La crítica a “la cosa en sí”

(Schopenhauer-Brentano-Scheler)

Alberto Buela (*)

La aparición de Kant (1724-1804) en la historia de la filosofía ha sido caracterizada, no sin razón, como la revolución copernicana de la disciplina. Y así como con Copérnico el sol se transformó en centro del universo desplazando a la tierra, así con Kant la filosofía en el problema del conocimiento dejó de considerar al sujeto un ente pasivo para otorgarle actividad. El mundo dejo de ser el mundo para ser “mi mundo”. El mundo es la representación que el sujeto tiene de él.

Pero Kant fue más allá y concibió a los entes siendo fenómenos para la gnoseología y noúmenos para la metafísica. Es decir, los entes nos ofrecen lo que podemos conocer pero además poseen un “en sí” ignoto. Y acá Kant comete el más grande y profundo error que produce la metafísica moderna: afirmar que existe “la cosa en sí”.

Ya Fichte(1762-1814), en vida de Kant y entrevistándose con él le dijo: ¿cómo puedo sostener, sin contradicción, la existencia de “la cosa en sí”, si al mismo tiempo no puedo conocerla?. Kant lo despachó con cajas destempladas.

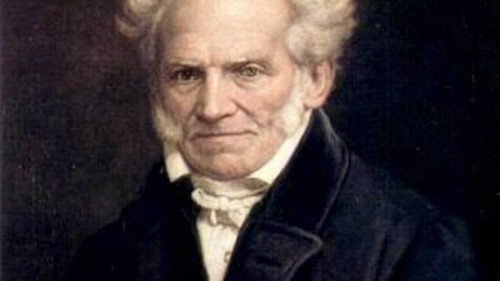

Luego vino Schopenhauer (1788-1860) y demostró que la cosa en sí es la voluntad y el mundo no es otra cosa que voluntad y representación. La representación que nos hacemos de los fenómenos y la voluntad que es su fundamento. En forma inteligente y profunda, el solitario de Danzig, no fue contra todo Kant sino contra la parte espuria y errónea de su filosofía.

Se produce en el ínterin una especie de suspensión del pensamiento filosófico clásico con la aparición, cada uno en su estilo, de Feuerbach(1804-1872), A.Ruge(1802-1880), Marx(1818-1883), Stirner(1806-1856), Bauer(1809-1882), Kierkegaard (1813-1855), Nietzsche (1844-1900) donde el tema principal de la metafísica, “la cosa en sí o el ente en tanto ente” , es dejado de lado.

Pero resulta que hay un filósofo en el medio. Ignorado, silenciado, postergado, no comprendido. El hombre más inteligente, profundo y cautivador de su tiempo, Franz Brentano (1838-1917), que se da cuenta y entonces va a afirmar que el ser último de la conciencia es “ser intencional” y que dicha intencionalidad nos revela que el objeto no tiene una existencia en una zona allende, en una realidad independiente, sino que existe en tanto que hay acto psíquico como correlato de éste. De modo que el objeto es concebido como fenómeno, pero el ente es una realidad sustancial que está allí y que tiene existencia independiente del sujeto cognoscente. Es lo evidente, y lo evidente no necesita prueba, pues todo lo que es, es y lo que no es, no es.

Muchos años después, Heidegger (1889-1976) en carta el P. Richardson le cuenta que se inició en filosofía leyendo a Brentano y que su Aristóteles sigue siendo el de Brentano. Y que, “lo que yo esperaba de Husserl era las respuestas a las preguntas suscitadas por Brentano”.

Finalmente Max Scheler (1874-1928), discípulo de E. Husserl que lo fue, a su vez, de Brentano, es el que ofrece una respuesta total y definitiva al falso problema planteado por Kant cuando en uno de sus últimos trabajos afirma: “Ser real es mas bien, ser resistencia frente a la espontaneidad originaria, que es una y la misma en todas las especies del querer y del atender”. La cosa en sí no existe como tal sino que es el impulso de resistencia que el ente nos ofrece cuando actuamos sobre él.

Curiosamente en Heidegger, donde uno esperaría encontrar una crítica furibunda a la cosa en sí, no sólo no se encuentra sino que en el texto emblemático sobre el asunto, Kant y el problema de la metafísica, que para mayor curiosidad dedica a Max Scheler, aparece una aceptación explícita cuando hablando del objeto trascendental igual X afirma: “X es un “algo”, sobre el cual, en general, nada podemos saber…”ni siquiera” puede convertirse en objeto posible de un saber” . ¿No se aplica acá, la objeción de Fichte a Kant?. ¿Será por esto que en las conversaciones de Davos, en torno a Kant, Ernst Cassirer afirmó: “Heidegger es un neokantiano como jamás lo hubiera imaginado de él”.

I- Schopenhauer: el primer golpe a la Ilustración

En Arturo Schopenhauer (1788-1860) toda su filosofía se apoya en Kant y forma parte del idealismo alemán pero lo novedoso es que sostiene dos rasgos existenciales antitéticos con ellos: es un pesimista y no es un profesor a sueldo del Estado. Esto último deslumbró a Nietzsche.

Hijo de un gran comerciante de Danzig, su posición acomodada lo liberó de las dos servidumbres de su época para los filósofos: la teología protestante o la docencia privada. Se educó a través de sus largas estadías en Inglaterra, Francia e Italia (Venecia). Su apetito sensual, grado sumo, luchó siempre la serena reflexión filosófica. Su soltería y misoginia nos recuerda el tango: en mi vida tuve muchas minas pero nunca una mujer. En una palabra, conoció la hembra pero no a la mujer.

Ingresa en la Universidad de Gotinga donde estudia medicina, luego frecuenta a Goethe, sigue cursos en Berlín con Fichte y se doctora en Jena con una tesis sobre La cuádruple raíz del principio de razón suficiente en 1813.

En 1819 publica su principal obra El mundo como voluntad y representación y toda su producción posterior no va a ser sino un comentario aumentado y corregido de ella. Nunca se retractó de nada ni nunca cambió. Obras como La voluntad en la naturaleza (1836), Libertad de la voluntad (1838), Los dos problemas fundamentales de la ética (1841) son simples escolios a su única obra principal.

