La tradition dont les vérités signifiantes et créatives sont affirmées par ces traditionalistes contre l’assaut nihiliste de la modernité n’est pas le concept anthropologique et sociologique dominant, défini comme « un ensemble de pratiques sociales inculquant certaines normes comportementales impliquant une continuité avec un passé réel ou imaginaire ». Ce n’est pas non plus la « démocratie des morts » de G. K. Chesterton, ni la « banque générale et le capital des nations et des âges » d’Edmund Burke. Pour eux la tradition n’avait pas grand-chose à voir avec le passé comme tel, des pratiques culturelles formalisées, ou même le traditionalisme. Venner, par exemple, la compare à un motif musical, un thème guidant, qui fournit une cohérence et une direction aux divers mouvements de la vie.

Si la plupart des traditionalistes s’accordent à voir la tradition comme orientant et transcendant à la fois l’existence collective d’un peuple, représentant quelque chose d’immuable qui renaît perpétuellement dans son expérience du temps, sur d’autres questions ils tendent à être en désaccord. Comme cas d’école, les traditionalistes radicaux associés à TYR s’opposent aux « principes abstraits mais absolus » que l’école guénonienne associe à la « Tradition » et préfèrent privilégier l’héritage européen [3]. Ici l’implication (en-dehors de ce qu’elle implique pour la biopolitique) est qu’il n’existe pas de Tradition Eternelle ou de Vérité Universelle, dont les vérités éternelles s’appliqueraient partout et à tous les peuples – seulement des traditions différentes, liées à des peuples différents dans des époques et des régions culturelles différentes. Les traditions spécifiques de ces histoires et cultures incarnent, comme telles, les significations collectives qui définissent, situent et orientent un peuple, lui permettant de triompher des défis incessant qui lui sont spécifiques. Comme l’écrit M. Raphael Johnson, la tradition est « quelque chose de similaire au concept d’ethnicité, c’est-à-dire un ensemble de normes et de significations tacites qui se sont développées à partir de la lutte pour la survie d’un peuple ». En-dehors du contexte spécifique de cette lutte, il n’y a pas de tradition [4].

Mais si puissante qu’elle soit, cette position « culturaliste » prive cependant les traditionalistes radicaux des élégants postulats philosophiques et principes monistes étayant l’école guénonienne. Non seulement leur projet de culture intégrale enracinée dans l’héritage européen perd ainsi la cohésion intellectuelle des guénoniens, mais il risque aussi de devenir un pot-pourri d’éléments disparates, manquant de ces « vues » philosophiques éclairées qui pourraient ordonner et éclairer la tradition dont ils se réclament. Cela ne veut pas dire que la révolte de la tradition contre le monde moderne doive être menée d’une manière philosophique, ou que la renaissance de la tradition dépende d’une formulation philosophique spécifique. Rien d’aussi utilitaire ou utopique n’est impliqué, car la philosophie ne crée jamais – du moins jamais directement – « les mécanismes et les opportunités qui amènent un état de choses historique » [5]. De telles « vues » fournissent plutôt une ouverture au monde – dans ce cas, le monde perdu de la tradition – montrant la voie vers ces perspectives que les traditionalistes radicaux espèrent retrouver.

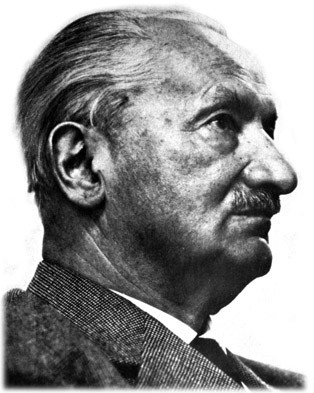

Je crois que la pensée de Martin Heidegger offre une telle vision. Dans les pages qui suivent, nous défendrons une appropriation traditionaliste de la pensée heideggérienne. Les guénoniens sont ici pris comme un repoussoir vis-à-vis de Heidegger non seulement parce que leur approche métaphysique s’oppose à l’approche historique européenne associée à TYR, mais aussi parce que leur discours possède en partie la rigueur et la profondeur de Heidegger. René Guénon représente cependant un problème, car il fut un apostat musulman de la tradition européenne, désirant « orientaliser » l’Occident. Cela fait de lui un interlocuteur inapproprié pour les traditionalistes radicaux, particulièrement en comparaison avec son compagnon traditionaliste Julius Evola, qui fut l’un des grands champions contemporains de l’héritage « aryen ». Parmi les éternalistes, c’est alors Evola plutôt que Guénon qui offre le repoussoir le plus approprié à Heidegger [6].

Le Naturel et le Surnaturel

Etant donné les fondations métaphysiques des guénoniens, le Traditionalisme d’Evola se concentrait non sur « l’alternance éphémère des choses données aux sens », mais sur « l’ordre éternel des choses » situé « au-dessus » d’elles. Pour lui Tradition signifie la « sagesse éternelle, la philosophia perennis, la Vérité Primordiale » inscrite dans ce domaine supra-humain, dont les principes éternels, immuables et universels étaient connus, dit-on, des premiers hommes et dont le patrimoine (bien que négligé) est aujourd’hui celui de toute l’humanité [7].

La « méthode traditionaliste » d’Evola vise ainsi à recouvrer l’unité perdue dans la multiplicité des choses du monde. De ce fait il se préoccupe moins de la réalité empirique, historique ou existentielle (comprise comme un reflet déformé de quelque chose de supérieur) que de l’esprit – tel qu’on le trouve, par exemple, dans le symbole, le mythe et le rituel. Le monde humain, par contre, ne possède qu’un ordre d’importance secondaire pour lui. Comme Platon, il voit son domaine visible comme un reflet imparfait d’un domaine invisible supérieur. « Rien n’existe ici-bas », écrit-il, « …qui ne s’enracine pas dans une réalité plus profonde, numineuse. Toute cause visible n’est qu’apparente » [8]. Il refuse ainsi toutes les explications historiques ou naturalistes concernant le monde contingent de l’homme.

Voyant la Tradition comme une « présence » transmettant les vérités transcendantes obscurcies par le tourbillon éphémère des apparences terrestres, Evola identifie l’Etre à ses vérités immuables. Dans cette conception, l’Etre est à la fois en-dehors et au-delà du cours de l’histoire (c’est-à-dire qu’il est supra-historique), alors que le monde humain du Devenir est associé à un flux toujours changeant et finalement insensé de vie terrestre de sensations. La « valeur suprême et les principes fondateurs de toute institution saine et normale sont par conséquent invariables, étant basés sur l’Etre » [9]. C’est de ce principe que vient la doctrine évolienne des « deux natures » (la naturelle et la surnaturelle), qui désigne un ordre physique associé au monde du Devenir connu de l’homme et un autre ordre qui décrit le royaume métaphysique inconditionné de l’Etre connu des dieux.

Les civilisations traditionnelles, affirme Evola, reflétaient les principes transcendants transmis dans la Tradition, alors que le royaume « anormal et régressif » de l’homme moderne n’est qu’un vestige décadent de son ordre céleste. Le monde temporel et historique du Devenir, pour cette raison, est relégué à un ordre d’importance inférieur, alors que l’unité éternelle de l’Etre est privilégiée. Comme son « autre maître » Joseph de Maistre, Evola voit la Tradition comme antérieure à l’histoire, non conditionnée par le temps ou les circonstances, et donc sans lien avec les origines humaines » [10]. La primauté qu’il attribue au domaine métaphysique est en effet ce qui le conduit à affirmer que sans la loi éternelle de l’Etre transmise dans la Tradition, « toute autorité est frauduleuse, toute loi est injuste et barbare, toute institution est vaine et éphémère » [11].

La Tradition comme Überlieferung

Heidegger suit la voie opposée. Eduqué pour une vocation dans l’Eglise catholique et fidèle aux coutumes enracinées et provinciales de sa Souabe natale, lui aussi s’orienta vers « l’ancienne transcendance et non la mondanité moderne ». Mais son anti-modernisme s’opposait à la tradition de la pensée métaphysique occidentale et, par implication, à la philosophie guénonienne de la Tradition (qu’il ne connaissait apparemment pas).

