Un futur Iran bonapartiste ?

La question de l’avenir immédiat de l’Iran a probablement des implications plus profondes que toute autre crise contemporaine pour la survie à long terme de l’héritage aryen.

Par Jason Reza Jorjani

Ex: https://altright.com

Le 19 avril 2017, le Secrétaire d’Etat des USA Rex Tillerson a tenu une conférence de presse dans laquelle il a annoncé que l’Administration Trump allait entreprendre un « examen complet » de sa politique iranienne. Certains d’entre nous savent, même avant l’investiture [de Trump], qu’un changement de régime était envisagé pour l’Iran – la seule question étant : quelle sorte de changement de régime ? La fausse nouvelle de l’attaque au gaz d’Assad et les frappes de représailles en Syrie ne furent pas du tout rassurantes. Un mois plus tard, le 19 mai, la République Islamique a tenu sa douzième élection présidentielle. Une chose est claire : celui qui est élu pourrait être le dernier président de la théocratie chiite.

Il y a un plan pour détruire l’Iran, un plan élaboré avec l’Arabie Saoudite par ceux dans le complexe militaro-industriel américain qui considèrent les Saoudites comme un allié des Etats-Unis. Hillary Clinton, qui a des liens étroits avec les financiers saoudites, voulait certainement mettre en œuvre ce plan. A en juger par les références répétées à l’Arabie Saoudite dans les déclarations sur l’Iran faites par le Secrétaire à la Défense, le général « chien fou » Mattis, et le Secrétaire d’Etat Tillerson, il semble que ce plan pourrait commencer à être appliqué, même s’il semble qu’il y avait des plans substantiellement différents pour l’Iran à l’époque où le général Flynn et Steve Bannon étaient les principaux membres de l’équipe Trump. La réussite ou l’échec de ce plan saoudite aura un profond impact sur l’avenir des Occidentaux et d’autres dans le plus large monde indo-européen. La question de l’avenir immédiat de l’Iran a probablement des implications plus profondes que toute autre crise contemporaine pour la survie à long terme de l’héritage aryen.

Entouré par une douzaine d’Etats artificiels qui n’existaient pas avant les machinations coloniales européennes des XVIIIe et XIXe siècles, l’Iran est la seule vraie nation entre la Chine et l’Inde en Orient et la sphère de la civilisation européenne déclinante à l’Ouest et au Nord. Abréviation d’Irânshahr ou « Imperium aryen », l’Iran ne fut jamais désigné par la majorité à 55% perse du pays comme l’« Empire perse ». Les Grecs antiques forgèrent ce terme et il s’implanta en Occident. Il est dangereusement trompeur parce que si les Perses ont été le groupe ethno-linguistique le plus dominant culturellement à l’intérieur de la Civilisation Iranienne (jouant un rôle comparable aux Hans dans la Civilisation Chinoise), les Kurdes, les Ossètes, les Baloutches et d’autres sont ethniquement et linguistiquement iraniens même s’ils ne parlent pas la langue perse (appelée pârsi ou, erronément, fârsi en Iran de l’Ouest et dari ou tâjiki en Asie Centrale iranienne).

La combinaison d’« Iran » et de « Perse » a, depuis un bon nombre d’années, été utilisée comme partie d’un complot pour éroder encore plus l’intégrité territoriale de l’Iran en le réduisant à un Etat-croupion perse. Si les conspirateurs globalistes sans racines essayant de présenter l’« Iran » comme une construction conceptuelle de l’impérialisme perse sont certainement motivés par des considérations économiques et stratégiques, leur but ultime est l’effacement de l’idée même d’Iran ou d’Irânshahr. Ils voient le renouveau de cette idée comme peut-être la plus grande menace singulière pour leur agenda global, et depuis l’échec total du Mouvement de Réforme Islamique de 1997-2009 c’est justement ce renouveau qui est au cœur d’une révolution culturelle ultranationaliste connue sous le nom de Renaissance Iranienne.

Ce mouvement s’efforce de parvenir à une renaissance de la vision-du-monde préislamique de la Civilisation Iranienne, voyant le dénommé « âge d’or » de l’islam comme une dernière lueur ou un avortement de ce qui aurait pu être si l’Iran avait continué sa trajectoire de développement en tant que nation aryenne. Après tout, l’immense majorité des scientifiques et des ingénieurs qui furent forcés à écrire en arabe sous le Califat étaient des Iraniens ethniques dont la langue maternelle était le perse. A tous les égards, de la science à la technologie, à la littérature, à la musique, à l’art et à l’architecture, la soi-disant « Civilisation Islamique » agit comme un parasite s’appropriant une Civilisation Iranienne vraiment glorieuse qui était déjà âgée de 2000 ans avant que l’invasion arabo-musulmane impose l’islam et que les Mongols génocidaires la cimentent (en écrasant les insurrections perses en Azerbaïdjan, sur la côte caspienne, et au Khorasan).

La Renaissance Iranienne est basée sur le renouveau de principes et d’idéaux anciens, dont beaucoup sont partagés par l’Iran avec l’Europe à travers leur ascendance caucasienne commune et par des échanges interculturels intensifs. Cela inclut la pénétration profonde des Alains, des Scythes et des Sarmates iraniens dans le continent européen, et leur intégration finale avec les Goths dans la « Goth-Alanie » (Catalogne) et les Celtes dans « Erin » (un mot apparenté à « Iran »). Leur introduction de la culture de la Chevalerie (Javanmardi) et du mysticisme du Graal en Europe laissa sur l’ethos « faustien » de l’Occident un impact aussi profond que les idéaux « prométhéens » (en réalité, zoroastriens) du culte de la Sagesse et de l’industriosité innovante, qui furent introduits en Grèce par des siècles de colonisation perse.

