Immigration: la prochaine étape du libéralisme

Enric Ravello Barber

Source: https://euro-sinergias.blogspot.com/2022/12/normal-0-21-false-false-false-es-x-none_26.html

Dialectiquement, on a tendance à établir une relation de cause à effet entre la colonisation de la fin du 19ème siècle et l'immigration massive subie par l'Europe depuis le milieu du 20ème siècle. Le parallélisme n'est pas tout à fait correct, mais il existe des symptômes et des caractéristiques communs aux deux processus, bénéfiques au grand capital, complétés par la destruction des identités et des équilibres économiques sur toute la planète.

Sans aucun doute, la colonisation et l'immigration sont toutes deux des phénomènes pernicieux qui obéissent à la même logique mondialiste et à la même justification idéologique libérale-marxiste.

L'impérialisme et le capitalisme financier

En 1916, Vladimir Illich, dit Lénine, a publié un ouvrage considéré comme clé dans l'évolution de l'analyse marxiste du capitalisme. C'était l'époque où Lénine combinait son activité de révolutionnaire avec celle de théoricien, ce qui le distinguait d'autres dirigeants comme Trotski ou Staline. Le titre de l'ouvrage auquel nous nous référons est révélateur : L'impérialisme, le stade le plus élevé du capitalisme. La thèse centrale de ce livre, erronée comme tant de thèses de cette école de pensée, consiste à affirmer que le capitalisme libre-échangiste du milieu du 19ème siècle avait terminé sa phase libre-échangiste - le marxisme avait une véritable obsession pour les "phases" - et qu'il cédait la place à une nouvelle phase - la phase supérieure - qui serait caractérisée par la concentration du capital industriel et la concentration des élites économiques à la tête de l'État. L'État en tant qu'agent économique devrait conquérir de nouveaux espaces - une fois le marché "national" épuisé - pour s'approprier les matières premières et exporter ses produits de manière monopolistique (d'où l'idée de la fin du libre-échange). Pour Lénine, le capitalisme aurait pu muter du libre-échange au protectionnisme et à l'économie impérialiste sans être affecté dans son essence.

Comme toutes les utopies absurdes déguisées en méthode scientifique, les analyses de Lénine ont été réfutées par la réalité, le socialisme marxiste, le réel et le non-réel, ayant explosé en 1991. Aujourd'hui, la gauche a abandonné les vieux dogmes du soi-disant "matérialisme historique" et ne veut plus se souvenir de Lénine, ni des phases du capitalisme, ni d'autres lourds fardeaux maintenant qu'elle est devenue éco-pacifiste et sentimentalo-mondialiste.

Néanmoins, et c'est pourquoi nous avons sauvé l'œuvre de Lénine de l'oubli, l'auteur a mis en évidence une conjonction de phénomènes qui, mutatis mutandis, peuvent être mis en parallèle avec le processus actuel du capitalisme libéral.

1.1. Débat sur les causes de l'impérialisme. L'évaluation marxiste du colonialisme

Les théories sur la nature du phénomène impérialiste sont apparues pratiquement en même temps que l'expansion coloniale. De manière générale, il faut distinguer deux types de théories: les eurocentriques et les périphériques; pour la première, l'explication de l'expansion se trouve dans les causes internes des pays européens; pour la seconde, la dynamique des pays colonisés eux-mêmes a favorisé et encouragé ce phénomène. La combinaison des deux facteurs nous donnerait sûrement une réponse plus complète.

Les théories eurocentriques ne sont pas uniformes ou unilatérales ; dans leur explication, nous pouvons déterminer deux types : celles qui soulignent les besoins économiques européens comme moteur du colonialisme et celles qui désignent les facteurs politiques comme vecteur déterminant.