Sobre él ha afirmado el genial Castellani: “Schopen es malo, pero simpático. No fue católico por mera casualidad. Y fue lástima porque tenía ala calderoniana y graciana, a quienes tradujo. Pero fue “antiprotestante” al máximo, como Nietzsche, lo cual en nuestra opinión no es poco…Tuvo dos fallas: fue el primer filósofo existencial sin ser teólogo y quiso reducir a la filosofía aquello que pertenece a la teología”

En 1844 reedita su trabajo cumbre, aunque no se habían vendido aun los ejemplares de su primera edición, llevando los agregados al doble la edición original.

Nueve años antes de su muerte publica dos tomos pequeños Parerga y Parilepómena, ensayos de acceso popular donde trata de los más diversos temas, que tienen muy poco que ver con su obra principal, pero que le dan una cierta popularidad al ser los más leídos de sus libros. Al final de sus días Schopenhauer gozó del reconocimiento que tanto buscó y que le fue esquivo.

Schopenhauer siguió los cursos de Fichte en Berlín varios años y como “el fanfarrón”, así lo llama, parte y depende también de Kant.

Así, ambos reconocen que el mérito inmortal de la crítica kantiana de la razón es haber establecido, de una vez y para siempre, que los entes, el mundo de las cosas que percibimos por los sentidos y reproducimos en el espíritu, no es el mundo en sí sino nuestro mundo, un producto de nuestra organización psicofísica.

La clara distinción en Kant entre sensibilidad y entendimiento pero donde el entendimiento no puede separarse realmente de los sentidos y refiere a una causa exterior la sensación que aparece bajo las formas de espacio y tiempo, viene a explicar a los entes, las cosas como fenómenos pero no como “cosas en sí”.

Muy acertadamente observa Silvio Maresca que: “Ante sus ojos- los de Schopenhauer- el romanticismo filosófico y el idealismo (Fichte-Hegel) que sucedieron casi enseguida a la filosofía kantiana, constituían una tergiversación de ésta. ¿Por qué? Porque abolían lo que según él era el principio fundamental: la distinción entre los fenómenos y la cosa en sí”.

Fichte a través de su Teoría de la ciencia va a sostener que el no-yo (los entes exteriores) surgen en el yo legalmente pero sin fundamento. No existe una tal cosa en sí. El mundo sensible es una realidad empírica que está de pie ahí. La ciencia de la naturaleza es necesariamente materialista. Schopenhauer es materialista, pero va a afirmar: Toda la imagen materialista del mundo, es solo representación, no “cosa en sí”. Rechaza la tesis que todo el mundo fenoménico sea calificado como un producto de la actividad inconciente del yo. ¿Que es este mundo además de mi representación?, se pregunta. Y responde que se debe partir del hombre que es lo dado y de lo más íntimo de él, y eso debe ser a su vez lo más íntimo del mundo y esto es la voluntad. Se produce así en Schopenhauer un primado de lo práctico sobre lo teórico.

La voluntad es, hablando en kantiano “la cosa en sí” ese afán infinito que nunca termina de satisfacerse, es “el vivir” que va siempre al encuentro de nuevos problemas. Es infatigable e inextinguible.

La voluntad no es para el pesimista de Danzig la facultad de decidir regida por la razón como se la entiende regularmente sino sólo el afán, el impulso irracional que comparten hombre y mundo. “Toda fuerza natural es concebida per analogiam con aquello que en nosotros mismos conocemos como voluntad”.

Esa voluntad irracional para la que el mundo y las cosas son solo un fenómeno no tiene ningún objetivo perdurable sino sólo aparente (por trabajar sobre fenómenos) y entonces todo objetivo logrado despierta nuevas necesidades (toda satisfacción tiene como presupuesto el disgusto de una insatisfacción) donde el no tener ya nada que desear preanuncia la muerte o la liberación.

Porque el más sabio es el que se percata que la existencia es una sucesión de sin sabores que no conduce a nada y se desprende del mundo. No espera la redención del progreso y solo practica la no-voluntad.

El pesimista de Danzig al identificar la voluntad irracional con la “cosa en sí” puede afirmar sin temor que “lo real es irracional y lo irracional es lo real” con lo que termina invirtiendo la máxima hegeliana “todo lo racional es real y todo lo real es racional”. Es el primero del los golpes mortales que se le aplicará al racionalismo iluminista, luego vendrá Nietzsche y más tarde Scheler y Heidegger. Pero eso ya es historia conocida. Salute.

Post Scriptum:

Schopenhauer en sus últimos años- que además de hablar correctamente en italiano, francés e inglés, hablaba, aunque con alguna dificultad, en castellano. La hispanofilia de Schopenhauer se reconoce en toda su obra pues cada vez que cita, sobre todo a Baltasar Gracián (1601-1658), lo hace en castellano. Aprendió el español para traducir el opúsculo Oráculo manual (1647). También cita a menudo El Criticón a la que considera “incomparable”. Existe actualmente en Alemania y desde hace unos quince años una revista de pensamiento no conformista denominada “Criticón”. También cita y traduce a Calderón de la Barca.

Miguel de Unamuno fue el primero que realizó algunas traducciones parciales del filósofo de Danzig, como corto pago para una deuda hispánica con él. En Argentina ejerció influencia sobre Macedonio Fernández y sobre su discípulo Jorge Luis Borges. Tengo conocimiento de dos buenos artículos sobre Schopenhauer en nuestro país: el del cura Castellani (Revista de la Universidad de Buenos Aires, cuarta época, Nº 16, 1950) y el mencionado de Maresca.

El último aporte hispano a Schopenhauer es la traducción de los Sinilia, los pensamientos de vejez (1852-1860) con introducción, traducción y notas de Juan Mateu Alonso, en Contrastes, Universidad de Málaga, enero-febrero, 2009.

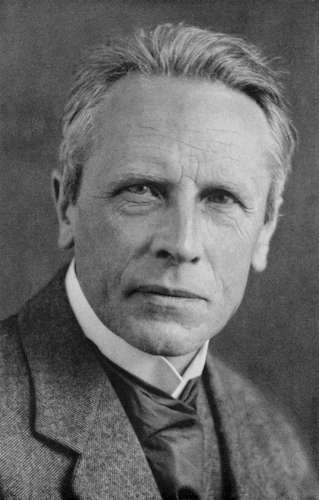

II- Brentano, el eslabón perdido de la filosofía contemporánea

Su vida y sus influencias

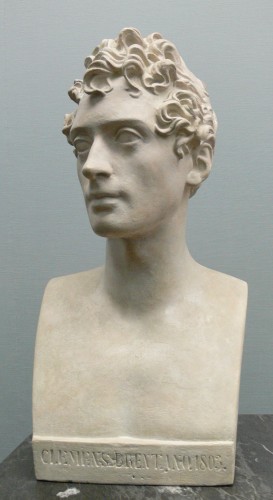

Franz Clemens Brentano (1838-1917) es el filósofo alemán de ancestros italianos de la zona de Cuomo, que introduce la noción de intencionalidad en la filosofía contemporánea. Noción que deriva del concepto escolástico de “cogitativa” trabajado tanto por Tomás de Aquino como por Duns Escoto en la baja edad media. Lectores que, junto con Aristóteles, conocía Brentano casi a la perfección y que leía fluidamente en sus lenguas originales.

