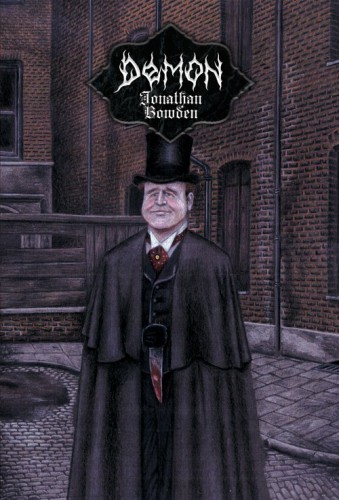

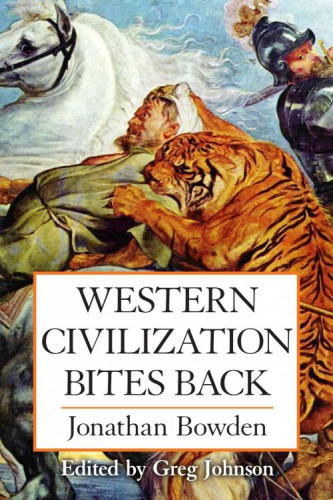

[1]The following text is a transcript by V.S. of one of Jonathan Bowden’s most entertaining lectures, which was delivered to the 25th New Right meeting in London on February 13, 2010. Although Stewart Home is the principal subject, Bowden romps through a wide field of politically correct theories, ultra-Left sects, and decadent forms of modern art.

In editing this transcription, I introduced punctuation and paragraph breaks. I also deleted a couple of false starts and added the first names of some figures.You can listen to the lecture at YouTube here [2]. Several bits were unintelligible and are marked as such. If you can understand these words, please post a comment below.

I’d like to talk about Stewart Home: communism, nihilism, neoism, and decadence. I’ve given three talks on the extreme Left. One is called “Marxism and the Frankfurt School and the New Left [3].” Another was called “The Totalitarian Politics of Nineteen Eighty-Four [4].” And another one was about the concept of brain-washing and the use by the North Koreans and the Chinese of behaviorist techniques, particularly on prisoners in the Korean War—a totally forgotten struggle now—and a novel by an Italian-American called Francis Pollini [5] that was based on those events.

I’d like to talk about Stewart Home: communism, nihilism, neoism, and decadence. I’ve given three talks on the extreme Left. One is called “Marxism and the Frankfurt School and the New Left [3].” Another was called “The Totalitarian Politics of Nineteen Eighty-Four [4].” And another one was about the concept of brain-washing and the use by the North Koreans and the Chinese of behaviorist techniques, particularly on prisoners in the Korean War—a totally forgotten struggle now—and a novel by an Italian-American called Francis Pollini [5] that was based on those events.

Stewart Home is an incredibly obscure figure who is on the margins of the cultural avant-garde, so I’m going to come to him towards the latter stages of the talk when I’ve dealt with some of the building blocks to begin with.

Most conservatives, with a small “c,” look around Western European countries like Britain today and wonder why they’re living in a mildly, but evidently Left-wing society. They wonder why they’re supposed to have won, but have actually lost. As they look around them, everything’s changed from what it was 40 to 50 years ago—every normative social value and experience—and they wonder why that has occurred.

There are many reasons for why it’s occurred, but one is the complete containment and taking over of the cultural space by what we’ll call cultural Marxism or Marxian ideas or soft Left ideas or post-communist ideas and their march through the institutions after the 1960s. But it didn’t just happen then. It had been prepared much earlier in the 20th century.

Marxism is a doctrine—before Lenin added the conspiratorial element of a vanguard party that seizes power with its paramilitary wing in a declining state—that originates from the middle of the 19th century and has a refutation of idealistic and utopian socialisms, some religious, some secular that preceded it. Marx believed that he had a science of history, that the thing was prior and determined, that history could be read like a runic pattern or the pattern of a Persian carpet, and he was the master of the dialectic that would determine humanity’s future. We now know that the nightmarish regimes that were created across the planet in the 20th century on the basis of some or all of his ideas failed, and most of them have been destroyed. But their legacy is still here.

Clare Short’s got a bit of the witness at the moment in the liberal press because of her appearance at the Chilcot Inquiry. She said something very interesting when the Soviet Union collapsed. She said, “Communism is over, but Marxism is not.” That’s a very prescient remark, because what’s happened in the Western world is that the idea that everything is economically predetermined in Marxian theory, that everything has a social dynamic which is structured and physical at the basis of economic life and it is materialistic, has been changed.

It was changed at the beginning of the 20th century by an Italian communist theorist in prison called Antonio Gramsci. He had the idea that the superstructure and the base—that which was beneath and economic and material, that which was above and philosophical and cultural—can be disjoined. They can be separated and teased apart. That’s actually a heresy in classical Marxism. But it enabled an enormous vista of struggle to be opened up right across academic, artistic, intellectual, and media-related life right across the West.

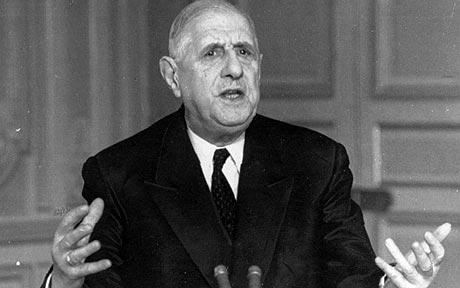

Part of the Left disengaged from the politics of vanguardism and engaged in what is now largely called cultural struggle. One of the great weaknesses of all forms of conservatism—whether Gaullism in France or Republicanism in the United States or Christian Democracy in Germany and Italy and elsewhere—is their refusal to fight cultural struggle, their refusal to believe that their enemies were in deadly earnest.

In the 1960s, persons who were regarded as “reactionary,” particularly in the academy, used to laugh at a lot of what was occurring. It was almost a joke. I’m sure most people are aware of that satire called Porterhouse Blue by Tom Sharpe which is based upon Peterhouse College, Cambridge of all these reactionary and ultra dons, people like Maurice Cowling, people like Roger Scruton who were associated with that college. They are metaphysical or deep blue conservatives, illiberal conservatives, people who were right on the edge of the conservative range of opinion before the far Right begins, as far as you can go within the mainstream, basically.

Those individuals—and I knew Cowling once (he’s dead now)—didn’t give in. But in a way they didn’t understand that in order to fight back against the tidal wave of Leftist ideas throughout the ‘’20s, ’30s, ’40s, ’50s, and thereafter you had to go further out ideologically, even if you weren’t prepared to make organizational commitments, even if it turned to fellow-traveling. You had to use Far Right ideas, even if you didn’t call them that, to fight against the Left in its militancy. Basically, conservative academics from Michael Oakeshott onwards refused to do so, absolutely refused to do so, and in doing so they basically put the noose around their own neck in relation to the forces that were coming.

Because their enemies were in deadly earnest. They wanted to transform the mindset of Western societies, and the way that they configured to do that wasn’t through vanguard parties, although they supported them, wasn’t through doctrines of social revolution, although they may have residually supported that. It was by changing the grammar that people used to think with at the advanced level.

Strangely for militant egalitarians, they used an extreme form of cultural elitism. You take the universities; you take the dons and the academics in the universities; you take the people who mark the PhDs that provide the methodology of attainment through which you get a don at the university. You then replicate that through all male and female students at the first, second, and third levels of tertiary education, never mind the people coming up from the secondary level.

Strangely for militant egalitarians, they used an extreme form of cultural elitism. You take the universities; you take the dons and the academics in the universities; you take the people who mark the PhDs that provide the methodology of attainment through which you get a don at the university. You then replicate that through all male and female students at the first, second, and third levels of tertiary education, never mind the people coming up from the secondary level.

As egalitarian education has been spread, we’re going to have a society where 30-50% go to university; there’s the University of Slough, which used to be the Poly in the Thames valley. You can do degrees in hair-dressing. You can do degrees in golf studies. You can do degrees in anything! You know, you send this away to a P. O. box number in Edinburgh, and in a couple of weeks it’s packaged, and you get a PhD in nuclear physics, then straight back in the post! This is the way it’s going!

There are a few upper-class people now who refuse to go to university. Princess Diana refused to go, partly because she wasn’t too bright, but also because it doesn’t have any social cache anymore, because if everyone goes it’s got no kudos. This is the idea! If everything is degraded, do you want to eat the bread that’s been in every other mouth? This is the thing about egalitarian ideas.

