Ex: https://rabehl.wordpress.com/

Ein Anfall

Im Haushaltsausschuss des Bundestages verlor Finanzminister Schäuble in den letzten Novembertagen 2012 jeden Anstand. In Brüssel und in Paris hatte er sich darauf eingelassen, dass die Bundesrepublik erneut Milliardenbeträge nach Griechenland pumpen würde, um dort den Staatsbankrott zu vermeiden. Das überschuldete Griechenland, ein Mafiastaat, der jede moderne Verwaltung und Aufsicht vermissen liess, eine Gesellschaft, unterentwickelt, ohne produktive Industrie und Landwirtschaft, strategischer Militärstützpunkt der NATO, heruntergekommerner Tourismusort, unterschied sich vom technologisch und industriell hochgerüsteten Zentraleuropa grundsätzlich. Hinzu kam, dass die vergangenen Militärdiktaturen und eine von der Mafia gesteuerte „Demokratisierung“ vermieden, den Sozial- und Militärstaat mit einer modernen Steuergesetzgebung und rationalen Bürokratie zu verbinden. Die Kontrollen durch das Parlament blieben mangelhaft. Selbst die europäischen Auflagen und Rechtsdirektiven wurden missachtet. Ein aufgeblasener Apparat diente als Selbstbedienungsladen der Staatsangestellten, der Spekulanten und des organisierten Verbrechens. Der Parasitismus der unterschiedlichen sozialen Schichten wurde sogar noch gefördert und die EU Zuschüsse grosszügig verteilt. Gewinne und Profite wurden nicht registriert und versteuert und eine masslose Verschuldung eingeleitet. Sie wurden über landeseigene und internationale Privat- und Kreditbanken, Hedgfonds und über die europäische Umverteilungen finanziert. Alle lebten in Saus und Braus.

In Griechenland wurden zu hohe Renten und Löhne gezahlt und zugleich riesige Gewinne realisiert. Sie wurden nicht erwirtschaftet, sondern über Kredite und Schulden aufgebracht. Nach den Gesichtpunkten der industriellen Durchschnittsproduktivität und nach dem Zustand von Staat und Recht, lag Griechenland irgendwo in Nordafrika. Dieser Kontinent hatte, bezogen auf Technologie, Arbeitsteilung, Produktion, Verkehr, Recht, Verwaltung, Lug und Trug den Balkan, Süditalien, Südspanien und Portugal erreicht. Der Überbau von Staat und Politik als ein Gebilde aus Korruption, Parasitismus, Vetternwirtschaft, Plünderung hatte mit Zentraleuropa nichts gemeinsam. Riesensummen wurden aus diesen Industriestaaten in das europäische „Afrika“ transferiert. Von dort wurden sie als billige Beute von den reichen und einflussreichen Familien in die Schweiz auf Geheimkonten gebracht oder an die nordamerikanischen Spekulanten weitergereicht. Sie hatten den griechischen Staat mit Krediten ausgeholfen. Die griechischen Regierungen verfälschten in der Vergangenheit die Bilanzen und den Stand der Verschuldung, um in das „Paradies“ der Europäische Union zu gelangen. Die deutschen Steuerzahler finanzierten dadurch die griechischen Betrüger und Absahner oder die nordamerikanischen Kredithaie. Ein grosser Rest wurden an die überbezahlten Staatsangestellten und Rentner bezahlt, um sie ruhig zu stellen und dem System eine demokratische Legitimation zu geben. Kein Wunder, dass in einem derartigen Milieu der Spiritualismus gedieh. Die faschistische „Morgenröte“ pendelte sich zu einer starken Partei auf. Die deutschen Steuerzahler leistete sich den Luxus, einen kranken und maroden Staat zu unterstützen, der unbedingt zu Europa gehören sollte. Diese Entscheidung wurde jedoch in USA gefällt.

Geostrategisch bildete Griechenland für diese Militärmacht einen Flugzeugträger, einen Militärstützpunkt und hielt die Meerenge der Dardanellen nach Russland unter Aufsicht. Griechenland stellte die Verbindung zur Türkei her und bildete die Brücke in den Nahen Osten. Es konnte mit dem albanischen Kosovo und Kroatien verbunden werden, die durch die amerikanischen Bombardements Serbien entrissen wurden. Es hielt die Verbindung nach Bulgarien und Rumänien, die unter nordamerikanischen Einfluss gestellt werden sollten. Griechenland schuf die Garantien für ein europäisches Mittelmeer. Es bildete eine Voraussetzung für ein „Grossisrael“, das sich gegen die arabischen Anreinerstaaten behaupten musste. Nordafrika oder die Nahoststaaten sollten militärisch und politisch dem Einfluss des islamischen Fundamentalismus entwunden werden. Sie sollten wie der Irak und Syrien einer Neuordnung unterliegen. Der zukünftige Krieg gegen den Iran benötigte die geostrategische Position Griechenlands und die finanzielle Unterstützung Deutschlands. Dieser deutsche Staat wurde von den USA angewiesen, das südeuropäische „Afrika“ und Israel zu stabilisieren. Es wurde zugleich darauf vorbereitet, in der Zukunft den Bestand der Mafiastaaten Bulgarien und Rumäniens zu gewährleisten. Frankreich entzog sich der Verpflichtung und geriet selbst in eine Finanzkrise. Deutschland sollte den geldpolitischen Hintergrund für ein „nordamerikanisches Europa“ bilden, das sich gegen Russland, gegen China und den Iran in Front brachte. Die Hauptabsatzmärkte der deutschen Wirtschaft lagen in diesen „feindlichen Regionen“ und im Gegensatz zu dem Aufmarsch wäre eine friedliche Koexistenz mit diesen Ländern notwendig. Deutschland als Wirtschaftsmacht und Griechenland als machtpolitischer Dominostein bildeten eine erzwungene Einheit. Den Deutschen wurde ein neues „Versailles“ aufgedrängt, an dem es kaputt gehen konnte. Das konnte Schäubele alles wissen. Er konnte sich den Auflagen und Befehlen der NATO und der USA schwer entwinden. Er fühlte sich inzwischen als Vertrauensmann dieser Mächte. Er hatte Schwierigkeiten, sich diesen Manipulationen zu entziehen. Die Frage stand im Raum, wie lange er diese Rolle aufrechterhalten wollte?

Der Finanzminister war innerlich erregt, denn er konnte nicht begründen, warum er der deutschen Republik derartige Zahlungen zumutete. Ihm fehlte jedes plausible Argument. Also schrie und pöbelte er. Jetzt im Ausschuss, Ende November, kommentiert durch FAZ, FR und FTD, fühlte er sich von der Linksabgeordneten Pau angegriffen und er wehrte sich gegen den SPD – Hinterbänkler aus Hamburg, der nicht einmal wusste, worum es ging, sondern für Würde und Anstand sorgen wollte. Schäubele brüllte über zehn Minuten in den Saal hinein und gab zu erkennen, dass er die Übersicht verloren hatte. Er ahnte wohl, dass die europäische Krise wie in Argentinien 2001 in einem Staatsbankrott enden konnte. Er wusste, dass er deutsche Interessen kaum noch wahrnahm. Er konnte auch die Tatsache nicht verdrängen, dass er die Ziele der NATO, der EU und der USA bediente und dadurch die staatliche Souveränität Deutschlands unterminierte. Seit Ende der achtziger Jahre hatte er sich in der Regierung Kohl als ein Mann der „Kompromisse“ bewährt. Jetzt steuerte er die Finanzpolitik der Regierung von Angela Merkel und würde den Wohlstand der Mittelklassen in Deutschland riskieren und die Armut der millionenfachen Habenichtse in dieser Gesellschaft vergrössern. Die Zahlungen an Griechenland würden die Inflation und die Steuern steigern. Er wusste, dass Europa sich auf einen Krieg zubewegte. Sehr bald musste die Bundesregierung den Einsatz deutscher Soldaten in der Türkei, in Syrien, Ägypten und im Iran rechtfertigen. Schräuble schrie seine masslose Wut heraus, denn sein unbedachtes Spiel wurde offenkundig.

Planspiele

Listen wir die einzelnen Massnahmen auf. An die wirtschaftliche Konsolidierung der südeuropäischen Staaten durch eine gezielte Entwicklungspolitik wurde in Brüssel und Berlin nie gedacht. Statt die Riesensummen für die Spekulanten, die Absahner und die Mafia zu vergeuden, wäre es durchaus sinnvoll gewesen, den Ausbau der Infrastruktur dieser Länder zu finanzieren, um eine industrielle Grundlage zu schaffen. Allerdings hätten die EU – Institutionen die Kontrolle der Investitionen übernehmen müssen, um den korrupten Poltikern der Zugriff zu entziehen. Statt Israel mit Atom- U – booten auszurüsten und Militärausgaben zu übernehmen, hätte Deutschland die israelische Wirtschaft stabilisieren können, um einen Friedensprozess des Ausgleichs gegen die Kriegspropheten in diesem Land einzuleiten. Derartig Visionen durften nicht einmal erwähnt werden. Jede rationale Politik wurde von EU und NATO verworfen. Stattdessen einigten sich der griechische Staat und die Europäische Zentralbank darauf, die finanziellen Griechenlandhilfen, von denen Deutschland den Anteil von etwa 70% aufbrachte, zu einem „Schuldenschnitt“ zu nutzen. Die Schuldenagentur in Athen legte Rückkaufwerte für die ausstehenden Staatsanleihen für „private Investoren“ fest. Sie erreichten einen höheren „Preis“, als von den griechischen und nordamerikanischen Investoren erwartet worden war. Der „Internationale Währungsfonds“ (IWF) sollte ruhig gestellt werden. Zugleich wurde es wichtig, die Verluste der Anleihen zu begrenzen und die Inhaber zu veranlassen, die Papiere zu einem nicht erwarteten Wert zurückzugeben. Der „Umtausch“ bzw. der „Rückkauf“ der Staatsanleihen durch die staatliche Agentur wurde mit Hilfe des europäischen und deutschen Hilfsgeldes attraktiv gestaltet, um die Gläubiger zu veranlassen, die fälligen Staatsschulden abzugeben. Der griechische Staat sollte dadurch einen Anfang gestalten, die riesigen Schulden zu tilgen.

