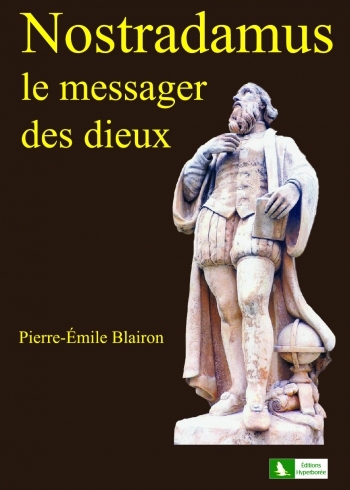

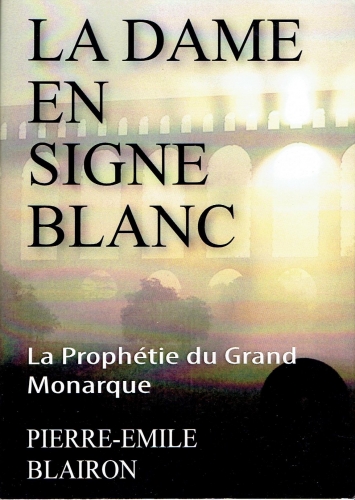

Y a–t-il une Provence secrète ? Il semblerait bien que oui. Pierre-Émile Blairon a eu l’excellente idée de rééditer son livre La Dame en signe blanc (La prophétie du Grand Monarque, Éditions Hyperborée, 2017, 284 p., 20,00 €) qui plonge le lecteur dans les mystères de la région de Roquefavour, entre Graal païen et prédictions de Nostradamus. Il n’en fallait pas plus pour qu’Europe Maxima se décide à l’interroger.

Y a–t-il une Provence secrète ? Il semblerait bien que oui. Pierre-Émile Blairon a eu l’excellente idée de rééditer son livre La Dame en signe blanc (La prophétie du Grand Monarque, Éditions Hyperborée, 2017, 284 p., 20,00 €) qui plonge le lecteur dans les mystères de la région de Roquefavour, entre Graal païen et prédictions de Nostradamus. Il n’en fallait pas plus pour qu’Europe Maxima se décide à l’interroger.

Europe Maxima : Lorsque l’on regarde la note biographique de vos ouvrages il est question de deux passions, la Provence et la spiritualité traditionnelle. La Dame en signe blanc réunit ces deux passions qui vous sont chères. Par quelle « intuition intellectuelle » avez-vous opéré cette jonction ?

Pierre-Émile Blairon : J’avoue que cette expression « intuition intellectuelle », quand je l’ai lue sous la plume de Julius Evola (mais je crois qu’elle provient de René Guénon), m’a décontenancé tellement ces deux termes sont antinomiques, tellement nos deux grands traditionalistes sont proches de ce mot « intuition » et loin de cet autre mot : « intellectuelle », en tout cas, dans l’acception que nous lui donnons aujourd’hui; il n’est rien de plus éloigné d’un intellectuel que l’intuition. Un intellectuel se trompe toujours, aveuglé qu’il est par l’image qu’il prend soin de donner au monde, au « public », de son immodeste et narcissique personne; il se comporte comme un politicien, toujours à chercher d’où vient le vent, sans jamais découvrir où il va (il s’en moque, c’est le temps présent qui compte : après moi, le déluge) mais en caressant dans le sens du poil les masses, les médias, et les nombreuses mais peu diverses coteries parisiennes, car il n’est de bon bec…

Si j’ai bien compris le sens que voulait lui donner Evola, « l’intuition intellectuelle » fait qu’un être différencié ne peut pas se tromper car il porte en lui, naturellement, comme un don, comme une mission – un don est une mission, sinon, à quoi servirait-il ? – cet héritage supra-humain qui lui a fait choisir la Voie des Dieux, olympienne, aristocratique, plutôt que la Voie des Pères, qui lui a fait choisir l’immortalité des dieux, même si elle est, de facto, inaccessible, plutôt que la laborieuse suite lignagière des générations humaines.

Pour en revenir à mes choix, il est évident que j’ai voulu conjuguer mon désir de comprendre le monde à son plus haut niveau, cosmique, et mon besoin d’enracinement, de réenracinement, en ce qui me concerne – je suis né dans une ancienne province française qui n’existe plus – du sol qui vous porte, ou, mieux, qui vous a vu naître, la tête dans les étoiles, les pieds sur terre, image qui résume cette recherche de l’équilibre qui est la base même de l’identité indo-européenne.

EM : Votre intérêt pour la Provence vous a amené à étudier l’œuvre de Nostradamus, figure énigmatique dont certaines prédictions sont plus que troublantes… Pensez-vous que ce dernier détenait un savoir traditionnel ?

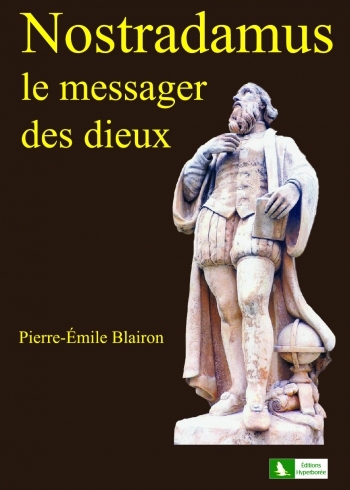

P-ÉB : La figure de Nostradamus a été ternie par les nombreux exégètes qui se sont servis de son nom pour faire connaître le leur, sans bien comprendre le personnage et son œuvre.

On a présenté Nostradamus soit comme un astrologue, charlatan revêtu d’une longue robe bleue parsemée d’étoiles, une boule de cristal à la main, soit comme un « humaniste » parce qu’il vivait à l’époque de la Renaissance (et encore pire, dans l’acception qu’on lui donne aujourd’hui, celui qui s’intéresse à son prochain, mais plus encore à son lointain), soit comme un médecin qui soignait par les plantes au risque d’être inquiété par l’Inquisition. En vérité, Nostradamus a passé sa vie à acquérir toutes sortes de connaissances, alchimiques, astrologiques, astronomiques, médicales, historiques, métaphysiques… pour mener à bien une mission dont il était conscient d’en être porteur : annoncer aux humains du XXIe siècle le sort qui les attend. La fin d’un cycle mais le commencement d’un nouveau en même temps, enfin, juste après… J’ai sous-titré la biographie que j’ai consacrée à Nostradamus parue aux éditions Hyperborée, « Le messager des dieux », parce que Nostradamus connaissait parfaitement le système des cycles et la Tradition primordiale, laquelle représente symboliquement ce qu’on peut appeler « les Dieux », que Guénon appelle aussi le « supra-humain »; Nostradamus a vécu pendant ce qu’on a appelé la Renaissance, période qui constituait un palier dans le cours de l’Âge de Fer, le cycle final et, comme tel, nous sommes en pleine inversion des valeurs : la Renaissance signifie le début de la fin comme le siècle des Lumières, celui de l’obscurcissement du monde.

