Editor’s Note:

This text is the transcript by V. S. of Jonathan Bowden’s lecture on Evola delivered to the 27th meeting of the New Right in London on June 5, 2010. As usual, I have deleted a few false starts and introduced punctuation and paragraph breaks for maximum clarity. You can listen to it at YouTube here [2]. Three passages are marked unintelligible. If you can make out the words, please post a comment below or contact me at editor@counter-currents.com [3].

This is the 27th meeting of the New Right, and we’ve waited quite a long time to discuss one of the most important thinkers of the radical Right and of a Traditional perspective upon mankind and reality, and that is Baron Julius Evola.

Now, Evola is in some respects to the Right of everybody that we’ve ever considered in nearly any of these talks and not in a sort of unprofound or sententious manner. Julius Evola was somebody who rejected purposefully and metaphysically the modern world. Now, what does that mean? It basically means that at the beginning of the last century, Baron Evola, who is a Sicilian baron, decided that there are about four alternatives in relation to modern life for those of heroic spirit.

One was suicide and to make off with one’s self by opening one’s veins in the warm bath like Sicilian Mafiosi and Italian cardinals and Sicilian brigands and ancient Romans.

Another was to become a Nietzschean, which for many people in tradition is a modern version of some, but by no means all, of their ideas, and it’s a way of riding the tiger of modernity and dealing with that which exists around us now. Later, people like Evola and other perennial Traditionalists as we may well call them became increasingly critical of Nietzsche and regard him as a sort of decadent modern and an active nihilist with a bit of spirit and vigor but doesn’t really have the real position.

I make things quite clear. I would be regarded by most people as a Nietzschean, and philosophically that’s the motivation I’ve always had since my beginning. That’s why parties don’t really mean that much to me, because ideas are eternal and ideas and values come back, but movements and the ways and forms that they take and expressions that they have come and go.

Now, moving from the Nietzschean perspective, which of course relates to the great German thinker at the end of the 19th century and his active and quasi-existential and volitional view of man, is the idea of foundational religiosity or primary religious and spiritual purpose. In high philosophy, there are views which dominate everyone around us and modern media and everyone who goes to a tertiary educational college, such as a university, in the Western world. These are modern ideas, which are materialistic and anti-spiritual and aspiritual and anti-religious or antagonistic to prior religious belief so much so that it’s taken as a given that those are the views that one holds. All of the views that convulsed the Western intelligentsia since the Second European Civil War which ended in 1945, ideas like existentialism and behaviorism and structuralism and so on, are all atheistic and material views. They’ve been discussed in other meetings. As one goes back slightly, one has various currents of opinion such as Marxism and Freudianism and behaviorism beginning in the late 19th century and convulsing much of the 20th century.

Now, moving from the Nietzschean perspective, which of course relates to the great German thinker at the end of the 19th century and his active and quasi-existential and volitional view of man, is the idea of foundational religiosity or primary religious and spiritual purpose. In high philosophy, there are views which dominate everyone around us and modern media and everyone who goes to a tertiary educational college, such as a university, in the Western world. These are modern ideas, which are materialistic and anti-spiritual and aspiritual and anti-religious or antagonistic to prior religious belief so much so that it’s taken as a given that those are the views that one holds. All of the views that convulsed the Western intelligentsia since the Second European Civil War which ended in 1945, ideas like existentialism and behaviorism and structuralism and so on, are all atheistic and material views. They’ve been discussed in other meetings. As one goes back slightly, one has various currents of opinion such as Marxism and Freudianism and behaviorism beginning in the late 19th century and convulsing much of the 20th century.

But these are views that an advanced Evolian type of perspective rejects. These views are anti-metaphysical and often counter the idea that metaphysics doesn’t exist, that it’s the school returning of the late Medieval period, what was called the Medieval schoolmen. In some of his books, Evola talks about Heidegger, Martin Heidegger, of course, who got in trouble in the 1930s for his alleged academic positioning in relation to the most controversial regime of modernity. Heidegger, in my opinion, and I’ve talked about Heidegger before, was a quasi-essentialist to an essentialist thinker. Evola believes he’s an existentialist, but that’s largely by the by.

These anti-metaphysical views are that which surrounds us. All liberalism, all feminism, all quasi-Marxism, all bourgeois Marxism, all cultural Marxism, the extreme Left moderated a bit into the Center, high capitalist economics and the return of old liberalism against the Keynesianism which was the soft Marxism that replaced it earlier in the 20th century . . . All of these ideas are materialistic and atheistic and aspiritual and anti-metaphysical.

You could argue that the heroic Nietzschean dilemma in relation to what is called modernity is a quasi-metaphysical and metaphysically subjectivist view that there are values outside man and outside history that human beings commune with by virtue of the intensity with which they live their own lives. But there is a question mark over (1) the supernatural and (2) whether there is anything beyond, outside man within which those values could be anchored.

So, the idea of permanence, the idea of a metaphysical realm which most prior civilizations are based on—indeed Evola and the Traditionalists would say all prior civilizations are based on—is questioned by the Nietzschean compact. It is ultimately, maybe, the beginnings of a very Right-wing modern view, but it is a modernist view. Take it or leave it.

The sort of viewpoint that Evola moved towards, and there was a progression in his early life and spiritual career and intellectual and writing career, is what we might call metaphysical objectivism. This is called in present day language foundationalism or fundamentalism in relation to religiosity. Fundamentalism, like the far Right, are the two areas of culture that can’t be assimilated in what exists out there in [unintelligible] Street. They’re the two things that are outside and that’s why they can never entirely be drawn in.

Now, metaphysical objectivism is the absolute belief in the supernatural, the absolute belief in other states of reality, the absolute belief in gods and goddesses, the absolute belief in one supreme power (monotheism as against polytheism, for example), the absolute belief that certain iterizations, certain forms of language and spiritual culture exist outside man: truth, justice, the meaning of law, purposive or teleological information about how a life should be lived. Most people in Western societies now are so dumbed down and so degraded by almost every aspect of life that nearly any philosophical speculation about life is indeterminate and almost completely meaningless. It’s a channel which they never turn on.

Now, the type of metaphysical objectivism that Evola postulates as being an anchor for meaning in modern life can take many different forms. One of the great problems many Right-wing or re-foundational or primal movements or tribal movements or nationalistic movements of whatever character have is if there is a religion somewhere behind it–as there often is for many but not all of the key people involved in such movements and struggles–what form should that be? Everyone knows that culturally, and this is true of a formulation like GRECE or the New Right in France, as soon as you begin to get people of like-mind together they will split on whether they’re atheist or not, secularist or not, but they are also, on a deeper cultural level, split on whether they’re pagan influenced or Christian. Such divisions always bedevil Right-wing cultural and metapolitical groups.

The way that the Evolian Tradition looks at this is to engage in what is called perennialism. This is the inherent intellectual and ideological and theological idea that there are certain key truths in all of the major faiths. All of those faiths that have survived, that are recorded, that have come down to us, even their pale antecedents, even those dissident, deviant and would-be heretical elements of them that have been removed, in all of them can be seen a shard of the perspectival truth that these particular traditions could be said to manifest. Beneath this, of course, is the ethnic and racial idea that people in different groups within mankind as a body perceive reality differently, experience it differently, have different intellectual and linguistic responses to it, and form different cults, different myths, different religions because they are physically constituted in a manner that leads to such differentiation.

This can lead among certain perennialists to a sort of universalism at times, almost a neo-liberalism occasionally, where all cultures are of value, where all are “interesting,” where all are slightly interchangeable. But given that danger, the advantage for a deeply religious mind of the perennial tradition is to avoid the sectarianism and negative Puritanism which is inevitably part and parcel of building up large religious structures.

