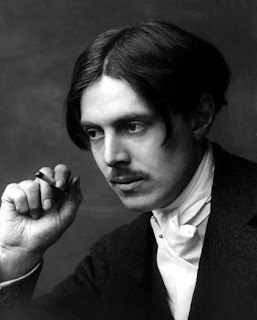

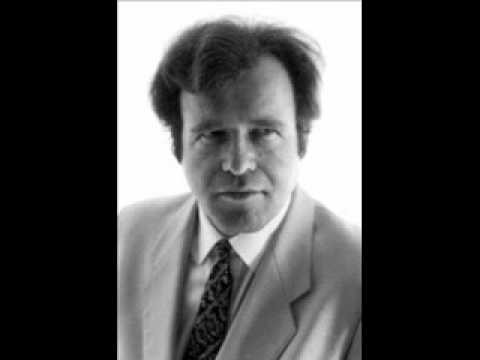

William Joyce, more infamously known to history as “Lord Haw Haw,” the epitome of a British Traitor, was hanged on the basis of a passport technicality on January 3, 1946. Like the name “Quisling” (see Ralph Hewin’s excellent biography Quisling: Prophet Without Honour) much nonsense persists about Joyce.

William Joyce, more infamously known to history as “Lord Haw Haw,” the epitome of a British Traitor, was hanged on the basis of a passport technicality on January 3, 1946. Like the name “Quisling” (see Ralph Hewin’s excellent biography Quisling: Prophet Without Honour) much nonsense persists about Joyce.

The following is redacted from my introduction to William Joyce’s Twilight Over England [2] (London: Black House Publishing, 2013). The second part of the introduction, not included here, examines the primary points of Joyce’s book, the continuing relevance of which is its cogent criticism of Free Trade liberalism and international finance.

***

Twenty-five years ago I was told a little anecdote by a work colleague, a middle aged Englishman. He said that as a small lad in England he and his friends were one Christmas eve singing carols to earn some pocket money. One household they came to was particularly memorable for him during those Depression years. A gentleman answered the door, invited the children inside and gave them each not only a cake but also a shilling. What struck my work colleague all those years later, still, was not only the generosity of the amount each child had been given, but more particularly, that someone from the ‘middle class’, invited a group of working class children in to the household where they received their cakes and coins. Such lack of social snobbery was a rarity that my work colleague had never forgotten. My English friend concluded by stating that the kind benefactor was named William Joyce.

My English friend was no Nazi; not even vaguely ‘right-wing’. His anecdote on this humanity of William Joyce, enduringly hated as a traitor, whose very name, as ‘Lord Haw-Haw’, as he was dubbed by the Allied propaganda machine, is Britain’s equivalent to Norway’s Quisling, and America’s Benedict Arnold. Joyce, as a British ‘Nazi’, is automatically regarded as a rogue, a lunatic, an apologist for mass murder and aggression, a fool, or any combination thereof. Yet the anecdote from my English friend’s childhood betrays a human side to the likes of William Joyce that just maybe indicates the he was none of those things, but a man of entirely different character. For in Twilight Over England, written while Joyce’s beloved Britain – yes, beloved Britain – was at war with Germany, and while Joyce had made the fateful decision that siding with those who were fighting Britain was the greatest manifestation of that love of Britain, we have the testament of a man deeply anguished at the level to which his people had been reduced by a rapacious system. That this system of international finance and Free Trade is more fully enthroned today and over more of the world than in Joyce’s time shows the relevance of this volume for the present and foreseeable future. In Twilight Over England we might discern – if we open our minds, and for a little while at least, leave behind the prejudgements and the victor’s hateful propaganda – the historical circumstances, centuries in the making, that brought this Briton to a martyr’s death.

Indeed, J A Cole, as objective a biographer that one could expect, described Joyce as ‘intelligent, well-educated, dedicated, hardworking, fluent and sharp-tongued’.[1] Although critical of Joyce, Cole also described him as ‘so unlike the stereotype which fear and prejudice had created’.[2] As a paid broadcaster for the Germans during the war, Joyce retained a character devoid of egotism and vanity, living frugally, refusing pay raises and perks other than cigarettes, and only being persuaded with some difficulty to buy himself a smartly-cut suit.[3] How far away the reality of Joyce was from the character depicted, apparently without a shred of good conscience, by Rebecca West, who gloated at Joyce’s trial, referring to him as opening ‘a vista into a mean life’, always speaking ‘as though he was better fed and better clothed than we were, and so, we now know, he was’,[4] going so far as to describe Joyce as ‘a tiny little creature’,[5] presumably confident that such was the hysteria that nothing she wrote against him would be challenged. It is as though West, and a gaggle of lesser slanderers, took all that Joyce truly was and turned it on its head. However, anyone with an eye to fame or money can still write whatever junk they can contrive on certain events related to the Second World War, and seldom are they called to account for their humbug. Indeed, to expose the lies can render one a jail sentence in many states and the destruction of one’s reputation and career.[6]

Joyce was a rare combination in history: an activist, a revolutionary, and a tough fighter, scarred with a Communist-welded razorblade. He was not some sallow intellectual whose only battle was fought within the brain and with verbosity at a safe distance from one’s targets. He had been the Director of Propaganda for a mass movement, Sir Oswald Mosley’s British Union of Fascists, which like Fascist movements across the world in the aftermath of the First World War, attracted individuals of many types and classes in solidarity. In Britain these included the American expatriate poet Ezra Pound, a founder of modern English literature;[7] Wyndham Lewis, novelist, painter, philosopher and co-founder with Pound of the Vorticist arts movement; the British nature writer and Hawthorne Prize Winner Henry Williamson, who never repudiated his belief in the heroic virtues of Mosley or Hitler, even after the war and who, like many who joined Mosley, was a First World War veteran haunted by the prospect of another war, but also reminded of the Europe that might still be when on Christmas Eve 1914 Germans and Britons greeted each other in no-man’s land to play football, returning to slaughter one another the following day; the military strategist, General J F C Fuller, father of modern tank warfare; and many others of the highest intellectual and cultural calibre.

William was born in New York on 24 April 1906, his father, Michael Francis Joyce, a Catholic, having migrated from Ireland in 1892, and marrying Gertrude Brooke, daughter of a Lancashire physician. In 1906 the family returned to Ireland, Michael having done well as a builder, and now becoming a publican and a property owner. William was educated at Catholic schools, and at an early age threw himself with gusto into whatever he did: When assisting at a service in the chapel he swung the censer with such force that the glowing incense flew down the aisle. He received his broken nose not through a fist fight with a Communist during the 1920s or 30s, but with a boy at school who had called him an ‘Orangeman’, because of the Joyce family’s avidly pro-British sentiments at the time of Ireland’s tribulations. His nose was not properly attended to, and hence William always had a distinctively nasal tone to his voice. During the Republican rebellion Michael’s properties endured arson. Young William saw the body of his neighbour, a policeman, on the road, with a bullet through his head. On another occasion he witnessed a Sinn Feiner cornered and shot by police.[8]

In 1920 the British Government reinforced the Royal Irish Constabulary with the Black & Tan paramilitaries. At fourteen, William served as a spy for the authorities, keeping his eyes and ears open for snippets of information that might be of use, and ran a squad of sub-agents. With the truce of 1921, and the departure of the British, the Joyce family moved to England. At 15, eager to continue serving King and Empire, he enlisted in the army at Worcester, giving his age as 18, but his real age was soon discovered and he was discharged. At 16 he joined the Officer Training Corps at the University of London, and after graduating from Battersea Polytechnic, enrolled at Birbeck College, part of the University.

Of Joyce’s intellectual gifts, his lifelong friend and comrade, John MacNab related to Cole:

‘He kept no files, diaries or notes of any kind, but he could recall the date, place and circumstances of remote events and meetings with people. He never forgot a face or a name, and could give a full account, unhesitatingly, of almost anything that had ever happened to him. At intervals of years he would repeat the same account without the least variation. He could quote – always exactly – any poem he had ever read with attention, and even notable pieces of prose. As a Latin scholar his technical qualifications were inferior to my own, yet he was the one who could quote Virgil or Horace etc., freely and always to the point, not I’.[9]

MacNab stated that Joyce was a multi-linguist, gifted in mathematics and his ability to teach it. ‘He read widely in history, philosophy, theology, psychology, theoretical physics and chemistry, economics law, medicine, anatomy and physiology. When he broke his collarbone in 1936 while skating, he was able to set it himself due to his knowledge of physiology. He was a talented pianist’.[10]

British Fascisti

While pursuing a BA in Latin, French, English and History, in 1923 he joined the British Fascisti, founded that year by Miss R L Linton-Orman, a member of a distinguished military family who had served with the Women’s Reserve Ambulance during the Frost World War and had twice been awarded the Croix de Charité for gallantry for heroic rescues in Salonica.[11]

The first such body to be established in Britain, inspired by the assumption to power by Mussolini in 1922, and the destruction of Communism in Italy, there was not much ideological substance to the British Fascisti (later ‘British Fascists’), other than loyalty to ‘King and Empire’, a determination to form a paramilitary force to stop Communism in the event of revolution or strikes, and to maintain order at Conservative Party meetings when Communists and Labourites threatened violence. The membership was drawn mainly from the middle and upper classes, and included a good number of retired officers. The first president of the British Fascists was Lord Garvagh, who was succeeded by Brigadier-General Blakeney, later associated with both Arnold Leese’s Imperial Fascist League, a small but persistent anti-Semitic group; and Mosley’s British Union.[12] The present of such personalities indicates the impression that Fascist Italy was making on important sections of Britain, and that it could never be dismissed as the collective delusions of a ‘lunatic fringe’.

