William A. Galston

Anti-Pluralism: The Populist Threat to Liberal Democracy

New Haven: Yale University Press, 2018

“It is time for an open and robust debate on issues of immigration, identity politics, and nationalism that liberals and progressives have long avoided.”—William Galston

Galston is right. I will debate any liberal or progressive about these topics, and if they don’t want to debate me, I will help arrange a debate with whomever they prefer. Contact me at editor@counter-currents.com [2].

William Galston (born 1946) has had a long career spanning both political theory and practice. He received his Ph.D. in political theory from the University of Chicago and has strong Straussian credentials, although he aligns himself with the center-Left, not the neocons. (Arguably, this is a distinction without a difference.) Galston has taught in the political science departments of the University of Texas at Austin and the University of Maryland. He is now affiliated with the centrist Brookings Institution. Galston has worked for the presidential campaigns of John Anderson, Walter Mondale, Bill Clinton, and Al Gore. He was deputy assistant for domestic policy in the Clinton White House from January 1993 to May 1995.

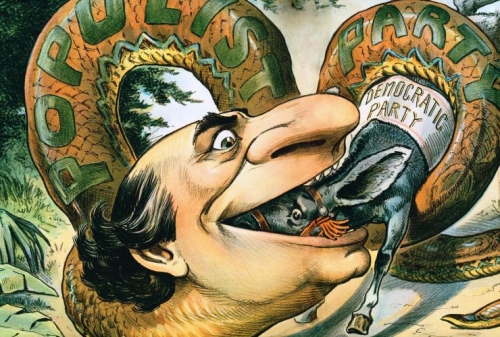

Galston’s Anti-Pluralism: The Populist Threat to Liberal Democracy presents itself as a “liberal-democratic” centrist polemic against the populist Right, in much the same vein as Francis Fukuyama’s Identity: Contemporary Identity Politics and the Struggle for Recognition (2018, see my review here [3], here [4], and here [5]) and Mark Lilla’s The Once and Future Liberal: After Identity Politics (2017, see my review here [6]).

But Galston, like Fukuyama and Lilla, received a Straussian education, so chances are good that his arguments are not entirely straightforward. Indeed, all three books can also be read as polemics against the Left, since they argue that Left-wing excesses are the driving force behind the rise of Right-wing populism. Therefore, if the “liberal democratic” establishment wishes to take the wind out of the sails of Right-wing populism, it needs to rein in the excesses of the far Left.

Galston’s theoretical account of liberal democracy is pretty much standard centrist boilerplate. His theoretical account of populism depends heavily of Jan-Werner Müller’s extremely flawed book What Is Populism?, which I have reviewed [7] already.

For Galston, following Müller, liberal democracy is essentially “pluralist” and populism is “anti-pluralist.” By this, he does not mean that liberal democracies recognize that every healthy society balances the needs of the family, civil society, and the state. Nor does he mean that a healthy polity has differences of opinion that might express themselves in a plurality of political parties. Nor does he mean that a healthy society has different classes. Nor does he mean the separation of powers or the mixed regime. Populists can embrace all those forms of pluralism, but without liberalism.

Instead, for Galston and Müller, pluralism just means “diversity,” i.e., the presence of minorities, which he describes as “helpless” and in need of protection from the tyranny of the majority. By “minorities,” Galston doesn’t mean the people who lose a vote—a group that changes with every vote—but rather more fixed minorities, such as social elites and ethnic minorities.

But what if some minorities are not helpless but actually dangerously powerful? What if liberal democracy has long ceased to be majority rule + protection for minorities? What if liberal democracy has become, in effect, minority rule? What if these ruling minorities are so hostile to the majority that they have enacted policies that not only economically pauperize them, but also destroy their communities with immigration and multiculturalism, and, beyond that, seek their outright ethnic replacement? Liberal democracy is really just a euphemism for minority rule, meaning rule by hostile elites. Naturally, one would expect some sort of reaction. That reaction is populism.

Galston understands this. He recognizes the four major trends that Roger Eatwell and Matthew Goodwin argue are responsible for the rise of populism in their book National Populism: Revolt Against Liberal Democracy: popular distrust of elites, the destruction of communities by immigration and multiculturalism, the economic deprivation—falling largely on the working-class and middle-class—caused by globalization, and the consequent political dealignments in relation to the post-war center-Left/center-Right political establishment. (See my discussions of Eatwell and Goodwin here [8], here [9], and here [10].)

In his Introduction, Galston notes that “The people would defer to elites as long as elites delivered sustained prosperity and steadily improving living standards” (p. 2). Galston actually describes elitism as a “deformation” of liberal democracy: “Elitists claim that they best understand the means to the public’s ends and should be freed from the inconvenient necessity of popular consent” (p. 4).

People stopped trusting elites when economic globalization, immigration, and multiculturalism started making life worse, and not just economically but also in terms of culture and public safety (crime, terrorism): “A globalized economy, it turned out, served the interests of most people in developing countries and elites in advanced countries—but not the working and middle classes in the developed economies . . .” (p. 3). “Not only did immigrants compete with longtime inhabitants for jobs and social services, they were also seen as threatening long-established cultural norms and even public safety” (p. 3).

Galston outlines how our out-of-touch, hostile, increasingly panicked establishment can head off populism before it leads to genuine regime change:

. . . there is much that liberal democratic governments can do to mitigate their insufficiencies. Public policy can mitigate the heedlessness of markets and slow unwanted change. Nothing requires democratic leaders to give the same weight to outsiders’ claims as to those of their own citizens. They are not obligated to support policies that weaken their working and middle classes, even if these policies improve the lot of citizens in developing countries. They are certainly not obligated to open their doors to all newcomers, whatever the consequences for their citizenry. Moderate self-preference is the moral core of defensible nationalism. Unmodulated internationalism will breed—is breeding—its antitheses, an increasingly unbridled nationalism. (p. 5)

The Left, of course, has no problem using public policy to rein in markets, but they vehemently reject Galston’s “moderate self-preference,” which is what some people would call putting “America first.” The American Left is committed to open borders, which will pauperize the American middle and working classes as surely as Republican deindustrialization and globalization.

In chapter 6, “Liberal Democracy in America: What Is to Be Done?,” Galston recommends prioritizing economic growth and opportunity and making sure it is widely shared by everyone. The “second task requires pursuing three key objectives: adopting full employment as a principal goal or economic policy; restoring the link between productivity gains and wage increases; and treating earned and unearned income equally in our tax code” (p. 87). In effect, Galston proposes halting the decline of the American middle class that has been ongoing for nearly half a century by ensuring that productivity gains go to workers, not just capitalists. As a populist, these are policies that I can support.

Galston also suggests that a corrective to the decline in labor unions and worker bargaining power due to globalization can be offset by measures to “democratize capital through . . . worker ownership of firms, that share the gains more broadly” (p. 99).

Of course productivity can be raised in two ways: by making labor more productive through technological and organizational improvements—or simply by cost-cutting. Practically all the “productivity” gains of globalization are simply due to cost-cutting by replacing well-paid white workers with poorly paid Third Worlders, either by sending factories overseas or by importing legal and illegal immigrants. If public policy is to promote genuine economic growth, it needs to promote genuine increases in productivity, which means technological innovations, as well as better education and all-round infrastructure.

But technology doesn’t just make workers more productive. It also puts them out of work. However, if workers have no incomes, then they cannot purchase the products of automation. (Production can be automated, but consumption can’t.) So how can we maintain technological growth, a healthy middle class, and consumer demand at the same time? Galston points to a partial solution:

. . . the public should get a return on public capital the benefits of which are now privately appropriated. When the government funds basic research that leads to new medical devices, the firms that have relied on this research should pay royalties to the Treasury. When states and localities invest in infrastructure that raises property values and creates new business opportunities, the taxpayers should receive some portion of the gains. One might even imagine public contributions to a sovereign wealth fund that would invest in an index of U.S. firms and pay dividends to every citizen. (p. 99)

The key point is that when machines put us out of work, we should not fall into unemployment but rise into the class of people who live on dividends. A more direct route to the same outcome would be to adopt Social Credit economics, including a dividend or Universal Basic Income paid to every citizen. (For more on this, see my essay, “Money for Nothing [11].”)

