Ernst Jünger und die >Konservative Revolution<.

Überlegungen aus Anlaß der Edition seiner politischen Schriften

Ex: http://www.iaslonline.lmu.de

- Ernst Jünger: Politische Publizistik 1919 bis 1933. Herausgegeben, kommentiert und mit einem Nachwort von Sven Olaf Berggötz.

Stuttgart: Klett-Cotta 2001. 898 S. Ln. € 50,-

ISBN 3-608-93550-9.

Das Bild Jüngers nach 1945

Ein gutes Jahr nach der nationalsozialistischen Machtübernahme, im Mai 1934, schrieb Ernst Jünger im Vorwort zu seiner Aufsatzsammlung Blätter und Steine, es seien "nur solche Arbeiten aufgenommen, denen über einen zeitlichen Ansatz hinaus die Eigenschaft der Dauer innewohnt. [...] Aus dem zu Grunde liegenden Material wurden somit die rein politischen Schriften ausgeschieden; – es verhält sich mit solchen Schriften wie mit den Zeitungen, die spätestens einen Tag nach dem Erscheinen und frühestens in hundert Jahren wieder lesbar sind." 1

Drei Jahre nach seinem Tod sind Jüngers politische Schriften nun zum erstenmal wieder zugänglich. Das Bild, das wir heute von Jünger haben, wäre ein anderes, wenn Jüngers Haltung jener Jahre aus diesen Texten bekannt gewesen wäre. Wo Jünger in der Weimarer Republik politisch stand, war bislang nur in Umrissen erkennbar.

Karl Otto Paetel, der von Jüngers regimekritischer Haltung überzeugen wollte, schrieb 1943 in der Emigrantenzeitschrift Deutsche Blätter, "dass sich Ernst Jünger um die Tagespolitik wirklich nie gekümmert" 2 habe. Paetel hätte es besser wissen müssen: Er kannte Jüngers politische Arbeit gut. Zu Beginn der 30er Jahre war Paetel Hauptschriftleiter der Zeitschrift Die Kommenden, deren Mitherausgeber Jünger war. 3

Als Paetel den Jünger der Marmorklippen (1939) in seiner inneren Emigration vorstellte, hatten Emigranten verschiedener Richtungen Jünger seinen Beitrag zur Zerstörung der Weimarer Republik längst zuerkannt. Siegfried Marck 4 , Hermann Rauschning 5 , Golo Mann 6 und Karl Löwith 7 sahen in Jünger einen Wegbereiter der deutschen Katastrophe. Vermutlich wußten sie von Jüngers tagespolitischem Geschäft in den Jahren 1925 bis 1930. In ihren Analysen waren sie jedoch nicht darauf eingegangen.

Selbst Armin Mohler hatte Jünger zu Lebzeiten nicht überzeugen können, seine politische Publizistik neu zu edieren. Zwei Gesamtausgaben erschienen ohne sie. Unbekannt war sie freilich nicht: In den Bibliographien Jüngers ist sie nahezu vollständig erfaßt. Dennoch sind die zum großen Teil schwer zugänglichen Texte weitgehend unbekannt geblieben.

Künftige Biographen mögen nun entscheiden, ob Jünger sein Denken und Handeln ehrlich oder selbstgerecht verarbeitete. Kurz nach dem Krieg war Jünger vorgeworfen worden, er wolle wie viele bloß Seismograph und Barometer, nicht aber Aktivist gewesen sein. 8 Ein anderer Zugang ist jedoch wichtiger. Die Bedeutung von Jüngers politischer Publizistik liegt weniger in ihrer Teilhabe am Gesamtwerk Jüngers, sondern in ihrem exemplarischen Charakter. Jünger spricht hier als Exemplar seiner Generation – einer Generation, die entscheidende lebensprägende Impulse nicht im Studium, sondern in den Erfahrungen an der Front und in den Wirren der gescheiterten Revolution sowie der katastrophalen wirtschaftlichen Lage bis zur Währungsreform im Dezember 1923 empfing.

Es ist oft betont worden, wie offen in der Spätphase der Weimarer Republik vielen Zeitgenossen die Zukunft schien. Zunächst bietet es sich daher an, Jüngers politische Publizistik zu lesen unter Einklammerung des Wissens um die weitere Entwicklung der deutschen Verhältnisse. Natürlich ist dies nur hypothetisch möglich und hat seine Grenzen. Die Perspektive des Zeitgenossen ist uns verschlossen. Wenn dieses Verfahren hier empfohlen wird, dann aus folgendem Grund: In den Diskussionen des Feuilleton wird der Blick auf Autoren wie Jünger in der Regel auf zwei Perspektiven verengt: Stellung zum Nationalsozialismus und zum Antisemitismus. Selbstverständlich sind dies Fragen, die immer wieder neu gestellt werden müssen. Nur: Jüngers Denken und seine Stellung in den Ideenzirkeln der intellektuellen Rechten wird so im Dunkeln bleiben. Die Kritik, die nur diese Maßstäbe kennt, und die Apologeten vom Schlage Paetels bewirken gemeinsam, daß die Komplexität der Weimarer Rechten, wie sie in so unterschiedlichen Werken wie denjenigen Armin Mohlers und Stefan Breuers erkannt wurde, aus dem Blick gerät.

Überblick

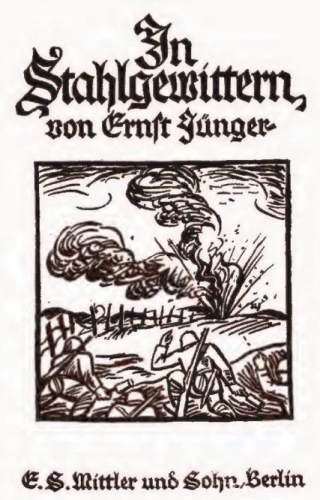

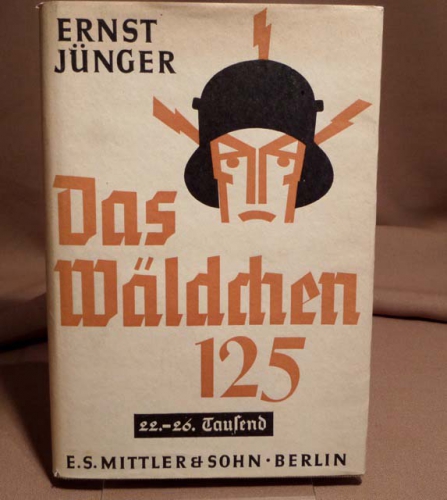

Der nun vorliegende Band Politische Publizistik 1919-1933 versammelt nicht nur die politische Publizistik jener Jahre, sondern auch eine Fülle anderer Texte, die diesem Genre nicht zugeordnet werden können. Insgesamt sind es 144 Texte. Die Vorworte zu verschiedenen Auflagen von In Stahlgewittern, von Der Kampf als inneres Erlebnis , von Feuer und Blut und Das Wäldchen 125, die alle nicht in die Werkausgaben aufgenommen wurden, kommen ebenso zum Abdruck wie einige Rezensionen, die zwischen 1929 und 1933 entstanden.

Man könnte einwenden, daß der Band insgesamt ein heterogenes Sammelsurium von Texten der Jahre 1920–33 sei, und so gesehen der Titel der Ausgabe in die Irre führe. Auf der anderen Seite: Die Grenze zwischen politischen und unpolitischen Arbeiten ist bei einem Autor wie Jünger schwer zu ziehen. Und: die nun vorliegende Ausgabe hat einen eminenten Vorzug. Jüngers mitunter äußerst schwer zugängliche Arbeiten aus der Zeit der Weimarer Republik liegen nun – soweit sie bekannt sind – zum erstenmal vollständig vor. 9

Eingeleitet wird der Band von einigen kleineren Arbeiten, die ebenfalls nicht im strengen Sinn politisch zu nennen sind. Zwischen 1920 – dem Jahr, in dem In Stahlgewittern erschien – und 1923 schrieb Jünger einige kürzere Aufsätze, die Fragen der modernen Kriegsführung behandeln, im Militär-Wochenblatt. Zeitschrift für die deutsche Wehrmacht.

Am 31. August 1923 – in der Hochphase der Inflation – schied Jünger aus der Reichswehr aus. Im Wintersemester immatrikulierte er sich in Leipzig als stud. rer. nat. Jünger war damals 28 Jahre alt. In einer Lebensphase, in der wesentliche Prägungen bereits abgeschlossen sind, begann er zu studieren. Jünger hörte Zoologie bei dem Philosophen und Biologen Hans Driesch, dem führenden Sprecher des Neovitalismus, und Philosophie bei Felix Krüger und dessen Assistenten Hugo Fischer. Auch dürfte er Hans Freyer, der seit 1925 in Leipzig Professor war, an der Universität kennengelernt haben.

Seine erste politische Arbeit schrieb Jünger kurz nach seinem Ausscheiden aus der Reichswehr für den Völkischen Beobachter – einer von zwei Beiträgen in dieser Zeitung, der zweite erschien 1927. Im September 1923, knapp zwei Monate vor Hitlers Münchner Putschversuch, erscheint der Aufsatz mit dem Titel Revolution und Idee. Schon hier finden sich Motive, die sich durch Jüngers politisches Argumentieren der folgenden Jahre ziehen werden: die Bedeutung der Idee und die Unaufhaltsamkeit einer künftigen Revolution. Die gescheiterte Revolution von 1918, schrieb Jünger, "kein Schauspiel der Wiedergeburt, sondern das eines Schwarmes von Schmeißfliegen, der sich auf einen Leichnam stürzte, um von ihm zu zehren", war nicht in der Lage eine Idee zu verwirklichen. Sie mußte daher notwendig scheitern: "Für diese Tatsachen, die späteren Geschlechtern unglaublich vorkommen werden, gibt es nur eine Erklärung: der alte Staat hatte jenen rücksichtslosen Willen zum Leben verloren, der in solchen Zeiten unbedingt notwendig ist" (35). Es gilt daher einzusehen, daß die versäumte Revolution nachgeholt werden muß:

Die echte Revolution hat noch gar nicht stattgefunden, sie marschiert unaufhaltsam heran. Sie ist keine Reaktion, sondern eine wirkliche Revolution mit all ihren Kennzeichen und Äußerungen, ihre Idee ist die völkische, zu bisher nicht gekannter Schärfe geschliffen, ihr Banner ist das Hakenkreuz, ihre Ausdrucksform die Konzentration des Willens in einem einzigen Punkt – die Diktatur! Sie wird ersetzen das Wort durch die Tat, die Tinte durch das Blut, die Phrase durch das Opfer, die Feder durch das Schwert. (36)

1922 erscheint Der Kampf als inneres Erlebnis und die zweite Auflage von In Stahlgewittern, 1923 im Hannoverschen Kurier in 16 Folgen die Erzählung Sturm, 1924 und 1925 Das Wäldchen 125. Eine Chronik aus den Grabenkämpfen und Feuer und Blut. Ein kleiner Ausschnitt aus einer großen Schlacht. Die erste Phase seines Werkes, in dem Jünger seine Fronterlebnisse verarbeitete, ist damit abgeschlossen. Das Jahr 1925 bedeutet für Jünger in vielerlei Hinsicht eine Zäsur. Zehn Jahre lang – bis zu den Afrikanischen Spielen von 1936 – wird Jünger keine Erzählungen und Romane veröffentlichen.

