POR

Maquetación y correciones: Manuel Q.

Colección: Minnesänger

Papel blanco 90gr.

En poursuivant votre navigation sur ce site, vous acceptez l'utilisation de cookies. Ces derniers assurent le bon fonctionnement de nos services. En savoir plus.

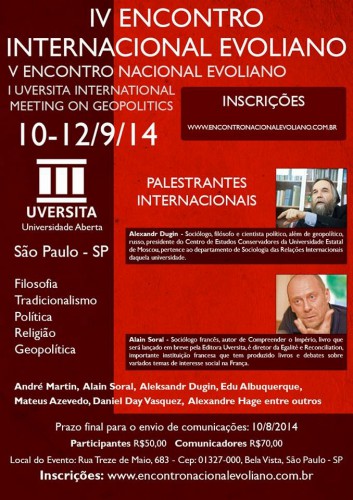

00:05 Publié dans Evénement, Traditions | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : événement, brésil, sao paulo, amérique latine, amérique du sud, alexandre douguine, alain soral, julius evola, tradition, traditionalisme |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

00:05 Publié dans Livre, Livre, Philosophie, Traditions | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : livre, philosophie, tradition, traditionalisme |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

Diálogo sobre la Teoría del Mundo Cúbico.- EMInves ha publicado una recopilación de artículos, corregidos y aumentados, acompañados de una conclusión, titulada Teoría del Mundo Cúbico. El libro ha aparecido precisamente la misma semana en la que menos de la mitad del electorado acudía a las urnas para elegir sus representantes en Europa y quizás sea este hecho por el que convenga empezar el diálogo con su autor, Ernesto Milá:

– Nuestro pueblo no parece ha estado muy interesado por las elecciones europeas… ¿Cómo sitúan en su libro a la Unión Europea?

– Es simple: la UE podía haberlo sido todo y, sin embargo, ha optado por no ser nada. La UE podía haberse constituido como una de las “patas” de un mundo multipolar, una de las zonas con mejor nivel de vida y bienestar de las poblaciones. Y, sin embargo, ha preferido ser una pieza más de un mundo globalizado y, como tal, una víctima más de esa odiosa concepción económico–política que aspira a homogeneizar el mundo en función de los intereses de la economía financiera y especulativa.

– Así pues, no hay futuro para Europa dentro de la globalización…

– Exacto, desde hace 25 años, Europa viene siendo víctima de un doble fenómeno: de un lado la deslocalización industrial en virtud de la cual, las plantas productoras de manufacturas tienden a abandonar territorio europeo y a trasladarse a zonas del planeta con menos coberturas sociales y, especialmente, salarios más bajos; de otro lado, la inmigración masiva traslada masas ingentes del “tercer mundo” hacia Europa con la finalidad de aumentar la fuerza de trabajo a disposición, logrando así tirar a la baja de los salarios. Ambos procesos –deslocalización industrial e inmigración masiva– tienden a rentabilizar el rendimiento del capital: se produce más barato fuera de Europa y lo que no hay más remedio que se fabrique en Europa, cuesta menos gracias a la inmigración masiva. Eufemísticamente, a este proceso, se le llama “ganar competitividad” y registra en su nómina a una ínfima minoría de beneficiarios y a una gran masa de damnificados. Por eso es rechazable.

– Hablando de “modelos”, en la introducción dices que tu Teoría del Mundo Cúbico es un modelo de interpretación de la modernidad, ¿puedes ampliarnos esta idea?

– Lo esencial de toda teoría política es interpretar el mundo en función de un esquema propio que ayude a explicar la génesis de la coyuntura histórica que se vive y cuál será su evolución futura. Esto es hasta tal punto necesario que, sin esto, puede decirse que ninguna doctrina política, ninguna concepción del mundo, logrará definir los mecanismos estratégicos para modificar aquellos aspectos de la realidad que le resulten rechazables o discordantes. Para que un modelo de interpretación de la realidad sea eficiente, es preciso que integre los aspectos esenciales del fenómeno que analiza. Los modelos geométricos son particularmente interesantes por lo que tienen de “visual”. De entre ellos, el cubo es, sin duda, el que mejor se adapta a la globalización y, por tanto, es el que hemos utilizado para nuestro análisis.

– Así pues, si no se comprende bien lo que es la globalización, ¿más vale no intentar aventuras políticas?

– Exactamente. Cuando emprendes un viaje, una aventura, debes llevar contigo un mapa. El mapa es, en definitiva, el modelo de interpretación que te llevará del lugar en el que te encuentras a aquel otro al que quieres llegar. Nadie sensato se atrevería a iniciar un viaje sin disponer de un plano susceptible de indicarle en cada momento dónde se encuentra y si va por la buena o por la mala dirección. Hoy, el factor dominante de nuestra época es el mundialismo y la globalización; el primero sería de naturaleza ideológica y en el segundo destaca su vertiente económica, especialmente. ¿Qué podríamos proponer a la sociedad si ignorásemos lo que es la globalización? Incluso Cristóbal Colón tenía una idea clara de a dónde quería ir; para él, su modelo de interpretación era la esfera; sabía pues que si partía de una orilla del mar, necesariamente, en algún lugar, llegaría a otra orilla. Desconocer lo que es la globalización y sus procesos supone no asentar la acción política sobre bases falsas y, por supuesto, una imposibilidad para elegir una estrategia de rectificación.

– ¿Qué pretendes transmitir a través de estas páginas?

– En primer lugar la sensación de que la globalización es el factor esencial de nuestro tiempo. Luego, negar cualquier virtud al sistema mundial globalizado, acaso, el peor de todos los sistemas posibles y, desde luego, la última consecuencia del capitalismo que inició su ascenso en Europa a partir del siglo XVII. Tras el capitalismo industrial, tras el capitalismo multinacional, no podía existir una fase posterior que no fuera especulativa y financiera a escala planetaria. Cuando George Soros o cualquier otro de los “señores del dinero” vierten alabanzas sobre la globalización, lo hacen porque forman parte de una ínfima minoría de beneficiarios que precisan de un solo mercado mundial para enriquecerse segundo a segundo, al margen de que la inmensa mayoría del planeta, también segundo a segundo, se vaya empobreciendo simétricamente. En la globalización hay “beneficiarios” y “damnificados”, sus intereses con incompatibles. Finalmente, quería llamar la atención sobre la rapidez de los procesos históricos que han ocurrido desde la Caída del Muro de Berlín. Lejos de haber llegado el tiempo el “fin de la historia”, lo que nos encontramos es con una “aceleración de la historia” en la que e están quemando etapas a velocidad de vértigo. La globalización que emerge a partir de 1989, en apenas un cuarto de siglo, ha entrado en crisis. En 2007, la crisis de las suprime inauguró la serie de crisis en cadena que recorren el planeta desde entonces, crisis inmobiliarias, crisis financieras, crisis bancarias, crisis de deuda, crisis de paro, etc, etc. En cada una de estas crisis, da la sensación de que el sistema mundial se va resquebrajando, pero que se niega a rectificar las posiciones extremas hacia las que camina cada vez de manera más vertiginosa. Con apenas 25 años, la globalización está hoy en crisis permanente. Así pues, lo que pretendo transmitir es por qué no hay salida dentro de la globalización.

– ¿Y por qué no hay salida…?

– La explicación se encuentra precisamente en el modelo interpretativo que propongo: está formado por un cubo de seis caras, opuestas dos a dos; así por ejemplo, tenemos a los beneficiarios de la globalización en la cara superior y a los damnificados por la globalización en la cara inferior; a los actores geopolíticos tradicionales a un lado y a los actores geopolíticos emergentes de otro; al progreso científico que encuentra su oposición en la neodelincuencia que ha aparecido por todas partes. Así pues tenemos un cubo con seis caras, doce aristas en las que confluyen caras contiguas y ocho vértices a donde van a parar tres caras en cada uno. Así pues, del análisis de cada una de estas caras y de sus contradicciones entre sí, de las aristas, que nos indicarán las posibilidades de convivencia o repulsión entre aspectos contiguos y de los vértices que nos dirá si allí se generan fuerzas de atracción o repulsión que mantengan la cohesión del conjunto o tiendan a disgregarlo respectivamente, aparece como conclusión el que las fuerzas centrípetas que indican posibilidades de estallido de la globalización se manifiestan en todos los vértices del cubo, así como las fricciones en las aristas, y hacen, teóricamente imposible, el que pueda sobrevivir durante mucho tiempo la actual estructura del poder mundial globalizado.

– ¿Quiénes son los “amos del mundo”? ¿Los “señores del dinero”…?

