Robert Steuckers:

L’itinéraire d’un géopolitologue allemand: Karl Haushofer

Préambule: le texte qui suit est une brève recension du premier des deux épais volumes que le Prof. Hans-Adolf Jacobsen a consacré à Karl Haushofer. Le travail à accomplir pour réexplorer en tous ses recoins l’oeuvre de Karl Haushofer, y compris sa correspondance, est encore immense. Puisse cette modeste contribution servir de base aux étudiants qui voudraient, dans une perspective néo-eurasienne, entamer une lecture des oeuvres de Haushofer et surtout analyser tous les articles parus dans sa “Zeitschrift für Geopolitik”.

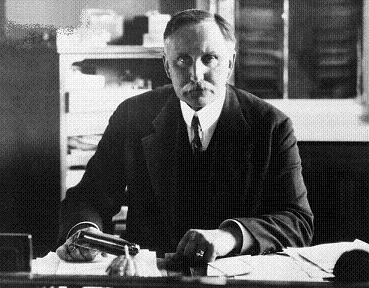

Haushofer est né en 1869 dans une famille bien ancrée dans le territoire bavarois. Les archives nous rappellent que le nom apparaît dès 1352, pour désigner une famille paysanne originaire de de la localité de Haushofen. Les ancêtres maternels, eux, sont issus du pays frison dans le nord de l’Allemagne. Orphelin de mère très tôt, dès l’âge de trois ans, le jeune Karl Haushofer sera élevé par ses grands-parents maternels en Bavière dans la région du Chiemsee. Le grand-père Fraas était professeur de médecine vétérinaire à Munich. En évoquant son enfance heureuse, Haushofer, plus tard, prend bien soin de rappeler que les différences de caste étaient inexistantes en Bavière: les enfants de toutes conditions se côtoyaient et se fréquentaient, si bien que les arrogances de classe étaient inexistantes: sa bonhommie et sa gentillesse, proverbiales, sont le fruit de cette convivialité baroque: ses intiatives porteront la marque de ce trait de caractère. Haushofer se destine très tôt à la carrière militaire qu’il entame dès 1887 au 1er Régiment d’Artillerie de campagne de l’armée du Royaume de Bavière.