Despite the lack of ideological substance, many stalwart Fascists got their start with the British Fascisti, including those who were to play a prominent role in the British Union of Fascists (BUF). It was as leader of the ‘I Squad’ of the British Fascisti that on 22 October 1924 Joyce stationed his men at Lambeth Baths Hall in South-East London, to protect the election meeting of Jack Lazarus, Conservative party Parliamentary candidate for Lambeth North, from Communist attack. These were times in which electoral meetings not approved by the Left were subjected to attack from Communist and Labour party thugs armed with razors, often put into potatoes for throwing, and spiked sticks. Hence, the British Fascisti emerged at a time of a very real threat of violence by the Left against the Conservative and Unionist parties, regardless of the other shortcomings of the organisation as a serious political alternative.

The Communist assault on Lazarus’ election meeting was ‘vicious’.[13] A ‘Jewish Communist’, as Joyce described him, jumped on his back and tried to slash his throat with a razor, but only succeeded in cutting Joyce from mouth to ear, his neck protected by a thick woollen scarf. He did not realise he had been slashed until the crowd drew back aghast, and he attempted to stem the blood with a handkerchief given to him, then walked to the police station where he collapsed.

While active with the British Fascisti, Joyce was also president of the Conservative Society at Birbeck College, where he developed his oratory, seeing Conservatism as the upholder of ‘Anglo-Saxon tradition and supremacy’.[14] Meanwhile, 1926 proceeded with a General Strike that did not result in the threat of a Soviet Britain, and the British Fascisti went into decline. That year Joyce married Hazel Barr, while continuing to do well with his studies, and the following year obtained First Class Honours in English, but did not complete his MA. His attempts for several years to introduce the Conservative Party to ‘true Nationalism’ failed. Biding his time, as the several small Fascist groups that arose failed to impress him, Joyce taught at the Victoria Tutorial College, and then at King’s College.

The Red thuggery that the British Fascists had attempted to combat continued. A target was to be not a party from the Right but from the Left: the New Party, founded in 1931 by the Labour Party’s most promising young politician, Sir Oswald Mosley, after Labour Caucus refused to adopt Mosley’s bold plan for unemployment.[15] The New Party was regarded as traitorous by the Labour Party, and was subjected to violent attacks by Communists and Labourites. It was such violence that contributed to Mosley’s turning to Fascism and forming his Blackshirt squads to protect the meetings that he could not efficiently protect during the New Party electoral campaigns, although even then he had started forming a squad of stewards trained in boxing by Jewish boxing champion Ted ‘Kid’ Lewis. Mosley records that extreme Left reaction had been subdued until the promising results of the New Party vote came out in a by-election.[16] Mosley, referring to the General Election soon after, related: ‘All over the country we met a storm of organised violence. They were simply out to smother us, we were to be mobbed down by denying us our only resource: the spoken word; we were to be mobbed out of existence’.[17]

In 1932 Mosley visited Fascist Italy, and like many others was impressed by what he saw at a time when Britain continued to stagnate. Joyce read the news reports of Mosley’s visit with interest but, having long had an increasing animosity against Jewish influence in Britain, was more interested in the progress that the Hitler movement was making in Germany.[18] When Mosley re-established the New Party as the British Union of Fascists most of the adherents of other Fascist groups, particularly the British Fascists, joined him. Joyce joined the BUF in 1933,[19] and, fatefully, obtained a British passport by falsely claiming that he had been born a British subject, with the expectation that he might accompany Mosley on a visit to Hitler.

Joyce was soon noted in the BUF for his oratory skills, and he resigned his teaching post at Victoria Tutorial College and his studies at London University to become the BUF’s West London Area Administration Officer. He then became Propaganda Director, addressing hundreds of meetings. It was on hearing Joyce, then 28, speaking that ex-Labour MP John Beckett,[20] joined the BUF, and committed himself to National Socialism, having previously been impressed by what he had seen in Fascist Italy, declaring Joyce to be one of the greatest orators who had recruited thousands to Fascism.[21] Indeed, Joyce filled in for Mosley if the latter could not attend a function. Jeffrey Hamm, a young Mosleyite before the war, who became particularly active in Mosley’s post-war Union Movement, reminisced on Joyce’s oratory that ‘his wit and repartee were proverbial’. ‘On one occasion a buxom lady in the crowd was shouting abuse at him, culminating in an angry roar: “You bastard!” Quick as a flash Joyce gave her a cheerful wave, as he cried: “Hullo, Mother!”’[22]

Joyce divorced Hazel amicably in 1934. He had sired two daughters who were close to their father, despite his hectic life as a Fascist leader.

His BUF classes on Fascist ideology, held jointly with his closest colleague, John Angus Macnab, with whom he also established a private tutoring business, were used to propagate his own views on Fascism, and here he introduced the term National Socialism to the movement, which was renamed the British Union of Fascists and National Socialists in 1936.[23] Although Joyce believed that National Socialism was intrinsically based on the nation from which it arose, was more inclined to quote Thomas Carlyle than Hitler, and eschewed both the swastika and the fasces when creating his own movement, he saw Hitler as a closer example to consider than Mussolini, not least because Hitler dealt with the Jewish question head-on. It was Joyce who coined the BUF axiom: ‘If you love your country you are National. If you love your people, you are Socialist. Be a National Socialist’. The reader will find this phrase cogently explained in Twilight Over England.

Joyce met Christian Bauer, who represented Goebbels’ newspaper Der Angriff, in Britain, and at Bauer’s request, after his return to Germany, Joyce maintained contact with him,[24] although it transpired that Bauer was more important when in Britain than he was in Germany.

In 1937 Joyce married Margaret White, a Manchester BUF organiser, who had accepted his proposal at a party, even although the two hardly knew one another. It had been literally ‘love at first sight’ between the two, and a scholarly member of her branch remarked on the engagement that it ‘may be uncomfortable being married to a genius. And William is a genius, you know!’[25] On the first day of the year, the Public Order Act was introduced banning the wearing of uniforms at public political functions; i.e. the black shirt, prohibiting the effective stewarding of open-air meetings, and other measures designed to impinge on the BUF campaign. As previously stated, Mosley had adopted a black shirt uniform to establish a disciplined and recognisable formation to keep order at his meetings having experienced Red thuggery at New Party meetings, as had the Conservative Party many years. The banning of the uniform saw a considerable rise in disorder at BUF functions. Despite the great deal of nonsense that had been alleged about ‘Fascist violence,’ the Blackshirts always answered the razorblade and the cosh with fists when necessary. One of these great myths is that Lord Rothermere, proprietor of the Daily Mail, who had supported the BUF during the first few years, withdrew his support in 1934 because of such Fascist violence. In fact, as related by Randolf Churchill some thirty years later, it was due to ‘the pressure of Jewish advertisers’.[26]

By 1937, both Joyce and Beckett, editor of Action and The Blackshirt, had become increasingly critical of BUF administration. Matters were decided when Mosley was obliged through financial stringency to reduce the paid-staff by four-fifths. Among them were both Joyce and Beckett. Macnab, the editor of Fascist Quarterly, resigned in protest at Joyce’s dismissal. Macnab & Joyce, Private Tutors, was a now established to earn a modest income to offer tuition for university entrance and professional preliminary examinations, and to teach English to foreign pupils of sound character.

