“No illusions, gentlemen, no illusions!”

—Tsar Alexander II Romanov, addressing his Polish subjects

The recent Polish parliamentary elections of 2015 can be seen as a part of a broader European trend, but nevertheless they must be seen first in the Polish context which I will try to briefly outline for Counter-Currents readers. Some of this information will seem peculiar for American or Western readers, but I am sure that people from other Eastern bloc countries will more than once nod their heads in understanding.

The Polish Political Scene after 1989

From the perspective of party politics, the Polish political scene is rather unstable. Parties come and go, change names, form and reform different coalitions. However, most people active in politics are professional politicians, who change parties and views but remain present in the scene.

The current Polish political scene has been shaped by two important events: first and foremost was the collapse of the Communist system in 1989, and the second was the crash of the presidential Tupolev airplane in 2010.

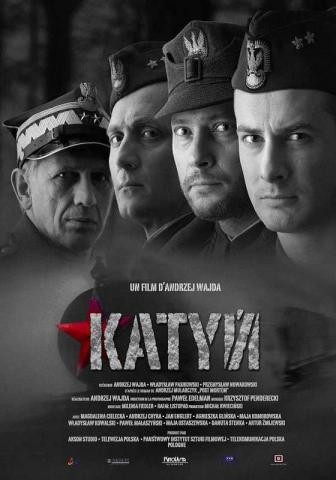

Up to 1989, the Soviet-dominated Polish Republic of Poland (Polska Rzeczpospolita Ludowa) was ruled by the Communist party, which (in line with Stalin’s Second World War quasi-nationalist politics) was not named a Communist, but Polish United Workers’ Party (Polska Zjednoczona Partia Robotnicza). There have been minor other parties – the official opposition, which took part in the elections and even had representatives in the Parliament. Although they have played some role in shaping the Polish intelligentsia, they were otherwise powerless and unimportant. The majority of Poles were not Communists, and the Soviets as well as their local supporters implemented violent policies of “communization” in Poland, starting with the massacre of Polish officers in Katyń and then brutal suppression of all social unrest and political dissent.

In 1980 a new movement arose: Solidarność (Solidarity) founded by striking workers, who united with the intelligentsia and forced (through strikes and negotiations) the legalization of the movement. In 1981 Solidarity had its spine broken. General Wojciech Jaruzelski, then First Secretary of the Communist party (the de facto ruler of Poland), proclaimed martial law and jailed Solidarity leaders.

However, Poland faced one of its worst economic crises in the 1980s, and at the end of the decade, the Communists decided to start negotiations with opposition leaders in order to force them to accept some of the responsibility for the course of events. These so-called Round Table Talks in 1989 lead to the first parliamentary elections in which members of non-official parties could take part.

These elections were a total disaster for the Communists: even members of the army, the militia, and the Communist Party itself voted for opposition representatives. Thus, Communists had to share power with the opposition. The more liberal Communists struck unofficial deals with more liberal opposition members. Poland underwent a transition from a Communist to a liberal democratic country, but members of the Communist party or the special services were (mostly) not deprived of their assets. The Communist party was dissolved, but Communists became Social Democrats or went into business and remain active even now.

Solidarity was never a monolith. It began as a movement of liberal reform within socialism but ended up as an anti-Communist movement. The two most important wings of Solidarity can be called, for the sake of simplicity, “liberals” and “conservatives.” The liberals advocated neoliberal economics combined with secular values. They wanted a Poland which would have close ties with Western Europe and would not take revenge on the overthrown Communists. The conservatives advocated a statist economy combined with Christian values. They wanted a Poland with close ties to the United States and a lustration of the Communists. The third political power were the post-communists: Social Democrats. Their main constituency were people connected with the previous system: former soldiers, militiamen, secret police agents, and party officials. Interestingly, it was the Social Democrats – once they seized power again – who made Poland a member of NATO and the European Union and who have supported Polish engagement in wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. In short, the post-Communists always envisioned Poland as a state subject to a greater power, whether it was the Soviet Union or the victors of the Cold War.

After many changes and conflicts in the political scene, the two currently most important Polish parties emerged: Platforma Obywatelska (PO)/Civic Platform and Prawo i Sprawiedliwość (PiS)/Law and Justice. Civic Platform is the embodiment of the liberal tendencies and Law and Justice of the conservative tendencies in the post-Solidarity movements. Law and Justice seized power for a short time in 2005, but it lost in the earlier elections in 2005 to Civic Platform. And then came the disaster which has shaken the Polish political scene.

On April 10th, 2010, the presidential Tupolev airplane crashed near Smoleńsk in Russia during an official trip to a ceremony of commemoration for the Polish officers murdered in Katyń by the Soviets. Everybody on board died. The victims included president Lech Kaczyński (of the Law and Justice party, twin brother of the party’s leader, Jarosław Kaczyński) and the first lady, all of the military chiefs of staff, the national bank governor, all the head army chaplains, and over 90 important political figures. This caused a major split in Polish politics.

Jarosław Kaczyński and Law and Justice accused Civic Platform and their leader and then Prime Minister Donald Tusk of treason. They claimed that Civic Platform officials organized the presidential visit in a way that led to the disaster. The more radical factions started to claim that Civic Platform are Russian puppets, and the disaster was actually an assassination organized by Putin and Tusk. Civic Platform, on the other hand, claimed that Kaczyński and Law and Justice are crazies who believe in conspiracy theories and will start a war with Russia once they seize power. Thus began an endless fight over the Smoleńsk disaster. The Left, the nationalists, and libertarians tried to break through this dualist narrative, but the media have followed either of the two narratives, and the public followed the media. Law and Justice began losing elections, both presidential and parliamentary.

