The following amplifies the concept of ur-fascism advanced by Umberto Eco [2].

The following amplifies the concept of ur-fascism advanced by Umberto Eco [2].

Ur-fascism is both unity and multiplicity, like life itself: Unity in its embodiment of a single phenomenon and multiplicity because of the diversity and disparity within that phenomenon. “Ur” means primal or primordial: For example, in the form of Heidegger’s “ur-grund” (“primal ground”) or ur-volk (“primeval people”) as well as Goethe’s “ur-phenomenon” (“archetypal pattern”). “Fascism” comes from the Latin, fasces, meaning “bundle”: politically, a people unified. Ur-fascism is the primordial wellspring of all fascist aspirations and movements. This has many roots: Nation, race, ethnicity, heritage, lineage, culture, tradition, language, history, ideals, aims, and values. When a group has emerged, organically and historically, with its own identity, fate, and interests, a people has come into existence.[1]

A people that is integrated genealogically, linguistically, and institutionally at the highest level forms a nation. At higher levels, peoples may be fused together under empires. At lower levels, a people could comprise a family, community, or local state.

Ur-fascism is the primordial foundation of all fascist movements and governments, historically or potentially, that unify peoples at distinct levels. Another term for “people” is the modern English “folk” and the German “Volk.” The former comes from the Old English “folc,” meaning “common people.” “Folk” was diffused through the introduction of the compound “folklore” by antiquarian and demographer, William Thoms. Peoples are distinct and diverse entities, reflected in the history of fascism. Ur-fascism is the primordial origination in archetypal organic patterns, residing in all living things, of a fascistic impulse toward a primeval will to life that has exhibited itself historically in many political, social, and institutional morphologies, ultimately as the differentiation and coagulation of diverse tendencies, traits, and movements.

Ur-fascism metaphysically privileges the people. It accentuates the disparity of interests between peoples, while Marxism emphasizes the disparity of interests between classes. A people is prior to its classes, metaphysically, and its interests take precedence over its classes, ethically.

The founder and leader of the Iron Guard of Romania, Corneliu Codreanu, held that “A people becomes aware of its existence when it becomes aware of its entirety, not only of its component parts and their individual interests.”[2] Ur-fascism grounds the interests of a people or community above that of the individuals and classes that belong to it. As such, it transcends revolutionary socialism and reactionary conservatism. The interests of the community in its entirety take precedence over the interests of individuals and classes that belong to it. Nonetheless, ur-fascism is both revolutionary and conservative: revolutionary in its readiness to overturn structures that are toxic to the life of a people, and once conservative in its insistence on retaining and preserving what is vital to a given people.

On the basis of a view of society as a social organism that is organized, directed, and governed by a vital social organ in the form of the state, Giovanni Gentile maintained that the state “interprets, develops, and potentiates the whole life of people.”[3]

Ur-fascism does not eventuate in the elimination of social classes, hierarchy, or inequality, but rather folds these in to the service of a people as a whole. In a developing plant or animal, cells undergo differentiation and become structurally and functionally suited to certain roles. The Marxist aspiration to end inequality and ultimately dissolve hierarchy is as futile as a revolt among the cells of an organism that is organically suited and required for the weal of the organism as a whole. Equality among an organism’s cells would mean death for the organism. This does not mean that injustice should not be addressed, and inequality and hierarchy are not ends in and of themselves. Neither the aristocratic nor proletarian socialist solution is desirable. Inequality and hierarchy exist to elevate the community as a whole, not any one part of it.

Ur-fascism forms the primeval basis of the fascistic political response and will to life of a people as a whole, rather than any segment within it. If authentic in its embryonic and developmental forms, it will grow to maturity and enable a whole people to persist over time.

A genuine fascist movement or government first exists (a) in embryo, as a nascent political organism or coalescent forces in a government and (b) reaches mature development, around it a variety of explicit aims and goals are embellished and solidified as policies.

