Audio version: To listen in a player, click here [2]. To download the mp3, right-click here [2] and choose “save link as” or “save target as.” To subscribe to the CC podcast RSS feed, click here [3].

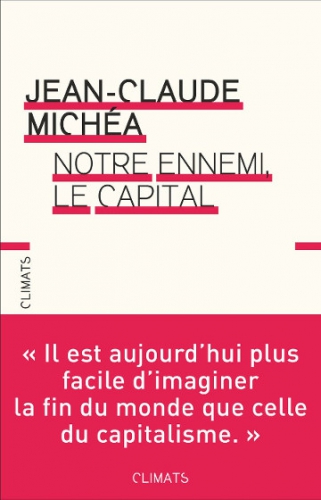

Jean-Claude Michéa

Jean-Claude Michéa

Notre Ennemi, le Capital

Paris: Climats, 2016

Following the election of Donald Trump as the forty-fifth President of the United States, there was a flood of YouTube clips of Clinton supporters, mostly female, throwing tantrums of biblical proportions (the reader will know the sort of thing: he rent his garments and covered himself with sackcloth, etc.) which afforded this writer both amusement and bewilderment. The tearful outbursts of grief were without insight or intelligence of any kind, with one exception.

The exception was a young lady who, after assuring her viewers that she had “stopped crying about it,” turned her wrath on Hillary Clinton. Hillary, it seemed, had enabled “a fascist” to become President, and thereafter unfolded an attack on Clinton from one of the disappointed YouTube amazons, the first of its kind which indicated that a functioning human mind was at work. “We told you,” the lady wailed, “we warned you” (who she meant by “we” was unclear – Bernie supporters, perhaps?) “but you would not listen. We told you: don’t ignore the working man. Don’t ignore the rust belt . . . Hillary Clinton, we overlooked a lot, we overlooked the corruption, we overlooked your links to Goldman Sachs. We warned you. Hilary Clinton, oh, we kept warning you and you wouldn’t listen. You were so sure, so damn arrogant. I’m through with you. You ignored the working man. You ignored the rust belt. Now we’ve got this and it’s your fault! It’s your fault!” Amidst the wailing and petulance, this Clinton voter had made a telling point. Donald Trump won because he had not ignored the rust belt, and his opponent had.

The two seismic upsets of 2016, Brexit and the election of Donald Trump, confounding both polls and media expectations, would not have come about without the common man, the rust belt, the blue-collar worker, Joe Sixpack, slipping harness and voting with “the Right.” Those who had faithfully and reliably followed the Democrat/Labour parties through one election after another, as their parents had done, and in many cases their parents’ parents, voted in opposition to the way the urban professional class voted. These events highlighted the distance between the wealthy liberal elites deciding what constituted progressive and liberal politics, and the political priorities of the indigenous low-paid classes.

The gulf between wealthy urban liberals and an ignored, socially conservative working class is the focus of a new and impassioned political essay by the French sociologist Jean-Claude Michéa called Notre Ennemi, le Capital (Our Enemy: Capital). Jean-Claude Michéa is a socialist, but his analysis of recent events is far from that of the establishment Left-wing’s alarm at the “worrying rise of populism.” His critique of the Left – he does not call himself a Left-winger and indeed makes a critical distinction between Left-wing and socialist – is the hardest a socialist could make, namely that it has abandoned a realistic or meaningful critique of capitalism. “The modern Left,” Michéa claims, “has abandoned any kind of coherent critique of capital.”

The title of Michéa’s book might arguably be Our Enemy: Liberalism, since it is against the liberalism of the affluent that his ire is directed. The word liberal has slightly different connotations in France and the Anglophone world. In France, liberalism is primarily the ideology of faith in free markets with minimal state interference, “those who lose deserve to lose, those who win deserve to win”; and secondly, the expression of an ideology of individual freedom from social constraint. Michéa distinguishes two radically different trends at the heart of socialist/emancipatory movements in history. “In fact, socialism and the Left draw on, and have done from their very beginnings, two logically distinct narratives which only in part overlap.” (p. 47) Put simply, one is the doctrine which seeks the emancipation of the working class, that is to say, the de-alienation of all who work in society, a society organized from the bottom up and based in the organic community, while the other is the Left-wing notion of progress, the ongoing struggle to free individuals from social restraint or responsibility, for minority rights and abstract issues in the name of progress, a demand from the top down. This latter kind of progressive politics, according to Michéa, is not only not opposed to global capitalism, it undermines the very kind of social solidarity which should be expected to oppose global capitalist growth.