Civic Platform seized full power. They claimed to be a modernizing force that will turn Poland into a prosperous economy modeled on Western European countries, fully integrated with the European Union. They presented themselves as the enlightened liberal elite, which will end all politics and finally make Polish society as well-functioning as the idealized West. The entire mainstream media went into full support mode, on the one hand praising the government, on the other condemning Law and Justice as evil forces of reaction.

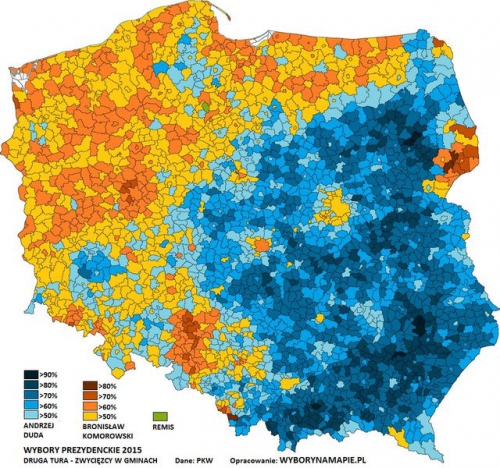

At the end of 8 years of Civic Platform rule, Poles started to grow disillusioned with the party. The local elections of 2014 were a tie between Civic Platform and Law and Justice. The presidential elections of 2015 were a major surprise. The ruling president Bronisław Komorowski of Civic Platform was expected to win in the first round by gaining more than 50% of the vote. All the major media and polls predicted such a result. However, the young and previously unknown candidate of Law and Justice, Andrzej Duda, narrowly won the first round. In the second round, Andrzej Duda won again, thus becoming the new Polish President. It then became clear that Civic Platform was on its way to a massive defeat.

The 2015 Elections: Victors and Losers

There are five points that need to be made clear about the Polish parliamentary system.

- First, Poland is a unitary republic, in which Parliament is the legislature, and the President and Council of Ministers are the executive. However, in reality, the Prime Minister has the most power, and the President mostly represents the state in international affairs (although he can also propose his legal projects to the Parliament and can veto any legislation of the Parliament, except for the budget, but the Parliament can override presidential vetoes by a 3/5 majority). Thus, it is the Prime Minister who is the most important figure in Poland, and Parliamentary elections are the most important ones.

- Second, the Parliament consists of two houses: the Sejm and the Senat. The Sejm is the main force which decides on the legislature, and the Senat can veto or change the legislation of the Sejm.

- Third, Poland has an electoral system of proportional representation in Sejm elections and single-member districts for the Senat.

- Fourth, political parties in Poland are financed by the state.

- Fifth, there are three different electoral thresholds. If a party gets 3% of votes, all their campaign expenses are paid by the state budget. If a party gets 5%, they enter the Sejm. If a coalition of parties gets 8%, they enter the Sejm.

The main winner of the 2015 Parliamentary elections is Law and Justice (Prawo i Sprawiedliwość or PiS). They got 37.58% of votes, thus winning 235 seats in the Sejm. This is the largest victory ever in Polish elections. PiS can now form an autonomous government, and they do not need to enter coalition to rule.

The main loser is Civic Platform (Platorma Obywatelska or PO). They got 24.09% of vote, winning 138 seats, thus losing power and becoming the main opposition party.

The third place is surprisingly one of the victors: the electoral committee Kukiz’15 got 8.81% of the vote, winning 42 seats. It is a populist coalition lead by Paweł Kukiz, a rock musician (former member of the famous-in-Poland band Piersi – The Breasts [sic!]). Kukiz has more or less always been involved in politics. He supported the anti-Communist opposition, then he criticized and mocked the post-Communist Left, the conservative wing of post-Solidarity movement, and the populist parties. Kukiz has supported the liberal center parties, including the Civic Platform. However, once he became disillusioned with their ruling strategy he went into “angry white man” mode. He formed a social movement aiming at changing the Polish constitution and introducing a single-member districts electoral system (modeled on the US, French, and UK systems) in Poland, which he believes will break the system. In reality, it will only strengthen the system and prevent nationalists and populists from entering the Parliament. Paweł Kukiz took part in the Presidential elections in 2015 and surprisingly got the third place in the first round with 20.80% of votes. He is a populist, highly patriotic, and supports popular Catholicism. However, his coalition is a mix of everything: supporters of marijuana legalization, nationalists, local activists, libertarians, a hip-hop star, a hero of the radical anti-Communist opposition, a university professor etc. They were the only participants in the election who did not have an official agenda (!). They appeal mostly to the young generation and Polish emigrants living abroad.

In fourth place was the .Nowoczesna (.Modern) party of Ryszard Petru which got 7.6% of votes, thus winning 28 seats. This is the resurrected liberal wing of post-Solidarity politics, basically a more liberal and less corrupt Civic Platform for the young middle class. Ryszard Petru presents himself as an outsider, but he has been present in the second and third rank of Polish politics on the side of the liberals for a long time. He is widely perceived as a representative of banskters and international corporations who is going to secure their interests under liberal slogans.

In fifth place are the biggest losers: the Zjednoczona Lewica (United Left) coalition, which got 7.55% of vote. However they did not pass the 8% threshold for coalitions, thus they did not get any seats.