As always, a thinker like Evola proceeds from the individual and goes to the individual. This can give thinking of this sort a slightly unreal aspect for many people. Where are the masses? Where is the democratic majority? Where is the BBC vote that decides? The truth is Evola is not concerned with the BBC vote. He’s not concerned with the masses. He regards the masses, and the sort of theorists who go along with him regard the masses, as sacks of potatoes to be moved about. His thinking is completely anti-democratic, Machiavellian to a degree, and even manipulative of the masses as long as it’s down within an order of Tradition within which all have a part.

Evola dates the decline of modernity from, in a sense, the end of the Middle Ages and the beginning of the Renaissance. But many thinkers of a similar sort date the slide at other times. Evola’s a Catholic and once asked about his religious particularism he said, “I’m a Catholic pagan,” which is a deeply truthful remark, dialectically. I am not a Christian, but if you look at it from the outside the core or ur part of Christianity is obviously Roman Catholicism, even though I was technically brought up in the Protestant sort of forcing house of Anglicanism. A wet sheet religion if ever there was one. But Anglicanism, of course, is a syncretic religion. It’s a politically created religion. A bit Catholic, a bit Protestant, but not too much, and with a liberal clerisy at the top that’s partly Protestant-oriented within it and exists to manage the thing.

One of the truthful, although this is en passant, asides that can be made about Anglicanism and the reason why it’s been supported even today through state establishmentarianism when virtually no one attends these churches at all except the odd old lady and immigrants from the Third World, is that it’s a way of damming up some of the extremism that does lurk in religion. Religion is a very dangerous formulation as the modern world is beginning to understand.

I remember Robin Cook, who was a minister who opposed the Iraq War and so on and died on a Scottish mountain, all that obsessive walking when one’s thin and redheaded can lead to undue coronaries, but Cook once said, and he’s a son of the manse like most of these Scottish politicians are, in other words, he comes from a Calvinist background to a degree, he said that in his early life he thought with the general Marxist and Freudian conundrum that religion was over. And now towards the end of his life, this is just before he died, he said, “the dark, clammy, icy hand of religiosity,” in all sorts of systems, “is rising again, and secular Leftists like us,” he’s speaking of himself and those who believe in his viewpoint, “are feeling the winds of this force coming from the side and from behind.” It’s a force that they don’t like.

I remember Robin Cook, who was a minister who opposed the Iraq War and so on and died on a Scottish mountain, all that obsessive walking when one’s thin and redheaded can lead to undue coronaries, but Cook once said, and he’s a son of the manse like most of these Scottish politicians are, in other words, he comes from a Calvinist background to a degree, he said that in his early life he thought with the general Marxist and Freudian conundrum that religion was over. And now towards the end of his life, this is just before he died, he said, “the dark, clammy, icy hand of religiosity,” in all sorts of systems, “is rising again, and secular Leftists like us,” he’s speaking of himself and those who believe in his viewpoint, “are feeling the winds of this force coming from the side and from behind.” It’s a force that they don’t like.

I personally believe, as with Evola, that people are hardwired for faith. Maybe 1 in 10 have no need for it at all. But for most people it’s a requirement. The depth of the belief, the knowledge that goes into the belief, the system they come out of, is slightly incidental. But man needs emotional truths. George Bernard Shaw once said, “The one man with belief is worth 50 men who don’t have any” and it’s quite true that all of the leaders of great movements and those that imposed their will upon [unintelligible] inside and outside of particular countries have considerable and transcendent beliefs, philosophical, quasi-philosophical, religious, semi-religious, philosophical melded into religious and vice versa. Without the belief that there’s something above you and before you and beyond you and behind you that leads to that which is above you, we seem as a species content to slough down into the lowest common denominator, the lowest possible level.

Evola and those who think like him believe that this is the lowest age that mankind has ever experienced, despite its technological abundance, despite its extraordinary array of technological devices that even in an upper pub room in central west London you can see around you. It is also true, and this is one of the complications with these sorts of beliefs, that some of the methodologies that have led to this plasma screen behind me would actually be denied by elements of some of the religiosity that people like him would put forward, but that’s one of the conundrums about epistemology, about what you mean by meaning, which lurks in these types of theories.

The interesting thing about these beliefs is that they are primal. Turn on the television, turn on the radio, the World Cup is just about to begin. Everywhere there is trivia. Everywhere there is celebration of the majority. Everywhere there is celebration of the desire for us all to embrace and become one world, one world together. As someone recently said, “I don’t want to be English. I don’t want to be British. England’s a puddle,” he said. “I want to step out. I want to be a citizen of the world! I don’t want to have a race. I don’t want to have a kind. I don’t want to have a group . . . even a class! I don’t want to come from anywhere. I want to be on this planet! This planet is my home!” Well, my view is that sort of fake universality . . . Maybe you should get him one of these dinky rockets and fire himself off into some other firmament, because this is the home that we have and know. And the only reason that we can define it as such is by virtue of the diversity of what exists upon it. But the number of people who wish to maintain that level of diversity and the pregnant meanings within it seem to get smaller and smaller with each generation.

The politicians that we have now are managers of a social system. It’s quite clear that we do not have three ruling parties, but one party with three wings, the nature of which are interchangeable in relation to gender, where you come from in the country, class, background, how you were educated, and whether you arrived in the country as a newcomer in the last 40 to 50 years or not.

Now, Evola’s step back from what has made the modern world leads to certain radical conclusions about it which are spiritually and politically aristocratic. Most people are only aware of the Left-Right split as it relates to a pre-immigration, slightly organic society where social class was the basis for political alignment. Bourgeois center Right: conservatism of some sort. Center Left: Labour, social-democratic, trade unionist, and so on. Now we have a racial intermingling which complicates even that division. The distinction between the aristocratic and upper class attitude and the bourgeois attitude, which is as pronounced as any Left-Right split between the proletariat and the bourgeoisie, is that which Evola advocates.

Evola believes, in some respects, in masters and slaves, or certainly serfs. He believes that the merchant and those who deal purely with economics have to be subordinated to politics, to higher politics, to metapolitics, to military struggle. He believes that the warrior and the religious leader and the farmer and the intellectual/scholar/craftsman/artist are uniquely superior to those that make money, and nearly all of Evola’s views are in some way a form of aristocraticism.

If you look at all of the sports that he favors–fencing, mountaineering–they all involve lone individuals who prepare themselves for a task which is usually dangerous and which can usually result–mountaineering for example and his book Meditations on the Peaks–in annihilation, if you go wrong, but creates an extraordinary and ecstatic sense of self-overbecoming if you conquer K2, the Peruvian mountains, the Eiger, Mount Everest and so on. Even in the more populist forms of mountaineering, the sort of beard and upper middle class Chris Bonington cheery mountaineering as you might call it, there is a streak of aristocratic, devil may care and Byronic license. The bourgeois view is, “Why do that!? It’s dangerous. It’s pitiless. You could be hurt and injured! There’s no profit. It serves no higher reason than itself.” For Evola, the reason and the purpose is the reason to do it. It is the stages that you go through and the mental states you get into as you prepare and you execute a task which is dangerous and the same analogy can be extended to martial combat, the same analogy can be extended to sports like ancient wrestling.

Modern wrestling is a circus, of course, where the outcome is largely decided by the middlemen who negotiate the bouts between clowns, who can still damage each other very severely. But ancient wrestling was a bout that ended very quickly and was essentially religious, which is why the area that they wrestled in was purified with salt in most of the major traditions.

Fencing: Take away the protective gloves and gear and you have gladiatorial combat between people who are virtually on the brink of life and death. It’s only one step removed from Olympic fencing. Notice that in the contemporary Olympics, a movement that was founded in modernity on the Grecian ideal, nearly always founded by aristocrats, all of the early victors in shooting and fencing and all these early sports are aristocrats. Of course, the early Olympics have their funny side. Many of the female athletes that won the early Olympics were transsexuals. Of course, medical checks were instituted to prevent hermaphrodites and people of diverse genders and that sort of thing from competing in these competitions. But the individualistic sports in a mass age have been disprivileged and are largely regarded as strange wonderland sports that the masses only flip channels over in relation to the Olympics.

