dimanche, 14 février 2016

Soleil et lune / mâle et femelle

Soleil et lune / mâle et femelle

par Thomas Ferrier

Ex: http://thomasferrier.hautetfort.com

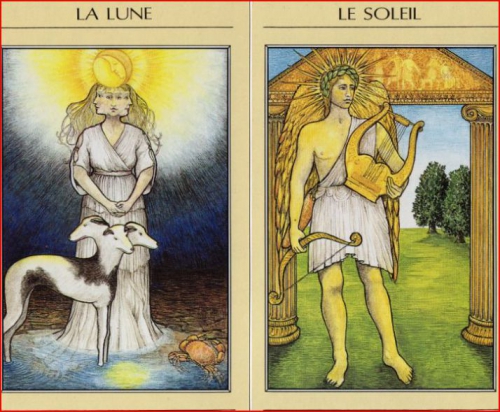

Les mythologies anciennes évoquent deux figures majeures, deux déités parmi les plus importantes, à savoir le Soleil et la Lune. En français, langue héritière du latin, il n’y a aucun doute. Soleil masculin, Lune féminine. Comme le Sol et la Luna romains. Pourtant ces deux astres, selon les peuples, ne sont pas associés au même sexe et c’est ce que je vais m’efforcer d’analyser dans cet article.

Chez les Indo-Européens indivis, la tribu des *Aryōs que j’évoquerai dans un prochain article, les choses sont assez simples. Le Soleil,*Sawel ou *Sawelyos), comme l’indique la forme finale en –os, est masculin, tandis que la lune, sous ses deux noms, *mens et *louksna (« la lumineuse »), est féminine. Le dieu du soleil est le fils du dieu du ciel et forme avec ses deux frères, le feu du ciel intermédiaire (foudre) et le feu terrestre, une triade. Ainsi en Grèce Apollon (substitut d’Hélios), Arès et Héphaïstos sont les trois fils de Zeus.

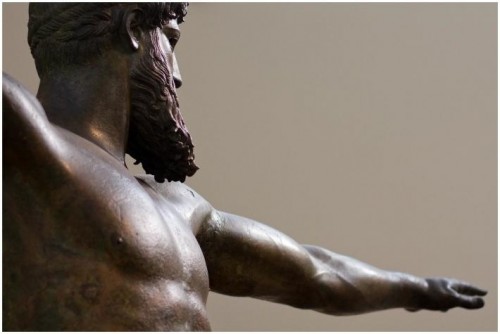

En Grèce, le soleil est représenté par au moins trois divinités, toutes masculines, à savoir Hélios lui-même, le Soleil personnifié, mais aussi son père, le titan Hypérion (« le très haut ») et Apollon, seul olympien au sens strict, surnommé Phoebos. De la même façon, la lune est associée à plusieurs déesses comme Selênê (*louksna) ou Mênê (*mens), mais aussi l’olympienne Artémis, déesse-ourse de la chasse, et la sombre magicienne Hécate. La lune est un astre mystérieux et inquiétant pour les anciens Grecs, à la différence du soleil souverain, dont la puissance est généralement bienfaitrice, même si parfois les rayons du soleil, qu’Apollon envoie grâce à son arc, sèment aussi la mort. En revanche, à Rome même, Sol et Luna sont des divinités très marginales, rapidement remplacées dans leur rôle céleste par Apollon et Diane.

Chez les Indo-Européens d’orient, et ce sans doute sous l’influence de la religion mésopotamienne, soleil et lune sont deux divinités masculines, ainsi Hvare et Mah en Iran ou encore Surya et Chandra Mas (*louksna *mens, pour la première fois associée). Les Arméniens par contre respectent bien le schéma indo-européen, avec le viril Arev, selon une variante du nom du soleil qu’on retrouve dans le sanscrit Ravi, et la douce Lusin (*louksna). Enfin, en Albanie aussi, on retrouve un soleil masculin (Dielli) et une lune féminine (Hëna).

En revanche, chez les peuples du nord de l’Europe, étrangement, le sexe de l’un et de l’autre s’est inversé, sauf chez les Celtes où ces deux divinités ont une place de toute façon si marginale qu’il est presque impossible de les identifier, remplacés par le dieu Belenos et sans doute la déesse Đirona. Chez les Germains, si Balder est l’Apollon scandinave, le soleil est une déesse (germanique Sunna, nordique Sol) alors que la lune est son frère (nordique Mani). De même, les Baltes possèdent une déesse solaire puissante (lituanienne Saulè) et un dieu lunaire aux accents guerriers (lituanien Menulis, letton Menuo). Cette étrange inversion s’explique peut-être par l’idée que le soleil du nord était davantage doux pour les hommes, mais on verra par la suite que cette hypothèse est douteuse.

Les Slaves quant à eux préfèrent maintenir une certaine ambiguïté. Si le soleil est clairement masculin, sous la forme du Khors (Хорс) d’origine sarmatique ou du Dazbog slave, alors que son nom neutre « solntse » ne désigne que l’astre et aucunement une divinité, la lune n’est pas nécessairement féminine. Messiats (Месяц) est une divinité qui peut apparaître aussi bien comme un dieu guerrier que comme une déesse pacifique.

La mythologie indo-européenne, malgré une inversion localisée dans le Nord-est de l’Europe, et une influence mésopotamienne évidente en Orient, a donc conservé l’idée d’un couple de jumeaux, le dieu du soleil et la déesse de la lune, tous deux nés de l’amour du ciel de jour et de la nuit (la Léto grecque, qui est aussi la Ratri indienne, déesse de la nuit).

En Egypte et à Sumer, pays où la chaleur du soleil pouvait être écrasante, le soleil est clairement une divinité mâle, mais la lune n’est pas davantage envisagée comme son opposé. L’Egypte dispose ainsi de plusieurs dieux solaires de première importance, comme Râ et Horus (Heru), et aussi de leurs multiples avatars, comme Ammon, le soleil caché, et Aton, le soleil visible. Le Soleil a même une épouse et parèdre, Rât. Il est le dieu suprême, alors que le ciel est féminin (Nout) et la terre est masculine (Geb), inversion étrange qu’on ne retrouvera pas ailleurs. La Lune est elle aussi masculine. C’est le dieu Chonsu, au rôle religieux des plus limités. De même les Sumériens disposent de deux divinités masculines, en la personne d’Utu, le Soleil comme astre de justice, et Nannar, la Lune.

Lorsque les peuples sémitiques quittèrent leur foyer d’Afrique de l’Est ou de la pointe sud-ouest de l’Arabie, leur mythologie rencontra celle des Mésopotamiens. A l’origine, le Soleil chez les Sémites est une déesse du nom de *Śamšu alors que la Lune est masculine, *Warihu. Chez un peuple qu’on associe à un environnement semi-désertique, c’est assez surprenant. Lorsque les Sémites envahirent Sumer, ils adaptèrent leur panthéon à celui des indigènes. Si la lune resta masculine sous la forme du dieu Sîn, dont l’actuel Sinaï porte le nom, le soleil devint également masculin. A l’Utu sumérien succéda le Shamash babylonien, dans son rôle identique de dieu qui voit tout et juge les hommes. Mais en Canaan et chez les Arabes, « la » Soleil survécut. Shapash était la déesse ouest-sémitique du soleil, présente aussi bien chez les anciens Judéens que dans le reste de Canaan et jusqu’à Ugarit, et Shams la déesse sud-sémitique, présente encore à l’époque de Muhammad dans tout le Yémen.

Lorsque les peuples sémitiques quittèrent leur foyer d’Afrique de l’Est ou de la pointe sud-ouest de l’Arabie, leur mythologie rencontra celle des Mésopotamiens. A l’origine, le Soleil chez les Sémites est une déesse du nom de *Śamšu alors que la Lune est masculine, *Warihu. Chez un peuple qu’on associe à un environnement semi-désertique, c’est assez surprenant. Lorsque les Sémites envahirent Sumer, ils adaptèrent leur panthéon à celui des indigènes. Si la lune resta masculine sous la forme du dieu Sîn, dont l’actuel Sinaï porte le nom, le soleil devint également masculin. A l’Utu sumérien succéda le Shamash babylonien, dans son rôle identique de dieu qui voit tout et juge les hommes. Mais en Canaan et chez les Arabes, « la » Soleil survécut. Shapash était la déesse ouest-sémitique du soleil, présente aussi bien chez les anciens Judéens que dans le reste de Canaan et jusqu’à Ugarit, et Shams la déesse sud-sémitique, présente encore à l’époque de Muhammad dans tout le Yémen.

Un dieu soleil et une déesse lune chez les Indo-Européens, une déesse soleil et un dieu lune chez les Sémites, comme d’ailleurs chez les peuples Turcs et Finno-ougriens, et sans doute chez les peuples nomades en général, un soleil et une lune tous deux masculins en Egypte et à Sumer, voilà une situation bien complexe. Pourquoi attribuer à l’un ou à l’autre un genre en particulier ?

On comprend bien que la lune, liée à des cycles, puisse être associée à la femme, elle-même soumise à un cycle menstruel, terme qui rappelle d’ailleurs justement le nom indo-européen de la lune (*mens). Et de même le soleil, astre ardent qui brûle la peau de celui qui ne s’en protège pas, qui voit tout et qui sait tout, est logiquement masculin. Mais ce raisonnement ne vaut que pour les Indo-Européens. L’idée d’une lune féminine leur est propre, alors qu’elle est masculine partout ailleurs, de l’Egypte jusqu’à l’Inde.