EM : En parlant de Tradition, pourriez-vous nous présenter la revue Hyperborée ?

P-ÉB : Hyperborée est la fille d’une modeste revue que j’avais lancée en 1994, qui s’appelait Roquefavour. J’avais constaté que la véritable et salutaire révolution qu’avait constituée la réapparition du paganisme 25 ans plus tôt, initiée par ce qu’on a appelé plus tard la « Nouvelle Droite », n’avait pas suffisamment mis l’accent sur les spiritualités anciennes-européennes, limitées essentiellement aux panthéons grec et romain, au risque d’engendrer dans les mêmes termes et pour les mêmes raisons une seconde Renaissance, dont j’ai souligné plus haut l’aspect illusoire de la première, cette deuxième fois heureusement débarrassée de la chape de plomb que l’Inquisition, le bras armé du catholicisme, faisait peser à l’époque sur tous les aspects de la vie.

On s’est alors hélas intéressé, si l’on s’en réfère à la trifonctionnalité indo-européenne telle que définie par Georges Dumézil, plus à la deuxième fonction, la fonction guerrière, celle des protecteurs, et à la troisième fonction, la fonction économique, celle des producteurs, qu’à la première fonction, la fonction sacerdotale et royale, la fonction spirituelle, celle des conducteurs, qui régit les deux autres.

On s’est alors hélas intéressé, si l’on s’en réfère à la trifonctionnalité indo-européenne telle que définie par Georges Dumézil, plus à la deuxième fonction, la fonction guerrière, celle des protecteurs, et à la troisième fonction, la fonction économique, celle des producteurs, qu’à la première fonction, la fonction sacerdotale et royale, la fonction spirituelle, celle des conducteurs, qui régit les deux autres.

Je n’ai personnellement jamais été attiré par les écrits des philosophes, anciens ou modernes, dont le jargon prétentieux, en ce qui concerne les seconds, m’ennuyait profondément, ni par ce qu’on a appelé la « Raison » grecque, issue en partie des réflexions des premiers, ni par ce qui a constitué le matérialisme et la force de l’Empire romain, qui a été, selon moi, surtout un système d’oppression sur les peuples européens, à l’image du prométhéisme – du titanisme – triomphant de notre mondialisation actuelle.

Je me suis senti beaucoup plus proche du lyrisme de nos « ancêtres les Gaulois », dont la civilisation empreinte de spiritualité à travers l’enseignement de ses druides a été promptement mise sous le boisseau et nos ancêtres les Gaulois mâtinés en Gallo-Romains.

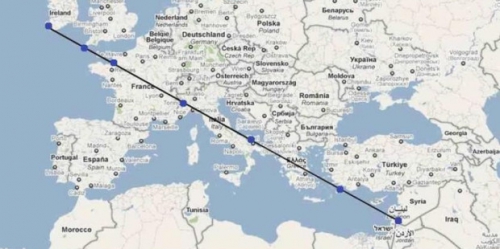

La civilisation celte, qui s’étendait, avant l’Empire romain, sur la quasi-totalité de l’Europe, avait su conserver le mystère et les pulsions intuitives qui la reliait directement aux dieux. Je tente de démontrer, dans La Dame en signe blanc, que les Celtes étaient les descendants des Hyperboréens, dont les anciens Grecs avaient gardé la nostalgie, en témoigne la geste d’Apollon qui leur rendait régulièrement visite.

Avec la création de la revue Hyperborée, j’ai voulu donner un ton plus ésotérique, ou spirituel, à une histoire qui nous projette dans le plus lointain passé indo-européen, le sous-titre de la revue étant « Aux sources de l’Europe ».

Ces sources étant essentiellement constituées par ce qu’on appelle la Tradition primordiale, une culture-racine qui a apporté sa connaissance à l’ensemble des peuples de la planète et dont le siège géographique mythique serait installé au pôle, vraisemblablement sous les glaces.

La revue se réfère régulièrement à d’autres messagers des dieux (expression que j’ai utilisée pour définir Nostradamus) qui, dans des domaines différents ont, surtout par leurs écrits, communiqué les vérités essentielles qui constituent la base de notre grand peuple européen mais aussi son avenir. Nous retrouverons ainsi dans notre revue les noms et les textes d’Oswald Spengler, de Mircea Eliade, de René Guénon, de Julius Evola, d’Alain Daniélou et de quelques autres. Comme nous y incitait logiquement l’approche plus poétique et spirituelle de notre héritage celte, nous nous sommes volontiers intéressés à la poésie et aux auteurs fantastiques comme Tolkien, Lovecraft, Giono (mais oui !), voire aux peintres surréalistes et fantastiques (belges comme Delvaux et Magritte, espagnol comme Dali, ou italien comme Giorgio De Chirico), ou au cinéma de Stanley Kubrick, de John Boorman, de John Milius, de Coppola, de Cimino pour y adjoindre nos frères exilés aux Amériques.

Dès le premier numéro d’Hyperborée est apparue la signature de mon ami le professeur Paul-Georges Sansonetti, le grand spécialiste du monde nordique, de la runologie, du symbolisme et de la guématrie, qui collaborait déjà à Roquefavour et qui a amené dans son sillage d’autres collaborations, venant notamment du mouvement de scoutisme fondé par Jean Mabire, les Oiseaux migrateurs. Le professeur Jean Haudry, incontestable maître de l’indo-européanisme, y a aussi régulièrement collaboré.

La revue, à partir de cette année 2017, ne paraît plus sous sa forme papier mais continue sous sa forme numérique grâce au site Hyperboree.fr, qui regroupe en lecture libre et gratuite l’ensemble de notre production depuis le premier numéro en 2006. D’autre part, ce choix nous permet une plus grande souplesse. Ainsi, je pourrai déployer sur le site un reportage photographique complet sur les sites évoqués dans La Dame en signe blanc, ce qui permettra une meilleure compréhension du livre.

