En cette période de montée des nationalismes – voire des « ethnicismes » – en Europe comme ailleurs, les ethnologues, qui redoutaient naguère d’être considérés comme des suppôts du colonialisme, éprouvent souvent aujourd’hui, à l’inverse, l’angoisse d’être, malgré eux, de par la nature et l’objet même de leur discipline, des apôtres du tribalisme, des défenseurs inconscients d’un romantisme contre-révolutionnaire exaltant les valeurs particularistes contre l’universalisme des Droits de l’homme et du citoyen.

En cette période de montée des nationalismes – voire des « ethnicismes » – en Europe comme ailleurs, les ethnologues, qui redoutaient naguère d’être considérés comme des suppôts du colonialisme, éprouvent souvent aujourd’hui, à l’inverse, l’angoisse d’être, malgré eux, de par la nature et l’objet même de leur discipline, des apôtres du tribalisme, des défenseurs inconscients d’un romantisme contre-révolutionnaire exaltant les valeurs particularistes contre l’universalisme des Droits de l’homme et du citoyen.

En penseur, qu’on a pris récemment, un peu rapidement, pour l’emblème même de ce tribalisme (1), semble, au contraire, être un de ceux dont l’œuvre peut aider à lever cette angoisse, en ouvrant le chemin à un rationalisme rénové, apte à comprendre le lien qui, à l’est de l’Europe en particulier, mais à l’ouest parfois aussi, unit nationalisme et recherche de la démocratie. Ce penseur, c’est Johann Gottfried Herder.

Herder et l’Aufklärung

Herder, honni par Joseph de Maistre (2) et vénéré, au contraire, par Edgar Quinet, Thomas Mazaryk et d’autres grandes figures de la démocratie européenne et américaine, est un héritier éclatant de la pensée des Lumières, de l’Aufklärung du XVIIe siècle, même s’il la critique parfois. En fait cette critique est une critique « de gauche », dirait-on aujourd’hui, et non « de droite », comme celle de Maistre ou Bonald. Comme l’a écrit Ernst Cassirer, en Herder, la philosophie des Lumières se dépasse elle-même et atteint son « sommet spirituel » (Cassirer 1970 : 237).

Effectivement, il n’est guère de thèmes fondamentaux de sa pensée, du relativisme à la philosophie de l’histoire, du naturalisme au déisme, etc., dont on ne retrouve les antécédents, au XVIIe et au XVIIIe siècle, chez les meilleurs représentants de la philosophie des Lumières, qu’il s’agisse de Saint-Evremont ou de Voltaire, de l’abbé Du Bos ou de David Hume, d’Adam Fergusson ou de D. Diderot. Y compris le thème du Nationalgeist. Y compris celui du relativisme (je préférerais dire « perspectivisme »).

Ce n’est pas Herder, mais Hume qui, dans ses Essais de morale, écrit : « Vous n’avez point eu assez d’égard aux mœurs et aux usages de différents siècles. Voudriez-vous juger un Grec ou un Romain d’après les lois d’Angleterre ? Écoutez-les se défendre par leurs propres maximes, vous vous prononcerez ensuite. Il n’y a pas de mœurs, quelque innocentes et quelque raisonnables qu’elles soient, que l’on ne puisse rendre odieuses ou ridicules lorsqu’on les jugera d’après un modèle inconnu aux auteurs » (Hume 1947 : 192). Il est vrai que ce souci d’équité ethnologique ne signifie pas, pour Hume, qu’il ne faut pas souhaiter l’effacement de différences nationales. Mais, dans l’idéal, Herder le souhaite pareillement. S’il lui arrive de faire l’éloge des « préjugés », c’est-à-dire des présupposés culturels attachés à telle ou telle nation ou civilisation, c’est uniquement dans la mesure où cela peut donner aux pensées la force et l’effectivité qui risquent de leur manquer lorsqu’elles s’efforcent d’atteindre l’humain et l’universel seulement par un refus abstrait du particulier. L’idée est d’ailleurs dans Rousseau. Elle n’empêche pas de poser que « l’amour de l’humanité est véritablement plus que l’amour de la patrie et de la cité » (Herder 1964 : 327).

Quant au Nationalgeist, Montesquieu le nomme « esprit du peuple », « caractère de la nation ». Même chez Voltaire on trouve les notions de « génie d’une langue » et de « génie national » (3). Il est vrai que, chez eux, ce ne sont sans doute pas des principes originels, mais qu’ils dépendent d’autres facteurs historiques. Cependant, il n’en est pas autrement chez Herder. En fait, Herder voit dans le peuple ou la nation un effet statistique, produit par un ensemble de particularités individuelles, modelées par un même milieu, un même climat, des circonstances historiques communes, des emprunts similaires à d’autres peuples et la tradition qui en résulte. La nation n’apparaît comme une entité substantielle qu’à un regard éloigné, qu’à une vue d’ensemble. Herder est, au fond, sur le plan de la théorie sociale, comme il l’est d’ailleurs sur le plan éthique, un individualiste (4). La primauté de la société ne signifie rien d’autre, chez Herder, que l’idée que l’histoire ne peut être que celle des peuples, celle du peuple, et non celle des rois et de leurs ministres ; elle ne peut être que celle de la civilisation. Et, de ce point de vue, Herder est un voltairien qui ne s’ignore pas…

Une anthropologie de la diversité

Il y a cependant deux sources majeures de la pensée de Herder, sans lesquelles il n’est pas facile de la comprendre, et toutes deux ont eu une énorme influence sur l’Aufklärung allemande : ce sont l’œuvre de Leibniz et celle de Rousseau.

Sans Rousseau, il n’est pas possible de comprendre la logique qui unit le rationalisme de Herder à son anthropologie de la diversité. C’est Rousseau qui, le premier sans doute, nous a fait comprendre que la raison et la liberté étaient une seule et même chose. Herder lui emboîte le pas. Précurseur de Bolk et de Géza Roheim (5), théoricien de l’immaturité essentielle de l’homme ou, tout au moins, de son indétermination, qui fait sa liberté, mais qui est également la raison même de sa raison, Herder montre clairement que la diversité des cultures est la conséquence directe de l’existence de cette raison, qui n’est pas une faculté distincte, mais, en quelque sorte, l’être même de l’homme. La différence entre l’homme et l’animal n’est pas une différence de facultés, mais, comme il le dit dans le Traité sur l’origine de la langue, une différence totale de direction et de développement de toutes ses facultés (1977 : 71).

Mais si la raison n’est pas une faculté séparée et isolée, elle est présente dès l’enfance, dès l’origine, dans le moindre effort de langage. La raison herderienne est une raison du sens, non une raison du calcul, une raison vichienne, non une raison cartésienne, mais c’est une raison tout de même. Et fort importante, puisque la seconde ne va pas sans la première ; et puis parce que la raison cartésienne ne fonde ni morale ni droit.

Herder, comme Vico, a pressenti à quoi conduisait un certain cartésianisme. S’il n’existe pas un trésor de sens, où chacun puisse puiser ce qui le fait cet être unique et, en même temps, de part en part dicible (donc, par là même, en qui subsiste toujours du non-dit), qu’est un être humain, alors on parvient rapidement à l’humpty-dumptisme, qui est la pire des tyrannies. Chacun va décréter le sens des mots dans la mesure du pouvoir dont il dispose. Il n’y aura plus aucun contrat possible, aucune entente, sinon par le pouvoir despotique de quelque Léviathan. La politique de Descartes, ce ne pourrait être, effectivement, dans ces conditions, que le monstre froid que décrit Hobbes et où c’est, effectivement, le souverain qui décide du sens des mots. C’est bien ce monstre que les grands hommes d’Etat du XVIIe siècle cherchent à réaliser, à commencer par le cardinal de Richelieu. Cela aboutit finalement à la fameuse « langue de bois », même si cela ne commence que par d’apparemment innocentes académies.

