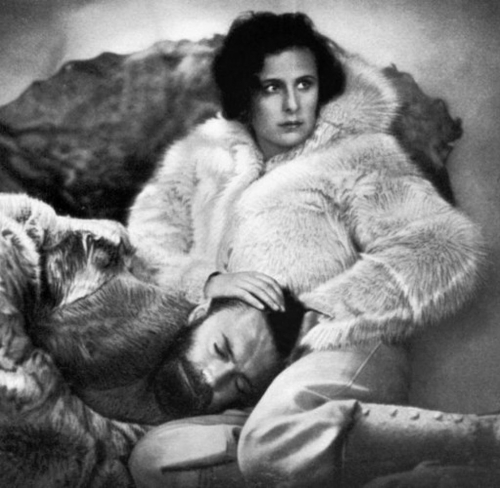

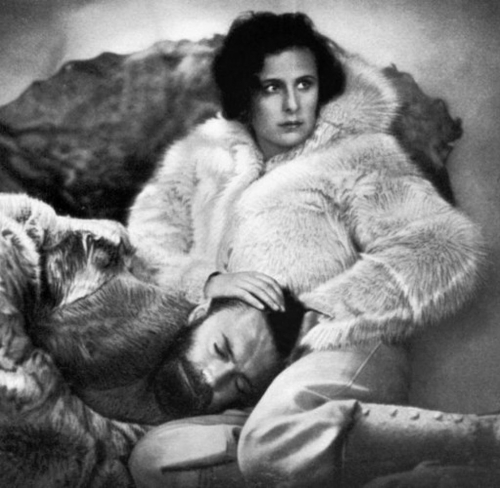

Leni Riefenstahl was an extraordinary woman of extraordinary accomplishment in many creative fields. Angelika Taschen writes of Riefenstahl:

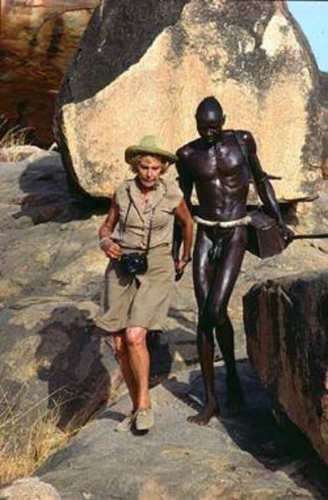

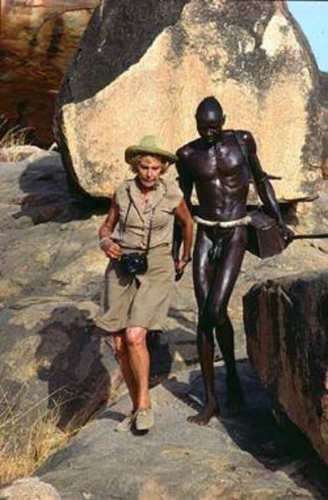

She began as a celebrated dancer in Berlin during the early twenties, became an actress, then finally directed and produced her own films, several of which are among the most influential and most controversial in the history of film. Since the fifties she has traveled frequently to Africa and has lived for extended periods in the Sudan with the primitive Nuba tribes. Though long since a legend, she again attracted worldwide attention with her photographs of the Nuba. Then, at 71, she learned to dive and yet again turned her experiences into art with photographs of the undersea world.[1]

This article focuses on Riefenstahl’s remarkable career and the impact her association with Adolf Hitler had on her career, reputation, and life.

Early Career

Leni Riefenstahl showed talent in the arts, gymnastics and physical accomplishment early. Her first career choice of dance allowed her to merge her athletic abilities with her artistic powers and desire to express herself. Riefenstahl began dance training at Age 17, and by Age 21 she was making highly successful public appearances as a dancer. She traveled throughout Germany and many neighboring countries, scheduling dance performances almost every third day. In June 1924, she injured a knee during one of her leaps, forcing a cancellation of her tour. The resulting torn ligament in her knee ended her dancing career barely eight months after it had begun.[2]

Riefenstahl next pursued a career as an actress in “mountain films,” a genre specific to Germany which began its heyday in the first half of the 1920s. The self-confident Riefenstahl was given the lead in the movie The Holy Mountain even though she had never appeared in a major role. The film opened in December 1926 and enjoyed great success with both critics and the public. Riefenstahl was celebrated in the press as a new type of film actress, and the term “sports actress” was coined for her.[3]

After acting in some more mountain movies, Riefenstahl starred in the movie S.O.S. Iceberg set in Greenland. This film premiered on August 31, 1933 and was a big success. Everyone wanted to see the first movie ever filmed in the fascinating setting of Greenland; theaters were sold out days in advance. Few would have guessed this would be the last film Riefenstahl would act in for many years to come.[4]