For a man like Evola and for the sensibility which he represents, things like sport are not a diversion. They are targets for initiation in relation to processes of understanding about self, the other, and life that transcend the moment. So, one bout leads to another, leads to another moment of skill. It is as if these moments, which most people always try to avoid rather than engage upon, are in slow motion. The whole point of Evola’s attitude toward these and other matters is to go beyond that which exists in a manner which is upwards and transcendent in its portending direction.

This is a society which always looks downwards. “What will other people think? What will one’s neighbors think? What will people out there think? What will all this BBC audience think? What do the masses, Left, Right, Center, pressing their buttons on panels and consoles think?” The sort of Evolian response is what they think is of no importance and they ought to think what the aristocrats of the world, in accordance with the traditions, which are largely religious, out of which their social order comes, think. You can understand that this is an attitude which is not endeared, this type of thinking, to contemporary pundits and to the world as it now is.

It’s also inevitable that when Evola’s books were published they would enter the English-speaking world via the occult, via mysticism, via various types of initiated and individualistic religiosity. The whole point about the Western occult, whether one believes in the literal formulation that these people spout or whether one believes in it metaphorically and quasi-subjectively, is that it’s an individualistic form of religiosity. In simple terms, mass religion involves a small clerisy or priesthood in the old Catholic sense up there and the laity are down there and it’s in Medieval Latin, it’s slightly mysterious, you partly understand it if you’re grammar school educated, otherwise you don’t, it’s mysterious and semi-initiated, but you don’t really know, the mystery is part of the wonder of the thing, you look up at them and they’ve got their backs to you, and they’re looking up further beyond them towards the divine as they perceive it. Now, that’s a traditional form of mass religiosity, if you like.

It’s also inevitable that when Evola’s books were published they would enter the English-speaking world via the occult, via mysticism, via various types of initiated and individualistic religiosity. The whole point about the Western occult, whether one believes in the literal formulation that these people spout or whether one believes in it metaphorically and quasi-subjectively, is that it’s an individualistic form of religiosity. In simple terms, mass religion involves a small clerisy or priesthood in the old Catholic sense up there and the laity are down there and it’s in Medieval Latin, it’s slightly mysterious, you partly understand it if you’re grammar school educated, otherwise you don’t, it’s mysterious and semi-initiated, but you don’t really know, the mystery is part of the wonder of the thing, you look up at them and they’ve got their backs to you, and they’re looking up further beyond them towards the divine as they perceive it. Now, that’s a traditional form of mass religiosity, if you like.

But the type of religiosity with which he was concerned was individualistic and voltaic. It was essentially the idea that everyone in a small group is a priest. Sometimes there’s a priest and a warrior combined. One of the many scandals that we have in modernity is crimes that are committed by members of various religious groups and organizations. Many Traditionalist minded people believe that the reporting of these crimes in the mass media is deliberately exaggerated in order to demonize any retrospectively traditional elements of a prior and metaphysically conservative type in the society.

But if one looks at it another way–and one of the things about Evola is the creativeness of the aristocratic mind that looks at essentially Centrist and bourgeois problems in a completely different perspective–he would say about those sorts of scandals, which I won’t belabor people with because everyone knows about them, that it’s the absence of the dialectic between the priest, somebody who believes in something, somebody who believes in a philosophy that isn’t just theirs and therefore relates to a society and relates to a continuing generic tradition out of which they come . . . Most contemporary philosophers are “just my view.” “Just my view as a tiny little atom.” Rather than my view as something that’s concentric and links me to something larger and that therefore can be socially efficacious. But from an Evolian perspective, the absence of the warrior or the martial and soldierly traditions and its interconnection with belief and the individual who believes is the reason for decadence or deconstruction or devilment or decay in these religious organizations. In his way of looking at things, there’s a seamlessness between the poet-artist, the warrior, and the religious believer. They are different formulations of the same sort of thing, because they are always looking upwards and, in a way, are deeply individualistic and egotistical but transcend that, because the concentration on one’s self or one’s own thinking, one’s own feeling, one’s own concerns, one’s own attitude towards this mountain, this woman, this fight, this text is conditioned by that which you come out of and move towards.

Evola doesn’t believe in progress nor does the Tradition that he comes out of. They don’t believe in scientific progress. They don’t believe in evolution. But his anti-evolutionism is strange and interesting. It’s got nothing to do with creationism and, if you like, the Evangelical politics of certain parts of what you might call the Puritan American Right, for example. His attitude is a reverse attitude, which in a strange way is an involuntary and inegalitarian way of looking at the same issue. His view is that the apes are descended from us as we go upwards rather than we are descended from them as we leave them in their simian animalism. So, in a way, it’s actually a reformulation of the same idea but looking upwards and always seeing, if you like, the snobbish, the aristocratic, the prevailing, the over-arching view rather than viewing the thing from a mass, generic, and middling perspective which includes people.

Tony Blair says the worst vice anyone can have is to be intolerant. It’s to be exclusive. It’s to exclude people. “The nature of Britishness is inclusion,” when, of course, the nature of any group identity is exclusion, and who is on the boundary and who can be allowed in and the subtleties and grains of difference that exist between one excluded group and another, where one tendency of man ends and another begins. Evola believes, in a very controversial way, that decline is morphic and spiritual combined. In other words, races of man have a spiritual dimension, have a higher emotional dimension, have a psychological dimension, but never forget that Evola is not a Nietzschean. He is not somebody who believes that it’s all at this level. He believes that the gods speak to man directly and indirectly and the civilizations that we come out of are based essentially on religious premises.

Moderns who sneer at these sorts of attitudes, of course, forget that virtually every civilization that mankind has ever had until relatively recently, and in every civilization there are documents and artifacts which are included in the storehouse of the British Museum just over there in central London, was religiously and theologically based. It’s only really in a post-Enlightenment, Scottish Enlightenment, English Enlightenment, French Enlightenment, 18th century plus sort of a way that the secularization of Western Europe rivals the rest of the planet. Further east in Europe, less of it. Further south in Europe, a bit less of it. Religiosity on most of the other continents of the Earth is still a primary force, but Evola would despise the sort of religiosity that prevails there because he would see in it broken down thinking, syncretism, the people who would say he would be in favor of contemporary Saudi Arabia, for example, would probably be sorely disappointed. He would see under the religious police, under the strict observance of this or that rule, American satellite dishes and modern devices and that which is external, in relation to modernity, and which is being internally accepted. So, Evola was always the critic, if you like, and always on the outside.

Now, his career is quite complicated because when he was a very young man he fought in the First World War on the Italian side. They, of course, fought on the “Western” or Allied side in that war as is often forgotten. There are some extraordinary photos of him on the internet in these goggles and these helmets looking like extraordinarily fascistic, and that movement hadn’t even really been created then. He looks like that in a D’Annunzian-type way, stylistically, even before the gesture itself.

Evola, of course, partly disapproved of Fascism and National Socialism even though he became very heavily implicated and/or involved in both of them, because in his view they weren’t Right-wing enough! They weren’t traditional enough. They weren’t organic enough. They weren’t extreme enough. Evola is probably the only thinker in the 20th century whose written a slim volume criticizing National Socialism from the Right not from any point to the Left. He only aligned with these movements because they forced modernity to question itself and because they were anti-democratic and because they were ferocious and desired morally and semi-theologically–because few, including liberal critics, would deny that there was a semi-theological insistence to most of the radical European movements, even of the Left but certainly of the Right, in the first half of the last century. Evola saw in these movements a chance but no more, which is why he flirted with them, why he wrote a fascist magazine in Italy, why he went to colleges run by Himmler’s SS in Germany, why he was disapproved of by them, why he had sympathizers in the Ernst Jünger-like in the party who protected him, why he was allowed to write with a degree of freedom whilst giving a degree of loyalist obeisance to these structures and yet, at the same time, to remain outside them. The question has to be raised whether Evola’s philosophy is consonant with the creation of a society or whether it will become, if you like, a spirited individualism.