Un eudémonisme relativiste

L’idée de l’essentielle variabilité humaine conduit à une éthique d’une grande souplesse, puisque, pour Herder, la raison est d’abord inhérente à la sensibilité ; et donnant pour fin à l’homme le bonheur, elle en modèle la figure idéale en fonction de la diversité des besoins et des sentiments. L’infinie variété des circonstances produit aussi une infinie variété des aspirations et le bonheur, qui est le but de notre existence, ne peut être atteint partout de la même façon : « Même l’image de la félicité change avec chaque état de choses et chaque climat – car qu’est-elle, sinon la somme de satisfactions de désirs, réalisations de buts et de doux triomphes des besoins qui tous se modèlent d’après le pays, l’époque, le lieu ? » C’est que « la nature humaine… n’est pas un vaisseau capable de contenir une félicité absolue…, elle n’en absorbe pas moins partout autant de félicité qu’elle le peut : argile ductile, prenant selon les situations, les besoins et les oppressions les plus diverses, des formes également diverses » (Herder 1964 : 183).

Il y a donc chez Herder une sorte d’eudémonisme relativiste que Kant ne pourra supporter, et qui signifie que, pour Herder, l’individu n’est pas fait pour l’État ni, d’ailleurs, pour l’espèce. Les générations antérieures ne sont pas faites pour les dernières venues, ni les dernières venues pour les futures. Ainsi le sens de la vie humaine n’est pas dans le progrès de l’espèce, mais dans la possibilité pour chacun, à toute époque, de réaliser son humanité, quelle que soit la société dans laquelle il vit et la culture propre à cette société. Il y a là un humanisme qui s’oppose à celui de Kant, pour qui nous devons accepter que les générations antérieures sacrifient leur bonheur aux générations ultérieures ; celles-ci, seules, pourront en jouir. Herder, au contraire, pense que chaque époque a son bonheur propre ; chaque époque, chaque peuple et même chaque individu. Car chaque période, mais aussi chaque individu forme, pour ainsi dire, un tout qui a sa fin en soi. C’est pourquoi Herder en vient même à récuser tout finalisme dans l’explication historique, de peur d’avoir à subordonner le destin des individus au cours de l’histoire globale. Dieu n’agit dans l’histoire que par des lois générales naturelles, non téléologiques, et par l’effet de notre propre liberté.

Des monades dans l’histoire

Mais Herder est aussi un leibnizien. C’est dire que son individualisme n’est pas atomistique, mais monadique ; ce qui signifie qu’il a un caractère dynamique et que l’individu y intègre l’universel qui est dans la totalité organique de l’histoire.

Ce que dit Ernst Cassirer de la conception leibnizienne de l’individuel éclaire la conception herderienne :

« Chaque substance individuelle, au sein du système leibnizien, est, non pas seulement une partie, un fragment, un morceau de l’univers, mais cet univers même, vu d’un certain lieu et dans une perspective particulière… toute substance, tout en conservant sa propre permanence et en développant ses représentations selon sa propre loi, se rapporte cependant, dans le cours même de cette création individuelle, à la totalité des autres et s’accorde en quelque façon avec elle » (Cassirer 1970 : 65).

Pourtant, il y a, dans Une autre philosophie de l’histoire (Auch eine Philosophie der Geschichte), un passage où Herder semble nous dénier la possibilité d’être, comme il dit, « la quintessence de tous les temps et de tous les peuples ». En fait, il admet que nous avons en nous toutes les dispositions, toutes les aptitudes, toutes les potentialités qui se sont manifestées comme réalités achevées dans les diverses civilisations du passé. De ce point de vue, il y a, en chacun de nous une égale quantité de forces et un même dosage de ces forces. Mais un leibnizien ne sépare pas l’individualité des circonstances qui modèlent son développement. L’individualité est dans la continuité d’un développement qui intègre les circonstances qui permettent à cette individualité de se manifester.

Or chaque civilisation, chaque culture réalise un des possibles de l’humain et en occulte d’autres (6). Au cours de l’histoire, il se peut donc que l’ensemble des virtualités de la nature humaine se trouvent réalisées, mais tour à tour, non simultanément. Chaque moment, cependant, fruit d’une égale nécessité, possède un égal mérite. Cela ne contredit pas l’idée d’un progrès d’ensemble, mais va contre un évolutionnisme pour lequel l’humain ne se réalise pleinement qu’au terme de l’histoire (ou de la préhistoire, pour parler le langage d’un certain marxisme).

Herder utilise, au fond, le principe auquel Haeckel donnera son nom en le formulant en termes biologiques, mais qui est aussi la maxime d’une vieille métaphore : la phylogénèse se retrouve dans l’ontogénèse ; et on comprend à partir de là comment il peut concilier progression – Fortgang – et égalité de valeur. L’enfance vaut par elle-même, elle a ses propres valeurs, son propre bonheur ; l’adolescence, de même. Mais c’est quand même l’adulte qui est l’homme achevé, l’homme dans sa maturité.

Mais, mieux encore, l’égalité herderienne des cultures et des époques trouve sa justification dans ce que Michel Serres (1968 : 265) appelle, chez Leibniz, « la notion d’altérité qualitative dans une stabilité des degrés » : « En passant du plaisir de la musique à celui de la peinture, dit Leibniz, le degré des plaisirs pourra être le même, sans que le dernier ait pour lui d’autre avantage que celui de la nouveauté… Ainsi le meilleur peut être changé en un autre qui ne lui cède point, et qui ne le surpasse point. » Il n’en reste pas moins qu’« il y aura toujours entre eux un ordre, et le meilleur ordre qui soit possible ». S’il est vrai qu’« une partie de la suite peut être égalée par une autre partie de la même suite », néanmoins « prenant toute la suite des choses, le meilleur n’a point d’égal (7) ». Mais on peut aller beaucoup plus loin, et dire que, de même qu’il y a équipotence entre, non seulement la suite des nombres pairs et la suite des carrés, mais la suite des carrés, par exemple, et la suite des entiers, le meilleur a même puissance dans une partie de la suite et dans l’ordre du tout.

Chez Herder, il se peut donc que chaque phase ou chaque époque soit la meilleure, que chaque culture soit la meilleure, mais qu’il y ait, en plus, un meilleur dans l’ordre de succession, c’est-à-dire un ordre progressif, où le meilleur n’est atteint que dans le progrès même, en tant que succession bien ordonnée. Au-delà, on peut dire aussi que l’universel – un universel dynamique, celui de l’histoire comme totalité non fermée – est présent dans la singularité des cultures et des individus.

Inversement, d’ailleurs, l’universel n’existe qu’incarné dans des singularités historiques. C’est le cas, par exemple, du christianisme, religion universelle par excellence, mais qui n’existe que sous telle ou telle forme, particulière à telle ou telle époque, à telle ou telle civilisation : « Il était radicalement impossible que cette odeur délicate pût exister, être appliquée, sans se mêler à des matières plus terrestres dont elle a besoin pour lui servir en quelque sorte de véhicule. Tels furent naturellement la tournure d’esprit de chaque peuple, ses mœurs et ses lois, ses penchants et ses facultés… plus le parfum est subtil, plus il tendrait par lui-même à se volatiliser, plus aussi il faut le mélanger pour l’utiliser » (Herder 1964 : 209-211).

Un patriotisme cosmopolite

La présence de l’universel dans le singulier et le fait que le singulier et l’universel ne puissent être séparés rend compte de la possibilité, pour Herder, d’être à la fois cosmopolite et patriote, comme le furent ultérieurement quelques-uns de ses grands disciples. Le cosmopolite selon Herder n’est donc pas l’adepte d’un cosmopolitisme abstrait qui s’étonne de ne pas retrouver en chacun l’homme universel qu’il prétend lui-même incarner. Le cosmopolitisme de Herder est un cosmopolitisme de la compréhension entre les peuples et entre les cultures, c’est un cosmopolitisme « dialogique ».

De 1765 (année où il prononce à Riga son discours, Avons-nous encore un public et une patrie commune comme les Anciens ?) jusqu’à la fin de sa vie, Herder gardera cette position humaniste, hostile au particularisme aveugle, favorable seulement à un patriotisme qui ouvre sur l’universel. Herder récuse le patriotisme exclusif des anciens, qui regarde l’étranger comme un ennemi. Il veut, quant à lui, voir et aimer tous les peuples en l’humanité, dont il dit qu’elle est notre seule vraie patrie.