National Socialist League

Joyce’s concerns were directed towards forming a new political organisation that would more precisely reflect his view on British National Socialism. Joyce, Beckett, McNabb and a few others founded the National Socialist League. Despite Joyce’s admiration for Hitler, his organisation was based on British roots. That a front-group for the League was named the Carlyle Club after Thomas Carlyle, whom Joyce often cited as a precursor of British National Socialism, is indicative of the British character of his variation of National Socialism. After all the concept of the National and the Social synthesis is universal, and movements of such a type had been arising spontaneously and independently of one another since the immediate aftermath of the First World War. One might refer to the Legion of the Archangel Michael in Romania, the Hungarist movement in Hungary, National-Syndicalist Falangism in Spain, and many others throughout the world. The Israeli scholar Dr Zeev Sternhell provides a convincing argument for the emergence of proto-Fascism from a union of Left-wing syndicalist and Right-wing Monarchist theorists in France as early as the late 19th century.[27] Mosley’s ‘Fascism’ had been based on his Birmingham manifesto to cure unemployment through a massive public works programme that had been rejected as too radical by the Labour Government, not by reading Mein Kampf or Mussolini’s Doctrine of Fascism.

As for Joyce’s National Socialist League, it was surprisingly ‘democratic’ in structure, with leaders elected at branch level, and no fuehrer-complex being evident in either Beckett of Joyce. Nor was there a paramilitary complexion to the group.[28] The symbol was a ship’s steering wheel, the design of which is also suggestive of a Union Jack, below which was the motto: ‘Steer Straight’. A newspaper was published, The Helmsman. Funding came from Alec Scrimgeour, an elderly stockbroker, whom Joyce had known since the BUF, and who treated Joyce as a son. Cole mentions that one supporters ‘claimed to be the King of Poland’. This cannot be anyone other than the New Zealand poet Geoffrey Potocki de Montalk who, unlike his many contemporaries who were embracing to Communism, being a Monarchist, embraced the Right, then Fascism and National Socialism, and never recanted. Indeed, even in December 1945, Potocki printed an ‘Xmas card’, the ‘X’ in the shape of a swastika, with a poem that paid tribute to ‘our William Joyce’. As to his eccentric claim to the throne of Poland, it was as legitimate as any other, being descended from a Polish noble lineage. [29]

The primary ideological text of the League was National Socialism Now, published in September 1937. National Socialism Now is a cogent 57 pages defining the fundamentals of National Socialist ethos, method of statecraft, and type financial and economic systems. Joyce’s opening lines are that,

‘We deal with National Socialism for Britain; for we are British. Our League is entirely British; and to win the victory for National Socialism here, we must work hard enough to be excused the inspiring task of describing National Socialism elsewhere’.[30]

While National Socialism was forever linked with the name of Hitler, no matter where it arises it ‘must arise from the soil and people or not at all’.

‘It springs from no temporary grievance, but from the revolutionary yearning of the people to cast off the chains of gross, sordid, democratic materialism without having to put on the shackles of Marxian Materialism, which would be identical with the chains cast off’.[31]

Joyce returned to a theme that he had introduced to the BUF, that the synthesis of Nationalism and Socialism is a logical development; that ‘the people’ are identical with ‘the nation’, and anything else, whether called ‘nationalism’ or ‘socialism’, is a waste of time. It was Socialism that provided the foundation for class unity rather than class antagonism, which had been engendered by the dislocations caused by industrialism and usury. Such class division is aggravated rather than transcended by Marxism and other forms of materialistic socialism. Both Capitalism and Marxism are international. Indeed Marx pointed this out in The Communist Manifesto, and described anyone resisting this internationalising tendency of Capitalism as ‘reactionary’, because the historical process towards Communism is aided by Capitalist internationalisation, and what Marx called the ‘uniformity in the mode of production’ across the world.[32] Today we call this ‘globalisation’ and the process has been accelerating. What has emerged is not Communism, but a Capitalist ‘new world order’. Communism is not even anti-Capitalist, but an extension of it, and hence, as Joyce explains in Twilight, it is Nationalism, intrinsically based on Socialism, that not only opposes Capitalism, but transcends it. Equally, any Socialism that embraces internationalism is not only hopeless in combating Capitalism, but assists in its victory. We are now able with both hindsight and observing present-day events, to confirm that this indeed the case. Communism, and Social Democracy literally failed to ‘delver the goods’, and now Free Trade Capitalism runs rampant over the entire world, imposed by US weaponry where, where debt to international finance and the opiate of the shopping mall and MTV are insufficient. The Socialism of Joyce’s day, represented mainly by the Labour Party, did not oppose the system of international finance any more than the Conservative Party, that had long since forsaken its patriotic and rural origins, and both permitted a system of Liberal Free Trade that invested capital to build up cotton manufacturing in India for example, while allowing the mill workers of Lancashire to rot.[33] The same situation is visited upon us in recent years, with Tony Blair’s ‘New Labour’ in Britain, and in New Zealand, the Labour Party during the 1980s, being in the forefront of inaugurating ‘Free Trade’ in the name of ‘socialism’. Joyce saw it going on in his own day. We relive it today. The same old abandonment to Capitalism by Social Democracy, which had also obliged Mosley to resign from the Labour Party in disgust.

The weakness of Westminster parliamentary democracy allowed international finance to carry on unhindered. Joyce’s British National Socialism advocated the ‘leadership principle’, with authority to act, but in Britain’s case the symbol of unity within one personality had existed for centauries in the form of the Crown, and Joyce did not envisage a National Socialist Britain that need be under the dictatorship of a British ‘fuehrer’. Indeed, he advocated the corporatist or organic state that he had alluded to in his BUF pamphlet, Dictatorship. In NS Now Joyce pointed to the guilds of Medieval Britain, and outlined a corporate state based on the revival of the guilds as taking over many functions of the state. Both employers and employees would be represented in the same corporative organs, which was the method of successful industrial organisation that would be enacted in Germany in the Reich Economic Chamber. Parliament would hence be a corporative body with representatives elected from such guilds.

Joyce next turned his attention to the financial system. National Socialist banking reform is based the premise that money and credit should serve the people, and not master them. Hence, credit and currency should be issued by the state according to the production of the people, allowing the people to consume that production. Private financial interests should not issue credit and currency as a profit -making commodity. Currency and credit are only intended as a means of exchanging goods and services. That is the method that National Socialist Germany, Fascist Italy and Imperial Japan used and by which they flourished in the midst of the world Depression.[34] Again, there is nothing intrinsically ‘fascist’ or ‘nazi’ in such a banking system. The First New Zealand Labour Government had initiated the same type of policy, issuing 1% Reserve Bank state credit in 1935 for the construction of New Zealand’s iconic state housing project, which itself solved 75% of the unemployment rate.[35] Banking reformers around the world were demanding that the state assume its prerogative to issue the nation’s own credit and currency, without recourse to becoming indebted in perpetuity to international finance.[36] As Joyce was to emphasis in Twilight, it was this struggle between productive work and parasitism that led to the world war, the fact being that it was the Axis states that posed a deathly challenge to this parasitism the world over. New Zealand, despite the Labour Government measures in 1935, true to Social Democratic form, did not go beyond those limited measures, despite their success, and despite the promises the party had made in its 1934 election manifesto. Again, Social Democracy posed no real challenge to the system of world trade and banking that was – and remains – in the hands of a few parasites.

The League was ‘openly and unashamedly Imperialist.’ One of the primary aims of ‘Fascism’ was to create autarchic or self-sufficient economics states, or geo-political blocs. Of course, with Britain being the greatest imperial power, British Fascism or National Socialism sought to re-create the Empire as an autarchic bloc, where investments would be made only within the Empire, and not placed outside the Empire, only to undermine the manufacturing the agricultural sectors of the Empire peoples. Joyce pointed out that the system of international trade and finance was the enemy of both the British and the Colonial peoples; that both were equally exploited, and granting independence to India was not going to change that situation a jot. National Socialism would end usury and exploitation in India with the same methods as in Britain.[37] What Fascism was trying to address was the iniquitous system that is today called ‘globalisation’, whereby investments can be moved out of states and indeed entire industries shut-down and relocated to cheap labour pools, and currency speculators can make vast fortunes overnight by destroying entire economies. That is the system that won the Second World War against the Axis and that is the system that has driven the world to the present debt crisis, as it inevitably would. That is the system for which the Allied troops fought and died, just as the same plutocratic wire-pullers of ‘democracy’ declare war on states that are problematic to the ‘new world order’.

Finally, Joyce addressed the matter of foreign policy. Even then the war drums were being beaten against Germany, Italy and Japan. Joyce saw the keystone of world peace and order being an alliance between Britain and Germany with the assistance of Italy, which would form a bulwark against both international finance and Communism. From the 1920s, when Hitler wrote Mein Kampf, an alliance with Britain and Italy was envisaged as the cornerstone of Germany’s future foreign policy, Hitler definitively stating: ‘In the predictable future there can only be two allies for Germany in Europe: England and Italy’.[38] Was this mere cant, albeit dictated a decade before Hitler came to Office, while sitting in a jail following the abortive Munich putsch? Hitler in both public and private pronouncements always affirmed his admiration for the British Empire and the kinship that should have existed between the Third Reich and the Empire. Like Joyce, he believed that the two would be a great stabilising force in the world, and legitimate scholarship has only confirmed these views.