The main member of this coalition is the Sojusz Lewicy Demokratycznej (Democratic Left Alliance) which is basically the post-Communist party. Ironically, they have always been the main supporters of total alliance with Western powers and were as eager to support the neocon imperialist policies of the US as they were in supporting the imperialist policies of USSR. Also, they have always been friends with big business, including supporting low taxes, which did not prevent them from officially adopting the typical social democratic agenda.

The other important member of the coalition was the party of Janusz Palikot, a philosopher turned businessman turned politician, who made big money on strange privatization deals and creative tax evasion. He used to support the conservative wing of Civic Platform, and was even a promoter of Catholic business ethics, the founder of the conservative magazine Ozon, and the publisher of the Polish edition of Ernst Jünger’s Der Arbeiter. But he turned into a full-scale aggressive Leftist, gaining support from LGBT advocates, anticlerical circles, etc.

This is the first time the Left did not get any seats in the Polish parliament. The two main constituencies of the Left were always the old Communist supporters (the so-called “orphans of the People’s Republic”) and the youngest generation of voters. However, the old Communists just keep dying out (biology is cruel) and the youngest generation either hates the post-Communists and votes for the populists such as Kukiz, or dislikes the post-Communists and votes for the Razem party.

In sixth place was the Polskie Stronnictwo Ludowe: PSL (Polish People’s Party) with 5.13% of votes and 16 seats. It is an officially agrarian party which has been present in Polish politics since the early 20th century, arising from the Polish agrarian movement. However the contemporary PSL doesn’t have much to do with its previous incarnations. Once communists seized power in Poland after the Second World War, they murdered, jailed, or exiled the patriotic members of PSL and created a new one, which became a part of the so-called “official opposition.” It survived the collapse of the system in 1989 and was a member of almost every ruling coalition. The PSL does not have a real agenda. Their aim is to get as much power as possible by supporting the ruling party in exchange for getting as many of their people employed in various ministries, agencies, and offices of the Polish state. It is the largest party in Poland (in terms of membership) and generally considered to be the most greedy and corrupt.

In seventh place is another big loser: the KORWIN party with 4.76% of the vote and 0 seats. This is a Polish version of the Libertarian party lead by Janusz Korwin-Mikke, who might be considered the most controversial figure of Polish politics. He is hyper-intelligent and hyper-eccentric, and promotes hardcore libertarian, minarchist economic policies combined with traditional Christian values. He has lots of children, even with young female supporters (his wife doesn’t mind), has a very strange manner of speaking (many Poles literally do not understand what he is saying), often mentions Hitler in his speeches (“Even Hitler promoted lower taxes!”), insults his opponents and journalists, etc. The public considers him a kook, but he has a die-hard constituency among young male students.

Janusz Korwin-Mikke was a member of the Sejm in the early 1990s, but he lost every election ever since. He won a seat in the European Parliament in 2014 under the slogan that he will “burst the system from inside,” but since then he has been caught sleeping in parliament, slapping one of his former colleagues, and making speeches about the “niggers of Europe” (referring to young people exploited by the EU) and “human trash” (referring to Muslim immigrants). He was expected to make a comeback in Polish politics, but to his own surprise he lost terribly.

In eighth place is the Leftist Razem (Together) party with 3.62% votes and 0 seats. Yet they are considered one of the main victors of the elections! It is a young grassroots party with no professional politicians but many local activists. They refused to join the United Left coalition and were mocked as the “Facebook party” or “hipster Left.” In reply, they mocked the post-Communists as fake Leftists and generally were quite nice people during the campaign (lots of direct communication with young voters, not insulting their opponents etc.). This “nice, young, idealist guy” strategy was quite successful as they have passed the 3% threshold and will now enter the state-funded party system, and they are expected to take the place of post-Communists in the next elections.

The Winning Strategy . . .

The main victor is, of course, the Law and Justice party. They are a great example of breaking through a seemingly hopeless situation. Civic Platform had all power, full mainstream media support, and broad social support. They successfully created a narrative according to which they were the forces of modernization, the only party able to turn Poland into a prosperous and respected country. On the other hand, they presented Law and Justice as crazy kooks who would blow everything up and ruin things for everyone. Civic Platform also presented their time in power as the period of Poland’s greatest prosperity, with the construction of highways, roads, stadiums, and great international investments in the country.

Law and Justice seemed to be banished from the mainstream forever. However, they started creating their own channels of information: they revived small conservative newspapers, founded new magazines, created internet TV and YouTube channels, Facebook profiles, etc. Most importantly, these were not directly linked to the party but to so-called “independent” journalists with clear conservative tendencies. Every time there was a breach in the mainstream narrative, any time an actor, a performer, a journalist, or a writer has voiced a pro-Law and Justice opinion, he or she would immediately become a star of this alternative, conservative media.

These media outlets began, of course, with crazy conspiracies about the Smoleńsk disaster. But with time they changed their strategy. They started showing the mistakes and plot-holes of the lengthy Russian and Polish investigations of the disaster. They blew the whistle every time there was an instance of corruption in the ruling party. They have emphasized every instance of hatred towards traditional Polish society among the mainstream media. They started presenting Civic Platform’s “modernized Poland” as a lie. In reality Poland was becoming a neocolony of the West, from which only the politicians of the ruling parties can profit.