The plan of Leftist subversion, which is a wave of academics in all sorts of areas, not necessarily networked, not necessarily doing it in relation to each other, but doing it in relation to the logic of their studies. They do it in discourse after discourse.

They do it in economic theory, which before John Maynard Keynes was classical liberal methodology, Alfred Marshall being the last of that particular school, revived by F. A. Hayek and Milton Friedman in the middle of the 20th century as a dissident current that would then come back. Keynes comes first, and Marxist economists like Professor Joan Robinson at Cambridge come later.

Then you go to anthropology. The first great textbook of anthropology is Arthur de Gobineau’s book, The Essay on the Inequality of the Human Races. This begins anthropology as a subject. This is a “racist” text. Anthropology is the science, or semi-science, that always has to deny its first text, because its first text is now so offensive in relation to all of the discourses that have come after. From the early part of the 20th century, you get the growing up of various discourses which are called social or socialized anthropology: the idea that race has nothing to do with anthropology, when race is the periodic table of anthropology and is the taxonomy of the human within that particular academic discipline. You reach a situation where by the 1970s if a don at, say, the University of Sussex, an ultra-Left institution on the south coast, said that there were cardinal racial differences in intelligence between people, there would have been an absolute riot on that campus, an absolute riot which would have had to have been controlled by the police and the authorities.

One thing the Left realized throughout the 20th century is that people who are very mental and people who are very abstracted in terms of their intellect can be physically intimidated very easily. The mind and the body are so split in Western life that all you have to do is have a small mob wave their fists at a couple of dons, and they’re prostrated, and they can’t do anything, and they’re in fear of their lives, and they will write in a different way afterwards. Trotsky said in a pamphlet called The Necessity of Red Terror, which was published in 1917, that you shoot a thousand to intimidate a million. But all you need to do at many universities is lob a brick through on Fresher’s day, and people are frightened to discuss and to write about and to theorize about whole sets of ideas.

Everyone knows that there is a spectrum since the French Revolution of far Left, moderate Left, center, moderate Right, radical Right views. Since about 1968, the radical Right chunk—which is to the Right of Oakeshott, Scruton, and Cowling—has been broken off and cannot be talked about other than as critique. You can talk about how you detest these ideas. You can talk about how evil and wrong they are. You can talk about how mistaken they are. But they can’t be adumbrated in and of themselves.

This is complicated because there are certain academies, such as the French one, where that’s not always true, and this is because in France there was a very powerful intellectual fascist tradition—essentially, that’s what it was—which goes right through to today and even to the New Right. There’s a degree to which in the Sorbonne in the ’70s you could see a poster saying, “Drieu La Rochelle: lecture this afternoon.” He committed suicide of course after the war because he was a collaborationist intellectual with Otto Abetz and other people in the German cultural ministry in Paris in occupied France at that time.

So, it’s not uniform. These things are process led and dynamic. It doesn’t just happen in economics and anthropology. It happens in psychology. It happens in sexology. It happens in English literature. It happens in the creation of new discourses such as cultural studies, which is the dissemination of ideas about mass culture. And it happens in critical theory.

Critical theory is a viewpoint that’s grown up across the arts and across the humanities and even into areas of law like criminology, which can also be considered to be one of these “ologies,” one of these subjects, and other areas of history of art, aesthetics, in philosophy courses, philosophy itself and so on.

The Anglo-American world, of course, had an empirical view of philosophy largely since Hobbes, but certainly since Russell in the 20th century, and a hostility to European philosophy which meant that there was less Marxist influence here. But the trouble with Bertrand Russell’s type of philosophizing is that it doesn’t believe that any of the big questions can be answered, and therefore philosophy itself becomes slightly pointless, and a cul-de-sac where you discuss the language you use to arrive at a concept to which there are multiple interpretations and of which you are forever unsure. In and of itself, that’s the preparation—this radical, tepid uncertainty—which leads from conservatism to liberalism and from liberalism to something that’s a bit more certain and lies to the Left of it.

Everything in Western societies has moved to the Left throughout the 20th century. I am not a Christian, but you could argue that after Vatican II many Catholics became Protestants; many Protestants became liberals; many secularist liberals who are ex-Protestant moved further to the Left and adopted views that they would have regarded as semi-extreme in the past as long as they were not connected to physical force, militant working class politics, vanguardism, and the absolute politics of communism.

You have many Left-wing liberals now who have views which are to the Left of hardcore communists in the ’20s and ’30s, and they don’t realize that and they’re horrified by the atrocities of Stalin and Mao and Pol Pot and all the others. But what they don’t realize is that they have imbibed a doctrine of totalitarian niceness and squeaky clean correctness about these concepts, which existed in the way that their minds were attuned to before they became conversant with it.

This march through the institutions has also been a march through the media, because when you have an intellectual clerisy it tends to control the conceptual ideas in the society and the way that society talks to itself in modernity is through the media, and also propaganda and ideas about how you talk to the media. Most polytechnics, or post-polytechnics now—because polytechnics were once vocational institutions, of course dominated by people who tended to support the Labour Party—have now been upgraded to new universities or universities have been downgraded to new universities which are polytechnics, because if all have a degree what does it mean?

In America, you can go to a university and, outside the Ivy League, you don’t necessarily have to have the qualifications to get in. So, you have a remedial course. There’s a considerable number of people from certain types of racial minorities in those remedial courses—taught to do English, taught to do math, and then they do sports science or sports psychology. They won’t be doing physics. They won’t be doing mathematics. They won’t be doing metaphysics. They won’t be doing Shakespeare.

In America, you can go to a university and, outside the Ivy League, you don’t necessarily have to have the qualifications to get in. So, you have a remedial course. There’s a considerable number of people from certain types of racial minorities in those remedial courses—taught to do English, taught to do math, and then they do sports science or sports psychology. They won’t be doing physics. They won’t be doing mathematics. They won’t be doing metaphysics. They won’t be doing Shakespeare.

There are certain colleges now that have votes about whether Shakespeare should be on the English course. But that’s a mistake, you see, because democracy is always a mistake! When hardline Marxists allow the students to vote, the students, even though they’re liberal, often come up with more conservative results than what the professors want! That’s the logic of vanguardism: you don’t allow them to decide. You say Shakespeare is a reactionary Elizabethan bigot with undue essentialist notions that you shouldn’t permit!

The notion of essentialism has come in in the last 30 to 40 years in relation to great fads in intellectual life. It has to be understood that for the last 100 years or so all mainstream, hardcore, Western intellectual developments have been atheistic. They’ve taken atheism as read, not as something to be debated. The first great ideology after the war was existentialism, which contained many elements including a dissentient far Right strand as well.

Existentialism was replaced by a new creed, fad, wave of history, whatever you want to call it, called structuralism, which relates to ideas at the beginning of the 20th century called formalism. Then people got bored with structuralism. Structuralism was around at the time of the student revolts in the late 1960s. Not totally a Left-wing idea, but in a way bent towards the Left by certain ideas. If the revolutionary Left on campus couldn’t take an idea as read they would turn it around. Hegel was not a Left-wing thinker, but Left-wing Hegelianism emerged. Marx was part of a group of Left Hegelians with Engels. They used to meet in a beer cellar prior to the German revolution in 1848 to discuss Left theory. Similarly, Left structuralism begins to emerge, particularly with Claude Lévi-Strauss in anthropology and with Ferdinand de Saussure in linguistics.[1] These ideas relate to certain currents in modernist art in particular in the late 19th and early 20th century. If we approach this subject area we get a bit closer to Home, who nominally is the hook that I’m hanging this particular talk on.

You can’t do English at a contemporary British university—certainly outside Oxbridge, where there’s just a received canon—and not come across critical theory. Critical theory is based upon a notion called deconstruction, and most people who are intellectually minded have heard the word deconstruction somewhere floating around, floating in the back pages of The Observer color supplement, that sort of thing. They’ve heard the word.

Deconstruction is another word for post-structuralism, which is the ideology or the new fad that replaced structuralism in the ’60s and ’70s. It’s most closely associated with a thinker called Jacques Derrida, who wrote a number of books basically saying that history doesn’t exist, that biology doesn’t exist, that the writer of a text does not exist. There is only the text. There is only the grammar of the text. A painting can be a text. A poster can be a text. A film can be a text. Only the text. Nothing but the text.