Michéa understands the liberal element of parties of progress as being fundamentally anti-democratic, echoing here the distinction made by the French thinker, Alain de Benoist, between democracy and liberalism. Liberalism, obsessed with minorities and what another socialist, George Galloway, famously mocked as “liberal hothouse” issues, is not in principle opposed to the centralization of economic power at all, according to Michéa. Quite the contrary. It is, however, opposed to democracy, that is to say to any entitlement giving a role in the allocation of power to the majority of the people and of any entitlement to a nation to decide its own destiny. In short, liberalism extends economic sovereignty at the expense of political sovereignty.

Michéa’s argument is given credence by the actions of the leaders of the European Union, who are as enthusiastic about deregulating trade as they are unenthusiastic about allowing popular democratic decisions to be made about trade. Liberalism, according to Michéa, is a belief system operating in the cause of capital which supports a minority to oppress a majority. He notes that the very authoritarian and viscerally anti-socialist General Pinochet in Chile pursued an extremely liberal economic policy based on the free market ideas of Friedrich Hayek, who did not much care about democratic liberties so long as rulers got the economy right and followed the economic precepts of Milton Friedman, whose pupils were advisers to the government. Michéa quotes Jean-Claude Juncker (from Le Figaro, January 29, 2015) as stating that “there could be no democratic choice against the European treaties.”

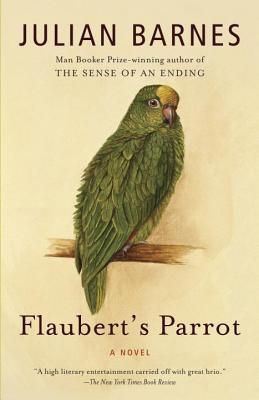

The stream of venom from the rich kids of Britain which erupted, and has not ceased, since June 23, 2016 (the day the EU referendum result was announced) is another casebook example of the liberal loathing of democracy. Liberal outrage is directed at the very notion that major political or economic decisions should be made by a majority of the people, instead of by a minority of wealthy experts, in the first place. A piece that is exemplary in its anti-democratic virulence was penned by the author Julian Barnes and published in the London Review of Books (“People Will Hate Us Again [4]“) in the aftermath of the referendum result in which he described how he and his affluent London dinner-party friends discussed whom they despised most among those who were responsible for the result. (Nearly all remainers were against having a referendum at all.) Barnes’ choice alighted on Nigel Farage. Here is a taste of Julian Barnes:

Farage . . . had been poisoning the well for years, with his fake man-in-pub chaff, his white paranoia and low-to-mid-level racism (isn’t it hard to hear English spoken on a train nowadays?). But of course Nigel can’t really be a racist, can he, because he’s got a German wife? (Except that she’s now chucked him out for the Usual Reasons.) Without Farage’s covert and overt endorsement, the smothered bonfire of xenophobia would not have burst into open flame on 23 June.

Here is what can be understood as a socialist (in Michéa’s sense of the word) comment by the Filipino writer Karlo Mikhail, discussing Barnes’ novel Flaubert’s Parrot on his blog [5]:

Here is what can be understood as a socialist (in Michéa’s sense of the word) comment by the Filipino writer Karlo Mikhail, discussing Barnes’ novel Flaubert’s Parrot on his blog [5]:

That novels like this have sprouted everywhere like mushrooms in recent decades is expressive of a particular socio-political condition. The persistence of a world capitalist system that prioritizes individual profit over collective need goes side by side with the elevation of a hedonistic bourgeois writer to the pedestal as the bearer of individual creativity and artistic beauty.

Interestingly, Jean-Claude Michéa picks out the very same French writer, Gustave Flaubert, as an example of an early liberal’s obsession with minorities (in Flaubert’s case, with gypsies) – a love of minority rights accompanied by disdain for collective identities and aspirations as well as the working classes. Then and now, the liberal does not greatly care for your average Joe, at least not if Joe’s face is white. As Aymeric Patricot wrote in Les Petits Blancs (Little Whites), “They are too poor to interest the Right and too white to interest the Left.”

