dimanche, 27 mai 2012

Martin Heidegger e la Rivoluzione conservatrice

Giorgio Locchi:

Martin Heidegger e la Rivoluzione conservatrice

SULLA "RIVOLUZIONE CONSERVATRICE" IN GERMANIA

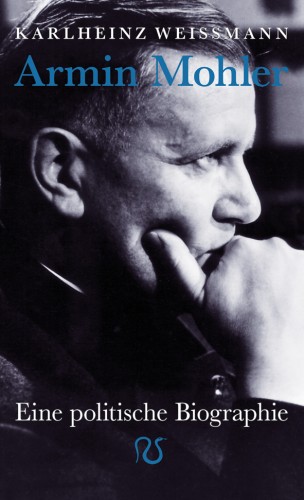

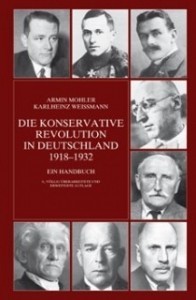

Armin Mohler utilizzò l'espressione "Rivoluzione conservatrice", introdotto da Thomas Mann e Hugo von Hofmannsthal, per designare un ampio, complesso e, sotto il profilo dottrinario, variegato insieme di tendenze politiche, letterarie, filosofiche, artistiche, che, tra il 1918 e l'avvento del Nazionalsocialismo al potere, criticarono da Destra sia la Repubblica di Weimar e le dottrine democratico-liberali in genere. sia le ideologie social-comunistiche, nonostante certi sconfinamenti di alcune sue espressioni anche verso questi due ultimi orizzonti ideologici. Si trattava comunque di tendenze che avevano quale proprio minimo comune denominatore la critica alla "civiltà illuministico-borghese", ricollegandosi in ciò al Neo-romanticismo di fine Ottocento, e alle "idee del 1789", senza ripetere, però, pedissequamente. i temi già fatti valere dal pensiero Controrivoluzionario e Reazionario, in seguito ad una più attenta considerazione delle conseguenze derivanti dalla cosiddetta "modernizzazione".

Lo scritto di Mohler, Die Konservative Revolution in Deutschland. 1918-1932. Ein Handbuch, frutto di una ricerca per la tesi di laurea, fu pubblicato nel 1950 e, in seconda edizione, nel 1972. Per la traduzione italiana abbiamo dovuto aspettare il 1990. grazie alle Edizioni Akropolis e La Roccia di Erec. Purtroppo, la ricezione non è stata pari quanto meno all'attesa di quella traduzione, molto probabilmente perché si attendeva un testo di dottrina politica, mentre si tratta per lo più di un testo di filosofia della politica, quindi, bisognoso di un pubblico molto più coltivato culturalmente.

Se non proprio il termine "Rivoluzione conservatrice", espressioni analoghe sono ricorrenti in vari teorici — penso, ad esempio, a Sergio Panunzio — che le utilizzarono per designare il significato complessivo delle rivoluzioni nazionali che negli anni Venti e Trenta portarono al governo di importanti Stati europei, tra cui l'Italia, governi di ispirazione fascista. Si interessarono direttamente ad Autori riconducibili alla Rivoluzione conservatrice tedesca, Evola. Delio Cantimori, V. Beonio Brocchieri, Lorenzo Giusso e, anche se in chiave critica, Balbino Giuliano e Guido Manacorda.

Nel dopoguerra, nell'ambito della cosiddetta "Cultura di destra", l'attenzione al movimento meta-politico qui considerato, non poteva non passare attraverso la ricostruzione del Mohler. Possiamo ricordare di Stefano Mangiante, La cultura di destra in Germania ("Ordine Nuovo", n. 1-2, 1965) e gli scritti di un altro studioso, anch'esso scomparso prematuramente, ossia di Adriano Romualdi, la cui tesi di laurea discussa con Renzo De Felice, venne pubblicata postuma nel 1981, con il titolo Correnti politiche ed ideologiche della destra tedesca dal 1918 al 1932.

Profondo conoscitore della cultura tedesca, Giorgio Locchi si interessò a più riprese della Rivoluzione conservatrice e di quelli che devono senz'altro essere considerati come i due ispiratori principali di essa: Friedrich Nietzsche e Richard Wagner. Il saggio che qui di seguito viene riproposto, venne pubblicato dal periodico "La Contea" (N° 34). Locchi discusse del libro di Mohler nell'articolo La Rivoluzione conservatrice in Germania, pubblicato ne "La Destra" del gennaio 1974.

MARTIN HEIDEGGER E LA RIVOLUZIONE CONSERVATRICE

Il dibattito sul cosiddetto "caso Heidegger, recentemente ridivampato in Francia e di là un po' ovunque in Europa, ha dimostrato soprattutto questo: che il confronto col pensiero dì Heìdegger costituisce un'imperiosa necessità per chiunque, scevro da illusioni, si interroghi sui fondamentali problemi dei nostri tempi e sul destino delle genti d'Europa. Ma anche va dimostrato che del pensiero di Heìdegger circolano, dominando imperterrite, interpretazioni (sempre fondate su un aspetto particolare, isolato dal generale contesto), che lo stesso Heidegger ha più volte sdegnosamente confutate e rigettate: esistenzialismo, nichilismo, misticismo, pseudo-teologia, "rifiuto della Tecnica" e così via. Chiedersi — cito il titolo di un dibattito televisivo francese — se "esista un legame tra il pensiero di Essere e Tempo (1927) e l'adesione di Heidegger al Partito Nazionalsocialista 1 1933)", chiedersi cioè se esista un legame tra l'analitica heideggeriana dell'esistenza storica delFuomo e la visione del mondo nazionalsocialista, z interrogazione che presuppone una conoscenza genuina e non già un'interpretazione abusiva o pretestuosa del pensiero di Heidegger, così come d'altra parte esige una visione non riduttrice del Nazionalsocialismo e della sua Weltanschauung.

Quel che non cessa dì sorprendere in tutti gli studi dedicati al pensiero di Heidegger è il fatto che, sempre, la seconda conclusiva sezione di Essere e Tempo testo fondamentale, è totalmente ignorata, come "non letta". L'attenzione degli studiosi e degli interpreti si fissa sulla critica heideggeriana della concezione "metafisica" dell'essere come presenza (Anwesenhei) e sul primo approcio ancora puramente descrittivo della fenomenalità del Dasein, allorquando — e non fosse che per davvero comprendere quella critica e penetrare quella enomenalità — dovrebbe soprattutto soffermarsi sulla concezione che Heidegger espone della temporalità del Dasein, dell'esistenza istoriale dell'uomo. La tanto discussa e, dai più, tanto esaltata guanto malcompresa "rottura" con la "Metafisica"

occidentale scaturisce in effetti proprio da questa nuova concezione della temporalità. È questa concezione della temporalità a fondare la visione heideggeriana della storia ed è dunque in essa e a partire da essa che va eventualmente ricercata la natura del rapporto esistente tra il pensiero di Heidegger e la "visione del mondo" nazionalsocialita. Esprimerò subito, per evitare ogni pur comoda ambiguità, la mia convinzione: questa parentela esiste, è quanto mai intima e. nella sua articolazione, spiega l'adesione attiva dell'autore di Essere e Tempo alla NSDAP e la sua fervida partecipazione alle attività del regime su un piano non soltanto universitario (1933-34). L'abbandono del rettorato e di ogni attività politica a partire dalla seconda metà del 1934 coincidono con una evoluzione di pensiero che progressivamente conduce Heidegger, sempre formalmente membro della NSDAP, su posizioni critiche nei confronti del regime: ma la sua critica resta critica all'interno e non comporta mai, neanche nel dopoguerra, la minima concessione alle ideologie democratiche, la minima simpatia per gli avversari del Terzo Reich.

ROTTURA CON LO SPIRITO DELL'OCCIDENTE

La "rottura" di Heidegger col pensiero filosofico tradizionale dell'Occidente, cioè — come egli diceva — con la "Metafisica" occidentale, è stata recepita dalla filosofia cattedratica come un novum clamoroso, come una svolta storica del pensiero europeo. Heidegger stesso lo ha creduto e, si può dire, orgogliosamente proclamato. Ma, di fatto, la sua "rottura" con la Metafisica altro non è, quando è proclamata, che l'aspetto "moderno" di una rottura con lo "spirito dell'Occidente" propria di tutta una corrente dì pensiero emersa nella seconda metà del XIX secolo, corrente che, con riferimento a Nietzsche, possiamo chiamare "tendenza sovrumanista" in opposizione alla bimillenaria tendenza egalitarista che, con il suo inerente inconscio nihilismo, ha conformato e conforma il destino dell'Occidente. Preannunciata in una delle "due anime" viventi nel petto dei Romantici, questa tendenza sovrumanista trova infatti, in rottura con lo spirito dell'Occidente, la sua prima manifestazione storica nell'opera artistica e negli scritti "metapolitici" di Richard Wagner. Dopo Wagner e, pretestuosamente, contra Wagner, Nietzsche rivendica a sé il merito della "rottura", proclamandosi "dinamite della storia", fondatore del movimento che dovrà opporsi al bimillenario nihilismo dell'Occidente giudeo-cristiano. Ereditata ora da Wagner ora da Nietzsche, la rottura investe già all'inizio di questo secolo larghissima parte della cultura tedesca, che Ernst Tròltsch potè così opporre allo "spirito occidentale", e sfocia più tardi, dopo la prima guerra mondiale, non soltanto in Germania ma quasi ovunque in Europa, nelle varie correnti letterarie, artistiche, ideologiche e infine politiche d'una "Rivoluzione Conservatrice", di cui, a dispetto di quanto si vorrebbe far credere, sono parte integrante i vari movimenti fascisti.

Evidentemente ciò che permette di accomunare Wagner e Nietzsche e Heidegger ed i tanti autori e movimenti della "Rivoluzione Conservatrice" (giustificando l'uso di questo termine generico) non è certamente una filosofia, non è una ideologia in senso stretto, bensì — per così dire a monte di "ideologie" o filosofie quanto mai diverse e magari divergenti — un comune sentimento, una comune intuizione dell'uomo, della storia e del mondo, che drasticamente si oppone alla concezione che tradizionalmente fonda e sottende teologie, filosofie, ideologie, strutture politiche del cosiddetto "Occidente". La tendenza sovrumanista, cioè la rottura con la dominante tradizione occidentale, si manifesta sempre come "rivolta contro il mondo moderno", come condanna del nostro presente epocale e volontà di opporsi ad una situazione obbiettiva interpretata come trionfo del "nihilismo" e rovinoso declino dell'Europa. Di qui l'esigenza di una rivoluzione radicale, che peraltro anche è concepita come un rinnovamento delle origini: tratto politicamente essenziale che permet-

te di distinguere nel modo più netto ciò che è Rivoluzione Conservatrice e Fascismo da ciò che è soltanto o "reazione" o "conservatismo" o "progressismo".