Eventually the biggest ally of this anti-governement narrative turned out to be the government itself. Yes, there were new stadiums built for the EURO 2012 championship. But the construction was faulty, and they soon began to generate financial losses for the municipalities. Yes, there were new highways. But they turned out to be some of the most expensive roads in the world, and the companies that built them often were not paid and went bankrupt. Yes, there were new jobs in Poland. But the country has become one of the centers of inter-Western outsourcing with highly qualified but low-paid workers.

The government aimed to hide or falsify official economic statistics, but once they saw the light of day, the numbers began to support the anti-government narrative. Many people actually stopped reading the newspapers and watching television and switched to Internet as a means of obtaining information. One of the last nails in the government’s coffin was a report on the state-funded retirement system that was sent to everyone right before the elections. The prognosis was shockingly low (mine was about 30 euros per month) and made people even more discontent.

It was especially the young generation that finally drew the line. They were promised prosperity and great opportunities, but they never saw any of that. Most of them are unemployed or employed on short-time contracts (and thus they are not subject of the quite good and just Polish work legislation). They live with their parents and see no hope for change. They did not vote for Law and Justice because they love Jarosław Kaczyński and his allies, but because they hate the government. They do not believe in the Smoleńsk disaster conspiracy, and in this case they often agree with the mainstream liberal views. Let me quote one of the young voters: “Fuck Smoleńsk! And fuck the government! I want a real job, and I want to sleep with my girlfriend, not my mum!”

It was especially the young generation that finally drew the line. They were promised prosperity and great opportunities, but they never saw any of that. Most of them are unemployed or employed on short-time contracts (and thus they are not subject of the quite good and just Polish work legislation). They live with their parents and see no hope for change. They did not vote for Law and Justice because they love Jarosław Kaczyński and his allies, but because they hate the government. They do not believe in the Smoleńsk disaster conspiracy, and in this case they often agree with the mainstream liberal views. Let me quote one of the young voters: “Fuck Smoleńsk! And fuck the government! I want a real job, and I want to sleep with my girlfriend, not my mum!”

Jarosław Kaczyński has also adopted a good strategy of hiding the more radical politicians of his party from the media (including himself!) and putting younger and more liberal activists in the spotlight. Also, he has made Beata Szydło, a rather un-charismatic, but in a way nice female party member, candidate for the Prime Minister if Law and Justice wins the elections.

Another good strategy was adopted by the Populists led by Paweł Kukiz. They decided built a wide coalition of the discontented around a simple slogan. Their main slogan at first was to change Polish electoral system to single-member districts (in Polish: Jednomandatowe Okręgi Wyborcze, acronym: JOW), but after Paweł Kukiz was third in the presidential elections, it turned out that most of his supporters didn’t even know what “JOW” meant, and they did not care. In fact, many of his supporters were against the introduction of the single-member districts. Then, the populists adopted a slightly different approach. First, the acronym JOW was given a new, unofficial meaning: “Jebać Obecną Władzę!” (“Fuck the Current Government!”). Secondly, Paweł Kukiz changed his greatest weakness into his greatest strength. His coalition was accused of being a bunch of odd fellows with no coherent agenda. And the populists’ response was: “Hell yes, we are a bunch of odd fellows! And we will never have an official agenda, which nobody, including politicians themselves, gives a damn about anyway. But we will enter politics, and we will smash the system.” They focused on stirring discontent and promoting strong anti-system and pro-nation slogans. Paweł Kukiz has also promoted his coalition as the only real alternative to corrupt parties, all of which have at once ruled the country, and none of them turned out to be effective.

. . . and the Losing Strategy

Why did Civic Platform lose the elections? There are two main reasons: corruption and arrogance. One has to admit that they used to seem like a decent, typically Western centrist party. But once they seized full power, they lost contact with reality. It seems that they really started to believe what the mainstream journalists told them. As some insiders claim, many of the top politicians truly believed that they would never lose power. The other reason was corruption. They quickly began to create countless new government jobs and hired people from the party as well as family members. This is nothing new in Polish politics, but this time the scale was enormous.

The public discontent grew, and when then Prime Minister and head of Civic Platform, Donald Tusk, was promoted to the rank of the President of the European Council (as with most EU ranks and offices, the office has not real impact on actual events, but comes with great assets) in December 2014, the government and the mainstream media proclaimed it a great victory, but much of the public saw it as the biggest rat leaving a sinking ship. Donald Tusk left Polish affairs in the hands of the previous Minister of Health Affairs, the utterly incompetent Ewa Kopacz, who became the new Prime Minister and head of the ruling party.

Also, by the end of their second term some of the top officials were secretly recorded by waiters in a Warsaw restaurant, and the recordings were leaked to the press. The recorded officials openly discussed corruption, fake deals, the tragic state of the republic, and party infighting using very vulgar language. As it also turns out from the recordings, many of them are not as intelligent as many believed. The fact that they discussed these matters over meals which cost more than what an average young worker made in a week did not help either. Once the party officials and their fellow journalists began to proclaim that their candidate, then President Bronisław Komorski, would surely win in the first round, the voters gave a big middle finger to the government by supporting either opposition-backed Andrzej Duda or the independent populist Paweł Kukiz. And it all went downhill from there.

The Meaning of the Elections for Poland and Europe

The 2015 elections are often being compared with the 1989 elections. Both of those events were in fact a plebiscite about confidence in the government. In fact, the ruling party did not lose because people liked the opposition so much. The voters simply hated the government. The level of arrogance and corruption of the state was also similar in the case of Communists and Civic Platform.