Thomas FERRIER (LBTF/Le Parti des Européens)

12:31 Publié dans Traditions | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : soleil, culte solaire, lune, culte lunaire, mythologie, indo-européens, thomas ferrier |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

lundi, 01 février 2016

Du mot proto-indo-européen *deywos

Du mot proto-indo-européen *deywos

par Thomas Ferrier

Ex: http://thomasferrier.hautetfort.com

Qu’est-ce qu’un *deywos, mot qui a abouti au latin deus et au français « dieu » ? D’autres termes pour désigner les divinités ont été employés par les Indo-Européens indivis, à l’instar de *ansus, « esprit divin » [scandinave Ass, indien Asura) ou de *dhesos, « celui qui est placé (dans le temple) » [grec theos] et bien sûr le terme germanique *gutaz désignait « celui qu’on invoque », mais *deywos aura été le plus courant et le mieux conservé puisqu’on le retrouve à peu près partout (gaulois devos, germano-scandinave tyr, balte dievas, sanskrit devas, latin deus, iranien daeva).

La racine de *deywos est bien connue, et on la retrouve dans le nom de *dyeus, le « ciel diurne », à la fois phénomène physique et divinité souveraine. On peut la traduire par « céleste » aussi bien que par « diurne » mais aussi par « émanation de *dyeus ».

La divinité suprême *Dyeus *Pater est en effet l’époux d’une parèdre du nom de *Diwni (« celle de *dyeus ») qui est le nom marital de la déesse de la terre, son épouse naturelle, formant le couple fusionnel dyavaprithivi dans l’Inde védique. Les *Deywôs sont donc les fils de *Dyeus, tout comme les *Deywiyês (ou *Deywâs) sont ses filles. C’est leur façon de porter le nom patronymique de leur divin géniteur.

Les *Deywôs sont donc par leur nom même les enfants du ciel, ce qui place leur existence sur un plan astral, l’ « enclos des dieux » (le sens même du mot *gherdhos qu’on retrouve dans Asgard, le royaume divin des Scandinaves) étant situé sur un autre plan que le monde des hommes mais placé systématiquement en hauteur, généralement à la cime de la plus haute montagne ou de l’arbre cosmique, ou au-delà de l’océan, dont la couleur est le reflet du ciel bleu, dans des îles de lumière (Avallon, Îles des Bienheureux…).

Mais ils forment aussi une sainte famille, autour du père céleste et de la mère terrestre, l’un et l’autre régnant dans un royaume de lumière invisible aux yeux des hommes.

Toutefois, le ciel diurne ne s’oppose au ciel de nuit que dans une certaine mesure. Sous l’épiclèse de *werunos, le dieu « du vaste monde » [grec Ouranos, sanscrit Varuna], *Dyeus est aussi le dieu du ciel en général, les étoiles étant depuis toujours les mânes des héros morts, souvenir que les Grecs lièrent au mythe d’Astrée, déesse des étoiles et de la justice, qui abandonna le monde en raison des pêchés des hommes. Astrée elle-même n’était autre que la déesse *Stirona indo-européenne que les Celtes conservèrent sous le nom de Đirona (prononcer « Tsirona ») et que les Romains associèrent à Diane.

Quant à la parèdre de *Dyeus, on la retrouve sous les noms de Diane et de Dea Dia à Rome, de Dziewona en Pologne pré-chrétienne et de Dionê en Grèce classique, celle-là même qu’on donne pour mère d’Aphrodite. De même la déesse de l’aurore (*Ausos) est dite « fille de *Dyeus » [*dhughater *Diwos], terme qu’on retrouve associé à Athéna mais aussi plus rarement à Aphrodite.

*Diwni, l’épouse du jour, devient *Nokwts, la nuit personnifiée. Le *Dyeus de jour cède alors la place au *Werunos de nuit. Tandis que les autres *Deywôs dorment, *Dyeus reste éveillé. L’idée d’un dieu du jour et de la nuit, donc aux deux visages, est à rapprocher du Janus romain, dieu des commencements, époux alors de la déesse de l’année *Yera (Héra) ou de la nouvelle année (Iuno).

Thomas FERRIER (Le Parti des Européens)

19:45 Publié dans Traditions | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : tradition, mythologie, dieux, paganisme, zeus, indo-européens |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

lundi, 18 janvier 2016

Sol Invictus et le monothéisme solaire

![Fludd-SublimeSun(744x721)[1].jpg](http://euro-synergies.hautetfort.com/media/02/02/2842203225.jpg)

Sol Invictus et le monothéisme solaire

par Thomas Ferrier

Ex: http://thomasferrier.hautetfort.com

Racines Dans la tradition égyptienne ancienne, le dieu le plus important du panthéon était le Soleil, qui était honoré sous différents noms selon les cités, mais qui portait dans toute l’Egypte le nom de Rê. En tant qu’Atoum-Rê, il apparaissait comme le dieu créateur du monde et sous les traits d’Amon-Rê comme un dieu souverain. Rê était également appelé Horus (Heru), sous la forme d’Horus l’ancien comme sous celle du fils d’Osiris et d’Isis. Le dieu Horus, son avatar sur la terre, aurait même guidé le peuple égyptien, à l’époque où ses ancêtres venaient d’Afrique du nord, sur cette nouvelle terre noire (Kemet) qui finit par porter son nom.

Dans la tradition égyptienne ancienne, le dieu le plus important du panthéon était le Soleil, qui était honoré sous différents noms selon les cités, mais qui portait dans toute l’Egypte le nom de Rê. En tant qu’Atoum-Rê, il apparaissait comme le dieu créateur du monde et sous les traits d’Amon-Rê comme un dieu souverain. Rê était également appelé Horus (Heru), sous la forme d’Horus l’ancien comme sous celle du fils d’Osiris et d’Isis. Le dieu Horus, son avatar sur la terre, aurait même guidé le peuple égyptien, à l’époque où ses ancêtres venaient d’Afrique du nord, sur cette nouvelle terre noire (Kemet) qui finit par porter son nom.

C’est la barque de Rê qui garantissait chaque jour l’ordre cosmique contre les forces de destruction et de chaos incarnées par le serpent Apep (« Apophis »). A sa proue, le dieu orageux Set combattait le dit serpent, avant que la tradition populaire tardive ne finisse par le confondre avec lui et n’en fasse plus que le meurtrier d’Osiris.

L’importance du culte solaire fut telle que le roi Amenhotep IV, plus connu sous celui d’Akhenaton, en fit son culte unique et fut le premier à créer un monothéisme solaire lié à sa personne, honorant le disque solaire divinisé (Aton). Les seuls prêtres et intercesseurs d’Aton vis-à-vis des hommes étaient le pharaon lui-même et son épouse Nefertiti. Son culte s’effondra à sa mort et les prêtres d’Amon veillèrent à ce que son nom disparaisse des inscriptions.

Mais en revanche dans la tradition indo-européenne, dont Grecs et Romains (notamment) seront les héritiers, le dieu du soleil est un dieu parmi d’autres et jamais le premier. Aux temps de l’indo-européanité indivise, ce dieu se nommait *Sawelyos et monté sur un char tiré par des chevaux blancs, il tournait autour de l’astre portant son nom. Le dieu suprême était son père *Dyeus, le dieu du ciel et de la lumière. Parmi les fils de *Dyeus qu’on nommait les *Deywôs (les « dieux »), trois étaient liés au feu, en conformité avec le schéma dumézilien des trois fonctions et sa version cosmique analysée par Haudry. Il y avait en effet le feu céleste (Soleil), le feu du ciel intermédiaire (Foudre) et le feu terrestre (Feu). De tous les fils de *Dyeus, le plus important était celui de l’orage et de la guerre (*Maworts), qui parfois devint le dieu suprême chez certains peuples indo-européens (chez les Celtes avec Taranis, chez les Slaves avec Perun, chez les Indiens avec Indra). Le dieu du soleil était davantage lié aux propriétés associées à l’astre, donc apparaissait comme un dieu de la beauté et aussi de la médecine. Ce n’était pas un dieu guerrier.

A Rome même, le dieu Sol surnommé Indiges (« Indigène ») était une divinité mineure du panthéon latin. Il était né le 25 décembre, à proximité du solstice d’hiver. Dans ce rôle solaire, il était concurrencé par le dieu de l’impulsion solaire, Saturne, dont le nom est à rapprocher du dieu indien Savitar, avant d’être abusivement associé au Cronos grec.

En Grèce enfin, selon un processus complexe, les divinités du soleil, de la lune et de l’aurore se sont multipliées. L’Aurore était donc à la fois Eôs, l’Aurore personnifiée, mais aussi Athéna dans son rôle de déesse de l’intelligence guerrière et Aphrodite dans celui de déesse de l’amour. Et en ce qui concerne le Soleil, il était à la fois Hêlios, le fils d’Hypérion (qui n’était autre que lui-même), et Apollon, le dieu de la lumière, des arts et de la médecine. Cette confusion entre ces deux dieux fut constamment maintenue durant toute l’antiquité.

Evolution. IIIème siècle après J.C. L’empire romain est en crise. A l’est, les Sassanides, une Perse en pleine renaissance qui rêve de reconstituer l’empire de Darius. Au nord, les peuples européens « barbares » poussés à l’arrière par des vagues asiatiques et qui rêvent d’une place au soleil italique et/ou balkanique.

IIIème siècle après J.C. L’empire romain est en crise. A l’est, les Sassanides, une Perse en pleine renaissance qui rêve de reconstituer l’empire de Darius. Au nord, les peuples européens « barbares » poussés à l’arrière par des vagues asiatiques et qui rêvent d’une place au soleil italique et/ou balkanique.

Le principat, qui respectait encore les apparences de la république, tout en ayant tous les traits d’un despotisme éclairé, a explosé. Place au dominat. Victoire de la conception orientale du pouvoir sur la vision démocratique indo-européenne des temps anciens. L’empereur n’est plus un héros en devenir (divus) mais un dieu incarné (deus). Il est le médiateur de la puissance céleste et des hommes, à la fois roi de fait et grand pontife. Le polythéisme romain était pleinement compatible avec une conception républicaine du monde, comme l’a montré Louis Ménard. Empereur unique, dieu unique.

Si le christianisme comme religion du pouvoir d’un seul était encore trop marginal pour devenir la religion de l’empereur, un monothéisme universaliste s’imposait naturellement dans les têtes. Quoi de plus logique que de représenter l’Un Incréé de Plotin par le dieu du soleil, un dieu présent dans l’ensemble du bassin méditerranéen et donc apte à unir sous sa bannière des peuples si différents. Mondialisme avant la lettre. Cosmopolitisme d’Alexandre. Revanche des Graeculi sur les vrais Romani, d’Antoine sur Octavien.