Galston does not mention simple, straightforward protectionism, but there are sound arguments for it, and the arguments against it have been refuted. (See Donald Thoresen’s review [12] of Ian Fletcher’s Free Trade Doesn’t Work.)

The bad news for National Populists is that Galston’s proposals, if actually adopted, would significantly retard our political success. The good news is that Galston’s proposals are simply what Eatwell and Goodwin call “National Populism lite,” which means that Galston is abandoning globalism in principle. What he refuses to abandon is the existing political establishment, which he thinks will retain power only by abandoning globalism.

Another piece of good news is that the establishment will probably never listen to Galston. They are fanatically committed to their agenda. They are not going to drop their commitment to globalism in favor of nationalism, even if it is the only way to preserve themselves. Galston is trying to appeal to the rational self-interest of the existing elites. But they are not rational or even especially self-interested. Sometimes people hate their enemies more than they love themselves. But National Populists would implement Galston’s policies, and more. So perhaps he is rooting for the wrong team.

A third piece of good news is that Galston realizes that economic reforms are not enough. Galston also cites studies showing that populist Brexit and Trump voters were not motivated solely by economic concerns (pp. 76–77). They were also motivated by concerns about identity. Since Galston is talking primarily about white countries, National Populism is a species of white identity politics. Since Left-wing populism rejects nationalism and white identity politics (and only white identity politics), it can only address white voters on economic issues, which means that it has less electoral appeal than Right-wing populism.

As I never tire of pointing out, what people want is a socially conservative, nationalistic, interventionist state that will use its power to protect the working and middle classes from the depredations of global capitalism. The elites, however, want social liberalism and globalism both in politics and economics.

The two-party system is designed to never give the people what they want. The Republicans stand for conservative values and global capitalism. The Democrats stand for liberal values and the interventionist state. When in power, the parties only deliver what the elites want, not what the people want.

The consequence is neoliberalism: an increasingly oligarchical hypercapitalist society that celebrates Left-wing values. Galston offers interesting support for this thesis by quoting Bo Rothstein, “a well-known scholar of European social democracy” who argues (these are Rothstein’s words) that “The more than 150-year-old alliance between the industrial working class and the intellectual-cultural Left is over” (p. 103). Rothstein elaborates:

The traditional working class favors protectionism, the re-establishment of a type of work that the development of technology has rendered outdated and production over environmental concerns; it is also a significant part of the basis of the recent surge in anti-immigrant and even xenophobic views. Support of the traditional working class for strengthening ethnic or sexual minorities’ rights is also pretty low. (p. 103)

Since the Left’s values are the “exact opposite,” Rothstein proposes that the Left ally with the “new entrepreneurial economy.” Hence the marriage of some of the biggest corporations on the planet—Facebook, Apple, Amazon, Microsoft, Google—with trannies, POCs, Muslims, feminists, and global warming fantasists. This coalition thinks it will win through replacing the white working and middle classes with non-whites. Galston notes that Democratic Party circles in the US hold essentially the same views:

The best known have based their case on long-cycle demographic shifts. There is a “rising American electorate” made up of educated professionals minorities, and young people, all groups whose share of the electorate will increase steadily over the next two generations. These groups represent the future. The white working class, whose electoral share has dwindled in recent decades and will continue to do so, is the past. This does not mean that the center-left should ignore it completely. [For instance, on economic matters.] It does mean that there should be no compromise with white working-class sentiments on the social and cultural issues that dominate the concerns of the rising American electorate coalition. (p. 103)

This is a crystal-clear statement of the White Nationalist thesis that the Left is counting on—and promoting—the slow genocide of whites [13] through race-replacement immigration in order to create a permanent Left-wing majority. What could possibly go wrong? Galston drily notes that “This was the theory at the heart of Hillary Clinton’s presidential campaign.”

Obviously, there was going to be a reaction. The Left has been partying like whites are already a minority, but that’s not true yet. White demographic decline is obviously a serious threat if we do nothing about it. But there is nothing inevitable about white demographic decline. It is the product of particular political policies. Thus it can be reversed by different policies. And, as Eatwell and Goodwin argue in National Populism, we still have some decades to turn things around, although of course the time frame varies from country to country. Furthermore, National Populist political movements, once they break through, are highly competitive because, unlike the center-Left and center-Right, we will actually give the people what they want, for a change.

Galston is well aware that the center-Left cannot compete with National Populists on economic ground alone:

If concessions on cultural and social issues are ruled out, appeals to the white working class will have to be confined to economics. . . . The difficulty, as we have seen, is that the audience for this economic appeal cares at least as much about social and cultural issues. Immigration, demographic change, and fears of cultural displacement drove the Brexit vote, and they were the key determinants of Donald Trump’s victory. . . .

So the American center-left has a choice: to stand firm on social and cultural issues that antagonize populism’s most fervent supporters, or to shift in ways for which it can offer a principled defense. It is time for an open and robust debate on issues of immigration, identity politics, and nationalism that liberals and progressives have long avoided. (pp. 103–104)

Galston is absolutely correct here. The Left will not win by bread alone. It needs to address questions of values and identity. But it can’t really do so without abandoning its own values and identity. We really do need open and honest debate on immigration, identity politics, and nationalism, but the Left cannot permit this, because they know they’ll lose.

Galston also recognizes that tribal sentiments—meaning a preference for one’s own—are an ineradicable part of human nature. Because of this, “The issue of national identity is on the table, not only in scholarly debates, but also in the political arena. Those who believe that liberal democracy draws strength from diversity have been thrown on the defensive. Large population flows . . . have triggered concerned about the loss of national sovereignty” (p. 95).

Galston approvingly quotes Jeff Colgan and Robert Keohane’s statement that “It is not bigotry to calibrate immigration levels to the ability of immigrants to assimilate and to society’s ability to adjust” (p. 96). Of course, assimilation is the opposite of multiculturalism. Galston suggests that US immigration policies should shift toward meritocratic concerns about economic contribution, put increasing emphasis on English fluency, and demand greater knowledge of American history and institutions. The main virtue of these proposals is that they would dramatically decrease the numbers of immigrants (p. 96). I heartily agree with Galston’s final remarks on immigration:

One thing is clear: denouncing citizens concerned about immigration as ignorant and bigoted (as former British prime minister Gordon Brown did in an ill-fated election encounter with a potential supporter) does nothing to ameliorate either the substance of the problem or its politics. (p. 96)

But again, Leftists are unlikely to take Galston’s advice. If the Left moved away from moralistic condemnations of immigration skepticism and actually debated the topic, they would simply lose. Indeed, one of the reasons why the Left supports race-replacement immigration is because they have given up on convincing white voters and simply wish to replace them.

Galston also chides Leftists for their arrogance. One of the strongest predictors of Left-wing values is the amount of time people spend in higher education, especially the liberal arts and social sciences. This does not mean that such people are genuinely educated, of course, but they are flattered into thinking they are more enlightened and intelligent than ordinary people, which feeds into populism:

Put bluntly, if Americans with more education regard their less educated fellow citizens with disrespect, the inevitable response of the disrespected will be resentment coupled with a desire to take revenge on those who assert superiority. . . . elites have a choice: they can try to take the edge off status differences or they can flaunt them. . . . It is up to privileged Americans to take the first step by listening attentively and respectively to those who went unheard for far too long. (p. 102)

Galston is right, of course, but there is little likelihood that this recommendation—or any of his others—will be heeded. The pretense of intellectual superiority, no matter how hollow, is close to the core of Leftist identity. To win by abandoning one’s identity feels like losing to most people. Thus they will tend to hold fast to their identities and hope that somehow reality will accommodate their wishes.