In embryonic form, fascist movements and governments originate as phenomena that arise from within a community. According to Umberto Eco, this embryonic form may arise as one, two, or several of the phenomena below, at once or else separately, in orderly or disorderly succession. Ur-fascism is the organic origination of a fascistic movement or government. Just as complex organisms arise from but one, two, or but a few cells, so too does an authentic fascist movement or government. Only one or handful of the phenomena below is necessary, as “it is enough the one of them be present to allow fascism to coagulate around it.” At the national or local level, as nascent movements or existing governments, fascism may initially take the form of, grow from within, or else be signaled and distinguished by:

- Syncretic revival of tradition: reawakening to identity through an integration of disparate traditions, symbols, icons, and ideals among and across past cultures.

- Rejection of modernism: reaffirmation of primordial ideals and political values and a disavowal of the universalism and egalitarianism central to the Enlightenment.

- The necessity of action: realization of the centrality of action as an inherent aspect of a vibrant community, as well as its necessity as a response to decline.

- The necessity of unity: realization of the primacy of primeval truths and basic values, as against perpetual dissent, endless discussion, and disagreement.

- Rejection of difference: affirmation of national, racial, ethnic, cultural, linguistic, or religious identity, and as such, opposition to their erosion and decline.

- Appeal to class interests: repudiation of class conflict and dissention in the community, and an affirmation of the legitimate interests of distinct classes and interests.

- Reality of internal and external threats: drawing attention to internal and external sources of decline and threats to identity, whether ethnic, social, cultural or global in origin.

- Inconstancy in the enemy: the mobilizing and galvanizing reality of distinct threats, often from enemies that fluctuate quickly in strength, tenor, scale, and magnitude.

- Reality of life as struggle: resuscitation and renewal of the community by overcoming decline, while grasping that life is struggle and requires permanent vigilance.

- Populist elitism: elevating the individual as part of his distinct community, promoting its higher over its lower elements, and basing government on the leadership principle.

- A regard for death: realization that death is inevitable, the inculcation of heroic aspiration in everyone, and the mobilizing reality of distant or impending community death.

- Reaffirmation of traditional life: the preservation of traditional families and family roles.

- The primacy of community: recognition of the primacy of community over the individual, the nation over its classes, and the inability of democracy to preserve it.

- The mobilization of language: mobilization of the community is only fully possible through novel uses of language, terms, and phrases, in tandem with symbols and imagery.

The emergence of embryonic fascist movements or nascent fascist governments entails that one, two, or more of the above phenomena have clustered together to form a nucleus, which grows and develops. Ultimately, various policies, plans, and position coagulate around the nucleus. Historically, there were many such policies, plans, and positions. In many cases, they were extensions of the unique vision of the movement or government and the people or nation in question. Whether or not such policies were successful is a different matter, but metaphysically, a fascist movement or government has come to maturity when it has progressed from an embryonic stage in which a nucleus is formed to one in which that nucleus has several different policies clustered around it. These will vary among regimes, but they often include:

- Agrarianism and the preservation of rural life, ethnic identity that is rooted in the unique soil and geographic context of the nation — as in the NSDAP policy of blood and soil.

- Anti-capitalist and anti-consumerist policy that rejects economic materialism.

- Anti-communist policy opposing class conflict and rejecting economic reductionism.

- An anti-liberal domestic policy that rejects individualism as the basis of social life.

- An explicit foreign policy aspiring to autarky and freedom from world finance, and a local policy supporting individual and community self-sufficiency and local adaptedness.

- Policy reflecting support of class collaboration, reconciliation, and legitimate class interests, from basic worker’s rights but also the protection of private property.

- Economic policy grounded in corporatism, syndicalism, mixed economics, and Third Position economics, as was advanced in Italy, Germany, and Falangist Spain.

- Policy reflecting strong support of the young and youth movements, promoting youth that uphold national values and interests, and strengthening the health of the community.

- Environmentalist policy and advocacy of animal welfare, often in conjunction with policy supporting sustainable agriculture, renewable energy, and sound population control.