EM : En 2015 paraît La Roue et le Sablier (Bagages pour franchir le gué, Éditions Hyperborée, 2015, 288 p., 20,00 €). Tout d’abord nous devons saluer la qualité de cet ouvrage qui expose de façon claire et concise une vue du monde à la fois traditionaliste, au sens guénonien, et païenne. Ce livre entre-t-il en résonance avec La Dame en Signe Blanc ?

P-ÉB : Le titre, La Roue et le Sablier, indique deux symboles, la roue représente le monde profane qui tourne autour du moyeu qui, lui est fixe, c’est le domaine des dieux qui font tourner le monde, c’est la Tradition primordiale, immuable et pérenne. Plus on se rapproche du centre, du moyeu immobile, et plus on se rapproche du monde spirituel, et, inversement, plus on va vers le grand cercle, celui qui va toucher le sol dur, la terre, et plus on est dans le matériel.

P-ÉB : Le titre, La Roue et le Sablier, indique deux symboles, la roue représente le monde profane qui tourne autour du moyeu qui, lui est fixe, c’est le domaine des dieux qui font tourner le monde, c’est la Tradition primordiale, immuable et pérenne. Plus on se rapproche du centre, du moyeu immobile, et plus on se rapproche du monde spirituel, et, inversement, plus on va vers le grand cercle, celui qui va toucher le sol dur, la terre, et plus on est dans le matériel.

Le sablier représente certes le temps, mais aussi la trifonctionnalité. Au sommet du sablier, la première fonction, celle du prêtre et du roi, celle des conducteurs, puis, au centre, dans le goulet d’étranglement, la deuxième fonction, celle des protecteurs, et en bas, celle des producteurs. Lorsqu’on arrive à la fin d’un cycle, les fonctions sont inversées, celle des producteurs est en haut, en fait, même les producteurs – il y avait une grande noblesse dans le travail du paysan et de l’artisan – ne produisent plus rien, ou plus grand-chose, on fait simplement travailler l’argent (oui, il n’y a que l’argent qui « travaille »), celle des conducteurs est en bas, ils ne conduisent plus rien du tout, ils sont rejetés, décrédibilisés, moqués, celle du milieu, l’armée et la police, est au service de la fonction qui est en haut, quelle qu’elle soit, sans états d’âme. Lorsque le monde retrouve son équilibre après la fin du cycle, le sablier est à nouveau renversé et tout rentre dans l’ordre.

J’ai entièrement adhéré la définition de la première fonction qu’en donne mon ami Pierre Vial dans la dernière livraison de sa revue, Terre et Peuple, n° 73, sur le paganisme, et dont je vous donne la teneur : « Le paganisme de première fonction, lui, a pour mission d’incarner et d’enseigner la conception du monde, de la vie, de l’homme, de l’Histoire qui est la nôtre. C’est le rôle des éveilleurs de peuples qui doivent être, comme le furent les druides, des pédagogues. Mais des pédagogues enseignant d’abord par l’exemple, en se vouant totalement à leur mission et en laissant de côté, donc, tout souci de réussite sociale, d’enrichissement, de renommée intellectuelle, tous ces hochets qui domestiquent l’individu et en font un être soumis à ceux qui, dans notre société, détiennent les pouvoirs, tous les pouvoirs. »

Je me rends compte que c’est la seule citation que j’ai donnée jusqu’à présent dans cet entretien, ceci dit pour en souligner l’importance.

Ce livre, La Roue et le Sablier, a bien sûr un rapport avec La Dame en signe blanc, qui est le premier livre que j’avais écrit; en fait, on peut remarquer que les écrivains (ceux qui ont quelque chose à transmettre, et non pas à gagner) sont comme les peintres qui peignent toujours le même tableau.

EM : Cela est moins le cas dans La Dame en signe Blanc mais nous avions remarqué dans La Roue et le Sablier que vous citiez à plusieurs reprises Rudolf Steiner. Envisagez-vous l’anthroposophie de façon positive, bien que cette « seconde religiosité », pour emprunter l’expression de Spengler, fut durement critiquée par Julius Evola, ou séparez-vous cette doctrine d’une partie de l’œuvre de Steiner ?

EM : Cela est moins le cas dans La Dame en signe Blanc mais nous avions remarqué dans La Roue et le Sablier que vous citiez à plusieurs reprises Rudolf Steiner. Envisagez-vous l’anthroposophie de façon positive, bien que cette « seconde religiosité », pour emprunter l’expression de Spengler, fut durement critiquée par Julius Evola, ou séparez-vous cette doctrine d’une partie de l’œuvre de Steiner ?

P-ÉB : Steiner a employé l’expression « intuition transcendantale » – et nous en revenons au début de cet entretien – qui me paraît plus appropriée que celle d’« intuition intellectuelle » pour dire à peu près la même chose que ce que disaient Guénon et Evola. Je me suis intéressé plus au personnage qu’au concept d’anthroposophie, qu’il a, à mon sens, largement dépassé, par une imagination foisonnante et la création de multiples concepts à l’intérieur du concept principal qui finit par s’effacer : l’eurythmie, la biodynamie (la plupart des vignerons actuels tendent vers cette pratique), l’éducation (les écoles Steiner sont très réputées) et, tout comme Nostradamus, Steiner avait de véritables dons de voyance. En lisant ses conférences, on se perd dans un dédale poétique, surréaliste ou fantastique, qui a aussi existé chez les théosophes de Madame Blavatsky. Je sais bien qu’Evola, et encore plus Guénon, parlant de contre-initiation, ont condamné ces deux courants, il n’en reste pas moins qu’ils ont participé à mon éveil, de la même façon que Le Matin des magiciens, le cultissime ouvrage de Pauwels et Bergier, qui m’a ouvert l’esprit sur des domaines que j’ignorais.

EM : Vous venez donc de rééditer votre ouvrage La Dame en signe Blanc. Pourquoi rééditer ce livre ? Y avez-vous apporté des modifications par rapport à l’édition originale ?

P-ÉB : La Dame en signe blanc est une expression de Nostradamus pour désigner la reine qui dort à côté du Grand Monarque qui est appelé à se réveiller lorsque l’Europe sera en danger de mort, selon la légende.

Je m’étonnais d’une demande récurrente de quelques amis concernant la réédition de cet ouvrage pour lequel j’avais une certaine affection – c’était mon premier – et je m’y suis replongé, il avait des défauts comme tous les livres, et encore plus comme les premiers. Les événements ont fait que les écrits de Nostradamus concernant le Grand Monarque étaient de plus en plus crédibles – quand il disait qu’un grand chef allait se dresser pour combattre une invasion musulmane – et j’ai donc ajouté ce sous-titre à mon ouvrage, La Prophétie du Grand Monarque. J’ai d’autre part également réactualisé mon livre en y ajoutant une fin concernant les prémisses du nouveau cycle que j’entrevois qui, à mon sens, va voir le rapprochement de l’espèce humaine avec celle des autres règnes, végétal et animal, sans quoi, la Terre, qui un être vivant, mourra et ce qui en vit avec.