Parmi ceux qui donnent une explication économiste, nous pouvons signaler ceux du radical-libéral britannique Hobson, qui dès 1902 soulignait que le Royaume-Uni avait besoin d'une expansion mondiale qui le consoliderait en tant que première puissance mondiale productive et commerciale, expliquant l'impérialisme comme une simple activité financière dans laquelle les dépenses militaires provoquées par les guerres d'expansion seraient toujours inférieures aux bénéfices industriels et commerciaux ultérieurs. Pourtant, il a utilisé cet argument pour justifier l'intervention britannique en Afrique du Sud, une intervention qui a conduit au génocide des Boers.

Très intéressante dans ce fil explicatif est la contribution de l'historien marxiste autrichien Hilferding, qui - suivant l'exemple de Lénine - dans son ouvrage Finanzkapital - Capitalisme financier (1910) élabore une théorie selon laquelle l'impérialisme est la réponse expansive du capitalisme lorsqu'il se transforme de capitalisme industriel en capitalisme financier, Il appelle capitalisme financier le moment où le capitalisme tend vers l'accumulation et la concentration de l'argent, au moment même où une synergie s'établit entre le capitalisme industriel et le capitalisme financier sous l'hégémonie de ce dernier. Selon Hilferding, l'étape du capitalisme financier commence à la fin du 19ème siècle, car la finance, à travers l'utilisation du crédit, accélère les processus oligarchiques de concentration des entreprises, détruisant le tissu des petits et moyens entrepreneurs en fermant le crédit (un phénomène qui se répète aujourd'hui) ; de cette façon, la symbiose du capitalisme financier et des grandes entreprises évite la concurrence. Dans un premier temps, elle monopolise le marché intérieur national, et dans un second temps, elle adopte un ton expansif, se tournant vers l'extérieur à la recherche de nouveaux marchés pour ses produits, c'est-à-dire en donnant naissance à l'impérialisme colonialiste, qui ne serait que le résultat logique de la dynamique interne même du capitalisme dans sa phase financière.

Pour en revenir au livre de Lénine, le théoricien marxiste qui a le mieux étudié ce phénomène, sa thèse a également influencé la critique non marxiste du phénomène colonialiste. Comme l'indique le titre de son ouvrage, la thèse défendue est que l'impérialisme est la phase historique la plus élevée du capitalisme, une phase caractérisée par le monopole par opposition à la libre concurrence précédente. Ce passage de la concurrence entre petits et moyens entrepreneurs à celle du regroupement en grands consortiums industriels/financiers monopolistiques, qui n'auraient aucun débouché économique s'il n'y avait pas une expansion des marchés au-delà du cadre national étroit pour vendre leurs produits industriels et placer leur capital financier excédentaire accumulé, cette expansion monopolistique nécessaire était le colonialisme, que Lénine appelle impérialisme. Lénine a expliqué que l'expansion impérialiste était la dernière issue pour le capitalisme, et qu'une fois épuisée cette ressource basée sur l'expansion territoriale et l'élargissement des marchés, le capitalisme - puisque le monde est fini et la capacité à trouver de nouveaux marchés limitée - entrerait dans sa contradiction finale et finirait par disparaître, le capitalisme aurait donc en lui le germe de sa propre autodestruction irrémédiable. Une autre "prédiction de l'avenir du "matérialisme historique" dont l'histoire a rapidement prouvé qu'elle était fallacieuse.

Comme nous l'avons dit, il existe d'autres théories explicatives eurocentriques qui ne pointent pas les facteurs économiques comme explication de l'expansion coloniale, mais se réfèrent à des contextes idéologiques-sociologiques (causes subjectives, comme dirait un marxiste). Schumpeter, un autre libéral radical, a traditionnellement été considéré comme la principale référence de ce courant explicatif. En 1919, cet auteur a publié sa Sociologie de l'impérialisme, dans laquelle il affirme que derrière le phénomène impérialiste se cache une impulsion d'expansion in-historique (c'est-à-dire permanente) qui, combinée au 19ème siècle avec le nationalisme de masse, donnerait naissance à l'impulsion et à la justification impérialiste.