– En primer lugar es preciso desembarazarse de teorías conspiranoicas. Si el mundo estuviera dirigido por una “logia secreta” o por unos “sabios de Sión”, al menos sabríamos hacia donde nos pretenden llevar y existiría una “inteligencia secreta”, un “plan preestablecido”. Lo más terrible es que ni siquiera existe eso. El capitalismo financiero y especulador ha dado vida a un sistema que ya es controlado por ninguna persona, ni por ningún colectivo, ni institución. Simplemente, la evolución del capitalismo en su actual fase de desarrollo está completamente fuera de control de cualquier inteligencia humana. De ahí que en nuestro modelo interpretativo, la cara superior del cubo –la que representa a los beneficiarios de la globalización– no sea plana sino que tenga la forma de un tronco de pirámide. En el nivel superior de esta estructura piramidal truncada se encuentran las grandes acumulaciones de capital, lo que solemos llamar “los señores del dinero”… pero no constituyen ni un “sanedrín secreto”, ni siquiera pueden orientar completamente los procesos de la economía mundial. Simplemente, insisto, la economía se ha convertido en un caballo desbocado, que escapa a cualquier control…

– Entonces… ¿quién dirige el mundo?

– … efectivamente, esta es la pregunta que faltaba. En mi modelo, esta pirámide truncada, está coronada por una pieza homogénea que está por encima de todo el conjunto. En los obeliscos antiguos esta pieza era dorada o, simplemente, hecha de oro, y se conocía como “pyramidion”. En la globalización ese “pyramidion” son los valores de los que se nutre el neocapitalismo: afán de lucro, búsqueda insensata del mayor beneficio especulativo, etc, en total veinte principios doctrinales que enuncio en el último capítulo de la obra y que constituyen lo que podemos considerar como “la religión de los señores del dinero”. Esos “principios” son los que verdaderamente “dirigen la globalización”. Los “señores del dinero” no son más que sus “fieles devotos”, pero no tienen ningún control sobre los dogmas de su religión.

– ¿Hay alternativa a la globalización?

– Sí, claro, ante: la llamada “economía de los grandes espacios”. Reconocer que el mundo es demasiado diverso y que un sistema mundial globalizado es completamente imposible. Reconocer que solamente espacios económicos más o menos homogéneos, con similares PIB, con similar cultura, sin abismos ni brechas antropológicas, pueden constituir “unidades económicas” y que, cada uno de estos espacios, debe estar protegido ante otros en donde existan condiciones diferentes de producción, por barreras arancelarias. Y, por supuesto, que el capital financiero debe estar en primer lugar ligado a una nación y en segundo lugar tributar como actividad parasitaria y no productiva. La migración constante del capital financiero en busca siempre de mayores beneficios es lo que genera, a causa de su movilidad, inestabilidad internacional. Hace falta poner barreras para sus migraciones y disminuir su impacto, no sólo en la economía mundial, sino también en la economía de las naciones. Los Estados deben desincentivar las migraciones del capital especulativo y favorecer la inversión productiva, industrial y científica.

– ¿Es posible vencer a la globalización?

– La globalización tiene dos grandes enemigos: en primer lugar, los Estados–Nación que disponen todavía de un arsenal legislativo, institucional y orgánico para defender la independencia y la soberanía nacionales de cualquier asalto, incluido el de los poderes económicos oligárquicos y apátridas; se entiende, que una de las consignas sagradas del neoliberalismo sea “más mercado, menos Estado”, que garantiza que los intereses económicos de los propietarios del capital se impongan con facilidad sobre los derechos de las poblaciones que deberían estar defendidos y protegidos por el Estado, en tanto que encarnación jurídica de la sociedad. El otro, gran enemigo de la globalización es cualquier sistema de “identidades” que desdicen el universalismo que se propone desde los laboratorios ideológicos de la globalización (la UNESCO, ante todo) y son antagónicos con los procesos de homogeneización cultural y antropológica que acompañan a la globalización económica. Así pues está claro: para vencer a la globalización es preciso reivindicar la dignidad superior del Estado (y para ello hace falta crear una nueva clase política digna de gestionarlo) e incluso recuperar la idea de Estado como expresión jurídica de la sociedad, es decir, de todos (con todo lo que ello implica) y, por otra parte, es preciso reafirmar las identidades nacionales, étnicas, regionales. Allí donde haya Estado e Identidad, allí no hay lugar para la globalización.

Datos técnicos:

Tamaño: 15 x 23 cm

Páginas: 258

Pvp: 20,00 euros

Abundante ilustrado con gráficos

pedidos: eminves@gmail.com

00:05 Publié dans Livre, Livre, Philosophie, Traditions | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : tradition, ernesto mila, monde cubique, philosophie, traditionalisme, livre, espagne |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

MERCURY RISING: THE LIFE & WRITINGS OF JULIUS EVOLA

If the industrious man, through taking action,

Does not succeed, he should not be blamed for that –

He still perceives the truth.

~The Sauptikaparvan of the Mahābhārata (2,16)

|

| Sir John Woodroffe |

"Our Activity in 1930 – To the Readers: Krur is transforming. Having fulfilled the tasks relative to the technical mastery of esotericism we proposed for ourselves three years ago, we have accepted the invitation to transfer our action to a vaster, more visible, more immediate field: the very plane of Western 'culture' and the problems that, in this moment of crisis, afflict both individual and mass consciousness […] for all these reasons Krur will be changed to the title La Torre (The Tower), a work of diverse expressions and one Tradition."[7]

"Someone reported this argument [that the death of a head of state might be brought about by magic] and some yarn about our already dissolved 'chain of Ur' may also have been added, all of which led the Duce to think that there was a plot to use magic against him. But when he heard the true facts of the matter, Mussolini ceased all action against us. In reality Mussolini was very open to suggestion and also somewhat superstitious (the reaction of a mentality fundamentally incapable of true spirituality). For example, he had a genuine fear of fortune-tellers and any mention of them was forbidden in his presence."

"During the last years of the 1930s I devoted myself to working on two of my most important books on Eastern wisdom: I completely revised L’uomo come potenza (Man As Power), which was given a new title, Lo yoga della potenza (The Yoga of Power), and wrote a systematic work concerning primitive Buddhism entitled La dottrina del risveglio (The Doctrine of Awakening)."[14]

"To live and understand the symbol of the Grail in its purity would mean today the awakening of powers that could supply a transcendental point of reference for it, an awakening that could show itself tomorrow, after a great crisis, in the form of an “epoch that goes beyond nations.” It would also mean the release of the so-called world revolution from the false myths that poison it and that make possible its subjugation through dark, collectivistic, and irrational powers. In addition, it would mean understanding the way to a true unity that would be genuinely capable of going beyond not only the materialistic – we could say Luciferian and Titanic – forms of power and control but also the lunar forms of the remnants of religious humility and the current neospiritualistic dissipation."[17]

"But in this study, metaphysics will also have a second meaning, one that is not unrelated to the world's origin since 'metaphysics' literally means the science of that which goes beyond the physical. In our research, this 'beyond the physical' will not cover abstract concepts or philosophical ideas, but rather that which may evolve from an experience that is not merely physical, but transpsychological and transphysiological. We shall achieve this through the doctrine of the manifold states of being and through an anthropology that is not restricted to the simple soul-body dichotomy, but is aware of 'subtle' and even transcendental modalities of human consciousness. Although foreign to contemporary thought, knowledge of this kind formed an integral part of ancient learning and of the traditions of varied peoples."[18]

"[...] this type can only feel disinterested and detached from everything that is 'politics' today. His principle will become apoliteia, as it was called in ancient times. [...] Apoliteia is the distance unassailable by this society and its 'values'; it does not accept being bound by anything spiritual or moral."[20]

00:05 Publié dans Philosophie, Révolution conservatrice, Traditions | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : tradition, traditionalisme, julius evola, italie |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

Tradición y Sabiduría Universal

Conversación sin complejos con el "Último Gibelino":

Julius Evola

entrevista de Enrico de Boccard

Ex: http://paginatransversal.wordpress.com

La Página Transversal recoge este texto, publicado en su día por la ya desaparecida, pero siempre recomendable revista de Fernando Márquez, El Zurdo, "El Corazón del Bosque", en su número doble 16/17 (Otoño 97 - Invierno 98), por su indudable interés. Cuestiones tales como: sexo, psicoanálisis, satanismo, contestación y otras, tratadas desde la particular cosmovisión de Julius Evola (1898-1974).

La presente entrevista, rescatada por nuestro colaborador Gianni Donaudi (que también nos ha facilitado unos datos de introducción), se publicó en la revista erótico/intelectual "PLAYMEN" en enero del 70. "PLAYMEN" era propiedad de la edirtora Adelina Tattilo, políticamente cercana al PSI/PSU, quien, apoyándose en el radicalizante Attilio Battistini como director de la publicación, buscó (al menos en el plano cultural) dar amplio espacio a autores de muy diferente tendencia política e ideológica.

Eran los años de la contestación y, tras el espontaneísmo inicial del 68, donde los enemigos principales eran el capitalismo, el consumismo (según la definición de Marcuse y Fromm) y el dominio americano sobre el planeta, se llegó, a través de infiltrados demoliberales (a veces situados por los mismos americanos) a reducir la lucha contestataria en términos exclusivamente "antifascistas", colocando el anticapitalismo en un segundo plano (como lúcidamente analizaban las publicaciones de signo internacionalista y bordiguista). Una estrategia que dura hasta hoy, sobre todo gracias a la obra de la izquierda chic, virtual, políticamente correcta.