EM : La perspective de ce livre est fort intéressante car elle s’inscrit dans un cadre local et historique (la région de Roquefavour). « Ce qui est en bas est comme ce qui est en haut », formule ésotérique bien connue, résumerait à merveille le contenu de l’ouvrage…

P-ÉB : Les Celtes, les Gaulois chez nous en l’occurrence, avaient coutume de percevoir le monde en s’appropriant celui que leur vision pouvait englober; le Gaulois était au centre du monde, de son monde; les Bituriges, les habitants gaulois de Bourges, en avaient même fait leur raison d’être : ils étaient « les rois du monde ». Et, de fait, Bourges était bien le centre de la France, donc, les rois de notre pays.

J’ai un peu dépassé ce concept, démontrant d’abord que ce lieu dont je parle, Roquefavour, que j’appelle Le Cercle magique, fut l’un des centres de l’ancien monde, par les événements qui s’y sont déroulés, et suggérant qu’il pourrait être aussi celui qui verra la naissance du nouveau, en accord avec l’un de ses illustres voisins, Nostradamus.

En effet, Nostradamus situe le tombeau, et donc le réveil du Grand Monarque et de son épouse dans le Cercle magique, ou non loin; il situe également non loin du Cercle magique de grandes batailles qui permettront au Grand Monarque d’arrêter les envahisseurs. On pourrait se dire qu’il est bien facile pour le mage de situer tous ces événements sur un territoire qu’il connaît bien – il habitait Salon, à une vingtaine de km du Cercle magique, situé sur la commune de Ventabren – et qu’il y aurait là comme un enfantillage ou une supercherie. Nous pourrions répondre que ce n’est pas le messager des dieux qui situe là ces grands événements, il ne fait que constater ou prédire ce qui aura lieu. Ce sont les dieux, le supra-humain, qui décident. Si ces événements devaient se passer au Japon ou au Canada, nous aurions tout simplement un Nostradamus japonais ou canadien pour en parler.

J’émets l’hypothèse qu’un cycle doit renaître sur les lieux où l’ancien a fini sa course, selon la loi du « témoin » celui d’une course où le coureur passe le témoin à un autre pour accomplir son nouveau tour de piste.

EM : Le livre s’organise autour de trois cycles : l’un païen, le suivant chrétien et le dernier nommé « Ère du Verseau ». Concernant les deux premiers, vous parlez du christianisme comme étant une « religion de coucous », c’est–à–dire qu’elle s’est servie du paganisme pour asseoir son autorité. Dès lors pensez-vous que ce l’on a pour coutume de nommer ésotérisme chrétien n’a de chrétien que le nom ?

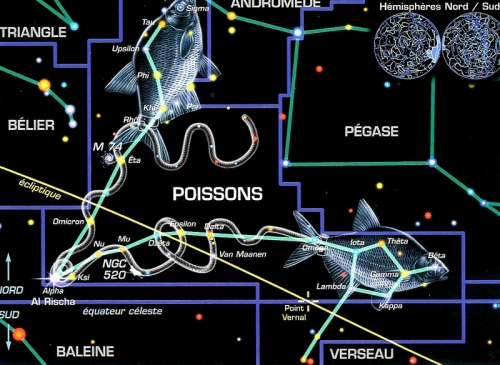

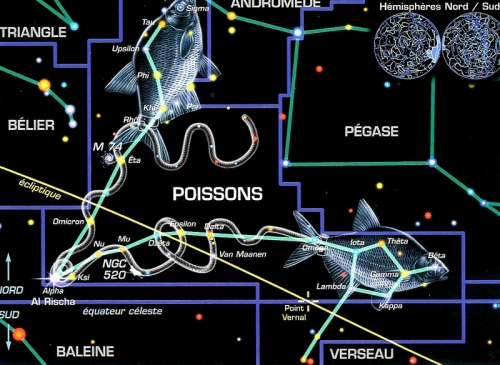

P-ÉB : Je ne fais que me référer au système des cycles et, plus précisément, au système des cycles zodiacaux qui durent chacun 2160 ans. Le cycle païen était placé sous le signe du Bélier, de Mars, de la guerre, cycle initié par Prométhée, le Titan, qui voit, paradoxalement, s’accomplir ses rêves de puissance en notre fin de cycle chrétien; nul ne peut contester que le titanisme – le mondialisme – prend tous ses terribles effets à l’époque que nous vivons. Quel fut le rôle du christianisme dans ce processus, le cycle des Poissons ? Atténuer sa brutalité ou bien la corrompre dans une mièvrerie humaniste ? Ces deux cycles, en y ajoutant celui du Taureau, faisaient déjà partie du Kali-Yuga, le cycle de la fin. Mais s’est perpétuée, à travers tous les cycles, quels qu’ils soient, la pérennité de la Tradition primordiale; l’ésotérisme chrétien constitue cette perpétuation, intangible, à travers notamment les écrits de Saint-Jean sur l’Apocalypse, et, d’autre part, les interventions des druides après leur supposée disparition, notamment dans l’élaboration du concept cistercien, sur le plan architectural et spirituel.

EM : Le dernier cycle qui est en fait l’Ère du Verseau, thème prisé dans les milieux New Age, correspond à la fin de ce que Jean Phaure appelait « Cycle de l’humanité adamique ». Selon ce dernier, la durée de ce cycle serait d’ailleurs indéterminée… Comment envisagez-vous celui-ci ?

P-ÉB : Non, le dernier cycle n’est pas l’ère du Verseau mais bien l’ère des Poissons; nous somme dans cette période transitoire où nous ne savons pas exactement quand finit un cycle et quand commence le nouveau (les nombres bien précis que nous transmettent la Tradition sont vraisemblablement exacts mais comme nous ne savons rien, ou pas grand-chose, de la période où ces cycles auraient commencé, le problème de la datation reste entier). En ce qui concerne le nouveau cycle, je l’ai dit, je pense qu’il y aura un rapprochement des divers règnes, l’homme n’étant plus le prédateur et le déprédateur qu’il a toujours été jusqu’à présent mais bien le régulateur d’un monde que les dieux lui ont confié et qu’il a si mal géré.

