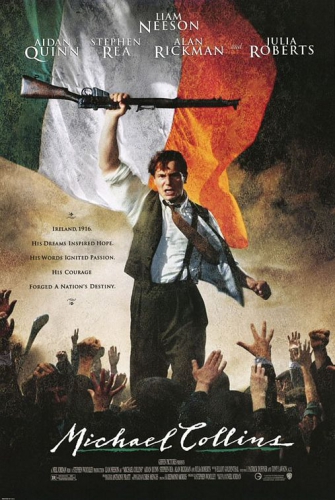

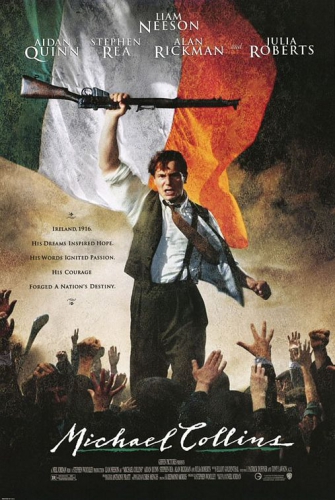

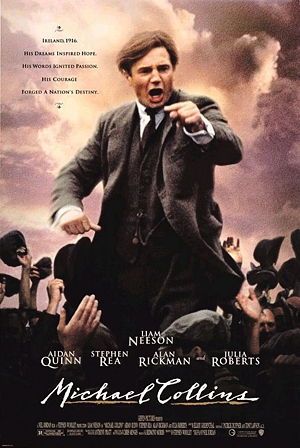

Michael Collins is a must see for any revolutionary, especially those who feel all hope is lost. The film begins with defeat for the revolutionaries, and the survivors hiding like rats in underground tunnels. By the end, they are dictating policy in councils of state. For a White Nationalist, the rise of the eponymous hero is consistently inspiring.

But there is also the fall. Michael Collins shows the petty rivalries, greed, and political miscalculations that can destroy any movement from within.

This is not a paean to militancy for militancy’s sake. It is a warning of the costs of violence and the inevitability of betrayal. Perhaps more importantly, it shows how the end of a friendship can lead to the collapse of a state. It’s a graduate course in nationalist revolution.

It should be noted that we’ll look at this film mostly on its own terms, ignoring some of the historical errors. Chief among them is the horrifically unfair treatment of Éamon de Valera, easily the dominant Irish political figure of the 20th century. While these errors detract from the film, they do not destroy the film’s importance nor the lessons it has to teach us.

Lesson 1 – The Blood Sacrifice Establishes the State

Michael Collins begins [3] with the Easter Rising of 1916. A sweeping panoramic of a scene of battle eventually ends on the General Post Office [4] in Dublin, where Michael Collins (Liam Neeson) and the other Irish Volunteers are utterly outmatched by British soldiers using artillery. They surrender and are marched out, in uniform, by business-like British officers who contemptuously refer to the uprising as a “farce.”

Of course, in real life it was a farce, and far from popular among the Irish people. Many Irish had relatives fighting in the British Army during World War I, and the feeling of many in the Empire was that the Rising was a unforgivable stab in the back while Great Britain was fighting for its life on the battlefields of Europe. In some areas, Irish civilians physically fought with the Volunteers, and some were even killed. In actuality, it was a rather pathetic spectacle, with a tinpot army marching about in uniforms while their own nominal leader (Eoin MacNeill [5]) tried to stop it.

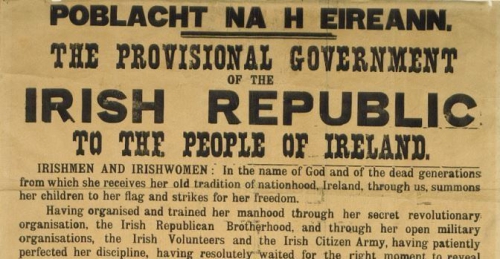

None of this matters. The British, quite justifiably from their point of view, made the decision to execute the leaders of the rebellion. We see Éamon de Valera (Alan Rickman) writing a letter to Michael Collins while the now legendary figures of Connelly, Pearse, and Clarke are executed one by one in the background. De Valera is spared because he is an American citizen and writes to Collins, “The Irish Republic is a dream no longer. It is daily sealed by the lifeblood of those who proclaimed it. And every one of us they shoot brings more people to our side.”

Michael O’Meara writes in “Cú Chulainn in the GPO [6]” in Toward the White Republic that the violent birth of the Irish Republic was no accident. It the living out of a myth [7], a “noble Ireland won by violent, resolute, virile action” inspired by “millenarian Catholicism (with its martyrs), ancient pagan myth (with its heroes), and a spirit of redemptive violence (couched in every recess of Irish culture)” (p. 55).

The “slaughtered sheep” would brighten “the sacramental flame of their spirit.” O’Meara concludes that the sacrifice was not just for Ireland, but for a spiritual rebirth that would justify the Irish nation’s renewed existence, “for the sake of redeeming, in themselves, something of the old Aryo-Gaelic ways” (p. 59).

Once the sacred blood of revolutionaries was spilled, the Irish Republic became real, though it possessed no currency, territory, or international recognition. The policies enacted by the Irish Republic headed by de Valera became the political expression of the Irish nation, rather than a mummer’s farce of self-important and deluded men. The blood of fallen patriots made it real, the reaction of the British Empire granted it recognition, and the support of the Irish people followed in the wake of martyrdom. By losing, the Irish Volunteers won, for as Pearse said, “To refuse to fight would have been to lose. We have kept faith with the past, and handed down a tradition to the future” (p. 59).

Or, as de Valera put it in the film, “And from the day of our release, Michael, we must act as if the Republic is a fact. We defeat the British Empire by ignoring it.”

In the American experience, there are already proto-nationalist “governments” and states in exile. Harold Covington’s “Northwest American Republic [8],” the “Southern National Congress,” and the League of the South, and innumerable other would-be Founding Fathers make claims to be the political expression of various peoples. However, without the blood sacrifice, and the “recognition” granted by the military repression and extreme political reaction, such movements remain in the realm of myth [9].

Of course, that is where all nationalist movements have to begin.

Lesson 2 – The Transfer of Legitimacy Is Mental Before It is Political

In the American context, there’s a tiresome emphasis on individual “freedom,” which has become an all but meaningless phrase. In response, one should remember the admonition of Italian nationalist leader Giuseppe Garibaldi, that “Without Country you have neither name, token, voice, nor rights, no admission as brothers into the fellowship of the Peoples. You are the bastards of Humanity. Soldiers without a banner, Israelites among the nations, you will find neither faith nor protection; none will be sureties for you. Do not beguile yourselves with the hope of emancipation from unjust social conditions if you do not first conquer a Country for yourselves.”

