Roy Campbell was born in October 1902 in the Natal District of South Africa. He enjoyed an idyllic childhood, growing up in South Africa and being imbued as much with Zulu traditions and language as with his Scottish heritage. He showed early talent as an artist but an interest in literature including poetry soon became predominant.

Roy Campbell was born in October 1902 in the Natal District of South Africa. He enjoyed an idyllic childhood, growing up in South Africa and being imbued as much with Zulu traditions and language as with his Scottish heritage. He showed early talent as an artist but an interest in literature including poetry soon became predominant.

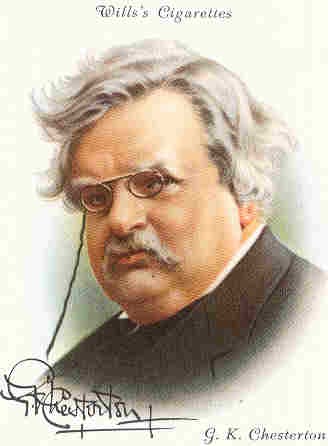

In 1918 he traveled to England to attend Oxford where by this time he was an agnostic with a love for the Elizabethan literature. Campbell’s friendship with the composer William Walton at Oxford brought him into contact with the literati including T. S. Eliot, the Sitwells and Wyndham Lewis. He was by now reading Freud, Darwin and Nietzsche, and had a distaste for Anglo-Saxonism and the ‘drabness of England’ and found an affinity with the Celts. He also identified with the Futurist movement in the arts. Campbell writes at this time in a manner suggesting the Classicism of Hulme, Lewis, Pound, and the Vorticists.

Art is not developed by a lot of long-haired fools in velvet jackets. It develops itself and pulls those fools wherever it wants them to go . . . Futurism is the reaction caused by the faintness, the morbid wistfulness of the symbolists. It is hard, cruel and glaring, but always robust and healthy.

Campbell continues by describing the new art in Nietzschean and Darwinian terms of struggle, survival and victory, but also suggesting something of his own colonial character:

It is art pulling itself together for another tremendous fight against annihilation. It is wild, distorted, and ugly, like a wrestler coming back for a last tussle against his opponent. The muscles are contorted and rugged, the eyes bulge, and the legs stagger. But there it is, and it has won the victory.

Campbell escaped from England’s ‘drabness’ to Provence where he worked on fishing boats and picked grapes. Despite his agnosticism he was impressed by the simple faith of the peasants, and started writing poems of a religious nature such as Saint Peter of the Candles—the Fisher’s Prayer, which took ten years to complete and portrays Campbell’s spiritual odyssey He returned to London in 1921, married Mary Garman, and became highly regarded among the Bloomsbury coterie who were impressed with his rough manners and hard drinking.

His wife inspired his first epic poem The Flaming Terrapin, written while the couple lived for over a year at a remote Welsh village where their first daughter was born. T. E. Lawrence was immediately impressed with the poem and took it to Jonathan Cape for publication. This established Campbell’s reputation as a poet.

Nietzsche, Christ, & the Heroic Poet

The Flaming Terrapin is a combination of Christianity and Nietzsche. In a letter to his parents Campbell sought to explain the symbolism as being founded on Christ’s statement: “Every tree that bringeth not forth good fruit is, hewn down and cast into fire,” and “Ye are the salt of the earth but if that salt shall have lost its savor it shall he scattered abroad and trodden under the feet of men.”

Campbell now realized that Christ, was the first to “proclaim the doctrine of heredity and survival of the fittest,” and that his “aristocratic outlook” was misunderstood by Nietzsche as being a religion of the weak. World War I had destroyed the best breeding stock and demoralized humanity. The Russians for example had succumbed to Bolshevism. But Campbell hoped that a portion might have become ennobled from the suffering.

He continued to explain that the deluge in The Flaming Terrapin represents the World War, and that the Noah family represents “the survival of the fittest,” triumphing over the terrors of the storm to colonize the earth. The terrapin in eastern tradition is the tortoise that represents “strength, longevity, endurance and courage” and is the symbol of the universe. It is this “flaming terrapin” that tows the Ark, and wherever he crawls upon the earth creation blossoms forth. He is “masculine energy” and where his voice roars man springs forth from the soil. His acts of creation are born from “action and flesh in one clean fusion.”

The poem published in 1924 in Britain and the USA received critical acclaim from the press as a fresh and youthful breath, as breaking free from both the banalities of the past and from the skeptical nihilism of the new generation. Campbell and his family returned to South Africa where he was welcomed as a celebrity. Here Campbell lectured on Nietzsche, and praised Nietzsche’s condemnation of the meanness of modern democracy. In this lecture Campbell also attacked the ascendancy of technology, stating that the rush to progress and enthronement of science during the previous century has outpaced mans’ mental and moral faculties and that man has becoming suddenly “lost.”

All those useful mechanical toys which man primarily invented for his own convenience have begun to tyrannize every moment of his life.

This was a theme that concerned Campbell throughout his life. In a poem written a year later entailed The Serf, Campbell proclaimed the tiller of the soil as “timeless” as he “plows down palaces and thrones and towers.” The tiller of the soil, states a hopeful Campbell, endures through eternity while the cycles of history rise and fall around him. This gives a sense of permanence in a constantly shifting world.

His poem in honor to his wife Dedication to Mary Campbell is Nietzschean in theme but also a criticism of his fellow South Africa, referring to the poet as “living by sterner laws,” as not concerned with their commerce, and as worshiping a god “superbly stronger than their own.”

