Editor’s Note:

The following is roughly the first 40% of “The Eviction of the Yeomen,” chapter 9 of Brooks Adams’ The Law of Civilization and Decay.

Reading Adams’ account of the forces that ultimately created the British empire and diaspora, it is hard to regard it as a glorious and civilizing process, but rather as a sordid and savage one, given that the conquest and settling of new lands, the extermination, enslavement, and dispossession of non-whites, and even the despoiling of nature and the extinction of entire species, appear to be mere extensions of the rise of capitalism in England on the ruins of a fundamentally more humane political order.

None of this implies, of course, that the heirs of these upheavals should surrender our lands and go home. Past wrongs cannot be redressed, and in any case, our primary focus should be on building a just social order for the future. And for that task, Brooks Adams offers us much food for thought.

The remainder of chapter 9 deals with the Church of England. It throws a great deal of light on the prevalence of religious cynicism and insincerity in the Angl0 cultural sphere. I will reprint it on another occasion.

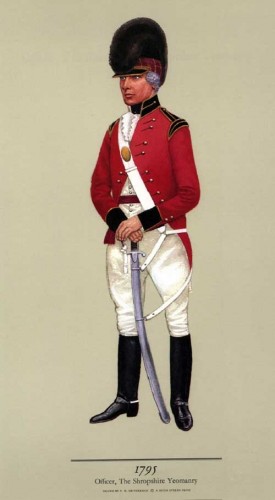

Like primitive Rome, England, during the Middle Ages, had an unusually homogeneous population of farmers, who made a remarkable infantry. Not that the cavalry was defective; on the contrary, from top to bottom of society, every man was a soldier, and the aristocracy had excellent fighting qualities. Many of the kings, like Coeur-de-Lion, Edward III, and Henry V, ranked among the ablest commanders of their day; the Black Prince has always been a hero of chivalry; and earls and barons could be named by the score who were famous in the Hundred Years’ War.

Like primitive Rome, England, during the Middle Ages, had an unusually homogeneous population of farmers, who made a remarkable infantry. Not that the cavalry was defective; on the contrary, from top to bottom of society, every man was a soldier, and the aristocracy had excellent fighting qualities. Many of the kings, like Coeur-de-Lion, Edward III, and Henry V, ranked among the ablest commanders of their day; the Black Prince has always been a hero of chivalry; and earls and barons could be named by the score who were famous in the Hundred Years’ War.

Yet, although the English knights were a martial body, there is nothing to show that, on the whole, they surpassed the French. The English infantry won Crecy and Poitiers, and this infantry, which was long the terror of Europe, was recruited from among the small farmers who flourished in Great Britain until they were exterminated by the advance of civilization.

As long as the individual could at all withstand the attack of the centralized mass of society, England remained a hot-bed for breeding this species of man. A medieval king had no means of collecting a regular revenue by taxation; he was only the chief of the free-men, and his estates were supposed to suffice for his expenditure. The revenue the land yielded consisted of men, not money, and to obtain men, the sovereign granted his domains to his nearest friends, who, in their turn, cut their manors into as many farms as possible, and each farmer paid his rent with his body.

A baron’s strength lay in the band of spears which followed his banner, and therefore he subdivided his acres as much as possible, having no great need of money. Himself a farmer, he cultivated enough of his fief to supply his wants, to provide his table, and to furnish his castle, but, beyond this, all he kept to himself was loss. Under such a system money contracts played a small part, and economic competition was unknown.

The tenants were free-men, whose estates passed from father to son by a fixed tenure; no one could underbid them with their landlord, and no capitalist could ruin them by depressing wages, for the serfs formed the basis of society, and these serfs were likewise land-owners. In theory, the villains may have held at will; but in fact they were probably the descendants, or at least the representatives, of the coloni of the Empire, and a base tenure could be proved by the roll of the manorial court. Thus even the weakest were protected by custom, and there was no competition in the labor market.

The manor was the social unit, and, as the country was sparsely settled, waste spaces divided the manors from each other, and these wastes came to be considered as commons appurtenant to the domain in which the tenants of the manor had vested rights. The extent of these rights varied from generation to generation, but substantially they amounted to a privilege of pasture, fuel, or the like; aids which, though unimportant to large property owners, were vital when the margin of income was narrow.