1922 erscheint Der Kampf als inneres Erlebnis und die zweite Auflage von In Stahlgewittern, 1923 im Hannoverschen Kurier in 16 Folgen die Erzählung Sturm, 1924 und 1925 Das Wäldchen 125. Eine Chronik aus den Grabenkämpfen und Feuer und Blut. Ein kleiner Ausschnitt aus einer großen Schlacht. Die erste Phase seines Werkes, in dem Jünger seine Fronterlebnisse verarbeitete, ist damit abgeschlossen. Das Jahr 1925 bedeutet für Jünger in vielerlei Hinsicht eine Zäsur. Zehn Jahre lang – bis zu den Afrikanischen Spielen von 1936 – wird Jünger keine Erzählungen und Romane veröffentlichen.

In den zehn für das Schicksal Deutschlands entscheidenden Jahren von 1925–1935 schreibt Jünger Weltanschauungsprosa als politischer Publizist in einer Vielzahl meist rechtsstehender Organe, als Herausgeber verschiedener Sammelbände und als Essayist in den Büchern Das Abenteuerliche Herz (1929) und Der Arbeiter (1932). Aber das Jahr 1925 ist noch in anderer Hinsicht eine Zäsur: Jünger bricht das Studium ab und tritt in den bürgerlichen Stand der Ehe.

Dem im September 1923 im Völkischen Beobachter veröffentlichten Artikel folgt fast zwei Jahre lang keine im strengen Sinne politische Stellungnahme. Die regelmäßige politische Publizistik Jüngers beginnt am 31. August 1925 mit einem Aufsatz in der Zeitschrift Gewissen, dem Organ der sich um Arthur Moeller van den Bruck scharenden jungkonservativen >Ring-Bewegung<. Moderater im Ton als im Völkischen Beobachter finden sich die gleichen Forderungen wie zwei Jahre zuvor: Einsicht in die Bedeutung einer Idee und Notwendigkeit einer Revolution. Bemerkenswert ist der Publikationsort. Zwar lassen sich zwischen Jünger und dem Kreis um Moeller auch Gemeinsamkeiten nachweisen, aber in wesentlichen Punkten bestehen Differenzen – von ihnen wird später noch die Rede sein.

Jünger veröffentlichte seine politischen Traktate in einer Vielzahl auch Kennern der Zeitschriftenlandschaft der Weimarer Republik eher unbekannten Organen. 10 Man kann hier unterscheiden zwischen Zeitschriften, in denen Jünger als Gast schrieb – in der Regel gab es dann nur ein oder zwei Beiträge –, und solchen, in denen er regelmäßig zur Feder griff. Bei den meisten Zeitschriften, in denen Jünger regelmäßig schrieb, trat er auch als Mitherausgeber auf.

Jünger als Aktivist des Neuen Nationalismus in der Stahlhelm–Beilage Die Standarte (1925 / 26)

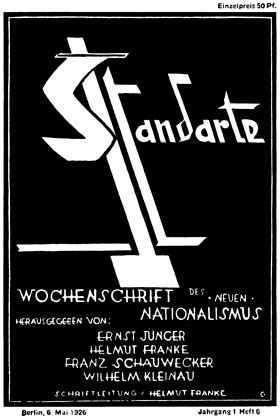

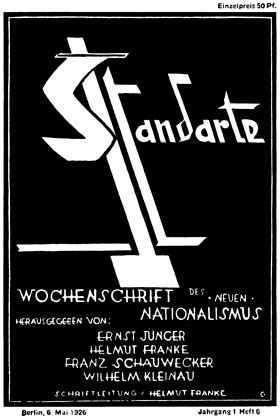

Die erste Zeitschrift, für die Jünger regelmäßig arbeitete, war das von ihm mitherausgegebene Blatt Die Standarte. Beiträge zur geistigen Vertiefung des Frontgedankens . Es erschien zum erstenmal im September als Sonderbeilage des Stahlhelm. Wochenschrift des Bundes der Frontsoldaten.

Mit dem Erscheinen dieser Beilage begann eine zunehmende Politisierung des Stahlhelm. Der im Dezember 1918 gegründete republikfeindlich eingestellte Bund der Frontsoldaten war schon aufgrund seiner hohen Mitgliederzahlen eine geeignete Zielgruppe für politische Agitation. 11 Bis zum Dezember schrieb Jünger für jede Nummer der wöchentlich erscheinenden Beilage. Diese insgesamt 17 Beiträge stehen in engem Zusammenhang, der letzte Beitrag erscheint als Schluß.

Von allen politischen Zeitschriftenarbeiten Jüngers dürften diejenigen in der Stahlhelm–Beilage Die Standarte die größte Wirkung gehabt haben. Die Wochenschrift des Stahlhelm hatte eine Auflage von 170 000 – eine Zahl, an die sämtliche anderen Zeitschriften, in denen Jünger veröffentlichte, nicht annähernd herankamen. Weil Jünger mit diesen Beiträgen vermutlich die größte Wirkung entfaltete, aber auch, weil sie für eine bestimmte Etappe in seinem politischem Schaffen stehen, sollen sie etwas ausführlicher behandelt werden.

Das Programm, das Jünger in der Stahlhelm–Beilage Die Standarte entwickelt, ist getragen von leidenschaftlicher Parteinahme für eine nationalistische Revolution. Auf einen Punkt von Jüngers Physiognomie der Gegenwart sind alle weiteren Überlegungen bezogen. Jünger lebt im Glauben, daß der große Krieg noch gar kein Ende gefunden habe, noch nicht endgültig verloren sei. Politik ist ihm daher eine Form des Krieges mit anderen Mitteln (S. 63f.). Die Generation der vom Krieg geprägten Frontsoldaten soll diesen Krieg fortsetzen. Jünger will nicht zurückschauen, sondern die Zukunft gestalten. Die Gruppe der Frontsoldaten, der sich Jünger zurechnet, muß daher versuchen, die Jugend zu gewinnen (S. 77).

Jüngers Programm nennt sich>Nationalismus<: "Ja wir sind nationalistisch, wir können gar nicht nationalistisch genug sein, und wir werden uns rastlos bemühen, die schärfsten Methoden zu finden, um diesem Nationalismus Gewalt und Nachdruck zu verleihen" (S. 163). Das nationalistische Programm soll auf vier Grundpfeilern basieren: Der kommende Staat muß national, sozial, wehrhaft und autoritativ gegliedert sein (S. 173, S. 179, S. 197, S. 218). Die "Staatsform ist uns nebensächlich, wenn nur ihre Verfassung eine scharf nationale ist" (S. 151). "Der Tag, an dem der parlamentarische Staat unter unserem Zugriff zusammenstürzt, und an dem wir die nationale Diktatur ausrufen, wird unser höchster Festtag sein" (S. 152). Mit dem Schlagwort Nationalismus ist wenig gesagt. Was ist es, das den Nationalismus des Frontsoldaten auszeichnet?

Durch den Krieg, so Jünger, wurde der von der wilhelminischen Epoche geprägte Frontsoldat in ganz andere Bahnen gerissen: "Er betrat eine neue, unbekannte Welt, und dieses Erlebnis rief in vielen jene völlige Veränderung des Wesens hervor, die sich am besten mit der religiösen Erscheinung der >Gnade< vergleichen läßt, durch welche der Mensch plötzlich und von Grund auf verwandelt wird" (S. 79).

Mit dem Ende des Kaiserreichs verbindet Jünger die Überwindung einer materialistischen Naturanschauung, der individualistischen Idee allgemeiner Menschenrechte und des bloßen Strebens nach materiellem Wohlstand. Dagegen behauptet er die Bedeutung der >Nachtseite< des Lebens. 12 Gegen das rationalistische, mechanistische, materialistische Denken des Verstandes setzt er das Gefühl und den organischen Zusammenhang mit dem Ganzen: "Für uns ist das Wichtigste nicht eine Revolution der staatlichen Form, sondern eine seelische Revolution, die aus dem Chaos neue, erdwüchsige Formen schafft." (S. 114).

Mit dem Ende des Kaiserreichs verbindet Jünger die Überwindung einer materialistischen Naturanschauung, der individualistischen Idee allgemeiner Menschenrechte und des bloßen Strebens nach materiellem Wohlstand. Dagegen behauptet er die Bedeutung der >Nachtseite< des Lebens. 12 Gegen das rationalistische, mechanistische, materialistische Denken des Verstandes setzt er das Gefühl und den organischen Zusammenhang mit dem Ganzen: "Für uns ist das Wichtigste nicht eine Revolution der staatlichen Form, sondern eine seelische Revolution, die aus dem Chaos neue, erdwüchsige Formen schafft." (S. 114).

Die Weltanschauung, die Jünger seiner Generation der Frontsoldaten empfiehlt, hat ihre Wurzeln in der Romantik und der Lebensphilosophie Nietzsches. Jünger betont die Bedeutung des Gefühls der Gemeinschaft, der Verbindung mit dem Ganzen, denn das Gefühl stehe am Anfang jeder großen Tat. Wachstum ist für Jünger das natürliche Recht alles Lebendigen (S. 82), das keines Beweises zu seiner Rechtfertigung bedarf (S. 186):

Alles Leben unterscheidet sich und ist schon deshalb kriegerisch gegeneinander gestellt. Im Verhältnis des Menschen zu Pflanzen und Tieren tritt das ohne weiteres hervor, jeder Mittagstisch liefert den unwiderleglichen Beweis. Das Leben äußert sich jedoch nicht nur im Kampfe der Arten untereinander, sondern auch im Kampfe innerhalb der Arten selbst. (S. 133) 13

Jünger hat den soziologischen Blick, der dem Konservatismus seit der Romantik eigen ist. Deutlich zeigt sich seine Aufnahme romantischen Geschichtsdenkens in der Betonung des Besonderen gegen das Allgemeine, seiner Betonung der Abhängigkeit "von unserer Zeit und unserem Raum" (S. 158). Er fordert, mit "dem unheilvollen Streben nach Objektivität, die nur zur relativistischen Aufhebung der Kräfte führt, aufzuräumen" und sich zu bewußter Einseitigkeit zu bekennen, "die auf Wertung und nicht auf >Verständnis< beruht" (S. 79f.).

Ein wichtiges Moment in Jüngers Geschichtsdenken ist das Verhältnis von soziologischer Diagnose und zukünftiger Aufgabe. Wenn Jünger bestimmte historische Entwicklungen untersucht, bemüht er häufig die Kategorie der Notwendigkeit. Ereignisse treten mit Notwendigkeit ein. In der gescheiterten Revolution "lag auch eine Notwendigkeit" (S. 110). Über die Entwicklung der Technik urteilt er: "Zwangsläufige Bewegungen lassen sich nicht aufhalten" (S. 160).

Hinter der Überzeugung, daß bestimmte Ereignisse mit Notwendigkeit eintreten, steht die Vorstellung einer überpersönlichen Idee, die sich in der Geschichte zu verwirklichen sucht: Im Krieg gibt es Augenblicke, in denen "die kriegerische Idee sich rein, vornehm und mit einer prächtigen Romantik offenbart. Dort werden Heldentaten verrichtet, in denen kaum noch der Mensch, sondern die kristall-klare Idee selbst am Werke scheint" (S. 109).