Captain A H M Ramsay, Conservative Member of Parliament for Midlothian and Peeblesshire from 1931 until his detention through 1940-1944, under Defence Regulation 18B along with Mosley and 1000 others, wrote after the war a volume much in the mode of Joyce’s Twilight and NS Now not only in regard to the war but also the takeover of Britain by international finance. Joyce had been a member of Ramsay’s Right Club that campaigned against war with Germany.[39] Like Joyce, Ramsay pointed to the Judaic character of the Puritan revolutionary zealots, whose armies ‘marched around Scotland, aided by their Geneva sympathisers, dispensing Judaic justice’.[40] Ramsay proceeds to consider the formation of the Bank of England with the encumbering of Britain with a National Debt; a matter that is dealt with in relative detail by Joyce in Twilight. Ramsay points out that the officialdom of ‘world Jewry’ had ‘declared war’ on Germany as soon as Hitler assumed Office. An ‘international economic boycott’ was declared by the World Jewish Economic Federation, headed by Samuel Untermeyer from the USA, who wrote in The New York Times of a ‘holy war’ against Germany, in which both Jew and Gentile must embark, while the Jews were the ‘aristocrats of the world’.[41] The Jewish leadership through its influence on politics, business and media the world over, hoped to economically strangle Germany. They could not ruin Germany through such means however, because the Hitler regime’s banking and trade reform not only withdrew Germany from the international finance system, but through barter proceeded to capture the markets of central Europe and South America. As Joyce was to emphasise in Twilight, this was the real cause of the world war; a conflict between two systems, one productive and creative, the other parasitic and exploitive.

It should be pointed out that Ramsay enjoyed the friendship and confidence of British Prime Minster Neville Chamberlain in the moths immediately preceding the World War. Ramsay alludes to Chamberlain’s guarantee to assist Poland in the event of invasion on the basis of a supposed Germany ultimatum that transpired to be fraudulent,[42] and that Germany had sought for months a negotiated solution for the return of Danzig and the ‘Polish Corridor’ to Germany, while Poland resorted to what today would be called ‘ethnic cleansing’ of the Germans within Poland; a matter which will be considered further.

Ramsay points out that Hitler had ‘again and again made it clear that he never intended to attack or harm the British Empire’. [43] Indeed, what is called the ‘Phoney War’ ensued, where no real fighting was taking place. The situation changed immediately Churchill became Prime Minister. Then the previous policy of only bombing military targets was reversed, and British Bomber Command was ordered to bomb civilian targets, a strategy that would eventually lead to the deaths of hundreds of thousands of German civilians by the end of the war, the fire-bombing of Dresden,[44] Hamburg, Berlin and other German cities going down in infamy as obliterating in deadly infernos more victims than the atomic bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

Actions speak louder than words, as it is said, and Hitler on numerous occasions offered his hand of friendship, while still in a position of strength, indeed winning the war. One of the most notable occasions is that involving the British invasion of Dunkirk, around which much nonsense about British heroism continues to be spoken. Ramsay cites the pre-eminent official British military historian Captain Liddell Hart. This nonsense continues despite Hart’s book on World War II, The Other Side of the Hill, having been published in 1948, with chapter 10 entitled ‘How Hitler beat France and saved Britain’. Ramsay comments that the chapter would ‘astound all propaganda-blinded people… for the author therein proves that not only did Hitler save this country; but that this was not the result of some unforeseen factor, or indecision or folly, but was of set purpose, based on his long enunciated and faithfully maintained principle’. Hart details how Hitler halted the Panzer Corps on 22 May 1940, allowing the British troops to escape back to Britain. Hitler had cabled Von Kleist that the armoured divisions were not to advance or fire. Von Kleist ignored the order, and then came an ‘emphatic order’, according to Von Kleist, that he was to ‘withdraw behind the canal. My tanks were kept halted there for three days’.[45] Hart records a conversation between Hitler and Marshall Von Runstedt two days later (24 May):

‘He [Hitler] then astonished us by speaking with admiration of the British Empire, of the necessity for its existence, and of the civilisation that Britain had brought into the world… He compared the British Empire with the Catholic Church – saying they were both essential elements of stability in the world. He said that all he wanted from Britain was that she should acknowledge Germany’s position on the Continent. The return of Germany’s lost colonies would be desirable but not essential, and he would even offer to support Britain with troops, if she should be involved with any difficulties anywhere. He concluded by saying that his aim was to make peace with Britain, on a basis that she would regard compatible with her honour to accept’. [46]

Captain Hart comments on the above: ‘If the British army had been captured at Dunkirk, the British people might have felt that their honour had suffered a stain, which they must wipe out. By letting it escape, Hitler hoped to conciliate them’.[47] Hart alluded to the pro-British sentiments in Mein Kampf and the manner by which Hitler did not deviate from his desire for an alliance with Britain. As we now know, so far from the British people being cognisant of the equanimity of Hitler towards them, the propaganda machine merely used this to further inflame them toward war, and Dunkirk had ever since been portrayed as a great feat of British moral courage.

Even during the early 1920s, when Hitler was in jail dictating Mein Kampf he realised that any future goodwill between Germany and Britain relied on the question as to ‘whether the exiting influence of the Jews is not stronger than any understanding or good intentions and will this frustrate and nullify all plans’.[48] Mosley, Ramsay, Admiral Sir Barry Domvile and hundreds of others jailed under 18B, who sought peace with Germany, were aware of this also. However, there were still prominent people within Britain who were free, to whom Hitler might appeal for peace, and it is presumably with these in mind that Hitler kept open the prospect of a negotiated peace with honour.

However, eminent people who hoped for a negotiated peace with Germany were no match for the war party and its backers. Winston Churchill, whose drunken, opulent lifestyle had got him into debt, led the war party. He had personal reasons for assuring the destruction of Hitler, even if that also meant the destruction of the British Empire; which, of course, it did. By 1938 Churchill was bankrupt, and Chartwell House was about to be put on the market. A few days before however Sir Henry Strakosch, the South African Jewish mining magnate and financial adviser, came to the rescue and agreed to pay off Churchill’s debts.[49] Churchill had whored himself to international finance for the sake of £18,000, and in so doing doomed the lives of millions and the survival of the British Empire. Strakosch was financial adviser to General Smuts of South Africa, and in 1920 drafted the blueprint for the Reserve Bank of South Africa.[50] He has also served as adviser on setting up the Reserve Bank of India. Like the US Federal Reserve Bank and other central banks throughout the world, the reader should not be confused into thinking that these acted as state banks issuing state credit, even when they were, like the Reserve Bank of New Zealand, nationalised. These central banks were based on plans provided by individuals such as Strakosch, the Bank of England’s Sir Otto Niemeyer, and Warburg in the USA. The thraldom of most states to international finance, from which Germany, Italy and Japan had broken free, is the most significant cause of World War II, as explained by Joyce in Twilight.

Since the 1920s Churchill’s financial adviser for his stock market dealings had been Bernard Baruch, the international financier who had run the US War Industries Board during the First World War I, and had become the virtual dictator of the USA during the war years.[51] Nothing would or could divert Churchill from leading Britain into war with Germany.

To Germany

During the Munich crisis in 1938 Joyce foresaw the coming war, and the quandary that placed him as an avidly pro-British devotee of National Socialism and Anglo-German accord. He told Macnab that in the event of war, he could not fight against Germany in the service of international finance but neither could he be a conscientious objector and evade national service. He had already envisaged sending Margaret to Ireland with Macnab, while he would go to Germany, perhaps to fight the Russians[52].

Mosley’s answer was to immediately issue a call to his supporters to fully support the war effort once the war that he had vigorously campaigned against, had eventuated, while he and 800 of his followers were detained under Emergency Defence Regulation 18B. Mosley’s order stated that ‘Our members should do what the law requires of them; and, if they are members of the armed Forces or services of the Crown, they should obey their orders and, in every particular, obey the rules of the Service’. However, it was also a call to ‘stand-fast’ against the ‘corrupt Jewish money-power’ and ‘to take every opportunity within your power to awaken the people and to demand peace’.[53]

Among the first to die in the war were two Blackshirts, Kenneth Day and George Brocking, while on an RAF daylight bomber raid on Brűnsbuttel.[54]

While Joyce campaigned with his National Socialist League, and Mosley held meetings attracting the largest audiences ever seen in Britain to the very eve of war, Joyce also sought to widen his campaign. He was involved in an anti-war campaign with Lord Lymington, Conservative MP, and an early advocate of agricultural self-sufficiency and organic farming,[55] also a particular concern of both Joyce and the BUF.[56] Lord Lymington and Joyce created the British Council Against European Commitments. Lymington’s group joined with a similar organisation founded by Hastings William Sackville Russell, Lord Tavistock (later Duke of Bedford) and emerged as the British People’s Party (BPP), the policy of which not only included peace, but in particular advocacy of banking reform.[57] Joyce had confided in Beckett that he would probably go to Germany in the event of war, and Beckett left the League to become General secretary of the BPP. It is often commented that there was a fallen out between Joyce and Beckett, but, as will be seen, they remained steadfast friends.