- Policy advancing irredentist and ethnic nationalist aims, the extension of “living space” (Lebensraum) in German policy or “vital space” (spazio vitale) in Italian policy.

- Familial policy advancing protections for the interests of traditional families, but also promoting the legitimate gender interests for men and women in familial contexts.

- Ethnic and racial policies of fecundism or eugenics, aiming for healthy populations.

- Policy that integrates the interests of the collective with elitist aspirations, synchronizing mass mobilization with the leadership principle, harmonizing individual and society.

- The aestheticizing of social, national, and community life, incorporating social symbols, utilizing rallies, drawing on social ritual and ceremony, and revitalizing traditions.

Eco only discusses the embryonic phase, since his analysis is concerned to explain how fascist movements and nascent fascist governments may emerge. In that sense, his analysis forms a kind of preventative diagnosis, as he aims to show how fascism can be identified before it is allowed to develop into a concrete fascist government.

I have developed his view into a two tiered system, with the embryonic phase representing Eco’s own analysis, and forming the basis for the initial, prenatal phase of fascist development, originating in one, two, or more of the traits I list, each of which is reworded from Eco’s traits; and the developmentally mature stage of fascism, whereby different policies cluster or coagulate around the nucleus that formed in the embryonic stage. Fascism can arise in many ways, and develop many policies.

It is not the case that fascism is a strictly national phenomenon. Instead, it is a way of life that is rooted in organic, synergistic impulse. It can emerge at low societal levels, including the local community (“local fascism”), or else at much higher levels, including the nation.

Moreover, as a response to problems in nations and the decline of communities, fascism has exhibited great historical diversity. Franco’s Spain eschewed expansion, but the pursuit of fresh living space was an important factor in German fascist policy. Italian fascism, however, stressed the pursuit of vital space, which was principally cultural and spiritual, while Mosley’s British Union advocated isolationism and protectionism. And while racial policy was central to German and Norwegian fascism, it was not a central component of Italian Fascism until after 1938, and was never a formulaic component of Portuguese or Spanish fascism. Following World War II, Perón’s Argentina allowed different parties. Catholic conservatism was a significant factor in Spain, while Quisling’s National Gathering looked back to its pagan roots.

Ur-fascism is a family of living worldviews, including past, concrete fascist movements and all possible future movements, and rooting the possibility of fascism in a plurality of different grounds. All movements spring from local conditions and native aspirations.

Understanding ur-fascism as a unique instance of family resemblance also allows us a resource by which to articulate aspects of the decline of European nations and Western Civilization in general. Ur-fascism views different forms of fascism as springing from a common pool of possible sources, and the traits which associate to form the nuclei of fascist movements and regimes have causal relationships with each other. The deconstruction of the West proceeds largely by attacking several of the traits that comprise the core of different fascist worldviews. For example, “antifa,” Leftists, and anti-nationalist advocates attack the traditional family, which is related to if not causally congruent with others traits in the first list. In other words, attacking any of the traits in the list of embryonic traits will likely impinge on several other traits.

Seventy years of consistent deconstruction of the West has largely been predicated on attacks on these features. It follows that any authentic efforts to salvage the nations of the West will require rehabilitating the aims, values, and aspirations of authentic fascism.

In this fashion, my construal of ur-fascism forms a form of prescriptive diagnosis, in contrast to Eco’s preventative diagnosis. If the traits of embryonic fascism bear causal relations of this sort, then nationalists aspiring to save their communities should upheld most of them.

Ur-fascism is a unified family of distinct fascist worldviews, forming a primordial wellspring out of which different fascist movements, historically, have emerged. Its embryonic traits personify primeval biological tendencies that have deep roots in evolutionary history. As an authentic prescription of political mobility, it hearkens back to organic permutations in the history of life that have been exhibited by organismal forms, populations, and lineages. Novel biological forms emerge in the history of life, and exhibit themselves in distinct groups and lineages, arising from underlying mechanisms that work to ensure the persistence of these groups and lineages. The primacy of community over individual is an expression of an integrative tendency in the history of life that is responsible for the diversity of life, and grounds the diversity of fascism.