Michéa appeals to the notion highlighted by George Orwell (whom he greatly admires) of common decency, morality, and social responsibility. But liberalism, notes Michéa, has become the philosophy of skepticism and generalized deconstruction. There is all the difference in the world between a socialism of ordinary folk and a socialism of intellectuals, the latter being nothing more than a championing of causes by a deconstructivist elite. Liberalism is the philosophy of “indifferentiation anchored in the movement of the uniformity of the market” (p. 133). It is a central thesis of the book that liberalism creates individuation in human societies so that the individual is increasingly isolated and social cohesion declines, while paradoxically and running parallel to this development, the economic structures of the world become increasingly uniform, dominated by the power of capital and concentrated in the hands of an increasingly wealthy few.

Michéa stresses that liberalism then becomes obsessed by phobias. A “phobia,” once coined by the National Socialists in occupied Europe to describe the members of the French and Serb resistance movements, he notes wryly, has been recently reappropriated, presumably unknowingly, by opponents of Brexit to describe Brexiters, namely: “europhobe.” Michéa gives a sad but well-known example of the stultifying effects of the “phobia” label: the Rotherham scandal, which erupted in 2014 after the publication of the Jay Report. The report revealed that, from 1997 to 2013, over a thousand girls between ages 11 and 16 had been kidnapped or inveigled by Pakistani gangs to go with them, who were then abused, drugged, plied with alcohol, raped, and in some cases even tortured and forced into prostitution. The town council did nothing about it for over a decade, in spite of being informed about the situation, out of fear of being found guilty of one of the liberal phobias (in this case, “Islamophobia”). For Michéa, this is an example of “common decency” being sacrificed to a liberal prejudice. The protection of the young was seen as less important than risking the allegation of “Islamophobia.” Michéa then quotes Jean-Louis Harouel: the rights of man took precedence over the rights of people.

It is the often-concealed reality of the power of capital which constitutes the fraud of liberal progressive politics, for liberalism as an ideology is increasingly understood as an ideology of the well-to-do. The notion of social justice has shifted from the belief in fair pay and fair opportunities towards hothouse issues which serve to undermine social solidarity. So it is that feminists at the BBC are more concerned about equality of pay between high-earning male and female media executives than a fairer deal for the poor, whether male or female, in society as a whole. This feminist focus on highly-paid women was also evident in Hillary Clinton’s campaign. The Democratic Party seemed more concerned that women in top jobs should receive the same pay as men in comparable jobs than in wishing in any way to close the gap between America’s wealthy and poor. For poor Democrat families living on $1,500 a month, the “glass ceiling’” debate and the “solidarity of sisters” must have seemed very remote from their daily concerns.

For Michéa, all this is no coincidence, since progressive politics, as he sees it, has become a contributory force to the intensification of the power of capital and a vehicle of social disintegration, serving to reinforce the ever-greater concentration of capital in the hands of the few. All prejudices are combated except one: the prejudice of fiscal power. That is to say, nobody should face any barrier other than the barrier of money; and nobody should be excluded from any club, from buying any house, from doing anything he or she wants to do, so long as they have the financial means to do it. If they do not have the financial means to join the club, then their entitlement is withdrawn. Money is everything.

Michéa, like Marx, believes that development by internationalist capitalism acts as a centrifuge to separate the two extremes of those who possess capital from those who do not. Modern society offers increasingly fewer loyalties other than loyalty to the principle of individual competition in a free market. This is why all group adhesion and group loyalty, whether ethnic or geographic or of social class, is undermined or openly attacked by the proponents of progress. In the tradition of socialist conservatives going back to George Orwell, Michéa sees the simplification of language, the dumbing-down of society, and the failure of modern education as part of a pattern.

Michéa, like Marx, believes that development by internationalist capitalism acts as a centrifuge to separate the two extremes of those who possess capital from those who do not. Modern society offers increasingly fewer loyalties other than loyalty to the principle of individual competition in a free market. This is why all group adhesion and group loyalty, whether ethnic or geographic or of social class, is undermined or openly attacked by the proponents of progress. In the tradition of socialist conservatives going back to George Orwell, Michéa sees the simplification of language, the dumbing-down of society, and the failure of modern education as part of a pattern.