UN RINNOVAMENTO DELLE ORIGINI

La visione della storia che da Wagner e Nietzsche fino alla Rivoluzione Conservatrice determina la "rivolta contro il mondo moderno" — come ho gin indicato — trova il suo fondamento in una nuova intuizione dell'uomo, della storia e del mondo. Questa intuizione nuova è, nella sua radice, intuizione della tridimensionalità della temporalità del Dasein, della "istorialità" umana. Armin Mohler. nel suo fondamentale studio sulla Rivoluzione Conservatrice in Germania, ha esaurientemente dimostrato che, alla concezione unidimensionale e "lineare" del tempo, Nietzsche e gli autori conservatori-rivoluzionari oppongono una concezione tridimensionale del tempo-della-storia. A dir vero. parlare a proposito di Nietzsche e di questi autori di una "concezione" della tridimensionalità del tempo è improprio: intuita, la tridimensionalità del tempo, al pari di tutte le "idee" che ne discendono. è affermata non già concettualmente, bensì con ricorso ad un Leitbild suggestivo ed evocatore, ad una "immagine conduttrice", quella della "Sfera" temporale (da non confondere, come quasi sempre avviene, col "cerchio" o "anello", proiezione della Sfera nel tempo unidimensionale della "sensorialità"). Questo ricorso a "immagini" si imponeva — come ha ben visto Mohler — perché il linguaggio ricevuto è, nella sua "razionalità", tutto impregnato della concezione unidimensionale del tempo ed ad essa dunque obbedisce. Un aspetto peculiare della grandezza di Heidegger sta proprio nel suo tentativo, intrapreso con Essere e Tempo, di destrutturare il linguaggio ricevuto e ricreare un linguaggio nuovo al fine, per l'appunto, di concettualizzare la tridimensionalità della temporalità storico-esistenziale, nonché le "idee" che essa immediatamente genera.

Nella misura in cui si constatò incompreso. Heidegger finì col giudicare fallito il tentativo di Essere e Tempo e ripiegò più tardi su una Sage, su un "dire mito-poetico" che, a parer mio, è stato icor più mal compreso, provocando non pochi Iuívoci e abbagli. La novità rivoluzionaria del nguaggio filosofico di Heìdegger spiega vera-lente l'incomprensione che oggi ancora circonda 'argomentazione conclusiva di Essere e Tempo e n particolare — qui potremmo ironicamente innotare: come è logico — il quarto ed ì] quinto capitolo della seconda sezione, rispettivamente dedicati a "Temporalità e Quotidianeità" ed a "Temporalità e Istorialità". Chi peraltro riesce a penetrare il linguaggio di Essere e Tempo e saprà fare propria, eventualmente sviluppandola, la concettualizzazione della temporalità tridimensionale, anche avrà trovato la chiave che meglio di qualsiasi altra permette di comprendere i "discorsi" della Rivoluzione Conservatrice ed i fenomeni politici da questa generati e cioè in primo luogo di comprendere la "razionalità", fondamentalmente diversa da quella della "Metafisica".

LA TEMPORALITÀ COME "SFERA"

Germanico Gallerani (nello scorso numero de "La Contea") ha creduto di poter opporre Heidegger, "uomo rivolto al passato", ad una Konservative Revolution, "rivolta al futuro". È vero l'esatto contrario: è proprio l'identico atteggiamento nei confronti di passato presente e avvenire il "sintomo" più appariscente della loro parentela spirituale. La Rivoluzione Conservatrice è rivoluzione perché "rivolta al futuro" e tuttavia "conservatrice" perché si richiama sempre ad un lontano "passato". Quanto ad Heidegger basti ricordare una sua definizione del Dasein, dell'uomo in quanto esistente istoriale: "un Essente, che nel suo essere è essenzialmente zukúnftig", cioè essenzialmente esistente nella dimensione temporale dell'avvenire. E proprio perché zukiinftig — spiega Heidegger — il Daseín "è cooriginariamente gewesend", esistente nella dimensione della "divenutezza", e "può dunque tramandare a sé stesso una possibilità ereditata e ad essa consegnarsi". Nel quadro della temporalità tridimensionale, della "istorialità", rivendicazione di un passato e progetto d'avvenire coincidono nel modo più intimo.

Il progetto avvenire che il Dasein sceglie nel "passato", contro altre, una possibilità di esistenza istoriale: "Il Daseín — esplicativamente aggiunge Heidegger — sceglie i suoì propri Eroi" e, cioè, sceglie tra le possibilità offerte dal "passato" (Vergangenheit) la sua propria "divenutezza" (Gewesenheit). Conservator-rivoluzionari e fascismi possono così progettare tutti, rivoluzionaria-mente, un "uomo nuovo" e. nondimeno, richiamarsi ad una passata possibilità d'esistenza: alla più lontana "germanità", alla `romanità" repubblicana o imperiale, ad una "cattolicità" confusa con l'origine della nazione e dei suoi antichi istituti imperiali o monarchici. Allo stesso modo, sul terreno puramente filosofico, Wagner si richiama alla ancestrale "religione" indoeuropea (di cui il "cristianesimo originario", "non giudaìzzato". sarebbe secondo lui una semplice evoluzione), Nietzsche ed Heidegger al pensiero pre-socratico ed Evola, drasticamente, ad una originaria "Tradizione" postulata in una nebulosa pre-istoria. La "rivolta contro il mondo moderno", l'assunto rivoluzionario sono determinati dalla natura stessa del "regresso in una passata possibilità d'esistenza istoriale", cioè dalla natura della "ripetizione" (Wiederholung): perché — così Heidegger — "la ri-petizione non intende far ritornare ciò che una volta è stato, bensì piuttosto offre una replica contraddittoria (erwidert) alla passata possibilità di esistenza" ed è così "simultaneamente, in quanto attualità, la revoca di tutto ciò che in quanto passato determina l'Oggí". "La ripetizione nè si affida al passato, nè mira ad un progresso, l'uno e l'altro essendonella attualità indifferenti all'esistenza istoriale". (Traducendo queste concezioni sul terreno della grande politica Martin Heidegger afferma nella sua Introduzione alla Metafisica che il popolo tedesco, "popolo di mezzo preso nella più dura tenaglia [tra America e Russia] e popolo più d'ogni altro minacciato", può realizzare il suo destino istoriale "soltanto laddove sappia creare in se stesso un'eco, una possibilità d'eco per la missione assegnatagli e comprenda creativamente la sua Tradizione" e cioè, "in quanto istoriale esponga, a partire dal centro del suo divenire storico, se stesso e con ciò la storia dell'Occidente nell'originaria regione delle potenze dell'Essere").

UNA "COMUNITÀ DI DESTINO"

L'atteggiamento di Heidegger nei confronti di "passato" e "attualità" ed "avvenire" non soltanto è essenzialmente identico — conforme — a quello della Rivoluzione Conservatrice e dei movimenti fascisti, bensì anche conferisce alla comune visione-della-storia un saldo fondamento concettuale. Quel che nel discorso conservator-rivoluzionario e fascista è ancora soltanto Leitbild, "immagine conduttrice", diviene con Heidegger concetto. Se in questa sede è evidentemente impossibile mostrare come per l'appunto l'analitica heideggeriana dell'esistenza istoriale concettualizzi, fondandosi sul principio della temporalità tridimensionale del Dasein, tutti i Leitbilder, tutte le "immagini conduttrici" della visione-del-mondo della Rivoluzione Conservatrice e dei movimenti fascisti, mi sembra nondimeno opportuno mettere qui in luce la traduzione concettuale che Heidegger offre di un Leitbild quanto mai rilevante, quello della "comunità di destino", ritrovata a seconda delle correnti o nel "popolo" o nella "nazione" o nella "razza" (questa a sua volta assai diversamente intesa).

E la temporalità tridimensionale dell'esistenza —afferma Heidegger — a "rendere possibile l'istorialità autentica, cioè quel che chiamiamo destino istoriale". Poiché il Dasein, in quanto essere-almondo, è anche co-essere, essere-con-Altri, ìl destino (Schicksal) di un Dasein è anche sempre Geschick, commesso destino comune, "la (cui) forza si libera grazie alla comunicazione ed alla lotta". Ora il "destino" scaturisce da una scelta istoriale pro-veniente dalla dimensione avvenire del Dasein: e nella comunicazione e nella lotta si riconoscono un comune destino coloro che hanno compiuto un'identica scelta istoriale e ad essa restano risolutamente fedeli. Ogni scelta istoriale implica però sempre la "ri-petizione", la "replica a una passata possibilità dell'esistenza istoriale" e, insieme, un "progetto d'avvenire". La "comunità di destino" si rivela dunque essa stessa costituita da una scelta istoriale (che è selettiva e che dunque può essere giudicata non-umanista da un punto di vista egalítarista). Questo significa che nazione popolo razza, in quanto comunità riconosciuta di

destino, se sempre costituiscono una replica contraddittoria (Erwiderung) della passata possibilità d'esistenza su cui si è portata la scelta istoriale, d'altro lato sempre hanno natura "pro-gettuale" e, nel presente oggettivo, restano un "da farsi", una "missione". La prassi politica dei regimi fascisti implica così una "disciplina selettiva" (Zucht, in tedesco) per l'appunto intesa a conformare il "materiale umano" dell'Oggi all'idea di nazione o popolo o razza scaturente dalla scelta istoriale compiuta. (In questo senso i fascismi sono "azione cui è immanente un pensiero" sempreché per pensiero si intendano insieme "ri-petizione" [nel senso che Heidegger dà a questo termine] e "progetto"). Altamente significativa e profonda è in questo contesto la distinzione che Heidegger introduce in Essere e Tempo fra "Tradition" e "Ueberlieferung", cioè — potremmo tradurre - fra "tradizione subita" e "tradizione scelta". "La tradizione — afferma Heidegger in Essere e Tempo — priva di radici l'istorialità del Dasein", essa "cela e addirittura fa dimenticare la sua stessa origine". La "Ueberlieferung", per contro, si fonda "espressamente sulla conoscenza dell'origine delle possibilità d'esistenza istoriale" e consiste nella "scelta" di una di queste possibilità, scelta che sempre proviene dalla dimensione avvenire del nostro Dasein. Solo una concezione del genere riesce a conciliare fedeltà alla tradizione e assunto rivoluzionario teso alla creazione di un "uomo nuovo".

IL "RETTORE DEI RETTORI"

Mohler, nel già citato saggio sulla Rivoluzione Conservatrice in Germania, mette espressamente tra parentesi il Nazionalsocialismo. Egli indica nondimeno che le correnti della Rivoluzione Conservatrice oggetto del suo studio vanno considerate "come i trotzkisti del Nazional socialismo". Implicitamente egli situa così il nazionalsocialismo al centro stesso della Rivoluzione Conservatrice così come dopo di lui ha fatto il marxista Jean-Pierre Faye (da non confondere col neo-destrista Guillaume Faye), che vede in Hitler "l'ospite muto" che accoglie in sé i discorsi che gli provengono dalla Destra e dalla Sinistra della Rivoluzione Conservatrice, tacitamente li sintetizza e, subito, li trasforma in azione. Conto tenuto di ciò e di quanto è stato precedentemente esposto, mi sembra ovvio affermare — così abbordando l'aspetto più concreto del dibattito suscitato dal libro di Farias — che lo Heidegger di Essere e Tempo va situato al centro del vasto campo della Rivoluzione Conservatrice e dunque su una posizione assai vicina a quella del movimento nazionalsocialita, quand'anche — inutile precisarlo - filosoficamente più "alta". Che dunque, al contrario di molti esponenti della Destra e della Sinistra della Rivoluzione Conservatrice, Heidegger non abbia scelto nel 1933 un settario distacco ed abbia invece prontamente aderito alla NSDAP ed attivamente partecipato poi per quasi due anni ad attività non soltanto politiche del regime, tutto ciò è non già frutto d'un abbaglio, d'una speranza mal riposta, del "fascino" subito nel contesto di un conturbante momento storico, bensì è frutto di una coerenza col proprio stesso pensiero e con le idee politiche a questo pensiero inerenti. Ciò non significa che nel 1933 tutte le idee politiche di Heidegger coincidano esattamente con quelle manifestate del discorso del nazionalsocialismo. È tuttavia evidente che, agli occhi di Heidegger, le differenze non investono l'essenziale: e — val la pena di osservare — neanche l'antisemitismo da sempre iscritto nel programma del partito fa ostacolo all'adesione.