Il est vrai que cette vertu d’humanité, il pensera finalement que le peuple allemand sera, dans la période de l’histoire qui vient, celui qui l’incarnera probablement le mieux et que son aptitude à la philosophie en fait un excellent porteur d’universalité ; ce qui n’est pas si mal vu, si l’on pense à l’éclatante lignée de penseurs que l’Allemagne produira, de Kant à Marx et au-delà. De Lessing, Herder et Kant, avec Schiller et Goethe, Herzen (1843) dira que leur but commun fut de « développer les caractères nationaux pour leur donner un sens universel ».

On pourrait en dire autant de la génération suivante, celle des romantiques, pour laquelle on affiche quelquefois en France un bien curieux mépris. De Tieck, Novalis, Achim von Arnim, Clemens Brentano, Lucien Lévy-Bruhl (1890 : 336) écrivait : « Ce n’est pas un sentiment de patriotisme qui poussait ces écrivains à exhumer les trésors de l’Allemagne du Moyen Age. Le contraire est plutôt vrai : ce fut l’Allemagne du Moyen Age, retrouvée et passionnément aimée, qui réveilla en eux le patriotisme. Encore n’arrivèrent-ils à l’Allemagne que par un long et capricieux circuit, en faisant le tour du monde. Ils se seraient reproché, sans nul doute, de s’enfermer dans l’étude des antiquités germaniques. Elle eût offert à elle seule un champ de travail assez vaste ; mais les Romantiques ne s’y attardèrent point. Ils le parcoururent un peu, comme on l’a dit, en chevaliers errants. Leur humeur vagabonde, d’accord avec leur cosmopolitisme, les emportait bientôt ailleurs. »

Herder est préromantique dans la mesure où il y a, dans le romantisme, une sorte d’universalisme du populaire, où l’universalisme se concilie fort bien avec le pluralisme. En fait, ce qu’on retrouve dans le pluralisme littéraire de Goethe, de Herder et des romantiques d’Allemagne et d’ailleurs, c’est la volonté de réhabiliter le sensible et de fonder une esthétique, au sens large et au sens étroit. Peut-être même faut-il dire que le romantisme est là d’abord, et, de ce point de vue, il est déjà chez le Kant de la Critique du jugement, voire même chez Leibniz.

Mais cette réhabilitation du sensible est, en même temps et du même coup, une réhabilitation du sens, c’est-à-dire de la langue. Tout part de là chez Herder et tout y aboutit ; chez Herder comme aussi, par exemple chez Schlegel. Il s’agit d’édifier une science où l’on puisse vivre. Mais cette science est déjà présente dans la culture populaire, dans les cultures populaires. Cette réhabilitation du sensible s’intéresse donc au « populaire » en général, à l’« ethnique » si l’on veut, mais aussi à autrui, à l’autre en tant que tel, car autrui, c’est d’abord du sensible et il n’y a pas de monde sensible sans autrui. Autrui n’est accessible que comme sensible, et ce sensible ne peut être réduit. Feuerbach, de ce point de vue, est dans la postérité du romantisme, et le romantisme est peut-être ce qui a rendu possible l’ethnologie.

Herder « gauchiste »

Herder, cependant, reste un Aufklärer, mais, nous l’avons dit, un Aufklärer de gauche ; de gauche, et même d’extrême gauche. Et c’est la raison pour laquelle certains croient voir en lui un adversaire des Lumières, voire même un contre-révolutionnaire, ce qui constitue un assez joli contresens.

Il y a une autre raison de cette méprise, chez les auteurs français tout au moins : c’est que Herder se réclame du christianisme. C’est même un homme d’Église, un pasteur ; à l’époque (1784) où il écrit les Ideen (Herder 1962), il est évêque de Weimar. Or les Français pensent généralement que les Lumières sont nécessairement antichrétiennes, ce qui est une grave erreur historique, surtout en ce qui concerne l’Allemagne. Herder, en fait, est dans la tradition allemande de la Guerre des paysans, au temps de la Réforme, guerre dont l’idéologie fut celle d’un protestantisme populaire, millénariste et extrêmement avancé sur le plan social. C’est de Herder que Goethe tire l’idée de Goetz von Berlichingen. Mais on retrouve la même attitude chez le Herder tardif des Ideen, lorsqu’il fait l’éloge des hussites, de anabaptistes, des mennonites, etc., après avoir fait celui des bogomiles et des cathares pour les mêmes raisons. On le voit bien, dans ce chapitre des Ideen, où il se situe (Herder 1962 : 483-489). Cette position « gauchiste » de Herder aboutit effectivement à une critique de la philosophie des Lumières sur un certain nombre de points : théorie mystificatrice du contrat social, goût du despotisme « éclairé », tolérance envers l’esclavagisme et l’exploitation coloniale, avec sa brutalité destructrice, racisme, etc. Il s’agit bien d’une critique « de gauche », dont nous avons déjà vu une manifestation dans le refus de soumettre les individus aux « fins de l’histoire ».

En ce qui concerne la doctrine du contrat social, il ne faut pas oublier qu’elle a pris diverses formes et que chez certains de ses plus illustres défenseurs, elle aboutit à une légitimation de l’absolutisme. C’est le cas non seulement de la doctrine de Hobbes, mais de celles de Grotius et de Pufendorf. On oublie généralement le côté par où la théorie du contrat prétend engendrer la cité en engendrant le gouvernement de la cité. Hormis Rousseau, c’est le cas de nombre de ses adeptes. Et, dans ces conditions, ils admettront souvent que le gouvernement de la cité, quelles que soient sa nature et son origine de fait (y compris la conquête), existe par contrat tacite, ce qui n’est en fait, la plupart du temps, qu’une légitimation a posteriori de la force. C’est ce côté de la doctrine du contrat qu’attaque Herder, le côté par où, par une série de confusions, entre gouvernement et État, puis entre État et société, elle risque d’aboutir à l’absolutisme.

Herder est, avant tout, un adversaire du « despotisme éclairé », à la manière de Frédéric II et de quelques autres. Son soutien à ce que nous appellerions peut-être aujourd’hui des « ethnies » a principalement ce fondement. A tort ou à raison, il pense que la diversité ethnique, comme la multiplicité des corps intermédiaires (communautés diverses, villes-cités, etc.) est un puissant contrepoids à la force niveleuse du despotisme.

L’envers de cette haine du despotisme sous toutes ses formes, y compris le prétendu despotisme éclairé, c’est l’esprit démocratique. En dénonçant le nationalisme de Herder, on oublie que son nationalisme est lié à cet esprit démocratique. Les sujets d’un monarque n’ont pas de patrie. Le despotisme a aussi pour effet de freiner le développement des sciences et des arts. La culture, qui est créativité et non réception passive d’une tradition, est démocratique et nationale, tout à la fois et indissolublement.

Un nationalisme anarchiste

A vrai dire, Herder est non seulement antiabsolutiste, mais antiétatiste, contre l’État, anarchiste en ce sens-là. Contrairement à beaucoup de penseurs des Lumières, il soutient que l’État est, en lui-même, plutôt contraire au bonheur de l’individu que l’agent principal de ce bonheur. C’est un point important parce qu’il est à rattaché à cette méprise qui fait dire à Herder, par des citations isolées de leur contexte, qu’il est contre le mélange des nations et des cultures. Il n’est pas contre le mélange (8), il est contre l’État conquérant et impérialiste, qui groupe sous sa domination une foule de peuples divers dont il étouffe la diversité. C’est ce mélange-là que Herder repousse.

Herder est pour les peuples parce qu’il est pour le peuple, et il est pour le peuple parce qu’il est contre l’État, contre toute forme étatique, contre l’absurdité de la monarchie héréditaire (et la tradition, pour lui, sur le plan politique en tout cas, ne légitime rien du tout), contre la tyrannie des aristocraties, contre le Léviathan démocratique, dans la mesure où la démocratie reste un État, dans la mesure où elle est toujours cratie, même si elle est démo. Herder est aussi contre les classes sociales, qui vont contre la nature parce qu’elles ne sont établies que par la tradition, encore une fois – ce qui montre que Herder n’a rien d’un traditionaliste !