Michael Collins believes something similar. As an organizer addressing a restive crowd soon after his release from prison, his theme is not that the British are “unfair” or that the Irish need “equality.” He tells the people that the Irish nation already exists, though it’s legitimate leaders are rotting in English jails. “I was in one myself till a week ago,” he jokes.

He continues [10], “They can jail us, they can shoot us, they can even conscript us. They can use us as cannon fodder in the Somme. But, but! We have a weapon, more powerful than any in the arsenal of their British Empire. And that our weapon is our refusal. Our refusal to bow to any order but our own, any institution but our own.”

Here, Collins skillfully draws the distinction between the institutions of “their” Empire and contrasts it with the legitimate institutions that “we” can build – and bow to. More importantly, pointing aggressively at the “our friends at the Royal Irish Constabulary,” he identifies the people who want to “shut me up” and challenges the Irish people to raise their voices if he is cut down.

This speech pays dividends when Ned Broy (Stephen Rea), a detective working for The Castle (the center of British power in Ireland), warns Collins that the entire cabinet of the Irish Republic is to be arrested. Broy (a composite of the real Ned Broy [11]and other characters) justifies his decision on the grounds that Collins can be “persuasive . . . what was it you said, our only weapon is our refusal.” The Irish Broy (whose name is repeatedly mispronounced by his English superiors) has transferred his loyalty from the state that pays his salary, to the new state that serves as the political expression of his people. This is the “revolution in the hearts and minds of the people” (to use John Adams’s phrase) necessary for any nationalist movement to succeed. It is also the outgrowth of de Valera’s entire strategy of building a parallel system of state.

Lesson 3 – Power Trumps Legalism

Unfortunately, when we see the legitimate political expression of the Irish people in action, it is not impressive. The Cabinet of the Irish Republic is meeting in a tunnel. Dressed in suits and ties and carrying briefcases, they seem unlikely revolutionaries, squabbling over the extent of each minister’s “brief” and constantly pulling rank on one another.

Michael Collins and his sidekick Harry Boland (Aidan Quinn) are in, but not of this bureaucracy. Collins contemptuously dismisses a colleague’s charge that he is simply Minister for Intelligence by saying he’s the Minister for “Gunrunning, Daylight Robbery, and General Mayhem.” Interestingly, de Valera smiles wryly at this.

Collins reveals that the entire Cabinet is to be arrested but Éamon de Valera sees this as an opportunity, not a danger. As President of the Irish Republic, he orders everyone to sleep at home – if they are all arrested “the public outcry will be deafening.” Of course, when de Valera is arrested, he’s dragged into a truck yelling futilely about an “illegal arrest by an illegal force of occupation” – a strange claim from a revolutionary leader. Significantly, Collins and Boland disobey their “chief,” escape capture, and make plans to accelerate their program of guerrilla warfare.

Earlier, we saw Collins leading an attack on an arsenal to capture weapons. He tells his guerrillas that they will be organized in “flying columns” and engage the enemy on nobody’s terms but their own. The resource-conscious Collins warns them each gun must be expected to capture ten more. At the same time, he imposes a core of discipline typical of a standard army.

This dual approach parallels his approach to the state. He recognizes the legitimacy of “his” government, the Irish Republic. His ultimate loyalty is to his “chief,” Éamon de Valera. At the same time, Collins recognizes that a revolutionary army – and government – has to impose costs on its adversary if it is to be effective. To “ignore” the British Empire is enough when it comes to the personal transfer of loyalty necessary for national liberation. However, to actually break the control of the system, there has to be concrete action.

This means breaking the “rules” that normal states obey. A national liberation army will use the “uniform of the man in the street,” the guerrillas will attack and fade away when necessary, and the chain of command must occasionally be violated for tactical reasons.

Lesson 4 – Intelligence Determines the Fate of Insurgencies

Early in the film, Collins is told that British Intelligence “knows what we [had] for breakfast.” In response, he says, “There’s only one way to beat them then. Find out what they had for breakfast.” In order to test whether he can trust Broy, he asks for admittance to The Castle so he can check the files the enemy possess about the Irish liberation movement. He’s stunned at the extent of what they know and comments to Broy, “You could squash us in a week.”

Early in the film, Collins is told that British Intelligence “knows what we [had] for breakfast.” In response, he says, “There’s only one way to beat them then. Find out what they had for breakfast.” In order to test whether he can trust Broy, he asks for admittance to The Castle so he can check the files the enemy possess about the Irish liberation movement. He’s stunned at the extent of what they know and comments to Broy, “You could squash us in a week.”

Nationalists and dissenters sometimes look to asymmetrical warfare as an invincible tactic for defeating the system. In reality, it is the weapon of the weak, and the price of weakness is that you most often lose. A powerful system can infiltrate, subvert, and destroy revolutionary organizations through legal pressure on individuals, financial enticements to informers, and well-trained double agents. It’s no coincidence that the quasi-government Southern Poverty Law Center openly styles itself as a secret police force with an “Intelligence Report” used to destroy the personal lives of people they don’t like.

Lacking financial resources and functioning bureaucracies, a revolutionary group has to rely on the iron character of its members, and while this sounds idealistic and proud, the hard reality is that no group in history has been free of human weakness. As Americans learned in Iraq and Afghanistan during successful counter-insurgency operations, even groups that think they are fighting for God are capable of being corrupted. Any revolutionary movement can be penetrated, and once it is penetrated, it is easily destroyed.

Collins is aware of this, and comments to his men, “Any of ye who have read Irish history know that movements like ours have always been destroyed by paid spies and informers.” However, “without [informers], the Brits would have no system, they couldn’t move.” In response to this reality, there is only one thing to do. Cigarette hanging out of his mouth like a gangster, he dictates a letter. “To whom it may concern: This is to inform you that any further collaboration with the forces of occupation will be punishable by death. You have been warned. Signed, the Irish Republican Army.”

Here, Michael Collins establishes a strategic objective. “Now imagine Dublin with The Castle like an enclave, where anyone, and I mean anyone who collaborated knew he’d be shot. They wouldn’t be able to move outside those fucking walls.” We have only to look at the American experience in Iraq guarding informers or the Mexican struggle against narco guerrillas (where the police cover their faces out of fear) to know that nothing has changed.