Der internationale Anleihenmarkt reagierte mit einem Kurssprung der griechischen Staatspapiere. Sie stiegen von 4.31 Punkten auf 40.06 Zählern. Sogar der Euro konnte im Kurs gegenüber dem Dollar zulegen und stabilisierte seinen Kurswert, weil die Griechen zu einem nicht erwarteten Teilpreis die „Privatschulden“ bezahlten. Die Regierung in Athen verfolgt den Plan, mit Mitteln des Euro – Rettungsfonds (ESFS) die von Privatinvestoren oder Fondsgesellschaften gehaltenen Anleihen im Umfang von 10 Milliarden Euro zurückzukaufen. Es handelt sich um Papiere, die Griechenland im Frühjahr 2012 im Verfahren einer Umschuldung aufgelegt hatte. Der Rückkauf soll die Schulden, da der Preis zum Ursprungswert halbiert wurde, um rund 20 Milliarden Euro senken. Etwa Eindrittel der von Privatbanken gehaltenen Schulden wären durch diesen Rückkauf beglichen. Den Grossteil der griechischen Schulden, ein paar 100 Milliarden Euro, halten die Europäische Zentralbank, der Internationale Währungsfonds (IWF) und einzelne europäische Staaten. Die genaue Höhe dieser Werte fand bisher keine „öffentliche Zahl“. Gehen die Privatbanken auf dieses angebotene Geschäft des Rückkaufes ein, gibt es einen Wegweiser für die Freigabe der seit Juni „eingefrorenen“ Hilfsgelder. Die Entschuldung Griechenlands könnte langfristig über einen geregelten Rückkauf, über Staatsverträge und über den notwendigen Umbau des Sozial- und Steuerstaates angegangen werden.

Der vorsichtige Anleihenrückkauf verfolgt das Ziel, bis 2020 die Verschuldung auf 124% des Bruttoinlandsprodukts zu senken. Ohne derartige Massnahmen würden die Schulden Griechenlands „explodieren“ und den Staat in den Bankrott treiben. Ein derartiger Staatspleite würde das Land unregierbar machen, denn Teile der Betriebe der Dienstleistung, der Verwaltung, der Kommunen, der Staatswirtschaft würden schliessen müssen und zugleich die anderen „Südstaaten“ der EU in den Strudel der Staatspleiten reissen. Massenstreiks und soziale Unruhen waren zu erwarten. 2014 hätten die Schulden fast 200% des skizzierten Inlandsprodukts erreicht. Der Schuldenrückkauf musste deshalb sicherstellen, dass die Privatinvestoren auf das Geschäft eingehen und sich verpflichten, die angebotene Teilsumme zu akzeptieren. Die Staats- und staatlichen EU – Bankschulden wurden über Staatsverträge geregelt, an die sich die privaten „Spekulanten“ nicht halten mussten. Sie konnten internationale Gerichtshöfe anrufen, ihr Geld einklagen und den Schuldnerstaat in die Pleite jagen. Das passierte 2001 in Argentinien. 2012 wurde der Staatsbankrott des südamerikanischen Staates nicht abgewendet, denn die einzelnen Privatfonds bestanden auf der Zahlung des „gesamten Preises“ der Schulden. Die Konstruktion des Schuldenrückkauf war auch für Griechenland schwierig und der Staat musste eine „wacklige Normalität“ organisieren. Das komplizierte „Kartenhaus“ konnte schnell zusammenstürzen.

Die Entschuldung Griechenlands kannte drei Phasen. Zuerst mussten die Privatkunden, privaten Banken und Spekulanten in die Massnahmen eingebunden werden. Danach regelten Staatsverträge und Abmachungen den Rückkauf der Schulden von den Staatsbanken und Einzelstaaten. Unter Umständen wurde die Summe der Schulden Griechenland erlassen, falls nicht die anderen Schuldnerstaaten wie Spanien, Portugal, Italien, Irland u. a. die gleichen Bedingungen „einklagen“ würden. Der Schuldenrückkauf lief deshalb in der Form einer „Auktion“, um die Stimmungen und Interessen auf dem „Schuldenmarkt“ zu testen. Die Investoren und Gläubiger mussten ihre Preisvorstellungen offenlegen. Danach wurde von der Staatsagentur das Kaufangebot unterbreitet. Griechenland bot seinen Gläubigern je nach Laufzeit der Anleihe zwischen 30,2% und 38,1% des Nennwerts der jeweiligen Staatsanleihe. Den Zuschlag erhalten die Höchstgebote, die zwischen 32% und 40% liegen konnten. Auf dem freien Markt war lediglich mit einer Offerte zwischen 20% und 30% zu rechnen. Für einen begrenzten Zeitraum konnten die Spekulanten mit einem Zuschlag von etwa 10% rechnen. Sie hatten oft die Papiere auf dem niedrigen Stand von ca. 8% des Kurswerts gekauft und verdienten so nebenbei ein paar hundert Millionen Euro, denn Deutschland hatte nun zugesagt, weiterhin für die Schulden Griechenlands aufzukommen. Stimmten sie zu und schalteten nicht die internationalen Gerichtshöfe ein, konnte die zweite und dritte Phase eingeleitet werden. Nicht nur der deutsche Finanzminister zeigte sich nervös. Alles hing an einem „seidenen Faden“.

In Argentinien war 2001 eine derartige Planung gescheitert, die nordamerikanischen Spekulanten und die unterschiedlichen Staatsbanken unter einen „Hut“ zu bringen. Der Staatsbankrott zerstörten den argentinischen Mittelstand, der in Bezug auf Bildung, Dienstleistung, Sicherheit, Gesundheit, Fürsorge, Erziehung usw. vom Staat anhängig war und auf die Strasse gesetzt wurde. Dieser Mittelstand hatte die Elektro-, Mode-, Computer-, Nahrungsmittel-, Bau- und Autoindustrie „gefüttert“ und diese Branchen durch die Arbeitslosigkeit und Pleiten in den Ruin getrieben. Die Immoblienpreise zerfielen. Die Hedgefonds hatten sich am Spiel der „Entschuldung“ nicht beteiligt. Bis heute wird das ausländische Kapital angeklagt, Argentinien in den Abgrund zu treiben. Der Populismus von Cristina Kirchner bekam Auftrieb und aktualisierte den antiimperialistischen Kampf. Vor allem der Hedgefonds Eliot Capital und Aurelius Capital und der Internationale Währungsfonds (IWF) verklagten den argentinischen Staat auf die Zahlung von 1,5 Milliarden Dollar. Sie erhielten 2012 vor dem amerikanischen Gerichtshof Recht. Bereits Ende 2005 beglich Argentinien die Schulden beim IWF, bevor die anderen Gläubiger abgefunden wurden. Der IWF hatte 2001 einen Kredit zurückgehalten und den Staatsbankrott ausgelöst. Argentinien pocht heute auf Souveränität und ist bemüht, den Einfluss des internationalen Finanzkapitals zurückzudrängen, um so etwas wie „Souveränität“ zu erlangen. Die genannten Hedgefonds beteiligten sich nicht am „Schuldenschnitt“. Sie klagten vor dem US – Gericht auf Gleichbehandlung. Die Klage wurde in der ersten Instanz anerkannt. Muss Argentinien zahlen, wäre ein zweiter Staatsbankrott angesagt. Dieses Beispiel beweist, dass der Prozess und die Phasen der Entschuldung eine weitere Komplikation enthalten, ziehen die Spekulanten nicht mit. Sie verfolgen andere Ziele als die Staaten und sind primär an hohen Gewinnen und an der Sicherung der Rohstoffe, Ländereien und Immobilien interessiert. Sie setzen wie in Südeuropa auf Krieg, um die „Landmächte“ Iran, Russland und China zu entmachten. Die „Logik“ ihrer Spekulation ist schwer zu durchschauen. In Nordamerika und in Europa begründeten sie eine Doppelmacht zum Präsidenten oder zu den Staaten der EU, da eine Bankkontrolle fehlte bzw. zu Beginn der neunziger Jahre abgeschafft wurde. Die neuen Rohstoffe, Industrien und Immobilien in Osteuropa, Russland und Afrika sollten gesichert werden.

Die griechische Staatsanwaltschaft demonstrierte der europäischen Öffentlichkeit nach der letzten Zahlung der Hilfsgelder, was die griechischen Spekulanten mit dem leicht verdienten Geld aus der EU anfingen. Die Staatsanwaltschaft untersuchte Vorwürfe gegen knapp 2000 Griechen, die Bankkonten bei der Genfer Filiale der britischen Grossbank HSBC eingerichtet hatten. Ihnen wird Steuerhinterziehung, Geldwäsche und Finanzbetrug vorgeworfen. Illustre Namen aus Politik, Bankgeschäft und Mafia sind auf der Liste der Betrüger zu finden. Sie belegen Verbindungen, die vorher nicht einmal vermutet wurden. Mit dem Namen von Magret Papandreou tauchten Hinweise auf die Spitzen der politischen Elite auf. Sie lenkten auf raffinierte Weise Zahlungen aus der EU auf ihre Konten, überwiesen die Summen auf Schweizer, britische oder nordamerikanische Banken und kauften mit diesem Geld etwa in Berlin, München oder Frankfurt/ Main Immobilien, Mietshäuser, Grundstücke und landwirtschaftliche Nutzflächen. Die einzelnen Wohnungen wurden mit „Eigenbedarf“ belegt, verkauft und die Mieter vertrieben. Das Geld kam also nach Deutschland zurück und wurde in „sichere Anlagen“ investiert, weil Zentraleuropa für die Spekulanten eine gute Adresse war. Zugleich wurden die deutschen Steuerzahler, die die Zahlungen nach Griechenland aufbrachten und soweit die Wohnhäuser von den neuen griechischen Hausbesitzern „besetzt“ wurden, aus ihren Wohnungen gejagt.

Die griechische Staatsanwaltschaft deckte diese Machenschaften auf, um den Gremien der EU und Deutschlands die europäische Normalität des Rechtsstaates in Griechenland zu signalisieren, falls weiterhin die Unterstützungsgelder flossen. Sie brachten „Bauernopfer“, ohne den Kreislauf oder den Geldtransfer kaschieren zu wollen. Das europäische Geld wurde teilweise in Griechenland abgezweigt und landete auf den Konten in der Schweiz. Von dort wurde das Geld zum Immobilien- und Landkauf in Europa eingesetzt oder wurde genutzt, Ländereien oder Wälder in West- oder Ostafrika zu erwerben. Das „Holz“ wurde geschlagen und die Wälder gerodet. Anschliessend wurden riesige Soya-, Mais- oder Zuckerrohrfarmen errichtet, um aus diesen genmanipulierten Naturrohstoffen Biogas oder Bioöl herzustellen, das in Europa teuer zu Weltmarktpreisen verkauft wurde. Die afrikanischen Bauern wurden vertrieben und schlugen sich nicht selten als Flüchtlinge nach Europa durch. Allein an diesem Beispiel lässt sich die „negative Funktion“ der Finanzspekulation und des Finanzkapitals aufzeigen. Die Zerstörung aller „Produktivkräfte“ enthielt keinerlei Schaffenskraft oder eine Zielsetzung, die Weltgesellschaften zu stabilisieren. Falls die Regierungen der Zerstörungswut und der Raffgier dieses Kapitals keinen Einhalt boten, würde es über den Weltmarkt Not und Elend tragen. Die enge Kooperation der Spekulanten mit den Ganoven der Mafia und der politischen Eliten, die die griechische Staatsanwaltschaft aufgedeckt hatte, entwarf ein erstes „Gesicht“ dieses Kapitals, das keinerlei Moral oder Verantwortungsethik kannte. Erstaunt waren die Berichterstatter der Zeitungen, dass die Parteien des Bundestages, etwa die Grüne Partei und die CDU zu fast 100% der Griechenlandhilfe zustimmten. War die Erwartung einer zukünftigen „Koalition“ so gross, dass diese Parteien die aktuelle „Raumrevolution“ des Finanzkapitals nicht zur Kenntnis nahmen und sich diesen Manipulationen auslieferten? Würde ein Verteidigungsminister Trittin, deutsche Soldaten in die Türkei und in den Iran schicken? Gab es keinen „Karl Liebknecht“ bei den grünen Aufsteigern? Wurde die ganze Biographie dieser Poitiker für einen Staatsjob riskiert?

