Juan Asensio est essayiste et critique littéraire. Il collabore à de nombreuses revues dont Études, L’Atelier du Roman et La Revue des deux Mondes. Depuis 2004, il tient le site Stalker qui se conçoit comme une « dissection du cadavre de la littérature ». Nous nous sommes entretenus avec lui sur son écrivain préféré : Georges Bernanos.

PHILITT : De quand date votre découverte de Georges Bernanos ? Le coup de foudre fut-il immédiat ou vous a-t-il fallu un moment pour appréhender la force de sa langue et le caractère ténébreux de son univers ?

Juan Asensio : C’est lors d’une sortie de classe dans une salle de cinéma que j’ai été pour la première fois confronté à l’œuvre de Georges Bernanos. Sous le soleil de Satan, adapté par Maurice Pialat, venait de sortir sur les écrans. Le film était promis à une longue carrière polémique qui devait connaître son acmé avec le poing crânement brandi par le réalisateur devant le mufle ahuri des imbéciles qui le sifflaient lors de la remise de la Palme d’or du Festival de Cannes. Nous étions alors en 1987, et il me faut ici remercier mon professeur de français de première, Madame Colette Douai, de nous avoir emmenés voir ce film puissant, quoi que nous ayons pensé depuis de sa fidélité après tout relative au texte et surtout, plus grave, à l’esprit du roman de Georges Bernanos. Je ne crois pas abusif de dire que ce fut un choc, bien davantage qu’un coup de foudre, mais un choc d’abord visuel, que je n’avais éprouvé, durant ces mêmes années de scolarité à l’externat Sainte-Marie, à Lyon, que devant Stalker de Tarkovski et Cris et Chuchotements de Bergman. Le premier avait été projeté, si mes souvenirs sont bons, dans une salle de cinéma minuscule se trouvant entre la place des Terreaux et les pentes de la Croix-Rousse, qui n’existe plus depuis de bien longues années. Je revois encore l’affiche du film, qui m’avait intrigué. J’ai regardé le second sur l’écran du ciné-club du collège précédemment nommé. Je me souviens encore du geste d’horreur et de dégoût de ma voisine, deux mains devant la bouche, yeux fermés et tête détournée, durant la projection du film de Bergman, au moment où l’une des héroïnes plonge dans son sexe une lame tranchante. J’ai parlé de choc visuel à propos de l’adaptation réalisée par Maurice Pialat du premier roman de Georges Bernanos. Comment pouvait-il en aller autrement, d’ailleurs, puisqu’il s’agissait d’un film à la lumière chiche, de scènes à la composition non pas sommaire mais épurée tournées en partie à la brune ?

Le choc fut d’abord cinématographique avant d’être littéraire…

Il n’en reste pas moins que ce choc fut renouvelé, réanimé par une nouvelle brûlure, littéraire donc, du moins pour moi, existentielle, cette fois première ou même primaire, bien réelle et non pas transposée d’un support artistique à un autre, par la lecture du roman publié en 1926 par celui que Nimier appela le Grand d’Espagne, et que ce choc fut de nouveau visuel (contrairement à ce que professait Sartre, parlant de la littérature, dans L’imaginaire), convoquant mes sens, donc phénoménologique bien davantage qu’esthétique. Pardonnez-moi d’employer une série de grands mots mais je ne vois pas d’autre façon de décrire l’effet que me fit cette lecture. Si le maquignon démoniaque était capable de voir au fin fond du cœur de l’abbé Donissan, si ce dernier pouvait lire le péché tapi au dernier recès de Mouchette, je voyais, pour ma part, littéralement devant moi, parfois même sans fermer les yeux, les scènes ténébreuses et pourtant sidérantes de vérité que Bernanos avaient peintes, son chevalet planté dans la boue des tranchées de la Grande Guerre, des cratères de laquelle son roman était sorti, comme un animal sauvage sans nom.

Je n’ai pas immédiatement, à l’époque, dévoré les autres romans de Bernanos, et me suis contenté, pour commencer, de lire et de relire le premier roman de cet écrivain qui, comme nul autre hormis Dostoïevski ou Shakespeare (et plus tard, découvrirais-je, Stevenson ou Conrad, Melville ou Lowry), évoquait les tourments les plus secrets de l’âme et, surtout, figurait ce que nous pourrions appeler, sans intention blasphématoire, la présence réelle du diable, présence qui enfin devenait crédible depuis que Baudelaire puis Bloy avaient figé le Père du Mensonge dans le diamant noir de l’Irrévocable, présence cependant imparfaite, labile et grotesque puisqu’elle s’incarnait sous la défroque d’un rusé maquignon et la possession, au sens démonologique du terme, d’une gamine vicieuse, Mouchette. C’est un peu comme si, enfin me suis-je dit puisque je passais comme aujourd’hui mes journées à lire, un univers romanesque original et implacable se découvrait sous mes yeux de lecteur des œuvres du grand Russe, mais aussi de Stevenson ou d’Hawthorne (aucun écrivain français à l’époque, car je lisais les fadaises d’Aragon, de Breton, de Ponge ou, rendez-vous compte, du vieux faune Philippe Sollers, et ne savais rien de Léon Bloy, que je découvrirais quelques années plus tard seulement, dans les rayonnages improbables d’une Fnac de la place Bellecour !), qui tous figurèrent d’une façon ou d’une autre, mais avec moins de crâne éclat que ne l’avait fait ce diable de Bernanos, la geste noire du Démon. Sous le soleil de Satan fut pour moi, je le répète, ce que devrait être toute grande lecture pour un lecteur conséquent, ce qu’avait été la découverte de L’Ange des ténèbres, ce que serait celle, quelques années plus tard, d’Absalon, Absalon !, de la Connaissance de la douleur ou encore de La Persuasion et la Rhétorique. Progressivement, lentement, en prenant bien soin de respecter l’ordre chronologique de parution des œuvres de Georges Bernanos, romans, essais mais aussi correspondance et, parallèlement, tout ce qui avait été écrit sur lui, je m’enfonçais en tout cas dans les terres dangereuses desquelles un Michel Bernanos semble d’ailleurs ne pas être revenu, le regard chargé de visions coruscantes et tentatrices. Quelle Gorgone le fils prodigue de Georges Bernanos, auteur de l’admirable La Montagne morte de la vie ou, moins connu mais tout aussi énigmatique, du texte intitulé Ils ont déchiré Son image a-t-il fixée dans la nuit ?

Depuis cette époque désormais lointaine, je n’ai pas cessé de relire Georges Bernanos, quitte à le délaisser radicalement, mais en l’ayant en somme toujours à l’esprit, même lorsque je découvrais des auteurs n’ayant a priori que peu de rapport avec lui, m’attachant aussi, depuis quelques années, à lire ou relire les auteurs qu’il a lui-même lus, comme Joseph Conrad, Léon Bloy bien sûr, mais encore Ernest Hello, si profondément oublié, et tant d’autres que Bernanos, assez curieusement d’ailleurs, se plaisait à ne mentionner que rarement, comme s’il répugnait à avouer qu’il était, en plus d’un grand romancier, l’un des plus grands romanciers à vrai dire du siècle passé, un excellent lecteur.

Bernanos est un des rares écrivains à briller autant par ses romans que par ses essais polémiques. En quoi est-il difficile de conjuguer les deux ? Connaissez-vous un auteur qui soit son égal de ce point de vue-là ?

Je vais plus loin que vous, car il faut rappeler que c’est à regret que Georges Bernanos a délaissé son œuvre proprement romanesque, ses chers personnages, Chevance, le curé d’Ambricourt, la seconde Mouchette, Chantal de Clergerie, pour se consacrer, vers la fin de sa vie, face à l’urgence apocalyptique qui explosait à ses yeux, à des essais, même si les tout premiers d’entre eux, Jeanne relapse et sainte, La Grande Peur des bien-pensants et Les Grands Cimetières sous la lune sont encore étroitement imbriqués avec les romans, sont comme des espèces de romans, d’ailleurs. Ainsi, l’essai magistral sur Édouard Drumont peut à mon sens parfaitement se lire comme un ample roman sur l’honneur perdu, l’attachement aux valeurs anciennes, la déshumanisation d’un monde autrefois non point admirable mais à tout le moins cohérent, sous l’effet dévastateur de la circulation colossale des masses d’argent, la taylorisation vite devenue folle de la production, y compris celle de cadavres, la destinée solitaire d’un homme qui ne s’est jamais rendu et, comme Georges Bernanos, aura toujours fait face. Mais après l’écriture du dernier chapitre de Monsieur Ouine, de février à mai 1940, plus rien de strictement romanesque, alors que des essais paraîtront encore, non seulement importants mais bien souvent splendides, comme le sont Les Enfants humiliés qui furent publiés en 1949, une année après la mort de l’écrivain, mais qui ont été écrits de septembre 1939 à mai 1940, ou encore La Lettre aux Anglais en 1956 (chez Gallimard, mais dès 1942 à Rio de Janeiro) ou Le Chemin de la Croix-des-Âmes (de nouveau chez Gallimard en 1948, à Rio de Janeiro en 1943-1944). Je constate comme vous que cette position est assez originale, car je ne vois pas, sur cette question d’une répartition non seulement logique mais à vrai dire assez admirable entre des essais polémiques et des romans, d’autre écrivain français qui pourrait être rapproché de Georges Bernanos.

Un autre écrivain moustachu peut-être ?