The one advantage a nationalist revolutionary has is that he knows the terrain better than the people he is fighting. If both sides are fully dependent for intelligence on their own resources, without the benefit of paid informers, the nationalists are going to win. After all, they are fighting amidst their own people.

One thing Michael Collins exploits throughout the entire film is that no one (other than Broy) knows what he looks like. This is remarkably unlikely in the film, seeing as how Collins is so bold as to go up and talk to various policeman. Furthermore, for our purposes, this is hardly a realistic strategy in the age of street cameras, social networking, and ubiquitous smart-phones and video.

Nonetheless, revolutionaries don’t have to make it easy for the enemy’s intelligence gathering efforts – so maybe you should take a second look at what you’ve put on your Facebook profile.

Lesson 5 – Make the Political Disagreement a Personal Cost

Collins sets up the “12 Apostles” who systematically murder collaborators and secret policemen. These are men, after all, who are just doing their job to protect the established system. The film takes care to show that some of them are churchgoers and prayerful men, hardly moral monsters. Nonetheless, they must die.

Collins makes his political struggle very personal. Earlier, an outraged policeman shouts at a captured IRA member that he won’t give in to their demands. “What, give up our jobs, and miss out on all the fun?” In response, the IRA member spits back, “Or face the music.”

In this context, obviously this means violence. However, this lesson also applies in “normal” politics.

Certainly white advocates know, often with bitter personal experience, the costs of standing for your beliefs. Though these costs can be exaggerated, jobs, “friends,” and even family have been known to turn on white advocates once they are “outed” or targeted for extermination by the powers that be. A huge number of would-be white advocates are simply too intimidated by the social or financial costs to engage in racial or Traditionalist activism, and so instead they engage in harmless distractions (like libertarianism or Republicanism) or simply drop out altogether.

However, Leftists have also paid the price for political activity on occasion following campaigns by their political opponents. Few political activists – of whatever opinion – can survive in the midst of a personal campaign against them. Even in normal bourgeois politics, we are familiar with the term “throwing someone under the bus.”

A winning political movement increases the costs of association with an opposing political movement. This is all Michael Collins really does – an informer or collaborator has to consider for the first time whether the benefit of payment outweighs the possible cost of violent death. As the spiritual momentum is on the Irish nationalist side, Collins has changed the entire momentum of the conflict.

There’s a word to describe an effort by one group to break the will of another. That word is war – and politics is simply war by the other means.

Thus, Collins freely admits that he “hates” the British. He hates them not because of their race or religion, but because there is no other way. “I hate them for making hate necessary.”

Lesson 6 – Weakness is worse than cruelty; symbolism must be backed by power

While Michael Collins and Harry Boland are waging their guerrilla war, Éamon de Valera is rotting in an English jail. However, he manages to sneak out a copy of the key, and Collins and Boland manage to rescue their chief. Éamon de Valera is seen in a mass rally in Dublin, while the British police stare at him powerless. However, de Valera repeats his earlier mistake and decides that he wants to go to America to seek recognition from the American President. Perhaps more importantly, he takes Harry Boland with him.

It is left to Michael Collins to continue the war, which escalates when the arrival of MI5 Operative Soames (Charles Dance aka Tywin Lannister). Soames suspects Broy, possibly because the latter is constantly correcting his superior as to the proper pronunciation of his Irish name. He catches Broy in the act and has him killed, but is killed himself when Collins launches the assassinations of November 21, 1920 (Bloody Sunday).

When de Valera returns to Ireland having failed to secure diplomatic recognition, he begins a bureaucratic offensive against Collins. He orders the IRA to abandon guerrilla tactics because it allows the British press to call them “murderers.” Instead, he wants large-scale engagements, such as an attack on the Customs House. The attack leads to devastating losses among Republican forces (though the movie neglects to show its positive propaganda effects). Not surprisingly, Collins sneers at the “heroic ethic of failure” of 1916. There is no need for a further blood sacrifice – the British must be brought to their knees “they only way they know how.”

Saul Alinsky wrote in Rules for Radicals that the concern with means and ends varies inversely with one’s proximity to the conflict. Or, as Michael Collins protests to de Valera, “War is murder! Sheer, bloody murder! Had you been here you’d know that!” The attack on the Customs House almost breaks the IRA, and Collins believes that the rebellion is within days of being destroyed in the aftermath.

Éamon de Valera is conscious of his own dignity and the dignity of the Irish Republic as a “legitimate” government. It is not surprising that he favors tactics typical of a “normal” state. However, a revolutionary state is by definition not “normal.” Concessions are won not with fair play and appeals to common principles, but with force. In international relations, little has changed since Thucydides – “the strong do what they can and the weak suffer what they must.” Paradoxically, the Irish Republican (or any revolutionary state) can only be brought into existence by methods that can be characterized as “illegitimate.”

Lesson 7 – The head of a revolutionary movement must participate in, if not command, the war effort

Éamon de Valera was no coward, having participated in the Easter Rising of 1916. However, throughout the film, de Valera shows a curious inability to recognize what is actually happening on the ground. He sees no problem in taking Michael Collins’s most trusted lieutenant Harry Boland at a critical moment in the guerrilla struggle for what is essentially a public relations mission. His attack on the Customs House is launched despite the blunt warning of Michael Collins that it will lead to disaster.

Éamon de Valera was no coward, having participated in the Easter Rising of 1916. However, throughout the film, de Valera shows a curious inability to recognize what is actually happening on the ground. He sees no problem in taking Michael Collins’s most trusted lieutenant Harry Boland at a critical moment in the guerrilla struggle for what is essentially a public relations mission. His attack on the Customs House is launched despite the blunt warning of Michael Collins that it will lead to disaster.

It’s suggested that most of this is motivated by de Valera’s jealousy of Collins and his desire to eliminate a political rival. When Collins and Boland break de Valera out of prison, there is a brief moment of comradely laughter before the chief mentions unpleasantly that he can see the two of them are having a good time because he “reads the papers.” When he returns from America, he is picked up by one of Collins’s aides who tells him “the Big Fella (Collins) sends his regards.” Éamon de Valera spits back, “We’ll see who is the big fella.”