La barrière civilisationnelle entre l’Iran et l’Europe a été très poreuse – des deux cotés. Après l’hellénisation de l’Iran durant la période d’Alexandre, l’Europe fut presque persisée par l’adoption du mithraïsme comme religion d’Etat à Rome. En partie comme une conséquence des machinations de la dynastie parthe et des opérations secrètes de sa flotte en Méditerranée, c’était imminent à l’époque où Constantin institutionnalisa le christianisme – probablement comme un rempart contre l’Iran.

Il ne faut donc pas être surpris si beaucoup des éléments essentiels de l’ethos de la Renaissance Iranienne semblent étonnamment européens : le respect pour la Sagesse et la recherche de la connaissance avant tout ; et donc aussi l’accent mis sur l’innovation industrieuse conduisant à un embellissement et une perfection utopiques de ce monde ; la culture de la liberté d’esprit chevaleresque, de l’humanitarisme charitable, et de la tolérance et de la largeur d’esprit ; un ordre politique qui est basé sur le droit naturel, où l’esclavage est considéré comme injuste et où les femmes fortes sont grandement respectées.

Mais il faut se souvenir que dans la mesure où l’Irânshahr s’étendait loin vers l’Est en Asie, ces valeurs étaient jadis aussi caractéristiques de la culture aryenne orientale – en particulier du bouddhisme du Mahayana, qui fut créé par les Kouchites iraniens. L’Iran colonisa l’Inde du Nord cinq fois et toute la Route de la Soie jusqu’à ce qui est maintenant la Chine du nord-ouest était peuplée par des Iraniens à l’apparence caucasienne, jusqu’aux conquêtes turques et mongoles aux XIe et XIIe siècles.

Alors que la Renaissance Iranienne veut « rendre l’Iran à nouveau grand » en faisant revivre cet héritage indo-européen, et même en reconstituant territorialement ce que les gens de notre mouvement appellent le « Grand Iran » (Irâné Bozorg), les globalistes sans racines, les sheikhs arabes du pétrole, et leurs collaborateurs islamistes en Turquie et au Pakistan veulent complètement effacer l’Iran de la carte. Evidemment ce n’est pas du goût des centaines de milliers de nationalistes iraniens qui se sont rassemblés devant le tombeau de Cyrus le Grand le 29 octobre 2016 pour chanter le slogan : « Nous sommes des Aryens, nous n’adorons pas les Arabes ! ». Le slogan est aussi clairement anti-islamique que possible dans les limites de la loi de la République Islamique. Le prophète Mahomet et l’Imam Ali étaient bien sûr des Arabes, donc le sens est très clair. On voit aussi clairement qui est celui que ces jeunes gens considèrent comme leur vrai messager, puisque l’autre slogan le plus chanté était : « Notre Cyrus aryen, tu es notre honneur ! ».

Depuis le soulèvement brutalement écrasé de 2009, presque tous les Iraniens ont rejeté la République Islamique. Beaucoup d’entre eux, spécialement les jeunes, sont convaincus que l’islam lui-même est le problème. Ils se sont clandestinement convertis au néo-zoroastrisme qui est indistinguable de l’ultranationalisme iranien. L’image de Zarathoustra dans un disque ailé, symbolisant la perfection évolutionnaire de l’âme, connue sous le nom de « Farvahar », est partout : sur les pendentifs, les bagues, et même les tatouages (en dépit du fait que les tatouages, qui étaient omniprésents parmi les Scythes, étaient bannis par le zoroastrisme orthodoxe). Maintenant même des éléments-clés dans le régime, spécialement les Gardiens de la Révolution, lisent des traités sur « la pensée politique de l’Imperium Aryen » qui sont extrêmement critiques vis-à-vis de l’islam tout en glorifiant l’ancien Iran.

Pendant ce temps, la soi-disant « opposition » en exil a été presque entièrement corrompue et cooptée par ceux qui souhaitent morceler le peu qui reste de l’Iran. D’un coté vous avez les gauchistes radicaux qui livrèrent en fait l’Iran aux Ayatollahs en 1979 avant que Khomeiny ne se retourne contre eux, forçant ceux qui échappèrent à l’exécution à partir en exil. D’un autre coté vous avez les partisans aveuglément loyaux du Prince héritier Reza Pahlavi, dont la vision – ou le manque de vision – s’aligne largement sur celle des gauchistes, du moins dans la mesure où elle cadre avec les buts des globalistes et des islamistes.

Les gens de l’opposition marxiste et maoïste à la République Islamique promeuvent le séparatisme ethnique, transplantant un discours anticolonialiste des « luttes de libération des peuples » dans un contexte iranien où il n’a rien à faire. Les Perses n’ont jamais méprisé personne. Nous fûmes des libérateurs humanitaires. Nous fûmes plutôt trop humanitaires et trop libéraux.