Über den geschichtsphilosophischen Schwung der Jahre, in denen diese Aufsätze entstanden sind, schrieb Jünger am 20. April 1943 rückblickend in seinem zweiten Pariser Tagebuch:

Es ist die Geschichte dieser Jahre mit ihren Denkern, ihren Tätern, Märtyrern und Statisten noch nicht geschrieben; wir lebten damals im Eie des Leviathans. [...] Die Mitspieler sind ermordet, emigriert, enttäuscht oder bekleiden hohe Posten in der Armee, der Abwehr, der Partei. Doch immer werden diejenigen, die noch auf Erden weilen, gern von jenen Zeiten sprechen; man lebte damals stark von der Idee. So stelle ich mir Robespierre in den Arras vor. 14

Für den Jünger der zwanziger Jahre gilt: Der Mensch ist nichts ohne eine Idee. Scheitert die Verwirklichung einer Idee, wie in der Novemberrevolution, so scheitert sie notwendig, weil sie noch nicht stark genug war. Die Zeit war dann noch nicht reif genug. Aufgabe des einzelnen ist es, sich in den Dienst der Idee zu stellen: Die großen geschichtlichen Leistungen besitzen die Eigenschaft, daß der "Mensch nur als Werkzeug einer höheren Vernunft" (S. 93) tätig ist. 15

Auch hier zeigt sich: Jüngers Geschichtsdenken kommt aus dem 19. Jahrhundert und zeigt den für die Ideenlehre der historischen Schule typischen Hang zur geschichtsphilosophischen Spekulation. Karl Löwith, der Jünger in der Folge Nietzsches sah, hat darauf hingewiesen, daß "Jünger selbst noch der bürgerlichen Epoche entstammt" und daher in der problematischen Lage sei, daß das Alte nicht mehr und das Neue noch nicht gilt. 16 Dies gilt weniger für die Inhalte, umsomehr aber für die Formen von Jüngers Denken.

Durch den Einfluß von Nietzsches vitalistischer Teleologie werden Jüngers geschichtsphilosophische Spekulationen auch biologisch fundiert: "Aber je mehr man beobachtet, desto mehr kommt man dazu, an die große geheimnisvolle Steuerung durch eine große biologische Vernunft zu glauben" (S. 171). 17 Und auch sein Begriff der Zeit zeigt Jünger, dem die Arbeiten Bergsons vertraut waren, in der Tradition des organologisch-lebensphilosophischen Denkens des 19. Jahrhunderts: Zeit ist ihm nichts Zufälliges, "sondern ein geheimnisvoller und bedeutungsvoller Strom, der jedes durchfließt und sein Inneres richtet, wie ein elektrischer Strom die Atome eines metallischen Körpers richtet und regiert" (S. 182).

>Konservative Revolution<

Die Hinweise auf die Wurzeln von Jüngers Denken erfolgen nicht in der Absicht, Jüngers Originalität zu schmälern oder der bekannten Linie das Wort zu reden, nach der die Lebensphilosophie in den Faschismus mündet. Vielmehr geht es darum, Jüngers Geschichtsdenken in Beziehung zu setzen zur sogenannten >Konservativen Revolution<. Es soll untersucht werden, ob Jüngers Denken als konservative Revolution im Sinne der als >Konservative Revolution< etikettierten Geistesrichtung der Weimarer Republik begriffen werden kann.

Jüngers revolutionäre Einstellung ist offenkundig. Weniger deutlich ist, inwiefern sein Denken >konservativ<genannt werden kann. Das wichtigste >konservative< Moment in Jüngers Denken liegt in der Bedeutung der Gemeinschaft.

Das Gefühl der >Gemeinschaft in einem großen Schicksal<, das am Beginn des Krieges stand, das Bewußtsein der Idee der Nation und die gemeinsame >Unterwerfung unter eine Idee< sind für Jünger Zeichen einer grundsätzlichen Kurskorrektur: "Wir erblicken darin die erste Anknüpfung einer verloren gegangenen Verbindung, die Offenbarung einer höheren Sicherheit, die sich im Persönlichen als Instinkt äußert" (S. 86).

Jünger bejaht die Revolution, aber er schränkt ihre Bedeutung zugleich ein, indem er sie als Methode und nicht als Ziel begreift. Sie kann nur Methode sein, denn der "Frontsoldat besitzt Tradition und weiß, daß alle Größe und Macht organisch gewachsen sein muß, und nicht aus der reinen Verneinung, aus dem leeren Dunst herausgegriffen werden kann. Wie er den Krieg nicht verleugnet, sondern aus ihm als einer stolzen Erinnerung heraus die Kraft zu neuen Aufgaben zu schöpfen sucht, so fühlt er sich auch nicht berufen, das zu verachten, was die Väter geleistet haben, sondern er sieht darin die beste und sicherste Grundlage für das neue größere Reich." (S. 124f.; vgl. S. 128f.)

Die Denkfigur einer >Konservativen Revolution< zielt auf den Versuch, einen organischen Zusammenhang wiederherzustellen. Das Eintreten für eine >Konservative Revolution< lebt also wesentlich von der Entscheidung, an welche gewachsenen Traditionen wieder angeschlossen werden soll. Jüngers Forderung nach einer Revolution, die an die Tradition anschließt, bestimmt sich aber im wesentlichen ex negativo. Die Verbindung, die Jünger zwischen seiner historistischen Lebensphilosophie und seinem Nationalismus herstellen will, bleibt so rein äußerlicher Natur. Es fehlt ihr der Nachweis eines inneren Zusammenhanges.

Ein Argument für diesen Zusammenhang bleibt nur der Versuch, das Individuum auf der Ebene des Gefühls an die organisch gewachsene Nation zu binden. Die Bildung der Nation müßte aber nicht zwingend auf Jüngers Fassung eines autoritativen Nationalismus hinauslaufen. Lediglich die Opposition zu bestimmten Weltanschauungen ist durch den Willen, das Individuum organisch einzubinden, notwendig. Für die Krise des entwurzelten Individuums ist diesem Willen gemäß der Liberalismus und mit ihm die Idee der parlamentarischen Demokratie verantwortlich.

Die großen Gefahren sieht Jünger daher "nicht im marxistischen Bollwerk" (S. 148, S. 151), sondern in allem, was mit dem Liberalismus zusammenhängt: Die "Frage des Eigentums gehört nicht zu den wesentlichen, die uns vom Kommunismus trennen. Sicher steht uns der Kommunismus als Kampfbewegung näher als die Demokratie, und sicher wird irgendein Ausgleich, sei er friedlicher oder bewaffneter Natur erfolgen müssen"(S. 117).

Nach der Trennung vom Stahlhelm

Schon die 19 Aufsätze in der Beilage Die Standarte zwischen September 1925 und März 1926 würden ausreichen, um das Urteil zu korrigieren, Jünger sei im Grunde ein unpolitischer Einzelgänger gewesen. Unabhängig von den politischen Bekenntnissen, die Jünger abgibt, wird dies schon durch seine leidenschaftliche Parteinahme deutlich. Aber auch später spricht Jünger von dem kleinen Kreis, dem er angehöre (S. 197), und greift immer wieder auf die Wir-Form zurück: "Wir Nationalisten" (S. 207). Ein Aufsatz beginnt mit der Anrede: "Nationalisten! Frontsoldaten und Arbeiter!" (S. 250) Und in einem anderen heißt es: "ich spreche im Namen von hunderttausend Frontsoldaten" (S. 267).

Um so erstaunlicher ist es, daß der Herausgeber Sven Berggötz in seinem Nachwort schreibt, Jünger hätte zwar durchaus einen beachtlichen Leserkreis erreicht, aber dieser hätte "sich weitgehend auf Leser mit einem ähnlichen Erfahrungshintergrund beschränkt". So habe er zwar auf die Meinungsbildung eingewirkt, aber "mit Sicherheit nicht in signifikanter Weise Einfluß auf die öffentliche Meinung genommen" (S. 867).

Weshalb 170 000 den Stahlhelm lesende ehemalige Frontsoldaten nicht zur öffentlichen Meinung zählen, bleibt Berggötz' Geheimnis – oder wollte Berggötz bloß sagen, die Stahlhelmer dachten ohnehin schon, was Jünger formulierte? Von welchem Autor ließe sich dann nicht behaupten, er artikuliere nur, was andere denken? Noch unverständlicher ist aber sein abschließendes Urteil: "Letztlich war Jünger schon damals ein im Grunde unpolitischer Mensch, der im wesentlichen utopische Vorstellungen vertrat." (S. 868) Als ob Utopie und Politik einen Gegensatz darstellten. 18

Der Stahlhelm–Beilage Die Standarte war keine lange Lebenszeit beschieden. Schon nach sieben Monaten erschien Die Standarte im März 1926 nach Unstimmigkeiten mit der Bundesleitung des Stahlhelm zum letzten Mal. Nachfolgeorgan war die fast gleichnamige Standarte. Wochenschrift des neuen Nationalismus, die nun selbständig erschien – herausgegeben von Ernst Jünger, Helmuth Franke, Franz Schauwecker und Wilhelm Kleinau. Ihre Auflage von vermutlich wenigen Tausend Exemplaren reichte nicht annähernd an Die Standarte heran.

Das Selbstverständnis der Herausgeber wird in einem programmatischen Beitrag Helmut Frankes für die erste Nummer der neuen Standarte deutlich: "Wir Standarten-Leute kommen aus allen Lagern: Vom konservativen bis zum jungsozialistischen. Die faschistische Schicht hat kein Programm. Sie wächst und handelt. " 19

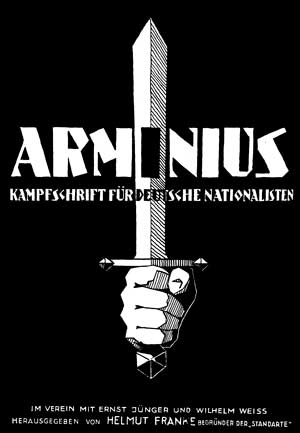

Auch die Standarte erschien nicht lange. Im August 1926 wurde die Zeitschrift vorübergehend verboten, weil in dem Artikel Nationalistische Märtyrer die Morde an Walther Rathenau und Matthias Erzberger legitimiert worden waren. Im November 1926 gründete Jünger mit Helmut Franke und Wilhelm Weiss die nächste Zeitschrift: Arminius. Kampfschrift für deutsche Nationalisten (teilweise mit dem Nebentitel: Neue Standarte), die bis September 1927 existierte. Im Oktober 1927 gründete Jünger mit Werner Lass die Zeitschrift Vormarsch. Blätter der nationalistischen Jugend, die bis 1929 erschien. Die nächste Zeitschrift war ebenfalls ein Gemeinschaftsprojekt von Jünger und Werner Lass. Von Januar 1930 bis Juli 1931 gaben sie die Zeitschrift Die Kommenden. Überbündische Wochenschrift der deutschen Jugend heraus.

Zwischen 1926 und 1930 war Jünger also nahezu ununterbrochen in die Herausgabe von Zeitschriften involviert. Neben einer Vielzahl von Beiträgen, die er für seine Zeitschriften schrieb, veröffentlichte Jünger auch in einigen anderen Organen, z. B. in Wilhelm Stapels Deutschem Volkstum.