A pesar de esto, Adelina Tattilo, en coherencia con su radicalismo extremo, no sólo aceptó la entrevista con Evola sino que se enorgullecía de la misma, por protagonirala alguien que sabía escribir, sin importar su procedencia.

El periodista que entrevistó a Evola fue Enrico de Boccard (1921-1981)quien, también para "PLAYMEN", había escrito una hermosa semblanza sobre Céline. Boccard era un ex-oficial de la Guardia Nacional Republicana (de Saló) y fue autor del libro, en parte autobiográfico, Donne e mitra (reeditado recientemente con el título Le donne non ci vogliono piu bene. Por cierto,Boccard no fue el único vinculado a la República Social Italiana que colaboró con "PLAYMEN". También lo hicieron Giose Rimanelli, autor de Tiro al piccione (obra adaptada al cine en el 61 por el director filosocialista Giuliano Montaldo -autor, entre otros films, de Sacco e Vanzetti y Giordano Bruno-), que en la postguerra se acercaría a los comunistas y más tarde involucionaría a la derecha; y Mario Gandini, autor de La caduta di Varsavia (obra sobre sus recuerdos de guerra en el Este y la RSI).

Por razones de espacio, hemos seleccionado los fragmentos que consideramos más interesantes y válidos según la perspectiva corazonesca, y como toque metalingüístico quasi felliniano (habida cuenta de buena parte de la temática de la entrevista), resulta procedente señalar la publicidad que la acompañaba: un vibrador ("novitá della Svezia" en dos modelos -con una y dos velocidades-), un catálogo ilustrado de productos estimulantes (escribir a la empresa sueca "Ekberg Int.") y unos potingues vigorizantes (incluido el, por entonces, mítico Gerovital de la doctora rumana Aslan, así como polen -también "della Svezia"- ideal para... los males de próstata-).

En el último piso de un viejo edificio del centro de Roma vive su intensa jornada uno de los últimos hombres verdaderamente libres en un tiempo en que la libertad se ha convertido en un lujo que se paga cada día, personal y colectivamente, siempre más caro. Este hombre, que ha sobrepasado no hace mucho los setenta años de una existencia riquísima en experiencias intelectuales, artísticas y personales, marcado contsantemente por el signo del más declarado y valeroso anticonformismo, tiene un nombre de resonancia mundial, pese a que la llamada "cultura oficial" italiana, tanto en el Ventennio fascista como después, siempre ha procurado por todos los medios de sofocarlo con una impenetrable cortina de silencio. Este hombre es el filósofo y escritor Julius Evola, autor de unos treinta libros nada superfluos, "revolucionario conservador" por temperamento y por trayectoria. Julius Evola: un aristócrata del espíritu más que de la sangre, que gusta definirse a sí mismo como "el Último Gibelino".

Pregunta - Es bien conocido que usted concede raramente entrevistas y le agradecemos, en nombre de nuestros lectores, por el privilegio gentilmente concedido. Por otra parte, usted es un escritor, un estudioso dotado de tal doctrina y preparación, y con tal bagaje de experiencias que nos encontramos un poco embarazados en el momento de plantearle preguntas, las cuales son tantas en nuestra mente como vasto es el campo de sus intereses (metafísica, crítica de la política, historia de las religiones, orentalismo, etc.). Trataremos de restringirnos a los argumentos que consideramos puedan interesar más a los lectores de la revista o que presenten un carácter de actualidad. Empecemos con una obra, recientemente reeditada (y también con dos ediciones francesas y otra alemana), sistemática y sugestiva, Metafísica del sexo (hay edición en castellano). Usted precisa, a propósito del título, haber usado el término "metafísica" en un doble sentido. ¿Puede aclararnos esto? Respuesta - El primer sentido es el corriente en filosofía, donde por metafísica se entiende una búsqueda de los principios o significados últimos. Una metafísica del sexo será, por tanto, el estudio de lo que, desde un punto de vista absoluto, significa el eros y la atracción de los sexos. En segundo lugar, por metafísica se puede entender una exploración en el campo de lo que no es físico, de lo que está más allá de lo físico. Es unpunto esencial de mi búsqueda el sacar a la luz lo que el eros y la experiencia del sexo supone de trascendencia de los aspectos físicos, carnales, biológicos y también pasionales o convencionalmente sentimentales o "ideales" del amor. Esta dimensión más profunda fue considerada en otro tiempo, en múltiples tradiciones, y constituye el presupuesto para un posible uso "sacro", místico, mágico y evocatorio del sexo; pero ello también influye en muchos actos del amor profano, revelándose a través de una variedad de signos que yo he tratado de individuar sistemáticamente. En mi libro señalo también cómo hoy, en una inversió quasidemoníaca, cierto psicoanálisis resalta una primordialidad infrapersonal del sexo, y opongo a esta primordialidad otra, de carácter "metafísico" o trascendente, pero no por esto menos real y elemental, de la que la anterior sería la degradación propia de un tipo humano inferior.

P - Usted también ha afrontado el problema del sexo sobre el terreno de la costumbre y de la ética, y siempre de manera anticonformista. ¿Qué piensa, por tanto, de lo que hoy se denomina "revolución sexual"?

R - A mí, qué cosa significa esta "revolución" no lo veo nada claro. Parece que se busca la absoluta libertad sexual, la completa superación de toda represión social sexófoba y de toda inhibición interna. Pero aquí hay un gravísimo malentendido, debido a las instancias llamadas "democráticas". Una libertad semejante no puede reivindicarse para todos: solamente pocos se la pueden permitir, no por privilegio sino porque, para no ser destructiva, hace falta una personalidad bien formada. En particular, el problema debe ser situado en modo distinto para el hombre y para la mujer, insisto, no por prejuicio sino por el distinto significado que la experiencia erótica, la auténtica e intensa, tiene para la mujer. Justamente Nietzsche había indicado que la "corrupción" (aquí, la "libertad sexual") puede ser un argumento sólo para quien no puede permitírsela, por ejemplo, para quienes no pueden hacer suyo el principio de querer sólo las cosas a las cuales también son capaces de renunciar.

La "revolución sexual" en clave democrática comporta, pues, una consecuencia gravísima, hacer del sexo una especie de género corriente, de consumo de masas, lo que significa necesariamente banalizarlo, superficializarlo, acabando en un insípido "naturalismo". En otro libro mío, "L´Arco e la Clava" ("El Arco y la Clava", existe traducción al castellano), he mostrado cómo las nuevas reivindicaciones sexuales son paralelas a una concepción siempre más primitiva de la sensualidad por parte de sus principales teóricos, a partir de Reich. Un caso particular es la falta de pudor femenina, vinculada con similares propuestas antirepresivas. A fuerza de ver mujeres desnudas o casi en espectáculos teatrales y cinematográficos, en locales porno, en top-less, etc, este desnudo acaba por convertirse en una banalidad que poco a poco dejará de producir efecto, al margen de los directamente dictados por el primitivo impulso biológico. Este impudor debería ser despreciado no desde el punto de vista de la "virtud" sino del exactamente opuesto. Por ese camino se puede llegar a un resultado de "naturalidad" e indiferencia sexual mucho mayor al soñado por cualquier sociedad puritana. (...)

P - De su exposición, parece que su juicio sobre el psicoanálisis sea negativo (...)

R - Evidentemente que no puedo profundizar exhaustivamente en esta argumentación. Pero sí señalaré que ante todo ha de relativizarse la idea de que el psicoanálisis descubre por vez primera la dimensión subterránea del Yo, el subconsciente y el inconsciente psíquico. Ya antes de Freud la psicología occidental, conectada con la fenomenología de la hipnosis y del histerismo, había prestado atención sobre este "subsuelo" del alma. Bastante más profundamente, y en muy diversa amplitud, ello estaba considerado en Oriente desde siglos, gracias al Yoga y técnicas análogas. El psicoanálisis puede ser una psicoterapia, y ofrecer resultados singulares en un plano clínico especializado. Pero no más: en su esncia es una concepción absolutamente desviada y mutilada del ser humano. Al colocar la verdadera fuerza motriz del hombre sobre el plano del inconsciente infrapersonal e instintivo, Freud concretamente bajo el signo de la libido, niega la existencia de un superior principio consciente, autónomo y soberano, porque en su lugar pone cualquier cosa del exterior, el llamado SuperYo, que sería una construcción social y el producto de la asunción de formas inhibitorias creadas por el ambiente o las estructuras sociales. Ello equivale a decir que el psicoanálisis niega en el hombre lo que lo hace verdaderamente tal, y su imagen, la cual querría aplicar al hombre de manera genérica, o es una mixtificación o vale únicamente para un tipo humano dividido, neurótico, espiritualmente inconsistente. Es bien posible que el éxito del psicoanálisis sea debido a la gran difusión que en la época moderna ha tenido este tipo. Como praxis y como tendencia, el psicoanálisis propicia esencialmente aperturas hacia abajo y significa una capitulación más o menos explícita de todo lo que es verdadera personalidad. La posible existencia de un "superconsciente", opuesto al "inconsciente", luminoso frente a lo turbio y "elemental" es ignorada por completo. (...)