Fragen des Weltmarktes

Wieso konnte Afrika in Gestalt der Misswirtschaft, der niedrigen Arbeitsproduktivität, der Arbeitslosigkeit, der Überbevölkerung, der Verschuldung nach Südeuropa hineinragen? Warum wurde Russland „asiatisiert“? Wie konnte es passieren, das Afrika, Asien und Lateinamerika sich in den nordamerikanischen Kontinent eingruben? Die Kriterien sollen entschlüsselt werden in der je spezifischen Form des Kapitalismus der einzelnen Gesellschaften und Regionen. Die Übersetzung der technologischen Revolutionen in die Produktivität der Industrie und in den rationalen Aufbau von Staat, Recht und Verwaltung bestimmen ein weiteres Thema. Berücksichtigt werden soll das Ausmass der Konzentration und Zentralisation der Produktion, der Banken und des Handels. Die Machtpolitik der Kapitalfraktionen, vor allem des Finanz- und Medienkapitals und der politischen Klasse, bildet einen anderen Gesichtspunkt. Die Kriegs- und Rüstungswirtschaft, gekoppelt mit den unterschiedlichen Ansätzen von Diktatur, mit der Neudefinition der Klassen und Völker und mit den politischen Bündnissen der einzelnen Eliten, umreissen einen weiteren Masstab der kapitalistischen Durchdringung der einzelnen Kulturen und Erdteile. Wichtig bleibt in diesem Zusammenhang von Machtpolitik und Imperialismus die Disposition der Ideologie und die Umsetzung in Propaganda, Reklame und politische Religion. Der Okkultismus der herrschenden Cliquen gewinnt an Bedeutung, denn sie reagieren auf eine wachsende Rationalität von Organisation und Planung, auf die Unregierbarkeit von „Massen“, die durch Automation und Denkmaschinen aus Arbeit und „Brot“ gedrängt werden. Die herrschenden Machteliten verbergen über rassische, religiöse oder völkische Mythologien die Potentialitäten der sozialen Frage und der „Freiheit“. Sie begründen über Verschwörungen und parapsychologische Phantasmen den Führungsanspruch. Im Angesicht einer technisch begründeten Produktionsordnung radikalisieren die Spekulanten und Ideologen den Irrationalismus und zerren die Neuzeit zurück in das dunkle Mittelalter. Wie lassen sich nun derartige Differenzen und die Formen von Machtpolitik skizzieren?

1. Differente Akkumulationsbedingungen des Kapitals im Weltmaßstab: Entscheidend für die potentielle Einheit und für den hierarchischen Aufbau des Weltmarktes sind und waren die unterschiedlichen Akkumulationsbedingungen des Kapitals. Marx und Engels skizzierten bereits die unterschiedlichen Formen einer ursprünglichen Akkumulation des Kapitals in England, Frankreich, Preussen, Russland und Nordamerika. England wies die klassische Form des Kolonialismus, der Vertreibung, des Handels, des Manufakturkapitals, der „industriellen Revolution“ und der Proletarisierung der eigentumslosen Bauern und Städter auf. Frankreich und USA kannten neben dem Staat die Unterstützung des Finanzkapitals, das jeweils die Kredite für die industrielle Akkumulation zur Verfügung stellte. Die Rüstungswirtschaft und der Aufbau einer modernen Armee und Flotte wurden Motor einer technologischen „Revolution“, die sich an den neusten Waffensystemen orientierte. Die staatlichen Investitionen wurden durch Kredite unterstützt, die das Finanzkapital zur Verfügung stellte. Es favorisierte die Herausbildung der Monopole, der Trust und Syndikate, um die organisatorische und wertmässige Konzentration der Produktion durch eine Zentralisation der „Produktivkräfte“ zu steigern, die eine bessere Arbeitsteilung und eine enge Kooperation der Betriebe und Regionen ermöglichten. Preussen bereits übersetzte über Staat und Armee die technologischen und industriellen Errungenschaften des „Westens“ in Reformen und in eine staatskapitalistische Kriegswirtschaft, die auf der Privatwirtschaft fusste, zugleich jedoch die Erfindungen und Entdeckungen, die Forschung materiell und produktiv in der Rüstung umsetzte. Die Mischformen staatlicher und privater Initiativen wurden bedeutsam. Diese wiederum beeinflusste die zivile Produktion. Über eine weitgefächerte Bildung der Berufs- und Ingenieursschulen und über das System der Forschungsstätten, der Naturwissenschaften und technischen Universitäten wurde ein Mittelstand geschaffen, der als Unternehmer, Forschungsintelligenz, Management, Verwaltungsspezialist, Offizier die Effiziens und die Breite der industriellen Produktion in Gross- und Kleinbetrieben förderte. Über diese technologische und bildungspolitische Kooperation manifestierten sich politische Bündnisse zwischen den Facharbeitern und Ingenieuren, Gewerkschaften und Unternehmern, Parteien und Armee. Die Kriegswirtschaft als staatskapitalistisches Unternehmen bewährte sich nach 1945 als eine enge Zusammenarbeit der gesellschaftlichen Kräfte. So „gewann“ das westliche Deutschland in den fünfziger Jahren durch ein „Wirtschaftswunder“ nachträglich den II. Weltkrieg.

2. Staatskapitalistische Erweiterung der kapitalistischen Industrialisierung: In Russland und USA wurde dieses „preussische Modell“ (Stolypin nach 1905, New Deal nach 1934) übernommen, wirkte jedoch unterschiedlich. Russland wollte den preussischen Reform- und Militärstaat übertragen, scheiterte jedoch an der Schwäche der Staatseliten und des russischen Industriekapitals. Die Arbeiterklasse als legale Gewerkschaft konnte sich nicht formieren. Die bolschewistische Diktatur errichtete nach 1917 einen Kriegskommunismus, der primär über Terror und Zwang die industrielle Akkumulation umsetzte. Zugleich wurden die Klassen und Völker über die Staatsdespotie und die Zwangsarbeit umdefiniert in „werktätige Massen“. Die Rüstung stand im Mittelpunkt, erlangte jedoch nie die Produktivität des westlichen Kapitalismus und konnte nur bedingt auf die zivile Produktion übertragen werden. Trotz einer Bildungsreform fehlten in einer Mangelwirtschaft die produktiven Facharbeiter und Ingenieure. In einem Zwangssystem verpasste die Propaganda und die politische Ideologie die Erziehung selbstbewusster und produktiver Arbeitskräfte. Bis 1989 konnte die Diktatur über Polizei- und Militärgewalt das russische Imperium bewahren, das danach unter den Schlägen des westlichen Kapitalismus sehr schnell zusammenbrach. Die russische Macht, eingeklemmt in den Methoden von Staatskapitalismus, Planwirtschaft, despotischer Präsidialmacht und Privatkapital, hatte Probleme die innere Konsistenz gegen die vielen Völker und nationalen Märkte zu behaupten. Der Präsident Putin nahm deshalb die Ziele der bolschewistischen Expansion erneut auf, um sich gegen das US – Finanzkapital behaupten zu können, das an den Rohstoffen und an den Zerfall Russlands in Einzelrepubliken interessiert ist.

3. Finanzkapitalistische Formen der Konzentration und Zentralisation des Kapitals: In USA sorgte das Finanzkapital für die wirtschaftpolitische Besonderung und „Funktion“ der Monopole und Syndikate, die durch Armee und Flotte unterstützt und durch die Präsidialmacht finanziert und kontrolliert wurden. Schon deshalb erlangte hier das Finanzkapital den Zuschnitt einer Doppelmacht, die Einfluss nahm auf die „Politik“ und die Medien und ausserhalb der Verfassung innen- und aussenpolitische Ziele verfolgte. Es sicherte sich den Zugriff auf die Weltrohstoffen und forderte die Unterstützung von Armee und Flotte. Es konkurierte mit dem europäischen und asiatischen Imperialismus und übernahm sehr bald die Erbschaft des spanischen, portugiesischen, französischen und englischen Imperialismus. Der dreissigjährige Krieg mit Deutschland und Japan nach 1914 liess sich nicht vermeiden. Der Sieg über Japan und Deutschland machten Russland und China zu den Hauptgegnern. Nicht der amerikanische Präsident propagierte den Mythos von „Feindschaft“ und „Okkupation“, sondern das Finanzkapital folgte hier der Logik von Profit, Macht, Markt und Rohstoffsicherung, kaschierte jedoch diese Ansprüche unter den Handels-, Freiheits- und Menschenrechten. Es sorgte dafür, dass über internationale Verträge und Militärstützpunkte die mediale „Inszenierung“ und Gestaltung der Demokratie und die Herrschaft der Machteliten auf die Einflusszonen übertragen wurden. Neben den russischen und chinesischen „Reichen“ und „Kontinenten“ wurde nach 1918 und vor allem nach 1945 und 1989 ein nordamerikanisches „Imperium“ gefestigt und ausgedehnt.