Einzelne Beiträge erschienen auch in Zeitschriften der demokratischen Linken, in Willy Haas' Literarischer Welt und in Leopold Schwarzschilds Das Tagebuch. Hier stellte Jünger seinen Nationalismus vor. Eine größere Zahl von Beiträgen plazierte Jünger in Ernst Niekischs Widerstand. Zeitschrift für nationalrevolutionäre Politik. Nach 1931 schrieb er fast nur noch in diesem Blatt. Die Hauptphase seiner politischen Arbeiten endet 1930.

Jünger und die Jungkonservativen

Nachdem die Stahlhelmleitung im Oktober 1926 die Parole >Hinein in den Staat< ausgegeben hatte, ging Jünger scharf auf Distanz. Im November 1926 äußerte er seine Befremdung ob der Ereignisse im Stahlhelm und reagierte: Der Wille müsse frei gemacht werden von "organisatorischen Verbindungen, die sich als Fessel" erwiesen haben (S. 258): "Reine Bewegung, aber nicht Bindung fordern wir" (S. 259, vgl. S. 256). Im Februar 1927 wiederholte er im Arminius seinen Angriff: Der Stahlhelm ist "bürgerlicher und damit liberalistischer Natur" (S. 305).

Hinter dem Bekenntnis zum Staat, das die Stahlhelmleitung verkündet hatte, vermutete Jünger bestimmte Interessengruppen: Man "bemühe sich mit Hilfe zur Verstärkung herbeigerufener Routiniers, die sich durch jahrelange Tätigkeit an jenen esoterischen Debattierklubs in Berlin W. ein Höchstmaß an politischer Balancierkunst erworben haben, die Hineinparole so zu verklausulieren, daß sie ebensogut sie selbst wie ihr Gegenteil sein kann" (S. 305).

Nachdem Jünger und seine Mitstreiter aus dem Stahlhelm zurückgedrängt worden waren, gewannen Mitglieder des Juniklubs zunehmend Einfluß. 20 Neben Heinz Brauweiler, dem Theoretiker des Ständestaats, tat sich vor allem der >Antibolschewist< Eduard Stadtler hervor. 21 Stadtler war vor dem Krieg Sekretär der Jugendbewegung der Zentrumspartei. Nach dem Krieg wurde er durch die Gründung der Antibolschewistischen Liga bekannt. Stadtler gehörte zu den ersten, die eine Verbindung von Konservatismus und Revolution als Programm expressis verbis formulierten. 22 Anfang der zwanziger Jahre war er eine der führenden Figuren des Juniklubs.

Versteht man unter >Konservativer Revolution< eine politische Richtung, den Zusammenhang verschiedener Personen und Gruppen, die ein gemeinsames politisches Ziel haben, so ist zu klären, in welchem Verhältnis diese Personen zueinander standen, wo und wie sie sich organisierten.

Im August 1926 hatte Jünger geschrieben: "Dieser Nationalismus ist ein großstädtisches Gefühl" (S. 234). Im Juni 1927 zog er mit seiner jungen Familie von Leipzig nach Berlin um. Zunächst wohnte er in der Nollendorfstraße in Schöneberg, also in unmittelbarer Nähe der Motzstraße, wo die Jungkonservativen im Schutzbundhaus in der Nr. 22 ihre Zusammenkünfte abhielten. Jünger blieb nicht lange in West-Berlin. Bereits nach einem Jahr siedelte er um in den Ostteil der Stadt, in die Stralauer Allee, wo vornehmlich Arbeiter wohnten. 23 1931 zog Jünger in die Dortmunder Straße, nähe Bellevue, 1932 in das ruhige, bürgerliche Steglitz.

Natürlich kann man aus dem Wechsel der Wohnorte nicht einfach auf die Entwicklung eines Denkens schließen. Aber es wird kein bloßer Zufall gewesen sein, daß Jünger zunächst in so unmittelbarer Nähe der Motzstraße wohnte, daß er den Arbeiter schrieb und in einem Arbeiterviertel wohnte, daß sein allmählicher Rückzug aus der politischen Agitation mit dem Umzug nach Steglitz zusammenfiel.

Über die Kontakte Jüngers zu den Jungkonservativen ist wenig bekannt. Hans-Joachim Schwierskott hat seiner Biographie Moellers eine Mitgliederliste der Jungkonservativen beigegeben, in der sich auch der Name Jüngers findet. 24 Aber das Verhältnis zwischen Jünger und den Jungkonservativen war gespannt. In seinen politischen Arbeiten erwähnt Jünger Moeller gelegentlich, aber neben einer Anspielung auf Edgar Julius Jungs Buch Die Herrschaft der Minderwertigen (S. 432) gibt es kaum explizite Hinweise auf eine Auseinandersetzung mit den Jungkonservativen.

Der erwähnte Angriff auf die "esoterischen Debattierclubs in Berlin-West" deutet darauf hin, daß Jünger in für ihn wesentlichen Punkten Differenzen zwischen sich und Jungkonservativen wie Eduard Stadtler, Max Hildebert Boehm oder Edgar Julius Jung sah. Vermutlich waren sie ihm zu bürgerlich, zu liberal, zu christlich, zu sehr im Staat. Den Gedanken einer hierarchisch geprägten Stände-Gesellschaft lehnte Jünger vehement ab: "Aufgrund des Blutes und des Charakters wollen wir uns in Gemeinschaften und immer größere Gemeinschaften binden, ohne Rücksicht auf Wissen, Stand und Besitz, und uns klar trennen und scheiden von allem, was nicht in diese Gemeinschaften gehört" (S. 212).

Aus den Reihen der sich um den 1925 verstorbenen Moeller van den Bruck gruppierenden Jungkonservativen sollte Jünger später heftig attackiert werden. Seine konsequenten Angriffe auf alles Bürgerliche – ein Grundmotiv der politischen Publizistik, das er im Arbeiter besonders radikal vertrat – brachte Jünger eine heftige Replik seitens Max Hildebert Boehms ein. 25 Aber Jünger hat von Seiten der Jungkonservativen auch Zuspruch gefunden. Der Philosoph Albert Dietrich, ein Schüler Ernst Troeltschs und Mitglied des Juniklubs seit der ersten Stunde, überwarf sich mit Boehm über dessen Angriff auf Jünger. 26 Auch hatte Jünger gute Kontakte zu einem anderen Flügel der Jungkonservativen Bewegung‚ zum sogenannten >Tatkreis< um Hans Zehrer, Giselher Wirsing und Ferdinand Fried. 27

Deutungsmöglichkeiten

Ob die Zuordnung Jüngers zur >Konservativen Revolution< gerechtfertigt ist, kann nicht pauschal entschieden werden. Zumindest drei Unterscheidungen bieten sich an.

Es sind erstens die personellen Verbindungen zu betrachten. Sie können Zeichen sein für ein gemeinsames Arbeiten an gemeinsamen Zielen, auch wenn in letzter Instanz die Ziele nicht die gleichen sind. Zweitens sind die konkreten politischen Positionen zu untersuchen und zu vergleichen. Und drittens ist nach Gemeinsamkeiten der Denkstile, der Denkfiguren, der Mentalität zu suchen.

Es sind erstens die personellen Verbindungen zu betrachten. Sie können Zeichen sein für ein gemeinsames Arbeiten an gemeinsamen Zielen, auch wenn in letzter Instanz die Ziele nicht die gleichen sind. Zweitens sind die konkreten politischen Positionen zu untersuchen und zu vergleichen. Und drittens ist nach Gemeinsamkeiten der Denkstile, der Denkfiguren, der Mentalität zu suchen.

Über die erste Möglichkeit einer Zuordnung sind bereits einige Anmerkungen gemacht worden. Ihre Bearbeitung erfordert die umfangreiche Sichtung der Nachlässe, um anhand von Briefzeugnissen und anderen persönlichen Dokumenten bekannte und unbekannte Verbindungen zu rekonstruieren.

Die zweite Möglichkeit ist durch die Arbeiten Stefan Breuers sehr erhellt worden. Breuer hat in einem Vergleich der konkreten politischen Positionen einer großen Gruppe von Autoren und Strömungen, die Armin Mohler und einige andere als >Konservative Revolution< bezeichnet haben, eindrucksvoll gezeigt, daß sich insgesamt betrachtet eine im einzelnen auch noch unterschiedlich weit gehende Liberalismuskritik als einziger gemeinsamer Nenner ausmachen läßt.

Dies ist nach Breuer zu wenig, um von einem einheitlichen Gebilde zu sprechen, da eine vehemente Kritik des Liberalismus auch von anderer Seite geübt wurde. Die Rede von der >Konservativen Revolution<, so Breuer, sei daher aufzugeben, da es sich um einen im wesentlichen auf Mohler zurückgehenden Mythos der Forschung handle. 28

Die Suche nach einheitsstiftenden Momenten der >Konservativen Revolution< kann auch jenseits konkreter politischer Programme auf der Ebene der Denkstile und der Mentalität ansetzen. Für Mohler ist diese dritte Möglichkeit die entscheidende. Nach Mohler ist das entscheidende Leitbild die "ewige Wiederkehr des Gleichen" Er versteht dieses Bild als den Versuch, die christliche Auffassung der Geschichte zu sprengen. Das Bild "der ewigen Wiederkehr des Gleichen" biete ein Gegenstück zum linearen Modell der Zeit, an welches die Idee des Fortschritts gekoppelt sei.

Zwar meint Mohler, daß es nicht für alle, die er der >Konservativen Revolution< zurechnet, "in gleichem Maße verpflichtend" sei, aber ihre wesentliche Denkfigur sieht er in den Gedanken Nietzsches vorgebildet. Er folgt Nietzsche in dem Dreischritt: Diagnose des Wertezerfalls, Affirmation dieses Prozesses (Nihilismus) bis zur Vollendung der Zerstörung der alten (christlichen) Werte, damit die Zerstörung in Schöpfung umschlagen kann. 29

Auch Breuer findet auf der Ebene der Mentalität eine Gemeinsamkeit der >Konservativen Revolution<. Während er in den konkreten politischen Positionen keine hinreichende Übereinstimmung findet, die es nahelegen würde, von der >Konservativen Revolution< zu sprechen, sieht er bei allen Autoren eine "Kombination von Apokalyptik, Gewaltbereitschaft und Männerbündlertum" 30 . Diese Bestimmung ist jedoch, wie Breuer selbst bemerkt, zu weit und unbestimmt, und daher ebenso unbefriedigend wie die Bestimmung über die gemeinsame Kritik am Liberalismus.

Mohlers Bestimmung hingegen ist zu eng. Die Unterstellung, der >Konservativen Revolution< sei eine antichristliche Stoßrichtung genuin inhärent, ist denn auch unmittelbar nach Erscheinen der ersten Auflage seines Buches stark kritisiert worden. 31

In der Linie dieser Kritik kann man gegen Mohler einwenden, einseitig einen eher unorganischen Begriff des Konservatismus in den Mittelpunkt gestellt zu haben. Wenn Mohler, die Formulierung Albrecht Erich Günthers aufgreifend, das Konservative versteht "nicht als ein Hängen an dem, was gestern war, sondern an dem was immer gilt", so betont er nur ein Moment des Konservatismus. 32 Denn der deutsche Konservatismus ist seit seinen Ursprüngen in der Romantik weitgehend organologisch und historistisch, d. h. mehr dem Gedanken organischer Entwicklung und einer sich entwickelnden und unterschiedlich ausgestaltenden Wahrheit als dem überzeitlicher Geltung verpflichtet.