EM : La figure du Grand Monarque dont vous parlez n’est pas sans rappeler les annonciateurs/restaurateurs du cycle nouveau tels Baldr, Kalki ou Jésus, mais aussi les rois cachés comme Arthur ou Sébastien. Le nouvel Âge d’Or étant inéluctable, quid de l’action politique durant le Kali-Yuga ?

P-ÉB : Le Grand Monarque n’est pas un avatar, c’est-à-dire un être divin qui descend sur Terre, comme le Christ. Ce serait plutôt une sorte de demi-dieu.

Plusieurs personnages de l’Histoire ont représenté le Grand Monarque, que Nostradamus appelait aussi le Grand Romain, le Grand Celtique, ou le Grand Chyren, ou le Prince Dannemarc, faisant alors référence à l’un de ces personnages légendaires, Ogier le Danois qui était l’un des lieutenants de Charlemagne, qui dort et se réveillera lorsque le Danemark sera en danger, le fameux roi Arthur, chef de guerre celte, qui combattit l’invasion des Germains au VIe siècle, qui est lui aussi en dormition, mais le Grand Monarque, c’est aussi le Khan, titre porté par les chefs mongols, turcs ou chinois. Citons aussi Roderik le Wisigoth qui s’opposa à l’invasion musulmane de ce qui deviendra l’Andalousie. Il serait mort noyé mais son corps ne fut jamais retrouvé. Le Shaoshyant en Iran mazdéen est le nom du Sauveur suprême qui apparaîtra dans les derniers jours du monde.

Chez René Guénon, le Grand Monarque, c’est le Roi du monde, qu’il définit comme le législateur primordial et universel.

Tous ces personnages ont au moins trois points communs :

– Ils sont légendaires, on n’est pas sûr de leurs existences et encore moins de leurs morts.

– Ils dorment d’un long sommeil jusqu’à leur réveil : c’est la dormition.

– Ils sont appelés à être réveillés pour sauver la patrie en danger.

Et, en fait, le Grand Monarque constitue une synthèse de tous ces personnages de légende, un principe universel même car il est appelé à une mission divine.

L’action politique est claire, telle que je l’ai exposé dans La Roue et le Sablier et telle qu’elle est résumée dans le sous-titre « Bagages pour franchir le gué ».

D’abord, il s’agirait de choisir sans état d’âme son camp lorsque l’affrontement guerrier prédit par Nostradamus demandera un engagement total, mais ce n’est pas tout, d’autres actions en amont auront été nécessaires.

Nos ennemis tentent de faire en sorte d’arrêter la roue qui tourne, la robotisation du monde et des hommes annoncée par le transhumanisme va dans ce sens; arrêter le cours du monde signifierait leur victoire, même si cette victoire constituerait aussi une défaite, puisque ses promoteurs, ou leurs héritiers, n’y survivraient pas. Mais leur égoïsme ne se soucie même pas du sort de leurs héritiers, « Après moi, le déluge » est une belle expression pour définir ces nihilistes égotistes. Nous ne savons pas encore si la fin de notre cycle sera caractérisée principalement par un déluge, nous savons que toutes les fins de cycle antérieures à la nôtre, dont Mircea Eliade a collecté les derniers témoignages chez tous les peuples, se traduisent par une conjonction de catastrophes, à la fois humaines et naturelles.

Il nous faut donc rassembler tous les concepts historiques et spirituels qui ont fait la grandeur de l’Europe, une sorte d’Arche de Noé, ou les braises qu’on transporte dans le film, La Guerre du feu, pour pouvoir rallumer le feu en franchissant le gué.

Une autre attitude, mais qui peut être aussi complémentaire, consiste, comme le préconisait Julius Evola, à faire tomber le mur qui menace de s’écrouler; le principe de survie consistant à ne pas se trouver dessous, mais de l’autre côté. Cette méthode revient à précipiter la fin d’un monde qui meurt, le Kali-Yuga, l’Âge de Fer, pour pouvoir accéder plus rapidement au cycle suivant, l’Âge d’Or, qui rétablit l’ordre du cosmos. Ce faisant, paradoxalement, nous pourrions prendre de court ceux qui tentent laborieusement d’empêcher sa venue.

Propos recueillis par Thierry Durolle

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

Guénon rajoute dans une note passionnante :

Guénon rajoute dans une note passionnante :

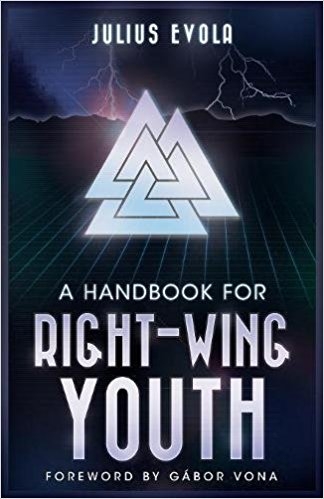

Publié à l’origine en hongrois fin 2012 en tant qu’anthologie des articles d’Evola sur la jeunesse et la Droite, A Handbook For Right-Wing Youth (Un manuel pour la jeunesse de Droite) est maintenant disponible grâce à Arktos en anglais. Nous espérons qu’une version française verra le jour tôt ou tard. En effet, l’influence d’Evola sur la désormais célèbre Nouvelle Droite française et tous ses héritiers (des identitaires aux militants nationalistes-révolutionnaires et traditionalistes radicaux), sans oublier le fondateur du présent site, Georges Feltin-Tracol (4), et certains contributeurs tels Daniel Cologne (5) et votre serviteur lui-même, est tout simplement énorme.

Publié à l’origine en hongrois fin 2012 en tant qu’anthologie des articles d’Evola sur la jeunesse et la Droite, A Handbook For Right-Wing Youth (Un manuel pour la jeunesse de Droite) est maintenant disponible grâce à Arktos en anglais. Nous espérons qu’une version française verra le jour tôt ou tard. En effet, l’influence d’Evola sur la désormais célèbre Nouvelle Droite française et tous ses héritiers (des identitaires aux militants nationalistes-révolutionnaires et traditionalistes radicaux), sans oublier le fondateur du présent site, Georges Feltin-Tracol (4), et certains contributeurs tels Daniel Cologne (5) et votre serviteur lui-même, est tout simplement énorme.