L'evoluzione successiva ( a partire dalla seconda metà del 1934) dell'atteggiamento di Heidegger nei confronti del regime è certo avviata da contingenze umane, ma trova la sua causa profonda in una evoluzione di pensiero, quella stessa che indusse Heidegger ad abbandonare il "cammino" di Essere e Tempo, la cui annunciata seconda parte non fu dunque mai scritta. Lo Heidegger di Essere e Tempo aveva veduto nel movimento nazionalsocialista la traduzione politica dell'auspicata fine della Metafisica, cioè un sovvertimento della tradizione occidentale ed un superamento del nihilismo. Probabilmente egli si attendeva pertanto che il suo pensiero fosse riconosciuto dal regime come "filosofia del movimento". Avversato da altri universitari nazisti come il Krieck, protetti da

Rosenberg, Heidegger dovette abbandonare ogni speranza di imporre le sue idee in campo educativo e di divenire, come ad un certo momento era sembrato possibile, il "rettore dei rettori" delle Università germaniche. Nel 1935, un anno dopo le dimissioni dal rettorato, nel suo corso di introduzione alla Metafisica, egli ancora rivendicava al proprio pensiero, contro le varie "filosofie dei valori" alla Krieck, l'autentica comprensione della "intima verità e grandezza del movimento" nazionalsocialista, ritrovata "nell'incontro fra la Tecnica segnata da un destino planetario e l'uomo dei tempi nuovi". In questo stesso corso anche si annunciava però una critica del regime, che troverà in seguito la sua più compiuta seppur "cifrata" formulazione nella lettera Zur Seinsfrage (Sul problema dell'Essere) indirizzata a Ernst Jiinger nel 1953. È una critica — sia detto subito — che a mio avviso non situa Heidegger fuori dal vasto spazio della Rivoluzione Conservatrice. bensì - quanto meno nella trasparente intenzione dello stesso Heidegger — al di là dell'oggi in un "avvenire", che apparirà infine precluso alla volontà umana e potrà semmai soltanto essere concesso da "un dio".

SOLO UN "DIO" CI POTRÀ SALVARE

La "posizione" politica assunta dall'ultimo Heidegger deve essere messa in relazione con la sua interpretazione del pensiero di Nietzsche, la quale anche coinvolge la Rivoluzione Conservatrice (Jiinger) ed il movimento nazionalsocialista. Allo stesso modo in cui l'ultimo Nietzsche, dopo aver esaltato l'opera di Wagner, aveva voluto vedere in essa non già la promessa di una "rigenerazione" del mondo e della storia, bensì il "colmo della decadenza" ed una "fine", Heidegger ritiene fallito il tentativo nietzschiano di "dinamitare la storia" e "superare il nihilismo" occidentale. Secondo Heidegger, Nietzsche avrebbe il merito incontestabile di avere per primo "scoperto" e denunciato il "nihilsmo" della cultura occidentale, ma del nihilsmo non avrebbe saputo individuare la causa, situata a torto nel sovvertimento platonico-cristiano del "valori" anzichè nel-

l'oblio dell'Essere. Il pensiero di Nietzsche non costituirebbe dunque un superamento (Verwindung) della Metafisica, bensì capovolgerebbe la Metafisica stessa, portandola al suo ultimo compimento. Questa critica — non va dimenticato — ha un risvolto apologetico: in quanto ultima, più compiuta forma del metafisico oblio dell'Essere, il pensiero di Nietzsche costituisce nel giudizio di Heidegger un "passaggio obbligato", una ineludibile "necessità" sul cammino che potrebbe condurre al superamento della Metafisica e del nihilismo.

Nella citata lettera Zur Seinsfrage Heidegger proietta questa sua critica di Nietzsche sul "Lavoratore" jungeriano, interpretato come la moderna configurazione della Volontà-di-Potenza inerente al progetto di Nietzsche, e — non senza una segreta ironia nei confronti di Ernst Jiinger —sul regime nazionalsocialista in quanto realizzazione del progetto inerente al "Lavoratore" jùngeriano: ma questo anche significa che agli occhi di Heidegger la forma politica nazionalsocialista, in

quanto traduzione del capovolgimento nietzscheniano della Metafisica; supera storicamente la forma delle democrazie liberali o socio-comuniste. (Ovverosia, per dirla nel sinistrese di un LacoueLabarthe [cfr.: La Fiction da Politiquel: "Il nazismo è per Heidegger un umanismo che riposa su una determinazione dell'humanitas più possente di quella su cui riposa la democrazia, pensiero ufficiale del capitalismo, cioè del nihilismo secondo cui tutto vale").

Ai fini del dibattito aperto dal libro di Farias, poco importa qui la convinzione degli uni o degli altri che l'interpretazione di Heidegger costituisca o non costituisca una falsificazione del pensiero e della "posizione" di Nietzsche. Importante a questi fini è la spiegazione che essa offre dell'atteggiamento assunto da Heidegger nel dopoguerra e di quel suo "silenzio" che tanto esaspera il pretesto imperante "umanismo", proprio perché sostanzia un rifiuto di condannare chi, nel confronto coi suoi avversari, appare incondannabile.

00:05 Publié dans Nouvelle Droite, Philosophie, Révolution conservatrice | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : giorgio locchi, heidegger, révolution conservatrice, allemagne, philosophie, nouvelle droite, armin mohler |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

lundi, 21 mai 2012

Ein idealistischer Prophet der Tat

Ein idealistischer Prophet der Tat

Johann Gottlieb Fichte war nicht nur ein gewaltiger Tribun und einer der größten Philosophen, die die Welt je trug, er war vor allem auch ein bis ins letzte aufrechter, ja knorriger Mann, dem man nichts vormachen konnte. Man muß lesen, wie unnachsichtig er gegen alle Formen ziviler Geschmeidigkeit ankämpfte, wie abgrundtief seine Verachtung für beifallheischendes Literatengeschmeiß und karrierebedachte Katzbuckelei war und wie schneidend er diese Verachtung zu formulieren verstand.

Johann Gottlieb Fichte war nicht nur ein gewaltiger Tribun und einer der größten Philosophen, die die Welt je trug, er war vor allem auch ein bis ins letzte aufrechter, ja knorriger Mann, dem man nichts vormachen konnte. Man muß lesen, wie unnachsichtig er gegen alle Formen ziviler Geschmeidigkeit ankämpfte, wie abgrundtief seine Verachtung für beifallheischendes Literatengeschmeiß und karrierebedachte Katzbuckelei war und wie schneidend er diese Verachtung zu formulieren verstand.

Er war kleiner Leute Kind, Sohn eines Bandwirkers aus der Oberlausitz, hatte dank der Unterstützung des örtlichen Gutsbesitzers Haubold von Miltitz das berühmte Elitegymnasium Schulpforta besuchen können und danach jahrelang das Hauslehrer- und Hofmeisterschicksal der damaligen deutschen Intellektuellen geteilt. Es bedeutete für ihn viel, als er 1794 als Professor nach Jena berufen wurde, aber gerade diese Stelle verscherzte er sich bald wieder durch seine Unnachgiebigkeit.

Ein von ihm mit einem Nachwort versehener Artikel von Friedrich Karl Forberg im Philosophischen Journal hatte der Vermutung Ausdruck gegeben, daß die Existenz Gottes nicht notwendig sei für die Errichtung einer moralischen Wertordnung. Das hatte das äußerste Mißfallen diverser Obrigkeiten erregt, der berüchtigte „Atheismusstreit“ brach aus, Sachsen und Preußen drohten, die Universität Jena zu boykottieren und ihr sämtliche Fördermittel zu entziehen.

Meinungsfreiheit aus Prinzip

Fichte stimmte nicht mit dem fraglichen Aufsatz überein, doch um des Prinzips der wissenschaftlichen Freiheit willen warf er sich stürmisch in den Kampf und ließ „gerichtliche Verantwortungsschriften“ und „Appellationen an das Publikum“ erscheinen. Nicht Forberg, sondern Fichte rückte unversehens in den Fokus der Auseinandersetzung. Er wurde aus seinem Lehrverhältnis entlassen, und aufgehetzte Studenten warfen ihm abends die Fenster ein.

Der zuständige sachsen-weimarische Minister, Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, der Fichte als Person an sich sehr achtete, kommentierte spöttisch: „Eine unangenehme Art, von der Existenz der Außenwelt Kenntnis zu nehmen.“ Seine Worte bezogen sich auf die Philosophie Fichtes, seine „Wissenschaftslehre“, die das berühmte „Ding an sich“ der Kantischen Theorie seiner Objektivität entkleidet und zum Produkt der dialektischen Vernunft gemacht hatte.

Goethe vermochte in Fichte nur eine Neuausgabe des seinerzeitigen englischen Bischofs George Berkeley (1685–1753) zu sehen, der das Vorhandensein einer unabhängig vom individuellen Bewußtsein existierenden Außenwelt leugnete und die Gegenstände als bloße individuelle Vorstellungen auffaßte. Die Reduktion Fichtes auf Berkeley und andere „subjektive Idealisten“ und Sensualisten ging jedoch völlig an der wesentlichen Problematik vorbei.

Das Ich setzt sich sein Nicht-Ich

Entscheidend war, daß Fichte als erster ein einheitliches voluntaristisches System entwarf, das keines Anstoßes von außen bedurfte, weil das Prinzip seiner Bewegung in ihm selbst ruhte. Es handelte sich bei diesem Prinzip nicht um irgendeinen biologischen „Trieb“, sondern um jenen Widerspruch in jedem denkenden Selbstbewußtsein, daß sich das „Ich“ nur dann als Ich denken kann, wenn es gleichzeitig auch ein „Nicht-Ich“ denkt.

Fichte konstatierte, daß sich der allgemeine Widerspruch zwischen Ich und Nicht-Ich in jeder konkreten Situation des Ich wiederhole. Immer und überall könne es nur im Nicht-Ich seine Bestimmung finden, es sei also ins Nicht-Ich hinein entfremdet, und sein wesentliches Bestreben sei es, diese Entfremdung aufzuheben und sich mit seinen konkreten Bestimmungen zu vereinigen. Dadurch aber entstehe der Weltprozeß wie auch der Prozeß jedes Individuums.