P - Ha mencionado antes a Wilhelm Reich. Queremos conocer su opinión sobre su persona y su obra. ¿Reich le parece un estudioso serio o un exaltado? ¿Y qué piensa de las aplicaciones de los principios de él y de sus seguidores en el plano sociológico y político/sociológico, de sus denuncias de los sistemas "autoritarios"?

R - Reich me parece afectado por una variedad de paranoia. Su mérito es haber intuido que en el sexo existe algo trascendente, más allá de lo individual. Ello concuerda con las enseñanzas de múltiples tradiciones. pero esta intuición está muy desviada. No debe decirse que el sexo es algo trascendente, sino que en ello se manifiesta (potencialmente y en ciertas circunstancias, incluso hoy día) algo trascendente, que como tal no pertenece al plano físico. Este elemento Reich lo concibe en términos materialistas como una energía natural, como la electricidad o algo así, al punto que, como "energía orgónica", ha buscado dotarla (gastando verdaderos capitales) de sustancia física, construyendo finalmente "condensadores" de la misma. Todo esto no son sino divagaciones. A lo que hemos de añadir una "teoría de la salvación", en cuanto que Reich ve en la obstrucción de dicha energía la cuas de todos los males, individuales y sociales (hasta el mismo cáncer) y, en su completa y desenfrenada explicación, el orgasmo sexual integral como una especie de medicina universal, presupuesto para un orden social sin tensiones, armonioso, pacífico.

R - Reich me parece afectado por una variedad de paranoia. Su mérito es haber intuido que en el sexo existe algo trascendente, más allá de lo individual. Ello concuerda con las enseñanzas de múltiples tradiciones. pero esta intuición está muy desviada. No debe decirse que el sexo es algo trascendente, sino que en ello se manifiesta (potencialmente y en ciertas circunstancias, incluso hoy día) algo trascendente, que como tal no pertenece al plano físico. Este elemento Reich lo concibe en términos materialistas como una energía natural, como la electricidad o algo así, al punto que, como "energía orgónica", ha buscado dotarla (gastando verdaderos capitales) de sustancia física, construyendo finalmente "condensadores" de la misma. Todo esto no son sino divagaciones. A lo que hemos de añadir una "teoría de la salvación", en cuanto que Reich ve en la obstrucción de dicha energía la cuas de todos los males, individuales y sociales (hasta el mismo cáncer) y, en su completa y desenfrenada explicación, el orgasmo sexual integral como una especie de medicina universal, presupuesto para un orden social sin tensiones, armonioso, pacífico.

Es interesante detenernos un momento sobre el presupuesto de esta concepción, porque así podremos comprender las aplicaciones político/sociales de los reichianos. Freud en su madurez había admitido la existencia, junto al impulso de placer, la libido, de un opuesto, el instinto de destrucción (o "de muerte"). Reich niega esta dualidad y deduce el segundo instinto, el destructivo, del impulso único de placer. Cuando este instinto resulta impedido o "bloqueado", nacería una tensión, una angustia y sobre todo una especie de "rabia", de furia destructiva (en caso de no tomar la vía del "principio del nirvana": una evasión, una fuga de la vida). Este impulso destructivo (y agresivo) cuando se vuelve contra sí, da al hombre la orientación masoquista, y cuando se dirige a los otros, al orientación sádica.

De todo ello resulta en primer lugar que sadismo y masoquismo serían fenómenos patológicos, causados por la represión sexual. Lo que es una estupidez: existen ciertamente formas de sadismo y masoquismo vinculadas a la psicopatología sexual (según el concepto normal, no ya psicoanalítico), pero también existe un sadismo (masculino) y un masoquismo (femenino) como elementos constitucionales intrínsecos y en un cierto modo normales en toda experiencia erótica intensa. De hecho, esta experiencia tiene siempre algo de destructivo y autodestructivo (por las relaciones, múltiplemente demostradas, entre voluntad y muerte, entre la divinidad del amor y la divinidad de la muerte); y es en este aspecto que se piensa cuando, en ciertas escuelas, se cree que el clímax adecuadamente conducido puede tener, en su momento "fulgurante", algo que destruye por un momento los límites de la conciencia mortal individual. Pues bien, con la concepción de Reich, toda esta intensidad desaparece, y la consecuencia es una concepción pálida, blandamente dionisíaca, o idílica (como en Marcuse) de la sexualidad: es una de las paradojas de la llamada "revolución sexual".

No menos absurda es, en particular, la deducción de la agresividad por la inhibición del impulso primordial del sexo a cristalizar en un orgasmo completo, según la cual, cuando la obstrucción remite (en el individuo o en una sociedad "permisiva" y no "represiva" o "patriarcal") no habrá más agresividad, guerra, violencia, etc; lo que viene al mismo tiempo a decir que todo lo que hace referencia a actitudes guerreras, de conquista (en la jerga moderna, de "agresión") tendrñia la represión sexual por causa y origen. Ante esto, sólo puedo reír. La actitud agresiva es en primer lugar comprobada en los animales, evidentemente no sometidos a tabúes sexófobos y "patriarcales". En segundo lugar ya el mito ha indicado el perfecto acuerdo entre Marte y Venus, y la historia nos muestra como todos los más grandes conquistadores carecían de complejos de frustración sexual y hacían un libre y amplío uso del sexo. En la práctica, la consecuencia de la teoría de Reich es un ataque contra elementos fundamentales congénitos en todo tipo "viril" de humanidad o ser humano, que son presentados grotescamente en clave de patología sexual.

En cuanto a las conclusiones político/sociales. Proyectada sobre ese plano, la tendencia masoquista daría lugar al tipo del gregario, de aquel que gusta de servir y obedecer, que se pone al servicio de un jefe, con o sin "culto a la personalidad", y está siempre dispuesto a sacrificarse. La tendencia sádica daría lugar al tipo del dominador, de quien ejercita una autoridad, autoridad evidentemente concebida en los exclusivos términos parasexuales de una libido. De la unión de estas dos tendencias nacerían las estructuras "autoritarias" y "fascistas". Una vez más, se deforman grotescamente los datos reales de la conciencia. Del obedecer y del mandar pueden darse desviaciones. Pero, en general, se trata de disposiciones normales: existe una autoridad que tiene por contrapartida una superioridad, como existe una obediencia debida no a un servilismo masoquista sino al orgullo de seguir libremente a gentes a quienes se reconoce una superioridad. Así, mientras por un parte Reich proclama una mística mesiánica del abandono integral al orgasmo, al mismo tiempo ello actúa como preciosas coartadas para un puro anarquismo.

P - En relación con el asesinato de la actriz Sharon Tate y otros se ha hablado de "satanismo" y en los periódicos hoy se insiste en buscar conexiones entre sexo, magia y satanismo. ¿Nos puede aclarar esto?

R - En principio, existen conexiones posibles entre magia y sexo. Considerando la dimensión "trascendente" del sexo, a la que ya me he referido, se recoge en diversas tradiciones que por medio de la unión sexual conducida de determinado modo y con una orientación particular es posible destilar energías y usarlas mágicamente. La continuidad de estas tradiciones hasta un tiempo relativamente reciente es testimoniada, entre otros, en un libro, Magia sexualis de P. B. Randolph. Un ejemplo ulterior lo constituyen las prácticas mágico/sexuales y orgiásticas de Aleister Crowley, figura interesante que, por desgracia, se suele presentar con los colores más "negros" posibles. Pero en este campo se debe distinguir entre las mixtificaciones y lo que tiene un valor auténtico y una realidad. Ante todo ha de verse, por ejemplo, si se hace el amor para hacer magia o si se hace magia (o pseudomagia) para hacer el amor, o sea, si se usa la magia como un pretexto para montar orgías o para darle al acto un aire más excitante. Es cierto también que existe una tercera posibilidad, la de usar medios siríamos "secretos" con el concurso de fuerzas suprasensibles para dar un particular desarrollo paroxístico a la experiencia del coito, sin forzar por ello la naturaleza: esta vía es algo extremadamente peligroso, por razones que no viene al caso indicar ahora.

En cuanto al "satanismo" señalaré que donde predomina un clima "sexófobo" (como en el cristianismo) es fácil calificar de "diabólico" todo lo que suponga potenciar la experiencia sexual. Más genéricamente, es obvio que un "satán" existe sólo en las religiones donde ello es la contraparte "oscura" de un Dios con características "morales"; cuando como vértice del universo, en vez de Dios, se pone una "Potestad" como tal superior y más allá del bien y del mal, evidentemente un "Satán" a la cristiana no es concebible. Hay lugar sólo para la idea de una fuerza cósmica destructora, presente en el mundo y en la vida, en lo sensible y lo suprasensible, al lado de las fuerzas creadoras y conservadoras, como la "otra mitad" del Absoluto. Y existen tradicones sacras -la más característica es la tántrico/shivaica- que tienen por objeto asumir esa fuerza, diversamente concebida. Característica es la llamada "Vía de la Mano Izquierda", donde, por ejemplo, el uso de la mujer, de sustancias embriagadoras y eventualmente de la orgía, se asocia a una moral del "más allá del bien y del mal" que haría palidecer de envidia al "superhombre" Nietzsche. De dicha vía, que algunos timoratos occidentales han calificado como la "peor de las magias negras" he hablado en mi libro Lo Yoga della Potenza. Pero el punto importante es que en sus formas auténticas tales prácticas están concebidas en los mismos términos del Yoga, y no son elementos disociados, como los hippies americanos, quienes pueden permitírselas. Volvemos aquí, pero aumentadas, a poner las mismas reservas que he hecho acerca de la "revolución sexual" y sus reivindicaciones. En las tradiciones la base para darse a estas prácticas está constituida por una disciplina de autodominio profundo similar a la de los ascetas, tras una regular "iniciación".