4. Der chinesische Weg der Industrialisierung: China kombinierte die russische Erfahrung von Staatskapitalismus und Planung mit einer Öffnung zum Weltmarkt und zum westlichen Finanzkapital. Es sicherte vielfach das chinesische Reich über staatliche Grossbetriebe, Zwangsarbeit, Kleinwirtschaft, „Kommunen“, das Primat der “Partei“, Militarisierung der Gesellschaft und Polizeiwillkür. Die Gefahr der Verselbständigung einer „Despotie“ sollte durch die materiellen Anreize eines mittelständischen Privatkapitalismus und der „Konkurrenz“ der staatlichen Grossbetriebe auf dem Weltmarkt aufgebrochen werden. Jedoch nicht die kapitalistischen Investoren oder das private Kapital sollte die Oberhand gewinnen und dem westlichen Finanzkapital Einfluss und Herrschaft gewähren. Der chinesische Staatskapitalismus improvisierte als Staatshandel und Staatsbank die westlichen Methoden der Spekulation und der Kreditvergabe und koppelte diese „Kapitalisierung“ mit einer ökonomischen Politik des privaten Handels, des Mittelstands und der Bauernwirtschaft. Zugleich produzierten die Staatsbetriebe vorerst Ramschprodukte für den Weltmarkt, stellten sich jedoch auf eine Qualitätsarbeit im Auto- und Maschinenbau ein. Ob dieser Kriegskommunismus als Friedenswirtschaft Erfolg haben wird, wird sich zeigen. Eine Rüstungswirtschaft, moderne Armee und Flotte belegen die Ziele eines chinesischen Imperialismus, der seinen Einfluss in Asien und Afrika ausbaut. Hatte Russland Mühe, sich als europäische und asiatische Macht zu konsolidieren, stemmte sich die Volksrepublik China gegen die us-amerikanischen Ansprüche von Weltmacht und Einflusszonen.

5. Mischformen der Industrialisierung: Der asiatische Kontinent weist neben dem japanischen und chinesischen Weg zum Kapitalismus Wirtschaftsexperimente auf, die sich an Europa, die USA, Russland oder das britische Empire orientieren. Die wachsende „Überbevölkerung“ kann durch eine mässig wachsende Wirtschaft nicht absorbiert werden. Sie wandert ab, gefördert durch den Weltmarkt oder durch ein EU – Recht oder illegal, nach Europa, Russland oder Nordamerika. Dadurch entstehen in diesen Gesellschaft „kulturelle Zonen“, die die ursprüngliche, nationale Kultur zersetzen oder zu einem neuen, anderen Zusammenhalt kombinieren.

6. Die Teilmärkte unter dem Druck des Weltmarktes: Der Weltmarkt teilt sich auf in die unterschiedliche Teilmärkte, die zwar der industriellen Produktivität „Rechnung“ tragen und sich den Durchschnittpreisen, Gewinnen und Profiten annähern, trotzdem die Politik und den Staat als Regulator benötigen. Dieser Staatseingriff wird durch das nordamerikanische Finanzkapital in Lateinamerika, Europa, Afrika, Australien, Asien, Russland und China aufgebrochen. Die Sicherung der Weltrohstoffe wird als Ursache der Intervention genannt. Es geht jedoch darum, jede Souveränität und Unabhängigkeit auszulöschen, um über einen Weltmarkt die eigene Ordnung zu sichern, die eine Konkurrenz der kulturellen Werte, der politischen Mächte oder gar des Fremdkapitals nicht dulden kann. Die Sicherung der Macht des Finanzkapitals benötigt den Staat und die Legitimation über eine „parlamentarische Demokratie“, die allerdings den Interessen der Lobbygruppen des Kapitals folgen muss. Diese „Legitimation“ durch die „Massen“ benötigt die mediale Inszenierung von Politik und Wohlbefinden und sie ist auf die Einfluss- und Machtlosigkeit der „Bürger“ und „Wähler“ angewiesen. Schon deshalb werden die Partei- und Staatseliten kontrolliert, „bezahlt“ und „verwaltet“. Derartige Herrschaftsmethoden und Feindbilder gegen Russland, China, den Iran, den Islamismus erfordern die politische, wirtschaftliche und kulturelle Einheit des Imperiums.

7. Die Theorie des staasmonopolistischen Kapitalismus und die Fragen der „Raumrevolution“: Nikolai Bucharin und Eugen Varga begründeten eine Theorie des „Staasmonopolistischen Kapitalismus“ (Stamokap), die von einer doppelten Negation der finanzkapitalistischen Intervention auf Wirtschaft und Staat ausging. Die Existenz der „Sowjetunion“ und der kommunistischen Arbeiterbewegung zwang nach diesem theoretischen Kalkül das Finanzkapital, einen Sozialstaat anzuerkennen und zu fördern und zugleich gegen die kommunistische Herausforderung faschistische oder konterrevolutionäre Parteien oder Formationen zu formieren. Mit Hilfe dieser „konterrevolutionären Kräfte“ wurden Kriege vorbereitet, konnte Georgij Dimitroff auf dem VII. Weltkongress der Kommunistischen Internationale berichten. Ein ausserökonomischer Faktor verlangte neben den Verfassungsrechten die Anerkennung sozialer Rechte im Staatsaufbau. Zugleich fand der „Faschismus“ Unterstützung, um die kommunistischen Ansprüche einzugrenzen und zu überwinden. Wir folgen dagegen der Einschätzung von Karl Marx, Rudolf Hilferding, W. I. Lenin, Rosa Luxemburg, Max Horkheimer und Herbert Marcuse. Die Arbeiten der konservativen Denker um Max Weber, Carl Schmitt und Ernst Forsthoff über die Herrschaftsformen und über den Status von Recht und Verfassung geben weitere Einblicke.

8. Zur Theorie der Doppelmacht: Das Finanzkapital formierte neben dem nationalen Staat eine internationale Doppelmacht. Die Staatsinterventionen bzw. die Methoden des Staatskapitalismus wurden genutzt, eigene Interessen umzusetzen. Die „Inszenierung“ der Demokratie als Parteienherrschaft und als Medienmacht sollte sicherstellen, die politischen Eliten in Abhängigkeit zu bringen und die sozialen Klassen und Interessengruppen zur Anerkennung bestehender Herrschaft zu zwingen. Die Umdefinition der Klassen in Publikum, Konsument, Zuschauer usw. sicherte neben der Subsumtion der politischen Eliten unter die kapitalistischen Interessen die Macht des Finanzkapitals, ohne Widerstand oder Widerworte zu riskieren. Die „Paralyse“ und die „Chaotisierung“ der Gesellschaft, ihre Pauperisierung und Verwahrlosung garantierten die finanzkapitalistische Macht als demokratisch inszenierte Diktatur. Diese Macht wirkte expansiv und empfand jeden Widerspruch als politische Herausforderung, so dass neben dem Sicherheitsstaat der Sozialstaat die Ausmasse eines totalen Staates gewann, ohne allerdings eine offensive „Militarisierung“ und „polizeistaatliche Kontrolle“ der Gesellschaft zu eröffnen. Die Sicherung der Weltrohstoffe und die massive Aufrüstung trugen die Potenzen neuer Kriege. Neue Regionen und Kontinente sollten vom Imperium besetzt werden.

9. Finanzkapitalistische Machtprinzipien und die Zerstörung der kontinentalen Ordnung: das Beispiel Russland. Der Zusammenbruch des russischen Kriegskommunismus Ende der achtziger Jahre hatte viele Ursachen. Die Planwirtschaft verlor die Übersicht über die industriellen und materiellen Ressourcen. Die Hierarchie der politischen und wirtschaftlichen Entscheidungsträger potenzierte einen Bürokratismus, der auf die produktiven und technologischen Veränderungen der industriellen Produktion nicht mehr reagieren konnte. Die Mangelwirtschaft schuf Unzufriedenheit im Volk. Die Arbeitsethik wurde zerstört. Schlamperei, Diebstahl, Gleichgültigkeit und Sabotage gehörten zum Arbeitstag der Ingenieue und Arbeitskräfte. Die ideologische Propaganda verlor jede Resonanz. Die Mangel- und Planwirtschaft gab den russischen Werktätigen „überschüssiges Geld“, das sie nicht ausgeben konnten, weil es nichts zu kaufen gab. Die Korruption zerfrass eine geplante „Reproduktion“ der Wirtschaft. Ein „geheimer Kapitalismus“ breitete sich über den Schwarzmarkt und über die organisierte Kriminalität in der Wirtschaft und in den „Staatsorganen“ aus. Den Rüstungswettstreit zwischen USA und UdSSR musste die russische Diktatur verloren geben. Die Rüstungswirtschaft befruchtete nicht die Konsumindustrie. Sie kostete Riesensummen Rubel. Forschung und Spionage waren schlecht mit der Wirtschaft koordiniert. Armee und Geheimpolizei konnten die Gesellschaft nicht länger „militarisieren“ oder kontrollieren. Im wachsenden Chaos konnte sich das finanzkapitalistische Prinzip von Macht und Geschäft ausbreiten, wie Michail Chodorkowski in „Mein Weg, ein politisches Bekenntsnis“ beschreibt. Erste Reformen legalisierten zum Ende der achtziger Jahre den „grauen“ und den „schwarzen“ Markt. Ein eigenständiges „Wirtschaften“ sollte die Kooperation zwischen den Staatsunternehmen und den Universitäten erleichtern. Die Kosten sollten für die staatlichen Grossbetriebe gesenkt werden. „Private Kooperative“ sollten die Möglichkeiten schaffen, mehr Konsumgüter herzustellen. Chodorkowski organisierte in Moskau an der Universität und an der Akademie der Wissenschaften junge Forschungsspezialisten, die neue technische Produkte entwarfen und für den Konsummarkt aufbereiteten. Vor allem die Computertechnik, die Produktion künstlicher Diamanten oder Kunststoffe, Farben wurden für russische Verhältnisse übersetzt, verändert und für die Massenproduktion vorbereitet. „Leistungsverträge“ zwischen den einzelnen Abteilungen der Universität und den Staatsbetrieben wurde geschlossen, um an „Material“ oder Rohstoffe heranzukomen. Ein staatliches Komitee für Preise behinderte weiterhin die Flexibilität der Kooperativen und sorgte für langwierige und bürokratische Verfahren. Das „übeschüssige Geld“ der Betriebe und der Konsumenten verlangte nach einem „freien Handel“, der schliesslich von der staatlichen Preisaufsicht gewährt wurde. Die Planwirtschaft zerbrach. Jetzt liefen sogar die Geheimpolizisten zu den neuen Unternehmern über und lieferten Informationen. Chodorkowski erlangte dadurch von der Staatsbank die Erlaubnis, eine „Geschäftsbank“ zu gründen und mit Devisen und ausländischen Waren, etwa mit amerikanischen Computern, „russifiziert“ im Sprachprogramm und in der „Logistik“, zu handeln. Als erfolgreicher Unternehmer unterstützte er Jelzin bei der Präsidentenwahl Mitte der neunziger Jahre. Es gelang ihm, Erdölquellen und Rohstoffelder zu erwerben und gründete im neuen Jahrtausend den Yukos – Konzern. Er kooperierte eng mit den nordamerikanischen Chevron – Konzern und wollte eine Pipeline nach China und nach Murmansk errichten. Von Chevron übernahm er unterschiedliche Technologien, die das nordamerikanische Patent trugen, die als „Privileg“ die Dieselproduktion aus Erdgas „revolutioniert“ hätten. Chodorkowski finanzierte die russischen Parteien Jabloko, Einheitliches Russland, sogar eine Kommunistische Partei. Zugleich wollte er Fernsehsender aufkaufen, Universitäten und Forschungsakademien einrichten und sich als Präsidentschaftskandidat gegen Putin aufstellen lassen. Er verkörperte ohne Zweifel die amerikanische „Freiheit“ in Russland, trotzden stand die „Struktur“ von Politik und Öffentlichkeit, Technik und Patentrecht, Finanzkapital und Rohstoffverarbeitung, Wissenschaft und Forschung nicht in der „russischen Tradition“. Der Schutz des Volkes, der Rohstoffe und der Wirtschaft liess sich mit dieser „Kapitalisierung“ nicht vereinbaren. Nicht aus dem „russischen Kontinent“ wurden neue Formen der Demokratie, des Rechts und des Marktes aus dem „Kriegskommunismus“ ertrotzt, sondern das Prinzip des westlichen Finanzkapitalismus wurde „aufgeproft“. Das mag der Grund sein, warum der Präsident Putin Michail Chodorkowski verhaften liess.