In Mohlers Bestimmung des Konservativen ist die Tradition des romantischen Konservatismus – also gerade die Tradition, der die meisten Jungkonservativen verpflichtet sind – zu sehr in den Hintergrund gerückt. 33 So ergibt sich ein schiefes Bild: Diejenige Gruppe, die die Parole >Konservative Revolution< populär gemacht hat, ist in Mohlers Fassung der >Konservativen Revolution< eine Randgruppe, der eine "nur sehr bedingte revolutionäre Haltung" attestiert wird. 34

Nur folgerichtig ist daher Mohlers Vermutung, daß bei der Verbindung von jungkonservativem Christentum und seinem Leitbild der >Konservativen Revolution< eines von beidem Schaden leide.

Zu den Merkmalen organologischen Denkens im deutschen Konservatismus sind im wesentlichen zwei Momente zu zählen: Zum einen die Annahme einer Eingebundenheit des Einzelnen in die Gemeinschaft, zum anderen ein Bild der Geschichte, nach dem eines aus dem anderen wachsen soll. Konservativ sein, bedeutet seit Edmund Burkes Kritik der Französischen Revolution eine kritische Haltung gegenüber jeder radikalen gesellschaftlichen Veränderung. Nicht Veränderung überhaupt, sondern jede Veränderung, die sich nicht in einer Gemeinschaft organisch entwickelt, wird vom konservativen Standpunkt abgelehnt.

Indem der Konservatismus seine Wurzeln in der Kritik der französischen Revolution hat, ist ihm von Beginn an die aporetische Struktur einer >Konservativen Revolution< eigen. 35 Ist der organische Zusammenhang einmal aufgebrochen, muß sich der Konservative eines Mittels bedienen, das er eigentlich ablehnt. Er muß durch einen radikalen Schritt wieder versuchen, gemeinschaftliche Bindung zu gewinnen. Kein Konservatismus kann seine Werte erst neu schaffen.

Aber je tiefer die in der Vergangenheit liegenden Werte verschüttet sind, desto schwieriger wird der Versuch, wieder einen Anschluß zu gewinnen. Nach dem ersten Weltkrieg ist der Konservatismus in Deutschland in einer Verfassung, in der über den Gehalt der Werte der Gemeinschaft – wie die Untersuchungen Breuers zeigen – keine Einigkeit mehr besteht.

Der Schluß, den Breuer aus diesem Ergebnis zieht, daß man besser nicht mehr von der >Konservativen Revolution< sprechen sollte, könnte dennoch verfrüht sein. Denn es könnte ja entweder sein, daß die Formel >Konservative Revolution< eine gemeinsame Denkfigur verschiedener Gruppen benennt, oder aber, daß zwar sinnvoll von der >Konservativen Revolution< gesprochen werden kann, die Gruppe derer, die ihr angehören, jedoch enger gezogen werden muß, als in den Arbeiten Mohlers und seiner Nachfolger.

Konservativ ?

In eigener Sache hat Jünger das Bild einer >Konservativen Revolution< nicht verwendet. Schon der Begriff >konservativ< für sich genommen bezeichnet für Jünger in der Regel etwas ihm Fremdes (218). In Sgrafitti blickte er 1960 mit Distanz auf die Idee einer >Konservativen Revolution< zurück. 36

Er selbst zählte sich ganz offensichtlich nicht zur >Konservativen Revolution<. Alfred Andersch gegenüber bekannte er im Juni 1977: "Sie rechnen mich nicht den Konservativ-Nationalen, sondern den Nationalisten zu. Rückblickend stimme ich dem zu. " 37

Daß sich bei Jünger die Formulierung >Konservative Revolution< nicht in eigener Sache findet, muß nicht bedeuten, daß sich nicht wesentliche ihrer Momente bei ihm aufweisen lassen. Jünger glaubte ja, nur auf dem Weg einer Revolution könne eine Überwindung der mißlichen Gegenwart gelingen.

Die Frage bleibt nur, inwiefern die erstrebten Veränderungen als konservativ aufgefaßt werden können. In den Aufsätzen der Jahre 1925 und 1926 fanden sich einige für das Denken des Konservativen typische Momente: die Bedeutung der Gemeinschaft und die Bedeutung der Tradition.

Etwa ab dem Frühjahr 1926 – in einer Phase, die politisch zu den stabilsten der Weimarer Republik gehörte – wird Jünger in seinen Positionen jedoch immer radikaler. Von einer Bedeutung der Tradition ist nicht mehr die Rede.

Bei oberflächlicher Betrachtung ist eine Veränderung seines Denkens nicht zu erkennen, denn noch im September 1929 bestimmt er den Charakter des Nationalismus wie ehedem durch Angabe der genannten vier Punkte: Der Nationalismus strebe den national, sozial, wehrhaft und autoritativ gegliederten Staat aller Deutschen an (S. 504). Immer wieder kehren die Motive, daß das Sterben der Soldaten im großen Krieg einen Sinn gehabt habe (S. 239), daß alles Wesentliche nur erfühlt und nicht begriffen werden könne (S. 288).

Bestimmend bleibt auch die Bedeutung der Idee: "Nach neuen Zielen verlangt unser Blut, es fordert Ideen, an denen es sich berauschen, Bewegungen, in denen es sich erschöpfen und Opfer, durch die es sich selbst verleugnen kann" (S. 196).

Bestimmend bleibt auch die Bedeutung der Idee: "Nach neuen Zielen verlangt unser Blut, es fordert Ideen, an denen es sich berauschen, Bewegungen, in denen es sich erschöpfen und Opfer, durch die es sich selbst verleugnen kann" (S. 196).

Etwa seit Mitte 1926 zeigen sich deutliche Akzentverschiebungen. Immer stärker hebt Jünger nun die Notwendigkeit reiner Bewegung, reiner Dynamik hervor: Die Stärke einer Aktion besteht darin, "daß sie zu hundert Prozent Bewegung bleibt" (S. 256, vgl. auch S. 267). 38 Jüngers eigene Einschätzung gibt eine interessante Beschreibung der kollektiven Psyche seiner Generation: "Wir sind Dreißigjährige, früh durch eine harte Schule gegangen, und was sich in uns nicht gefestigt hat, das wird nicht mehr zu festigen sein." (S. 206)

Der Bruch mit dem Stahlhelm war mehr als ein tagespolitisches Ereignis. Er markiert den Beginn eines neuen Angriffs. Jünger fordert weiter, aber forcierter als bisher, die Revolution und den Bruch mit der Demokratie. Mit dem Ehrentitel Nationalisten wollen sich er und die seinen – "Männer, die gefährlich sind, weil es ihnen eine Lust ist, gefährlich zu sein" – vom "friedlichen Bürger" abwenden, schreibt er im Mai 1926 (S. 213). Der Nationalist habe

die heilige Pflicht, Deutschland die erste wirkliche, das heißt von sich rücksichtslos bahnbrechenden Ideen getriebene Revolution zu schenken. Revolution, Revolution! Das ist es, was unaufhörlich gepredigt werden muß, gehässig, systematisch, unerbittlich, und sollte dieses Predigen zehn Jahre lang dauern. [...] Die nationalistische Revolution braucht keine Prediger von Ruhe und Ordnung, sie braucht Verkünder des Satzes: >Der Herr wird über Euch kommen mit der Härte des Schwerts!< Sie soll den Namen Revolution von jener Lächerlichkeit befreien, mit der er in Deutschland seit fast hundert Jahren behaftet ist. Im großen Kriege hat sich ein neuer gefährlicher Menschenschlag entwickelt, bringen wir diesen Schlag zur Aktion! (S. 215)

Seine grundsätzliche Ablehnung der Demokratie brachte Jünger in einem Punkt immer wieder in Distanz zum Nationalsozialismus. Vor den Wahlen schrieb er im August 1926: "es bedeutet einen verhängnisvollen Zwiespalt, eine Einrichtung als theoretisch unsittlich zu erklären und gleichzeitig praktisch an ihr teilzunehmen. [...] Was gefordert werden muß, ist ein allgemeines striktes Verbot, an einer Wahl teilzunehmen" (S. 243ff.).

Schon früher hatte Jünger deutlich gemacht, daß er keinen unüberwindbaren Gegensatz zwischen Sozialismus und Nationalismus entdecken könne. Im Dezember 1926 bekannte er sich offen zur bolschewistischen Wirtschaftspolitik: "Wir suchen die Wirtschaftsführer davon zu überzeugen, daß unser Weg auf geradester Linie zu jener staatlich geordneten Zentralisation führt, die uns allein konkurrenzfähig erhalten kann." (S. 269)

Historismus

Mit der Liberalismuskritik der Romantik, mit den >Ideen von 1914<, teilt Jünger weiter wesentliche Überzeugungen: Es gebe kein moralisches Gesetz an sich, jedes Gesetz werde durch den Charakter bestimmt. Denn Charaktere "sind nicht den Gesetzen des Fortschrittes, sondern denen der Entwicklung unterworfen. Wie in der Eichel schon der Eichbaum vorausbestimmt ist, so liegt im Charakter des Kindes schon der des Erwachsenen" (S. 210). Allgemeine Wahrheiten, eine allgemeine Moral läßt Jüngers Historismus nicht gelten:

Wir glauben vielmehr an ein schärfstes Bedingtsein von Wahrheit, Recht, Moral durch Zeit, Raum und Blut. Wir glauben an den Wert des Besonderen. [...] Aber ob man an das Allgemeine oder das Besondere glaubt, das ist nicht das Wesentliche, wie am Glauben überhaupt nicht die Inhalte das Wesentliche sind, sondern seine Glut und seine absolute Kraft. (S. 280)

Jünger nimmt hier – im Januar 1927 – ein zentrales Motiv des Abenteuerlichen Herzens vorweg: "Ein Recht ist nicht, sondern wird gesetzt, und zwar nicht vom Allgemeinen, sondern vom Besonderen" (S. 283). Im Abenteuerlichen Herz heißt es noch eindrücklicher: "Daher kommt es, daß diese Zeit eine Tugend vor allen anderen verlangt: die der Entschiedenheit. Es kommt darauf an, wollen und glauben zu können, ganz abgesehen von den Inhalten, die sich dieses Wollen und Glauben gibt." 39

Wenn die Einsicht in die historische Gewordenheit die Absolutheit jeder Weltanschauung in Frage stellt, kann dies dazu führen, daß keine wahrer und damit verbindlicher scheint als die andere. In so einer Zeit mag es durchaus sinnvoll sein, für die Bedeutung der Entscheidung, ja für die Notwendigkeit der Entscheidung einzutreten. Wenn aber das >wofür< der Entscheidung beliebig wird, man sich nicht für eine Position entscheidet, für die man zwar keine rationalen Gründe, aber immer noch Gründe anzuführen vermag, dann handelt es sich, wie Jünger ja auch selbst gesehen hat, um reinen Nihilismus. Ob man diesen Nihilismus als Stadium des Übergangs begreift oder nicht, mit einer konservativen Haltung ist diese Position nicht mehr in Einklang zu bringen.