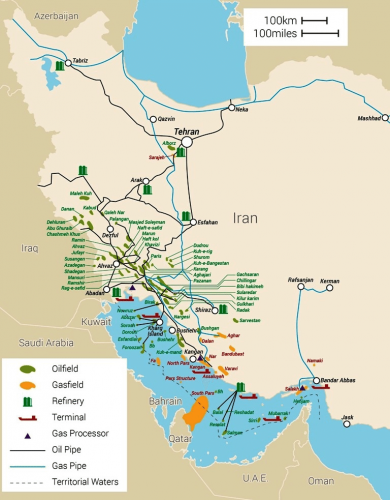

Les gauchistes des « peuples de l’Iran », comme si les Kurdes et les Baloutches n’étaient pas ethniquement iraniens et comme si un dialecte turcique n’avait pas été imposé à la province d’Azerbaïdjan, la source caucasienne de l’Iran, par les méthodes génocidaires de conquérants asiatiques à demi-sauvages. Tout en prétendant être féministes et partisans de la révolution prolétarienne, ces gauchistes acceptent d’être financés par l’Arabie Saoudite, qui veut les aider à séparer la région riche en pétrole et partiellement arabisée du Khuzistan de l’Iran et à la transformer en nation d’Al-Ahwaz, avec une façade côtière considérable sur ce qu’ils appellent déjà le « Golfe Arabe ». Le Kurdistan, l’Azerbaïdjan, Al-Ahwaz, le Baloutchistan : ces micro-Etats, ostensiblement nés des « mouvements de libération » gauchistes, seraient faciles à contrôler pour les capitalistes globaux sans racines. Dans au moins deux cas, Al-Ahwaz et le « Baloutchistan Libre », ils seraient aussi un terrain de développement pour une plus grande diffusion du terrorisme islamiste. Finalement, ils laisseraient les Perses dépourvus de presque toutes les ressources en pétrole et en gaz naturel de l’Iran, et contiendraient la marée montante de l’Identitarisme Aryen dans un Etat-croupion de « Perse ».

Le mieux armé et le mieux organisé de ces groupes gauchistes est celui des Mojaheddin-e-Khalq (MEK), qui est aussi connu sous les noms de Moudjahidines du Peuple de l’Iran (PMOI) et de Conseil National de la Résistance Iranienne (NCRI). Leurs guérillas armées mirent en fait Khomeiny et le pouvoir religieux au pouvoir avant d’être eux-mêmes dénoncés comme hérétiques. Leur réponse fut de prêter allégeance à Saddam Hussein et de mettre à sa disposition quelques unités militaires qui firent défection pendant la guerre Iran-Irak. Cela signifie qu’ils avaient de facto accepté l’occupation du Khuzistan par l’Irak. Plus tard, lorsqu’ils furent obligés de se repositionner dans le Kurdistan irakien, ils promirent aux Kurdes de soutenir la sécession kurde de l’Iran. Toute une foule de politiciens importants des Etats-Unis et de l’Union Européenne fut soudoyée pour apporter leur appui au leader du groupe, Maryam Radjavi, incluant John McCain, Newt Gingrich, Rudy Giuliani, John Bolton, et les NeoCons.

La majorité des Iraniens voit le MEK comme des traîtres, et le fait qu’ils sont essentiellement une secte dont les membres – ou les captifs – sont aussi coupés du monde extérieur que les Nord-Coréens n’arrange rien. Si cela signifie qu’ils ne seraient jamais capables de gouverner l’Iran efficacement, le MEK pourrait être utilisé comme un agent catalytique de déstabilisation durant une guerre contre la République Islamique.

C’est ici qu’intervient le Prince héritier Reza Pahlavi, avec son groupe de l’« opposition » iranienne en exil. La cabale globaliste et ses alliés arabes dans le Golfe Persique (Arabie Saoudite, Qatar, Emirats Arabes Unis) veulent créer un problème pour lequel il serait la solution. Il est dans leur poche.

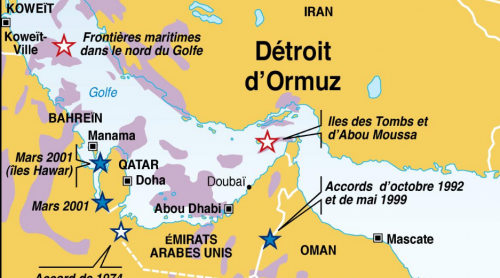

Lors d’une réunion du CFR à Dallas au début de 2016, que j’ai révélée dans une interview bien connue avec le journaliste indépendant résidant en Suède, Omid Dana de Roodast (« le Alex Jones perse »), Reza Pahlavi ironisa sur la soi-disant « rhétorique nationaliste exagérée » concernant la conquête arabo-musulmane génocidaire de l’Iran. Il parla de cette tragédie historique incomparable comme d’une chose qui, si elle a vraiment existé, est sans importance parce qu’elle a eu lieu il y a longtemps. En fait, il la voit comme un obstacle pour de bonnes relations de voisinage avec les Etats arabes du « Golfe ». Oh oui, dans des interviews avec des médias arabes il a parlé du Golfe éternellement Persique comme du « Golfe » tout court pour ne pas contrarier ses riches bienfaiteurs arabes. Reza Pahlavi a aussi permis à des représentants de ses organes de presse officiels de faire la même chose à plusieurs reprises. Il a même utilisé le terme dans un contexte qui implique que l’Iran pourrait abandonner plusieurs îles dans « le Golfe » avec l’idée d’améliorer les relations de voisinage (comme si le renoncement de son père à Bahreïn n’était pas suffisant !).

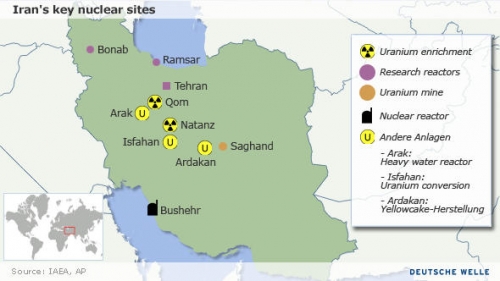

En fait, il a suggéré que l’Arabie Saoudite et d’autres gouvernements arabes inhumains devraient investir dans l’économie de l’Iran dans une mesure telle que l’Iran serait si dépendant d’eux que faire la guerre à ces nations deviendrait impossible. De plus, et de manière très embarrassante, le Prince héritier affirma que son futur Iran ne devrait pas avoir d’armes nucléaires parce qu’il aurait peur de passer une nuit dans son palais, puisque si l’Iran devait acquérir des armes atomiques alors d’autres nations rivales de la région auraient le droit de faire la même chose et pointeraient leurs missiles sur l’Iran.

