, la démocratie, les droits civiques, la non-discrimination, l’Etat de droit [52] (principes qui sont, en quelque sorte, l’équivalent de ce que l’on désigne habituellement en France par « valeurs républicaines »). Or, Huntington souligne que l’identité américaine est gravement menacée pour deux raisons.

Pour Huntington, depuis la fin du mouvement des droits civiques dans les années 1965 qui a fait des Afro-Américains des citoyens de plein exercice, l’identité nationale américaine ne se définit plus par un critère racial et ne revêt plus que deux dimensions : une dimension culturelle (c’est-à-dire la culture anglo-protestante des XVIIème-XVIIIème siècles, héritée des Pères fondateurs) et une dimension politique (« the Creed ») constituée des grands principes à vocation universaliste que sont la liberté, l’égalité, la démocratie, les droits civiques, la non-discrimination, l’Etat de droit [52] (principes qui sont, en quelque sorte, l’équivalent de ce que l’on désigne habituellement en France par « valeurs républicaines »). Or, Huntington souligne que l’identité américaine est gravement menacée pour deux raisons.

D’une part, la dimension politique de l’identité américaine est en elle-même fragile en ce que les principes qui la composent étant universels, ils ne permettent pas de distinguer les Américains d’autres peuples et donc de constituer une communauté qui fasse sens pour les individus [53]. A cet égard, Huntington remarque que le communisme qui aura duré 70 ans a laissé place à un regain identitaire à caractère ethno-culturel dans les pays d’Europe de l’Est et en Russie [54].

D’autre part, la dimension culturelle de l’identité nationale américaine est elle-même en passe d’être remise en cause du fait de l’immigration massive, en particulier d’origine hispanique (développement du bilinguisme [55], d’une éducation multiculturelle [56], craintes de revendications voire de sécessions territoriales par exemple en Californie [57]) et de l’action des élites politiques, judiciaires, économiques et médiatiques qui soutiennent et encouragent le développement du multiculturalisme et de la diversité, c’est-à-dire les revendications identitaires croissantes de type racial et ethnique de la part des minorités [58].

Ainsi, tout en proférant une dénonciation féroce contre les élites corrompues (« l’establishment », le « clan » Clinton), le candidat Trump s’est attaché à prendre en compte cette dimension culturelle (entendue au sens large comme mode de vie) de l’identité nationale américaine en proposant des mesures susceptibles de répondre aux craintes de nombreux Américains face à la dégradation de leur cadre de vie (mesures protectionnistes face à la désindustrialisation et au chômage, lutte contre la délinquance et contre l’immigration illégale notamment mexicaine). Le programme de Trump en conjuguant libéralisme (remise en cause de l’Obamacare) et nationalisme (mesures protectionnistes vis-à-vis de la Chine et du Mexique) met en lumière le syncrétisme idéologique du populisme qui s’affirme en effet comme un modèle en quête d’une troisième voie.

En Europe, l’essor des partis qualifiés de populistes [59] résulte également d’une combinaison des deux dimensions, protestataire et identitaire, avec des degrés variables. L’abstention massive aux élections et/ou le vote pour les partis « hors-système » traduisent la dimension protestataire qui s’explique par le décalage croissant entre d’une part les couches populaires et une frange croissante de la classe moyenne et d’autre part les élites, qu’elles soient politiques, économiques ou médiatiques, auxquelles il est reproché de fausser le jeu démocratique et de confisquer le pouvoir par le biais de fausses alternances. La dimension identitaire est elle aussi vivace du fait d’une immigration incontrôlée d’origine extra-européenne, notamment de culture musulmane. La succession des attentats islamistes en Europe (à Paris, Nice, Bruxelles et Berlin pour ne prendre que les plus récents) ravive le souvenir des luttes séculaires à l’encontre des conquêtes musulmanes en Europe.

Selon C. Guilluy le rejet de cette immigration de masse, qui concerne tous les pays et s’explique par la peur de devenir minoritaire et de perdre le statut de référent culturel, va bien au-delà du vote FN et se traduit par exemple par des phénomènes tels que le contournement de la carte scolaire ou encore la constitution de zones d’habitation séparées [60]. Ainsi, Christophe Guilluy identifie, sur une base géographique, les contours de trois ensembles socioculturels qui se construisent contre la volonté des pouvoirs publics : les catégories populaires, engagées dans un processus de ré-enracinement, qui se relocalisent dans la France périphérique, c’est-à-dire dans les zones géographiques les moins dynamiques économiquement, les catégories populaires d’immigration récente qui se concentrent dans les quartiers de logements sociaux des grandes métropoles et enfin les catégories supérieures, concentrées dans le parc privé de ces mêmes métropoles [61].

Face à ces dynamiques socioculturelles en cours que traduit, au plan politique, l’essor des partis populistes, il reste à s’interroger sur les voies par lesquelles pourrait être ravivée une identité culturelle, civilisationnelle créatrice de sens, c’est-à-dire qui répondrait « à la volonté, de plus en plus manifeste du peuple français, de retrouver en partage un monde commun de valeurs, de signes et de symboles qui ne demandait qu’à resurgir à la faveur des épreuves à venir » [62].