Diese Dialektik, als deren Schöpfer also mit Fug Fichte gelten kann, ist ungeheuer folgenreich gewesen: Hegel faßte ein wenig später die Entfremdung des Ich ins Nicht-Ich als „Negation“ und das Bestreben des Ich, das Nicht-Ich einzuholen, als „Negation der Negation“, baute diese Begriffe zu einer kompletten Methode aus und faßte mit ihrer Hilfe das ganze Material der damaligen Wissenschaften zu seinem epochemachenden System zusammen. Marx bediente sich bei seinen ökonomischen Analysen ebenfalls der Dialektik und gelangte dadurch zu seiner revolutionären Theorie vom Proletariat als der leibhaftigen Negation der bürgerlichen Gesellschaft.

Ein prophetischer Philosoph der Tat

Aber nicht genug damit. Dadurch, daß Fichte nicht gewillt war, die Dialektik zu objektivieren, mußte er folgerichtig zu dem Schluß gelangen, daß die Empfindung der äußeren Gegenstände nichts anderes sei als der freie Wille des Ich, sich Gegenstände zu setzen, um sie später wieder „einzuholen“, also zu zerstören. Der Denker war in erster Linie Täter, mag sein Untäter. Er formte die Welt nach seinem Willen – und nach dem Willen Gottes, von dem das Ich gleichsam ein „Teilchen“ und ein „Fünklein“ war.

Fichte war der Prophet der Tat, das Ich hatte sich bei ihm unentwegt an sozialen und politischen Konstellationen abzuarbeiten. So war er also, wie wir heute sagen würden, ein ungeheuer „engagierter“ Denker, der sich ungeniert und mit der ganzen Kraft seiner schier dämonischen Rhetorik in die politischen Händel einmischte. Er war nach seiner Vertreibung aus Jena nach Berlin gegangen, und dort stieg er in kürzester Zeit zu einem der bekanntesten Publizisten des Reiches auf.

Deutschland sah sich um die Jahrhundertwende vom 18. zum 19. Jahrhundert den massiven Angriffen und Vereinnahmungen Napoleons ausgesetzt, und der Widerstand dagegen trug entscheidend zur Formierung des Landes als moderne Nation bei. Und Fichte war (mehr noch als Herder) von der Geschichte tatsächlich dazu ausersehen, diesen objektiven Prozeß klar und machtvoll ins öffentliche Bewußtsein zu heben. Seine „Reden an die deutsche Nation“ von 1808 waren ausdrücklich als Medizin gedacht, welche den Widerstand gegen die Fremdherrschaft und den Prozeß der Nationwerdung befördern sollte.

„Wo das Licht ist, ist das Vaterland“

Nichts Dümmeres gibt es, als Fichte als geborenen „Franzosenfresser“ und die „Reden“ als Ausdruck eines ignoranten Chauvinismus hinzustellen. In den ersten Jahren der Revolution von 1789 hatte Fichte Frankreich ja noch als Hort der Freiheit gefeiert, man denke an Schriften wie „Zurückforderung der Denkfreiheit von den Fürsten Europas“. „Ubi lux, ibi patria“, schrieb er da, „wo das Licht ist, ist das Vaterland“.

Erst unter dem Einfluß der Napoleonischen Kriege gab der Philosoph seine transrheinische Begeisterung auf. „Der Staat Napoleons“, hieß es nun in den „Reden“, „kann nur immer neuen Krieg, Zerstörung und Verwüstung erzeugen. Man kann damit zwar die Erde ausplündern und wüste machen und sie zu einem dumpfen Chaos zerreiben, nimmermehr aber sie zu einer Universalmonarchie ordnen.“

Zur selben Zeit, da Fichte vor größter Öffentlichkeit in Berlin seine Reden an die deutsche Nation hielt, trug er vor akademischem Publikum auch seine „Grundzüge des gegenwärtigen Zeitalters“ vor, will sagen: seine Geschichtsphilosophie, die natürlich ein überzeitliches, jeder politischen Aktualität enthobenes historisches Schema zu liefern begehrte. Dennoch bereitet es hohen Reiz, die „Reden“ sich in den „Grundzügen“ spiegeln zu lassen und umgekehrt.

Deutschland zum Licht heben

Fichte unterschied drei gesellschaftliche Grundstadien. Da ist erstens das „arkadische Zeitalter“, in dem primitive Zustände und allenfalls ein „Vernunftinstinkt“ herrschen, und zweitens das sogenannte „Zeitalter der vollendeten Sündhaftigkeit“, in dem das Gemeinwesen sich von sich selbst entfremdet hat und in unendlich viele divergierende Individuen auseinandergefallen ist. In dieser Sündhaftigkeit, daran läßt der Philosoph keinen Zweifel, leben wir jetzt.

Abgelöst aber wird diese Ära der Sündhaftigeit, drittens, vom „elysischen Zeitalter“, dem Zeitalter der „Vernunftkunst“. Dieses letzte Zeitalter, meint Fichte, wird sich erheben, wenn die sündhafte Willkür der Individuen ihren Höhepunkt erreicht hat und sie nur noch wie Atome konturlos durcheinanderschwirren. Angesichts der politischen Zustände im damaligen Deutschland mag der Geschichtsdenker ernsthaft überzeugt gewesen sein, daß das Zeitalter der Sündhaftigkeit nun also komplett sei und es „nur“ noch der Zusammenfassung aller individuellen Energien bedürfe, um Deutschland zu einem Land des Lichts und der Vernunft emporzuheben.

Wenn Fichte gut von den Deutschen sprach, dann sprach er immer in der Zukunft. In den „Reden“ betont er an vielen Stellen, daß eine Erhebung aus dem gegenwärtigen Zustande einzig unter der Bedingung denkbar sei, daß dem deutschen Volk eine neue Welt aufginge. Johann Gottlieb Fichte starb im Januar 1814, mitten im Siegeslärm der Befreiungskriege, am Lazarettfieber, das seine Frau, die in einem Hospital verwundete Landsturmleute pflegte, von daher mitgebracht hatte.

Ein tragisch-banaler, früher Tod. Aber er ersparte dem großen Philosophen immerhin so manche Enttäuschung, die die Nachkriegszeit mit ihren Demagogenverfolgungen und ihrer feigen Biedermeierei mit sich brachte. Sein Vermächtnis weht uns heute wundersam ungebrochen an.

13:04 Publié dans Histoire, Philosophie, Théorie politique | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : histoire, allemagne, philosophie |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

mardi, 15 mai 2012

Rapaille Reportage over Junge Freiheit

Rapaille Reportage over Junge Freiheit

http://podcast.radiorapaille.com/show/rapaille-reportages/item/721-rapaille-reportage-over-junge-freiheit

Geschreven door djhadjememaar

Zondag 9 oktober kan je de integrale lezing van Mina Buts horen die ze op 1 oktober gaf tijdens de bijeenkomst die door de Deltastichting en Radio Rapaille was georganiseerd in De Beest.

Zondag 9 oktober kan je de integrale lezing van Mina Buts horen die ze op 1 oktober gaf tijdens de bijeenkomst die door de Deltastichting en Radio Rapaille was georganiseerd in De Beest.

Mina sprak in het Nederlands over dit neo-conservatieve weekblad dat ondanks terreur, boycot en algemeen doodzwijgen al 25 jaar vanuit Berlijn haar eigen kijk op de (inter)nationale politiek en samenleving geeft.

Radio Rapaille biedt de nieuwsgierige luisteraar nu de gelegenheid om kennis te maken met een uniek mediaproject.

En als je jouw favoriete top 3 invult voor de Rapaille Top 100 maak je ook nog eens kans op één van de 3 jaarabonnementen op dit prima weekblad twv € 169,- !!!

Ga dus snel naar: http://top100.radiorapaille.com

00:05 Publié dans Actualité, Affaires européennes | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : junge freiheit, allemagne, presse, médias |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

lundi, 14 mai 2012

Nolte, Nexus und Nasenring

Nolte, Nexus und Nasenring

von Thor v. Waldstein

Ex: http://www.sezession.de/

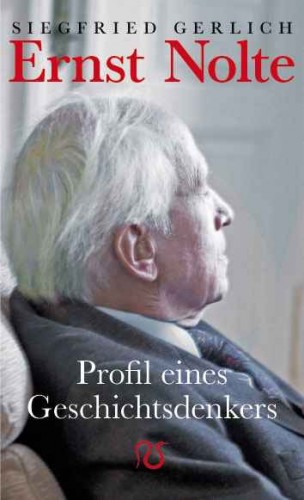

Über die Späten Reflexionen und die Italienischen Schriften Ernst Noltes ist es zwischen Siegfried Gerlich, Thorsten Hinz und Stefan Scheil zu einer Debatte gekommen (Sezession 45 und Sezession 46). Sie hat deutlich gemacht, wie ambivalent der Blick auf das Werk des im 90. Lebensjahr stehenden Geschichtsdenkers sein kann. Das spricht nicht zuletzt für den Autor Nolte, dessen Feder es offensichtlich gelungen ist, geistige Attraktion für ganz unterschiedliche historische Denkansätze zu entfalten.

Über die Späten Reflexionen und die Italienischen Schriften Ernst Noltes ist es zwischen Siegfried Gerlich, Thorsten Hinz und Stefan Scheil zu einer Debatte gekommen (Sezession 45 und Sezession 46). Sie hat deutlich gemacht, wie ambivalent der Blick auf das Werk des im 90. Lebensjahr stehenden Geschichtsdenkers sein kann. Das spricht nicht zuletzt für den Autor Nolte, dessen Feder es offensichtlich gelungen ist, geistige Attraktion für ganz unterschiedliche historische Denkansätze zu entfalten.

Dieser Befund deckt sich mit der Erfahrung des Verfassers dieser Zeilen, der fast jedes Werk Noltes gerade wegen dessen nüchtern-sezierendem Stil mit Gewinn gelesen hat, obwohl er die Anhänglichkeit Noltes zu dem »liberistischen Individuum« bzw. zu dem von diesem verkörperten »liberalen System« weder teilt noch versteht. Was aber bei jedem, der Nolte gerecht werden will, bleibt, ist der Respekt vor der souveränen Stoffbeherrschung, vor einer bewundernswürdigen Lebensleistung und vor der Unbeirrbarkeit, mit der Nolte die eigenen wissenschaftlichen Erkenntnisse und Thesen gegen das Meer der bundesdeutschen Anfeindungen spätestens seit dem Habermas-Skandal 1986 (dem sogenannten »Historikerstreit«) verteidigt hat.

Und damit sind wir schon bei dem, was bei dem »Sezession-Autorenstreit« vielleicht etwas zu kurz gekommen ist: nämlich der Erforschung der – eminent politischen – Frage, weswegen Ernst Nolte heute in der Bundesrepublik ein historiographischer Paria ist, der unter dem Verdacht des »Verfassungsfeindes« steht (Stefan Breuer) und dessen Werke wertfrei oder gar positiv zu zitieren der beste Weg sein dürfte, die eigene akademische Karriere gegen die Wand zu fahren. Hat diese Stigmatisierung allein mit mißliebigen wissenschaftlichen Erkenntnissen Noltes zu tun oder offenbart die Causa Nolte nicht vielmehr polit-psychologische Wirkmechanismen, die für das Verständnis des Staates, in dem wir leben, von nicht unmaßgeblicher Rolle sind? Hat Nolte mit seiner zentralen These von dem Kausalnexus zwischen Bolschewismus und Nationalsozialismus möglicherweise an Tabus der »Vergangenheitsbewältigung« gerüttelt, die in tieferen Bewußtseinsschichten der homines bundesrepublicanenses fest verankert sind?