It’s the view that essentialism leads to the gates of Auschwitz, which is repeated again and again as a mantra within these particular courses. They believe that any prior identity—say the statement “men and women are different,” the John and Joan book, you know, a child says, “Men and women are different”—wrong on every account! Prior essentialist agenda, revolutionary, sub-genocidal reactionary ideologies in relation to the specification of male and female. Don’t you know men and women are interchangeable? Don’t you know that they are the same? If somebody says, “But don’t they have different brains?” “Lies put about by eugenicists linked to reactionary and essentialist ideas!” Again re-routed to the ovens. “Listen to your theory!”

Of course, in these areas, to think differently from the nature of this theory is impossible, because you will not finish the course. You will not even get a 2.1, which is the sort of median level for your average student, in that course if you don’t go along with this.

Some of this thinking relates to Western ideas that go very far back, because in medieval scholasticism there’s a doctrine of hermeneutics whereby you analyze the text of the text of the text. You look inside it to see the hint of the divine which is there. And some of these ideas actually do come out of that particular trajectory. So, in some ways it’s a very ancient thing that’s been repositioned and been reused for hostile purposes. Only the core theorists in this area, Deleuze, Guattari, Derrida, and others, would actually know that is the case.

When the Enlightenment and modern scientific rationalism began and they argued that the schoolmen were concerned about the number of angels that danced on the top of a pin and philosophy was about natural process and law of nature as the Greeks believed 2,000 years before, 1,500 years before their postulations of course, there was a degree to which they’d thought they had got rid of that type of thinking. But interestingly, that type of thinking, which in some ways is very “reactionary,” has come back through these New Left ideas.

The one thinker who is partly outside all of this and has a special status as a monster within the 20th century is Martin Heidegger. Now, Martin Heidegger was an extreme essentialist and was a religious thinker who was highly influenced by these ideas of extreme hermeneutics and the peeling away of the onion of the text. Heidegger has one book that is 400 pages saying, “What is thinking?” or “What is the nature of thinking?” Heidegger wrote 80 books, all 80! Most of which have never been released.[2]

Although Heidegger is one of the most radical thinkers of the 20th century, Heidegger’s political affiliation, if only for a year between 1933 and 1934, has meant that in a sense he has become an unperson. After the war, when he was allowed to write and continued to write he used to write in the Black Forest. He had a wooden cabin in the Black Forest, and he used to commune in this particular woodland fastness, this shed almost, with nature and by himself in pure theory.

A lot of these ideas are based upon pure theory. They are based upon the idea that the bourgeois—the enemy in Marxian terms—goes to life with common sense. The Marxist goes to life with his theory! Only if you see the veil of theory before reality, the pink prism through which reality is refracted, only then can you be in history; only then are you truly alive, because you’re interpreting the dialectic of future knowledge.

Now, the irony is that these communistic systems that statally imposed these ideas on people have all collapsed. People who lived in Poland during Gomułka and other regime leaders had to do Marxist-Leninism four times a week, just like the Catholic schools that these schools replaced, where we did religion four times a week. They did Marxist-Leninist theory four times a week.

There was a Far Left party in Britain called the Revolutionary Communist Party, which was a split from the Socialist Workers’ Party, a so-called Rightist deviation within Marxist-Leninism. In 1986, they set exams for their cadres. You had to do exams on Grundrisse and Groundwork and Kapital volume I, volume II, volume III to pass exams on this sort of material just like in Poland.

People imposed this on themselves internally within the West, and yet historically these ideas have lost. These ideas have come crashing down as statal and political and architectural structures. Yet in the minds of elite Western academics, the softer non-vanguard version of these ideas are alive and well and kicking and are in control.

People imposed this on themselves internally within the West, and yet historically these ideas have lost. These ideas have come crashing down as statal and political and architectural structures. Yet in the minds of elite Western academics, the softer non-vanguard version of these ideas are alive and well and kicking and are in control.

It’s largely true that most artistic departments—used as a term for the humanities and the social sciences—across the board are in the hands of the West’s most ferocious ideological opponents inside the West, mentally. Not necessarily in terms of how people live their lives and so on, but in terms of what they accept.

The worst ideas in the world are some of the ideas in this room from the perspective of these sorts of people! And they know what they are against, although most of them are in a sense more coherently in favor of what they’re for. Most Left-wingers and liberals, like Tony Blair, begin with the first thing Blair ever did, which was to go on an anti-National Front march. The first moment was negative. He knew what he was against almost before what he knew what he was for. But many of these people actually know what they’re for as well, and what they’re for is a world without any prior signification.

Deconstruction is the idea that you have a text before you, and this text has a system of rhetoric which is related to the personality of an individual author, but the author doesn’t exist. It’s just a text. It’s just a signification. What you do is split the power of the rhetoric, the oratory, the nature of the language used, the control of the phrases used, the essentialist markers that delimit the promiscuity of linguistic and moral choice, and you deconstruct them. You open up the field of signification so that language can flow freely in its joy and in its meaningless splendor. This is called jouissance, the joy of deconstructing the text so that it reveals its anti-essentialist possibilities when the crypto-fascistic moments of identity in it have been removed, and this is what they do.

They will take an author like Céline, who is a French National Socialist essentially, if words have any meaning, and they will say, “This anti-Semitic statement shows the insecurity of a lower middle class background. He obviously wets his bed. He was beaten by his father.” They will deconstruct every particular notification. Actually, this is a philo-Semitic text, which loves foreigners, which loves homosexuals, and is egalitarian! The whole point of deconstruction is that you reverse the meaning of the text.

But these ideas have their dangers, because there are certain things that liberals believe are sacred, and there are certain things that they believe shouldn’t be deconstructed and are beyond deconstruction. One of the primary deconstructive figures, who wasn’t necessarily a Leftist, was a man called Paul de Man, who was head of English and Philosophy, head of the Yale school of deconstruction at this Ivy League college. Ivy League college, Yale, has a school of deconstruction![3] Yes, it does! Acting against the West in order to affirm the negation of its identity. This is the sort of thing it said.

Now, Paul de Man was head of philosophy there, but Paul de Man had a secret past far worse than beating his wife or something like that. Paul de Man was a collaborator in occupied Belgium and was a minor member of the Rexist movement with Léon Degrelle. It was all very serious. And he also wrote some articles for a magazine like Scorpion shall we say, but it was in occupied Belgium at the time, so it was a bit more serious.

When it was discovered that he had this past, the whole of the movement of deconstruction gathered at the University of Alabama in the Deep South of the United States to discuss this unfortunate recrudescence of essentialism in the life and time of their chief American guru. Derrida came up with a remarkable wheeze. He said that because there were articles on the one side of the page of these collaborationist journals that were more extreme than what de Man had written, de Man was actually protesting against the extremism of the rival and mirror-reflected text with his own understated fascism, therefore revealing that he was in internal critical protest at the nature of this foul language and this sort of thing. Foul language in another way.

Interestingly, deconstructionism and post-structuralism have never survived this particular revelation, and it’s not fallen off a cliff, but it’s much less fashionable now than it was. It’s also begun to be attacked by certain hard Leftists who are more materialistic, more pro-science and so on and don’t agree with this type of what they consider to be empty and rather vacuous theorizing. So, there’s been a certain revisionism.

Not all of these ideas have it their own way. There often outliers who are dissentient. They’re often critics within the system as well as without who are progressive. You can only criticize progress if you are yourself a progressive. This is part of the deal. So, there are progressive critiques of this sort of thing. Lévi-Strauss loathed elements of modern culture, loathed modernist art and so on. There’s a degree to which certain impermissible reactions or “fleets to the essence,” as it is sometimes called, are permitted by very radical theorists.

There’s also certain of the revisionists like Serge Thion, for example, who played with post-structuralist ideas, which makes them very dangerous. As soon as I heard about post-structuralism in the 1980s, I knew that certain revisionist types would make use of some of these methodological tricks, because it’s inevitable. You can apply deconstruction to deconstruction. You can get Céline’s text, you can get the deconstructive answer to the text, and then you can deconstruct the deconstructive answer to the text and you end with Céline again!