La métaphysique est cette branche de la philosophie qui traite des questions ontologiques majeures, la plus fondamentale étant la question : Qu’est-ce que l’Etre ? Commençant avec Aristote, la métaphysique tendit néanmoins à s’orienter vers la facette non-physique et non-terrestre de l’Etre, tentant de saisir la transcendance de différents êtres comme l’esprit, la force, ou l’essence [12]. En recourant à des catégories aussi généralisées, cette tendance postule un royaume transcendant de formes permanentes et de vérités inconditionnées qui comprennent l’Etre d’une manière qui, d’après Heidegger, limite la compréhension humaine de sa vérité, empêchant la manifestation d’une présence à la fois cachée, ouverte et fuyante. Dans une formulation opaque mais cependant révélatrice, Heidegger écrit : « Quand la vérité [devient une incontestable] certitude, alors tout ce qui est vraiment réel doit se présenter comme réel pour l’être réel qu’il est [supposément] » – c’est-à-dire que quand la métaphysique postule ses vérités, pour elle la vérité doit se présenter non seulement d’une manière autoréférentielle, mais aussi d’une manière qui se conforme à une idée préconçue d’elle-même » [13]. Ici la différence entre la vérité métaphysique, comme proposition, et l’idée heideggérienne d’une manifestation en cours est quelque peu analogue à celle différenciant les prétentions de vérité du Dieu chrétien de celles des dieux grecs, les premières présupposant l’objectivité totale d’une vérité universelle éternelle et inconditionnée préconçue dans l’esprit de Dieu, et les secondes acceptant que la « dissimulation » est aussi inhérente à la nature polymorphe de la vérité que l’est la manifestation [14].

Etant donné son affirmation a-historique de vérités immuables installées dans la raison pure, Heidegger affirme que l’élan préfigurant et décontextualisant de la métaphysique aliène les êtres de l’Etre, les figeant dans leurs représentations momentanées et les empêchant donc de se déployer en accord avec les possibilités offertes par leur monde spécifique. L’oubli de l’être culmine dans la civilisation technologique moderne, où l’être est défini simplement comme une chose disponible pour l’investigation scientifique, la manipulation technologique et la consommation humaine. La tradition métaphysique a obscurci l’Etre en le définissant en termes essentiellement anthropocentriques et même subjectivistes.

Mais en plus de rejeter les postulats inconditionnés de la métaphysique [15], Heidegger associe le mot « tradition » – ou du moins sa forme latinisée (die Tradition) – à l’héritage philosophique occidental et son oubli croissant de l’être. De même, il utilise l’adjectif « traditionell » péjorativement, l’associant à l’élan généralisant de la métaphysique et aux conventions quotidiennes insouciantes contribuant à l’oubli de l’Etre.

Mais après avoir noté cette particularité sémantique et son intention antimétaphysique, nous devons souligner que Heidegger n’était pas un ennemi de la tradition, car sa philosophie privilégie ces « manifestations de l’être » originelles dans lesquelles naissent les grandes vérités traditionnelles. Comme telle, la tradition pour lui n’est pas un ensemble de postulats désincarnés, pas quelque chose d’hérité passivement, mais une facette de l’Etre qui ouvre l’homme à un futur lui appartenant en propre. Dans cet esprit, il associe l’Überlieferung (signifiant aussi tradition) à la transmission de ces principes transcendants inspirant tout « grand commencement ».

La Tradition dans ce sens primordial permet à l’homme, pense-t-il, « de revenir à lui-même », de découvrir ses possibilités historiquement situées et uniques, et de se réaliser dans la plénitude de son essence et de sa vérité. En tant qu’héritage de destination, l’Überlieferung de Heidegger est le contraire de l’idéal décontextualisé des Traditionalistes. Dans Etre et Temps, il dit que die Tradition « prend ce qui est descendu vers nous et en fait une évidence en soi ; elle bloque notre accès à ces ‘sources’ primordiales dont les catégories et les concepts transmis à nous ont été en partie authentiquement tirés. En fait, elle nous fait oublier qu’elles ont eu une telle origine, et nous fait supposer que la nécessité de revenir à ces sources est quelque chose que nous n’avons même pas besoin de comprendre » [17]. Dans ce sens, Die Tradition oublie les possibilités formatives léguées par son origine de destination, alors que l’Überlieferung, en tant que transmission, les revendique. La pensée de Heidegger se préoccupe de retrouver l’héritage de ces sources anciennes.

Sa critique de la modernité (et, contrairement à ce qu’écrit Evola, il est l’un de ses grands critiques) repose sur l’idée que la perte ou la corruption de la tradition de l’Europe explique « la fuite des dieux, la destruction de la terre, la réduction des êtres humains à une masse, la prépondérance du médiocre » [18]. A présent vidé de ses vérités primordiales, le cadre de vie européen, dit-il, risque de mourir : c’est seulement en « saisissant ses traditions d’une manière créative », et en se réappropriant leur élan originel, que l’Occident évitera le « chemin de l’annihilation » que la civilisation rationaliste, bourgeoise et nihiliste de la modernité semble avoir pris » [19].

La tradition (Überlieferung) que défend l’antimétaphysique Heidegger n’est alors pas le royaume universel et supra-sensuel auquel se réfèrent les guénoniens lorsqu’ils parlent de la Tradition. Il s’agit plutôt de ces vérités primordiales que l’Etre rend présentes « au commencement » –, des vérités dont les sources historiques profondes et les certitudes constantes tendent à être oubliées dans les soucis quotidiens ou dénigrées dans le discours moderniste, mais dont les possibilités restent néanmoins les seules à nous être vraiment accessibles. Contre ces métaphysiciens, Heidegger affirme qu’aucune prima philosophia n’existe pour fournir un fondement à la vie ou à l’Etre, seulement des vérités enracinées dans des origines historiques spécifiques et dans les conventions herméneutiques situant un peuple dans ses grands récits.

Il refuse ainsi de réduire la tradition à une analyse réfléchie indépendante du temps et du lieu. Son approche phénoménologique du monde humain la voit plutôt comme venant d’un passé où l’Etre et la vérité se reflètent l’un l’autre et, bien qu’imparfaitement, affectent le présent et la manière dont le futur est approché. En tant que tels, Etre, vérité et tradition ne peuvent pas être saisis en-dehors de la temporalité (c’est-à-dire la manière dont les humains connaissent le temps). Cela donne à l’Etre, à la vérité et à la tradition une nature avant tout historique (bien que pas dans le sens progressiste, évolutionnaire et développemental favorisé par les modernistes). C’est seulement en posant la question de l’Etre, la Seinsfrage, que l’Etre de l’humain s’ouvre à « la condition de la possibilité de [sa] vérité ».

C’est alors à travers la temporalité que l’homme découvre la présence durable qui est l’Etre [20]. En effet, si l’Etre de l’homme n’était pas situé temporellement, sa transcendance, la préoccupation principale de la métaphysique guénonienne, serait inconcevable. De même, il n’y a pas de vérité (sur le monde ou les cieux au-dessus de lui) qui ne soit pas ancrée dans notre Etre-dans-le-monde – pas de vérité absolue ou de Tradition Universelle, seulement des vérités et des traditions nées de ce que nous avons été… et pouvons encore être. Cela ne veut pas dire que l’Etre de l’humain manque de transcendance, seulement que sa possibilité vient de son immanence – que l’Etre et les êtres, le monde et ses objets, sont un phénomène unitaire et ne peuvent pas être saisis l’un sans l’autre.

Parce que la conception heideggérienne de la tradition est liée à la question de l’Etre et parce que l’Etre est inséparable du Devenir, l’Etre et la tradition fidèle à sa vérité ne peuvent être dissociés de leur émergence et de leur réalisation dans le temps. Sein und Zeit, Etre immuable et changement historique, sont inséparables dans sa pensée. L’Etre, écrit-il, « est Devenir et le Devenir est Etre » [21]. C’est seulement par le processus du devenir dans le temps, dit-il, que les êtres peuvent se déployer dans l’essence de leur Etre. La présence constante que la métaphysique prend comme l’essence de l’Etre est elle-même un aspect du temps et ne peut être saisie que dans le temps – car le temps et l’Etre partagent une coappartenance primordiale.