C’est ainsi que naquit un monothéisme solaire autour du nom de Sol Invictus, le « Soleil Invaincu » et/ou le « Soleil invincible ». Le dieu syrien El Gabal, les dieux solaires égyptiens et l’iranien Mithra, enfin le pâle Sol Indiges, le froid Belenos et Apollon en un seul. Le monothéisme solaire d’Elagabale, mort pour avoir eu raison trop tôt, de Sévère Alexandre, qui ouvrit même son panthéon à Jésus, puis d’Aurélien, s’imposa. Certes Sol n’était pas l’unique « deus invictus ». Jupiter et Mars furent aussi qualifiés de tels, et il est vrai que de tous les dieux romains, Mars était le seul légitime en tant que déité de la guerre à pouvoir porter ce nom.

En réalité, « Sol Invictus » fut l’innovation qui facilita considérablement au final la victoire du christianisme. Constantin, qui était un dévot de ce dieu, accepta de considérer Jésus Christ, que des auteurs chrétiens habiles désignèrent comme un « soleil de justice » (sol iustitiae) comme une autre expression de ce même dieu. Le monothéisme « païen » et solaire de Constantin, épuré de tout polythéisme, comme sous Akhenaton, et le monothéisme chrétien fusionnèrent donc naturellement. Le jour du soleil fut dédié à Jésus, tout comme celui-ci désormais fut natif du 25 décembre. Jésus se vit représenté sous les traits d’un nouvel Apollon, aux cheveux blonds, à la fois Dieu incarné et homme sacrifié pour le salut de tous.

Au lieu de s’appuyer sur le polythéisme de leurs ancêtres, les empereurs romains, qui étaient tous des despotes orientaux, à l’instar d’un Dioclétien qui exigeait qu’on s’agenouille devant lui, à l’instar d’un shah iranien, voulurent faire du christianisme contre le christianisme. Dioclétien élabora une théologie complexe autour de Jupiter et d’Hercule. Le héros à la massue devint une sorte de Christ païen, de médiateur, qui s’était sacrifié sur le mont Oeta après avoir vaincu les monstres qui terrifiaient l’humanité et avait ainsi accédé à l’immortalité.

Et l’empereur Julien lui-même se fit un dévot du Soleil Invincible, sans se rendre compte un instant qu’il faisait alors le plus beau compliment au monothéisme oriental qu’il pensait combattre. Il osa dans ses écrits attribuer la naissance de Rome non au dieu Mars mais à Hélios apparu dans un rôle fonctionnel guerrier. Le monothéisme solaire a pourtant permis au christianisme de s’imposer, à partir du moment où l’empereur a compris que l’antique polythéisme était un obstacle moral à l’autocratie. Constantin alla simplement plus loin qu’Aurélien dans sa volonté d’unir religieusement l’empire. Jesus Invictus devint le dieu de l’empire romain.

Le monothéisme autour de Sol Invictus, loin d’être la manifestation d’une résistance païenne, était au contraire la preuve de la victoire des valeurs orientales sur une Rome ayant trop négligé son héritage indo-européen en raison d’un universalisme suicidaire. Cela nous rappelle étrangement la situation de l’Europe contemporaine.

Thomas FERRIER (PSUNE/LBTF)

Note: Mithra à l’origine n’est pas un dieu solaire. C’était la fonction de l’ange « adorable » zoroastrien Hvar (Khorsid en moyen-perse). Il incarnait au contraire le dieu des contrats, de la parole donnée et de la vérité, à l’instar du Mitra indien. Par la suite, il récupéra des fonctions guerrières aux dépens d’Indra désormais satanisé (mais réapparu sous les traits de l’ange de la victoire, Verethragna). Enfin il finit par incarner le Soleil en tant qu’astre de justice. Le Mithras « irano-romain », évolution syncrétique ultérieure, conserva les traits solaires du Mithra iranien tardif. Il fut également associé au tétrascèle solaire (qualifiée de roue de Mithra, Garduneh-e Mehr, ou de roue du Soleil, Garduneh-e Khorsid) qui fut repris dans l’imagerie christique avant d’être utilisé deux millénaires plus tard par un régime totalitaire.

00:05 Publié dans Traditions | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : paganisme, culte solaire, soleil, sol invictus, mythologie, astres, traditions |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

vendredi, 18 décembre 2015

Il sole e gli Dei

|

|

|

| Il sole e gli Dei | |

| di Ass. Cultural "Uomini Liberi Uomini Dei" | |

| Ex: http://www.insorgente.com | |

Nel sincretismo delle religioni del passato, il concetto di Dio unico prese una forma così generalizzata, tale da disconoscere talvolta il suo nome e la sua reale identità. In altre parole oggi crediamo, almeno nella maggioranza dell'umanità, in un unico Dio solamente perché tutti gli altri sono semplicemente scomparsi dalla scena divina, per ragioni di una cruenta realtà storica che vinse sulla ragione e la razionalità dell'uomo. Amon Ra, il Dio supremo. Semplicemente Ra, divinità creatrice, custode di un pantheon egizio di Dei ognuno dei quali aveva un suo compito preciso, quello di educare ed accompagnare la spiritualità della civiltà egiziana a considerare l'importanza della vita, della natura e degli astri che influenzavano nell'uomo ogni sensazione di contatto divino tra cielo e terra. Dopo qualche migliaio di anni, Ra e tutti gli altri Dei lentamente scomparvero dalla scena religiosa, ed emerse Aton, la proposta di un Dio che manifestava tutta la sua sacralità nella materia stessa. Aton, l'adorazione del disco solare stesso proposto dal faraone Akenaton quasi ad enfatizzare un concetto di divinità monoteista che verrà assorbita secoli più tardi dalle principali religioni abramitiche che conosciamo, ognuna delle quali con una propria teologia personalizzata. Quello che non comprendiamo, è la presunzione delle tre principali religioni monoteiste e cioè che il loro Dio esiste, tutti gli altri no. Per il cristianesimo, l'ebraismo e l'islam, tutti gli altri Dei e le loro antiche tradizioni, i loro culti, sono da considerarsi semplicemente idoli di un passato remoto non solo dimenticato, ma sciocco da ricordare. Per la maggioranza del mondo che presume l'esistenza di un solo Dio, tutto è scontato. L'unica verità marcia a favore di un'ottusità a senso unico e chi la pensa al contrario è subdolo e sacrilego. Chi marcia al contrario è il solito “pagano” rozzo, intorpidito dalla realtà e da chissà quali sciocche e superate credenze popolari. Ma quale realtà? Nel medioevo, la maggioranza delle persone credevano che la terra fosse piatta. Si sbagliavano tremendamente di grosso. Alle soglie del terzo millennio è inutile continuare a nascondere che il cristianesimo nella rappresentazione della propria immagine divina quale Gesù Cristo abbia attinto per molti aspetti da millenarie tradizioni religiose già esistenti, reinventando l'immagine di culti presenti da migliaia di anni sulla scena politica e religiosa di popolazioni antiche. Se un Dio supremo esiste, dategli pure un nome e un'identità, ma ricordatevi che anche gli Dei esistono anche se a un certo punto della storia vennero semplicemente sommersi e rinnegati dal buon senso e dalla ragione. Almeno un centinaio di passaggi senza equivoco o allegoria possibile dimostrano la loro esistenza nella bibbia stessa.. Per esempio eccone tre: Giosuè 24,2 “Giosuè disse a tutto il popolo: «Dice il Signore, Dio d'Israele: I vostri padri, come Terach padre di Abramo e padre di Nacor, abitarono dai tempi antichi oltre il fiume e servirono altri Dei”. E' inutile continuare a rinnegare la storia, l'archeologia e una dottrina biblica veicolata che a volte racconta di più di ciò che si vuole far credere. Subdolo sarebbe continuare a nascondere che la data della nascita divina del Cristo è puramente simbolica e mitologica, collegata al concetto di resurrezione del sole di ogni popolazione antica da nord a sud, da est a ovest del mondo che muterà in un definitivo concetto di resurrezione dell'anima, quando in qualche modo il Dio del sole e della luce o la suprema identità comunicativa diventa un tutt'uno con il faraone, (l'uomo) l'incarnazione del Dio disceso sulla terra, il soter (salvatore) di Platone della Grecia antica. La resurrezione del sole o solstizio invernale fu e dovrebbe esserlo ancora, semplicemente una festa di luce maggiore, che assieme all'equinozio di primavera annunciava ad ogni popolo della nascita per volere divino della natura e della vita e venne in un secondo momento assoggettata alla nascita simbolica di molti Dei dell'antichità. Per comprendere cosa rappresentasse il solstizio invernale per gli antichi,vi rimandiamo all'articolo che trovate nella sezione cultura del nostro sito datato 21-12-2012 : “Ma cosa è il Solstizio?” Per capire invece meglio quanto la misticità del sole emergesse dai principali culti egiziani, europei, orientali, greco romani, basterebbe soltanto accertarsi come il sole nascente venisse rappresentato sempre alla sommità o dietro il capo di ogni Dio o Dea maggiore che prometteva luce e verità es. Ra, Hathor, Iside (la vergine col bambino), Krishna, Mitra e molti altri. Per rimarcare come il sole venisse associato per ovvie ragioni alla sacralità degli Dei, troviamo uno dei mille esempi di coniugazione nel monolito di Commagene in Turchia (ex provincia romana) dove gli Dei Apollo, Elio e Demetrio sono scolpiti nella pietra e il sole viene evidenziato, raffigurato sovrastante di essi. La classica immagine dello stesso Gesù, se ci fate caso, è spesso rappresentata con un sole splendente alle spalle. I santi più importanti per il cristianesimo vengono rappresentati sempre con un'aureola solare alla nuca. Come potete constatare nella foto in anteprima, (mitra o mitria papale medioevale museo di Salisburgo) la sacralità del sole nacque associata al cristianesimo stesso e nel medioevo era ancora molto viva la sua rappresentazione attraverso e non solo le vesti papali. Il sole “cristiano” veniva solitamente raffigurato da uno o più soli d'oro sulle facciate del sacro cappello mentre tutta la sua misticità ritornava a tradizioni lontanissime, quando fu tempo che correnti filosofiche religiose e rituali Esseni si fondessero nel nascente cristianesimo. Così in un passo ci ricorda lo storico Giuseppe Flavio di alcuni rituali Esseni precursori del cristianesimo: Libro II:128 Il culto del sole racconta il suo massimo splendore fin dalla nascita del mondo. Il sole, sia esso di creazione divina o naturale possibile, si propone omaggio dell'universo alla vita dell'uomo, della terra e del nostro sistema solare. Ogni occasione era buona per un ringraziamento alla natura che collegava una cultura universale alla luce solare, alla sua quotidiana nascita o resurrezione e che, in qualunque modo possibile, ogni civiltà trovò motivo di personale lode. A questo punto due riflessioni per le conclusioni. Innanzitutto quando si parla di culto solare o solstizio, sarebbe ora di finirla di tacciarlo come evento “pagano”. Ma che vuol dire pagano? Oggi nella società manca l'informazione corretta del “sacrilego” significato. Il termine viene forgiato con l'avvento del cristianesimo e si diffonde come una sorta di suffisso denigratorio nel generalizzare religioni praticate in precedenza al culto di Cristo. Ma se nel cristianesimo, come abbiamo visto, il culto del sole o meglio dire in questo caso la nascita del sole viene simbolicamente assimilata e associata alla nascita del Cristo, tra l'altro ripreso per ragioni storiche dalla nascita di Mitra il 25 dicembre, è giusto secondo voi considerare il solstizio un evento volgarmente ancora detto e denigrato di natura pagana? Non sarebbe forse meglio dire semmai, di natura divina? Il centro dell'universo spirituale dell'uomo è inconfutabilmente iniziato per ovvie ragioni dall'adorazione del sole e le religioni lo “adottarono” come naturale, fondamentale simbologia di vita e di rinascita. Non comprendere il significato, l'importanza della nostra unica fonte di salvezza che rimane ancora oggi innegabilmente il sole, è per noi semplicemente una questione di superficialità e stupidità umana. Buon solstizio a tutti, quest'anno astronomicamente parlando, sarà il 21 dicembre alle ore 23,03. Ass. Culturale “Uomini Liberi Uomini Dei” |