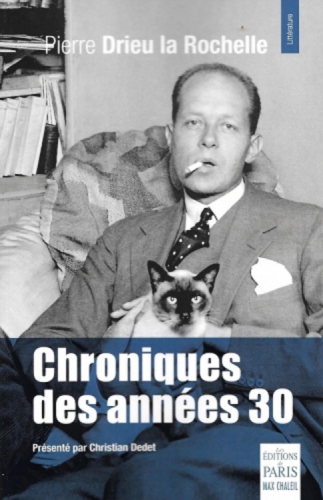

Nous pourrions bien sûr songer à Léon Bloy, que Bernanos découvrit dans les tranchées de la Première Guerre mondiale, mais le Mendiant ingrat a tout de même écrit peu de romans, à la double exception bien connue du Désespéré et de La Femme pauvre qui forment un ensemble. Nous pourrions encore, plus près de nous, évoquer l’immense Pierre Boutang, mais ses romans, y compris celui qui est son texte le plus abouti et difficile, parfois tout bonnement hermétique, Le Purgatoire, ne sont pour lui que des moyens détournés de mener ses recherches poético-politiques de très haut vol. Les mauvaises langues pourraient même parler, à propos de Boutang, de romans à thèse, et il est tout de même assez difficile d’accorder au Secret de René Dorlinde par exemple, que j’évoquerai dans la prochaine livraison de la revue Perspectives libres, la puissance hallucinatoire de Sous le soleil de Satan ! Romancier ou pas, il faudra quoi qu’il en soit finir par accorder la place qui revient à Pierre Boutang en tant que philosophe et, tout bonnement, écrivain et critique littéraire de race, dans ce pays où les fausses gloires pullulent et se reproduisent comme des larves de mouche sur un cadavre, la biographie qui doit bientôt paraître de Stéphane Giocanti, que l’ami Rémi Soulié a lue et trouvé intéressante, permettra sans doute de procéder à cette juste réappropriation d’un génie, bien supérieur à celui de Philippe Muray par exemple, devenu la coqueluche de la droite journalistique, râleur portatif réduit comme une tête de Jivaro à quelques poncifs terriblement commodes et creux. Il n’en reste pas moins qu’il serait je crois quelque peu abusif de considérer Pierre Boutang comme un véritable romancier, ce que Georges Bernanos, lui, fut incontestablement.

Je songe d’ailleurs, en passant, au cas de Philippe Muray, qui pourrait après tout convenir à notre débat, même si ses romans, heureusement rares, sont pratiquement illisibles et surtout sans beaucoup d’intérêt. Quant à son œuvre proprement critique, pléthorique et même bavarde à mesure qu’il a été journalisé, donc avachi et dilué par l’équipe de Causeur, je crois qu’il n’a jamais fait que répéter, d’une manière ou d’une autre et même assez ridiculement lorsqu’il procédait à une « mise en musique » de vers de mirliton houellebecquien, son grand œuvre, Le XIXe siècle à travers les âges bien sûr. Si nous devions examiner plus avant la question que vous me posez, je crois qu’il faudrait délaisser le terrain proprement français, tant labouré et désormais si pauvre que le Goncourt y fait pousser, à grand renfort de pisse journalistique et de lisier éditorial, ses courges transparentes, et aller voir ailleurs, pas très loin, où ont vécu et même vivent encore des écrivains n’ayant pas peur de penser, du côté de l’érudit Claudio Magris par exemple ou du remarquable W. G. Sebald, dont les essais, d’une subtilité et d’une poésie folles, sont comme des enquêtes romanesques qui n’ont pas peur de sonder une réalité derrière laquelle se tapit l’horreur, toujours prête à bondir comme un lion cherchant qui dévorer.

Je songe d’ailleurs, en passant, au cas de Philippe Muray, qui pourrait après tout convenir à notre débat, même si ses romans, heureusement rares, sont pratiquement illisibles et surtout sans beaucoup d’intérêt. Quant à son œuvre proprement critique, pléthorique et même bavarde à mesure qu’il a été journalisé, donc avachi et dilué par l’équipe de Causeur, je crois qu’il n’a jamais fait que répéter, d’une manière ou d’une autre et même assez ridiculement lorsqu’il procédait à une « mise en musique » de vers de mirliton houellebecquien, son grand œuvre, Le XIXe siècle à travers les âges bien sûr. Si nous devions examiner plus avant la question que vous me posez, je crois qu’il faudrait délaisser le terrain proprement français, tant labouré et désormais si pauvre que le Goncourt y fait pousser, à grand renfort de pisse journalistique et de lisier éditorial, ses courges transparentes, et aller voir ailleurs, pas très loin, où ont vécu et même vivent encore des écrivains n’ayant pas peur de penser, du côté de l’érudit Claudio Magris par exemple ou du remarquable W. G. Sebald, dont les essais, d’une subtilité et d’une poésie folles, sont comme des enquêtes romanesques qui n’ont pas peur de sonder une réalité derrière laquelle se tapit l’horreur, toujours prête à bondir comme un lion cherchant qui dévorer.

Que pouvez-vous nous dire de la relation quasiment sentimentale qu’entretenait Bernanos avec Édouard Drumont, un maître qu’il n’a jamais renié ?

Cette relation est aussi trouble que fascinante, et il est frappant de constater que, si Georges Bernanos a pris ses distances avec Charles Maurras, qu’il a accusé de ne pas avoir tenté le coup de force qu’il avait pourtant appelé de ses vœux les plus ardents durant des lustres et, ainsi, s’être moqué prodigieusement des femmes et des hommes qui lui ont fait confiance, il semble en effet ne s’être jamais vraiment éloigné de Drumont qu’il a admiré et, vous avez raison, qu’il a aimé comme un maître et un ami. Pourquoi, d’ailleurs, cet homme profondément fidèle qu’était Georges Bernanos s’en serait-il éloigné ? Il est faux de prétendre que l’on s’éloigne des maîtres, alors même que l’on ne s’éloigne que des petits maîtres. Or Drumont fut un grand maître pour Georges Bernanos. La réponse à ma question n’en est pas moins facile et, je m’empresse de le préciser au risque de devoir subir les foudres de diverses ligues de vertu, entièrement justifiée : c’est en raison de l’antisémitisme non seulement indéniable mais virulent de Drumont, qui devenait tout simplement intenable après la catastrophe de l’extermination des Juifs d’Europe dans les usines à cadavres nazies, que Bernanos aurait pu et, sans nul doute, dû, s’éloigner d’Édouard Drumont. Je suppose, mais rien n’est moins certains, qu’un livre comme La Grande Peur des bien-pensants aurait pu être assez difficilement écrit par le Bernanos de l’après Seconde Guerre mondiale, car, sur la tragédie inconcevable vécue par les Juifs, l’écrivain a eu des mots sans la moindre ambiguïté, contrairement à ce que les ânes, mauvais lecteurs par-dessus le marché, continuent de nous répéter, une fois tous les deux ou trois ans, en répétant comme s’il s’agissait d’un schibboleth ouvrant le domaine du plus furieux antisémitisme le fameux mot de l’auteur sur le fait qu’Hitler a déshonoré l’antisémitisme.

Je me permets de citer un passage de l’article que j’ai consacré sur Stalker à l’essai de Georges Bernanos sur Drumont : « Laissons ici la parole à Drumont, comme tant de fois Bernanos la lui laisse dans son livre : “J’étais guidé uniquement par la haine de l’oppression qui fait le fond de ma nature. L’oppression me rend malade physiquement. Obligé, pendant de longues années, pour subvenir à mes charges de famille, de refouler ce que je pensais j’avais fini par attraper des crampes d’estomac, une anorexie qui me contractait la gorge au moment du repas. Cette douleur a complètement disparu du jour où j’ai pu exprimer librement ma manière de voir, proférer mon verbe (pro, en avant, ferre, porter), ce que je fis dans La France juive et dans La Fin d’un monde” ». Ces lignes sont émouvantes sinon magnifiques. Elles pourraient être appliquées à l’exemple même de Georges Bernanos, tout pressé de délivrer son furieux rêve qui a grossi dans la boue des tranchées de la Première Guerre mondiale, et qui lui aussi, bien plus d’une fois, a dû jouer sa vie sur un raidissement de toute sa volonté, commandant au corps, rétif, de s’élancer dans le paysage défoncé par les obus, et qui lui aussi, nous le savons par de nombreux témoignages, fut bien près, plus d’une fois encore, d’écouter le chant des sirènes du désespoir qui sont sans pitié pour l’imprudent, et qui, lui aussi, ne s’estima jamais quitte avec l’oppression, qui le rendait malade. C’est un échec, l’échec d’un homme complexe (que l’on ne me dise pas que tous les hommes le sont, c’est absolument faux !) qui a attiré Georges Bernanos et, plus qu’un échec, l’aura mystérieuse dont le désespoir enveloppe un destin exceptionnel mais, de plus d’une façon, raté.

L’antisémitisme de Bernanos est donc une question difficile à trancher…

Il n’en reste pas moins que la question de l’antisémitisme de Georges Bernanos, lequel fut bien réel durant les premières années de sa carrière littéraire passées sous l’influence de l’Action française, même s’il ne s’est jamais laissé aller aux débordements de pure haine d’un Drumont ou d’un Léon Daudet, est complexe et a fait l’objet de travaux intéressants, comme celui de Joseph Jurt publié dans les actes du colloque de Cerisy-La-Salle publiés en 1972. Elle est du reste assez bien synthétisée par Philippe Lançon dans un article paru dans Libération en 2008. Certains passages de ce livre suffisent encore à effrayer les petits apeurés vertueux, moins d’ailleurs en raison de cruelles notations à l’égard des Juifs traditionnellement rattachés à la domination de l’Argent que parce que ce livre, de par son incroyable écriture, bondit comme un fauve à la gorge des prudents. C’était du reste bel et bien l’intention de Bernanos qui affirmait dans sa correspondance que cet ouvrage était scandaleux. Ce scandale peut se lire, à présent que les événements politiques auxquels il fait référence nous sont presque aussi lointains que nos premiers ancêtres bipèdes, d’une toute autre façon. Je suis en effet frappé par le désespoir profond qui suinte de ces pages, et ce n’est pas pour rien que, dans cette même correspondance, dans une lettre adressée à son ami Robert Vallery-Radot, Bernanos écrit qu’il se trouve littéralement « entre les bras d’un mort ». L’un des titres auxquels Bernanos a songé pour ce livre n’est-il pas Au bord des prochains charniers, car, à ses yeux, il a « essayé de faire le livre que Drumont lui-même eût fait à l’intention des jeunes Français tombés comme de la lune en ce monde et grandis depuis 1914, c’est-à-dire entre deux cimetières » ?