William Galston is a perceptive, rational, and courageous writer. I can’t help but respect him, even though he is on the other side. He is a liberal democrat. I am an illiberal democrat. He wants to preserve the current establishment. I don’t. Given that the current establishment has fundamentally betrayed our people—with the Left openly pinning its hopes on the slow genocide of whites and the Right too stupid and cowardly to stop it—we need genuine regime change.

Even though Anti-Pluralism is a critique of National Populism, I find it a highly encouraging book. Rhetorically, the book was often cringe-inducing. Evidently Galston thinks that to communicate difficult truths to liberals, they need a great deal of buttering up. But in terms of its substance, Galston—like Fukuyama and Lilla—concedes many fundamental premises to National Populists, and the only way he can envision stopping National Populism and keeping the existing political establishment in power is by adapting National Populism lite. In short, he has all but conceded us the intellectual victory. Our task is now to achieve it on the political plane.

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

La théorie moderne de l’État

La théorie moderne de l’État Union européenne et Confédération d’États. De la guerre inter-étatique à la "guerre civile mondiale"

Union européenne et Confédération d’États. De la guerre inter-étatique à la "guerre civile mondiale" Le "pluriversum" comme nouvel ordre planétaire

Le "pluriversum" comme nouvel ordre planétaire Schmitt, en excluant toute conception universaliste du droit international parvient à la conclusion que l'ordre du monde ne peut se réaliser sans antagonismes entre les grands espaces, ou sans la domination d'un centre sur sa périphérie. Toutefois il reconnaît l'exigence d'une autorité supérieure, en mesure de trancher sur les différends et les tensions entre forces régulières et irrégulière, intérieures et extérieures. Il est incontestable que l’État moderne se distingue de tous les autres, pour avoir dompté, à l'intérieur de ses frontières, la relation ami-ennemi , sans l'avoir totalement supprimée.

Schmitt, en excluant toute conception universaliste du droit international parvient à la conclusion que l'ordre du monde ne peut se réaliser sans antagonismes entre les grands espaces, ou sans la domination d'un centre sur sa périphérie. Toutefois il reconnaît l'exigence d'une autorité supérieure, en mesure de trancher sur les différends et les tensions entre forces régulières et irrégulière, intérieures et extérieures. Il est incontestable que l’État moderne se distingue de tous les autres, pour avoir dompté, à l'intérieur de ses frontières, la relation ami-ennemi , sans l'avoir totalement supprimée. Ce dilemme et cette problématique rapprochent Schmitt et Kissinger, au delà de leur plaidoirie respective en faveur de l'Allemagne ou des Etats- Unis.

Ce dilemme et cette problématique rapprochent Schmitt et Kissinger, au delà de leur plaidoirie respective en faveur de l'Allemagne ou des Etats- Unis.

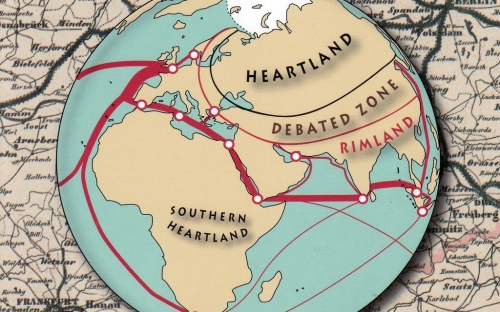

Spykman est un personnage assez fascinant. De nombreux auteurs de géographie politique le classent parmi les géopoliticiens « matérialistes », uniquement préoccupés de quantification des facteurs de force, en particulier militaires, et obnubilés par les déterminismes liés à la localisation des acteurs étatiques.

Spykman est un personnage assez fascinant. De nombreux auteurs de géographie politique le classent parmi les géopoliticiens « matérialistes », uniquement préoccupés de quantification des facteurs de force, en particulier militaires, et obnubilés par les déterminismes liés à la localisation des acteurs étatiques. L’interdépendance économique est certes une réalité. Elle l’était aussi à la veille de 1914.

L’interdépendance économique est certes une réalité. Elle l’était aussi à la veille de 1914. Dans son récent essai, L’affolement du monde, Thomas Gomart dit que nous vivons un moment « machiavélien », au sens où l’analyse des rapports de force, qui était passée au second plan à l’ère des grandes conférences sur le désarmement, reprend une importance fondamentale dès lors que les trois principales puissances, Etats-Unis, Russie et Chine, réarment comme jamais. Après avoir contribué à stabiliser le monde, ce que le général Gallois appelait « le pouvoir égalisateur de l’atome » est-il en train de devenir obsolète ?

Dans son récent essai, L’affolement du monde, Thomas Gomart dit que nous vivons un moment « machiavélien », au sens où l’analyse des rapports de force, qui était passée au second plan à l’ère des grandes conférences sur le désarmement, reprend une importance fondamentale dès lors que les trois principales puissances, Etats-Unis, Russie et Chine, réarment comme jamais. Après avoir contribué à stabiliser le monde, ce que le général Gallois appelait « le pouvoir égalisateur de l’atome » est-il en train de devenir obsolète ? Du point de vue des apprentissages, la « géopolitique » n’y fera rien, ni l’économie, ni la « communication ».

Du point de vue des apprentissages, la « géopolitique » n’y fera rien, ni l’économie, ni la « communication ».

È un grande giurista del diritto pubblico e del diritto internazionale, che ha avuto il dono di un pensiero veramente radicale, e la sorte di vivere in un secolo di drammatici sconvolgimenti intellettuali, istituzionali e sociali. Ciò ne ha fatto anche un grande filosofo e un grande scienziato della politica; e lo ha esposto a grandi sfide e a grandi errori.

È un grande giurista del diritto pubblico e del diritto internazionale, che ha avuto il dono di un pensiero veramente radicale, e la sorte di vivere in un secolo di drammatici sconvolgimenti intellettuali, istituzionali e sociali. Ciò ne ha fatto anche un grande filosofo e un grande scienziato della politica; e lo ha esposto a grandi sfide e a grandi errori. Schmitt pensa – e lo spiega in tutta la sua produzione internazionalistica, dal 1926 al 1978 – che ogni universalismo e ogni negazione della originarietà del nemico siano un modo indiretto per far passare una inimicizia potentissima moralisticamente travestita, per generare guerre discriminatorie. Per ogni universalismo chi vi si oppone è un nemico non concreto e reale ma dell’umanità: un mostro da eliminare. Perché ci sia pace ci deve essere la possibilità concreta del nemico, non la sua criminalizzazione, secondo Schmitt.

Schmitt pensa – e lo spiega in tutta la sua produzione internazionalistica, dal 1926 al 1978 – che ogni universalismo e ogni negazione della originarietà del nemico siano un modo indiretto per far passare una inimicizia potentissima moralisticamente travestita, per generare guerre discriminatorie. Per ogni universalismo chi vi si oppone è un nemico non concreto e reale ma dell’umanità: un mostro da eliminare. Perché ci sia pace ci deve essere la possibilità concreta del nemico, non la sua criminalizzazione, secondo Schmitt. Carl Schmitt si è spento nel 1985 a Plettenberg in Westfalia alla veneranda età di 97 anni. Ciò significa che il suo sguardo non supera la «cortina di ferro» e si estende solo alla realtà della guerra fredda. Anche durante questo delicato periodo Schmitt ha continuato la sua attività di studioso e attento indagatore delle questioni di diritto internazionale dei suoi anni. Si espresse quindi sul dualismo USA-URSS, vedendo in esso una tensione verso l’unità del mondo nel segno della tecnica che avrebbe sancito l’egemonia universale di un «Unico padrone del mondo». Superando il 1989, e guardando al presente, possiamo dire che gli Stati Uniti dopo il ’91 hanno definitivamente preso scettro e globo in mano? L’American way of life è il futuro o il passato? Già Alexandre Kojève, per esempio, parlava di un nuovo attore politico e culturale e di una possibile «giapponizzazione dell’occidente».