P - Pasando a un campo distinto pero en parte relacionado, me llama la atención cómo en algunos libros históricos o pseudohistóricos sobre el III Reich hitleriano se habla de un fondo oculto, mágico/tenebroso, del nacionalsocialismo alemán. ¿Puede decime brevemente qué le parece este argumento?

R - Para quien busque los supuestos trasfondos "ocultos" del III Reich, el argumento me llevaría más allá de los límites en los cuales estoy manteniendo esta entrevista. Me limitaré a decir que, como persona que ha tenido oportunidad de conocer bastante de cerca la situación del III Reich, puedo declarar que se trata de puras fantasías, y así se lo dije a Louis Pauwels, quien en su libro El retorno de los brujos ha contribuido a defender tales rumores; él vino una vez a conocerme, hablamos y en ningún momento me presentó dato alguno mínimamente serio que apoyase su tesis. Se puede hablar no de "iniciático" sino de "demoniaco", en un sentido general, en el caso de todo movimiento que en base a una fanatización de las masas creer cualquier cosa cuyo centro será el jefe demagógico que produce esta especie de hipnosis colectiva usando tal o cual mito. Dicho fenómeno no está relacionado con lo "mágico" o con lo "oculto", aunque tenga un fondo tenebroso. Es un fenómeno recurrente en la Historia, por ejemplo, la Revolución Francesa o (en parte) el maoísmo.

P - Usted es autor de una obra considerada como fundamental por cuantos siguen atentamente su actividad, Revuelta contra el mundo moderno. Se afirma por muchos que usted, con este libro (publicado por vez primera en 1934), anticipó en varios lustros las visiones, hoy tan en boga, expresadas por Marcuse. En otras palabras, desde posiciones absolutamente distintas a la del profesor germano/americano, usted habría sido el primero en tomar postura contra "el sistema". ¿Le parece válida esta comparación con Marcuse? Y, de otra parte, ¿dado el papel que Marcuse tiene en las actuales formas de "contestación" juvenil contra el mundo moderno, qué significado y qué imagen tiene para usted este movimiento contestatario?

R - En verdad, como precedentes de Marcuse, y planteando cosas bastante más interesantes, muchos otros autores deberían ser nombrados: un Tocqueville, un John Stuart Mill, un A. Siegfried, el mismo Donoso Cortés, en parte Ortega y Gasset, sobre todo Nietzsche, y aún más el insigne escritor tradicionalista francés René Guenón, especialmente en su Crisis del mundo moderno que yo traduje al italiano en su momento. A finales del siglo pasado Nietzsche había previsto uno de los rasgos destacados de las tesis de Marcuse, con las breves, incisivas frases dedicadas al "último hombre": "próximo está el tiempo del más despreciable de los hombres, que no sabe más que despreciarse a sí mismo", "el último hombre de la raza pululante y tenaz", "nosotros hemos inventado la felicidad, dicen, satisfechos, los últimos hombres", que han abandonado "la región donde la vida es dura". Y esta es la esencia de la "civilización de masas, del consumo y del bienestar" pero también la única que el mismo Marcuse ve como perspectiva en términos positivos, cuando los desarrollos ulteriores de la técnica unidos a una cultura de transposición y sublimación de los instintos habrán sustraído a los hombres de los "condicionamientos" del actual sistema y de su "principio de prestación". La relación con mi libro no es tal porque, en primer lugar, el contenido de éste no corresponde con el título: no es mi obra de naturaleza polémica, sino una "morfología de la civilización", una interpretación general de la Historia en términos no "progresistas", de evolución, sino más bien de involución, indicando sobre estas premisas el nacimiento y el declive del mundo moderno. Sólo por caminos naturales y consecuentes se propone una "revuelta" a los lectores y, más concretamente, tras un estudio comparado de las más diversas civilizaciones, he procurado indicar lo que en diversos dominios de la existencia puede reivindicar un carácter de norma en sentido ascendente: el Estado, la ley, la acción, la concepción de la vida y de la muerte, lo sagrado, las relaciones sociales, la ética, el sexo, la guerra, etc. Esta es la primera diferencia fundamental respecto a las diversas contestaciones de hoy: no se limita a decir "no", sino que indica en nombre de qué debe decirse "no", aquello que puede verdaderamente justificar el "no". Y un "no" auténticamente radical, que no se restrinja a los aspectos últimos del mundo moderno, a la "sociedad de consumo", a la tecnocracia y demás, sino mucho más profundo, denunciando las causas, considerando los procesos que han ejercido desde hace tanto tiempo una acción destructiva sobre todos los valores, ideales y formas de organización superior de la existencia. Todo esto ni Marcuse ni los "contestatarios" en general lo han hecho: no tienen la capacidad ni el coraje. En particular, la sociología de Marcuse es absolutamente rechazable, determinada por un grosero freudismo con tonalidades reichianas. Así, no resulta extraño que sean tan escuálidos e insípidos los ideales que se proponen para la sociedad que siga a la "contestación" y a la superación del llamado "sistema".

Naturalmente, quien comprenda el orden de ideas expuesto en mi libro no puede permitirse el menor optimismo. Por ahora encuentro solamente posible una acción de defensa individual interior. Es así que en otro libro mío, Cabalgar el tigre, he procurado señalar las orientaciones existenciales que debería seguir un tipo humano diferenciado en una época de disolución como la actual. En él, he dado particular relieve al principo de la "conversión del veneno en medicina", según la medida en que, a partir de una cierta orientación interior, de experiencias y procesos mayormente destructivos se puede extraer cierta forma de liberación y autosuperación. Es una vía peligrosa pero posible. (...)

(entrevista: Enrico de Boccard)

(traducción: Fernando Márquez. Página "Linea de Sombra")

Nota de la Página Transversal:

Existen traducciones al castellano de todas las obras mencionadas en el texto.

Evola, Julius. Metafísica del sexo. Col. Sophia Perennis. José J. de Olañeta, Editor. Palma de Mallorca, 1997.

- El arco y la clava. Ediciones Heracles, Buenos Aires, 1999.

-El yoga tántrico. Un camino para la realización del cuerpo y el espíritu. Madrid, Edaf, 1991.

- Rebelión contra el mundo moderno. Ediciones Heracles, Buenos Aires, 1994.

- Cabalgar el tigre. Ediciones Heracles, Buenos Aires, Buenos Aires, 1999.

Guenon, René. La crisis del mundo moderno. Ed. Obelisco, Barcelona, 1987

Pauwels, Louis; Bergier, Jacques. El retorno de los brujos. Plaza & Janés, Barcelona, 1971.

00:05 Publié dans Entretiens, Traditions | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : métaphysique du sexe, traditionalisme, traditionalisme révolutionnaire, sexualité, tradition, julius evola, wilhelm reich |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

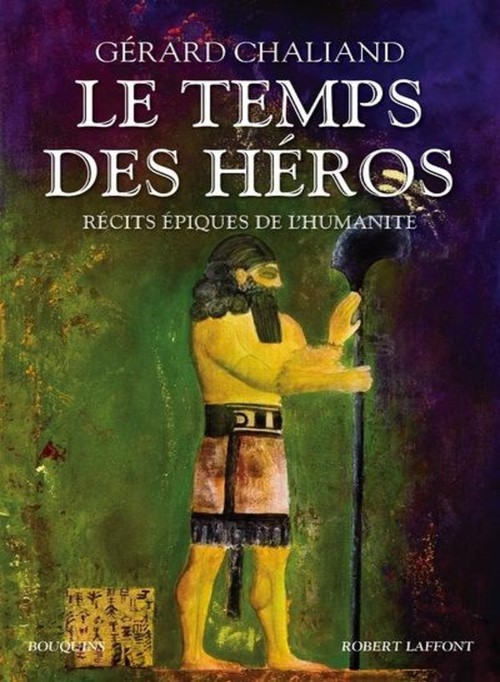

Cette anthologie, sans équivalent par son ampleur, offre un vaste aperçu des épopées, chants et récits les plus célèbres, contés ou écrits à travers les temps. De L’Épopée de Gilgamesh, la plus ancienne de l’histoire de l’humanité, aux Lusiades des avancées maritimes portugaises qui découvrirent des ” étoiles nouvelles “, elle retrace cinq mille ans de légendes et mythes fondateurs des civilisations : œuvres majeures comme Le Livre des rois (Perse) ou le Mahâbhârata (Inde), Le Dit des Heiké (Japon) et d’autres moins connues, issues de Russie, du Caucase, des Balkans, de Chine, du Vietnam, d’Orient ou d’Afrique. Le genre épique, que précèdent seulement les textes sacrés, se trouve à la source de la plupart des grandes littératures universelles. Création presque toujours anonyme, il relate, au sens propre, des faits dignes d’être contés. Conçu à des époques où la force physique et, d’une façon générale, les vertus martiales étaient à la fois hautement prisées et nécessaires, il est centré sur la figure du héros. Gratifié d’une naissance hors du commun, presque toujours doté d’une force surnaturelle ou bénéficiant de vertus magiques, le héros s’affirme à travers une série d’épreuves. Luttant contre le chaos, il restaure l’ordre et succombe de façon tragique. Tel est, si l’on s’en tient aux grandes lignes, le destin du héros épique. Il n’est pas étonnant que Gérard Chaliand, grand reporter, homme d’aventures et d’expériences fortes, se passionne de longue date pour la littérature épique. Son propre itinéraire n’a cessé de l’entraîner sur les grandes routes du monde, où il a croisé quelques-unes de ces figures héroïques dont ses lectures d’enfance lui avaient déjà donné un avant-goût.