Evola was also involved in the beginning of his career in one of the most radical modernist movements of the 20th century: Dadaism in Italy. He produced Dadaist paintings. Now, this, superficially, looks quite extraordinary. But of course there was a strong interconnection between certain early modernisms and fascistic ideologies. The reason that he became involved in Dadaism is quite interesting, and, of all things, there is a talk on YouTube that lasts four-and-a-half minutes in which Evola is an old man explicating why he was involved. He says the reason we got involved in these movements was to attack the bourgeoisie, was to attack the middle class, and was to attack middle class sensibility and sentimentality. The extraordinary radical anti-system nature of many radical Right ideas, which is hidden in more moderate and populist variants, comes out staring at you full in the face in people like Evola. Many fascistic and radical movements of the Right, of course, were peopled by adventurers and outsiders and quasi-artists and demi-criminals and religious mystics and madmen and people who were outside of the grain of mainstream life, particularly people who were socialized by the Great War, which many of them experienced as a revolution.

Wyndham Lewis who was strongly drawn aesthetically to modernism and politically to various forms of fascism and was a personal friend of Sir Oswald Moseley once said that for us, the First War was a revolution, wasn’t a war. We saw killing on a truly industrial scale. We saw the industrialization of slaughter.

One of the interesting ironies of the Evolian, and in some ways Ernst Jünger’s, position about war is that, although thinkers like them are regarded by pacifists and liberal humanists and feminists, as warmongers, there is a distaste for mass war in Jünger and Evola and the others, because it’s the war of the ants, the war of the masses in blood and dung and soil and gore. There is nothing chivalric about a man being torn to pieces by a helicopter gunship when he doesn’t even have a chance to get his Armalite into the air.

Evola would prefer the doctrine of the champion. You know, when two Medieval armies meet, and one enormous, hulking man comes out of one army, in full regalia trained in martial splendor and arts as a previous speaker discussed in relation to the Norse tradition, and another champion emerges and they fight for a limited objective that leaves civilization intact on either side. But the one that is defeated will obviously pay dues to the other.

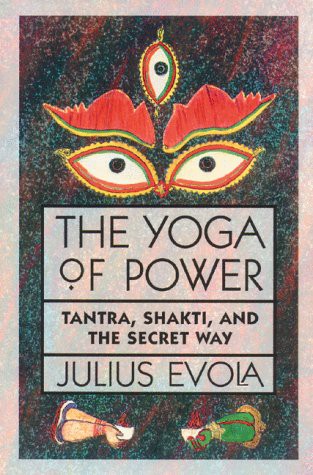

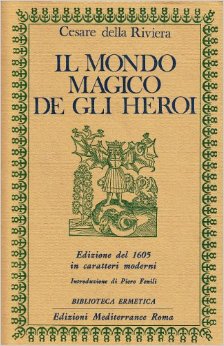

Now, this shows the extremely Byronic, individualistic, and aristocratic spirit that lurks in Evola’s formulations. The way that his works have come down to us, of course, is the way that he lived his life and the books that he wrote. It’s interesting that the Anglo-Saxon world has received his literature through translations by mystic and occultistic publishers in the United States: about tantra, about Buddhism, about Japanese warrior castes and traditions, about the Holy Grail, about Greco-Roman, High Christian, pagan, and post-pagan Europeanist and other traditions.

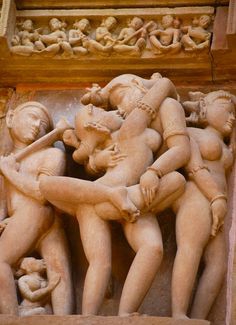

Another radicalism about Evola is his total unstuffiness and absence of prudery in dealings with sex. Evola wrote a book called Metaphysics of Sex. He regards sexuality as a primal biological instantiation through which the races of man are renewed and replaced. But at the same time he regarded it as one of the primary human acts of great energy and force that has to be channeled, has to be made use of, has to be transcended in and of itself. You have this odd commitment to tantra, which is a sort of erotic extremism of occultic sex, and a total opposition to pornography. Why? Because the one involves commercialization of sex, the one involves money interrelated with sexuality. From this purely primal perspective, unless a marriage is arranged between dynastic states or groups for particular statal purposes, which is fine, money has almost nothing to do with these areas of life.

The disprivileging of money as the basis of everything and the belief that the society that we have now is the result of the fact that every politician in all of the parties represented in the major assemblies, including radical Right parties essentially of a populist hue actually, believe in Homo economicus. They believe that man is an economic integer and nothing else matters. Immigration? It’s good for the economy, don’t you know? Mass movements of capital around the world at the flick of a button on a screen in exchanges all around the globe, particularly in the Far East now but also ubiquitously? It’s good for the economy! Everything is based upon the freeing of people from prior forms of alleged servitude due to economic enhancement. The sort of doctrines Evola holds are not neo-Medieval, nor are they a desire for a return to the ancient world with certain modern technologies. In some ways, they are a return to the verities that existed before the modern world was created.

One of the most substantial critiques of this type of thinking is the belief that the modern world is inevitable, that all cultures and races will modernize and are doing so at a great rate of knots, that skyscrapers and enormous megalopolic cities are being thrust up in the Andes and the Far East and even client Chinese-built ones will emerge in Africa and elsewhere and that it would be onwards and upwards forever in relation to what we have now. There are grotesque problems with that, of course, because to give every human on this planet irrespective of race, kinship, clime, and culture a middle American lifestyle you will need 3 planets, 8 planets, 10 planets, or you may need them, in order to give them that middle American feeling. The three satellite dishes, the condominium, the three Chelsea tractors outside in the driveway, the multiple channel TV, and so on. To give every African that we will need many, many planets and many, many times the economic wherewithal that we have even at the moment.

The interesting thing about Evola is that many issues that convulse people today–famine in the Third World, war in the Congo, HIV/AIDS–he would say they’re interesting, of course, because they’re things that are going on, and everything has a meaning even beyond itself. But ultimately they’re unimportant. The number of humans on the Earth doesn’t matter to his type of thinking. Pain and suffering do not matter in accordance with his type of thinking. Indeed, he welcomes them as part of the plenitude of life, because life begins in pain and ends in pain and most people live their entire lives in denial of the fact that life is circular as his philosophical tradition believes the world is and meaning is. There is progression around the circle, but there is decline, and decline and death are part of an endless process of will and becoming.

It is essentially and in a very cardinal way a religious view of life, but also a metaphysically pessimistic and conservative view of life in a profound way that the conservatism of contemporary liberal Tories like Cameron would not even begin to understand. To a man like him, theories of Evola’s sort are lunacy, quite literally, the return to the Dark Ages, the return to the Middle Ages, quasi-justifications of slavery, quasi-justifications of the Waffen SS. This is what Cameron or his colleagues on the front bench and his even more liberal colleagues on the same front bench would say about these sorts of ideas.

But the irony is that 300 to 400 years ago, most civilized structures on Earth were based on these ideas. Even the modern ones that replaced them are based upon the contravention of these sorts of ideas, which means that they realized they were real enough to rebel against in the first instance. It’s also true that even in the high point of modernity, post-modernity, hypermodern reality, all the phrases that are used, when a war occurs, when the planes go into the towers in New York, when the helicopter gunships stream over Arabian sands, you suddenly see a slippage in the liberal verities and in the materialism and in some of the ideas which are used to justify these sorts of things. Not much of a slippage, but you suddenly see a slippage, what occultists and mystics call a “rending of the veil,” a ripping of the veil of illusion between life and death.