This the first time there is no Left in the Polish Sejm. There are two main factors that contributed to this fact.

First, many of the economic “social postulates” of the Left have been adopted by other parties. Both Law and Justice as well as the Kukiz’15 coalition have proposed raising the minimum wage, putting higher taxes on banks and corporations, creating more aid for the poor, raising financial aid for families, lowering the retirement age, etc. It must be emphasized that Poland does not provide much welfare or aid for anyone. For instance, if a child is born, parents get 250 euros from the state once . . . and that is pretty much it.

Second, the mainstream media and the government began to promote “modern patriotism.” Which basically means not talking about history too much, always displaying the Polish flag next to the European Union flag, cleaning up after your dog, and paying your taxes. They started mocking and suppressing all forms of radical patriotism and especially nationalism. Thus, patriotism and nationalism have become a form of rebellion for the youth, who (even if they supported more Left-leaning economic solutions) refused to vote either for the post-Communist or the cosmopolitan Left.

Many patriots and nationalists are now cheering for the young Leftist Razem party, which consists of nice young people who have in a way finished off the post-Communists. Sure, even I agree with some of their agenda, such as more support for public transport or aid for the poor members of society. However, under those nice appearances lurks real evil: the young Leftists demand a ban on nationalism (under the pretense of hate-prevention legislation), allowing all Muslim immigrants into Poland, and preference for non-Poles in state welfare. This is, simply speaking, the party of total replacement of the native Polish population.

There are also no libertarians in the Polish Sejm. They never actually made it, but they have always been considered a loud voice in Polish politics, and many people pretty much agreed with what they said, although they voted for different parties. It seems that the general public has shifted towards more statist economic policies.

Polish nationalists are now in an ambivalent position. So far, they have tried to adopt three strategies for various elections.

The first one was to take part on their own, either as a party or as a coalition of parties. This strategy failed, and they never got close to the electoral threshold.

The second one was to align with the libertarians. This also failed as libertarians turned out to be politically as weak as the nationalists.

The third one was to align with the populists, namely the Kukiz’15 movement. This has partly worked, and there will be some nationalists present in the Polish Sejm. However, as some point out, they had to more or less hide their views from the public, and those who have won seats are not the most idealistic types.

It seems that Law and Justice will become the Polish Fidesz. Kaczyński has always praised Viktor Orbán, although he rejects his pro-Russian policies. There is no way there will be any actual nationalists accepted in the Law and Justice party. Kaczyński will aim to destroy anyone to the right of him. Nationalists will have to either become the Polish Jobbik or stick to the strategy of alliance with the populists. The Polish political scene is quite chaotic, thus it is difficult to make any long-term predictions. Thus, perhaps the best strategy is to stick to the metapolitical model (creating and propagating a nationalist theoretical framework as well as building alternative communities) at the same time trying to insert nationalist activists into the populist movements, who might later (due to the lack of their own coherent agenda) turn to nationalists to provide a solid theoretical foundation.

The foreign media present Jarosław Kaczyński and his PiS party as a hardcore traditionalist nationalist force, which will turn Poland into a nationalist illiberal democracy (which could be quite good) and a religious Catholic state (which would be awful), which will leave the European Union and create an alternative federation of Eastern European countries (good again!) and wage war against Russia (awful again!).

The truth is much different. Jarosław Kaczyński and his party are just typical Right-center European politicians. Law and Justice are very pro-EU, although they wish it to be more conservative. They are even more pro-US and NATO, and their servility toward American officials is disgusting. Jarosław Kaczyński personally is also extremely judeophilic. It was his brother Lech who during his presidency has introduced the official celebration of Chanukah by the President (in a country where there about 40 actual religious Jewish families!), and he always stresses the role of Jews in Polish culture as well as praises the “eternal Polish-Jewish friendship.” One thing that the media get right about Jarosław Kaczyński is that he is not just anti-Putinist, but truly Russophobic. At best, Jarosław Kaczyński is a rather conservative Right-center European politician with statist tendencies in economics, who supports some sort of civic nationalism. At worst, he is a mindless cuckservative servant of the US neocons, who will attempt to crush Polish nationalism to please his masters. He is also a very ineffective politician, which means that he might not do much good, but he will probably not screw up much either. So, no illusions, gentlemen!

Two positive facts about the new political situation in Poland are important in a broader European context. First, Poles are overwhelmingly against accepting so-called “refugees.” Despite enormous propaganda efforts from the media and Civic Platform government, most Poles believe that Poland should accept no immigrants at all. Law and Justice have so far suggested that they will at least aim at lowering the quotas accepted by the previous government, but one of the slogans of the populists was “Zero immigrants!” Thus, in order to gain their support on other important projects, the new government will probably have to play it tough on Muslim immigration. Second, both the new government and the new President support the Baltic Sea-Black Sea Union or the Intermarium [5] project, and they wish to realize it based on the Visegrad Group. And this might provide some slight hope for a European revival.

Le Groupe de Visegrád va certainement être de plus en plus écouté au sein même de l'Union européenne. Ils proposent la restauration des frontières pour contrôler l'afflux de migrants, notamment dans les pays qui sont sur la route de la migration vers l'Allemagne. Ils mettent également, au service des gouvernements qui en feront la demande, une douane composée de policiers des différents pays du Groupe pour surveiller les frontières et assurer leur étanchéité.

Le Groupe de Visegrád va certainement être de plus en plus écouté au sein même de l'Union européenne. Ils proposent la restauration des frontières pour contrôler l'afflux de migrants, notamment dans les pays qui sont sur la route de la migration vers l'Allemagne. Ils mettent également, au service des gouvernements qui en feront la demande, une douane composée de policiers des différents pays du Groupe pour surveiller les frontières et assurer leur étanchéité.

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

Aristocratisch

Aristocratisch Icoon

Icoon Becher mocht dan wel marxist-leninist zijn, maar aan zijn vaderlandsliefde, aan zijn gloeiende liefde voor Duitsland en zijn grootse cultuur heeft hij nooit enige twijfel laten bestaan (zoals blijkt uit vele redevoeringen en zijn 'Deutschland-Dichtung'). De historicus Diesener had ontdekt dat de linkse Becher de rechtse Jünger als medestrijder tegen de nazi's wilde winnen, vanuit het besef 'Es ist Zeit, dass wir Deutschlandstreiter von rechts bis links unsere Waffen zusammenfassen' (het is tijd dat wij, strijders voor Duitsland van rechts tot links, onze wapens samenbrengen). Maar tegelijk wist Diesener dat Becher in een vroegere voordracht over het thema 'Moralische und ideologische Überwindung des Faschismus' (Morele en ideologische overwinning op het fascisme) Jünger als 'fascistische schrijver' had bestempeld. Daarom stelde Diesener de Poolse germanist Kuniciki de vraag of het vroegere oordeel van Becher over Jünger misschien niet moest worden herzien (gezien de respectvolle aanspreking in de radio-uitzending van oktober 1943) en hoe hij dit als kenner van de Duitse literatuur zag?

Becher mocht dan wel marxist-leninist zijn, maar aan zijn vaderlandsliefde, aan zijn gloeiende liefde voor Duitsland en zijn grootse cultuur heeft hij nooit enige twijfel laten bestaan (zoals blijkt uit vele redevoeringen en zijn 'Deutschland-Dichtung'). De historicus Diesener had ontdekt dat de linkse Becher de rechtse Jünger als medestrijder tegen de nazi's wilde winnen, vanuit het besef 'Es ist Zeit, dass wir Deutschlandstreiter von rechts bis links unsere Waffen zusammenfassen' (het is tijd dat wij, strijders voor Duitsland van rechts tot links, onze wapens samenbrengen). Maar tegelijk wist Diesener dat Becher in een vroegere voordracht over het thema 'Moralische und ideologische Überwindung des Faschismus' (Morele en ideologische overwinning op het fascisme) Jünger als 'fascistische schrijver' had bestempeld. Daarom stelde Diesener de Poolse germanist Kuniciki de vraag of het vroegere oordeel van Becher over Jünger misschien niet moest worden herzien (gezien de respectvolle aanspreking in de radio-uitzending van oktober 1943) en hoe hij dit als kenner van de Duitse literatuur zag? Titel boek :

Titel boek :

Mentionnant cette affaire

Mentionnant cette affaire

Le PiS et Kaczynski restent antirusses, sans le moindre doute, mais dans un temps où la question de l’antagonisme avec la Russie est en train de perdre en Europe même de son importance politique immédiate, notamment en Europe de l’Est, et alors que la Russie s’est placée dans une position très favorable du point de vue de la communication avec son intervention antiterroriste en Syrie ; par contre, la querelle européenne intervient quotidiennement dans la vie de tous les États-membres, et par conséquent dans celle de la Pologne et pas du tout à l’avantage de l’UE. La question de la mise en lumière complète des circonstances de l’accident de l’avion transportant Lech Kaczynski et sa suite continue à être une hypothèque considérable dans le chef du PiS et du Premier ministre polonais par rapport aux relations avec la Russie. Qu'importe puisque ce qui est en jeu aujourd’hui, ce ne sont plus les relations avec la Russie mais d’abord et essentiellement les relations de la Pologne avec l’UE et l’état de quasi-dissidence de la Pologne par rapport à l’UE qui s’ébauche avec les premières mesures du gouvernement Kaczynski.

Le PiS et Kaczynski restent antirusses, sans le moindre doute, mais dans un temps où la question de l’antagonisme avec la Russie est en train de perdre en Europe même de son importance politique immédiate, notamment en Europe de l’Est, et alors que la Russie s’est placée dans une position très favorable du point de vue de la communication avec son intervention antiterroriste en Syrie ; par contre, la querelle européenne intervient quotidiennement dans la vie de tous les États-membres, et par conséquent dans celle de la Pologne et pas du tout à l’avantage de l’UE. La question de la mise en lumière complète des circonstances de l’accident de l’avion transportant Lech Kaczynski et sa suite continue à être une hypothèque considérable dans le chef du PiS et du Premier ministre polonais par rapport aux relations avec la Russie. Qu'importe puisque ce qui est en jeu aujourd’hui, ce ne sont plus les relations avec la Russie mais d’abord et essentiellement les relations de la Pologne avec l’UE et l’état de quasi-dissidence de la Pologne par rapport à l’UE qui s’ébauche avec les premières mesures du gouvernement Kaczynski.