An example of this centrifugal tendency as practiced by the European Union is the new guidelines issued by the Central European Bank to national banks, which state that mortgage loans should only be granted to those who can prove that they will be able to service the debt in its entirety within the span of their working life. This astonishing provision, which has received little publicity, is purportedly a measure to prevent a repetition of the American mortgage crisis of 2008, but if Michéa is correct, it is more likely a measure aimed at depriving the working and middle classes of the opportunity to become property owners. It will effectively accelerate the widely-noted tendency in Europe to reduce the power of the middle class, which is being driven upwards or downwards towards the minority of haves or the majority of have-nots. It used to be a Marxist axiom that the middle classes would turn to fascism if deprived of their livelihoods by capitalism, as an alternative to joining the ranks of the dispossessed. Michéa does not directly reiterate this Marxist analysis but he certainly implies it; he has obviously read Marx, and if he is not a Marxist (he leans more toward the writings of Pierre-Joseph Proudhon, the anarchist/socialist critic of Marx), he certainly owes a debt to the social-psychological analyses of the author of Das Kapital.

The capitalist system, to which even the Right-wing critiques of immigration are wed, necessarily strives towards growth, profit, greater efficiency, and expanding markets. All this means an ever-increasing globalization of business. There is an underlying contradiction between on the one hand an appeal to a conservative electorate fearful of job losses and distrustful of immigration, and a pursuit of growth and free trade to maximize profits on the other. Michéa identifies, rightly I believe, mass immigration as a phenomenon backed by the capitalist ruling order to ensure that full employment is never achieved, for the fear of unemployment is the best way to keep wages down. In this respect, pro-immigration anti-fascists act as security guards for high finance, terrorizing any opposition to cheap labor immigration. The contradiction between an appeal to job security and internationalization of capital and free financial markets underlies the promise to impose trade barriers and build walls while at the same time vigorously pursuing and furthering the cause of global trade and financial interdependence.

The liberalization and privatization which became fashionable in the 1980s was a response by the state to the collapse of Soviet Communism and a reaction against Keynesian solutions to stagnation and economic inertia. Michéa favors neither big government of the traditional socialist kind nor a free-market system caught, as he sees it, in a contradiction between a conservative wish to halt the free flow of individuals and its encouragement of the free flow of finance. Instead, Michéa argues for a third kind of social and economic order, one which eschews the centralization and economic top-down principles of Fordism and Leninism on the one hand and the liberal atomization of society as envisaged by progressives on the other. For Michéa, both are alienating and both destroy human communities in service to growth and the concentration of power in a political and economic center. Such centralist notions of ordering society are characterized even in post-war architecture: Michéa cites here the example of the ill-famed Pruitt-Igoe apartment complex [6], demolished in 1976, which was a monument to collectivist folly and liberal “good intentions,” and which can be summed up in the expression of all experts, in this case architectural and engineering experts: “Trust us, we know what’s best for you.”

All abstract revolutionary doctrine, whether economic or political, warns Michéa, sacrifices the people to its power-seeking goals, whether Taylorist (revolutionizing the means of production to maximum efficiency) or Leninist (revolutionizing the control of the means of production to the point of absolute central control). Michéa finishes with a dire warning that what he calls “Silicon Valley liberalism” is the new face of an old ideology whose ideals are growth and progress in a world which cannot bear much more of either, and whose victims are the great mass of human beings, whose natural ethnic, geographical, and social attachments are being destroyed by humanity’s great enemy, capital. This is what Michéa has to say about the condescending pose of modern advanced and affluent liberal thinkers:

For a growing number of people of modest means, whose daily life is hell, the words “Left-wing” mean, if they mean anything at all, at best a defense of public sector workers (which they realize is a protected corral, albeit they may have an idealized view of public employees’ working conditions), and at worst, “Left-wing” means to them the self-justification of journalists, intellectuals, and show-business stars whose imperturbable and permanently patronizing tone has become literally intolerable. (p. 300) (Emphasis Michéa’s)

So now we are back where I started. Clinton ignored the rust belt and Donald Trump won the election. But now Donald Trump seems to be more interested in what he is most skilled at: accumulating capital. Brexit spokesmen seem to be more concerned with proving that Britain’s exit from the EU will open the way for more international trade than stressing that it provides the nation with the ability to close its borders and create a fairer society.