Bekanntlich war es Armin Mohler, der sich 1968 – pikanterweise veranlaßt durch einen Auftrag der Bonner Ministerialbürokratie – erstmals gründlich mit dem Phänomen der Vergangenheitsbewältigung befaßte. 1989 widmete er sich demselben Thema erneut und legte im einzelnen dar, wie die Deutschen seit 1945 am Nasenring der Vergangenheitsbewältigung vorgeführt werden. Ausgangspunkt Mohlers war zunächst die Feststellung, daß es weder möglich noch wünschenswert sei, daß ein Volk seine Vergangenheit bewältige. Nicht nur jedem Individuum, sondern auch einem Volk sei ein Recht auf Vergessen zuzubilligen. Diejenigen, die gleichwohl die Maschinerie der unablässigen Vergangenheitsbewältigung in Gang gesetzt hätten, würden dies in der Absicht tun, sozialpsychologisch determinierte Komplexe heranzuzüchten, um diese anschließend in den Dienst bestimmter politischer Ziele zu stellen. Endstufe sei der entortete Deutsche, der angesichts der NS-Katastrophe nach und nach ein perverses Verhältnis zu den Traditionen seiner Vorfahren entwickle, und dessen Deutschsein man am Ende vor allem daran erkenne, daß er alles sein wolle: Europäer, Weltbürger, Pazifist usw. – nur kein Deutscher mehr. Damit erwies sich die Vergangenheitsbewältigung als konsequente Fortsetzung der nach 1945 von der US-amerikanischen Besatzungsmacht ins Werk gesetzten »Re-education«, also des »Versuchs, den deutschen Volkscharakter einschneidend zu ändern, auf daß die politische Rolle Deutschlands in Zukunft von außen kontrolliert werden könne« (Caspar von Schrenck-Notzing).

Man braucht keine besonders gute Beobachtungsgabe für die Feststellung, daß dieser Versuch einer »Charakterwäsche« der Deutschen heute als weitgehend gelungen angesehen werden kann. Der Prototyp des ferngesteuerten, von historischen Komplexen regelrecht aufgeblasenen Deutschen begegnet einem auf Schritt und Tritt. Es gibt keine Talk-Show, kein Lehrerzimmer, keine Redaktionsstube, keinen Seminarraum, wo man sich nicht laufend der zu Tode gerittenen Distanzierungsvokabel »Nazi« bedient, um die Kappung der historischen Entwicklungslinien Deutschlands als »demokratische Errungenschaft« zu feiern. Kurioserweise läßt sich der Bundesbürger durch dieses permanente »Strammstehen vor den politisierten, mythologisierten Begriffen« (Frank Lisson) nicht in seiner höchstpersönlichen Glückseligkeit stören, was Johannes Gross einmal zu der paradox-treffenden Bemerkung veranlaßte, »die Bundesrepublik Deutschland (sei) ein übelgelauntes Land, aber ihre Einwohner sind glücklich und zufrieden«.

Jenseits dieser privaten Partydauerstimmung, in der man die eigene Vita der Amüsementsteigerung widmet, weiß der Deutsche von heute aber sehr genau, wo und auf welche Schlüsselworte hin er auf Moll umzuschalten hat: beim Befassen mit dem Düsterdeutschland der Jahre vor Neunzehnhundert-Sie-wissen-schon. Gerät man auf diesem kontaminierten Gelände auch nur unter Verdacht, die geschichtspolitischen Dogmen nicht hinreichend verinnerlicht zu haben oder offenbart man gar Ermüdungserscheinungen bei dem Distanzierungsvolkssport Nummer eins, dem Einprügeln auf die herrlich toten »Nazis«, darf man sich nicht wundern, wenn man eines schönen Tages als »Rechtsextremist« o.ä. aufwacht. Diesem Umstand ist es zu verdanken, daß sich zwischenzeitlich die meisten NS-Forschungsfelder in politisch-psychologische »No-go-areas« verwandelt haben, in denen nicht Erkenntnisdrang, sondern penetranter Dogmatismus den (Buß-)Gang der Dinge bestimmt.

Jenseits dieser privaten Partydauerstimmung, in der man die eigene Vita der Amüsementsteigerung widmet, weiß der Deutsche von heute aber sehr genau, wo und auf welche Schlüsselworte hin er auf Moll umzuschalten hat: beim Befassen mit dem Düsterdeutschland der Jahre vor Neunzehnhundert-Sie-wissen-schon. Gerät man auf diesem kontaminierten Gelände auch nur unter Verdacht, die geschichtspolitischen Dogmen nicht hinreichend verinnerlicht zu haben oder offenbart man gar Ermüdungserscheinungen bei dem Distanzierungsvolkssport Nummer eins, dem Einprügeln auf die herrlich toten »Nazis«, darf man sich nicht wundern, wenn man eines schönen Tages als »Rechtsextremist« o.ä. aufwacht. Diesem Umstand ist es zu verdanken, daß sich zwischenzeitlich die meisten NS-Forschungsfelder in politisch-psychologische »No-go-areas« verwandelt haben, in denen nicht Erkenntnisdrang, sondern penetranter Dogmatismus den (Buß-)Gang der Dinge bestimmt.

Der Nationalsozialismus ist daher weiter der zentrale »Negativ-Maßstab der politischen Erziehung« (Martin Broszat) und darf im Sinne derer, die sich der politischen (Ver-)Bildung von bald drei Generationen in Deutschland gewidmet haben und weiter zu widmen sich anschicken, gerade nicht historisiert werden. Gefragt ist moralisch-verschwommene Befindlichkeit, nicht wissenschaftlich-präzise Analyse. Auf diesem Terrain herrscht ein zivilreligiös aufgeladener Machtanspruch, der hinter Kant und die Aufklärung zurückfällt und der in der Geschichte der europäischen Neuzeit ohne Beispiel ist. Auf diesem, von Psycho-Pathologien beherrschten Feld ist »souverän …, wer über die Einhaltung von Tabus und Ritualen verfügt« (Frank Lisson).

Es geht also um Macht und nicht um Wahrheit, um Deutungshoheit und nicht um historische Erkenntnis, um Kampagnenfähigkeit und nicht um seriöse wissenschaftliche Methode. Es geht darum, jeglichen jenseits des aufoktroyierten Neusprechs liegenden, originären geistigen Denkansatz zu dem historischen Phänomen des Nationalsozialismus sofort zu skandalisieren und damit seiner Wirkung zu berauben.

Der seit 1986ff. in der Öffentlichkeit der Bundesrepublik Deutschland geführte »Streit um Nolte« ist also in seinem Kern keine historische Fachdiskussion, er ist – neben vielen anderen Beispielen dieser Art – ein besonders sig¬nifikanter Ausdruck eines gesteuerten Debatten¬ablaufs in einem unfreien Land. Noltes Nexus-Theorie ist den Politgewinnlern der deutschen historischen Tragödie 1914ff. ein Dorn im Auge, weil sie durch ihren actio-reactio-Ansatz das NS-Singularitätsdogma und den darauf aufbauenden Machtanspruch der Vergangenheitsbewältigung gefährdet.

Daß Lenin und erst recht Stalin keine russischen Dalai Lamas waren, wissen zwar alle; die Bedrohung Europas durch den bolschewistischen Ideologiestaat aus dem Osten muß aber aktiv beschwiegen werden, um den dialektischen Prozeß, von dem die Geschichte des Zweiten Dreißigjährigen Krieges 1914–1945 wie kaum eine andere Epoche zuvor bestimmt wurde, zu entkoppeln. Das dient zwar nicht dem historischen Verständnis, befördert aber den Tunnelblick auf die deutschen Untaten, mit dem sich auch im 21. Jahrhundert gute Geschäfte und konkrete Politik machen läßt.

Diese selektive, dauerpräsente Vergangenheit darf nicht vergehen. Sie stellt ein wichtiges Instrument dar, auf das auch morgen nicht verzichtet werden kann, soll die Bundesrepublik weiter als ein politisch desorientierter Staat erhalten bleiben, dem die Pflege der deutschen Neurosen wichtiger ist als die Gestaltung der deutschen Zukunft. Deswegen kann es nicht verwundern, daß eben dieses sozialpsychologische Neurosenfeld groteskerweise an Umfang und an Ansteckungskraft in dem Maße zunimmt, wie sich der zeitliche Abstand zum 8. Mai vergrößert.

Die seit bald 70 Jahren währende Dauerbesiegung des Zombies aus Braunau hat freilich ihren Preis: Es ist ein – von dem unablässig rotierenden Freizeit-, Unterhaltungs- und Urlaubskarussell nur mühsam zu übertönendes – Klima der Zukunftslosigkeit in Deutschland entstanden, das durch nichts besser gekennzeichnet wird als durch die Kinderlosigkeit eines Landes, in dem die Attribute deutsch und alt immer häufiger zusammenfallen. Manches spricht dafür, daß die ethnische Abwärtsspirale, in der sich die Deutschen heute befinden, viel zu tun hat mit der mentalen Todessehnsucht, von deren süßlichem Verwesungsduft das unablässige Rattern der Vergangenheitsbewältigungsmaschinerie umschleiert wird.

Die Abwicklung der Deutschen (demographische Implosion und »Umvolkung«) ist dabei nur die letzte Konsequenz eines Geschichtsbildes, das den (Auto-)Genozid der Deutschen seit ca. 1970 als gerechte Strafe für das Geschehen vor 1945 auffaßt. Schließlich kann das abstrakt-moralische Gebot, von deutschem Boden dürfe nie wieder Krieg ausgehen, am besten dadurch erfüllt werden, daß die Deutschen von eben diesem Boden ihrer Väter und Vorväter verschwinden, und zwar endgültig. Bei der Vergangenheitsbewältigung geht es somit um alles andere als um historische Erkenntnis oder um wissenschaftliche Seriosität, es geht um Zukunftsverhinderung, »um die Vernichtung alles dessen, was deutsch ist – was deutsch fühlt, deutsch denkt, sich deutsch verhält und deutsch aussieht« (Armin Mohler).

Wer als junger Deutscher zu einem solch aberwitzigen »mourir pour Auschwitz« nicht bereit ist, wird gnadenlos mit der »Hitler-Scheiße« (Martin Walser) zugedeckt und läuft Gefahr, als »Heide der Gedenkreligion des Holokaust« (Peter Furth) über Nacht seine sozialen Beziehungen zu verlieren. Denn wer ein Tabu übertreten hat, wissen wir seit Freud, wird selbst tabu. Die dazu erforderliche braune Lava wurde und wird von den Niemöllers, Eschenburgs, Wehlers, Benz’, Knopps e tutti quanti seit Jahrzehnten am Blubbern gehalten. Ein Solitär wie Nolte, der – ganz ohne den Mundgeruch der Bewältigungstechnokraten – die historischen Abläufe 1917ff. nüchtern und mit luziden Zwischentönen analysiert, könnte bei diesem Simplifizierungsgeschäft nur stören.