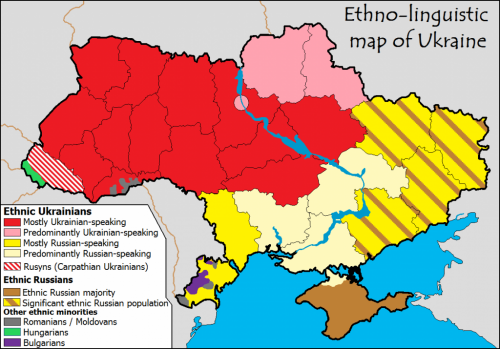

Jan Stachniuk was born in 1905 in Kowel, Wołyń (in what is today Ukraine). In 1927, he began his public activity in Poznań, where he studied economics. There, he became active in the Union of Polish Democratic Youth and published his first books: Kolektywizm a naród (1933) and Heroiczna wspólnota narodu (1935). Beginning in 1937, Stachniuk published the monthly magazine Zadruga, which gave birth to a new idea current of the same name. In 1939, two additional books were published: Państwo a gospodarstwo and Dzieje bez dziejów (“History of unhistory”). During the Second World War, he inspired the ideology of the Faction of the National Rise (Stronnictwo Zrywu Narodowego) and the Cadre of Independent Poland (Kadra Polski Niepodległej). In 1943, Stachniuk published Zagadnienie totalizmu (with the help of the Faction). He fought in the Warsaw Uprising and was wounded. After the war, he failed to resume publishing Zadruga, but before the Stalinists attained power in the country, he managed to publish three more books: Walka o zasady, Człowieczeństwo i kultura, and Wspakultura. In 1949, Stachniuk was arrested and sentenced to death in a political show trial. The sentence was not carried out, and he got out of prison in 1955, but he was no longer able to perform any kind work. He died in 1963 and was buried in the Powązki Cemetery.

Jan Stachniuk was born in 1905 in Kowel, Wołyń (in what is today Ukraine). In 1927, he began his public activity in Poznań, where he studied economics. There, he became active in the Union of Polish Democratic Youth and published his first books: Kolektywizm a naród (1933) and Heroiczna wspólnota narodu (1935). Beginning in 1937, Stachniuk published the monthly magazine Zadruga, which gave birth to a new idea current of the same name. In 1939, two additional books were published: Państwo a gospodarstwo and Dzieje bez dziejów (“History of unhistory”). During the Second World War, he inspired the ideology of the Faction of the National Rise (Stronnictwo Zrywu Narodowego) and the Cadre of Independent Poland (Kadra Polski Niepodległej). In 1943, Stachniuk published Zagadnienie totalizmu (with the help of the Faction). He fought in the Warsaw Uprising and was wounded. After the war, he failed to resume publishing Zadruga, but before the Stalinists attained power in the country, he managed to publish three more books: Walka o zasady, Człowieczeństwo i kultura, and Wspakultura. In 1949, Stachniuk was arrested and sentenced to death in a political show trial. The sentence was not carried out, and he got out of prison in 1955, but he was no longer able to perform any kind work. He died in 1963 and was buried in the Powązki Cemetery. The sensation of the creative pressure, the feeling of the cosmic mission of creation, the desire to contribute to the creative world evolution by man is, in the lens of Culturalism, a sign of health and moral youth. According to Stachniuk, this is normal, the way it should be. Human history is the eternal antagonism of two, contradictory, directions—“the first one is the blind pressure of man towards panhumanism, the second is the escape into a solidified system.”

The sensation of the creative pressure, the feeling of the cosmic mission of creation, the desire to contribute to the creative world evolution by man is, in the lens of Culturalism, a sign of health and moral youth. According to Stachniuk, this is normal, the way it should be. Human history is the eternal antagonism of two, contradictory, directions—“the first one is the blind pressure of man towards panhumanism, the second is the escape into a solidified system.”

En la primavera de 1940 la URSS líquidó a 22.000 oficiales polacos.

En la primavera de 1940 la URSS líquidó a 22.000 oficiales polacos.

Tommasini ha lasciato un libro molto documentato sulla sua esperienza di ambasciatore italiano in Polonia, nel libro La risurrezione della Polonia (Milano, Fratelli Treves Editori, 1925, pp. 113-118), di cui riportiamo alcuni passaggi:

Tommasini ha lasciato un libro molto documentato sulla sua esperienza di ambasciatore italiano in Polonia, nel libro La risurrezione della Polonia (Milano, Fratelli Treves Editori, 1925, pp. 113-118), di cui riportiamo alcuni passaggi:

Speeches

Speeches

On projette donc le très beau film "Katyn" ce 14 avril (1) sur la chaîne franco-allemande Arte. Au-delà de l'œuvre de Wajda elle-même (2), de son scénario, tiré d'un roman mais aussi de l'expérience personnelle du cinéaste dans la Pologne communiste d'après-guerre, il faut considérer l'Histoire. Celle-ci accable non seulement Staline personnellement mais, d'une manière plus générale, le communisme international. Au premier rang en occident le parti le plus servile, le parti français, le parti de Maurice Thorez et de Jacques Duclos partage 100 % de la culpabilité de son maître. Et il faut y ajouter une circonstance aggravante. Car, après la Pologne en 1939, abandonnée par les radicaux-socialistes en charge à Paris de la conduite de la guerre, le sort de la France suivit en 1940.