Pour Herder, tous les gouvernements éduquent les hommes pour les laisser dans l’état de minorité, dans une détresse infantile qui permet de mieux les dominer. Et, de ce point de vue, Herder retourne l’Aufklärung kantienne contre elle-même. Car c’est à Kant qu’il faut attribuer le principe cité par Herder dans les Ideen : « L’homme est un animal qui a besoin d’un maître et attend de ce maître ou d’un groupe de maîtres le bonheur de sa destination finale. » C’est un résumé de la position kantienne telle qu’elle est exprimée dans l’Idée d’une histoire universelle du point de vue cosmopolitique (Kant 1947 : 67 et sq.). Herder réplique : « L’homme qui a besoin d’un maître est une bête ; dès qu’il devient homme, il n’a plus besoin d’un maître à proprement parler… La notion d’être humain n’inclut pas celle d’un despote qui lui soit nécessaire et qui serait lui aussi un homme » (Herder 1962 : 157). Kant le prendra assez mal, mais c’est bien lui qui, dans sa philosophie de l’histoire prend position contre l’autonomie, et c’est Herder qui la défend.

L’antiétatisme de Herder est à relier à son antiartificialisme, à son antimécanicisme, et à cet organicisme dont on ne voit pas que, loin de subordonner l’individu aux finalités du tout, comme une pièce de la machine au fonctionnement de la mécanique entière, lui confère, au contraire, l’activité d’un organe sans lequel le tout ne pourrait s’animer. Il y a du Herder chez Stein, le ministre libéral de Frédéric-Guillaume IV, lorsqu’il soutient que l’Etat doit être non une machine, mais un organisme. Cette idée, précisément, est au fondement du libéralisme de Stein. Elle signifie que les sujets ne doivent pas être des instruments passifs aux mains de l’État, mais des organes actifs, capables d’initiatives.

L’antimilitarisme de Herder, sa polémique contre le principe de l’équilibre européen, invoqué par les princes pour mener leurs sujets au combat, sont à rattacher au même état d’esprit. La guerre est un instrument du totalitarisme de l’Etat monarchique, où personne « n’a plus le droit de savoir… ce que c’est que la dignité personnelle et la libre disposition de soi » (ibid. : 277), où le grain de sable qu’est l’individu ne pèse rien dans la machine (ibid. : 279).

Anticolonialisme

Mais Herder va plus loin dans le refus de certaines conséquences de la philosophie des Lumières, philosophie qui prône les vertus du commerce et de l’économie marchande. Dans une des pages les plus saisissantes de Une autre philosophie de l’histoire, il dénonce, avec une ironie voltairienne, les dévastations que fait subir à l’humanité la prédominance de cette économie marchande. C’est là une des clés de la pensée de Herder, qui a fort bien vu le lien étroit qu’il y a entre la colonisation « extérieure » et la colonisation « intérieure ».

Encore une fois, le point de vue de Herder est celui de la révolution paysanne. Herder est issu d’une famille de paysans pauvres et il a vécu à Riga, qui fut touchée par la révolte des anabaptistes au XVIe siècle. On peut peut-être rendre compte de son attitude à partir de là.

Il écrit donc : « Où ne parviennent pas, et où ne parviendront pas à s’établir des colonies européennes ! Partout les sauvages, plus ils prennent goût à notre eau-de-vie et à notre opulence, deviennent mûrs pour nos efforts de conversion ! Se rapprochent partout, surtout à l’aide de l’eau-de-vie et de l’opulence, de notre civilisation – seront bientôt, avec l’aide de Dieu, tous des hommes comme nous ! Des hommes bons, forts, heureux.

« Commerce et papauté, combien avez-vous déjà contribué à cette grande entreprise ! » Plus loin, il poursuit : « Si cela marche dans les autres continents, pourquoi pas en Europe ? C’est une honte pour l’Angleterre que l’Irlande soit si longtemps restée sauvage et barbare : elle est policée et heureuse. ».

Herder fait ensuite allusion au sort de l’Écosse. Mais il n’y en a pas que pour l’Angleterre ; la France n’est pas oubliée : « Quel royaume en notre siècle n’est devenu grand et heureux par la culture ! Il n’y en avait qu’un qui s’étalait au beau milieu, à la honte de l’humanité, sans académies ni sociétés d’agriculture, portant des moustaches et nourrissant par suite des régicides. Et vois tout ce que la France généreuse, à elle seule, a déjà fait de la Corse sauvage ! Ce fut l’œuvre de trois… moustaches : en faire des hommes comme nous ! des hommes bons, forts, heureux ! »

« L’unique ressort de nos États : la crainte et l’argent ; sans avoir aucunement besoin de la religion (ce ressort enfantin !), de l’honneur et de la liberté d’âme et de la félicité humaine. Comme nous savons bien saisir par surprise, comme un second Protée, le dieu unique de tous les dieux : Mammon ! et le métamorphoser ! et obtenir de lui par force tout ce que nous voulons ! Suprême et bienheureuse politique ! » (Herder 1964 : 271-273).

Plus loin encore, il récidivera, mettant cette fois en cause ce qu’il appelle le « système du commerce », et qui embrasse, semble-t-il, à la fois l’idéologie sous-jacente à la science économique et le capitalisme commercial, industriel et agraire : « Notre système commercial ! Peut-on rien imaginer qui surpasse le raffinement de cette science qui embrasse tout ? … En Europe, l’esclavage est aboli parce qu’on a calculé combien ces esclaves coûteraient davantage et rapporteraient moins que des hommes libres ; il n’y a qu’une chose que nous nous soyons permise : utiliser comme esclaves trois continents, en trafiquer, les exiler dans les mines d’argent et les sucreries – mais ce ne sont pas des Européens, pas des chrétiens, et en retour nous avons de l’argent et des pierres précieuses, des épices, du sucre, et… des maladies intimes ! Cela à cause du commerce, et pour une aide fraternelle réciproque et la communauté des nations ! « Système du commerce. » Ce qu’il y a de grand et d’unique dans cette organisation est manifeste : trois continents dévastés et policés par nous, et nous, par eux, dépeuplés, émasculés, plongés dans l’opulence, l’exploitation honteuse de l’humanité et la mort : voilà qui est s’enrichir et trouver son bonheur dans le commerce » (ibid. : 279-281).

On a rarement dénoncé avec autant de véhémence les ravages qui ont rendu possible l’édification de notre « économie-monde ». Herder a fort bien vu que l’entreprise, malgré « l’humanisme » de ses hérauts et thuriféraires, prenait volontiers appui sur un racisme ordinaire ou extraordinaire.

Antiracisme

Herder a fort bien vu aussi ce que la notion même de race, appliquée au genre humain, comporte de racisme implicite, dans la mesure où elle suppose, en fait, un polygénisme. Ceux qui, comme Buffon ou Kant se veulent monogénistes, mais parlent néanmoins de races humaines, sont donc, au moins, inconséquents. Herder est, lui, résolument monogéniste, contrairement à Voltaire, par exemple, qui pensait que « les Blancs et les Nègres, et les Rouges, et les Lapons et les Samoyèdes et les Albinos ne viennent certainement pas du même sol. La différence entre toutes ces espèces est aussi marquée qu’entre les chevaux et les chameaux »… Le monogénisme chrétien est donc à rejeter : « Il n’y a… qu’un brahmane mal instruit et entêté qui puisse prétendre que tous les hommes descendent de l’Indien Damo et de sa femme (9). »

Herder croit à la profonde unité de l’espèce humaine parce qu’il croit à la profonde unité des traditions. L’apparente diversité de ce qu’on appelle les races humaines n’est qu’un effet de la diversité des climats qui ne peut, tout au plus, produire que des variétés, mais qui ne pourrait, en aucun cas, engendrer des espèces. Cette diversité n’est donc pas un fait d’histoire naturelle, mais plutôt, pourrait-on dire, de géographie historique ou d’histoire géographique ; histoire qui témoigne, en tout cas, de la souplesse d’organisation de l’espèce humaine, c’est-à-dire de sa raison. Chez Herder, l’universalité de la raison prend appui non seulement sur la diversité des cultures, mais même sur la diversité d’apparence physique, de race, si l’on veut.

Selon lui, on perd le fil de l’histoire quand on a une prédilection pour une race quelconque et qu’on méprise tout ce qui n’est pas elle. L’historien de l’humanité doit être impartial et sans passion, comme le naturaliste, qui donne une valeur égale à la rose et au chardon, au ver de terre et à l’éléphant. La nature fait lever tous les genres possibles selon le lieu, le temps, la force. Conformément à l’inspiration leibnizienne de la pensée de Herder, « les nations se modifient selon le lieu, le temps et leur caractère interne », mais « chacune porte en elle l’harmonie de sa perfection, non comparable à d’autres » (Herder 1962 : 275). On retrouve ici ce que nous avons développé plus haut.