Estranged from South Africans

In 1925 he became editor of Voorslag and was closely associated with William Plomer whose first novel Turbott Wolfe involves inter-racial marriage. However, despite their friendship and Campbell’s disdain for the racial situation in South Africa he reviewed Plomer’s novel and found it having “a very strong bias against the white colonists.” Nevertheless, Campbell was not impressed by what he considered as white South Africa, “reclining blissfully in a grocer’s paradise on the labor of the natives.”

Campbell resigned from editorship after the publisher’s interference. Some of Campbell’s best poems written in South Africa at this time are considered to be among his best. To a Pet Cobra returns to Nietzschean themes, describing poets in heroic terms, the Zarathustrian solitary atop the mountain peaks.

There shines upon the topmost peak of peril

There is not joy like them who fight alone

And in their solitude a tower of pride

Bloomsbury & Provence

On their return to Britain Campbell and his wife were introduced to the Bloomsbury coterie, including the poetess Vita Sackville-West her husband the novelist Harold Nicolson, Virginia and Leonard Wolfe, Richard Aldington, Aldous Huxley, Lytton Strachey, et al. The robust Campbell found their refined manners, pervasive homosexuality, and pretentiousness sickening, writing in Some Thoughts on Bloomsbury that his own voice is the only one he likes to hear when around all the “clever people.” Several years later in The Georgiad he satirizes the dinner parties of Bloomsbury where wishing to stop the ‘din’ of his ‘dizzy’; head he imagines stuffing his ears with meat and bread, and wishes the diners would choke on their food that their chattering would be halted.

In 1928 the Campbells returned to Provence. The atmosphere was altogether different from England and the wealthy socialist intelligentsia from which he sought escape. The Campbells fully involved themselves in the community, celebrated the harvest feasts, and welcomed the local folk into their home. Campbell became a celebrated figure in the dangerous sport of “water jousting.” He also assisted in the ring at bullfights. Campbell found in the customs and culture of the Provencal villagers stability and permanence in a changing world obsessed by science and “progress.” His own aesthetics, at the basis of his rejection of liberalism and socialism, was a synthesis of the romanticism of Provence and the Classicism of the Graeco-Roman. He admired Caesar and the stoicism and martial ethos of the ancients. His ideal was a combination of aesthete and athlete.

In Taurine Provence, published in 1932 Campbell writes of this:

So men in whom the heroic principle works will be driven by their very excess of vitality to flaunt their defiance in the face of death or danger, as in the modern arena.

Campbell, freed from the English intelligentsia, now renewed his attack with fury. Writing in 1928 in Scrutinies by Various Writers, he states that the dominant philosophy of the contemporary writer is dictated by “fear of discomfort, excitement or pain than by love of life.” His attack on the “sex-socialism” of Bloomsbury as being flabby and effete is contrasted with his own robust nature that could not fit in with the simpering and decadent atmosphere of the intellectual. Following on from Wyndham Lewis’ scathing attack on Bloomsbury, The Apes of God, which Campbell enjoyed immensely, Campbell wrote The Georgiad in 1931, as his own broadside. This would bring against him the mixture of condemnation and silence that the intellectual coterie had been using against Wyndham Lewis.

The Georgiad expresses Campbell’s disdain for the way Bloomsbury makes sickly everything it touches. Campbell compares his own ‘hate’ with that of their “dribbles.”

Like lukewarm bilge out of a running leak

Scented with lavender and stale cologne

Lest by its true effluvium should be known

The stagnant depth of envy that you swim in,

Who hate like gigolos and fight like women.

Bulwark of Christendom

In 1933 the Campbells left Provence for Spain due to financial hardship, despite the success of Campbell’s acclaimed volume of poems Adamastor, published in both the USA and England. This was the final work to be well-received from the Bloomsbury crowd, while his Georgiad received what The Times Literary Supplement was to recall in 1950 as a “conspiracy of silence.”

The Campbells arrived at Barcelona where a right-wing electoral victory resulted in strikes and violence by the anarchists and where machine guns were much in evidence on the streets. However, the Campbells were greatly impressed by the traditional Catholic culture.

Campbell described himself for the first time as a “Catholic” in his 1933 autobiography Broken Record, attacking both English Protestantism as “a cowardly form of atheism” and the Freudianism that pervaded the Bloomsbury progressives. He contrasted this with the “traditional human values” that continued to form the basis of Spanish culture. Broken Record was a break with modernism, but still lacked a coherent philosophy.

Despite the reference to Catholicism, Campbell had not yet converted, but spiritual questions had long occupied him, with an interest in Mithraism emerging in Provence. This cult was still to be seen in the shrines of Provence. That it was the religion most favored by the Roman legions, with its strong martial ethos, together with the mythos of the bull, appealed to Campbell.

However, he had also been strongly impressed with the faith and traditionalism of the fishermen and farmers among whom he had been so popular in Provence. His Mithraic Sonnets are a reflection of Campbell’s own spiritual odyssey beginning with Mithras and ending with the triumph of Christ, a mixture of the two religions. The Mithraic conquering sun. Sol Invictus, the byword of the Roman legions, becomes transmogrified as the Sun of the Son of God, “the shining orb” reflecting as a mirrored shield the image of Christ. It is with these vague feelings towards Christianity and Catholic culture that the Campbells moved south to the rural village of Altea in 1934.