But the irony is that 300 to 400 years ago, most civilized structures on Earth were based on these ideas. Even the modern ones that replaced them are based upon the contravention of these sorts of ideas, which means that they realized they were real enough to rebel against in the first instance. It’s also true that even in the high point of modernity, post-modernity, hypermodern reality, all the phrases that are used, when a war occurs, when the planes go into the towers in New York, when the helicopter gunships stream over Arabian sands, you suddenly see a slippage in the liberal verities and in the materialism and in some of the ideas which are used to justify these sorts of things. Not much of a slippage, but you suddenly see a slippage, what occultists and mystics call a “rending of the veil,” a ripping of the veil of illusion between life and death.

What is life really about? Is life really about shopping? Is life really about making more and more money? Is life really about bourgeois status when one already has enough to live on? Is life really about eating yourself to death? These are the sorts of things that Evola’s viewpoint pushes before people, which is why the majority will always push it away.

His political texts are essentially Revolt Against the Modern World, Men Among the Ruins, and Ride the Tiger, which explore the nature of a man who is born now when most of the prior traditions of his culture and his civilization have collapsed. The decivilization of man, the fact that Western cities have turned into Third World zones, the fact that semi-criminality is endemic, the fact that when you go into a street graffiti is there, rap music blares from a passing car, 20%, 40% of the street has no relationship to you aesthetically or ethnically or racially or culturally. Evola would see this as part of the inevitable climate of decline and spiraling downwards towards matter, which is intentional and volitional.

The most controversial area of Evola is when he begins to unpick and reformulate many classic propositionalisms of what might be called the “Old Right” to determine what has occurred and why. Evola is essentially, although he began in a more subjectivist and changeable mood, a deeply religious and aristocratic man. This means there is always a reason. Liberals believe that everything is a confusion and everything is contingent upon itself and everything is an accident waiting to happen. But like Christ in the New Testament, who believes that when two birds fall to the ground the father is aware, Evola believes that there is always a purpose and a reason. Evola believes that civilizations are collapsing in on themselves and tearing themselves apart internally for reasons that are pushed by elites and by forces which are manifest within them that will that desire. The endless atoms and causal moments in the chains may not know of that which is coming, that which is non-volitional, that which is partly pre-programmed. He believes that these tendencies of mass servitude, mass death, mass proletarianization spiritually, mass plebeianism, mass social welfare, mass social democracy are willed, that the destructivity of prior cultural orders is willed and definite, and certain racial groups are used to facilitate that destruction, and that other groups use them in order to achieve it.

He believes in an aristocracy of man, because he believes everything is hierarchical. There was an interesting moment in a by-election in East London or eastern London just recently when the chairman of the party that I used to be in a while ago was asked by a woman of Afro-Caribbean ancestry, “Are we equal with you?” The media’s there, you know. Twenty cameras are upon this individual, and, therefore, given the logic and the paradigm that he is in he said, “Yes.” He would probably want to say, “Yes, but . . . ,” but the media has gone on because it’s got the required answer. Indeed, lots of media investigation now is asking a politician to affirm their correctness before a prior methodological statement, and woe betide any of them if they show the slightest backsliding on any issue about which they should be progressive.

Who can put words in the mouth of somebody who died a while back, but Evola’s answer, the answer of his type of thinking, would be that that woman is unequal in relation to a black writer like Wole Soyinka, who is a Nigerian from the Yoruba tribe and won the Nobel Prize. Is he worthy of winning the Nobel Prize? Was he given the prize in the 1990s because it was fashionable to do? Rabindranath Tagore, the great Indian writer and Brahmin and higher caste type, won it in 1913. Probably wasn’t too much political correctness then, but there was probably a bit even then. The Evolian answer is that she is not equal in relation Soyinka, and Soyinka is not equal in relation to Chaucer or Defoe or Shakespeare or Voltaire or Dante or Tolstoy or Dostoevsky or Wagner, that everything is unequal and that everything is hierarchical and that there is a hierarchy within an individual and between individuals and between groups of individuals, because everything is looking upwards and everything has a different purpose in life.

This means that those who are at the middle and the bottom of an ethnicity, of a social order, of a gender, of a prior historical dispensation should not be lonely, in his way of looking at things, or afraid or rebellious or full of alienation and fear. Because everyone has a role within a hierarchy and people can move to a degree although his viewpoint is essentially aristocratic and not meritocratic. A man like Nietzsche, who Bertrand Russell once condemned as advocating an aristocracy when he was not born in it or anywhere near it, would be accepted, but never completely accepted by an aristocratic caste. Things that are regarded as hopelessly naïve and snobbish now, Evola regards as just due form.

What is the worst thing in the world at the present time according to Sky News? Probably discrimination. Discrimination of one sort or another. Evola would believe that discrimination is the taxonomy of an aristocratic sensibility. One reaches for a piece of cake, one discriminates. One has an arranged marriage with another member of the Sicilian nobility, one discriminates. One reaches for a sword to do down a bounder that one wishes to beat with the flat of the blade, one discriminates between the weapon and the object of the rage, which is itself indifferent because it sees something beyond even itself. These are views, of course, that the majority of people will find cold, chilling, brutal, [unintelligible] beyond their conception. Almost forms of insanity in actual fact in relation to what is today regarded as normal or moral or even human. They are partly inhuman ideas, in some ways, but they are ideas that most aristocracies and most warrior castes have had for most forms of human history.

What is the worst thing in the world at the present time according to Sky News? Probably discrimination. Discrimination of one sort or another. Evola would believe that discrimination is the taxonomy of an aristocratic sensibility. One reaches for a piece of cake, one discriminates. One has an arranged marriage with another member of the Sicilian nobility, one discriminates. One reaches for a sword to do down a bounder that one wishes to beat with the flat of the blade, one discriminates between the weapon and the object of the rage, which is itself indifferent because it sees something beyond even itself. These are views, of course, that the majority of people will find cold, chilling, brutal, [unintelligible] beyond their conception. Almost forms of insanity in actual fact in relation to what is today regarded as normal or moral or even human. They are partly inhuman ideas, in some ways, but they are ideas that most aristocracies and most warrior castes have had for most forms of human history.

Evola’s books are now widely available to those who wish to read them. The great conundrum of his work is, does it portend to an asceticism? In other words, if the era of destruction, which is the Kali Yuga on the ideology which he puts forward, which is the Hindu age of destruction where everything is broken and everything is melded together prior to decomposition which will feed a universal rebirth at a future time, because mankind is seasonal in relation to Spengler’s view of the world where his view of history is compared to plants and botany to give it some sort of methodology, some sort of structure.

Don’t forget, these are 19th century and early 20th century ideas. No history don, or hardly any history don, today believes history has a meaning. Carlyle believed that the sort of deistic nature of history impinged upon the decadence of the French royalist elite and it led to the revolution because they didn’t superintend France properly. He sort of believed in his Protestant, thundering way from the pulpit of his study in the mid-19th century that the French Revolution was an outcome that was partly deserved by a failing aristocracy. In other words, history had a meaning.

It had a purpose. Nobody believes history has a meaning or a purpose. Certain anti-fascists would say Stalingrad had a purpose, but they forget that the Red Army shot 16-18,000 of their own men, and the Commissars stood 18 feet behind the lines. They shot an army of their own men in order to win that battle, just as secret police in the Third World cut off the ears and cut out the tongues of any who retreat in battle before they send them back to their villages.

Would Evola approve of that? He would probably say that if it was done individualistically or as a matter of revenge or of rage it’s dependent upon the circumstances, but to do it in a mass-oriented way–mass camps, mass sirens, the totalitarian response particularly of communism, the reduction of everything to the lowest common denominator so all can be free in a sort of pig-like uniformity–he would consider that really to be death and to be fought against.

Evola is extraordinarily controversial because there is an area in his thinking, particularly in relation to the Islamic world, that leads almost to the justification, as certain liberal critics say, of forms of religious terrorism. He never quite advocates that, but it’s quite clear that his loathing of the modern world is so much and his nuanced appreciation of the Islamic concept of Jihad–where you fight within yourself against doubt and fight externally in a quasi-pagan and masculine way against the enemy that is without you–has a resonance that chimes with certain extremist religious people who basically want to blow the modern world up.

So, Evola is, as I say in my title, one of the world’s most Right-wing, certainly most elitist, thinkers. The interesting thing about him is that everything always looks upwards, even his doctrine of race.

You find in many racialistic movements a sort of socialism. That if you are of my ethnicity you are “all right,” as if possession of a certain melanin skin content or absence of same is all that the thing was about. When Norman Tebbit says that the British National Party is old Labour plus allied racialism, there is always a streak of truth to such viewpoints. Evola doesn’t believe in that.

Evola believes that race is spiritual as well as physical. If a man comes to you and says, “Oh, I’m White! You should be looking after me, mate!” he would say what is your intellect, what is your quality, what is your moral sense, what do you know about your civilization, how far are you prepared to fight for it, what pain can you endure, have you had understanding of death in your family and in life, are you a mature and profound human being or are you part of the limitless universality although you were born in a particular group which I respect and come from myself.? That’s the sort of principle that he would have.

Now, that is an attitude of revolutionary snobbery in a way, but it’s snobbery based upon ideas of character. And in the end as we know, politically, character is a fundamentally important thing. And the absence of it, particularly in quasi-authoritarian movements is poisonous because people once in place cannot be removed except by the most radical of means. So, there is a degree to which leadership is all important.

Look at an army. An army is not a gang of thugs. But it can easily become one. An army can easily become a rabble, but armies are controlled by hierarchies of force, the nature of which is partly impalpable. Each squad has a natural leader. Each squad has its non-commissioned officer. Each squad has an officer above them. In real armies, German, British armies of the past, if one officer goes down somebody replaces them from lower down, assumes immediately the responsibility that goes with that role. Even if all the officers are gone and all non-commissioned officers, the natural leader, one of the 5%–most behavioral anthropologists believe that 1 in 20 of all people have leadership critera–can step forward in a moment of crisis and are looked to by the others, because they provide meaning and order and hierarchy in a moment of stress.

Have you ever noticed that when people undergo disaster or when they’re in difficulties they look for help, but they also look for people to lead them out of it? Leaders are never liked, because it’s sort of lonely at the top, but leadership is probably like the desire to believe in something beyond yourself. It’s inborn. And while the principle of leadership remains, where in even democratic societies leaders are required in order to energize the democratic masses . . .

Don’t forget, most of the Caesarisms of modernity are Red forms of Caesarism, forms of extreme authoritarianism and even pitilessness all in the name of the people. All raised in the name of the masses and their glory and their freedom, their liberty and their equality. When Forbes magazine says that the Castro family’s wealth in communist Cuba is $70 million US dollars, when it calls them communist princes . . . Don’t forget, an ordinary man in Cuba could be in prison for owning his own plumbing business. When you realize that these people are princelings of reversal, you sense that some of the hierarchies, although they wear different names and different forms, are occurring in an entropic phase or in a culture of decay do relate to many of Evola’s ideas even in reversal. He would say this is because these ideas are eternal and are perennial and will out in the end.

The traditional political Right-wing criticism of these sorts of ideas is that they are purely philosophical, they relate to individuals and their lives, they tend to Hermeticism and the ascetic view that a learned spiritual man, a man of some substance, can go off and live by himself and the rest can rot down to nothing and who cares. They say that they feed a sort of post-aristocratic misanthropy.

Look at our own aristocracy. They probably lost power in about 1912. They were never shot like in the Soviet Union, they were never beheaded like in revolutionary France of 200 years before. But they have lost everything in a way because their function has been taken from them, hasn’t it? The reason for those schools, the reason they were bred in the first place, the reason for all their privileges and so on has been taken away. The fascination with the Lord Lucan case in the ’70s, the sort of decline of that class. He listens to Hitler’s speeches at Oxford, beats the nanny to death, not even get the right woman in the basement. This sort of thing. Can’t even get that right! Couldn’t even get the crime right! It’s the decline of a class, isn’t it? Going down, and knowing they’ve gone down as well. It’s sort of Oswald Moseley’s son enjoys being dressed up as a woman and spanked and his son has just died of a heroin overdose. And yet Oswald Moseley is in that family chain. You don’t really need to think that there is a sort of efflorescence there. It’s a bit unfair on that family and so on.

But don’t forget, this was a class that was born to pitilessness and rule. This was a class that identified with eagles. That’s why they put them on their shields and on their ties and on their schools. And now look at them.

But, of course, they have in a sense joined the rest, haven’t they? They’ve joined the mass. And what they once were no longer matters. Cameron sums it up in a strange sort of way. Traditionally, since the 1960s, the Tories have always elected pushy middle class people with which the mass of their electoral support can identify.

It was always said Douglas-Home would be the last of the old breed. He was premier when I was born. He would be the last of the old breed that would survive and thrive. When asked about unemployment in 1961, Douglas-Home said, “There’s room for a second gamekeeper on my estate.” And people said he was out of touch. Out of touch! And he was out of touch! Let’s face it. But he thought that was a quite commodious and moral answer, you see.

Cameron is strange because all of the ease–the ease before the camera, the ease before people, no notes, look at me, not a trembling lip–all of that ease is part of the genetics of what he partly comes out of. And yet all of his values are bourgeois. All of his values are middling and mercantile. All of his values are this society’s as it now is.

Would Douglas-Home have joined or even given money to United Against Fascism, who he would have regarded as smelly little people on the margins of society who were a Left-wing rabble who probably needed to be beating the grass somewhere? Or in my regiment. You see what I mean? The idea that he would identify with these people because the real enemy represents the seeds of the aristocracy from which one has fled, that wouldn’t occur to him. He was too much what he was, basically, as a form to really consider these lies and this legerdemain and this flight of fancy.

One comes to the most controversial area of Evola’s entire prognosis, and this is the belief that Jewishness is responsible for decline and that they are a distant and another race that pushes upon things and causes things to fall and be destroyed. These are the views, of course, the belief that there is a morphic element in the nature of the decline, that has made him so untouchable and controversial. The interesting thing is that when he was approached about the Protocols of the Elders of Zion, which is believed by all liberal humanist scholars to be a forgery of the Okhrana secret police based upon an alleged French novel, I think in the 19th century, Evola said, I’m not concerned whether it’s a forgery or not, which is a very interesting response.

Because in Evola’s occultistic and Hermetic view of the world you can indicate something through its reversal, you can indicate something through metaphorization, something can be emotionally true and not completely factually true, a text can be used to exemplify truths deeper than its own surface. This is a religious view of the text, of course, that the text does not end with itself. It’s a Medieval view and is based upon a science of linguistic study called hermeneutics where you would look at every word, you would look at every paragraph, you would look at every piece of syntax to deconstruct for essence rather than deconstruct to find the absence of essence.

In the Western world, if you go to university now and you do any humanities, any arts, any liberal arts, or any social science course you will come across an ideology called deconstruction. Even vaguely, the semi-educated have heard of it. This is a viewpoint that says that any essentialisms (race, class isn’t an essentialism, but it begins to become one in the minds of man, belief in God, gender and so on) lead to the gates of Auschwitz. This is what deconstruction is based on as a theory. Therefore you look at every text, you look at every film, because they’re obsessed with mass culture, you see, looking at what the masses look at and what they’re fed by the capitalist cultural machine. They look at this and say, oh look, dangerous essentialism there. Did you see in that John Wayne film? Did you see the way he spoke to the Red Indian? Sorry, Native American. You see that sort of thing. You look at these things and you break them down and you break them down again and you break down the element of sort of “David Duke” logic that could be said to lie in that particular phrasing and so on.

But the sort of analysis that Evola maintains is what you might call constructionism rather than deconstructionism. And that’s building upon the essences of things and bringing out their discriminatory differences. So, to him the fact that that text may have been put into circulation by the Okhrana, the czarist secret police, as a profound Hermetic, metaphoricization for courses of history which may or may not be occurring, is worthy of study. He again returns to the idea that everything has meaning.