Wer als junger Deutscher zu einem solch aberwitzigen »mourir pour Auschwitz« nicht bereit ist, wird gnadenlos mit der »Hitler-Scheiße« (Martin Walser) zugedeckt und läuft Gefahr, als »Heide der Gedenkreligion des Holokaust« (Peter Furth) über Nacht seine sozialen Beziehungen zu verlieren. Denn wer ein Tabu übertreten hat, wissen wir seit Freud, wird selbst tabu. Die dazu erforderliche braune Lava wurde und wird von den Niemöllers, Eschenburgs, Wehlers, Benz’, Knopps e tutti quanti seit Jahrzehnten am Blubbern gehalten. Ein Solitär wie Nolte, der – ganz ohne den Mundgeruch der Bewältigungstechnokraten – die historischen Abläufe 1917ff. nüchtern und mit luziden Zwischentönen analysiert, könnte bei diesem Simplifizierungsgeschäft nur stören.

Es spielt dann auch keine Rolle mehr, daß es gerade Nolte war, der, weil er Hitler verstanden und nicht zu »bewältigen« versucht hat, das geschichtsphilosophisch Einzigartige des NS-Judenmordes präzise herausgearbeitet hat (Der Europäische Bürgerkrieg, S. 514–517). Um die jüdischen Opfer des Nationalsozialismus – darunter eine große Zahl patriotischer Reichsdeutscher, für die das Deutschland des Jahres 2012 einen Alptraum dargestellt hätte – geht es den Matadoren der Vergangenheitsbewältigung ohnehin nicht. Ihr Andenken mißbrauchen sie genauso, wie sie jenes an die Männer schänden, die für das Land der Deutschen als Soldaten ihren Kopf hingehalten haben.

Das selektive Erinnern und das Nichtvergessenwollen erweist sich dabei als der sicherste Weg, eine Zukunft der Deutschen zu verhindern. Denn die Kraft zur geschichtlichen Existenz eines Volkes setzt stets voraus, daß es den Willen hat weiterzuleben. Und diesen Willen kann ein Volk nur dann behaupten, wenn man ihm ein Recht zubilligt, nicht nur mit anderen, sondern zuallererst mit sich selbst in Frieden zu leben. Das wiederum setzt voraus, daß Wunden verheilen und irgendwann ein mentaler Neuanfang stattfindet. Dieser ist indes nur denkbar, wenn zuvor der an allen Orten und zu allen Zeiten ausschlagende »Nazometer« (Harald Schmidt) endlich ausgeschaltet wird. Das Geheimnis der Versöhnung ist eben nicht die Erinnerung, schon gar nicht die sakralisierte und instrumentalisierte Erinnerung der heutigen Hüter unserer Vergangenheit, die sich anmaßen, noch die deutschen Jahrgänge 2000ff. nach dem Pawlowschen Taktstock der Vergangenheitsbewältigung tanzen zu lassen.

Deren Zweck erschöpft sich heute nicht nur in »der totalen Disqualifikation eines Volkes« (Hellmut Diwald); Ziel dieser 27. Januar-Kultur (ausgerechnet Mozarts Geburtstag!) ist es, das seelische Immunsystem der Deutschen – auch an den 364 übrigen Tagen des Jahres – so weit(er) zu zerstören, daß die Deutschen schließlich die ethnische Verabschiedung von ihrem eigenen Grund und Boden, die Zweite Vertreibung der Deutschen, die in vielen Stadtteilen deutscher Großstädte schon weit fortgeschritten ist, mindestens gleichgültig hinnehmen, wenn nicht gar als »Urteil« der Geschichte begrüßen.

Ein altes Kulturvolk Europas, dem die Menschheit in der Musik fast alles, in der neuzeitlichen Philosophie das wesentliche und in den Natur- und Geisteswissenschaften sehr viel zu verdanken hat, wäre dann verschwunden. Ob diese »Endlösung der deutschen Frage« (Robert Hepp) eintritt oder nicht, liegt nicht zuletzt an den Deutschen selbst, denen es freisteht, morgen den Nasenring abzulegen und das zu tun, was für jeden Kirgisen, jeden Katalanen und jeden Kurden selbstverständlich ist: nämlich als Volk frei über die eigene Zukunft zu bestimmen.

Literatur:

Siegfried Gerlich: Ernst Nolte. Profil eines Geschichtsdenker, Schnellroda 2010

Ernst Nolte: Späte Reflexionen, Wien 2011

Ernst Nolte: Italienische Schriften, Berlin 2011

00:10 Publié dans Histoire, Hommages | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : allemagne, ernst nolte, livres, hommage, histoire |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

mercredi, 09 mai 2012

Keine US-Atombomben im Juli/August 1945!

Keine US-Atombomben im Juli/August 1945!

220 Seiten - Leinen - 110 Abbildungen

Kurztext:

Dieses Buch enthüllt ein seit Kriegsende von den Siegermächten streng gehütetes Geheimnis des deutschen Untergangs 1945.Die sofortige Geheimhaltung der bei Kriegsende in Mitteldeutschland erbeuteten nuklearen Hochtechnologie wurde mit der lapidaren Behauptung »die US-Army hat nichts gefunden« verbunden. Die Untersuchung des historischen Sachverhaltes bestätigt jetzt eine von den USA inszenierte und seit 1945 gepflegte Falschdarstellung der Atombomben-Entwicklungsgeschichte. Die Reichsregierung hatte sich felsenfest auf den von der Wissenschaft zugesicherten Besitz der Atombombe verlassen. So wurde die Entwicklung der ›Siegeswaffe‹ gegenüber der eigenen Bevölkerung bis zum Kriegsende streng geheimgehalten. Als der Zusammenbruch kam, bevor die Atombomben eingesetzt wurden, brauchte die Geheimhaltung der deutschen Atombombe von den USA lediglich fortgeführt zu werden.

Das Buch räumt mit bisherigen Ansichten zur Frühzeit der Atombomben auf und zeigt, wie das offizielle Amerika die Zeitgeschichte in einem wichtigen Bereich fälschte.

Klappentext:

00:05 Publié dans Histoire, Livre | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : histoire, livre, allemagne, etats-unis, deuxième guerre mondiale, seconde guerre mondiale, armes nucléaires, bombe atomique, armes atomiques |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

dimanche, 06 mai 2012

Presseschau Mai 2012

Presseschau

Mai 2012

AUßENPOLITISCHES

Golfstaaten wollen Anti-Assad-Armee finanzieren

http://www.jungefreiheit.de/Single-News-Display-mit-Komm.154+M5d05949d752.0.html

Mediales Trauerspiel im Syrienkonflikt

http://www.jungefreiheit.de/Single-News-Display-mit-Komm.154+M51294a98b05.0.html

Talkshow im russischen TV

Julian Assange scheitert an Hisbollah-Chef

http://www.spiegel.de/netzwelt/netzpolitik/0,1518,828035,00.html

Israel Loves Iran - Facebook-Kampagne gegen den Krieg

http://digiweb.excite.de/israel-loves-iran-facebook-kampagne-gegen-den-krieg-N54023.html

Saudi-Arabien

Wegen „unerlaubter Musik“

Religionspolizei stoppt „unislamische“ Schlümpfe

http://www.focus.de/politik/ausland/wegen-unerlaubter-musik-religionspolizei-stoppt-unislamische-schluempfe_aid_745602.html

Schweizer Gold auf Druck der USA abverkauft

http://www.unzensuriert.at/content/008080-Schweizer-Gold-auf-Druck-der-USA-abverkauft

Stadt Wien nimmt Karl Lueger den “Ring” weg

http://www.unzensuriert.at/content/008073-Stadt-Wien-nimmt-Karl-Lueger-den-Ring-weg

(Der deutsche Sonderweg 1)

SPD und Grüne empört über Le-Pen-Erfolg

http://www.jungefreiheit.de/Single-News-Display-mit-Komm.154+M556ec8f1da9.0.html

(Der deutsche Sonderweg 2)

Union kritisiert Anti-Ungarn-Kampagne der SPD

http://www.jungefreiheit.de/Single-News-Display-mit-Komm.154+M55d3c57201f.0.html

Liquid Constitution

Crowdgesourct: Island schreibt sich eine neue Verfassung. Der Versuch, mehr Demokratie im digitalen Zeitalter zu ermöglichen, nähert sich dem Abschluss

http://www.heise.de/tp/artikel/36/36785/1.html

(Faustrecht statt mehr Demokratie und Diskussion…)

Landbesetzer legen Feuer in größtem Stadtwald Mexikos

http://www.derwesten.de/agenturmeldungen/landbesetzer-legen-feuer-in-groesstem-stadtwald-mexikos-id6593661.html

INNENPOLITISCHES / GESELLSCHAFT / VERGANGENHEITSPOLITIK

(Zum Streit um die Bundeswehr und den Ochsenknecht-Sohn)

Willkommen im Krieg

http://www.jungefreiheit.de/Single-News-Display-mit-Komm.154+M5c73b3ee971.0.html

Die Demokratie schafft sich ab

http://www.jungefreiheit.de/Single-News-Display-mit-Komm.154+M50cba460856.0.html

Volker Beck fühlt sich von Lokalpolitikerin bedroht

http://www.jungefreiheit.de/Single-News-Display-mit-Komm.154+M5a28c2a6a3b.0.html

Grüne attackieren CDU wegen Steinbach-Kandidatur

http://www.jungefreiheit.de/Single-News-Display-mit-Komm.154+M56caff3deaa.0.html

(Schäubles Märchenstunde)

Euro-Krise: Schäuble schließt weitere Zahlungen aus

http://www.zeit.de/news/2012-04/09/eu-euro-krise-schaeuble-schliesst-weitere-zahlungen-aus-09145602

Euro-Krise: Schäuble gibt Entwarnung – Experten bangen weiter

http://www.gevestor.de/details/euro-krise-schaeuble-gibt-entwarnung-experten-bangen-weiter-547966.html

Gaertner´s Blog

Die Weltwirtschaft vom Pazifik aus

http://blog.markusgaertner.com/

Initiative "Holt unser Gold heim!"

http://www.gold-action.de/initiative.html

Herzlich willkommen bei der Wissensmanufaktur

Der Fokus unserer Wissensmanufaktur liegt neben den permanenten Untersuchungen der

aktuellen Wirtschaftslage auch in der Hinterfragung der gesamten wirtschaftlichen Ordnung.

http://www.wissensmanufaktur.net/

Knobloch fordert Unterstützung für Israel im Iran-Konflikt

http://www.jungefreiheit.de/Single-News-Display-mit-Komm.154+M59f4bef018b.0.html

Piraten erinnern Deutsche an historische Schuld

http://www.jungefreiheit.de/Single-News-Display-mit-Komm.154+M5a83c5b66b6.0.html

(Zum deutschen Geschichtsunterricht)

Kümmern Sie sich!

http://www.jungefreiheit.de/Single-News-Display-mit-Komm.154+M526f70a0f13.0.html

Kampagne von „Besseres Hannover“: Deutsche helfen Deutschen!

http://www.besseres-hannover.info/wordpress/?m=20120412

LINKE / KAMPF GEGEN RECHTS / ANTIFASCHISMUS

(...ein Fundstück zum ARD-Interview mit den Eltern des "NSU-Terroristen" Uwe Böhnhardt)

Zitat:

OB Schröter (SPD), der kürzlich einen Preis für Zivilcourage gegen Rechtsradikalismus erhielt, glaubt, dass das Problem in den 90er Jahren nicht ernst genug genommen wurde. "Es ist tragisch für uns, dass die Neonazis, die die schlimmsten Verbrechen seit 1945 in Deutschland verübt haben, aus Jena stammen."

http://www.fnp.de/fnp/nachrichten/politik/man-kann-das-nicht-verzeihen_rmn01.c.9773816.de.html

(Somit steht die NSU nun faktisch direkt hinter dem Holocaust.)