Herder est donc opposé également au racisme d’un Buffon, chez qui le racisme ou, comme dit Todorov, le « racialisme », entraîne la justification de l’esclavage et, bien entendu et a fortiori, de la colonisation et de la conquête (10). Mais il est probable qu’il ne pouvait non plus approuver Kant, pour qui, certes, même chez les Lapons, les Groenlandais, les Samoyèdes, même les « indigènes des mers du Sud » dont il est question dans les Fondements de la métaphysique des mœurs (1957 : 141) ont droit à notre respect, mais qui n’en sont pas moins à considérer comme moralement condamnables : en premier lieu parce qu’ils n’ont pas su constituer d’État. Or l’État est la condition pour que nous ayons quelque chance d’atteindre à la moralité. En second lieu, et surtout, parce qu’ils ne s’appliquent pas à développer leurs aptitudes par le travail, bref, parce qu’ils n’ont pas notre culture. Plaçant le droit, le droit « rationnel » moderne au-dessus du bonheur et, avec le droit, le travail, l’activité productive qui éveille en l’homme l’idée de la supériorité de la raison sur les sens, Kant aboutit en fait à un naïf européocentrisme, peu en accord avec la philosophie de Herder.

Un nouveau Vico

En Europe même, la prétention à se faire l’éducateur du genre humain risque d’aboutir à une dictature platonicienne des « spécialistes de l’universel ». L’anthropologie herderienne nous propose une conception de la culture qui relativise par avance l’opposition : culture (au singulier) / cultures (au pluriel) ou, plus clairement, l’opposition pensée / culture (au sens de l’anthropologie). Que les cultures, au pluriel, ne contiennent aucune pensée active, aucune créativité, n’est vrai que dans la mesure où « les cultures » ont été écrasées, tronçonnées, émiettées, ôtées à leurs courants d’échange « naturels », mais cela se révèle faux partout où on les laisse s’épanouir normalement.

Herder est un nouveau Vico, qui a compris qu’une éducation purement cartésienne, une éducation de la « table rase », laisse l’homme désemparé, privé de tout repère moral et politique, arraché aux dimensions sociales de son être. L’éducation de la pure pensée doit se compléter d’une éducation des sens et des sentiments, d’une éducation « humaniste » qui fasse place aux certitudes morales, c’est-à-dire au plus probable. Les arts du langage y doivent tenir leur rang, trop souvent méconnu : l’art du discours et des lettres, l’art de la traduction également, nécessaire à la connaissance morale d’autrui, et sans lequel on conçoit mal que puisse se constituer une raison « dialogique ».

Cette raison a besoin aussi de connaissances ethnologiques et historiques, elle a besoin de ce décentrement de la pensée qu’elles procurent, et sans lequel il n’y a point de reconnaissance d’autrui. L’histoire anthropologique, à la manière de Vico ou de Herder réunit ces deux types de connaissances. Elle préfigure l’histoire telle qu’elle a été pratiquée de nos jours, depuis Fustel de Coulanges jusqu’à Michel Foucault, en passant par l’école des Annales. Conformément à l’esprit herderien, cette histoire est, non plus histoire des gouvernants et des hommes de guerre, mais histoire des peuples, histoire des gens, histoire de tous. L’histoire continuiste, dont certains ont la nostalgie, c’est la mythologie du pouvoir, de ce pouvoir qui est, d’ailleurs, souvent responsable précisément des coupures, des cassures dans l’histoire des simples gens et de leurs mentalités, comme il est responsable de l’enfermement des ethnies en elles-mêmes, de leur emprisonnement dans des frontières fermées, bloquant les échanges spontanés entre cultures.

Ce que dit Giuseppe Cocchiara (1981 : 21) de Gian Battista Vico, à savoir qu’avec lui, les traditions populaires entrent, de manière décisive, dans l’histoire, qu’avec lui aussi, les peuples dits « primitifs » sont appelés à faire partie de l’histoire de l’humanité et qu’à ce titre, il est un précurseur des méthodes de l’ethnologie, on pourrait le redire de Herder. Il n’y a pas de peuple qui ne soit dans l’histoire. L’égalité des peuples, c’est aussi cela, c’est l’égale vocation à entrer dans l’histoire et c’est l’égale sympathie que doit leur vouer l’historien. Les insuffisances de l’Aufklärung sur ce point ont persisté souvent jusqu’à nos jours.

Conclusions

Si nous ne perdons pas de vue que la culture allemande des XVIIIe et XIXe siècles a apporté beaucoup à celle de l’Est européen, en Russie même et chez les nations qui connaissent aujourd’hui un réveil démocratique, l’importance de Herder, qui y fut souvent lu et apprécié, n’échappera à personne.

Bien loin d’être un danger pour la démocratie, l’esprit herderien peut être un facteur qui permette d’exorciser les fantômes d’un nationalisme rétrograde et agressif, et d’intégrer les valeurs ethniques et nationales à un esprit démocratique rénové, où l’individualisme ne fasse pas obstacle au sens de la communauté et la recherche du bien-être à la créativité culturelle.

Mais pour que cela soit possible, il ne faut pas caricaturer la pensée de Herder et dévaloriser systématiquement l’une des conquêtes les plus précieuses de l’esprit scientifique, à savoir le perspectivisme, dans la mesure même où il nous permet de rendre justice à toutes les formes d’humanité.

En fait, il est paradoxal que l’on trouve aujourd’hui, du côté des philosophes et des spécialistes des sciences humaines, une remise en cause du perspectivisme et du particularisme linguistique et culturel, à un moment précisément où, à l’inverse, les spécialistes des sciences « dures » et des techniques haut de gamme en viennent au perspectivisme eux aussi – consciemment, car ils l’ont toujours pratiqué en fait – et, dans le travail même de la recherche et de l’invention technique et scientifique, vantent les mérites de la tradition culturelle et son potentiel de créativité.

L’utilisation de l’ordinateur va elle-même dans le sens du perspectivisme. Presque toujours l’ordinateur calcule faux, et il faut trouver son chemin dans le brouillard des erreurs. Or il y a plusieurs chemins possibles…

Dans la physique moderne, l’absence d’ambiguïté et le caractère prédictible des phénomènes a disparu, du fait, en particulier, de l’absence de simplicité du point de départ de la ligne d’événements à prévoir. Comme l’écrit l’épistémologue italien Tito Arecchi (1989), « l’existence d’un point de vue privilégié pour effectuer la mesure, sur laquelle tous les physiciens étaient d’accord, est tombée en disgrâce ». C’est du sein même de la théorie et de la pratique expérimentale physiciennes que surgit le perspectivisme.

Mais il y a un point sur lequel des physiciens et des techniciens se retrouvent pour rapprocher la science moderne des savoirs anciens : dans la recherche de la créativité, l’étude de la dynamique de l’invention scientifique et technique fait ressortir l’importance de l’oral, de l’expression parlée, dans la science et, par conséquent, l’importance de la langue et de l’enracinement de cette langue dans un terreau culturel particulier. Ce sont les physiciens et les technologues, aujourd’hui, qui deviennent herderiens. Je cite Jean-Marc Lévy-Leblond (1990 : 25-26), physicien théoricien : « On peut… tranquillement affirmer que la science, en France, est faite de beaucoup plus de mots français (parlés) qu’anglais (écrits). Qu’il soit nécessaire de rappeler cette évidence montre à quel point le débat est faussé par une grave erreur de conception sur la nature de la recherche scientifique, identifiée à son produit final (les publications), plutôt qu’à son activité réelle. Or cette vitalité de la langue naturelle dans la science est utile et féconde. La science se fait comme elle se parle. A s’énoncer, donc à se penser, dans une langue autre que la langue ambiante, elle perdrait son enracinement dans le terreau culturel commun et serait ipso facto privée d’une source essentielle, même si elle est souvent invisible, de sa dynamique. Les mots ne sont pas des habits neutres pour les idées : c’est souvent par leur jeu libre et inattendu que se fait l’émergence des idées neuves… Et cela est encore plus vrai si l’on considère l’autre versant de la recherche scientifique, celui non de la création novatrice, mais de la réflexion critique. »

Et André-Yves Portnoff, directeur délégué de Science et technologie, va dans le même sens. Avec David Landes, il regrette que beaucoup de responsables du tiers monde « cultivent l’illusion de moderniser leur pays en faisant table rase de leur héritage historique », alors qu’« aujourd’hui, la créativité technologique et industrielle, comme la créativité artistique, fait appel à l’imaginaire », et que, de ce point de vue, « chaque langue, dans toute son épaisseur historique, avec toutes ses strates de mémoire collective, constitue un instrument d’une richesse indispensable » (1990 : 26).