The liberal global model is one model of society, proposed to us today by the champions of globalism and growth; the society where, as John Rawls approvingly put it, individuals can exist side by side with each other while being mutually indifferent. Michéa asks, what is the second element within socialism, distinct from liberal notions of progress and growth, that is a model of society which is socialist but not global, not top-down? It is the socialism of the living indigenous community, of those who, as he puts it, “feel solidarity from the very beginning,” and socialism will be the rebirth, in superior form, of an archaic social type. The choice, in other words, is between a true community of kindred spirits and the barbarism of global centralized power, whose aim is to reduce human society to a mass of hapless individuals easily divided and oppressed.

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

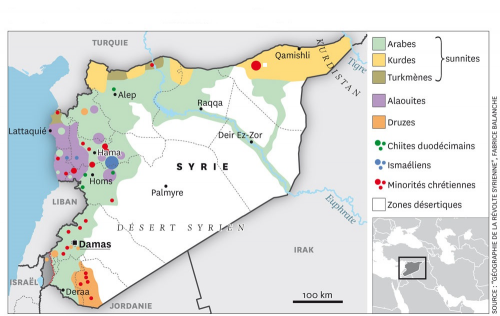

Le mot mentionne ensuite une communauté ethno-religieuse surtout présente en Syrie et au Liban. Abdallah Naaman étudie ce groupe peu connu pour lequel il remplace les lettres o et u par un w : Les Alawites. Histoire mouvementée d’une communauté mystérieuse (Éditions Érick Bonnier, coll. « Encre d’Orient », 359 p., 20 €). L’ouvrage se compose de deux parties inégales. L’une revient longuement sur le déclenchement de la guerre civile syrienne. Démocrate et laïque, l’auteur récuse les supposés rebelles et vrais terroristes islamistes sans pour autant soutenir le gouvernement légitime du président Bachar al-Assad. Très critique envers Israël et l’Arabie Saoudite, il n’hésite pas à qualifier Nicolas Sarkozy de « burlesque », Laurent Fabius de « mouche du coche (p. 200) » et à dénoncer le philosophe botulien Bernard-Henri Lévy qu’il considère comme un « affabulateur (p. 201) » et un « malhonnête homme à la chemise blanche immaculée que d’aucuns traitent d’imposteur intellectuel de la nouvelle philosophie (p. 201) ». Cependant, hors de ces quelques vérités très incorrectes, l’autre partie s’attache à découvrir un peuple mystérieux.

Le mot mentionne ensuite une communauté ethno-religieuse surtout présente en Syrie et au Liban. Abdallah Naaman étudie ce groupe peu connu pour lequel il remplace les lettres o et u par un w : Les Alawites. Histoire mouvementée d’une communauté mystérieuse (Éditions Érick Bonnier, coll. « Encre d’Orient », 359 p., 20 €). L’ouvrage se compose de deux parties inégales. L’une revient longuement sur le déclenchement de la guerre civile syrienne. Démocrate et laïque, l’auteur récuse les supposés rebelles et vrais terroristes islamistes sans pour autant soutenir le gouvernement légitime du président Bachar al-Assad. Très critique envers Israël et l’Arabie Saoudite, il n’hésite pas à qualifier Nicolas Sarkozy de « burlesque », Laurent Fabius de « mouche du coche (p. 200) » et à dénoncer le philosophe botulien Bernard-Henri Lévy qu’il considère comme un « affabulateur (p. 201) » et un « malhonnête homme à la chemise blanche immaculée que d’aucuns traitent d’imposteur intellectuel de la nouvelle philosophie (p. 201) ». Cependant, hors de ces quelques vérités très incorrectes, l’autre partie s’attache à découvrir un peuple mystérieux.

« Il est donc manifeste que la cité n'est pas une communauté de lieu, établie en vue de s'éviter les injustices mutuelles et de permettre les échanges. Certes, ce sont là des conditions qu'il faut nécessairement réaliser si l'on veut qu'une cité existe, mais quand elles sont toutes réalisées, cela ne fait pas une cité, car [une cité] est la communauté de la vie heureuse, c'est-à-dire dont la fin est une vie parfaite et autarcique pour les familles et les lignages » (Politiques, III, 9, 6-15).