Le monde platonique guénonien des formes impérissables et des idéaux éternels est ici rejeté pour un monde héraclitien de flux et d’apparition, où l’homme, fidèle à lui-même, cherche à se réaliser dans le temps – en termes qui parlent à son époque et à son lieu, faisant cela en relation avec son héritage de destination. Etant donné que le temps implique l’espace, la relation de l’être avec l’Etre n’est pas simplement un aspect individualisé de l’Etre, mais un « être-là » (Dasein) spécifique – situé, projeté, et donc temporellement enraciné dans ce lieu où l’Etre n’est pas seulement « manifesté » mais « approprié ». Sans « être-là », il n’y a pas d’Etre, pas d’existence. Pour lui, l’engagement humain dans le monde n’est pas simplement une facette située de l’Etre, c’est son fondement.

Ecarter la relation d’un être avec son temps et son espace (comme le fait la métaphysique atemporelle des guénoniens) est « tout aussi insensé que si quelqu’un voulait expliquer la cause et le fondement d’un feu [en déclarant] qu’il n’y a pas besoin de se soucier du cours du feu ou de l’exploration de sa scène » [22]. C’est seulement dans la « facticité » (le lien des pratiques, des suppositions, des traditions et des histoires situant son Devenir), et non dans une supra-réalité putative, que tout le poids de l’Etre – et la « condition fondamentale pour… tout ce qui est grand » – se fait sentir.

Quand les éternalistes interprètent « les êtres sans s’interroger sur [la manière dont] l’essence de l’homme appartient à la vérité de l’Etre », ils ne pourraient pas être plus opposés à Heidegger. En effet, pour eux l’Etre est manifesté comme Ame Cosmique (le maître plan de l’univers, l’Unité indéfinissable, l’Etre éternel), qui est détachée de la présence originaire et terrestre, distincte de l’Etre-dans-le-monde de Heidegger [23]. Contre l’idée décontextualisée et détachée du monde des métaphysiciens, Heidegger souligne que la présence de l’Etre est manifestée seulement dans ses états terrestres, temporels, et jamais pleinement révélés. Des mondes différents nous donnent des possibilités différentes, des manières différentes d’être ou de vivre. Ces mondes historiquement situés dictent les possibilités spécifiques de l’être humain, lui imposant un ordre et un sens. Ici Heidegger ne nie pas la possibilité de la transcendance humaine, mais la recherche au seul endroit où elle est accessible à l’homme – c’est-à-dire dans son da (« là »), sa situation spécifique. Cela fait du Devenir à la fois la toile de fond existentielle et l’« horizon transcendantal » de l’Etre, car même lorsqu’elle transcende sa situation, l’existence humaine est forcément limitée dans le temps et dans l’espace.

En posant la Seinsfrage de cette manière, il s’ensuit qu’on ne peut pas partir de zéro, en isolant un être abstrait et atomisé de tout ce qui le situe dans un temps et un espace spécifiques, car on ignorerait ainsi que l’être de l’homme est quelque chose de fini, enraciné dans un contexte historiquement conditionné et culturellement défini – on ignorerait, en fait, que c’est un Etre-là (Dasein). Car si l’existence humaine est prisonnière du flux du Devenir – si elle est quelque chose de situé culturellement, linguistiquement, racialement, et, avant tout, historiquement –, elle ne peut pas être comprise comme un Etre purement inconditionné.

Le caractère ouvert de la temporalité humaine signifie, de plus, que l’homme est responsable de son être. Il est l’être dont « l’être est lui-même une question », car, bien que située, son existence n’est jamais fixée ou complète, jamais déterminée à l’avance, qu’elle soit vécue d’une manière authentique ou non [24]. Elle est vécue comme une possibilité en développement qui se projette vers un futur « pas encore réel », puisque l’homme cherche à « faire quelque chose de lui-même » à partir des possibilités léguées par son origine spécifique. Cela pousse l’homme à se « soucier » de son Dasein, individualisant ses possibilités en accord avec le monde où il habite.

Ici le temps ne sert pas seulement d’horizon contre lequel l’homme est projeté, il sert de fondement (la facticité prédéterminée) sur lequel sa possibilité est réalisée. La possibilité que l’homme cherche dans le futur (son projet) est inévitablement affectée par le présent qui le situe et le passé modelant son sens de la possibilité. La projection du Dasein vient ainsi « vers lui-même d’une manière telle qu’il revient », anticipant sa possibilité comme quelque chose qui « a été » et qui est encore à portée de main [25]. Car c’est seulement en accord avec son Etre-là, sa « projection », qu’il peut être pleinement approprié – et transcendé [26].

En rejetant les concepts abstraits, inconditionnés et éternels de la métaphysique, Heidegger considère la vérité, en particulier les vérités primordiales que la tradition transmet, comme étant d’une nature historique et temporelle, liée à des manifestations distinctes (bien que souvent obscures) de l’Etre, et imprégnée d’un passé dont l’origine créatrice de destin inspire le sens humain de la possibilité. En effet, c’est la configuration distincte formée par la situation temporelle, l’ouverture de l’Etre, et la facticité situant cette rencontre qui forme les grandes questions se posant à l’homme, puisqu’il cherche à réaliser (ou à éviter) sa possibilité sur un fondement qu’il n’a pas choisi. « L’histoire de l’Etre », écrit Heidegger, « n’est jamais le passé mais se tient toujours devant nous ; elle soutient et définit toute condition et situation humaine » [27].

L’homme n’affronte donc pas les choix définissant son Dasein au sens existentialiste d’être « condamné » à prendre des décisions innombrables et arbitraires le concernant. L’ouverture à laquelle il fait face est plutôt guidée par les possibilités spécifiques à son existence historiquement située, alors que les « décisions » qu’il prend concernent son authenticité (c’est-à-dire sa fidélité à ses possibilités historiquement destinées, son destin). Puisqu’il n’y a pas de vérités métaphysiques éternelles inscrites dans la tradition, seulement des vérités posées par un monde « toujours déjà », vivre à la lumière des vérités de l’Etre requiert que l’homme connaisse sa place dans l’histoire, qu’il connaisse le lieu et la manière de son origine, et affronte son histoire comme le déploiement (ou, négativement, la déformation) des promesses posées par une prédestination originelle [28]. Une existence humaine authentique, affirme Heidegger, est « un processus de conquête de ce que nous avons été au service de ce que nous sommes » [29].

Le Primordial

Le « premier commencement » de l’homme – le commencement (Anfangen) « sans précédent et monumental » dans lequel ses ancêtres furent « piégés » (gefangen) comme une forme spécifique de l’Etre – met en jeu d’autres commencements, devenant le fondement de toutes ses fondations ultérieures [30]. En orientant l’histoire dans une certaine direction, le commencement – le primordial – « ne réside pas dans le passé mais se trouve en avant, dans ce qui doit venir » [31]. Il est « le décret lointain qui nous ordonne de ressaisir sa grandeur » [32]. Sans cette « reconquête », il ne peut y avoir d’autre commencement : car c’est en se réappropriant un héritage, dont le commencement est déjà un achèvement, que l’homme revient à lui-même, s’inscrivant dans le monde de son propre temps. « C’est en se saisissant du premier commencement que l’héritage… devient l’héritage ; et seuls ceux qui appartiennent au futur… deviennent [ses] héritiers » [33]. L’élève de Heidegger, Hans-Georg Gadamer dit que toutes les questions concernant les commencements « sont toujours [des questions] sur nous-mêmes et notre futur » [34].

Pour Heidegger, en transmettant la vérité de l’origine de l’homme, la tradition défie l’homme à se réaliser face à tout ce qui conspire pour déformer son être. De même qu’Evola pensait que l’histoire était une involution à partir d’un Age d’Or ancien, d’où un processus de décadence, Heidegger voit l’origine – l’inexplicable manifestation de l’Etre qui fait naître ce qui est « le plus particulier » au Dasein, et non universel – comme posant non seulement les trajectoires possibles de la vie humaine, mais les obstacles inhérents à sa réalisation. Se déployant sur la base de sa fondation primordiale, l’histoire tend ainsi à être une diminution, un déclin, un oubli ou une dissimulation des possibilités léguées par son « commencement », le bavardage oisif, l’exaltation de l’ordinaire et du quotidien, ou le règne du triomphe médiocre sur le destin, l’esprit de décision et l’authenticité des premières époques, dont la proximité avec l’Etre était immédiate, non dissimulée, et pleine de possibilités évidentes.