So, you think, “What’s the point of doing all that?” And the point of doing all that was to question the affirmations of Western society. That’s what the point of all that is. The people who flood into the humanist disciplines in sociology, in fine art and elsewhere, if you say, “Well, you know, Caravaggio is a homosexual,” people will say, “Oh, dangerous assumptions there. A bit too essentialist. Are you reading the author or the artist who wrote the text too much into his own work?” And so on. It creates a fog of uncertainty. It creates an irony of the absence of affirmation, the absence of pride, certainly the absence of the justification of hierarchy, which it’s all about.

Ken Livingstone is a populist libertarian Left-wing politician. When he was asked about political correctness and banning Black children in south London from saying nursery rhymes like “Ba-Ba-Black Sheep” and so on, he said, “That’s Evening Standard garbage.” He said, “Political correctness is an attempt to change people’s minds and language. It is concentrated on two egalitarian premises: absolute moral equality in questions of race and gender.” He’s a real Leftist.

That’s what it’s really about! It’s not about any of these epiphenomena. It’s about making elitist and inegalitarian assumptions morally and linguistically impermissible. And if they’re impermissible for a university professor, they’ll be impermissible for a struggling fourth level post-degree student, and they’ll be impermissible for a middle-class bloke who sort of half-believes what’s in the Daily Mail, and they’ll be impermissible for right the way down the society. And they will, in a garbled way, come out of every news channel you can speak of.

Many liberals now say, “We’re fighting for Western values in Iraq. But what are Western values? Do we have a right to fight for them? In any case, should we affirm ourselves? We’re attacking the essentialism of their own. We should deconstruct at home first before we go abroad imposing our signifiers upon these worthy foreigners.” And so on. You see, it begins small. It begins with a debate about language, but it becomes much more powerful. In the intellectual ideologies that operate outside the sciences now, these ideas are de rigueur. To be actually against them is to morally shock, far more than transgressive post-modern art in relation to the Turner Prize and that sort of thing.

Things like the Turner Prize bring me to Stewart Home. Now, the Turner Prize is attacked by Home, but from the Left. You can only criticize Left from Left. He’s to the Left of the Turner Prize. The sort of art that is exhibited in the Turner Prize, which is a sort of stitch-up by various dealers particularly in the 1990s in relation to a particular school of post-modern artists that came out of Goldsmith’s College of Art in the late ’80s, early ’90s. Damien Hirst and Tracey Emin and Gavin Turk were the most prominent of the three. They were picked up with a lot of big money and people wanted to make their own money as a result of it. However, it’s based on an ideology called anti-objectivist art which comes from the 1960s and was largely part of the hippie movement.

John Lennon was involved extensively in anti-objectivist art. Do you remember getting into a bag for peace? This is where a naked John Lennon, covered with hair, would get into a bag. A bag! Yoko Ono, who was a member of a group called Fluxus, would draw the zip on the bag, and Lennon would stay there for a day, because the idea was that if we were all naked and in bags and covered with hair, we wouldn’t fight, and there would be no more war! There would be a realm of peace on this earth for us all to enjoy!

Another Fluxus fad that Yoko was very keen on was the revelation of the buttocks. They would sit there naked before NBC and CBS and ABC and the BBC and all the big channels of that era revealing their naked buttocks. Because of course you won’t fight if you’ve revealed yourself in that way, and the point was to avoid struggle by not fighting.

These ideas had little currency and didn’t last too long, but anti-objectivist art begins there, and from it Stewart Home begins his particular intellectual career at this time.

Home’s is an anarchist, essentially, or a libertarian communist or an anarcho-communist. He’s written many books, but his one real claim to fame is a book called The Assault on Culture—the assault on culture!—From Lettrism to Class War. And he deals with an assembly of extreme Left avant-garde groups that come out of the major modernist tendencies as they end.

Modernism is a very complicated area that goes back to the middle of the 19th century. It’s a reaction, in part, against photography. It’s a desire to go inside the mind and fantasize. It was despised for much of the late 19th century, early part of the 20th century, then became the major aesthetic discourse of liberal humanism. There’s a complication there, because both fascism and communism flirted with modernism. Most of them then turned against it, although the Portuguese, Spanish, and Italian far Right regimes made use of moderate modernist tendencies.

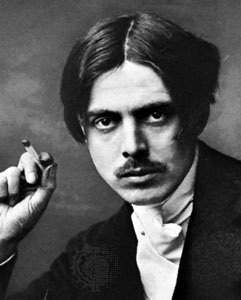

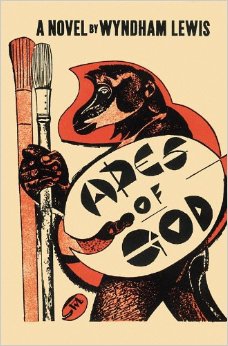

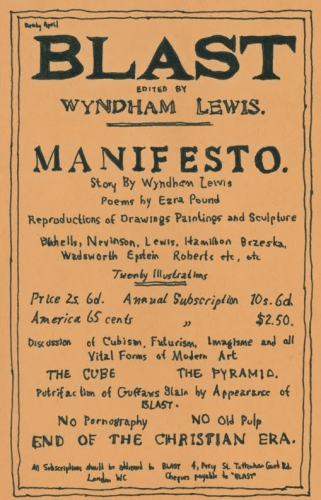

Modernism has always had a devilish side from the perspective of Left humanism, because a lot of the early modernists were fascists, were anti-humanists, and were radical Rightists like Ezra Pound, like Wyndham Lewis, like Marinetti, like Gaudier-Brzeska, like Céline and so on. That’s because there was an anti-democratic element to it, because of course modernism was a bohemian attack upon the sensibility of the majority. It loathes what ordinary people think about art, so it will destroy what they want and impose what intellectuals want. It’s a sort of vanguard hostility to the boring majority. Bomb the suburbs! That’s the sort of view of modernism.

But that can tend to the Right as well as the Left in strange moments, because national cultures were still alive to the degree that there could be national modernisms. Expressionism was a largely Germanic form; futurism was an Italian form; surrealism was a French form. Surrealism was the only major modernist movement that linked formally with communism, through the radically state socialist ideas of its founder, André Breton. Basically, surrealism died with him, but as it died all sorts of shards came out of it, one of which was called situationism.

Situationism was a minor ideological current that’s achieved quite a bit of currency, particularly on the far Left, because a lot of the students in 1968 mouthed situationist slogans. The media was convulsed to find that, on one hand, there were these hippies throwing bricks at members of the CRS—the very tough central riot police in Paris and the other big cities—but they would paint these slogans on walls saying, “Seize the imagination” or “Release the factories” or “I want to play with myself” or something like that. Strong-hearted philosophical stuff like this. They would spray things on the walls. And most of these were situationist slogans taken from a book called Society of the Spectacle written by Guy Debord in the late 1960s. Debord later committed suicide in dubious circumstances. There was another intellectual associated with this tendency called Raoul Vaneigem who wrote The Book of Pleasures and The Revolution of Everyday Life.

Now, these books had a lot of impact in revolutionary artistic scenes. It’s very interesting to notice this combination of far Left art, anti-social practice, misanthropy, and extreme amounts of money, and their ability to attract each other in disassociated ways. Anti-objectivist art began as hostility to the art market. It began by producing artworks that no one would want to buy! That’s the whole point. You were rebelling against the market! They used to have marches on Sotheby’s saying, “Death to Sotheby’s! Death to Sotheby’s!” Now they’re all sold in Sotheby’s for enormous amounts of money!

The most classic example of this was an Italian conceptual artist in the 1970s called Piero Manzoni, and Manzoni used to sell blocks of his own ordure. He used to sell blocks of his own ordure in gold-tinted, beautifully framed sort of 18th-century gold-leafed tins. An Italian-American heiresses used to buy this for $7,000 a tin to say at their kinky and trendy parties that, “I bought one.”

Because artists always loathed the dealers. They always loathe the middlemen, a third of whom have always been of a certain ethnicity. Always. A third of art dealers are Jews, and a third of art dealers are homosexuals, and not always an overlapping category. But artists loathed the middlemen, and there’s a desire to revenge yourself on the middlemen by producing work that can’t be sold, that’s impossibilist, if you like.

But the market can sell anything. You can sell debt as an asset from which you can make more money. So, why not sell cars that are bolted together? There’s a famous case of one artist who was neo-conceptual and was an action artist who tried to sell his dead body after he’d committed suicide. There’s also a man called Rudolf Schwarzkogler, who’s Austrian, and he wound himself in mummification, and either did commit suicide or feigned to commit suicide. I hope not to ruin anyone’s appetite by some of this, but it’s all true. It’s all true, I assure you of this! There were several other ones who left bits of their bodies, including arms and legs, in various galleries and so on, and this was photographed in the 1970s. This was action art, wasn’t it? I mean, let’s face it! There’s something that’s going on here! Home’s book The Assault on Culture has Schwarzkogler’s pre-corpse mummified body on its front, so you know what you’re getting.