« Il est donc manifeste que la cité n'est pas une communauté de lieu, établie en vue de s'éviter les injustices mutuelles et de permettre les échanges. Certes, ce sont là des conditions qu'il faut nécessairement réaliser si l'on veut qu'une cité existe, mais quand elles sont toutes réalisées, cela ne fait pas une cité, car [une cité] est la communauté de la vie heureuse, c'est-à-dire dont la fin est une vie parfaite et autarcique pour les familles et les lignages » (Politiques, III, 9, 6-15).  Notons que la démocratie est, pour Aristote, le gouvernement des plus pauvres, à la fois contre les riches et contre les classes moyennes. Le terme « démocratie » est ainsi pour Aristote quasiment synonyme de démagogie. (Cela peut choquer mais nos élites n’ont-elles pas la même démarche en assimilant toute expression des attentes du peuple en matière de sécurité et de stabilité culturelle à du « populisme », terme aussi diabolisateur que polysémique, comme l’a montré Vincent Coussedière dans Eloge du populisme et Le retour du peuple. An I ?)

Notons que la démocratie est, pour Aristote, le gouvernement des plus pauvres, à la fois contre les riches et contre les classes moyennes. Le terme « démocratie » est ainsi pour Aristote quasiment synonyme de démagogie. (Cela peut choquer mais nos élites n’ont-elles pas la même démarche en assimilant toute expression des attentes du peuple en matière de sécurité et de stabilité culturelle à du « populisme », terme aussi diabolisateur que polysémique, comme l’a montré Vincent Coussedière dans Eloge du populisme et Le retour du peuple. An I ?)  Dans la philosophie d’Aristote, on rencontre plusieurs domaines : la theoria (la spéculation intellectuelle, ou contemplation), l’épistémé (le savoir), la praxis (la pratique) et la poiesis (la production, qui est précisément la production ou la création des œuvres). Nous avons donc quatre domaines. La theoria c’est, à la fois, ce que nous voyons et ce que nous sommes. L’epistémé, c’est ce que nous pouvons connaitre. La poiesis, c’est ce que nous faisons. La praxis, c’est comment nous le faisons.

Dans la philosophie d’Aristote, on rencontre plusieurs domaines : la theoria (la spéculation intellectuelle, ou contemplation), l’épistémé (le savoir), la praxis (la pratique) et la poiesis (la production, qui est précisément la production ou la création des œuvres). Nous avons donc quatre domaines. La theoria c’est, à la fois, ce que nous voyons et ce que nous sommes. L’epistémé, c’est ce que nous pouvons connaitre. La poiesis, c’est ce que nous faisons. La praxis, c’est comment nous le faisons. L’amitié n’est pas le partage des subjectivités comme dans le monde moderne, c’est autre chose, c’est l’en-commun de la vertu. « La parfaite amitié est celle des hommes vertueux et qui sont semblables en vertu. » (Ethique à Nicomaque, VIII, 4, 1156 b, trad. Jules Tricot). Hannah Arendt a bien vu cela. Elle rappelle que l’amitié n’est pas l’intimité mais un discours en commun, un « parler ensemble » (Vies politiques, 1955, Gallimard, 1974). « Pour les Grecs, l’essence de l’amitié consistait dans le discours », écrit Hannah Arendt. Le monde commun créé par le partage de l’amitié implique un sens commun du monde et des choses, comme l’avait vu aussi Jan Patocka (Essais hérétiques sur la philosophie de l’histoire, Verdier, 1981). L’amitié contribue à la solidité de la cité. « Toute association est une parcelle de la cité » (« comme des parcelles de l’association entre des concitoyens »). Le principe de l’amitié n’est pas véritablement différent de celui de la politique. Il implique la justice et la vérité. « Chercher comment il faut se conduire avec un ami, c'est chercher une certaine justice, car en général la justice entière est en rapport avec un être ami » (Ethique à Eudème, VII, 10, 1242 a 20).

L’amitié n’est pas le partage des subjectivités comme dans le monde moderne, c’est autre chose, c’est l’en-commun de la vertu. « La parfaite amitié est celle des hommes vertueux et qui sont semblables en vertu. » (Ethique à Nicomaque, VIII, 4, 1156 b, trad. Jules Tricot). Hannah Arendt a bien vu cela. Elle rappelle que l’amitié n’est pas l’intimité mais un discours en commun, un « parler ensemble » (Vies politiques, 1955, Gallimard, 1974). « Pour les Grecs, l’essence de l’amitié consistait dans le discours », écrit Hannah Arendt. Le monde commun créé par le partage de l’amitié implique un sens commun du monde et des choses, comme l’avait vu aussi Jan Patocka (Essais hérétiques sur la philosophie de l’histoire, Verdier, 1981). L’amitié contribue à la solidité de la cité. « Toute association est une parcelle de la cité » (« comme des parcelles de l’association entre des concitoyens »). Le principe de l’amitié n’est pas véritablement différent de celui de la politique. Il implique la justice et la vérité. « Chercher comment il faut se conduire avec un ami, c'est chercher une certaine justice, car en général la justice entière est en rapport avec un être ami » (Ethique à Eudème, VII, 10, 1242 a 20).

