Pierre Le Vigan:

Michel Maffesoli : La « faillite des élites » ou bien plutôt « les tribus contre le peuple »?

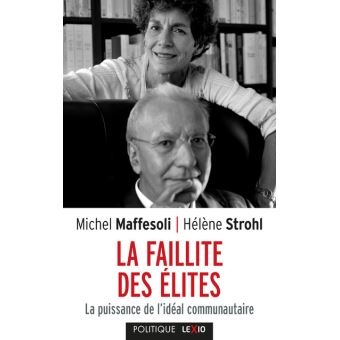

Politologue et sociologue, Michel Maffesoli décrypte depuis des décennies les mouvements profonds de notre société. Ses livres ne laissent pas indifférent. La violence totalitaire, L’ombre de Dionysos, La contemplation du monde, Le temps des tribus (1988), … tous ont marqué une étape et un approfondissement de ses thèmes. Ses constats n’échappent pas à la subjectivité dans laquelle est pris tout sociologue. Les conclusions qu’il en tire sont elles-mêmes tributaires de ses jugements de valeur. Son dernier livre, la faillite des élites, devrait une fois de plus faire l’objet de polémique. Il le mérite. Exploration de ses thèmes, et analyse critique.

Le thème principal de Michel Maffesoli est, depuis des années, le déclin de la modernité. C’est ce thème qu’il reprend avec Hélène Strohl dans La faillite des élites, sous-titré La puissance de l’idéal communautaire (Cerf, 2019). Le thème, c’est l’agonie de la modernité. C’en est fini de la démocratie parlementaire, du républicanisme civique, des syndicats, qui « se contentent de défendre des privilèges on ne peut plus dépassés » – privilèges qui, en passant, me paraissent une goutte d’eau par rapport aux privilèges des hommes du Capital, mais qui retiennent, sans originalité excessive, l’attention de Michel Maffesoli.

Selon le sociologue, ce sont toutes les catégories de la modernité qui s’effondrent : l’égalité, la raison, le progrès, les procédures formelles de validation du vrai. Et on devrait ajouter : la vérité elle-même, et la justice sociale, tout ce qui n’est pas vérifiable à hauteur d’une communauté forcément restreinte, puisque c’est celle d’affinités choisies, les affinités électives. On remarque que les catégories qui disparaissent ne se superposent pas toutes ; certaines sont même antagoniques. Les vertus civiques de la République, ce n’est pas tout à fait la même chose que la démocratie parlementaire, même si, sous la IIIe République, les deux choses se sont accommodées.

La technologie, nous dit Maffesoli, devient une technomagie, favorisant la cristallisation des émotions. A la vie de l’esprit succède « la vie de tout le corps » (Miguel de Unanumo). A une élite déconnectée du peuple succède la mise en cause de l’élite par le peuple – et on arrive ici au sens du titre du livre. Le peuple se rappelle soudain qu’il est l’instituant, et que l’Etat n’est que l’institué. Il est temps, pense le peuple, de remettre les choses à l’endroit. Bien sûr. Mais précisément, ce que furent les Gilets jaunes, c’est une demande de politique, et ce qu’ils mirent en pratique, c’est le dépassement des petites communautés (les artisans, les femmes seules au RSA, les autoentrepreneurs, etc) au profit d’un mouvement fédérateur des différences, et largement d’accord sur un point essentiel, et ce point est politique, qui est le référendum d’initiative populaire, qui est la revendication même d’un pouvoir populaire, c’est-à-dire d’un pouvoir arraché à l’oligarchie.

Résumons le constat de Michel Maffesoli, et d’Hélène Strohl : c’est la primauté de la vie sur le concept. La fin de la modernité, c’est de constater que la vie se débarrasse du concept, Le quod (le réel, la vie, le ‘’comment c’est’’) se débarrasse du quid (le concept, le ‘’ce que c’est’’). La modernité a dénié le sentiment d’appartenance. Elle a abouti à des « phénomènes communautaires paroxystiques et donc immaitrisables ». Il s’agit donc de montrer que « les communautés sont là », et que des élites aveugles ont tort de nier cette réalité ou de s’en inquiéter, ou de combattre ce phénomène. Tel est le thème du livre, et telle est sa thèse.

Qu’en penser ? Tout d’abord, le livre pose plusieurs problèmes de lecture. Ce ne sont pas des problèmes de style : il est souple, léger, et parfois précieux : « La socialité est la caractéristique de l’entièreté de l’être en commun » peut se dire plus simplement « l’être humain est un animal social ». Inutile d’être précieux quand la langue vulgaire permet d’exprimer une idée, un concept. Comme disait Diderot : « hâtons-nous de rendre la philosophie populaire ». Ce n’est pas brader la philosophie que de la rendre la plus accessible possible.

Un problème de lecture réside dans le choix de caractères d’imprimerie gris clairs, trop pâlichons. Mais le problème principal réside – on s’en doute – dans la construction même du livre. Les auteurs passent de jugements de fait à des jugements de valeur. Les jugements de fait sont censés être neutres (telle pomme est rouge). Les jugements de valeur ne le sont pas (telle pomme est meilleure qu’une autre). En outre, nous savons que les jugements de fait peuvent être présentés d’une manière non neutre. Exemple : un verre dit à moitié vide est le même que celui dit à moitié plein, mais la tonalité de l’expression n’est pas la même. Le passage d’un registre à l’autre est donc une difficulté du livre. Ce n’est pas la seule.

Il y a dans le livre plusieurs thèmes de niveaux différents. Il y a (1) une anthropologie. C’est celle qui affirme, à juste titre, que l’homme est un animal social, et même communautaire.

Il y a (2) une éthique, qui est qu’il faut s’accorder avec ce qui est. Cette éthique est ambigüe : il faut faire avec ce qui est, nous dit-on, certes, mais doit-on approuver pour autant tout ce qui est ? C’est aussi une éthique qui se veut une éthique de l’esthétique. On peut se demander si elle n’est pas plutôt une éthique de la jouissance (pourquoi pas ? Mais cela pose la question de la disparition du juste et du bien du domaine de l’éthique. Dany-Robert dufour a écrit des choses très pertinentes sur le lien entre capitalisme et idéologie de la jouissance gratuite).

Il y a (3) une vision du monde contemporain : le paradigme postmoderne (la communauté) aurait succédé au paradigme moderne (l’individu). Mais cette vision est-elle exacte ? Prend-t-elle en compte tout le réel ? Gilles Lipovetsky, qui n’est pas non plus un sociologue mineur, et Hervé Juvin, et bien d’autres observateurs ne souscrivent pas à cette analyse : ils estiment que notre société reste individualiste, sous des formes évidemment renouvelées depuis plusieurs décennies. Enfin (c’est le 4e point), les auteurs avancent une philosophie : « Les idées ne sont que la transcription des perceptions sensibles, des affects ressentis (…) » (p. 71). C’est la reprise des conceptions de David Hume. Nos auteurs auraient pu en dire plus sur cette épistémologie qu’ils font leur. Et qui est très aventurée et difficilement soutenable.

Les auteurs voient le monde contemporain comme un grand tournant et une grande libération : libération des concepts, libération de la raison, libération du cogito individuel. C’est la grande braderie des concepts. C’est aussi l’adieu à Kant. Le phénomène se débarrasse du noumène. La vie se débarrasse des théories sur la vie. Le réel se débarrasse des essences. Le sensualisme succède au rationalisme. Les catégories de la liberté et de l’égalité s’épuisent, au profit de liens choisis, et de valeurs choisies, ce qui pose un problème : nous reste-t-il, en tant que Français, quelque chose en commun ?

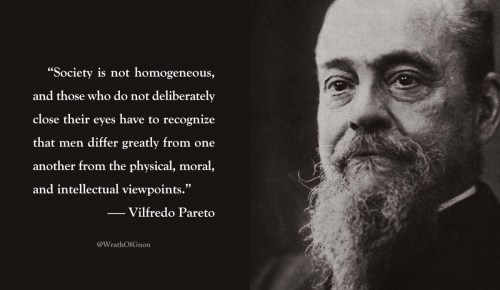

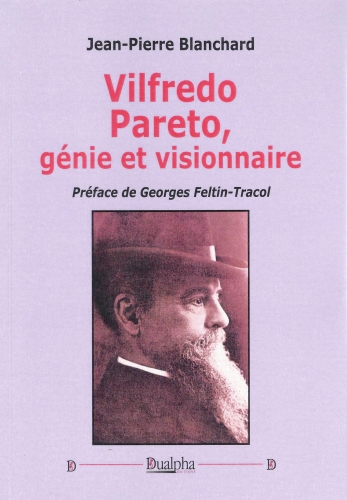

Point crucial : le peuple se débarrasse des élites. Ou il essaie. Il s’en débarrasse mentalement. Il les laisse tourner à vide. [Mais nos auteurs ne voient pas que l’on ne débarrasse pas si facilement des élites. Elles continuent de mettre en place leur société postnationale et liquide]. La réalité sociale foisonnante reprend conscience d’elle-même, et veut en finir avec les catégories d’ordre, de raison, de justice, qui descendent de l’Etat et des élites rationnelles vers le peuple. Un peuple assujetti devient enfin rebelle. Les instincts reprennent le pas sur la raison. La nature et la surnature (les mythes, l’imaginaire…) prennent le pas sur le culturel et le social normé (les lois, le respect des normes, la convenance…). Ce qui est archétypal (les résidus de Pareto) prendrait le pas sur ce qui rationnel (les dérivations de Pareto), sur ce qui s’objectivise, s’explique, se justifie, y compris les idéologies se piquant de logique. Les dérivations, qui sont les idéologies modernes, sont en train de mourir. L’anthropologie profonde de l’homme, communautaire, aventureuse, jouisseuse, prend sa revanche sur la raison, triste, mécanique, prévisible, travailleuse (trop travailleuse), sérieuse (trop sérieuse).

Le plaisir de l’être-ensemble prime sur le devoir-être du vivre-ensemble. Les liens choisis priment sur les liens imposés, sur les cohabitations forcées, sur les relations transactionnelles, celles qui reposent sur un contrat juridique. Au contrat social entre individus, succède le holisme. La socialité précède l’individu. Le feeling supplante le rationnel, et le calculé. L’homme retrouve sa dimension animale, trop oubliée. L’être humain se rappelle qu’il est un être-avec-autrui, un être en compagnie. Le contrat social explicite cède la place à un pacte implicite, qui est celui des affects.

Le pacte (postmoderne) est fondé sur le consensus, tandis que le contrat (moderne) est fondé sur le compromis. L’écrit cède la place à l’oral. Le contrat était tendu vers le long terme, le pacte concerne le court terme, le présent. Et il concerne la tribu, ici et maintenant. Le présent remplace le projet tout comme il remplace le progrès. Même la sexualité change : on s’accouple moins, on se lèche davantage.

Il serait toutefois raisonnable de ne pas en faire trop. Que les tribus libertines et clubs échangistes « participent à la cohésion sociale », comme l’affirment nos auteurs (p. 144), c’est tout de même beaucoup leur prêter. Par principe, il est très bien que chacun puisse vivre ce qu’il a envie de vivre entre adultes consentants. Mais de là à en faire une opération de salut public de la cohésion sociale, c’est certainement excessif. On aurait plutôt vu, dans ce rôle de facteur de cohésion sociale les retraités, souvent de milieu populaire, qui donnent gratuitement leur temps à des associations de soutien scolaire de quartiers HLM.

Le bonheur postmoderne continue d’être décliné par les auteurs : le commerce des biens, le commerce des idées et le commerce amoureux se rejoignent et se fondent en un seul ensemble. A son petit Moi, l’homme préfère le bain dans une communauté, le « Moi commun », le « moi transcendant » dont parle Novalis, c’est-à-dire le moi qui nous porte au-delà du moi, la communauté comme immersion entre pairs. « La perfection n’est pas dans un ‘’moi’’ tout puissant, mais dans un ‘’nous’’ ouvert, en constante évolution ». C’est la communauté comme élargissement du soi.

L’individu n’étant plus seul, il n’est plus assujetti à un principe unique, incarné par l’Etat. C’est ce qu’Alain Bihr a appelé « le crépuscule des Etats-nations ». A l’Etat providence, vertical, succède une solidarité horizontale : co-location, co-working, co-voiturage, etc. Tout cela réjouit Maffesoli. Ce sont bel et bien le retour à des partages horizontaux, choisis, parfois fraternels. Parfois. Car il y a des exclus de cet Eden communautaire. Le jardin des délices des uns peut être le jardin des supplices des autres. Et la jouissance des uns peut être cruelle, comme le rappelle Dany-Robert Dufour.

Les très pauvres, et en particulier les démunis en bagage culturel, ne bénéficient pas de tels outils, les co-ceci et autres uberisations plus ou moins marchandes, qui supposent maitrise de l’informatique, d’internet, de l’anglais basique. Ces coopérations horizontales entre pairs excluent, par principe, les non pairs, les isolés, et l’isolé n’est pas le cadre célibataire de centre-ville, c’est le retraité dans un village sans commerces, c’est le banlieusard d’un quartier difficile, c’est l’habitant de la cité Charles Hermitte à Paris, porte de la Chapelle, dans un quartier que tout le monde évite du fait de la présence de camps de migrants et de l’insécurité. La réduction de plus en plus nette des moyens de la politique sociale, et de l’Etat providence, qu’il serait plus juste d’appeler Etat protecteur (qui protège matériellement des accidents de la vie) laisse toute une part de la population, surtout française, sans aides, sans soutien, car, justement, tous n’ont pas accès aux solidarités horizontales, organiques. Les Français sont souvent plus désocialisés que les immigrés, dont la culture traditionnelle inclut une fratrie élargie, des solidarités de village, etc. Nous sommes plus désocialisés car plus modernes. Déclin de l’Etat protecteur : pourquoi ? Bien sûr parce que la priorité de nos sociétés est le profit de grands groupes. Mais pas uniquement. Cette réduction des moyens de la politique sociale, surtout par rapport à l’explosion de la précarité, vient de l’immigration, car c’est elle qui rend inépuisables les besoins sociaux. La poursuite de l’immigration, c’est forcément plus d’insécurité sociale pour les Français, et pour les immigrés les plus intégrés, c’est-à-dire ceux qui travaillent.

En ce sens l’Etat social, l’Etat protecteur a bien des défauts mais son principal défaut serait de ne pas exister, c’est-à-dire de laisser la place à la loi de la jungle de la société de marché. Et ce n’est qu’en recentrant cet Etat protecteur sur la base d’une préférence nationale, dissuasive de l’immigration, qu’il peut être sauvé, ainsi qu’en édictant des contreparties entre droits et devoirs.

Les auteurs de La faillite des élites, croyant faire un constat, disent des vérités, mais des vérités partielles, Ils avancent masqués. Ils ont un projet idéologique. C’est leur droit. Mais ce projet n’est pas affiché. Ils nous disent : à l’unité ontologique succède un pluralisme ontologique. « Tout coule. Rien n’est jamais à la même place. Mais le flot est incessant ». Pour être très concret, un pluralisme des valeurs succède à une unicité des valeurs, celles incarnées par la société et par l’Etat, garant de celle-ci. Une sorte de polythéisme vécu, pratique, reviendrait, sans doute dans le prolongement inconscient du christianisme médiéval et du culte pluriel des saints, tant il est vrai, comme disait Joseph de Maitre, que le christianisme – on comprend qu’il s’agit ici du catholicisme – est un « polythéisme raisonné ».

Pour Maffesoli, l’Etat français est fondamentalement unitaire. Il est « monothéiste ». Mais l’auteur se trompe. L’Etat est devenu communautariste. Il n’est plus une unité. Ne croyant plus en la France, l’Etat n’est plus que le garant d’une « société inclusive », c’est-à-dire une société dans laquelle chacun vient avec sa culture, ses croyances, sa foi mais n’envisage pas d’aller avec empathie vers le pays d’accueil, de marquer son affection (oui, il faut ici employer ce terme) envers la France et envers les Français. Ce pas vers la France, certains étrangers le font quand même encore, par exemple en donnant à leurs enfants un prénom français, mais ce pas est de moins en moins fréquent dans la mesure même où l’Etat, an nom du « respect des différences », ne fait rien pour l’encourager. D’où la panne de l’assimilation, devenue impossible quand la masse des étrangers est supérieure, dans beaucoup de quartiers, à la présence des Français de longue filiation, ceux qui constituaient encore, dans les années 1950, 95 % de la population, la France n’ayant jamais été depuis 1500 ans un pays de grande immigration.

La France devient ainsi une superposition hasardeuse de « tribus », un collage maladroit entre différentes communautés, qui s’ignorent, dans le meilleur des cas, ou s’agressent, dans le pire des cas. Finkielkraut a parlé de « balkanisation » de la France. Comment lui donner tort ? D’où une question : cette France rêvée par Michel Maffesoli, la France des tribus, n’est-ce pas une France déjà là ? Celle dans laquelle nous vivons ? N’est-ce pas la France actuelle ?

Maffesoli voit cette France qu’il dit « heureuse » et qui celle de « petite poussette » de Michel Serres, autre optimiste de principe. Dans cette France « débarrassée » des idéologies, des récits, des systèmes d’explication du monde, voire de transformation des sociétés, on aborde sans « préjugés », et plus encore sans recul, les faits du présent sans les hiérarchiser. On se laisse balloter par les émotions, et terrorisé par la marche du progrès. Car la postmodernité n’échappe pas au culte du progrès. Ceux qui pensent que « c’était mieux avant », au moins dans certains domaines, sont toujours ringardisés. « On n’est plus au Moyen-Age… »

Il y a ceux qui sont « en retard », « arriérés » et ceux qui sont « dans la vague », dans le mouvement. « Il faut avancer » : c’est la phrase qui réconcilie les modernes et les postmodernes. Les modernes voulaient avancer vers une société du travail, ou vers une société plus juste, les postmodernes veulent avancer dans la décontraction, l’esprit « cool ».

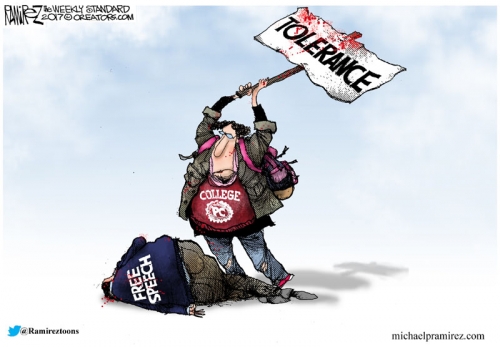

« Pas de prise de tête » est leur slogan. On passe du « dogmatisme doctrinal » à un pluralisme des opinions, nous dit Maffesoli. Ici, on s’interroge. Pluralisme ? Depuis plus de 50 ans, la liberté d’opinion n’a cessé d’être réduite par des lois, et tout autant par un journalisme-flic, dénonciateur, inquisiteur, qui somme untel de « s’expliquer », et de faire repentance pour une phrase trop spontanée, qui accuse un tel de n’être « pas clair » parce qu’il tient des propos nuancés sur des sujets où l’outrance est obligatoire, etc. Un trait d’humour à propos de l’obsession des violences sexistes amène Finkielkraut à devoir s’expliquer, lui aussi, à bien préciser que c’était de l’humour, un pas de côté pour parler avec un peu de distance de sujets « chauds ». Liberté d’opinion et d’expression à l’époque actuelle, en France ? C’est une plaisanterie que de croire cela.

L’homme et l’œuvre sont liés désormais dans une même réprobation. Doit-on interdire le visionnage des films de Polanski parce qu’il aurait abusé d’une jeune fille il y a quelques décennies ? Faut-il rééditer tout Céline ? Telles sont les questions qui sont « débattues ». Absurdité : car il n’est nul besoin de trouver l’homme Céline sympathique, pas plus que l’homme Matzneff, pour trouver leurs œuvres de qualité. Oui, le Taureau de Phalaris est un bon livre. Oui, en même temps, la complaisance vis-à-vis de la pédophilie est déplorable. Oui, lire Céline est nécessaire pour comprendre notre époque, oui, Céline était geignard, parfois odieux, et pas trés digne. Le talent n’excuse rien, c’est entendu, mais il faut toujours distinguer l’homme et l’œuvre.

Nous en sommes là, à l’heure de « l’envie de pénal » de tous contre tous, notre époque n’ayant pas peur du ridicule. On passe de la pensée qui descend des hauteurs universitaires au « gazouillement » des blogs et de twitter. Seulement, twitter, ce n’est tout de même pas du niveau des articles de Chateaubriand, ou de Maurras (qui détestait le premier du reste).

Bien entendu, il n’est pas interdit de relever quelques aspects positifs aux relations telles qu’elles se mettent en place dans le monde postmoderne. La notion d’empathie, ou d’intropathie (connaissance de moi-même en tant que je suis affecté par autrui), supplante celle d’intérêt. Un exemple particulièrement intéressant est celui des groupes de pairs. Ce sont des groupes d’entraide dans lesquels une ou plusieurs personnes étant passés par une problématique (alcool, drogue, autisme, dépression,…) et ayant trouvé des solutions aident les autres à cheminer dans le même sens de diminution d’une souffrance et/ou d’une dépendance pathologique. Ce peut être par exemple, des anciens alcooliques, des usagers de drogues engagés dans des pratiques de réduction des risques (de transmission de virus notamment), des anciens anorexiques, etc. C’est un exemple probant du passage de solidarités mécaniques (comme la redistribution sociale effectuée par l’Etat et les pouvoirs publics) à une solidarité organique (venant des gens eux-mêmes). Qu’il y ait chez l’homme des ressources émotionnelles (un « ordo amoris » dit Max Scheler) qui puissent à la fois l’ouvrir aux autres, et le mettre en correspondance avec un ordre divin, c’est une réalité. Mais elle ne peut suffire à assurer une solidarité entre tous, et à protéger les plus faibles, qui sont les plus désocialisés.

Maffesoli en conclut que le « prétendu individualisme » est un fake (un trucage). C’est un « fake à l’usage d’histrions déphasés ». A l’individualisme aurait succédé une autre époque, celle des identifications multiples. Les identifications multiples, plurielles ne sont pourtant pas une nouveauté. Chacun est célibataire ou en couple, a une fonction professionnelle (on ne dit plus « un métier », ni une profession), a tel engagement, a telle passion, tel passe-temps. Bref, un ingénieur n’est jamais qu’un ingénieur, ce peut être aussi un homme à femmes, ou un homosexuel, un communiste, ou un identitaire, un chasseur, un grand voyageur, un amateur de bons vins, un calme, un nerveux, un sanguin, tout ce que l’on voudra. En même temps. C’est une banalité : chacun a différentes facettes de sa personnalité.

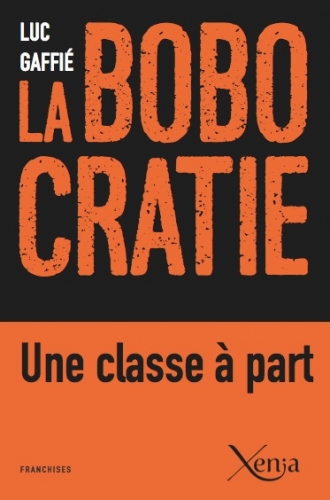

Le constat de Michel Maffesoli, c’est la grande migration des us et coutumes. Il s’en réjoui. Nous avons quitté les eaux de la modernité pour entrer dans celles de la postmodernité. En tout cas d’une certaine postmodernité, solidaire dans l’entre-soi, communautaire entre gens du même monde, décontractée, « tranquille » (chacun connait l’échange « Ca va ? Oui, Tranquille »), apaisée. C’est le temps des bobos [mais on sait qu’il y a une autre postmodernité, qui est celle des Gilets jaunes, qui est celle de la colère spontanée du peuple].

« Non, ce n’est plus l’individualisme qui prévaut » est le titre d’un chapitre du livre. Si c’est le principe qui fait l’histoire, comme le pensait Karl Marx, c’est donc, avec la postmodernité, le principe postmoderne, celui des liens horizontaux, qui fait une histoire postmoderne. C’est du reste l’unique point sur lequel Maffesoli donne raison à Marx.

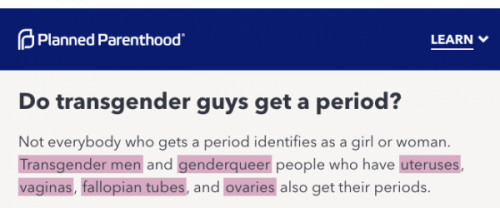

De fait, la fin de l’efficacité d’un principe marque son déclin. Et une époque est effectivement toujours déterminée par un principe, ou, mieux encore, un paradigme. De même, la fin d’une époque, c’est toujours la fin du principe qui l’a générée. Dans le monde postmoderne, ce qui est donné à la communauté est pris à l’individu. C’est la communauté qui devient la référence, l’individu, lui, est éclaté entre diverses identités. « Ne me demandez pas qui je suis et ne me dites pas de rester le même, c’est une morale d’Etat Civil, elle régit nos papiers », disait Michel Foucault (L’archéologie du savoir). Les identités sont de plus en plus multiples, elles deviennent floues et de plus en plus changeantes. Au-delà des identités, il y a des identifications, et il y a des « sincérités successives ». La conséquence de cela, c’est l’éclatement du moi. On passe du « je pense » cartésien au « je suis pensé » nietzschéen. C’est le motif de la pensée postmoderne connue aux Etats Unis sous le nom de French theory (qui était d’ailleurs moins une théorie qu’une mode intellectuelle).

Le bricolage des mythes remplace le mythe du progrès. L’idéologie du progrès, le scientisme, le positivisme avaient amené à l’éclipse des images mythiques au profit des croyances en la science, amenant à des connaissances claires, précises, chiffrées des phénomènes. Jacob Taubes, dans ses deux livres qui évoquent Carl Schmitt (En divergent accord et La théologie politique de Paul), a noté que le mythe, qui parle au corps a été remplacé par la croyance en la science, qui parle à la raison. Selon Maffesoli, un mouvement de balancier nous ramène vers le corps, nous reconduit vers les sens, vers ce qui est incarné, plus que vers ce qui est prouvé (scientifiquement). Le même mouvement qui nous éloigne des progressismes nous éloigne des messianismes (juif, chrétien, musulman). Aux messianismes qui nous font miroiter une vie future parfaite, succède une sagesse qui renoue avec l’antique, avec Epicure et Lucrèce, et avec la Stoia (le Portique, l’école des stoïciens), et qui consiste à faire avec ce qui est, et à s’accorder aux autres tels qu’ils sont, et avec soi-même tel que l’on est (ce qui est sans doute plus difficile).

Il s’agit non seulement d’accepter, mais d’avoir plaisir de vivre dans la « fédération bruissante » (Maurice Barrès) de la communauté des hommes. Il s’agit de réévaluer le quotidien. Les tribus urbaines remplacent l’homme seul dans la foule. Les techniques qui avaient désenchanté le monde le réenchantent, en créant des lieux symboliques via internet. Et des liens à la suite des lieux. Les cybertribus « développent des pratiques communautaires qui peuvent être rangées sous la rubrique de l’immoralisme éthique » (morale et éthique étant le même mot dans des langues différentes, l’expression de Maffesoli est tautologique).

« Le néo-tribalisme postmoderne pourrait permettre une coexistence des appartenances au sein d’un même individu […] », écrit Hélène Strohl. Il permettrait que l’individu ne soit pas assigné à une seule identité. Ce n’est pas douteux, mais ce n’est pas du tout nouveau. L’identité professionnelle, par exemple, s’est toujours superposée à d’autres identités, ou identifications, religieuse, sexuelles, artistiques, etc. Toute la théorie de Ricoeur sur l’identité idem et l’identité ipsé, réunies dans l’identité narrative, explique cela. Ce qui est frappant avec Maffesoli, c’est que les communautés sont toujours là pour permettre à l’individu de s’épanouir. Qu’un individu soit un faisceau d’identités (culturelles, professionnelles, sportives, amoureuses, etc), cela n’est pas douteux. Personne n’y voit d’inconvénient, à une condition toutefois : il y a aussi des conditions politiques à l’épanouissement de l’individu. Et c’est là le grand impensé de Maffesoli. Or, ce n’est pas simple d’éviter la question du politique. Le court terme, qui est le plaisir de l’individu, peut être en contradiction avec le long terme, qui est la préservation d’un cadre de civilisation, et de repères culturels commun à toute une société, à toute une nation, qui, par définition, est une construction à long terme. Et c’est bien là le problème auquel se heurte Maffesoli. Du moins auquel il devrait se heurter, en toute logique. Mais il ne s'y heurte pas car il l’esquive. Il l’esquive car il n’aime pas la logique, et parce qu’il n’est pas frontal, en bon postmoderne qu’il est.

La condition d’existence des communautés choisies, affectionnées par Maffesoli, c’est la pérennité d’un certain cadre civilisationnel. La juxtaposition des communautés, cela ne marche qu’un temps. Cela ne marche plus quand la communauté nationale cesse d’exister. Nos auteurs nous disent qu’il faut accepter la coexistence de plusieurs appartenances. On peut évidemment être un bon Français et être attaché à son village natal, qu’il soit européen ou extra-européen. Mais que se passe-t-il quand les appartenances se disputent un même individu ? Ou quand ces appartenances se hiérarchisent de la façon suivante : la France pour les droits sociaux et les avantages, la patrie d’origine pour les affections ? Que se passe-t-il quand l’appartenance à la France n’est mise en avant que pour les avantages sociaux, matériels, le droit au logement, la gratuité des soins, etc, et que le moindre événement sportif dit que les attachements ne vont jamais à la France, voire sont dressés contre elle ? Chacun sait que ces cas ne sont pas rares. Et ils sont tout le problème de l’immigration.

Maffesoli explique que le postmoderne est le retour du prémoderne. C’est effectivement vrai. C’est le retour à une situation anténationale, avant les Etats-nations. Or, être Français, c’est, qu’on le veuille ou non, appartenir à une nation. A une nation politique. Que celle-ci ait vocation à intégrer une « Europe indépendante », comme disait le général de Gaulle, par la création d’une confédération préservant un certain art de vivre, ce que l’on appelle une civilisation, cela ne fait, pour moi, pas de doute. Encore faut-il ne pas revenir au temps des tribus et des allégeances féodales. Si elles préparent un Empire, c’est toujours l’Empire des autres. C’est la domination de notre pays par un Empire étranger qu’elles préparent. Une domination pas forcément physique, mais qui pourrait bien être mentale. Et qui peut être celle dont il est le plus difficile de se libérer.

Le pluralisme ontologique, ou tout simplement ce que Max Weber appelait le « polythéisme des valeurs » amène à ce qu’il ne soit plus possible de croire au Progrès – qui est par définition unique, comme un train lancé sur une seule voie. Le contraire du progrès n’est évidemment pas la régression, ou la réaction, bien qu’il soit nécessaire et sain de réagir : la réaction à un médicament veut dire qu’il fait de l’effet. Reste à savoir si c’est le bon effet. Qu’est-ce que le Progrès ? Avec un grand P cela veut dire l’idéologie du progrès, et même la religion du progrès. Le contraire du Progrès, ce n’est donc pas la régression, c’est le sens des limites. Le contraire de l’idéologie du progrès, c’est de penser aussi aux dégâts du progrès, c’est de refuser la démesure (hubris). C’est le sentiment que le progrès ne peut être sans fin, qu’il ne peut être un mouvement vers toujours plus d’arraisonnement du monde, c’est préférer Alain Finkielkraut à Philippe Forget (et Alain de Benoist à Guillaume Faye). C’est se retrouver dans les idées de Jean-Paul Dollé plus que dans celles de Luc Ferry (au demeurant excellent pédagogue). C’est préférer Robert Redeker à Michel Serres (d’un optimisme déprimant), et Sylviane Agacinski à Frédéric Worms (que l’on préfère en spécialiste de Bergson plus qu’en spécialiste de la bioéthique). Or, ce qui est très caractéristique de Michel Maffesoli, c’est que, se réjouissant de ce qu’il croit être un abandon de l’idée de progrès, il n’entre pas dans les débats évoqués ci-dessus. Ce qu’il refuse de penser, c’est que c’était mieux avant, en tout cas dans certains domaines : l’éducation, la civilité, la sécurité, le prix des logements par rapport aux salaires, la qualité de vie sociale, même et surtout dans les quartiers populaires, le contrôle plus léger dans tous les actes de la vie, auquel a succédé un flicage généralisé, l’élitisme républicain qui vaut mieux que l’ascension sociale parce que l’on est issu « de la diversité » [ce qui veut dire en clair que l’on n’est pas d’origine française]. C’était mieux avant dans tout ce qui compte pour les classes populaires, celles qui ne peuvent se protéger de l’ensauvagement des quartiers de banlieues.

Renversant la charge des responsabilités, Maffesoli estime que « l’islamisme est relié à l’absence de bienveillance [des pouvoirs publics] envers les religions de communautés immigrés ». Etonnante remarque. N’a-t-il pas vu les affichages « bon ramadan », pour la rupture du jeune, sur les panneaux de Paris et d’autres grandes villes (et même une vidéo des joueurs du PSG !), ces grandes villes fiefs des « bobos », bastions du politiquement correct et de la pensée unique « diversitaire », et vivier de l’électoral Macron ? Ces grandes villes dont la plupart ne souhaitent à personne de « joyeuses Pâques ? Selon Maffesoli, il faut répondre à l’islamisme et aux autres extrémismes par… le relativisme, par exemple en leur laissant la possibilité de défiler. On croit rêver. Car s’il y a une différence entre l’islam et l’islamisme (je le crois, au sens où l’islamisme est un djihadisme), c’est bien que l’Islam est une religion et une civilisation (il faut alors mettre une majuscule : Islam), et si l’islamisme est autre chose, il est une volonté conquérante d’islamisation forcée. Nous savons cela. Il fut un temps où le christianisme aussi était expansionniste. Faut-il donc autoriser de telles manifestations islamistes ? Croit-on que cela ne nous mènerait pas tout droit à la guerre civile ? Nos sociétés ne sont-elles pas déjà excessivement relativistes ?

Exemple. Le respect de la possibilité de pratiquer sa religion est assuré en France, alors que ce respect n’a pas son équivalent dans les pays musulmans (être chrétien en pays musulman est souvent impossible), c’est déjà beaucoup, et c’est très bien comme cela. Nous acceptons une non réciprocité. C’est énorme. Et il faudrait aller encore plus loin, nous dit Maffesoli ? On rêve, ou on fait un cauchemar, car on sait comment se terminent les capitulations, par des capitulations encore plus grandes. Il serait encore mieux que notre tolérance soit comprise comme un acte de générosité, et non de faiblesse. Ce serait folie que d’aller au-delà. La générosité deviendrait asservissement et masochisme.

Maffesoli cite justement, en l’approuvant, Goethe (Le second Faust) « la frisson sacré est la meilleur part de l’humanité ». Il faut donc proposer du sacré, de la mystique, de l’engagement passionné, qui est tout le contraire du relativisme, de l’extrême tolérance que propose Maffesoli. On ne répond à un plein – et l’islamisme est un plein, et l’islam tout court aussi – que par un autre plein. Certainement pas par le vide des valeurs d’un laïcisme pitoyable, certainement pas par un patriotisme mou, certainement pas par des incantations à une République en oubliant de dire que la république est admirable quand c’est la République française, et que n’avons que faire d’une république de nulle part.

La fin de l’idée de progrès, c’est la fin de la Raison surplombante, et c’est la fin de la verticalité. Il s’agit désormais non pas de contracter avec l’autre (le contrat social), mais de le renifler, car si l’homme n’est pas qu’un animal, il est aussi un animal, affirment les auteurs. Bien sûr, personne de sensé ne dit le contraire. Du reste, c’est l’évacuation de l’animalité de l’homme qui a abouti à la bestialité (dans les camps de concentration), dit Maffesoli. Le point de vue est unilatéral. L’animalité est du côté du bien, la culture du côté du mal. Mais la nature de l’homme, c’est sa culture. Quant à l’animalité, elle est non pas du côté du bien, mais au-delà du bien et du mal.

La modernité était selon Maffesoli marquée par la verticalité, la postmodernité est marquée par l’horizontalité. La modernité connaissait les religions, la postmodernité connait le sacral. Ou le reconnait à nouveau, comme avec les prémodernes Mais que dit Maffesoli de la place croissante de l’islam en France ? Ce n’est pourtant du sacral, c’est une religion au sens classique, avec ses rites. Silence de l’auteur sur cette contradiction entre sa théorie et ce que nous voyons.

« L’assomption de l’individualisme était l’essentielle spécificité de l’époque moderne », et la montée des communautés serait le signe de l’entrée en postmodernité. Mais de quelles communautés parle-t-on ? M. Maffesoli et Mme Strohl ne les voient pas comme une façon de rétablir des continuités, des permanences. Ce sont des appartenances éphémères, et ce ne sont pas toujours des appartenances. « Les communautés soulignent l’importance du nomadisme comme structure anthropologique indépassable ». Le nomadisme « est une structure anthropologique retrouvant une vigueur nouvelle » dans les moments de décadence (p. 167). En haut, le nomadisme des traders, d’un hôtel international à un autre, en bas, le nomadisme des migrants, des « réfugiés », vrais ou faux, des « mineurs isolés » dont on conviendra qu’ils sont rarement isolés, et souvent moins mineurs qu’ils le disent.

Que le nomadisme soit le principal vecteur d’une communauté retrouvée laisse pour le moins dubitatif. Ce fut certes le cas au Sahara, avec les bédouins, ou dans les tribus mongoles. Cela fait tout de même un certain temps que, en Europe, les communautés se forment sur d’autres bases.

Dans le même temps, Maffesoli manifeste sa sympathie pour les Gilets Jaunes. Ceux-ci représentent une forme de retour du lien social. Des gens qui étaient isolés (mais comme nous vivons dans une époque postmoderne, nous avions cru comprendre à la lecture de Maffesoli que les isolés n’étaient que des faux isolés ?) retrouvent le plaisir du lien social. Les auteurs ont raison de saluer ce phénomène. Toutefois, on ne voit pas le lien entre ces nouvelles communautés que furent les Gilets Jaunes et le goût du nomadisme. Tout au contraire, les Gilets Jaunes témoignent du besoin de retrouver des repères, de ne plus se sentir étranger chez soi, de retrouver des stabilités et des ancrages. C’est tout le contraire du nomadisme qui caractérise les « bobos » urbains de centre-ville. Les communautés de Maffesoli sont des communions de circonstances. Les auteurs l’écrivent : « L’idéal communautaire est présentéiste ». Les solitaires « ne sont jamais isolés », croient savoir les auteurs (p. 154), car ils sont toujours en lien avec les autres, devant leur ordinateur, leur tablette, ou leur smartphone. Singulier optimisme. Combien de nos compatriotes vivent tristement de contacts virtuels déréalisants ? Ou d’une solitude complète. Combien de personnes agées que leurs enfants ne visitent jamais ? Au lieu de se pencher sur cette hypothèse comme quoi l’individu isolé serait toujours une réalité très répandue de nos sociétés, nos auteurs renvoient la critique de la vacuité de certains tribus à du ressentiment et à de la jalousie devant la « chaleur » du groupe. Eh bien oui, rollers, trottinettes et autres véhicules bizarres, aussi vite apparus que démodés, et encombrant les trottoirs, me paraissent participer du crétinisme à roulettes, dont la panoplie comporte généralement un casque, pour écouter sinon de la musique, du moins du « son ». De même, airbnb, blablacar et autres réseaux sociaux sont approuvés sans réserve par Maffesoli. Ils seraient une reliance. Ils « constituent la communion des saints postmoderne ». Rien que cela. On n’est pas obligé d’être convaincu par cette formule dont l’inattendu n’implique pas une quelconque justesse.

Certes, ces outils de partage de véhicules, ou de chambres, rendent à coup sûr bien des services, alliant l’intérêt financier à des contacts humains qui peuvent être sympathiques, bien que la plupart du temps, très superficiels. Mais nos auteurs oublient une caractéristique de tous ces réseaux. C’est la notation, ce sont les « étoiles » à affecter à chaque « partenaire », c’est la mise en ligne des « avis », ce sont les commentaires qui sont publics, etc. C’est la tyrannie de la transparence. Et alors que les auteurs critiquent les concours, ils font l’éloge des réseaux, qui impliquent un système de notation beaucoup plus inquisitorial que n’importe quel concours, une dictature de la transparence, intrusive, et plus injuste que n’importe quel concours. Les réseaux sociaux ? C’est le grand panoptique. Faire leur apologie ? C’est tuer l’intimité, la pudeur, le quant à soi. Au profit des ego, du tank à soi.

Certes, ces outils de partage de véhicules, ou de chambres, rendent à coup sûr bien des services, alliant l’intérêt financier à des contacts humains qui peuvent être sympathiques, bien que la plupart du temps, très superficiels. Mais nos auteurs oublient une caractéristique de tous ces réseaux. C’est la notation, ce sont les « étoiles » à affecter à chaque « partenaire », c’est la mise en ligne des « avis », ce sont les commentaires qui sont publics, etc. C’est la tyrannie de la transparence. Et alors que les auteurs critiquent les concours, ils font l’éloge des réseaux, qui impliquent un système de notation beaucoup plus inquisitorial que n’importe quel concours, une dictature de la transparence, intrusive, et plus injuste que n’importe quel concours. Les réseaux sociaux ? C’est le grand panoptique. Faire leur apologie ? C’est tuer l’intimité, la pudeur, le quant à soi. Au profit des ego, du tank à soi.

Les communautés postmodernes ne sont pas non plus en tension vers quelque chose qui nous dépasse. Les auteurs voient les communautés comme résolument immanentes. Ils ont certainement raison de voir la condition postmoderne définitivement au-delà de tout péché originel. Reste que la fin du péché originel n’est pas la fin de toute verticalité. Elle ne devrait, en tout cas, pas l’être car aucun monde humain ne peut se passer de verticalité.

Nous serions passés de la raison au corps, du calcul à l’instinct. Du devoir-être rigide à l’invention libre de soi. De l’universalisme des droits de l’homme au particularisme des droits des tribus. De la raison normée au bricolage des justifications, de la Morale unique à des morales par tribus, voire à des morales par situations, validées par des groupes d’appartenance restreints, et non par la société toute entière.

Il nous faudrait nous réjouir de l’affaiblissement de la culture des « concours ». Fort bien. Mais si les concours ne sont pas toujours la solution idéale, que mettre à la place ? Le copinage, les relations ? Nous savons que celles-ci jouent un rôle, mais n’est-il pas justement utile de limiter ce rôle par des concours ? On en arrive au thème de l’élitisme républicain, et on comprend ici que c’est justement ce qui n’est pas du goût de nos auteurs « postmodernes ». Et pourtant, qu’obtient-on quand on abandonne l’élitisme républicain ? M. Benalla et M. Castaner. A la place de M. Chevènement, ou de M. Peyrefitte. Ils ne sont pas dépourvus d’entregent. Est-ce le seul critère qui doit prévaloir ? Est-ce préférable à un vieux serviteur de l’Etat, qui aurait un peu plus de crédibilité ? Quand Maffesoli oppose le katholon, c’est-à-dire tout simplement la totalité de ce que nous partageons à l’universalisme, en quoi cela nous fournit-il une solution ? La mise sur le marché des idées d’un terme peu usité ne peut tenir lieu de solution. Car le bien commun à tous renvoie toujours à ce qu’est ce « tous ». S’agit-il d’une simple communauté d’affinités sportives, sexuelles, éducatives, etc ? S’agit-il d’une communauté de « gamers » ? De « traders » ? De LGBT ? Que ces communautés existent ne pose aucun problème. La socialité passe partout et cela donne des communautés, plus ou moins conflictuelles du reste, et cela est très bien ainsi. Mais ces communautés restreintes ne remplacent pas des communautés plus vastes. Dans les communautés postmodernes, il ne s’agit jamais de la nation, de notre patrie, puisqu’elle transcenderait toutes les communautés, et que nulle transcendance n’est admise dans le paradis postmoderne, le « seul et vrai paradis », celui de l’horizontalité infinie.

Mais alors, qu’est-ce qui fait sens pour nous tous ? La réponse est que nous sommes devant un pur néant. Celui-ci ne peut que légitimer la déconstruction de tout Etat. Si rien ne nous rassemble en peuple, pourquoi un garant de ce rassemblement ? Mais si l’Etat n’est pas à lui tout seul le garant du bien commun, ni même l’unique élément d’un ordre public, il en est l’un des piliers. L’Etat ne doit pas être tout, mais il couronne le tout. Déconstruire tout Etat, c’est sortir de l’histoire, en d’autres termes, c’est devenir colonisés, c’est devenir sujet de l’histoire des autres. « L’anarchie, c’est l’ordre sans l’Etat », disaient Elisée Reclus et P-J Proudhon. Mais quand règne, dans de nombreux quartiers, une forme d’ensauvagement, ce n’est le moment de supprimer l’Etat, dont l’une des fonctions essentielles est la sécurité du peuple, aussi bien la sécurité intérieure que la sécurité extérieure (on peut certes imaginer des « tribus » de sociétés privées de sécurité, et de gardes du corps, et d’ailleurs, elles existent déjà, mais la sécurité est alors proportionnelle aux moyens financiers).

Mais alors, qu’est-ce qui fait sens pour nous tous ? La réponse est que nous sommes devant un pur néant. Celui-ci ne peut que légitimer la déconstruction de tout Etat. Si rien ne nous rassemble en peuple, pourquoi un garant de ce rassemblement ? Mais si l’Etat n’est pas à lui tout seul le garant du bien commun, ni même l’unique élément d’un ordre public, il en est l’un des piliers. L’Etat ne doit pas être tout, mais il couronne le tout. Déconstruire tout Etat, c’est sortir de l’histoire, en d’autres termes, c’est devenir colonisés, c’est devenir sujet de l’histoire des autres. « L’anarchie, c’est l’ordre sans l’Etat », disaient Elisée Reclus et P-J Proudhon. Mais quand règne, dans de nombreux quartiers, une forme d’ensauvagement, ce n’est le moment de supprimer l’Etat, dont l’une des fonctions essentielles est la sécurité du peuple, aussi bien la sécurité intérieure que la sécurité extérieure (on peut certes imaginer des « tribus » de sociétés privées de sécurité, et de gardes du corps, et d’ailleurs, elles existent déjà, mais la sécurité est alors proportionnelle aux moyens financiers).

Dans une optique purement communautaire, et en fait communautariste, ce que « nous » partageons ne renvoie qu’à de petites communautés qui ne font pas l’histoire. C’est-à-dire qu’elles subissent l’histoire. Il n’y a pas, ici, de troisième voie : l’histoire, on la fait, ou on la subit. La postmodernité que défend Michel Maffesoli, c’est encore la loi des frêres qui succède à la loi des pères. Les pairs plutôt que les pères. Mais c’est justement de cette mise à égalité que notre société meurt. Les pairs sont nécessaires. Mais les pères demeurent indispensables. Les pairs ne peuvent suppléer aux pères. Les apprenants sont mis sur le même plan que les professeurs, les conseils d’élèves doublonnent les structures d’adultes. Au final, tout le monde étant responsable de tout, plus personne n’est responsable de rien.

Enfin, les pairs ne sont pas une invention de la postmodernité. Qu’était un syndicat ? Sinon un regroupement entre pairs. Que sont les Gilets Jaunes ? Sinon des pairs. Les Gilets Jaunes sont plus proches des mouvements de la modernité militante que de la postmodernité « cool » et sage et ludique. Par le simple fait qu’ils ont le sentiment clair des mensonges du pouvoir, les Gilets Jaunes ne sont pas postmodernes. Dans ce cas, ils ne croiraient à aucune vérité, donc à aucun mensonge. Dans le monde postmoderne, il n’y a plus de distinction entre honnêteté et malhonnêteté. C’est exactement cela qui créait le désespoir de Wittgenstein, le sentiment que l’honnêteté n’est plus possible intellectuellement dans un monde postmoderne redevenu antésocratique, tandis que, anthropologiquement, Wittgenstein se sentait hanté par la question de l’honnêteté.

Les temps postmodernes ne sont plus à la croyance en la vérité. Ce qui amène la fin de la croyance en une justice, et en un bien commun. Le commun n’est plus que partiel : les usagers de trottinettes, la « communauté » blablacar, etc. Les tribus sont un moyen de développer du collectif sans politique. C’est-à-dire de laisser le pouvoir aux puissances d’argent. C’est pour cela que les fondés de pouvoir du Capital, qu’ils s’appellent Macron un jour ou Tartempion le lendemain les aiment tant.

Pierre Le Vigan

Michel Maffesoli et Hélène Strohl, La faillite des élites, 228 p., Lexio, 2019.

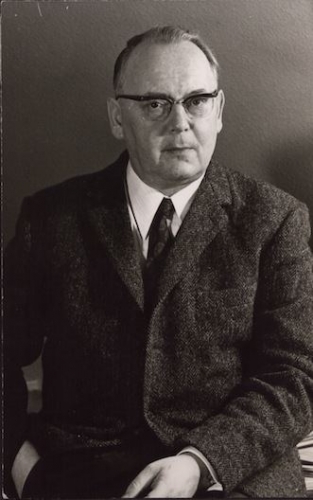

After the fall of the Third Reich in 1945, Schelsky joined the German Red Cross and formed its effective Suchdienst (service to trace down missing persons). In 1949 he became a Professor at the Hamburg "Hochschule für Arbeit und Politik", in 1953 at Hamburg University, and in 1960 he went to the University of Münster. There he headed what was then the biggest West German centre for social research, in Dortmund.

After the fall of the Third Reich in 1945, Schelsky joined the German Red Cross and formed its effective Suchdienst (service to trace down missing persons). In 1949 he became a Professor at the Hamburg "Hochschule für Arbeit und Politik", in 1953 at Hamburg University, and in 1960 he went to the University of Münster. There he headed what was then the biggest West German centre for social research, in Dortmund. After the Second World War, no longer a National Socialist, Schelsky became a star of applied sociology, due to his great gift of anticipating social and sociological developments. He published books on the theory of institutions, on social stratification, on the sociology of family, on the sociology of sexuality, on the sociology of youth, on Industrial Sociology, on the sociology of education, and on the sociology of the university system. In Dortmund, he made the Social Research Centre a West German focus of empirical and theoretical studies, being especially gifted in finding and attracting first class social scientists, e.g. Dieter Claessens, Niklas Luhmann, and many more.

After the Second World War, no longer a National Socialist, Schelsky became a star of applied sociology, due to his great gift of anticipating social and sociological developments. He published books on the theory of institutions, on social stratification, on the sociology of family, on the sociology of sexuality, on the sociology of youth, on Industrial Sociology, on the sociology of education, and on the sociology of the university system. In Dortmund, he made the Social Research Centre a West German focus of empirical and theoretical studies, being especially gifted in finding and attracting first class social scientists, e.g. Dieter Claessens, Niklas Luhmann, and many more. Schelsky was able to design Bielefeld University as an innovative institution of the highest academic quality, both in research and in thought. But the fact that his own university had moved away from his ideas hit him hard. His later books, criticizing ideological sociology (very much acclaimed now by conservative analysts) and on the sociology of law (quite influential in the Schools of Law) kept up his reputation as an outstanding thinker, but fell out of grace with younger sociologists. Moreover, his fascinating analyses, being of highest practical value, went out of date for the same reason; only by 2000 did new sociologists start to read him again.

Schelsky was able to design Bielefeld University as an innovative institution of the highest academic quality, both in research and in thought. But the fact that his own university had moved away from his ideas hit him hard. His later books, criticizing ideological sociology (very much acclaimed now by conservative analysts) and on the sociology of law (quite influential in the Schools of Law) kept up his reputation as an outstanding thinker, but fell out of grace with younger sociologists. Moreover, his fascinating analyses, being of highest practical value, went out of date for the same reason; only by 2000 did new sociologists start to read him again.

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

Der Sohn eines sächsischen Postdirektors erhielt seine Gymnasialausbildung am königlichen Elitegymnasium zu Dresden-Neustadt, studierte von 1907 bis 1911 in Leipzig Philosophie, Psychologie, Nationalökonomie und Geschichte, u.a. bei Wilhelm Wundt und Karl Lamprecht, in deren universalhistorischer Tradition er seine ersten Arbeiten zur Geschichtsauffassung der Aufklärung (Diss. 1911) und zur Bewertung der Wirtschaft in der deutschen Philosophie des 19. Jahrhunderts (Habilitation 1921) verfaßte. Nach zusätzlichen Studien in Berlin mit engen Kontakten zu Georg Simmel und Lehrtätigkeit an der Reformschule der Freien Schulgemeinde Wickersdorf kämpfte F. mit dem Militär-St.-Heinrichs-Orden ausgezeichnet im Ersten Weltkrieg. Als Mitglied des von Eugen Diederichs initiierten Serakreises der Jugendbewegungverfaßte F. an die Aufbruchsgeneration gerichtete philosophischen Schriften: Antäus (1918), Prometheus (1923), Pallas Athene (1935). Von 1922 bis 1925 lehrte er als Ordinarius hauptsächlich Kulturphilosophie an der Universität Kiel, erhielt 1925 den ersten deutschen Lehrstuhl für Soziologie ohne Beiordnung eines anderen Faches in Leipzig und widmete sich von nun an der logischen und historisch-philosophischen Grundlegung dieser neuen Disziplin. In Auseinandersetzung mit dem Positivismus seiner Lehrer und mit der Philosophie Hegels sollten typische gesellschaftliche Grundstrukturen herausgearbeitet und ihre historischen Entwicklungsgesetze gefunden werden. Darüber hinaus ist für F. die Soziologie als konkrete historische Erscheinung, erst durch die abendländische Aufklärung möglich geworden, Äußerung einer vorher nie dagewesenen gesellschaftlichen Emanzipation zur wissenschaftlichen Selbstreflexion, drückt deshalb als "Wirklichkeitswissenschaft" in der Erfassung des gegenwärtigen gesellschaftlichen Wandels auch den kollektiven Willen aus, ist also als Wissenschaft zugleich politische Ethik, die die Richtung des gesellschaftlichen Wandels zu bestimmen hat.

Der Sohn eines sächsischen Postdirektors erhielt seine Gymnasialausbildung am königlichen Elitegymnasium zu Dresden-Neustadt, studierte von 1907 bis 1911 in Leipzig Philosophie, Psychologie, Nationalökonomie und Geschichte, u.a. bei Wilhelm Wundt und Karl Lamprecht, in deren universalhistorischer Tradition er seine ersten Arbeiten zur Geschichtsauffassung der Aufklärung (Diss. 1911) und zur Bewertung der Wirtschaft in der deutschen Philosophie des 19. Jahrhunderts (Habilitation 1921) verfaßte. Nach zusätzlichen Studien in Berlin mit engen Kontakten zu Georg Simmel und Lehrtätigkeit an der Reformschule der Freien Schulgemeinde Wickersdorf kämpfte F. mit dem Militär-St.-Heinrichs-Orden ausgezeichnet im Ersten Weltkrieg. Als Mitglied des von Eugen Diederichs initiierten Serakreises der Jugendbewegungverfaßte F. an die Aufbruchsgeneration gerichtete philosophischen Schriften: Antäus (1918), Prometheus (1923), Pallas Athene (1935). Von 1922 bis 1925 lehrte er als Ordinarius hauptsächlich Kulturphilosophie an der Universität Kiel, erhielt 1925 den ersten deutschen Lehrstuhl für Soziologie ohne Beiordnung eines anderen Faches in Leipzig und widmete sich von nun an der logischen und historisch-philosophischen Grundlegung dieser neuen Disziplin. In Auseinandersetzung mit dem Positivismus seiner Lehrer und mit der Philosophie Hegels sollten typische gesellschaftliche Grundstrukturen herausgearbeitet und ihre historischen Entwicklungsgesetze gefunden werden. Darüber hinaus ist für F. die Soziologie als konkrete historische Erscheinung, erst durch die abendländische Aufklärung möglich geworden, Äußerung einer vorher nie dagewesenen gesellschaftlichen Emanzipation zur wissenschaftlichen Selbstreflexion, drückt deshalb als "Wirklichkeitswissenschaft" in der Erfassung des gegenwärtigen gesellschaftlichen Wandels auch den kollektiven Willen aus, ist also als Wissenschaft zugleich politische Ethik, die die Richtung des gesellschaftlichen Wandels zu bestimmen hat. F. war ab 1933 Direktor des Instituts für Kultur- und Universalgeschichte an der Leipziger Universität. Als neu gewählter Präsident der Deutschen Gesellschaft für Soziologie legte er diese 1933 still, um eine politische "Gleichschaltung" zu verhindern. Den damaligen europäischen politischen Umbrüchen brachte F. als Theoretiker des Wandels zunächst offenes Interesse entgegen, fühlte sich der theoretischen Erfassung dieser Entwicklungen verpflichtet und war deshalb nie aktives Mitglied einer politischen Partei oder Bewegung; er wurde später der "konservativen Revolution" der zwanziger Jahre als "jungkonservativer Einzelgänger" (Mohler) zugeordnet. Die vor 1933 noch idealistisch formulierte Konzeption des Staates als höchste Form der Kultur (1925) hat F. im Lauf der bedrohlichen politischen Entwicklung revidiert in seinen Studien über Machiavelli (1936) und Friedrich den Großen (Preußentum und Aufklärung 1944) durch einen realistischen Staatsbegriff, der ausschließlich durch Gemeinwohl, langfristige gesellschaftliche Entwicklungsperspektiven und durch prozessuale Kriterien der Legitimität gerechtfertigt ist: durch den Dienst am Staat, der aber den Menschen keinesfalls total vereinnahmen darf, sowie die Prägekraft des Staates, der dem Kollektiv ein gemeinsames Ziel gibt, aber dennoch die Freiheit und Menschenwürde seiner Bürger bewahrt. Insbesondere gelang F. in der Darstellung der Legitimität als generellem Gesetz jeder Politik eine dialektische Verknüpfung des naturrechtlichen Herrschaftsgedankens mit der klassischen bürgerlich-humanitären Aufklärung: Nur die Herrschaft ist legitim, die dem Sinn ihres Ursprungs entspricht - es muß das erfüllt werden, was das Volk mit der Einsetzung der Herrschaft gewollt hat.

F. war ab 1933 Direktor des Instituts für Kultur- und Universalgeschichte an der Leipziger Universität. Als neu gewählter Präsident der Deutschen Gesellschaft für Soziologie legte er diese 1933 still, um eine politische "Gleichschaltung" zu verhindern. Den damaligen europäischen politischen Umbrüchen brachte F. als Theoretiker des Wandels zunächst offenes Interesse entgegen, fühlte sich der theoretischen Erfassung dieser Entwicklungen verpflichtet und war deshalb nie aktives Mitglied einer politischen Partei oder Bewegung; er wurde später der "konservativen Revolution" der zwanziger Jahre als "jungkonservativer Einzelgänger" (Mohler) zugeordnet. Die vor 1933 noch idealistisch formulierte Konzeption des Staates als höchste Form der Kultur (1925) hat F. im Lauf der bedrohlichen politischen Entwicklung revidiert in seinen Studien über Machiavelli (1936) und Friedrich den Großen (Preußentum und Aufklärung 1944) durch einen realistischen Staatsbegriff, der ausschließlich durch Gemeinwohl, langfristige gesellschaftliche Entwicklungsperspektiven und durch prozessuale Kriterien der Legitimität gerechtfertigt ist: durch den Dienst am Staat, der aber den Menschen keinesfalls total vereinnahmen darf, sowie die Prägekraft des Staates, der dem Kollektiv ein gemeinsames Ziel gibt, aber dennoch die Freiheit und Menschenwürde seiner Bürger bewahrt. Insbesondere gelang F. in der Darstellung der Legitimität als generellem Gesetz jeder Politik eine dialektische Verknüpfung des naturrechtlichen Herrschaftsgedankens mit der klassischen bürgerlich-humanitären Aufklärung: Nur die Herrschaft ist legitim, die dem Sinn ihres Ursprungs entspricht - es muß das erfüllt werden, was das Volk mit der Einsetzung der Herrschaft gewollt hat. Zentraler Gesichtspunkt seiner Nachkriegsschriften war die gegenwärtige Epochenschwelle, der Übergang der modernen Industriegesellschaft zur weltweit ausgreifenden wissenschaftlich-technischen Rationalität, deren "sekundäre Systeme" alle naturhaft gewachsenen Lebensformen erfassen. F. weist nach, wie diese Fortschrittsordnung zum tragenden Kulturfaktor wird in allen Teilentwicklungen: der Technik, Siedlungsformen, Arbeit und Wertungen. Seine frühere integrative Perspektive einer Kultursynthese wird ersetzt durch den Konflikt von eigengesetzlichen, künstlichen Sachwelten einerseits und den "haltenden Mächte" des sozialen Lebens andererseits, die im "Katarakt des Fortschritts" auf wenige, die private Lebenswelt beherrschende Gemeinschaftsformen beschränkt sind. Jedoch bleibt die Synthese von "Leben" und "Form", von Menschlichkeit und technischer Zivilisation für F. weiterhin unerläßlich für den Fortbestand jeder Kultur, im krisenhaften Übergang noch nicht erreicht, aber durchaus denkbar jenseits der Schwelle, wenn sich die neue geschichtliche Epoche der weltumspannenden Industriekultur konsolidieren wird. F.s Theorie der Industriekultur, kurz vor seinem Tode begonnen, ist unvollendet geblieben. Sein strukturhistorisches Konzept der Epochenschwelle hat in der deutschen Nachkriegssoziologie weniger Aufnahme gefunden, während es in der deutschen Geschichtswissenschaft wesentlich zur Überwindung einer evolutionären Entwicklungsgeschichte beigetragen hat und eine sozialwissenschaftlich orientierte Strukturgeschichtsschreibung einleitete, wofür F.s Konzept der Eigendynamik der sekundären Systeme ebenso ausschlaggebend war.

Zentraler Gesichtspunkt seiner Nachkriegsschriften war die gegenwärtige Epochenschwelle, der Übergang der modernen Industriegesellschaft zur weltweit ausgreifenden wissenschaftlich-technischen Rationalität, deren "sekundäre Systeme" alle naturhaft gewachsenen Lebensformen erfassen. F. weist nach, wie diese Fortschrittsordnung zum tragenden Kulturfaktor wird in allen Teilentwicklungen: der Technik, Siedlungsformen, Arbeit und Wertungen. Seine frühere integrative Perspektive einer Kultursynthese wird ersetzt durch den Konflikt von eigengesetzlichen, künstlichen Sachwelten einerseits und den "haltenden Mächte" des sozialen Lebens andererseits, die im "Katarakt des Fortschritts" auf wenige, die private Lebenswelt beherrschende Gemeinschaftsformen beschränkt sind. Jedoch bleibt die Synthese von "Leben" und "Form", von Menschlichkeit und technischer Zivilisation für F. weiterhin unerläßlich für den Fortbestand jeder Kultur, im krisenhaften Übergang noch nicht erreicht, aber durchaus denkbar jenseits der Schwelle, wenn sich die neue geschichtliche Epoche der weltumspannenden Industriekultur konsolidieren wird. F.s Theorie der Industriekultur, kurz vor seinem Tode begonnen, ist unvollendet geblieben. Sein strukturhistorisches Konzept der Epochenschwelle hat in der deutschen Nachkriegssoziologie weniger Aufnahme gefunden, während es in der deutschen Geschichtswissenschaft wesentlich zur Überwindung einer evolutionären Entwicklungsgeschichte beigetragen hat und eine sozialwissenschaftlich orientierte Strukturgeschichtsschreibung einleitete, wofür F.s Konzept der Eigendynamik der sekundären Systeme ebenso ausschlaggebend war.

La parution de L'Ere du vide, en 1983, fit grand bruit. Gilles Lipovetsky apparaissait comme un observateur de la société postmoderne, celle qui voyait simultanément l'écroulement des grandes idéologies et le développement de l'individualisme. Ce livre marquait l'entrée en scène tonitruante d'un « Narcisse cool et affranchi ».

La parution de L'Ere du vide, en 1983, fit grand bruit. Gilles Lipovetsky apparaissait comme un observateur de la société postmoderne, celle qui voyait simultanément l'écroulement des grandes idéologies et le développement de l'individualisme. Ce livre marquait l'entrée en scène tonitruante d'un « Narcisse cool et affranchi ». L’existence dans l’hypermodernité expose un versant refoulé dans excès et une dualité, où la frivolité masque une profonde anxiété existentielle collective. De là naît un rapport crispé sur le présent, lequel triomphe dans le règne de l'émotivité angoissée. L'effondrement des traditions est alors vécu sur le mode de l'inquiétude et non sur la conquête de libertés individuelles et collectives. L'hypermodernité, pour Lipovetsky, tient également lieu de chance à saisir, celle d'une responsabilisation renouvelée du sujet.

L’existence dans l’hypermodernité expose un versant refoulé dans excès et une dualité, où la frivolité masque une profonde anxiété existentielle collective. De là naît un rapport crispé sur le présent, lequel triomphe dans le règne de l'émotivité angoissée. L'effondrement des traditions est alors vécu sur le mode de l'inquiétude et non sur la conquête de libertés individuelles et collectives. L'hypermodernité, pour Lipovetsky, tient également lieu de chance à saisir, celle d'une responsabilisation renouvelée du sujet.

On peut également citer Jean-Loup Izambert, avec ses reportages incomparables et ses livres minutieusement documentés, comme « 56 », Tome 1, l’État français complice de groupes criminels ; Tome 2, Mensonges et crimes d’État…. Crimes sans châtiment… etc. On peut encore renvoyer le lecteur intéressé par la qualité et l’objectivité journalistique sur ce type de sujets, à Paul Moreira qui a traité la question de l’Ukraine et les crimes impardonnables de l’Occident.

On peut également citer Jean-Loup Izambert, avec ses reportages incomparables et ses livres minutieusement documentés, comme « 56 », Tome 1, l’État français complice de groupes criminels ; Tome 2, Mensonges et crimes d’État…. Crimes sans châtiment… etc. On peut encore renvoyer le lecteur intéressé par la qualité et l’objectivité journalistique sur ce type de sujets, à Paul Moreira qui a traité la question de l’Ukraine et les crimes impardonnables de l’Occident. A les entendre, il semblerait que oui ! Il semblerait que ce fut le cas de François Mitterrand théoriquement socialiste, de François Hollande théoriquement socialiste, d’Alexis Tsipras théoriquement de gauche. On se rappelle de la description faite par Tsipras évoquant le couteau sous la gorge tenu par les Allemands alors que Hollande se faisait collaborateur docile aux ordres de Merkel.

A les entendre, il semblerait que oui ! Il semblerait que ce fut le cas de François Mitterrand théoriquement socialiste, de François Hollande théoriquement socialiste, d’Alexis Tsipras théoriquement de gauche. On se rappelle de la description faite par Tsipras évoquant le couteau sous la gorge tenu par les Allemands alors que Hollande se faisait collaborateur docile aux ordres de Merkel.

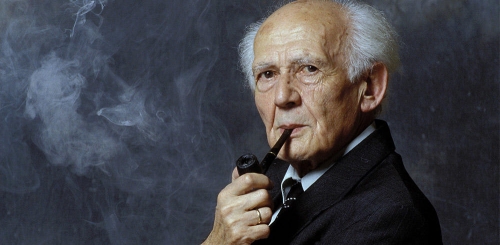

On va relire le sociologue israélo-britannique Zygmunt Bauman, auteur de remarquables essais sur notre postmoderne et zombi mondialisation. Il a bien compris que la clé c’est la peur et son exploitation (on est en 2002) :

On va relire le sociologue israélo-britannique Zygmunt Bauman, auteur de remarquables essais sur notre postmoderne et zombi mondialisation. Il a bien compris que la clé c’est la peur et son exploitation (on est en 2002) : Bauman ici explique pourquoi on croule sous d’horribles et coûteuses voitures informelles. Cela correspond à la paranoïa du « « capitalisme de catastrophe » (Ramonet) :

Bauman ici explique pourquoi on croule sous d’horribles et coûteuses voitures informelles. Cela correspond à la paranoïa du « « capitalisme de catastrophe » (Ramonet) : Il est important de rappeler cela, qu’il s’agisse de Sarkozy-Macron-Hollande, de Bush, May, Clinton-Obama, Merkel et du reste ; l’Etat fasciste-sécuritaire accompagne la dégradation-extinction de l’Etat de droit et de l’État social. L’État renonce à la carotte et a recours à la trique du CRS et au contrôle par des services plus ou moins secrets :

Il est important de rappeler cela, qu’il s’agisse de Sarkozy-Macron-Hollande, de Bush, May, Clinton-Obama, Merkel et du reste ; l’Etat fasciste-sécuritaire accompagne la dégradation-extinction de l’Etat de droit et de l’État social. L’État renonce à la carotte et a recours à la trique du CRS et au contrôle par des services plus ou moins secrets : On a tous vu la nullité brouillonne des forces du désordre à Strasbourg. Mais ce chaos fait partie de la mise en scène, et Bauman vous l’explique :

On a tous vu la nullité brouillonne des forces du désordre à Strasbourg. Mais ce chaos fait partie de la mise en scène, et Bauman vous l’explique :

Certes, ces outils de partage de véhicules, ou de chambres, rendent à coup sûr bien des services, alliant l’intérêt financier à des contacts humains qui peuvent être sympathiques, bien que la plupart du temps, très superficiels. Mais nos auteurs oublient une caractéristique de tous ces réseaux. C’est la notation, ce sont les « étoiles » à affecter à chaque « partenaire », c’est la mise en ligne des « avis », ce sont les commentaires qui sont publics, etc. C’est la tyrannie de la transparence. Et alors que les auteurs critiquent les concours, ils font l’éloge des réseaux, qui impliquent un système de notation beaucoup plus inquisitorial que n’importe quel concours, une dictature de la transparence, intrusive, et plus injuste que n’importe quel concours. Les réseaux sociaux ? C’est le grand panoptique. Faire leur apologie ? C’est tuer l’intimité, la pudeur, le quant à soi. Au profit des ego, du tank à soi.

Certes, ces outils de partage de véhicules, ou de chambres, rendent à coup sûr bien des services, alliant l’intérêt financier à des contacts humains qui peuvent être sympathiques, bien que la plupart du temps, très superficiels. Mais nos auteurs oublient une caractéristique de tous ces réseaux. C’est la notation, ce sont les « étoiles » à affecter à chaque « partenaire », c’est la mise en ligne des « avis », ce sont les commentaires qui sont publics, etc. C’est la tyrannie de la transparence. Et alors que les auteurs critiquent les concours, ils font l’éloge des réseaux, qui impliquent un système de notation beaucoup plus inquisitorial que n’importe quel concours, une dictature de la transparence, intrusive, et plus injuste que n’importe quel concours. Les réseaux sociaux ? C’est le grand panoptique. Faire leur apologie ? C’est tuer l’intimité, la pudeur, le quant à soi. Au profit des ego, du tank à soi.  Mais alors, qu’est-ce qui fait sens pour nous tous ? La réponse est que nous sommes devant un pur néant. Celui-ci ne peut que légitimer la déconstruction de tout Etat. Si rien ne nous rassemble en peuple, pourquoi un garant de ce rassemblement ? Mais si l’Etat n’est pas à lui tout seul le garant du bien commun, ni même l’unique élément d’un ordre public, il en est l’un des piliers. L’Etat ne doit pas être tout, mais il couronne le tout. Déconstruire tout Etat, c’est sortir de l’histoire, en d’autres termes, c’est devenir colonisés, c’est devenir sujet de l’histoire des autres. « L’anarchie, c’est l’ordre sans l’Etat », disaient Elisée Reclus et P-J Proudhon. Mais quand règne, dans de nombreux quartiers, une forme d’ensauvagement, ce n’est le moment de supprimer l’Etat, dont l’une des fonctions essentielles est la sécurité du peuple, aussi bien la sécurité intérieure que la sécurité extérieure (on peut certes imaginer des « tribus » de sociétés privées de sécurité, et de gardes du corps, et d’ailleurs, elles existent déjà, mais la sécurité est alors proportionnelle aux moyens financiers).

Mais alors, qu’est-ce qui fait sens pour nous tous ? La réponse est que nous sommes devant un pur néant. Celui-ci ne peut que légitimer la déconstruction de tout Etat. Si rien ne nous rassemble en peuple, pourquoi un garant de ce rassemblement ? Mais si l’Etat n’est pas à lui tout seul le garant du bien commun, ni même l’unique élément d’un ordre public, il en est l’un des piliers. L’Etat ne doit pas être tout, mais il couronne le tout. Déconstruire tout Etat, c’est sortir de l’histoire, en d’autres termes, c’est devenir colonisés, c’est devenir sujet de l’histoire des autres. « L’anarchie, c’est l’ordre sans l’Etat », disaient Elisée Reclus et P-J Proudhon. Mais quand règne, dans de nombreux quartiers, une forme d’ensauvagement, ce n’est le moment de supprimer l’Etat, dont l’une des fonctions essentielles est la sécurité du peuple, aussi bien la sécurité intérieure que la sécurité extérieure (on peut certes imaginer des « tribus » de sociétés privées de sécurité, et de gardes du corps, et d’ailleurs, elles existent déjà, mais la sécurité est alors proportionnelle aux moyens financiers).

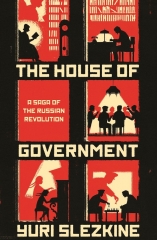

The book has given me a breakthrough in understanding why so many people who grew up under communism are unnerved by what’s going on in the West today, even if they can’t all articulate it beyond expressing intense but inchoate anxiety about political correctness. Reading

The book has given me a breakthrough in understanding why so many people who grew up under communism are unnerved by what’s going on in the West today, even if they can’t all articulate it beyond expressing intense but inchoate anxiety about political correctness. Reading

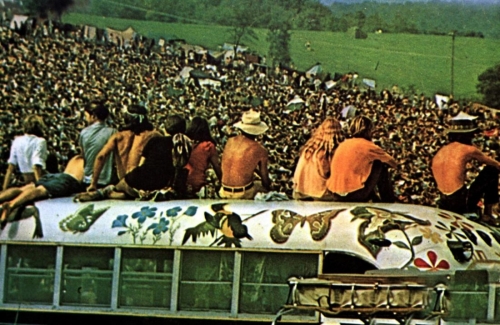

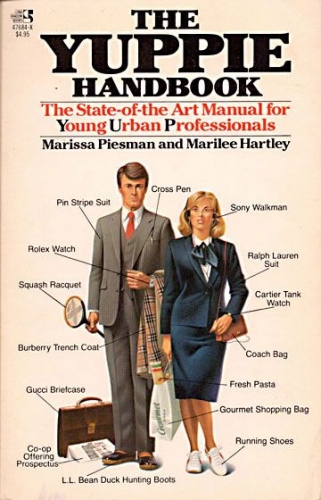

Selon la sociologue Elizabeth Nolan Brown, les « jeunes citadins professionnels »,”yuccies” (Young Urban Professional), les nouveaux free lancers capitalistes combinent les idéaux de la contre-culture et l’esprit d’entreprise de Sillicon Valley. Certains parlent déjà de l’émergence d’un nouveau “capitalisme indie” combinant micro-artisanat et micro-entreprises, éditions limitées, nouveaux modes de consommation et de production, humanisme et écologie avec le capitalisme de réseaux. Cette nouvelle génération s’intègre parfaitement dans la logique postmoderne et marchande du vintage, de l’ironie et du pastiche, mais aussi du marché et des bénéfices réalisés sur fond de contre-culture et de subversions créatives. Elle s’intègre à merveille dans une nouvelle stratégie de marketing de réseau – à travers divers réseaux sociaux, sites Web, blogs, clubs, comme une expérience de marketing de masse.

Selon la sociologue Elizabeth Nolan Brown, les « jeunes citadins professionnels »,”yuccies” (Young Urban Professional), les nouveaux free lancers capitalistes combinent les idéaux de la contre-culture et l’esprit d’entreprise de Sillicon Valley. Certains parlent déjà de l’émergence d’un nouveau “capitalisme indie” combinant micro-artisanat et micro-entreprises, éditions limitées, nouveaux modes de consommation et de production, humanisme et écologie avec le capitalisme de réseaux. Cette nouvelle génération s’intègre parfaitement dans la logique postmoderne et marchande du vintage, de l’ironie et du pastiche, mais aussi du marché et des bénéfices réalisés sur fond de contre-culture et de subversions créatives. Elle s’intègre à merveille dans une nouvelle stratégie de marketing de réseau – à travers divers réseaux sociaux, sites Web, blogs, clubs, comme une expérience de marketing de masse.

En France, Michel Clouscard a été le principal penseur de cette dynamique de transformation du “capitalisme de la séduction“, voyant dans le mouvement hippie une simple crise interne de la dynamique du capitalisme américain, qui s’est approprié et a recentré les slogans de gauche libérale (individualisme, hédonisme, nomadisme, cosmopolitisme) en les mettant au service de la logique du “marché du désir”, du nouveau capitalisme “libéral-libertaire”.

En France, Michel Clouscard a été le principal penseur de cette dynamique de transformation du “capitalisme de la séduction“, voyant dans le mouvement hippie une simple crise interne de la dynamique du capitalisme américain, qui s’est approprié et a recentré les slogans de gauche libérale (individualisme, hédonisme, nomadisme, cosmopolitisme) en les mettant au service de la logique du “marché du désir”, du nouveau capitalisme “libéral-libertaire”.

Et Marx commente et explique les passages cités :

Et Marx commente et explique les passages cités :

Vanaf de openingspagina is duidelijk welke auteur voor Mel Bontje een grote inspirator is. Seks in een boek is één ding, maar waarom toch die fascinatie met zelfbevlekking? Een ander feit dat in het oog springt is dat de auteur doorklinkt in de gesprekken. Hij laat zich kennen in zowel zijn fascinatie met aftandsheid en verval, als in zijn erudiete woordkeuzes om sociale analyses uit te drukken. Dit rijmt niet overal met de personages: het zijn deftige zinnen waarmee de jonge geest absoluut en doordringend oordeelt over de werkelijkheid.

Vanaf de openingspagina is duidelijk welke auteur voor Mel Bontje een grote inspirator is. Seks in een boek is één ding, maar waarom toch die fascinatie met zelfbevlekking? Een ander feit dat in het oog springt is dat de auteur doorklinkt in de gesprekken. Hij laat zich kennen in zowel zijn fascinatie met aftandsheid en verval, als in zijn erudiete woordkeuzes om sociale analyses uit te drukken. Dit rijmt niet overal met de personages: het zijn deftige zinnen waarmee de jonge geest absoluut en doordringend oordeelt over de werkelijkheid.