10. Die vier Säulen der nordamerikanischen Zivilisation: In Strategiepapieren des Center for a New American Security (CNAS) und des German Marshall Fund of the United States (GMFUS) werden die vier Säulen der nordamerikanischen Weltordnung herausgestellt. Sie umfassen Frieden, Wohlstand, Demokratie und Menschenrechte. Sie werden gesichert und ausgebaut über die Welthandelsordnung (WTO), Weltfinanzordnung (IWF), Seefahrtfreiheit (UNCLOS), die Nichtverbreitung von Atomwaffen und die Menschen- und Freiheitsrechte. In Russland und vor allem in China werden diese Säulen des nordamerikanischen Imperiums nicht anerkannt. Die chinesische Volksrepublik unterläuft durch Staatsunternehmen, durch die Staatsbank und durch die Kopie der finanzkapitalistischen Methoden in Handel und Kreditmarkt die Welthandelsordnung. China untergräbt durch eigene Kreditvergaben den internationalen Währungsfonds und wickelt den Welthandel nicht über den Dollar, sondern über den chinesischen Yuan ab und vergibt eigenständig Kredite an afrikanische und lateinamerikanische Staaten. Diese Grossmacht benutzt den Dollar zur „Gegenspekulation“, um die manipulierte Staatsverschuldung und Währungspolitik des nordamerikanischen Finanzkapitals in den Staatsbankrott der USA zu überführen. China verstösst gegen das internationale Seerecht, denn es beansprucht Inseln im südchinesischen Meer. Es will die Rohstoffe und Erdöllager für die chinesische Volkswirtschaft sichern. Der Bau der Atomwaffe wird durch China in Nordkorea und im Iran unterstützt. Es akzeptiert nicht die westlichen Handels-, Menschen- und Freiheitsrechte und unterstützt eine politische Ordnung, die sich grundsätzlich von der nordamerikanischen Demokratie unterscheidet. Dadurch gibt primär China sich als „Feind“ der USA und Westeuropas zu erkennen. Cuba, Venezuela, Iran, Russland wären machtunfähig, würde China nicht für die Souveränität dieser Staaten einstehen.

11. Die USA und die „Swingstaaten“: Um China zu isolieren, orientieren die USA sich auf die „Übergangs- und Swingstaaten“, die eine eigenständige Industrialisierung durchführen und zugleich Teilmärkte des Welthandels bilden. Es handelt sich um Brasilien, Indien Indonesien und die Türkei. Diese Staaten sollen überzeugt werden, die chinesische Wirtschaftsexpansion zu stoppen. Im Rahmen der WTO sollen Schutzzölle gegen chinesische Importe erhoben werden. Mit den einzelnen Unternehmerverbänden sollen Verhandlungen aufgenommen werden, die chinesische Konkurrenz einzudämmen und zu vermeiden, chinesische Kredite anzunehmen. Freihandelszonen mit den USA sollen gegründet werden, um die eigene Wirtschaft zu fördern und den Einfluss des IWF zu gewährleisten. Aus diesem Währungsfonds sollen die Nationalbanken und Staaten Kredite aufnehmen. Eine Kooperation mit Brasilien sollen die USA befähigen, in Afrika eine neue Entwicklungspolitik aufzunehmen, die sich nicht primär um die Rohstofflager kümmert, sondern die wirtschaftlichen Grundlagen der einzelnen Staaten fördert. Die chinesischen Erfolge in Afrika beunruhigen die USA, die Brasilien einsetzen müssen, um auf die afrikanische Kultur und Sozialstruktur eingehen zu können, ohne die korrupten Eliten zu unterstützen. Die Militärmacht der Türkei wird angesprochen, die arabischen Armeen in Saudiarabien zu trainieren und die Verbindungen zur NATO und zur Bundeswehr zu verstärken. Das türkische Militär soll zur politischen Stabilisierung der Region beitragen, falls ein interner Bürgerkrieg die staatliche Struktur Syriens und des Iraks zerstört. Die türkische Armee soll die Intervention der USA oder Israels „übernehmen“ und zugleich den Nahen Osten im Sinne der nordamerikanischen Ordnung befrieden. Der Türkei wird zugestanden, dass kein kurdischer Staat gegründet werden kann. Ausserdem soll die Türkei Teil der EU werden, um diesen Staatenbund und die NATO in den potentiellen Krieg gegen den Iran und gegen Russland einzubinden. Diese Swingstaaten sollen angeregt werden, Parteien und politische Eliten im nordamerikanischen Sinn aufzubauen. Ausserdem sollen Nichtregierungsorganisationen (NGO) den chinesischen Einfluss in Indonesien und in den arabischen Staaten zurückdrängen.

12. Die Weltüberbevölkerung und die sozialen Völkerwanderungen: Die Produktivität der kapitalistischen Industriezweige und das Wachsen der Weltbevölkerung „produzieren“ eine Überbevölkerung, die von den bestehenden Arbeitsmärkten der einzelnen Staaten nicht aufgenommen werden kann. Eine grosse Masse, junge und alte Arbeitskräfte, Flüchtlingen, Vertriebene, Verelendete, Arme, Emigranten werden durch Sozialhilfen und Hilfsgelder ernährt. Sie erlauben primär in Zentraleuropa, in Deutschland und in einzelnen Städten und Staaten der USA den Betroffenen ein „Überleben“, das lediglich den Bruchteil des Wohlstands des Mittelstands erreicht. Fast Eindrittel der europäischen Bevölkerung geriet in den Status der Hilfsbedürftigen. Sie „geniesst“ einen Lebensstandard, der zwar im Masstab des Landes „erbärmlich“ bleibt, trotzdem gegenüber Afrika, Asien und Lateinamerika eine „Verheissung“ vorstellt. Dort darben fast Zweidrittel der Völker ohne Land, ohne Auskommen und Arbeit in den Slumgrosstädten. Eine industrielle Entwicklung scheint unmöglich zu sein, weil die imperialistischen Mächte an Rohstoffen, Urwald und Land interessiert sind und die korrupten Eliten diese Interessen bedienen. Vor allem die Jugend kennt deshalb nur ein Ziel, nach Europa oder Nordamerika zu kommen, um hier zu überleben. Dieser Sozialstaat und dieses Flüchtlingslager in Europa müssen polizeiliche Methoden der Kontrolle einsetzen, um diese Massenbevölkerung der Paupers unter Aufsicht zu halten. Nicht allein der Ausnahmestaat, Rüstung und Militär bedrohen den Rechtsstaat, er wird zugleich durch den Sozialstaat untergraben, der die Hilfsgelder verteilen muss. Neben dem Ausbau des Sicherheits-, Militär- und Polizeistaates übernimmt der Sozialstaat Polizeiaufgaben, denn Einkommen, Bankkonten, Geschäfte, Krankheit, Geburt, Gesundheit der einzelnen Bürger werden durch diesen Staat registriert und verwaltet. Die kleine Schicht der Millionäre und Milliardäre aus dem Sektor der Finanzspekulation wird allerdings von diesen Massnahmen ausgenommen.

13. Jugendarbeitslosigkeit: Nach Berechnungen der Internationalen Arbeitsorganisation (ILO) hat die aktuelle Krise fatale Auswirkungen auf die Sockel- und Jugendarbeislosigkeit. Die produktive Industrie, Wirtschaft und Verwaltung können in Europa die Masse der Arbeitslosen nicht mehr aufnehmen und beschäftigen. Selbst wenn die Konjunktur irgendwann wieder anspringen würde, wäre diese Massenarbeitslosigkeit nicht überwindbar. In Spanien etwa lag die strukturelle Arbeitslosigkeit Ende 2011 bei 12,6% der arbeitsfähigen Bevölkerung. Diese Arbeitslosen würden zu keinem Zeitpunkt mehr einen Arbeitsvertrag erhalten. Griechenlands „bereinigte“ Erwerbslosenrate wies die Ziffer von 12,8% auf. Vor allem die Südländer der EU gewannen für Investoren keinerlei Attraktivität. Sie errichteten die neuen Autofabriken oder Zuliefererfirmen in China, Indien oder in USA. Die miserable Schul- und Berufsausbildung, die schlechte Arbeitsmoral und die Kosten schreckten die Finanziers ab. Dadurch stieg die „Trendarbeitslosigkeit“ in Südeuropa noch weiter. Vor allem junge Menschen sind von dieser Arbeitslosigkeit betroffen. Ihre Biographie wird kaum eine Beschäftigungskarriere aufweisen, falls sie nicht nach Nordeuropa auswandern. Bei den jungen Menschen unter 25 Jahren ist in Europa fast jeder vierte ohne Arbeitsplatz, Die Arbeitslosigkeit erreicht in dieser Gruppe oder „Generation“ der Erwerbslosen über 25%. Eine wachsende Verwahrlosung der Jugend ist zu erwarten. Soziale Unruhen und Radikalismus finden in dieser hoffnungslosen Jugend ein Echo. Zwar sollen staatliche Massnahmen eine „Bildungspolitik“ ergänzen, die die Jugend bisher an die Universitäten, Schulen und Fachhochschulen versetzt hatte, ohne ihr gesellschaftlich notwendige Berufe oder Fachwissen zu vermitteln. Derartige Bildungsmassnahmen sind kaum finanzierbar, werden jedoch von der EU erweitert und auf die Unterschichtsjugend ausgedehnt, ohne zu wissen, welche Ziele diese „Beschäftigungstherapie“ verfolgt. Sie in die Armeen zu stecken, die Gesellschaften zu militarisieren, würde die Gewaltbereitschaft und die Kriegsgefahr erweitern. Den Zynismus der Politiker kann sich niemand vorstellen, die Jugenderwerbslosigkeit und die Massenarbeitslosigkeit über Kriege regeln zu wollen.