(dazu…)

Beim Häuten der Zwickauer Zwiebel

http://www.jungefreiheit.de/Single-News-Display-mit-Komm.154+M5006de328b5.0.html

(Antifanten erhalten nun bereits Denkmals- bzw. Straßennamen-Ehren…)

CDU-Politiker gegen Straßenumbenennung nach getötetem Punker

http://www.jungefreiheit.de/Single-News-Display-mit-Komm.154+M5af01737411.0.html

(Das ist wenigstens konsequent gedacht bzw. das weit verbreitete Denken auf den Punkt formuliert. Jede Betonung von Unterschied oder eigenem in Ablehnung von anderem ist "Nazi", ist altes Denken, das endlich überwunden werden muss. Alle sind gleichwertig, gleichberechtigt, sozial zu managen und sollen sich akzeptieren. Außer eben die Leute mit dem alten Denken.)

Julia Schramm ueber Nazis

http://juliaschramm.de/2012/04/20/nazis-und-poststrukturalismus/

(eine Antwort)

Die Piraten und das rechte Gespenst

http://www.sezession.de/31962/die-piraten-und-das-rechte-gespenst.html

(„Antifa“-Artikel gegen „Umwelt und Aktiv“ im „Spiegel“)

Neonazi-Strategie

Braune Bio-Kameradschaft

Von Christian Pfaffinger

http://www.spiegel.de/politik/deutschland/0,1518,814893,00.html

Dies ist der verantwortliche Schreiber. Ein unbedarft wirkender 24-jähriger Nachwuchsbubi...

http://www.chp-online.de/?page_id=2

http://www.bjv.de/home/fachgruppen/jungejournalisten.xhtml

Eine Antwort…

Fragwürdiger Journalismus

http://www.umweltundaktiv.de/allgemein/fragwurdiger-journalismus/

„Das ist Ihr Jargon!“ – Aus einem Forschungsseminar über Rechtsextremismus

http://www.sezession.de/31743/das-ist-ihr-jargon-aus-einem-forschungsseminar-uber-rechtsextremismus.html#more-31743

Medienbericht: Gysi soll Kontakt zur Stasi gehabt haben

http://www.jungefreiheit.de/Single-News-Display-mit-Komm.154+M5fb7a044791.0.html

Linksextremismus

Joschka Fischer sagt nach Drohungen Auftritt ab

http://www.welt.de/politik/deutschland/article106139122/Joschka-Fischer-sagt-nach-Drohungen-Auftritt-ab.html

„Lübeck ist bunt“: Protest gegen Neonazis

http://www.focus.de/panorama/vermischtes/luebeck-ist-bunt-protest-gegen-neonazis_aid_731231.html

Demonstrationen gegen Neonazis und Islam-Feinde

http://www.fehmarn24.de/nachrichten/deutschland/menschen-demonstrieren-gegen-neonazis-zr-2261094.html

Proteste gegen Neonazis und Islam-Feinde

http://diepresse.com/home/politik/aussenpolitik/745322/Proteste-gegen-Neonazis-und-IslamFeinde?from=rss

FPÖ

Anonymous-Aprilscherz: Journalisten verlieren letzte Hemmungen

http://www.unzensuriert.at/content/007858-Anonymous-Aprilscherz-Journalisten-verlieren-letzte-Hemmungen

Deutsche Bank kündigt „Deutschen Konservativen“

http://www.jungefreiheit.de/Single-News-Display-mit-Komm.154+M57806bd7827.0.html

Tyrannei im Netz

http://www.jungefreiheit.de/Single-News-Display-mit-Komm.154+M57ffba553de.0.html

(Tenor: Links ist besser als Rechts)

Der Bundesparteitag möge beschließen, folgenden Programmpunkt in das Wahlprogramm der Piratenpartei Deutschlands aufzunehmen:

Ablehnung des Extremismusbegriffs

https://lqfb.piratenpartei.de/pp/initiative/show/2681.html

Berliner Fraktionschef der Piraten fordert Gesinnungs-Tüv

http://www.jungefreiheit.de/Single-News-Display-mit-Komm.154+M5a9343fbb61.0.html

Berliner Piratenchef kritisiert Stellungnahme gegen Rechtsextremismus

http://www.jungefreiheit.de/Single-News-Display-mit-Komm.154+M5b68b3b35dd.0.html

Wider den Abgrenzungswahn

http://www.jungefreiheit.de/Single-News-Display-mit-Komm.154+M526ccafc9aa.0.html

(Zu Piraten und Nazis)

Es gibt ein Stöckchen, …

http://www.sezession.de/31950/es-gibt-ein-stockchen.html#more-31950

Wie rechts darf ein Pirat sein?

Die Debatte weitet sich aus

http://www.heise.de/tp/blogs/8/151844

Probleme von Jungparteien

Kinderkrankheiten

Die Grünen hatten Anfang der 1980er ihr braunes Waterloo. Inklusive analogem Shitstorm. Der Unterschied zu den Piraten: Sie hatten noch mit Veteranen der NS-Zeit zu kämpfen.

http://www.taz.de/Probleme-von-Jungparteien/!92073/

Piratenpartei verweigert JF Akkreditierung

http://www.jungefreiheit.de/Single-News-Display-mit-Komm.154+M52901ed587a.0.html

Lageignoranz und Politikunfähigkeit: Nachlese zur „Causa Weidner“

http://www.sezession.de/32072/lageignoranz-und-politikunfahigkeit-nachlese-zur-causa-weidner.html#more-32072

Nach Ablehnung des NPD-Kandidaten: Gera nimmt Risiko einer Wahlanfechtung in Kauf

http://www.tlz.de/startseite/detail/-/specific/Nach-Ablehnung-des-NPD-Kandidaten-Gera-nimmt-Risiko-einer-Wahlanfechtung-in-Kau-875573301

Zu NPD-Ausschluss in Gera: Juristische Verrenkungen

Volkhard Paczulla zum Umgang der Demokratie mit ihren erklärten Gegnern

http://www.tlz.de/startseite/detail/-/specific/Zu-NPD-Ausschluss-in-Gera-Juristische-Verrenkungen-405926160

Wetterau

Rechtsextreme machen sich rar

Eine Gruppe Rechtsextremen hat den Einwohnern von Echzell lange zu schaffen gemacht. Inzwischen aber befinden sich die Neonazis in der Defensive. Einer sitzt in U-Haft und dem Rest stellen sich verschiedene Bürgerinitiativen entgegen.

http://www.fr-online.de/rhein-main/wetterau-rechtsextreme-machen-sich-rar,1472796,14701548.html

(auch die orthodoxe Position ist immer noch nicht ganz ausgestorben...)

Die ich rief die Geister...........

Gedanken zum rechten Terror Autor: Siegfried Kunze, Dreieich

http://www.die-linke-kreis-offenbach.de/diskussionsbeitraege/die-ich-rief-die-geister-........../

Geschichtsdidaktik

http://www.jungefreiheit.de/Single-News-Display-mit-Komm.154+M52f89c4bfbf.0.html

Aussteigerprogramm des Verfassungsschutzes stößt auf geringe Resonanz

http://www.jungefreiheit.de/Single-News-Display-mit-Komm.154+M5b76751aa19.0.html

Juso zündet eigenes Vereinslokal an

http://www.jungefreiheit.de/Single-News-Display-mit-Komm.154+M5902f97de3e.0.html

Ausländer täuscht rechtsextremen Überfall vor

http://www.jungefreiheit.de/Single-News-Display-mit-Komm.154+M5fafcca6950.0.html

Hamburg: Polizeigewerkschaft protestiert gegen Punk-Konzert

http://www.jungefreiheit.de/Single-News-Display-mit-Komm.154+M5181c24729a.0.html

Frankfurt

Polizeigewerkschaft verurteilt linksextreme Ausschreitungen

http://www.jungefreiheit.de/Single-News-Display-mit-Komm.154+M508912976b6.0.html

Brutaler Straßenterror der Linksfaschisten

Rasche Konsequenzen notwendig

http://www.freie-waehler-frankfurt.de/artikel/index.php?id=278

Werbung für Gewaltdemo auch im Ortsbeirat

Grüne Ortsvorsteherin unterstützt Linksfaschisten

http://www.freie-waehler-frankfurt.de/artikel/index.php?id=285

Linksextremisten kosten Berlin Millionen

http://www.jungefreiheit.de/Single-News-Display-mit-Komm.154+M5ecc1c8bdec.0.html

Wie Linksextreme auf Demos die Polizei austricksen

http://www.unzensuriert.at/content/007861-Wie-Linksextreme-auf-Demos-die-Polizei-austricksen

EINWANDERUNG / MULTIKULTURELLE GESELLSCHAFT

Unterschwellige Botschaften

http://www.jungefreiheit.de/Single-News-Display-mit-Komm.154+M5239db4b759.0.html

Lies! Den Koran!

http://www.sezession.de/31808/lies-den-koran.html#more-31808

Evangelikale und Piusbrüder empört über Wort zum Sonntag

http://www.jungefreiheit.de/Single-News-Display-mit-Komm.154+M59b6d1f83fd.0.html

Der unglaubliche Mut der Neudeutschen

http://www.sezession.de/31715/der-unglaubliche-mut-der-neudeutschen.html#more-31715

(Wenn mutige, zivilcouragierte Journalisten verstummen hat das manchmal nicht nur mit dem ideologischen Brett vor dem Kopf, sondern auch ganz anderen Sachen zu tun.)