Hélas, une partie non négligeable des livres de René Guénon ne sont plus disponible, notamment ceux édités par les Éditions Traditionnelles. Il fallait donc chiner chez les libraires ou sur le Net afin de trouver, parfois à des prix prohibitifs, certains ouvrages. Mais ça c’était avant, car les éditons Omnia Veritas (1) viennent de rééditer les dix-sept ouvrages majeurs de René Guénon ainsi que quelques recueils posthumes tels Études sur l’hindouisme (2). C’est un véritable plaisir de redécouvre certains travaux de Guénon comme L’erreur spirite (3), Aperçus sur l’ésotérisme chrétien (4) ou L’homme et son devenir selon le Vêdânta (5) pour un rapport qualité/prix plus que correct.

Hélas, une partie non négligeable des livres de René Guénon ne sont plus disponible, notamment ceux édités par les Éditions Traditionnelles. Il fallait donc chiner chez les libraires ou sur le Net afin de trouver, parfois à des prix prohibitifs, certains ouvrages. Mais ça c’était avant, car les éditons Omnia Veritas (1) viennent de rééditer les dix-sept ouvrages majeurs de René Guénon ainsi que quelques recueils posthumes tels Études sur l’hindouisme (2). C’est un véritable plaisir de redécouvre certains travaux de Guénon comme L’erreur spirite (3), Aperçus sur l’ésotérisme chrétien (4) ou L’homme et son devenir selon le Vêdânta (5) pour un rapport qualité/prix plus que correct.

Y a–t-il une Provence secrète ? Il semblerait bien que oui. Pierre-Émile Blairon a eu l’excellente idée de rééditer son livre La Dame en signe blanc (La prophétie du Grand Monarque, Éditions Hyperborée, 2017, 284 p., 20,00 €) qui plonge le lecteur dans les mystères de la région de Roquefavour, entre Graal païen et prédictions de Nostradamus. Il n’en fallait pas plus pour qu’Europe Maxima se décide à l’interroger.

Y a–t-il une Provence secrète ? Il semblerait bien que oui. Pierre-Émile Blairon a eu l’excellente idée de rééditer son livre La Dame en signe blanc (La prophétie du Grand Monarque, Éditions Hyperborée, 2017, 284 p., 20,00 €) qui plonge le lecteur dans les mystères de la région de Roquefavour, entre Graal païen et prédictions de Nostradamus. Il n’en fallait pas plus pour qu’Europe Maxima se décide à l’interroger.

On s’est alors hélas intéressé, si l’on s’en réfère à la trifonctionnalité indo-européenne telle que définie par Georges Dumézil, plus à la deuxième fonction, la fonction guerrière, celle des protecteurs, et à la troisième fonction, la fonction économique, celle des producteurs, qu’à la première fonction, la fonction sacerdotale et royale, la fonction spirituelle, celle des conducteurs, qui régit les deux autres.

On s’est alors hélas intéressé, si l’on s’en réfère à la trifonctionnalité indo-européenne telle que définie par Georges Dumézil, plus à la deuxième fonction, la fonction guerrière, celle des protecteurs, et à la troisième fonction, la fonction économique, celle des producteurs, qu’à la première fonction, la fonction sacerdotale et royale, la fonction spirituelle, celle des conducteurs, qui régit les deux autres. P-ÉB : Le titre, La Roue et le Sablier, indique deux symboles, la roue représente le monde profane qui tourne autour du moyeu qui, lui est fixe, c’est le domaine des dieux qui font tourner le monde, c’est la Tradition primordiale, immuable et pérenne. Plus on se rapproche du centre, du moyeu immobile, et plus on se rapproche du monde spirituel, et, inversement, plus on va vers le grand cercle, celui qui va toucher le sol dur, la terre, et plus on est dans le matériel.

P-ÉB : Le titre, La Roue et le Sablier, indique deux symboles, la roue représente le monde profane qui tourne autour du moyeu qui, lui est fixe, c’est le domaine des dieux qui font tourner le monde, c’est la Tradition primordiale, immuable et pérenne. Plus on se rapproche du centre, du moyeu immobile, et plus on se rapproche du monde spirituel, et, inversement, plus on va vers le grand cercle, celui qui va toucher le sol dur, la terre, et plus on est dans le matériel.  EM :

EM :

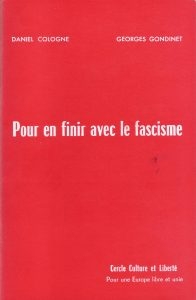

En effet, les fascismes – non pas uniquement le fascisme italien – en tant que phénomènes politiques, doivent d’être étudiés et leurs résultats longuement médités. En 1977, Georges Gondinet et Daniel Cologne se prononcent sur cette épineuse question avec leur fascicule Pour en finir avec le fascisme. Essai de critique traditionaliste-révolutionnaire (1). L’objectif de ce roboratif essai au titre provocateur consiste tout d’abord à mettre dos à dos les deux « mythologisations » du fascisme : la première positive, émanant des milieux dit d’extrême droite; la seconde provenant des ennemis du fascisme, soit le libéralisme et le marxisme. Les auteurs se posent en « héritiers partiels et lucides ». Leur critique du phénomène fasciste s’inscrit donc dans une troisième voie où dominent l’influence de la Tradition Primordiale et le recul historique.

En effet, les fascismes – non pas uniquement le fascisme italien – en tant que phénomènes politiques, doivent d’être étudiés et leurs résultats longuement médités. En 1977, Georges Gondinet et Daniel Cologne se prononcent sur cette épineuse question avec leur fascicule Pour en finir avec le fascisme. Essai de critique traditionaliste-révolutionnaire (1). L’objectif de ce roboratif essai au titre provocateur consiste tout d’abord à mettre dos à dos les deux « mythologisations » du fascisme : la première positive, émanant des milieux dit d’extrême droite; la seconde provenant des ennemis du fascisme, soit le libéralisme et le marxisme. Les auteurs se posent en « héritiers partiels et lucides ». Leur critique du phénomène fasciste s’inscrit donc dans une troisième voie où dominent l’influence de la Tradition Primordiale et le recul historique. La question du matérialisme biologique, c’est-à-dire de la race, figure parmi les sujets évoqués dans cet essai. En bon évoliens, les auteurs condamnent le racisme biologique national-socialiste et adoptent sans réelle surprise les positions de Julius Evola exprimées dans Synthèse de doctrine de la race (2). « La pureté de la race ainsi comprise résulte de l’équilibre entre les trois niveaux existentiels : l’esprit, l’âme, et le corps. Il n’y a pas de pureté raciale sans une totalité de l’être, un parfait accord entre ses traits somatiques, ses dispositions psychiques et ses tendances spirituelles (p. 24). » Les auteurs en arrivent à la conclusion que la race de l’esprit, qu’ils nomment « générisme » est « la condition sine qua non du dépassement du fascisme, du retour à un traditionalisme véritable, de l’effort vers une révolution authentique (p. 25) ».