Carl Schmitt si è spento nel 1985 a Plettenberg in Westfalia alla veneranda età di 97 anni. Ciò significa che il suo sguardo non supera la «cortina di ferro» e si estende solo alla realtà della guerra fredda. Anche durante questo delicato periodo Schmitt ha continuato la sua attività di studioso e attento indagatore delle questioni di diritto internazionale dei suoi anni. Si espresse quindi sul dualismo USA-URSS, vedendo in esso una tensione verso l’unità del mondo nel segno della tecnica che avrebbe sancito l’egemonia universale di un «Unico padrone del mondo». Superando il 1989, e guardando al presente, possiamo dire che gli Stati Uniti dopo il ’91 hanno definitivamente preso scettro e globo in mano? L’American way of life è il futuro o il passato? Già Alexandre Kojève, per esempio, parlava di un nuovo attore politico e culturale e di una possibile «giapponizzazione dell’occidente». La grande questione dello Schmitt del secondo dopoguerra, concentrato su questioni di diritto internazionale, è l’urgenza di un «nuovo nomos della terra» che supplisca ai terribili sviluppi della dissoluzione dello jus publicum europaeum. Porsi il problema di un nuovo nomos significa considerare la terra come un tutto, un globo, e cercarne la suddivisione e l’ordinamento globali. Ciò sarebbe possibile solo trovando nuovi elementi di equilibrio tra le grandi potenze e superando le criminalizzazioni che hanno contraddistinto i conflitti bellici nel ’900. A scompaginare il vecchio bilanciamento tra terra e mare, di cui l’Inghilterra, potenza oceanica, si fece garante nel periodo dello jus publicum europaeum, si aggiunge, però, una nuova dimensione spaziale: l’aria. L’aria non è solo l’aereo, che sovverte le distinzioni «classiche» di «guerre en forme» terrestre e guerra di preda marittima, ma è anche lo spazio «fluido-gassoso» della Rete. Grazie ai nuovi sviluppi della politica nel mondo si rende sempre più evidente come l’era del digitale non apra solamente nuove possibilità (e nuovi problemi) per l’informazione e la comunicazione, ma si configuri, nella grande epopea degli uomini e della Terra, come l’ultima, grande, rivoluzione spaziale-globale. Come possono rispondere le categorie del nomos di Carl Schmitt al nuevo mundo del digitale?

La grande questione dello Schmitt del secondo dopoguerra, concentrato su questioni di diritto internazionale, è l’urgenza di un «nuovo nomos della terra» che supplisca ai terribili sviluppi della dissoluzione dello jus publicum europaeum. Porsi il problema di un nuovo nomos significa considerare la terra come un tutto, un globo, e cercarne la suddivisione e l’ordinamento globali. Ciò sarebbe possibile solo trovando nuovi elementi di equilibrio tra le grandi potenze e superando le criminalizzazioni che hanno contraddistinto i conflitti bellici nel ’900. A scompaginare il vecchio bilanciamento tra terra e mare, di cui l’Inghilterra, potenza oceanica, si fece garante nel periodo dello jus publicum europaeum, si aggiunge, però, una nuova dimensione spaziale: l’aria. L’aria non è solo l’aereo, che sovverte le distinzioni «classiche» di «guerre en forme» terrestre e guerra di preda marittima, ma è anche lo spazio «fluido-gassoso» della Rete. Grazie ai nuovi sviluppi della politica nel mondo si rende sempre più evidente come l’era del digitale non apra solamente nuove possibilità (e nuovi problemi) per l’informazione e la comunicazione, ma si configuri, nella grande epopea degli uomini e della Terra, come l’ultima, grande, rivoluzione spaziale-globale. Come possono rispondere le categorie del nomos di Carl Schmitt al nuevo mundo del digitale?

Dieses Buch enthält erstmals umfangreiche biografische Daten des Philoso-

Dieses Buch enthält erstmals umfangreiche biografische Daten des Philoso-

Ainsi, la paix est un idéal, et en tant que telle, comme l’espérance d’Epiméthée, elle mérite nos efforts plus que nos ricanements. Il est juste que nous fassions tout pour faire advenir une paix lucide, sachant bien qu’elle ne parviendra jamais à réalisation. En ce sens, l’aspiration à la société cosmopolite est une aspiration morale naturelle à l’humanité, et vouloir récuser cette aspiration au nom de la permanence des conflits serait vouloir retirer à l’homme la moitié de sa condition. En revanche, prétendre atteindre la société cosmopolite comme un programme, à travers la politique, serait susciter un mélange préjudiciable de la morale et de la politique. Parce que nous sommes des créatures politiques, nous devons savoir que la paix universelle n’est qu’un idéal et non une possibilité de réalisation. Parce que nous sommes des créatures morales, nous ne pouvons nous contenter benoîtement des conflits sans espérer jamais les réduire au maximum. Le « règne des fins » ne doit pas aller jusqu’à constituer une eschatologie politique (qui existe aussi bien dans le libéralisme que dans le marxisme, et que l’on trouve au XIX° siècle jusque chez Proudhon), parce qu’alors il suscite une sorte de crase dommageable et irréaliste entre la politique et la morale. Mais l’espérance du bien ne constitue pas seulement une sorte d’exutoire pour un homme malheureux parce qu’englué dans les exigences triviales d’un monde conflictuel : elle engage l’humanité à avancer sans cesse vers son idéal, et par là à améliorer son monde dans le sens qui lui paraît le meilleur, même si elle ne parvient jamais à réalisation complète.

Ainsi, la paix est un idéal, et en tant que telle, comme l’espérance d’Epiméthée, elle mérite nos efforts plus que nos ricanements. Il est juste que nous fassions tout pour faire advenir une paix lucide, sachant bien qu’elle ne parviendra jamais à réalisation. En ce sens, l’aspiration à la société cosmopolite est une aspiration morale naturelle à l’humanité, et vouloir récuser cette aspiration au nom de la permanence des conflits serait vouloir retirer à l’homme la moitié de sa condition. En revanche, prétendre atteindre la société cosmopolite comme un programme, à travers la politique, serait susciter un mélange préjudiciable de la morale et de la politique. Parce que nous sommes des créatures politiques, nous devons savoir que la paix universelle n’est qu’un idéal et non une possibilité de réalisation. Parce que nous sommes des créatures morales, nous ne pouvons nous contenter benoîtement des conflits sans espérer jamais les réduire au maximum. Le « règne des fins » ne doit pas aller jusqu’à constituer une eschatologie politique (qui existe aussi bien dans le libéralisme que dans le marxisme, et que l’on trouve au XIX° siècle jusque chez Proudhon), parce qu’alors il suscite une sorte de crase dommageable et irréaliste entre la politique et la morale. Mais l’espérance du bien ne constitue pas seulement une sorte d’exutoire pour un homme malheureux parce qu’englué dans les exigences triviales d’un monde conflictuel : elle engage l’humanité à avancer sans cesse vers son idéal, et par là à améliorer son monde dans le sens qui lui paraît le meilleur, même si elle ne parvient jamais à réalisation complète.

D’abord instituteur pour pallier la disparition brutale de son père, le germanophone Julien Freund se retrouve otage des Allemands en juillet 1940 avant de poursuivre ses études à l’Université de Strasbourg repliée à Clermond-Ferrand. Il entre dès janvier 1941 en résistance dans le réseau Libération, puis dans les Groupes francs de combat de Jacques Renouvin. Arrêté en juin 1942, il est détenu dans la forteresse de Sisteron d’où il s’évade deux ans plus tard. Il rejoint alors un maquis FTP (Francs-tireurs et partisans) de la Drôme. Il y découvre l’endoctrinement communiste et la bassesse humaine.