Le pire de tout dans cette rhétorique est le plan très concret du Prince de soumettre la question d’une fédéralisation de l’Iran à un vote populaire ou à un référendum à l’échelle nationale. Ce n’est pas simplement une proposition. Il rencontre des individus et des groupes qui promeuvent le séparatisme et la désintégration territoriale de l’Iran, la première étape étant « l’éducation dans la langue maternelle » (autre que le perse) et l’autonomie régionale dans le contexte d’un système fédéral. En même temps, il a dénoncé comme « fascistes » les patriotes iraniens qui, au risque d’être emprisonnés ou tués, se sont rassemblés devant le tombeau de Cyrus le Grand le 29 octobre de l’année dernière et qui ont chanté le slogan « Nous sommes des Aryens, nous n’adorons pas les Arabes ! ». En dépit du fait que certains des mêmes protestataires chantèrent aussi des slogans félicitant le Prince héritier pour son anniversaire, c’est une erreur qu’ils ne referont jamais plus. Il fit même des remarques qui ridiculisaient de manière suggestive les partisans de la Tradition impériale perse.

Reza Pahlavi saisit toutes les occasions pour faire savoir que ses vrais idéaux sont la « démocratie libérale » et les « droits humains universels », des concepts occidentaux qu’il adopte imprudemment sans la moindre compréhension des problèmes fondamentaux qu’ils posent lorsqu’on les compare à notre philosophie politique iranienne aristocratique – qui influença des théories politiques occidentales essentielles comme celles de Platon, d’Aristote et de Nietzsche, et qui est beaucoup plus en accord avec celles-ci.

Si son acceptation de la démocratie et des droits de l’homme va jusqu’à un vote populaire sur une fédéralisation qui conduit à l’autonomie régionale et finalement à la sécession de nombreuses provinces, elle ne protège apparemment pas le criticisme envers l’islam. Et sous l’influence de ses manipulateurs occidentaux néolibéraux et de la police PC gauchiste de l’Occident, et totalement en désaccord avec le sentiment populaire parmi la jeunesse iranienne, il a affirmé que si l’islam devait être insulté ou que s’il devait y avoir de l’« islamophobie » dans le futur Iran, alors il vaudrait mieux que la République Islamique reste au pouvoir. Il a le toupet de dire cela tout en dénonçant ses critiques comme des agents de la République Islamique. Quand des dizaines d’éminents monarchistes patriotes signèrent un « Dernier Avertissement » (Akharin Hoshdâr) adressé à lui en juillet 2016, certains d’entre eux étant d’anciens proches conseillers de son père, il les accusa tous d’être des agents de la République Islamique qui falsifiaient ses déclarations et qui fabriquaient des preuves (ce qui était justement une affirmation clairement fausse et calomnieuse).

Nous n’étions pas des agents de la République Islamique, et nous ne serons jamais les complices d’une théocratie chiite sous sa présente forme. Mais étant donné la crise à laquelle nous faisons face aujourd’hui, nous devons envisager une alternative radicale pour les traîtres sécessionnistes de l’opposition gauchiste basée à Paris et les Shahs du Coucher de Soleil de Los Angeles qui seront tous trop heureux de faire régner leur Prince de Perse sur l’Etat-croupion qui restera de l’Iran après le « changement de régime ». Je propose un grand plan, une anticipation bonapartiste du règne de la terreur qui approche.

Ceux qui ont suivi mes écrits et mes interviews savent qu’il n’y a pas de plus sévère critique de l’islam, sous toutes ses formes, que votre serviteur. Je n’ai pas encore publié mes critiques vraiment sérieuses et rigoureuses de l’islam, incluant en particulier ma déconstruction de la doctrine chiite. Rien de ce que je vais proposer ne change le fait que j’ai la ferme intention de le faire dans les toutes prochaines années.

Cependant, nous entrons dans ce que Carl Schmitt appelait un « état d’urgence ». Dans cette situation exceptionnelle, où nous nous trouvons face à une menace existentielle pour l’Iran, il est important de faire la différence entre questions ontologiques ou épistémologiques et le genre de distinction ami/ennemi qui est définitive pour la pensée politique au sens approprié et fondamental. Les nationalistes iraniens ont des amis dans le système de la République Islamique, et le Seigneur sait que nous avons une quantité d’ennemis en-dehors de celui-ci.

Le jeune Gardien de la Révolution (Pasdaran) de Meshed qui récite Hafez en patrouillant le long de la frontière irakienne et attendant d’être tué par des séparatistes kurdes, mais dont la mère est kurde, et qui accompagne son père perse pour aller prier devant l’autel de l’Imam Reza en portant un Farvahar autour du cou n’est pas seulement un ami, il est le frère de tout vrai patriote iranien. Ce ne sont pas les Pasdarans qui ont tué et massacré de jeunes Iraniens pour mater la révolte de 2009, c’étaient des voyous paramilitaires dévoués au Guide Suprême Ali Khamenei – qui est maintenant sur son lit de mort.

Nous devons penser à l’avenir. Le cœur et l’âme de l’enseignement de Zarathoustra était son futurisme, son insistance sur l’innovation évolutionnaire. S’il était vivant aujourd’hui, il ne serait certainement pas zoroastrien. Franchement, même s’il avait été vivant durant l’Empire sassanide, il n’aurait pas été un zoroastrien au sens orthodoxe.