It is through this conception that we can grasp Eco’s claim that ur-fascism is “primitive”: fascism is a human political system that is deeply rooted in primeval, pervasive biological impulses and patterns that lead to the emergence of distinct communities.

Understood in this way, Eco’s characterization of ur-fascism as “eternal fascism” is transparent: while fascism always manifests in certain places and times, it can always come back again in unexpected guises and different forms; it can never truly, entirely be eradicated.

Notes

1. Wiktionary defines “ur” as proto-, primitive, original. There have been several other explicit uses; Goethe employs “ur-sprung” (“origin”) in his Ueber den Ursprung der Sprache.

2. Stephen Fischer-Galati, Man, State, and Society in East European History (Pall Mall, 1971), quoted on p. 329.

3. Giovanni Gentile and Benito Mussolini, The [3] Doctrine [3] of [3] Fascism [3].

See also the author’s blog: http://ur-fascism.blogspot.com [4]

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

Mais l’autre est parfois en soi, le barbare est parfois « à l’intérieur ». L’autre « c’est surtout tout ce qui est voilé en soi-même » (Mathilde Bernard). Diogène le cynique avait cette requête : il appelait à « ensauvager la vie. Cela voulait dire faire l’expérience d’une sagesse sans la culture et sans la raison. Faire l’expérience d’une sagesse barbare. C’est là introduire le doute sur soi et en soi. C’est prendre le risque de la négation de soi ou de l’envie de mélanger tel le conquérant Alexandre loué en cela par Plutarque (Vie des hommes illustres). Se mélanger pour se dépasser. À l’écart de ce dionysisme nous voyons Ératosthène, géographe et mathématicien; il ne glorifie pas la distinction barbare/non barbare, il ne médit pas non plus son peuple. Pour lui seule compte la vertu, qui est répandue partout, chez les Grecs comme chez les Barbares, tout comme la médiocrité peut concerner des Grecs et des barbares.

Mais l’autre est parfois en soi, le barbare est parfois « à l’intérieur ». L’autre « c’est surtout tout ce qui est voilé en soi-même » (Mathilde Bernard). Diogène le cynique avait cette requête : il appelait à « ensauvager la vie. Cela voulait dire faire l’expérience d’une sagesse sans la culture et sans la raison. Faire l’expérience d’une sagesse barbare. C’est là introduire le doute sur soi et en soi. C’est prendre le risque de la négation de soi ou de l’envie de mélanger tel le conquérant Alexandre loué en cela par Plutarque (Vie des hommes illustres). Se mélanger pour se dépasser. À l’écart de ce dionysisme nous voyons Ératosthène, géographe et mathématicien; il ne glorifie pas la distinction barbare/non barbare, il ne médit pas non plus son peuple. Pour lui seule compte la vertu, qui est répandue partout, chez les Grecs comme chez les Barbares, tout comme la médiocrité peut concerner des Grecs et des barbares.

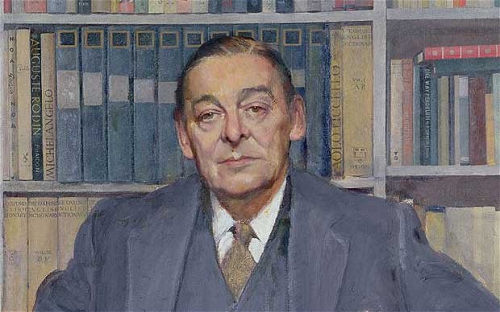

Little Gidding is a real place in Huntingdonshire and is closely associated with the English theologian Nicholas Farrar. Farrar was born in 1592 into a wealthy merchant family and he was intellectually precocious from an early age. After a short career in business and Parliament he left London and in 1625 moved to Little Gidding. At that time Little Gidding consisted of a run-down house and a chapel in a field. Farrar moved there with his mother, brother and sister, their children, and a few other people. About 30 people lived there and formed a close-knit religious community.