Ex: http://zentropaville.tumblr.com

00:05 Publié dans Livre, Livre, Traditions | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : livre, anthologie, gérard chaliand, héros, héroïsme, traditions, traditionalisme |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

L’opposition entre la culture occidentale prônant le libre arbitre et l’obligation de se donner la mort en mission commandée a ouvert la porte à l’irrationalité et au romantisme. Leur dernière nuit était un déchirement, mais tous ont su trouver la force de sourire avant le dernier vol. Kasuga Takeo (86 ans), dans une lettre au docteur Umeazo Shôzô, apporte un témoignage exceptionnel sur les dernières heures des kamikazes : « Dans le hall où se tenait leur soirée d’adieu la nuit précédant leur départ, les jeunes étudiants officiers buvaient du saké froid. Certains avalaient le saké en une gorgée, d’autres en engloutissaient une grande quantité. Ce fut vite le chaos. Il y en avait qui cassaient des ampoules suspendues avec leurs sabres. D’autres qui soulevaient les chaises pour casser les fenêtres et déchiraient les nappes blanches. Un mélange de chansons militaires et de jurons emplissaient l’air. Pendant que certains hurlaient de rage, d’autres pleuraient bruyamment. C’était leur dernière nuit de vie. Ils pensaient à leurs parents et à la femme qu’ils aimaient….Bien qu’ils fussent censés être prêts à sacrifier leur précieuse jeunesse pour l’empire japonais et l’empereur le lendemain matin, ils étaient tiraillés au-delà de toute expression possible…Tous ont décollé au petit matin avec le bandeau du soleil levant autour de la tête. Mais cette scène de profond désespoir a rarement été rapportée. »

Emiko Ohnuki-Tierney, Kamikazes, Fleurs de cerisier et Nationalismes, éditions Hermann, 2013, 580 p., 38 euros.

Ex: http://zentropaville.tumblr.com

00:05 Publié dans Livre, Livre, Traditions | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : livre, kamikazes, japon, traditions, traditionalisme, asie, affaires asiatiques |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

par Charles Mallet

Ex: http://lheurasie.hautetfort.com

A ce titre, ce concept est à l’image de la culture politique et de la pratique du pouvoir des Empereurs Romains : souple, pragmatique, concrète. Il en va de même de la nature du pouvoir impérial, difficile à appréhender et à définir, puisque construit par empirisme (sa nature monarchique n’est cependant pas contestable). En plus de quatre siècles, le pouvoir impérial a su s’adapter aux situations les plus périlleuses (telle la « crise » du IIIe siècle). Rien de commun en effet entre le principat augustéen, système dans lequel l’empereur est le princeps, le prince, primus inter pares, c’est-à-dire premier entre ses pairs de l’aristocratie sénatoriale ; la tétrarchie de Dioclétien (284-305), partage du pouvoir entre quatre empereurs hiérarchisés et l’empire chrétien de Constantin (306-337), dans lesquels l’empereur est le dominus, le maître.

A ce titre, ce concept est à l’image de la culture politique et de la pratique du pouvoir des Empereurs Romains : souple, pragmatique, concrète. Il en va de même de la nature du pouvoir impérial, difficile à appréhender et à définir, puisque construit par empirisme (sa nature monarchique n’est cependant pas contestable). En plus de quatre siècles, le pouvoir impérial a su s’adapter aux situations les plus périlleuses (telle la « crise » du IIIe siècle). Rien de commun en effet entre le principat augustéen, système dans lequel l’empereur est le princeps, le prince, primus inter pares, c’est-à-dire premier entre ses pairs de l’aristocratie sénatoriale ; la tétrarchie de Dioclétien (284-305), partage du pouvoir entre quatre empereurs hiérarchisés et l’empire chrétien de Constantin (306-337), dans lesquels l’empereur est le dominus, le maître. Ainsi, à l’éclatement politique de l’Europe au Moyen Âge et à l’époque Moderne a correspondu un éclatement du pouvoir souverain, de l’imperium. L’idée d’un pouvoir souverain fédérateur n’en n’a pas pour autant été altérée. Il en va de même de l’idée d’une Europe unie, portée par l’Eglise, porteuse première de l’héritage romain. Le regain d’intérêt que connait la notion d’imperium n’est donc pas le fruit d’une passion romantique pour l’antiquité européenne, mais la preuve qu’en rupture avec la conception moderne positiviste de l’histoire, nous regardons les formes d’organisations politiques passées comme autant d’héritages vivants et qu’il nous appartient de nous les réapproprier (les derniers empires héritiers indirects de la vision impériale issue de Rome ont respectivement disparu en 1917 –Empire Russe- et 1918 –Empire Austro-Hongrois et Empire Allemand-). Si ce court panorama historique ne peut prétendre rendre compte de la complexité du phénomène, de sa profondeur, et des nuances nombreuses que comporte l’histoire de l’idée d’imperium ou même de l’idée d’Empire, nous espérons avant tout avoir pu clarifier son origine et son sens afin d’en tirer pour la réflexion le meilleur usage possible. L’imperium est une forme du pouvoir politique souple et forte à la fois, capable de redonner du sens à l’idée de souveraineté, et d’articuler autorité politique continentale et impériale de l’Eurasisme avec les aspirations à la conservation des autonomies et des identités nationales portées par le Nationalisme ou même le Monarchisme. A l’heure où le démocratisme, les droits de l’homme, et le libéralisme entrent dans leur phase de déclin, il nous revient d’opposer une alternative cohérente et fédératrice et à opposer l’imperium au mondialisme.

Ainsi, à l’éclatement politique de l’Europe au Moyen Âge et à l’époque Moderne a correspondu un éclatement du pouvoir souverain, de l’imperium. L’idée d’un pouvoir souverain fédérateur n’en n’a pas pour autant été altérée. Il en va de même de l’idée d’une Europe unie, portée par l’Eglise, porteuse première de l’héritage romain. Le regain d’intérêt que connait la notion d’imperium n’est donc pas le fruit d’une passion romantique pour l’antiquité européenne, mais la preuve qu’en rupture avec la conception moderne positiviste de l’histoire, nous regardons les formes d’organisations politiques passées comme autant d’héritages vivants et qu’il nous appartient de nous les réapproprier (les derniers empires héritiers indirects de la vision impériale issue de Rome ont respectivement disparu en 1917 –Empire Russe- et 1918 –Empire Austro-Hongrois et Empire Allemand-). Si ce court panorama historique ne peut prétendre rendre compte de la complexité du phénomène, de sa profondeur, et des nuances nombreuses que comporte l’histoire de l’idée d’imperium ou même de l’idée d’Empire, nous espérons avant tout avoir pu clarifier son origine et son sens afin d’en tirer pour la réflexion le meilleur usage possible. L’imperium est une forme du pouvoir politique souple et forte à la fois, capable de redonner du sens à l’idée de souveraineté, et d’articuler autorité politique continentale et impériale de l’Eurasisme avec les aspirations à la conservation des autonomies et des identités nationales portées par le Nationalisme ou même le Monarchisme. A l’heure où le démocratisme, les droits de l’homme, et le libéralisme entrent dans leur phase de déclin, il nous revient d’opposer une alternative cohérente et fédératrice et à opposer l’imperium au mondialisme.

00:05 Publié dans Définitions, Théorie politique, Traditions | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : imperium, tradition, traditionalisme, empire, notion d'empire, reich, histoire, rome, rome antique, empire romain, définition, théorie politique, politologie, sciences politiques, philosophie politique |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

00:02 Publié dans Evénement, Traditions | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : tradition, traditionalisme, julius evola, métaphysique, métaphysique du sexe, sexualité, italie, événement, idéalisme magique, philosophie |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

00:05 Publié dans Entretiens, Traditions | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : tradition, renato del ponte, julius evola, traditionalisme, italie |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

Leader of Hungarian political party "Jobbik" about Eurasian ideas

"Actually, the truth is that the West really is in great need of »defense«, but only against itself and its own tendencies, which, if they are pushed to their conclusion, will lead inevitably to its ruin and destruction; it is therefore »reform« of the West that is called for instead of »defense against the East«, and if this reform were what it should be---that is to say, a restoration of tradition---it would entail as a natural consequence an understanding with the East."