The film strains to present Éamon de Valera as selfish, perhaps even evil, but most of his actions are more than justified from a political perspective. Irish independence is, after all, dependent on negotiations with the British, and there is a strong case to be made that they will not negotiate with people they consider to just be savage murderers. Furthermore, American pressure on Britain in the midst of World War I would have been an invaluable asset to the Irish diplomatic effort. Finally, as President of the Irish Republic, de Valera would be insane to allow a powerful rival with military backing emerge as a separate power center within the government. Removing Boland is a potent political step – as Collins himself recognizes. “We were too dangerous together,” he muses to Boland when the break is beyond healing.

The problem is that all of this political maneuvering should be secondary to his primary role of leading a military effort. Though de Valera is obviously commander in chief, he has little connection to actual military operations throughout the film. This is at least a partial explanation for his stunning strategic incompetence.

Throughout the film, there is a fatal separation between the head of the state, the development of strategy, and the execution of a guerrilla war. Éamon de Valera bears heavy responsibility for this because of his disastrous choice to abandon the field for America. This dereliction of duty ultimately forced Collins to take almost sole command of the war for independence, despite his personal loyalty to his President. Éamon de Valera had to act as he did in order to maintain his political leadership, but his ceding of military leadership had catastrophic consequences. If he had stayed in Ireland, none of his political maneuvering would have been necessary.

In a revolutionary movement, there can be no separation between the so-called “civilian” and military leadership. It is a thinly veiled fiction in our democracies anyway. The conflict between Michael Collins and Éamon de Valera was inevitable once the President of the Irish Republic saw his role as being a political leader, rather than a military “chief.”

Lesson 8 – The nationalist myth cannot be undone by pragmatism – even if the myth is becoming destructive

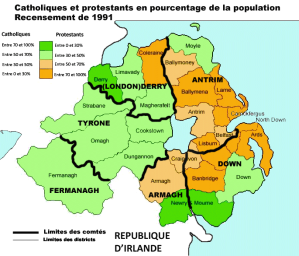

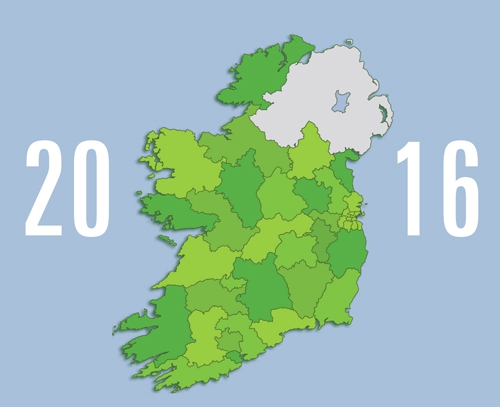

The final section of the movie focuses of the Irish Civil War. Michael Collins brings back the Anglo-Irish Treaty, which creates the Irish Free State, not the Irish Republic. The two most controversial elements of the treaty are an oath of allegiance to the British Crown and the partition of Northern Ireland.

The reunion between Michael Collins and his former sidekick Harry Boland is hardly joyful. Collins appears embarrassed as Boland asks him in horror, “Mick, is this true?”

Collins quickly turns his wrath on Éamon de Valera. “It was the best anyone could have got. And more important Dev knew it. He wanted somebody else to bring back the bad news.” Éamon de Valera for his part screams at Collins, “You published the terms without my agreement!” Collins challenges de Valera to stand by the treaty if the Irish people stand by it; de Valera is silent.

Instead, we see Éamon de Valera giving a passionate speech in front of a giant Irish tricolor. “This treaty bars the way to the Republic with the blood of fellow Irishmen! And if it is only through civil war that we can get our independence then so be it!”

When the debate takes place in the Dail, one of Collins’s political opponents charges, “When the people of Ireland elected us to represent the Republic, did they think we were liars. . . . Mr. Collins would have us take an oath of allegiance to a foreign king.” Collins wins narrow approval through his reputation and his plea to “save the country” from “a war none of us can even contemplate.” Nonetheless, Éamon de Valera refuses to accept the treaty, saying it can “only subvert the Republic” and continues his opposition even after the treaty is ratified by a referendum of the Irish people.

When the Irish Volunteers began their rebellion against the Treaty in the Irish Civil War, Collins is outraged when he is told that Churchill is offering the Irish Free State artillery. “Let Churchill do his own dirty work!” he rages. An aide responds, “Maybe he will Michael, maybe he will.” Collins has to put down the rebellion or risk the British seizing control. In uniform, with all the power of a modern state behind him, a disgusted Collins orders the artillery bombardment of a rebel stronghold. The opening scene is now reversed, with Michael Collins in the position of the British bombing the heroes of Easter 1916.

When Harry Boland is killed, Collins reacts with rage against the boy who shot him. “You killed him, you little uniformed git. You plugged him, you little Free State gobshite. You were meant to protect him!” Instead of the picture of Michael Collins we are familiar with, proud and dignified in his Free State uniform, Collins is disgusted with himself. After all, he is bombing his former comrades with weapons provided by the British Empire, in order to preserve a state nominally pledged to service of a foreign king.

Michael Collins was ultimately right that the Irish Free State was simply a “stepping stone to the ultimate freedom” for most of Ireland. Given the IRA’s weak military situation by the end of the war, the Irish Free State probably was, as Collins claimed, “the best anyone could have got.” As Collins’s supporters in the Dail pointed out, nowhere in the exchange of letters that preceded negotiations was the recognition of the Irish Republic made as a demand. Given that the Irish would gain a government of their own that they could use to “achieve whatever they wanted,” it does seem foolish to go to war “over the form of words.”

However, revolutions have a terrible logic all their own. The heroic myth of the nation rising to self-consciousness through the sacrament of the blood sacrifice is impervious to pragmatic considerations. Why did the Irish suffer and die if only to end up as subjects to the British Crown? How can any Irish patriot wear the uniform of a government that fires on Irishmen with British supplied weapons?

When Éamon de Valera and his deputies leave the hall, Collins screams, “Traitors! Traitors all!” But traitors to whom? Even Michael Collins seems to despise the uniform he wears. Nonetheless, he has made the (in my judgment, correct) rational decision that the Irish Free State is the best hope of achieving the national aspirations of the Irish people and that patriots owe it their allegiance. But myths are impervious to reason. The romantic impulses that can launch a revolution can also destroy it, if not controlled.

Saul Alinsky writes in Rules for Radicals that organizers must be masters of “political schizophrenia.” They must sincerely believe in what they are doing, if only to give them the strength of will to carry forward in difficult times. However, they should never become a “true believer” in the sense of fully internalizing their own propaganda. The point of politics is to achieve concrete ends, not simply to remain true to a dream.