As forebodings of war approached in 1939, one of the first to depart from Britain to Germany was Mrs Francis Dorothy Eckersley, a member of the BUF, whose son was at school there. Mrs Eckersley was to play a role in the Joyce’s settling in Berlin. Before Macnab visited Berlin, Joyce had asked him to take a message to Christian Bauer, asking whether Goebbels would arrange for the immediate naturalisation of Joyce and his wife, should they settle in Germany.[58] Defence Regulation 18B was about to be passed when Joyce received news from Macnab that naturalisation would be granted. He then received news from an MI5 agent to whom he given information on Communist activities, that it was likely he would be arrest under 18B within a matter of days.[59] The Joyce’s left for Germany on 26 August 1939, William convinced that imprisonment in Britain during the war would mean unbearable suffering for Margaret.

To the Joyce’s dismay, Christian Bauer did not have the influence in Berlin that had been assumed, and he had been ‘called up’. However, Mrs Eckersley did have connections with the Foreign Office, and Joyce was able to secure a part-time job as a translator of German scripts.[60] Within days, war had been declared by Britain against Germany, a declaration that was not met by the Germans with any more jubilation than it was met by the Joyces and many other Britons. In England, meanwhile Mosley was holding the largest rallies in British Union history, and just two months previously the biggest indoor hall in England had been filled with 20,000 people to hear Mosley.[61] Mosley was arrested under 18B on 23 May 1940, and his wife Diana on 29 June.[62] Captain Ramsay MP, and Admiral Sir Barry Domvile CB, founder of the Link, which had also campaigned for Anglo-German cooperation, were among the 1000 others.[63]

Mrs Eckersley’s friends had been at work to secure Joyce a position, and Dr Erich Hetzler, an official in the Foreign Office, who had studied economics in England, interviewed him. It is notable that during the interview Joyce explained he was a National Socialist and British, but that a National Socialist in Britain was not the same as in Germany.[64] Hetzler recommended Joyce to the English-speaking department of the Reich radio service. Norman Baillie-Stewart, a former Subaltern in the Seaforth Highlanders, headed the English news service, under the direction of Walter Kamm. Joyce’s first broadcast, reading a news bulletin, took place on 11 September 1939. He did well, but drew the immediately jealousy of Baillie-Stewart.[65]

The disparaging nick-name of ‘haw-haw’, which was to become synonymous with Joyce, first appeared in the Daily Express on 14 September 1939 where the columnist, the pseudonymous Jonah Barrington, commented on a broadcast from Germany: ‘A gent I’d like to meet is moaning periodically from Zeesen. He speaks English of the haw-haw, damit-get-out-of-my-way variety, and his strong suit is gentlemanly indignation’.[66] The name was picked up by British propaganda, and stuck, like the name of Quisling was to become synonymous with ‘traitor’.

Ironically, Barrington was describing Baillie-Stewart. Barrington and the media ran with the typically banal propaganda image, and ‘Lord Haw-Haw’ was introduced to the public as a figure of ridicule. Lord Haw-Haw soon became conflated with Joyce and stuck, since Joyce would become the leading British broadcaster, despite his own voice, affected by the broken nose he had since childhood, not being suggestive of the ‘Bertie Wooster’ type figure that Barrington was trying to portray.[67] Other half-witted attempts at satire by Barrington, with names such as The Whopper, Uncle Boo-Hoo and Mopey, fell by the way, while Lord Haw-Haw remained. It was Lord Donegal, writing for the Sunday Dispatch, who suggested that Lord Haw-Haw might be Joyce. However, the voice that he asked Macnab, then a volunteer ambulance driver, to hear, was Baillie-Stewart, and Macnab could reply honestly that it did not sound anything like Joyce.[68]

Joyce could now apply for naturalisation, and correctly recorded his birthplace as New York.[69] Margaret was employed writing women’s features for the radio network, and became known as Lady Haw-Haw. The broadcasts were widely listened to in Britain. The matter of the identities of Baillie-Stewart and William Joyce were soon resolved by the British, but ‘Lord Haw-Haw’ stuck with Joyce rather than with Baillie-Stewart,[70] another reflection of the puerility of British war propaganda. Comedians began to lampoon Lord Haw-Haw. The deaths of millions of Britons and Germans were such a whopping good laugh for those who could avoid service by larking about on the Home Front, while Mosleyites were among the first to enlist and die.

Interestingly, Cole discusses the insistence of ‘upper class’ origins for William Joyce by the British propaganda machine, and hence the maintenance of the ‘Lord Haw-Haw’ myth as an aristocratic ‘traitor’, perhaps also reminding audiences of Sir Oswald Mosley’s aristocratic birth, and the similar backgrounds of others who had sought conciliation with Germany and who had seen Fascism and National Socialism as a means of transcending class divisions. Cole writes: ‘The theme of the aristocratic traitor aroused such an immense public response that the jeering appeared to be directed as much at the traditional British upper classes as at an unknown traitor in Germany’.[71] The irony was that Joyce was the very antithesis of the character portrayed by British propaganda, as indicated by the opening anecdote of this introduction, and he lived simply and without thought of his material well-being.

A survey by the BBC concluded that Joyce was getting six million regular listeners daily, and 18,000,000 occasional listeners. The reasons for this included not only the mirth that had been directed at Lord Haw-Haw, but also that the broadcasts focused on ‘undeniable evils in this country… their news sense, their presentation’, making them ‘a familiar feature of the social landscape’.[72]

In early 1940 the Buro Concordia was formed under the direction of Dr Hetzler, which would focus on explaining National Socialism to English listeners. Joyce would lead the team and write the programmes. He refused insistent offers of a salary increase. The first programme was aired in February 1940, under the name of the New British Broadcasting Station, transmitting for half an hour from East Prussia, albeit under sparse conditions and resources.[73]

It was at this time, in February 1940, that Joyce was asked by the Foreign Office to write a book, Twilight Over England. While Joyce addressed a British audience, which would have few chances to read the book, the Foreign Office, had intended an English language testament for audiences in the USA and India. Twilight also went into German and Swedish editions, at least. The book as will be seen, is largely an indictment of the English system of Free Trade, the influence of Jews and the iniquity of international finance.

On hindsight, reading the volume today, one might be struck by its current relevance, as the world is plunged into what American strategists approvingly call ‘constant conflict’, in extending in the hallowed name of ‘Democracy’ the system of debt and exploitation which the Axis fought seventy years ago. As Joyce tried to explain, Westminster democracy and party government is a system that has not brought any meaningful benefits to the people who have lived under the ‘Mother of all Parliaments’ for centuries, let alone to tribesmen from the deserts of Afghanistan to the jungles of New Guinea, who are having this odd system born from the merchant class of England, imposed on them by force of arms. We still live under the same system that Joyce exposed, because international finance won the war.

By mid 1940 the British had ceased considering Lord Haw-Haw as a joke and were worried by what they thought was his inside knowledge of events in Britain. Other secret Anglophone broadcasting stations were planned under Buro Concordia.[74]. Meanwhile, Joyce’s commitment to Britain was indicated by his having defaced his British passport so that after it had expired it could not be used by German Intelligence, which was eager to obtain such passports.[75] So much for disloyalty.