Là où Evola voit l’histoire en termes cycliques, chaque cycle restant essentiellement homogène, représentant un segment de la succession récurrente gouvernée par certains principes immuables, Heidegger voit l’histoire en termes des possibilités posées par leur appropriation. C’est seulement à partir des possibilités intrinsèques à la genèse originaire de sa « sphère de sens » – et non à partir du domaine supra-historique des guénoniens – que l’homme, dit-il, peut découvrir les tâches historiquement situées qui sont « exigées » de lui et s’ouvrir à leur possibilité [35]. En accord avec cela, les mots « plus ancien », « commencement » et « primordial » sont associés dans la pensée de Heidegger à l’essence ou la vérité de l’Etre, de même que le souvenir de l’origine devient une « pensée à l’avance de ce qui vient » [36].

Parce que le primordial se trouve devant l’homme, pas derrière lui, la révélation initiale de l’Etre vient dans chaque nouveau commencement, puisque chaque nouveau commencement s’inspire de sa source pour sa postérité. Comme Mnémosyne, la déesse de la mémoire qui était la muse principale des poètes grecs, ce qui est antérieur préfigure ce qui est postérieur, car la « vérité de l’Etre » trouvée dans les origines pousse le projet du Dasein à « revenir à lui-même ». C’est alors en tant qu’« appropriation la plus intérieure de l’Etre » que les origines sont si importantes. Il n’y a pas d’antécédent ou de causa prima, comme le prétend la logique inorganique de la modernité, mais « ce dont et ce par quoi une chose est ce qu’elle est et telle qu’elle est… [Ils sont] la source de son essence » et la manière dont la vérité « vient à être… [et] devient historique » [37]. Comme le dit le penseur français de la Nouvelle Droite, Alain de Benoist, l’« originel » (à la différence du novum de la modernité) n’est pas ce qui vient une fois pour toutes, mais ce qui vient et se répète chaque fois qu’un être se déploie dans l’authenticité de son origine » [38]. Dans ce sens, l’origine représente l’unité primordiale de l’existence et de l’essence exprimées dans la tradition. Et parce que l’« appropriation » à la fois originelle et ultérieure de l’Etre révèle la possibilité, et non l’environnement purement « factuel » ou « momentané » qui l’affecte, le Dasein n’accomplit sa constance propre que lorsqu’il est projeté sur le fondement de son héritage authentique [39].

La pensée heideggérienne n’est pas un existentialisme

Evola consacre plusieurs chapitres de Chevaucher le tigre (Calvacare la Tigre) à une critique de l’« existentialisme » d’après-guerre popularisé par Jean-Paul Sartre et dérivé, à ce qu’on dit, de la pensée de Heidegger » [40]. Bien que reconnaissant certaines différences entre Sartre et Heidegger, Evola les traitait comme des esprits fondamentalement apparentés. Son Sartre est ainsi décrit comme un non-conformiste petit-bourgeois et son Heidegger comme un intellectuel chicanier, tous deux voyant l’homme comme échoué dans un monde insensé, condamné à faire des choix incessants sans aucun recours transcendant. Le triste concept de liberté des existentialistes, affirme Evola, voit l’univers comme un vide, face auquel l’homme doit se forger son propre sens (l’« essence » de Sartre). Leur notion de liberté (et par implication, celle de Heidegger) est ainsi jugée nihiliste, entièrement individualiste et arbitraire.

En réunissant l’existentialisme sartrien et la pensée heideggérienne, Evola ne connaissait apparemment pas la « Lettre sur l’Humanisme » (1946-47) de Heidegger, dans laquelle ce dernier – d’une manière éloquente et sans ambiguïté – répudiait l’appropriation existentialiste de son œuvre. Il semble aussi qu’Evola n’ait connu que le monumental Sein und Zeit de Heidegger, qu’il lit, comme Sartre, comme une anthropologie philosophique sur les problèmes de l’existence humaine (c’est-à-dire comme un humanisme) plutôt que comme une partie préliminaire d’une première tentative de développer une « ontologie fondamentale » recherchant le sens de l’Etre. Il mettait donc Sartre et Heidegger dans le même sac, les décrivant comme des « hommes modernes », coupés du monde de la Tradition et imprégnés des « catégories profanes, abstraites et déracinées » de la pensée. Parlant de l’affirmation nihiliste de Sartre selon laquelle « l’existence précède l’essence » (qu’il attribuait erronément à Heidegger, qui identifiait l’une à l’autre au lieu de les opposer), le disciple italien de Guénon concluait qu’en situant l’homme dans un monde où l’essence est auto-engendrée, Heidegger rendait le présent concret ontologiquement primaire, avec une nécessité situationnelle, plutôt que le contexte de l’Etre [41]. L’Etre heideggérien est alors vu comme se trouvant au-delà de l’homme, poursuivi comme une possibilité irréalisable [42]. Cela est sensé lier l’Etre au présent, le détachant de la Tradition – et donc de la transcendance qui seule illumine les grandes tâches existentielles.

La critique évolienne de Heidegger, comme que nous l’avons suggéré, n’est pas fondée, ciblant une caricature de sa pensée. Il se peut que l’histoire et la temporalité soient essentielles dans le projet philosophique de Heidegger et qu’il accepte l’affirmation sartrienne qu’il n’existe pas de manières absolues et inchangées pour être humain, mais ce n’est pas parce qu’il croit nécessaire d’« abandonner le plan de l’Etre » pour le plan situationnel. Pour lui, le plan situationnel est simplement le contexte où les êtres rencontrent leur Etre.

Heidegger insiste sur la « structure événementielle temporelle » du Dasein parce qu’il voit les êtres comme enracinés dans le temps et empêtrés dans un monde qui n’est pas de leur propre création (même si l’Etre de ces êtres pourrait transcender le « maintenant » ou la série de « maintenant » qui les situent). En même temps, il souligne que le Dasein est connu d’une manière « extatique », car les pensées du passé, du présent et du futur sont des facettes étroitement liées de la conscience humaine. En effet, c’est seulement en reconnaissant sa dimension extatique (que les existentialistes et les métaphysiciens ignorent) que le Dasein peut « se soucier de l’ouverture de l’Etre », vivre dans sa lumière, et transcender son da éphémère (sa condition situationnelle). Heidegger écrit ainsi que le Dasein est « l’être qui émerge de lui-même » – c’est le dévoilement d’une essence historique-culturelle-existentielle dont le déploiement est étranger à l’élan objectifiant des formes platoniques [43].

En repensant l’Etre en termes de temporalité humaine, en le restaurant dans le Devenir historique, et en établissant le temps comme son horizon transcendant, Heidegger cherche à libérer l’existentiel des propriétés inorganiques de l’espace et de la matière, de l’agitation insensée de la vie moderne, avec son évasion instrumentaliste de l’Etre et sa « pseudo-culture épuisée » – et aussi de le libérer des idéaux éternels privilégiés par les guénoniens. Car si l’Etre est inséparable du Devenir et survient dans un monde-avec-les-autres, alors les êtres, souligne-t-il, sont inhérents à un « contexte de signification » saturé d’histoire et de culture. Poursuivant son projet dans ces termes, les divers modes existentiels de l’homme, ainsi que son monde, ne sont pas formés par des interprétations venant d’une histoire d’interprétations précédentes. L’interprétation elle-même (c’est-à-dire « l’élaboration de possibilités projetées dans la compréhension ») met le présent en question, affectant le déploiement de l’essence. En fait, la matrice chargée de sens mise à jour par l’interprétation constitue une grande part de ce qui forme le « là » (da) dans le Dasein [44].

Etant donné qu’il n’y a pas de Sein sans un da, aucune existence sans un fondement, l’homme, dans sa nature la plus intérieure, est inséparable de la matrice qui « rend possible ce qui a été projeté » [45]. A l’intérieur de cette matrice, l’Etre est inhérent à « l’appropriation du fondement du là » [46]. Contrairement à l’argumentation de Chevaucher le tigre, cette herméneutique historiquement consciente ne prive pas l’homme de l’Etre, ni ne nie la primauté de l’Etre, ni ne laisse l’homme à la merci de sa condition situationnelle. Elle n’a rien à voir non plus avec l’« indéterminisme » radical de Sartre – qui rend le sens contextuellement contingent et l’essence effervescente.

Pour Heidegger l’homme n’existe pas dans un seul de ses moments donnés, mais dans tous, car son être situé (le projet qu’il réalise dans le temps) ne se trouve dans aucun cas unique de son déploiement (ou dans ce que Guénon appelait « la nature indéfinie des possibilités de chaque état »). En fait, il existe dans toute la structure temporelle s’étendant entre la naissance et la mort de l’homme, puisqu’il réalise son projet dans le monde. Sans un passé et un futur pas-encore-réalisé, l’existence humaine ne serait pas Dasein, avec un futur légué par un passé qui est en même temps une incitation à un futur. A la différence de l’individu sartrien (dont l’être est une possibilité incertaine et illimitée) et à la différence de l’éternaliste (qui voit son âme en termes dépourvus de références terrestres), l’homme heideggérien se trouve seulement dans un retour (une « écoute ») à l’essence postulée par son origine.

Cette écoute de l’essence, la nécessité de la découverte de soi pour une existence authentique, n’est pas une pure possibilité, soumise aux « planifications, conceptions, machinations et complots » individuels, mais l’héritier d’une origine spécifique qui détermine son destin. En effet, l’être vient seulement de l’Etre [47]. La notion heideggérienne de la tradition privilégie donc l’Andenken (le souvenir qui retrouve et renouvelle la tradition) et la Verwindung (qui est un aller au-delà, un surmonter) – une idée de la tradition qui implique l’inséparabilité de l’Etre et du Devenir, ainsi que le rôle du Devenir dans le déploiement de l’Etre, plutôt que la négation du Devenir [48].

« Le repos originel de l’Etre » qui a le pouvoir de sauver l’homme du « vacarme de la vie inauthentique, anodine et extérieure » n’est cependant pas aisément gagné. « Retrouver le commencement de l’existence historico-spirituelle afin de la transformer en un nouveau commencement » (qui, à mon avis, définit le projet traditionaliste radical) requiert « une résolution anticipatoire » qui résiste aux routines stupides oublieuses de la temporalité humaine [49]. Inévitablement, une telle résolution anticipatoire ne vient que lorsqu’on met en question les « libertés déracinées et égoïstes » qui nous coupent des vérités en cours déploiement de l’Etre et nous empêchent ainsi de comprendre ce que nous sommes – un questionnement dont la nécessité vient des plus lointaines extrémités de l’histoire de l’homme et dont les réponses sont intégrales pour la tradition qu’elles forment » [50].

L’histoire pour Heidegger est donc un « choix pour héros », exigeant la plus ferme résolution et le plus grand risque, puisque l’homme, dans une confrontation angoissante avec son origine, réalise une possibilité permanente face à une conventionalité amnésique, auto-satisfaite ou effrayante [51]. Les choix historiques qu’il fait n’ont bien sûr rien à voir avec l’individualisme ou le subjectivisme (avec ce qui est arbitraire ou volontaire), mais surgissent de ce qui est vrai et « originel » dans la tradition. Le destin d’un homme (Geschick), comme le destin d’un peuple (Schicksal), ne concerne pas un « choix », mais quelque chose qui est « envoyée » (geschickt) depuis un passé lointain qui a le pouvoir de déterminer une possibilité future. L’Etre, écrit Heidegger, « proclame le destin, et donc le contrôle de la tradition » [52].

En tant qu’appropriation complète de l’héritage dont l’homme hérite à sa naissance, son destin n’est jamais forcé ou imposé. Il s’empare des circonstances non-choisies de sa communauté et de sa génération, puisqu’il recherche la possibilité léguée par son héritage, fondant son existence dans sa « facticité historique la plus particulière » – même si cette appropriation implique l’opposition à « la dictature particulière du domaine public » [53]. Cela rend l’identité individuelle inséparable de son identité collective, puisque l’Etre-dans-le-monde reconnaît son Etre-avec-les-autres (Mitsein). L’homme heideggérien ne réalise ce qu’il est qu’à travers son implication dans le temps et l’espace de sa propre existence destinée, puisqu’il se met à « la disposition des dieux », dont l’actuel « retrait demeure très proche » [54].

La communauté de notre propre peuple, le Mitsein, est le contexte nécessaire de notre Dasein. Comme telle, elle est « ce en quoi, ce dont et ce pour quoi l’histoire arrive » [55]. Comme l’écrit Gadamer, le Mitsein « est un mode primordial d’‘Etre-nous’ – un mode dans lequel le Je n’est pas supplanté par un vous [mais] …englobe une communauté primordiale » [56]. Car même lorsqu’elle s’oppose aux conventions dominantes par besoin d’authenticité individuelle, la recherche de possibilité par le Dasein est une « co-historisation » avec une communauté – une co-historisation dans laquelle un héritage passé devient la base d’un futur plein de sens [57]. Le destin qu’il partage avec son peuple est en effet ce qui fonde le Dasein dans l’historicité, le liant à l’héritage (la tradition) qui détermine et est déterminé par lui [58].

En tant qu’horizon de la transcendance heideggérienne, l’histoire et la tradition ne sont donc jamais universelles, mais plurielles et multiples, produit et producteur d’histoires et de traditions différentes, chacune ayant son origine et sa qualité d’être spécifiques. Il peut y avoir certaines vérités abstraites appartenant aux peuples et aux civilisations partout, mais pour Heidegger il n’y a pas d’histoire ou de tradition abstraites pour les inspirer, seulement la pure transcendance de l’Etre. Chaque grand peuple, en tant qu’expression distincte de l’Etre, possède sa propre histoire, sa propre tradition, sa propre transcendance, qui sont sui generis. Cette spécificité même est ce qui donne une forme, un but et un sens à son expérience d’un monde perpétuellement changeant. Il se peut que l’Etre de l’histoire et de la tradition du Dasein soit universel, mais l’Etre ne se manifeste que dans les êtres, l’ontologie ne se manifeste que dans l’ontique. Selon les termes de Heidegger, « c’est seulement tant que le Dasein existe… qu’il y a l’Etre » [59].

Quand la métaphysique guénonienne décrit la Vérité Eternelle comme l’unité transcendante qui englobe toutes les « religions archaïques » et la plupart des « religions terrestres », elle offre à l’homme moderne une hauteur surplombante d’où il peut évaluer les échecs de son époque. Mais la vaste portée de cette vision a pour inconvénient de réduire l’histoire et la tradition de peuples et de civilisations différents (dont elle rejette en fait les trajectoires singulières) à des variantes sur un unique thème universel (« La pensée moderne, les Lumières, maçonnique », pourrait-on ajouter, nie également l’importance des histoires et des traditions spécifiques).

Par contre, un traditionaliste radical au sens heideggérien se définit en référence non à l’Eternel mais au Primordial dans son histoire et sa tradition, même lorsqu’il trouve des choses à admirer dans l’histoire et la tradition des non-Européens. Car c’est l’Europe qui l’appelle à sa possibilité future. Comme la vérité, la tradition dans la pensée de Heidegger n’est jamais une abstraction, jamais une formulation supra-humaine de principes éternels pertinents pour tous les peuples (bien que ses effets formatifs et sa possibilité futurale puissent assumer une certaine éternité pour ceux à qui elle parle). Il s’agit plutôt d’une force dont la présence illumine les extrémités éloignées de l’âme ancestrale d’un peuple, mettant son être en accord avec l’héritage, l’ordre et le destin qui lui sont singuliers.

Héraclite et Parménide

Quiconque prend l’histoire au sérieux, refusant de rejeter des millénaires de temporalité européenne, ne suivra probablement pas les éternalistes dans leur quête métaphysique. En particulier dans notre monde contemporain, où les forces régressives de mondialisation, du multiculturalisme et de la techno-science cherchent à détruire tout ce qui distingue les peuples et la civilisation de l’Europe des peuples et des civilisations non-européens. Le traditionaliste radical fidèle à l’incomparable tradition de la Magna Europa (et fidèle non pas au sens égoïste du nationalisme étroit, mais dans l’esprit de l’« appartenance au destin de l’Occident ») ne peut donc qu’avoir une certaine réserve envers les guénoniens – mais pas envers Evola lui-même, et c’est ici le tournant de mon argumentation. Car après avoir rejeté la Philosophie Eternelle et sa distillation évolienne, il est important, en conclusion, de « réconcilier » Evola avec les impératifs traditionalistes radicaux de la pensée heideggérienne – car l’alpiniste Evola ne fut pas seulement un grand Européen, un défenseur infatigable de l’héritage de son peuple, mais aussi un extraordinaire Kshatriya, dont l’héroïque Voie de l’Action inspire tous ceux qui s’identifient à sa « Révolte contre le monde moderne ».

Bien qu’il faudrait un autre article pour développer ce point, Evola, même lorsqu’il se trompe métaphysiquement, offre au traditionaliste radical une œuvre dont les motifs boréens demandent une étude et une discussion approfondies. Mais étant donné l’argument ci-dessus, comment les incompatibilités radicales entre Heidegger et Evola peuvent-elles être réconciliées ?

Bien qu’il faudrait un autre article pour développer ce point, Evola, même lorsqu’il se trompe métaphysiquement, offre au traditionaliste radical une œuvre dont les motifs boréens demandent une étude et une discussion approfondies. Mais étant donné l’argument ci-dessus, comment les incompatibilités radicales entre Heidegger et Evola peuvent-elles être réconciliées ?

La réponse se trouve, peut-être, dans cette « étrange » unité reliant les deux premiers penseurs de la tradition européenne, Héraclite et Parménide, dont les philosophies étaient aussi antipodiques que celles de Heidegger et Evola. Héraclite voyait le monde comme un « grand feu », dans lequel tout était toujours en cours de consumation, de même que l’Etre fait perpétuellement place au Devenir. Parménide, d’autre part, soulignait l’unité du monde, le voyant comme une seule entité homogène, dans laquelle tous ses mouvements apparents (le Devenir) faisaient partie d’une seule universalité (l’Etre), les rides et les vagues sur le grand corps de la mer. Mais si l’un voyait le monde en termes de flux et l’autre en termes de stase, ils reconnaissaient néanmoins tous deux un logos unifiant commun, une structure sous-jacente, une « harmonie rassemblée », qui donnait unité et forme à l’ensemble – que l’ensemble se trouvât dans le tourbillon apparemment insensé des événements terrestres ou dans l’interrelation de ses parties innombrables. Cette unité est l’Etre, dont la domination ordonnatrice du monde sous-tend la sensibilité parente animant les distillations originelles de la pensée européenne.

Les projets rivaux de Heidegger et Evola peuvent être vus sous un éclairage similaire. Dans une métaphysique soulignant l’universel et l’éternel, l’opposition de l’Etre et du Devenir, et la primauté de l’inconditionné, Evola s’oppose à la position de Heidegger, qui met l’accent sur le caractère projeté et temporel du Dasein. Evola parvient cependant à quelque chose qui s’apparente aux vues les plus élevées de la pensée heideggérienne. Car quand Heidegger explore le fondement primordial des différents êtres, recherchant le transcendant (l’Etre) dans l’immanence du temps (le Devenir), lui aussi saisit l’Etre dans sa présence impérissable, car à cet instant le primordial devient éternel – pas pour tous les peuples (étant donné que l’origine et le destin d’un peuple sont inévitablement singuliers), mais encore pour ces formes collectives de Dasein dont les différences sont de la même essence (dans la mesure où elles sont issues du même héritage indo-européen).

L’accent mis par Heidegger sur le primordialisme est, je crois, plus convainquant que l’éternalisme d’Evola, mais il n’est pas nécessaire de rejeter ce dernier en totalité (en effet, on peut se demander si dans Etre et Temps Heidegger lui-même n’a pas échoué à réconcilier ces deux facettes fondamentales de l’ontologie). Il se peut donc que Heidegger et Evola approchent l’Etre depuis des points de départ opposés et arrivent à des conclusions différentes (souvent radicalement différentes), mais leur pensée, comme celle d’Héraclite et de Parménide, convergent non seulement dans la primauté qu’ils attribuent à l’Etre, mais aussi dans la manière dont leur compréhension de l’Etre, particulièrement en relation avec la tradition, devient un antidote à la crise du nihilisme européen.

Notes

[1] Dominique Venner, Histoire et tradition des Européens : 30.000 ans d’identité (Paris : Rocher, 2002), p. 18. Cf. Michael O’Meara, « From Nihilism to Tradition », The Occidental Quarterly 3: 2 (été 2004).

[2] Friedrich Nietzsche, The Will to Power, trad. par W. Kaufmann et R. J. Hollingdale (New York: Vintage, 1967), pp. 9-39 ; Friedrich Nietzsche, The Gay Science, trad. par W. Kaufmann (New York: Vintage, 1975), § 125. Cf. Martin Heidegger, Nietzsche : 4. Nihilism, trad. par F.A. Capuzzi (San Francisco: Harper, 1982).

[3] « Editorial Prefaces », TYR : Myth – Culture – Tradition 1 et 2 (2002 et 2004).

[4] M. Raphael Johnson, « The State as the Enemy of the Ethnos », at http://es.geocities.com/sucellus23/807.htm. Dans Humain, trop humain (§ 96), Nietzsche écrit : La tradition émerge « sans égard pour le bien ou le mal ou autre impératif catégorique, mais… avant tout dans le but de maintenir une communauté, un peuple ».

[5] Martin Heidegger, Introduction to Metaphysics, trad. par G. Fried et R. Polt (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2000), p. 11.

[6] Bien que Guénon eut un effet formatif sur Evola, qui le considérait comme son « maître », l’Italien était non seulement suffisamment indépendant pour se séparer de Guénon sur plusieurs questions importantes, particulièrement en soulignant les origines « boréennes » ou indo-européennes de la Tradition, mais aussi en donnant au projet traditionaliste une tendance nettement militante et européaniste (je soupçonne que c’est cette tendance dans la pensée d’Evola, combinée à ce qu’il prend à Bachofen, Nietzsche et De Giorgio, qui le met – du moins sourdement – en opposition avec sa propre appropriation de la métaphysique guénonienne). En conséquence, certains guénoniens refusent de le reconnaître comme l’un des leurs. Par exemple, le livre de Kenneth Oldmeadow, Traditionalism : Religion in Light of the Perennial Philosophy (Colombo : The Sri Lanka Institute of Traditional Studies, 2000), à présent le principal ouvrage en anglais sur les traditionalistes, ne fait aucune référence à lui. Mon avis est que l’œuvre d’Evola n’est pas aussi importante que celle de Guénon pour l’Eternalisme, mais que pour le « radical » européen, c’est sa distillation la plus intéressante et la plus pertinente. Cf. Mark Sedgwick, Against the Modern World: Traditionalism and the Secret History of the Twentieth Century (New York: Oxford University Press, 2004) ; Piero Di Vona, Evola y Guénon: Tradition e civiltà (Naples: S.E.N., 1985) ; Roger Parisot, « L’ours et le sanglier ou le conflit Evola-Guénon », L’âge d’or 11 (automne 1995).

[7] L’attrait tout comme la mystification du concept évolien sont peut-être le mieux exprimés dans l’extrait suivant de la fameuse recension de Révolte contre le monde moderne par Gottfried Benn : « Quel est donc ce Monde de la Tradition ? Tout d’abord, son évocation romancée ne représente pas un concept naturaliste ou historique, mais une vision, une incantation, une intuition magique. Elle évoque le monde comme un universel, quelque chose d’à la fois céleste et supra-humain, quelque chose qui survient et qui a un effet seulement là où l’universel existe encore, là où il est sensé, et où il est déjà exception, rang, aristocratie. A travers une telle évocation, la culture est libérée de ses éléments humains, historiques, libérée pour prendre cette dimension métaphysique dans laquelle l’homme se réapproprie les grands traits primordiaux et transcendants de l’Homme Traditionnel, porteur d’un héritage ». « Julius Evola, Erhebung wider die moderne Welt » (1935), http://www.regin-verlag.de.

[8] Julius Evola, « La vision romaine du sacré » (1934), dans Symboles et mythes de la Tradition occidentale, trad. par H.J. Maxwell (Milan : Arché, 1980).

[9] Julius Evola, Men Among the Ruins, trad. par G. Stucco (Rochester, Vermont: Inner Traditions, 2002), p. 116 ; Julius Evola, « Che cosa è la tradizione » dans L’arco e la clava (Milan: V. Scheiwiller, 1968).

[10] Luc Saint-Etienne, « Julius Evola et la Contre-Révolution », dans A. Guyot-Jeannin, ed., Julius Evola (Lausanne : L’Age d’Homme, 1997).

[11] Julius Evola, Revolt against the Modern World, trad. par G. Stucco (Rochester, Vermont: Inner Traditions International, 1995), p. 6.

[12] En accord avec une ancienne convention des études heideggériennes de langue anglaise, « Etre » est utilisé ici pour désigner das Sein et « être » das Seiende, ce dernier se référant à une entité ou à une présence, physique ou spirituelle, réelle ou imaginaire, qui participe à l’« existence » de l’Etre (das Sein). Bien que différant en intention et en ramification, les éternalistes conservent quelque chose de cette distinction. Cf. René Guénon, The Multiple States of Being, trad. par J. Godwin (Burkett, N.Y.: Larson, 1984).

[13] Martin Heidegger, The End of Philosophy, trad. par J. Stambaugh (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1973), p. 32.

[14] Cf. Alain de Benoist, On Being a Pagan, trad. par J. Graham (Atlanta: Ultra, 2004).

[15] On dit que la métaphysique guénonienne est plus proche de l’identification de la vérité et de l’Etre par Platon que de la tradition post-aristotélicienne, dont la distinction entre idée et réalité (Etre et être, essence et apparence) met l’accent sur la seconde, aux dépens de la première. Heidegger, The End of Philosophy, pp. 9-19.

[16] Martin Heidegger, Being and Time, trad. par J. Macquarrie et E. Robinson (New York: Harper & Row, 1962), § 6 ; aussi Martin Heidegger, “The Age of the World Picture”, dans The Question Concerning Technology and Others Essays, trad. par W. Lovitt (New York: Harper & Row, 1977).

[17] Heidegger, Being and Time, § 6.

[18] Heidegger, Introduction to Metaphysics, p. 47.

[19] Heidegger, Introduction to Metaphysics, p. 41.

[20] Heidegger, Being and Time, § 69b.

[21] Martin Heidegger, Nietzsche: 1. The Will to Power as Art, trad. par D. F. Krell (San Francisco: Harper, 1979), p. 22.

[22] Heidegger, Introduction to Metaphysics, p. 35.

[23] Martin Heidegger, “Letter on Humanism”, dans Pathmarks, prep. par W. McNeil (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998).

[24] Heidegger, Being and Time, § 79.

[25] Heidegger, Being and Time, § 65.

[26] Certaines parties de ce paragraphe et plusieurs autres plus loin sont tirées de mon livre New Culture, New Right: Anti-Liberalism in Postmodern Europe (Bloomington: 1stBooks, 2004), pp. 123ff.

[27] Heidegger, “Letter on Humanism”.

[28] Martin Heidegger, Plato’s Sophist, trad. par R. Rojcewicz et A. Schuwer (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1976), p. 158.

[29] Heidegger, Being and Time, § 76.

[30] Martin Heidegger, Contributions to Philosophy (From Enowning), trad. par P. Emad et K. Mahy (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1999), § 3 et § 20.

[31] Martin Heidegger, Parmenides, trad. par A. Schuwer et R. Rojcewicz (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1992), p. 1.

[32] Martin Heidegger, “The Self-Assertion of the German University”, dans The Heidegger Controversy, prep. par Richard Wolin (Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 1993). Aussi : « Seul ce qui est unique est recouvrable et répétable… Le commencement ne peut jamais être compris comme le même, parce qu’il s’étend en avant et ainsi va chaque fois au-delà de ce qui est commencé à travers lui et détermine de même son propre recouvrement ». Heidegger, Contributions to Philosophy, § 20.

[33] Heidegger, Contributions to Philosophy, § 101.

[34] Hans-Georg Gadamer, Heidegger’s Ways, trad. par J. W. Stanley (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1994), p. 64.

[35] Gadamer, Heidegger’s Ways, p. 33.

[36] Martin Heidegger, Hölderlin’s Hymn “The Ister”, trad. par W. McNeil et J. Davis (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1996), p. 151.

[37] Martin Heidegger, “The Origin of the Work of Art”, dans Basic Writings, prep. par D. F. Krell (New York: Harper & Row, 1977).

[38] Alain de Benoist, L’empire intérieur (Paris: Fata Morgana, 1995), p. 18.

[39] Heidegger, Being and Time, § 65.

[40] Julius Evola, Ride the Tiger, trad. par J. Godwin et C. Fontana (Rochester, Vermont: Inner Traditions, 2003), pp. 78-103.

[41] Cf. Martin Heidegger, The Basic Problems of Phenomenology, trad. par A. Hofstader (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1982), pt. 1, ch. 2.

[42] Quand Evola écrit dans Ride the Tiger que Heidegger voit l’homme « comme une entité qui ne contient pas l’être… mais [se trouve] plutôt devant lui, comme si l’être était quelque chose à poursuivre ou à capturer » (p. 95), il interprète très mal Heidegger, suggérant que ce dernier dresse un mur entre l’Etre et l’être, alors qu’en fait Heidegger voit le Dasein humain comme une expression de l’Etre – mais, du fait de la nature humaine, une expression qui peut ne pas être reconnue comme telle ou authentiquement réalisée.

[43] Heidegger, Parmenides, p. 68.

[44] Heidegger, Being and Time, § 29 ; Contributions to Philosophy, § 120 et § 255.

[45] Heidegger, Being and Time, § 65.

[46] Heidegger, Contributions to Philosophy, § 92.

[47] Heidegger, Being and Time, § 37.

[48] Gianni Vattimo, The End of Modernity, trad. par J. R. Synder (Baltimore: The John Hopkins University Press, 1985), pp. 51-64.

[49] Heidegger, Introduction to Metaphysics, pp. 6-7.

[50] Heidegger, Contributions to Philosophy, § 117 et § 184 ; cf. Carl Schmitt, Political Theology, trad. par G. Schwab (Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 1985).

[51] Heidegger, Being and Time, § 74.

[52] Martin Heidegger, “The Onto-theo-logical Nature of Metaphysics”, dans Essays in Metaphysics, trad. par K. F. Leidecker (New York: Philosophical Library, 1960).

[53] Heidegger, Contributions to Philosophy, § 5.

[54] Heidegger, Contributions to Philosophy, § 5.

[55] Heidegger, Introduction to Metaphysics, p. 162.

[56] Gadamer, Heidegger’s Ways, p. 12.

[57] Heidegger, Being and Time, § 74.

[58] Heidegger, Being and Time, § 74.

[59] Heidegger, Being and Time, § 43c.

Source: TYR: Myth — Culture — Tradition, vol. 3, ed. Joshua Buckley and Michael Moynihan (Atlanta: Ultra, 2007), pp. 67-88.

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

Durant l’été 1942 – alors que les Allemands étaient au sommet de leur puissance, totalement inconscients de l’approche de la tempête de feu qui allait transformer leur pays natal en enfer – le philosophe Martin Heidegger écrivit (pour un cours prévu à Freiberg) les lignes suivantes, que je prends dans la traduction anglaise connue sous le titre de Hölderlin’s Hymn “The Ister”: [1]

Durant l’été 1942 – alors que les Allemands étaient au sommet de leur puissance, totalement inconscients de l’approche de la tempête de feu qui allait transformer leur pays natal en enfer – le philosophe Martin Heidegger écrivit (pour un cours prévu à Freiberg) les lignes suivantes, que je prends dans la traduction anglaise connue sous le titre de Hölderlin’s Hymn “The Ister”: [1]

Unfortunately, when we see the legitimate political expression of the Irish people in action, it is not impressive. The Cabinet of the Irish Republic is meeting in a tunnel. Dressed in suits and ties and carrying briefcases, they seem unlikely revolutionaries, squabbling over the extent of each minister’s “brief” and constantly pulling rank on one another.

Unfortunately, when we see the legitimate political expression of the Irish people in action, it is not impressive. The Cabinet of the Irish Republic is meeting in a tunnel. Dressed in suits and ties and carrying briefcases, they seem unlikely revolutionaries, squabbling over the extent of each minister’s “brief” and constantly pulling rank on one another. The problem is that all of this political maneuvering should be secondary to his primary role of leading a military effort. Though de Valera is obviously commander in chief, he has little connection to actual military operations throughout the film. This is at least a partial explanation for his stunning strategic incompetence.

The problem is that all of this political maneuvering should be secondary to his primary role of leading a military effort. Though de Valera is obviously commander in chief, he has little connection to actual military operations throughout the film. This is at least a partial explanation for his stunning strategic incompetence.

I would like to talk about something that has always interested me. The title of the talk is “Léon Degrelle and the Real Tintin,” but what I really want to talk about is the heroic in mass and in popular culture. It’s interesting to note that heroic ideas and ideals have been disprivileged by pacifism, by liberalism tending to the Left and by feminism particularly since the social and cultural revolutions of the 1960s. Yet the heroic, as an imprimatur in Western society, has gone down into the depths, into mass popular culture. Often into trashy forms of culture where the critical insight of various intellectuals doesn’t particularly gaze upon it.

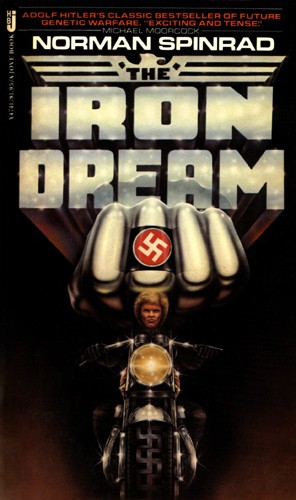

I would like to talk about something that has always interested me. The title of the talk is “Léon Degrelle and the Real Tintin,” but what I really want to talk about is the heroic in mass and in popular culture. It’s interesting to note that heroic ideas and ideals have been disprivileged by pacifism, by liberalism tending to the Left and by feminism particularly since the social and cultural revolutions of the 1960s. Yet the heroic, as an imprimatur in Western society, has gone down into the depths, into mass popular culture. Often into trashy forms of culture where the critical insight of various intellectuals doesn’t particularly gaze upon it. There’s a well-known novel called The Iron Dream and this novel is in a sense depicting Hitler’s rise to power and everything that occurred in the war that resulted thereafter as a science fiction discourse, as a sort of semiotic by a mad creator. This book was actually banned in Germany because although it’s an extreme satire, which is technically very anti-fascistic, it can be read in a literal-minded way with the satire semi-detached. This novel by Norman Spinrad was banned for about 20 to 30 years in West Germany as it then was. Because fantasy enables certain people to have an irony bypass.

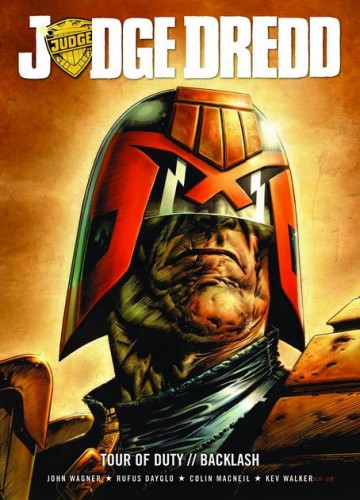

There’s a well-known novel called The Iron Dream and this novel is in a sense depicting Hitler’s rise to power and everything that occurred in the war that resulted thereafter as a science fiction discourse, as a sort of semiotic by a mad creator. This book was actually banned in Germany because although it’s an extreme satire, which is technically very anti-fascistic, it can be read in a literal-minded way with the satire semi-detached. This novel by Norman Spinrad was banned for about 20 to 30 years in West Germany as it then was. Because fantasy enables certain people to have an irony bypass. Various writers like Pat Mills and John Wagner were told to come up with something else. So, they came up with the comic that became Judge Dredd. Judge Dredd is a very interesting comic in various ways because all sorts of Left-wing people don’t like Judge Dredd at all, even as a satire. If there are people who don’t know this, Dredd drives around in a sort of motorcycle helmet with a slab-sided face which is just human meat really, and he’s an ultra-American. It’s set in a dystopian future where New York is extended to such a degree that it covers about a quarter of the landmass of the United States. You just live in a city, in a burg, and you go and you go and you go. There’s total collapse. There’s no law and order, and there’s complete unemployment, and everyone’s bored out of their mind.

Various writers like Pat Mills and John Wagner were told to come up with something else. So, they came up with the comic that became Judge Dredd. Judge Dredd is a very interesting comic in various ways because all sorts of Left-wing people don’t like Judge Dredd at all, even as a satire. If there are people who don’t know this, Dredd drives around in a sort of motorcycle helmet with a slab-sided face which is just human meat really, and he’s an ultra-American. It’s set in a dystopian future where New York is extended to such a degree that it covers about a quarter of the landmass of the United States. You just live in a city, in a burg, and you go and you go and you go. There’s total collapse. There’s no law and order, and there’s complete unemployment, and everyone’s bored out of their mind. This interconnection between mass popular culture, often of a very trivial sort, and elitist culture, whereby philosophically the same ideas are expressed, is actually interesting. You sometimes get these lightning flashes that occur between absolutely sort of “trash culture,” if you like, and quite advanced forms of culture like A Clockwork Orange, like Darkness at Noon, like Nineteen Eighty-Four, like The Iron Heel, like The Iron Dream. And these sorts of extraordinary dystopian and catatopian novels, which are in some respects the high political literature (as literature, literature qua literature) of the 20th century.

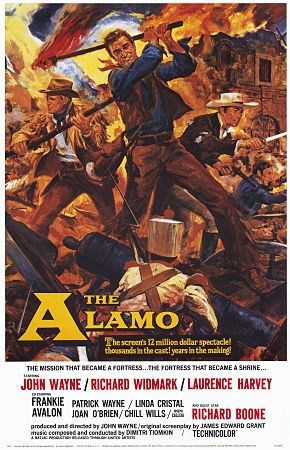

This interconnection between mass popular culture, often of a very trivial sort, and elitist culture, whereby philosophically the same ideas are expressed, is actually interesting. You sometimes get these lightning flashes that occur between absolutely sort of “trash culture,” if you like, and quite advanced forms of culture like A Clockwork Orange, like Darkness at Noon, like Nineteen Eighty-Four, like The Iron Heel, like The Iron Dream. And these sorts of extraordinary dystopian and catatopian novels, which are in some respects the high political literature (as literature, literature qua literature) of the 20th century. Don’t forget, The Alamo is now a politically incorrect film. Very politically incorrect. There’s an enormous women’s organization in Texas called the Daughters of the Alamo, and they had to change their name because the White Supremacist celebration of the Alamo was offensive to Latinos who are, or who will be very shortly, a Texan majority don’t forget. So, the sands are shifting in relation to what is permitted even within popular forms of culture.

Don’t forget, The Alamo is now a politically incorrect film. Very politically incorrect. There’s an enormous women’s organization in Texas called the Daughters of the Alamo, and they had to change their name because the White Supremacist celebration of the Alamo was offensive to Latinos who are, or who will be very shortly, a Texan majority don’t forget. So, the sands are shifting in relation to what is permitted even within popular forms of culture. Luthor and Superman in the stories are outsiders. They’re both extraterrestrials. Luthor, however, has anti-humanist values, which means he’s “evil,” whereas Superman, who’s partly human, has “humanist” values. Luthor comes up with amazing things, particularly in the 1930s comics, which are quite interesting, particularly given the ethnicity of the people who created Superman. Now, about half of American comics are very similar to the film industry, and a similar ethnicity is in the film industry as in the comics industry. Part of the notions of what is right and what is wrong, what is American and what is not, is defined by that particular grid.

Luthor and Superman in the stories are outsiders. They’re both extraterrestrials. Luthor, however, has anti-humanist values, which means he’s “evil,” whereas Superman, who’s partly human, has “humanist” values. Luthor comes up with amazing things, particularly in the 1930s comics, which are quite interesting, particularly given the ethnicity of the people who created Superman. Now, about half of American comics are very similar to the film industry, and a similar ethnicity is in the film industry as in the comics industry. Part of the notions of what is right and what is wrong, what is American and what is not, is defined by that particular grid.

Bien qu’il faudrait un autre article pour développer ce point, Evola, même lorsqu’il se trompe métaphysiquement, offre au traditionaliste radical une œuvre dont les motifs boréens demandent une étude et une discussion approfondies. Mais étant donné l’argument ci-dessus, comment les incompatibilités radicales entre Heidegger et Evola peuvent-elles être réconciliées ?

Bien qu’il faudrait un autre article pour développer ce point, Evola, même lorsqu’il se trompe métaphysiquement, offre au traditionaliste radical une œuvre dont les motifs boréens demandent une étude et une discussion approfondies. Mais étant donné l’argument ci-dessus, comment les incompatibilités radicales entre Heidegger et Evola peuvent-elles être réconciliées ?