The Myth of nationalist (and racial) redemption is True in some platonic sense. That doesn’t mean it has to be a suicide pact. Revolutionaries have to be willing to die for the dream, but idealism does not exempt them from the laws of political reality.

Lesson 9 – Revolutionary moments create opportunities that are lost in time, but they should be seized incrementally

While Collins was ultimately correct about the short-lived nature of even nominal British control over the Free State, the division of the North was fatal to hopes of a united Ireland. To this day, Ireland remains split, and the British flag flies over Ulster despite decades of revolutionary agitation and violent resistance.

Part of this has to do with the utter corruption of the Irish nationalist movement in the decades after his death. So-called Irish nationalists like Sinn Fein have been reduced to arguing that the Republic desperately needs more black immigrants. In the centuries-long struggle between Catholics and Protestants, the winners might be the Nigerians.

There’s also the more substantial question as to whether Ulster Protestants under the Red Hand constitute a separate people, rather than simply existing as an outgrowth of British colonialism. Irish sovereignty over Ulster could be interpreted simply as another form of occupation.

However, from the viewpoint of contemporary Irish nationalists, the acquiescence to division of the country has to be seen as a disaster. The revolutionary momentum of the Free State period was ultimately lost as people reconciled themselves with the status quo of division. If a united Ireland was held to be truly non-negotiable, it had to have been accomplished within only a few years of the formation of the state. Instead, the status quo provides a fatal opening for “moderates” and “realists” to sell out the long term dream of unity for smaller political advantages.

In fairness, Michael Collins never fully reconciled himself to the division of Ireland. At the time of his death, he was planning a new offensive [12] in the North, this time with the backing of state power. Again, to turn to Alinsky, this is the proper course of action given political realities. Revolutionaries should always be ready to accept incremental gains, but should also continue moving the goal posts until they reach their ends. Certainly, the Left has been a master of this over the last century, as each new concession simply fuels the demand for more surrender by conservatives.

Revolutionaries should take what they can get – but never concede that the struggle is finished until they can get all of it. The tragedy for Irish nationalists is that the more “extreme” anti-Treaty partisans may have destroyed the hope of a united Ireland by killing Michael Collins. Michael Collins’s approach may have been more complicated and less ideologically satisfying, but ultimately more likely to succeed.

Lesson 10 – Draft the People

James Mason writes in Siege that white revolutionaries must see all white people as their “army.” The fact that they do not support us now is irrelevant – eventually, they will be drafted.

The IRA’s assassination campaign imposes great costs on the Irish people as a whole. The arrival of the auxiliaries and the Black and Tans unquestionably made life more difficult for ordinary people. The murder of the Cairo Gang led the British to strike back in a wild frenzy at an Irish football game, leading to the deaths of many ordinary people who had nothing to do with the political struggle. In the film, Collins rages at the brutality of the British. In practice, this is deeply dishonest. It’s only to be expected that the IRA’s campaign would lead to greater repression of the Irish people.

Terrorism and violent resistance may make life more difficult for the people you are trying to represent. This is not an unfortunate side effect – it is an intended reaction. Revolutionary movements should seek to expose the repression inherent in the system by refusing to let the authorities hide behind half measures. More importantly, a successful revolutionary campaign forces everyone in the country to take a side. It removes neutrality as an option. As the system can only maintain control by imposing greater costs upon the population, a revolutionary campaign that makes life worse for the people may have the paradoxical effect of garnering greater popular support.

As a revolutionary, you are taking upon yourself the responsibility of “dragging the people into the process of making history,” to use Dugin’s phrase. This requires a stern code of personal responsibility so as to live up to this mission. It also necessitates a willingness to pay a personal price. However, the most important quality revolutionaries have to possess is the moral courage to accept that you will be the cause of suffering among your own people. And when the time comes, like Michael Collins, you must do what is necessary to end that suffering.

Lesson 11 – Impose shared sacrifice and experiences among the leadership

It is no use calling for “unity” among the political leadership of revolutionary movements. By definition, anyone who is attracted to a revolutionary movement is going to be ideologically nonconformist and willing to risk all for the sake of principle. You put a group of these people in a room and they are going to fight about something eventually.

However, Michael Collins gives a different interpretation to the eventual break between Harry Boland and Michael Collins. Boland is in love with Kitty (Julia Roberts) but she wants to be with Collins. The growth of the relationship between Kitty and Collins moves in tandem with the collapse of the friendship between Boland and Collins. Though Collins continues to pledge his friendship to Boland, it is easy to understand Boland’s wrath at a man who essentially stole his girlfriend. Within the context of the film, the ideological differences between Boland and Collins seem like after the fact justifications for a rivalry based in petty personal conflict.

That said, there’s a deeper lesson to seen if the romantic triangle is interpreted as just a metaphor. Boland, Collins, and de Valera are politically and personally united when they share common experiences and common struggles. When de Valera is being spirited away from British raid to flee to America, Collins tells him, “Remember one thing over there. You’re my chief – always.” It’s only after Éamon de Valera returns from America that conflicts become truly serious. Éamon de Valera is no longer a “chief” but a politician. There is a host of separate experiences now separating Collins and his President.

The break between Boland and Collins follows a similar pattern. When Boland is Collins’s fellow guerrilla, they are inseparable. Despite the romantic tensions between the triangle, Kitty, Boland, and Collins are able to coexist in easy intimacy. However, when Boland and Collins develop separate institutional roles, the personal tension elevates into political rivalries and eventually, opposing camps in the government.

Revolutionary movements have to impose a common body of experience on all members insofar as it is possible. Different perspectives, backgrounds, and skills are all valuable and useful but not if they lead to division. At the risk of sounding like a sensitivity trainer, everyone involved in the movement should have a healthy respect for the circumstances and difficulties that all of them are facing in their different roles.

Conclusion

Several years ago, I recall that a white advocacy group fliers with pictures of Michael Collins in his Irish Free State uniform. Our sophisticated media and the well-trained population immediately interpreted this as a picture of a “Nazi” in uniform, and there was the usual hysteria. This depressing anecdote shows that despite our information saturation, we live in a remarkably uninformed age. Even the millions of Americans of Irish descent have only the most distant knowledge of the Emerald Isle’s long struggle for independence.

White revolutionaries do not have the luxury of ignorance. If the battle for a white ethnostate is to follow the lines of an anti-colonial struggle, the Irish independence movement is the closest thing that we have to a modern model. The period of the Irish Free State and the Civil War shows not only how a successful movement can triumph, but how it can also destroy itself.