Now, the movements with which Home deals are situationism, which is a Left-wing critique, in other words a critique from the Left, within the Left; there’s lettrism, which is another idea which relates to certain formalist and linguistic ideas; and there’s the movement for the imagist Bauhaus, which is a splinter from Breton’s surrealism. They’re also slightly dangerous movements, because Home has an equivocal element, not in what he wants but in what will happen.

One of the dangers about the Cult of the New and the Cult of the Future is that there can be different futures that Left-wing people don’t like. There was a group in the 1970s called mail art, and this woman would do these traditional biographical pictures, very traditional academic art, the sort of thing [unintellible—sounds like Auckland] would have done at the turn of the 20th century and just in and around the Great War, and she would send them to people. She would send them to the Prime Minister. She would send them to the Pope. She would send them to the Chief Rabbi. And they were all pictures of Adolf Hitler. They opened them and were appalled. It was quite a scandal, and she said, “But I’m not a Nazi. I’m just being transgressive. I’m doing what is non-bourgeois. Hitler may have done evil things, but I’m not evil. I’m just painting a picture. It’s just a representation.”

So, you see, if you adopt the Cult of the New . . . And Home had this idea called neoism where he wants to create culture anew, which is largely based on Marinetti’s ideas that you can bomb everything and begin again, because we are the masters of the ruins. It’s the rhetoric of people who’ve never been to a real war, you see, and those who were just about to, because a lot of this stuff came out in 1912 and was just the quivering in the antennae of the Armageddon that was about to erupt. Although, to be frank, many of the Marinettists, the futurists, actually did fight in the war, because they believed in war. They glorified war. “We glorify men! We glorify war!” This is why they linked with Mussolini later, or some of them did.

Now, Home’s work is based upon the idea that you can go beyond the Left and push even that which is Left-wing further Left. He’s in this odd position, because the Left never thinks it has won. Even when it’s triumphant, even when many dons agreed with some of their assumptions, they think, “It’s not gone far enough. The revolution has been betrayed! You need to go further! More radicalism, more self-criticism, more anti-essentialism! It’s not enough! Turds in a box: not enough! Deconstructing classic opera: not enough!”

Turandot and other operas now, even in the West End, often have a urinal on the stage. Urinal? What’s that about? That’s Duchamp’s idea of the ready-made, you see. This plate is art! Who are you to say it’s not? I look at this work. I mediate it. I objectivize it as my view of life. The stained dregs of life in this coffee cup. Life ending in doom. Didn’t Beckett say they were born over a grave, there’s a cry, and then it’s all over? You see, art! I want 2,000 for this now, and you’ll give it to me! And that’s how that sort of thing starts.

I heard a bloke once at the English National Opera, and a critic said, slightly bemused, “Why do you put a toilet on the stage?” And he said, “We’re acting against the piece. We put the thing on, but we try to destroy it as we put it on. It’s deconstruction.”

And you know why these ideas have got a hold? Because they’re bored. Because they’re bored with Western culture. Since the Second World War, state funding of the arts has replaced bourgeois capitalist money. It’s replaced aristocratic patronage. And you can only do Shakespeare so many times. There’s a great tiredness to these state institutions, and this tiredness often breeds a kind of nihilism. “Why, let’s tear it all down, this fuddy-duddy stuff that we endlessly have to replicate with the tax-payers’ money!” These ideas course through even revived and classical theater.

Racing Shakespeare is the favorite one. At the beginning of the 20th century, Othello was always played by a white man blacked up: Olivier very famously in the ’50s and thereafter. Middle of the century, always played by a black actor, because you had to bring to the foreground the nature of race and the nature of oppression and the nature of Shakespeare’s unfortunate alienating and objectifying tendencies: odious. Now, usually, Othello is played by a white actor, because not to black up is to draw attention to the hideous racism of the piece so that guilt should be infused in the audience for the crime of Western civilization. Nine million dead. Farrakhan said in the United States, “Never mind the six, what about the nine!? The nine million who died in the Atlantic slave trade! What about us?”

There was a famous Richard Eyre version of The Merchant of Venice in the 1990s where the female lead apologizes for the Shoah on stage. She’s kneeling before the audience. Don’t remember that in the text, actually! Don’t remember that in the original play! This is ironic considering that some of these ideas have come out of this idea of extreme textual specificity. “But you can always change the text when you want! It’s only a text!” And this sort of thing.

There’s is a sort of comedic element to these ideas, but I assure you that it would be instructive for everyone here to go to the Institute of Contemporary Arts. The ICA’s in Pall Mall, near the Queen. Right in the center of all the establishment buildings, and it’s all very nice in there with mellow lighting and all this. You go in, and there’s a bookshop in there, and that is very interesting, because that bookshop is like a cathedral bookshop to this type of culture. Home’s books are all prominently displayed in that particular bookshop. All of these deconstructive, anti-identity, post-racial, non-class, non-gender specific, gender-neutral-language particularisms are all there. Volume after volume after volume.

Actually, Home did a book once that had sandpaper on the cover so it would cut up all the books next to it, you see? Revenge! Revenge on the books! And you’d also damage yourself when you touch it, you see? So, he’s attacking the reader! William S. Burroughs was once asked, “What do you want to do with the reader?” And he said, “Kill him. I want somebody to open the page and be so appalled that they virtually drop into it, you know?”

There was a famous moment with Nineteen Eighty-Four, the BBC one with Peter Cushing in the 1950s. There was a Mrs. Treddis of North Wales[4] who allegedly did drop dead during the rat scene, Room 101. She was watching this on a state subsidized channel on the BBC, and when O’Brien gets the rats out in the Chinese torture scene—“Do it to Julia!”—she just caved over, poor old Mrs. Treddis. The MP was straight on the thing. He was in the Commons saying, “It’s disgraceful that the state broadcaster is killing its own constituents with art!” You couldn’t make it up, could you really? There is a degree to which the desire to attack the audience is very much part of this art.

There’s actually a form of art called auto-destructive art by Gustav Metzger where the art actually blows up, or a tube of acid will turn over one of those sort of mechano-wheels—you know, one of those sort of amateur things—and the tin turns up and pours acid down the front. So, the art attacks you, you attack the art, the art attacks itself. And then you buy what’s left, even though it’s been completely destroyed.

These ideas actually entered into popular culture because a lot of rock bands and so on were made up of students who go to art colleges. The Who used to destroy their instruments on stage. Pete Townshend, when he wasn’t looking at dubious sites on the internet, was wrecking his guitar. And these guitars are expensive things. Keep it plugged in. And he’d smash it on the ground, and sparks would be going up. I think it’s totally counter to health and safety, personally. And he’d smash it, and it would blow up! It would blow across the room, and all the crowd would be chanting. This was based on auto-destructive art. But, of course, they were working class lads, and there were dangerous moments of essentialism in The Who because they always had the Union Flag behind them when they’d perform. Ah, the danger of those estates. More deconstruction, that’s what’s required.

Home criticized the situationists because it was always a Hegelian theory and therefore allowed certain religious notions in from the outside. There was a communist called Jean Barrot who wrote a critique of situationism. He was later a supporter of Pol Pot, but he’s not heard of too much these days. Certainly would have been heard of if he had been Cambodian.

Now, Home got into trouble a couple of years ago, and Larry O’Hara, who’s a sort of libertarian anti-Right wing critic who’s prepared to be at least reasonably factual up to a point, wrote an article called “Stewart Home: The Fascists’ Flunkey.” Because if you advocate for new areas of culture, total newness, you will attract people who don’t necessarily believe in equitable variables. And he attracted certain people, certainly Richard Lawson, who’s well known from the National Party and Scorpion and Perspectives and had his website called Fluxeuropa and was a Left European nationalist, I think it’s fair to say. He also struck up a bit of a relationship with Bill Hopkins, an old friend of mine, and there’s a film, six minutes of Stewart Home interviewing Bill Hopkins. It’s on YouTube [6].