Campbell continued to sing the song of Catholicism in martial terms, of the solar Christ as “captain” winning the battle of faith. Spain breathes its Catholic tradition and in The Fight Campbell writes again with a martial flavor, an aerial dog-fight for Campbell’s soul; his “red self” of atheism shot down by the “white self” of the Solar Christ, “the unknown pilot.” At Altea, Campbell was again impressed with the “freshness, bravery and reverence” of the people Under such an impress the whole Campbell family, actually at the initiative of his wife, converted in 1935, received by the village priest Father Gregorio.

His daughter Anna related many years later, that for Campbell, Spain was the last country left in Europe that was still a pastoral society while much of the rest had become industrialized under the impress of Protestantism. Such was Campbell’s aversion to machinery that he never learnt to drive or even used a typewriter.

At this time Campbell wrote Rust. The rust of time that brings ruin to the intentions of those who would industrialize and modernize:

So there, and there it gnaws, the Rust,

Shall grind their pylons into dust . . .

Lackeys of Capitalism

Campbell’s political outlook becomes coherent with his religious conversion. An article published in 1935 in the South African magazine The Critic shows just how clear Campbell’s knowledge of politics now was:

The artist as romantic ‘rebel’ is the tamest mule imaginable. He dates from the industrial era and has been politicized to play into the hands of the great syndicates and cartels. First by dogmatizing immorality, breaking up the “Family,” that one definitive unit that have withstood the whole effort of centuries to enslave, dehumanize and mechanize the individual, thereby cheapening and multiplying labor. It is the “Intellectual” which had been chiefly politicized into selling his fellow mates to capitalism, whether the capitalism be disguised as a vast inhuman state [as in the USSR under communism] or whether a gang of individuals. The last century has seen more class-wars, and wars between generations, than any other period. They have been deliberately fostered by capitalism, of which bolshevism is merely an anonymous form. Divide and rule, said Cicero: encourage your slaves to quarrel and your authority will be supreme. A thousand artists and reformers with the highest ideals have leaped ignorantly and romantically into these rackets, and by means of causing hate between man and woman, father and son, class and class, white and black, almost irretrievably embroiled the human individual in profitless, exhausting struggles which leave him at the mercy of the unscrupulous few.

In 1936 Campbell met British Fascist leader Sir Oswald Mosley, at the suggestion of Wyndham Lewis. Although Campbell declined to join Mosley as British Fascism’s official poet, his poetry was to appear in Mosley’s magazines both before and after the War.

Toledo, the Sacred City

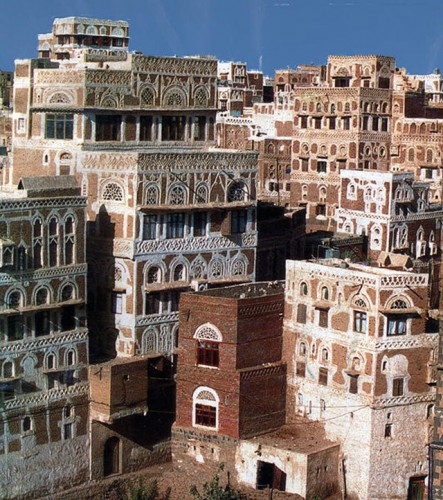

The Campbells next moved to Toldeo, which had been Spain’s capital under Charles V during the Holy Roman Empire. The city was isolated and timeless, medieval, full of churches, monasteries, convents, and shrines. The old Fortress, the Alcazar, designed to play a pivotal role in the defense of Christendom against Bolshevism, served as a military academy. The city was full of priests, nuns, monks, and soldiers, a combination of the religious, the military, and the traditional that prompted Campbell to call Toldeo the “sacred city of the mind.”

The assumption to power of the Left-wing Popular Front resulted in the release of communist and anarchist revolutionaries from gaol amidst increasing political violence in Madrid and Barcelona and street fighting between Left-wing and Right-wing factions. Churches were now being desecrated and destroyed throughout Spain. The violence reached Toledo where priests and monks were attacked and a church set ablaze.

The Campbells sheltered several Carmelite monks in their home. Campbell, well known for his anti-Bolshevik views and for his faith, was severely beaten by Government “red” guards and paraded through the streets to police headquarters. His gypsy friend, with whom he was riding at the time of his capture, “Mosquito” Bargas, was murdered at the time of the arrest. Campbell was probably spared this fate by being a foreigner. In his tribute to his friend In Memoriam of Mosquito, Campbell writes with typical stoicism and faith when beaten bloody and dragged through Toledo:

I never felt such glory

As handcuffs on my wrists.

My body stunned and gory

With tooth marks on my wrists . . .

While Spain was on the verge of civil war the Campbells were confirmed into the Church by Cardinal Goma, Archbishop of Toledo and Primate of Spain, in a secret ceremony.

In July 1938 the Government’s red guards killed parliamentary opposition leader Calvo Sotel, the leader of the monarchists. Four days later the military under General Franco revolted against the Government to restore order and liberty of worship. With the Alcazar being a military academy, Toldeo was easily taken by Nationalist troops, and peasants from the surrounding countryside fled to the city for refuge. The Government militia from Madrid prepared to attack Toledo, and the Alcazar was bombed and shelled. The Campbells hid the archives of the Carmelite monks at their home for the duration of the civil war.