Michael Collins is a good beginning for any white revolutionary seeking to define the struggle. The quest for an ethnostate is not a struggle for “freedom” or some silly abstraction, but an order of our own and institutions of our own that will allow us to achieve what we desire as a people. To achieve this requires the power of Myth, the tactics of soldiers, and the skill of politicians. This Easter, commemorate the Rising by watching Michael Collins and absorbing its lessons. Then with more research into this movement and others, prepare for the Rising to come.

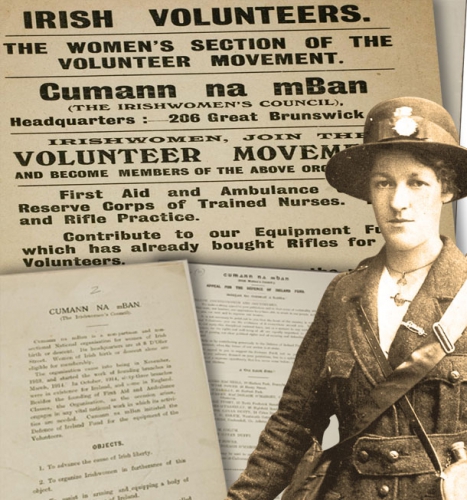

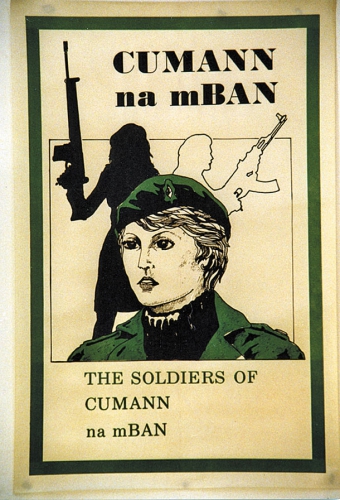

Ce même jour, les Dublinois eurent la surprise de voir 70 femmes armées de fusils pénétrer dans la cité dans un ordre impeccable. Elles savaient toutes ce qui les attendait. Pourtant, elles avançaient sans hésitation. C’était le Cumann na mBan.

Ce même jour, les Dublinois eurent la surprise de voir 70 femmes armées de fusils pénétrer dans la cité dans un ordre impeccable. Elles savaient toutes ce qui les attendait. Pourtant, elles avançaient sans hésitation. C’était le Cumann na mBan.

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

Early in the film, Collins is told that British Intelligence “knows what we [had] for breakfast.” In response, he says, “There’s only one way to beat them then. Find out what they had for breakfast.” In order to test whether he can trust Broy, he asks for admittance to The Castle so he can check the files the enemy possess about the Irish liberation movement. He’s stunned at the extent of what they know and comments to Broy, “You could squash us in a week.”

Early in the film, Collins is told that British Intelligence “knows what we [had] for breakfast.” In response, he says, “There’s only one way to beat them then. Find out what they had for breakfast.” In order to test whether he can trust Broy, he asks for admittance to The Castle so he can check the files the enemy possess about the Irish liberation movement. He’s stunned at the extent of what they know and comments to Broy, “You could squash us in a week.”

Éamon de Valera was no coward, having participated in the Easter Rising of 1916. However, throughout the film, de Valera shows a curious inability to recognize what is actually happening on the ground. He sees no problem in taking Michael Collins’s most trusted lieutenant Harry Boland at a critical moment in the guerrilla struggle for what is essentially a public relations mission. His attack on the Customs House is launched despite the blunt warning of Michael Collins that it will lead to disaster.

Éamon de Valera was no coward, having participated in the Easter Rising of 1916. However, throughout the film, de Valera shows a curious inability to recognize what is actually happening on the ground. He sees no problem in taking Michael Collins’s most trusted lieutenant Harry Boland at a critical moment in the guerrilla struggle for what is essentially a public relations mission. His attack on the Customs House is launched despite the blunt warning of Michael Collins that it will lead to disaster.

En 1919, la lutte pour l'indépendance de l'Irlande vient de débuter. Les sombres Black and Tans poursuivent inlassablement les rebelles indépendantistes. Le petit village de Clonmore est l'un des théâtres d'opération. Volontaire républicain, Denis O'Hara apprend au cours de la descente que la police investira le lieu d'une réunion secrète, qui doit se tenir non loin de Dublin, afin de discuter des actions à mener. Afin de déjouer l'arrestation de chacun, O'Hara tente de prévenir ses camarades mais est touché par une balle etbbientôt appréhendé. Son arrestation le fait échouer dans sa tentative. O'Hara est emprisonné à Kildare. Sans nouvelle du jeune homme, la famille du prisonnier le croit mort. Sa mère perd la vue sous le choc de la nouvelle tandis que sa fiancée Moira est enlevée par Gilbert Beecher, traitre acquis aux loyalistes. Le jeune O'Hara parvient néanmoins à s'échapper et regagner son village...

En 1919, la lutte pour l'indépendance de l'Irlande vient de débuter. Les sombres Black and Tans poursuivent inlassablement les rebelles indépendantistes. Le petit village de Clonmore est l'un des théâtres d'opération. Volontaire républicain, Denis O'Hara apprend au cours de la descente que la police investira le lieu d'une réunion secrète, qui doit se tenir non loin de Dublin, afin de discuter des actions à mener. Afin de déjouer l'arrestation de chacun, O'Hara tente de prévenir ses camarades mais est touché par une balle etbbientôt appréhendé. Son arrestation le fait échouer dans sa tentative. O'Hara est emprisonné à Kildare. Sans nouvelle du jeune homme, la famille du prisonnier le croit mort. Sa mère perd la vue sous le choc de la nouvelle tandis que sa fiancée Moira est enlevée par Gilbert Beecher, traitre acquis aux loyalistes. Le jeune O'Hara parvient néanmoins à s'échapper et regagner son village... Dublin en 1903, Michael O'Brien est capturé. L'activiste indépendantiste est suspecté d'un attentat meurtrier sur des policiers de Sa Majesté. La justice condamne le jeune O'Brien à mort après une parodie de procès. Pendant sa détention, sa fiancée enceinte Maeve Fleming le visite en prison et obtient l'autorisation de l'épouser avant qu'il ne soit pendu. O'Brien lui remet une croix d'argent qu'arborent les nationalistes irlandais et sur laquelle sont gravés les mots "Ma vie" et "Irlande". Puisse cette croix revenir un jour au fils qu'O'Brien ne verra jamais... 1921, O'Brien n'aura effectivement jamais connu son fils qui passe cette année-là son baccalauréat dans un collège anglais. Sa condition de fils d'un rebelle lui a imposé une éducation spécifique par l'occupant sous la férule de Sir George Baverly qui veut en faire un parfait Britannique. Ainsi sont éduqués les mauvais Irlandais comme Michael Jr. Il se peut qu'il en faille plus qu'un conditionnement sous haute surveillance pour transformer un fils de rebelle en fidèle sujet de la Couronne...