On projette donc le très beau film "Katyn" ce 14 avril (1) sur la chaîne franco-allemande Arte. Au-delà de l'œuvre de Wajda elle-même (2), de son scénario, tiré d'un roman mais aussi de l'expérience personnelle du cinéaste dans la Pologne communiste d'après-guerre, il faut considérer l'Histoire. Celle-ci accable non seulement Staline personnellement mais, d'une manière plus générale, le communisme international. Au premier rang en occident le parti le plus servile, le parti français, le parti de Maurice Thorez et de Jacques Duclos partage 100 % de la culpabilité de son maître. Et il faut y ajouter une circonstance aggravante. Car, après la Pologne en 1939, abandonnée par les radicaux-socialistes en charge à Paris de la conduite de la guerre, le sort de la France suivit en 1940.

Le 25 novembre 2008, on a ouvert la crypte de la Cathédrale de Cracovie qui servait de tombeau à Wladyslaw Sikorski, premier ministre du gouvernement polonais en exil (de 1939 à 1943). Le procureur de la République de Pologne a ordonné d’exhumer le corps de Sikorski pour faire définitivement la lumière, à l’aide des méthodes techniques les plus modernes employées actuellement par la criminologie, sur les causes véritables de la mort du général et homme politique polonais, ôté à la vie, il y a plus de soixante-cinq ans lors de la chute de son avion dans la mer au large de Gibraltar. La nouvelle de la mort « accidentelle » du chef du gouvernement polonais Sikorski avait à peine été divulguée, le 4 juillet 1943, que les premiers doutes quant à la vérité de cette nouvelle étaient émis. Les experts en aéronautique et les observateurs critiques, à l’époque, ont jugé peu crédible, pour diverses raisons, la version d’un « accident d’avion ayant entrainé la mort ». La première chose qui les a frappés, c’est que lors de la chute de l’appareil utilisé par Sikorski tous les passagers n’ont pas trouvé la mort mais seulement une partie de ceux-ci, comme si certains d’entre eux avaient été « ciblés ». Par ailleurs, personne n’a pu dissimuler que le premier ministre polonais était tombé en disgrâce profonde chez Staline.

Le 25 novembre 2008, on a ouvert la crypte de la Cathédrale de Cracovie qui servait de tombeau à Wladyslaw Sikorski, premier ministre du gouvernement polonais en exil (de 1939 à 1943). Le procureur de la République de Pologne a ordonné d’exhumer le corps de Sikorski pour faire définitivement la lumière, à l’aide des méthodes techniques les plus modernes employées actuellement par la criminologie, sur les causes véritables de la mort du général et homme politique polonais, ôté à la vie, il y a plus de soixante-cinq ans lors de la chute de son avion dans la mer au large de Gibraltar. La nouvelle de la mort « accidentelle » du chef du gouvernement polonais Sikorski avait à peine été divulguée, le 4 juillet 1943, que les premiers doutes quant à la vérité de cette nouvelle étaient émis. Les experts en aéronautique et les observateurs critiques, à l’époque, ont jugé peu crédible, pour diverses raisons, la version d’un « accident d’avion ayant entrainé la mort ». La première chose qui les a frappés, c’est que lors de la chute de l’appareil utilisé par Sikorski tous les passagers n’ont pas trouvé la mort mais seulement une partie de ceux-ci, comme si certains d’entre eux avaient été « ciblés ». Par ailleurs, personne n’a pu dissimuler que le premier ministre polonais était tombé en disgrâce profonde chez Staline. Fondé en 1937 par Jan Stachniuk, la revue et le mouvement Zadruga ont voulu, dans la Pologne catholique, exprimé et illustré une sensibilité païenne, ont perçu l'essentiel dans l'enraciment dynamique et évolutif dans une terre, dans la localisation précise des hommes et des peuples, localisation d'où s'élance un déploiement harmonieux et créatif. Cet enracinement/localisation constitue la culture proprement dite: les théories, idées, systèmes, principes qui ne reposent pas sur ce locus primordial relèvent de la non-culture, dont le père spirituel est Socrate. Les idéaux du socratisme sont vidés de toute concrétude et brisent l'élan de l'homo creans enraciné. Les grands systèmes religieux et/ou philosophiques (bouddhisme, islam, christianismes) relèvent de la non-culture.

Fondé en 1937 par Jan Stachniuk, la revue et le mouvement Zadruga ont voulu, dans la Pologne catholique, exprimé et illustré une sensibilité païenne, ont perçu l'essentiel dans l'enraciment dynamique et évolutif dans une terre, dans la localisation précise des hommes et des peuples, localisation d'où s'élance un déploiement harmonieux et créatif. Cet enracinement/localisation constitue la culture proprement dite: les théories, idées, systèmes, principes qui ne reposent pas sur ce locus primordial relèvent de la non-culture, dont le père spirituel est Socrate. Les idéaux du socratisme sont vidés de toute concrétude et brisent l'élan de l'homo creans enraciné. Les grands systèmes religieux et/ou philosophiques (bouddhisme, islam, christianismes) relèvent de la non-culture.

Lituania, Polonia y Ucrania unidos militarmente

Lituania, Polonia y Ucrania unidos militarmente

Die Sitzung im Warschauer Parlament dürfte als Desaster für die Pandemie-, pardon: Pharmaindustrie in die Geschichte eingehen. Geladen waren Sachverständige und Statistiker, um über die angebliche Schweinegrippe-Pandemie zu beraten.

Die Sitzung im Warschauer Parlament dürfte als Desaster für die Pandemie-, pardon: Pharmaindustrie in die Geschichte eingehen. Geladen waren Sachverständige und Statistiker, um über die angebliche Schweinegrippe-Pandemie zu beraten.