A entendre de tels propos, l’ombre de Herder frémirait d’aise dans l’au-delà. Mais à propos de Herder faut-il parler d’ombre ? Ou de lumière ? Nous optons pour la lumière.

Max Caisson,

« Lumière de Herder », Terrain, numero-17 – En Europe, les nations (octobre 1991)

———————————

Bibliographie :

Arecchi T., 1989. « Chaos et complexité », Le Monde/Liber, n° 1, oct.

Cassirer E., 1970. La philosophie des Lumières, Paris, Fayard (Die Philosophie der Aufklärung, Tübingen, 1932).

Cocchiara G., 1981. Storia del folklore in Italia, Palerme, Sellerio.

Finkielkraut A., 1987. La défaite de la pensée, Paris, Gallimard.

Herder J. G., 1977. Traité sur l’origine de la langue, Paris, Aubier (Abhändlung über den Ursprung der Sprache, 1770).

1964. Une autre philosophie de l’histoire, Paris, Aubier (Auch eine Philosophie der Geschichte, 1774).

1962. Idées pour la philosophie de l’histoire de l’humanité, Paris, Aubier (Ideen zur Philosophie der Geschichte der Menschheit, 1784).

Herzen A. I., 1843. « Le dilettantisme dans la science », Annales de la patrie.

Hume D., 1947 (1751). Essai de morale, in Enquête sur les principes de la morale, trad. de A. Leroy, Paris, Aubier.

Kant E., 1947. Philosophie de l’Histoire (Opuscules), trad. de St. Piobetta, Paris, Aubier.

1957 (1797). Fondements de la métaphysique des mœurs, trad. de V. Delbos, Paris, Delagrave.

Lévi-Bruhl L., 1890. L’Allemagne depuis Leibniz, Paris, Hachette.

Lévy-Leblond J.-M., 1990. « Une recherche qui se fait comme elle se parle… », Le Monde diplomatique, janv.

Portnoff A.-Y., 1990. « La créativité victime des jargons », Le monde diplomatique, janv.

Roheim G., 1972. Origine et fonction de la culture, Paris, Gallimard.

Serres M., 1968. Le système de Leibniz et ses modèles mathématiques, I, Paris, PUF.

Todorov T., 1989. Nous et les autres, Paris, Le Seuil.

———————–

Notes :

1 – Cf. Finkielkraut (1987).

2 – J. de Maistre appelle Herder « l’honnête comédien qui enseignait l’Evangile en chaire et le panthéisme dans ses écrits ». C’est dire la sympathie qu’il éprouvait pour lui…

3 – Cf. l’article « Français » dans l’Encyclopédie.

4 – En ce qui concerne l’éthique herderienne, voir, dans le présent article, le paragraphe intitulé « Un eudémonisme relativiste. ».

5 – Voir notamment Roheim 1972.

6 – On pourrait, sur ce point, comparer la pensée de Herder avec certaines thèses de Cl. Lévi-Strauss.

7 – Leibniz, 1710. Essais de Théodicée : paragraphe 202.

8 – La preuve est que, pour lui, la prééminence actuelle de l’Europe est due, pour une part, à l’extraordinaire mélange de populations et de cultures qui la caractérise : « En aucun continent les peuples ne se sont autant mélangés qu’en Europe ; en aucun autre ils n’ont si radicalement et si souvent changé de résidences, et avec celles-ci de mode de vie et de mœurs… fusion sans laquelle l’esprit général européen aurait difficilement pu s’éveiller » (Herder 1962 : 309).

9 – Voltaire, Essai sur l’histoire générale et l’esprit des nations depuis Charlemagne jusqu’à nos jours, ch. III.

10 – Voir particulièrement le chapitre intitulé « Les voies du racialisme » dans l’ouvrage de Todorov (1989 : 179 et sq.).

Otto Strasser nasce il 10 settembre 1897 in una famiglia di funzionari bavaresi. Suo fratello Gregor (che sarà uno dei capi del partito nazista ed un serio concorrente di Hitler) è maggiore di cinque anni. L’uno e l’altro beneficiano di solidi antecedenti familiari: il padre Peter, che si interessa di economia politica e di storia, pubblica sotto lo pseudonimo di Paaul Weger un opuscolo intitolato Das neue Wesen, nel quale si pronuncia per un socialismo cristiano e sociale. Secondo Paul Strasser, fratello di Gregor e Otto, “in questo opuscolo si trova già abbozzato l’insieme del programma culturale e politico di Gregor e Otto, cioè un socialismo cristiano sociale, che è indicato come la soluzione alle contraddizioni e alle mancanze nate dalla malattia liberale, capitalista e internazionale dei nostri tempi.” Quando scoppia la Grande Guerra, Otto Strasser interrompe i suoi studi di diritto e di economia per arruolarsi il 2 agosto 1914 (è il più giovane volontario di Baviera). Il suo brillante comportamento al fronte gli varrà la Croce di Ferro di prima classe e la proposta per l’ Ordine Militare di Max-Joseph. Prima della smobilitazione nell’aprile/maggio 1919, partecipa con il fratello Gregor, nel Corpo Franco von Epp, all’assalto contro la Repubblica sovietica di Baviera. Ritornato alla vita civile Otto riprende i suoi studi a Berlino nel 1919 e fonda la “Associazione universitaria dei veterani socialdemocratici”.

Otto Strasser nasce il 10 settembre 1897 in una famiglia di funzionari bavaresi. Suo fratello Gregor (che sarà uno dei capi del partito nazista ed un serio concorrente di Hitler) è maggiore di cinque anni. L’uno e l’altro beneficiano di solidi antecedenti familiari: il padre Peter, che si interessa di economia politica e di storia, pubblica sotto lo pseudonimo di Paaul Weger un opuscolo intitolato Das neue Wesen, nel quale si pronuncia per un socialismo cristiano e sociale. Secondo Paul Strasser, fratello di Gregor e Otto, “in questo opuscolo si trova già abbozzato l’insieme del programma culturale e politico di Gregor e Otto, cioè un socialismo cristiano sociale, che è indicato come la soluzione alle contraddizioni e alle mancanze nate dalla malattia liberale, capitalista e internazionale dei nostri tempi.” Quando scoppia la Grande Guerra, Otto Strasser interrompe i suoi studi di diritto e di economia per arruolarsi il 2 agosto 1914 (è il più giovane volontario di Baviera). Il suo brillante comportamento al fronte gli varrà la Croce di Ferro di prima classe e la proposta per l’ Ordine Militare di Max-Joseph. Prima della smobilitazione nell’aprile/maggio 1919, partecipa con il fratello Gregor, nel Corpo Franco von Epp, all’assalto contro la Repubblica sovietica di Baviera. Ritornato alla vita civile Otto riprende i suoi studi a Berlino nel 1919 e fonda la “Associazione universitaria dei veterani socialdemocratici”.

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg O “mito”, como a “representação de uma batalha”, surge espontaneamente e exerce um efeito mobilizador sobre as massas, incute-lhes uma “fé” e torna-as capazes de actos heróicos, funda uma nova ética: essas são as pedras angulares do pensamento de Georges Sorel (1847-1922). Este teórico político, pelos seus artigos e pelos seus livros, publicados antes da primeira guerra mundial, exerceu uma influência perturbante tanto sobre os socialistas como sobre os nacionalistas.

O “mito”, como a “representação de uma batalha”, surge espontaneamente e exerce um efeito mobilizador sobre as massas, incute-lhes uma “fé” e torna-as capazes de actos heróicos, funda uma nova ética: essas são as pedras angulares do pensamento de Georges Sorel (1847-1922). Este teórico político, pelos seus artigos e pelos seus livros, publicados antes da primeira guerra mundial, exerceu uma influência perturbante tanto sobre os socialistas como sobre os nacionalistas.