La question du matérialisme biologique, c’est-à-dire de la race, figure parmi les sujets évoqués dans cet essai. En bon évoliens, les auteurs condamnent le racisme biologique national-socialiste et adoptent sans réelle surprise les positions de Julius Evola exprimées dans Synthèse de doctrine de la race (2). « La pureté de la race ainsi comprise résulte de l’équilibre entre les trois niveaux existentiels : l’esprit, l’âme, et le corps. Il n’y a pas de pureté raciale sans une totalité de l’être, un parfait accord entre ses traits somatiques, ses dispositions psychiques et ses tendances spirituelles (p. 24). » Les auteurs en arrivent à la conclusion que la race de l’esprit, qu’ils nomment « générisme » est « la condition sine qua non du dépassement du fascisme, du retour à un traditionalisme véritable, de l’effort vers une révolution authentique (p. 25) ».

En toda esta trayectoria hemos percibido la necesidad de seguir profundizando en la vía de la espiritualidad, y si en su momento hemos querido mostrar perspectivas muy concretas del mundo islámico, ahora, en estos tiempos en los que la religiosidad y las grandes verdades del Espíritu se han visto erosionadas de forma irreversible, consideramos que cierta visión tradicional del Catolicismo se integraba perfectamente en los propósitos y finalidades que, desde nuestros inicios, hemos proyectado. Dentro de las corrientes del tradicionalismo católico podríamos incluir al propio

En toda esta trayectoria hemos percibido la necesidad de seguir profundizando en la vía de la espiritualidad, y si en su momento hemos querido mostrar perspectivas muy concretas del mundo islámico, ahora, en estos tiempos en los que la religiosidad y las grandes verdades del Espíritu se han visto erosionadas de forma irreversible, consideramos que cierta visión tradicional del Catolicismo se integraba perfectamente en los propósitos y finalidades que, desde nuestros inicios, hemos proyectado. Dentro de las corrientes del tradicionalismo católico podríamos incluir al propio  Attilio Mordini, autor de la presente obra, fue un autor muy especial, tanto a nivel literario, como pensador, así como en su propia vida personal. Su paso por este mundo fue relativamente corto y accidentado. De origen florentino, vivió unos años dramáticos, los más trascendentales del pasado siglo, y acabó participando como voluntario en el Frente del Este durante la Segunda Guerra Mundial. Durante los últimos años de guerra se adhirió a la República Social Italiana, y cuando ésta cayó acabó vagando por Italia, camino de Roma. Finalmente, como ocurrió con muchos combatientes italianos que apoyaron el régimen precedente, Mordini acabó siendo detenido por los partisanos y sometido a un juicio del que finalmente sería absuelto. Durante su estancia en la cárcel sufrió todo tipo de penalidades y maltratos, que a muy temprana edad le hicieron contraer tuberculosis, una

Attilio Mordini, autor de la presente obra, fue un autor muy especial, tanto a nivel literario, como pensador, así como en su propia vida personal. Su paso por este mundo fue relativamente corto y accidentado. De origen florentino, vivió unos años dramáticos, los más trascendentales del pasado siglo, y acabó participando como voluntario en el Frente del Este durante la Segunda Guerra Mundial. Durante los últimos años de guerra se adhirió a la República Social Italiana, y cuando ésta cayó acabó vagando por Italia, camino de Roma. Finalmente, como ocurrió con muchos combatientes italianos que apoyaron el régimen precedente, Mordini acabó siendo detenido por los partisanos y sometido a un juicio del que finalmente sería absuelto. Durante su estancia en la cárcel sufrió todo tipo de penalidades y maltratos, que a muy temprana edad le hicieron contraer tuberculosis, una

This mammoth volume is a collection of twenty distinct philosophical reflections written over the course of a decade. Most of them are essays, some almost of book length. Others would be better described as papers. A few are well structured notes. There is also one lecture. A magnum opus like Prometheus and Atlas does not emerge from out of a vacuum, and an alternative title to these collected works could have been “The Path to Prometheus and Atlas.” While there are a few pieces that postdate not only that book but also World State of Emergency, most of the texts included here represent the formative phase of my thought. Consequently, concepts such as “the spectral revolution” and “mercurial hermeneutics” are originally developed in these essays.

This mammoth volume is a collection of twenty distinct philosophical reflections written over the course of a decade. Most of them are essays, some almost of book length. Others would be better described as papers. A few are well structured notes. There is also one lecture. A magnum opus like Prometheus and Atlas does not emerge from out of a vacuum, and an alternative title to these collected works could have been “The Path to Prometheus and Atlas.” While there are a few pieces that postdate not only that book but also World State of Emergency, most of the texts included here represent the formative phase of my thought. Consequently, concepts such as “the spectral revolution” and “mercurial hermeneutics” are originally developed in these essays.

Footnotes:

Footnotes:

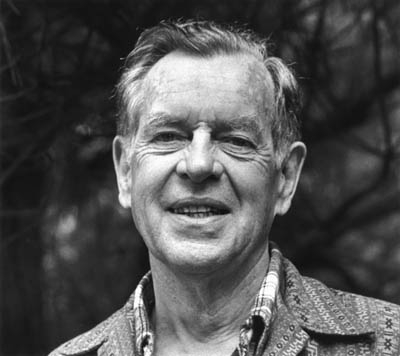

It was during his travels to Europe and Asia during the 1920s and ‘30s, as well as a great deal of wide reading while living in a shack in Woodstock, New York, that Campbell developed his interest in world mythology. He also discovered the ideas of C. G. Jung, which were to profoundly influence all of his work. Indeed, he participated in many of the early and historic Eranos conferences in Switzerland alongside not only Jung himself, but such luminaries as Mircea Eliade, Karl Kerényi, and Henry Corbin, among many others. In 1934 Campbell was hired as a professor at Sarah Lawrence College in New York, a position he was to hold until his retirement in 1972, after which he and his wife moved to Honolulu, Hawaii.