La Renaissance Iranienne considère la période sassanide comme le zénith de l’histoire de l’Iran, « l’apogée avant le déclin spectaculaire ». Mais les deux plus grands hérétiques, du point de vue de l’orthodoxie zoroastrienne, avaient le soutien de l’Etat sassanide. Chapour 1er était le patron de Mani, qui créa une religion mondiale syncrétique dans laquelle Gautama Bouddha et le Christ gnostique étaient vus comme des Shaoshyants (des Sauveurs zoroastriens) et des successeurs légitimes de Zarathoustra. Le manichéisme se répandit jusque dans le sud de la France en Occident, où il suscita la Sainte Inquisition en réaction contre lui, et jusqu’en Chine en Orient, où Mani était appelé « le Bouddha de Lumière » et où son enseignement influença le développement du bouddhisme mahayana. L’ésotériste libertin Mazdak, dont la révolution socialiste était d’après moi plus nationale-bolchevique que communiste, reçut le plein appui de l’empereur perse sassanide Kavad 1er. Même Khosrô Anushiravan, qui écrasa le mouvement mazdakien, n’était pas du tout un zoroastrien orthodoxe. C’était un néo-platonicien, qui invita les survivants de l’Académie à trouver refuge dans les bibliothèques et les laboratoires iraniens comme Gondechapour après la fermeture des dernières universités de l’Europe sur l’ordre de Justinien.

De plus, l’évolution de la tradition spirituelle iranienne fondée par Zarathoustra ne prit pas fin avec la Conquête islamique. La Renaissance Iranienne condamne Mazdak sans équivoque, et pourtant Babak Khorrdamdin est considéré comme un héros de la résistance nationaliste contre le Califat arabe. Mais les partisans de Khorrdamdin en Azerbaïdjan étaient des mazdakiens ! Une claire ligne peut être tracée depuis le mouvement mazdakien, à travers les Khorrdamdin, jusqu’aux groupes chiites ésotériques tels que les Ismaéliens nizarites ou Ordre des « Assassins » comme ils sont généralement connus en Occident. Combattant contre le Califat et les Croisés simultanément, il n’y eut jamais de plus grand champion de la liberté et de l’indépendance iraniennes que Hassan Sabbah. Et sa variété d’ésotérisme chiite ne déclina pas non plus avec la secte ismaélienne.

Il y a encore en Iran aujourd’hui des religieux supposément chiites qui doivent plus à Sohrawardi, à travers Mullah Sadra, qu’à l’enseignement réel de l’Imam Ali. A l’époque du Sixième Imam, Jaafar al-Sadiq, la foi chiite fut cooptée par les partisans iraniens luttant contre me Califat sunnite. Le genre de doctrine chiite que certains des collègues de l’Ayatollah Khomeiny tentèrent d’imposer à l’Iran en 1979 représenta une reconstruction radicale du premier chiisme arabe, pas le genre d’ésotérisme chiite qui donna naissance à la dynastie safavide. Cette dernière permit à l’Iran de resurgir en tant qu’Etat politique distinct séparé et opposé au Califat Ottoman sunnite et à un Empire Moghol qui était aussi tombé dans le fondamentalisme islamique après que la littérature et la philosophie persisées d’Akbar se soient révélées être un rempart insuffisant contre celui-ci. Certains de ces chiites persisés sont présents aux plus hauts niveaux dans la structure de pouvoir de la République Islamique. Ils doivent être accueillis dans la communauté du nationalisme iranien, et même dans la communauté de la Renaissance Iranienne.

Il y a encore en Iran aujourd’hui des religieux supposément chiites qui doivent plus à Sohrawardi, à travers Mullah Sadra, qu’à l’enseignement réel de l’Imam Ali. A l’époque du Sixième Imam, Jaafar al-Sadiq, la foi chiite fut cooptée par les partisans iraniens luttant contre me Califat sunnite. Le genre de doctrine chiite que certains des collègues de l’Ayatollah Khomeiny tentèrent d’imposer à l’Iran en 1979 représenta une reconstruction radicale du premier chiisme arabe, pas le genre d’ésotérisme chiite qui donna naissance à la dynastie safavide. Cette dernière permit à l’Iran de resurgir en tant qu’Etat politique distinct séparé et opposé au Califat Ottoman sunnite et à un Empire Moghol qui était aussi tombé dans le fondamentalisme islamique après que la littérature et la philosophie persisées d’Akbar se soient révélées être un rempart insuffisant contre celui-ci. Certains de ces chiites persisés sont présents aux plus hauts niveaux dans la structure de pouvoir de la République Islamique. Ils doivent être accueillis dans la communauté du nationalisme iranien, et même dans la communauté de la Renaissance Iranienne.

La Renaissance italienne eut recours à la Rome païenne pour accomplir une revitalisation civilisationnelle, mais elle n’abolit pas le christianisme. Benito Mussolini non plus, lorsqu’il adopta comme but explicite une seconde Renaissance italienne et un renouveau de l’Empire romain. Au contraire, le Duce recruta le catholicisme romain comme allié de confiance dans son vaillant combat contre le capitalisme sans racines, parce qu’il savait que les catholiques romains étaient « romains », même en Argentine.

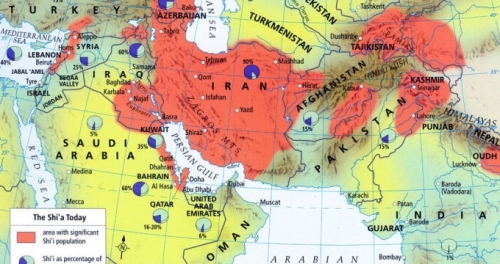

De même, aujourd’hui, les chiites sont d’une manière ou d’une autre culturellement iraniens, même dans l’Azerbaïdjan du nord turcique, dans l’Irak arabophone et à Bahreïn, sans parler de l’Afghanistan du nord-ouest où le perse demeure la lingua franca. Si les néo-zoroastriens, en Iran ainsi que dans les parties du Kurdistan actuellement en-dehors des frontières de l’Iran, devaient s’allier avec les chiites persisés, cela ferait plus que consolider l’intégrité territoriale de l’Iran. Cela établirait un nouvel Empire perse, fournissant à l’Iran central de nombreuses zones-tampons et positions avancées chiites tout en réincorporant aussi, sur la base du nationalisme iranien, des régions qui sont ethno-linguistiquement iraniennes mais pas chiites – comme le grand Kurdistan et le Tadjikistan (incluant Samarkand et Boukhara).

Ce que je propose est plus qu’un coup d’Etat militaire à l’intérieur de la République Islamique. Le qualificatif de « bonapartiste » est seulement en partie exact. Nous avons besoin d’un groupe d’officiers dans les Pasdarans qui reconnaissent que la Timocratie, comme Platon la nommait, est seulement la seconde meilleure forme de gouvernement et que leur pouvoir aura besoin d’être légitimé par un roi philosophe et un conseil des Mages avec l’intelligence et la profondeur d’âme requises pour utiliser le pouvoir étatique afin de promouvoir la Renaissance Iranienne qui est déjà en cours. Ironiquement, si nous séparons la forme politique de la République Islamique de son contenu – comme le ferait un bon platonicien –, les structures centrales antidémocratiques et intolérantes du régime sont remarquablement iraniennes. Le Conseil Gardien (Shorâye Negahbân) est l’Assemblée des Mages et le Gouvernement du Docte (Velâyaté Faqih) est le Shâhanshâhé Dâdgar qui possède le farr – celui qui est justement guidé par la divine gloire de la Sagesse. Cela ne devrait pas être surprenant puisque, après tout, l’Ayatollah Khomeiny emprunta ces concepts à Al Fârâbî qui, au fond de lui, était tout de même un Aryen.

Le Parti Pan-Iranien, qui est issu du Parti des Travailleurs National Socialiste (SUMKA) de l’Iran du début des années 1940, est un élément-clé dans ce stratagème. Célèbre pour son opposition parlementaire très bruyante à l’abandon de Bahreïn par Mohammad Reza Shah Pahlavi en 1971, l’opposition loyale ultranationaliste (c’est-à-dire à la droite du Shah) du régime Pahlavi pourrait devenir l’opposition loyale de la République Islamique si elle était légalisée après un coup d’Etat par ceux parmi les Gardiens de la Révolution qui comprennent la valeur du nationalisme iranien pour affronter la menace existentielle imminente pour l’Iran.

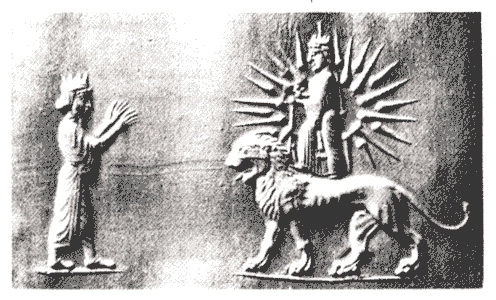

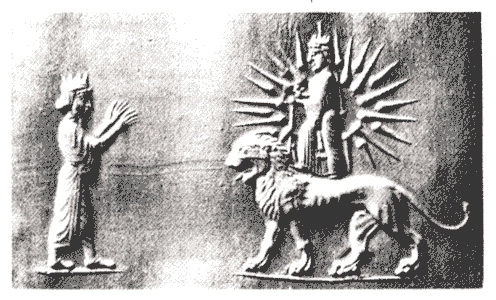

A la différence de tous les autres partis d’opposition, l’existence clandestine du Parti Pan-Iranien a été seulement à peine tolérée par la République Islamique. Bien qu’il soit techniquement illégal et qu’il ne puisse pas présenter de candidats aux élections, il n’a pas été écrasé par le régime – parce la loyauté du parti envers l’Iran ne fait pas de question. Le parti a des liens étroits avec les principaux intellectuels de la Renaissance Iranienne et avec les membres les plus patriotes du clergé chiite. S’il était le seul parti d’opposition légal, tous les nationalistes iraniens voteraient pour lui et en une seule élection, ou deux tout au plus, les Pan-Iraniens obtiendraient une majorité au Parlement. Leur premier acte de législation devrait être quelque chose avec un grand pouvoir symbolique et peu de chances de réaction hostile de la part du complexe militaro-industriel de la République Islamique : le retour du Lion et du Soleil comme drapeau national légitime de l’Iran (l’un des buts déclarés du Parti).

Le Lion et le Soleil incarne parfaitement l’ambiguïté de l’identité iranienne. Les chiites affirment que c’est une représentation zoomorphique de l’Imam Ali, « le Lion de Dieu » (Assadollâh) et que l’épée brandie par le lion est le Zulfaqâr. La République Islamique remplaça ce symbole parce que ses fondateurs fondamentalistes savaient que c’était faux. Le Lion et le Soleil est un drapeau aryen extrêmement ancien, qui représente probablement Mithra c’est-à-dire le Soleil entrant dans la maison zodiacale du Lion.

De plus, les néo-zoroastriens ont tort de croire que l’épée recourbée est un ajout islamique (et qu’elle doit donc être remplacée par une épée droite). Au contraire, l’épée du lion est la serpe, qui était le symbole du cinquième degré de l’initiation dans le mithraïsme, connu sous le nom de Perses. Perses était le fils de Perseus, le progéniteur des Aryens perses. Il tranche la tête de la Gorgone avec une épée-serpe. Les Gorgones étaient sacrées pour les Scythes, les tribus rivales des Perses à l’intérieur du monde iranien. Perseus brandissant la tête tranchée de la Méduse symbolise le fait qu’il a saisi sa puissance (sa Shakti) tout en restant humain (sans se transformer en pierre). Mais oui, bien sûr, c’est l’Imam Ali.

Dans le nouvel Iran, les néo-zoroastriens devront tolérer les rituels de deuil de masse de Moharrem et de l’Achoura, car après tout leurs vraies origines sont dans les anciennes processions de deuil iraniennes pour le martyre de Siyâvosh. En échange, les chiites devront tolérer les tatouages de Farvahar chez les femmes néo-zoroastriennes qui ont été tellement ciblées par la République Islamique qu’elles sont prêtes à sauter nues par-dessus des feux de joie Châhâr-Shanbeh Suri allumés en brûlant des Corans.

A la différence de ce qui se passait à l’époque de Reza Shah Pahlavi II, et de la République Arabe d’Al-Ahwaz proposée, il n’y aura pas de criminalisation de l’islamophobie dans l’Iran nationaliste. En fait, la composante chiite du nouveau régime servira à légitimer l’alliance de l’Iran avec les nationalistes européens combattant la cinquième colonne de nouveau Califat sunnite à Paris, Londres, Munich et Dearborn. Les têtes de l’hydre sont en Arabie Saoudite, en Turquie, et au Pakistan. Le Lion de Mithra tranchera ces têtes avec son épée. Pour la première fois depuis la dynastie fatimide des Assassins, La Mecque et Médine seront gouvernées par des mystiques chiites. Les Perses fêteront cela à Persépolis.

Il n’y a pas de doute là-dessus. Le temps est venu pour l’Iran bonapartiste – la forteresse islamique-aryenne et nationaliste-religieuse de la résistance contre les globalistes sans racines, pour qui « Rien n’est vrai, et tout est permis ». Il ne nous reste qu’une question : « Qui est le Napoléon perse ? ».

The Carter Administration was not happy with this, sending Vice President Walter Mondale (picture) to France and West Germany to "inform" them that the U.S. would henceforth oppose the sale of nuclear energy technology to the Third World...and thus they should do so as well. West Germany's nuclear deal with Brazil and France's promise to sell nuclear technology to South Korea had already come under heavy attack.

The Carter Administration was not happy with this, sending Vice President Walter Mondale (picture) to France and West Germany to "inform" them that the U.S. would henceforth oppose the sale of nuclear energy technology to the Third World...and thus they should do so as well. West Germany's nuclear deal with Brazil and France's promise to sell nuclear technology to South Korea had already come under heavy attack.

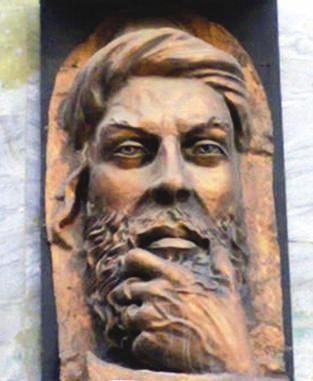

On Jan 4th, 1979, the Shah named Shapour Bakhtiar (picture), a respected member of the National Front, as Prime Minister of Iran. Bakhtiar was held in high regard by not only the French but Iranian nationalists. As soon as his government was ratified, Bakhtiar began pushing through a series of major reform acts: he completely nationalised all British oil interests in Iran, put an end to the martial law, abolished the SAVAK, and pulled Iran out of the Central Treaty Organization, declaring that Iran would no longer be "the gendarme of the Gulf".

On Jan 4th, 1979, the Shah named Shapour Bakhtiar (picture), a respected member of the National Front, as Prime Minister of Iran. Bakhtiar was held in high regard by not only the French but Iranian nationalists. As soon as his government was ratified, Bakhtiar began pushing through a series of major reform acts: he completely nationalised all British oil interests in Iran, put an end to the martial law, abolished the SAVAK, and pulled Iran out of the Central Treaty Organization, declaring that Iran would no longer be "the gendarme of the Gulf".

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

Het lijkt erop dat de Iraniërs over een sterke mentaliteit beschikken om met een wereldmacht de confrontatie op te zoeken. Is hiervoor een historische verklaring?

Het lijkt erop dat de Iraniërs over een sterke mentaliteit beschikken om met een wereldmacht de confrontatie op te zoeken. Is hiervoor een historische verklaring?

“Western imperialism in Western Asia is usually symbolized by Napoleon Bonaparte’s war against the Ottomans in Egypt and Syria (1798–1801). Ever since the beginning of the 19th century, the West has been sucking on the jugular vein of the Moslem body politic like a veritable vampire whose thirst for Moslem blood is never sated and who refused to let go. Since 1979, Iran, which has always played the role of the intellectual leader of the Islamic world, has risen up to put a stop to this outrage against God’s law and will, and against all decency. So it is a process of revisioning a false and distorted vision of reality back to what reality actually is and should be: a just order. But this revisioning is hampered both by the fact that the vampires control the reality studio, and the ineptitude of Moslem intellectuals and their failure to understand even the rudiments of the history of Western thought, be this in its ancient, medieval, or modern period.”