In July 1940 Hitler made a peace offer to Britain, and Joyce was optimistic. On ‘Workers’ Challenge’, a broadcasting service pitched specifically to British workers, Joyce stated that British workers and German workers did not wish to fight each other. The British Communists had been saying that the war was between capitalist powers and was not a workers’ fight, until the party-line was reversed when Germany and the USSR came into conflict. ‘Workers’ Challenge’ called for a workers’ revolt against Churchill and a peace that would have nothing to do with the nazification of Britain. Of coursed, Churchill was committed to unconditional surrender, and the chance to save the Empire and Europe was rejected for the sake of Churchill’s ego, or perhaps mainly due to his £18,000 debt to Strakosch and his friendship with ‘Barney’ Baruch (?). As Joyce commented on his programme on 23 July, the rejection of peace would bring tragedy to England, and if Britons remained silent then it must be assumed that they consented to their own annihilation.[76] Joyce was prescient. Is there still doubt? While it might be a cliché to say that British won the war but lost the peace, that is beyond rational doubt. As for the impact of ‘Workers’ Challenge’, a BBC survey found that it had a ‘heavy following’, that ‘the following grows’, and that a lot of Joyce’s remarks ‘were true’.[77]

On 28 August the first air raid casualties in Berlin occurred. Both Joyce and the CBS foreign correspondent William Shirer, epitome of the anti-Nazi propagandist, were at the broadcasting house. Shirer, who had avoided meeting the ‘traitor’ for a year, noted in his diary that Lord Haw-Haw ‘in the air-raids has shown guts’.[78] Joyce went out to see the damage and was ‘profoundly moved’ by the devastation. Already there were comments on the civilian targets of the British, in contrast to the military objectives of the Luftwaffe, but could anyone in Germany have envisaged the criminal fire-bombing of defenceless German cities that was to become the speciality of Bomber Command?

Shirer, the inveterate anti-Nazi whose book The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich became a classic history,[79] nonetheless observed Joyce as ‘an amusing and even intelligent fellow’, ‘heavily built and of about five feet nine inches, with Irish eyes that twinkle’.[80] He noted that Joyce had a deep hatred of capitalism. ‘Strange as it may seem, he thinks the Nazi movement is a proletarian one which will free the world from the bonds of “plutocratic capitalists”. He sees himself primarily as a liberator of the working class’.[81]

Shirer’s quip about the ‘strangeness’ of Joyce’s view of National Socialism as a movement fighting capitalism is perhaps best explained by Shirer’s own ignorance as to the character of both National Socialism and the war.[82] The reader will see the anti-plutocratic character of National Socialism explained in Twilight, a copy of which Joyce gave to Shirer.

Twilight was published in September 1940, by Santoro, an elderly Italian who owned a Berlin publishing house, Internationaler Verlag, the English edition running to 100,000 copies.[83] They were distributed at POW camps, where there were efforts to recruit for a Legion of Saint George (also known as the British Free Corps) as a unit of the Waffen SS to fight on the Eastern Front (not against fellow Britons).[84]

After a year of delays, the Joyce’s were German citizens. In 1941 Joyce registered for military service and was put in a reserved category. Joyce was now permitted to reveal his identity and stated:

‘I, William Joyce, left England because I would not fight for Jewry against Adolf Hitler and National Socialism. I left England because I thought that victory which would preserve existing conditions would be more damaging to Britain than defeat’.[85]

On 11 May 1941 Deputy Fuhrer Rudolf Hess reached Scotland on his ill-fated peace mission. It was undertaken at a time when war between the USSR and Germany was approaching, and the German authorities were obliged to repudiate the Hess mission as the lone efforts of someone who had become mentally unhinged. Perhaps Hess was unbalanced if he thought he could overcome the war party led by Churchill, but there was still thought to be a prominent peace party within influential circles who aimed for a negotiated peace. Hess had flown to Scotland in the hope of talking with the Duke of Hamilton, who was thought to be among the peace party. It is known that Hess had long been discussing possibilities of a peace mission to Britain, with Hitler’s knowledge, and that Hess’ friend Albrecht Haushofer had been in contact with the Duke of Hamilton.[86] New evidence has come to light that Hess probably did fly to Britain with Hitler’s approval. British historian Peter Padfield states that Hess brought with him to Britain detailed peace proposals from Hitler. The proposals asked for Britain’s neutrality in a coming conflict with the USSR, in return for which Germany would withdraw from Western Europe and would have no claims on Britain or the Empire.[87] Of course, such proposals were perfectly in keeping with the foreign policy aims that Hitler had desired since the 1920s, as we have seen previously. The proposals from Hitler specified German aims in Russia and even stated the precise time of the German offensive. Padfield remarks: ‘This was not a renegade plot. Hitler had sent Hess and he brought over a fully developed peace treaty for Germany to evacuate all the occupied countries in the West’.[88] Padfield also remarks on a significant ‘negotiated peace’ faction in Britain, and the ruin that peace would have meant for Churchill’s career. There is also allusion to this peace faction including the Royal Family.

Joyce expected he would soon die, whether fighting the Russians, during an air-raid or hanged. Awarded the War Merit Cross 1st Class, a civilian medal, which meant little to him, he was called up to the home guard, the Volkssturm, and he started training with weapons.[89] During the course of an air-raid, confined in a shelter, he proceeded to teach a French journalist English songs, which drew the attention of an air-warden. When Joyce refused the order to quieten a scuffle ensued, Joyce received a cut lip, and the warden a black eye. The air-raid warden stated that Joyce would be reported. Bellowing with laughter at the absurdity of the situation, Joyce was duly notified that he was charged with ‘sub-treason’, and that the warden had been the personal chauffer of Freisler, president of the People’s Court. His employers warned him that the charge was more serious than he assumed. However, the court and all traces of the documentation as well as Freisler’s chauffeur were buried in rubble from an air-raid and so was the charge of ‘sub-treason’.[90]

At the suggestion that the Joyces obtain false papers with the view to escaping as the war drew to a conclusion, Joyce was furious and adamant that ‘soldiers cannot run away, so why should I?’[91] For Joyce, from boyhood to the end of his life, honour an integrity were paramount, courage an instinct.

With Berlin in ruins, the staff of Buro Concordia prepared to relocate. With the impending Russian occupation of the city, the staff of the English Language Services proceeded to Apen, a small town between Bremen and the Dutch border, although Joyce would have preferred the barricades with his Volkssturm colleagues.

Finale

On 30 April 1945 the staff were called together and told of Hitler’s death. Lord and Lady Haw-Haw made their final broadcasts that day. Joyce reiterated what he had always said:

‘Britain’s victories are barren. They leave her poor and they leave her people hungry. They leave her bereft of the markets and the wealth that she possessed six years ago. But above all, they leave her with an immensely greater problem than she had then. We are nearing the end of one phase of Europe’s history, but the next will be no happier. It will be grimmer, harder and perhaps bloodier. And now I ask you earnestly, can Britain survive? I am profoundly convinced that without German help she cannot’.

Is there any reader who is so ignorant or so naïve, other than the ideologically or ethnically biased, who can deny that Joyce has been proved correct? Britain lost her Empire, lost her markets, the Commonwealth and colonial peoples were detached from her and left to wallow in Third World poverty, or become colonies of a US led world order, and debt became more than ever the preferred method of economics.

Orders came from Goebbels, the first from the Reichsminister that had acknowledged them, that the Joyces were not to fall into Allied hands. However, attempts to get them to neutral Sweden via Denmark or to Eire, were abortive. They ended up in Flensburg, back in the crumbling and occupied Reich. Joyce, as was his habit, adopted a rascally attitude even now, and played what he called ‘Russian roulette’ by greeting British soldiers, to see if they would recognise his voice. On a stroll back from the woods he encountered two officers collecting firewood, and approached them offering some sticks. One of the officers, Lieutenant Perry,[92] a returning Jewish refugee serving as an interpreter, a type that was now swarming over Germany in the wake of the Allied occupation, recognised Joyce’s voice. They pursued Joyce in a vehicle, and Perry asked, ‘You wouldn’t happen to be William Joyce would you?’ Joyce reached for the less than convincing fake identity papers that had been given to him by the Germans and was shot by Perry, the bullet entering through Joyce’s right thigh and passing through the left.[93]

The military authorities promptly called on Margaret Joyce at the lodging of an elderly widow, who was also detained, but quickly released, albeit not before her household food rations had been looted by the liberators.