If you want war with the Islamic world, the towers will fall. If you a pacifist and isolationist America to enter the Great War, a particular boat with civilians onboard but weapons underneath, will be torpedoed by the Germans. If you want to get the isolationist boobs of middle America into a global struggle in the early 1940s you allow the prospect of an attack that you know is going to happen to it there and you make sure your aircraft carriers are not there and you blame the middling officers who were there for their incompetence retrospectively because it is the moment to kick start democratic engagement with heroic and Spartan activities.

Who can doubt that there is a streak of the Spartan? When an American Marine goes up a beach on Iwo Jima or when he fights in Fallujah? Some of the modern world has certainly fallen away for that man as he faces oblivion in warriorship against the other, even within the modern. People like Evola and Jünger would realize that. There’s even at times, in the extremity of modern warfare, a return to the individual. What about these American pilots and these other pilots, these Russian pilots, who fly in these planes, and the warrior is part of the plane. You know, they have a computer in their visor and they have all sorts of statistics coming up before them. It’s like a man who is an army fighting on his own, isn’t it? He’s got an amount of force under his wings which is equivalent to an army of centuries ago. So, you have a return to elite individuals trained only for killing and warriorship at the top tier of present Western advanced military metaphysics.

The interesting thing about Evola’s way of thinking is it’s creative. Most Right-wing people are pessimistic introverts who don’t like the world they were born into, but Evola seems to be to me in some ways an extravagant, optimistic aristocrat who always sees, not the best side of everything, but the most heroic side of everything that goes beyond even itself. Even if the Protocols of the Elders of Zion, in accordance with his diction, was a lie and can be proved to be such, the fact that millions were motivated to believe in it, millions to reject its causation, that people fought out the consequences and the consequences of the consequences in relation to even some of those ideas, means that it is of great specificity and import.

Nietzsche has the idea that a man stands on the edge of a pond, and he skims a pebble into the pond, and it skips across the water. You know when you get it skimming right and it goes and it goes and it goes and wave upon wave moves upon the surface, and you can’t predict the formulation of the wave and the current that it leads into. And that History has unknown consequences.

The Maoist general who was asked by an American sympathizer after the Maoist Long March, itself partly mythological, “What’s your view of the French Revolution?” And he memorably replied, “It’s too early to tell.” Because it’s only two 200 years back. That is the sort of perspective that Evola has.

Although there will be crushing defeats, and men of his sort, aristocrats, for whom the modern world has no time, play polo, waste your money, go to brothels, gamble all the time. There’s no role for you. The world is ruled by machines and money and committees and Barack Obama.

You know, American Rightists call Obama “Obamination” instead of abomination. Is he the signification for everything that is declining in America and isn’t all of these middle class tax revolt type movements which are 100% grassroots American really within the allowed channels of opposition? “He’s a socialist!” “It’s all about tax. It’s not about anything else.” “It’s all within the remit of health care budgetary constraints and views on same.” Etc, etc. “What about the deficit?” Aren’t all of these movements and the rage that they contain elements and spectrums of what he would call anti-modernity or semi-anti-modernity within modernity?

None of us know what the future will hold, but it is quite clear that unless people of advanced type in our group believe in some of the traditions that they come out of again, they will disappear. And in Evola’s view they will have deserved to disappear. So, my view is that whatever one’s view, whatever one’s system of faith . . . and don’t forget that in the Greek world you could disbelieve in the gods and think they were metaphors, you could kneel before a statue of them or you could have a philosophical belief in between the two and all were part of the same culture, all were part of the same city-state, and if called upon as a free citizens to defend it, even Socrates would stand in line with his shield and his spear.

All of Evola’s books are now available on the internet. The most controversial passages about morphology and ethnicity are all available on the internet. Read Julius Evola. Read an aristocrat for the past and the future, and look back to the perennial Traditions that are part and parcel of Western civilization and can fuel the imagination and fire even in those who don’t entirely believe in them.

Thank you very much!

Respectivement consacrés à Renzo de Felice et Giorgio Locchi, les chapitres 1 et 6 de la première partie posent les questions les plus fondamentales pour notre famille de pensée. Jusqu’où faire remonter la recherche de notre « moment zéro » (François Bousquet) ? Les étapes de la « tendance époquale » surhumaniste se succèdent-elles de manière continue ? Le fascisme lato sensu (dont le national-socialisme est provisoirement la forme la plus achevée) a-t-il été « prématuré (p. 142) », comme le laissent supposer certains passagers de Nietzsche prophétisant un interrègne nihiliste de deux siècles ?

Respectivement consacrés à Renzo de Felice et Giorgio Locchi, les chapitres 1 et 6 de la première partie posent les questions les plus fondamentales pour notre famille de pensée. Jusqu’où faire remonter la recherche de notre « moment zéro » (François Bousquet) ? Les étapes de la « tendance époquale » surhumaniste se succèdent-elles de manière continue ? Le fascisme lato sensu (dont le national-socialisme est provisoirement la forme la plus achevée) a-t-il été « prématuré (p. 142) », comme le laissent supposer certains passagers de Nietzsche prophétisant un interrègne nihiliste de deux siècles ?

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

Rispetto all’interesse evoliano per il dato esoterico-politico nell’Alighieri, è opportuno ricordare che la cerca del Poeta è sintonica, e la cosa è accortamente rilevata da Consolato, a quella che maturò negli ambienti graalici in rapporto al problema dell’Impero. Caratterizzata, in particolare, dal continuo riferirsi al motivo dell’imperatore latente, mai morto e per questo atteso e al Regno isterilito, simbolizzato in modo paradigmatico dall’Albero secco che rinverdirà con il rimanifestarsi nella storia dell’Impero, per l’azione del Veltro-Dux. L’Impero, per esser tale, deve far riferimento ad un re-sacerdote il cui modello è Melchisedec, custode della funzione attiva e di quella contemplativa. L’autore suggerisce che in tema di Veltro e relativamente alla sua esegesi storico-politica, Evola si richiama alla lezione di Alfred Bassermann, grazie alla quale egli coglie come Dante, in tema, si sia fermato a metà strada, “la sua concezione dei rapporti tra Chiesa e Impero rimase imperniata su di un dualismo limitatore…tra vita contemplativa e vita attiva” (p. 39). Lo stesso esoterismo dell’Alighieri era legato ad una sorta di via iniziatica platonizzante, non pienamente giunta a rilevare, come accadrà nel puro templarismo, che l’iniziazione regale risolve in sé i due momenti del Principio, contemplazione ed azione. In questo contesto, suggerisce Consolato, deve essere letta la polemica di Cecco d’Ascoli nei confronti dell’Alighieri, attaccato in quanto “deviazionista” rispetto all’iniziazione propriamente regale. In questi termini, Dante è il simbolo più proprio, per Evola, dell’età in cui visse, il

Rispetto all’interesse evoliano per il dato esoterico-politico nell’Alighieri, è opportuno ricordare che la cerca del Poeta è sintonica, e la cosa è accortamente rilevata da Consolato, a quella che maturò negli ambienti graalici in rapporto al problema dell’Impero. Caratterizzata, in particolare, dal continuo riferirsi al motivo dell’imperatore latente, mai morto e per questo atteso e al Regno isterilito, simbolizzato in modo paradigmatico dall’Albero secco che rinverdirà con il rimanifestarsi nella storia dell’Impero, per l’azione del Veltro-Dux. L’Impero, per esser tale, deve far riferimento ad un re-sacerdote il cui modello è Melchisedec, custode della funzione attiva e di quella contemplativa. L’autore suggerisce che in tema di Veltro e relativamente alla sua esegesi storico-politica, Evola si richiama alla lezione di Alfred Bassermann, grazie alla quale egli coglie come Dante, in tema, si sia fermato a metà strada, “la sua concezione dei rapporti tra Chiesa e Impero rimase imperniata su di un dualismo limitatore…tra vita contemplativa e vita attiva” (p. 39). Lo stesso esoterismo dell’Alighieri era legato ad una sorta di via iniziatica platonizzante, non pienamente giunta a rilevare, come accadrà nel puro templarismo, che l’iniziazione regale risolve in sé i due momenti del Principio, contemplazione ed azione. In questo contesto, suggerisce Consolato, deve essere letta la polemica di Cecco d’Ascoli nei confronti dell’Alighieri, attaccato in quanto “deviazionista” rispetto all’iniziazione propriamente regale. In questi termini, Dante è il simbolo più proprio, per Evola, dell’età in cui visse, il  Le penseur français René Guénon (1886 – 1957) ne suscite que très rarement l’intérêt de l’université hexagonale. On doit par conséquent se réjouir de la sortie de René Guénon. Une politique de l’esprit par David Bisson. À l’origine travail universitaire, cet ouvrage a été entièrement retravaillé par l’auteur pour des raisons d’attraction éditoriale évidente. C’est une belle réussite aidée par une prose limpide et captivante.