„Man könnte über diesen ‚nationalen Dissidenten‘ achselzuckend hinweggehen, wenn nicht ein bestimmter Ton aufmerksam machen würde – ein Ton, der junge Deutsche in der Geschichte immer wieder beeindruckt hat. Konsequent, hochmütig und rücksichtslos – der Kompromiß wird der Verachtung preisgegeben. Mit den ‚feigen fetten Fritzen der Wohlstandsgesellschaft‘ will Sander nichts zu tun haben. Das bringt ihn Gott sei Dank in einen unversöhnlichen Gegensatz zur großen Mehrheit der Bürger der Bundesrepublik Deutschland. Was verhütet werden muß, ist, daß diese stilisierte Einsamkeit, diese Kleistsche Radikalität wieder Anhänger findet. Schon ein paar Tausend wären zuviel für die zivile parlamentarische Bundesrepublik.“ Diese Zeilen stammen aus einem Porträt über Hans-Dietrich Sander, das einer der besten Köpfe der deutschen Linken, der frühere SPD-Bundesgeschäftsführer Peter Glotz, im Jahr 1989 schrieb und in sein Buch Die deutsche Rechte – eine Streitschrift aufnahm. Die Faszination, die für Glotz von Sander ausging, ist auch in späteren Aufsätzen des leider schon im Jahr 2005 verstorbenen SPD-Vordenkers zu spüren, in denen immer wieder Sanders Name erwähnt wird. Glotz gehörte zu den wenigen Intellektuellen, die Sander sofort als geistige Ausnahmeerscheinung auf der deutschen Rechten wahrnahmen; vielleicht empfand er, der seine Autobiographie Von Heimat zu Heimat –Erinnerungen eines Grenzgängers nannte, eine gewisse Verwandtschaft mit Sander, der als junger Mann ein Wanderer zwischen Ost und West, zwischen den Systemen war.

„Man könnte über diesen ‚nationalen Dissidenten‘ achselzuckend hinweggehen, wenn nicht ein bestimmter Ton aufmerksam machen würde – ein Ton, der junge Deutsche in der Geschichte immer wieder beeindruckt hat. Konsequent, hochmütig und rücksichtslos – der Kompromiß wird der Verachtung preisgegeben. Mit den ‚feigen fetten Fritzen der Wohlstandsgesellschaft‘ will Sander nichts zu tun haben. Das bringt ihn Gott sei Dank in einen unversöhnlichen Gegensatz zur großen Mehrheit der Bürger der Bundesrepublik Deutschland. Was verhütet werden muß, ist, daß diese stilisierte Einsamkeit, diese Kleistsche Radikalität wieder Anhänger findet. Schon ein paar Tausend wären zuviel für die zivile parlamentarische Bundesrepublik.“ Diese Zeilen stammen aus einem Porträt über Hans-Dietrich Sander, das einer der besten Köpfe der deutschen Linken, der frühere SPD-Bundesgeschäftsführer Peter Glotz, im Jahr 1989 schrieb und in sein Buch Die deutsche Rechte – eine Streitschrift aufnahm. Die Faszination, die für Glotz von Sander ausging, ist auch in späteren Aufsätzen des leider schon im Jahr 2005 verstorbenen SPD-Vordenkers zu spüren, in denen immer wieder Sanders Name erwähnt wird. Glotz gehörte zu den wenigen Intellektuellen, die Sander sofort als geistige Ausnahmeerscheinung auf der deutschen Rechten wahrnahmen; vielleicht empfand er, der seine Autobiographie Von Heimat zu Heimat –Erinnerungen eines Grenzgängers nannte, eine gewisse Verwandtschaft mit Sander, der als junger Mann ein Wanderer zwischen Ost und West, zwischen den Systemen war. Während Sander in Büchern wie Marxistische Ideologie und allgemeine Kunsttheorie oder Die Auflösung aller Dinge seinen Warnungen vor einer Welt, die nur noch in Funktionalitäten aufgeht, eher die Form kultur- oder literaturwissenschaftlicher Begrifflichkeiten gibt, trägt er seine Argumentation ab 1990 als Herausgeber und Chefredakteur der Zeitschrift Staatsbriefe in einem staatsphilosophischen und politischen Kontext vor. Die Staatsbriefe erscheinen in zwölf Jahrgängen bis zum Dezember 2001; ihr Titelblatt ist immer von einem Oktagon auf grauem Grund geschmückt; dem Grundriß des apulischen Castel del Monte des Stauferkaisers Friedrich II. Wie Ernst Kantorowicz sieht Sander in Friedrich II. den Kaiser der deutschen Sehnsucht, dem es gelang, binnen weniger Jahre das sizilische Chaos zum Staat zu bändigen, die Einmischung des Papstes in innere Angelegenheiten zu beseitigen, die Macht der widerspenstigen Festlandsbarone und Verbündeten Roms zu brechen und ihren gesamten Burgenbestand zu übernehmen und ein straffes, nur ihm verantwortliches Beamtenkorps zu schaffen. Als Einzelner stieß Friedrich II. das Tor zur Neuzeit weit auf – Jahrhunderte, bevor diese wirklich begann. In seinem Genius bündelt sich für Sander all das, was auch heute einem sich selbst absolut setzenden Liberalismus und den von ihm ausgelösten Niedergangsprozessen entgegenzusetzen ist, nämlich die Fähigkeit zur Repräsentation, juristische Formkraft und die Möglichkeit zur Dezision, die politisch-theologischer Souveränität entspringt. Wo die letztgenannten Elemente fehlen, wächst nach Sander die Gefahr der Staatsverfehlung, die in den verschiedenen Formen des Totalitarismus der Moderne gipfelte. Freilich rechnet Sander auch den Liberalismus bzw. Kapitalismus amerikanischer Prägung zu den Formen totalitärer Macht, da er genauso wie Kommunismus und Nationalsozialismus das Ganze von einem Teil her definiere, woraus eine begrenzte Optik resultiere, mit der keine dauerhafte Herrschaft begründet werden kann. Wo im Nationalsozialismus und Kommunismus sich die jeweilige Staatspartei als Teil für das Ganze setzte, wird der Globalisierungsprozeß einseitig von den amerikanischen Wirtschaftsinteressen her gesteuert. Dies hat nach Sander fatale Folgen, die er in einem Aufsatz aus dem Jahr 2007 mit dem Titel Der Weg der USA ins totalitäre Desastre wie folgt beschreibt: „Die USA drangen in die gewachsenen Kulturen ein, lösten die Volkswirtschaften nach und nach auf, zwangen die Völker in politische Strukturen, die zu ihnen nicht paßten, und stellten sie durch beständige Einwanderung in Frage. Schließlich wurde die These laut, die Völker seien nur eine Erfindung der Historiker gewesen. Ist das nicht etwa Völkermord?“ Nein, es kann kein Zweifel bestehen, für Sander ist die Emanzipation des Politischen aus der Ordnung des Staates keine Errungenschaft, sondern ein Verhängnis.