Antihistorismus

Im September 1929 erschien in dem von Leopold Schwarzschild herausgegebenen linksliberalen Tagebuch ein Aufsatz Jüngers, in dem seine Stellung zum Konservatismus besonders deutlich wird. Jünger war von Schwarzschild aufgefordert worden, seine Position darzustellen. Unmittelbarer Anlaß waren die Attentate der Landvolkbewegung, die in der Presse heftig diskutiert wurden.

Jünger wurde vorgestellt als "unbestrittener geistiger Führer" des jungen Nationalismus, für den "sogar Hugenberg, Hitler und die Kommunisten reaktionäre Spießbürger" (S. 788) sind. Jünger stellte klar, daß sein Nationalismus mit dem "Konservativismus" nicht "das mindeste zu schaffen" habe (S. 504, vgl. S. 218). 40 Seine Kritik an der parlamentarischen Demokratie trifft jeden, der sich nicht außerhalb der Ordnung des bestehenden Systems stellt. Letztlich sind ihm alle revolutionären Kräfte innerhalb eines Staates unsichtbare Verbündete (S. 506). Zerstörung sei daher das einzig angemessene Mittel: "Weil wir die echten, wahren und unerbittlichen Feinde des Bürgers sind, macht uns seine Verwesung Spaß" (S. 507). 41

Der Aufsatz im Tagebuch löste eine rege Diskussion um Jüngers Standort aus. Wenige Monate später, im Januar 1930, nahm Jünger in Niekischs Widerstand dazu Stellung ( Schlußwort zu einem Aufsatze): Die "Wendung zur Anarchie" habe sich "endgültig im Jahr 1927" vollzogen, zunächst sei sie jedoch nur "im kleinsten Kreis" zur Sprache gekommen.

Vor mir liegen meine Briefbände aus diesem Jahr, die mit Ausführungen gespickt sind über das, was wir damals den Nihilismus nannten, und dem wir morgen vielleicht wieder einen anderen Namen geben werden - vielleicht sogar den des Konservativismus, wenn es uns Vergnügen macht. Denn Chaos und Ordnung besitzen eine engere Verwandtschaft als mancher Glauben mag. (S. 541) 42

In einem der Briefe, aus denen Jünger zwei längere Passagen zitiert, heißt es, "wir" seien "als Glieder einer Generation vorläufig nur echt", "als wir durch den Nihilismus hindurchgehen und unseren Glauben noch nicht formulieren" (S. 542f.). Jünger kommentiert: Diesen Gedankengängen liege das Bestreben zu Grunde, "das Sein von allen Gewordenen Gebilden zu lösen, um es tieferen und furchtbareren Gewalten anzuvertrauen – solchen, die nicht das Opfer, sondern die Triebkräfte der Katastrophe sind" (S. 543).

Was Jünger und seinem Kreis vorschwebte war also ein radikaler Bruch mit der geschichtlichen Überlieferung überhaupt. Aus der Sicht des deutschen Konservatismus kann man nicht antikonservativer eingestellt sein. Jünger war sich dieses Antikonservatismus vollends bewußt, indem er ihm einen anderen Konservatismus gegenüberstellte:

Die Ursprünglichkeit des Konservativen zeichnet sich dadurch aus, daß sie sehr alt, die des Revolutionärs, daß sie sehr jung sein muß. Die Konservativen von heute sind aber fast ohne Ausnahme erst hundert Jahre alt. [...] Mit anderen Worten: Der Bannkreis des Liberalismus hat größere Reichweite, als man im allgemeinen glaubt, und fast jede Auseinandersetzung vollzieht sich innerhalb seines Umkreises. (S. 589)

In den Aufsätzen des Jahres 1930 manifestierte sich der antihistoristische Affekt weiter. 43 Im Mai 1930 schrieb Jünger:

Unser Gesellschaftsgefühl ist anarchisch. [...] Überall offenbart sich das Streben nach neuer Ordnung, nach Schaffung neuer, im besten Sinne männlicher Werte. Eine Evolution aber ist unmöglich! Nur die kommende, die mit zwingender Gewalt kommende Revolution kann Besserung bringen. [...] Erst aus den Tiefpunkten kulturpolitischer Falschwirtschaft wird sich – gemäß des ehernen Gesetzes der Weltgeschichte – bei uns der Aufstieg vollziehen! (S. 583)

Bestimmt man die >Konservative Revolution< als den radikalen Versuch, das, was traditionell in Deutschland Konservatismus genannt wird, unter den Bedingungen einer antikonservativen Zeit wieder zu beleben, so kann Jünger nach 1926 eigentlich nicht mehr zur >Konservativen Revolution< gezählt werden.

Für Mohler, der einen ungeschichtlichen, eher anthropologischen Konservatismusbegriff zu Grunde legt, bietet Jüngers Denken um 1929 jedoch beinahe den Idealtyp der >Konservativen Revolution<. In einer Hinsicht bleibt jedoch eine Spannung. Die Absage an jede geschichtliche Überlieferung bedeutet auch eine Absage an Geschichtsphilosophie. Jünger bleibt jedoch durch seinen Hang zur Idee dem geschichtsphilosophischen Denken in einem wesentlichen Punkt verhaftet. 44

Die Edition

Zum Schluß noch einige Bemerkungen zu der von Sven Berggötz besorgten Edition. Leider haben sich in die Texte Jüngers einige Fehler eingeschlichen. Bei der Edition eines Klassikers ist dies besonders ärgerlich.

An einigen Stellen störte sich Berggötz an Jüngers Grammatik und griff in den Text ein. Einen Autor vom Format Jüngers bei der Bildung eines Genitivs zu korrigieren, ist eigentlich überflüssig.

Einige der Texteingriffe sind jedoch unbegreiflich. Sie zeigen, wie fremd dem Herausgeber das Denken Jüngers geblieben ist. Natürlich meint Jünger in der folgend angeführten Passage "das Arbeiten der Idee" und nicht ein "Arbeiten an einer Idee". Ideen sind für Jünger überpersönliche Mächte: "Denn was jetzt in allen Völkern vor sich geht, ist das Arbeiten [an] einer universalen Idee" (S. 262).

Weshalb es in der folgenden Passage "Tugend" heißen soll, wie Berggötz in seinem Kommentar vermutet (S. 770), ist ebenfalls nicht einzusehen: "Es bedürfte dieser Aufforderung nicht, denn ich betrachte mich überall als Mitkämpfer, wo man mit jener stillen Entschiedenheit, in der ich die für unsere Zeit notwendigste Jugend [sic] erblicke, an der Rüstung ist" (S. 449f.). Unverständlich ist auch, weshalb die wenigen Fußnoten Jüngers sich nicht in den Texten Jüngers, sondern in den Kommentaren finden.

In den Kommentaren finden sich zwar viele interessante und hilfreiche Erläuterungen, einige Kommentare provozieren jedoch Kritik. In einem Kommentar zum "Fundamentalsatze des Descartes" (S. 503) heißt es, das "ich denke, also bin ich" sei "der erste absolut gewisse Grundsatz, mit dem Descartes die Wende der neuzeitlichen Philosophie zum Sein begründete" (S. 710). Einmal ganz abgesehen davon, daß ein Kommentar zu Descartes' "Fundamentalsatz" vezichtbar wäre: Mit gleichem Recht könnte es auch heißen, der Satz begründe die Wende zum Bewußtsein.

Ein anderes Beispiel: Eine Bemerkung Jüngers über Keyserlings Reisetagebuch eines Philosophen (S. 160) kommentiert Berggötz mit dem Hinweis, Thomas Mann hätte das Buch für die Frankfurter Zeitung rezensieren sollen. Nun weiß der Leser, daß sich Berggötz auch für Thomas Mann interessiert. Für das Verständnis von Jüngers Text ist dieser Kommentar unerheblich.

Viele eindeutige Anspielungen und Zitate blieben hingegen unkommentiert. Nicht wo sich Goethes Wendung "alles Vergängliche ist nur ein Gleichnis" findet, sondern wo Rathenau gesagt hat, daß die Weltgeschichte ihren Sinn verloren hätte, "wenn die Repräsentanten des Reiches als Sieger durch das Brandenburger Tor in die Hauptstadt eingezogen wären" (S. 575), möchte man gerne erfahren.

Matthias Schloßberger, M.A.

Universität Potsdam

Institut für Philosophie

Praktische Philosophie / Philosophische Anthropologie

Am Neuen Palais, Haus 11

D - 14469 Potsdam

Homepage

Copyright © by the author. All rights reserved.

This work may be copied for non-profit educational use if proper credit is given to the author and IASLonline.

For other permission, please contact IASLonline.

Diese Rezension wurde betreut von unserem Fachreferenten PD Dr. Alf Christophersen. Sie finden den Text auch angezeigt im Portal Lirez – Literaturwissenschaftliche Rezensionen.

Dans Lolita, ni femme ni culture. Seule une gamine de douze ans et l’Amérique des motels qui défile le long des routes. L’histoire en elle-même et le scandale qu’elle suscita n’apparaissent finalement que comme secondaires si l’on songe que le roman existait déjà en substance quinze ans plus tôt, sous le titre de L’Enchanteur, que Nabokov n’avait pas publié mais dont il reprend de très près la trame. Dans les deux œuvres, l’auteur insiste sur le caractère déterminant de la mère de la fillette, tantôt gravement malade et inspirant la pitié, tantôt vulgaire et ignare, suscitant le dégoût du narrateur autant que celui du lecteur. Lorsqu’il paraît, le roman reçoit de manière immédiate et étonnamment évidente le qualificatif de « littérature américaine ». En réalité, il s’agit là de bien davantage qu’un simple symbole, puisque c’est l’achèvement du détachement absolu des personnages de leurs origines culturelles, la rupture définitive avec la Russie amoureusement méprisée ou douloureusement regrettée et paradoxalement, dans l’évolution du style de Nabokov, du point culminant où les personnages, pourtant sans réelles profondeur et texture historiques, se donnent à voir dans leur plus complexe richesse. « Je suis le chien fidèle de la nature. Pourquoi alors ce sentiment d’horreur dont je ne puis me défaire ? », s’interroge Humbert Humbert, incapable d’aimer les femmes, mais torturé par l’amour d’une fillette.

Dans Lolita, ni femme ni culture. Seule une gamine de douze ans et l’Amérique des motels qui défile le long des routes. L’histoire en elle-même et le scandale qu’elle suscita n’apparaissent finalement que comme secondaires si l’on songe que le roman existait déjà en substance quinze ans plus tôt, sous le titre de L’Enchanteur, que Nabokov n’avait pas publié mais dont il reprend de très près la trame. Dans les deux œuvres, l’auteur insiste sur le caractère déterminant de la mère de la fillette, tantôt gravement malade et inspirant la pitié, tantôt vulgaire et ignare, suscitant le dégoût du narrateur autant que celui du lecteur. Lorsqu’il paraît, le roman reçoit de manière immédiate et étonnamment évidente le qualificatif de « littérature américaine ». En réalité, il s’agit là de bien davantage qu’un simple symbole, puisque c’est l’achèvement du détachement absolu des personnages de leurs origines culturelles, la rupture définitive avec la Russie amoureusement méprisée ou douloureusement regrettée et paradoxalement, dans l’évolution du style de Nabokov, du point culminant où les personnages, pourtant sans réelles profondeur et texture historiques, se donnent à voir dans leur plus complexe richesse. « Je suis le chien fidèle de la nature. Pourquoi alors ce sentiment d’horreur dont je ne puis me défaire ? », s’interroge Humbert Humbert, incapable d’aimer les femmes, mais torturé par l’amour d’une fillette.