D’abord instituteur pour pallier la disparition brutale de son père, le germanophone Julien Freund se retrouve otage des Allemands en juillet 1940 avant de poursuivre ses études à l’Université de Strasbourg repliée à Clermond-Ferrand. Il entre dès janvier 1941 en résistance dans le réseau Libération, puis dans les Groupes francs de combat de Jacques Renouvin. Arrêté en juin 1942, il est détenu dans la forteresse de Sisteron d’où il s’évade deux ans plus tard. Il rejoint alors un maquis FTP (Francs-tireurs et partisans) de la Drôme. Il y découvre l’endoctrinement communiste et la bassesse humaine. La politique se fait sur le terrain, et non dans les divagations spéculatives (p. 13). » Il relève dans son étude remarquable sur la notion de décadence que « si les civilisations ne se valent pas, c’est que chacune repose sur une hiérarchie des valeurs qui lui est propre et qui est la résultante d’options plus ou moins conscientes concernant les investissements capables de stimuler leur énergie. Cette hiérarchie conditionne donc l’originalité de chaque civilisation. Reniant leur passé, les Européens se sont laissés imposer, par leurs intellectuels, l’idée que leur civilisation n’était sous aucun rapport supérieure aux autres et même qu’ils devraient battre leur coulpe pour avoir inventé le capitalisme, l’impérialisme, la bombe thermonucléaire, etc. Une fausse interprétation de la notion de tolérance a largement contribué à cette culpabilisation. En effet, ni les idées, ni les valeurs ne sont tolérantes. Refusant de reconnaître leur originalité, les Européens n’adhèrent plus aux valeurs dont ils sont porteurs, de sorte qu’ils sont en train de perdre l’esprit de leur culture et le dynamisme qui en découle. Si encore ils ne faisaient que récuser leurs philosophies du passé, mais ils sont en train d’étouffer le sens de la philosophie qu’ils ont développée durant des siècles. La confusion des valeurs et la crise spirituelle qui en est la conséquence en sont le pitoyable témoignage. L’égalitarisme ambiant les conduit jusqu’à oublier que la hiérarchie est consubstantielle à l’idée même de valeur (p. 364) ».

La politique se fait sur le terrain, et non dans les divagations spéculatives (p. 13). » Il relève dans son étude remarquable sur la notion de décadence que « si les civilisations ne se valent pas, c’est que chacune repose sur une hiérarchie des valeurs qui lui est propre et qui est la résultante d’options plus ou moins conscientes concernant les investissements capables de stimuler leur énergie. Cette hiérarchie conditionne donc l’originalité de chaque civilisation. Reniant leur passé, les Européens se sont laissés imposer, par leurs intellectuels, l’idée que leur civilisation n’était sous aucun rapport supérieure aux autres et même qu’ils devraient battre leur coulpe pour avoir inventé le capitalisme, l’impérialisme, la bombe thermonucléaire, etc. Une fausse interprétation de la notion de tolérance a largement contribué à cette culpabilisation. En effet, ni les idées, ni les valeurs ne sont tolérantes. Refusant de reconnaître leur originalité, les Européens n’adhèrent plus aux valeurs dont ils sont porteurs, de sorte qu’ils sont en train de perdre l’esprit de leur culture et le dynamisme qui en découle. Si encore ils ne faisaient que récuser leurs philosophies du passé, mais ils sont en train d’étouffer le sens de la philosophie qu’ils ont développée durant des siècles. La confusion des valeurs et la crise spirituelle qui en est la conséquence en sont le pitoyable témoignage. L’égalitarisme ambiant les conduit jusqu’à oublier que la hiérarchie est consubstantielle à l’idée même de valeur (p. 364) ».

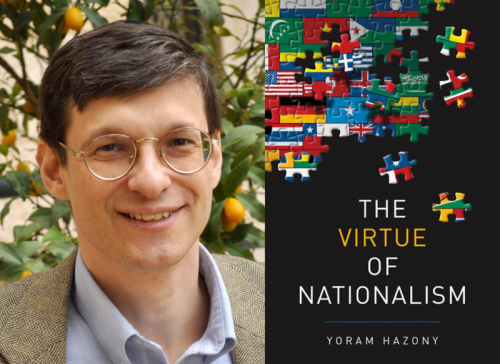

Hazony defines the nation-state in contradistinction to two alternatives: tribal anarchy and imperialism. Tribal anarchy is basically a condition of more or less perpetual suspicion, injustice, and conflict that exists between tribes of the same nation in the absence of a common government. Imperialism is an attempt to extend common government to the different nations of the world, which exist in a state of anarchy vis-à-vis each other.

Hazony defines the nation-state in contradistinction to two alternatives: tribal anarchy and imperialism. Tribal anarchy is basically a condition of more or less perpetual suspicion, injustice, and conflict that exists between tribes of the same nation in the absence of a common government. Imperialism is an attempt to extend common government to the different nations of the world, which exist in a state of anarchy vis-à-vis each other. Hazony argues that nationalism has a number of advantages over tribal anarchy. The small states of ancient Greece, medieval Italy, and modern Germany wasted a great deal of blood and wealth in conflicts that were almost literally fratricidal, and that made these peoples vulnerable to aggression from entirely different peoples. Unifying warring “tribes” of the same peoples under a nation-state created peace and prosperity within their borders and presented a united front to potential enemies from without.

Hazony argues that nationalism has a number of advantages over tribal anarchy. The small states of ancient Greece, medieval Italy, and modern Germany wasted a great deal of blood and wealth in conflicts that were almost literally fratricidal, and that made these peoples vulnerable to aggression from entirely different peoples. Unifying warring “tribes” of the same peoples under a nation-state created peace and prosperity within their borders and presented a united front to potential enemies from without. The “mutual loyalty” at the heart of nation-states is a product of a common ethnicity. How does ethnic unity make free institutions possible? Every society needs order. Order either comes from within the individual or is imposed from without. A society in which individuals share a strong normative culture does not need a heavy-handed state to impose social order.

The “mutual loyalty” at the heart of nation-states is a product of a common ethnicity. How does ethnic unity make free institutions possible? Every society needs order. Order either comes from within the individual or is imposed from without. A society in which individuals share a strong normative culture does not need a heavy-handed state to impose social order. In fact, Hazony argues, imperialism is far more conducive to hatred and violence than nationalism.

In fact, Hazony argues, imperialism is far more conducive to hatred and violence than nationalism. The third principle is “government monopoly of organized force within the state” (p. 177), as opposed to tribal anarchy. A failed state is one in which different ethnic groups create their own militias.

The third principle is “government monopoly of organized force within the state” (p. 177), as opposed to tribal anarchy. A failed state is one in which different ethnic groups create their own militias. The difference between good nationalism and bad nationalism is simple: Good nationalism is universalist. A good nationalist wants to ensure the sovereignty of his own people, but does not wish to deny the sovereignty of other peoples. Instead, he envisions a global order of sovereign nations, to the extent that this is possible. Hazony, however, wishes to stop short of the idea of a universal right to self-determination, which I will deal with at greater length later.

The difference between good nationalism and bad nationalism is simple: Good nationalism is universalist. A good nationalist wants to ensure the sovereignty of his own people, but does not wish to deny the sovereignty of other peoples. Instead, he envisions a global order of sovereign nations, to the extent that this is possible. Hazony, however, wishes to stop short of the idea of a universal right to self-determination, which I will deal with at greater length later.

Carl Schmitt and Leo Strauss are extremely popular in China, especially in Mainland China—this is no longer a secret in the Western academia. As early as 2003, Stanley Rosen had already told the Boston Globe that “A very, very significant circle of Strauss admirers has sprung up, of all places, China.”

Carl Schmitt and Leo Strauss are extremely popular in China, especially in Mainland China—this is no longer a secret in the Western academia. As early as 2003, Stanley Rosen had already told the Boston Globe that “A very, very significant circle of Strauss admirers has sprung up, of all places, China.”

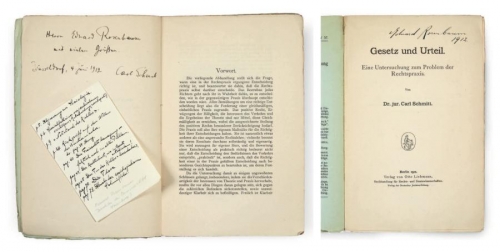

De l’œuvre proprement juridique du jeune Carl Schmitt, disons de celle d’avant 1933, nous possédons en français Théorie de la constitution (1928, PUF 1993), La valeur de l’État et la signification de l’individu (1914, Droz 2003), mais il nous manquait jusqu’aujourd’hui un petit ouvrage de 1912 intitulé Loi et jugement, qu’Olivier Beaud, dans sa préface à l’édition française de Théorie de la constitution, qualifie de « véritable recherche de théorie du droit abordant les questions les plus fondamentales ».