De toute évidence quand des assassinats se répètent, régulièrement, avec toujours les mêmes revendications, quand la menace est désormais partout et que nous sommes tous des victimes en puissance, quand les mesures de sécurité augmentent dans tous les lieux publics, quand les spécialistes vous disent que nous en avons pour plus de vingt ans, est-il encore possible de considérer qu’il s’agit là de simples «faits divers» à répétition qu’il faut, à chaque fois, minimiser? Non. Et pourtant, à chaque fois (comme hier pour Marseille) nos autorités «déplorent» ces attentats, montrent leur «compassion» à l’égard des victimes, indiquent leur «indignation» et dénoncent (comme hier le ministre de l’intérieur) «une attaque odieuse». À chaque fois nos autorités éludent la situation, relativisent l’acte et considèrent l’assassin comme un «fou». Ainsi, hier, le premier ministre, dans un communiqué, s’est-il empressé, de dénoncer le «criminel» et de s’en prendre à «sa folie meurtrière». Non, Monsieur le premier ministre, il n’y a pas de «folie» dans un terrorisme politique qui vise, au nom d’une idéologie islamiste, à lutter contre l’Occident, contre les «infidèles», contre les «impurs», les kouffars que nous sommes tous. Non, Monsieur le premier ministre, à chaque fois on découvre que ces terroristes suivent, d’une manière ou d’une autre, les mots d’ordre de l’Etat islamique avec, souvent, des «cellules-souches» animées par un imam salafiste qui prêche la haine et finit par convaincre certains de ses fidèles qu’il faut tuer «des mécréants». Et comme on pouvait s’en douter, dimanche soir, l’Etat islamique a revendiqué l’attentat. Tout cela renforce l’évidence: certains, ici, nous détestent et feront tout pour détruire ce tissu national qui tient ensemble tout le monde et défend une certaine manière de vivre «à la française».

De toute évidence quand des assassinats se répètent, régulièrement, avec toujours les mêmes revendications, quand la menace est désormais partout et que nous sommes tous des victimes en puissance, quand les mesures de sécurité augmentent dans tous les lieux publics, quand les spécialistes vous disent que nous en avons pour plus de vingt ans, est-il encore possible de considérer qu’il s’agit là de simples «faits divers» à répétition qu’il faut, à chaque fois, minimiser? Non. Et pourtant, à chaque fois (comme hier pour Marseille) nos autorités «déplorent» ces attentats, montrent leur «compassion» à l’égard des victimes, indiquent leur «indignation» et dénoncent (comme hier le ministre de l’intérieur) «une attaque odieuse». À chaque fois nos autorités éludent la situation, relativisent l’acte et considèrent l’assassin comme un «fou». Ainsi, hier, le premier ministre, dans un communiqué, s’est-il empressé, de dénoncer le «criminel» et de s’en prendre à «sa folie meurtrière». Non, Monsieur le premier ministre, il n’y a pas de «folie» dans un terrorisme politique qui vise, au nom d’une idéologie islamiste, à lutter contre l’Occident, contre les «infidèles», contre les «impurs», les kouffars que nous sommes tous. Non, Monsieur le premier ministre, à chaque fois on découvre que ces terroristes suivent, d’une manière ou d’une autre, les mots d’ordre de l’Etat islamique avec, souvent, des «cellules-souches» animées par un imam salafiste qui prêche la haine et finit par convaincre certains de ses fidèles qu’il faut tuer «des mécréants». Et comme on pouvait s’en douter, dimanche soir, l’Etat islamique a revendiqué l’attentat. Tout cela renforce l’évidence: certains, ici, nous détestent et feront tout pour détruire ce tissu national qui tient ensemble tout le monde et défend une certaine manière de vivre «à la française».