Dublin en 1903, Michael O'Brien est capturé. L'activiste indépendantiste est suspecté d'un attentat meurtrier sur des policiers de Sa Majesté. La justice condamne le jeune O'Brien à mort après une parodie de procès. Pendant sa détention, sa fiancée enceinte Maeve Fleming le visite en prison et obtient l'autorisation de l'épouser avant qu'il ne soit pendu. O'Brien lui remet une croix d'argent qu'arborent les nationalistes irlandais et sur laquelle sont gravés les mots "Ma vie" et "Irlande". Puisse cette croix revenir un jour au fils qu'O'Brien ne verra jamais... 1921, O'Brien n'aura effectivement jamais connu son fils qui passe cette année-là son baccalauréat dans un collège anglais. Sa condition de fils d'un rebelle lui a imposé une éducation spécifique par l'occupant sous la férule de Sir George Baverly qui veut en faire un parfait Britannique. Ainsi sont éduqués les mauvais Irlandais comme Michael Jr. Il se peut qu'il en faille plus qu'un conditionnement sous haute surveillance pour transformer un fils de rebelle en fidèle sujet de la Couronne... Pâques 1916, l'atmosphère est lourde dans la cité dublinoise. Chacun sent bien que des événements vont se produire. Si la rébellion d'une poignée d'insoumis irlandais éclate bien, l'issue des combats ne laisse aucun doute tant la supériorité technique des troupes anglaises est remarquable. Nombre de patriotes irlandais sont tués dans les combats. Beaucoup d'autres sont arrêtés, tel Eamon De Valera, président du Sinn Fein. On fusille des prisonniers parmi lesquels le révolutionnaire national-syndicaliste Connolly. L'insurrection est noyée dans le sang et provoque une détermination infaillible chez les survivants. Parmi les jeunes insurgés à avoir échappé à la mort, Michael Collins se jure que 1916 constituera le dernier échec des indépendantistes. Face à un ennemi supérieur en armes, la surprise doit-elle prévaloir. Aussi, la priorité est-elle l'élimination des espions. Avec l'aide de son fidèle ami Harry Boland et l'appui d'un informateur anglais, Collins devient le héraut républicain, entreprend la neutralisation des traitres et prépare une véritable stratégie de harcèlement militaire qui porte ses fruits. Le traité de 1921 accorde l'indépendance à la majeure partie de l'île. L'Ulster reste sous domination britannique, faisant se déchirer la famille républicaine...

Pâques 1916, l'atmosphère est lourde dans la cité dublinoise. Chacun sent bien que des événements vont se produire. Si la rébellion d'une poignée d'insoumis irlandais éclate bien, l'issue des combats ne laisse aucun doute tant la supériorité technique des troupes anglaises est remarquable. Nombre de patriotes irlandais sont tués dans les combats. Beaucoup d'autres sont arrêtés, tel Eamon De Valera, président du Sinn Fein. On fusille des prisonniers parmi lesquels le révolutionnaire national-syndicaliste Connolly. L'insurrection est noyée dans le sang et provoque une détermination infaillible chez les survivants. Parmi les jeunes insurgés à avoir échappé à la mort, Michael Collins se jure que 1916 constituera le dernier échec des indépendantistes. Face à un ennemi supérieur en armes, la surprise doit-elle prévaloir. Aussi, la priorité est-elle l'élimination des espions. Avec l'aide de son fidèle ami Harry Boland et l'appui d'un informateur anglais, Collins devient le héraut républicain, entreprend la neutralisation des traitres et prépare une véritable stratégie de harcèlement militaire qui porte ses fruits. Le traité de 1921 accorde l'indépendance à la majeure partie de l'île. L'Ulster reste sous domination britannique, faisant se déchirer la famille républicaine...

Pâques 1916 en Irlande. Les troubles agitent Dublin. L'insurrection..., Nora Clitheroe aimerait s'en tenir la plus éloignée possible. Mais voilà..., son époux Jack vient d'être nommé par le général Connolly commandant d'une unité. L'époux doit prendre immédiatement ses fonctions. Les dirigeants du Sinn Fein viennent de proclamer l'indépendance. Une indicible peur envahit l'épouse lorsqu'elle apprend que l'homme qu'elle aime éperdument reçoit l'ordre d'investir le bâtiment des Postes. Les rebelles possèdent l'avantage de la surprise et se battent vaillamment. Mais les nombreuses forces loyalistes écrasent sans difficultés la hardiesse des volontaires irlandais. Poursuivi sur les toits de la cité, Jack peine à retrouver Nora tout en continuant de tirer ses cartouches. Son amour pour Nora ne le fera guère abandonner la lutte armée...