Les leviers d’action métapolitiques

On l’a vu les réveils identitaires peuvent s’analyser comme une tentative de réponse à une crise identitaire caractérisée par la perte de sens au niveau individuel et par la dissolution des identités collectives. Comme le relève Patrick Buisson (photo), cela conduit à se poser « la question qui est au centre de la société française : comment redéployer les solidarités perdues, comment relier de nouveau les individus entre eux ? » [63] Autrement dit, l’enjeu est de retrouver des cadres, des horizons communs qui fassent sens pour l’individu contemporain. A cet égard, il est sans doute illusoire de croire que reviendra le temps où l’identité individuelle était entièrement absorbée par les identités collectives issues des communautés traditionnelles (religieuses, familiales…) et ne s’en distinguaient pas ou peu. L’identité individuelle est devenue plus mouvante, fluide. Avec la modernité, la composante choisie de l’identité a pris le pas sur la dimension héritée.

On l’a vu les réveils identitaires peuvent s’analyser comme une tentative de réponse à une crise identitaire caractérisée par la perte de sens au niveau individuel et par la dissolution des identités collectives. Comme le relève Patrick Buisson (photo), cela conduit à se poser « la question qui est au centre de la société française : comment redéployer les solidarités perdues, comment relier de nouveau les individus entre eux ? » [63] Autrement dit, l’enjeu est de retrouver des cadres, des horizons communs qui fassent sens pour l’individu contemporain. A cet égard, il est sans doute illusoire de croire que reviendra le temps où l’identité individuelle était entièrement absorbée par les identités collectives issues des communautés traditionnelles (religieuses, familiales…) et ne s’en distinguaient pas ou peu. L’identité individuelle est devenue plus mouvante, fluide. Avec la modernité, la composante choisie de l’identité a pris le pas sur la dimension héritée.

Dans ce contexte, et face aux menaces qui pèsent sur le cadre de vie des peuples européens, il parait urgent de s’interroger sur les actions à entreprendre en vue d’accompagner les réveils identitaires en cours. Pour guider l’action, deux principes, qui sont liés, nous paraissent pouvoir être mis en avant. D’une part, la lutte contre l’atomisation de la société (résultant de l’individualisme méthodologique, au fondement des théories économiques néo-classiques) en créant des cadres, des cercles, des organisations permettant que se réalise le processus d’identification par lequel chacun peut se définir comme appartenant à un collectif. D’autre part, les logiques de don, de contre-don et de coopération devraient être privilégiées au détriment de la prééminence des intérêts individuels afin de créer des tissus de relations, des rapports de dépendance entre les membres du groupe, et ainsi de renforcer son identité collective [64].

On se focalisera ici sur deux domaines d’action : l’éducation et le domaine économique.

Le déclin du système éducatif français, mesuré notamment par les classements PISA, fait l’objet d’un constat unanime, hormis peut-être parmi les promoteurs de l’idéologie pédagogiste, principaux responsables de la « situation de détresse » et de « banqueroute programmée » [65] de l’école. Cette idéologie néfaste qui prône un égalitarisme radical a eu pour conséquence paradoxale de générer l’inégalité la plus criante qui se manifeste à plusieurs niveaux : accroissement de l’illettrisme, faiblesse de la circulation et du renouvellement des élites, mise en œuvre de mesures de discrimination positive, etc.

Mais au-delà du pédagogisme qui constitue en quelque sorte une cause immédiate de l’effondrement du système éducatif, la cause profonde de cet effondrement est à chercher dans une crise, un déclin de l’autorité, telle que l’entendait Hannah Arendt, c’est-à-dire de « la conviction du caractère sacré de la fondation, au sens où une fois que quelque chose a été fondé il demeure une obligation pour toutes les générations futures » [66]. Or, poursuit Arendt, « dans le monde moderne, le problème de l’éducation tient au fait que par sa nature même l’éducation ne peut faire fi de l’autorité, ni de la tradition, et qu’elle doit cependant s’exercer dans un monde qui n’est pas structuré par l’autorité ni retenu par la tradition » [67].

Dans ce contexte, il parait impérieux de restaurer des structures de transmission culturelle inspirées de modèles éprouvés, c’est-à-dire régies par des principes visant à rétablir des objectifs d’excellence et à susciter l’émulation (modèle jésuite), à former le caractère autant que l’intelligence (modèle de l’école française républicaine), à valoriser la tradition qui définit l’identité (modèle des public schools britanniques) et à restaurer l’autorité et la discipline en associant à cette entreprise les intéressés eux-mêmes (modèle jésuite) [68].

Dans cette perspective, il s’agit d’encourager les initiatives visant à la création d’écoles hors contrat s’inspirant des modèles éducatifs ayant fait la preuve de leur efficacité mais également d’associations à vocation éducative et culturelle ayant pour objet la transmission des valeurs et des savoirs, tel l’Institut Iliade, dont on pourrait imaginer un développement sur le modèle des Lancastrian schools. A cet égard, il serait intéressant de créer une plateforme sur Internet recensant les différents projets existants afin de leur donner une meilleure visibilité et de permettre ainsi à un plus large public d’y adhérer voire d’y contribuer. La possibilité de financements participatifs (crowdfunding) pourrait aussi être envisagée.