Cependant, dans les années 1970, une nouvelle explication a émergé au sein de l'école marxiste, dans laquelle l'impérialisme est expliqué en termes de dynamique de la périphérie, c'est-à-dire des pays colonisés, soit une dynamique propre aux tensions internes entre les couches sociales africaines, qui serait la véritable explication de l'impérialisme, et qui ne répondrait donc pas aux motifs intra-européens. Parmi les thèses périphériques, il convient de mentionner le travail de Robert et Galaher, qui rompt complètement avec la tendance unidirectionnelle à expliquer l'impérialisme, et impute le colonialisme, ainsi que le processus désastreux de décolonisation, aux pseudo-élites africaines, qui ne voulaient ou ne pouvaient pas organiser les excédents de production de manière à offrir des conditions économiques stables à leurs pays, et qui, n'étant pas capables de faire ce saut qualitatif, ont ouvert les portes aux Européens parce qu'ils le feraient pour eux. Il faut ajouter que, dans cette ouverture aux Européens des élites sociales africaines, ces élites ont pensé à leur enrichissement personnel et non à la prospérité de leurs peuples respectifs. Une situation qui se répète aujourd'hui "ad nauseam".

En bref, il est indéniable que l'impérialisme est le résultat d'une interaction entre deux variables, l'une européenne et l'autre périphérique.

1.2. Le colonialisme : une idée de la gauche

Contrairement à ce qu'il semble, et en dysfonctionnement avec le message adopté par la gauche à partir des années 1960, le colonialisme est une idée qui est née dans sa sphère idéologique et a toujours été valorisée comme "progressiste" dans son analyse linéaire et téléologique de l'histoire.

Karl Marx était l'un des apologistes de la colonisation britannique de l'Inde. Selon lui, la colonisation britannique signifierait le démantèlement du mode de production médiéval de l'économie autochtone et son remplacement par le mode de production capitaliste, ce qui signifierait "brûler une étape" jusqu'au modèle communiste, qui - selon le natif de Treves - était l'étape suivante nécessaire au modèle capitaliste par la simple logique de ses contradictions internes.

Ce n'est pas seulement dans la sphère strictement marxiste que cette évaluation positive du colonialisme a été faite. L'écrivain français Bernard Lugan, sans doute le plus grand spécialiste actuel de l'Afrique et du colonialisme - un auteur sur lequel nous devrons nécessairement revenir dans des articles ultérieurs - a publié un article intéressant dans le magazine NRH intitulé "Une idée de gauche réalisée par la droite" dans lequel il décrit comment le processus de colonisation de l'Afrique a été conçu par une gauche éclairée et progressiste qui voyait dans cette expansion géographique l'extension des principes universalistes de la révolution française sur le continent noir. La phrase du premier ministre socialiste français, Léon Blum, est très significative dans ce sens: "(Je proclame)... le droit et le devoir des races supérieures de la politique socialiste franco-juive d'attirer (vers le progrès) ceux qui n'ont pas encore atteint le même niveau culturel". Un bel exemple d'intégrationnisme mondialiste avant la lettre.

II. L'immigration entre l'après-guerre et la décolonisation

Le processus de décolonisation a marqué une nouvelle phase de l'histoire. L'Afrique était plongée dans un chaos absolu, la prétendue "libération" consistait en réalité en l'instauration de régimes tyranniques et despotiques dans tous les pays, et les conséquences n'ont pas tardé à suivre: la misère, la faim et une natalité débordante. D'autre part, en Europe occidentale, la fin de la Seconde Guerre mondiale et la reconstruction qui s'en est suivie ont marqué le début d'une nouvelle phase d'expansion du capitalisme, qui a vu ses taux de profit et sa capacité d'expansion monter en flèche. C'est pourquoi, sur le territoire où les profits sont les plus importants en ce moment - l'Europe occidentale - une augmentation constante de la main-d'œuvre est nécessaire pour ne pas gaspiller les conditions objectives de la croissance économique.

La conjonction de ces deux processus converge vers le début du processus migratoire du tiers monde vers l'Europe. Comme nous l'avons souligné précédemment pour l'impérialisme, dans ce cas aussi, l'immigration est le résultat d'une interaction entre deux variables, l'une européenne et l'autre périphérique-tertiaire-terroriste.