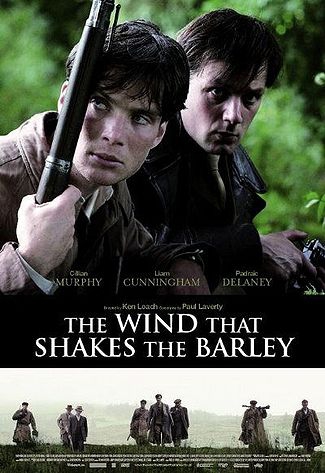

Pâques 1916 en Irlande. Les troubles agitent Dublin. L'insurrection..., Nora Clitheroe aimerait s'en tenir la plus éloignée possible. Mais voilà..., son époux Jack vient d'être nommé par le général Connolly commandant d'une unité. L'époux doit prendre immédiatement ses fonctions. Les dirigeants du Sinn Fein viennent de proclamer l'indépendance. Une indicible peur envahit l'épouse lorsqu'elle apprend que l'homme qu'elle aime éperdument reçoit l'ordre d'investir le bâtiment des Postes. Les rebelles possèdent l'avantage de la surprise et se battent vaillamment. Mais les nombreuses forces loyalistes écrasent sans difficultés la hardiesse des volontaires irlandais. Poursuivi sur les toits de la cité, Jack peine à retrouver Nora tout en continuant de tirer ses cartouches. Son amour pour Nora ne le fera guère abandonner la lutte armée... Les années 1920 en Irlande. Des bateaux entiers déversent leur flot de Black and Tans pour mâter les rebelles qui poursuivent la lutte pour l'indépendance après l'échec de l'insurrection de Pâques 1916. Les exactions sont nombreuses et la répression britannique impitoyable. A l'issue d'un match de hurling dans le comté de Cork, Damien O'Donovan voit son ami Micheál Ó Súilleabháin sommairement exécuté sous ses yeux. Malgré quelques hésitations, Damien plaque la jeune carrière de médecin qu'il devait débuter dans l'un des plus prestigieux hôpitaux londoniens pour rejoindre son frère Teddy, commandant de la brigade locale de l'I.R.A. Dans tous les comtés, des paysans rejoignent les rangs des volontaires républicains et bouter l'Anglais hors de l'île. Au prix de leur sang, et d'indicibles tourments, les volontaires de l'I.R.A. changeront le cours de l'Histoire...

Les années 1920 en Irlande. Des bateaux entiers déversent leur flot de Black and Tans pour mâter les rebelles qui poursuivent la lutte pour l'indépendance après l'échec de l'insurrection de Pâques 1916. Les exactions sont nombreuses et la répression britannique impitoyable. A l'issue d'un match de hurling dans le comté de Cork, Damien O'Donovan voit son ami Micheál Ó Súilleabháin sommairement exécuté sous ses yeux. Malgré quelques hésitations, Damien plaque la jeune carrière de médecin qu'il devait débuter dans l'un des plus prestigieux hôpitaux londoniens pour rejoindre son frère Teddy, commandant de la brigade locale de l'I.R.A. Dans tous les comtés, des paysans rejoignent les rangs des volontaires républicains et bouter l'Anglais hors de l'île. Au prix de leur sang, et d'indicibles tourments, les volontaires de l'I.R.A. changeront le cours de l'Histoire... Dieses Jahr begeht Irland den

Dieses Jahr begeht Irland den

Republikanische Parteien Irlands, wie etwa die „Sinn Fein“, können auf eine lange Geschichte des Kampfes um Unabhängigkeit zurückblicken. Seit dem Jahr

Republikanische Parteien Irlands, wie etwa die „Sinn Fein“, können auf eine lange Geschichte des Kampfes um Unabhängigkeit zurückblicken. Seit dem Jahr  Auch in Wales gab es kleinere Gruppen nationalistischer Separatisten. Zum einen existierte die „Free Wales Army“, die aus nur

Auch in Wales gab es kleinere Gruppen nationalistischer Separatisten. Zum einen existierte die „Free Wales Army“, die aus nur

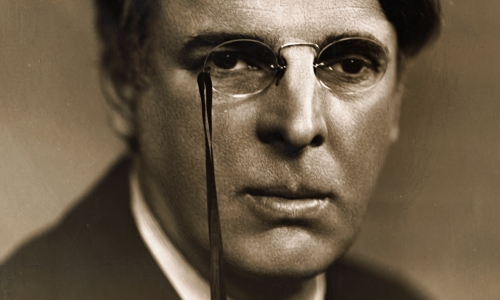

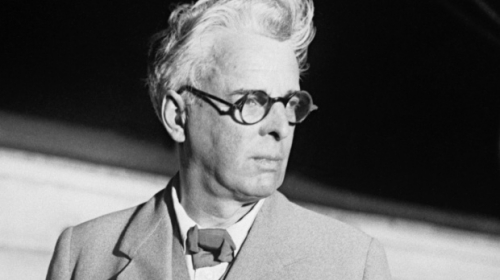

![william-butler-yeats-by-reemerv[162091].jpg](http://euro-synergies.hautetfort.com/media/01/02/2740805010.jpg) The falcon is modern man. The motive force of the falcon’s flight is human desire, pride, spiritedness, and Faustian striving. The spiral structure of the flight is the intelligible measure–the moderation and moralization of human desire and action–imposed by the moral center of our civilization, represented by the falconer, the falcon’s master, our master, which I interpret in Nietzschean terms as the highest values of our culture. The tether that holds us to the center and allows it to impose measure on our flight is the “voice of God,” i.e., the claim of the values of our civilization upon us; the ability of our civilization’s values to move us.

The falcon is modern man. The motive force of the falcon’s flight is human desire, pride, spiritedness, and Faustian striving. The spiral structure of the flight is the intelligible measure–the moderation and moralization of human desire and action–imposed by the moral center of our civilization, represented by the falconer, the falcon’s master, our master, which I interpret in Nietzschean terms as the highest values of our culture. The tether that holds us to the center and allows it to impose measure on our flight is the “voice of God,” i.e., the claim of the values of our civilization upon us; the ability of our civilization’s values to move us. En 1541 Enrique VIII, el mismo que repudió a Catalina de Aragón y creó la Iglesia Anglicana con él al frente, se proclamó como rey de Irlanda. Durante medio siglo los ingleses fueron conquistando el país, con una última gran batalla en Kinsale en 1602, en la que participaron unos 3.500 soldados españoles. Los ingleses vencieron, y en ese momento expulsaron del país a los resistentes irlandeses (muchos fueron a España o a sus territorios europeos). A esos expatriados irlandeses se les llamó “Gansos Salvajes” y los hubo durante todo el siglo y parte del siguiente.

En 1541 Enrique VIII, el mismo que repudió a Catalina de Aragón y creó la Iglesia Anglicana con él al frente, se proclamó como rey de Irlanda. Durante medio siglo los ingleses fueron conquistando el país, con una última gran batalla en Kinsale en 1602, en la que participaron unos 3.500 soldados españoles. Los ingleses vencieron, y en ese momento expulsaron del país a los resistentes irlandeses (muchos fueron a España o a sus territorios europeos). A esos expatriados irlandeses se les llamó “Gansos Salvajes” y los hubo durante todo el siglo y parte del siguiente.

A efectos religiosos, los irlandeses católicos no eran considerados cristianos y no tenían derecho a asistencia religiosa (tampoco la tenían los católicos libres en Inglaterra).

A efectos religiosos, los irlandeses católicos no eran considerados cristianos y no tenían derecho a asistencia religiosa (tampoco la tenían los católicos libres en Inglaterra).

Bruno de Cessole

Ex: http://www.valeursactuelles.com (archives: 2011)