Islamisten bedrohen deutsche Journalisten

http://www.welt.de/politik/deutschland/article106173295/Islamisten-bedrohen-deutsche-Journalisten.html

Friedrich will verstärkte Grenzkontrollen

(und „Pro Asyl“ stänkert gleich dagegen…)

http://www.derwesten.de/nachrichten/friedrich-will-verstaerkte-grenzkontrollen-id6526409.html

Interview mit Udo Ulfkotte

http://www.citizentimes.eu/2012/03/28/die-mehrheit-der-muslime-leidet-an-islamophobie/

Kommunisten und Muslime demonstrieren gemeinsam in Dänemark gegen Islamkritik

http://europenews.dk/de/node/53374

http://deutschelobby.com/2012/03/31/antifa-krawalle-rund-um-edl-demo-in-aarhus/

(Der „Spiegel“ jubiliert dazu)

Anti-Islam-Demo in Dänemark

Großkundgebung schrumpft zu Zwergenaufstand

http://www.spiegel.de/politik/ausland/0,1518,825078,00.html

(eine weitere Organisation der Einwanderungslobby)

Amnesty prangert angebliche Diskriminierung von Moslems an

http://www.jungefreiheit.de/Single-News-Display-mit-Komm.154+M5ea35da4add.0.html

(Kolat läuft endgültig Amok)

Türkische Gemeinde unterstellt Sarrazin nationalsozialistische Gesinnung

http://www.jungefreiheit.de/Single-News-Display-mit-Komm.154+M5f9cedacc72.0.html

In der Wagenburg der Islamkritiker

http://www.jungefreiheit.de/Single-News-Display-mit-Komm.154+M54e34d2833d.0.html

Fundamentalisten in der Fußgängerzone

http://www.jungefreiheit.de/Single-News-Display-mit-Komm.154+M51c6d342510.0.html

Hessen wird zum Zentrum radikaler Salafisten

In Hessen tummelt sich eine stetig wachsende Szene radikaler Islamisten. Prominenter Vertreter ist Mohamed Mahmoud, der ganz offen gegen Deutschland hetzt. Den Behörden sind wohl die Hände gebunden. Von Florian Flade

http://www.welt.de/politik/deutschland/article106225871/Hessen-wird-zum-Zentrum-radikaler-Salafisten.html

Solingen

Salafisten verletzen Polizisten mit Steinen

http://www.op-online.de/nachrichten/deutschland/salafisten-bewerfen-polizeibeamte-solingen-steinen-2299307.html

Videobotschaft eines Migranten

An die CDU

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BvitSAGG9Fs

(Auweia)

Schweden: Rassismus-Skandal um menschliche Torte

http://www.jungefreiheit.de/Single-News-Display-mit-Komm.154+M51b426559fe.0.html

Harzer Straße

Ein Roma-Dorf zieht nach Berlin

http://www.bz-berlin.de/bezirk/neukoelln/ein-roma-dorf-zieht-nach-berlin-article1426839.html

Erklärt Perreira

http://www.jungefreiheit.de/Single-News-Display-mit-Komm.154+M5fa31868e30.0.html

(dazu wüsste man gerne mehr an Information…)

Trio sticht auf 22-Jährigen ein

http://www.op-online.de/nachrichten/frankfurt-rhein-main/trio-messerangriff-frankfurt-lebensgefahr-polizei-2261530.html

Doppelmord - Mutmaßlicher Todesschütze schweigt vor Gericht

http://www.stern.de/panorama/doppelmord-mutmasslicher-todesschuetze-schweigt-vor-gericht-1808466.html

KULTUR / UMWELT / ZEITGEIST / SONSTIGES

Zwang zur Innovation verschandelt unsere Städte

Historische Orte ziehen uns an, weil sie ein harmonisches Ganzes bilden. Heute wollen Architekten vor allem "innovativ" sein. So entstehen modische Hingucker – aber keine schönen Städte. Von Wolfgang Sonne

http://www.welt.de/debatte/kommentare/article106165023/Zwang-zur-Innovation-verschandelt-unsere-Staedte.html

Wenn Stadtplaner historische Viertel niederreißen

Ein Stadtmassaker nach dem anderen: Im Ruhrgebiet werden ganze Stadtviertel zertrümmert, von stolzen Gründerzeithäusern bleibt nur Schutt übrig. Vor allem in Duisburg versagen Stadtplaner.

http://www.welt.de/kultur/article106206991/Wenn-Stadtplaner-historische-Viertel-niederreissen.html

Der "Retter von Kreuzberg" wird 90

http://www.welt.de/kultur/article106179673/Der-Retter-von-Kreuzberg-wird-90.html

Wärmedämmung

Die Burka fürs Haus

Wohnen, Dämmen, Lügen: Am deutschen Dämmstoffwesen soll das Weltklima genesen. Was der neue Fassadenstreit über unser Land verrät und warum Vollwärmeschutz das Gegenteil von Fortschritt ist.

http://www.faz.net/aktuell/feuilleton/waermedaemmung-die-burka-fuers-haus-11071251.html

Architektur im Klimawandel

http://www.daserste.de/information/ratgeber-service/bauen-wohnen/sendung/wdr/2012/22042012-architektur-im-klimawandel-100.html

Oldenburg

Denkmal-Posse um Graf und Pferd

http://www.ndr.de/fernsehen/sendungen/menschen_und_schlagzeilen/videos/menschenundschlagzeilen1295.html

Probestehen für Oldenburgs Grafen

http://www.ndr.de/regional/niedersachsen/oldenburg/reiterdenkmal109.html

Wagners Schatten in Leipzig

http://www.sezession.de/31758/wagners-schatten-in-leipzig.html

Kunstmuseum und Flechtheim-Erben

Einigung über Seehaus-Gemälde

http://www.rundschau-online.de/html/artikel/1334354037604.shtml

Schätze des Berliner Schlosses doch nicht verloren

Historische Leuchter, Teppiche, Skulpturen: Ein Bildband dokumentiert die Geschichte der einstigen Innenausstattung des Berliner Schlosses. Davon ist mehr erhalten, als man bisher glaubte.

http://www.welt.de/kultur/history/article106238880/Schaetze-des-Berliner-Schlosses-doch-nicht-verloren.html

Kiezdeutsch und kein Ende

http://www.jungefreiheit.de/Single-News-Display-mit-Komm.154+M59ff708c57b.0.html

Proteste nach harter Mathe-Klausur

Durchfallquote 94 Prozent

http://www.spiegel.de/unispiegel/studium/0,1518,826946,00.html

Die modernen Barbaren

Christliche Feiertage im Fadenkreuz der Spaßgesellschaft

http://www.freie-waehler-frankfurt.de/artikel/index.php?id=281

(Zur Gedankenmanipulation)

Wie die Psychoanalyse der Demokratie die Politik ausgetrieben hat

http://antjeschrupp.com/2012/04/16/wie-die-psychoanalyse-der-demokratie-die-politik-ausgetrieben-hat/

(Sander und Maschke)

Deutsche Meisterdenker

http://www.sezession.de/31712/deutsche-meisterdenker.html#more-31712

Ein Essayist des Eigenen

http://www.jungefreiheit.de/Single-News-Display-mit-Komm.154+M57abedda27b.0.html

Von Hitler zum Kommunismus

Richard Scheringers Weg durch das 20. Jahrhundert

http://www.heise.de/tp/artikel/36/36535/1.html

Umerziehung von oben – Stefan Scheils „Transatlantische Wechselwirkungen“

http://www.sezession.de/31936/umerziehung-von-oben-stefan-scheils-transatlantische-wechselwirkungen.html#more-31936

Günter Grass hält Deutschland den Spiegel vor

http://www.unzensuriert.at/content/007901-Guenter-Grass-haelt-Deutschland-den-Spiegel-vor

Günter Grass und die schuldstolze Agitprop

http://www.sezession.de/31702/grass-und-der-schuldstolze-agitprop.html#more-31702

Die Causa Grass: Eine aufgeblasene Debatte, die viel über uns verrät

http://www.blauenarzisse.de/index.php/anstoss/3237-die-causa-grass-eine-aufgeblasene-debatte-die-viel-ueber-uns-verraet

Grass: Was gesagt werden muss (Im Gespräch mit Jürgen Elsässer)

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2m5S0j7mx3I

Was gesagt werden muss

Von Manfred Kleine-Hartlage

http://www.freie-waehler-frankfurt.de/artikel/index.php?id=287

Grass empört Israels Innenminister mit DDR-Vergleich

http://www.jungefreiheit.de/Single-News-Display-mit-Komm.154+M57188be95bd.0.html

Einreiseverbot für David Irving bleibt bestehen

http://www.jungefreiheit.de/Single-News-Display-mit-Komm.154+M53d7639cbe8.0.html

Ist Intelligenz erblich? – Eine Klarstellung

http://www.sezession.de/31828/ist-intelligenz-erblich-eine-klarstellung.html#more-31828

(Zu Broder…)

Macht und Meinungsfreiheit

http://www.sezession.de/31765/macht-und-meinungsfreiheit.html

Der Feind vor meiner Tür

Schuld und Sühne im Paradies: Der Arte-Mehrteiler "Gelobtes Land" rührt am Fundament des Nahost-Konflikts

http://www.welt.de/print/die_welt/kultur/article106205787/Der-Feind-vor-meiner-Tuer.html

Wo Macher, Senderchefs, Kritiker irren

Furchtlose Krieger

http://www.tagesspiegel.de/medien/wo-macher-senderchefs-kritiker-irren-furchtlose-krieger/6539166.html

(Zur Debatte „Internet und geistiges Eigentum“)

Diesen Kuss der ganzen Welt

http://www.perlentaucher.de/blog/258_diesen_kuss_der_ganzen_welt

(Zur Debatte „Internet und geistiges Eigentum“)

Lieber Sven Regener!

http://www.dirkvongehlen.de/index.php/netz/lieber-sven-regener/

Demokratisierung und Publizieren

http://juliaschramm.de/2012/04/07/demokratisierung-und-publizieren/

(Vortrag zum revolutionären Umbruch durch das Internet)

006 Keynote Blau

http://www.youtube.com/watch?feature=player_embedded&v=LSeIoxz9Me0

(Zum Urheberrechts-Streit)

Ich heb dann mal ur

http://www.spreeblick.com/2012/04/14/ich-heb-dann-mal-ur/

Das ewige Klassentreffen

Das Internet macht unsere Freundschaften oberflächlicher – doch das ist gar nicht so schlimm, wie alle denken.

http://allfacebook.de/allgemeines/das-ewige-klassentreffen

"Lohnarbeit ist Sklaverei"

http://www.taz.de/1/archiv/digitaz/artikel/?ressort=tz&dig=2012%2F04%2F14%2Fa0204&cHash=21ab59c470

Gott, Gebet und Politik

Die Pfingstbewegung in Guatemala verändert sich

http://www.dradio.de/dkultur/sendungen/weltzeit/1186383/

Kirchenkritische Kunstaktion

Heiliges Höschen, erhöre uns!

http://www.spiegel.de/kultur/gesellschaft/0,1518,827597,00.html

Ramsauer gegen die „Kampf-Radler“

Verkehrsminister will Fahrrad-Rowdys nicht hinnehmen

http://www.focus.de/politik/deutschland/ramsauer-gegen-die-kampf-radler-verkehrsminister-will-fahrrad-rowdys-nicht-hinnehmen_aid_734987.html

Herzzerbrechende News

Märchen aus der Realität: Über die Reportagen von Marc Fischer, der heute vor einem Jahr starb.

http://www.welt.de/print/die_welt/kultur/article106144440/Herzzerbrechende-News.html

Alt-Hippie trifft auf Piraten

Langhans' neue Liebe

http://www.sueddeutsche.de/muenchen/alt-hippie-trifft-auf-piraten-langhans-neue-liebe-1.1338938

Studieren in Indien

Versteck die Cola, die Affen kommen

http://www.spiegel.de/unispiegel/studium/0,1518,828859,00.html

Naidoo als Soundtrack der “Reichsbewegung”?

http://www.publikative.org/2012/04/26/xavier-naidoo-als-soundtrack-der-reichsbewegung/

CD Andi Weiss: Heimat