It was during his travels to Europe and Asia during the 1920s and ‘30s, as well as a great deal of wide reading while living in a shack in Woodstock, New York, that Campbell developed his interest in world mythology. He also discovered the ideas of C. G. Jung, which were to profoundly influence all of his work. Indeed, he participated in many of the early and historic Eranos conferences in Switzerland alongside not only Jung himself, but such luminaries as Mircea Eliade, Karl Kerényi, and Henry Corbin, among many others. In 1934 Campbell was hired as a professor at Sarah Lawrence College in New York, a position he was to hold until his retirement in 1972, after which he and his wife moved to Honolulu, Hawaii. Moyers, a well-respected figure in broadcasting, filmed a series of interviews with Campbell during the mid-1980s, mostly at Skywalker Ranch, that were edited into six one-hour episodes and broadcast on PBS in 1988, along with an accompanying

Moyers, a well-respected figure in broadcasting, filmed a series of interviews with Campbell during the mid-1980s, mostly at Skywalker Ranch, that were edited into six one-hour episodes and broadcast on PBS in 1988, along with an accompanying  Regardless of whether these accusations are true or not, they follow a pattern that is typical for any artist or scholar who refuses to tow the party line. If Campbell had been engaged in “deconstructing” mythology, and showing that the Mahabharata or the Arthurian legends were nothing more than “narratives” expressing patriarchy and sexual repression for example, his personal failings in the eyes of academia would have been ignored. Surely what really bothers academics about Campbell, as well as about scholars with a similar worldview such as Jung, Mircea Eliade, or René Guénon, is that they dared to assert that there is an essential meaning to things, which of course then implies that there may actually be such a thing as values and traditions that are worth preserving.

Regardless of whether these accusations are true or not, they follow a pattern that is typical for any artist or scholar who refuses to tow the party line. If Campbell had been engaged in “deconstructing” mythology, and showing that the Mahabharata or the Arthurian legends were nothing more than “narratives” expressing patriarchy and sexual repression for example, his personal failings in the eyes of academia would have been ignored. Surely what really bothers academics about Campbell, as well as about scholars with a similar worldview such as Jung, Mircea Eliade, or René Guénon, is that they dared to assert that there is an essential meaning to things, which of course then implies that there may actually be such a thing as values and traditions that are worth preserving. Surely a large part of the success of The Power of Myth, as it certainly was in my case, was due to the fact that Campbell comes across in his recorded interviews and lectures as an extremely likeable man with a gift for communicating complex ideas and stories in simple language. He was the very embodiment of your favorite teacher, who (hopefully) turned you on to the wonders of the world of ideas and filled you with the fiery passion to learn more about a particular subject. Like the very best teachers, what you learned from him only marked the starting point in a long odyssey that ended up leading you to other ideas and other destinations in life.

Surely a large part of the success of The Power of Myth, as it certainly was in my case, was due to the fact that Campbell comes across in his recorded interviews and lectures as an extremely likeable man with a gift for communicating complex ideas and stories in simple language. He was the very embodiment of your favorite teacher, who (hopefully) turned you on to the wonders of the world of ideas and filled you with the fiery passion to learn more about a particular subject. Like the very best teachers, what you learned from him only marked the starting point in a long odyssey that ended up leading you to other ideas and other destinations in life.

La troisième période, la plus longue, s’étire de 1930 à 1951 et correspond à l’accomplissement doctrinal. Retiré dans la ville du Caire, et bientôt marié à une égyptienne, Guénon a tout le loisir d’affiner les éléments de son système et de préciser plusieurs notions importantes, telles que l’initiation, la réalisation métaphysique, le sens du symbolisme, etc. Tout ce travail aurait peut-être été vain s’il ne s’était constitué autour de lui une petite équipe entièrement dévouée à sa pensée, une revue (Le Voile d’Isis, Études Traditionnelles) qui lui servait de relais avec le monde dit « traditionnel » et, bientôt, des groupes initiatiques qui vont constituer le principal lieu de résonance du système guénonien, aussi bien en théorie qu’en pratique. A ce titre, il faut bien avouer que Guénon a écrit un nouveau chapitre des modalités de la réception des idées, celui de réussir à concilier engagement spirituel et combat (méta)politique.

La troisième période, la plus longue, s’étire de 1930 à 1951 et correspond à l’accomplissement doctrinal. Retiré dans la ville du Caire, et bientôt marié à une égyptienne, Guénon a tout le loisir d’affiner les éléments de son système et de préciser plusieurs notions importantes, telles que l’initiation, la réalisation métaphysique, le sens du symbolisme, etc. Tout ce travail aurait peut-être été vain s’il ne s’était constitué autour de lui une petite équipe entièrement dévouée à sa pensée, une revue (Le Voile d’Isis, Études Traditionnelles) qui lui servait de relais avec le monde dit « traditionnel » et, bientôt, des groupes initiatiques qui vont constituer le principal lieu de résonance du système guénonien, aussi bien en théorie qu’en pratique. A ce titre, il faut bien avouer que Guénon a écrit un nouveau chapitre des modalités de la réception des idées, celui de réussir à concilier engagement spirituel et combat (méta)politique.

De nos jours, la « discussion » est devenue une marchandise, le produit vendable des nouvelles par câble et des revues d’opinion; il n’y a plus même le prétexte d’une « recherche de la vérité ».

De nos jours, la « discussion » est devenue une marchandise, le produit vendable des nouvelles par câble et des revues d’opinion; il n’y a plus même le prétexte d’une « recherche de la vérité ». Nous voyons, cependant, que la négociation ne bouge que dans une seule direction. Par exemple, supposons que j’offre 50 $ pour un produit et que le vendeur demande 100 $. Nous négocions pour 75 $. Le vendeur connaît alors ma limite. Donc la prochaine fois que nous négocions, nous commençons à 75 $ et il exige 125 $. Si, par indécision, ou si je manque de volonté pour tenir ferme, vous pouvez voir que le prix va continuer à augmenter. Ainsi, les conflits sociaux continuent d’être résolus dans un seul sens, malgré les intentions des conservateurs de maintenir le statu quo, et, en tout cas, continue à « évoluer » dans la même direction.

Nous voyons, cependant, que la négociation ne bouge que dans une seule direction. Par exemple, supposons que j’offre 50 $ pour un produit et que le vendeur demande 100 $. Nous négocions pour 75 $. Le vendeur connaît alors ma limite. Donc la prochaine fois que nous négocions, nous commençons à 75 $ et il exige 125 $. Si, par indécision, ou si je manque de volonté pour tenir ferme, vous pouvez voir que le prix va continuer à augmenter. Ainsi, les conflits sociaux continuent d’être résolus dans un seul sens, malgré les intentions des conservateurs de maintenir le statu quo, et, en tout cas, continue à « évoluer » dans la même direction.