Joyce’s first court appearance on treason charges was held at the Old Bailey on 17 September 1945. He entered a ‘not guilty’ plea. The main problem for the prosecution was in regard to whether Joyce was a British national under the protection of the Crown when he made his broadcasts in Germany. Joyce had never been a British citizen, and he had obtained a British passport for his move to Germany by making a false declaration. Two of the three charges could not be upheld. The case reached the House of Lords. However, Joyce was in no doubt that his hanging was required, and his defence team had even received death threats should he be acquitted. Joyce was hanged on the basis that because he had a British passport he was under the protection of the Crown when he started his broadcasts, and therefore committed high treason. The charge was dubious at best. He had never used his British status for protection at any time, and there is no reason to believe he would have in any circumstances. He moved to Germany with the intention of become a German citizen as promptly as possible, although German officialdom had been tardy in the process. Joyce was hanged on a passport technicality. Judgement was passed on 18 December 1945 to dismiss the appeal. Lord Porter dissented, stating that it was by no means clear that Joyce could have been considered to have owed allegiance to the Crown at the time of the broadcasts.[94]

Joyce on being told the decision wrote to Margaret that it was a relief the matter was over and that he found it undignified to have to plead for his life before his enemies, and to ‘observer their pretence at “fair play”’. Amidst the petty vengefulness of a befuddled and war-worn people, The Manchester Guardian nonetheless questioned the appropriateness of death sentences for Joyce and John Amery (whose trial had lasted eight minutes) for views that ‘were once shared by many who walk untouched among us’. Joyce appreciated the acknowledgment of his sincerity by the Guardian. His friends remained steadfast, and John Macnab was particularly active on Joyce behalf. Macnab, an avid Catholic, remarked on his last visits to Joyce that ‘being with him gave a sense of inward peace, like being in a quiet church’.[95] Some of his former teachers at Birbeck College, remembering the likeable and hardworking student, asked the prison Governor to relay their well-wishes to Joyce. He handed his brother Quentin his final message:

‘In death, as in this life, I defy the Jews who caused this last war: and I defy the power of Darkness which they represent. I warn the British people against the aggressive Imperialism of the Soviet Union.

‘May Britain be great once again; and, in the hour of the greatest danger to the West, may the standard of the Hakenkreuz be raised from the dust, crowned with the historic words “Ihr habt doch gesiegt”. I am proud to die for my ideals; and I am sorry for the sons of Britain who have died without knowing why’.

Joyce’s old friend, the one-timer Labour Party stalwart John Beckett, wrote to him in his final days: ‘Our children will grow up to think of you as an honest and courageous martyr in the fight against alien control of our country … That is how we shall remember you, and what we will tell our people’.[96] It has only recently been known that Beckett’s departure from the National Socialist League was for reasons other than a falling-out with Joyce. Beckett referred to this when writing to Joyce:

‘No one knows better than myself the sincerity of the beliefs which led to the course of action you chose. You remember we discussed the position in 1938, and the disagreement and respect I showed for your opinion then, remains’.[97]

Joyce replied in a letter that was intercepted and never given to Beckett:

‘Of course I remember, quite vividly, how we discussed the situation in 1938. I do not, in the most infinitesimal degree, regret what I have done. For me, there was nothing else to do. I am proud to die for what I have done’.[98]

Beckett in his farewell wrote to Joyce: ‘Goodbye, William, it’s been good to know you and there are few things in my life I am prouder of than our association. Yours always, John’.[99]

Joyce took holy communion, wrote to his wife and to Macnab, and at 9:00 am precisely he was taken from his cell by the hangman, Albert Pierrepoint and hanged.[100]

On the morning of 3 January 1946, the day of his execution, a crowd of 300 gathered outside Wandsworth prison; most to gloat but some to pay their final respects. Some of the crowd, on the notice of Joyce’s execution being posted up, set themselves apart from the crowd and gave the Fascist salute in Joyce’s honour.

Notes

[1] J A Cole, Lord Haw-Haw: The Full Story of William Joyce (London: Faber and Faber, 1987), 307

[4] Rebecca West, The Meaning of Treason (London: The Reprint Society, 1952), 3.

[6] One might recall the fates of Dr Robert Faurrison in France, Fred Leuchter in the USA, David Irving in England, Dr Joel Hayward in New Zealand, Ernst Zundel in Canada, et al.

[7] K R Bolton, Artists of the Right (San Francisco, Counter-Currents Publications, 2012), 97-119. Pound, stranded in Italy with his wife when the USA entered the war, broadcast for Italy on a programme called ‘Europe Calling’, analogous to Joyce’s broadcasts named ‘Germany Calling’. Handed over to US troops after the war by Italian partisans, Pound was confined in an animal cage under the scathing Pisan sun. The embarrassment of trying and hanging for treason one of the world’s greatest literary figures was avoided by declaring Pound unfit to stand trial, and he was confined to a mental asylum for thirteen years, after which, still undiagnosed or treated for any supposed ‘mental illness’, he was permitted to leave the USA and return to Italy.

[8] Cole, op. cit., 22-23.

[11] Richard Thurlow, Fascism in Britain (London: Basil Blackwell, 1987), 51.

[13] Cole., op. cit., 30.

[15] Oswald Mosley (1968) My Life (London: Black House Publishing, 2012), 294.

[19] Thurlow, op. cit., 98.

[20] In 1925 Beckett become the youngest Labour MP of his time, at the age of 30. Becoming increasingly radical, he was expelled from the Labour party and lost his seat in 1931, joining the BUF two years later.

[22] Jeffrey Hamm, Action Replay (London: Howard Baker, 1983), 151.

[26] Randolf Churchill in letter to The Spectator, 27 December 1963, cited by Mosley, My Life, op. cit., 363.

[27] Zeev Sternhell, Neither Left Nor Right: Fascist Ideology in France (Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1986); The Birth of Fascist Ideology (Princeton, 1994).

[29] K R Bolton, ‘Geoffrey Potocki de Montalk: New Zealand Poet, “Polish King”, and “Good European”’, Counter-Currents Publishing, http://www.counter-currents.com/2010/08/count-potocki-de-montalk-part-iii/

[30] William Joyce, National Socialism Now, 1939, Chapter 1.

[32] Karl Marx, The Communist Manifesto (Moscow: Progress Publishers, 1975), 71-72.

[33] Joyce, NS Now, op. cit., Chapter 2.

[34] K R Bolton, The Banking Swindle (London: Black House Publishing, 2013), 103-120.

[37] W Joyce, NS Now, op. cit., Chapter 4.

[38] Adolf Hitler (1926), Mein Kampf (London: Hutchinson & Co., 1969), 570.

[39] Ramsay was one of the many veterans who had served in the First World War ‘with gallantry’ (Griffiths, 353) who were imprisoned under Regulation 18B. Members of the Right Club included Admiral Wilmot Nicholson (another First World War hero), Mrs Frances Eckersley, who was to assist the Joyce’s on their arrival to Germany; and the Duke of Wellington. Richard Griffiths, Fellow Travellers of the Right (London: Oxford University Press, 1983) 353-355.

[40] A H M Ramsay, The Nameless War (1952), 17.

[42] Ramsay, ibid., 59-60.

[44] David Irving (1966), The Destruction of Dresden (London: Futura Publications, 1980).

[45] Ramsay, op. cit., 67.

[46] Cited by Ramsay, ibid., 68.

[48] Hitler, Mein Kampf, op. cit., 575.

[49] David Irving, Churchill’s War Vol. 1 (Western Australia: Veritas Publishing, 1987), 104.

[50] Stephen Mitford Goodson, Inside the Reserve Bank of South Africa (2013), 67-69.

[51] David Irving, op. cit., ., 14.

[53] Stephen Dorril, Black Shirt: Sir Oswald Mosley and British Fascism (London: Penguin Books, 2007), 466.

[55] Griffiths, op. cit., 319.

[56] The BUF had its own notable agricultural expert, Jorian Jencks, author of BUF rural policies.

[57] Griffiths, op. cit., 352.

[58] Cole, op. cit., 82-83.

[61] Robert Skidelsky, Oswald Mosley, 440.

[64] Cole, op. cit., 108.

[78] Cited by Cole, ibid., 170.

[79] William L Shirer, The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich (Secker and Warburg, 1977).

[80] Recall the description of Joyce’s appearance by Shirer with that of Rebecca West.

[81] Cited by Cole, op. cit., 174-175.

[82] Shirer was listed as a Communist sympathiser in a 1950 US publication, Red Channels: The Report of Communist Influence in Radio and Television, based on FBI documents. Shirer had been a member of the Committee for the Prevention of World War III, founded in the USA in 1944, which lobbied for the elimination of Germany. Among its members were James P Warburg, ‘ideologue’ of the society and a scion of the influential Warburg banking dynasty. Did Shirer ever regard the alliance between plutocrats and Leftists against the Axis to be ‘strange’? For several years after the war the Committee’s aims were implemented under the so-called Morgenthau Plan, named after US Secretary of the Treasury Henry Morgenthau Jr., a supporter of the society. The Morgenthau Plan attempted to exterminate the German people through starvation, until being reversed by the Marshall Plan several years after the war, when it was realised that the Germans might be needed to fight the Russians, again. See: James Bacque, Crimes and Mercies: The Fate of German Civilians Under Allied Occupation 1944-1950 (London: Little, Brown & Co., 1997).

[83] Adrian Weale, Renegades: Hitler’s Englishmen (London: Weidenfield and Nicolson, 1994), 36.

[85] Cole, op. cit., 190.

[86] Wolf Rudiger Hess, My Father Rudolf Hess (London: W H Allen, 1986), 66-67.