14. Die Neugeburt des nordamerikanischen Kontinents: Eine neue Lage auf dem Weltmarkt entstand, als sich herausstellte, dass in den USA riesige Erdöl- und Erdgaslager gefunden wurden. Die Preise für Energie mussten nicht ausschliesslich über die Sicherung der Weltrohstoffe gewährleistet werden. Das US – Finanzkapital verfügte über Rohstoffreserven, die für eine Reindustrialisierung Nordamerikas eingesetzt werden konnten. Die industrielle Infrastruktur wurde bisher durch den europäischen Maschinenbau, die Auto-, Chemie- und Pharmaindustrie gefährdet. In USA war ausserdem die Bildungskapazität der Facharbeiter, der Ingenieure und des mittleren Managements unterentwickelt. Neben der Spitzenforschung und neben den Spezialisten und Forschern in der Rüstungsindustrie fehlte der Unterbau einer grundlegenden Fach- und Berufsausbildung. Durch die billigen Energiepreise für Kohle, Diesel, Bezin und Elektrizität verlangten die Hilfs- und Massenarbeiter keine hohen Löhne, denn die Sozial-, Renten- und Gesundheitsabgaben waren gering. So kann passieren, dass der deutsche Maschinenbau, die Autoindustrie und die anderen produktiven Industriezweige in Nordamerika neue Betriebe aufbauen und die Gesellschaft bildungs- und berufsmässig „kultivieren“. Der Schaden, den die Finanzoperationen und Spekulationen in Nordamerika angerichtet hatten, wird plötzlich durch die nordeuropäischen Kulturleistungen relativiert und zurückgenommen. Es ist jedoch anzunehmen, dass das US – Kapital aus den alten Fehlern nichts lernen wird. Erneut wird das Prinzip des „Catch is catch can“ alle Aufbauleistungen zerfetzen. Ein „europäischer“ Reform- und Bildungsstaat wird nicht existieren.

15. Über den Okkultismus als Herrschaftsprinzip: Die Marx’sche Religionskritik und die konservative Feindanalyse stimmen in einzelnen Punkten überein. Für Marx stand in der Kritik am Christentum fest, dass der Geldfetisch, das Finanzgebaren, die Spekulation, die Gesinnungsethik des Geldgeschäfts alle Religionen erfassten, die wie die jüdischen, katholischen, protestantischen und islamischen Religionen von einem einzigen „Menschengott“ sprachen, der im Leben der Menschen und zugleich in der Geschäfts- und Arbeitsethik „verkörpert“ wurde. Nicht nur dass die Menschen in diesen Religionen sich als Menschheits- und Sozialprinzip selbst anbeteten, sie übertrugen nach Marx die Geldakkumulation und die Mühen der notwendigen Arbeit auf die Religion als Schuld und Verheissung. Dadurch verloren die religiösen Menschen das Bewusstsein von Freiheit und Gerechtigkeit. Sie leiteten die Freiheits- und Menschenrechte aus den frühen und entstehenden Kapitalismus ab. Ein „Geld- und Warenfetisch“ wurde nach Marx auf den Liberalismus und auf die unterschiedlichen Utopien und „politischen Religionen“ übertragen. Durch diese Übermacht der religiösen Mysterien im menschlichen Denken wurden die die nachfolgenden Ideologien als „politische Religionen“ einem wachsenden Irrationalismus ausgesetzt. Je technisch rationaler die Gesellschaft durch den modernen Kapitalismus gestaltet wurde, desto irrationaler wurde der Glauben bzw. die ideologische Weltsicht. Völkerhass, Rassismus, Astrologie, Weltuntergang, Wunderglauben und Mystik steigerten den irrationalen „Verstand“ in einer durchrationalisierten und technologisch vollkommenen „Gesellschaftsmaschine“. Dieser religiöse Okkultismus war deshalb nach Marx Mittel, die Aufklärungsphilosophie zu verfälschen und die soziale Angst und Entwurzelung zu politisieren. Die Herrschaft der wenigen Geldmagnaten und Mächtigen konnte nur gelingen, wenn die Klassen, Völker und Nationen jeden Gedanken an die eigene Stärke und Tradition verloren und sich in einem Kampf der Religionen und Kulturen verschleissen liessen. Marx sprach diese Religionskritik wiederholt als Form der „Entfremdung“ und der „reellen Subsumtion“ der Arbeitskräfte unter die Kapitalbedingungen von Markt, Geld, Lohn, Profit, Preis und Produktion an. Dem atheistischen Materialisten interessierten nicht die moralischen, ethischen und kulturellen Aufgaben der „Menschengottreligionen“, um so ewas zu garantieren wie „Gottvertrauen“, Moral und Verantwortungsethik. Die Religion gewann bei den Konservativen einen anderen Stellenwert. Die konservativen Kritiker des Liberalismus und der modernen Ideologien setzten eine Feindanalyse an den Anfang der Staats- und Demokratiekritik. Der Feind und Gegner der eigenen Kultur, der die Lebens- und Arbeitsbedingungen bedrohte oder sogar zerstörte, sollte analytisch bestimmt werden, um einen fatalen „Funktionalismus“ bzw. eine Rechtfertigung der kapitalistischen Produktion oder des Bankgeschäfts zu vermeiden. Katholizismus oder Protestantismus bezeichneten den Ausgangspunkt der Feindsicht. Der wachsende Irrationalismus, die Dekadenz, die Zerstörungswut, die „Fäulnis“ des Feindes sollte benannt werden, um sich der eigenen Kraft und Gesellschaftlichkeit zu vergewissern. Die christliche Religion bildete die Voraussetzung der Feindanalyse. Sie gab Grundwerte und Tradition. Diese Vorgehendweise lässt sich in der Philosophie von Martin Heidegger, in der Soziologie von Hans Freyer, in den Arbeiten von Ernst Jünger und in der Staatstheorie von Carl Schmitt aufspüren.

Skizzen einer „Raumrevolution“ in Europa

Die USA übertrugen nach dem II. Weltkrieg ihre Herrschaftsmethoden und die Prinzipien der Macht auf Westeuropa und Japan. Nach 1989 wurden Versuche gestartet, Osteuropa, Russland, die Türkei und sogar den Nahen Osten nach diesen Ordnungsfaktoren zu gestalten. Die USA betätigten sich in diesen Gesellschaften nicht offen als Kolonialmacht, Diktatur und Unterdrücker, obwohl der militärische Sieg und die Besetzung der genannten Länder erst die Garantie bot, die eigenen Interessen umzusetzen. Formal wurden die Freiheits- und Demokratierechte eingeführt und sogar Wirtschaftskonjunkturen angestossen, die dazu beitrugen, das Elend und die Folgen der Kriege und Diktatur zu überwinden. Die Werte und Formen einer instrumentalisierten „Demokratie“ wurden aus USA übersetzt und verbunden mit einem kapitalistischen Lebensstil, Medienkult und Konsumideologie. Die Vereinzelung und Zersplitterung aller sozialen Klassen, Schichten, Bürger und Interessen durch derartige Methoden sicherte den kleinen Gruppen in Wirtschaft und Staat die Macht. In den zwei, drei Grossparteien verwalteten und gestalteten ausgesuchte und überprüfte Eliten, Cliquen und Gruppen eine parlamentarische Demokratie, die den Widerspruch und die Konkurrenz der unterschiedlichen Demokratieformen nicht kannte. Die Wähler wurden zu den „Konsumenten“ und Zuschauern von Ereignissen, Debatten und politischen Szenen, ohne selbst entscheiden zu können. Eine „Einheitspartei“ inszenierte Demokratie als Spektakel.

Westdeutschland gewann ab Mitte der fünfziger Jahre über den Marshall – Plan durch eine „Wohlstandsgesellschaft“ sogar nachträglich gegenüber einzelnen West- und Oststaaten den II. Weltkrieg. Ohne die Unterstützung der USA wäre die Wiedervereinigung der zwei Deutschlands nach 1989 unmöglich gewesen. Umgekehrt half das geeinte Deutschland den USA, in Osteuropa, in Asien und Nordafrika Einflüsse zu gewinnen, um die Rohstoff- und Absatzmärkte zu sichern. Die enge Kooperation der deutschen und nordamerikanischen Wirtschaft war Ausdruck der Präsenz und der direkten Eingriffe der USA. Umgekehrt profitierten die deutschen Märkte von der Dynamik und der Politik Nordamerikas. Allerdings vermieden die deutschen Regierungen, sich in die Interventionskriege dieser Grossmacht hineinziehen zu lassen. Weder in Korea, in Vietnam, im Irak, in Syrien kämpften deutsche Truppen oder Legionäre. Der Krieg in Afghanistan dokumentierte eine ersten „Waffenbrüderschaft“ und es ist zu vermuten, dass ein Angriff auf den Iran eine deutsche, militärische Teilhabe verzeichnen würde. Die Bundesrepublik stabilisierte im Sinne der USA Westeuropa und erleichterte den Zusammenbruch des „Kriegskommunismus“ in Osteuropa. Trotzdem wiesen beide Mächte eine eigene und andere Tradition von Wirtschaft und Politik auf. In der Gegenwart scheint die zerstörerische Kraft des Finanzkapitals dieses „Bündnis“ und die Stabilität der gemeinsamen Ziele zu untergraben.

Der erste Kanzler der Bundesrepublik Deutschland, Konrad Adenauer, setzte auf eine enge Zusammenarbeit mit den USA, um einen neuen, deutschen Teilstaat aus den Resten bzw. Trümmern der NS – Diktatur und der preussischen Tradition zu begründen. Ihm war zugleich wichtig, die westdeutsche Wirtschaft technologisch zu erneuern und über eine Wirtschaftskonjunktur, die „Eingliederung“ der vielen Flüchtlinge, Ausgebombten und „Heimkehrer“ zu gewährleisten. Aus dem Schutt der NSdAP zwei Grossparteien zu errichten und zu zwei politischen, fast „identischen“ Lagern zu fügen, ohne der NS – Ideologie einen Auftrieb zu geben, konnte ohne die USA nicht gelingen. Diese Grossmacht verzichtete auf eine „antifaschistische Neuordnung“, die in Potsdam zwischen der UdSSR und den Westalliierten ausgehandelt wurde und stützte sich auf deutsche Kämpfer und „Partisanen“ aus den Wehrmachtverbänden, der GESTAPO und der SS, um einen russischen Angriff abwehren zu können. Präsident Harry Truman und sein Geheimdienstchef Allan Dulles waren überzeugt, dass die russische Gegenmacht die revolutionären Unruhen in China, Indien, Persien, Griechenland, Westeuropa und Afrika ausnutzen würde, um mit den kampferprobten Panzerverbänden bis zum Atlantik vorzustossen. Die deutschen Kämpfer sollten einen Partisanenkrieg eröffnen und die Rote Armee aufhalten, bis die nordamerikanischen Bomberverbände den Vormarsch zusammemschiessen würden. Eine Geheimarmee, Gladio, von ein paar zehntausend Mann, wurde mit amerikanischen Waffen und Offizieren ausgerüstet. Die USA als Siegermacht schienen mit dem Anspruch der Freiheits- und Menschenrechte die Anschauungen eines „Führerstaates“ und die Utopien der kommunistischen Ideologie endgültig zu widerlegen und durch den materiellen Realismus einer Konsumgesellschaft, des Wohlstands und der wehrhaften Demokratie zu begründen. Endlich „kämpfte“ das westliche Restdeutschland auf der richtigen Seite.