L'immigration se nourrit de la même conception idéologique que le colonialisme, dont elle n'est qu'une projection. L'augmentation de la part de profit du capital dans un monde devenu un marché unique, et dans lequel les identités, les coutumes et les peuples ne sont rien de plus que des interférences circonstancielles qui doivent être supprimées, annulées ou - dans le pire des cas - réduites à des anecdotes folkloriques.

Ainsi, l'immigration n'est qu'une des conséquences d'un processus plus large appelé mondialisation en français et globalisation en anglais, dont le but ultime se confond avec celui de l'impérialisme du 19ème siècle. Dans les deux processus, le bénéficiaire est la classe financière-capitaliste et le principal perdant est la communauté populaire de la classe ouvrière.

2.1. Le libéralisme en tant que principe idéologique de l'immigration. L'erreur de l'intégration

Au cours des dernières décennies, le phénomène de la migration est devenu une question cruciale dans le débat politique en Europe occidentale. Face à cette circonstance, nous assistons à un spectacle comique, un piège pour les imbéciles, qui - malheureusement - s'avère d'une certaine efficacité. Le fait est que le libéralisme, sans changer ses hypothèses idéologiques, tente d'apporter des "solutions" au problème de la migration, des solutions qui font partie du même principe universaliste et qui n'en sont donc pas. Nous les exposons ci-dessous afin que le mouvement identitaire évite ce type d'erreur idéologique et signale le libéralisme et n'importe lequel de ses postulats politiques comme étant véritablement contraire à nos positions.

Communautarisme : il s'agit de l'idée que les immigrants, en fonction de leur communauté d'origine, continuent à maintenir leurs propres spécificités culturelles et religieuses sur le sol européen, tout en participant - à partir de leur spécificité - à l'État et en son sein en tant que "citoyens". En d'autres termes, la citoyenneté serait comprise comme la simple obtention d'une carte d'identité, les immigrants n'auraient pas à "s'intégrer" mais à maintenir leur personnalité tant qu'ils respectent les "principes fondamentaux et le bon fonctionnement de l'État libéral-démocratique".

En fait, c'est l'idée du melting-pot qu'il a créé aux États-Unis d'Amérique. Elle est basée sur la "tolérance de l'autre". Il est synonyme d'un autre terme, celui de "multiculturalisme". Lorsque certains politiciens de l'establishment comme Angela Merkel ou Tony Blair disent que "le multiculturalisme a échoué", c'est précisément ce qu'ils veulent dire. Il est évident que le multiculturalisme a échoué, mais le pire est que Merkel ou Blair, en voyant cet échec évident, proposent l'autre "solution" libérale, tout aussi catastrophique, voire plus, que la précédente.

Intégration : que l'on pourrait aussi appeler "assimilationnisme". Elle consiste à atteindre la même fin, mais avec des méthodes différentes. Ainsi, les immigrants ne seraient pas respectés dans le maintien de leurs spécificités sur le sol européen, mais devraient "nécessairement" s'adapter et adopter nos coutumes, ce qui ferait d'eux des "Européens parfaitement intégrés".

Le communautarisme et l'assimilationnisme sont les deux faces de la même erreur idéologique.

III. La solution basée sur l'identité

Depuis notre position identitaire, nous devons répondre à la fois aux phénomènes de colonisation et à la menace démographique que représente l'immigration, mais toujours en partant de la solidité de nos paramètres idéologiques et de la rigueur d'une pensée anti-cosmopolite, qui valorise l'existence des peuples, qui s'oppose radicalement à l'idée du marché mondial et qui ne croit ni à l'assimilation ni aux conversions mais à la personnalité collective fondée sur le patrimoine et l'histoire.

Par opposition au colonialisme, les identitaires proposent l'idée de grands espaces économiques autosuffisants. Ces espaces sont définis par la communauté de la civilisation, de l'histoire et de la consanguinité.