During the old imaginative age, before centralization gathered headway, little inducement existed to pilfer these domains, since there was room in plenty, and the population increased slowly, if at all. The moment the form of competition changed, these conditions were reversed. Precisely when a money rent became a more potent force than armed men may be hard to determine, but certainly that time had come when Henry VIII mounted the throne, for then capitalistic farming was on the increase, and speculation in real estate already caused sharp distress. At that time the establishment of a police had destroyed the value of the retainer, and competitive rents had generally supplanted military tenures. Instead of tending to subdivide, as in an age of decentralization, land consolidated in the hands of the economically strong, and capitalists systematically enlarged their estates by enclosing the commons, and depriving the yeomen of their immemorial rights.

The sixteenth-century landlords were a type quite distinct from the ancient feudal gentry. As a class they were gifted with the economic, and not with the martial instinct, and they throve on competition. Their strength lay in their power of absorbing the property of their weaker neighbors under the protection of an overpowering police.

Everything tended to accelerate consolidation, especially the rise in the value of money. While, even with the debasement of the coin, the price of cereals did not advance, the growth of manufactures had caused wool to double in value. “We need not therefore be surprised at finding that the temptation to sheep-farming was almost irresistible, and that statute after statute failed to arrest the tendency.”[1]

The conversion of arable land into pasture led, of course, to wholesale eviction, and by 1515 the suffering had become so acute that details were given in acts of Parliament. Places where two hundred persons had lived, by growing corn and grain, were left desolate, the houses had decayed, and the churches fallen into ruin.[2]The language of these statutes proves that the descriptions of contemporaries were not exaggerated.

For I myself know many towns and villages sore decayed, for it whereas in times past there war in some town an hundred households there remain not now thirty; in some fifty, there are not now ten; yea (which is more to be lamented) I know towns so wholly decayed, that there is neither stick nor stone standing as they use to say.

Where many men had good livings, and maintained hospitality, able at times to help the king in his wars, and to sustain other charges, able also to help their pore neighbors, and virtuously to bring up their children in Godly letters and good sciences, now sheep and conies devour altogether, no man inhabiting the aforesaid places. Those beasts which were created of God for the nourishment of man do now devour man. . . . And the cause of all this wretchedness and beggary in the common weal are the greedy Gentlemen, which are sheepmongers and grazers. While they study for their own private commodity, the common weal is like to decay. Since they began to be sheep masters and feeders of cattle, we neither had victual nor cloth of any reasonable price. No meruayle, for these forestallers of the market, as they use to say, have gotten all things so into their hands, that the poor man must either buy it at their price, or else miserably starve for hunger, and wretchedly die for cold.[3]

The reduction of the acreage in tillage must have lessened the crop of the cereals, and accounts for their slight rise in value during the second quarter of the sixteenth century. Nevertheless this rise gave the farmer no relief, as, under competition, rents advanced faster than prices, and in the generation which reformed the Church, the misery of yeomen had become extreme. In 1549 Latimer preached a sermon, which contains a passage often quoted, but always interesting:

Furthermore, if the king’s honor, as some men say, standeth in the great multitude of people; then these grazers, inclosers, and rent-rearers, are hinderers of the king’s honor. For where as have been a great many householders and inhabitants, there is now but a shepherd and his dog. . . .

My father was yeoman, and had no lands of his own, only he had a farm of three or four pound by year at the uttermost, and hereupon he tilled so much as kept half a dozen men. He had walk for a hundred sheep; and my mother milked thirty kine. He was able, and did find the king a harness, with himself and his horse, while he came to the place that he should receive the king’s wages. I can remember that I buckled his harness when he went unto Blackheath field. He kept me to school, or else I had not been able to have preached before the king’s majesty now.

He married my sisters with five pound, or twenty nobles apiece; so that he brought them up in godliness and fear of God. He kept hospitality for his poor neighbors, and some alms he gave to the poor. And all this he did of the said farm, where he that now hath it payeth sixteen pound by year, or more, and is not able to do anything for his prince, for himself, nor for his children, or give a cup of drink to the poor.[4]

The small proprietor suffered doubly: he had to meet the competition of large estates, and to endure the curtailment of his resources through the enclosure of the commons. The effect was to pauperize the yeomanry and lesser gentry, and before the Reformation the homeless poor had so multiplied that, in 1530, Parliament passed the first of a series of vagrant acts.[5]

At the outset the remedy applied was comparatively mild, for able-bodied mendicants were only to be whipped until they were bloody, returned to their domicile, and there whipped until they put themselves to labor. As no labor was supplied, the legislation failed, and in 1537 the emptying of the convents brought matters to a climax. Meanwhile Parliament tried the experiment of killing off the unemployed; by the second act vagrants were first mutilated and then hanged as felons.[6]

At the outset the remedy applied was comparatively mild, for able-bodied mendicants were only to be whipped until they were bloody, returned to their domicile, and there whipped until they put themselves to labor. As no labor was supplied, the legislation failed, and in 1537 the emptying of the convents brought matters to a climax. Meanwhile Parliament tried the experiment of killing off the unemployed; by the second act vagrants were first mutilated and then hanged as felons.[6]

In 1547, when Edward VI was crowned, the great crisis had reached its height. The silver of Potosi had not yet brought relief, the currency was in chaos, labor was disorganized, and the nation seethed with the discontent which broke out two years later in rebellion. The land-owners held absolute power, and before they yielded to the burden of feeding the starving, they seriously addressed themselves to the task of extermination. The preamble of the third act stated that, in spite of the “great travel” and “godly statutes” of Parliament, pauperism had not diminished, therefore any vagrant brought before two justices was to be adjudged the slave of his captor for two years. He might be compelled to work by beating, chaining, or otherwise, be fed on bread and water, or refuse meat, and confined by a ring of iron about his neck, arms or legs. For his first attempt at escape, his slavery became perpetual, for his second, he was hanged.[7]

Even as late as 1591, in the midst of the great expansion which brought prosperity to all Europe, and when the monks and nuns, cast adrift by the suppression of the convents, must have mostly died, beggars so swarmed that at the funeral of the Earl of Shrewsbury:

there were by the report of such as served the dole unto them, the number of 8000. And they thought that there were almost as many more that could not be served, through their unruliness. Yea, the press was so great that divers were slain and many hurt. And further it is reported of credible persons, that well estimated the number of all the said beggars, that they thought there were about 20,000.

It was conjectured “that all the said poor people were abiding and dwelling within thirty miles’ compass of Sheffield.”[8]

In 1549, just as the tide turned, insurrection blazed out all over England. In the west a pitched battle was fought between the peasantry and foreign mercenaries, and Exeter was relieved only after a long siege. In Norfolk the yeomen, led by one Kett, controlled a large district for a considerable time. They arrested the unpopular landlords, threw open the commons they had appropriated, and ransacked the manor houses to pay indemnities to evicted farmers. When attacked, they fought stubbornly, and stormed Norwich twice.

Strype described “these mutineers” as “certain poor men that sought to have their commons again, by force and power taken from them; and that a regulation be made according to law of arable lands turned into pasture.”[9]

Cranmer understood the situation perfectly, and though a consummate courtier, and himself a creation of the capitalistic revolution, spoke in this way of his patrons:

And they complain much of rich men and gentlemen, saying, that they take the commons from the poor, that they raise the prices of all manner of things, that they rule the poverty, and oppress them at their pleasure. . . .

And although here I seem only to speak against these unlawful assemblers, yet I cannot allow those, but I must needs threaten everlasting damnation unto them, whether they be gentlemen or whatsoever they be, which never cease to purchase and join house to house, and land to land, as though they alone ought to possess and inhabit the earth.[10]

Revolt against the pressure of this unrestricted economic competition took the form of Puritanism, of resistance to the religious organization controlled by capital, and even in Cranmer’s time, the attitude of the descendants of the men who formed the line at Poitiers and Crecy was so ominous that Anglican bishops took alarm.

It is reported that there be many among these unlawful assemblies that pretend knowledge of the gospel, and will needs be called gospellers. . . . But now I will go further to speak somewhat of the great hatred which divers of these seditious persons do bear against the gentlemen; which hatred in many is so outrageous, that they desire nothing more than the spoil, ruin, and destruction of them that be rich and wealthy.[11]

Somerset, who owed his elevation to the accident of being the brother of Jane Seymour, proved unequal to the crisis of 1549, and was supplanted by John Dudley, now better remembered as Duke of Northumberland. Dudley was the strongest member of the new aristocracy. His father, Edmund Dudley, had been the celebrated lawyer who rose to eminence as the extortioner of Henry VII, and whom Henry VIII executed, as an act of popularity, on his accession. John, beside inheriting his father’s financial ability, had a certain aptitude for war, and undoubted courage; accordingly he rose rapidly. He and Cromwell understood each other; he flattered Cromwell, and Cromwell lent him money.[12]

Strype has intimated that Dudley had strong motives for resisting the restoration of the commons.[13]

In 1547 he was created Earl of Warwick, and in 1549 suppressed Rett’s rebellion. This military success brought him to the head of the State; he thrust Somerset aside, and took the title of Duke of Northumberland. His son was equally distinguished. He became the favorite of Queen Elizabeth, who created him Earl of Leicester; but, though an expert courtier, he was one of the most incompetent generals whom even the Tudor landed aristocracy ever put in the field.

The disturbances of the reign of Edward VI did not ripen into revolution, probably because of the relief given by rising prices after 1550; but, though they fell short of actual civil war, they were sufficiently formidable to terrify the aristocracy into abandoning their policy of killing off the surplus population. In 1552 the first statute was passed looking toward the systematic relief of paupers.[14] Small farmers prospered greatly after 1660, for prices rose strongly, very much more strongly than rents; nor was it until after the beginning of the seventeenth century, when rents again began to advance, that the yeomanry once more grew restive. Cromwell raised his Ironsides from among the great-grandchildren of the men who stormed Norwich with Kett.

I had a very worthy friend then; and he was a very noble person, and I know his memory is very grateful to all—Mr. John Hampden. At my first going out into this engagement, I saw our men were beaten at every hand. I did indeed; and desired him that he would make some additions to my Lord Essex’s army, of some new regiments; and I told him I would be serviceable to him in bringing such men in as I thought had a spirit that would do something in the work. This is very true that I tell you; God knows I lie not. “Your troops,” said I, “are most of them old decayed serving-men, and tapsters, and such kind of fellows; and,” said I, “their troops are gentlemen’s sons, younger sons and persons of quality: do you think that the spirits of such base and mean fellows will ever be able to encounter gentlemen, that have honor and courage and resolution in them?” . . . Truly I did tell him; “You must get men of a spirit: . . . a spirit that is likely to go on as far as gentlemen will go; — or else you will be beaten still. . . .”

He was a wise and worthy person; and he did think that I talked a good notion, but an impracticable one. Truly I told him I could do somewhat in it, . . . and truly I must needs say this to you, . . . I raised such men as had the fear of God before them, as made some conscience of what they did; and from that day forward, I must say to you, they were never beaten, and wherever they were engaged against the enemy, they beat continually.[15]

Thus, by degrees, the pressure of intensifying centralization split the old homogeneous population of England into classes, graduated according to their economic capacity. Those without the necessary instinct sank into agricultural day laborers, whose lot, on the whole, has probably been somewhat worse than that of ordinary slaves. The gifted, like the Howards, the Dudleys, the Cecils, and the Boleyns, rose to be rich nobles and masters of the State. Between the two accumulated a mass of bold and needy adventurers, who were destined finally not only to dominate England, but to shape the destinies of the world.

One section of these, the shrewder and less venturesome, gravitated to the towns, and grew rich as merchants, like the founder of the Osborn family, whose descendant became Duke of Leeds; or like the celebrated Josiah Child, who, in the reign of William III, controlled the whole eastern trade of the kingdom. The less astute and the more martial took to the sea, and as slavers, pirates, and conquerors, built up England’s colonial empire, and established her maritime supremacy. Of this class were Drake and Blake, Hawkins, Raleigh, and Clive.

For several hundred years after the Norman conquest Englishmen showed little taste for the ocean, probably because sufficient outlet for their energies existed on land. In the Middle Ages the commerce of the island was mostly engrossed by the Merchants of the Steelyard, an offshoot of the Hanseatic league; while the great explorers of the fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries were usually Italians or Portuguese; men like Columbus, Vespucius, Vasco-da-Gama, or Magellan. This state of things lasted, however, only until economic competition began to ruin the small farmers, and then the hardiest and boldest race of Europe were cast adrift, and forced to seek their fortunes in strange lands.

For the soldier or the adventurer, there was no opening in England after the battle of Flodden. A peaceful and inert bourgeoisie more and more supplanted the ancient martial baronage; their representatives shrank from campaigns like those of Richard I, the Edwards, and Henry V, and therefore, for the evicted farmer, there was nothing but the far-off continents of America and Asia, and to these he directed his steps.

The lives of the admirals tell the tale on every page. Drake’s history is now known. His family belonged to the lesser Devon gentry, but fallen so low that his father gladly apprenticed him as ship’s boy on a channel coaster, a life of almost intolerable hardship. From this humble beginning he fought his way, by dint of courage and genius, to be one of England’s three greatest seamen; and Blake and Nelson, the other two, were of the same blood.

Sir Humphrey Gilbert was of the same West Country stock as Drake; Frobisher was a poor Yorkshire man, and Sir Walter Raleigh came from a ruined house. No less than five knightly branches of Raleigh’s family once throve together in the western counties; but disaster came with the Tudors, and Walter’s father fell into trouble through his Puritanism. Walter himself early had to face the world, and carved out his fortune with his sword. He served in France in the religious wars; afterward, perhaps, in Flanders; then, through Gilbert, he obtained a commission in Ireland, but finally drifted to Elizabeth’s court, where he took to buccaneering and conceived the idea of colonizing America.

A profound gulf separated these adventurers from the landed capitalists, for they were of an extreme martial type; a type hated and feared by the nobility. With the exception of the years of the Commonwealth, the landlords controlled England from the Reformation to the revolution of 1688, a period of one hundred and fifty years, and, during that long interval, there is little risk in asserting that the aristocracy did not produce a single soldier or sailor of more than average capacity. The difference between the royal and the parliamentary armies was as great as though they had been recruited from different races. Charles had not a single officer of merit, while it is doubtful if any force has ever been better led than the troops organized by Cromwell.

Men like Drake, Blake, and Cromwell were among the most terrible warriors of the world, and they were distrusted and feared by an oligarchy which felt instinctively its inferiority in arms. Therefore, in Elizabeth’s reign, politicians like the Cecils took care that the great seamen should have no voice in public affairs. And though these men defeated the Armada, and though England owed more to them than to all the rest of her population put together, not one reached the peerage, or was treated with confidence and esteem. Drake’s fate shows what awaited them. Like all his class, Drake was hot for war with Spain, and from time to time he was unchained, when fighting could not be averted; but his policy was rejected, his operations more nearly resembled those of a pirate than of an admiral, and when he died, he died in something like disgrace.

The aristocracy even made the false position in which they placed their sailors a source of profit, for they forced them to buy pardon for their victories by surrendering the treasure they had won with their blood. Fortescue actually had to interfere to defend Raleigh and Hawkins from Elizabeth’s rapacity. In 1592 Borough sailed in command of a squadron fitted out by the two latter, with some contribution from the queen and the city of London. Borough captured the carack, the Madre-de-Dios, whose pepper alone Burleigh estimated at £102,000. The cargo proved worth £141,000, and of this Elizabeth’s share, according to the rule of distribution in use, amounted to one-tenth, or £14,000. She demanded £80,000, and allowed Raleigh and Hawkins, who had spent £34,000, only £36,000. Raleigh bitterly contrasted the difference made between himself a soldier, and a peer, or a London speculator:

I was the cause that all this came to the Queen, and that the King of Spain spent 300,000li the last year. . . . I that adventured all my estate, lose of my principal. . . . I took all the care and pains; . . . they only sate still . . . for which double is given to them, and less then mine own to me.[16]

Raleigh was so brave he could not comprehend that his talent was his peril. He fancied his capacity for war would bring him fame and fortune, and it led him to the block. While Elizabeth lived, the admiration of the woman for the hero probably saved him, but he never even entered the Privy Council, and of real power he had none. The sovereign the oligarchy chose was James, and James imprisoned and then slew him. Nor was Raleigh’s fate peculiar, for, through timidity, the Cavaliers conceived an almost equal hate of many soldiers. They dug up the bones of Cromwell, they tried to murder William III, and they dragged down Marlborough in the midst of victory. Such were the new classes into which economic competition divided the people of England during the sixteenth century, and the Reformation was only one among many of the effects of this profound social revolution.

[. . .]

Although the spoliations of Edward [VI] are less well remembered than those of his father [Henry VIII], they were hardly less drastic. They began with the estates of the chantries and guilds, and rapidly extended to all sorts of property. In the Middle Ages, one of the chief sources of revenue of the sacred class had been their prayers for souls in purgatory, and all large churches contained chapels, many of them richly endowed, for the perpetual celebration of masses for the dead; in England and Wales more than a thousand such chapels existed, whose revenues were often very valuable. These were the chantries, which vanished with the imaginative age which created them, and the guilds shared the same fate.

Before economic competition had divided men into classes according to their financial capacity, all craftsmen possessed capital, as all agriculturists held land. The guild established the craftsman’s social status; as a member of a trade corporation he was governed by regulations fixing the number of hands he might employ, the amount of goods he might produce, and the quality of his workmanship; on the other hand, the guild regulated the market, and ensured a demand. Tradesmen, perhaps, did not easily grow rich, but they as seldom became poor.

With centralization life changed. Competition sifted the strong from the weak; the former waxed wealthy, and hired hands at wages, the latter lost all but the ability to labor; and, when the corporate body of producers had thus disintegrated, nothing stood between the common property and the men who controlled the engine of the law. By he 1 Edward VI., c. 14, all the possessions of the schools, colleges, and guilds of England, except the colleges of Oxford and Cambridge and the guilds of London, were conveyed to the king, and the distribution thus begun extended far and wide, and has been forcibly described by Mr. Blunt:

They tore off the lead from the roofs, and wrenched out the brasses from the floors. The books they despoiled of their costly covers, and then sold them for waste paper. The gold and silver plate they melted down with copper and lead, to make a coinage so shamefully debased as was never known before or since in England. The vestments of altars and priests they turned into table-covers, carpets, and hangings, when not very costly; and when worth more money than usual, they sold them to foreigners, not caring who used them for “superstitious” purposes, but caring to make the best “bargains” they could of their spoil. Even the very surplices and altar linen would fetch something, and that too was seized by their covetous hands.[17]

These “covetous hands” were the privy councilors. Henry had not intended that any member of the board should have precedence, but the king’s body was not cold before Edward Seymour began an intrigue to make himself protector. To consolidate a party behind him, he opened his administration by distributing all the spoil he could lay hands on; and Mr. Froude estimated that “on a computation most favorable to the council, estates worth . . . in modern currency about five millions” of pounds, were “appropriated—I suppose I must not say stolen—and divided among themselves.”[18] At the head of this council stood Cranmer, who took his share without scruple. Probably Fronde’s estimate is far too low; for though Seymour, as Duke of Somerset, had, like Henry, to meet imperative claims which drained his purse, he yet built Somerset House, the most sumptuous palace of London.

Notes

1. Agriculture and Prices, iv. 64.

2. 6 Henry VIII., c. 5; 7 Henry VIII., c. i.

3. Jewel of Joy, Becon. Also England in the Reign of Henry VIII, Early Eng. Text Soc, Extra Ser., No. xxxii. p. 75.

4. First Sermon before Edward VI. Sermons of Bishop Latimer, ed. of Parker Soc., 100, 101.

5. 22 Henry VIII., c. 12.

6. 27 Henry VIII., c. 25.

7. Edward VI., c. 3.

8. Brit. Mus., Cole MS. xii. 41. Cited in Henry VIII. and the English Monasteries, Gasquet, ii. 514, note.

9. Eccl. Mem., ii. pt. i, 260.

10. Sermon on Rebellion, Cranmer, Miscellaneous Writings and Letters, 194–6.

11. Sermon on Rebellion, Cranmer, Miscellaneous Writings and Letters, 195, 196.

12. Cal. ix. No. 193.

13. Eccl. Mem., ii. pt. I, 152.

14. 5 and 6 Edw. VI., c. 2.

15. Cromwell’s Letters and Speeches, Carlyle, Speech XI.

16. Raleigh to Burleigh, Life of Sir Walter Raleigh, Edwards, ii. 76, letter xxxiv.

17. The Reformation of the Church of England, ii. 68.

18. History of England, v. 432.

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

There is no talk in this view of higher education about shared governance between faculty and administrators, nor of educating students as critical citizens rather than potential employees of Wal-Mart. There is no attempt to affirm faculty as scholars and public intellectuals who have both a measure of autonomy and power. Instead, faculty members are increasingly defined less as intellectuals than as technicians and grant writers. Students fare no better in this debased form of education and are treated either as consumers or as restless children in need of high-energy entertainment—as was made clear in the recent Penn State scandal. Nor is there any attempt to legitimate higher education as a fundamental sphere for creating the agents necessary for an aspiring democracy. This neoliberal corporatized model of higher education exhibits a deep disdain for critical ideals, public spheres, and practices that are not directly linked to market values, business culture, the economy, or the production of short term financial gains. In fact, the commitment to democracy is beleaguered, viewed less as a crucial educational investment than as a distraction that gets in the way of connecting knowledge and pedagogy to the production of material and human capital.

There is no talk in this view of higher education about shared governance between faculty and administrators, nor of educating students as critical citizens rather than potential employees of Wal-Mart. There is no attempt to affirm faculty as scholars and public intellectuals who have both a measure of autonomy and power. Instead, faculty members are increasingly defined less as intellectuals than as technicians and grant writers. Students fare no better in this debased form of education and are treated either as consumers or as restless children in need of high-energy entertainment—as was made clear in the recent Penn State scandal. Nor is there any attempt to legitimate higher education as a fundamental sphere for creating the agents necessary for an aspiring democracy. This neoliberal corporatized model of higher education exhibits a deep disdain for critical ideals, public spheres, and practices that are not directly linked to market values, business culture, the economy, or the production of short term financial gains. In fact, the commitment to democracy is beleaguered, viewed less as a crucial educational investment than as a distraction that gets in the way of connecting knowledge and pedagogy to the production of material and human capital. The view of higher education as a democratic public sphere committed to producing young people capable and willing to expand and deepen their sense of themselves, to think the “world” critically, “to imagine something other than their own well-being,” to serve the public good, and to struggle for a substantive democracy has been in a state of acute crisis for the last thirty years.

The view of higher education as a democratic public sphere committed to producing young people capable and willing to expand and deepen their sense of themselves, to think the “world” critically, “to imagine something other than their own well-being,” to serve the public good, and to struggle for a substantive democracy has been in a state of acute crisis for the last thirty years.

Le revenu de citoyenneté a été défendu par des hommes venus de la droite comme de la gauche. Il relève malheureusement d’idées floues et de beaucoup de confusion.

Le revenu de citoyenneté a été défendu par des hommes venus de la droite comme de la gauche. Il relève malheureusement d’idées floues et de beaucoup de confusion.

Like primitive Rome, England, during the Middle Ages, had an unusually homogeneous population of farmers, who made a remarkable infantry. Not that the cavalry was defective; on the contrary, from top to bottom of society, every man was a soldier, and the aristocracy had excellent fighting qualities. Many of the kings, like Coeur-de-Lion, Edward III, and Henry V, ranked among the ablest commanders of their day; the Black Prince has always been a hero of chivalry; and earls and barons could be named by the score who were famous in the Hundred Years’ War.

Like primitive Rome, England, during the Middle Ages, had an unusually homogeneous population of farmers, who made a remarkable infantry. Not that the cavalry was defective; on the contrary, from top to bottom of society, every man was a soldier, and the aristocracy had excellent fighting qualities. Many of the kings, like Coeur-de-Lion, Edward III, and Henry V, ranked among the ablest commanders of their day; the Black Prince has always been a hero of chivalry; and earls and barons could be named by the score who were famous in the Hundred Years’ War. At the outset the remedy applied was comparatively mild, for able-bodied mendicants were only to be whipped until they were bloody, returned to their domicile, and there whipped until they put themselves to labor. As no labor was supplied, the legislation failed, and in 1537 the emptying of the convents brought matters to a climax. Meanwhile Parliament tried the experiment of killing off the unemployed; by the second act vagrants were first mutilated and then hanged as felons.[6]

At the outset the remedy applied was comparatively mild, for able-bodied mendicants were only to be whipped until they were bloody, returned to their domicile, and there whipped until they put themselves to labor. As no labor was supplied, the legislation failed, and in 1537 the emptying of the convents brought matters to a climax. Meanwhile Parliament tried the experiment of killing off the unemployed; by the second act vagrants were first mutilated and then hanged as felons.[6]