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

Lichtmesz: Vielen Dank an Herr Ladurner, dass er an diesen wichtigen Roman erinnert hat, der besonders die Leser der ZEIT erfreuen wird, wobei mir scheint, dass er nicht viel nachgedacht hat, als er

Lichtmesz: Vielen Dank an Herr Ladurner, dass er an diesen wichtigen Roman erinnert hat, der besonders die Leser der ZEIT erfreuen wird, wobei mir scheint, dass er nicht viel nachgedacht hat, als er

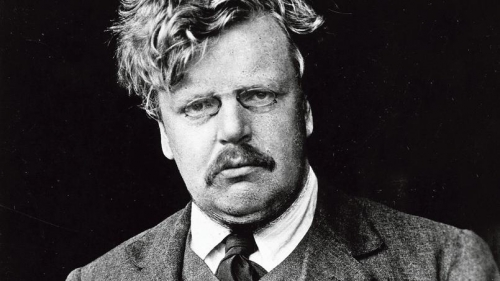

Enfant, Gilbert aime la fiction merveilleuse. Elle "sert d'antidote aux monstres cauchemardesques qui l'empêchent souvent de dormir mais qu'il tente d'exorciser avec ses dessins." Aussi, avant de lire Walter Scott, Thackeray et Dickens, aura-t-il lu MacDonald, Charles Kingsley et Barrie.

Enfant, Gilbert aime la fiction merveilleuse. Elle "sert d'antidote aux monstres cauchemardesques qui l'empêchent souvent de dormir mais qu'il tente d'exorciser avec ses dessins." Aussi, avant de lire Walter Scott, Thackeray et Dickens, aura-t-il lu MacDonald, Charles Kingsley et Barrie.

Aus der nicht eben abwechslungsarmen österreichischen Literaturlandschaft ragt Robert (von) Musils Mann ohne Eigenschaften als markanter Gipfel heraus. Mit diesem umfangreichen Werk schrieb der promovierte Philosoph sich in die Literaturgeschichte ein. Der unvollendet gebliebene Roman nahm fast 20 Jahre Arbeitszeit in Anspruch und zehrte Musils ganze Schaffenskraft auf. Daneben blieb sein Œuvre schmal. Die

Aus der nicht eben abwechslungsarmen österreichischen Literaturlandschaft ragt Robert (von) Musils Mann ohne Eigenschaften als markanter Gipfel heraus. Mit diesem umfangreichen Werk schrieb der promovierte Philosoph sich in die Literaturgeschichte ein. Der unvollendet gebliebene Roman nahm fast 20 Jahre Arbeitszeit in Anspruch und zehrte Musils ganze Schaffenskraft auf. Daneben blieb sein Œuvre schmal. Die  Alle in dem Band veröffentlichten Texte wurden bereits veröffentlicht, so daß der Musil-Kenner keine Sensationen zu erwarten hat. Auch die Nachbemerkung des Herausgebers ist mit zwei Seiten äußerst kurz; ein Nachwort mit Erläuterungen zur Entstehungsgeschichte der Texte wäre angesichts ihrer stark differierenden Entstehungszeiten, Themen und auch gedanklichen Ansätze hilfreich gewesen.

Alle in dem Band veröffentlichten Texte wurden bereits veröffentlicht, so daß der Musil-Kenner keine Sensationen zu erwarten hat. Auch die Nachbemerkung des Herausgebers ist mit zwei Seiten äußerst kurz; ein Nachwort mit Erläuterungen zur Entstehungsgeschichte der Texte wäre angesichts ihrer stark differierenden Entstehungszeiten, Themen und auch gedanklichen Ansätze hilfreich gewesen.

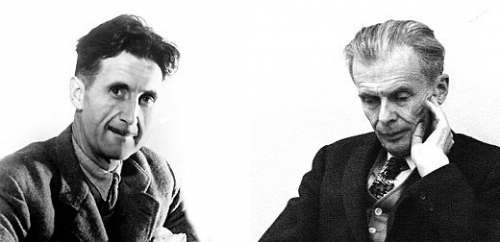

Orwell opened a door for all to see a “nightmarish future” in which everyday life becomes harsh, an object of state surveillance, and control—a society in which the slogan “ignorance becomes strength” morphs into a guiding principle of mainstream media, education, and the culture of politics. Huxley shared Orwell’s concern about ignorance as a political tool of the elite, enforced through surveillance and the banning of books, dissent, and critical thought itself. But Huxley, believed that social control and the propagation of ignorance would be introduced by those in power through the political tools of pleasure and distraction. Huxley thought this might take place through drugs and genetic engineering, but the real drugs and social planning of late modernity lies in the presence of an entertainment and public pedagogy industry that trades in pleasure and idiocy, most evident in the merging of neoliberalism, celebrity culture, and the control of commanding cultural apparatuses extending from Hollywood movies and video games to mainstream television, news, and the social media.

Orwell opened a door for all to see a “nightmarish future” in which everyday life becomes harsh, an object of state surveillance, and control—a society in which the slogan “ignorance becomes strength” morphs into a guiding principle of mainstream media, education, and the culture of politics. Huxley shared Orwell’s concern about ignorance as a political tool of the elite, enforced through surveillance and the banning of books, dissent, and critical thought itself. But Huxley, believed that social control and the propagation of ignorance would be introduced by those in power through the political tools of pleasure and distraction. Huxley thought this might take place through drugs and genetic engineering, but the real drugs and social planning of late modernity lies in the presence of an entertainment and public pedagogy industry that trades in pleasure and idiocy, most evident in the merging of neoliberalism, celebrity culture, and the control of commanding cultural apparatuses extending from Hollywood movies and video games to mainstream television, news, and the social media. At the same time, Orwell’s warning about “Big Brother” applies not simply to an authoritarian-surveillance state but also to commanding financial institutions and corporations who have made diverse modes of surveillance a ubiquitous feature of daily life. Corporations use the new technologies to track spending habits and collect data points from social media so as to provide us with consumer goods that match our desires, employ face recognition technologies to alert store salesperson to our credit ratings, and so it goes. Heidi Boghosian points out that if omniscient state control in Orwell’s 1984 is embodied by the two-way television sets present in each home, then in “our own modern adaptation, it is symbolized by the location-tracking cell phones we willingly carry in our pockets and the microchip-embedded clothes we wear on our bodies.”

At the same time, Orwell’s warning about “Big Brother” applies not simply to an authoritarian-surveillance state but also to commanding financial institutions and corporations who have made diverse modes of surveillance a ubiquitous feature of daily life. Corporations use the new technologies to track spending habits and collect data points from social media so as to provide us with consumer goods that match our desires, employ face recognition technologies to alert store salesperson to our credit ratings, and so it goes. Heidi Boghosian points out that if omniscient state control in Orwell’s 1984 is embodied by the two-way television sets present in each home, then in “our own modern adaptation, it is symbolized by the location-tracking cell phones we willingly carry in our pockets and the microchip-embedded clothes we wear on our bodies.” Relentlessly entertained by spectacles, people become not only numb to violence and cruelty but begin to identify with an authoritarian worldview. As David Graeber suggests, the police “become the almost obsessive objects of imaginative identification in popular culture… watching movies, or viewing TV shows that invite them to look at the world from a police point of view.”

Relentlessly entertained by spectacles, people become not only numb to violence and cruelty but begin to identify with an authoritarian worldview. As David Graeber suggests, the police “become the almost obsessive objects of imaginative identification in popular culture… watching movies, or viewing TV shows that invite them to look at the world from a police point of view.” Another egregious example of neoliberalism’s Orwellian assault on higher education can be found in the policies promoted by the Republican Party members who control the North Carolina Board of Governors. Just recently it has decimated higher education in that state by voting to cut 46 degree programs. One member defended such cuts with the comment: “We’re capitalists, and we have to look at what the demand is, and we have to respond to the demand.”

Another egregious example of neoliberalism’s Orwellian assault on higher education can be found in the policies promoted by the Republican Party members who control the North Carolina Board of Governors. Just recently it has decimated higher education in that state by voting to cut 46 degree programs. One member defended such cuts with the comment: “We’re capitalists, and we have to look at what the demand is, and we have to respond to the demand.” Hay un reclamo persistente en Drieu: “Voces falsarias y hueras me han acusado de que mi posición surge de un adaptarme a las formas políticas que se proyectan como victoriosas, en este momento de la guerra y que serían las dominantes en el futuro, todo ello es falso”

Hay un reclamo persistente en Drieu: “Voces falsarias y hueras me han acusado de que mi posición surge de un adaptarme a las formas políticas que se proyectan como victoriosas, en este momento de la guerra y que serían las dominantes en el futuro, todo ello es falso” Sobre el particular apunta Drieu: “Me he convencido de que Guénon anuncia, con el lenguaje cifrado propio de la Tradición sagrada de los pueblos, que se aproxima un cambio drástico en la valoración de los hombres y en el sentido de la vida; en ello he visto a las nuevas fuerzas que se alzan contra los dogmas, al parecer inamovibles, de una civilización basada en el dinero, el materialismo y en formas políticas caducas”.

Sobre el particular apunta Drieu: “Me he convencido de que Guénon anuncia, con el lenguaje cifrado propio de la Tradición sagrada de los pueblos, que se aproxima un cambio drástico en la valoración de los hombres y en el sentido de la vida; en ello he visto a las nuevas fuerzas que se alzan contra los dogmas, al parecer inamovibles, de una civilización basada en el dinero, el materialismo y en formas políticas caducas”.

Influencé par Nietzsche et Carlyle, Maurice Spronck publie en 1894 une contre-utopie (ou dystopie). Thomas More, Francis Bacon, Tommaso Campanella pariaient sur l’avenir ou l’onirisme pour élaborer des systèmes politiques et sociaux parfaits dans lesquels les êtres humains s’épanouiraient harmonieusement au contraire de la dystopie popularisée par les écrivains de science-fiction et d’anticipation (Eugène Zamiatine, écrivain de Nous autres, Aldous Huxley dans Le meilleur des mondes, George Orwell avec 1984, René Barjavel pour Ravage, Ray Bradbury et son Fahrenheit 451). L’an 330 de la République fait de Maurice Spronck un étonnant précurseur.

Influencé par Nietzsche et Carlyle, Maurice Spronck publie en 1894 une contre-utopie (ou dystopie). Thomas More, Francis Bacon, Tommaso Campanella pariaient sur l’avenir ou l’onirisme pour élaborer des systèmes politiques et sociaux parfaits dans lesquels les êtres humains s’épanouiraient harmonieusement au contraire de la dystopie popularisée par les écrivains de science-fiction et d’anticipation (Eugène Zamiatine, écrivain de Nous autres, Aldous Huxley dans Le meilleur des mondes, George Orwell avec 1984, René Barjavel pour Ravage, Ray Bradbury et son Fahrenheit 451). L’an 330 de la République fait de Maurice Spronck un étonnant précurseur.