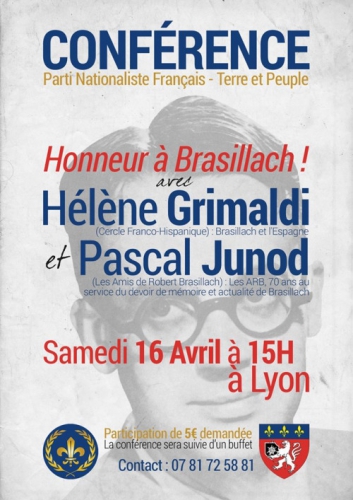

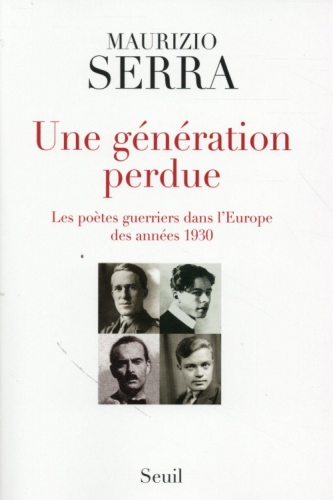

C’est en fin de compte Robert Brasillach qui a raison, lui qui parlait dans Une génération dans l’orage de La Grande Peur des bien-pensants comme d’un livre « torrentiel et chimérique », à condition d’entendre ce dernier qualificatif dans son acception première, qui évoque des êtres n’ayant qu’une existence diminuée, fantomatique, qui vous hante, car ces morts ne voulaient tout simplement, pour la plupart d’entre eux, mourir, comme cela est magnifiquement dit dans Monsieur Ouine. En évoquant Drumont, Bernanos fait d’abord acte de création purement littéraire, car c’est un monde qui n’existe même plus à son époque qu’il fait se lever et sortir de son tombeau qui a même fini de sentir la charogne. Il n’y a plus rien de cette époque, car en écrivant sur Drumont, Bernanos essaie moins de faire revivre les vieilles aspirations et les échecs du Maître qu’un monde qui a été balayé, et qui bientôt pourra même être considéré comme imaginaire par les générations qu’il faut, coûte que coûte selon Bernanos, alerter contre le chaos tel qu’il se prépare. Ce chaos, l’écrivain l’a vu, bête rampante, dans les événements politiques complexes qu’il a analysés dans La Grande Peur des bien-pensants.

L’espérance est une notion centrale dans l’œuvre de Bernanos. Elle est pourtant mise à mal puisque, selon lui, « Satan est le maître de la terre ». La préservation de la « vie intérieure » est-elle pour l’écrivain la condition de possibilité de l’espérance ?

La préservation de la vie intérieure est la condition de la plus stricte survie de l’homme, dans le « monde cassé » dont parle Gabriel Marcel, dans le monde décentré qu’évoque Zissimos Lorentzatos, dans le monde désenchanté analysé par nombre d’auteurs, dans le monde qui fuit Dieu selon Max Picard. Georges Bernanos a ajouté sa voix, tonitruante, spectaculaire, spectrale aussi car elle semble nous avertir depuis une contrée qui n’est plus tout à fait celle que nous connaissons et qui est probablement celle dont parle Ernst Jünger dans ses magnifiques Orages d’acier. Que l’espérance soit, plus qu’une notion, un postulat sans lequel rien n’est possible, une évidence, et cela alors même, comme vous le savez, que Georges Bernanos a connu de terrifiantes crises d’angoisse et de désespoir, n’est pas un hasard, pas plus que ce n’est un hasard s’il a tant aimé son vieux maître Drumont, dont il a génialement disséqué le profond désespoir qui ne l’a jamais pourtant empêché de se dresser face à ce qu’il considérait comme des manifestations inouïes et pourtant banales de la plus féroce injustice.

C’est peut-être la grande force de l’œuvre de Georges Bernanos, que de nous proposer une réserve de vie intérieure, comme un de ces « cœurs de parc » où vivent des espèces protégées, devenues rares, comme les loups splendides qu’il est interdit, du moins en théorie, d’y chasser. Aujourd’hui, c’est un poncif que d’affirmer que toute forte de vie individuelle, fût-elle résiduelle, est menacée, mais des havres de repos existent, comme la Zone dans laquelle le stalker n’a pas peur de conduire celles et ceux qui le désirent. Nous sommes plus que jamais confrontés à la possibilité d’une île, merveilleux titre vous le savez de Michel Houellebecq, mais l’île que nous propose Georges Bernanos n’a fort heureusement rien d’une de ces îles touristiques pelées et arasées par le napalm du tourisme. L’orgueil démoniaque, le désespoir, le mauvais rêve, le mensonge, les yeux brillants de bêtes dont nous avons oublié les noms s’y tapissent, mais aussi la joie, le courage, la fidélité, la bonté, la lucidité, la lumière, l’espérance, l’honneur d’être homme.

Pour Bernanos, le monde moderne est, à proprement parler, « satanique » dans la mesure où il ambitionne de recommencer la création en sens inverse. Bernanos est-il, comme Léon Bloy, un écrivain apocalyptique ?

Oui, tout à fait, et ce n’est pas sans raison que tel commentateur avisé de l’œuvre romanesque de Georges Bernanos a pu affirmer que son dernier roman, Monsieur Ouine, était tout entier prophétique. Un autre, Hans Aaraas, a assuré qu’il s’agissait d’un « poème apocalyptique ». Ce livre ténébreux, d’une folle complexité, résonne du pas des mendiants qui feront trembler la terre et pourrait être considéré comme une espèce de membrane, s’ouvrant parfois mais de toute manière poreuse, entre le monde des morts et celui des vivants. Le fait, d’ailleurs, d’évoquer une dimension prophétique ou même apocalyptique (la seconde découlant logiquement de la première) pose à mon sens des questions fascinantes, qui n’ont été jusqu’à présent guère traitées par la communauté des fâcheux, nos universitaires à courte vue et épais binocles : qu’en est-il de la réalité des affirmations qu’un Bloy ou un Bernanos ont lancées à la face des prudents qui les ont moqués ou se sont détournés d’eux en les traitant d’illuminés frôlant l’apoplexie ? Quels sont les liens entre ce que nous pourrions, à bien des égards, appeler un don de prescience et la tradition de l’inspiration à laquelle plus aucun professeur ne croit, surtout s’il a l’esprit boursouflé de fadaises sur la mort de l’auteur (et celle du Père, et celle de Dieu) ? Comment l’auteur a-t-il procédé pour proférer, au sein même de son texte, ce qui ne pouvait, par essence, qu’excéder la parole, par définition inadaptée, ou, tout au moins, singulièrement limitée ? Ce sont des sentiers dans lesquels nul je crois ne serait prêt à se lancer inconsidérément, pour la simple raison qu’ils longent plus d’une fois les frontières du royaume de la littérature, qui est vaste mais pas infini. Derrière ces frontières, le Verbe, mais tout bon lecteur de Monsieur Ouine a ressenti ce frisson de pure étrangeté, d’angoisse et même d’horreur : il y a dans ce roman lacunaire quelque chose de colossal, d’innommable qui se révèle, parfois, à la surface d’une écriture plus d’une fois menacée de pure et simple dislocation, comme le montrent les admirables Cahiers de Monsieur Ouine publiés par Daniel Pézeril. C’est la marque des plus grandes œuvres que de s’aventurer dans ces zones si peu frayées, où la puissance évocatoire de la langue semble elle-même comme interloquée devant ce qu’elle découvre. Mais Georges Bernanos lui, fidèle à sa plus chère volonté, n’a pas reculé et, comme toujours, a fait face. Ainsi, je crois que l’œuvre de Georges Bernanos est moins derrière que devant nous, à condition bien sûr que les nouvelles générations de lecteurs soient encore capables de parvenir à lire ces textes.

Peut-on dire que le personnage de M. Ouine est une allégorie de l’homme moderne ?

Peut-on dire que le personnage de M. Ouine est une allégorie de l’homme moderne ?

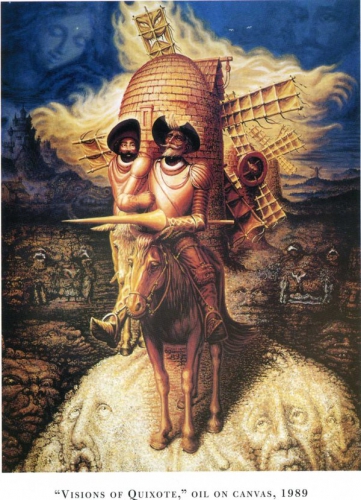

Je me méfie de ce genre de réduction herméneutique qui se termine en -ique, car les lectures allégoriques, symboliques, théologiques ou, les pires de toutes, en tout cas les plus sottes et ridicules, psychanalytiques d’une œuvre littéraire en limitent la portée, et manquent leur objet qui est, tout de même, une écriture de romancier. Parler d’une œuvre romanesque comme d’une allégorie ou même d’un symbole ne vaut en règle générale pas grand-chose et, ma foi, nous pourrions dire de bien d’autres personnages, comme le Marius Ratti de Broch, le Bartleby de Melville ou le Kurtz de Conrad, qu’ils sont des allégories ou même des symboles (je ne confonds bien évidement pas les deux notions) de l’homme moderne. Les lectures allégoriques ou bien symboliques des œuvres romanesques ne donnent jamais de résultats bien probants, car il y a dans ce type de démarche la volonté, parfois clairement avouée, de faire dire à l’œuvre concernée beaucoup plus qu’elle n’a voulu dire, et cela au détriment même de la matérialité de cette œuvre, sa langue, son écriture. Il n’en reste pas moins, cessons de pinailler, que Monsieur Ouine, encore davantage que Monsieur Teste, peut en effet incarner le visage sordide d’une modernité devenue folle, toute pleine de mots tournant à vide, dans « un camp de concentration verbal » selon l’image extraordinaire d’Armand Robin dans La Fausse parole. Comme je l’ai écrit plus d’une fois, le dernier roman de Georges Bernanos n’appartient pas au passé, mais à notre présent, celui d’une paroisse morte (qui fut le premier titre envisagé par l’auteur pour son roman) et, comme ne cessait de me le répéter l’épouse de Jean-Loup Bernanos qui était frappée par sa dimension oraculaire, prophétique, à notre futur.

Vous déplorez, à juste titre, le manque de considération et le relatif oubli qui frappe l’œuvre de Bernanos. La réédition en 2015 de ses œuvres romanesques dans la prestigieuse collection de la Pléiade va-t-elle dans le bon sens ? Les lecteurs sont-ils prêts à découvrir ou redécouvrir Bernanos ?

Pourquoi diable voudriez-vous qu’une multitude de gloses universitaires sans beaucoup d’originalité, voire sans aucune originalité, vendues au prix modique de plus de 130 euros si je ne m’abuse, puissent intéresser un autre public que celui, admirablement consanguin, des universitaires et des étudiants qui gravitent autour d’eux comme un satellite prévisible tourne autour de sa planète favorite, de laquelle il ne souhaitera même pas se désorbiter le jour du Jugement dernier ? Ces derniers seront tout contents de voir cités leurs travaux par des étudiants et d’autres universitaires, qui considéreront comme un impératif épistémologique irrécusable le fait de se débarrasser de la précédente édition fournie par cette même collection de la Pléiade, qu’ils ne manqueront pas de considérer comme étant affreusement datée. Pourtant, c’est bel et bien cette édition préparée par Gaëtan Picon, Michel Estève et Albert Béguin que j’utilise et continuerai d’utiliser, car elle est excellente et, en dépit même de ses défauts, qui est écrite, ce qui n’est à l’évidence pas le cas de la nouvelle édition, comme nous le montre assez rapidement sa vague préface, donnée par un certain Gilles Philippe. Je vais illustrer mon propos par un seul exemple de l’inutilité de ce travail censé être savant (et j’exclus, de ce dernier, l’excellente chronologie de la vie de Bernanos donnée par Gilles Bernanos). Vous connaissez comme moi les toutes premières lignes de Sous le soleil de Satan, où Georges Bernanos évoque Paul-Jean Toulet, un auteur plus qu’intéressant aujourd’hui hélas bien oublié. Dans les notes de la première édition des romans de l’auteur en Pléiade, nous lisons sous la plume de Michel Estève que « l’on peut rapprocher, sur certains points mineurs », La Jeune Fille verte écrite par Toulet du premier roman de Bernanos (cf. p. 1776 de l’édition datant de 1974).

Cette nouvelle édition apporte-t-elle quelque chose de nouveau ?

Prenons (sans l’acheter) le récent travail dû à notre cohorte dûment estampillée ABOC, ou appellation bernanosienne d’origine contrôlée, et lisons la note se rapportant à ce mystérieux passage, cette fois donnée par Pierre Gille : « Plutôt qu’aux célèbres Contrerimes (1921), Bernanos pourrait se référer ici au dernier roman de Paul-Jean Toulet (1867-1920), La Jeune Fille verte ». Bernanos, ajoute Pierre Gille en tirant soigneusement la langue, aura trouvé dans le roman de Toulet « une satire particulièrement vive du monde bourgeois et ecclésiastique d’une petite ville, et des ambiances, comme l’évocation finale, par l’orateur, des “heures divines du crépuscule” » (cf. p. 1190 de la nouvelle édition). Est-ce bien tout ? Oui, c’est tout. Absolument passionnant, non, que de connaître les dates de naissance et de mort d’un auteur et d’apprendre deux ou trois renseignements, que je n’ai pas rapportés ici, à propos de la publication de son dernier roman ! Je tire en tout cas mon chapeau à Pierre Gille, auteur d’un travail intéressant quoique brouillon et surtout inutilement compliqué et non complexe (dans mes souvenirs) sur la question de l’angoisse dans les romans de Bernanos. Je le salue humblement, sans aucune ironie, parce qu’il réussit l’exploit de nous parler d’un glaçon accroché à la monture de sa paire de lunettes alors que, devant lui, se trouve un iceberg de belle taille. Certes, il aura vite fait de m’objecter que la masse réelle d’un iceberg est justement celle qui ne se voit pas, et je serai pour une fois d’accord avec notre universitaire, car, en effet, c’est ne strictement rien avoir vu, tout du moins soupçonné, que d’évoquer La Jeune Fille verte par le minuscule trou de la lorgnette satirique, alors que, les bras m’en tombèrent lorsque je lus ce roman, il est évident que Mouchette doit beaucoup de ses caractéristiques à cette mystérieuse jeune fille verte peinte par Toulet ! Mes yeux, d’habitude bien ouverts lorsque je lis un livre, à la différence de ceux, sans doute fatigués par l’âge, de notre vénérable universitaire et commentateur insignifiant, se dessillèrent pour de bon lorsque je compris que, par le biais du roman de Paul-Jean Toulet, c’est le titre le plus célèbre d’Arthur Machen, Le Grand Dieu Pan (que Toulet avait traduit en français avant la parution de Sous le soleil de Satan) qui affleurait justement dans ce dernier. La preuve de mes dires ? Une simple lecture, mais une vraie lecture se concentrant sur les caractéristiques du démoniaque, telles qu’elles apparaissent dans les trois romans en question (rappelons-les : Le Grand Dieu Pan, La Jeune Fille verte, Sous le soleil de Satan) suffirait pour écrire une belle étude autrement plus passionnante et originale que la note tout juste informative de Pierre Gille.

Je ne puis que renvoyer le lecteur intéressé par cette question à ma propre lecture, qui est prudente mais fournit quelques éléments assez troublants à mes yeux. Pas davantage nos si rigoureux bernanosiens ne semblent s’être avisés du fait que le premier roman de Bernanos pouvait être rapproché de l’un des romans les plus célèbres de Blaise Cendrars, Moravagine, qui a paru en 1926, l’année même où Sous le soleil de Satan a éclaté comme une mine à la face des apôtres zélés du Progrès. Là encore, je renvoie le lecteur à ma longue note sur cette lecture. Du reste, sans trop nous attarder sur ce type de lecture sans âme, ni même beaucoup de rigueur intellectuelle, qui exigerait pour être défait et moqué comme il se doit un travail poussé de lecture comparative, nous pourrions nous borner à constater que la note que Michel Estève a consacrée au dédicataire du premier roman de Georges Bernanos, Robert Vallery-Radot (cf. p. 1777 du volume mentionné plus haut) est beaucoup plus développée que celle de Pierre Gille. Pour quelle raison ? Demandez-le lui, et pensez par la même occasion à demander à celui qui étudia, avec René Guise, l’un des manuscrits du premier roman de Bernanos, pourquoi son travail en Pléiade est si impeccablement professoral, c’est-à-dire à peu près creux ! Il me semble particulièrement regrettable que Gallimard, pour sa collection-phare, n’ait désormais plus recours qu’à des universitaires pur jus, appartenant au petit monde si furieusement consanguin de la recherche (quand il s’agit bel et bien de recherche, et non pas de mandarinat stérile). Si encore ce travail était véritablement érudit, voire, nous pouvons rêver, original, il justifierait son prix exorbitant, mais nous en sommes tellement loin !

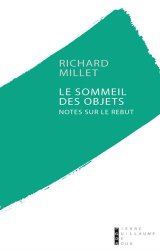

Vous aurez peut-être l’envie, en me lisant, de me faire remarquer que mes propres modestes recherches ne sont pas même mentionnées (à une exception près, mais dans une indication bibliographique purement factuelle, cf. p. 1188, op. cit.) par l’un de nos impeccables et savants lecteurs. En effet, mais elles ne risquaient certainement pas de l’être, en raison du refus catégorique qu’opposa à ma présence, au sein de cette très noble assemblée de professeurs pléiadisés constituée par le regretté Max Milner, Monique Gosselin-Noat, mon éphémère et lamentable directrice de thèse. Je l’évoque, plaisamment vous vous en doutez, dans cette note, et me contenterai d’affirmer que cette personne, invitée à tous les colloques traitant d’auteurs ayant vécu au cours des 20 derniers siècles, et qui ne répète jamais beaucoup plus que des banalités, m’a profondément, à tout jamais même, dégoûté de l’Université, du moins d’un certain type d’Université. De quel ordre est le travail de Monique Gosselin-Noat ? Il s’agit d’un recyclage, pas même inspiré, et ce n’est d’ailleurs absolument pas un hasard si Pierre-Guillaume de Roux, qui publie désormais tous les radotages hystérico-guerriers d’un essayiste aussi profondément nul que Richard Millet, a fait paraître le dernier recyclage de cette spécialiste mondialement célèbre de l’œuvre de Georges Bernanos, dont la thèse sur l’écriture du surnaturel était déjà un fourre-tout assez phénoménal.

Après ce petit détour par les chemins qui ne mènent jamais bien loin de l’Alma mater comprise, à la mode si typiquement française hélas, comme une matrice productrice de gloses asséchantes, j’en reviens à votre question finale : les œuvres fulgurantes de Georges Bernanos, qu’il s’agisse de ses romans, de ses essais ou de ses Dialogues des Carmélites, seront découvertes ou redécouvertes comme elles l’ont été jusqu’à présent, toujours, par la grâce d’une rencontre, d’une réelle présence qui se donnera par bien des truchements, y compris le nôtre, virtuel, que je ne me permettrai pourtant jamais de sous-estimer, après 12 années d’apostolat dans la Zone, celui qui vous permet de m’interroger et, de mon côté, de vous répondre.

Giono, c’est autre chose. Sa correspondance avec Gallimard, qui vient de paraître, nous montre un personnage d’une duplicité peu commune. Dès 1928, Gaston lui propose de devenir son éditeur exclusif dès qu’il sera libre de ses engagements avec Grasset. Grand écrivain mais sacré filou, Giono n’aura de cesse de jouer un double jeu, se flattant d’être « plus malin » que ses éditeurs. Rien à voir avec Céline, âpre au gain, mais qui se targuait d’être « loyal et carré ». Giono, lui, n’hésitait pas à signer en même temps un contrat avec Grasset et un autre avec Gallimard pour ses prochains ouvrages. Chacun des deux éditeurs ignorant naturellement l’existence du traité avec son concurrent. But de la manœuvre : toucher deux mensualités (!). La mèche sera vite éventée. Fureur de Bernard Grasset qui voulut porter plainte pour escroquerie et renvoyer l’auteur indélicat devant un tribunal correctionnel. L’idée de Giono était, en théorie, de réserver ses romans à Gallimard et ses essais à Grasset. L’affaire ira en s’apaisant mais Giono récidivera après la guerre en proposant un livre à La Table ronde, puis un autre encore aux éditions Plon. En termes mesurés, Gaston lui écrit : « Comprenez qu’il est légitime que je sois surpris désagréablement. » Et de lui rappeler, courtoisement mais fermement, ses engagements, ses promesses renouvelées et ses constantes confirmations du droit de préférence des éditions Gallimard. En retour, Giono se lamente : « Avec ce que je dois donner au percepteur, je suis réduit à la misère noire. » Et en profite naturellement pour négocier ses nouveaux contrats à la hausse. Ficelle, il conserve les droits des éditions de luxe et n’entend pas partager avec son éditeur les droits d’adaptation cinématographiques de ses œuvres. Tel était Giono qui, sur ce plan, ne le cédait en rien à Céline. On peut cependant préférer le style goguenard de celui-ci quand il s’adresse à Gaston : « Si j’étais comme vous multi-milliardaire (…), vous ne me verriez point si harcelant… diable ! que vous enverrais loin foutre ! ² ».

Giono, c’est autre chose. Sa correspondance avec Gallimard, qui vient de paraître, nous montre un personnage d’une duplicité peu commune. Dès 1928, Gaston lui propose de devenir son éditeur exclusif dès qu’il sera libre de ses engagements avec Grasset. Grand écrivain mais sacré filou, Giono n’aura de cesse de jouer un double jeu, se flattant d’être « plus malin » que ses éditeurs. Rien à voir avec Céline, âpre au gain, mais qui se targuait d’être « loyal et carré ». Giono, lui, n’hésitait pas à signer en même temps un contrat avec Grasset et un autre avec Gallimard pour ses prochains ouvrages. Chacun des deux éditeurs ignorant naturellement l’existence du traité avec son concurrent. But de la manœuvre : toucher deux mensualités (!). La mèche sera vite éventée. Fureur de Bernard Grasset qui voulut porter plainte pour escroquerie et renvoyer l’auteur indélicat devant un tribunal correctionnel. L’idée de Giono était, en théorie, de réserver ses romans à Gallimard et ses essais à Grasset. L’affaire ira en s’apaisant mais Giono récidivera après la guerre en proposant un livre à La Table ronde, puis un autre encore aux éditions Plon. En termes mesurés, Gaston lui écrit : « Comprenez qu’il est légitime que je sois surpris désagréablement. » Et de lui rappeler, courtoisement mais fermement, ses engagements, ses promesses renouvelées et ses constantes confirmations du droit de préférence des éditions Gallimard. En retour, Giono se lamente : « Avec ce que je dois donner au percepteur, je suis réduit à la misère noire. » Et en profite naturellement pour négocier ses nouveaux contrats à la hausse. Ficelle, il conserve les droits des éditions de luxe et n’entend pas partager avec son éditeur les droits d’adaptation cinématographiques de ses œuvres. Tel était Giono qui, sur ce plan, ne le cédait en rien à Céline. On peut cependant préférer le style goguenard de celui-ci quand il s’adresse à Gaston : « Si j’étais comme vous multi-milliardaire (…), vous ne me verriez point si harcelant… diable ! que vous enverrais loin foutre ! ² ».

Dans son roman «Never say anything – NSA», Michael Lüders nous montre magistralement que nous aussi, nous vivons dans ce monde et que chacun d’entre nous porte une responsabilité envers l’histoire et les générations futures.

Dans son roman «Never say anything – NSA», Michael Lüders nous montre magistralement que nous aussi, nous vivons dans ce monde et que chacun d’entre nous porte une responsabilité envers l’histoire et les générations futures. Michael Lüders, en tant que spécialiste du Proche-Orient présente ces informations spécifiques sous forme de roman. Ces faits n’auraient probablement jamais pu être publiés sous forme d’un travail journalistique. Il profite de ses connaissances en matière de style littéraire, ce qui permet au lecteur de s’identifier avec Sophie. Il ressent comme elle et souffre avec elle, surtout parce que Sophie reste fidèle à sa volonté et à son devoir journalistique de découvrir la vérité. Cela donne de l’espoir, quels que soient les abîmes bien réels relatés dans le roman: tant qu’il y aura des gens comme Sophie et d’autres qui lui viennent en aide dans les pires situations, le monde ne sera pas perdu. Cela nonobstant tous les raffinements des techniques de surveillance et d’espionnage utilisés à poursuivre Sophie pour la faire tomber et s’en débarrasser.

Michael Lüders, en tant que spécialiste du Proche-Orient présente ces informations spécifiques sous forme de roman. Ces faits n’auraient probablement jamais pu être publiés sous forme d’un travail journalistique. Il profite de ses connaissances en matière de style littéraire, ce qui permet au lecteur de s’identifier avec Sophie. Il ressent comme elle et souffre avec elle, surtout parce que Sophie reste fidèle à sa volonté et à son devoir journalistique de découvrir la vérité. Cela donne de l’espoir, quels que soient les abîmes bien réels relatés dans le roman: tant qu’il y aura des gens comme Sophie et d’autres qui lui viennent en aide dans les pires situations, le monde ne sera pas perdu. Cela nonobstant tous les raffinements des techniques de surveillance et d’espionnage utilisés à poursuivre Sophie pour la faire tomber et s’en débarrasser.

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

Auteur de huit recueils poétiques d’inspiration parnassienne, Rodenbach est surtout connu pour ses romans dont le style est aux antipodes du réalisme et du naturalisme. Trois personnages, une intrigue simple, une temporalité romanesque concentrée en un semestre, de novembre à mai : tels sont les ingrédients de Bruges-la-Morte.

Auteur de huit recueils poétiques d’inspiration parnassienne, Rodenbach est surtout connu pour ses romans dont le style est aux antipodes du réalisme et du naturalisme. Trois personnages, une intrigue simple, une temporalité romanesque concentrée en un semestre, de novembre à mai : tels sont les ingrédients de Bruges-la-Morte.

Le préfixe dys de dystopie renvoie au grec dun qui est l’antithèse de la deuxième acception étymologique d’utopie (non pas u mais eu, “lieu du bien”). On fait remonter l’origine du mot “dystopie” tantôt au livre du philosophe tchèque

Le préfixe dys de dystopie renvoie au grec dun qui est l’antithèse de la deuxième acception étymologique d’utopie (non pas u mais eu, “lieu du bien”). On fait remonter l’origine du mot “dystopie” tantôt au livre du philosophe tchèque  C’est en 1920 avec la parution de Nous autres que la fiction dystopique naît véritablement. Cette œuvre phare de l’ingénieur russe Evguéni Ivanovitch Zamiatine donne ainsi ses “lettres de noblesses” au genre. Son ouvrage influença considérablement bon nombre de récits analogues tels que Le Meilleur des mondes d’Huxley et 1984 d’Orwell, publiés respectivement douze et vingt-huit ans plus tard.

C’est en 1920 avec la parution de Nous autres que la fiction dystopique naît véritablement. Cette œuvre phare de l’ingénieur russe Evguéni Ivanovitch Zamiatine donne ainsi ses “lettres de noblesses” au genre. Son ouvrage influença considérablement bon nombre de récits analogues tels que Le Meilleur des mondes d’Huxley et 1984 d’Orwell, publiés respectivement douze et vingt-huit ans plus tard. Ces œuvres voient donc dans l’utopie non pas une chance pour l’humanité, mais un risque de dégénérescence terriblement inhumaine qu’il faut empêcher à tout prix. Le but n’est pas de réaliser des utopies, mais au contraire d’empêcher qu’elles se réalisent. C’est l’avertissement du philosophe existentialiste

Ces œuvres voient donc dans l’utopie non pas une chance pour l’humanité, mais un risque de dégénérescence terriblement inhumaine qu’il faut empêcher à tout prix. Le but n’est pas de réaliser des utopies, mais au contraire d’empêcher qu’elles se réalisent. C’est l’avertissement du philosophe existentialiste

Et c’est vrai qu’il manque deux choses essentielles à un (très) bon roman : finesse et substance, tant dans les personnages (qui manquent vraiment de profondeur) que dans l’avènement du système totalitaire.

Et c’est vrai qu’il manque deux choses essentielles à un (très) bon roman : finesse et substance, tant dans les personnages (qui manquent vraiment de profondeur) que dans l’avènement du système totalitaire.

Il y a une volupté singulière – triste et douce – à évoquer ce dont on ne parle quasiment jamais, à penser des dimensions de la réalité que l’idéalisme ignore. Comme le laissé pour compte, le renié, les objets déchus. Autrement dit le rebut, ce qui gît au grenier, à la cave, dans les tombeaux ou dans un coin de la mémoire. C’est autour de ce que ce rebuté ou ce révolu disent de nous, de l’excessive solitude de l’exclu mais aussi de la construction de notre imaginaire, que gravitent la centaine de courts textes réunis dans Le Sommeil des objets.

Il y a une volupté singulière – triste et douce – à évoquer ce dont on ne parle quasiment jamais, à penser des dimensions de la réalité que l’idéalisme ignore. Comme le laissé pour compte, le renié, les objets déchus. Autrement dit le rebut, ce qui gît au grenier, à la cave, dans les tombeaux ou dans un coin de la mémoire. C’est autour de ce que ce rebuté ou ce révolu disent de nous, de l’excessive solitude de l’exclu mais aussi de la construction de notre imaginaire, que gravitent la centaine de courts textes réunis dans Le Sommeil des objets.

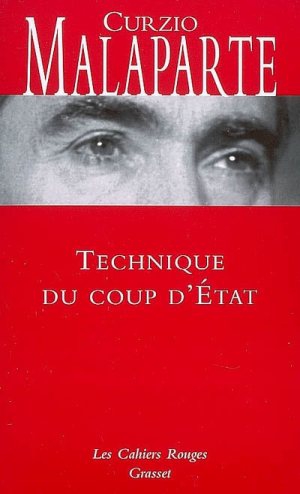

Quando – si era nel 1921 – Malaparte scrisse il dirompente libro “Viva Caporetto!”, poi intitolato “La rivolta dei santi maledetti”, che rileggeva dalle fondamenta la fenomenologia di quella drammatica sconfitta, fece un’operazione di vera rottura ideologica, spingendo la provocazione ben oltre gli steccati della polemica antiborghese, osando toccare il nervo sensibile del superficiale orgoglio nazionale allora egemone in Italia: della rovinosa rotta dell’ottobre 1917 (che il generale Cadorna e molti osservatori attribuirono a un insieme di renitenza e insubordinazione di masse di fanti che in realtà erano abbrutiti dall’inumana vita di trincea) egli fece il simbolo di una rivolta politica in piena regola. Una volta vista non dall’ottica degli alti comandi e dei “bravi cittadini”, ma da quella del fantaccino analfabeta, quella sconfitta, che era un tabù rimosso dall’ipocrita mentalità borghese, diventava un atto politico e la massa dei disfattisti assurgeva a sua volta al rango di soggetto politico. Dando vita, come ha scritto Mario Isnenghi, a qualcosa di inedito e di potenzialmente incendiario, cioè “una interpretazione rivoluzionaria della prima guerra mondiale, della storia delle masse e della psicologia collettiva dentro la guerra”.

Quando – si era nel 1921 – Malaparte scrisse il dirompente libro “Viva Caporetto!”, poi intitolato “La rivolta dei santi maledetti”, che rileggeva dalle fondamenta la fenomenologia di quella drammatica sconfitta, fece un’operazione di vera rottura ideologica, spingendo la provocazione ben oltre gli steccati della polemica antiborghese, osando toccare il nervo sensibile del superficiale orgoglio nazionale allora egemone in Italia: della rovinosa rotta dell’ottobre 1917 (che il generale Cadorna e molti osservatori attribuirono a un insieme di renitenza e insubordinazione di masse di fanti che in realtà erano abbrutiti dall’inumana vita di trincea) egli fece il simbolo di una rivolta politica in piena regola. Una volta vista non dall’ottica degli alti comandi e dei “bravi cittadini”, ma da quella del fantaccino analfabeta, quella sconfitta, che era un tabù rimosso dall’ipocrita mentalità borghese, diventava un atto politico e la massa dei disfattisti assurgeva a sua volta al rango di soggetto politico. Dando vita, come ha scritto Mario Isnenghi, a qualcosa di inedito e di potenzialmente incendiario, cioè “una interpretazione rivoluzionaria della prima guerra mondiale, della storia delle masse e della psicologia collettiva dentro la guerra”. La critica feroce di Malaparte si indirizzava soprattutto verso la morale filistea del borghesismo, quel mondo ipocrita fatto di patriottismo bolso e da operetta, comitati di gentiluomini, patronesse inanellate, tutti gonfi di retorica, con le loro “marcie di umanitarismo e di decadentismo patriottico”, con la loro schizzinosa paura per il popolo vero e i suoi bisogni: questa marmaglia, diceva Malaparte, in fondo odiava i fanti veri, quelli che “non volevano più farsi ammazzare pel loro umanitarismo sportivo”. In questo ritratto di una classe dirigente degenere, obnubilata di retorica e falsi ideali, ognuno riconosce facilmente la classe dirigente degenere di oggi, che è la stessa, radical-chic e impudente, umanitaria per divertimento e per interesse, ieri con i comitati patriottici, oggi con le onlus dedite al business della tratta di carne umana: la morale è la stessa, e lo stesso è l’inganno. Soppesiamo bene quanta verità è contenuta nell’espressione malapartiana di “umanitarismo sportivo” delle oligarchie borghesi, e paragoniamo la casta al potere allora con quella di oggi.

La critica feroce di Malaparte si indirizzava soprattutto verso la morale filistea del borghesismo, quel mondo ipocrita fatto di patriottismo bolso e da operetta, comitati di gentiluomini, patronesse inanellate, tutti gonfi di retorica, con le loro “marcie di umanitarismo e di decadentismo patriottico”, con la loro schizzinosa paura per il popolo vero e i suoi bisogni: questa marmaglia, diceva Malaparte, in fondo odiava i fanti veri, quelli che “non volevano più farsi ammazzare pel loro umanitarismo sportivo”. In questo ritratto di una classe dirigente degenere, obnubilata di retorica e falsi ideali, ognuno riconosce facilmente la classe dirigente degenere di oggi, che è la stessa, radical-chic e impudente, umanitaria per divertimento e per interesse, ieri con i comitati patriottici, oggi con le onlus dedite al business della tratta di carne umana: la morale è la stessa, e lo stesso è l’inganno. Soppesiamo bene quanta verità è contenuta nell’espressione malapartiana di “umanitarismo sportivo” delle oligarchie borghesi, e paragoniamo la casta al potere allora con quella di oggi. Si trattava di difendere un patrimonio che era prezioso per davvero: l’identità del popolo, che non è parola, non è retorica né slogan, ma vita e sostanza di un soggetto antropologico portatore di valori operanti lungo un arco di tempo pressoché incalcolabile. La minaccia avvertita da Malaparte era la violenza assimilatrice del mondo moderno, con la sua universale capacità di appiattire e annullare le diversificazioni culturali. Nel 1922, in uno studio sul sindacalismo italiano rimasto allora famoso, Malaparte lanciava un avvertimento del quale soltanto oggi, dinanzi all’enormità dell’aggressione che stanno subendo non solo gli italiani, ma tutti gli europei, possiamo valutare le tremende implicazioni: “In casa nostra ci è consentito di far soltanto degli innesti, non delle seminagioni. La semenza straniera non può essere buttata sul nostro terreno: la pianta che ne nasce non si confà al nostro clima. Bisogna a un certo punto bruciarla e tagliarne le radici”. L’essersi piegati senza resistenza ai diktat ideologici del liberalcapitalismo d’importazione anglosassone, il non aver ascoltato profezie come questa di Malaparte – che da un secolo in qua si levarono un po’ dappertutto in Europa – sta costando ai popoli europei la finale uscita di scena dalla storia, annegati nella degenerazione morale e nell’azzeramento della politica volute dalle agenzie progressiste cosmopolite.

Si trattava di difendere un patrimonio che era prezioso per davvero: l’identità del popolo, che non è parola, non è retorica né slogan, ma vita e sostanza di un soggetto antropologico portatore di valori operanti lungo un arco di tempo pressoché incalcolabile. La minaccia avvertita da Malaparte era la violenza assimilatrice del mondo moderno, con la sua universale capacità di appiattire e annullare le diversificazioni culturali. Nel 1922, in uno studio sul sindacalismo italiano rimasto allora famoso, Malaparte lanciava un avvertimento del quale soltanto oggi, dinanzi all’enormità dell’aggressione che stanno subendo non solo gli italiani, ma tutti gli europei, possiamo valutare le tremende implicazioni: “In casa nostra ci è consentito di far soltanto degli innesti, non delle seminagioni. La semenza straniera non può essere buttata sul nostro terreno: la pianta che ne nasce non si confà al nostro clima. Bisogna a un certo punto bruciarla e tagliarne le radici”. L’essersi piegati senza resistenza ai diktat ideologici del liberalcapitalismo d’importazione anglosassone, il non aver ascoltato profezie come questa di Malaparte – che da un secolo in qua si levarono un po’ dappertutto in Europa – sta costando ai popoli europei la finale uscita di scena dalla storia, annegati nella degenerazione morale e nell’azzeramento della politica volute dalle agenzie progressiste cosmopolite.

o enfin dans la troisième partie,

o enfin dans la troisième partie,

Le Sauvage est le seul personnage à ne pas avoir subi de conditionnement. Lorsque Bernard Marx le ramène pour le présenter à son père, le chef Tomakin, le Sauvage se révèle incapable de comprendre encore moins de suivre les règles de cette civilisation. On apprend que lorsqu’il a été mis au monde, sa mère ne lui a exprimé aucun amour, n’a eu envers lui aucun geste d’affection. Rien de plus normal. Sa mère Linda, issue de cette société du bonheur permanent, n’a jamais été habituée à manifester le moindre sentiment. Les mots tels que « monogamie », « mère », et « père » étaient supprimés, bannis du vocabulaire de la communauté. Le Sauvage reproche à cette société la perte de relation avec soi qu’elle instaure. Les individus considérés uniquement comme des consommateurs sont obnubilés par la satisfaction de leurs besoins basiques. Ils ne recherchent aucune spiritualité et encore moins d’explications sur ce qui régit le monde qui les entoure…

Le Sauvage est le seul personnage à ne pas avoir subi de conditionnement. Lorsque Bernard Marx le ramène pour le présenter à son père, le chef Tomakin, le Sauvage se révèle incapable de comprendre encore moins de suivre les règles de cette civilisation. On apprend que lorsqu’il a été mis au monde, sa mère ne lui a exprimé aucun amour, n’a eu envers lui aucun geste d’affection. Rien de plus normal. Sa mère Linda, issue de cette société du bonheur permanent, n’a jamais été habituée à manifester le moindre sentiment. Les mots tels que « monogamie », « mère », et « père » étaient supprimés, bannis du vocabulaire de la communauté. Le Sauvage reproche à cette société la perte de relation avec soi qu’elle instaure. Les individus considérés uniquement comme des consommateurs sont obnubilés par la satisfaction de leurs besoins basiques. Ils ne recherchent aucune spiritualité et encore moins d’explications sur ce qui régit le monde qui les entoure…

What don’t we understand?

What don’t we understand? If you the the greatest European power, why are you also nationalists?

If you the the greatest European power, why are you also nationalists?

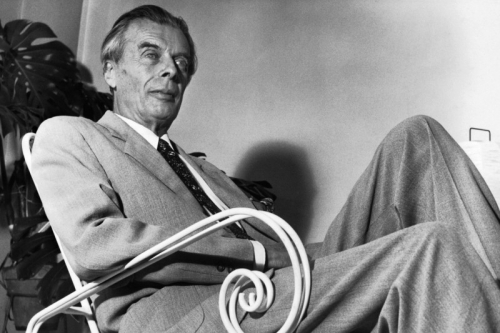

Mais ce qui fait de Jünger un « nationaliste » dans les années 1920, c’est la lecture de Maurice Barrès. Pourquoi ? Avant la Grande Guerre, on était conservateur (mais non révolutionnaire !). Désormais, avec le mythe du sang, chanté par Barrès, on devient un révolutionnaire nationaliste. Le vocable, plutôt nouveau aux débuts de la république de Weimar, indique une radicalisation politique et esthétique qui rompt avec les droites conventionnelles. L’Allemagne, entre 1918 et 1923, est dans la même situation désastreuse que la France après 1871. Le modèle revanchiste barrésien est donc transposable dans l’Allemagne vaincue et humiliée. Ensuite, peu enclin à accepter un travail politique conventionnel, Jünger est séduit, comme Barrès avant lui, par le Général Boulanger, l’homme qui, écrit-il, « ouvre énergiquement la fenêtre, jette dehors les bavards et laisse entrer l’air pur ». Chez Barrès, Ernst Jünger ne retrouve pas seulement les clefs d’une métapolitique de la revanche ou un idéal de purification violente de la vie politique, façon Boulanger. Il y a derrière cette réception de Barrès une dimension mystique, concentrée dans un ouvrage qu’Ernst Jünger avait déjà lu au Lycée : Du sang, de la volupté et de la mort. Il en retient la nécessité d’une ivresse orgiaque, qui ne craint pas le sang, dans toute démarche politique saine, c’est-à-dire dans le contexte de l’époque, de toute démarche politique non libérale, non bourgeoise.

Mais ce qui fait de Jünger un « nationaliste » dans les années 1920, c’est la lecture de Maurice Barrès. Pourquoi ? Avant la Grande Guerre, on était conservateur (mais non révolutionnaire !). Désormais, avec le mythe du sang, chanté par Barrès, on devient un révolutionnaire nationaliste. Le vocable, plutôt nouveau aux débuts de la république de Weimar, indique une radicalisation politique et esthétique qui rompt avec les droites conventionnelles. L’Allemagne, entre 1918 et 1923, est dans la même situation désastreuse que la France après 1871. Le modèle revanchiste barrésien est donc transposable dans l’Allemagne vaincue et humiliée. Ensuite, peu enclin à accepter un travail politique conventionnel, Jünger est séduit, comme Barrès avant lui, par le Général Boulanger, l’homme qui, écrit-il, « ouvre énergiquement la fenêtre, jette dehors les bavards et laisse entrer l’air pur ». Chez Barrès, Ernst Jünger ne retrouve pas seulement les clefs d’une métapolitique de la revanche ou un idéal de purification violente de la vie politique, façon Boulanger. Il y a derrière cette réception de Barrès une dimension mystique, concentrée dans un ouvrage qu’Ernst Jünger avait déjà lu au Lycée : Du sang, de la volupté et de la mort. Il en retient la nécessité d’une ivresse orgiaque, qui ne craint pas le sang, dans toute démarche politique saine, c’est-à-dire dans le contexte de l’époque, de toute démarche politique non libérale, non bourgeoise.  L’abandon des positions tranchées des années 1918-1933 provient certes de l’âge : Ernst Jünger a 50 ans quand le III° Reich s’effondre dans l’horreur. Il vient aussi du choc terrible que fut la mort au combat de son fils Ernstl dans les carrières de marbre de Carrare en Italie. Au moment d’écrire La Paix, Ernst Jünger, amer comme la plupart de ses compatriotes au moment de la défaite, constate : « Après une défaite pareille, on ne se relève pas comme on a pu se relever après Iéna ou Sedan. Une défaite de cette ampleur signifie un tournant dans la vie de tout peuple qui la subit ; dans cette phase de transition non seulement d’innombrables êtres humains disparaissent mais aussi et surtout beaucoup de choses qui nous mouvaient au plus profond de nous-mêmes ». Contrairement aux guerres précédentes, la deuxième guerre mondiale a porté la puissance de destruction des belligérants à son paroxysme, à des dimensions qu’Ernst Jünger qualifie de « cosmiques », surtout après l’atomisation des villes japonaises d’Hiroshima et de Nagasaki. Notre auteur prend conscience que cette démesure destructrice n’est plus appréhendable par les catégories politiques usuelles : de ce fait, nous entrons dans l’ère de la posthistoire. La défaite du III° Reich et la victoire des alliés (anglo-saxons et soviétiques) ont rendu impossible la poursuite des trajectoires historiques héritées du passé. Les moyens techniques de donner la mort en masse, de détruire des villes entières en quelques minutes sinon en quelques secondes prouvent que la civilisation moderne, écrit le biographe Schwilk, « tend irrémédiablement à détruire tout ce qui relève de l’autochtonité, des traditions, des faits de vie organiques ». C’est l’âge posthistorique des « polytechniciens de la puissance » qui commencent partout, et surtout dans l’Europe ravagée, à formater le monde selon leurs critères.

L’abandon des positions tranchées des années 1918-1933 provient certes de l’âge : Ernst Jünger a 50 ans quand le III° Reich s’effondre dans l’horreur. Il vient aussi du choc terrible que fut la mort au combat de son fils Ernstl dans les carrières de marbre de Carrare en Italie. Au moment d’écrire La Paix, Ernst Jünger, amer comme la plupart de ses compatriotes au moment de la défaite, constate : « Après une défaite pareille, on ne se relève pas comme on a pu se relever après Iéna ou Sedan. Une défaite de cette ampleur signifie un tournant dans la vie de tout peuple qui la subit ; dans cette phase de transition non seulement d’innombrables êtres humains disparaissent mais aussi et surtout beaucoup de choses qui nous mouvaient au plus profond de nous-mêmes ». Contrairement aux guerres précédentes, la deuxième guerre mondiale a porté la puissance de destruction des belligérants à son paroxysme, à des dimensions qu’Ernst Jünger qualifie de « cosmiques », surtout après l’atomisation des villes japonaises d’Hiroshima et de Nagasaki. Notre auteur prend conscience que cette démesure destructrice n’est plus appréhendable par les catégories politiques usuelles : de ce fait, nous entrons dans l’ère de la posthistoire. La défaite du III° Reich et la victoire des alliés (anglo-saxons et soviétiques) ont rendu impossible la poursuite des trajectoires historiques héritées du passé. Les moyens techniques de donner la mort en masse, de détruire des villes entières en quelques minutes sinon en quelques secondes prouvent que la civilisation moderne, écrit le biographe Schwilk, « tend irrémédiablement à détruire tout ce qui relève de l’autochtonité, des traditions, des faits de vie organiques ». C’est l’âge posthistorique des « polytechniciens de la puissance » qui commencent partout, et surtout dans l’Europe ravagée, à formater le monde selon leurs critères.

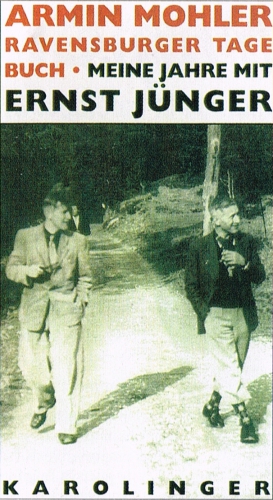

C’est évidemment une rupture non pas tant avec la RC (qui connait trop de facettes pour pouvoir être rejetée entièrement) mais avec ses propres postures nationales-révolutionnaires. Armin Mohler avait écrit le premier article louangeur sur Ernst Jünger dans Weltwoche en 1946. En septembre 1949, il devient le secrétaire d’Ernst Jünger avec pour première tâche de publier en Suisse une partie des journaux de guerre. Armin Mohler avait déjà achevé sa fameuse thèse sur la Révolution conservatrice, sous la supervision du philosophe existentialiste (modéré) et protestant Karl Jaspers, dont il avait retenu une idée cardinale : celle de « période axiale » de l’histoire. Une période axiale fonde les valeurs pérennes d’une civilisation ou d’un grand espace géoreligieux. Pour Armin Mohler, très idéaliste, la RC, en rejetant les idées de 1789, du manchestérisme anglais et de toutes les autres idées libérales, posait les bases, à la suite de l’idée d’amor fati formulée par Nietzsche, d’une nouvelle batterie de valeurs appelées, moyennant les efforts d’élites audacieuses, à régénérer le monde, à lui donner de nouvelles assises solides. Les idées exprimées par Ernst Jünger dans les revues nationales-révolutionnaires des années 20 et dans le Travailleur de 1932 étant les plus « pures », les plus épurées de tout ballast passéiste et de toutes compromissions avec l’un ou l’autre aspect du panlibéralisme du « stupide XIX° siècle » (Daudet !), il fallait qu’elles triomphent dans la posthistoire et qu’elles ramènent les peuples européens dans les dynamismes ressuscités de leur histoire. La pérennité de ces idées fondatrices de nouvelles tables de valeurs balaierait les idées boiteuses des vainqueurs soviétiques et anglo-saxons et dépasserait les idées trop caricaturales des nationaux-socialistes.

C’est évidemment une rupture non pas tant avec la RC (qui connait trop de facettes pour pouvoir être rejetée entièrement) mais avec ses propres postures nationales-révolutionnaires. Armin Mohler avait écrit le premier article louangeur sur Ernst Jünger dans Weltwoche en 1946. En septembre 1949, il devient le secrétaire d’Ernst Jünger avec pour première tâche de publier en Suisse une partie des journaux de guerre. Armin Mohler avait déjà achevé sa fameuse thèse sur la Révolution conservatrice, sous la supervision du philosophe existentialiste (modéré) et protestant Karl Jaspers, dont il avait retenu une idée cardinale : celle de « période axiale » de l’histoire. Une période axiale fonde les valeurs pérennes d’une civilisation ou d’un grand espace géoreligieux. Pour Armin Mohler, très idéaliste, la RC, en rejetant les idées de 1789, du manchestérisme anglais et de toutes les autres idées libérales, posait les bases, à la suite de l’idée d’amor fati formulée par Nietzsche, d’une nouvelle batterie de valeurs appelées, moyennant les efforts d’élites audacieuses, à régénérer le monde, à lui donner de nouvelles assises solides. Les idées exprimées par Ernst Jünger dans les revues nationales-révolutionnaires des années 20 et dans le Travailleur de 1932 étant les plus « pures », les plus épurées de tout ballast passéiste et de toutes compromissions avec l’un ou l’autre aspect du panlibéralisme du « stupide XIX° siècle » (Daudet !), il fallait qu’elles triomphent dans la posthistoire et qu’elles ramènent les peuples européens dans les dynamismes ressuscités de leur histoire. La pérennité de ces idées fondatrices de nouvelles tables de valeurs balaierait les idées boiteuses des vainqueurs soviétiques et anglo-saxons et dépasserait les idées trop caricaturales des nationaux-socialistes.  Armin Mohler veut convaincre le maître de reprendre la lutte. Mais Jünger vient de publier Le Mur du Temps, dont la thèse centrale est que l’ère de l’humanité historique, plongée dans l’histoire et agissant en son sein, est définitivement révolue. Dans La Paix, Ernst Jünger évoquait encore une Europe réunifiée dans la douleur et la réconciliation. Au seuil d’une nouvelle décennie, en 1960, les « empires nationaux » et l’idée d’une Europe unie ne l’enthousiasment plus. Il n’y a plus d’autres perspectives que celle d’un « Etat universel », titre d’un nouvel ouvrage. L’humanité moderne est livrée aux forces matérielles, à l’accélération sans frein de processus qui visent à se saisir de la Terre entière. Cette fluidité planétaire, critiquée aussi par Carl Schmitt, dissout toutes les catégories historiques, toutes les stabilités apaisantes. Les réactiver n’a donc aucune chance d’aboutir à un résultat quelconque. Pour parfaire un programme national-révolutionnaire, comme les frères Jünger en avaient imaginé, il faut que les volontés citoyennes et soldatiques soient libres. Or cette liberté s’est évanouie dans tous les régimes du globe. Elle est remplacée par des instincts obtus, lourds, pareils à ceux qui animent les colonies d’insectes.

Armin Mohler veut convaincre le maître de reprendre la lutte. Mais Jünger vient de publier Le Mur du Temps, dont la thèse centrale est que l’ère de l’humanité historique, plongée dans l’histoire et agissant en son sein, est définitivement révolue. Dans La Paix, Ernst Jünger évoquait encore une Europe réunifiée dans la douleur et la réconciliation. Au seuil d’une nouvelle décennie, en 1960, les « empires nationaux » et l’idée d’une Europe unie ne l’enthousiasment plus. Il n’y a plus d’autres perspectives que celle d’un « Etat universel », titre d’un nouvel ouvrage. L’humanité moderne est livrée aux forces matérielles, à l’accélération sans frein de processus qui visent à se saisir de la Terre entière. Cette fluidité planétaire, critiquée aussi par Carl Schmitt, dissout toutes les catégories historiques, toutes les stabilités apaisantes. Les réactiver n’a donc aucune chance d’aboutir à un résultat quelconque. Pour parfaire un programme national-révolutionnaire, comme les frères Jünger en avaient imaginé, il faut que les volontés citoyennes et soldatiques soient libres. Or cette liberté s’est évanouie dans tous les régimes du globe. Elle est remplacée par des instincts obtus, lourds, pareils à ceux qui animent les colonies d’insectes. ![AM_mohler-j-nger-briefe52a2b554d7f4d_720x600[1]_600x600.jpg](http://euro-synergies.hautetfort.com/media/02/00/3993534085.jpg) La ND française émerge sur la scène politico-culturelle parisienne à la fin des années 60. Ernst Jünger y apparait d’abord sous la forme d’une plaquette du GRECE due à la plume de Marcel Decombis. La RC, plus précisément la thèse de Mohler, est évoquée par Giorgio Locchi dans le n°23 de Nouvelle école. A partir de ces textes éclot une réception diverse et hétéroclite : les textes de guerre pour les amateurs de militaria ; les textes nationaux-révolutionnaires par bribes et morceaux (peu connus et peu traduits !) chez les plus jeunes et les plus nietzschéens ; les journaux chez les anarques silencieux, etc. De Mohler, la ND hérite l’idée d’une alliance planétaire entre l’Europe et les ennemis du duopole de Yalta d’abord, de l’unipolarité américaine ensuite. C’est là un héritage direct des politiques et alliances alternatives suggérées sous la République de Weimar, notamment avec le monde arabo-musulman, la Chine et l’Inde. Par ailleurs, Armin Mohler réhabilite Georges Sorel de manière beaucoup plus explicite et profonde que la ND française. En Allemagne, Mohler reçoit un tiers de la surface de la revue Criticon, dirigée à Munich par le très sage et très regretté Baron Caspar von Schrenck-Notzing. Aujourd’hui, cet héritage mohlerien est assumé par la maison d’édition Antaios et la revue Sezession, dirigées par Götz Kubitschek et son épouse Ellen Kositza.

La ND française émerge sur la scène politico-culturelle parisienne à la fin des années 60. Ernst Jünger y apparait d’abord sous la forme d’une plaquette du GRECE due à la plume de Marcel Decombis. La RC, plus précisément la thèse de Mohler, est évoquée par Giorgio Locchi dans le n°23 de Nouvelle école. A partir de ces textes éclot une réception diverse et hétéroclite : les textes de guerre pour les amateurs de militaria ; les textes nationaux-révolutionnaires par bribes et morceaux (peu connus et peu traduits !) chez les plus jeunes et les plus nietzschéens ; les journaux chez les anarques silencieux, etc. De Mohler, la ND hérite l’idée d’une alliance planétaire entre l’Europe et les ennemis du duopole de Yalta d’abord, de l’unipolarité américaine ensuite. C’est là un héritage direct des politiques et alliances alternatives suggérées sous la République de Weimar, notamment avec le monde arabo-musulman, la Chine et l’Inde. Par ailleurs, Armin Mohler réhabilite Georges Sorel de manière beaucoup plus explicite et profonde que la ND française. En Allemagne, Mohler reçoit un tiers de la surface de la revue Criticon, dirigée à Munich par le très sage et très regretté Baron Caspar von Schrenck-Notzing. Aujourd’hui, cet héritage mohlerien est assumé par la maison d’édition Antaios et la revue Sezession, dirigées par Götz Kubitschek et son épouse Ellen Kositza.

Dans son dernier roman Numéro zéro Umberto Eco décrit la rédaction d'un futur quotidien au début des années 90. On y bidonne tout, des horoscopes aux avis mortuaires, et le journal, aux rédacteurs ringards et aux moyens restreints, et il n'est en réalité pas destiné à paraître. Il servira plutôt d'instrument de chantage à un capitaine d'industrie : il menacera ceux qui lui font obstacle de lancer des révélations scandaleuses ou des campagnes de presse.

Dans son dernier roman Numéro zéro Umberto Eco décrit la rédaction d'un futur quotidien au début des années 90. On y bidonne tout, des horoscopes aux avis mortuaires, et le journal, aux rédacteurs ringards et aux moyens restreints, et il n'est en réalité pas destiné à paraître. Il servira plutôt d'instrument de chantage à un capitaine d'industrie : il menacera ceux qui lui font obstacle de lancer des révélations scandaleuses ou des campagnes de presse.  Dans "Le pendule de Foucault", bien des années avant "Da Vinci Code", Eco imaginait un délirant qui, partant d'éléments faux, construisait une explication de l'Histoire par des manœuvres secrètes, Templiers, groupes ésotériques et tutti quanti. À la fin du livre, l'enquêteur se faisait également tuer, et l'auteur nous révélait à la fois que les constructions mentales sur une histoire occulte, qu'il avait fort ingénieusement illustrée pendant les neuf dixièmes du livre, étaient fausses, mais qu'il y avait aussi des dingues pour les prendre au sérieux. Et tuer en leur nom.

Dans "Le pendule de Foucault", bien des années avant "Da Vinci Code", Eco imaginait un délirant qui, partant d'éléments faux, construisait une explication de l'Histoire par des manœuvres secrètes, Templiers, groupes ésotériques et tutti quanti. À la fin du livre, l'enquêteur se faisait également tuer, et l'auteur nous révélait à la fois que les constructions mentales sur une histoire occulte, qu'il avait fort ingénieusement illustrée pendant les neuf dixièmes du livre, étaient fausses, mais qu'il y avait aussi des dingues pour les prendre au sérieux. Et tuer en leur nom.

Je songe d’ailleurs, en passant,

Je songe d’ailleurs, en passant,