Par opposition à l'intégration ou à l'assimilation, nous proposons l'idée que l'État est un instrument de la communauté populaire et l'expression d'une société mono-ethnique. C'était le sens de la démocratie grecque, qui ne comprenait pas la polis autrement, le sens du Sénat romain et des assemblées de guerriers germaniques. C'est le principe inaliénable que nous défendons aujourd'hui pour que la civilisation européenne puisse survivre aux menaces et aux vicissitudes posées par ce 21ème siècle inquiétant.

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

Rien de tout cela, cependant, n'est le fait de personnes dépensant volontairement l'argent qu'elles ont gagné en travaillant sur les produits de ces entreprises, mais tout est payé par de l'argent détourné par la contrainte de l'État aux dépens d'activités socialement importantes et/ou créatrices de valeur. L'immigration ne crée donc rien de valable, mais signifie au contraire que les fonds qui auraient dû être consacrés à des investissements dans l'avenir sont, premièrement, dépensés dans le présent, deuxièmement, utilisés d'une manière dont aucune personne honnête ne profitera et, troisièmement, dépensés dans des activités aux externalités négatives gigantesques. Les entrepreneurs qui opèrent dans le cadre de la vague d'immigration gagneront certainement beaucoup d'argent, mais pas en fournissant au marché un produit que les consommateurs ou les électeurs demandent, mais en remplissant les comptes bancaires de ces entrepreneurs avec l'argent des contribuables par ceux qui sont au pouvoir et qui ont tout sauf le bien public à l'esprit, en échange de leur travail de sape de la civilisation occidentale. Le fait que ces entrepreneurs soient constamment récompensés par des prix industriels et présentés comme de bons entrepreneurs™ devant un public ayant une connaissance très limitée de la théorie économique n'y change rien.

Rien de tout cela, cependant, n'est le fait de personnes dépensant volontairement l'argent qu'elles ont gagné en travaillant sur les produits de ces entreprises, mais tout est payé par de l'argent détourné par la contrainte de l'État aux dépens d'activités socialement importantes et/ou créatrices de valeur. L'immigration ne crée donc rien de valable, mais signifie au contraire que les fonds qui auraient dû être consacrés à des investissements dans l'avenir sont, premièrement, dépensés dans le présent, deuxièmement, utilisés d'une manière dont aucune personne honnête ne profitera et, troisièmement, dépensés dans des activités aux externalités négatives gigantesques. Les entrepreneurs qui opèrent dans le cadre de la vague d'immigration gagneront certainement beaucoup d'argent, mais pas en fournissant au marché un produit que les consommateurs ou les électeurs demandent, mais en remplissant les comptes bancaires de ces entrepreneurs avec l'argent des contribuables par ceux qui sont au pouvoir et qui ont tout sauf le bien public à l'esprit, en échange de leur travail de sape de la civilisation occidentale. Le fait que ces entrepreneurs soient constamment récompensés par des prix industriels et présentés comme de bons entrepreneurs™ devant un public ayant une connaissance très limitée de la théorie économique n'y change rien.

L’effet sur les logements est potentiellement plus important. L’immigration accroît la pression sur le parc de logements, mettant les familles immigrées en compétition avec les familles autochtones dans le logement social, avec un phénomène d’éviction si les premières sont les plus pauvres, mais aussi dans le logement privé. À Londres, si l’immigration a accru les opportunités des entreprises, elle a réduit la mobilité des autochtones qui ont du mal à s’y installer alors que les opportunités d’emploi y sont meilleures.

L’effet sur les logements est potentiellement plus important. L’immigration accroît la pression sur le parc de logements, mettant les familles immigrées en compétition avec les familles autochtones dans le logement social, avec un phénomène d’éviction si les premières sont les plus pauvres, mais aussi dans le logement privé. À Londres, si l’immigration a accru les opportunités des entreprises, elle a réduit la mobilité des autochtones qui ont du mal à s’y installer alors que les opportunités d’emploi y sont meilleures.