Seventeen Carmelite monks were herded into the streets by the red forces and shot. Among them was the Campbell’s father confessor who died with a smile and the shout of “Long live Christ’ Long live Spain!” (Father Easebio who had received the Campbells into the Church was also killed).

In Campbell’s excursion into the city he came across the Carmelites lying in the street and found the bodies of the Marista monks. Smeared in their blood on a wall was: “Thus strike and Cheka,” a reference to the Soviet secret police. In the city square religious artifacts from churches and private homes were tossed onto bonfires.

In the besieged Alaczar were 1000 soldiers and 700 civilians, mostly women and children. Under the Command of Colonel Moscardo they held out, even as the Colonel’s 24-year-old son Louis, captured by the Red forces, was compelled to telephone his father and say that he would be shot unless Alcazar was surrendered. In an epic of heroism and martyrdom that helped make Alcazar a shrine to this day the Colonel replied to his son: “Commend your soul to God, shout ‘Viva Espana!’ And die like a hero. The Alcazar will never surrender.”

The Campbells left Spain and returned to London. They felt isolated in England where most of the literati supported the “Left” in the Spanish civil war. The family soon moved to a fishing village in Portugal, a nation that retained the same spirit of faith and tradition as Spain.

Campbell returned to Spain as a correspondent for the British Catholic newspaper The Tablet and was given safe conduct to the Madrid front. His desire to enlist in the Nationalist forces was unsuccessful as the Nationalist authorities were insistent that he could do more good for the cause as a writer. He was decorated for saving life under fire on multiple occasions, met Franco, and was present at the Nationalist victory parade in Madrid.

The Civil War was to result in the murder of 12 bishops. 4,184 priests, 2,365 monks, and around 300 nuns. George Orwell who had gone to Spain along with others of the literati to fight with the Reds, was to remark that, “Churches were pillaged everywhere as a matter of course in six months in Spain I only saw two undamaged churches” (Homage to Catalonia).

Flowering Rifle

Campbell’s epic saga Flowering Rifle is a detailed explanation of his poetical credo, a tribute to his Catholicism, to Spain’s faith and martyrdom and also a condemnation of the British intelligentsia. It his introductory note Campbell explains that “humanitarianism” is the “ruling passion” of the British intelligentsia which

sides automatically with the Dog against the Man, the Jew against the Christian, the black against the white, the servant against the master, the criminal against the judge.

As a form of “moral perversion” it was natural that such humanitarians sided with Bolshevik mass murderers. The poem begins with a description of the (fascist) salute, the “opening palm, of victory” the sign, of “palms triumphant foresting the day.” By contrast is the clenched fist of communism, “a Life-constricting tetanus of fingers,” the sign of an “outworn age” under which “all must starve under the lowest Caste.” The Bloomsbury intelligentsia represents the connection between capitalism and communism. Behind these stand “the Yiddisher’s convulsive gold”: one of many allusions to the prominent role played by Jews in Communism and in the International Brigades.

Spain is heralded as a resurrected nation that might show the rest of Europe the path to regeneration and stand against Bolshevism “which no godless democracy could quell.” The martyrs of the Nationalist cause are described in mystical terms, each death “a splinter of the Cross,” each body building a Cathedral to the sky. Nobility is achieved through suffering and sacrifice, as Christ, the “Captain” suffered. But when suffering and sacrifice are eliminated from life mankind is “shunned by the angels as effete baboons.”

Primo de Rivera, the charismatic young leader of the Falangists who had been shot without trial while in the custody of the Leftist Government, was similarly eulogized:

Whose phoenix blood in generous libation

With fiery zest rejuvenates the nation . . .

The Marxist deaths on the other hand were vacuous, for their gods are economics, science, gold, and sex, and as exponents of abortion and birth control they are the essence of anti-life. But capitalism, is just as much a debasement of man, as communism:

To cheapen thus for slavery and hire

The racket of the Invert and the Jew

Which is through art and science to subdue.

Humiliate, and to pulp reduce

The Human Spirit for industrial use

Whether by Capital or by Communism

It’s all the same despite their seeming schisms

Those who are debased the most are, under democracy, elevated to positions of honor and state, elected by the voting masses who are mesmerized by the media and the literati, the politicians hang about the League of Nations

That sheeny club of communists and masons

He bombs the Arabs, when his Jews invade.

Britannia’s trident had become a “graveyard spade” while condemning Germany and Italy. “Who from the dead have raised more vital forces…” Franco, Mussolini, and Portugal’s Salazar had “muzzled up the soul destroying lie” of communism, and as Spain had shown, victory would come through nationhood, not League sanctions, wealth or arms. Meanwhile Britain shunned its unbought men, such as Campbell who brings “the tidings that Democracy is dead.”

When the Campbells traveled to Italy in 1938 the exiled Spanish king Alfonso XIII, who was greatly impressed with Flowering Rifle, cordially greeted them. Of course the British literati were outraged, and even some Catholics felt the poem lacked “charity.”

War Service

Campbell and his wife returned to Toledo in 1939, the Nationalists having triumphed. But there was now widespread famine. Mary opened a soup kitchen and refurbished the damaged chapel, and both literally gave their clothes away to help the distressed inhabitants. As the world war approached Campbell considered that there would be two great contending forces: Fascism and Communism. With the exception of what he considered to be a pagan orientation in Germany, the Fascist states were eminently Christian and allowed Christians the right to live, whereas Bolshevism simply killed and degraded everything, being the enemy of every form of religion.