Little Gidding is a real place in Huntingdonshire and is closely associated with the English theologian Nicholas Farrar. Farrar was born in 1592 into a wealthy merchant family and he was intellectually precocious from an early age. After a short career in business and Parliament he left London and in 1625 moved to Little Gidding. At that time Little Gidding consisted of a run-down house and a chapel in a field. Farrar moved there with his mother, brother and sister, their children, and a few other people. About 30 people lived there and formed a close-knit religious community. Wilson notes, “It is true that the monastic temper is not a familiar one in the modern world and that, although millions of people may detest the routine of modern life and wish they could escape from it, they would hardly be willing to exchange it for the life of a monk.” But nonetheless, Ferrar had found one particular answer to the outsider’s problem: “he had set his own little corner of the world in order, and lived in that corner as if the rest of the world did not exist.”[1]

Wilson notes, “It is true that the monastic temper is not a familiar one in the modern world and that, although millions of people may detest the routine of modern life and wish they could escape from it, they would hardly be willing to exchange it for the life of a monk.” But nonetheless, Ferrar had found one particular answer to the outsider’s problem: “he had set his own little corner of the world in order, and lived in that corner as if the rest of the world did not exist.”[1]

The following amplifies the concept of ur-fascism

The following amplifies the concept of ur-fascism

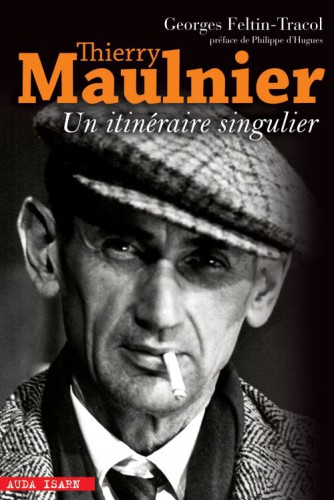

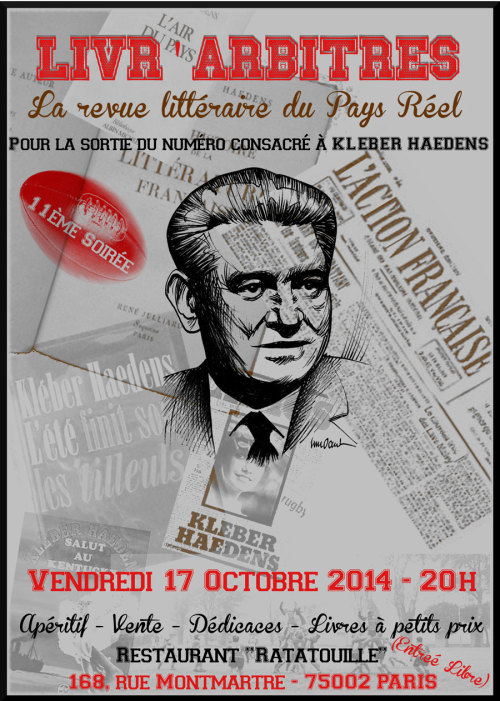

Itinéraire singulier que celui de Jacques Talagrand (1909-1988), mieux connu sous son pseudonyme de L’Action française, Thierry Maulnier. Normalien brillantissime, condisciple de Brasillach, de Bardèche et de Vailland, Maulnier fut l’un des penseurs les plus originaux de sa génération, celle des fameux non conformistes des années 30, avant de devenir l’un des grands critiques dramatiques de l’après-guerre, ainsi qu’un essayiste influent, un chroniqueur fort lu du Figaro, et un académicien assidu. Un sympathique essai tente aujourd’hui de sortir Maulnier d’un injuste purgatoire, moins complet bien sûr que la savante biographie qu’Etienne de Montety a publiée naguère, puisque l’auteur, Georges Feltin-Tracol, a surtout puisé à des sources de seconde main. Moins consensuel aussi, car ce dernier rappelle à juste titre le rôle métapolitique de Thierry Maulnier, actif dans la critique du communisme en un temps où cette idéologie liberticide crétinisait une large part de l’intelligentsia, mais aussi du libéralisme, parfait destructeur des héritages séculaires. Car Maulnier, en lecteur attentif des Classiques, savait que l’homme, dans la cité, doit demeurer la mesure de toutes choses sous peine de se voir avili et asservi comme il le fut sous Staline, comme il l’est dans notre bel aujourd’hui. Feltin-Tracol souligne par exemple le fait que, peu après mai 68, Maulnier s’impliqua aux côtés d’un jeune reître au crâne ras, qui avait tâté de la paille des cachots républicains, dans l’animation d’un Institut d’Etudes occidentales qui influença la toute jeune nouvelle droite. L’activiste en question s’appelait Dominique Venner, futur écrivain et directeur de la Nouvelle Revue d’Histoire…