[87] Jasper Copping, ‘Nazis “offered to leave Western Europe for free hand to attack USSR”’, The Telegraph, 26 September 2013, http://www.telegraph.co.uk/history/10336126/Nazis-offered-to-leave-western-Europe-in-exchange-for-free-hand-to-attack-USSR.html

[88] Peter Padfield, Hess, Hitler and Churchill (Icon books Ltd., 2013), cited by Copping, ibid.

[92] The large numbers of Jewish lawyers and interpreters who entered Germany with the Occupation forces were given false names. See Cole, op. cit., 247.

[96] Cited by Beckett’s son, the author and journalist Francis Beckett, ‘My Father and Lord Haw-Haw’, The Guardian, 10 February 2005, http://www.theguardian.com/books/2005/feb/10/secondworldwar.world

[100] Adrien Weal, op.cit., 195.

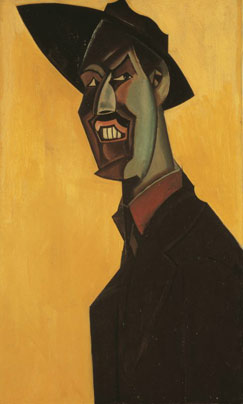

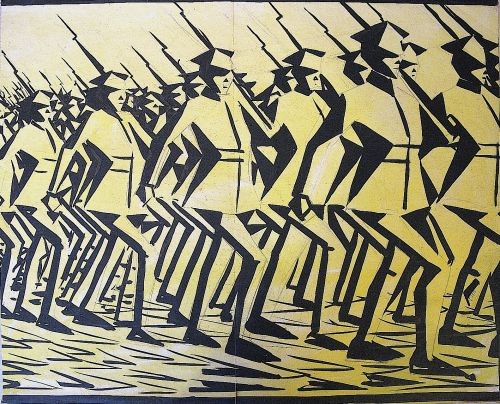

Firstly, his enormous breadth of talent overwhelms today’s overly-specialised critics in their imposed pigeon-holes: some still call him England’s greatest Twentieth Century portraitist and draughtsman, his substantial shelf of novels could keep another league of critics busy, and his volumes of social criticism a third. Next, nobody could be so marvellously abrasive without lots of practice, so whomever you adore from the first half of the Twentieth Century, Lewis said something snarky about him at least twice. Lastly, he had an almost magnetic attraction to being politically-incorrect, giving any sniffy modern who has not read Lewis a good excuse to dismiss him out of hand. So he is largely ignored: a big mistake.

Firstly, his enormous breadth of talent overwhelms today’s overly-specialised critics in their imposed pigeon-holes: some still call him England’s greatest Twentieth Century portraitist and draughtsman, his substantial shelf of novels could keep another league of critics busy, and his volumes of social criticism a third. Next, nobody could be so marvellously abrasive without lots of practice, so whomever you adore from the first half of the Twentieth Century, Lewis said something snarky about him at least twice. Lastly, he had an almost magnetic attraction to being politically-incorrect, giving any sniffy modern who has not read Lewis a good excuse to dismiss him out of hand. So he is largely ignored: a big mistake. Its flat, mechanistic images were fine teething-material for Lewis’s draughtsman’s eye and unerring hand, and Vorticism proved a good marketing platform for the ambitious young artist at a time when various Modernist movements seemed to run a dime a dozen: Cubism, Futurism, Tubism, Suprematism, Expressionism, Verismus (may I stop now?) all trying to cram art into an ideological suitcase that was, of course, fully branded, wholly marketable and potentially lucrative. Ultimately, after a stint as an artilleryman, Lewis returned home and moved on, while Vorticism became what veteran art-critic Brian Sewell calls “in the history of western art, no more than a hapless rowing-boat between Cubism and Futurism, the Scylla and Charybdis of the day.”

Its flat, mechanistic images were fine teething-material for Lewis’s draughtsman’s eye and unerring hand, and Vorticism proved a good marketing platform for the ambitious young artist at a time when various Modernist movements seemed to run a dime a dozen: Cubism, Futurism, Tubism, Suprematism, Expressionism, Verismus (may I stop now?) all trying to cram art into an ideological suitcase that was, of course, fully branded, wholly marketable and potentially lucrative. Ultimately, after a stint as an artilleryman, Lewis returned home and moved on, while Vorticism became what veteran art-critic Brian Sewell calls “in the history of western art, no more than a hapless rowing-boat between Cubism and Futurism, the Scylla and Charybdis of the day.” In his 1928 “The Doom of Youth,” he described a cult that plagues us yet. A society that destroys faith in the hereafter can live only for earthly life, taking refuge from death in an unnatural fixation with youth and protracted adolescence; hence maintaining the appearance of youth until it becomes ludicrous. Since real youths lack experience, achievements and contacts, “official” public youths will be older and older. Politicians, he predicted, will jump onboard with bogus youth-wings, nevertheless controlled by middle-aged party-apparatchiks; presupposing the Hitler Youth Movement and even the fat, balding and comically-inept, 50-year-old, KGB “youth representatives” sent to international youth conferences to mingle with real Western and Third World teenagers into the 1980s. On to then-trendy monkey-gland treatments, more complicated cosmetics and foundation-garments, real and fake exercise regimens and the rest, until nowadays where in any Florida geriatric home (“God’s waiting-room,” my dad calls it) are toothless, pathetic wrecks hobbling around dressed as toddlers.

In his 1928 “The Doom of Youth,” he described a cult that plagues us yet. A society that destroys faith in the hereafter can live only for earthly life, taking refuge from death in an unnatural fixation with youth and protracted adolescence; hence maintaining the appearance of youth until it becomes ludicrous. Since real youths lack experience, achievements and contacts, “official” public youths will be older and older. Politicians, he predicted, will jump onboard with bogus youth-wings, nevertheless controlled by middle-aged party-apparatchiks; presupposing the Hitler Youth Movement and even the fat, balding and comically-inept, 50-year-old, KGB “youth representatives” sent to international youth conferences to mingle with real Western and Third World teenagers into the 1980s. On to then-trendy monkey-gland treatments, more complicated cosmetics and foundation-garments, real and fake exercise regimens and the rest, until nowadays where in any Florida geriatric home (“God’s waiting-room,” my dad calls it) are toothless, pathetic wrecks hobbling around dressed as toddlers.

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

William Joyce, more infamously known to history as “Lord Haw Haw,” the epitome of a British Traitor, was hanged on the basis of a passport technicality on January 3, 1946. Like the name “Quisling” (see Ralph Hewin’s excellent biography Quisling: Prophet Without Honour) much nonsense persists about Joyce.

William Joyce, more infamously known to history as “Lord Haw Haw,” the epitome of a British Traitor, was hanged on the basis of a passport technicality on January 3, 1946. Like the name “Quisling” (see Ralph Hewin’s excellent biography Quisling: Prophet Without Honour) much nonsense persists about Joyce.

In “Him with His Tail in His Mouth” (1925), Lawrence writes “Creation is a fourth dimension, and in it there are all sorts of things, gods and what-not. That brown hen, scratching with her hind leg in such common fashion, is a sort of goddess in the creative dimension.”[21] And in “Morality and the Novel” (1925), Lawrence tells us “By life, we mean something that gleams, that has the fourth-dimensional quality.”[22] Nothing in Lawrence is ever completely clear, but it seems clear enough in these passages that he thinks that living things exist in two ways. In space and time they exist alongside other creatures, and in large measure are what they are in contrast or opposition to those other creatures. In truth, however, their being is located in a realm beyond space and time.

In “Him with His Tail in His Mouth” (1925), Lawrence writes “Creation is a fourth dimension, and in it there are all sorts of things, gods and what-not. That brown hen, scratching with her hind leg in such common fashion, is a sort of goddess in the creative dimension.”[21] And in “Morality and the Novel” (1925), Lawrence tells us “By life, we mean something that gleams, that has the fourth-dimensional quality.”[22] Nothing in Lawrence is ever completely clear, but it seems clear enough in these passages that he thinks that living things exist in two ways. In space and time they exist alongside other creatures, and in large measure are what they are in contrast or opposition to those other creatures. In truth, however, their being is located in a realm beyond space and time.

.jpg)

I would like to talk about something that has always interested me. The title of the talk is “Léon Degrelle and the Real Tintin,” but what I really want to talk about is the heroic in mass and in popular culture. It’s interesting to note that heroic ideas and ideals have been disprivileged by pacifism, by liberalism tending to the Left and by feminism particularly since the social and cultural revolutions of the 1960s. Yet the heroic, as an imprimatur in Western society, has gone down into the depths, into mass popular culture. Often into trashy forms of culture where the critical insight of various intellectuals doesn’t particularly gaze upon it.