|

00:25 Publié dans Traditions | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : traditions, solstice d'hiver, mythes solaires, mythologie, cultes solaires, soleil |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

dimanche, 24 mai 2015

Le dieu cornu des Indo-Européens

Le dieu cornu des Indo-Européens

par Thomas Ferrier

Ex: http://thomasferrier.hautetfort.com

De toutes les figures divines du panthéon proto-indo-européen, celle du dieu « cornu » est la plus complexe et la moins analysée. Elle est pourtant essentielle, même si son importance n’est pas comparable à celle du dieu de l’orage, dont il est souvent le compagnon de lutte mais parfois aussi l’adversaire. On le retrouve chez presque tous les peuples indo-européens, à l’exception notable des Germains même si, on le verra, il est possible d’y retrouver sa trace. Son nom originel était sans doute *Pauson, « celui qui guide ». Représenté avec deux cornes, il fut alors surnommé chez certains peuples le dieu « cornu ».

Chez les Grecs, l’équivalent en toutes choses de *Pauson était le dieu Pan. Son nom, qui ne signifiait pas « tout », comme une étymologie populaire le proposait, dérive directement de son ancêtre indo-européen. Pan est justement représenté cornu avec des pieds de bouc. Il était le dieu des troupeaux, qu’il protégeait contre les loups. C’est là un de ses rôles les plus anciens. On le dit natif d’Arcadie, une région de collines où il était très sollicité par les bergers du Péloponnèse. Son nom a également donné celui de « panique », car on dotait Pan de la capacité d’effrayer les ennemis.

Pan n’était pas le fils de n’importe quel dieu. Il était celui d’Hermès avec lequel il se confond. Comme souvent chez les Grecs, un même dieu indo-européen pouvait prendre plusieurs formes. On confondait ainsi Eôs et Aphrodite ou encore Hélios et Apollon. Le premier portait le nom originel, le second celui d’une épiclèse devenue indépendante. Pan et Hermès étaient dans le même cas de figure. Hermès disposait de la plupart des rôles auparavant dévolus à celui dont les Grecs feront paradoxalement le fils. Il était le dieu des chemins et lui aussi conducteur des troupeaux. On raconte que dans ses premières années il déroba le troupeau dont Apollon avait la garde. C’était le dieu des voleurs et le dieu qui protégeait en même temps contre le vol. Il était aussi le gardien des frontières, d’où sa représentation sous forme d’une borne, tout comme le dieu latin Terminus. Il était également le dieu du commerce et de l’échange, le protecteur des marchands. Enfin, Hermès était un dieu psychopompe, conduisant les âmes des morts aux Champs Elyséens ou dans le sombre royaume d’Hadès.

En Inde, l’homologue de Pan était le dieu Pusan. A la différence de Pan, Pusan avait conservé l’intégralité de ses prérogatives. Il était dieu psychopompe, emmenant les âmes chez Yama. Il protégeait les voyageurs contre les brigands et les animaux sauvages. Ce dieu offrait à ceux qu’il appréciait sa protection et la richesse symbolisée par la possession de troupeaux. Son chariot était conduit par des boucs, là encore un animal associé au Pan grec.

Le dieu latin Faunus, qui fut associé par la suite non sans raison avec Pan, se limitait à protéger les troupeaux contre les loups, d’où son surnom de Lupercus (sans doute « tueur de loup »), alors que Mars était au contraire le protecteur de ces prédateurs. Son rôle était donc mineur. Le dieu des chemins était Terminus et le dieu du commerce, lorsque les Romains s’y adonnèrent, fut Mercure, un néologisme à base de la racine *merk-. Faunus était également le dieu des animaux sauvages auprès de Silvanus, dieu des forêts.

Enfin, le dieu lituanien Pus(k)aitis était le dieu protecteur du pays et le roi des créatures souterraines, avatar déchu d’une grande divinité indo-européenne mais qui avait conservé son rôle de gardien des routes et donc des frontières. Les autres peuples indo-européens, tout en conservant la fonction de ce dieu, oublièrent en revanche son nom. Les Celtes ne le désignèrent plus que par le nom de Cernunnos, le dieu « cornu ». En tant que tel, il était le dieu de la richesse de la nature, le maître des animaux sauvages comme d’élevage, le dieu conducteur des morts et un dieu magicien. Il avait enseigné aux druides son art sacré, d’où son abondante représentation en Gaule notamment. Sous le nom d’Hernè, il a pu s’imposer également chez les Germains voisins. Représenté avec des bois de cerf et non des cornes au sens strict, il était le dieu le plus important après Taranis et Lugus. En revanche, en Bretagne et en Irlande, il était absent. Son culte n’a pas pu traverser la Manche. Chez les Hittites, le dieu cornu Kahruhas était son strict équivalent mais notre connaissance à son sujet est des plus limités.

Les autres peuples indo-européens, tout en conservant la fonction de ce dieu, oublièrent en revanche son nom. Les Celtes ne le désignèrent plus que par le nom de Cernunnos, le dieu « cornu ». En tant que tel, il était le dieu de la richesse de la nature, le maître des animaux sauvages comme d’élevage, le dieu conducteur des morts et un dieu magicien. Il avait enseigné aux druides son art sacré, d’où son abondante représentation en Gaule notamment. Sous le nom d’Hernè, il a pu s’imposer également chez les Germains voisins. Représenté avec des bois de cerf et non des cornes au sens strict, il était le dieu le plus important après Taranis et Lugus. En revanche, en Bretagne et en Irlande, il était absent. Son culte n’a pas pu traverser la Manche. Chez les Hittites, le dieu cornu Kahruhas était son strict équivalent mais notre connaissance à son sujet est des plus limités.

Dans le panthéon slave, les deux divinités les plus fondamentales était Perun, maître de l’orage et dieu de la guerre, et Volos, dieu des troupeaux. Même si Volos est absent du panthéon officiel de Kiev établi par Vladimir en 980, son rôle demeura sous les traits de Saint Basile (Vlasios) lorsque la Rous passa au christianisme. Il était notamment le dieu honoré sur les marchés, un lieu central de la vie collective, d’où le fait que la Place Rouge de Moscou est jusqu’à nos jours dédiée à Basile. Volos n’était pas que le dieu des troupeaux. Il était le dieu des morts, ne se contentant pas de les conduire en Nav, le royaume des morts, même si la tradition slave évoque éventuellement un dieu infernal du nom de Viy. Il apportait la richesse et la prospérité en même temps que la fertilité aux femmes. Dieu magicien, il était le dieu spécifique des prêtres slaves, les Volkhvy, même si ces derniers avaient charge d’honorer tous les dieux. Perun et Volos s’opposaient souvent, le dieu du tonnerre n’hésitant pas à le foudroyer car Volos n’était pas nécessairement un dieu bon, et la tradition l’accusait d’avoir volé le troupeau de Perun. Une certaine confusion fit qu’on vit en lui un avatar du serpent maléfique retenant les eaux célestes, qui était Zmiya dans le monde slave, un dragon vaincu par la hache de Perun, tout comme Jormungandr fut terrassé par Thor dans la mythologie scandinave.