Während Sander in Büchern wie Marxistische Ideologie und allgemeine Kunsttheorie oder Die Auflösung aller Dinge seinen Warnungen vor einer Welt, die nur noch in Funktionalitäten aufgeht, eher die Form kultur- oder literaturwissenschaftlicher Begrifflichkeiten gibt, trägt er seine Argumentation ab 1990 als Herausgeber und Chefredakteur der Zeitschrift Staatsbriefe in einem staatsphilosophischen und politischen Kontext vor. Die Staatsbriefe erscheinen in zwölf Jahrgängen bis zum Dezember 2001; ihr Titelblatt ist immer von einem Oktagon auf grauem Grund geschmückt; dem Grundriß des apulischen Castel del Monte des Stauferkaisers Friedrich II. Wie Ernst Kantorowicz sieht Sander in Friedrich II. den Kaiser der deutschen Sehnsucht, dem es gelang, binnen weniger Jahre das sizilische Chaos zum Staat zu bändigen, die Einmischung des Papstes in innere Angelegenheiten zu beseitigen, die Macht der widerspenstigen Festlandsbarone und Verbündeten Roms zu brechen und ihren gesamten Burgenbestand zu übernehmen und ein straffes, nur ihm verantwortliches Beamtenkorps zu schaffen. Als Einzelner stieß Friedrich II. das Tor zur Neuzeit weit auf – Jahrhunderte, bevor diese wirklich begann. In seinem Genius bündelt sich für Sander all das, was auch heute einem sich selbst absolut setzenden Liberalismus und den von ihm ausgelösten Niedergangsprozessen entgegenzusetzen ist, nämlich die Fähigkeit zur Repräsentation, juristische Formkraft und die Möglichkeit zur Dezision, die politisch-theologischer Souveränität entspringt. Wo die letztgenannten Elemente fehlen, wächst nach Sander die Gefahr der Staatsverfehlung, die in den verschiedenen Formen des Totalitarismus der Moderne gipfelte. Freilich rechnet Sander auch den Liberalismus bzw. Kapitalismus amerikanischer Prägung zu den Formen totalitärer Macht, da er genauso wie Kommunismus und Nationalsozialismus das Ganze von einem Teil her definiere, woraus eine begrenzte Optik resultiere, mit der keine dauerhafte Herrschaft begründet werden kann. Wo im Nationalsozialismus und Kommunismus sich die jeweilige Staatspartei als Teil für das Ganze setzte, wird der Globalisierungsprozeß einseitig von den amerikanischen Wirtschaftsinteressen her gesteuert. Dies hat nach Sander fatale Folgen, die er in einem Aufsatz aus dem Jahr 2007 mit dem Titel Der Weg der USA ins totalitäre Desastre wie folgt beschreibt: „Die USA drangen in die gewachsenen Kulturen ein, lösten die Volkswirtschaften nach und nach auf, zwangen die Völker in politische Strukturen, die zu ihnen nicht paßten, und stellten sie durch beständige Einwanderung in Frage. Schließlich wurde die These laut, die Völker seien nur eine Erfindung der Historiker gewesen. Ist das nicht etwa Völkermord?“ Nein, es kann kein Zweifel bestehen, für Sander ist die Emanzipation des Politischen aus der Ordnung des Staates keine Errungenschaft, sondern ein Verhängnis.

Wer träumt nicht davon, wieder Herr auf eigener Scholle zu sein und anstelle eines „jobs“ in der Dienstleistungsgesellschaft seiner Berufung nach einem ehrlichen Handwerk nachzugehen? Auch das Bewußtsein, sich nicht nur gesund ernähren, sondern selbst ernähren zu wollen, aus eigener Ernte, steigt. Wenn auch noch unmerklich, so schwindet doch die Identifikation lebensbewußter Menschen mit dem entwertenden Begriff Verbraucher. Alle sind heute nur noch Verbraucher, Verbraucher zunehmend nebulös produzierter Erzeugnisse. Lebensmittel sind zum anonymen Verbrauchsgut anonymer Verbraucher verkommen, denn es ist schwer geworden zu beurteilen, was wir essen und woher es kommt. Die Unkontrollierbarkeit des globalen Warenverschleppungssystems wird immer Lebensmittelskandale provozieren, insofern sie überhaupt öffentlich werden. Für diejenigen, die dies als befremdend und als eine nicht unumstößliche Gegebenheit empfinden, ist der eigene Garten je nach Größe längst zu einer partiellen Alternative geworden. Wer dort nicht stehen bleiben will, lebt in Hofgemeinschaften in der Landwirtschaft. Dafür müssen diese Stätten aber ein Hort der Arbeit und nicht nur der gemeinsamen Freizeitgestaltung sein. Auf der Grundlage der gestaltgebenden und schöpferischen Kraft einer gemeinsamen Weltanschauung wären Gemeinschaften möglich, die es auch und gerade im Heute zu einer alternativen Lebensführung und Lebensform schaffen können, deren Leistungen über die eigene Versorgung mit Lebensmitteln hinausgehen. Es geht um den Gedanken der Siedlung.

Wer träumt nicht davon, wieder Herr auf eigener Scholle zu sein und anstelle eines „jobs“ in der Dienstleistungsgesellschaft seiner Berufung nach einem ehrlichen Handwerk nachzugehen? Auch das Bewußtsein, sich nicht nur gesund ernähren, sondern selbst ernähren zu wollen, aus eigener Ernte, steigt. Wenn auch noch unmerklich, so schwindet doch die Identifikation lebensbewußter Menschen mit dem entwertenden Begriff Verbraucher. Alle sind heute nur noch Verbraucher, Verbraucher zunehmend nebulös produzierter Erzeugnisse. Lebensmittel sind zum anonymen Verbrauchsgut anonymer Verbraucher verkommen, denn es ist schwer geworden zu beurteilen, was wir essen und woher es kommt. Die Unkontrollierbarkeit des globalen Warenverschleppungssystems wird immer Lebensmittelskandale provozieren, insofern sie überhaupt öffentlich werden. Für diejenigen, die dies als befremdend und als eine nicht unumstößliche Gegebenheit empfinden, ist der eigene Garten je nach Größe längst zu einer partiellen Alternative geworden. Wer dort nicht stehen bleiben will, lebt in Hofgemeinschaften in der Landwirtschaft. Dafür müssen diese Stätten aber ein Hort der Arbeit und nicht nur der gemeinsamen Freizeitgestaltung sein. Auf der Grundlage der gestaltgebenden und schöpferischen Kraft einer gemeinsamen Weltanschauung wären Gemeinschaften möglich, die es auch und gerade im Heute zu einer alternativen Lebensführung und Lebensform schaffen können, deren Leistungen über die eigene Versorgung mit Lebensmitteln hinausgehen. Es geht um den Gedanken der Siedlung.

"Para o soldado - escreve Philippe Masson em L'Homme en Guerre 1901-2001 - para o verdadeiro combatente, a guerra se identifica com estranhas associações, uma mescla de fascinação e horror, humor e tristeza, ternura e crueldade. No combate, o homem pode manifestar covardia ou uma loucura sanguinária. Encontra-se sujeito entre o instinto pela vida e o instinto mortal, pulsões que podem lhe conduzir à morte mais abjeta ou ao espírito de sacrifício.

"Para o soldado - escreve Philippe Masson em L'Homme en Guerre 1901-2001 - para o verdadeiro combatente, a guerra se identifica com estranhas associações, uma mescla de fascinação e horror, humor e tristeza, ternura e crueldade. No combate, o homem pode manifestar covardia ou uma loucura sanguinária. Encontra-se sujeito entre o instinto pela vida e o instinto mortal, pulsões que podem lhe conduzir à morte mais abjeta ou ao espírito de sacrifício.

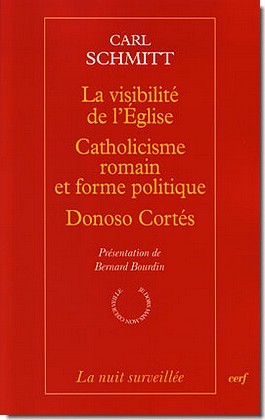

Principal ensayo del siempre polémico, incomprendido o mal entendido genio de Heidelberg. Publicado originalmente en 1932 la obra no se ha sustraido a una serie de revisiones por su autor adaptando ciertas reflexiones a secuencias vitales cuya magnitud es imposible de menospreciar. El vigor intelectual, el futurismo de sus planteamientos, así como la altura insospechada de una perspectiva que resulta desconcertadora para aquellos que no están preparados para la visión de horizontes nunca explorados, configuran la actual vigencia de esta obra. Incluso sigue aportando claves para lo que será el desarrollo de la modernidad en el siglo XXI.

Principal ensayo del siempre polémico, incomprendido o mal entendido genio de Heidelberg. Publicado originalmente en 1932 la obra no se ha sustraido a una serie de revisiones por su autor adaptando ciertas reflexiones a secuencias vitales cuya magnitud es imposible de menospreciar. El vigor intelectual, el futurismo de sus planteamientos, así como la altura insospechada de una perspectiva que resulta desconcertadora para aquellos que no están preparados para la visión de horizontes nunca explorados, configuran la actual vigencia de esta obra. Incluso sigue aportando claves para lo que será el desarrollo de la modernidad en el siglo XXI.