Itinéraire singulier que celui de Jacques Talagrand (1909-1988), mieux connu sous son pseudonyme de L’Action française, Thierry Maulnier. Normalien brillantissime, condisciple de Brasillach, de Bardèche et de Vailland, Maulnier fut l’un des penseurs les plus originaux de sa génération, celle des fameux non conformistes des années 30, avant de devenir l’un des grands critiques dramatiques de l’après-guerre, ainsi qu’un essayiste influent, un chroniqueur fort lu du Figaro, et un académicien assidu. Un sympathique essai tente aujourd’hui de sortir Maulnier d’un injuste purgatoire, moins complet bien sûr que la savante biographie qu’Etienne de Montety a publiée naguère, puisque l’auteur, Georges Feltin-Tracol, a surtout puisé à des sources de seconde main. Moins consensuel aussi, car ce dernier rappelle à juste titre le rôle métapolitique de Thierry Maulnier, actif dans la critique du communisme en un temps où cette idéologie liberticide crétinisait une large part de l’intelligentsia, mais aussi du libéralisme, parfait destructeur des héritages séculaires. Car Maulnier, en lecteur attentif des Classiques, savait que l’homme, dans la cité, doit demeurer la mesure de toutes choses sous peine de se voir avili et asservi comme il le fut sous Staline, comme il l’est dans notre bel aujourd’hui. Feltin-Tracol souligne par exemple le fait que, peu après mai 68, Maulnier s’impliqua aux côtés d’un jeune reître au crâne ras, qui avait tâté de la paille des cachots républicains, dans l’animation d’un Institut d’Etudes occidentales qui influença la toute jeune nouvelle droite. L’activiste en question s’appelait Dominique Venner, futur écrivain et directeur de la Nouvelle Revue d’Histoire… Penseur lucide et inquiet, sensible au déclin d’une Europe fracturée, Maulnier ne cessa jamais de réfléchir au destin de notre civilisation, notamment en faisant l’éloge de Cette Grèce où nous sommes nés, qui « a donné un sens bimillénaire à l’avenir par la création d’une dialectique du sacré et de l’action, de l’intelligence héroïque et de la fatalité ». Ces simples mots, aussi bien choisis qu’agencés, montrent que Maulnier ne fut jamais chrétien, mais bien stoïcien à l’antique – ce qui le rapproche de la Jeune droite des années 60.

Penseur lucide et inquiet, sensible au déclin d’une Europe fracturée, Maulnier ne cessa jamais de réfléchir au destin de notre civilisation, notamment en faisant l’éloge de Cette Grèce où nous sommes nés, qui « a donné un sens bimillénaire à l’avenir par la création d’une dialectique du sacré et de l’action, de l’intelligence héroïque et de la fatalité ». Ces simples mots, aussi bien choisis qu’agencés, montrent que Maulnier ne fut jamais chrétien, mais bien stoïcien à l’antique – ce qui le rapproche de la Jeune droite des années 60.