Dans le monde germanique, aucun dieu ne correspond vraiment au *Pauson indo-européen. La société germano-scandinave n’était pas une civilisation de l’élevage, et les fonctions commerciales relevaient du dieu Odin. Wotan-Odhinn, le grand dieu germanique, s’était en effet emparé de fonctions relevant de Tiu-Tyr (en tant que dieu du ciel et roi des dieux), de Donar-Thor (en tant que dieu de la guerre). Il existait certes un Hermod, dont le nom est à rapprocher de celui d’Hermès, mais qui avait comme seul et unique rôle celui de messager des dieux. Mais c’est sans doute Freyr, dont l’animal sacré était le sanglier, qui peut être considéré comme le moins éloigné de *Pauson. Frère jumeau de Freyja, la déesse de l’amour, il incarnait la fertilité sous toutes ses formes mais était aussi un dieu magicien. On ne le connaît néanmoins pas psychopompe, pas spécialement dédié non plus au commerce, ni à conduire des troupeaux. Wotan-Odhinn là encore était sans doute le conducteur des morts, soit en Helheimr, pour les hommes du commun, soit au Valhöll, pour les héros morts au combat. Le *Pauson proto-germanique a probablement disparu de bonne date, remplacé dans tous ses rôles par plusieurs divinités.

*Pauson était donc un dieu polyvalent. En tant que dieu des chemins, dieu « guide », ce que son nom semble signifier, il patronnait toutes les formes de déplacement, les routes mais aussi les frontières et les échanges. Il était en outre le dieu des animaux sauvages et des troupeaux, qu’il conduisait dans les verts pâturages. Il conduisait même les âmes morts aux Enfers et délivrait aux hommes les messages des dieux, même si ce rôle de dieu messager était partagé avec la déesse de l’arc-en-ciel *Wiris (lituanienne Vaivora, grecque Iris). C’était un dieu qui maîtrisait parfaitement les chemins de la pensée humaine. Les Grecs firent ainsi d’Hermès un dieu créateur et même celui de l’intelligence théorique aux côtés d’Athéna et d’Héphaïstos. Ils lui attribuèrent l’invention de l’écriture et même de la musique. Il est logique d’en avoir fait un magicien, capable de tous les tours et de tous les plans, y compris de s’introduire chez Typhon pour récupérer les chevilles divines de Zeus ou de libérer Arès, prisonnier d’un tonneau gardé par les deux géants Aloades. Sous les traits du romain Mercure, main dans la main avec Mars, il finit par incarner la puissance générée par le commerce, facteur de paix et de prospérité pour la cité autant que les légions à ses frontières.

Son importance était telle que les chrétiens annoncèrent sa mort, « le grand Pan est mort », pour signifier que le temps du paganisme était révolu. Pourtant il ne disparut pas, alors ils en firent leur Diable cornu et aux pieds de bouc. Il conserva ainsi son rôle de dieu des morts mais uniquement pour les pêcheurs, les vertueux accédant au paradis de Dieu.

Thomas FERRIER (PSUNE/LBTF)

00:05 Publié dans Traditions | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : mythologie, dieu cornu, cernunnos, indo-européens, traditions |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

mercredi, 08 avril 2015

Múdspelli

Also available in English.

In de Germaanse letterkunde van de vroege Middeleeuwen bestaat een zeer geheimzinnig woord dat telkenmale in één adem wordt genoemd met vuur en verwoesting en het einde van de wereld, te weten Múdspelli. Het is onduidelijk wat het letterlijk betekent en de vraag is bovendien of het oorspronkelijk een christelijk begrip is of dat het uit het oude Germaanse heidendom stamt. Er zijn al vele voorstellen gedaan, maar geen ervan is echt overtuigend. Valt er dan wellicht een nieuwe duiding te bedenken?

Saksen

Aan het begin van de negende eeuw is de kerstening van de Saksen –woonachtig in wat nu Noordwest-Duitsland en Noordoost-Nederland is– in volle gang. Als onderdeel van deze inspanningen verschijnt er tussen 825 en 850 een bijzonder werk: een Oudsaksisch heldendicht van wel zesduizend verzen, geheel in Germaans stafrijm, dat het verhaal van Jezus vertelt als ware hij een hoofdman die krijgers onder zich heeft en door de onmetelijke wouden van Middilgard reist. Het is niets minder dan de Germaanse uitgave van de blijde boodschap. De dichter is onbekend en hij heeft zijn werk geen naam gegeven, maar hij noemt Jezus onder meer de Hêliand (‘Heiland, Verlosser’) en onder die naam staat het thans bekend.

In verzen 2589b-2592a komen wij het geheimzinnige woord dan tegen (vertaling Van Vredendaal):

Tot wasdom komen ze samen;

de verdoemden groeien met de goeden op,

totdat Múdspelli’s macht over de mensen komt

bij het einde der tijden.

En een flink eind later, in verzen 4352a–64, andermaal (vertaling Van Vredendaal):

Wees waakzaam! Gewis komt voor jullie

de schitterende doemdag: dan verschijnt de heer

met zijn onmetelijke macht en het vermaarde uur,

de wending van de wereld. Wacht je er dus voor

dat hij je niet besluipt als je slaapt op je rustbed,

je bij verrassing overvalt bij je verraderlijke werken,

bij misdaad en zonde. Múdspelli komt

in duistere nacht. Zoals een dief zich beweegt

in het diepste geheim, zo zal de dag komen,

de laatste van dit licht, en de levenden overvallen,

gelijk de vloed deed in vroeger dagen:

de zwalpende zee verzwolg de mensen

in Noachs tijden.

Hoewel de Hêliand geen regelrechte Bijbelvertaling is komt het een en ander uiteraard zeer bekend voor: “Want gij weet zelven zeer wel, dat de dag des Heeren alzo zal komen, gelijk een dief in den nacht” (1 Thessalonicensen 5:2). Maar wie of wat Múdspelli nu genauw is blijft onduidelijk, al zal het voor de Saksische toehoorder een bekend begrip zijn geweest, wat erop duidt dat het oud is. De Hêliand is overigens het voornaamste van slechts enkele waarlijk letterkundige werken in het Oudsaksisch, dus het zal niet verbazen dat het verder niet voorkomt in Oudsaksische geschriften.

Beieren

Omstreeks 870 na Christus verschijnt verder naar het zuiden –in Beieren– een Oudhoogduits gedicht dat vertelt over de strijd tussen Elias en de Antichrist, als waren zij de keurstrijders van God en de grote Vijand. Elias verslaat de Antichrist, maar is zelf ook gewond en zodra zijn bloed de Aarde raakt ontbrandt zij op geweldige wijze. Regels 55b-60b (eigen vertaling):

De doemdag gaat dan te lande,

gaat met het vuur mannen bezoeken.

Daar kan een verwante een ander niet helpen tegenover het Múspilli.

Want de wijde aarde verbrandt geheel,

en vuur en lucht vagen alles weg;

waar is dan die beschikte grond waar een man immer met zijn verwanten voor vocht?

Het gedicht vertelt voorts dat heel Mittilgart zal branden: geen berg of boom wordt gespaard. Water droogt op, zeeën worden verzwolgen, de hemelen vlammen en de maan valt. Niets weerstaat het Múspilli. Men merke dan op dat de vorm van het woord iets anders is: in vergelijking met Oudsaksisch Múdspelli lijkt Oudhoogduits Múspilli wat meer verbasterd. Het blijft onduidelijk wat diens genauwe betekenis is, maar ook hier zal het voor de toehoorder van die tijd een bekend begrip zijn geweest.

IJsland

De laatste plekken waar het woord verschijnt –deze keer in de vorm Múspell– zijn in de Oudijslandse letterkunde. Een van de belangrijkste schriftelijke bronnen aangaande het Germaans-heidense wereldbeeld is een bundel van gedichten die thans bekend staat als de Poëtische Edda. De belangrijkste van deze is de Vǫluspá (‘voorspelling van de zienster’). Dit gedicht, dat waarschijnlijk in de 10e eeuw na Christus is opgesteld door een heiden die daarmee oeroude overlevering doorgaf, verhaalt van de schepping van de wereld en van het einde van de wereld – elders de Ragnarǫk genoemd. Wij lezen dan tegen het einde ervan, in verzen 44 en 45 (vertaling De Vries):

Een kiel uit het oosten

komt met de mannen

van Múspell beladen

en Loki aan’t roer.

Tezaam met de reuzen

rent nu de wolf,

en hen begeleidt

de broer van Byleist.

Uit het zuiden komt Surtr [‘Zwart’]

met vlammend zwaard

en gensters fonkelen

van dit godenwapen.

Rotsen barsten,

reuzen vallen,

de helweg gaan mannen,

de hemel splijt.

Elders in de Oudijslandse letterkunde krijgen wij meer te lezen over Múspell, en wel in de zogenaamde Proza-Edda, een soort dichtershandboek vol verhalen dat omstreeks 1220 door de christelijke geschiedkundige Snorri Sturluson is geschreven. Hij putte hiervoor uit de heidense overlevering, zoals de reeds genoemde gedichten hierboven, maar het is vaak niet te achterhalen in hoeverre hij er een eigen invulling aan gaf, waardoor voorzichtig lezen geboden is. In hoofdstuk 4 van het deel dat de Gylfaginning heet, meldt Snorri het volgende (eigen vertaling):

Toen sprak Derde: ‘Doch eerst was er in het zuiden de wereld die Múspell heet. Deze is licht en heet. Zó dat hij vlammend en brandend is. En hij is onbegaanbaar voor degenen die daar vreemdelingen zijn en daar niet hun vaderland hebben. Daar is een genaamd Surtr, die daar bij de grens ter verdediging zit. Hij heeft een vlammend zwaard, en bij het einde der wereld zal hij oorlog gaan voeren en alle goden verslaan en de hele wereld met vuur verbranden.’

Verderop in het verhaal wordt verteld dat Múspellsheimr (‘Múspells heem’) in de oertijd gesmolten deeltjes en vonken uitschoot en dat de goden en de dwergen hiervan de zon en de sterren hebben gemaakt. En er wordt meerdere malen verhaald van hoe Múspellsmegir (‘Múspells knapen’) en Múspellssynir (‘Múspells zonen’) op het laatst zullen uitrijden en oorlog zullen voeren, opdat Miðgarðr wordt verwoest.