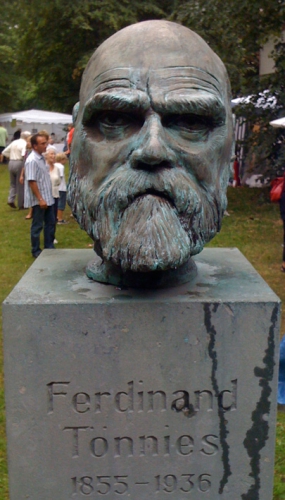

Dans le domaine économique, un large champ d’actions à vocation identitaire parait ouvert, qui peut s’appuyer sur des fondements théoriques permettant de s’abstraire de la pure logique marchande. A cet égard, le courant de la Nouvelle Sociologie Economique auquel on peut rattacher les travaux de Mark Granovetter (photo) sur les réseaux, vise notamment à remettre en cause la vision sous-socialisée des relations économiques qui est celle de l’individualisme méthodologique et qui fonde les théories néo-classiques. Pour Granovetter, l’économie n’est qu’un sous-ensemble qui s’inscrit au sein d’un ensemble plus vaste et construit à partir d’une logique proprement sociale.

Dans le domaine économique, un large champ d’actions à vocation identitaire parait ouvert, qui peut s’appuyer sur des fondements théoriques permettant de s’abstraire de la pure logique marchande. A cet égard, le courant de la Nouvelle Sociologie Economique auquel on peut rattacher les travaux de Mark Granovetter (photo) sur les réseaux, vise notamment à remettre en cause la vision sous-socialisée des relations économiques qui est celle de l’individualisme méthodologique et qui fonde les théories néo-classiques. Pour Granovetter, l’économie n’est qu’un sous-ensemble qui s’inscrit au sein d’un ensemble plus vaste et construit à partir d’une logique proprement sociale.

A la vision de l’individu rationnel maximisant ses intérêts privés, il oppose la vision d’acteurs insérés, encastrés dans des réseaux de relations sociales. L’encastrement, concept clé de Granovetter, revêt une triple dimension. Tout d’abord, une dimension cognitive dans la mesure où la rationalité de l’individu est limitée et non absolue. Une dimension culturelle, ensuite, au sens où l’action économique est inspirée par des valeurs, des croyances et des habitudes culturelles. Une dimension structurelle, enfin, car les relations économiques sont insérées dans des systèmes durables et concrets de relations sociales, c’est-à-dire des réseaux interpersonnels, fondés sur des logiques d’appartenance, de communauté, voire des normes de réciprocité.

Or, les travaux de Granovetter ont montré que des marchés fortement encastrés permettaient d’une part d’accroitre la confiance entre les agents et d’autre part d’améliorer la circulation et la qualité de l’information, deux conditions nécessaires à la réalisation d’activités économiques. Les groupes d’affaires (zaïbatsu japonais, chaebols coréens, grupos americanos d’Amérique latine…), liés par des relations de confiance interpersonnelle sur la base d’une même origine personnelle ethnique ou communautaire, constituent un des nombreuses applications du concept d’encastrement [69]. De plus, la nature des liens sociaux au sein du réseau est également déterminante, y compris dans le domaine économique.

A cet égard, Granovetter établit la distinction devenue classique entre liens forts et liens faibles : « la force ou la faiblesse d’un lien est une combinaison de la quantité de temps, de l’intensité émotionnelle, de l’intimité (la confiance mutuelle) et des services réciproques qui caractérisent ce lien » [70]. Cette distinction met en évidence l’intérêt des liens faibles [71] : « plus grande est la proportion des liens faibles, plus grand est l’accès aux informations ; plus grande est la proportion de liens forts, plus grande est la probabilité qu’une information soit redondante et que le groupe se constitue en clique » [72]. Appliquée à l’entrepreneuriat, Granovetter a toutefois montré la prédominance des liens forts au démarrage de l’entreprise et l’importance des liens faibles dans la phase de développement [73].

Encastrement au sein d’un réseau, liens forts, liens faibles sont des concepts qui se sont révélés particulièrement riches pour expliquer notamment les comportements sur le marché du travail, l’innovation (clusters) ou encore l’entrepreneuriat. Ainsi, l’entrepreneuriat ethnique ou identitaire peut être analysé à la lumière de ces notions. L’économie du Pays basque en est un exemple typique : succès de la marque « 64 », fondé sur l’attachement à l’identité basque, les produits identitaires (bière basque, Cola basque…), le succès de la coopérative Mondragon au Pays basque espagnol [74]…

L’entrepreneuriat ethnique, analysé par Edna Bonacich [75], peut également servir, dans une certaine mesure, de source d’inspiration. Cet auteur relève que certaines minorités ethniques (les Arméniens en Turquie, les Juifs en Europe, les Syriens en Afrique de l’Ouest, les Chinois en Asie du Sud-Est, les Japonais ou les Grecs aux Etats-Unis) ont pour spécificité de jouer, au plan économique, un rôle d’intermédiaire (activités commerciales, de location, de prêt…) entre producteur et consommateur [76]. Les modes d’organisation de ces minorités, dont les liens communautaires sont très forts [77], méritent d’être analysés, notamment sur le plan économique [78].

Aujourd’hui, on observe également des initiatives, attestant d’un certain réveil identitaire en matière économique, qui méritent d’être encouragées : tentatives de développement d’un tourisme identitaire manifestant l’attachement aux territoires ruraux [79], apparition de tentatives d’intégration verticale dans le domaine agricole (reprise par une coopérative d’agriculteurs de l’abattoir du Vigan [80] en vue de garantir un traitement éthique des animaux [81])…

Les réveils identitaires en matière économique pourraient aussi à l’avenir se manifester par des actions de boycott (on pense notamment à la viande issue de l’abattage rituel). Pour certains, le boycott serait au modèle postindustriel ce que la grève était au modèle industriel. Dans le modèle capital contre travail, le contre-pouvoir vient du fait que le travailleur peut priver le patron de sa puissance de travail. Le boycott constituerait quant à lui une forme possible de contre-pouvoir face à une économie mondialisée, l’arme d’une société civile mondiale forte de son pouvoir d’achat [82].

L’efficacité du boycott dépend de la capacité à créer une identité collective autour de l’événement, ce qui implique de réunir toute une série de conditions [83] : définition d’objectifs clairs, réalistes et mesurables formulés dans un message intellectuellement simple et attractif sur le plan émotionnel, soutien des médias [84], l’existence d’une cible clairement identifiée, l’existence d’une solution alternative offerte au consommateur qui soit notamment identifiable [85] et une forte solidarité du groupe mobilisé (existence de réseaux bien organisés). Dans le cas de la viande hallal, l’une des difficultés consiste dans l’impossibilité d’identifier aisément les alternatives du fait du non étiquetage du mode d’abattage.

Les réveils identitaires qui se manifestent dans la période actuelle sont multiformes : ils se traduisent au plan politique, notamment à travers la montée des populismes, mais sont également perceptibles dans le domaine de l’éducation et de l’économie. Aurait aussi mérité d’être évoqué le domaine social et notamment le thème de l’exclusion [86] ; domaine qu’investissent fortement les minorités, notamment de confession musulmane, qui y voient la mise en application du concept de « citoyenneté croyante » développé par Tariq Ramadan [87]. Il aurait également été intéressant d’aborder la question du développement de réseaux communautaires à l’échelle européenne et de réfléchir à des formes d’action commune.

Ces réveils identitaires ne sont pas surprenants. Avec le déclin des identités collectives et des sociabilités issues des grands récits eschatologiques caractéristiques de la modernité, eux-mêmes en voie d’effacement [88], la quête d’identité devient un enjeu toujours plus crucial pour l’individu contemporain : « les hommes et les femmes recherchent des groupes auxquels ils peuvent appartenir assurément et pour toujours, dans un monde dans lequel tout le reste bouge et change » [89]. Dans ce contexte, la recherche de cadres, d’horizons communs et de récits adaptés permettant au processus d’identification de se réaliser reste bien le grand défi actuel.

Étienne Malret

Mémoire de fin de cycle de formation ILIADE

Promotion Don Juan d’Autriche, 2016/201

Annexe 1 : Liens faibles et organisations communautaires [90]

Analysant la nature des liens sociaux structurant les réseaux à partir du cas de deux communautés habitant deux quartiers distincts de Boston, soumis à des plans de « rénovation urbaine » visant in fine à la destruction de ces quartiers, Granovetter se pose la question essentielle suivante : pourquoi certaines communautés s’organisent aisément et efficacement en vue de l’accomplissement de buts communs (en l’espèce la défense d’un quartier d’habitation) alors que d’autres semblent incapables de mobiliser des ressources même face à des menaces pressantes ?

Pour l’auteur, la cause de l’incapacité de l’une des communautés (en l’espèce une communauté d’origine italienne) à s’organiser pour la défense de son quartier réside dans la nature des liens sociaux qui structurent cette communauté. Ainsi, il observe que la communauté italienne se caractérise d’une part, par l’existence de liens forts au sein des sous-groupes (familles, amis…) constitutifs de cette communauté et d’autre part, par une fragmentation globale de la communauté. Cette fragmentation globale s’explique par le manque de liens faibles entre les sous-groupes (les cliques selon sa terminologie), attesté par la pauvreté du tissu associatif et par le fait que très peu d’habitants de cette communauté travaillent au sein même du quartier. A l’inverse, la communauté ouvrière de Charleston, l’autre quartier de Boston soumis au plan de rénovation, a réussi à s’organiser efficacement contre un tel plan. Selon Granovetter, la raison en est que cette communauté possédait une vie associative riche et que presque tous les hommes résidaient et travaillaient au sein même du quartier.

Cet exemple montre l’importance et la force des liens faibles ainsi que le risque d’enfermement qu’induit l’existence de liens forts.

Annexe 2 : The middleman theory

L’organisation de certaines communautés ethniques très intégrées, étudiées par Edna Bonacich dans son article « A theory of Middleman Minorities », repose sur plusieurs spécificités. Tout d’abord, des mécanismes de financement intra-communautaires préférentiels sont mis en place : prêts à taux bas voire à taux zéro, système de la parentèle (pot commun abondé par les versements réguliers des membres de la communauté) au profit des membres de la communauté en vue notamment de leur permettre de démarrer une activité indépendante. Ensuite, une maîtrise de la chaîne de valeur est recherchée, dans la mesure du possible, par une intégration verticale des activités économiques, notamment dans le domaine agricole. Enfin, des salaires bas et une vie communautaire qui, combinés aux mécanismes de financement intra-communautaires et à un fort taux d’épargne, permettent d’abaisser les coûts de revient et d’être compétitifs.

Les succès économiques de ces minorités ethniques (en particulier les Chinois, les Indiens et les Juifs) aboutissent à des phénomènes de concentration et de domination sectorielle (surtout dans le commerce) qui s’observent partout dans le monde. Ces succès liés à l’efficacité de l’organisation de cette économie communautaire sont aussi attestés par les tensions et conflits générés du fait de l’intensification de la concurrence économique.

Notes

[1] Cf. Denise Jodelet : « Le mouvement de retour vers le sujet et l’approche des représentations sociales », Connexions 2008/1 (n°89), p. 25-46.

[2] Cf. Pierre-André Taguieff : « L’idée de progrès, la «religion du Progrès» et au-delà. Esquisse d’une généalogie », Krisis n°45 – Progrès ?

[3] « L’identité est un produit de la conscience de soi ; conscience que l’on possède, individuellement ou collectivement, des qualités distinctes qui nous différencient des autres » (Samuel Huntington, Who are we ? America’s Great Debate, Free Press, 2005, p.21).

[4] Charles Taylor, Les sources du moi. La formation de l’identité moderne, Seuil, 1998, p.46.

[5] Alain de Benoist, « Identité, égalité, différence » in Critiques – Théoriques, L’Age d’Homme, 2002, p. 418.

[6] Paul Ricoeur, Temps et récit, tome 3 : Le temps raconté, Points Seuil, 1991 (3ème édition), p.443.

[7] Paul Ricoeur, op. cit., p.444.

[8] Opposition résolue des pays dits du « Groupe de Visegrad » à la politique migratoire de l’UE, élection présidentielle française, etc.

[9] Tous les enjeux posés dans l’ouvrage précité de Huntington sont au cœur de l’élection présidentielle américaine de 2016.

[10] Gilbert Durand, L’imagination symbolique, Paris, PUF, 1964, p.23.

[11] Leo Strauss, La philosophie politique et l’histoire, Le livre de poche, p.212 et s.

[12] Ainsi, parmi les menaces pesant sur l’identité nationale des Etats-Unis, Samuel Huntington mentionne notamment la mondialisation et le cosmopolitisme (cf. Samuel Huntington : op. cit., p.4.). Néanmoins, si les identités nationales apparaissent aujourd’hui particulièrement menacées par la mondialisation libérale, il faut aussi remarquer qu’elles sont elles-mêmes le produit de la modernité, comme l’a montré Louis Dumont. Dès lors, la crise des identités nationales peut également s’analyser, dans une large mesure, comme la résultante de contradictions internes à l’idée même d’Etat-Nation.

[13] « C’est une idéologie allergique à tout ce qui spécifie, qui interprète toute distinction comme potentiellement dévalorisante ou dangereuse, qui tient les différences que l’on peut constater entre les individus et les groupes comme contingentes, transitoires, inessentielles ou secondaires. Son moteur est l’idée d’Unique. L’unique est ce qui ne supporte pas l’Autre, et entend ramener tout à l’unité : Dieu unique, civilisation unique, pensée unique » (Alain de Benoist, op. cit., p. 413).

[14] Charles Taylor, op. cit., p.623-624.

[15] Michel Maffesoli, Le Temps des tribus – Le déclin de l’individualisme dans les sociétés postmodernes, La Table Ronde, 2000, préface à la 3ème édition, p. V et VI.

[16] A cet égard, Huntington relève que l’affaiblissement de l’identité nationale des Etats-Unis du fait de la mondialisation a laissé place à une affirmation des identités ethniques, raciales et des identités liées au genre (cf. Samuel Huntington : op. cit., p.4).

[17] Revue Eléments n°131, avril-juin 2009, entretien avec Alexandre Douguine.

[18] Revue Eléments n°131, avril-juin 2009, p.36.

[19] Cf. le débat édifiant diffusé sur Arte, à l’occasion de l’affaire des viols de Cologne, au cours duquel les journalistes reconnaissent eux-mêmes l’existence de ce traitement de faveur réservé aux délinquants d’origine immigrée. Un extrait de ce débat peut être visionné sur Internet (http://www.ojim.fr/occultation-de-lorigine-des-delinquants-dans-les-medias-laveu-de-quatremer/).

[20] Christopher Lasch, La révolte des élites et la trahison de la démocratie, Flammarion, 2007, p.144. Selon Lasch, ces politiques de discrimination positive vont non seulement profondément à l’encontre de la culture américaine, fondée sur la prééminence de la responsabilité individuelle, mais elles constituent aussi une cause d’échec pour la majorité des individus appartenant à ces minorités dans la mesure où, intériorisant leur statut de victimes, ils éprouvent souvent de plus grandes difficultés à acquérir le respect d’eux-mêmes.

[21] Christopher Lasch, op. cit., p.145-146.

[22] Samuel Huntington : op. cit., p.344.

[23] Jacques Le Goff, l’Europe est-elle née au Moyen Age ?, Seuil, 2003, p.196.

[24] Jacques Le Goff, op. cit., p.258.

[25] En témoigne la filmographie parfois qualifiée de « réactionnaire » qui connait de larges succès d’audience : Le fabuleux destin d’Amélie Poulain, La famille Bélier…

[26] Alain de Benoist, « Critique de l’idéologie libérale » in Critiques – Théoriques, L’Age d’Homme, 2002, p.13 : « Le libéralisme est une doctrine qui se fonde sur une anthropologie de type individualiste, c’est-à-dire qu’elle repose sur une conception de l’homme comme être non fondamentalement social ». Pour l’auteur, se fondant notamment sur les travaux de Louis Dumont, les deux traits caractéristiques du libéralisme, à savoir la notion d’individu et celle de marché « sont directement antagonistes des identités collectives ».

[27] Luc Boltanski et Eve Chiapello, Le nouvel esprit du capitalisme, Gallimard, 2011, p.55.

[28] Cf. Marc Muller « Les Lumières contre la guerre civile – Le libéralisme ou l’idéologie du Même », Nouvelle Ecole n°65, 2016, p.34.

[29] Jean-Claude Michéa, L’empire du moindre mal – Essai sur la civilisation libérale, Flammarion, 2007, p.28 : « En replaçant ainsi la question de la pacification de la société au centre des problèmes, il devient plus facile de penser à la fois l’originalité absolue du projet moderne, les principes de l’anthropologie qui l’accompagnent et, surtout, l’unité profonde des deux figures philosophiques sous lesquelles le libéralisme va porter ce projet à son accomplissement logique ».

[30] Jean-Claude Michéa, op. cit., p.52.

[31] Cf. Marc Muller, article précité, p.37.

[32] « La paix est un souhait, la guerre est un fait », éditorial de la revue Conflits, hors-série n°1 (Hiver 2014) relatif à la guerre économique, p.5.

[33] Cf. Hervé Coutau-Bégarie: « A quoi sert la guerre ? », Krisis n°34, juin 2010 – La guerre (2) ?, p.19. Pour C. Lasch, ces mouvements d’unification et de fragmentation sont liés à l’affaiblissement de l’Etat-Nation. Affaiblissement lui-même causé par le déclin de la classe moyenne sur laquelle s’étaient appuyés les fondateurs des nations modernes dans leur combat contre la noblesse féodale. Ainsi, selon C. Lasch, la culture de la classe moyenne (sens du territoire et respect pour la continuité historique) qui servait de cadre de référence commun est en train de se décomposer pour laisser place à des factions rivales (Christopher Lasch, op. cit., p.59-60).

[34] Pascal Gauchon, « Guerre civile. Guerre de la mondialisation », Revue Conflits, Avril-Mai-Juin 2016, p.46.

[35] Cf. Marc Muller, article précité, p.35.

[36] Cf. Marc Muller, article précité, p.36.

[37] Jean-Claude Michéa relève à cet égard que « la seule guerre qui demeurera concevable, dans un tel dispositif philosophique, est la guerre de l’homme contre la nature, conduite avec les armes de la science et de la technologie ; guerre de substitution, dont les Modernes vont précisément attendre qu’elle détourne vers le travail et l’industrie la plus grande partie des énergies jusque-là consacrées à la guerre de l’homme contre l’homme » (Jean-Claude Michéa, op. cit., p.27).

[38] En France, les 10 % les plus riches captent un peu plus du quart (27 %) de la masse globale des revenus, presque dix fois plus que les 10 % les plus pauvres (2,9 %) [Note de l’Observatoire des inégalités en date du 21 janvier 2014]. Dans le monde, les inégalités moyennes au sein des pays sont plus grandes qu’il y a 25 ans (rapport de 2016 de la Banque mondiale intitulé « Taking on inequality »).

[39] Ainsi, en France, plus d’un million de personnes ont basculé sous le seuil de pauvreté en dix ans. La population vivant sous le seuil de pauvreté représente plus de 14%, soit une personne sur sept. (Le Monde, daté du 8 septembre 2016).

[40] Les trois autres conditions permettant de caractériser un marché concurrentiel sont la condition d’atomicité des offreurs et des acheteurs, la condition d’homogénéité des produits, la condition de transparence de l’information. Cf. Olivier Torrès-Blay, Economie d’entreprise, Economica, 2009, 3ème édition, p.8.

[41] Christophe Guilluy, La France périphérique, Flammarion, 2014, p.134 et s.

[42] Alberto Alesina; Reza Baqir; William Easterly, « Public Goods and Ethnic Divisions », The Quarterly Journal of Economics, Vol. 114, No. 4. (Nov., 1999), pp. 1243-1284. Dans son ouvrage « Economie du bien commun », Jean Tirole conclut de cette étude que la préférence communautaire, la préférence nationale sont des réalités, qu’il déplore, mais dont il admet qu’il faut tenir compte dans la conception des politiques publiques (Jean Tirole, Economie du bien commun, PUF, 2016, p.92).

[43] Christophe Guilluy, op. cit., p.172.

[44] Pierre-André Taguieff « Le populisme et la science politique » in Les Populismes, sous la direction de Jean-Pierre Rioux, Perrin, 2007, p.17.

[45] Pierre-André Taguieff, op. cit., p.18-19

[46] Pierre-André Taguieff, L’illusion populiste, Flammarion, 2007, p.201.

[47] Guy Hermet, Les populismes dans le monde – Une histoire sociologique XIXème – XXème siècle, Fayard, 2001, p. 45.

[48] Christopher Lasch, La révolte des élites et la trahison de la démocratie, Flammarion, 2007, p.109

[49] Christopher Lasch, op. cit., p.110.

[50] Pierre-André Taguieff, « Le populisme et la science politique » in Les Populismes, sous la direction de Jean-Pierre Rioux, Perrin, 2007, p.25.

[51] Christopher Lasch, op. cit., p.101-102.

[52] Samuel Huntington : op. cit., p.38.

[53] Samuel Huntington : op. cit., p.342-343. Dans le même sens, cf. Emilio Gentile, Les religions de la politique – Entre démocraties et totalitarismes, Seuil, 2005, p.261 : l’auteur relève que, par rapport aux religions traditionnelles, les idéologies politiques, qu’il appelle les religions de la politique, revêtent un caractère éphémère.

[54] Ce qui justifia l’utilisation polémique du terme « populiste » pour qualifier, à la fin des années 1980, les dirigeants de ces pays (Boris Eltsine à ses débuts, Lech Walesa…), à la fin des années 1980, après l’effondrement des régimes communistes (cf. Guy Hermet, op. cit., p.58).

[55] Samuel Huntington : op. cit., p.162.

[56] Samuel Huntington : op. cit., p.176.

[57] Samuel Huntington : op. cit., p.233.

[58] Samuel Huntington : op. cit., Préface p.XVII.

[59] La Ligue du Nord en Italie, l’UDC en Suisse, le PVV aux Pays-Bas, le FN en France, le FPÖ en Autriche, le UKIP en Grande-Bretagne…

[60] Christophe Guilluy, op. cit., p.135-136 et p.150.

[61] Christophe Guilluy, op. cit., p.158-163.

[62] Patrick Buisson, La cause du peuple –L’histoire interdite de la présidence Sarkozy, Perrin, 2016, p.324.

[63] Patrick Buisson, op. cit., p.437.

[64] Strategor, Dunod, 2009, p.792.

[65] Ces termes sont ceux de Roger Fauroux ancien directeur de l’ENA, cité par Alain Kimmel dans son article « L’enseignement en France : état des lieux », Krisis n°38, Education ?, p.150-157.

[66] Hannah Arendt, La crise de la culture, huit exercices de pensée politique, Gallimard, coll. « Folio essais », 1989 [1972], p.159. H. Arendt précise que « le mot auctoritas dérive du mot augere, augmenter, et ce que l’autorité ou ceux qui commandent augmentent constamment : c’est la fondation. Les hommes dotés d’autorité étaient les anciens, le Sénat ou les patres qui l’avaient obtenue par héritage et par transmission de ceux qui avaient posé les fondations pour toutes les choses à venir, les ancêtres, que les Romains appelaient pour cette raison les maiores ». (H. Arendt, op. cit., p.160).

[67] Hannah Arendt, op. cit., p.250.

[68] Pour un panorama de ces modèles, cf. Jacques Berrel « Les modèles éducatifs qui ont fait l’Europe », la Nouvelle Revue d’Histoire n°26, Septembre-Octobre 2006, p.48-51.

[69] Isabelle Huault, « Embeddedness et théorie de l’entreprise – Autour des travaux de Mark Granovetter », Annales des Mines, Gérer et comprendre, Juin 1989, p.73-86. L’auteur précise que « la confiance et le partage de croyances (…) apparaissent comme des ingrédients essentiels pour atteindre le niveau de coordination souhaité ».

[70] Olivier Torrès-Blay, op. cit., p.263.

[71] Cf. Annexe 1.

[72] B. Chollet : « L’analyse des réseaux sociaux : quelles implications pour le champ de l’entrepreneuriat ? », 6èmeCongrès international francophone en entrepreneuriat et en PME, HEC Montréal, Octobre 2002, cité par Olivier Torrès-Blay, op. cit., p.266.

[73] Mark Granovetter, Le marché autrement, Essais de Mark Granovetter, Desclée de Brouwer, 2000, cité par Fabien Reix in « L’ancrage territorial des créateurs d’entreprises aquitains : entre encastrement relationnel et attachement symbolique », Géographie, économie et société, 2008/1 (Vol. 10), p.29-41.

[74] La coopérative Mondragon a souvent été érigée en modèle et ses succès économiques ont fait l’objet de nombreuses analyses : cf. notamment Philippe Durance, « La coopérative est-elle un modèle d’avenir pour le capitalisme ? – Retour sur le cas de Mondragon », Annales des Mines – Gérer et comprendre 2011/4 (N° 106), p.69-79 ; Jean-Michel Larrasquet, « Crise, coopératives, innovation et territoire », Projectics / Proyéctica / Projectique 2012/2 (n°11-12), p.157-167 ; Christina A. Clamp, « The Evolution of Management in the Mondragon Cooperatives », disponible sur Internet, à l’adresse : http://community-wealth.org/content/evolution-management-mondrag-n-cooperatives.

[75] « A theory of Middleman Minorities », American Sociological Review, Octobre 1973, p.583-594.

[76] Elle note à cet égard que ce phénomène est particulièrement observé dans les sociétés caractérisées par un fossé entre les élites et les masses comme par exemple dans les sociétés coloniales ou encore les sociétés féodales, marquées par la division entre masses paysannes et aristocratie. La fonction des minorités est alors de combler ce fossé.

[77] Résistance aux mariages extérieurs à la communauté, établissement d’écoles et d’associations de nature culturelle et linguistique pour leurs enfants, peu d’implication dans la politique locale sauf pour ce qui touche directement à leurs intérêts communautaires…

[78] Cf. Annexe 2.

[79] Cf. par exemple le site http://www.accueil-paysan.com/fr/

[80] Cet abattoir avait été fermé en 2016 pour cause de maltraitance animale.

[81] Pierre Isnard-Dupuy, Reporterre, le quotidien de l’écologie, « Des petits paysans veulent faire de l’abattoir du Vigan un exemple éthique », 17 février 2017 (article disponible en ligne sur le site www.reporterre.net).

[82] Cf. Ulrich Beck, cité par Ingrid Nyström et Patricia Vendramin in Le Boycott, Presses de Sciences Po (P.F.N.S.P.), 2015, p.93-120.

[83] Nyström et Patricia Vendramin, op. cit., p.93-120.

[84] Même si aujourd’hui, la capacité de contagion passe d’abord et avant tout par le web et les réseaux sociaux. Ainsi, en 2011, les Anonymous, suite à leur appel à boycotter Paypal, lancé sur leur compte Twitter, avaient annoncé au bout d’une journée, neuf mille désinscriptions de comptes Paypal. La société eBay, maison mère de Paypal, dévissa en bourse et perdit un milliard de dollars en une heure de cotation à Wall Street.

[85] L’alternative au produit boycotté doit être de qualité équivalente, disponible en quantité suffisante et identifiable.

[86] Sur ce thème, cf. notamment Alain de Benoist, « Du lien social » in Critiques – Théoriques, L’Age d’Homme, 2002, p.196-214.

[87] Konrad Pedziwiatr, « L’activisme social des nouvelles élites musulmanes de Grande-Bretagne », Hermès, La Revue, 2008/2, CNRS éditions, (n°51), p.125-133. L’auteur y décrit les activités d’une association basée à Londres, The City Circle, qui, notamment, met en œuvre des projets de nature éducative (tutorat, école du samedi, conseils d’orientation professionnelle, techniques d’entretien…) et organise des réunions hebdomadaires visant à discuter des questions touchant à la population musulmane.

[88] Emilio Gentile, op.cit., p.250-251.

[89] Eric Hobsbawn, « The Cult of Identity Politics » in New Left Review, n°217, 1996, p.40, cité par Zygmunt Bauman, in « Identité et mondialisation », Lignes 2001/3 (n° 6), p.10-27.

[90] Mark Granovetter, « The Strength of Weak Ties », American Journal of Sociology, Volume 78, Mai 1973, p.1360-1380.

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

In English-speaking states at least, there is a muddled dichotomy in regard to the Left and Right, particularly among media pundits and academics. What is often termed “New Right” or “Right” there is the reanimation of Whig-Liberalism. If the English wanted to rescue genuine conservatism from the free-trade aberration and return to their origins, they could do no better than to consult the early twentieth-century philosopher Anthony Ludovici, who succinctly defined the historical dichotomy rather than the commonality between Toryism and Whig-Liberalism, when discussing the health and vigor of the rural population in contrast to the urban:

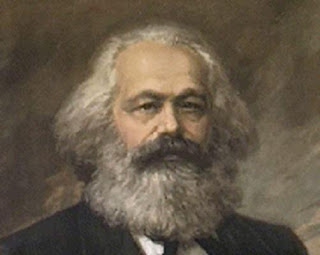

In English-speaking states at least, there is a muddled dichotomy in regard to the Left and Right, particularly among media pundits and academics. What is often termed “New Right” or “Right” there is the reanimation of Whig-Liberalism. If the English wanted to rescue genuine conservatism from the free-trade aberration and return to their origins, they could do no better than to consult the early twentieth-century philosopher Anthony Ludovici, who succinctly defined the historical dichotomy rather than the commonality between Toryism and Whig-Liberalism, when discussing the health and vigor of the rural population in contrast to the urban: Spengler, one of the seminal philosopher-historians of the “Conservative Revolutionary” movement that arose in Germany in the aftermath of the First World War, was intrinsically anti-capitalist. He and others saw in capitalism and the rise of the bourgeoisie the agency of destruction of the foundations of traditional order, as did Marx. The essential difference is that the Marxists regarded it as part of a historical progression, whereas the revolutionary conservatives regarded it as a symptom of decline. Of course, since academe is dominated by mediocrity and cockeyed theories, this viewpoint is not widely understood in (mis)educated circles.

Spengler, one of the seminal philosopher-historians of the “Conservative Revolutionary” movement that arose in Germany in the aftermath of the First World War, was intrinsically anti-capitalist. He and others saw in capitalism and the rise of the bourgeoisie the agency of destruction of the foundations of traditional order, as did Marx. The essential difference is that the Marxists regarded it as part of a historical progression, whereas the revolutionary conservatives regarded it as a symptom of decline. Of course, since academe is dominated by mediocrity and cockeyed theories, this viewpoint is not widely understood in (mis)educated circles. Not only is our century superior to any that have gone before it but . . . it may be best compared with the whole preceding historical period. It must therefore be held to constitute the beginning of a new era of human progress. . . . We men of the 19th Century have not been slow to praise it. The wise and the foolish, the learned and the unlearned, the poet and the pressman, the rich and the poor, alike swell the chorus of admiration for the marvellous inventions and discoveries of our own age, and especially for those innumerable applications of science which now form part of our daily life, and which remind us every hour or our immense superiority over our comparatively ignorant forefathers.[21]

Not only is our century superior to any that have gone before it but . . . it may be best compared with the whole preceding historical period. It must therefore be held to constitute the beginning of a new era of human progress. . . . We men of the 19th Century have not been slow to praise it. The wise and the foolish, the learned and the unlearned, the poet and the pressman, the rich and the poor, alike swell the chorus of admiration for the marvellous inventions and discoveries of our own age, and especially for those innumerable applications of science which now form part of our daily life, and which remind us every hour or our immense superiority over our comparatively ignorant forefathers.[21] Marx accurately describes the destruction of traditional society as intrinsic to capitalism, and goes on to describe what we today call “globalization.” Those who advocate free trade while calling themselves conservatives might like to consider why Marx supported free trade and described it as both “destructive” and as “revolutionary.” Marx saw it as the necessary ingredient of the dialectic process that is imposing universal standardization; this is likewise precisely the aim of Communism.

Marx accurately describes the destruction of traditional society as intrinsic to capitalism, and goes on to describe what we today call “globalization.” Those who advocate free trade while calling themselves conservatives might like to consider why Marx supported free trade and described it as both “destructive” and as “revolutionary.” Marx saw it as the necessary ingredient of the dialectic process that is imposing universal standardization; this is likewise precisely the aim of Communism.