Né en 1909, Thierry Maulnier est le pseudonyme de Jacques Talagrand. Issu d’une famille de professeurs, piliers de la III

Né en 1909, Thierry Maulnier est le pseudonyme de Jacques Talagrand. Issu d’une famille de professeurs, piliers de la III

Grâce à la campagne de presse orchestrée de main de maître par Nimier, c’est aussi, avec D’un château l’autre, le temps de la résurrection littéraire de Céline. Morand est désarçonné par les entretiens que Céline accorde à la presse, notamment à L’Express,

Grâce à la campagne de presse orchestrée de main de maître par Nimier, c’est aussi, avec D’un château l’autre, le temps de la résurrection littéraire de Céline. Morand est désarçonné par les entretiens que Céline accorde à la presse, notamment à L’Express,

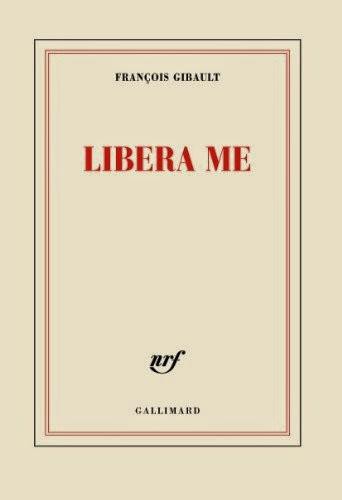

Sous le titre Libera me, il signe un livre testamentaire sous la forme d’un dictionnaire émaillé de remarques acides et spirituelles.

Sous le titre Libera me, il signe un livre testamentaire sous la forme d’un dictionnaire émaillé de remarques acides et spirituelles. El concepto de anarquismo derechista parece paradójico, de hecho, oximorónico, partiendo desde la suposición de que todos los puntos de vista políticos “derechistas” incluyen una evaluación particularmente alta del principio de orden… En efecto, el anarquismo de derecha ocurre sólo en circunstancias excepcionales, cuando la hasta ahora velada afinidad entre el anarquismo y el conservadurismo puede hacerse aparente.

El concepto de anarquismo derechista parece paradójico, de hecho, oximorónico, partiendo desde la suposición de que todos los puntos de vista políticos “derechistas” incluyen una evaluación particularmente alta del principio de orden… En efecto, el anarquismo de derecha ocurre sólo en circunstancias excepcionales, cuando la hasta ahora velada afinidad entre el anarquismo y el conservadurismo puede hacerse aparente.  El rechazo de las jerarquías éticas actuales, la preparación para ser “no apto, en el sentido más profundo de la palabra, para vivir” (Flaubert), revelan puntos comunes de referencia del dandy con el anarquismo; su estudiada frialdad emocional, su orgullo y su aprecio por la sastrería fina y los modales, así como la pretensión de constituir “un nuevo tipo de aristocracia” (Charles Baudelaire), representan la proximidad del dandy a la derecha política. A esto se suma la tendencia de los dandies políticamente inclinados a declarar simpatía a la Revolución Conservadora o a sus precursores, como por ejemplo Maurice Barrès en Francia, Gabriele d’Annunzio en Italia, Stefan George o Arthur Möller van den Bruck en Alemania. El autor japonés Yukio Mishima pertenece a los seguidores tardíos de esta tendencia.

El rechazo de las jerarquías éticas actuales, la preparación para ser “no apto, en el sentido más profundo de la palabra, para vivir” (Flaubert), revelan puntos comunes de referencia del dandy con el anarquismo; su estudiada frialdad emocional, su orgullo y su aprecio por la sastrería fina y los modales, así como la pretensión de constituir “un nuevo tipo de aristocracia” (Charles Baudelaire), representan la proximidad del dandy a la derecha política. A esto se suma la tendencia de los dandies políticamente inclinados a declarar simpatía a la Revolución Conservadora o a sus precursores, como por ejemplo Maurice Barrès en Francia, Gabriele d’Annunzio en Italia, Stefan George o Arthur Möller van den Bruck en Alemania. El autor japonés Yukio Mishima pertenece a los seguidores tardíos de esta tendencia.