Duiding

Dat het woord een samenstelling is staat vast, maar wat betekent het nu werkelijk en hoe oud is het? Is het een christelijk begrip dat zelfs IJsland wist te bereiken toen dat nog grotendeels heidens was –hetgeen op zichzelf niet ondenkbaar is– of is het oud genoeg om uit heidense tijden te stammen? Zoals gezegd is het waarschijnlijk tamelijk ouder dan zijn eerste verschijning op schrift, daar het woord al vrij bekend zal zijn geweest voor de toehoorders destijds, en lijkt het dus van heidense oorsprong.

Er is al in elk geval al aardig wat voorgesteld en het gesprek is nog steeds gaande. Een goede opsomming hiervan is te vinden in de onderaan vermelde verhandeling van Hans Jeske uit 2006. In het kort: voor het eerste lid is verband gezocht met o.a. Oudsaksisch múð ‘mond’ en Latijn mundus ‘wereld’, voor het tweede lid met o.a. Oudhoogduits spell ‘vertelling’ en spildan ‘vernietigen’, waardoor we uitkomen met duidingen als ‘mondelinge vernietiging’ (door God), ‘mondelinge vertelling’ (als onbeholpen vertaling van Latijn ōrāculum ‘goddelijke uitspraak’) of ‘wereldvernietiging’. Maar allen stuiten op vormelijke, inhoudelijke en/of geschiedkundige bezwaren, waardoor geen ervan echt weet te overtuigen. Het is dan ook de hoogste tijd voor een geheel nieuwe duiding.

Allereerst: het Oudgermaans erfde van zijn voorloper –het Proto-Indo-Europees– meerdere wijzen van samenstellingen maken. Bij één daarvan reeg men twee woorden én een achtervoegsel aan elkaar tot één onzijdig zelfstandig naamwoord. Het achtervoegsel gaf de samenstelling een lading van veelheid en verzameling. Een bekend voorbeeld hiervan is de samenstelling van *alja- ‘ander, vreemd’ + *landa- ‘land’ + *-jan (achtervoegsel) tot *aljalandjan (o.) ‘het geheel van andere landen’ oftewel ‘het buitenland’. Het woord is o.a. als Oudsaksisch elilendi, Oudhoogduits elilenti en Nederlands ellende overgeleverd. Deze wijze van samenstellen lijkt na de Oudgermaanse tijd niet meer in gebruik te zijn geweest, dus als wij zo’n samenstelling tegenkomen in de dochtertalen is zij waarschijnlijk vrij oud, namelijk van voor de kerstening der Germanen.

Welnu, Oudsaksisch Múdspelli, Oudhoogduits Múspilli en Oudnoords Múspell hebben er alles van weg genauw zo’n soort oude samenstelling te zijn. Onder meer omdat ze onzijdig zijn en een spoor van het genoemde achtervoegsel tonen. Dat wil zeggen, ze lijken terug te gaan op Oudgermaans *Mūdaspalljan (o.), een samenstelling van *mūda- + *spalla- + *-jan (achtervoegsel). De vraag is vervolgens: wat zijn *mūda- en *spalla-?

Over *spalla- kunnen we bondig zijn. Hoewel het anderszins niet is overgeleverd in de Germaanse talen is dit woord goed te verbinden met de Proto-Indo-Europese wortel *(s)pel-, *(s)pol-, die wij verder kennen van onder meer Oudkerkslavisch poljǫ, polĕti ‘branden, vlammen’ en Russisch pólomja ‘vlam’. Dan zou Oudgermaans *spalla- ook iets als ‘vuur’ of ‘vlam’ hebben betekend.

Over *mūda- valt meer te vertellen. Dit woord is, weliswaar verlengd met verschillende achtervoegsels, namelijk wél overgeleverd in de Germaanse talen. Enerzijds zijn er –met een achtervoegsel dat vertrouwdheid en verkleining aangeeft– Middelnederduits mudeke, 16e eeuws Nederlands muydick, streektalig Duits Muttich, Mutch, Mautch en Oostvlaams muik, die allen ongeveer ‘bewaarplaats of voorraad van ooft of geld’ betekenen, maar soms meer algemeen en oorspronkelijk ‘opeenhoping’. Anderszijds zijn er Oudhoogduits múttun (mv.) ‘voorraadschuren’, Silezisch Maute ‘bergplaats van ooft’ en Beiers Mauten ‘voorraad van ooft’.

Vervolgens kunnen wij dit *mūda- verbinden met de Proto-Indo-Europese wortel *meuH- ‘overvloedig, krachtig in vermenigvuldiging’ (voorgelegd door Michael Weiss in 1996), die anderszins ten grondslag ligt aan Grieks mūríos ‘talloos, onmetelijk’, Hettitisch mūri- ‘tros ooft’, Luwisch-Hettitisch mūwa- ‘een ontzagwekkende eigenschap, van bijvoorbeeld een koning of god’, Hiërogliefisch Luwisch mūwa- ‘overweldigen (o.i.d.)’ en ten slotte Latijn mūtō en Oudiers moth, beide ‘mannelijk geslachtsdeel’. Mogelijk horen hierbij ook Oudgermaans *mūhō ‘grote hoop’ (vanwaar o.a. Oudengels múha en Oudnoords múgi) en *meurjōn (vanwaar o.a. Nederlands mier).

Hieruit valt op te maken dat Oudgermaans *mūda- waarschijnlijk zoveel betekende als ‘opeenhoping, veelheid, overvloed e.d.’ of anders in bijvoeglijke zin ‘overvloedig’.

Besluit

*Mūdaspalljan is dan een zeer oud, heidens begrip dat het beste is op te vatten als het ‘Overvloedige Gevlamte’ of het ‘Vuur des Overvloeds’ en bij uitbreiding het ‘Vurige Wereldeinde’. En dat is een betekenis die uitstekend past in de zinsverbanden waarin we het woord in de dochtertalen tegenkomen. Men leze hen boven maar eens terug. Een mogelijk bezwaar is evenwel dat het woord dan uit tamelijk zeldzame woordstof is opgebouwd. Maar zoiets zouden we juist verwachten van een oud, mythologisch geladen woord. Germaanse dichters gebruikten vaak woorden die in de algemene taal niet of nauwelijks (meer) voorkwamen om zo een stijl van verheven ernst te scheppen.

Op grond van de Oudijslandse benamingen Múspellsmegir (‘Múspells knapen’) en Múspellssynir (‘Múspells zonen’) is wel betoogd dat Múspell een reus of iets dergelijks is. Maar het woord is zoals gezegd onzijdig en diens ‘knapen’ en ‘zonen’ zijn volgens de hier voorgesteld duiding goed te begrijpen als een dichterlijke voorstelling van de afzonderlijke vlammen die voortrazen als heel de wereld wordt verzwolgen.

De Vǫluspá verhaalt dat na deze eindstrijd de Aarde herrijst –groen en fris– en dat mensen een zorgeloos leven in vreugde zullen leiden. De overeenkomsten met de christelijke leer over het hiernamaals op een Nieuwe Aarde zijn opvallend en vaak wordt er aan ontlening gedacht. Doch als we beseffen dat er in de Oudgermaanse tijd menig langhuis en medehal in vlammen moet zijn opgegaan, wouden konden branden door ongelukkige blikseminslagen, en menig akker door vijanden ware verschroeid, en er niets anders opzat dan te herbouwen en herzaaien, dan is het goed mogelijk dat de heidenen van weleer dachten dat ooit heel Middilgard in het Múdspelli zou eindigen, dat de wereld der mannen zou branden in een Alverzengend Vuur, vooraleer het weer zou herrijzen – groen en fris.

Verwijzingen

Faulkes, A., Edda (Londen, 1995)

Jeske, H., “Zur Etymologie des Wortes muspilli”, in Zeitschrift für deutsches Altertum und deutsche Literatur, Bd. 135, H. 4 (2006), pp. 425-434

Krahe, H. & W. Meid, Germanische Sprachwissenschaft III: Wortbildungslehre (Berlijn, 1969)

Philippa, M., e.a., Etymologisch Woordenboek van het Nederlands (webuitgave)

Rix, H., Lexikon der indogermanischen Verben, 2. Auflage (Wiesbaden, 2001)

Simek, R., Lexikon der germanischen Mythologie, 3. Auflage (Stuttgart, 2006)

Vaan, M. de, Etymological Dictionary of Latin and the other Italic Languages (Leiden, 2008)

Vredendaal, J. van, Heliand (Amsterdam, 2006)

Vries, J. de, Nederlands etymologisch woordenboek (Leiden, 1971)

Vries, J. de, Edda: Goden- en heldenliederen uit de Germaanse oudheid, 10e druk (Deventer, 1999)

Weiss, M., “Greek μυϱίος ‘countless’, Hittite mūri- ‘bunch (of fruit)’”, in Historische Sprachforschung, 109. Bd., 2. H. (1996), pp. 199-214

00:05 Publié dans Littérature, Traditions | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : littérature, lettres, mythologie, mythologie chrétienne, tradition, traditionalisme, muspilli, mudspelli, haut moyen âge germanique, lettres allemandes, lettres germaniques, littérature allemande, littérature germanique, haut moyen âge, littérature médiévale, lettres médiévales |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

samedi, 28 février 2015

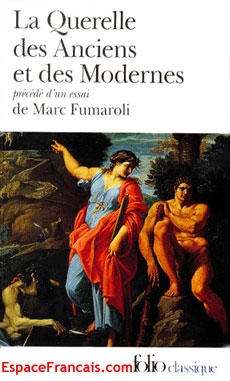

MYTHS AND MENDACITIES: THE ANCIENTS AND THE MODERNS

MYTHS AND MENDACITIES: THE ANCIENTS AND THE MODERNS

Tomislav Sunic

(The Occidental Quarterly, vol. 14, no. 4, Winter 2014–2015)

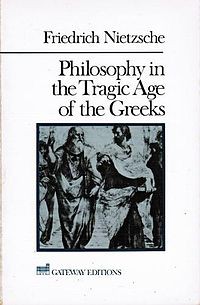

When discussing the myths of ancient Greece one must first define their meaning and locate their historical settings. The word “myth” has a specific meaning when one reads the ancient Greek tragedies or when one studies the theogony or cosmogony of the early Greeks. By contrast, the fashionable expression today such as “political mythology” is often laden with value judgments and derisory interpretations. Thus, a verbal construct such as “the myth of modernity” may be interpreted as an insult by proponents of modern liberalism. To a modern, self-proclaimed supporter of liberal democracy, enamored with his own system-supporting myths of permanent economic progress and the like, phrases, such as “the myth of economic progress” or “the myth of democracy,” may appear as egregious political insults.