Se lo considera tanto el precursor de la fenomenología (sus trabajos sobre la intencionalidad de la conciencia) como de las corrientes analíticas (sus trabajos sobre el lenguaje y los juicios), de la psicología profunda (sus trabajos sobre psicología experimental) como de la axiología (sus trabajos sobre el juicio de preferencia).

Nació y se crió en el seno de una familia ilustre marcada por el romanticismo social. Su tío el poeta Clemens Maria Brentano(1778-1842) y su tía Bettina von Arnim(1785-1859) se encontraban entre los más importantes escritores del romanticismo alemán y su hermano, Lujo Brentano, se convirtió en un experto en economía social. De su madre recibió una profunda fe y formación católicas. Estudió matemática, filosofía y teología en las universidades de Múnich, Würzburg, Berlín, y Münster. Siguió los cursos sobre Aristóteles de F. Trendelemburg Tras doctorarse con un estudio sobre Aristóteles en 1862,Sobre los múltiples sentidos del ente en Aristóteles, se ordenó sacerdote católico de la orden dominica en 1864. Dos años más tarde presentó en la Universidad de Würzburg, al norte de Baviera, su escrito de habilitación como catedrático, La psicología de Aristóteles, en especial su doctrina acerca del “nous poietikos”. En los años siguientes dedicó su atención a otras corrientes de filosofía, e iba creciendo su preocupación por la situación de la filosofía de aquella época en Alemania: un escenario en el que se contraponían el empirismo positivista y el neokantismo. En ese periodo estudió con profundidad a John Stuart Mill y publicó un libro sobre Auguste Comte y la filosofía positiva. La Universidad de Würzburg le nombró profesor extraordinario en 1872.

Sin embargo, en su interior se iban planteando problemas de otro género. Se cuestionaba algunos dogmas de la Iglesia católica, sobre todo el dogma de la Santísima Trinidad. Y después de que el Concilio Vaticano I de 1870 proclamara el dogma de la infalibilidad papal, Brentano decidió en 1873 abandonar su sacerdocio. Sin embargo, para no perjudicar más a los católicos alemanes —ya de suyo hostigados hasta llegar a huir en masa al Volga ruso por la “Kulturkampf” de Bismarck — renunció voluntariamente a su puesto de Würzburg, pero al mismo tiempo, se negó a unirse a los cismáticos “viejos católicos”. Pero sin embargo este alejamiento existencial de la Iglesia no supuso un alejamiento del pensamiento profundo de la Iglesia pues en varios de sus trabajos y en forma reiterada afirmó siempre que: «Hay una ciencia que nos instruye acerca del fundamento primero y último de todas las cosas, en tanto que nos lo permite reconocer en la divinidad. De muchas maneras, el mundo entero resulta iluminado y ensanchado a la mirada por esta verdad, y recibimos a través de ella las revelaciones más esenciales sobre nuestra propia esencia y destino. Por eso, este saber es en sí mismo, sobre todos los demás, valioso. (…) Llamamos a esta ciencia Sabiduría, Filosofía primera, Teología» (Cfr.: Religion und Philosophie, pp.72-73. citado por Sánchez-Migallón).

Se desempeñó luego como profesor en Viena durante veinte años (entre 1874 y 1894), con algunas interrupciones. Franz Brentano fue amigo de los espíritus más finos de la Viena de esos años, entre ellos Theodor Meynert, Josef Breuer, Theodor Gomperz (1832-1912). En 1880 se casó con Ida von Lieben, la hermana de Anna von Lieben, la futura paciente de Sigmund Freud. Indiferente a la comida y la vestimenta, jugaba al ajedrez con una pasión devoradora, y ponía de manifiesto un talento inaudito para los juegos de palabras más refinados, En 1879, con el seudónimo de Aenigmatis, publicó una compilación de adivinanzas que suscitó entusiasmo en los salones vieneses y dio lugar a numerosas imitaciones. Esto lo cuenta Freud en un libro suyo El chiste.

En la Universidad de Viena tuvo como alumnos a Sigmund Freud, Carl Stumpf y Edmund Husserl, Christian von Ehrenfels, introductor del término Gestalt (totalidad), y, discrepa y rechaza la idea del inconsciente descrita y utilizada por Freud. Fue un profesor carismático, Brentano ejerció una fuerte influencia en la obra de Edmund Husserl, Alois Meinong (1853-1921), fundador de la teoría del objeto, Thomas Masaryk (1859-1937) KasimirTwardowski, de la escuela polaca de lógica y Marty Antón, entre otros, y por lo tanto juega un papel central en el desarrollo filosófico de la Europa central en principios del siglo XX. En 1873, el joven Sigmund Freud, estudiante en la Universidad de Viena, obtuvo su doctorado en filosofía bajo la dirección de Brentano.

El impulso de Brentano a la psicología cognitiva es consecuencia de su realismo. Su concepción de describir la conciencia en lugar de analizarla, dividiéndola en partes, como se hacía en su época, dio lugar a la fenomenología, que continuarían desarrollando Edmund Husserl (1859-1938), Max Scheler (1874-1928), Martín Heidegger (1889-1976), Maurice Merleau-Ponty (1908-1961), además de influenciar sobre el existencialismo de Jean-Paul Sartre (1905-1980) con su negación del inconsciente.

En 1895, después de la muerte de su esposa, dejó Austria decepcionado, en esta ocasión, publicó una serie de tres artículos en el periódico vienés Die Neue Freie Presse : Mis últimos votos por Austria, en la que destaca su posición filosófica, así como su enfoque de la psicología, pero también criticó duramente la situación jurídica de los antiguos sacerdotes en Austria. In 1896 he settled down in Florence where he got married to Emilie Ruprecht in 1897. En 1896 se instaló en Florencia, donde se casó con Emilie Ruprecht en 1897. Vivió en Florencia casi ciego y, a causa de la primera guerra mundial, cuando Italia entra en guerra contra Alemania, se traslada a Zurich, donde muere en 1917.