En mission au Japon

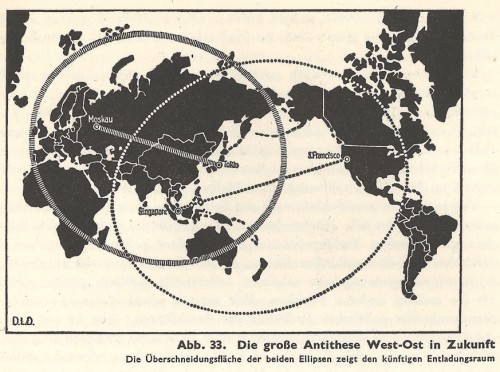

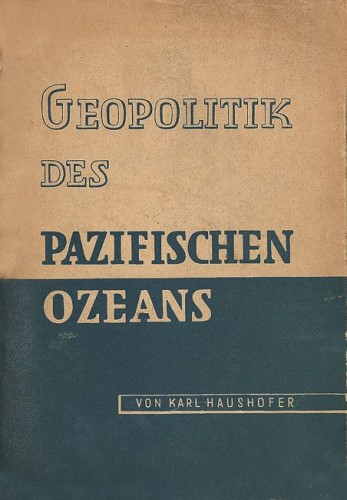

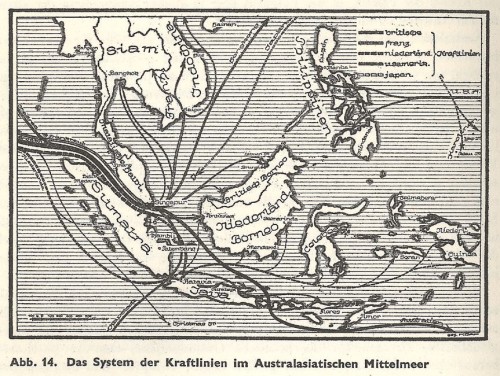

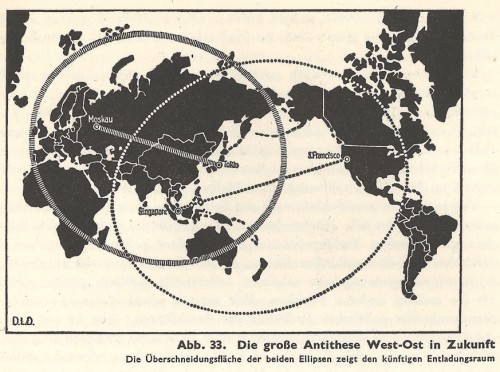

Le 8 août 1896, il épouse Martha Mayer-Doss, une jeune femme très cultivée d’origine séphérade, côté paternel, de souche aristocratique bavaroise, côté maternel. Son esprit logique seront le pendant nécessaire à la fantaisie de son mari, à l’effervescence bouillonnante de son esprit et surtout de son écriture. Elle lui donnera deux fils: Albrecht (1903-1945), qui sera entraîné dans la résistance anti-nazie, et Heinz (1906-?), qui sera un agronome hors ligne. Le grand tournant de la vie de Karl Haushofer, le début véritable de sa carrière de géopolitologue, commence dès son séjour en Asie orientale, plus particulièrement au Japon (de la fin 1908 à l’été 1910), où il sera attaché militaire puis instructeur de l’armée impériale japonaise. Le voyage du couple Haushofer vers l’Empire du Soleil Levant commence à Gênes et passe par Port Saïd, Ceylan, Singapour et Hong Kong. Au cours de ce périple maritime, il aborde l’Inde, voit de loin la chaîne de l’Himalaya et rencontre Lord Kitchener, dont il admire la “créativité défensive” en matière de politique militaire. Lors d’un dîner, début 1909, Lord Kitchener lui déclare “que toute confrontation entre l’Allemagne et la Grande-Bretagne coûterait aux deux puissances leurs positions dans l’Océan Pacifique au profit du Japon et des Etats-Unis”. Haushofer ne cessera de méditer ces paroles de Lord Kitchener. En effet, avant la première guerre mondiale, l’Allemagne a hérité de l’Espagne la domination de la Micronésie qu’elle doit défendre déjà contre les manigances américaines, alors que les Etats-Unis sont maîtres des principales îles stratégiques dans cet immense espace océanique: les Philippines, les Iles Hawaï et Guam. Dès son séjour au Japon, Haushofer devient avant tout un géopolitologue de l’espace pacifique: il admet sans réticence la translatio imperii en Micronésie, où l’Allemagne, à Versailles, doit céder ces îles au Japon; pour Haushofer, c’est logique: l’Allemagne est une “puissance extérieure à l’espace pacifique” tandis que le Japon, lui, est une puissance régionale, ce qui lui donne un droit de domination sur les îles au sud de son archipel métropolitain. Mais toute présence souveraine dans l’espace pacifique donne la maîtrise du monde: Haushofer n’est donc pas exclusivement le penseur d’une géopolitique eurasienne et continentale, ou un exposant érudit d’une géopolitique nationaliste allemande, il est aussi celui qui va élaborer, au fil des années dans les colonnes de la revue “Zeitschrift für Geopolitik”, une thalassopolitique centrée sur l’Océan Pacifique, dont les lecteurs les plus attentifs ne seront pas ses compatriotes allemands ou d’autres Européens mais les Soviétiques de l’agence “Pressgeo” d’Alexander Rados, à laquelle collaborera un certain Arthur Koestler et dont procèdera le fameux espion soviétique Richard Sorge, également lecteur très attentif de la “Zeitschrift für Geopolitik” (ZfG). Dans son journal, Haushofer rappelle les rapports qu’il a eus avec des personnalités soviétiques comme Tchitchérine et Radek-Sobelsohn. L’intermédiaire entre Haushofer et Radek était le Chevalier von Niedermayer, qui avait lancé des expéditions en Perse et en Afghanistan. Niedermayer avait rapporté un jour à Haushofer que Radek lisait son livre “Geopolitik der Pazifischen Ozeans”, qu’il voulait faire traduire. Radek, roublard, ne pouvait faire simplement traduire le travail d’un général bavarois et a eu une “meilleure” idée dans le contexte soviétique de l’époque: fabriquer un plagiat assorti de phraséologie marxiste et intitulé “Tychookeanskaja Probljema”. Toutes les thèses de Haushofer y était reprises, habillées d’oripeaux marxistes. Autre intermédiaire entre Radek et Haushofer: Mylius Dostoïevski, petit-fils de l’auteur des “Frères Karamazov”, qui apportait au géopolitologue allemand des exemplaires de la revue soviétique de politique internationale “Nowy Vostok” (= “Nouveau Monde”), des informations soviétiques sur la Chine et le Japon et des écrits du révolutionnaire indonésien Tan Malakka sur le mouvement en faveur de l’auto-détermination de l’archipel, à l’époque sous domination néerlandaise.

Le séjour en Extrême-Orient lui fait découvrir aussi l’importance de la Mandchourie pour le Japon, qui cherche à la conquérir pour se donner des terres arables sur la rive asiatique qui fait face à l’archipel nippon (l’achat de terres arables, notamment en Afrique, par des puissances comme la Chine ou la Corée du Sud est toujours un problème d’actualité...). Les guerres sino-japonaises, depuis 1895, visent le contrôle de terres d’expansion pour le peuple japonais coincé sur son archipel montagneux aux espaces agricoles insuffisants. Dans les années 30, elles viseront à contrôler la majeure partie des côtes chinoises pour protéger les routes maritimes acheminant le pétrole vers les raffineries nippones, denrée vitale pour l’industrie japonaise en plein développement.

Début d’une carrière universitaire

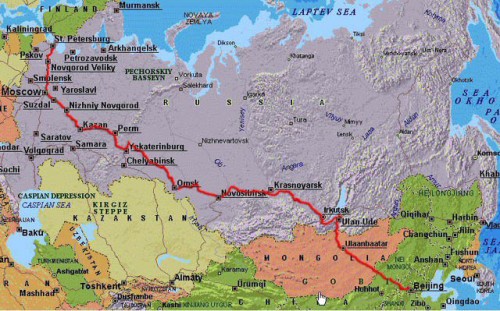

Le retour en Allemagne de Karl et Martha Haushofer se fait via le Transibérien, trajet qui fera comprendre à Haushofer ce qu’est la dimension continentale à l’heure du chemin de fer qui a réduit les distances entre l’Europe et l’Océan Pacifique. De Kyoto à Munich, le voyage prendra exactement un mois. Le résultat de ce voyage est un premier livre, “Dai Nihon – Grossjapan” (en français: “Le Japon et les Japonais”, avec une préface de l’ethnologue franco-suisse Georges Montandon). Le succès du livre est immédiat. Martha Haushofer contacte alors le Professeur August von Drygalski (Université de Munich) pour que son mari puisse suivre les cours de géographie et passer à terme une thèse de doctorat sur le Japon. Haushofer est, à partir de ce moment-là, à la fois officier d’artillerie et professeur à l’Université. En 1913, grâce à la formidable puissance de travail de son épouse Martha, qui le seconde avec une redoutable efficacité dans tous ses projets, sa thèse est prête. La presse spécialisée se fait l’écho de ses travaux sur l’Empire du Soleil Levant. Sa notoriété est établie. Mais les voix critiques ne manquent pas: sa fébrilité et son enthousiasme, sa tendance à accepter n’importe quelle dépêche venue du Japon sans vérification sourcilleuse du contenu, son rejet explicite des “puissances ploutocratiques” (Angleterre, Etats-Unis) lui joueront quelques tours et nuiront à sa réputation jusqu’à nos jours, où il n’est pas rare de lire encore qu’il a été un “mage” et un “géographe irrationnel”.

Le déclenchement de la première guerre mondiale met un terme (tout provisoire) à ses recherches sur le Japon. Les intérêts de Haushofer se focalisent sur la “géographie défensive” (la “Wehrgeographie”) et sur la “Wehrkunde” (la “science de la défense”). C’est aussi l’époque où Haushofer découvre l’oeuvre du géographe conservateur et germanophile suédois Rudolf Kjellen, auteur d’un ouvrage capital et pionnier en sciences politiques: “L’Etat comme forme de vie” (“Der Staat als Lebensform”). Kjellen avait forgé, dans cet ouvrage, le concept de “géopolitique”. Haushofer le reprend à son compte et devient ainsi, à partir de 1916, un géopolitologue au sens propre du terme. Il complète aussi ses connaissances par la lecture des travaux du géographe allemand Friedrich Ratzel (à qui l’on doit la discipline de l’anthropogéographie); c’est l’époque où il lit aussi les oeuvres des historiens anglais Gibbon (“Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire”) et Macaulay, exposant de la vision “Whig” (et non pas conservatrice) de l’histoire anglaise, étant issu de familles quaker et presbytérienne. Les événements de la première guerre mondiale induisent Haushofer à constater que le peuple allemand n’a pas reçu —en dépit de l’excellence de son réseau universitaire, de ses érudits du 19ème siècle et de la fécondité des oeuvres produites dans le sillage de la pensée organique allemande,— de véritable éducation géopolitique et “wehrgeographisch”, contrairement aux Britanniques, dont les collèges et universités ont été à même de communiquer aux élites le “sens de l’Empire”.

Réflexions pendant la première guerre mondiale

Ce n’est qu’à la fin du conflit que la fortune des armes passera dans le camp de l’Entente. Au début de l’année 1918, en dépit de la déclaration de guerre des Etats-Unis de Woodrow Wilson au Reich allemand, Haushofer est encore plus ou moins optimiste et esquisse brièvement ce qui, pour lui, serait une paix idéale: “La Courlande, Riga et la Lituanie devront garder des liens forts avec l’Allemagne; la Pologne devra en garder d’équivalents avec l’Autriche; ensuite, il faudrait une Bulgarie consolidée et agrandie; à l’Ouest, à mon avis, il faudrait le statu quo tout en protégeant les Flamands, mais sans compensation allemande pour la Belgique et évacuation pure et simple de nos colonies et de la Turquie. Dans un tel contexte, la paix apportera la sécurité sur notre flanc oriental et le minimum auquel nous avons droit; il ne faut absolument pas parler de l’Alsace-Lorraine”. L’intervention américaine lui fera écrire dans son journal: “Plutôt mourir européen que pourrir américain”.

Haushofer voulait dégager les “trois grands peuples de l’avenir”, soit les Allemands, les Russes et les Japonais, de l’étranglement que leur préparaient les puissances anglo-saxonnes. Les énergies de l’ “ours russe” devaient être canalisées vers le Sud, vers l’Inde,sans déborder ni à l’Ouest, dans l’espace allemand, ni à l’Est dans l’espace japonais. L’ “impérialisme du dollar” est, pour Haushofer, dès le lendemain de Versailles, le “principal ennemi extérieur”. Face à la nouvelle donne que constitue le pouvoir bolchevique à Moscou, Haushofer est mitigé: il rejette le style et les pratiques bolcheviques mais concède qu’elles ont libéré la Russie (et projettent de libérer demain tous les peuples) de “l’esclavage des banques et du capital”.

En 1919, pendant les troubles qui secouent Munich et qui conduisent à l’émergence d’une République des Conseils en Bavière, Haushofer fait partie des “Einwohnerwehrverbände” (des unités de défense constituées par les habitants de la ville), soit des milices locales destinées à maintenir l’ordre contre les émules de la troïka “conseilliste” et contre les pillards qui profitaient des désordres. Elles grouperont jusqu’à 30.000 hommes en armes dans la capitale bavaroise (et jusqu’à 360.000 hommes dans toute la Bavière). Ces unités seront définitivement dissoutes en 1922.

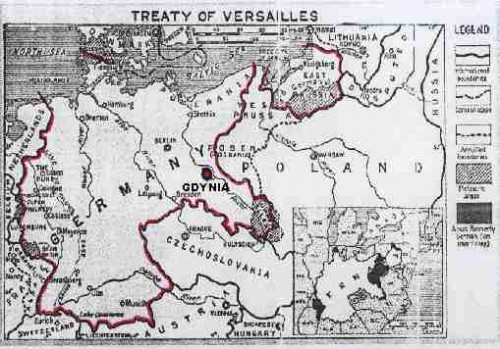

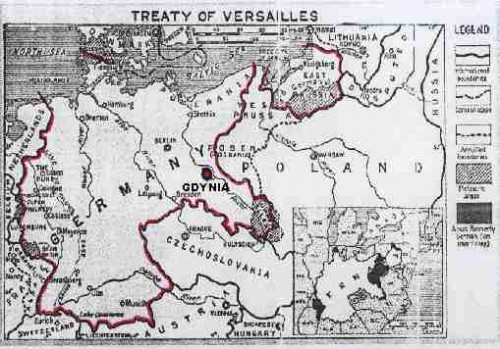

Les résultats du Traité de Versailles

La fin de la guerre et des troubles en Bavière ramène Haushofer à l’Université, avec une nouvelle thèse sur l’expansion géographique du Japon entre 1854 et 1919. Une chaire est mise à sa disposition en 1919/1920 où les cours suivants sont prodigués à onze étudiants: Asie orientale, Inde, Géographie comparée de l’Allemagne et du Japon, “Wehrgeographie”, Géopolitique, Frontières, Anthropogéographie, Allemands de l’étranger, Urbanisme, Politique Internationale, Les rapports entre géographie, géopolitique et sciences militaires. L’objectif de ces efforts était bien entendu de former une nouvelle élite politique et diplomatique en mesure de provoquer une révision des clauses du Traité de Versailles. Pour Wilson, le principe qui aurait dû régir la future Europe après les hostilités était celui des “nationalités”. Aucune frontière des Etats issus notamment de la dissolution de l’Empire austro-hongrois ne correspondait à ce principe rêvé par le président des Etats-Unis. Dans chacun de ces Etats, constataient Haushofer et les autres exposants de la géopolitique allemande, vivaient des minorités diverses mais aussi des minorités germaniques (dix millions de personnes en tout!), auxquelles on refusait tout contact avec l’Allemagne, comme on refusait aux Autrichiens enclavés, privés de l’industrie tchèque, de la viande et de l’agriculture hongroises et croates et de toute fenêtre maritime de se joindre à la République de Weimar, ce qui était surtout le voeu des socialistes à l’époque (ils furent les premiers, notamment sous l’impulsion de leur leader Viktor Adler, à demander l’Anschluss). L’Allemagne avait perdu son glacis alsacien-lorrain et sa province riche en blé de Posnanie, de façon à rendre la Pologne plus ou moins autarcique sur le plan alimentaire, car elle ne possédait pas de bonnes terres céréalières. La Rhénanie était démilitarisée et aucune frontière du Reich était encore “membrée” pour reprendre, avec Haushofer, la terminologie forgée au 17ème siècle par Richelieu et Vauban. Dans de telles conditions, l’Allemagne ne pouvait plus être “un sujet de l’histoire”.

Redevenir un “sujet de l’histoire”

Pour redevenir un “sujet de l’histoire”, l’Allemagne se devait de reconquérir les sympathies perdues au cours de la première guerre mondiale. Haushofer parvient à exporter son concept, au départ kjellénien, de “géopolitique”, non seulement en Italie et en Espagne, où des instituts de géopolitique voient le jour (pour l’Italie, Haushofer cite les noms suivants dans son journal: Ricciardi, Gentile, Tucci, Gabetti, Roletto et Massi) mais aussi en Chine, au Japon et en Inde. La géopolitique, de facture kjellénienne et haushoférienne, se répand également par dissémination et traduction dans une quantité de revues dans le monde entier. La deuxième initiative qui sera prise, dès 1925, sera la création d’une “Deutsche Akademie”, qui avait pour but premier de s’adresser aux élites germanophones d’Europe (Autriche, Suisse, minorités allemandes, Flandre, Scandinavie, selon le journal tenu par Haushofer). Cette Académie devait compter 100 membres. L’idée vient au départ du légat de Bavière à Paris, le Baron von Ritter qui, en 1923 déjà, préconisait la création d’une institution allemande semblable à l’Institut de France ou même à l’Académie française, afin d’entretenir de bons et fructueux contacts avec l’étranger dans une perspective d’apaisement constructif. Bien que mise sur pied et financée par des organismes privés, la “Deutsche Akademie” ne connaîtra pas le succès que méritait son programme séduisant. Les “Goethe-Institute”, qui représentent l’Allemagne sur le plan culturel aujourd’hui, en sont les héritiers indirects, depuis leur fondation en 1932.

L’objectif des instituts de géopolitique, de la Deutsche Akademie et des “Goethe-Institute” est donc de générer au sein du peuple allemand une sorte d’ “auto-éducation” permanente aux faits géographiques et aux problèmes de la politique internationale. Cette “auto-éducation” ou “Selbsterziehung” repose sur un impératif d’ouverture au monde, exactement comme Karl et Martha Haushofer s’étaient ouverts aux réalités indiennes, asiatiques, pacifiques et sibériennes entre 1908 et 1910, lors de leur mission militaire au Japon. Haushofer explique cette démarche dans un mémorandum rédigé dans sa villa d’Hartschimmelhof en août 1945. La première guerre mondiale, y écrit-il, a éclaté parce que les 70 nations, qui y ont été impliquées, ne possédaient pas les outils intellectuels pour comprendre les actions et les manoeuvres des autres; ensuite, les idéologies dominantes avant 1914 ne percevaient pas la “sacralité de la Terre” (“das Sakrale der Erde”). Des connaissances géographiques et historiques factuelles, couplées à cette intuition tellurique —quasi romantique et mystique à la double façon du “penseur et peintre tellurique” Carl Gustav Carus, au 19ème siècle, et de son héritier Ludwig Klages qui préconise l’attention aux mystères de la Terre dans son discours aux mouvements de jeunesse lors de leur rassemblement de 1913— auraient pu contribuer à une entente générale entre les peuples: l’intuition des ressources de Gaia, renforcée par une “tekhnê” politique adéquate, aurait généré une sagesse générale, partagée par tous les peuples de la Terre. La géopolitique, dans l’optique de Haushofer, quelques semaines après la capitulation de l’Allemagne, aurait pu constituer le moyen d’éviter toute saignée supplémentaire et toute conflagration inutile (cf. Jacobsen, tome I, pp. 258-259).

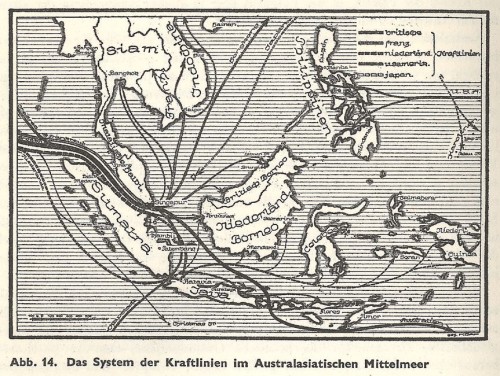

Une géopolitique révolutionnaire dans les années 20

En dépit de ce mémorandum d’août 1945, qui regrette anticipativement la disparition de toute géopolitique allemande, telle que Haushofer et son équipe l’avaient envisagée, et souligne la dimension “pacifiste”, non au sens usuel du terme mais selon l’adage latin “Si vis pacem, para bellum” et selon l’injonction traditionnelle qui veut que c’est un devoir sacré (“fas”) d’apprendre de l’ennemi, Haushofer a été aussi et surtout —c’est ce que l’on retient de lui aujourd’hui— l’élève rebelle de Sir Halford John Mackinder, l’élève qui inverse les intentions du maître en retenant bien la teneur de ses leçons; pour Mackinder, à partir de son célèbre discours de 1904 au lendemain de l’inauguration du dernier tronçon du Transibérien, la dynamique de l’histoire reposait sur l’opposition atavique et récurrente entre puissances continentales et puissances maritimes (ou thalassocraties). Les puissances littorales du grand continent eurasiatique et africain sont tantôt les alliées des unes tantôt celles des autres. Dans les années 20, où sa géopolitique prend forme et influence les milieux révolutionnaires (dont les cercles que fréquentaient Ernst et Friedrich-Georg Jünger ainsi que la figure originale que fut Friedrich Hielscher, sans oublier les communistes gravitant autour de Radek et de Rados), Haushofer énumère les puissances continentales actives, énonciatrices d’une diplomatie originale et indépendante face au monde occidental anglo-saxon ou français: l’Union Soviétique, la Turquie (après les accords signés entre Mustafa Kemal Atatürk et le nouveau pouvoir soviétique à Moscou), la Perse (après la prise du pouvoir par Reza Khan), l’Afghanistan, le sous-continent indien (dès qu’il deviendra indépendant, ce que l’on croit imminent à l’époque en Allemagne) et la Chine. Il n’y incluait ni l’Allemagne (neutralisée et sortie du club des “sujets de l’histoire”) ni le Japon, puissance thalassocratique qui venait de vaincre la flotte russe à Tsoushima et qui détenait le droit, depuis les accords de Washington de 1922 d’entretenir la troisième flotte du monde (le double de celle de la France!) dans les eaux du Pacifique. Pour “contenir” les puissances de la Terre, constate Haushofer en bon lecteur de Mackinder, les puissances maritimes anglo-saxonnes ont créé un “anneau” de bases et de points d’appui comme Gibraltar, Malte, Chypre, Suez, les bases britanniques du Golfe Persique, l’Inde, Singapour, Hong Kong ainsi que la Nouvelle-Zélande et l’Australie, un cordon d’îles et d’îlots plus isolés (Tokelau, Suvarov, Cook, Pitcairn, Henderson, ...) qui s’étendent jusqu’aux littoraux du cône sud de l’Amérique du Sud. L’Indochine française, l’Insulinde néerlandaise et les quelques points d’appui et comptoirs portugais sont inclus, bon gré mal gré, dans ce dispositif en “anneau”, commandé depuis Londres.

Les Philippines, occupées depuis la guerre hispano-américaine puis philippino-américaine de 1898 à 1911 par les Etats-Unis, en sont le prolongement septentrional. Le Japon refuse de faire partie de ce dispositif qui permet pourtant de contrôler les routes du pétrole acheminé vers l’archipel nippon. L’Empire du Soleil Levant cherche à être une double puissance: 1) continentale avec la Mandchourie et, plus tard, avec ses conquêtes en Chine et avec la satellisation tacite de la Mongolie intérieure, et 2) maritime en contrôlant Formose, la presqu’île coréenne et la Micronésie, anciennement espagnole puis allemande. L’histoire japonaise, après Tsoushima, est marquée par la volonté d’assurer cette double hégémonie continentale et maritime, l’armée de terre et la marine se disputant budgets et priorités.

Un bloc continental défensif

Haushofer souhaite, à cette époque, que le “bloc continental”, soviéto-turco-perso-afghano-chinois, dont il souhaite l’unité stratégique, fasse continuellement pression sur l’ “anneau” de manière à le faire sauter. Cette unité stratégique est une “alliance pression/défense”, un “Druck-Abwehr-Verband”, soit une alliance de facto qui se défend (“Abwehr”) contre la pression (“Druck”) qu’exercent les bases et points d’appui des thalassocraties, contre toutes les tentatives de déploiement des puissances continentales. Haushofer dénonce, dans cette optique, le colonialisme et le racisme, qui en découle, car ces “ismes” bloquent la voie des peuples vers l’émancipation et l’auto-détermination. Dans l’ouvrage collectif “Welt in Gärung” (= “Le monde en effervescence”), Haushofer parle des “gardiens rigides du statu quo” (“starre Hüter des gewesenen Standes”) qui sont les obstacles (“Hemmungen”) à toute paix véritable; ils provoquent des révolutions bouleversantes et des effondrements déstabilisants, des “Umstürze”, au lieu de favoriser des changements radicaux et féconds, des “Umbrüche”. Cette idée le rapproche de Carl Schmitt, quand ce dernier critique avec acuité et véhémence les traités imposés par Washington dans le monde entier, dans le sillage de l’idéologie wilsonienne, et les nouvelles dispositions, en apparence apaisantes et pacifistes, imposées à Versailles puis à Genève dans le cadre de la SdN. Carl Schmitt critiquait, entre autres, et très sévèrement, les démarches américaines visant la destruction définitive du droit des gens classique, le “ius publicum europaeum” (qui disparait entre 1890 et 1918), en visant à ôter aux Etats le droit de faire la guerre (limitée), selon les théories juridiques de Frank B. Kellogg dès la fin des années 20. Il y a tout un travail à faire sur le parallèlisme entre Carl Schmitt et les écoles géopolitiques de son temps.

En dépit du grand capital de sympathie dont bénéficiait le Japon chez Haushofer depuis son séjour à Kyoto, sa géopolitique, dans les années 20, est nettement favorable à la Chine, dont le sort, dit-il, est similaire à celui de l’Allemagne. Elle a dû céder des territoires à ses voisins et sa façade maritime est neutralisée par la pression permanente qui s’exerce depuis toutes les composantes de l’ “anneau”, constitués par les points d’appui étrangers (surtout l’américain aux Philippines). Haushofer, dans ses réflexions sur le destin de la Chine, constate l’hétérogénéité physique de l’ancien espace impérial chinois: le désert de Gobi sépare la vaste zone de peuplement “han” des zones habitées par les peuples turcophones, à l’époque sous influence soviétique. Les montagnes du Tibet sont sous influence britannique depuis les Indes et cette influence constitue l’avancée la plus profonde de l’impérialisme thalassocratique vers l’intérieur des terres eurasiennes, permettant de surcroît de contrôler le “chateau d’eau” tibétain où les principaux fleuves d’Asie prennent leur source (à l’Ouest, l’Indus et le Gange; à l’Est, le Brahmapoutre/Tsangpo, le Salouen, l’Irawadi et le Mékong). La Mandchourie, disputée entre la Russie et le Japon, est toutefois majoritairement peuplée de Chinois et reviendra donc tôt ou tard chinoise.

Sympathie pour la Chine mais soutien au Japon

Haushofer, en dépit de ses sympathies pour la Chine, soutiendra le Japon dès le début de la guerre sino-japonaise (qui débute avec l’incident de Moukden en septembre 1931). Cette option nouvelle vient sans doute du fait que la Chine avait voté plusieurs motions contre l’Allemagne à la SdN, que tous constataient que la Chine était incapable de sortir par ses propres forces de ses misères. Le Japon apparaissait dès lors comme une puissance impériale plus fiable, capable d’apporter un nouvel ordre dans la région, instable depuis les guerres de l’opium et la révolte de Tai-Peh. Haushofer avait suivi la “croissance organique” du Japon mais celui-ci ne cadrait pas avec ses théories, vu sa nature hybride, à la fois continentale depuis sa conquête de la Mandchourie et thalassocratique vu sa supériorité navale dans la région. Très branché sur l’idée mackindérienne d’ “anneau maritime”, Haushofer estime que le Japon demeure une donnée floue sur l’échiquier international. Il a cherché des explications d’ordre “racial”, en faisant appel à des critères “anthropogéographiques” (Ratzel) pour tenter d’expliquer l’imprécision du statut géopolitique et géostratégique du Japon: pour lui, le peuple japonais est originaire, au départ, des îles du Pacifique (des Philippines notamment et sans doute, antérieurement, de l’Insulinde et de la Malaisie) et se sent plus à l’aise dans les îles chaudes et humides que sur le sol sec de la Mandchourie continentale, en dépit de la nécessité pour les Japonais d’avoir à disposition cette zone continentale afin de “respirer”, d’acquérir sur le long terme, ce que Haushofer appelle un “Atemraum”, un espace de respiration pour son trop-plein démographique.

L’Asie orientale est travaillée, ajoute-t-il, par la dynamique de deux “Pan-Ideen”, l’idée panasiatique et l’idée panpacifique. L’idée panasiatique concerne tous les peuples d’Asie, de la Perse au Japon: elle vise l’unité stratégique de tous les Etats asiatiques solidement constitués contre la mainmise occidentale. L’idée panpacifique vise, pour sa part, l’unité de tous les Etats riverains de l’Océan Pacifique (Chine, Japon, Indonésie, Indochine, Philippines, d’une part; Etats-Unis, Mexique, Pérou et Chili, d’autre part). On retrouve la trace de cette idée dans les rapports récents ou actuels entre Etats asiatiques (surtout le Japon) et Etats latino-américains (relations commerciales entre le Mexique et le Japon, Fujimori à la présidence péruvienne, les théories géopolitiques et thalassopolitiques panpacifiques du général chilien Pinochet, etc.). Pour Haushofer, la présence de ces deux idées-forces génère un espace fragilisé (riche en turbulences potentielles, celles qui sont à l’oeuvre actuellement) sur la plage d’intersection où ces idées se télescopent. Soit entre la Chine littorale et les possessions japonaises en face de ces côtes chinoises. Tôt ou tard, pense Haushofer, les Etats-Unis utiliseront l’idée panpacifique pour contenir toute avancée soviétique en direction de la zone océanique du Pacifique ou pour contenir une Chine qui aurait adopté une politique continentaliste et panasiatique. Haushofer manifeste donc sa sympathie à l’égard du panasiatisme. Pour lui, le panasiatisme est “révolutionnaire”, apportera un réel changement de donne, radical et définitif, tandis que le panpacifisme est “évolutionnaire”, et n’apportera que des changements mineurs toujours susceptibles d’être révisés. Le Japon, en maîtrisant le littoral chinois et une bonne frange territoriale de l’arrière-pays puis en s’opposant à toute ingérence occidentale dans la région, opte pour une démarche panasiatique, ce qui explique que Haushofer le soutient dans ses actions en Mandchourie. Puis en fera un élément constitutif de l’alliance qu’il préconisera entre la Mitteleuropa, l’Eurasie (soviétique) et le Japon/Mandchourie orientant ses énergies vers le Sud.

Toutes ces réflexions indiquent que Haushofer fut principalement un géopolitologue spécialisé dans le monde asiatique et pacifique. La lecture de ses travaux sur ces espaces continentaux et maritimes demeure toujours aujourd’hui du plus haut intérêt, vu les frictions actuelles dans la région et l’ingérence américaine qui parie, somme toute, sur une forme actualisée du panpacifisme pour maintenir son hégémonie et contenir une Chine devenue pleinement panasiatique dans la mesure où elle fait partie du “Groupe de Shanghai” (OCS), tout en orientant vers le sud ses ambitions maritimes, heurtant un Vietnam qui s’aligne désormais sur les Etats-Unis, en dépit de la guerre atroce qui y a fait rage il y a quelques décennies. On n’oubliera pas toutefois que Kissinger, en 1970-72, avait parié sur une Chine maoïste continentale (sans grandes ambitions maritimes) pour contenir l’URSS. La Chine a alors eu une dimension “panpacifiste” plutôt que “panasiatique” (comme l’a souligné à sa manière le général et géopolitologue italien Guido Giannettini). Les stratégies demeurent et peuvent s’utiliser de multiples manières, au gré des circonstances et des alliances ponctuelles.

Réflexions sur l’Inde

Reste à méditer, dans le cadre très restreint de cet article, les réflexions de Haushofer sur l’Inde. Si l’Inde devient indépendante, elle cessera automatiquement d’être un élément essentiel de l’ “anneau” pour devenir une pièce maîtresse du dispositif continentaliste/panasiatique. Le sous-continent indien est donc marqué par une certaine ambivalence: il est soit la clef de voûte de la puissance maritime britannique, reposant sur la maîtrise totale de l’Océan Indien; soit l’avant-garde des puissances continentales sur le “rimland” méridional de l’Eurasie et dans la “Mer du Milieu” qu’est précisément l’Océan Indien. Cette ambivalence se retrouve aujourd’hui au premier plan de l’actualité: l’Inde est certes partie prenante dans le défi lancé par le “Groupe de Shanghai” et à l’ONU (où elle ne vote pas en faveur des interventions réclamées par l’hegemon américain) mais elle est sollicitée par ce même hegemon pour participer au “containment” de la Chine, au nom de son vieux conflit avec Beijing pour les hauteurs himalayennes de l’Aksai Chin en marge du Cachemire/Jammu et pour la question des barrages sur le Brahmapoutre et de la maîtrise du Sikkim. Haushofer constatait déjà, bien avant la partition de l’Inde en 1947, suite au départ des Britanniques, que l’opposition séculaire entre Musulmans et Hindous freinera l’accession de l’Inde à l’indépendance et/ou minera son unité territoriale ou sa cohérence sociale. Ensuite, l’Inde comme l’Allemagne (ou l’Europe) de la “Kleinstaaterei”, a été et est encore un espace politiquement morcelé. Le mouvement indépendantiste et unitaire indien est, souligne-t-il, un modèle pour l’Allemagne et l’Europe, dans la mesure, justement, où il veut sauter au-dessus des différences fragmentantes pour redevenir un bloc capable d’être pleinement “sujet de l’histoire”.

Voici donc quelques-unes des idées essentielles véhiculées par la “Zeitschrift für Geopolitik” de Haushofer. Il y a en a eu une quantité d’autres, parfois fluctuantes et contradictoires, qu’il faudra réexhumer, analyser et commenter en les resituant dans leur contexte. La tâche sera lourde, longue mais passionnante. La géopolitique allemande de Haushofer est plus intéressante à analyser dans les années 20, où elle prend tout son essor, avant l’avènement du national-socialisme, tout comme la mouvance nationale-révolutionnaire, plus ou moins russophile, qui cesse ses activités à partir de 1933 ou les poursuit vaille que vaille dans la clandestinité ou l’exil. Reste aussi à examiner les rapports entre Haushofer et Rudolf Hess, qui ne cesse de tourmenter les esprits. Albrecht Haushofer, secrétaire de la “Deutsche Akademie” et fidèle disciple de ses parents, résume en quelques points les erreurs stratégiques de l’Allemagne dont:

a) la surestimation de la force de frappe japonaise pour faire fléchir en Asie la résistance des thalassocraties;

b) la surestimation des phénomènes de crise en France avant les hostilités;

c) la sous-estimation de la durée temporelle avec laquelle on peut éliminer militairement un problème;

d) la surestimation des réserves militaires allemandes;

e) la méconnaissance de la psychologie anglaise, tant celle des masses que celle des dirigeants;

f) le désintérêt pour l’Amérique.

Albrecht Haushofer, on le sait, sera exécuté d’une balle dans la nuque par la Gestapo à la prison de Berlin-Moabit en 1945. Ses parents, arrêtés par les Américains, questionnés, seront retrouvés pendus à un arbre au fond du jardin de leur villa d’Hartschimmelhof, le 10 mars 1946. Karl Haushofer était malade, déprimé et âgé de 75 ans.

L’Allemagne officielle ne s’est donc jamais inspirée de Haushofer ni sous la République de Weimar ni sous le régime national-socialiste ni sous la Bundesrepublik. Néanmoins bon nombre de collaborateurs de Haushofer ont poursuivi leurs travaux géopolitiques après 1945. Leurs itinéraires, et les fluctuations de ceux-ci devrait pouvoir constituer un objet d’étude. De 1951 à 1956, la ZfG reparaît, exactement sous la même forme qu’au temps de Haushofer. Elle change ensuite de titre pour devenir la “Zeitschrift für deutsches Auslandswissen” (= “Revue allemande pour la connaissance de l’étranger”), publiée sous les auspices d’un “Institut für Geosoziologie und Politik”. Elle paraît sous la houlette d’un disciple de Haushofer, le Dr. Hugo Hassinger. En 1960, le géographe Adolf Grabowsky, qui a également fait ses premières armes aux côtés de Haushofer, publie, en n’escamotant pas le terme “géopolitique”, un ouvrage remarqué, “Raum, Staat und Geschichte – Grundlegung der Geopolitik” (= “Espace, Etat et histoire – Fondation de la géopolitique”). Il préfèrera parler ultérieurement de “Raumkraft” (de “force de l’espace”). Les ouvrages qui ont voulu faire redémarrer une géopolitique allemande dans le nouveau contexte européen sont sans contexte ceux 1) du Baron Heinrich Jordis von Lohausen, dont le livre “Denken in Kontinenten” restera malheureusement confiné aux cercles conservateurs, nationaux et nationaux-conservateurs, “politiquement correct” oblige, bien que Lohausen ne développait aucun discours incendiaire ou provocateur, et 2) du politologue Heinz Brill, “Geopolitik heute”, où l’auteur, professeur à l’Académie militaire de la Bundeswehr, ose, pour la première fois, au départ d’une position officielle au sein de l’Etat allemand, énoncer un programme géopolitique, inspiré des traditions léguées par les héritiers de Haushofer, surtout ceux qui, comme Fochler-Hauke ou Pahl, ont poursuivi une quête d’ordre géopolitique après la mort tragique de leur professeur et de son épouse. A tous d’oeuvrer, désormais, pour exploiter tous les aspects de ces travaux, s’étendant sur près d’un siècle.

Robert Steuckers,

Forest-Flotzenberg, juin 2012.

Bibliographie:

Hans EBELING, Geopolitik – Karl Haushofer und seine Raumwissenschaft 1919-1945, Akademie Verlag, 1994.

Karl HAUSHOFER, Grenzen in ihrer geographischen und politischen Bedeutung, Kurt Vowinckel Verlag, Berlin-Grunewald, 1927.

Karl HAUSHOFER u. andere, Raumüberwindende Mächte, B.G. Teubner, Leipzig/Berlin, 1934.

Karl HAUSHOFER, Weltpolitik von heute, Verlag Zeitgeschichte, Berlin, 1934.

Karl HAUSHOFER & Gustav FOCHLER-HAUKE, Welt in Gärung – Zeitberichte deutscher Geopolitiker, Verlag von Breitkopf u. Härtel, Leipzig, 1937.

Karl HAUSHOFER, Weltmeere und Weltmächte, Zeitgeschichte-Verlag, Berlin, 1937.

Karl HAUSHOFER, Le Japon et les Japonais, Payot, Paris, 1937 (préface et traduction de Georges Montandon).

Karl HAUSHOFER, De la géopolitique, FAYARD, Paris, 1986 (préface du Prof. Jean Klein; introduction du Prof. H.-A. Jacobsen).

Hans-Adolf JACOBSEN, Karl Haushofer, Leben und Werk, Band 1 & 2, Harald Boldt Verlag, Boppard am Rhein, 1979.

Rudolf KJELLEN, Die Grossmächte vor und nach dem Weltkriege, B. G. Teubner, Leipzig/Berlin, 1930.

Günter MASCHKE, “Frank B. Kellogg siegt am Golf – Völkerrechtgeschichtliche Rückblicke anlässlich des ersten Krieges des Pazifismus”, in Etappe, Nr. 7, Bonn, Oktober 1991.

Emil MAURER, Weltpolitik im Pazifik, Goldmann, Leipzig, 1942.

Armin MOHLER, “Karl Haushofer”, in Criticon, Nr. 56, Nov.-Dez. 1979.

Perry PIERIK, Karl Haushofer en het nationaal-socialisme – Tijd, werk en invloed, Aspekt, Soesterberg, 2006.

Robert STEUCKERS, “Les thèmes de la géopolitique et de l’espace russe dans la vie culturelle berlinoise de 1918 à 1945 – Karl Haushofer, Oskar von Niedermayer & Otto Hoetzsch”, in Nouvelles de Synergies européennes, n°57-58, Forest, août-octobre 2002 [recension de: Karl SCHLÖGEL, Berlin Ostbahnhof Europas – Russen und Deutsche in ihrem Jahrhundert, Siedler, Berlin, 1998].

Si assiste ad un nuovo inizio dei legami Pakistan-Russia con la prevista visita del presidente russo Vladimir Putin, citata dei media del Pakistan per i primi di ottobre; la prima visita di un presidente russo in Pakistan. Una cosa considerata improbabile, in passato, potrebbe presto diventare una realtà con le due parti che si battono per un nuovo inizio nei rapporti bilaterali. Anche se i media statali russi hanno messo in dubbio la visita di Putin, è ovvio che anche se la visita venisse annullata, un altro funzionario di alto livello, come il ministro degli Esteri, si recherà in visita in Pakistan.

Si assiste ad un nuovo inizio dei legami Pakistan-Russia con la prevista visita del presidente russo Vladimir Putin, citata dei media del Pakistan per i primi di ottobre; la prima visita di un presidente russo in Pakistan. Una cosa considerata improbabile, in passato, potrebbe presto diventare una realtà con le due parti che si battono per un nuovo inizio nei rapporti bilaterali. Anche se i media statali russi hanno messo in dubbio la visita di Putin, è ovvio che anche se la visita venisse annullata, un altro funzionario di alto livello, come il ministro degli Esteri, si recherà in visita in Pakistan.

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

Non ci si stancherà mai di raccomandare la lettura di Oswald Spengler (1880 – 1936), eclettico filosofo della storia tedesco e teorico del socialismo prussiano, le cui opere hanno riscosso successo e interesse negli ambiti più disparati, da Mussolini a Kissinger, dalla Germania di Weimar alla Russia contemporanea. Tra i vari motivi per cui risulta ancora oggi molto attuale, non possiamo non citare le sue ipotesi storiche riguardanti la Russia.

Non ci si stancherà mai di raccomandare la lettura di Oswald Spengler (1880 – 1936), eclettico filosofo della storia tedesco e teorico del socialismo prussiano, le cui opere hanno riscosso successo e interesse negli ambiti più disparati, da Mussolini a Kissinger, dalla Germania di Weimar alla Russia contemporanea. Tra i vari motivi per cui risulta ancora oggi molto attuale, non possiamo non citare le sue ipotesi storiche riguardanti la Russia.

La semaine dernière, j’ai écrit

La semaine dernière, j’ai écrit