When discussing the myths of ancient Greece one must first define their meaning and locate their historical settings. The word “myth” has a specific meaning when one reads the ancient Greek tragedies or when one studies the theogony or cosmogony of the early Greeks. By contrast, the fashionable expression today such as “political mythology” is often laden with value judgments and derisory interpretations. Thus, a verbal construct such as “the myth of modernity” may be interpreted as an insult by proponents of modern liberalism. To a modern, self-proclaimed supporter of liberal democracy, enamored with his own system-supporting myths of permanent economic progress and the like, phrases, such as “the myth of economic progress” or “the myth of democracy,” may appear as egregious political insults.

For many contemporaries, democracy is not just a doctrine that could be discussed; it is not a “fact” that experience could contradict; it is the truth of faith beyond any dispute. (1)

Criticizing, therefore, the myth of modern democracy may be often interpreted as a sign of pathological behavior. Given this modern liberal dispensation, how does one dare use such locutions as “the myth of modern democracy,” or “the myth of contemporary historiography,” or “the myth of progress” without being punished?

Ancient European myths, legends and folk tales are viewed by some scholars, including some Christian theologians, as gross re-enactments of European barbarism, superstition, and sexual promiscuity. (2) However, if a reader or a researcher immerses himself in the symbolism of the European myths, let alone attempts to decipher the allegorical meaning of the diverse creatures in those myths, such as, for instance, the scenes from the Orphic rituals, the hellhole of Tartarus, the carnage in the Iliad or in the Nibelungenlied, or the final divine battle in Ragnarök, then those mythical scenes take on a different, albeit often a self-serving meaning. (3) After all, in our modern so-called enlightened and freedom-loving liberal societies, citizens are also entangled in a profusion of bizarre infra-political myths, in a myriad of hagiographic tales, especially those dealing with World War II victimhoods, as well as countless trans-political legends which are often enforced under penalty of law. There-fore, understanding ancient and modern European myths and myth-makers, means, first and foremost, reading between the lines and strengthening one’s sense of the metaphor.

In hindsight when one studies the ancient Greek myths with their surreal settings and hyperreal creatures, few will accord them historical veracity or any empirical or scientific value. However, few will reject them as outright fabrications. Why is that? In fact, citizens in Europe and America, both young and old, still enjoy reading the ancient Greek myths because most of them are aware not only of their strong symbolic nature, but also of their didactic message. This is the main reason why those ancient European myths and sagas are still popular. Ancient European myths and legends thrive in timelessness; they are meant to go beyond any historical time frame; they defy any historicity. They are open to anybody’s “historical revisionism” or interpretation. This is why ancient European myths or sagas can never be dogmatic; they never re-quire the intervention of the thought police or a politically correct enforcer in order to make themselves readable or credible.

The prose of Homer or Hesiod is not just a part of the European cultural heritage, but could be interpreted also as a mirror of the pre-Christian European subconscious. In fact, one could describe ancient European myths as primal allegories where every stone, every creature, every god or demigod, let alone each monster, acts as a role model representing a symbol of good or evil. (4) Whether Hercules historically existed or not is beside the point. He still lives in our memory. When we were young and when we were reading Homer, who among us did not dream about making love to the goddess Aphrodite? Or at least make some furtive passes at Daphne? Apollo, a god with a sense of moderation and beauty was our hero, as was the pesky Titan Prometheus, al-ways trying to surpass himself with his boundless intellectual curiosity. Prometheus unbound is the prime symbol of White man’s irresistible drive toward the unknown and toward the truth irrespective of the name he carries in ancient sagas, modern novels, or political treatises. The English and the German poets of the early nineteenth century, the so -called Romanticists, frequently invoked the Greek gods and especially the Titan Prometheus. The expression “Romanticism” is probably not adequate for that literary time period in Europe because there was nothing romantic about that epoch or for that matter about the prose of authors such as Coleridge, Byron, or Schiller, who often referred to the ancient Greek deities:

The prose of Homer or Hesiod is not just a part of the European cultural heritage, but could be interpreted also as a mirror of the pre-Christian European subconscious. In fact, one could describe ancient European myths as primal allegories where every stone, every creature, every god or demigod, let alone each monster, acts as a role model representing a symbol of good or evil. (4) Whether Hercules historically existed or not is beside the point. He still lives in our memory. When we were young and when we were reading Homer, who among us did not dream about making love to the goddess Aphrodite? Or at least make some furtive passes at Daphne? Apollo, a god with a sense of moderation and beauty was our hero, as was the pesky Titan Prometheus, al-ways trying to surpass himself with his boundless intellectual curiosity. Prometheus unbound is the prime symbol of White man’s irresistible drive toward the unknown and toward the truth irrespective of the name he carries in ancient sagas, modern novels, or political treatises. The English and the German poets of the early nineteenth century, the so -called Romanticists, frequently invoked the Greek gods and especially the Titan Prometheus. The expression “Romanticism” is probably not adequate for that literary time period in Europe because there was nothing romantic about that epoch or for that matter about the prose of authors such as Coleridge, Byron, or Schiller, who often referred to the ancient Greek deities:

Whilst the smiling earth ye governed still,

And with rapture’s soft and guiding hand

Led the happy nations at your will,

Beauteous beings from the fable-land!

Whilst your blissful worship smiled around,

Ah! how different was it in that day!

When the people still thy temples crowned,

Venus Amathusia! (5)

Many English and German Romanticists were political realists and not daydreamers, as modern textbooks are trying to depict them. All of them had a fine foreboding of the coming dark ages. Most of them can be described as thinkers of the tragic, all the more as many of them end-ed their lives tragically. Many, who wanted to arrest the merciless flow of time, ended up using drugs. A poetic drug of choice among those “pagan” Romanticists in the early nineteenth-century Europe was opi-um and its derivative, the sleeping beauty laudanum. (6)

Myth and religion are not synonymous, although they are often used synonymously—depending again on the mood and political beliefs of the storyteller, the interpreter, or the word abuser. There is a difference between religion and myth—a difference, as stated above, depending more on the interpreter and less on the etymological differences between these two words. Some will persuasively argue that the miracles per-formed by Jesus Christ were a series of Levantine myths, a kind of Oriental hocus-pocus designed by an obscure Galilean drifter in order to fool the rootless, homeless, raceless, and multicultural masses in the dying days of Rome.(7)

Some of our Christian contemporaries will, of course, reject such statements. If such anti-Christian remarks were uttered loudly today in front of a large church congregation, or in front of devout Christians, it may lead to public rebuke.

In the modern liberal system, the expression “the religion of liberalism” can have a derisory effect, even if not intended. The word “religion” derives from the Latin word religare, which means to bind together or to tie together. In the same vein some modern writers and historians use the expression “the religion of the Holocaust” without necessarily assigning to the noun “religion” a pejorative or abusive meaning and without wishing to denigrate Jews. (8)

However, the expression “the religion of the Holocaust” definitely raises eyebrows among the scribes of the modern liberal system given that the memory of the Holocaust is not meant to enter the realm of religious or mythical transcendence, but instead remain in the realm of secular, rational belief. It must be viewed as an undisputed historical fact. The memory of the Holocaust, however, has ironically acquired quasi-transcendental features going well beyond a simple historical narrative. It has become a didactic message stretching well beyond a given historical time period or a given people or civilization, thus escaping any time frame and any scientific measurement. The notion of its “uniqueness” seems to be the trait of all monotheistic religions which are hardly in need of historical proof, let alone of forensic or material documentation in order to assert themselves as universally credible.

The ancestors of modern Europeans, the ancient polytheist Greeks, were never tempted to export their gods or myths to distant foreign peoples. By contrast, Judeo -Christianity and Islam have a universal message, just like their secular modalities, liberalism and communism. Failure to accept these Islamic or Christian beliefs or, for that matter, deriding the modern secular myths embedded today in the liberal system, may result in the persecution or banishment of modern heretics, often under the legal verbiage of protecting “human rights” or “protecting the memory of the dead,” or “fighting against intolerance.” (9).

There is, however, a difference between “myth” and “religion,” although these words are often used synonymously. Each religion is history-bound; it has a historical beginning and it contains the projection of its goals into a distant future. After all, we all measure the flow of time from the real or the alleged birth of Jesus Christ. We no longer measure the flow of time from the fall of Troy, ab urbem condita, as our Roman ancestors did. The same Christian frame of time measurement is true not just for the Catholic Vatican today, or the Christian-inspired, yet very secular European Union, but also for an overtly atheist state such as North Korea. So do Muslims count their time differently—since the Hegira (i.e., the flight of Muhammad from Mecca), and they still spiritually dwell in the fifth century, despite the fact that most states where Muslims form a majority use modern Western calendars. We can observe that all religions, including the secular ones, unlike myths, are located in a historical time frame, with well-marked beginnings and with clear projections of historical end-times.

On a secular level, for contemporary dedicated liberals, the true un-disputed “religion” (which they, of course, never call “religion”) started in 1776, with the day of the American Declaration of Independence, whereas the Bolsheviks began enforcing their “religion” in 1917. For all of them, all historical events prior to those fateful years are considered symbols of “the dark ages.”

What myth and religion do have in common, however, is that they both rest on powerful symbolism, on allegories, on proverbs, on rituals, on initiating labors, such as the ones the mythical Hercules endured, or the riddles Jason had to solve with his Argonauts in his search for the Golden Fleece. (10) In a similar manner, the modern ideology of liberalism, having become a quasi-secular religion, consists also of a whole set and subsets of myths where modern heroes and anti-heroes appear to be quite active. Undoubtedly, modern liberals sternly reject expressions such as “the liberal religion,” “the liberal myth,” or “the liberal cult.” By contrast, they readily resort to the expressions such as “the fascist myth” or “the communist myth,” or “the Islamo-fascist myth” whenever they wish to denigrate or criminalize their political opponents. The modern liberal system possesses also its own canons and its own sets of rituals and incantations that need to be observed by contemporary believers— particularly when it comes to the removal of political heretics.

Myths are generally held to be able to thrive in primitive societies only. Yet based on the above descriptions, this is not always the case. Ancient Greece had a fully developed language of mythology, yet on the spiritual and scientific level it was a rather advanced society. Ancient Greek mythology had little in common with the mythology of today’s Polynesia whose inhabitants also cherish their own myths, but whose level of philosophical or scientific inquiry is not on a par with that of the ancient Greeks.

Did Socrates or Plato or Aristotle believe in the existence of harpies, Cyclops, Giants, or Titans? Did they believe in their gods or were their gods only the personified projects of their rituals? Very likely they did believe in their gods, but not in the way we think they did. Some modern scholars of the ancient Greek mythology support this thesis: “The dominant modern view is the exact opposite. For modern ritualists and indeed for most students of Greek religion in the late nineteenth and throughout the twentieth century, rituals are social agendas that are in conception and origin prior to the gods, who are regarded as mere human constructs that have no reality outside the religious belief system that created them.” (11).

Did Socrates or Plato or Aristotle believe in the existence of harpies, Cyclops, Giants, or Titans? Did they believe in their gods or were their gods only the personified projects of their rituals? Very likely they did believe in their gods, but not in the way we think they did. Some modern scholars of the ancient Greek mythology support this thesis: “The dominant modern view is the exact opposite. For modern ritualists and indeed for most students of Greek religion in the late nineteenth and throughout the twentieth century, rituals are social agendas that are in conception and origin prior to the gods, who are regarded as mere human constructs that have no reality outside the religious belief system that created them.” (11).

One can argue that the symbolism in the myths of ancient Greece had an entirely different significance for the ancient Greeks than it does for our contemporaries. The main reason lies in the desperate effort of the moderns to rationally explain away the mythical world of their ancestors by using rationalist concepts and symbols. Such an ultrarational drive for the comprehension of the distant and the unknown is largely due to the unilinear, monotheist mindset inherited from Judaism and from its offshoot Christianity and later on from the Enlightenment. In the same vein, the widespread modern political belief in progress, as Georges Sorel wrote a century ago, can also be observed as a secularization of the biblical paradise myth. “The theory of progress was adopted as a dogma at the time when the bourgeoisie was the conquering class; thus one must see it as a bourgeois doctrine.” (12)

The Western liberal system sincerely believes in the myth of perpetual progress. Or to put it somewhat crudely, its disciples argue that the purchasing power of citizens must grow indefinitely. Such a linear and optimistic mindset, directly inherited from the Enlightenment, prevents modern citizens in the European Union and America from gaining a full insight into the mental world of their ancestors, thereby depriving them of the ability to conceive of other social and political realities. Undoubtedly, White Americans and Europeans have been considerably affected by the monotheistic mindset of Judaism and its less dogmatic offshoot, Christianity, to the extent that they have now considerable difficulties in conceptualizing other truths and other levels of knowledge.

It needs to be stressed, though, that ancient European myths have a strong component of the tragic bordering on outright nihilism. Due to the onslaught of the modern myth of progress, the quasi-inborn sense of the tragic, which was until recently a unique character trait of the White European heritage, has fallen into oblivion. In the modern liberal system the notion of the tragic is often viewed as a social aberration among individuals professing skepticism or voicing pessimism about the future of the modern liberal system. Nothing remains static in the notion of the tragic. The sheer exuberance of a hero can lead a moment later to his catastrophe. The tragic trait is most visible in the legendary Sophocles’ tragedy Oedipus at Colonus when Oedipus realizes that he is doomed forever for having unknowingly killed his father and for having un-knowingly had an incestuous relationship with his mother. Yet he struggles in vain to the very end in order to escape his destiny. Here is the often quoted line Nr. 1225, i.e., the refrain of the Chorus:

Not to be born is past all prizing best; but when a man has seen the light this is next best by far, that with all speed he should go thither whence he has come. (13)

The tragic consists in the fact that insofar as one strives to avoid a catastrophe, one actually brings a catastrophe upon himself. Such a tragic state of mind is largely rejected by the proponents of the liberal myth of progress.

MYTHS AND THE TRAGIC: THE COMING OF THE TITANIC AGE

Without myths there is no tragic, just like without the Titans there can be no Gods. It was the twelve Titans who gave birth to the Gods and not the other way around. It was the titanesque Kronos who gave birth to Zeus, and then, after being dethroned by his son Zeus, forced to dwell with his fellow Titans in the underworld. But one cannot rule out that the resurrection of the head Titan Kronos, along with the other Titans, may reoccur again, perhaps tomorrow, or perhaps in an upcoming eon, thus enabling the recommencement of the new titanic age. After all Prometheus was himself a Titan, although, as a dissident Titan, he had decided to be on the side of the Gods and combat his own fellow Titans. Here is how Friedrich Georg Jünger, an avid student of the ancient Greek myths and the younger brother of the famous contemporary essayist Ernst Jünger, sees it:

Neither are the Titans unrestrained power-hungry beings, nor do they scorn the law; rather, they are the rulers over a legal system whose necessity must never be put into doubt. In an awe -inspiring fashion, it is the flux of primordial elements over which they rule, holding bridle and reins in their hands, as seen in Helios. They are the guardians, custodians, supervisors, and the guides of order. They are the founders unfolding beyond chaos, as pointed out by Homer in his remarks about Atlas who shoulders the long columns holding the heavens and the Earth. Their rule rules out any confusion, any disorderly power performance. Rather, they constitute a powerful deterrent against chaos. (14)

Nothing remains new for the locked-up Titans: they know every-thing. They are the central feature in the cosmic eternal return. The Titans are not the creators of chaos, although they reside closer to chaos and are, therefore, better than the Gods—more aware of possible chaotic times. They can be called telluric deities, and it remains to be seen whether in the near future they may side up with some chthonic monsters, such as those described by the novelist H. P. Lovecraft.

It seems that the Titans are the necessary element in the cosmic balance, although they have not received due acknowledgment by contemporary students of ancient and modern mythologies. The Titans are the central feature in the study of the will to power and each White man who demonstrates this will has a good ingredient of the Titanic spirit:

What is Titanic about man? The Titanic trait occurs everywhere and it can be described in many ways. Titanic is a man who completely relies only upon himself and has boundless confidence in his own powers. This confidence absolves him, but at the same time it isolates him in a Promethean mode. It gives him a feeling of independence, albeit not devoid of arrogance, violence, and defiance. (15)

Today, in our disenchanted world, from which all gods have departed, the resurgence of the Titans may be an option for a dying Western civilization. The Titans and the titanic humans are known to be out-spoken about their supreme independence, their aversion to cutting deals, and their uncompromising, impenitent attitude. What they need in addition is a good portion of luck, or fortuna.

Notes:

1. Louis Rougier, La mystique démocratique (Paris: Albatros, 1983), p. 13.

2. Nicole Belmont, Paroles païennes: mythe et folklore (Paris: Imago, 1986) quotes on page 106 the German-born English Orientalist and philologist Max Müller who sees in ancient myths “a disease of language,” an approach criticized by the anthropological school of thought. His critic Andrew Lang writes: “The general problem is this: Has language—especially language in a state of ‘disease,’ been the great source of the mythology of the world? Or does mythology, on the whole, represent the survival of an old stage of thought—not caused by language—from which civilised men have slowly emancipated themselves? Mr. Max Müller is of the former, anthropologists are of the latter, opinion.” Cf. Andrew Lang, Modern Mythology (New York: Longmans, Green, and Co., 1897), p.x.

3. Thomas Bullfinch, The Golden Age of Myth and Legend (London: Wordsworth Editions, 1993).

4.See the German classicist, Walter F. Otto, The Homeric Gods: The Spiritual Significance of Greek Religion, trans. Moses Hadas (North Stratford, NH: Ayer Company Publishers, 2001). Otto is quite critical of Christian epistemology. Some excerpts from this work appeared in French translation also in his article, “Les Grecs et leurs dieux,” in the quarterly Krisis (Paris), no. 23 (January 2000).

5. Friedrich Schiller, The Gods of Greece, trans. E. A. Bowring. ttp://www.bartleby.com/270/9/2.html

6. Tomislav Sunic, “The Right Stuff,” Chronicles (October 1996), 21–22; Tomislav Sunic, “The Party Is Over,” The Occidental Observer (November 5, 2009). http://www.theoccidentalobserver.net/authors/Sunic-Drugs.html

7.Tomislav Sunic, “Marx, Moses, and the Pagans in the Secular City,” CLIO: A Journal of Literature, History, and the Philosophy of History 24, no. 2 (Winter 1995).

8.Gilad Atzmon, The Wandering Who? A Study of Jewish Identity Politics (Winchester, UK: Zero Books, 2011), 148–49.

9. Alain de Benoist, “Die Methoden der Neuen Inquisition,” in Schöne vernetzte Welt (Tübingen: Hohenrain Verlag, 2001), p. 190–205.

10. Michael Grant, Myths of the Greeks and Romans (London: Phoenix, 1989), p. 289–303.

11. Albert Henrichs, “What Is a Greek God?,” in The Gods of Ancient Greece, ed. Jan Bremmer and Andrew Erskine (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2010), p- 26.

12. Georges Sorel, Les Illusions du progrès (Paris: Marcel Rivière, 1911), p. 5–6.