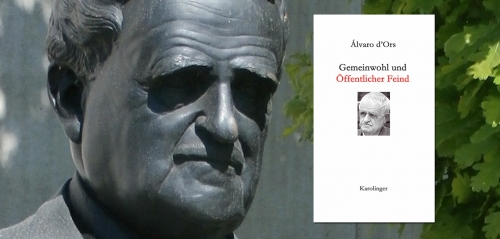

Der spanische Rechtsgelehrte Álvaro d’Ors sieht im Migranten den öffentlichen Feind, dessen Invasion verhindert werden muss. Eine Rezension des Buches Gemeinwohl und Öffentlicher Feind von Gereon Breuer.

Dem Dominikanerpater Wolfgang Hariolf Spindler, der als versierter Kenner Carl Schmitts gilt, ist es zu verdanken, dass die Schrift Gemeinwohl und Öffentlicher Feind von Álvaro d’Ors endlich auf Deutsch vorliegt. Carl Schmitt und sein Denken bilden dabei in zweifacher Weise den Schnittpunkt, der das Werk nicht nur für Spindler interessant macht. Den 2004 verstorbenen Ordinarius für Römisches Recht an der Universität Navarra verband eine lebenslange, kritische Freundschaft mit dem Plettenberger Titanen. Diese hat sein Denken insbesondere im Hinblick auf den Feind als politische Kategorie maßgeblich geprägt.

So ist auch für d’Ors die Bestimmung des Feindes eine relative Angelegenheit. Der Feind ist für ihn immer der „Feind einer bestimmten Gruppe“. Seine Bestimmung sieht er deshalb auf das Engste mit dem Mehrheitsprinzip verknüpft. Weil diese Art der Feindbestimmung öffentlich ist, handelt es sich bei dem Feind um einen öffentlichen Feind. Für d’Ors wie für Schmitt bedeutet dies, dass sich die Feindschaft immer gegen eine bestimmte Gruppe richten muss.

Feindschaft bedarf der Erklärung

Als Voraussetzung für die öffentliche Feindschaft nennt d’Ors ihre Erklärung. Das bedeutet, dass die Gruppe, gegen die sich die Feindschaft richtet, auch von dieser Feindschaft wissen muss. In ihrer schärfsten Form ist die Erklärung der Feindschaft die Kriegserklärung, die sich aber d’Ors zufolge auch gegen die inneren Feinde richten kann. Das Potential der öffentlichen Feindschaft zeigt sich daher auch in der Verächtlichmachung bestimmter Gruppen, deren Meinung als unerwünscht angesehen wird.

D’Ors weist darauf hin, dass in antiker Zeit die formale Erklärung der Feindschaft nötig war, um einen Krieg beginnen zu können, für dessen Gewalthandlungen dann das Kriegsrecht galt. Das bedeutet: Ist die Feindschaft einmal erklärt, rechtfertigt dies auch die Vernichtung des Feindes. In diesem Sinne wird die soziale Vernichtung eines inneren Feindes aufgrund einer unerwünschten Meinung als Verteidigungshandlung legitimiert. Das ist deshalb besonders perfide, weil es sich bei der Erklärung der Feindschaft um eine Mehrheitsentscheidung handelt, durch die eine bestimmte Gruppe als öffentlicher Feind kriminalisiert wird.

Mehrheitsprinzip als Prinzip vernunftloser Geschöpfe

Ganz unabhängig von ihrem Inhalt haben Mehrheitsentscheidungen im Sinne von d’Ors einen mindestens problematischen Charakter. Er sieht im Mehrheitsprinzip das Prinzip der vernunftlosen Geschöpfe verwirklicht. Dadurch werde alles zu einer relativen Angelegenheit – nicht nur die Bestimmung des Feindes. D’Ors sieht hier einen Gegenpol nicht nur zur Vernunft, sondern auch zur Verantwortung. Zwar bringe „die Mehrheitsentscheidung die Option des freien Willens einer menschlichen Gruppe zum Ausdruck, nicht jedoch die Erfolgsgarantie ihrer Verantwortung“.