However, despite his antagonism to the English bourgeoisie and democratic Britain, Campbell always had an admiration for the heroic spirit of the British Empire and a feeling for those Britons facing an enemy. He sought to enlist, although under no illusions about the justice of the Allied cause. His animosity by this time was against all systems, fascism, democracy, and bolshevism, which he dubbed as Fascidemoshevism.

His ideal was not the cumbersome state of any of these systems but that of small, self-reliant and co-operating, family based communities, like those he had experienced in Provence, Spain, and Portugal.

In the Moon of Short Rations Campbell considered the Allied cause to be that of both socialism and the multi-national corporations, twin figures of a universal sameness. He saw that the post-war world would be ever more depersonalized and mechanical. Campbell could not sit still or take a soft option as a number of his pro-war Left-wing intellectual accusers were doing while Britons marched to war. He lampooned these hypocrites such as Spender and Cecil Day-Lewis who had a job in the Ministry of Information, when they attacked his “fascism,” and he wrote The Volunteer’s Reply to the Poet stating:

It will be the same, but a bloody sight worse . . .

Since you have a hand in the game . . .

You coin us the catchwords and phrases

For which to be slaughtered . . .

However, because of his age and a bad hip Campbell, had to be content with the home guard until 1942 when he was recruited into the Army Intelligence Corps due to his skills in languages. Britain in wartime had in Campbell’s view awakened from its “drabness” to become again a “warrior nation.” Campbell was popular with the troops as a “grandfatherly” figure, and was stationed in East Africa. Contracting malaria and with a deteriorating hip condition necessitating the use of a cane, he was discharged with an “excellent military record”

The Post-War World

The England of the post-war years returned to its drab routine and worse still for Campbell, the prospects of an all-consuming welfare state. Campbell soon went back into fighting mode against the Left-wing poets with The Talking Bronco (a name that Spender had applied to him). Even Vita Sackville-West, calling Campbell “one of our most considerable living poets” acclaimed this volume. Desmond McCarthy writing in The Sunday Times regarded Campbell as “the most democratic poet,” not politically, but in his feeling for the common man and for the common soldier. Others were of course outraged. Cecil Day-Lewis believed Campbell should be sacked as a “fascist” from the job he now had as producer of the BBC talk programs, since he was not fit to “direct any civilized form of cultural expression.”

Campbell was horrified by the Allied victory that had placed half of Europe under the USSR. However, he was equally horrified by the rest of the world falling under the dominion of the multinational corporations and their creed of global consumerism, or what we today call globalization. For Campbell the Cold War was a contention between two equally internationalist forces.

His daughter Anna wrote in 1999 that Campbell admired all types of ethnic civilization as opposed to the mass conformity of Marxism and the globalization of the likes of MacDonalds and Coca-Cola. His concern was in “everything becoming the same.” He would have been “horrified by what the world has become now” she wrote.

Despite Campbell’s sensitivity to being called a “fascist,” he was unapologetically a man of the “Right,” of tradition and nationalism, and continued to forthrightly expound this position after the war in his poetry and essays. Writing in “A Decade in Retrospect” in the Jesuit journal The Month May 1950, he refers to the “Gaderene stampede” of progress for the want of two sensible standbys (a brake and a steering wheel). In “Tradition and Reaction,” he writes: “A body without reactions is a corpse. So is a Society without Tradition.”

In 1949 Campbell left his job with the BBC to take over the editorship of The Catacomb, founded by his close friend the poet Rob Lyie as a defense of Catholic and Classical traditions against socialism and secularism.

The Catacomb stopped publication in 1951. In 1952 the family moved to Portugal. Before leaving England, Campbell got together with a number of South African literary friends and signed an open letter to the South African Government protesting voting restrictions on the colored population. However, Campbell’s misgivings about the South African situation were not prompted by the liberal desire for a democratic, monocultural state. He feared that antagonism between the races would result in Bolshevism and the destruction of his rustic ideal. With the advent of Black rule, free market capitalism was ushered in on the wings of Marxism and revolution. Today the ANC today calls globalization and trade liberalization the “correct path to Marxism-Leninism.”

In 1954 his views on his native land were given when accepting an honorary doctorate from Natal. In an off the cuff speech, much to the embarrassment of the liberal audience, he defended South Africa against England’s condemnation of apartheid, ridiculing Churchill and Roosevelt, who had sold “two hundred million natives of Europe” to the far worse slavery of bolshevism.

While in the USA on a speaking tour he praised “the two greatest Yanks” Senator McCarthy and General MacArthur.

In April 1957 returning from Spain, Campbell and his wife had a motor accident. Campbell’s neck was broken, and he died at the scene. Mary survived him by 22 years.

Edith Sitwell who converted to Catholicism through the example of the Campbells, remarked: “He died as he had lived, like a flash of lightning.”

C’est à la fin du VIIe siècle avant la naissance du Christ qu’apparaît en Toscane une population que les Latins appelleront Tusci ou Etrusci, dont les origines continuent de rester énigmatiques. On suggère aujourd’hui que la culture étrusque est née d’un ancien substrat local qui s’est lentement modifié au cours des différentes vagues de population s’installant en Italie, tandis que l’hypothèse qui prévalait au début du siècle passé rejoignait le récit d’Hérodote, d’après lequel ce peuple serait venu par la mer de Lydie.

C’est à la fin du VIIe siècle avant la naissance du Christ qu’apparaît en Toscane une population que les Latins appelleront Tusci ou Etrusci, dont les origines continuent de rester énigmatiques. On suggère aujourd’hui que la culture étrusque est née d’un ancien substrat local qui s’est lentement modifié au cours des différentes vagues de population s’installant en Italie, tandis que l’hypothèse qui prévalait au début du siècle passé rejoignait le récit d’Hérodote, d’après lequel ce peuple serait venu par la mer de Lydie.  Lawrence, suivant en cela la leçon d’un nombre incalculable d’auteurs mais sans toutefois tomber dans le délire de certains qui, comme Keyserling, fonda à Darmstadt en 1920 une École de la Sagesse dénonçant les limites de la culture occidentale et puisant son enseignement de pacotille dans une Inde fantasmée, confère au monde ancien une vertu éminente : au contraire de ce que nous pouvons constater à notre époque de spécialistes qui poussent de grands cris dès qu’un esprit un peu audacieux essaie de créer des passerelles entre plusieurs domaines de savoir, le monde ancien ne craignait pas d’établir des parentés symboliques, donc réelles, entre les êtres vivants et les choses, reliés par un flux souterrain de sang (5). «Merveilleux monde, écrit ainsi Lawrence, qu’était sans doute ce monde ancien où toutes choses semblaient vivantes, luisantes dans l’ombre crépusculaire du contact qui les faisait se toucher, un monde où chaque chose n’était pas seulement une individualité isolée prise au piège de la lumière diurne; où chaque chose apparaissait en son clair contour, visuellement, mais qui du sein de sa clarté même était reliée par des affinités émotionnelles ou vitales à d’autres choses étranges, une chose surgissant d’une autre, mentalement contradictoires qui fusionnaient dans l’émotion, si bien qu’un lion pouvait au même instant être aussi une chèvre, et ne pas être une chèvre [Lawrence a évoqué précédemment la chimère en bronze d’Arezzo, conservée au musée de Florence et qui fut en partie restaurée par Benvenuto Cellini)» (p. 142).

Lawrence, suivant en cela la leçon d’un nombre incalculable d’auteurs mais sans toutefois tomber dans le délire de certains qui, comme Keyserling, fonda à Darmstadt en 1920 une École de la Sagesse dénonçant les limites de la culture occidentale et puisant son enseignement de pacotille dans une Inde fantasmée, confère au monde ancien une vertu éminente : au contraire de ce que nous pouvons constater à notre époque de spécialistes qui poussent de grands cris dès qu’un esprit un peu audacieux essaie de créer des passerelles entre plusieurs domaines de savoir, le monde ancien ne craignait pas d’établir des parentés symboliques, donc réelles, entre les êtres vivants et les choses, reliés par un flux souterrain de sang (5). «Merveilleux monde, écrit ainsi Lawrence, qu’était sans doute ce monde ancien où toutes choses semblaient vivantes, luisantes dans l’ombre crépusculaire du contact qui les faisait se toucher, un monde où chaque chose n’était pas seulement une individualité isolée prise au piège de la lumière diurne; où chaque chose apparaissait en son clair contour, visuellement, mais qui du sein de sa clarté même était reliée par des affinités émotionnelles ou vitales à d’autres choses étranges, une chose surgissant d’une autre, mentalement contradictoires qui fusionnaient dans l’émotion, si bien qu’un lion pouvait au même instant être aussi une chèvre, et ne pas être une chèvre [Lawrence a évoqué précédemment la chimère en bronze d’Arezzo, conservée au musée de Florence et qui fut en partie restaurée par Benvenuto Cellini)» (p. 142). C’est dans un chapitre inachevé, resté à l’état de manuscrit et qui, peut-être, eût pu servir à Lawrence de conclusion pour ses Croquis étrusques, intitulé Le musée de Florence, que l’auteur va systématiser ses intuitions sur le thème d’une déperdition, au travers des siècles, d’une force rayonnante qui s’échappe désormais inéluctablement des œuvres des hommes. Ainsi, selon Lawrence, nous devons bien comprendre que les religions elles-mêmes de nos ancêtres les plus magnifiques, comme le sont, à ses yeux, les Étrusques, ne sont que des bribes d’un savoir immémorial ayant précédé les plus anciennes civilisations : «Ce qu’il nous faut saisir lorsque nous contemplons des œuvres étrusques, c’est que celles-ci nous révèlent les derniers feux d’une conscience cosmique humaine – disons, la tentative d’hommes aspirant à la conscience cosmique – différente de la nôtre. L’idée qui veut que notre histoire soit issue des cavernes ou de précaires habitats lacustres est puérile. Notre histoire prend corps à l’achèvement d’une phase précédente de l’histoire humaine, une phase prodigieuse et comparable à la nôtre. Il est bien plus vraisemblable que le singe descende de nous que nous du singe» (p. 225). Renversement de perspective qui a dû faire bondir les esprits scientistes ou chagrins, c’est tout un, qui lurent les Croquis étrusques lorsqu’ils furent publiés ! On se demande même comment l’auteur n’a semble-t-il pas été traité de réactionnaire. Il l’a peut-être été, à la réflexion, tout comme on n’a pas manqué de lui reprocher son manque de sérieux scientifique (cf. la réception du livre, pp. 272-278). Citons donc longuement ce très beau passage, toujours extrait du même texte qui ne fut pas recueilli en livre par Lawrence, où il semble sérieusement douter de la théorie de l’évolution, l’homme ayant toujours été un homme, l’homme ne provenant pas du singe comme nous l’avons vu mais l’homme, pourtant, depuis qu’il s’est coupé de ses plus profondes racines de savoir symbolique, paraissant en revanche devoir dégénérer, dévoluer : «Les civilisations apparaissent comme des vagues, et comme des vagues elles s’évanouissent. Tant que la science, ou l’art, n’aura pu saisir le sens dernier de ces symboles flottant sur l’ultime vague de la période préhistorique, c’est-à-dire cette période qui précède la nôtre, nous ne serons pas en mesure d’instituer la juste relation avec l’homme en ce qu’il est, en ce qu’il fut, en ce que toujours il sera.

C’est dans un chapitre inachevé, resté à l’état de manuscrit et qui, peut-être, eût pu servir à Lawrence de conclusion pour ses Croquis étrusques, intitulé Le musée de Florence, que l’auteur va systématiser ses intuitions sur le thème d’une déperdition, au travers des siècles, d’une force rayonnante qui s’échappe désormais inéluctablement des œuvres des hommes. Ainsi, selon Lawrence, nous devons bien comprendre que les religions elles-mêmes de nos ancêtres les plus magnifiques, comme le sont, à ses yeux, les Étrusques, ne sont que des bribes d’un savoir immémorial ayant précédé les plus anciennes civilisations : «Ce qu’il nous faut saisir lorsque nous contemplons des œuvres étrusques, c’est que celles-ci nous révèlent les derniers feux d’une conscience cosmique humaine – disons, la tentative d’hommes aspirant à la conscience cosmique – différente de la nôtre. L’idée qui veut que notre histoire soit issue des cavernes ou de précaires habitats lacustres est puérile. Notre histoire prend corps à l’achèvement d’une phase précédente de l’histoire humaine, une phase prodigieuse et comparable à la nôtre. Il est bien plus vraisemblable que le singe descende de nous que nous du singe» (p. 225). Renversement de perspective qui a dû faire bondir les esprits scientistes ou chagrins, c’est tout un, qui lurent les Croquis étrusques lorsqu’ils furent publiés ! On se demande même comment l’auteur n’a semble-t-il pas été traité de réactionnaire. Il l’a peut-être été, à la réflexion, tout comme on n’a pas manqué de lui reprocher son manque de sérieux scientifique (cf. la réception du livre, pp. 272-278). Citons donc longuement ce très beau passage, toujours extrait du même texte qui ne fut pas recueilli en livre par Lawrence, où il semble sérieusement douter de la théorie de l’évolution, l’homme ayant toujours été un homme, l’homme ne provenant pas du singe comme nous l’avons vu mais l’homme, pourtant, depuis qu’il s’est coupé de ses plus profondes racines de savoir symbolique, paraissant en revanche devoir dégénérer, dévoluer : «Les civilisations apparaissent comme des vagues, et comme des vagues elles s’évanouissent. Tant que la science, ou l’art, n’aura pu saisir le sens dernier de ces symboles flottant sur l’ultime vague de la période préhistorique, c’est-à-dire cette période qui précède la nôtre, nous ne serons pas en mesure d’instituer la juste relation avec l’homme en ce qu’il est, en ce qu’il fut, en ce que toujours il sera.

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

For Lawrence capitalism destroyed the soul and the mystery of life, as did democracy and equality. He devoted most of his life to finding a new-yet-old religion that will return the mystery to life and reconnect humanity to the cosmos.

For Lawrence capitalism destroyed the soul and the mystery of life, as did democracy and equality. He devoted most of his life to finding a new-yet-old religion that will return the mystery to life and reconnect humanity to the cosmos. La guerre anglo-américaine de 1812 a eu notamment pour cause l’avancée continue de nouveaux colons américains dans la région située entre l’Ohio et le Mississippi. Ce territoire était contesté entre les deux puissances : Britanniques et Américains le convoitaient. Le Président Jefferson avait déjà formulé des menaces en 1807 : « Si l’Angleterre ne nous donne pas satisfaction, comme nous le souhaitons, nous prendrons le Canada qui pourra alors entrer dans l’Union » (1). La clique gouvernementale au pouvoir à Washington à l’époque prévoyait déjà, en cas de guerre avec l’Angleterre, de prendre possession de la Floride orientale et occidentale qui appartenaient encore à l’Espagne (2).

La guerre anglo-américaine de 1812 a eu notamment pour cause l’avancée continue de nouveaux colons américains dans la région située entre l’Ohio et le Mississippi. Ce territoire était contesté entre les deux puissances : Britanniques et Américains le convoitaient. Le Président Jefferson avait déjà formulé des menaces en 1807 : « Si l’Angleterre ne nous donne pas satisfaction, comme nous le souhaitons, nous prendrons le Canada qui pourra alors entrer dans l’Union » (1). La clique gouvernementale au pouvoir à Washington à l’époque prévoyait déjà, en cas de guerre avec l’Angleterre, de prendre possession de la Floride orientale et occidentale qui appartenaient encore à l’Espagne (2). Europa im Jahre 2010 ist ein Europa der Fronten, die sich langsam aber sicher bilden. In allen europäischen Ländern gibt es große Parallelgesellschaften. In fast allen dieser Länder hat sich aber auch nennenswerter Widerstand gebildet. Ob liberal, konservativ, sozialistisch, regionalistisch oder faschistisch, alle diese Formen treten auf und erzeugen unterschiedliche Wirkungen. In Großbritannien stellen sich vornehmlich drei Parteien dem Problem der Islamisierung.

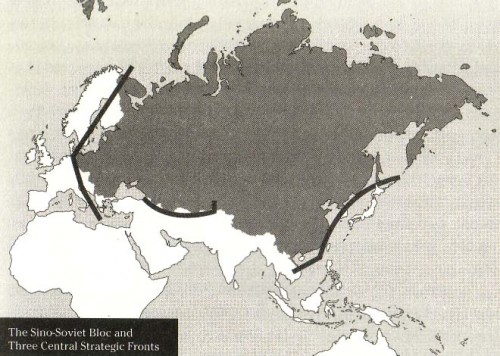

Europa im Jahre 2010 ist ein Europa der Fronten, die sich langsam aber sicher bilden. In allen europäischen Ländern gibt es große Parallelgesellschaften. In fast allen dieser Länder hat sich aber auch nennenswerter Widerstand gebildet. Ob liberal, konservativ, sozialistisch, regionalistisch oder faschistisch, alle diese Formen treten auf und erzeugen unterschiedliche Wirkungen. In Großbritannien stellen sich vornehmlich drei Parteien dem Problem der Islamisierung. Qui était le géopoliticien britannique Mackinder, génial concepteur de l'opposition entre thalassocraties et puissances océaniques? Un livre a tenté de répondre à cette question: Mackinder, Geography as an Aid to Statecraft, par W.H. Parker. Né dans le Lin-colnshire en 1861, Sir Halford John Mackinder s'est interessé aux voyages, à l'histoire et aux grands événements internationaux dès son enfance. Plus tard, à Oxford, il étu-diera l'histoire et la géologie. Ensuite, il entamera une brillante carrière universitaire au cours de laquelle il deviendra l'impulseur principal d'institutions d'enseignement de la géographie. De 1900 à 1947, il vivra à Londres, au coeur de l'Empire Britannique. Sa préoccupation essentielle était le salut et la préservation de cet Empire face à la montée de l'Allemagne, de la Russie et des Etats-Unis. Au cours de ces cinq décennies, Mackinder sera très proche du monde poli-tique britannique; il dispensera ses conseils d'abord aux "Libéraux-Impérialistes" (les "Limps") de Rosebery, Haldane, Grey et Asquith, ensuite aux Conservateurs regroupés derrière Chamberlain et décidés à aban-donner le principe du libre échange au profit des tarifs préférentiels au sein de l'Empire. La Grande-Bretagne choisissait une économie en circuit fermé, tentait de construire une économie autarcique à l'échelle de l'Empire. Dès 1903, Mackinder classe ses notes de cours, fait confectionner des cartes historiques et stratégiques sur verre destinées à être projetées sur écran. Une oeuvre magistrale naissait.

Qui était le géopoliticien britannique Mackinder, génial concepteur de l'opposition entre thalassocraties et puissances océaniques? Un livre a tenté de répondre à cette question: Mackinder, Geography as an Aid to Statecraft, par W.H. Parker. Né dans le Lin-colnshire en 1861, Sir Halford John Mackinder s'est interessé aux voyages, à l'histoire et aux grands événements internationaux dès son enfance. Plus tard, à Oxford, il étu-diera l'histoire et la géologie. Ensuite, il entamera une brillante carrière universitaire au cours de laquelle il deviendra l'impulseur principal d'institutions d'enseignement de la géographie. De 1900 à 1947, il vivra à Londres, au coeur de l'Empire Britannique. Sa préoccupation essentielle était le salut et la préservation de cet Empire face à la montée de l'Allemagne, de la Russie et des Etats-Unis. Au cours de ces cinq décennies, Mackinder sera très proche du monde poli-tique britannique; il dispensera ses conseils d'abord aux "Libéraux-Impérialistes" (les "Limps") de Rosebery, Haldane, Grey et Asquith, ensuite aux Conservateurs regroupés derrière Chamberlain et décidés à aban-donner le principe du libre échange au profit des tarifs préférentiels au sein de l'Empire. La Grande-Bretagne choisissait une économie en circuit fermé, tentait de construire une économie autarcique à l'échelle de l'Empire. Dès 1903, Mackinder classe ses notes de cours, fait confectionner des cartes historiques et stratégiques sur verre destinées à être projetées sur écran. Une oeuvre magistrale naissait.

15 janvier 1821

15 janvier 1821 Archives de SYNERGIES EUROPEENNES - 1990

Archives de SYNERGIES EUROPEENNES - 1990 Ensuite, après l'effondrement des rêves bonapartistes de conquête de l'Orient consécutif à la bataille perdue du Nil, les Britanniques purent débloquer des ressources considérables pour asseoir leur domination aux Indes et s'emparer de colonies étrangères dont le site détenait une importance stratégique. Au Congrès de Vienne en 1815, c'est un second Empire britannique, fermement établi, qui se présentait face aux autres puissances européennes.

Ensuite, après l'effondrement des rêves bonapartistes de conquête de l'Orient consécutif à la bataille perdue du Nil, les Britanniques purent débloquer des ressources considérables pour asseoir leur domination aux Indes et s'emparer de colonies étrangères dont le site détenait une importance stratégique. Au Congrès de Vienne en 1815, c'est un second Empire britannique, fermement établi, qui se présentait face aux autres puissances européennes.