Now, he’s been heavily vilified for this, because by an ideological detour into the concept of the new, he forgot progressive verities. He’s recovered. But it’s bad news to reach out to radicals before you know who they are. You can get into deep trouble doing that, and he has. Because people say, “Didn’t he have some friends who were . . .” That’s what’s remembered in this [unintelligible—sounds like “tap it in”] and Google your name sort of an age.

Home believes that everyone can create a culture just as there were certain classical music concerts in the 1970s where the orchestra would make it up as they went along. Xenakis was another one. You wouldn’t have a piece. You would deconstruct the music. Indeed, they would tear the music up before the performance and stamp on it! Stamp on it in a rage at the bourgeois class! Then they would sort of make some music. Home believes that everybody can do that. He calls it the universal proletarianization of culture: the universal proletarianization of culture. And he idolizes these slightly Rightist elements. He idolizes these skinhead novels in the 1970s. Does anyone remember these novels by Richard Allen called Skinhead and Suedehead and [unintelligible—sounds like truth my bitch]. and all these sorts of novels that used to be read under the table in schools, seized in reformatory schools because, you know, no reading in this [unintelligible]. They were written by this old drunk on the south coast called Richard Allen, and Home loves all this.

He’s written several books. Red London is one. He’s also written books that are just swear words, the C-word is the title, oh yes. And the S-word and the F-word. These are all in Smith’s. They’re all in Waterstones. He’s done it because he thinks, “Why not? And also I’ll push distribution to such a degree that are they going to go on Radio 4 and say ‘Well, we have books with all sorts of swear words in them, but we won’t allow them on the cover. The Royal Chamberlian lives in memory. We will not allow it on the cover.’” And Home is saying, “Why not? Why not? Are you some bourgeois slob, mate? I’m pushing this in front of you.”

He’s also a very extreme homosexual. You would have to have this. So, his works are these sort of cartographic fantasy of proletarianized homosexual blokes rampaging around London. This is on sale at any Waterstones, books called C— and S— and F—. I’ve looked at the covers, and I’ve read the theories. But the theory’s important in a way, because at the end of The Assault on Culture he endorses Class War.

Now, Class War is a group that emerged in the early 1980s and is led by an anarchist called Ian Bone. And they do believe in Bakunin’s idea of total war on the state. When Bakunin was asked “What is anarchy?” he said, “Total revolution against God.” And that is what anarchism believes: total revolt against all ideas of transcendence, total revolt against all ideas of hierarchy. “Pull it down! Destroy it!”

There’s a famous story about Bakunin in E. H. Carr’s—a Soviet-philic writer—biography. Bakunin’s riding along, because he’s an aristocrat of course. He wanted to destroy everything, even the aristocrats first. And he sees some brigands robbing a house, and they’re smashing it to pieces with axes and so on. He says, “Stop!” in Russian, gets out, and joins the brigands, and he starts destroying and running out with the paintings and butting them and leaping up and down on them and hurling bricks through the windows and all this. When somebody said, “Mikhail Mikhalovich, why are you doing this?” He said, “Because it’s there.” Because it’s there.

And Home’s view is that destruction is a creative passion. First you destroy, then you create on the destruction. Even if you create and destroy, because you level the field for new forms: neoism! The cartography of inversion! And if you don’t like it, you can get a bit of this! It’s this sort of stuff. The interesting thing is that these ideas are not revered. They’re eccentric ideas even within the milieu of the cultural Left. But they’re there.

Scorpion’s not sold in the ICA bookshop. Alain de Benoist is not sold in the ICA bookshop. Books about Heidegger are sold in the ICA bookshop. Heidegger, Monster of Nazism: A Philosophy of Inhumanity Exposed! Heidegger and the Jewish Question. Unanswered questions, who was his mistress? We demand the facts! Heidegger! 400 pages of his Party membership between 1933 and 1934. Husserl: Did he Ban him from the Library? The Truth! Heidegger: Deconstructed. Pluto Press in three editions. That’s in the ICA library! But the authors of that which constitutes European identity are for the most part conspicuously absent from the ICA library.

Class War has, of course, died many years ago, and Bone is largely retired from active politics. He appeared on Jonathan Ross once, who I call Jonathan Dross, and he appeared wearing a wig screaming and ranting. Bone’s just treated as a freak show, you know. Just something to laugh at, really.

However, from our point of view, not altogether laughable because a group called Antifa emerged from Class War. Antifa would very much like to beat us all to death, I mean, they really would. But they’re very small and of little significance. The interesting thing is that he was drawn to Class War because they’re situational, because it’s not going to succeed, is it? But you create a happening space, you create action art in society. Do you remember the march on the rich? “Bash the rich!” Remember the marches in Henley? “Bash the rich! Bash the rich!” You know, this sort of thing. Bored policemen, drongos and hippies and white Rastafarians, people with purple mohicans and this sort of thing walking along surrounded by the special patrol group, screaming execration at the bourgeois class and that sort of thing. It was all good fun. Then they’d go back on the train up to [unintelligible] or [unintelligible] or wherever it was. Bone was there. The hard men were there.

There was a famous moment of anarchism in Chicago where all these very old bourgeois people are eating in an extremely rich restaurant, and the anarchists unfurl a banner in front of them saying, “Behold your future executioners!” And they love this sort of sport as play as action as theory. Anarchism, unlike communism—because of course anarchism is to the Left of communism—has a theory called direct action: direct action on the anger of the class, which of course is terrorism really. They don’t call it that, but that’s essentially what it is. These sorts of stunts, even that Class War stunt, “make the middle class afraid,” tossing and turning in their beds and only wondering if those mohican yobs are coming for them.

Those demos are very interesting. I once went on one of those demos and watched, and the hardcore anarchs, the hardcore activists, stand at the back and they throw forward the hippies and the drongos and the others. And they’re the ones who are beaten by the special patrol group or whatever the riot squad is called now. They’re on the ground, and they’re covered in blood, and the policemen step on them and kick them. This was the ’80s. I mean, I saw it with my own eyes. It wasn’t a travesty of British behavior. I saw it. But the hardcore activists with leather jackets are at the back, and when one goes down there’s another there, you know, because the masses are just fuel—fuel for anarchy.

The point of these doctrines is that you open a space in the society where you can create new forms, because when you open a space anything can happen. If you assassinate a politician, anything can happen. That’s why they used to assassinate them all the time in the 19th century.

These sorts of ideas of rage and deconstruction and alienation—particularly impinging on all forms of identity—have probably reached their high water mark. But the very fact that they can be canvassed, the very fact that they are in the ICA, they’re in the NO, they’re in the theoretical book branch of the National Theatre—all state-subsidized. There’s tens and tens of millions of pounds that are spent on these institutions every year through the art boards and so on. The fact that these ideas are in the Western academy is a testament to the fact that communistic doctrines of radical destruction and deconstruction have taken over the mindset in the society. People who speak against them are, well, they’re nowhere to be seen basically, because they’re terrified. They’re partly waiting for the next fad, really, in the hope that some of this stuff will wash away.

But the interesting thing is that they always know what they’re against. Home is certainly aware of the New Right. He used to edit a magazine called Smile—smile!—which was a nihilist, communist magazine. That’s what it said on the front. You can go to Smith’s, you know, “Would you like to buy a nihilist, communist magazine? Smile.” It would have an article about Lenin and an article about the Bombo Gang, and then you would have diseased genitals, because it would shock the bourgeois audience and scratch the hatred of the masses. And in that transgression you open up a moral space for more radicalism of the mind and of the spirit. It is psychologically subversive, and they know what they’re doing! They know what they’re doing. The shocked person goes, “Disgusting trash!” and throws it away. They’ve actually had an effect, the effect of rejection before the next strike.

My view has always been that that sort of militancy has to be stood up to. And you have to fight back. And you have to fight back as hard and as ruthlessly as they do. That’s why they are aware of us and fear us.

Stewart Home also has an interesting view of race, which is an original formulation. I’ve never heard it even from the Trotskyists, and he’s not a Trotskyist. He believes that race doesn’t exist, but the masses believe it does. Now, that’s an interesting formulation, because if you think about it you either have it as a foregrounded form of iterization, it’s being, Dasein, being in being as Heidegger would call it. It’s that which is there. It’s biological. It’s there. It’s foundational. It’s prior. It’s elemental. It’s essential.