De l’œuvre proprement juridique du jeune Carl Schmitt, disons de celle d’avant 1933, nous possédons en français Théorie de la constitution (1928, PUF 1993), La valeur de l’État et la signification de l’individu (1914, Droz 2003), mais il nous manquait jusqu’aujourd’hui un petit ouvrage de 1912 intitulé Loi et jugement, qu’Olivier Beaud, dans sa préface à l’édition française de Théorie de la constitution, qualifie de « véritable recherche de théorie du droit abordant les questions les plus fondamentales ».

La seconde raison de la défaite perpétuelle de la droite, c’est son conservatisme. Les réaco-conservateurs assimilent trop souvent l’avenir à un déploiement inéluctable des forces progressistes. Ils en viennent à prendre l’objet (l’avenir) façonné par le sujet (la gauche) pour le sujet lui-même. Le futur étant devenu synonyme d’avancées « progressistes », l’unique remède ne pourrait être que son contraire – le passé – plutôt qu’un avenir alternatif. Or il y a là une forme de défaitisme, comme si la droite assimilait sa propre déconfiture, ratifiant le monopole de la gauche sur l’avenir. Puisque l’Histoire n’est qu’une longue série de victoires progressistes, c’est l’avenir lui-même qu’il faudrait brider, plutôt que les acteurs qui le façonnent. Ralentir le temps et sanctuariser certaines institutions apparaît alors comme la solution par défaut.

La seconde raison de la défaite perpétuelle de la droite, c’est son conservatisme. Les réaco-conservateurs assimilent trop souvent l’avenir à un déploiement inéluctable des forces progressistes. Ils en viennent à prendre l’objet (l’avenir) façonné par le sujet (la gauche) pour le sujet lui-même. Le futur étant devenu synonyme d’avancées « progressistes », l’unique remède ne pourrait être que son contraire – le passé – plutôt qu’un avenir alternatif. Or il y a là une forme de défaitisme, comme si la droite assimilait sa propre déconfiture, ratifiant le monopole de la gauche sur l’avenir. Puisque l’Histoire n’est qu’une longue série de victoires progressistes, c’est l’avenir lui-même qu’il faudrait brider, plutôt que les acteurs qui le façonnent. Ralentir le temps et sanctuariser certaines institutions apparaît alors comme la solution par défaut.

Les organisations professionnelles sont composées de représentants élus et de véritables experts désignés par l’État : elles renferment, en proportions à déterminer par une loi, des chefs d’entreprise, des cadres, des employés et des ouvriers, de l’industrie et de l’artisanat, de l’agriculture, de la pêche et des transports, des professions libérales et d’employés de l’État. Elles ont pour rôles de régler les conditions de travail et de rémunération, d’organiser la formation initiale des apprentis et la formation continue des travailleurs, voire de présider au regroupement des petites entreprises pour en accroître la rentabilité, économiser des matières premières et standardiser la production (Dauphin-Meunier, 1941 ; Denis, 1941 ; Bouvier-Ajam, 1943). C’est un régime particulièrement adapté à la gestion des crises économiques et sociales.

Les organisations professionnelles sont composées de représentants élus et de véritables experts désignés par l’État : elles renferment, en proportions à déterminer par une loi, des chefs d’entreprise, des cadres, des employés et des ouvriers, de l’industrie et de l’artisanat, de l’agriculture, de la pêche et des transports, des professions libérales et d’employés de l’État. Elles ont pour rôles de régler les conditions de travail et de rémunération, d’organiser la formation initiale des apprentis et la formation continue des travailleurs, voire de présider au regroupement des petites entreprises pour en accroître la rentabilité, économiser des matières premières et standardiser la production (Dauphin-Meunier, 1941 ; Denis, 1941 ; Bouvier-Ajam, 1943). C’est un régime particulièrement adapté à la gestion des crises économiques et sociales.

L’économie corporatiste fut la solution adoptée par les populistes du XXe siècle. Comme l’a très justement écrit Hilaire Belloc (in L’État servile, de 1912) : « Le contrôle de la production des richesses revient, en définitive, à contrôler la vie humaine ».

L’économie corporatiste fut la solution adoptée par les populistes du XXe siècle. Comme l’a très justement écrit Hilaire Belloc (in L’État servile, de 1912) : « Le contrôle de la production des richesses revient, en définitive, à contrôler la vie humaine ».

Sourcé et documenté, mais en même temps décapant sans concessions et affranchi de tous les conventionnalismes, ce livre atypique sort résolument des sentiers battus de l’histoire des idées politiques. Son auteur, Dalmacio Negro Pavón, politologue renommé dans le monde hispanique, est au nombre de ceux qui incarnent le mieux la tradition académique européenne, celle d’une époque où le politiquement correct n’avait pas encore fait ses ravages, et où la majorité des universitaires adhéraient avec conviction, – et non par opportunisme comme si souvent aujourd’hui -, aux valeurs scientifiques de rigueur, de probité et d’intégrité. Que nous dit-il ? Résumons-le en puisant largement dans ses analyses, ses propos et ses termes:

Sourcé et documenté, mais en même temps décapant sans concessions et affranchi de tous les conventionnalismes, ce livre atypique sort résolument des sentiers battus de l’histoire des idées politiques. Son auteur, Dalmacio Negro Pavón, politologue renommé dans le monde hispanique, est au nombre de ceux qui incarnent le mieux la tradition académique européenne, celle d’une époque où le politiquement correct n’avait pas encore fait ses ravages, et où la majorité des universitaires adhéraient avec conviction, – et non par opportunisme comme si souvent aujourd’hui -, aux valeurs scientifiques de rigueur, de probité et d’intégrité. Que nous dit-il ? Résumons-le en puisant largement dans ses analyses, ses propos et ses termes: Une révolution a besoin de dirigeants, mais l’étatisme a infantilisé la conscience des Européens. Celle-ci a subi une telle contagion que l’émergence de véritables dirigeants est devenue quasiment impossible et que lorsqu’elle se produit, la méfiance empêche de les suivre. Mieux vaut donc, une fois parvenu à ce stade, faire confiance au hasard, à l’ennui ou à l’humour, autant de forces historiques majeures, auxquelles on n’accorde pas suffisamment d’attention parce qu’elles sont cachées derrière le paravent de l’enthousiasme progressiste.

Une révolution a besoin de dirigeants, mais l’étatisme a infantilisé la conscience des Européens. Celle-ci a subi une telle contagion que l’émergence de véritables dirigeants est devenue quasiment impossible et que lorsqu’elle se produit, la méfiance empêche de les suivre. Mieux vaut donc, une fois parvenu à ce stade, faire confiance au hasard, à l’ennui ou à l’humour, autant de forces historiques majeures, auxquelles on n’accorde pas suffisamment d’attention parce qu’elles sont cachées derrière le paravent de l’enthousiasme progressiste. Le réaliste authentique affirme que la finalité propre à la politique est le bien commun, mais il reconnait la nécessité vitale des finalités non politiques(le bonheur et la justice). La politique est selon lui au service de l’homme. La mission de la politique n’est pas de changer l’homme ou de le rendre meilleur (ce qui est le chemin des totalitarismes), mais d’organiser les conditions de la coexistence humaine, de mettre en forme la collectivité, d’assurer la concorde intérieure et la sécurité extérieure. Voilà pourquoi les conflits doivent être, selon lui, canalisés, réglementés, institutionnalisés et autant que possible résolus sans violence.