Riefenstahl also set out to secure her place in film history by acting as producer, director, screenwriter, editor and star of the movie The Blue Light. This movie used many real-life farmers as actors, and included many authentic images of farmhouses, alpine huts and village churches. The film opened on March 24, 1932 to mixed reviews. However, Adolf Hitler was highly impressed by the realistic scenes of the farmers in the movie. Hitler later said, “Riefenstahl does it the right way, she goes to the villages and picks out her actors herself.”[5]

Hitler’s Filmmaker

Riefenstahl was invited to meet with Hitler on May 22, 1932 at the North Sea Village of Horumersiel. Strolling on the beach, Hitler and Riefenstahl talked about her films, all of which Hitler had seen. Hitler said during the conversation, “Once we come to power, you must make my films.”[6]

Riefenstahl had read Mein Kampf and she agreed to make films for Hitler. Riefenstahl’s first movie for Hitler was Victory of Faith, which premiered on December 1, 1933. Since this movie showed repeated scenes of Ernst Röhm laughing or marching at Hitler’s side, it was withdrawn shortly after Röhm’s murder on July 1, 1934.[7] The film was also not Riefenstahl’s best work. The photography is mediocre in substantial sections of the film, and it lacked the overall unity of her later films.[8]

Riefenstahl’s next film for Hitler, Triumph of the Will, was a huge artistic and financial success. Steven Bach writes:

Ordinary Germans’ response to Triumph of the Will was the measure of homeland success. The picture played in major theaters and minor, in school auditoriums and assembly halls, in churches and barracks. Its final revenues are not known, but Ufa reported that the film had earned back its advance and gone into profit just two months after its release…Agreement was all but universal that, at only 32, she had created a new kind of heroic cinema. With art and craft, she had wed power and poetry so compellingly as to challenge the artistry of anything remotely similar that had gone before. Her manipulation of formal elements was virtuosic, her innovations in shooting and editing set new standards and remain exemplary for filmmakers seven decades later, when the controversy the film continues to generate is, in itself, testimony to its effectiveness.[9]

After the opening of Triumph of the Will in March 1935, Riefenstahl made the 28-minute film Day of Freedom in tribute to the German military. This movie served as a technical rehearsal for cameramen she had assembled for her next big assignment—the 1936 Berlin Olympics.[10]

Riefenstahl covered all 136 Olympic events because her contract required her to prepare a sports film archive from which short films could be made for educational use. She therefore told her extensive team of cameramen and assistants that “everything would have to be shot and from every conceivable angle.” Her film Olympia premiered on April 20, 1938, which was Hitler’s 49th birthday. Olympia was universally acclaimed, and Riefenstahl became the most-celebrated woman in all of Germany.[11]

During World War II, Riefenstahl saved many of her colleagues from conscription by forming a combat-photographic unit. A “Special Riefenstahl Film Unit” composed of her handpicked film personnel departed Berlin for the front on September 10, 1939.

When gunfire shredded the canvas of her tent on September 12, Riefenstahl remarked, “I hadn’t imagined it would be this dangerous.” Riefenstahl resigned her commission after a German anti-partisan action in Konskie, Poland resulted in the deaths of approximately 30 Polish civilians.[12]

Riefenstahl spent much of the rest of the war working on the film Tiefland. This movie became one of the most-expensive motion pictures in German film history. War conditions and Riefenstahl’s erratic health and personal life were major factors in the record-breaking five years it took to produce the movie. Riefenstahl was taken at the end of the war to an American detention camp where G.I.s too young to remember her face on the covers of Time and Newsweek examined her identity papers.[13]

Postwar Injustices

Leni Riefenstahl reunited with her husband, Peter Jacob, shortly after the war. Since neither Riefenstahl nor her husband nor her mother nor any of her three assistants had ever joined the Nazi Party, nor had any of them been politically active, she did not expect any problems from her captors. Unfortunately, she was wrong.[14]

Riefenstahl wrote:

[We] were wakened by the sound of tires screeching, engines stopping abruptly, orders yelled, general din, and a hammering on the window shutters. Then the intruders broke through the door, and we saw Americans with rifles who stood in front of our bed and shone lights at us. None of them spoke German, but their gestures said: ‘Get dressed, come with us immediately.’

This was my fourth arrest, but now my husband was with me, and we got to know the victors from a very different aspect. They were no longer the casual gangling GIs; these were soldiers who treated us roughly.[15]

Riefenstahl described her fifth arrest:

The jeep raced along the autobahns until…I was brought to the Salzburg Prison; there an elderly prison matron rudely pushed me into the cell, kicking me so hard that I fell to the ground; then the door was locked. There were two other women in the dark, barren room, and one of them, on her knees, slid about the floor, jabbering confusedly; then she began to scream, her limbs writhing hysterically. She seemed to have lost her mind. The other woman crouched on her bunk, weeping to herself.

I found myself in a prison cell for the first time, and it is an unbearable feeling. I pounded on the door, becoming so desperate that I eventually smashed my body against it with all my strength, until I collapsed in exhaustion. I felt that incarceration was worse than capital punishment, and I did not think I could survive a long term of imprisonment.[16]

Riefenstahl was eventually released from American custody only to be imprisoned by the French shortly thereafter. The weeks she spent in Innsbruck Women’s Prison caused her to want to commit suicide. Riefenstahl was arrested at least four times in the French Zone, and was eventually transferred to the ruins of Breisach, where she suffered from hunger. She was later transferred to Königsfeld, where the poverty and hunger was as great as it was in Breisach.[17]

Riefenstahl was eventually released from American custody only to be imprisoned by the French shortly thereafter. The weeks she spent in Innsbruck Women’s Prison caused her to want to commit suicide. Riefenstahl was arrested at least four times in the French Zone, and was eventually transferred to the ruins of Breisach, where she suffered from hunger. She was later transferred to Königsfeld, where the poverty and hunger was as great as it was in Breisach.[17]

Two years had passed since the end of the war, and no court trial of any kind had been slated for Riefenstahl. The French military government next transferred Riefenstahl to Freiburg, where she was locked up in a mental institution. After this three-month incarceration, she was transferred to Königsfeld, where she was required to report weekly to the French military authorities in Villingen.[18]

Riefenstahl was eventually forced to attend denazification hearings. Her first hearing was held in Villingen at the end of 1948. She won her case primarily because she had not been a party member. The French military government appealed her favorable ruling, and a second hearing was conducted in Freiburg in July 1949. Riefenstahl was again judged innocent, and the Baden State Commission on Political Purgation appealed this ruling. In her third trial, the Baden commission concluded that Riefenstahl, though innocent of specific crimes, had consciously and willingly served the Reich. She was classified as a “fellow traveler,” the next-to-lowest of the five degrees of complicity.[19]

Riefenstahl initiated a final hearing in Berlin in spring 1952 to recover her villa in Dahlem, which had been held by the Allies since the end of the war. The vital matter of Riefenstahl’s postwar classification as a “fellow traveler” was settled at this hearing. Since this classification carried no prohibitions or penalties, Riefenstahl was free to work again, although her film projects were repeatedly thwarted after the war.[20]

Postwar Fortunes

Leni Riefenstahl was widely pilloried for the positive statements she had made about Hitler before the war. For example, in February 1937 she told a reporter from the Detroit News: “To me, Hitler is the greatest man who ever lived. He truly is without fault, so simple and at the same time possessed of masculine strength. He asks nothing, nothing for himself. He’s really wonderful, he’s smart. He just radiates. All the great men of Germany—Frederick the Great, Nietzsche, Bismarck—had faults. Nor are those who stand with Hitler without fault. Only he is pure.”[21]

Despite such glowing statements, Riefenstahl’s association with Hitler was motivated primarily to advance her artistic career. Jürgen Trimborn writes:

Leni Riefenstahl began making films for the Führer in 1933, a career she could not have imagined one year before. Her cooperation with Hitler and the National Socialists was, in the end, based less on her fascination with their political program than on the opportunities that suddenly opened up to her in terms of artistic development. Of much greater importance to her than the “historical mission” of the Führer [were] her own career possibilities. The “new Germany” promulgated by the National Socialists would also make room for her, the insufficiently recognized artist.[22]

Riefenstahl when incarcerated by the Allies was frequently forced to inspect pictures from the German camps, and told that she must have known about these death camps. Steven Bach writes:

She was forced to look at photographs, images of Dachau. “I hid my face in my hands,” she recalled, as if the ordeal of viewing them equaled the horrors they depicted. She was not permitted to look away from the “gigantic eyes peering helplessly into the camera” from the hells of Dachau, Auschwitz, Buchenwald, Bergen-Belsen, and other death camps of which, she told the Americans, she had known nothing.[23]

Riefenstahl was telling the truth when she said she knew nothing about conditions in these German camps. In fact, the Allies were deceiving Riefenstahl by not telling her that most of the deaths in these camps occurred from natural causes. The Allies used these gruesome pictures from the German camps to induce guilt in Riefenstahl and the rest of the German people.

Riefenstahl was also criticized for still supporting Hitler after witnessing the massacre of approximately 30 Jewish civilians in Konskie, Poland. This incident occurred after Polish partisans in Konskie had killed and mutilated a German officer and four soldiers. While such anti-partisan incidents were common during the war, they did not indicate a German plan of genocide against the Poles or the Jews. Riefenstahl was not complicit in this anti-partisan action, and she promptly terminated her film reporting of the war after this incident.[24]

Riefenstahl was also criticized for still supporting Hitler after witnessing the massacre of approximately 30 Jewish civilians in Konskie, Poland. This incident occurred after Polish partisans in Konskie had killed and mutilated a German officer and four soldiers. While such anti-partisan incidents were common during the war, they did not indicate a German plan of genocide against the Poles or the Jews. Riefenstahl was not complicit in this anti-partisan action, and she promptly terminated her film reporting of the war after this incident.[24]

Riefenstahl was smeared as a “Nazi monster” by many newspapers and magazines long after the war was over. Riefenstahl wrote:

They forged anything and everything. French newspapers ran love letters supposedly written by [Julius] Streicher. L’Humanite and East German magazines put me on the same level as criminal perverts. There was nothing I wasn’t accused of. Other papers claimed that I had become a “cultural slave of the Soviets”, and had sold my films to Mos Film in Moscow for piles of rubles.[25]

Conclusion

Film scholar Dr. Rainer Rother writes: “There is no other famous artist from the period of the Nazi regime who has exhibited the kind of lasting influence as has Leni Riefenstahl.”[26]

Riefenstahl’s films will survive. Susan Sontag falsely wrote in regard to Riefenstahl’s films, “Nobody making films today alludes to Riefenstahl.” Steven Bach writes in response to Sontag’s statement:

That was true, of course, if you discounted everything from George Lucas’s Star Wars to the Disney Company’s The Lion King to every sports photographer alive to the ubiquitous, erotically charged billboards and slick magazine layouts to media politics that, everywhere in the world, remain both inspired and corrupted by work Leni perfected in Nuremberg and Berlin with a viewfinder that a film historian once warned suggested “the disembodied, ubiquitous eye of God.”[27]

Unfortunately, Riefenstahl’s genius is slighted because she made films for Hitler. Her stature will be fully restored once it is understood that Hitler had never wanted war and did not commit genocide against European Jewry.[28] Riefenstahl may then unreservedly be recognized as one of the greatest film artists of the 20th Century.

Endnotes

[1] Taschen, Angelika, Leni Riefenstahl: Five Lives, New York: Taschen, 2001, p. 16.

[2] Trimborn, Jürgen, Leni Riefenstahl: A Life, New York: Faber and Faber, Inc., 2002, pp. 13, 20-23.

[3] Ibid., pp. 26, 29-31.

[5] Ibid., pp. 38, 43, 48.

[6] Bach, Steven, Leni: The Life and Work of Leni Riefenstahl, New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2007, pp. 90-91.

[7] Ibid., pp. 86, 121, 131.

[8] Rather, Ranier, Leni Riefenstahl: The Seduction of Genius, New York: Continuum, 2002, p. 57.

[9] Bach, Steven, Leni: The Life and Work of Leni Riefenstahl, New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2007, pp. 139-140.

[11] Ibid., pp. 151, 164, 166.

[13] Ibid., pp. 208, 223.

[14] Riefenstahl, Leni, Leni Riefenstahl: A Memoir, New York: Picador USA, 1995, pp. 308, 327.

[17] Ibid., pp. 325-326, 329-332.

[19] Bach, Steven, Leni: The Life and Work of Leni Riefenstahl, New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2007, pp. 232-235.

[20] Ibid., pp. 235-237; Riefenstahl, Leni, Leni Riefenstahl: A Memoir, New York: Picador USA, 1995, p. 454.

[21] Trimborn, Jürgen, Leni Riefenstahl: A Life, New York: Faber and Faber, Inc., 2002, p. 212.

[23] Bach, Steven, Leni: The Life and Work of Leni Riefenstahl, New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2007, p. 224.

[25] Riefenstahl, Leni, Leni Riefenstahl: A Memoir, New York: Picador USA, 1995, p. 455.

[26] Trimborn, Jürgen, Leni Riefenstahl: A Life, New York: Faber and Faber, Inc., 2002, p. 274.

[27] Bach, Steven, Leni: The Life and Work of Leni Riefenstahl, New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2007, p. 298.

[28] Wear, John, Germany’s War: The Origins, Aftermath and Atrocities of World War II, Upper Marlboro, Md., American Free Press, 2014, pp. 15-197, 340-389.

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

Riefenstahl was eventually released from American custody only to be imprisoned by the French shortly thereafter. The weeks she spent in Innsbruck Women’s Prison caused her to want to commit suicide. Riefenstahl was arrested at least four times in the French Zone, and was eventually transferred to the ruins of Breisach, where she suffered from hunger. She was later transferred to Königsfeld, where the poverty and hunger was as great as it was in Breisach.

Riefenstahl was eventually released from American custody only to be imprisoned by the French shortly thereafter. The weeks she spent in Innsbruck Women’s Prison caused her to want to commit suicide. Riefenstahl was arrested at least four times in the French Zone, and was eventually transferred to the ruins of Breisach, where she suffered from hunger. She was later transferred to Königsfeld, where the poverty and hunger was as great as it was in Breisach. Riefenstahl was also criticized for still supporting Hitler after witnessing the massacre of approximately 30 Jewish civilians in Konskie, Poland. This incident occurred after Polish partisans in Konskie had killed and mutilated a German officer and four soldiers. While such anti-partisan incidents were common during the war, they did not indicate a German plan of genocide against the Poles or the Jews. Riefenstahl was not complicit in this anti-partisan action, and she promptly terminated her film reporting of the war after this incident.

Riefenstahl was also criticized for still supporting Hitler after witnessing the massacre of approximately 30 Jewish civilians in Konskie, Poland. This incident occurred after Polish partisans in Konskie had killed and mutilated a German officer and four soldiers. While such anti-partisan incidents were common during the war, they did not indicate a German plan of genocide against the Poles or the Jews. Riefenstahl was not complicit in this anti-partisan action, and she promptly terminated her film reporting of the war after this incident.

To his credit, Ryan does not spend much ink on critical analyses of the various presentations. That would make for a very fat and dreary book. In nearly every instance he’d have to tell us that the production was uneven and woefully miscast. I wondered if he was going to carp about the misconceived film adaptation of Keep the Aspidistra Flying (1997; American title: A Merry War). Not a bit of it; he leaves it to us to do the carping and ridicule. What he does provide is a rich concordance of Orwell presentations over the years, with often amazing production notes, technical details, and contemporary press notices. And if you don’t care to get that far into weeds, George Orwell on Screen is still an indispensable guidebook, pointing you to all sorts of bio-documentaries and dramatizations you might never discover on your own. This is particularly true of the many (mostly) BBC docos produced forty or fifty years ago, where you find such delights as Malcolm Muggeridge and Cyril Connolly lying down in tall grass and trading tales about their late, great friend.

To his credit, Ryan does not spend much ink on critical analyses of the various presentations. That would make for a very fat and dreary book. In nearly every instance he’d have to tell us that the production was uneven and woefully miscast. I wondered if he was going to carp about the misconceived film adaptation of Keep the Aspidistra Flying (1997; American title: A Merry War). Not a bit of it; he leaves it to us to do the carping and ridicule. What he does provide is a rich concordance of Orwell presentations over the years, with often amazing production notes, technical details, and contemporary press notices. And if you don’t care to get that far into weeds, George Orwell on Screen is still an indispensable guidebook, pointing you to all sorts of bio-documentaries and dramatizations you might never discover on your own. This is particularly true of the many (mostly) BBC docos produced forty or fifty years ago, where you find such delights as Malcolm Muggeridge and Cyril Connolly lying down in tall grass and trading tales about their late, great friend.

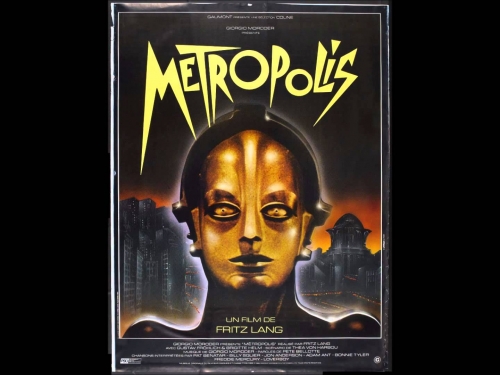

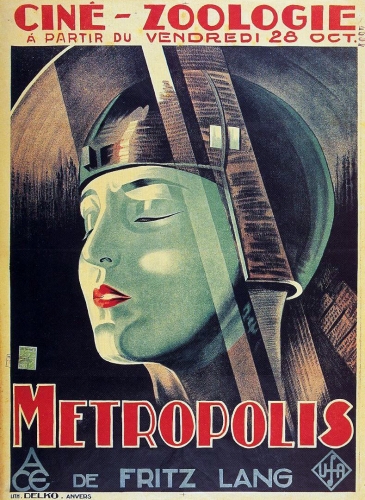

On l’aura au moins dit une fois.

On l’aura au moins dit une fois. Le film donc dénonçait notre déshumanisation progressive et indolore sous l’effet de la technique et de la communication. Et ce n’est pas moi qui le dit mais

Le film donc dénonçait notre déshumanisation progressive et indolore sous l’effet de la technique et de la communication. Et ce n’est pas moi qui le dit mais

Cinematographer Franz Lustig’s opening scenes confront even the most unsuspecting and ill-informed audience with the sight of an almost obliterated Hamburg filled with crumbling buildings. Raw footage shows, or at least intimates, that a deliberate and premeditated plan had achieved its desired effect of sending Germany back to the Stone Age. This plan, codenamed Operation Gomorrah, which was at the time the heaviest aerial assault ever undertaken, was later called “Germany’s Hiroshima” by British Bomber Command. Reel after reel offers shocking images: black-and white photo montages of the chaff-filled skies and the abhorrent results of the merciless firebombing that had raised a four-hundred-and-sixty-meter scorching-hot tornado that reached temperatures of up to eight hundred degrees Celsius, and swept over twenty-one square kilometers of the city. Carried out by Lancaster, Wellington, Stirling, and Halifax aircraft, their blockbuster bombs turned asphalt streets into rivers of flame, asphyxiating young and old alike in a sea of carbon monoxide, and as one eyewitness later recalled, it “sucked people like dry leaves into its molten heart.”

Cinematographer Franz Lustig’s opening scenes confront even the most unsuspecting and ill-informed audience with the sight of an almost obliterated Hamburg filled with crumbling buildings. Raw footage shows, or at least intimates, that a deliberate and premeditated plan had achieved its desired effect of sending Germany back to the Stone Age. This plan, codenamed Operation Gomorrah, which was at the time the heaviest aerial assault ever undertaken, was later called “Germany’s Hiroshima” by British Bomber Command. Reel after reel offers shocking images: black-and white photo montages of the chaff-filled skies and the abhorrent results of the merciless firebombing that had raised a four-hundred-and-sixty-meter scorching-hot tornado that reached temperatures of up to eight hundred degrees Celsius, and swept over twenty-one square kilometers of the city. Carried out by Lancaster, Wellington, Stirling, and Halifax aircraft, their blockbuster bombs turned asphalt streets into rivers of flame, asphyxiating young and old alike in a sea of carbon monoxide, and as one eyewitness later recalled, it “sucked people like dry leaves into its molten heart.” Stefan Lubert (Alexander Skarsgard), a widower, and his daughter Freda (Flora Thiemann), are the people whose palatial home Rachael has in effect invaded when it is requisitioned by the occupying forces to billet the Morgans. Rachael insists, “I want them out!”, which means in effect expelling them to the refugee camps. She also asks them difficult questions about a certain portrait that had only recently been removed from a place of honor over their fireplace and hurriedly replaced by another painting. These are petty acts of spiteful sadism that were no doubt common practice and openly endorsed by the non-fraternization code at that time, but in the context of the film’s narrative clearly signals more about Rachael’s own insecurities than it does about any misdemeanors or malicious intent on the part of those in whose home she resides.

Stefan Lubert (Alexander Skarsgard), a widower, and his daughter Freda (Flora Thiemann), are the people whose palatial home Rachael has in effect invaded when it is requisitioned by the occupying forces to billet the Morgans. Rachael insists, “I want them out!”, which means in effect expelling them to the refugee camps. She also asks them difficult questions about a certain portrait that had only recently been removed from a place of honor over their fireplace and hurriedly replaced by another painting. These are petty acts of spiteful sadism that were no doubt common practice and openly endorsed by the non-fraternization code at that time, but in the context of the film’s narrative clearly signals more about Rachael’s own insecurities than it does about any misdemeanors or malicious intent on the part of those in whose home she resides.

En revoyant le ghost writer de Polanski, j’ai compris pourquoi ce maître impertinent avait connu tant de problèmes avec la justice américaine. Il y est fait mention des conspirations anglo-saxonnes à travers le monde, du comportement de Tony Blair, des guerres médio-orientales de Bush, ainsi que du train de vie oligarque des hommes politiques postmodernes (« à moi la belle vie », comme disait Sarkozy). Et il est facile de voir dans l’œuvre de Polanski une récurrence : la critique radicale des élites – voyez Tess, le bal des vampires, ou bien sûr le grand classique Chinatown. On rajoutera le Couteau dans l’eau, qui dénonçait audacieusement la nouvelle bourgeoisie communiste et on n’oubliera pas le bébé de Rosemary, dont j’avais souligné le contenu subversif dans ma Damnation des stars publiée en 1996 chez Filipacchi.

En revoyant le ghost writer de Polanski, j’ai compris pourquoi ce maître impertinent avait connu tant de problèmes avec la justice américaine. Il y est fait mention des conspirations anglo-saxonnes à travers le monde, du comportement de Tony Blair, des guerres médio-orientales de Bush, ainsi que du train de vie oligarque des hommes politiques postmodernes (« à moi la belle vie », comme disait Sarkozy). Et il est facile de voir dans l’œuvre de Polanski une récurrence : la critique radicale des élites – voyez Tess, le bal des vampires, ou bien sûr le grand classique Chinatown. On rajoutera le Couteau dans l’eau, qui dénonçait audacieusement la nouvelle bourgeoisie communiste et on n’oubliera pas le bébé de Rosemary, dont j’avais souligné le contenu subversif dans ma Damnation des stars publiée en 1996 chez Filipacchi.

« Ziegler pourrait jouer lui au contraire un rôle d’élite cosmopolite et rigolarde, aimable et protectrice (à la manière de certains hiérarques socialistes ?). Dans sa manière de traiter Bill paternellement, il nous rappelle ce mot d’esprit cité par Freud à propos d’un petit-bourgeois qui se croyait ami de Rothschild :

« Ziegler pourrait jouer lui au contraire un rôle d’élite cosmopolite et rigolarde, aimable et protectrice (à la manière de certains hiérarques socialistes ?). Dans sa manière de traiter Bill paternellement, il nous rappelle ce mot d’esprit cité par Freud à propos d’un petit-bourgeois qui se croyait ami de Rothschild :

The film does not fall short of its epic ambitions, and its success is a testament to Gibson’s vision and his technical mastery as a filmmaker. Even his many enemies have to admit that he is one of the most talented directors alive today.

The film does not fall short of its epic ambitions, and its success is a testament to Gibson’s vision and his technical mastery as a filmmaker. Even his many enemies have to admit that he is one of the most talented directors alive today.

Un jour, leur victime est un ancien militaire ayant servi dans la Légion étrangère et ayant fait la guerre d’Algérie. Henri, « le capitaine », refuse de baisser les yeux comme le lui ordonne un complice de David. C’est là l’acte fondateur de ce qui, petit à petit, provoquera chez David une admiration, voire une fascination, pour cet homme âgé dont la vie consiste à défendre des valeurs fort éloignées de son monde à lui en même temps que l’honneur et la mémoire de ses anciens soldats.

Un jour, leur victime est un ancien militaire ayant servi dans la Légion étrangère et ayant fait la guerre d’Algérie. Henri, « le capitaine », refuse de baisser les yeux comme le lui ordonne un complice de David. C’est là l’acte fondateur de ce qui, petit à petit, provoquera chez David une admiration, voire une fascination, pour cet homme âgé dont la vie consiste à défendre des valeurs fort éloignées de son monde à lui en même temps que l’honneur et la mémoire de ses anciens soldats. Henri, lui, c’est André Thiéblemont, un véritable ancien officier de Légion. Dans le film, c’est un taiseux et ses silences sont souvent plus évocateurs que ses rares paroles. Ses yeux bleus parlent pour lui, mais c’est avant tout une « gueule » impressionnante et dont la vérité crue des expressions nous émeut.

Henri, lui, c’est André Thiéblemont, un véritable ancien officier de Légion. Dans le film, c’est un taiseux et ses silences sont souvent plus évocateurs que ses rares paroles. Ses yeux bleus parlent pour lui, mais c’est avant tout une « gueule » impressionnante et dont la vérité crue des expressions nous émeut.

« On peut dire que dans la ville où je suis né (22 février 1900) le Moyen Age a duré jusqu'à la Première Guerre mondiale. C'était une société isolée et immobile, dans laquelle les différences de classe étaient bien marquées. Le respect et la subordination des travailleurs aux grands seigneurs, aux propriétaires terriens, profondément enracinés dans les vieilles coutumes, semblaient immuables. La vie se développa, horizontale et monotone, définitivement ordonnée et dirigée par les cloches de l'église d'El Pilar. »

« On peut dire que dans la ville où je suis né (22 février 1900) le Moyen Age a duré jusqu'à la Première Guerre mondiale. C'était une société isolée et immobile, dans laquelle les différences de classe étaient bien marquées. Le respect et la subordination des travailleurs aux grands seigneurs, aux propriétaires terriens, profondément enracinés dans les vieilles coutumes, semblaient immuables. La vie se développa, horizontale et monotone, définitivement ordonnée et dirigée par les cloches de l'église d'El Pilar. » Comme Samuel Beckett alors (« nous sommes tous cons, mais pas au point de voyager », voyez mon Voyageur éveillé ou mon apocalypse touristique), Buñuel envoie digne promener le tourisme :

Comme Samuel Beckett alors (« nous sommes tous cons, mais pas au point de voyager », voyez mon Voyageur éveillé ou mon apocalypse touristique), Buñuel envoie digne promener le tourisme :

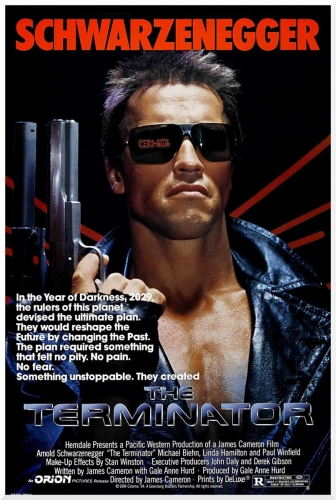

La guerre contre la machine...

La guerre contre la machine...