Le penseur français René Guénon (1886 – 1957) ne suscite que très rarement l’intérêt de l’université hexagonale. On doit par conséquent se réjouir de la sortie de René Guénon. Une politique de l’esprit par David Bisson. À l’origine travail universitaire, cet ouvrage a été entièrement retravaillé par l’auteur pour des raisons d’attraction éditoriale évidente. C’est une belle réussite aidée par une prose limpide et captivante. Au cours de l’Entre-deux-guerres, le futur historien des religions affine sa propre vision du monde. Alimentant sa réflexion d’une immense curiosité pluridisciplinaire, il a lu – impressionné – les écrits de Guénon. D’abord rétif à tout militantisme politique, Eliade se résout sous la pression de ses amis et de son épouse à participer au mouvement politico-mystique de Corneliu Codreanu. Il y devient alors une des principales figures intellectuelles et y rencontre un nommé Cioran. Au sein de cet ordre politico-mystique, Eliade propose un « nationalisme archaïque (p. 252) » qui assigne à la Roumanie une vocation exceptionnelle. Son engagement dans la Garde de Fer ne l’empêche pas de mener une carrière de diplomate qui se déroule en Grande-Bretagne, au Portugal et en Allemagne. Son attrait pour les « mentalités primitives » et les sociétés traditionnelles pendant la Seconde Guerre mondiale s’accroît si bien qu’exilé en France après 1945, il jette les premières bases de l’histoire des religions qui le feront bientôt devenir l’universitaire célèbre de Chicago. Si Eliade s’éloigne de Guénon et ne le cite jamais, David Bisson signale cependant qu’il lui expédie ses premiers ouvrages. En retour, ils font l’objet de comptes-rendus précis. Bisson peint finalement le portrait d’un Mircea Eliade louvoyant, désireux de faire connaître et de pérenniser son œuvre.

Au cours de l’Entre-deux-guerres, le futur historien des religions affine sa propre vision du monde. Alimentant sa réflexion d’une immense curiosité pluridisciplinaire, il a lu – impressionné – les écrits de Guénon. D’abord rétif à tout militantisme politique, Eliade se résout sous la pression de ses amis et de son épouse à participer au mouvement politico-mystique de Corneliu Codreanu. Il y devient alors une des principales figures intellectuelles et y rencontre un nommé Cioran. Au sein de cet ordre politico-mystique, Eliade propose un « nationalisme archaïque (p. 252) » qui assigne à la Roumanie une vocation exceptionnelle. Son engagement dans la Garde de Fer ne l’empêche pas de mener une carrière de diplomate qui se déroule en Grande-Bretagne, au Portugal et en Allemagne. Son attrait pour les « mentalités primitives » et les sociétés traditionnelles pendant la Seconde Guerre mondiale s’accroît si bien qu’exilé en France après 1945, il jette les premières bases de l’histoire des religions qui le feront bientôt devenir l’universitaire célèbre de Chicago. Si Eliade s’éloigne de Guénon et ne le cite jamais, David Bisson signale cependant qu’il lui expédie ses premiers ouvrages. En retour, ils font l’objet de comptes-rendus précis. Bisson peint finalement le portrait d’un Mircea Eliade louvoyant, désireux de faire connaître et de pérenniser son œuvre. En étroite correspondance épistolaire avec Guénon, Schuon devient son « fils spirituel ». cela lui permet de recruter de nouveaux membres pour sa confrérie soufie qu’il développe en Europe. D’abord favorable à son islamisation, Schuon devient ensuite plus nuancé, « la forme islamique ne contrevenant, en aucune manière, à la dimension chrétienne de l’Europe. Il essaiera même de fondre les deux perspectives dans une approche universaliste dont l’ésotérisme sera le vecteur (p. 172) ». Cette démarche syncrétiste s’appuie dès l’origine sur son nom musulman signifiant « Jésus, Lumière de la Tradition».

En étroite correspondance épistolaire avec Guénon, Schuon devient son « fils spirituel ». cela lui permet de recruter de nouveaux membres pour sa confrérie soufie qu’il développe en Europe. D’abord favorable à son islamisation, Schuon devient ensuite plus nuancé, « la forme islamique ne contrevenant, en aucune manière, à la dimension chrétienne de l’Europe. Il essaiera même de fondre les deux perspectives dans une approche universaliste dont l’ésotérisme sera le vecteur (p. 172) ». Cette démarche syncrétiste s’appuie dès l’origine sur son nom musulman signifiant « Jésus, Lumière de la Tradition». Mais qu’est-ce que la multipolarité ? Pour Alexandre Douguine, ce phénomène « procède d’un constat : l’inégalité fondamentale entre les États-nations dans le monde moderne, que chacun peut observer empiriquement. En outre, structurellement, cette inégalité est telle que les puissances de deuxième ou de troisième rang ne sont pas en mesure de défendre leur souveraineté face à un défi de la puissance hégémonique, quelle que soit l’alliance de circonstance que l’on envisage. Ce qui signifie que cette souveraineté est aujourd’hui une fiction juridique (pp. 8 – 9) ». « La multipolarité sous-tend seulement l’affirmation que, dans le processus actuel de mondialisation, le centre incontesté, le noyau du monde moderne (les États-Unis, l’Europe et plus largement le monde occidental) est confronté à de nouveaux concurrents, certains pouvant être prospères voire émerger comme puissances régionales et blocs de pouvoir. On pourrait définir ces derniers comme des “ puissances de second rang ”. En comparant les potentiels respectifs des États-Unis et de l’Europe, d’une part, et ceux des nouvelles puissances montantes (la Chine, l’Inde, la Russie, l’Amérique latine, etc.), d’autre part, de plus en plus nombreux sont ceux qui sont convaincus que la supériorité traditionnelle de l’Occident est toute relative, et qu’il y a lieu de s’interroger sur la logique des processus qui déterminent l’architecture globale des forces à l’échelle planétaire – politique, économie, énergie, démographie, culture, etc. (p. 5) ». Elle « implique l’existence de centres de prise de décision à un niveau relativement élevé (sans toutefois en arriver au cas extrême d’un centre unique, comme c’est aujourd’hui le cas dans les conditions du monde unipolaire). Le système multipolaire postule également la préservation et le renforcement des particularités culturelles de chaque civilisation, ces dernières ne devant pas se dissoudre dans une multiplicité cosmopolite unique (p. 17) ». Le philosophe russe s’inspire de certaines thèses de l’universitaire réaliste étatsunien, Samuel Huntington. Tout en déplorant les visées atlantistes et occidentalistes, l’eurasiste russe salue l’« intuition de Huntington qui, en passant des États-nations aux civilisations, induit un changement qualitatif dans la définition de l’identité des acteurs du nouvel ordre mondial (p. 96) ».