Im Sog dieser geheimen Militarisierung des entstehenden „Kalten Krieges“ entdeckte der ersten Bundeskanzler der deutschen Westrepublik die Chance, aus den unverbrauchten „Resten“ des deutschen Volkes und aus den produktiven Beständen von Wirtschaftsfachleuten, Managern, Militär und Sicherheitsdiensten einen neuen Staat aufzubauen. Die katholische Bourgeoisie des Rheinlandes, Schwabens und Bayerns sollte das soziale Fundament des neuen Staates abgeben. Die katholische und christliche Arbeiterbewegung, alles tapfere Soldaten und Facharbeiter, sollten die bürgerlichen Ansprüche ergänzen und zu einer Bündnis- und Volkspartei vereinen. Der Antipreusse Adenauer nahm die Reform- und Bündnispolitik des preussischen Staates auf, internationalisierte sie jedoch durch den europäischen Katholizismus, der die Grundlagen des europäischen Faschismus und deutschen Nationalsozialismus pragmatisch und ideologisch überwinden sollte. Ihm war zugleich wichtig, den Staat Israel anzuerkennen und eine Politik der Wiedergutmachung an den Juden einzuleiten, um zu vermeiden, dass die zionistischen Kreise in Israel, Europa oder USA Front bezogen gegen den westdeutschen Teilstaat. Der neue Bundesstaat und die Kanzlerdemokratie waren auf die Unterstützung der USA angewiesen, um das Experiment der Neugründung mit den alten, belasteten Beamten und Funktionären zu starten und die politischen Wurzeln einer „Volkspartei“, der CDU/CSU zu stabilisieren, die gerade nicht eine Fluchtburg der Parteigenossen der NSdAP werden sollte. Dieses doppelte Experiment einer Staatsgründung und der Formierung einer Parteiendemokratie gelang, weil der Kanzler Adenauer den Auflagen des Besatzungsstatutes, der „Kanzlerakte“ und der Verträge mit den USA genügte. Er spielte den „Kanzler der Alliierten“, wie Kurt Schumacher höhnte, und erschuf aus den Trümmern der deutschen Kriegswirtschaft und des totalen Staates eine neue Ordnung und Ökonomie. Diese Politik folgte den Direktiven und Vorbehalten der USA und besass trotzdem eine deutsche Tradition. Die Bündnis- und Reformpolitik, die Verbindung von Sozial- und Sicherheitsstaat, die staatliche Konjunkturpolitik, das weitgefächerte Bildungsprogramm, der wachsende Wohlstand, die Einrichtung einer „nivellierten Mittelstandsgesellschaft“, der soziale Aufstieg eines geschundenen Volkes nahmen die Tradionen Preussens und der „deutschen Reiche“ seit 1871 auf.

Die Bundesrepublik überrundete sehr schnell Frankreich und England. Es mussten keine Koloialkriege geführt werden. Ausserdem musste kein „Kolonialreich“ finanziert werden. Es war nicht nötig, die vielen Wirtschaftsflüchtlinge aus Nordafrika und dem „Empire“ aufzunehmen. Die Bundesrepublik verfügte über das Fachwissen und den Aufbauwillen eines Restvolkes, das die Wirtschaftsräume Ostdeutschlands und Osteuropas aufgeben musste. In Westeuropa behinderten die Kolonien ein „Neubeginnen“. Stattdessen siedelte Nordafrika in Südfrankreich und Kalkutta breitete sich in London und Manchester aus. Die Kolonialkriege erreichten die „Mutterländer“ und destabilisierten Wirtschaft und Politik. England und Frankreich verloren nachträglich den II. Weltkrieg und waren auf die Wirtschaftskraft der Bundesrepublik angewiesen, um selbst ein labiles Gleichgewicht zu halten. General De Gaulle bewunderte deshalb den Kanzler Adenauer und wollte die westdeutsche Politik aufnehmen und erweitern in ein Europa der „Vaterländer“. Nach diesem Muster sollte eine „Europäische Union“ errichtet werden. Die Bundesrepublik wurde zum wirtschaftlichen und kulturellen „Drehpunkt“ des neuen Europas erklärt. Eine derartige „Integration“ lag durchaus im Interesse des nordamerikanischen Finanzkapitals. Vorerst musste deshalb eine neue Ostpolitik eingeleitet werden, um Russland und Osteuropa zu destabilisieren.

Die beiden Deutschlands, die Bundesrepublik und die DDR, wurden in den Plänen der NATO und des Warschauer Paktes als Regionen des Krieges, des Aufmarsches und des Einsatzes von Raketen gesehen. Diese beiden Deutschlands wären in eine Mondwüste bei Ausbruch des modernen und totalen Krieges verwandelt worden. Die westdeutschen Kanzler und die Staatsratsvorsitzenden der DDR wussten, welchem Zwang und welcher Verantwortung sie ausgesetzt wurden. Die USA beobachteten misstrauisch die Angebote Stalins an den Kanzler Adenauer, die deutsche Einheit und einen Friedensplan zu riskieren. Er lehnte ab, denn die USA hielten die Bundeswehr, den Bundesnachrichtendienst und die Regierung unter Kontrolle. Die Nato- und die Wirtschaftsverträge nahmen neben dem Besatzungsrecht und den Stationierungsauflagen der Bundesrepublik die Souveränität. Adnauer verhandelte mit Nikita S. Chrustchew Mitte der fünfziger Jahre über die Rückkehr der deutschen Kriegsgefangenen. Erste Handelsverträge wurden geschlossen. Ludwig Erhardt weigerte sich, die Kriegspolitik der USA in Vietnam und im Nahen Osten in den sechziger Jahren zu unterstützen. Die Studentenrevolte war ihm willkommerner Anlass, vor einem Kriegseinsatz deutscher Soldaten im Ausland zu warnen. Die Regierungen unter den Kanzlerschaften von Georg Kiesinger und Willy Brandt setzten die Adenauerpolitik fort, denn die Sozialdemokratie hatte die „List der Vernunft“ des alten Kanzlers übernommen und sie war wie die CDU daran interessiert nach 1961, nach dem Mauerbau in Berlin, die Kriegsfronten im Osten durch einen Reform- und Gullaschkommunismus aufzuweichen. Die Verwestlichung der Oststaaten und der DDR lag durchaus im Interesse der USA und im Kalkül der finanzkapitalistischen „Doppelmacht“.

Erst 1989, beim Zusammensturz des Kriegskommunismus, traten Widersprüche auf. Kanzler Helmut Kohl wurde von der US – Regierung und vom Finanzkapital auf die Chancen der „deutschen Einheit“ aufmerksam gemacht. Es wurde wichtig, die Generalität und das Offizierkorps der „Volksarmee“ und der „Sovetskaja Armija“ abzufinden und ihnen den Verteidigungswillen zu nehmen. Noch wichtiger wurde es, dem Geheimdienst, KGB, MfS und HVA, neue Aufgaben in der Wirtschaft zu übertragen, ohne eine „revolutionäre Rachejustiz“ einzuleiten. Nicht vergessen werden durfte, die Parteiführung von SED und KPdSU zu schonen und ihre Legalisierung in einer neuen Republik zu gewährleisten. Die Formel der „friedlichen Revolution“ im Osten umschrieb die Manöver, den alten Führungskadern aus Politik, Militär und Sicherheit im Osten Straffreiheit zu gewähren und sie unterzubringen im Sozialstaat und in der Wirtschaft. Voraussetzung dafür war, die entstehende „soziale Revolution“ aufzuhalten und stattdessen die Ordnung der alten Bundesrepublik als Rechtsstaat und als Parteiendemokratie in den Osten zu überführen. Gelang diese „Transformation“ der BRD in die DDR, konnte sie in Osteuropa und in Russland als Programm der „Demokratisierung“ wiederholt werden. Diese Vereinigung der beiden Deutschlands und der beiden Europas kostete mehrere hundert Milliarden DM. Weitgehend die deutsche Wirtschaft brachte diesen Betrag auf und wurde belohnt mit neuen Absatzmärkten, Immobilien und billigen Industrieinvestitionen. Als Verhandlungsführer dieser komplizierten „Übertragung“ wirkte im Auftrag von Helmut Kohl der Staatssekretär Schäubele, heute Finanzminister und Geburtshelfer eines europäischen Einheitsstaates.

Irgendwann nach 1990 entstanden Gegensätze in den politischen Perspektiven des europäischen Kontinents gegenüber der Weltmacht USA. Als finanzkapitalistische und politische Doppelmacht waren die USA an der Zerschlagung Russlands als Grosstaat, Imperium, Kultur, Rohstoffreserve, Industriegigant und asiatische Gegenmacht interessiert. Russland sollte in viele Kleinstaaten zerlegt werden. Die wichtigen Rohstoffregionen sollten durch nordamerikanische Konzerne besetzt werden. Die ehemaligen, russischen Sateliten sollten durch nordamerikanische Stützpunkte und Finanzhilfen unter die Hegemonie der USA gestellt werden. Vor allem Deutschland musste dagegen am russischen Teilmarkt interessiert sein. Wie nach 1871 waren deutsche Investitionen und industrielle Aufbauhilfen gefragt, um den alten morbiden Planstaat, den Sicherheits- und Militärapparat zu überwinden. Die Kombination von Staatskapitalismus, kapitalistischer Grosswirtschaft und Handel, von Mittelstand- und Sozialspolitik und der Einführung einer weitgefächerten Berufsbildung boten Alternativen zum „Kriegskommunismus“, aber auch zur Negativkraft des Finanzkapitalismus, dessen Zerstörungswut in USA und Südeuropa zur Deindustrialisierung, zur Massenarmut, Arbeitslosigkeit und zur Prassucht der Superreichen verleitet hatte. Die „Negation“ der Aufbauarbeit oder das Fehlen einer „neuen Schaffenskraft“, aus den Trümmern neue Initiativen, Technologien und produktive Ansätze zu „zaubern“, wiesen auf eine tiefe Krise der finanzkapitalistischen Spekulation. Der Verlust an Möglichkeiten oder die Realität einer „negativen Aufhebung“ des Kapitalismus auf kapitalistischer Grundlage belegten den Einbruch aller Potenzen. Eroberungskriege wiesen auf einen letzten Ausweg. Selbst die neuen Rohstoff- und Erdölfunde in den USA und die Hineinnahme der europäischen und deutschen Bildungs- und Wirtschaftskraft zum Neuanfang einer Industrieproduktion demonstrierten den grundlegenden Widerspruch, dass der US – Staat die Zerstörungswut des Finanzkapitals nicht länger zügeln konnte. Oder war zu erwarten, das die lateinamerikanischen und afrikanischen Völker in USA das „Steuer“ herumrissen und einen neuen Reform- und Gesundheitsstaat schufen und der finanzkapitalistischen Spekulation Aufsicht und Regulation aufzwangen? Der europäische Kontinent und hier Deutschland und Russland würden aus der kombinierten staats- und privatkapitalistischen Wirtschaft und vor allem aus einer „Revolution von oben“ neue Anfänge hervorbringen.