1922 erscheint Der Kampf als inneres Erlebnis und die zweite Auflage von In Stahlgewittern, 1923 im Hannoverschen Kurier in 16 Folgen die Erzählung Sturm, 1924 und 1925 Das Wäldchen 125. Eine Chronik aus den Grabenkämpfen und Feuer und Blut. Ein kleiner Ausschnitt aus einer großen Schlacht. Die erste Phase seines Werkes, in dem Jünger seine Fronterlebnisse verarbeitete, ist damit abgeschlossen. Das Jahr 1925 bedeutet für Jünger in vielerlei Hinsicht eine Zäsur. Zehn Jahre lang – bis zu den Afrikanischen Spielen von 1936 – wird Jünger keine Erzählungen und Romane veröffentlichen.

1922 erscheint Der Kampf als inneres Erlebnis und die zweite Auflage von In Stahlgewittern, 1923 im Hannoverschen Kurier in 16 Folgen die Erzählung Sturm, 1924 und 1925 Das Wäldchen 125. Eine Chronik aus den Grabenkämpfen und Feuer und Blut. Ein kleiner Ausschnitt aus einer großen Schlacht. Die erste Phase seines Werkes, in dem Jünger seine Fronterlebnisse verarbeitete, ist damit abgeschlossen. Das Jahr 1925 bedeutet für Jünger in vielerlei Hinsicht eine Zäsur. Zehn Jahre lang – bis zu den Afrikanischen Spielen von 1936 – wird Jünger keine Erzählungen und Romane veröffentlichen. Mit dem Ende des Kaiserreichs verbindet Jünger die Überwindung einer materialistischen Naturanschauung, der individualistischen Idee allgemeiner Menschenrechte und des bloßen Strebens nach materiellem Wohlstand.

Mit dem Ende des Kaiserreichs verbindet Jünger die Überwindung einer materialistischen Naturanschauung, der individualistischen Idee allgemeiner Menschenrechte und des bloßen Strebens nach materiellem Wohlstand.

Es sind erstens die personellen Verbindungen zu betrachten. Sie können Zeichen sein für ein gemeinsames Arbeiten an gemeinsamen Zielen, auch wenn in letzter Instanz die Ziele nicht die gleichen sind. Zweitens sind die konkreten politischen Positionen zu untersuchen und zu vergleichen. Und drittens ist nach Gemeinsamkeiten der Denkstile, der Denkfiguren, der Mentalität zu suchen.

Es sind erstens die personellen Verbindungen zu betrachten. Sie können Zeichen sein für ein gemeinsames Arbeiten an gemeinsamen Zielen, auch wenn in letzter Instanz die Ziele nicht die gleichen sind. Zweitens sind die konkreten politischen Positionen zu untersuchen und zu vergleichen. Und drittens ist nach Gemeinsamkeiten der Denkstile, der Denkfiguren, der Mentalität zu suchen. Bestimmend bleibt auch die Bedeutung der Idee: "Nach neuen Zielen verlangt unser Blut, es fordert Ideen, an denen es sich berauschen, Bewegungen, in denen es sich erschöpfen und Opfer, durch die es sich selbst verleugnen kann" (S. 196).

Bestimmend bleibt auch die Bedeutung der Idee: "Nach neuen Zielen verlangt unser Blut, es fordert Ideen, an denen es sich berauschen, Bewegungen, in denen es sich erschöpfen und Opfer, durch die es sich selbst verleugnen kann" (S. 196).

What sticks in memory from both books after lo! these many years, with scarcely a return dip in the meantime, is a miasma of filth, poor sanitation—in the trenches, in the slums, everywhere. (Curiously, Céline’s first book, his doctoral thesis in fact, was a biography of Ignaz Semmelweis[6], the father of obstetric antisepsis.) The obsessive disgust is very similar to the first part of Orwell’s Down and Out in Paris and London, which was written about the same time, so one author is unlikely to have influenced the other. Orwell was aware of Céline in the 1930s, since he mentions him in his essay on Henry Miller; but only just barely.

What sticks in memory from both books after lo! these many years, with scarcely a return dip in the meantime, is a miasma of filth, poor sanitation—in the trenches, in the slums, everywhere. (Curiously, Céline’s first book, his doctoral thesis in fact, was a biography of Ignaz Semmelweis[6], the father of obstetric antisepsis.) The obsessive disgust is very similar to the first part of Orwell’s Down and Out in Paris and London, which was written about the same time, so one author is unlikely to have influenced the other. Orwell was aware of Céline in the 1930s, since he mentions him in his essay on Henry Miller; but only just barely.

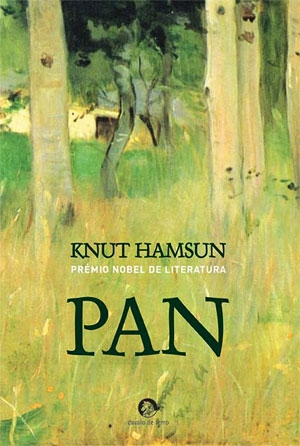

Bien plus qu’un roman social traitant de la misère et de l’errance d’un homme dans une capitale européenne qui lui est totalement inconnue, La Faim est un roman psychologique qui met son narrateur en face d’un alter-ego, compagne ambiguë, qu’il entretient pour cultiver l’inspiration nécessaire à son travail littéraire : « J’avais remarqué très nettement que si je jeûnais pendant une période assez longue, c’était comme si mon cerveau coulait tout doucement de ma tête et la laissait vide. » Ce personnage parcourt le roman en équilibre, entre moments de génie et d’éclat, entre tortures physiques et mentales. Il écrit ainsi: « Dieu avait fourré son doigt dans le réseau de mes nerfs et discrètement, en passant, il avait un peu embrouillé les fils… » Ce personnage ambivalent permet à Hamsun d’évoquer ses propres névroses et d’annoncer un autre objectif de sa vie : l’esthétique de la langue. Il n’aura de cesse de la travailler, parfois avec fièvre. Kristofer Janson, poète et prêtre qui a connu Hamsun, dit ne connaître « personne aussi maladivement obsédé par l’esthétique verbale que lui […]. Il pouvait sauter de joie et se gorger toute une journée de l’originalité d’un adjectif descriptif lu dans un livre ou qu’il avait trouvé lui-même ». Dans La Faim, le personnage entretient un rapport imprévisible et tumultueux à l’écriture : « On aurait dit qu’une veine avait éclaté en moi, les mots se suivent, s’organisent en ensembles, constituent des situations ; les scènes s’accumulent, actions et répliques s’amoncellent dans mon cerveau et je suis saisi d’un merveilleux bien-être. J’écris comme un possédé, je remplis page sur page sans un instant de répit. […] Cela continue à faire irruption en moi, je suis tout plein de mon sujet et chacun des mots que j’écris m’est comme dicté. » Son premier roman inaugure donc un travail sur l’esthétique de la langue. Auparavant, Hamsun parlait un norvégien encore « bâtard », paysan, et assez éloigné du norvégien bourgeois de la capitale. C’est probablement ce à quoi il pensait en écrivant dans un article de 1888 : « Le langage doit couvrir toutes les gammes de la musique. Le poète doit toujours, dans toutes les situations, trouver le mot qui vibre, qui me parle, qui peut blesser mon âme jusqu’au sanglot par sa précision. Le verbe peut se métamorphoser en couleur, en son, en odeur ; c’est à l’artiste de l’employer pour faire mouche […] Il faut se rouler dans les mots, s’en repaître ; il faut connaître la force directe, mais aussi secrète du Verbe […] Il existe des cordes à haute et basse résonance, et il existe des harmoniques… »

Bien plus qu’un roman social traitant de la misère et de l’errance d’un homme dans une capitale européenne qui lui est totalement inconnue, La Faim est un roman psychologique qui met son narrateur en face d’un alter-ego, compagne ambiguë, qu’il entretient pour cultiver l’inspiration nécessaire à son travail littéraire : « J’avais remarqué très nettement que si je jeûnais pendant une période assez longue, c’était comme si mon cerveau coulait tout doucement de ma tête et la laissait vide. » Ce personnage parcourt le roman en équilibre, entre moments de génie et d’éclat, entre tortures physiques et mentales. Il écrit ainsi: « Dieu avait fourré son doigt dans le réseau de mes nerfs et discrètement, en passant, il avait un peu embrouillé les fils… » Ce personnage ambivalent permet à Hamsun d’évoquer ses propres névroses et d’annoncer un autre objectif de sa vie : l’esthétique de la langue. Il n’aura de cesse de la travailler, parfois avec fièvre. Kristofer Janson, poète et prêtre qui a connu Hamsun, dit ne connaître « personne aussi maladivement obsédé par l’esthétique verbale que lui […]. Il pouvait sauter de joie et se gorger toute une journée de l’originalité d’un adjectif descriptif lu dans un livre ou qu’il avait trouvé lui-même ». Dans La Faim, le personnage entretient un rapport imprévisible et tumultueux à l’écriture : « On aurait dit qu’une veine avait éclaté en moi, les mots se suivent, s’organisent en ensembles, constituent des situations ; les scènes s’accumulent, actions et répliques s’amoncellent dans mon cerveau et je suis saisi d’un merveilleux bien-être. J’écris comme un possédé, je remplis page sur page sans un instant de répit. […] Cela continue à faire irruption en moi, je suis tout plein de mon sujet et chacun des mots que j’écris m’est comme dicté. » Son premier roman inaugure donc un travail sur l’esthétique de la langue. Auparavant, Hamsun parlait un norvégien encore « bâtard », paysan, et assez éloigné du norvégien bourgeois de la capitale. C’est probablement ce à quoi il pensait en écrivant dans un article de 1888 : « Le langage doit couvrir toutes les gammes de la musique. Le poète doit toujours, dans toutes les situations, trouver le mot qui vibre, qui me parle, qui peut blesser mon âme jusqu’au sanglot par sa précision. Le verbe peut se métamorphoser en couleur, en son, en odeur ; c’est à l’artiste de l’employer pour faire mouche […] Il faut se rouler dans les mots, s’en repaître ; il faut connaître la force directe, mais aussi secrète du Verbe […] Il existe des cordes à haute et basse résonance, et il existe des harmoniques… »

Di recente è uscita una sua biografia a firma di Antonio Serena, Drieu aristocratico e giacobino, per i tipi della Settimo Sigillo, nota casa editrice di estrema destra. Tuttavia è doveroso strappare questo cattivo maestro alle opposte tifoserie politiche per consegnarlo al posto che merita. Pierre Drieu la Rochelle, nato nel 1893 a Parigi in una famiglia piccolo borghese e nazionalista di antica fede napoleonica, è uno dei figli migliori della generazione perduta. E’ vissuto tra le due guerre: è stato ferito nella prima e si è tolto la vita sul finire della seconda, per l’esattezza il 15 marzo 1945, dopo aver ingerito una dose letale di Fenobarbital. Tutto ciò che lo riguarda, come letterato e come uomo, è accaduto durante quella pace “fatua” andata in scena a Parigi tra le due guerre. Amico di Louis Aragon e André Malraux, dei dadaisti e dei surrealisti, dandy delle serate alla moda, marito fallimentare, amante di donne piacenti e ricche, Drieu in fondo è passato nel secolo breve senza legarsi ad alcuno, fedele alla sua spietata coerenza.