Or you don’t believe that. Maoists and extreme communists believe that all humans are a white sheet of paper. Any sexuality, any ethnic specification, any culturalization, any level of intellect could be pre-programmed into you. As Mao’s people would say, you can torture a man into progressive ideas to the degree that they’re coming out of his ears.

Do you remember what O’Brien says to Winston Smith in Nineteen Eighty-Four? “First, we make you love Big Brother, then we kill you. Don’t you remember, Winston,” he says, “you’re just a cell in the body of the Party? Do you die if you cut your fingernail?” Do you remember that, and the great actors like Sir Richard Burton who played that part?

Now, Home’s idea is interesting in a way, because they believe in false consciousness. He’s basically saying race is the false consciousness of the masses, but if nothing is prior, then reality is in the consciousness of the masses. Therefore, if the masses think that race exists, it does exist, even in far Left terms, because only that which is thought moment by moment in the struggle exists! So, in a strange sort of way, he’s ended up with a Right-wing deviation within Marxist cultural logic. He’s actually got back to a position he says he refutes.

But it’s an interesting one, because if you notice, the dip in biological thinking in the middle of the 20th century as a reaction to the Second World War, is the high point for these type of new Left ideas. Now that biology has been re-emerging in the last 30 years. And it’s very interesting, for example, that the Anti-Defamation League in the United States opposed the creation of the Human Genome Project. And many gay libertarian groups opposed the Human Genome Project. They are radically opposed to the idea of the biological investigation of the building blocks of life, because it will lead to the possibility of acceptance by the masses of a prior essentialism.

There was an interesting incident last year when the Genome Project’s scientific review board wrote to the German Academy of Sciences and said that “In our opinion, life is 80% natural law and prior biological purpose.” Not 60%, not 70%, but 80%. Man is socialized by 20%, and I view the socialization as environment, and environment is ecology, and ecology is a species of biology. So, in a way, it’s all biological.

And the German Academy wrote back, “We cannot accept this thinking. We cannot accept this thinking, because we understand that your postulate is from good intentions, but it draws us perilously close to rejecting the methodology of the basic law upon which contemporary German governance, state, society, and academic learning is based.” So, the German government says that a particular scientific outcome is wrong, and as a citizen of the contemporary united German republic, founded under occupation by Adenauer in 1948, you have to repute it. We don’t care what science says! We repudiate science! This is a revolutionary development really, whereby the Left, the organ of progress, is rejecting science.

There’s a concept on the New Left of scientism. Scientism. Science is ugly, male, reactionary, authoritarian, phallocratic. All this sort of stuff. There’s a strong streak of feminism in all of these discourses. The Left has sort of given up on that. Many Leftists are now debating about how they deal with biology. Peter Singer, who wrote the book Animal Liberation, which founded that whole movement: “Liberate the animals, you filthy speciesists,” “Put down that ham sandwich,” that sort of thing. Singer, of course from a certain ethnicity, from Australia where he was in the Australian senate. He was a civil libertarian and radical green. He’s a utilitarian. He’s a very interesting thinker. Because he’s introducing a new hard liberalism.

Singer says maybe biological ordinance is true; maybe disability is inherited; maybe gender is inherited; maybe sexuality is due to brain function; maybe the Right is correct. But what you must do is pass every law and every methodology that lies behind the law, jurisprudence, to make sure that there is either equality of opportunity or equality of outcome or those who proselytize for inequality of outcome are not allowed to affect it by the nature of their discourse. So, what he’s saying is even if biology is unequal, you make the society so impervious to that logic, even though you’ve got a hierarchy, that it’s not aware of that.

That’s the most important and intelligent form of far Leftism. They can only sustain anti-science. They built their entire creed on science. They can’t repudiate it. That’s just a stunt for a couple of decades. They’re going to have to accept the Human Genome Project. They’re going to have to accept the biological and prior ordination of man.

Every time I go into an NHS clinic there’s a leaflet for transplants, and in the middle of that leaflet you’re asked about your race. It says, “Are you White Caucasian? Are you Asian? Are you Negroid or Diaspora African?” All these little boxes. And that’s because human internal tissues will not transplant or graft as well in relation to one race as another. Prior racial difference within the taxonomies of the human even at the physical level.

If a scientist at Oxford or Cambridge or the London School of Economics had said that openly in the 1960s or 1970s, there would have been rioting! There would be rioting in the canteen. There’d be rioting in the lecture hall. The special control group would have been on the campus. You would have been hounded out of that place of learning. It’s now in an NHS leaflet. Quietly, no fuss. It’s just intruded there as a fact. “Who can reject it? We’re helping people! We’re helping people!”

And talking about helping people, there are ultra-liberal groups in the United States who are campaigning against certain forms of medicine that affect individual ethnicities. There are certain diseases that Blacks and Africans suffer from, particularly sickle cell anemia, which is almost congruent to them, and certain drugs that have genetic potential and originate from some of the theory and experimentation of the Human Genome Project react primarily on their group. There are ultra-liberal groups who are campaigning to not allow the Food and Drug Agency to license these.

Why? Why? Because it undermines the idea that man is a white sheet of paper that you can do with what you want and there is no prior identity. They would rather blacks suffer than that these drugs were produced, because they admit the prior biological differentiation of the human. And when you begin there, when you begin with such a monstrous prior essentialism, the doors to you-know-what are swinging open. So, you must close down the thing before you even begin to agree with what you disagree with.

Thank you very much!

Notes

[1] Bowden misspoke here: Ferdinand de Saussure was the founder of Structuralism, not one of its later developers as he seems to imply here.—Ed.

[2] Heidegger’s Collected Edition (Gesamtausgabe) runs to nearly 100 volumes, most of which were published posthumously.—Ed.

[3] The Yale School of Deconstruction signifies an intellectual movement, not an academic department or college. De Man joined the faculty in French and Comparative Literature at Yale. At the time of his death in 1983, he was Sterling Professor of the Humanities and chairman of the Department of Comparative Literature at Yale.—Ed.

[4] Apparently, the woman was actually named Beryl Merfin of Herne Bay, Kent.—Ed.

Thomas Edward Lawrence était farouchement hostile à la parution de son vivant des mémoires et comptes-rendus de ses aventures et opérations militaires conduites en Arabie entre 1916 et 1918. Il fit imprimer, en 1922, une édition privée qui circula dans un cercle très restreint. Lawrence estimait que certains passages des Sept Piliers étaient trop personnels, voire compromettants. Il ne souhaitait pas non plus embarrasser ses supérieurs hiérarchiques de la Royal Air Force : l’ancien colonel, héros de guerre de notoriété internationale, était alors devenu à sa demande un simple subalterne engagé sous un pseudonyme.

Thomas Edward Lawrence était farouchement hostile à la parution de son vivant des mémoires et comptes-rendus de ses aventures et opérations militaires conduites en Arabie entre 1916 et 1918. Il fit imprimer, en 1922, une édition privée qui circula dans un cercle très restreint. Lawrence estimait que certains passages des Sept Piliers étaient trop personnels, voire compromettants. Il ne souhaitait pas non plus embarrasser ses supérieurs hiérarchiques de la Royal Air Force : l’ancien colonel, héros de guerre de notoriété internationale, était alors devenu à sa demande un simple subalterne engagé sous un pseudonyme.

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

Il plastronne d’ailleurs d’autant moins qu’il a promis, d’ici 2017, un référendum sur la sortie de l’Angleterre du magma européen. Tiendra-t-il ses promesses ? On murmure que certains politiciens persisteraient à honorer cette obscène habitude… Mais là, il lui faudra compter avec les voix de Nigel Farage. Et celles des nationalistes écossais. Et, surtout, avec les menaces de la City qui menace de se délocaliser – tel Renault délocalisant une vulgaire usine Logan en Roumanie- ses activités dans ce no man’s land allant du Liechtenstein aux Îles Caïman tout en passant par Singapour.

Il plastronne d’ailleurs d’autant moins qu’il a promis, d’ici 2017, un référendum sur la sortie de l’Angleterre du magma européen. Tiendra-t-il ses promesses ? On murmure que certains politiciens persisteraient à honorer cette obscène habitude… Mais là, il lui faudra compter avec les voix de Nigel Farage. Et celles des nationalistes écossais. Et, surtout, avec les menaces de la City qui menace de se délocaliser – tel Renault délocalisant une vulgaire usine Logan en Roumanie- ses activités dans ce no man’s land allant du Liechtenstein aux Îles Caïman tout en passant par Singapour.