Das bedeutet, dass Mehrheitsentscheidungen keine verantwortbaren Entscheidungen sind und sie deshalb auch kein verantwortliches Handeln begründen können. Die Mehrheit ist eben kein Einzelner, der für eine Entscheidung zur Rechenschaft gezogen werden kann, sondern eine Masse undefinierbarer Verantwortlichkeiten. Aus diesem Grund empfindet d’Ors demokratische Entscheidungen als ungerecht und weil er den Kampf gegen sie als aussichtslos betrachtet, „bleibt außer der Enthaltung keine vernünftige Gegenwehr“.

Gemeinwohl und Naturrecht

Den Bereich des Gemeinwohls will d’Ors aus diesem Grund von den ungerechten Entscheidungen verschont wissen. Das Gemeinwohl ist für ihn das, „was mit dem natürlichen Gesetz übereinstimmt […] und nicht eine Reihe von ethischen Prinzipien, die aufgrund menschlicher Übereinkunft aufgestellt wurden […].“ Dieses natürliche Gesetz oder Naturrecht ist aus dem weltlichen Recht im Gegensatz zum kanonischen Recht längst verschwunden. Seinen Platz hat der Positivismus eingenommen, demzufolge alles als Recht gelten kann, was als Recht gesetzt wurde.

Carl Schmitt erkennt im Staat als geschichtsnotwendigem Produkt die wesentliche Institution der Rechtssetzung. Demgegenüber stellt der Staat für d’Ors etwas grundsätzlich Überflüssiges dar und ist für ihn kaum mehr als eine „säkularistische Fehlentwicklung“. Dementsprechend schreibt er auch in einem Brief an Schmitt vom 3. Oktober 1962, dass „die katholische Soziallehre mit der Idee des ‚Staates’ im eigentlichen Sinn unvereinbar ist“. Für das Gemeinwohl ist der Staat im Sinne d’Ors deshalb auch nicht zuständig, sondern es obliege der Gemeinschaft, die Übereinstimmung des Gemeinwohls mit dem natürlichen Gesetz zu sichern.

Masseneinwanderung ist Invasion

Die Immigration stellt für d’Ors dann einen Verstoß gegen das Naturrecht dar, wenn sie massenhaft geschieht. Zwar müsse sich der Mensch frei bewegen können, aber dabei handele es sich um eine individuelle Freiheit, die nicht auf eine ganze Gruppe übertragen werden könne. Daher stelle „der massenhafte Transfer von Menschen aus ihrem eigenen Territorium in ein fremdes“ eine Invasion dar. Vor dem Hintergrund eines naturrechtlich begründeten Gemeinwohls sei der Widerstand gegen eine solche Invasion zu seinem Schutz dann auch eine legitime Angelegenheit. Eine Gemeinschaft könne „die Immigration in ihr Territorium mit vorbeugenden Maßnahmen in zulässiger Weise verhindern, sie darf aber nicht versuchen, sich von der bereits erfolgten Immigration zu reinigen; denn ihre frühere Identität hat sie tatsächlich schon verloren“.

Ein Migrant ist deshalb so lange ein öffentlicher Feind, wie er sich als Angehöriger einer Gruppe außerhalb des eigenen Territoriums befindet. Die Feindschaft wird dabei durch eine Sicherung der Grenzen erklärt. Alle Probleme, die im Zusammenhang mit der Masseneinwanderung in einem Land einhergehen, beruhen daher auf der Unterlassung der Feinderklärung. Sie kann das Gemeinwohl letztlich nur schützen, wenn sie zum richtigen Zeitpunkt erfolgt und die Invasion wirksam verhindert.

Alvaro d’Ors (2015): Gemeinwohl und Öffentlicher Feind. Wien: Karolinger Verlag. 130 Seiten. 19,90 Euro.

Bildhintergrund: Álvaro d’Ors-Statue, fotographiert von: Jeremyah1983, CC BY-SA 4.0

Dieser Beitrag erschien zuerst auf unserem Blog Einwanderungskritik.de.