Los trabajos que publicaron sus discípulos han sido los siguientes según el orden de su aparición: La doctrina de Jesús y su significación permanente; Psicología como ciencia empírica, Vol. III; Ensayos sobre el conocimiento, Sobre la existencia de Dios; Verdad y evidencia; Doctrina de las categorías, Fundamentación y construcción de la ética; Religión y filosofía, Doctrina del juicio correcto; Elementos de estética; Historia de la filosofía griega; La recusación de lo irreal; Investigaciones filosóficas acerca del espacio, del tiempo y el continuo; La doctrina de Aristóteles acerca del origen del espíritu humano; Historia de la filosofía medieval en el Occidente cristiano; Psicología descriptiva; Historia de la filosofía moderna, Sobre Aristóteles; Sobre “Conocimiento y error” de Ernst March.

Lineamientos de su pensamiento

Todo el mundo sabe, al menos el de la filosofía, que no se puede realizar tal actividad sino es en diálogo con algún clásico. Es que los clásicos son tales porque tienen respuestas para el presente. Hay que tomar un maestro y a partir de él comenzar a filosofar. Brentano lo tuvo a Aristóteles, el que le había enseñado Federico Trendelenburg (1802-1872), el gran estudioso del Estagirita en la primera mitad de siglo XIX.

En su tesis doctoral, Sobre los múltiples significados del ente según Aristóteles, que tanto influenciara en Heidegger, distingue cuatro sentidos de “ente” en el Estagirita: el ente como ens per accidens o lo fortuito; el ente en el sentido de lo verdadero, con su correlato, lo no-ente en el sentido de lo falso; el ente en potencia y el ente en acto; y el ente que se distribuye según la sustancia y las figuras de las categorías. De esos cuatro significados, el veritativo abrirá en Brentano el estudio de la intencionalidad. Pero al que dedica con diferencia mayor extensión es al cuarto, el estudio de la sustancia y su modificación, esto es, a las diversas categorías. Esto se debe, en parte, a las discusiones de su tiempo en torno a la metafísica aristotélica. En ellas toma postura defendiendo principalmente dos tesis: primera, que entre los diferentes sentidos categoriales del ente se da una unidad de analogía, y que ésta significa unidad de referencia a un término común, la sustancia segunda, que precisamente esa unidad de referencia posibilita en el griego deducir las categorías según un principio.

Investigó las cuestiones metafísicas mediante un análisis lógico-lingüístico, con lo que se distinguió tanto de los empiristas ingleses como del kantismo académico. Ejerciendo una gran influencia sobre algunos miembros del Círculo de Viena.

En 1874 publica su principal obra Psicología como ciencia empírica, de la que editará tres volúmenes, donde realiza su principal aporte a la historia de la filosofía, su concepto de intencionalidad de la conciencia que tendrá capital importancia para el desarrollo posterior de la fenomenología a través de Husserl y de Scheler.

Sólo lo psíquico es intencional, esto es, pone en relación la conciencia con un objeto. Esta llamada «tesis de Brentano», que hace de la intencionalidad la característica de lo psíquico, permite entender de un modo positivo, a diferencia de lo que no lograba la psicología de aquella época, los fenómenos de conciencia que Brentano distingue entre representaciones, juicios teóricos y juicios prácticos o emotivos (sentimientos y voliciones).

Todo fenómeno de conciencia es o una representación de algo, que no forzosamente ha de ser un objeto exterior, o un juicio acerca de algo. Los juicios o son teóricos, y se refieren a la verdad y falsedad de las representaciones (juicios propiamente dichos), y su criterio es la evidencia y de ellos trata la epistemología y la lógica; o son prácticos, y se refieren a la bondad o a la maldad, la corrección o incorrección, al amor y al odio (fenómenos emotivos), y su criterio es la «preferencia», la valoración, o «lo mejor», y de ellos trata la ética. Al estudio de la intencionalidad de la conciencia lo llama psicología descriptiva o fenomenología.

En 1889 dicta su conferencia en Sociedad Jurídica de Viena “De la sanción natural de lo justo y lo moral” que aparece publicada luego con notas que duplican su extensión bajo el título de: El origen del conocimiento moral”, trabajo que publicado en castellano en 1927, del que dice Ortega y Gasset, director de la revista de Occidente que lo publica, “Este tratadito, de la más auténtica filosofía, constituye una de las joyas filosóficas que, como “El discurso del método” o la “Monadología”… Puede decirse que es la base donde se asienta la ética moderna de los valores”.

Comienza preguntándose por la sanción natural de lo justo y lo moral. Y hace corresponder lo bueno con lo verdadero y a la ética con la lógica. Así, lo verdadero se admite como verdadero en un juicio, mientras que lo bueno en un acto de amor. El criterio exclusivo de la verdad del juicio es cuando, éste, se presenta como evidente. Pero, paradójicamente, lo evidente, va a sostener siguiendo a Descartes, es el conocimiento sin juicio.

Lo bueno es el objeto y mi referencia puede ser errónea, de modo que mi actitud ante las cosas recibe la sanción de las cosas y no de mí. Lo bueno es algo intrínseco a los objetos amados.

Que yo tenga amor u odio a una cosa no prueba sin más que sea buena o mala. Es necesario que ese amor u odio sean justos. El amor puede ser justo o injusto, adecuado o inadecuado. La actitud adecuada ante una cosa buena es amarla y ante una cosa mala, el odiarla. “Decimos que algo es bueno cuando el modo de referencia que consiste en amarlo es el justo. Lo que sea amable con amor justo, lo digno de ser amado, es lo bueno en el más amplio sentido de la palabra»”.

La ética encuentra su fundamento, según Brentano, en los actos fundados de amor y odio. Y actos fundados quiere decir, que el objeto de ser amado u odiado es digno de ser amado u odiado. El “ajuste” entre el acto de amor u odio al objeto mismo en ética, es análogo, según Brentano, a la “adecuación” que se da en el juicio verdadero entre predicado y objeto.

La diferencia que existe entre uno y otro juicio (el predicamental y el práctico) es que en el práctico puede darse un antítesis (amar un objeto y , pasado el tiempo, odiarlo) mientras que en el lógico o de representación, no.

Dos meses después el 27 de marzo de 1889 dicta su conferencia Sobre el concepto de verdad, ahora en la Sociedad filosófica de Viena. Esta conferencia es fundamental por varios motivos: a) muestra el carácter polémico de Brentano, tanto con el historiador de la filosofía Windelbang (1848-1915) por tergiversar a Kant, como a Kant, “cuya filosofía es un error, que ha conducido a errores mayores y, finalmente, a un caos filosófico completo” (cómo no lo van a silenciar luego, en las universidades alemanas, al viejo Francisco). b) Nos da su opinión sin tapujos sobre Aristóteles diciendo: “Es el espíritu científico más poderoso que jamás haya tenido influencia sobre los destinos de la humanidad”. c) Muestra y demuestra que el concepto de verdad en Aristóteles “adecuación del intelecto y la cosa” ha sido adoptada tanto por Descartes como por Kant hasta llegar a él mismo. Pero que dicho concepto encierra un grave error y allí él va a proponer su teoría del juicio.

Diferencia entre juicios negativos y juicios afirmativos. Así en los juicios negativos como: “no hay dragones”, no hay concordancia entre mi juicio y la cosa porque la cosa no existe. Mientras que sólo en los juicios afirmativos, cuando hay concordancia son verdaderos.

“el ámbito en que es adecuado el juicio afirmativo es el de la existencia y el del juicio negativo, el de lo no existente”. Por lo tanto “un juicio es verdadero cuando afirma de algo que es, que es; y de algo que no es, niega que sea”.

En los juicios negativos la representación no tiene contenido real, mientras que la verdad de los juicios está condicionada por el existir o ser del la cosa (Sein des Dinges). Así, el ser de la cosa, la existencia es la que funda la verdad del juicio. El “ser del árbol” es lo que hace verdadero al juicio: “el árbol es”.

Y así lo afirma una y otra vez: “un juicio es verdadero cuando juzga apropiadamente un objeto, por consiguiente, cuando si es, se dice que es; y sino es, se dice que no es”.(in fine).

Y desengañado termina afirmando que: “Han transcurrido dos mil años desde que Aristóteles investigó los múltiples sentidos del ente, y es triste, pero cierto, que la mayoría no hayan sabido extraer ningún fruto de sus investigaciones”.

Su propuesta es, entonces, discriminar claramente en el juicio “el ser de la cosa” que equivalente a ”la existencia”, de “la cosa” también denominada por Brentano ”lo real”. Existir o existencia, y ser real o realidad es la dupla de pares que expresan el “ser verdadero” y el “ser sustancial” respectivamente, que él se ocupó de estudiar en su primer trabajo sobre el ente en Aristóteles.

Conviene repetirlo, existir, existencia y ser verdadero vienen a expresar lo mismo: la mostración del ente al pensar. Y la cosa, lo real, el ser sustancial expresan lo mismo: el ente en sí mismo. Vemos como Brentano, liquida definitivamente “la cosa en sí” kantiana.

Aun cuando claramente Brentano muestra como “el objeto no tiene un existencia en la realidad independiente, o más allá del sujeto, sino que existe en tanto que hay un acto psíquico”, y este es el gran aporte a la psicología de Brentano.

Metafísicamente, todo lo que es, es. Y se nos dice también en el sentido de lo verdadero. En una palabra el ser de la cosa se convierte con la verdadero, sin buscarlo Brentano retorna al viejo ens et verum convertuntur de la teoría de los transcendentales del ente.

Y así da sus dos últimos y más profundos consejos: “Por último, no estaremos tentados nunca de confundir, como ha ocurrido cada vez más, el concepto de lo real y el de lo existente”. Y “podríamos extraer de nuestra investigación otra lección y grabarla en nuestras mentes para siempre…el medio definitivo y eficaz (para realizar un juicio verdadero) consiste siempre en una referencia a la intuición de lo individual de la que se derivan todos nuestros criterios generales”.

No podemos no recordar acá, por la coincidencia de los conceptos y consejos, aquella que nos dejara el primer metafísico argentino, Nimio de Anquín (1896-1979),: “Ir siembre a la búsqueda del ser singular en su discontinuidad fantasmagórica. Ir al encuentro con las cosas en su individuación y potencial universalidad”.

Franz Brentano es el verdadero fundador de la metafísica realista contemporánea que luego continuarán, con sus respectivas variantes, Husserl, Scheler, Hartmann y Heidegger.

En el mismo siglo XIX, a propósito de la encíclica Aeterni Patris de 1879 se dará el florecimiento del tomismo, sostenedor también, pero de otro modo, de una metafísica realista.

Siempre nos ha llamado la atención que los mejores filósofos españoles del siglo XX se hayan prestado a ser traductores de los libros de Brentano: José Gáos de su Psicología, Manuel García Morente de su Origen del conocimiento moral, Xavier Zubiri de El provenir de la filosofía, Antonio Millán Puelles de Sobre la existencia de Dios. Y siempre nos ha llamado la atención que no se enseñara Brentano en la universidad.

El problema de Brentano es que ha sido “filosóficamente incorrecto”, pues realizó una crítica feroz y terminante a Kant y los kantianos y eso la universidad alemana no se lo perdonó. Realizó una crítica furibunda a la escuela escolástica católica y eso no se le perdonó. Incluso se levantaron invectivas denunciándolo, que al criticar el concepto de analogía del ser, adoptó él, el de equivocidad. Un siglo después, el erudito sobre Aristóteles, Pierre Aubenque, vino a negar en un libro memorable y reconocido universalmente, Le problème de l´être chez Aristote (1962) la presencia en los textos del Estagirita del concepto de analogía.(si detrás de esto no está la sombra del viejo Francisco, que no valga).

Polemizó con Zeller, con Dilthey, con Herbart, con Sigwart. Criticó, como ya dijimos, a Kant, Descartes, Hume, Hegel, Aristóteles, y a Überweg. No dejó títere con cabeza. Sólo le faltó pelearse con Goethe. Fue criticado por Freud, que se portó con él, como el zorro en el monte, que con la cola borra las huellas por donde anda. Husserl no solo tomó y usufructuó el concepto de intencionalidad sino también el de “retención” que es copia exacta de concepto bentaniano de “asociación original”, pero eso quedó bien silenciado.

Filosóficamente, esta oposición por igual al idealismo kantiano y a la escolástica de su tiempo le valió el silencio de los manuales y la marginalización de su obra de las universidades. Quien quiera comprender en profundidad y conocer las líneas de tensión que corren debajo de las ideas de la filosofía del siglo XX, tiene que leer, forzosamente a Brentano, sino se quedará como la mayoría de los profesores de filosofía, en Babia.

El es el testigo irrenunciable de la ligazón profunda que existe en el desarrollo de la metafísica que va desde Aristóteles, pasa por Tomás de Aquino y Duns Escoto, sigue con él y termina en Heidegger. No al ñudo, el filósofo de Friburgo, realizó su tesis doctoral sobre La doctrina de las categorías y del significado pensando que era de Duns Escoto, cuando después se comprobó que el texto de la Gramática especulativa sobre el que trabajó, pertenecía a Thomas de Erfurt (fl.1325).

La invitación está hecha, seguro que algún buen profesor o algún inquieto investigador recoge el guante.

Nota: Bibliografía de F. Brentano en castellano

Psicología (desde el punto de vista empírico), Revista de Occidente, Madrid, 1927

Sobre la existencia de Dios, Rialp, Madrid 1979.

Sobre el concepto de verdad, Ed. Complutense, Madrid, 1998

El origen del conocimiento moral, Revista de Occidente, Madrid 1927. (Tecnos, Madrid 2002).

Breve esbozo de una teoría general del conocimiento, Ed. Encuentro, Madrid 2001.

El porvenir de la filosofía, Revista de Occidente, Madrid 1936

Aristóteles y su cosmovisión, Labor, Barcelona 1951.

Sobre los múltiples significados del ente según Aristóteles, Ed. Encuentro, Madrid 2007

Razones del desaliento en filosofía, Ed. Encuentro, Madrid, 2010

Existen además, en castellano, trabajos de consulta valiosos sobre su filosofía como los debidos a los profesores Mario Ariel González Porta y Sergio Sánchez-Migallón Granados.

III- Max Scheler y el sentido de la realidad

El tema de cómo saber que la realidad exterior existe no ha sido un asunto menor para la filosofía moderna. En general y desde sus primeros tiempos la filosofía ha desconfiado siempre de los sentidos externos: ya Heráclito sostenía, tirado en la playa: el sol es grande como mi pie.

En la modernidad Descartes: “he experimentado varias veces que los sentidos son engañosos, y es prudente, no fiarse nunca por completo de quienes nos han engañado una vez.”

Max Scheler trata en tema, específicamente, en una meditación titulada La metafísica de la percepción y la realidad que estuvo incluida en uno de sus últimos trabajos Erkenntnis und Arbeit (Conocimiento y trabajo) de 1926.

Es sabido que el fundador de la fenomenología, Edmundo Husserl (1859-1938), maestro de Scheler, se propuso construir una filosofía como ciencia estricta y para ello sostuvo: zu den Sachen selbst (ir a las cosas mismas) que son las que aparecen a la conciencia. Esta conciencia es una trama de relaciones intencionales, pues la conciencia tiende a objetos, in-tendere. Y para ello Husserl no ha querido plantearse la existencia de objetos reales como existencias en sí y ha recurrido a la epoché, a la puesta entre paréntesis de la existencia en sí de las cosas. Limitándose a la descripción de las estructuras y de los contenidos intencionales de la conciencia. De modo tal que exista o no exista la realidad, ese no es un problema de la fenomenología de Husserl. En una palabra, Husserl postergó el tema o problema de “la cosa en sí” y no se animó a tomar partido, cosa que sí va a hacer su discípulo.

Max Scheler va a seguir con el método de fenomenológico de su maestro y su ontología como teoría general de los objetos pertenecientes a distintas esferas: reales (naturales y culturales), ideales, valores y metafísicos. Destacándose sobre todo con brillantes estudios sobre los objetos culturales y axiológicos. Pero al mismo tiempo se va a modificar o completar el mismo método.

Las categorías que son las que acompañan a cada tipo de ser, no son como en Aristóteles producto de la predicación o formas de decir el objeto y que previamente son modos de existencia. No, para la fenomenología las categorías son modos de presentación “en mi conciencia” de tales objetos y no de existencia fuera de mi.

Cuando Scheler en la plenitud de su capacidad filosófica aborda el tema concreto del trabajo, el objeto propio del mismo lo lleva a dar un paso más allá que su maestro. Mientras que para Husserl, sobre todo para el primero, el existir fuera de mi conciencia de las cosas es solo presuntiva. Presumimos que las cosas pueden tener un ser en sí mismas, pero no estamos tan seguros. En sus últimas conclusiones, niega esta existencia presunta (Cfr. Ideas), mientras que para Scheler podemos tener un saber cierto de esa realidad en sí.

Y lo afirma en forma tajante: “los centros de resistencia del mundo, tal cual han sido dados a la experiencia práctica de la voluntad de trabajo y del actuar en el mundo, han confirmado su eficacia en la relación práctica entre el hombre y el mundo”.

De modo tal que solamente en el transcurso del trabajo ejercido sobre el mundo el hombre aprende a conocer el mundo objetivo y causal, aquel que se da en el espacio y en el tiempo. El trabajo y no la contemplación es “la raíz más esencial de toda ciencia positiva, de toda intuición, de todo experimento”.

El hombre posee además otra posibilidad de conocimiento a través de la percepción sensorial que se expresa en el conocimiento filosófico. Este conocimiento es de dos tipos: a) el de las esencias al que se llega a través “del asombro, la humildad y el amor espiritual hacia lo esencial” mediante la reducción fenomenológica de la existencia en sí de los objetos y b) de los instintos, impulsos y fuerzas que viene de las imágenes a la que se llega “por la entrega dionisíaca en la identificación con el impulso cuya parte es también nuestro ser impulsivo”.

Y concluye Scheler: “Pero el verdadero conocimiento filosófico sólo nace en la máxima tensión entre ambas actitudes y a través de la superación de esta tensión, en la unidad de la persona.”

La existencia de un mundo real es preexistente a todo lo demás, tanto a la concepción natural del mundo cuanto cualidades de la percepción. Está ahí y preexiste a los dominios de la mundanidad interior y exterior, a la existencia de las categorías.

De este mundo sabemos por “la resistencia” que nos ofrece a la actividad sobre él. “Ser real es mas bien, ser resistencia frente a la espontaneidad originaria, que es una y la misma en todas las especies del querer y del atender.”

Este ser real existe antes de todo pensar y percibir. El ser real puede preexistir también a todos los actos intelectuales, cuyo único correlato es la “consistencia” y nunca la existencia.

La existencia esta dada porque el ser real es algo preexistente al conocer y que solo sabemos de él por el impulso de resistencia que nos ofrece cuando actuamos sobre él.

En el fondo el ser real es “ser querido” y no “pensado” a través del fundamento del mundo y el principio de la experiencia de la resistencia es un acto volitivo. Scheler se da cuento y menta allí la sombra de Maine de Biran y de Schopenhauer.

Y termina enunciando las cuatro leyes que rigen la realidad y que preexisten a todo lo que aparece en las esferas de los objetos: 1) la realidad de algo “Real Absoluto”, esperado como posible. 2) la realidad del prójimo y de la comunidad, como el tú y el nosotros. 3) el mundo exterior como ser real de algo que existe y 4) la realidad del ser corporal, vivido como propio.

Estas cuatro leyes nos vienen a mostrar el principio fundamental de toda la filosofía de Scheler, aquel que aplica a todas las esferas del ser y los objetos según la cual lo real, lo resistente, lo que existe en sí, es mayor y surge allí donde nuestro dominio de las cosas es menor. Así, el domino del hombre es mínimo sobre el ser absoluto en cambio nuestro dominio es máximo sobre la máquina, que es nuestro producto. Frente a las personas nuestro dominio es muy limitado pero sobre los animales es mayor. “El dominio es infinitamente menor sobre lo viviente que sobre lo inanimado”

Esto le permite establecer una jerarquía en las esferas que luego va a aplicar en su axiología y su ética. Y allí nos va a sorprender cuando enuncia que el espíritu carece de la fuerza y energía para obrar, pues toda la energía procede del impulso vital. Así, éste se espiritualiza sublimándose y el espíritu opera vivificándose. Pero solo la vida puede poner en actividad y hacer realidad en espíritu.

Breve biografía

Max Scheler (1874-1928) Hijo de un campesino bávaro luterano y madre judía, se bautiza católico en 1889. Es alumno de Simmel y Dilthey y le dirige su tesis Rudolf Eucken, quien hizo su tesis sobre el lenguaje de Aristóteles (el método de la investigación aristotélica 1872) y que había estudiado a su vez con Trendelenburg, el gran estudioso del Estagirita en el siglo XIX. En 1902 conoce a Husserl y su método fenomenológico y en 1907 al gran teólogo von Hildebrand. Por escándalos de su mujer, de la que se separa, en 1911 la universidad de Munich le retira la venia dicenti.

Prácticamente sin trabajo y viviendo de cursos privados y de la ayuda de sus amigos, Scheler produce sus mejores y más profundas obras. Este período, conocido como el del “Nietzsche católico”, dura hasta 1924, año en que se separa de su segunda mujer, se casa con una alumna y se aleja del catolicismo. Conrad Adenauer le devuelve la venia docente y se reintegra a la universidad. A partir de sus publicaciones de 1927 y 1928, año de su fallecimiento, Scheler cae en una especie panenteísmo. El puesto del hombre en el cosmos, su última obra, es ejemplo emblemático de ello.

Bibliografía en castellano

(1912) El resentimiento en la moral, de J. Gaos, Madrid, 1927; Buenos Aires, 1938; Edición de José Maria Vegas, Madrid, 1992; Caparros Editores, S. L. Madrid, 1993.

(1913) Etica, nuevo ensayo de fundamentacion de un personalismo etico. Traducción de de Hilario Rodríguez Sanz. Introducción de Juan Miguel Palacios. Tercera editción revisada. Caparrós Editores (Collección esprit, 45). Madrid, 2001, 758 págs.

(1916-23) Amor y conocimiento, di A. Klein, Buenos Aires, Sur, 1960.

De lo eterno en el hombre. La esencia y los atributos de Dios, de J. Marias, Madrid, 1940.

(1917) La esencia de la filosofía y la condición moral del conocer filosófico, de E.Tabernig de Pucciarelli e I. M. de Brugger, Buenos Aires, 1958, 1962.

(1913-22) Esencia y formas de la simpatía, de J. Gaos, Buenos Aires, 1923, 1943. Íngrid Vendrell Ferran revisó la traducción, 2005. Ediciones Sígueme Salamanca, España.

(1912) Los ídolos del autoconocimiento. Traducción e introdución de Íngrid Vendrell Ferran. Ed. Sígueme. Salamanca, 2003

(1914) Sobre el pudor y el sentimiento de vergüenza. Traducción e introducción de Íngrid Vendrell Ferran. Ed. Sígueme. Salamanca, 2004.

Sociologia del saber, de J. Gaos, Madrid, 1935.

(1928) El saber y la cultura, de J. Gomez, Madrid 1926, 1934; Buenos Aires, 1939; Santiago, 1960.

La idea del hombre y la historia, Madrid, 1926, e Buenos Aires, 1959.

(1928) El puesto del hombre en el cosmos, de V. Gaos, Madrid, 1929, 1936. Nueva traducción por V. Gómez. Introducción de W. Henckmann. Barcelona: Alba 2000.

El porvenir del hombre, Madrid 1927.

(1921) La idea de paz y el pacifismo, de Camilo. Santé, Buenos Aires, 1955.

(1911) Muerte y supervivencia. Traducción de Xavier Zubiri. Presentatión de Miguel Palacios. Ediciones Encuentro (opuscula philosophica, 3), Madrid, 2001, 93 págs.

(1914-16)Ordo Amoris, Traducción de Xavier Zubiri. Edición de Juan Miguel Palacios. Segunda edición. Caparrós Editores (Collección Esprit, 23), Madrid, 2001, 93 págs.

(1911-21) El Santo, el genio, el heroe, de E. Tabernig, Buenos Aires, 1961.

(1926) Conocimiento y trabajo, de Nelly Fortuna, Ed. Nova, Buenos Aires, 1969

(1918-1927) Metafísica de la libertad, E. Nova, Buenos Aires, 1960

(*) alberto.buela@gmail.com

www.disenso.org

arkegueta, mejor que filósofo

Universidad Tecnológica Nacional –Argentina-

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

Sieburg hörte nicht auf, den Mangel an Sittlichkeit und Höflichkeit in der Gesellschaft als Wucherungen anzusehen, zu denen nur westliche Demokratien als Mekka der Vulgarität und der Bequemlichkeit des Einzelnen in der Lage seien. Er beschrieb zudem das Dilemma, ohne Traditionsbewusstsein dem Zeitgeist zu verfallen und so die Vergangenheit nicht verarbeiten zu können, der man sich nach 1945 nur schwerlich stellen konnte. Stattdessen gehe der Mensch in einer anonymen Menge unter, der eine einigende Idee fehle und in der soziale Bindungen kaum noch durch Familie und Fleiß und vielmehr über staatliche Transferleitungen erlogen werden.

Sieburg hörte nicht auf, den Mangel an Sittlichkeit und Höflichkeit in der Gesellschaft als Wucherungen anzusehen, zu denen nur westliche Demokratien als Mekka der Vulgarität und der Bequemlichkeit des Einzelnen in der Lage seien. Er beschrieb zudem das Dilemma, ohne Traditionsbewusstsein dem Zeitgeist zu verfallen und so die Vergangenheit nicht verarbeiten zu können, der man sich nach 1945 nur schwerlich stellen konnte. Stattdessen gehe der Mensch in einer anonymen Menge unter, der eine einigende Idee fehle und in der soziale Bindungen kaum noch durch Familie und Fleiß und vielmehr über staatliche Transferleitungen erlogen werden.

E tuttavia Munsalvaetsche è solo uno dei tanti termini criptici di cui abbonda il testo di Wolfram, termini e nomi costruiti secondo necessità d’ordine simbolico. Si è sostenuto che Herzeloyde, Condwiramurs, Gahmuret, Shoye de la Kurte, Feirefiz, Terdelaschoye, etc., corrispondano ad esempi di virtù cavalleresche, a particolari ideali raccomandati agli ascoltatori dei racconti, a sentimenti capaci di rendere universale il dramma vissuto da questo o quel protagonista. In realtà, il tecnicismo e lo stesso valore ermeneutico con il quale si caratterizzano i tanti nomi dei personaggi, dei luoghi o delle ambientazioni, risponde a necessità di un ordine completamente diverso da quello di un semplice ideale cavalleresco. Nell’intento di Wolfram si tratta di vere e proprie personificazioni di “entità spirituali” tese a determinare comportamenti, “modi di essere” che incidono nelle profondità dell’anima umana, trasformazioni interiori che scaturiscono da una dimensione superiore, precedente a quella del mondo fenomenico, “forme formanti” che rivelano modalità dell’”agire divino” nella storia, “epifanie” che indirizzano verso il significato veritiero dell’essere cosmico ed umano.

E tuttavia Munsalvaetsche è solo uno dei tanti termini criptici di cui abbonda il testo di Wolfram, termini e nomi costruiti secondo necessità d’ordine simbolico. Si è sostenuto che Herzeloyde, Condwiramurs, Gahmuret, Shoye de la Kurte, Feirefiz, Terdelaschoye, etc., corrispondano ad esempi di virtù cavalleresche, a particolari ideali raccomandati agli ascoltatori dei racconti, a sentimenti capaci di rendere universale il dramma vissuto da questo o quel protagonista. In realtà, il tecnicismo e lo stesso valore ermeneutico con il quale si caratterizzano i tanti nomi dei personaggi, dei luoghi o delle ambientazioni, risponde a necessità di un ordine completamente diverso da quello di un semplice ideale cavalleresco. Nell’intento di Wolfram si tratta di vere e proprie personificazioni di “entità spirituali” tese a determinare comportamenti, “modi di essere” che incidono nelle profondità dell’anima umana, trasformazioni interiori che scaturiscono da una dimensione superiore, precedente a quella del mondo fenomenico, “forme formanti” che rivelano modalità dell’”agire divino” nella storia, “epifanie” che indirizzano verso il significato veritiero dell’essere cosmico ed umano.

Il y a 75 ans, le 8 mai 1936, Oswald Spengler, philosophe des cultures et esprit universel, est mort. Si l’on lit aujourd’hui les pronostics qu’il a formulés en 1918 pour la fin du 20ème siècle, on est frappé de découvrir ce que ce penseur isolé a entrevu, seul, dans son cabinet d’études, alors que le siècle venait à peine de commencer et que l’Allemagne était encore un sujet souverain sur l’échiquier mondial et dans l’histoire vivante, qui était en train de se faire.

Il y a 75 ans, le 8 mai 1936, Oswald Spengler, philosophe des cultures et esprit universel, est mort. Si l’on lit aujourd’hui les pronostics qu’il a formulés en 1918 pour la fin du 20ème siècle, on est frappé de découvrir ce que ce penseur isolé a entrevu, seul, dans son cabinet d’études, alors que le siècle venait à peine de commencer et que l’Allemagne était encore un sujet souverain sur l’échiquier mondial et dans l’histoire vivante, qui était en train de se faire.  “Dans le tourbillon des innombrables tonalités, perceptibles sur notre planète, les consonances et les dissonances sont l’aridité sublime des déserts, la majesté des hautes montagnes, la mélancolie que nous apportent les vastes landes, les entrelacs mystérieux des forêts profondes, le bouillonement des côtes baignées par la lumière des océans. C’est en eux que le travail originel de l’homme s’est incrusté ou s’est immiscé sous l’impulsion du rêve”.

“Dans le tourbillon des innombrables tonalités, perceptibles sur notre planète, les consonances et les dissonances sont l’aridité sublime des déserts, la majesté des hautes montagnes, la mélancolie que nous apportent les vastes landes, les entrelacs mystérieux des forêts profondes, le bouillonement des côtes baignées par la lumière des océans. C’est en eux que le travail originel de l’homme s’est incrusté ou s’est immiscé sous l’impulsion du rêve”.

Since 1945 Western nations have witnessed a dramatic reduction in the variety of positions in political theory and jurisprudence. Political argument has been virtually reduced to contests within liberal-democratic theory. Even radicals now take representative democracy as their unquestioned point of departure. There are, of course, some benefits following from this restriction of political debate. Fascist, Nazi and Stalinist political ideologies are now beyond the pale. But the hegemony of liberal-democratic political agreement tends to obscure the fact that we are thinking in terms which were already obsolete at the end of the nineteenth century.

Since 1945 Western nations have witnessed a dramatic reduction in the variety of positions in political theory and jurisprudence. Political argument has been virtually reduced to contests within liberal-democratic theory. Even radicals now take representative democracy as their unquestioned point of departure. There are, of course, some benefits following from this restriction of political debate. Fascist, Nazi and Stalinist political ideologies are now beyond the pale. But the hegemony of liberal-democratic political agreement tends to obscure the fact that we are thinking in terms which were already obsolete at the end of the nineteenth century.