Diese Alternativen sind öffentlich kaum diskutierbar, weil die Medien, die Parteien und die Politik, die „Negativkräfte“ der fianzkapitalistischen Spekulation in Südeuropa, in Griechenland und USA nicht erörtern und darstellen. Darüber darf nicht gesprochen werden. Die Überwindung oder „Abschaffung“ der Arbeiterbewegung in Deutschland hat alle Konflikte und gegensätzliche Interessen eingeebnet. Die Forschungsinstitute der Parteien und Universitäten sind angewiesen, über den „Negativfaktor“ Finanzkapital keinerlei grundlegende Analysen zu erheben. Die Medien hüllen sich in „Schweigen“ oder in vagen Andeutungen. Es bleibt trotzdem erstaunlich, dass die Hintergründe der aktuellen Krise nicht benannt werden dürfen. Das mag an der Doppel- bzw. Parallelmacht des Finanzkapitals liegen, das über „Logen“, Geheimbünde, Absprachen, Verschwörungen Staat und Wirtschaft durchziehen und die Medien beherrschen. Die devoten Eliten in Parteien und Staat wagen es nicht, aufzubegehren, um ihren Lebensstandard und ihre Position nicht in Frage zu stellen. „Verschwörungen“ bringen letztlich keinerlei Lösung. Sie verstärken ein Chaos durch Entscheidungslosigkeit der Eliten oder durch eine „Paralyse“, die die gesamte Gesellschaft erfasst. Schon deshalb werden Ereignisse auftreten, die wie ein Befreiungsschlag wirken werden.

Mit der nordamerikanischen Doppelmacht des Finanzkapitals ist nicht etwa eine „jüdische Plutokratie“ oder eine „jüdische Weltherrschaft“ gemeint. Diese Form des Kapitalismus lässt sich nicht auf eine Ethnie festschreiben. Die antisemitische Polemik eines Joseph Goebbels diente dem Weltmachtanspruch der NS – Diktatur und entbehrte jeder wissenschaftlichen Grundlage. Dass es auch jüdische Banker und Spekulanten gibt, verleiht diesem Kapital nicht ein irgendwie „jüdisches Wesen“. Der Finanzkapitalismus folgt einer geldspezifischen und finanzpolitischen Logik, die sich aus der „Struktur“ des Geldes, der Spekulation, der Aktie, des Fonds, der Börse, des Handels usw. ergibt. Selbst der Existenzkampf des israelischen Staates hat mit den finanzkapitalistischen Operationen wenig zu tun. Allerdings liegt er in einer Region, deren Bodenschätze für die Spekulation interessant sind. Kurzschlüsse in die skizzierte Richtung zu vollziehen, lässt sich aus den anwachsenden okkultischen Strömungen im modernen Kapitalismus erklären, einen „Schuldigen“ oder das „Böse“ schlechthin zu finden.

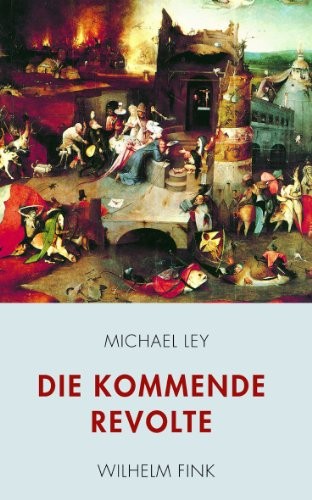

Der Multikulturalismus als postmoderne Ideologie und Alternative zum homogenen Nationalstaat – soweit meine Behauptung – erwies sich als gesellschaftspolitische Sackgasse, als eine realitätsferne Utopie. Die mühsame Überwindung der nationalen Kulturalismen wurde durch die unreflektierte Aufnahme anderer Kulturen und Religionen konterkariert. Alle Erfahrungswerte klassischer Einwanderungsländer wurden konsequent negiert, um eine vielfach von vornherein zum Scheitern verurteilte Integration zu bewerkstelligen. Die Integration von Migranten – ausgenommen Asylsuchende! – kann sinnvollerweise nur nach Maßgabe ihrer beruflichen Qualifikation und der Bedürfnisse der aufnehmenden Gesellschaften erfolgen. Historisch integriertkeine Gesellschaft in Friedenszeiten Menschen anderer Kulturen in größerem Umfang aus anderen als ökonomischen Gründen. Ausnahmen waren immer nur politisch, ethnisch und religiös Verfolgte.

Der Multikulturalismus als postmoderne Ideologie und Alternative zum homogenen Nationalstaat – soweit meine Behauptung – erwies sich als gesellschaftspolitische Sackgasse, als eine realitätsferne Utopie. Die mühsame Überwindung der nationalen Kulturalismen wurde durch die unreflektierte Aufnahme anderer Kulturen und Religionen konterkariert. Alle Erfahrungswerte klassischer Einwanderungsländer wurden konsequent negiert, um eine vielfach von vornherein zum Scheitern verurteilte Integration zu bewerkstelligen. Die Integration von Migranten – ausgenommen Asylsuchende! – kann sinnvollerweise nur nach Maßgabe ihrer beruflichen Qualifikation und der Bedürfnisse der aufnehmenden Gesellschaften erfolgen. Historisch integriertkeine Gesellschaft in Friedenszeiten Menschen anderer Kulturen in größerem Umfang aus anderen als ökonomischen Gründen. Ausnahmen waren immer nur politisch, ethnisch und religiös Verfolgte.

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

„

„ Parallel zu seiner

Parallel zu seiner

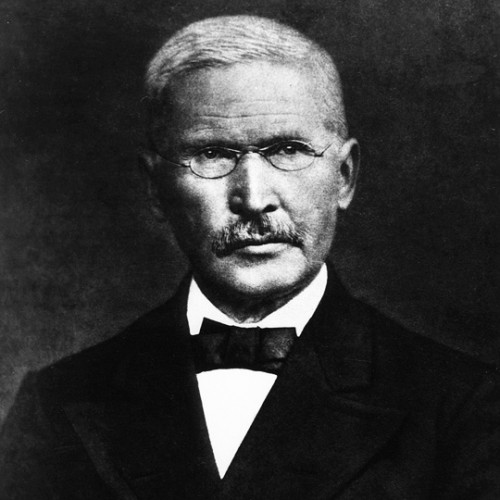

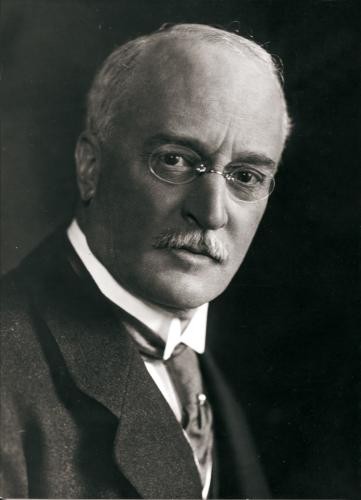

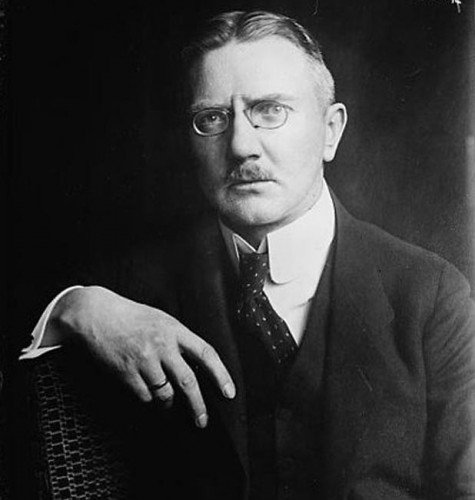

Es war ein ruhiger Abend auf See. Rudolf Diesel hatte im Speisesaal des luxuriösen Passagierdampfers “Dresden” mit einem bekannten Industriellen zu Abend gegessen. Der große, stattliche Mann mit Brille und Schnauzer war auf dem Weg nach London, wo er ein Motorenwerk einweihen sollte. In bester Laune hatte der 55-Jährige vom Deck aus noch die sternklare Nacht vom 29. auf den 30. September 1913 bewundert. Dann machte sich Rudolf Diesel, der Erfinder des Dieselmotors, auf den Weg in seine Kabine. Dies war der Augenblick, in dem er das letzte Mal gesehen wurde.

Es war ein ruhiger Abend auf See. Rudolf Diesel hatte im Speisesaal des luxuriösen Passagierdampfers “Dresden” mit einem bekannten Industriellen zu Abend gegessen. Der große, stattliche Mann mit Brille und Schnauzer war auf dem Weg nach London, wo er ein Motorenwerk einweihen sollte. In bester Laune hatte der 55-Jährige vom Deck aus noch die sternklare Nacht vom 29. auf den 30. September 1913 bewundert. Dann machte sich Rudolf Diesel, der Erfinder des Dieselmotors, auf den Weg in seine Kabine. Dies war der Augenblick, in dem er das letzte Mal gesehen wurde.

SEZESSION:

SEZESSION:  SEZESSION:

SEZESSION:

Every established intellectual, politician or media company moves inside this totalitarian liberal system. For example you will not find any established political party in the German parliament that doesn´t claim to be “also liberal”. Our universities “research” about “identities”, “gender”, and “culture” to change this or that. The new liberal types of human being don´t have a heritage, homeland or cultural identity. Even the gender can be changed. We could consider that as a type of slapstick comedy if it wouldn´t be so serious, because it means a type of destruction of basics and values, which might be hard to repair.

Every established intellectual, politician or media company moves inside this totalitarian liberal system. For example you will not find any established political party in the German parliament that doesn´t claim to be “also liberal”. Our universities “research” about “identities”, “gender”, and “culture” to change this or that. The new liberal types of human being don´t have a heritage, homeland or cultural identity. Even the gender can be changed. We could consider that as a type of slapstick comedy if it wouldn´t be so serious, because it means a type of destruction of basics and values, which might be hard to repair.