– René Guénon[1]

1. Euroatlantism and anti-traditionalism

Today's globalized world is in crisis. That is a fact. However, it is not quite clear what this crisis is. In order to get an answer, first we need to define what globalization means. For us, it does not mean the kind of public misconception, which says that the borders between the world's various economic and cultural spheres will gradually disappear and the planet becomes an organic network built upon billions of interactions. Those who believe in this also add that history is thus no longer a parallel development of great spheres, but the great common development of the entire world. Needless to say, this interpretation considers globalization as a positive and organic process from the aspect of historical development.

From our aspect, however, globalization is an explicitly negative, anti-traditionalist process. Perhaps we can understand this statement better if we break it down into components. Who is the actor, and what is the action and the object of globalization? The actor of globalization - and thus crisis production - is the Euro-Atlantic region, by which we mean the United States and the great economic-political powers of Western Europe. Economically speaking, the action of globalization is the colonization of the entire world; ideologically speaking, it means safeguarding the monopolistic, dictatorial power of liberalism; while politically speaking, it is the violent export of democracy. Finally, the object of globalization is the entire globe. To sum it up in one sentence: globalization is the effort of the Euro-Atlantic region to control the whole world physically and intellectually. As processes are fundamentally defined by their actors that actually cause them, we will hereinafter name globalization as Euroatlantism. The reason for that is to clearly indicate that we are not talking about a kind of global dialogue and organic cooperation developing among the world's different regions, continents, religions, cultures, and traditions, as the neutrally positive expression of "globalization" attempts to imply, but about a minor part of the world (in particular the Euro-Atlantic region) which is striving to impose its own economic, political, and intellectual model upon the rest of the world in an inorganic manner, by direct and indirect force, and with a clear intention to dominate it.

As we indicated at the beginning of this essay, this effort of Euroatlantism has brought a crisis upon the entire world. Now we can define the crisis itself. Unlike what is suggested by the news and the majority of public opinion, this crisis is not primarily an economic one. The problem is not that we cannot justly distribute the assets produced. Although it is true, it is not the cause of the problem and the crisis; it is rather the consequence of it. Neither is this crisis a political one, that is to say: the root cause is not that the great powers and international institutions fail to establish a liveable and harmonious status quo for the whole world; it is just a consequence as well. Nor does this crisis result from the clashes of cultures and religions, as some strategists believe; the problem lies deeper than that. The world's current crisis is an intellectual one. It is a crisis of the human intellect, and it can be characterized as a conflict between traditional values (meaning conventional, normal, human) and anti-traditionalism (meaning modern, abnormal, subhuman), which is now increasingly dominating the world. From this aspect, Euroatlantism - that is to say, globalism - can be greatly identified with anti-traditionalism. So the situation is that the Euro-Atlantic region, which we can simply but correctly call the West, is the crisis itself; in other words, it carries the crisis within, so when it colonizes the world, it in fact spreads an intellectual virus as well. So this is the anti-traditionalist aspect of the world's ongoing processes, but does a traditionalist pole exist, and if it does, where can we find it?

2. Eurasianism as a geopolitical concept

Geographically speaking, Eurasia means the continental unity of Europe and Asia, which stretches from the Atlantic to the Pacific. As a cultural notion, Eurasianism was a concept conceived by Russian emigrants in the early 20th century. It proved to be a fertile framework, since it has been reinterpreted several times and will surely continue to be so in the future as well. Nicolai Sergeyevich Trubetskoy is widely considered as the founder of Eurasianism, while Alexandr Dugin is referred to as the key ideologist of the concept. Trubetskoy was one of the greatest thinkers of the Russian emigration in the early 20th century, who attempted to redefine Russia's role in the turbulent post-World War I times, looking for new goals, new perspectives, and new meanings. On the one hand, he rejected Pan-Slavism and replaced the Slavophile ideology with a kind of "Turanophile" one, as Lajos Pálfalvi put it in an essay.[2] He tore Russian thinking out of the Eastern Slavic framework and found Genghis Khan as a powerful antetype, the founder of a Eurasian state. Trubetskoy says that it was the Khan's framework left behind that Moscow's Tsars filled with a new, Orthodox sense of mission after the Mongol occupation. In his view, the European and Western orientation of Peter the Great is a negative disruption of this process, a cultural disaster, while the desirable goal for Russia is to awaken as a part of Eurasia.

So Eurasianism was born as a uniquely Russian concept but not at all for Russia only, even though it is often criticized for being a kind of Great Russia concept in a cultural-geopolitical disguise. Ukrainian author Mikola Ryabchuk goes as far as to say that whoever uses this notion, for whatever reason, is basically doing nothing but revitalizing the Russian political dominance, tearing the former Soviet sphere out of the "European political and cultural project".[3] Ryabchuk adds that there is a certain intellectual civil war going on in the region, particularly in Russia and also in Turkey about the acceptance of Western values. So those who utter the word "Eurasianism" in this situation are indirectly siding with Russia. The author is clearly presenting his views from a pro-West and anti-Russian aspect, but his thoughts are worth looking at from our angle as well.

As a cultural idea, Eurasianism was indeed created to oppose the Western, or to put it in our terms, the Euro-Atlantic values. It indeed supposes an opposition to such values and finds a certain kind of geopolitical reference for it. We must also emphasize that being wary of the "European political and cultural project" is justified from the economic, political, and cultural aspects as well. If a national community does not wish to comply, let's say, with the role assigned by the European Union, it is not a negative thing at all; in fact, it is the sign of a sort of caution and immunity in this particular case. It is especially so, if it is not done for some economic or nationalistic reason, but as a result of a different cultural-intellectual approach. Rendering Euro-Atlantic "values" absolute and indisputable means an utter intellectual damage, especially in the light of the first point of our essay. So the opposition of Eurasianism to the Euro-Atlantic world is undeniably positive for us. However, if we interpreted Eurasianism as mere anti-Euro-Atlantism, we would vulgarly simplify it, and we would completely fail to present an alternative to the the anti-traditionalist globalization outlined above.

What we need is much more than just a reciprocal pole or an alternative framework for globalization. Not only do we want to oppose globalization horizontally but, first and foremost, also vertically. We want to demonstrate an intellectual superiority to it. That is to say, when establishing our own Eurasia concept, we must point out that it means much more for us than a simple geographical notion or a geopolitical idea that intends to oppose Euro-Atlantism on the grounds of some tactical or strategic power game. Such speculations are valueless for me, regardless of whether they have some underlying, latent Russian effort for dominance or not. Eurasianism is basically a geographical and/or political framework, therefore, it does not have a normative meaning or intellectual centre. It is the task of its interpretation and interpreter to furnish it with such features.

3. Intellectual Eurasianism - Theories and practice

We have stated that we cannot be content with anti-Euro-Atlantism. Neither can we be content with a simple geographical and geopolitical alternative, so we demand an intellectual Eurasianism. If we fail to provide this intellectual centre, this meta-political source, then our concept remains nothing but a different political, economic, military, or administrative idea which would indeed represent a structural difference but not a qualitative breakthrough compared to Western globalization. Politically speaking, it would be a reciprocal pole, but not of a superior quality. This could lay the foundations for a new cold or world war, where two anti-traditionalist forces confront each other, like the Soviet Union and the United States did, but it surely won't be able to challenge the historical process of the spread of anti-traditionalism. However, such challenge is exactly what we consider indispensable. A struggle between one globalization and another is nonsensical from our point of view. Our problem with Euro-Atlantism is not its Euro-Atlantic but its anti-traditionalist nature. Contrary to that, our goal is not to construct another anti-traditionalist framework, but to present a supranational and traditionalist response to the international crisis. Using Julius Evola's ingenious term, we can say that Eurasianism must be able to pass the air test.[4]

At this point, we must look into the question of why we can't give a traditionalist answer within a Euro-Atlantic framework. Theoretically speaking, the question is reasonable since the Western world was also developing within a traditional framework until the dawn of the modern age, but this opportunity must be excluded for several reasons. Firstly, it is no accident that anti-traditionalist modernism developed in the West and that is where it started going global from. The framework of this essay is too small for a detailed presentation of the multi-century process of how modernism took roots in and grew out of the original traditionalist texture of Greco-Roman and Judeo-Christian thinking and culture, developing into today's liberal Euroatlantism. For now, let us state that the anti-traditionalist turn of the West had a high historical probability. This also means that the East was laid on much stronger traditionalist foundations and still is, albeit it is gradually weakening. In other words, when we are seeking out a geopolitical framework for our historic struggle, our choice for Eurasianism is not in the least arbitrary. The reality is that the establishment of a truly supranational traditionalist framework can only come from the East. This is where we can still have a chance to involve the leading political-cultural spheres. The more we go West, the weaker the centripetal power of Eurasianism is, so it can only expect to have small groups of supporters but no major backing from the society.