ernstzunehmendes Gegengewicht entgegenzustellen, nicht zuletzt in der unübersehbaren Hoffnung, den Fokus der fortwährenden Debatte um Jünger auf einen bislang stiefmütterlich behandelten Schaffensabschnitt des Autors zu lenken.

ernstzunehmendes Gegengewicht entgegenzustellen, nicht zuletzt in der unübersehbaren Hoffnung, den Fokus der fortwährenden Debatte um Jünger auf einen bislang stiefmütterlich behandelten Schaffensabschnitt des Autors zu lenken.

![Cara_Papini[1].jpg](http://euro-synergies.hautetfort.com/media/00/02/4099177256.jpg)

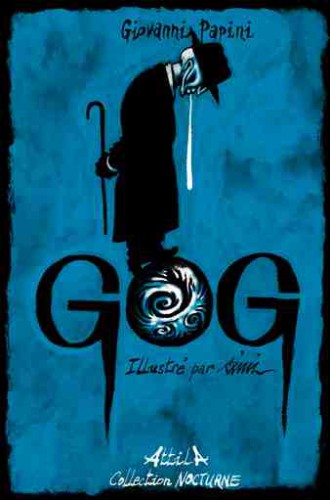

Papini ci mostra un Gog sempre più mosso da umana pietà, che addirittura si commuove e si spaventa, mentre l’umanità pare sempre più demoniaca e priva di senno. Se nel primo romanzo Gog pareva schernire l’umanità, ora pare invece averne pena. Sempre schivo, diffidente e riservato, questo magnate giramondo, spettatore attonito delle vicende umane, non prende mai parte a nessuno dei progetti che nuovamente gli vengono proposti dagli uomini che incontra, folli o straordinari che siano. Il massimo che gli riesce di fare è finanziare, o semplicemente dare promessa di tale intento, a qualche inventore o rivoluzionario in cerca di contributi economici per portare a termine il proprio progetto innovativo. Il romanzo si apre, non per niente, con l’incontro con Ernest O. Lawrence, fisico e Premio Nobel per essere stato l’inventore e il perfezionatore del ciclotrone, il primo acceleratore circolare di particelle atomiche. L’era atomica è quella profetizzata da Papini, e la paura di una guerra nucleare il nuovo spettro che si aggira per il mondo. Ma la profezia più grande contenuta nel romanzo è quella che il nostro Gog/Papini riceve da Lin Youtang – il capitolo è infatti intitolato “Visita a Lin Youtang (o del pericolo giallo)”- di cui vale la pena riportare qualche passaggio:

Papini ci mostra un Gog sempre più mosso da umana pietà, che addirittura si commuove e si spaventa, mentre l’umanità pare sempre più demoniaca e priva di senno. Se nel primo romanzo Gog pareva schernire l’umanità, ora pare invece averne pena. Sempre schivo, diffidente e riservato, questo magnate giramondo, spettatore attonito delle vicende umane, non prende mai parte a nessuno dei progetti che nuovamente gli vengono proposti dagli uomini che incontra, folli o straordinari che siano. Il massimo che gli riesce di fare è finanziare, o semplicemente dare promessa di tale intento, a qualche inventore o rivoluzionario in cerca di contributi economici per portare a termine il proprio progetto innovativo. Il romanzo si apre, non per niente, con l’incontro con Ernest O. Lawrence, fisico e Premio Nobel per essere stato l’inventore e il perfezionatore del ciclotrone, il primo acceleratore circolare di particelle atomiche. L’era atomica è quella profetizzata da Papini, e la paura di una guerra nucleare il nuovo spettro che si aggira per il mondo. Ma la profezia più grande contenuta nel romanzo è quella che il nostro Gog/Papini riceve da Lin Youtang – il capitolo è infatti intitolato “Visita a Lin Youtang (o del pericolo giallo)”- di cui vale la pena riportare qualche passaggio: