The architects of the European Union argue that their construction is an unprecedented achievement following the fratricidal conflicts of the World Wars. Indeed, never before have sovereign nation-states freely consented to forming such a trade bloc and currency union. Furthermore, advocates of European integration argue that the Union’s common citizenship, promotion of regional identity, and open internal borders have softened the harsh lines between national identities. Many Identitarians have welcomed these aspects of the EU as a healthy manifestation of “implicit whiteness.”[1]

The EU, however, has more often been an object of contempt for most nationalists as impotent or as a destructive emanation of American power.[2] Indeed, for them the EU is not a manifestation of European sovereignty, but is rather an enforcer of the blank-slatist and globalist ideology which is leading to the physical replacement and reduction to minorityhood of indigenous Europeans in their own homelands. In this article I hope to shed light on this complex problem, disentangling the American role and indigenous European agency in the emergence of the EU as a decidedly “liberal” project.

The Traditional Critique: An Americano-Globalist Project

The traditional nationalist critique of existing European integration is that, far from reflecting European identity and interests, the project is a fundamentally anti-European one based on globalist ideology and American power.

The traditional nationalist critique of existing European integration is that, far from reflecting European identity and interests, the project is a fundamentally anti-European one based on globalist ideology and American power.

This critique would cite the interwar Austro-Japanese writer Count Richard Nikolaus von Coudenhove-Kalergi, who argued that European unity would pave the way for the genocide of the indigenous peoples of Europe through universal miscegenation and the creation of the “Eurasian-Negroid race of the future, similar in its appearance to the Ancient Egyptians.” This would be an Endlösung to the racial question, so to speak.[3] Coudenhove-Kalergi specifically praised Jews for their leading role as “a spiritual nobility of Europe.” These feverish speculations were not merely those of a marginal, alienated half-caste, given that Coudenhove-Kalergi was formally recognized for his decades of activism by being awarded the first Charlemagne Prize by the city of Aachen in 1950, the official honor for mainstream Europeanism.

The nationalist critique could further cite the French cognac salesman and CIA-funded political operator Jean Monnet, no doubt the most influential postwar advocate of European integration and the first president of the European Coal and Steel Community. Monnet was not only clearly an expression of American and corporate power – European unity as the destruction of borders restraining international capitalism and getting the West Europeans in marching order for eventual war with the Soviet Union – but also saw the “European Community” as a mere intermediary step to a kind of global government.[4]

Nationalists would further argue that the European Union has used its power to undermine the homogeneity and sovereignty of European nations. In particular, the EU’s so-called “European values” are based on an anti-national and neoliberal ideology, hell bent on promoting blank-slatist and politically-correct censorship legislation, tearing down national borders, deracinating national bourgeoisies, and making states beholden to financial markets under the euphemistic label “market discipline.” The most symbolically shocking recent example of this has been the big Western European states’ decision during the current migrant crisis to impose a redistribution of Afro-Islamic settlers across Europe, including against unwilling and innocent Central European nations.

The EU’s geopolitical impact in this respect is undeniable. There are strong economic incentives for poorer nations to join the “European club,” with carrots such as access to the Common Market, funding from the EU budget (with net transfers of up to 2 percent of GDP), and unlimited immigration opportunities to the wealthier countries. These promises, which can be considered a form of bribery, have had a considerable effect in undermining nationalist regimes in southern Europe and Russian influence in Serbia, Moldova, and Ukraine.

French Attempts to “Turn” the European Project

The European Union however cannot simply be reduced to an American emanation, if only because European politicians – and in particular French ones – have sought to turn it into a genuinely independent power. This was evident in President Charles de Gaulle’s push for an almost non-aligned foreign policy based on cooperation with the Third World, rapprochement with West Germany, and emancipation of Europe from the United States of America.

In practice however, the General failed to pry the insecure West Germans from the United States and the achievements for Europe were singularly modest: The exclusion of Great Britain – considered to be an American Trojan horse – from the European Economic Community, the securing of substantial mostly German-funded subsidies for French farming under the Common Agricultural Policy, the maintenance of moderate tariffs at about 0.5 percent of GDP,[5] and the blocking of any further “Atlanticist” integration with the veto. De Gaulle was clearly more successful in securing some narrow French interests rather than broader European ones.[6]

De Gaulle’s failure is indeed humbling. Francis Parkey Yockey no doubt said more in a passing comment on the ambiguities of the General’s career and his brand of French nationalism than many hundreds of pages of official Gaullist hagiography: “De Gaulle wants more: he wants to be equal to the masters who created him and blew him up like a rubber balloon.”[7]

Later, President François Mitterrand would go further than ever in pushing for European integration – above all the creation of a common currency, the euro – in a kind of grand experiment meant to finally and really establish a European sovereignty, make Franco-German war impossible, and emancipate Europe from the “exorbitant privilege” of the U.S. dollar.[8] This was a rare example of visionary, almost transcendental politics, at least by the standards of these otherwise lifeless bourgeois regimes concerned with no more than money-chasing (although, characteristically, this materialistic ambition largely reduced “European unity” to . . . money, and was based on the lie that this would increase GDP, and hence, lead to more money). The French also persistently pushed to create a “Europe de la défense” as a rival to NATO in the 1990s, but in practice this rather nebulous concept amounted to a few, mostly minor, EU military operations and more-or-less inspired multilateral military-industrial projects.

Thus, many of the specifics of European integration were not designed by the Americans, notably on agricultural and monetary[9] policies, but rather reflected Franco-German compromise. More broadly the project is also one of Europe’s indigenous national bourgeoisies seeking to rationalize relations between their capitalist economies.

Apologists of the European Union then argue that it is a genuinely independent power. This has often been grossly exaggerated, no doubt in a crude attempt to legitimize the entity and dull Europeans’ awareness of their rapid and programmed decline in power and influence around the world.[10] Nonetheless, there is truth to the EU’s claims of economic power as a trade bloc, wherever there is consensus. This has arguably given Europeans certain advantages of scale not available to their smallish nation-states. American and Asian companies must respect the Common Market’s regulations (consumer, health, environmental . . .). Brussels directly negotiates trade agreements with other capitals (notably with Washington[11]), conducts anti-dumping/anti-subsidy investigations against China, and imposes sanctions against Russia. Finally, even the largest multinationals (Google, Goldman Sachs . . .) may fear the injunctions and potential multi-billion euro fines of the European Commission’s Competition authorities.

Most significantly, the EU has occasionally used its power against U.S. interests. In 2001, the European Commission blocked the merger of GE and Honeywell, two American firms, to prevent an aerospace oligopoly. The firms respected this ruling, despite the fact that U.S. authorities had approved the merger, so as to not be excluded from the European market. In 2002, the EU retaliated against U.S. tariffs on steel, leading the Bush Administration to back down the following year. What’s more, the euro has emerged as a rival reserve currency to the U.S. dollar[12] and has been used as a trading currency by various anti-American regimes – such as Cuba, North Korea, and Syria – instead of the dollar. The EU is also financing Galileo, a satellite navigation project meant to give Europeans strategic autonomy from America’s Global Positioning System. The European Union is then not wholly American in its origins and has taken some, albeit modest, anti-American actions.

“The small, miserable Europe of today”

On the whole however, we would have to admit that the European Union’s achievements as a Weltmacht, especially with regard to independence from the U.S., are a very thin gruel indeed. In practice, the EU’s theoretical status as “soft economic superpower” (if that is not already a contradiction in terms) is mitigated by the fact that the participating nation-states are ultimately sovereign, insofar as they have armies and administrations, and so could in principle withdraw or disobey at any time.

The European Union then functions somewhat like the United States did under the Articles of Confederation, the German Confederation, or the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth under the liberum veto. No consensus – because a foreign power (the U.S., China, Russia . . .) bribes or intimidates a national government to provide a veto or because of any national unilateral action – and the thing falls into irrelevance or outright collapse. One wonders what Carl Schmitt would have made of all this . . .

A rather miserly form of “power” indeed. Belgian Rexist leader and Volksführer der Wallonen Léon Degrelle’s assessment [2] from the 1970s appears as relevant as ever: “The small, miserable Europe of today, of this impoverished Common Market, cannot give happiness to men.” Again a National Socialist critique, in a single sentence, gets to the heart of a problem and cuts through so much of the turgid theological prose to be found in “EU studies.”

What’s more, the singular attempt to create a kind of European sovereignty, the euro, has thus far proved a continuous embarrassment and at times even an existential problem. In practice, while the European Central Bank is in some respects a worthy rival to the U.S. Federal Reserve, the Eurozone ultimately has thus far increased Europeans’ dependency on financial markets and vulnerability to speculation by Wall Street, the City of London, and others. The Eurozone has neither the solidary community of a nation nor the power and responsibility of a state. Instead, there is a kind of perpetual leaderless chaos and constant recrimination between peoples. An anti-Führerprinzip and anti-Volksgemeinschaft, if you will. This is indeed a startling illustration of the power and relevance of the nation-state.

America: Forger of “European” Consensus

The European Union – often termed an usine à gaz – is then little more than an enabler and reflection of consensus among its nation-states. But what shapes the cultural and political consensus in Europe? It is obvious that, above all, cultural and political consensus in Europe, insofar as these exist, has been largely shaped by American military, cultural, and diplomatic power. This is evident both historically and up to the present day.

Above all, it is the United States – in alliance with Joseph Stalin to whom Franklin Roosevelt gave half of Europe at Yalta – which destroyed the native French and German governments during the Second World War and imposed bourgeois and anti-nationalist regimes. The Gaullo-Communist coalition won the “Franco-French civil war” against the French State of Vichy on the back of Anglo-American bombing and invasion, purging the Right in France. The Allies “reeducated” the Germans towards anti-Nazism and self-hatred through a systematic campaign of total war against the German people (including incineration of hundreds of thousands of innocent civilians, the ethnic cleansing of 9 million Germans, the mass rape of German women, systematic political persecution of National Socialists and historical revisionists, and ongoing military occupation). The corrupt French Fourth Republic and the traumatized German Federal Republic, both born from the loins of a corrupted America, founded the European Communities on a particular anti-national and Atlanticist basis at the instigation of U.S.-funded agents like Jean Monnet and in the shadow of the Soviet threat.

In fact, the immediate postwar regimes of Europe – while formally “antiracist” – only fully lost their ethnic consciousness over many years.[13] This reflected the steady rise of the blank-slatist, individualist-egalitarian, and multiculturalist Left, on the back of the ’60s cultural revolution and American cultural power. This modern liberalism is a kind of auto-immune disorder: Europeans’ otherwise healthy instinct to purge “the bad,” necessary in any society, is channeled against those very people, patriots, who would preserve the organic integrity of their societies. This ideology – whatever weight one ascribes in its origins to indigenous French and American liberal trends or to Jewish cultural power[14] – has metastasized and achieved a certain autonomy in the European Union, and in particular in the Western states, as synonymous with the fameux “European values.”

The United States is, depressing as this may be, the single biggest contributor to “cultural consensus” among European nations today, through the profound influence in both elite and mass culture of Hollywood, the Ivy Leagues, pop music, prestigious print publications, and so on. Common European culture today stems not from our Greco-Roman and Indo-European myths, not from Christian religion and the churches, not even from our Renaissance and Enlightenment philosophy, but from the lowest American culture, produced by a notoriously deceitful elite. Nor is our common culture provided by Europe’s official multilateral cultural projects like the Franco-German TV channel Arte and the channel Euronews, which have markedly limited audiences. The steady, and now almost complete, rise of English as the European lingua franca, however useful the language of Shakespeare might otherwise be, has also furthered Anglo-American cultural hegemony.

Indeed, the center-left Jewish historian Tony Judt has observed that the Shoah has emerged as the central focal point of historical remembrance in Western European nations:

Far from reflecting upon the problem of evil in the years that followed the end of World War II, most Europeans turned their heads resolutely away from it. [. . .] Today, the Shoah is a universal reference. The history of the Final Solution, or Nazism, or World War II is a required course in high school curriculums everywhere. Indeed, there are schools in the US and even Britain where such a course may be the only topic in modern European history that a child ever studies. There are now countless records and retellings and studies of the wartime extermination of the Jews of Europe: local monographs, philosophical essays, sociological and psychological investigations, memoirs, fictions, feature films, archives of interviews, and much else. Hannah Arendt’s prophecy would seem to have come true: the history of the problem of evil has become a fundamental theme of European intellectual life.[15]

This centrality – which not coincidentally serves to stigmatize European ethno-nationalisms everywhere and apologize for Jewish ethno-nationalism in Israel and Jewish privilege in general – unquestionably reflects both American victory in the Second World War and the influence of American culture, rather than indigenous European trends.

Finally, the United States shapes the political consensus in the European Union through its unparalleled diplomatic power. Washington thus can typically block any major joint European action against American or Israeli interests (see the divided European reaction over the 2003 Iraq War and the failure to pass significant EU sanctions against Israel). What’s more, to the extent Europeans do adopt a common foreign policy, this tends to be shepherded by Washington and thus serve American geopolitical imperatives (e.g. the still-existing project of Turkish EU membership and the EU sanctions against Iran and Russia).

Conclusion: Towards a European Europe

The European Union then is not a counterweight to American power and, on the contrary, substantially reflects a European political consensus shaped by the United States. All that said, the history of the EU makes me rather optimistic about the prospects for our Continent if only the American Empire’s influence could be eliminated and we could become psychologically and culturally sovereign. Then Europeans would actually start thinking about their survival, rather than dully going along with their decline on the back of Hollywoodian propaganda and the false sense of security provided by NATO.

Europe alone, I dare to hope, would be able to forge a new cultural consensus[16] which would allow us to flourish again. We can easily imagine a new Europe in which our nations would organize to defend their sovereignty, notably in the economic sphere, to create cultural projects promoting European civilization and pride (a retooled Arte), to create a genuine European spiritual and cultural elite (a reformed Erasmus student exchange program going beyond an academic pretext for drunkenness abroad), and to use the European ingenuity of Airbus to defend our southern borders rather than those of corrupt Arab oligarchs [4]. Yes, the European is a creative breed and, once he identifies a problem, few are so idealistic and ingenious in reaching solutions.

Notes

1. See Guillaume Durocher, “Is the EU ‘racist’?: Implicitly White Themes in EU Ideology & Propaganda,” North American New Right, July 2, 2015. http://www.counter-currents.com/2015/07/is-the-eu-racist/ [5]

2. This theme has been most successfully popularized in France by the anti-EU and anti-American nationalist François Asselineau, who leads the Union Populaire Républicaine. Asselineau has also sought to portray the EU as a kind of crypto-Nazi construct on the grounds that Walter Hallstein, the first president of the European Commission, was a “Nazi lawyer” under the Third Reich . . . See also Guillaume Durocher, “Is the EU ‘fascist’?,” North American New Right, June 15, 2015. http://www.counter-currents.com/2015/06/is-the-eu-fascist/ [6]

3. Another prominent miscegenationist theory was that of Mexican thinker and politician José Vasconcelos who called for the creation of la Raza Cósmica, a kind of a super-race composed of the best of European, African, and Asian blood. Vasconcelos believed that European blood would be more prominent in such a race. This theory can be considered a mystical rationalization for Mexico as a failed nation and continues to lend its name to the National Council of La Raza, the leading Hispanic ethnic lobby. See also Matt Parrot, “Cosmic America,” North American New Right, December 13, 2010. http://www.counter-currents.com/2010/12/cosmic-america/ [7]

4. Monnet’s American connections and the wider context of the heady days of postwar European federalism are discussed in detail in Richard J. Aldrich, “OSS, CIA and European unity: The American committee on United Europe, 1948-60,” Diplomacy & Statecraft, 8:1, March 1, 1997, 184-227. http://www2.warwick.ac.uk/fac/soc/pais/people/aldrich/publications/oss_cia_united_europe_eec_eu.pdf [8]

5. Gabriele Cipriani, “Financing the EU Budget: Moving Forwards or Backwards,” Centre for European Policy Studies (2014), 5. http://www.ceps.eu/system/files/Financing%20the%20EU%20budget_Final_Colour.pdf [9]

6. In this respect, we can also cite French semi-withdrawal from NATO, eviction of U.S. troops from French soil, and the creation of an independent French strategic nuclear deterrent (the force de frappe) – that at least France might survive the eventual Soviet-American nuclear war.

7. Francis Parkey Yockey, “The World in Flames: An Estimate of the World Situation,” February 1961. http://www.counter-currents.com/2011/07/the-world-in-flames-an-estimate-of-the-world-situation/ [10]

8. Discussed at length in Guillaume Durocher, “François Mitterrand: European Statesman, anti-American, & Judeophobe,” North American New Right, August 18, 2015. http://www.counter-currents.com/2015/08/francois-mitterrand/ [11]

9. Indeed, elite American economic commentators – whom we have to observe are largely Jewish – were overwhelmingly skeptical and even bemused by the Eurozone project, which we might deem to be yet another example of typically goyishe impractical idealism.

10. The postwar founders of the European Communities had incredible “federalist” pretensions despite an almost total lack of sovereign powers, their resources being reduced to the good will of national governments, U.S. support, and a secretariat in Brussels. Unbelievably overstated claims of the EU’s power and influence as a Weltmacht have been made in recent years, typically by Atlanticist pundits and professors who know they will be rewarded for going with the grain and flattering Eurocratic pretensions. See for example, Mark Leonard, Why Europe Will Run the Twenty-First Century (Public Affairs, 2006) and Andrew Moravcsik, “Europe, the Second Superpower,” Current History, March 10. https://www.princeton.edu/~amoravcs/library/current_history.pdf [12]

11. Namely with the famous Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP), formerly known as TAFTA, which has attracted opposition from a wide array of leftists and nationalists, seeming to revive an old undercurrent of anti-Americanism in Europe for whom the U.S. is synonymous with unbridled corporate power and capitalist materialism. This same undercurrent has driven opposition to genetically-modified organisms (GMOs) and the “investment firm” Goldman Sachs. Incidentally, in one of his more inspired moments, Bernard-Henri Lévi argued that Danish opposition to Goldman Sachs was “anti-Semitic” and indeed has argued that anti-Americanism in general is “anti-Semitic” . . .

12. The euro is today a distant second to the U.S. dollar as reserve currency, but nonetheless far ahead of any other.

13. In particular, President de Gaulle privately justified the abandonment of French Algeria on ethno-nationalist grounds, arguing that France could never assimilate tens of millions of Arabs. He remarked that Frenchmen and Arabs would never mix: “Try to integrate oil and vinegar.”

In West Germany, postwar leaders encouraged ethnic German immigration (Aussiedler) back to the fatherland and were highly skeptical of Turkish immigration, with Chancellor Helmut Kohl even having a proposal of halving the Turkish population in Germany through remigration. See Guillaume Durocher, “Merkel’s Betrayal: From the Ethno-National Principle to Afro-Islamized Germany,” The Occidental Observer, September 16, 2015. http://www.theoccidentalobserver.net/2015/09/merkels-betrayal-from-the-ethno-national-principle-to-an-afro-islamic-germany-part-1/ [13]

14. See the pioneering work of Professor Kevin B. MacDonald: The Culture of Critique: An Evolutionary Analysis of Jewish Involvement in Twentieth-Century Intellectual and Political Movements (1st books library: 2002) and “Understanding Jewish Influence I: Background Traits for Jewish Activism.” http://www.kevinmacdonald.net/understandji-1.htm [14]

15. Tony Judt, “The ‘Problem of Evil’ in Postwar Europe,” The New York Review of Books, February 14, 2008. http://www.nybooks.com/articles/archives/2008/feb/14/the-problem-of-evil-in-postwar-europe/ [15]

16. Incidentally, there is a precedent in European Christendom, which created a cultural consensus among European elites across nations and states. This was a powerful factor of unity, especially against Muslim invasions, whatever one thinks of the wider problems and long-term effects of Christian doctrine.

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

L’écrivain risqua sa vie pour libérer son pays de Mussolini dont il fut pourtant proche au départ. Lors d’un discours destiné aux soldats italiens qui combattaient le fascisme, il confie : « Le nom Italie puait dans ma bouche comme un morceau de viande pourrie. » L’écrivain refuse de s’attacher à un patriotisme aveugle et prend le recul nécessaire afin de discerner les tares de son propre pays qui se situent dans le fascisme ou dans le post-fascisme. Malaparte s’identifie davantage à la Rome antique et à la Renaissance qu’à l’Italie moderne. C’est un homme du passé obnubilé par la richesse culturelle et artistique que lui ont légué les temps anciens : le patriotisme moderne ne semble pas être fait pour lui, le présent le désespère et il ne croit pas en un avenir meilleur. Ce qu’il vit au présent est vulgaire et ignoble, pessimiste résolu et réactionnaire esthétique, il est tourné vers le passé car il est attiré par ce qui est raffiné.

L’écrivain risqua sa vie pour libérer son pays de Mussolini dont il fut pourtant proche au départ. Lors d’un discours destiné aux soldats italiens qui combattaient le fascisme, il confie : « Le nom Italie puait dans ma bouche comme un morceau de viande pourrie. » L’écrivain refuse de s’attacher à un patriotisme aveugle et prend le recul nécessaire afin de discerner les tares de son propre pays qui se situent dans le fascisme ou dans le post-fascisme. Malaparte s’identifie davantage à la Rome antique et à la Renaissance qu’à l’Italie moderne. C’est un homme du passé obnubilé par la richesse culturelle et artistique que lui ont légué les temps anciens : le patriotisme moderne ne semble pas être fait pour lui, le présent le désespère et il ne croit pas en un avenir meilleur. Ce qu’il vit au présent est vulgaire et ignoble, pessimiste résolu et réactionnaire esthétique, il est tourné vers le passé car il est attiré par ce qui est raffiné.

Vayamos por partes: de las siglas y las iniciativas que mencionas solamente hay dos que tengan un mínimo de actividad y peso, PxC y E2000. El resto son entelequias a las que falta incluso “principio de razón suficiente”: ¿Por qué existe una FE-LaFalange y no está dentro de una sigla común? ¿un Nudo qué es? ¿un partido, un círculo de amigos, qué fórmula legal tiene? ¿Pueden existir coaliciones de cuatro o cinco siglas sin un solo cargo electo y con apenas unos cientos de votos en donde cada parte sea celosa de su “independenci”? Absurdos, solo absurdos y nada más que absurdos con los que no vale la pena perder mucho tiempo. Ganará el partido que tenga los mejores cuadros, los más lúcidos, los mejor preparados, el equipo más dinámico y las ideas más claras: y en mi opinión solamente hay una fórmula, el eje PxC-E2000. Todo lo demás, es demasiado pequeño, oscilante e indefinido, o incluso meros arcaísmos.

Vayamos por partes: de las siglas y las iniciativas que mencionas solamente hay dos que tengan un mínimo de actividad y peso, PxC y E2000. El resto son entelequias a las que falta incluso “principio de razón suficiente”: ¿Por qué existe una FE-LaFalange y no está dentro de una sigla común? ¿un Nudo qué es? ¿un partido, un círculo de amigos, qué fórmula legal tiene? ¿Pueden existir coaliciones de cuatro o cinco siglas sin un solo cargo electo y con apenas unos cientos de votos en donde cada parte sea celosa de su “independenci”? Absurdos, solo absurdos y nada más que absurdos con los que no vale la pena perder mucho tiempo. Ganará el partido que tenga los mejores cuadros, los más lúcidos, los mejor preparados, el equipo más dinámico y las ideas más claras: y en mi opinión solamente hay una fórmula, el eje PxC-E2000. Todo lo demás, es demasiado pequeño, oscilante e indefinido, o incluso meros arcaísmos.  Con un 18-20% de la población de origen inmigrante, con el sistema de pensiones colapsado, con 5.000.000 de parados enquistados y un tercio de la población próxima al umbral de la pobreza o por debajo de ella, con un sistema educativo convertido en mero almacenamiento de alumnos, y posiblemente con un segundo estallido de la burbuja inmobiliaria (si miráis en torno a las grandes ciudades, vuelven a verse grúas trabajando, cuando aún quedan 2.500.000 de pisos sin vender…) y cuando las repercusiones de la segunda oleada de crisis de la globalización, la que está en estos momentos estallando en Brasil, afecte particularmente a las empresas de nuestro país… tal será el horizonte que tendremos en 2019.

Con un 18-20% de la población de origen inmigrante, con el sistema de pensiones colapsado, con 5.000.000 de parados enquistados y un tercio de la población próxima al umbral de la pobreza o por debajo de ella, con un sistema educativo convertido en mero almacenamiento de alumnos, y posiblemente con un segundo estallido de la burbuja inmobiliaria (si miráis en torno a las grandes ciudades, vuelven a verse grúas trabajando, cuando aún quedan 2.500.000 de pisos sin vender…) y cuando las repercusiones de la segunda oleada de crisis de la globalización, la que está en estos momentos estallando en Brasil, afecte particularmente a las empresas de nuestro país… tal será el horizonte que tendremos en 2019.

L'éloge du « silence des intellectuels » vantés par un des plus bavards - pour ne pas dire le plus baveux - d'entre eux prête à rire. Si Jean-Luc Nancy ne fréquente pas les plateaux de la télévision, il ne s'est en réalité jamais tu. La masse importante de ses publications, sans grande signification d'avenir et qui se vendent d'ailleurs déjà au kilo, en atteste largement. Effectivement, il est peu intervenu dans le débat public mais c'est que si Jean-Luc Nancy s'est tu depuis des années sur les affaires du monde, c'est qu'il a toujours consenti. Il a beau nous la jouer grand intellectuel dans son bureau au-dessus de la mêlée avec le leitmotiv d'Adorno au plafond, "plus de poésie après Auschwitz", il a en réalité toujours trouvé le temps d'écrire pour soutenir les pouvoirs en place.

L'éloge du « silence des intellectuels » vantés par un des plus bavards - pour ne pas dire le plus baveux - d'entre eux prête à rire. Si Jean-Luc Nancy ne fréquente pas les plateaux de la télévision, il ne s'est en réalité jamais tu. La masse importante de ses publications, sans grande signification d'avenir et qui se vendent d'ailleurs déjà au kilo, en atteste largement. Effectivement, il est peu intervenu dans le débat public mais c'est que si Jean-Luc Nancy s'est tu depuis des années sur les affaires du monde, c'est qu'il a toujours consenti. Il a beau nous la jouer grand intellectuel dans son bureau au-dessus de la mêlée avec le leitmotiv d'Adorno au plafond, "plus de poésie après Auschwitz", il a en réalité toujours trouvé le temps d'écrire pour soutenir les pouvoirs en place.

France and Algeria, of course, were joined at the hip in accordance with the Napoleonic doctrine of Algérie française. In the end, the division had to occur, but at least a million French Algerians, who were totally French of course, pieds noirs, black feet, came back from North Africa to live in the south of France where they became the bedrock for the Front National vote in the deep south of the country in generations to come.

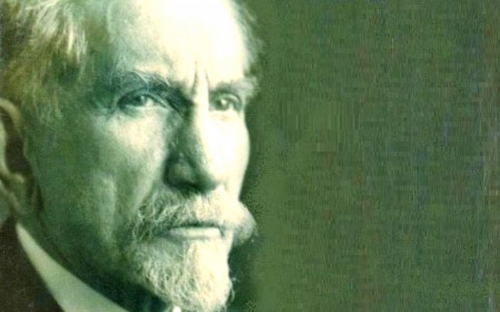

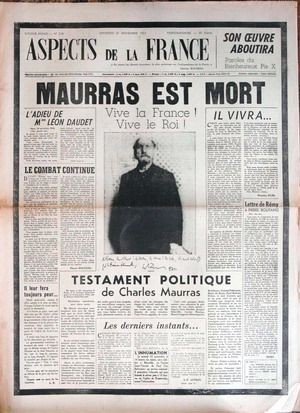

France and Algeria, of course, were joined at the hip in accordance with the Napoleonic doctrine of Algérie française. In the end, the division had to occur, but at least a million French Algerians, who were totally French of course, pieds noirs, black feet, came back from North Africa to live in the south of France where they became the bedrock for the Front National vote in the deep south of the country in generations to come. So, I think it falls upon us, as largely non-French people, to look back upon this traditionalist philosopher of the French radical Right with a degree of quiet appraisal. Maurras was a figure who could be admired as somebody who fought for his own country to the last element of his own breath. He was also somebody who’s own cultural dynamics were complicated and ingenious. To give one cogent example, the Greek play Antigone deals with the prospect of the punishment of a woman by Creon because she wishes to honor the death sacrifice of her brother. This becomes a conflict between the state and those who would seek to supplant the state’s momentary laws by laws which are regarded as matriarchal or affirmative with the chthonian or the fundamental in human life. George Steiner once commented in a book looking at the different varieties of Antigone that most critics of the Left have always supported her against Creon and most socially Right-wing commentators like T. S. Eliot have always supported Creon against Antigone. And yet Maurras supported Antigone against Creon, because she wished to bury her brother for reasons which were ancestral and chthonian and came up from under the ground and were primeval and were blood-related and were therefore more important and more profound than the laws that men had put together with pieces of parchment and bits of writing on paper.

So, I think it falls upon us, as largely non-French people, to look back upon this traditionalist philosopher of the French radical Right with a degree of quiet appraisal. Maurras was a figure who could be admired as somebody who fought for his own country to the last element of his own breath. He was also somebody who’s own cultural dynamics were complicated and ingenious. To give one cogent example, the Greek play Antigone deals with the prospect of the punishment of a woman by Creon because she wishes to honor the death sacrifice of her brother. This becomes a conflict between the state and those who would seek to supplant the state’s momentary laws by laws which are regarded as matriarchal or affirmative with the chthonian or the fundamental in human life. George Steiner once commented in a book looking at the different varieties of Antigone that most critics of the Left have always supported her against Creon and most socially Right-wing commentators like T. S. Eliot have always supported Creon against Antigone. And yet Maurras supported Antigone against Creon, because she wished to bury her brother for reasons which were ancestral and chthonian and came up from under the ground and were primeval and were blood-related and were therefore more important and more profound than the laws that men had put together with pieces of parchment and bits of writing on paper.