“Western imperialism in Western Asia is usually symbolized by Napoleon Bonaparte’s war against the Ottomans in Egypt and Syria (1798–1801). Ever since the beginning of the 19th century, the West has been sucking on the jugular vein of the Moslem body politic like a veritable vampire whose thirst for Moslem blood is never sated and who refused to let go. Since 1979, Iran, which has always played the role of the intellectual leader of the Islamic world, has risen up to put a stop to this outrage against God’s law and will, and against all decency. So it is a process of revisioning a false and distorted vision of reality back to what reality actually is and should be: a just order. But this revisioning is hampered both by the fact that the vampires control the reality studio, and the ineptitude of Moslem intellectuals and their failure to understand even the rudiments of the history of Western thought, be this in its ancient, medieval, or modern period.”

Until 1935, Iran was referred to internationally as “Persia” (or La Perse), and the Iranian people were broadly identified as “Persians.” This was the case despite the fact that Persians always referred to themselves as Iranians (Irâni) and used the term Irânshahr (Old Persian Aryâna Khashatra) or “Aryan Imperium” in order to designate what Westerners call the “Persian Empire.”

Until 1935, Iran was referred to internationally as “Persia” (or La Perse), and the Iranian people were broadly identified as “Persians.” This was the case despite the fact that Persians always referred to themselves as Iranians (Irâni) and used the term Irânshahr (Old Persian Aryâna Khashatra) or “Aryan Imperium” in order to designate what Westerners call the “Persian Empire.” We have entered the era of a clash of civilizations rather than a conflict between nation states. Consequently, the recognition of Iran as a distinct civilization, one that far predates the advent of Islam and is now evolving beyond the Islamic religion, would be of decisive significance for the post-national outcome of a Third World War.

We have entered the era of a clash of civilizations rather than a conflict between nation states. Consequently, the recognition of Iran as a distinct civilization, one that far predates the advent of Islam and is now evolving beyond the Islamic religion, would be of decisive significance for the post-national outcome of a Third World War.

Le Patriot est une bonne vieille histoire (depuis 1976-1984) d’un caractère exceptionnel dans la durabilité et la solidité de la farce déguisée en simulacre. La firme Raytheon, qui en est la mère-nourricière (voir le secrétaire à la défense Esper pour plus d’informations : il y officia pendant dix ans), sort régulièrement une nouvelle version (PAC-1, PAC-2, PAC-3...) après une démonstration des caractéristiques catastrophiques de sa progéniture, assurant alors que ses “défauts de jeunesse” sont corrigés ; il est manifeste qu’il y a eu des changementsentre chaque version par rapport à la précédente, puisque chaque version coûte beaucoup plus cher que la précédente. Les premiers exploits du Patriot datent de la première Guerre du Golfe, puis enchaînant sur la seconde (quelques détails

Le Patriot est une bonne vieille histoire (depuis 1976-1984) d’un caractère exceptionnel dans la durabilité et la solidité de la farce déguisée en simulacre. La firme Raytheon, qui en est la mère-nourricière (voir le secrétaire à la défense Esper pour plus d’informations : il y officia pendant dix ans), sort régulièrement une nouvelle version (PAC-1, PAC-2, PAC-3...) après une démonstration des caractéristiques catastrophiques de sa progéniture, assurant alors que ses “défauts de jeunesse” sont corrigés ; il est manifeste qu’il y a eu des changementsentre chaque version par rapport à la précédente, puisque chaque version coûte beaucoup plus cher que la précédente. Les premiers exploits du Patriot datent de la première Guerre du Golfe, puis enchaînant sur la seconde (quelques détails

Il y a encore en Iran aujourd’hui des religieux supposément chiites qui doivent plus à Sohrawardi, à travers Mullah Sadra, qu’à l’enseignement réel de l’Imam Ali. A l’époque du Sixième Imam, Jaafar al-Sadiq, la foi chiite fut cooptée par les partisans iraniens luttant contre me Califat sunnite. Le genre de doctrine chiite que certains des collègues de l’Ayatollah Khomeiny tentèrent d’imposer à l’Iran en 1979 représenta une reconstruction radicale du premier chiisme arabe, pas le genre d’ésotérisme chiite qui donna naissance à la dynastie safavide. Cette dernière permit à l’Iran de resurgir en tant qu’Etat politique distinct séparé et opposé au Califat Ottoman sunnite et à un Empire Moghol qui était aussi tombé dans le fondamentalisme islamique après que la littérature et la philosophie persisées d’Akbar se soient révélées être un rempart insuffisant contre celui-ci. Certains de ces chiites persisés sont présents aux plus hauts niveaux dans la structure de pouvoir de la République Islamique. Ils doivent être accueillis dans la communauté du nationalisme iranien, et même dans la communauté de la Renaissance Iranienne.

Il y a encore en Iran aujourd’hui des religieux supposément chiites qui doivent plus à Sohrawardi, à travers Mullah Sadra, qu’à l’enseignement réel de l’Imam Ali. A l’époque du Sixième Imam, Jaafar al-Sadiq, la foi chiite fut cooptée par les partisans iraniens luttant contre me Califat sunnite. Le genre de doctrine chiite que certains des collègues de l’Ayatollah Khomeiny tentèrent d’imposer à l’Iran en 1979 représenta une reconstruction radicale du premier chiisme arabe, pas le genre d’ésotérisme chiite qui donna naissance à la dynastie safavide. Cette dernière permit à l’Iran de resurgir en tant qu’Etat politique distinct séparé et opposé au Califat Ottoman sunnite et à un Empire Moghol qui était aussi tombé dans le fondamentalisme islamique après que la littérature et la philosophie persisées d’Akbar se soient révélées être un rempart insuffisant contre celui-ci. Certains de ces chiites persisés sont présents aux plus hauts niveaux dans la structure de pouvoir de la République Islamique. Ils doivent être accueillis dans la communauté du nationalisme iranien, et même dans la communauté de la Renaissance Iranienne.