Le réaliste authentique affirme que la finalité propre à la politique est le bien commun, mais il reconnait la nécessité vitale des finalités non politiques(le bonheur et la justice). La politique est selon lui au service de l’homme. La mission de la politique n’est pas de changer l’homme ou de le rendre meilleur (ce qui est le chemin des totalitarismes), mais d’organiser les conditions de la coexistence humaine, de mettre en forme la collectivité, d’assurer la concorde intérieure et la sécurité extérieure. Voilà pourquoi les conflits doivent être, selon lui, canalisés, réglementés, institutionnalisés et autant que possible résolus sans violence.

Cela étant, on peut être un sceptique ou un pessimiste lucide mais refuser pour autant de désespérer. On ne peut pas éliminer les oligarchies. Soit ! Mais, comme nous le dit Dalmacio Negro Pavón, il y a des régimes politiques qui sont plus ou moins capables d’en mitiger les effets et de les contrôler. Le nœud de la question est d’empêcher que les détenteurs du pouvoir ne soient que de simples courroies de transmission des intérêts, des désirs et des sentiments de l’oligarchie politique, sociale, économique et culturelle. Les hommes craignent toujours le pouvoir auquel ils sont soumis, mais le pouvoir qui les soumet craint lui aussi toujours la collectivité sur laquelle il règne. Et il existe une condition essentielle pour que la démocratie politique soit possible et que sa corruption devienne beaucoup plus difficile sinon impossible, souligne encore Dalmacio Negro Pavón. Il faut que l’attitude à l’égard du gouvernement soit toujours méfiante, même lorsqu’il s’agit d’amis ou de personnes pour lesquelles on a voté. Bertrand de Jouvenel disait à ce propos très justement: « le gouvernement des amis est la manière barbare de gouverner ».

Cela étant, on peut être un sceptique ou un pessimiste lucide mais refuser pour autant de désespérer. On ne peut pas éliminer les oligarchies. Soit ! Mais, comme nous le dit Dalmacio Negro Pavón, il y a des régimes politiques qui sont plus ou moins capables d’en mitiger les effets et de les contrôler. Le nœud de la question est d’empêcher que les détenteurs du pouvoir ne soient que de simples courroies de transmission des intérêts, des désirs et des sentiments de l’oligarchie politique, sociale, économique et culturelle. Les hommes craignent toujours le pouvoir auquel ils sont soumis, mais le pouvoir qui les soumet craint lui aussi toujours la collectivité sur laquelle il règne. Et il existe une condition essentielle pour que la démocratie politique soit possible et que sa corruption devienne beaucoup plus difficile sinon impossible, souligne encore Dalmacio Negro Pavón. Il faut que l’attitude à l’égard du gouvernement soit toujours méfiante, même lorsqu’il s’agit d’amis ou de personnes pour lesquelles on a voté. Bertrand de Jouvenel disait à ce propos très justement: « le gouvernement des amis est la manière barbare de gouverner ».

La publicité est évidemment toujours sous le soupçon. Dans un livre qui avait fait du bruit à l'époque, "la persuasion cachée" de 1957, Vance Packard révélait les stratégies des compagnies publicitaires qui truffaient leurs annonces de textes et images supposés agir sur nos motivations cachées en échappant à la censure du Moi.

La publicité est évidemment toujours sous le soupçon. Dans un livre qui avait fait du bruit à l'époque, "la persuasion cachée" de 1957, Vance Packard révélait les stratégies des compagnies publicitaires qui truffaient leurs annonces de textes et images supposés agir sur nos motivations cachées en échappant à la censure du Moi.

Mais que pensait vraiment Freud ?

Mais que pensait vraiment Freud ?

Polymnia Athanassiadi, professeur d’histoire ancienne à l’Université d’Athènes, spécialiste du platonisme tardif (le néoplatonisme) avait bousculé quelques certitudes, dans son ouvrage publié en 2006, « la lutte pour l’orthodoxie dans le platonisme tardif », en montrant que les structures de pensée dans l’Empire gréco-romain, dont l’aboutissement serait la suppression de toute possibilité discursive au sein de l’élite intellectuelle, étaient analogues chez les philosophes « païens » et les théologiens chrétiens. Cette osmose, à laquelle il était impossible d’échapper, se retrouve au niveau des structures politiques et administratives, avant et après Constantin. L’État « païen », selon Mme Athanassiadi, prépare l’État chrétien, et le contrôle total de la société, des corps et des esprits. C’est la thèse contenue dans une étude éditée en 2010, Vers la pensée unique. La montée de l’intolérance dans l’Antiquité tardive.

Polymnia Athanassiadi, professeur d’histoire ancienne à l’Université d’Athènes, spécialiste du platonisme tardif (le néoplatonisme) avait bousculé quelques certitudes, dans son ouvrage publié en 2006, « la lutte pour l’orthodoxie dans le platonisme tardif », en montrant que les structures de pensée dans l’Empire gréco-romain, dont l’aboutissement serait la suppression de toute possibilité discursive au sein de l’élite intellectuelle, étaient analogues chez les philosophes « païens » et les théologiens chrétiens. Cette osmose, à laquelle il était impossible d’échapper, se retrouve au niveau des structures politiques et administratives, avant et après Constantin. L’État « païen », selon Mme Athanassiadi, prépare l’État chrétien, et le contrôle total de la société, des corps et des esprits. C’est la thèse contenue dans une étude éditée en 2010, Vers la pensée unique. La montée de l’intolérance dans l’Antiquité tardive. Polymnia Athanassiadi rappelle les influences qui ont pu marquer cette conception positive : elle a été élaborée durant une époque où la détente d’après-guerre devenait possible, où l’individualisme se répandait, avec l’hédonisme qui l’accompagne inévitablement, où le pacifisme devient, à la fin années soixante, la pensée obligée de l’élite. De ce fait, les conflits sont minimisés.

Polymnia Athanassiadi rappelle les influences qui ont pu marquer cette conception positive : elle a été élaborée durant une époque où la détente d’après-guerre devenait possible, où l’individualisme se répandait, avec l’hédonisme qui l’accompagne inévitablement, où le pacifisme devient, à la fin années soixante, la pensée obligée de l’élite. De ce fait, les conflits sont minimisés.

Notons que Julien, le restaurateur du paganisme d’État, est mis sur le même plan que Constantin et que ses successeurs chrétien. En voulant créer une « Église païenne », en se mêlant de théologie, en édictant des règles de piété et de moralité, en excluant épicuriens, sceptiques et cyniques, il a consolidé la cohérence théologico-autoritaire de l’Empire. Il assumait de ce fait la charge sacrale dont l’empereur était dépositaire, singulièrement la dynastie dont il était l’héritier et le continuateur. Il avait conscience d’appartenir à une famille, fondée par Claude le Gothique (268 – 270), selon lui dépositaire d’une mission de jonction entre l’ici-bas et le divin.

Notons que Julien, le restaurateur du paganisme d’État, est mis sur le même plan que Constantin et que ses successeurs chrétien. En voulant créer une « Église païenne », en se mêlant de théologie, en édictant des règles de piété et de moralité, en excluant épicuriens, sceptiques et cyniques, il a consolidé la cohérence théologico-autoritaire de l’Empire. Il assumait de ce fait la charge sacrale dont l’empereur était dépositaire, singulièrement la dynastie dont il était l’héritier et le continuateur. Il avait conscience d’appartenir à une famille, fondée par Claude le Gothique (268 – 270), selon lui dépositaire d’une mission de jonction entre l’ici-bas et le divin.

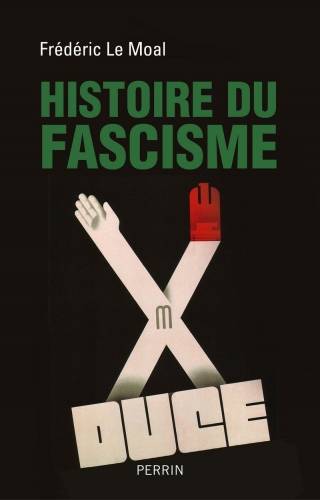

La thèse n’est pas nouvelle. En 1984, le Club de l’Horloge sortait chez Albin Michel Socialisme et fascisme : une même famille ?. Ne connaissant pas ce livre, Frédéric Le Moal arrive néanmoins aux mêmes conclusions. Il se cantonne toutefois à la seule Italie en oubliant ses interactions européennes, voire extra-européennes (le péronisme en Argentine). Il circonscrit le fascisme en phénomène italien spécifique. Certes, il mentionne l’influence d’Oswald Spengler sur Mussolini, mais il en oublie le contexte international, à savoir l’existence protéiforme d’une révolution conservatrice non-conformiste. En outre, l’auteur ne souscrit pas à la thèse de Zeev Sternhell pour qui le fascisme italien a eu une matrice française.

La thèse n’est pas nouvelle. En 1984, le Club de l’Horloge sortait chez Albin Michel Socialisme et fascisme : une même famille ?. Ne connaissant pas ce livre, Frédéric Le Moal arrive néanmoins aux mêmes conclusions. Il se cantonne toutefois à la seule Italie en oubliant ses interactions européennes, voire extra-européennes (le péronisme en Argentine). Il circonscrit le fascisme en phénomène italien spécifique. Certes, il mentionne l’influence d’Oswald Spengler sur Mussolini, mais il en oublie le contexte international, à savoir l’existence protéiforme d’une révolution conservatrice non-conformiste. En outre, l’auteur ne souscrit pas à la thèse de Zeev Sternhell pour qui le fascisme italien a eu une matrice française.

Pourtant, la question du conservatisme est complexe car le terme, lui-même, renvoie à des phénomènes – et des réalités – politiques différents, du parti conservateur britannique (les Tories, au pouvoir au Royaume-Uni en alternance démocratique avec le Labour travailliste) au monolithique ancien Parti communiste soviétique (PCUS), dont les caciques étaient qualifiés de « conservateurs », sans doute en partie en raison de leur âge… Une seule chose est sûre, l’absence pérenne – ou presque (l’exception Fillon vaincue par le très progressiste hebdomadaire Le Canard enchaîné) – du terme dans le débat français, depuis la fin de la Révolution française au moins jusqu’à récemment (puisque l’on parle de néo-conservateurs que la gauche morale n’hésite pas, d’ailleurs, à qualifier de « néo-cons » – le discrédit sémantique est toujours au cœur des débats et fonctionne d’ailleurs, mais s’agissant de cette tendance, il s’agit, le plus souvent, de « libéraux américains » – donc, la gauche américaine issue des démocrates – défendant des thèses conservatrices liées à la défense de la nation : identités fédérées réaffirmées, rejet du « politically correct », rejet du fiscalisme…).

Pourtant, la question du conservatisme est complexe car le terme, lui-même, renvoie à des phénomènes – et des réalités – politiques différents, du parti conservateur britannique (les Tories, au pouvoir au Royaume-Uni en alternance démocratique avec le Labour travailliste) au monolithique ancien Parti communiste soviétique (PCUS), dont les caciques étaient qualifiés de « conservateurs », sans doute en partie en raison de leur âge… Une seule chose est sûre, l’absence pérenne – ou presque (l’exception Fillon vaincue par le très progressiste hebdomadaire Le Canard enchaîné) – du terme dans le débat français, depuis la fin de la Révolution française au moins jusqu’à récemment (puisque l’on parle de néo-conservateurs que la gauche morale n’hésite pas, d’ailleurs, à qualifier de « néo-cons » – le discrédit sémantique est toujours au cœur des débats et fonctionne d’ailleurs, mais s’agissant de cette tendance, il s’agit, le plus souvent, de « libéraux américains » – donc, la gauche américaine issue des démocrates – défendant des thèses conservatrices liées à la défense de la nation : identités fédérées réaffirmées, rejet du « politically correct », rejet du fiscalisme…). En effet, originellement, l’esprit conservateur est de nature collective : il vise à préserver un ordre naturel préexistant alors que le libéralisme post-révolutionnaire naît du développement des besoins exprimés individuellement. Le conservatisme ne nie pas la liberté mais se rattache davantage à la liberté concrète, plus qu’abstraite, à la liberté collective, plus qu’individuelle. Le triomphe de l’individualisme, état suprême du libéralisme, s’oppose au conservatisme des systèmes normatifs. C’est ici, à mon sens, que le renouveau du conservatisme prend tout son sens : le développement de l’individualisme a contribué à l’effacement des repères collectifs, identitaires, religieux ou culturels. La fin du bien commun a rendu la modernité, expression d’un libéralisme fondé sur l’individu, exécrable pour les « oubliés » du Système. L’extension des droits individuels comme le droit à l’enfant, exalté par les « progressistes », vient à exclure ce bien commun qu’est le droit de l’enfant à vivre au sein d’une famille. Alexandre Soljenitsyne dénonçait déjà, en 1978, dans Le déclin du courage, le matérialisme occidental issu de la société de consommation. Le déracinement, fruit de ce conservatisme anglo-saxon, a touché d’abord les classes populaires souvent qualifiées d’« oubliées » par nos chercheurs sociologues. La France des oubliés, c’est d’abord l’expression d’une société qui a fait de l’individualisme libéral son étalon, son exigence. Or, le conservatisme, forme d’enracinement, aurait pu, pourrait, peut encore venir tempérer ce système économique certes nécessaire mais qui doit constituer un des piliers d’une société tridimensionnelle et non le pilier central.

En effet, originellement, l’esprit conservateur est de nature collective : il vise à préserver un ordre naturel préexistant alors que le libéralisme post-révolutionnaire naît du développement des besoins exprimés individuellement. Le conservatisme ne nie pas la liberté mais se rattache davantage à la liberté concrète, plus qu’abstraite, à la liberté collective, plus qu’individuelle. Le triomphe de l’individualisme, état suprême du libéralisme, s’oppose au conservatisme des systèmes normatifs. C’est ici, à mon sens, que le renouveau du conservatisme prend tout son sens : le développement de l’individualisme a contribué à l’effacement des repères collectifs, identitaires, religieux ou culturels. La fin du bien commun a rendu la modernité, expression d’un libéralisme fondé sur l’individu, exécrable pour les « oubliés » du Système. L’extension des droits individuels comme le droit à l’enfant, exalté par les « progressistes », vient à exclure ce bien commun qu’est le droit de l’enfant à vivre au sein d’une famille. Alexandre Soljenitsyne dénonçait déjà, en 1978, dans Le déclin du courage, le matérialisme occidental issu de la société de consommation. Le déracinement, fruit de ce conservatisme anglo-saxon, a touché d’abord les classes populaires souvent qualifiées d’« oubliées » par nos chercheurs sociologues. La France des oubliés, c’est d’abord l’expression d’une société qui a fait de l’individualisme libéral son étalon, son exigence. Or, le conservatisme, forme d’enracinement, aurait pu, pourrait, peut encore venir tempérer ce système économique certes nécessaire mais qui doit constituer un des piliers d’une société tridimensionnelle et non le pilier central.

« Pour une évidente clarté sémantique, écrit-il, il serait préférable de laisser au Flamby normal, à l’exquise Najat Vallaud-Belkacem et aux morts vivants du siège vendu, rue de Solférino, ce mot de socialiste et d’en trouver un autre plus pertinent. Sachant que travaillisme risquerait de susciter les mêmes confusions lexicales, les termes de solidarisme ou, pourquoi pas, celui de justicialisme, directement venu de l’Argentine péronisme, seraient bien plus appropriés. »

« Pour une évidente clarté sémantique, écrit-il, il serait préférable de laisser au Flamby normal, à l’exquise Najat Vallaud-Belkacem et aux morts vivants du siège vendu, rue de Solférino, ce mot de socialiste et d’en trouver un autre plus pertinent. Sachant que travaillisme risquerait de susciter les mêmes confusions lexicales, les termes de solidarisme ou, pourquoi pas, celui de justicialisme, directement venu de l’Argentine péronisme, seraient bien plus appropriés. »