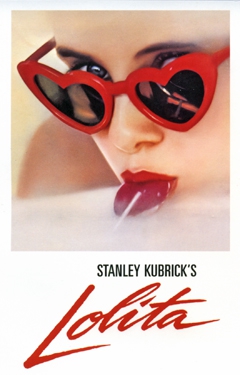

Il tournera alors cinq films piliers en un peu plus de dix ans : Lolita en 1962, Docteur Folamour en 1963, 2001 : L’Odyssée de l’Espace en 1968, Orange Mécanique en 1971 et Barry Lyndon en 1975. Au plus haut de sa carrière, il est reconnu dès 1971 comme l’un des plus grands réalisateurs de septième art. A la sortie du scandaleux Orange Mécanique, il sera menacé de mort en Angleterre, accusé d’incitation au meurtre. Kubrick exige alors de Warner Bros que le film soit retiré de la circulation. A partir de 1975 Stanley Kubrick devient de plus en plus perfectionniste jusqu’à friser l’internement : les tournages deviennent plus longs et le rythme de sortie des films diminue ; bénéficiant d’un statut exceptionnel dans le monde du cinéma. Demeurant un artiste indépendant avec une liberté quasi totale tout en bénéficiant de la puissance financière d’Hollywood pour réaliser et promouvoir ses créations.

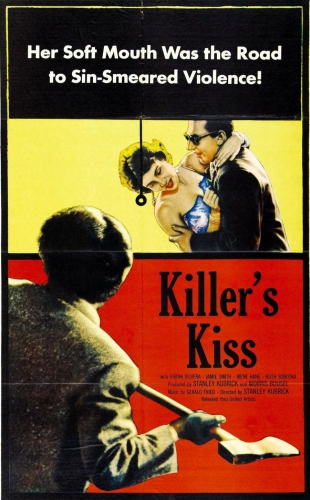

Il tournera alors cinq films piliers en un peu plus de dix ans : Lolita en 1962, Docteur Folamour en 1963, 2001 : L’Odyssée de l’Espace en 1968, Orange Mécanique en 1971 et Barry Lyndon en 1975. Au plus haut de sa carrière, il est reconnu dès 1971 comme l’un des plus grands réalisateurs de septième art. A la sortie du scandaleux Orange Mécanique, il sera menacé de mort en Angleterre, accusé d’incitation au meurtre. Kubrick exige alors de Warner Bros que le film soit retiré de la circulation. A partir de 1975 Stanley Kubrick devient de plus en plus perfectionniste jusqu’à friser l’internement : les tournages deviennent plus longs et le rythme de sortie des films diminue ; bénéficiant d’un statut exceptionnel dans le monde du cinéma. Demeurant un artiste indépendant avec une liberté quasi totale tout en bénéficiant de la puissance financière d’Hollywood pour réaliser et promouvoir ses créations. Le Baiser du tueur (killer’s kiss, 1955) : Film annonciateur de la Nouvelle Vague par sa forme, ce deuxième long métrage est un film noir tout comme le premier réalisé avec très peu de moyens. Kubrick y assurant seul les principales fonctions et à l’origine de l’histoire…Un boxeur au bout du rouleau (la scène du combat dans Le Baiser du tueur démontre déjà une certaine jouissance à filmer magistralement la violence) vient en aide à une voisine, tombe amoureux d’elle et se retrouve malgré lui mêlé à une sale affaire mêlant désir et de jalousie.

Le Baiser du tueur (killer’s kiss, 1955) : Film annonciateur de la Nouvelle Vague par sa forme, ce deuxième long métrage est un film noir tout comme le premier réalisé avec très peu de moyens. Kubrick y assurant seul les principales fonctions et à l’origine de l’histoire…Un boxeur au bout du rouleau (la scène du combat dans Le Baiser du tueur démontre déjà une certaine jouissance à filmer magistralement la violence) vient en aide à une voisine, tombe amoureux d’elle et se retrouve malgré lui mêlé à une sale affaire mêlant désir et de jalousie.

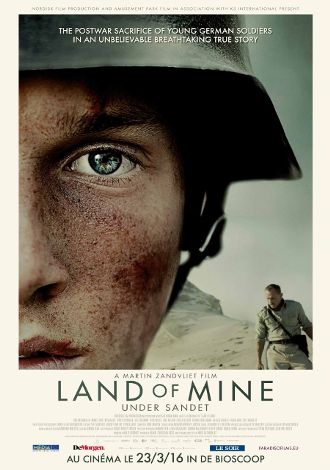

Directed by Martin Zandvliet, Land of Mine is the Danish entry for Best Foreign Film in the upcoming Academy Awards. I despise the Oscars, but even I might take a peek to see if it wins. Nordisk Film claims their standard for Oscar entries is that it must be cinema with high cultural value to the Nordic countries, and in this effort they certainly succeeded. It is one of the most moving war dramas I’ve seen.

Directed by Martin Zandvliet, Land of Mine is the Danish entry for Best Foreign Film in the upcoming Academy Awards. I despise the Oscars, but even I might take a peek to see if it wins. Nordisk Film claims their standard for Oscar entries is that it must be cinema with high cultural value to the Nordic countries, and in this effort they certainly succeeded. It is one of the most moving war dramas I’ve seen.