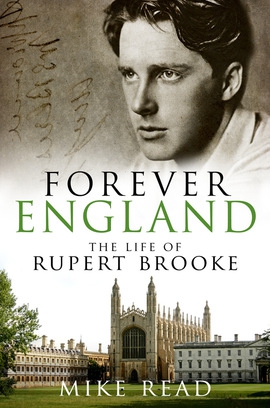

Il y a cent ans mourait en Méditerranée sur le chemin des Dardanelles, le 23 avril 1915, le « plus beau jeune homme de l'Angleterre » selon les propos de Yeats, l'un de ses plus grands poètes, Rupert Brooke. Tout écolier anglais a récité à l'école ou le 11 novembre, devant le monument aux morts de son village les célèbres vers du

Il y a cent ans mourait en Méditerranée sur le chemin des Dardanelles, le 23 avril 1915, le « plus beau jeune homme de l'Angleterre » selon les propos de Yeats, l'un de ses plus grands poètes, Rupert Brooke. Tout écolier anglais a récité à l'école ou le 11 novembre, devant le monument aux morts de son village les célèbres vers du  Contrairement aux écrivains de Bloomsbury qui opteront pour l'objection de conscience, Brooke entre sur recommandation de Churchill en personne dans une division de la Marine britannique et comme officier, il prendra part à l'expédition catastrophique d'Anvers d'octobre 1914 en Belgique. En Février 1915, après une courte permission en Angleterre où il écrira ses cinq sonnets de guerre qui le rendront célèbre pour l'éternité, il s'embarque pour les Dardanelles mais

Contrairement aux écrivains de Bloomsbury qui opteront pour l'objection de conscience, Brooke entre sur recommandation de Churchill en personne dans une division de la Marine britannique et comme officier, il prendra part à l'expédition catastrophique d'Anvers d'octobre 1914 en Belgique. En Février 1915, après une courte permission en Angleterre où il écrira ses cinq sonnets de guerre qui le rendront célèbre pour l'éternité, il s'embarque pour les Dardanelles mais

Percy Wyndham Lewis (1882-1957), est considéré comme le fondateur du seul mouvement culturel moderniste indigène en Grande-Bretagne. Cependant, on le met rarement sur le même plan que Ezra Pound, James Joyce, T. S. Eliot, et d’autres de sa génération [1]. Lewis était l’une de ces nombreuses figures culturelles qui rejetaient l’héritage du XIXe siècle – celui du libéralisme bourgeois et de la démocratie, qui pesait sur le XXe.

Percy Wyndham Lewis (1882-1957), est considéré comme le fondateur du seul mouvement culturel moderniste indigène en Grande-Bretagne. Cependant, on le met rarement sur le même plan que Ezra Pound, James Joyce, T. S. Eliot, et d’autres de sa génération [1]. Lewis était l’une de ces nombreuses figures culturelles qui rejetaient l’héritage du XIXe siècle – celui du libéralisme bourgeois et de la démocratie, qui pesait sur le XXe.

Un environnement artistique sain requiert l’ordre et la discipline, pas le chaos et la fluctuation continuelle. C’est le grand conflit entre le « romantique » et le « classique » dans les arts. Cette dichotomie entre « classique » et « romantique » est représentée en politique par la différence entre la philosophie du « Temps » et celle de l’« Espace », cette dernière étant illustrée par la philosophie de Spengler. A la différence de beaucoup d’autres représentants de la « Droite », Lewis était fermement opposé à l’approche historique de Spengler, critiquant son Déclin de l’Occident dans Time and Western Man. Pour Lewis, Spengler et d’autres « philosophes du Temps » reléguaient la culture dans la sphère politique. Les interprétations cycliques et organiques de l’histoire sont vues comme « fatalistes » et démoralisantes pour la survie de la race européenne. Lewis résumait la thèse de Spengler comme suit : « Vous les Blancs, êtes sur le point de vous éteindre. Tout est fini pour vous ; et je peux vous le prouver par le résultat de mes recherches, et par ma nouvelle science de l’histoire, qui est bâtie sur le grand système du temps… » [36].

Un environnement artistique sain requiert l’ordre et la discipline, pas le chaos et la fluctuation continuelle. C’est le grand conflit entre le « romantique » et le « classique » dans les arts. Cette dichotomie entre « classique » et « romantique » est représentée en politique par la différence entre la philosophie du « Temps » et celle de l’« Espace », cette dernière étant illustrée par la philosophie de Spengler. A la différence de beaucoup d’autres représentants de la « Droite », Lewis était fermement opposé à l’approche historique de Spengler, critiquant son Déclin de l’Occident dans Time and Western Man. Pour Lewis, Spengler et d’autres « philosophes du Temps » reléguaient la culture dans la sphère politique. Les interprétations cycliques et organiques de l’histoire sont vues comme « fatalistes » et démoralisantes pour la survie de la race européenne. Lewis résumait la thèse de Spengler comme suit : « Vous les Blancs, êtes sur le point de vous éteindre. Tout est fini pour vous ; et je peux vous le prouver par le résultat de mes recherches, et par ma nouvelle science de l’histoire, qui est bâtie sur le grand système du temps… » [36].

Comme nous l’avons vu, Lewis se moquait paradoxalement de la croyance de Pound au crédit social, mais il était très conscient du pouvoir de l’usure et des « Empereurs de la Dette ». Il examina cela une nouvelle fois en 1948 en écrivant :

Comme nous l’avons vu, Lewis se moquait paradoxalement de la croyance de Pound au crédit social, mais il était très conscient du pouvoir de l’usure et des « Empereurs de la Dette ». Il examina cela une nouvelle fois en 1948 en écrivant :

But this music that is Elgar’s — which is, racially speaking, a combination of Germanic and Celtic strands musically, within one particular personality — creates a feeling that English people respond to with deep sonorousness in joy and in sadness. And there is certainly joy and power and pageantry in Elgar’s music. But there’s also sadness as well. Because reading the life closely and with an eye upon the text you can really sense that there’s a bit of a sine curve in Elgar’s personality, and there are deep troughs as well as great ecstasies. There is the fact that after a major period of creation like the Second Symphony, he needed to rest up and couldn’t do very much creating for quite long time. After his wife died, I think in 1920 or thereabouts, there’s a great falling away. And apart from occasional pieces – an unfinished opera I think based on King Henry VIII – until his death, there wasn’t too much done. Elgar also realised that after the Great War there had been a high point of what critics would call jingoistic patriotism with which he had become partly associated, let’s be frank. And there was a great falling away of interest in his music during the 1920s. Although no-one, even his detractors, would actually say that he wasn’t very, very significant.

But this music that is Elgar’s — which is, racially speaking, a combination of Germanic and Celtic strands musically, within one particular personality — creates a feeling that English people respond to with deep sonorousness in joy and in sadness. And there is certainly joy and power and pageantry in Elgar’s music. But there’s also sadness as well. Because reading the life closely and with an eye upon the text you can really sense that there’s a bit of a sine curve in Elgar’s personality, and there are deep troughs as well as great ecstasies. There is the fact that after a major period of creation like the Second Symphony, he needed to rest up and couldn’t do very much creating for quite long time. After his wife died, I think in 1920 or thereabouts, there’s a great falling away. And apart from occasional pieces – an unfinished opera I think based on King Henry VIII – until his death, there wasn’t too much done. Elgar also realised that after the Great War there had been a high point of what critics would call jingoistic patriotism with which he had become partly associated, let’s be frank. And there was a great falling away of interest in his music during the 1920s. Although no-one, even his detractors, would actually say that he wasn’t very, very significant. But in this particular relief the energy is going up out of the body and there are various sort of devilish, satanic creatures reminiscent of Hieronymus Bosch and so on clawing around the bottom or the pedestal of the sculpture, trying to drag the spirit down into matter, into present day, into the somatic, into the bodily. And there are angels, or angelic figures of some description – because it’s not an explicitly Christian sculpture actually – moving the spirit upwards and outwards and towards the light. And Elgar is always concerned with, if you like, certainly in this piece, a certain lightness and a certain delicacy of touch; strength with delicacy; music in some ways relating to the spirit of dance although he never really explicitly wrote for the dance the way Bliss did with pieces like Checkmate later on, now which have been revived towards the end of the 20th century by sir Vernon Handley and his influence at Liverpool Philharmonic, for example.