The other important question is why we consider traditionalism as the only intellectual centre that can fecundate Eurasianism. The question "Why Eurasia?" can be answered much more accurately than "Why the metaphysical Tradition?". We admit that our answer is rather intuitive, but we can be reassured by the fact that René Guénon, Julius Evola, or Frithjof Schuon, the key figures in the restoration of traditionalist philosophy, were the ones who had the deepest and clearest understanding of the transcendental, metaphysical unity of Eastern and Western religions and cultures. Their teaching reaches back to such ancient intellectual sources that can provide a sense of communion for awakening Western Christian, Orthodox, Muslim, Hindu, or Buddhist people. These two things are exactly what are necessary for the success of Eurasianism: a foundation that can ensure supranational and supra-religious perspectives as well as an intellectual centrality. The metaphysical Tradition can ensure these two: universality and quality. At that moment, Eurasianism is no longer a mere geopolitical alternative, a new yet equally crisis-infected (and thus also infectious) globalization process, but a traditionalist response.

We cannot overemphasize the superior quality of intellectual Eurasianism. However, it is important to note here that the acquisition of an intellectual superiority ensured by the traditionalist approach would not at all mean that our confrontation with Euroatlantism would remain at a spiritual-intellectual level only, thus giving up our intentions to create a counterbalance or even dominance in the practical areas, such as the political, diplomatic, economic, military, and cultural spheres. We can be satisfied with neither a vulgar Eurasianism (lacking a philosophical centre) nor a theoretical one (lacking practicability). The only adequate form for us is such a Eurasianism that is rooted in the intellectual centre of traditionalism and is elaborated for practical implementation as well. To sum up in one sentence: there must be a traditionalist Eurasianism standing in opposition to an anti-traditionalist Euroatlantism.

The above also means that geopolitical and geographical positions are strategically important, but not at all exclusive, factors in identifying the enemy-ally coordinates. A group that has a traditionalist intellectual base (thus being intellectually Eurasian) is our ally even if it is located in a Euro-Atlantic zone, while a geographically Eurasian but anti-traditionalist force (thus being intellectually Euro-Atlantic) would be an enemy, even if it is a great power.

4. Homogeneousness and heterogeneousness

If it is truly built upon the intellectual centre of metaphysical Tradition, intellectual Eurasianism has such a common base that it is relevant regardless of geographical position, thus giving the necessary homogeneousness to the entire concept. On the other hand, the tremendous size and the versatility of cultures and ancient traditions of the Eurasian area do not allow for a complete theoretical uniformity. However, this is just a barrier to overcome, an intellectual challenge that we must all meet, but it is not a preventive factor. Each region, nation, and country must find their own form that can organically and harmoniously fit into its own traditions and the traditionalist philosophical approach of intellectual Eurasianism as well. Simply put, we can say that each one must form their own Eurasianism within the large unit.

As we said above, this is an intellectual challenge that requires an able intellectual elite in each region and country who understand and take this challenge and are in a constructive relationship with the other, similar elites. These elites together could provide the international intellectual force that is destined to elaborate the Eurasian framework itself. The sentences above throw a light on the greatest hiatus (and greatest challenge) lying in the establishment of intellectual Eurasianism. This challenge is to develop and empower traditionalist intellectual elites operating in different geographical areas, as well as to establish and improve their supranational relations. Geographically and nationally speaking, intellectual Eurasianism is heterogeneous, while it is homogeneous in the continental and essential sense.

However, the heterogeneousness of Eurasianism must not be mistaken for the multiculturalism of Euroatlantism. In the former, allies form a supranational and supra-cultural unit while also preserving their own traditions, whereas the latter aims to create a sub-cultural and sub-national unit, forgetting and rejecting traditions. This also means that intellectual Eurasianism is against and rejects all mass migrations, learning from the West's current disaster caused by such events. We believe that geographical position and environment is closely related to the existence and unique features of the particular religious, social, and cultural tradition, and any sudden, inorganic, and violent social movement ignoring such factors will inevitably result in a state of dysfunction and conflicts. Intellectual Eurasianism promotes self-realization and the achievement of intellectual missions for all nations and cultures in their own place.

5. Closing thoughts

The aim of this short essay is to outline the basis and lay the foundations for an ambitious and intellectual Eurasianism by raising fundamental issues. We based our argumentation on the obvious fact that the world is in crisis, and that this crisis is caused by liberal globalization, which we identified as Euroatlantism. We believe that the counter-effect needs to be vertical and traditionalist, not horizontal and vulgar. We called this counter-effect Eurasianism, some core ideas of which were explained here. We hope that this essay will have a fecundating impact, thus truly contributing to the further elaboration of intellectual Eurasianism, both from a universal and a Hungarian aspect.

[1] René Guénon: The Crisis of the Modern World Translated by Marco Pallis, Arthur Osborne, and Richard C. Nicholson. Sophia Perennis: Hillsdale, New York. 2004. Pg. 31-32.

[2] Lajos Pálfalvi: Nicolai Trubetskoy's impossible Eurasian mission. In Nicolai Sergeyevich Trubetskoy: Genghis Khan's heritage. (in Hungarian) Máriabesnyő, 2011, Attraktor Publishing, p. 152.

[3] Mikola Ryabchuk: Western "Eurasianism" and the "new Eastern Europe”: a discourse of exclusion. (in Hungarian) Szépirodalmi Figyelő 4/2012

[4] See: Julius Evola: Handbook of Rightist Youth. (in Hungarian) Debrecen, 2012, Kvintesszencia Publishing House, pp. 45–48

00:05 Publié dans Actualité, Affaires européennes, Eurasisme | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : hongrie, jobbik, gabor vona, europe, europe centrale, mitteleuropa, affaires européennes, eurasisme, eurasie, pantouranisme, politique internationale, tradition, traditionalisme |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

花は桜木人は武士(hana wa sakuragi hito wa bushi).

« La fleur des fleurs est le cerisier, la fleur des hommes est le guerrier. »

Les éditions Hermann ont eu la bonne idée de publier le livre d’Emiko Ohnuki-Tierney, Kamikazes, Fleurs de cerisier et Nationalismes, paru précédemment en langue anglaise aux éditions des universités de Chicago (2002) sous le titre Kamikaze, Cherry Blossoms, and Nationalisms : The Militarization of Aesthetics in Japanese History. La traduction de cette étude magistrale est de Livane Pinet Thélot (revue par Xavier Marie). Emiko Ohnuki-Tierney enseigne l’anthropologie à l'université du Wisconsin ; elle est une spécialiste réputée du Japon. Sa carrière académique est exceptionnelle : elle est présidente émérite de la section de culture moderne à la Bibliothèque du Congrès de Washington, membre de l’Avancées de Paris et de l'Académie américaine des arts et des sciences.

Kamikazes, Fleurs de cerisier et Nationalismes n’est pas une histoire de bataille. L’auteure s’est intéressée aux manipulations esthétiques et symboliques de la fleur de cerisier par les pouvoirs politiques et militaires des ères Meiji, Taishô et Shôwa jusqu’en 1945. La floraison des cerisiers appartient à la culture archaïque japonaise, elle était associée à la fertilité, au renouveau printanier, à la vie. L’éphémère présence de ces fleurs blanches s’inscrivait dans le calendrier des rites agricoles, lesquels culminaient à l’automne avec la récolte du riz, et étaient le prétexte à libations d’alcool de riz (saké) et festivités. Au fil des siècles, les acteurs politiques et sociaux ont octroyé une valeur différente au cerisier : l’empereur pour se démarquer de l’omniprésente culture chinoise et de sa fleur symbole, celle du prunier ; les samouraïs et les nationalistes pour souligner la fragilité de la vie du guerrier, et, surtout pour les seconds, institutionnaliser une esthétique valorisant la mort et le sacrifice. Emiko Ohnuki-Tierney nous révèle l’instrumentalisation des récits, des traditions et des symboles nippons, ayant pour toile de fond et acteurs des cerisiers et des combattants : le Manyôshû (circa 755 ap. JC), un recueil de poèmes mettant en scène les sakimori (garde-frontières en poste au nord de Kyûshû et sur les îles de Tsushima et d’Iki) ont été expurgés des passages trop humains où les hommes exprimaient leur affection pour leurs proches de manière à mettre en avant la fidélité à l’empereur. L’épisode des pilotes tokkôtai survint à la fin de la guerre du Pacifique et atteint son paroxysme au moment où le Japon est victime des bombardements américains et Okinawa envahi. Ces missions suicides ont marqué les esprits (c’était l’un des objectifs de l’état-major impérial) et donné une image négative du combattant japonais, dépeint comme un « fanatique »... Avec une efficacité opérationnelle faible, après l’effet de surprise de Leyte (où 20,8% des navires ont été touchés), le taux des navires coulés ou endommagés serait de 11,6%....Tragique hasard de l’Histoire, la bataille d’Okinawa s’est déroulée au moment de la floraison des cerisiers, donnant une touche romantique à cette irrationnelle tragédie, durant laquelle le Japon va sacrifier la fine fleur de sa jeunesse.