Rédacteur en chef de la revue Le Débat, le philosophe Marcel Gauchet est l’auteur d’ouvrages majeurs de la pensée contemporaine: Le Désenchantement du monde, L’Avènement de la démocratie ou plus récemment, Robespierre, l’homme qui nous divise le plus.

Dans cet entretien, il dresse le constat d’une Union européenne qui, faute de stratégie politique, se montre incapable de répondre à la déstabilisation identitaire engendrée par la mondialisation et par l’émergence de nouveaux rapports de force à l’échelle mondiale.

Le Grand Continent : Vous portez un discours assez critique vis-à-vis de l’Union européenne. Que lui reprochez-vous ? Pensez-vous qu’elle affaiblit les États nations ?

Marcel Gauchet : Je crois que c’est une mauvaise manière de prendre le problème que de se focaliser sur l’affaiblissement des États-nations. Il faut parler du résultat global du processus. S’il y avait affaiblissement des États-nations au profit de la collectivité des États-nations réunis dans l’Union européenne, il s’agirait d’un indéniable succès politique.

La bonne question est celle de l’efficacité globale du processus européen. La construction européenne promettait une efficacité supérieure à celle des États-nations, or, tel qu’elle fonctionne aujourd’hui, l’Union européenne affaiblit la créativité européenne en général, plus encore qu’elle n’affaiblit les États-nations en tant que tels. Qu’est-ce que l’Europe ? Le continent de l’invention de la modernité – politique, intellectuelle et scientifique, économique et technique (1) . Je sais que c’est pécher par « eurocentrisme » que de le rappeler, mais je n’ai pas de complexe à braver cette fatwa grotesque. Le problème fondamental de l’Europe est celui de sa capacité à continuer de contribuer à cette invention devenue désormais un bien commun planétaire, au-delà des catastrophes suicidaires du XXe siècle Or il me semble que l’Union européenne, loin de relever ce défi, a anesthésié ce qui a été le ressort de cette créativité, à savoir la dialectique de la coopération et de la concurrence entre les nations qui la composent. Voilà la critique majeure qu’on peut lui faire.

Le vice fondamental de l’Union européenne est d’avoir construit une entité apolitique et a-stratégique.

Le problème de l’Union européenne est l’inversion de l’idée selon laquelle l’union fait la force. Or je dirais, dans le cas précis : l’union fait la faiblesse. Et ce sur tous les plans.

Le problème de l’Union européenne est l’inversion de l’idée selon laquelle l’union fait la force. Or je dirais, dans le cas précis : l’union fait la faiblesse. Et ce sur tous les plans.

Le vice fondamental de l’Union européenne est d’avoir construit une entité apolitique et a-stratégique, qui ne permet pas aux Européens de se situer dans le monde. Je précise que la dimension stratégique n’implique pas nécessairement une dimension militaire. La puissance aujourd’hui n’a plus primordialement un sens militaire. La puissance militaire des États-Unis ne lui sert pas à grand chose, on pourrait même soutenir qu’elle est devenue contre-productive, en revanche les dépenses militaires américaines servent à fabriquer une industrie très puissante. Le keynésianisme militaire américain est très efficace ! Cela éclaire une autre erreur stratégique des Européens, qui se sont empressés d’empocher après 1991 les dividendes de la paix, en sacrifiant leurs dépenses militaires. Pendant ce temps, on voit que les dépenses militaires américaines, avec leurs ramifications multiples, ont servi à fabriquer une industrie numérique, qui est aujourd’hui le vrai secret de la puissance américaine. En la matière, les européens ont complètement raté le coche, faute d’une réflexion stratégique, et c’est une des raisons de leur affaiblissement durable.

L’un des échecs de l’Union européenne est justement d’avoir été incapable, au moment de l’effondrement de l’URSS, de définir une stratégie vis-à-vis de l’Europe de l’Est.

Dans cette perspective, que pensez-vous du projet d’armée européenne défendu par Emmanuel Macron ?

C’est une erreur politique grossière, en plus d’un vœu inconsistant ! Aujourd’hui, l’affichage de cette volonté de créer une armée européenne revient à entrer dans le jeu américain, qui consiste à faire de Poutine le repoussoir qui justifie des dépenses militaires servant à tout autre chose qu’à des buts militaires. Certes, dans l’abstrait, on ne peut que soutenir l’idée que les européens doivent être capables de se défendre par leurs propres moyens . Mais en pratique à quoi servirait cette armée européenne ? Nous ne sommes pas menacés par la Turquie ou par les pays du Maghreb ! Le seul adversaire sérieux serait éventuellement la Russie, mais est-il réaliste de la regarder comme une menace militaire directe ?

L’un des échecs de l’Union européenne est justement d’avoir été incapable, au moment de l’effondrement de l’URSS, de définir une stratégie vis-à-vis de l’Europe de l’Est. On a laissé faire les Américains, qui ont multiplié les erreurs, alors qu’il s’agissait de notre voisinage vital vis-à-vis duquel nous devions arrêter une ligne de conduite claire. Les États-Unis sont et doivent demeurer des alliés, mais cela ne doit pas empêcher les Européens de développer une réflexion indépendante sur leur environnement et leurs priorités, et de faire valoir leurs conclusions auprès de leur grand allié. Au lieu de quoi les Européens se laissent passivement mener par les États-Unis, qui poursuivent des buts qui leurs sont propres.

« Ce n’est pas l’Europe qui a bâti la paix, mais l’inverse : l’Europe s’est bâtie grâce à la paix assurée par la Guerre froide » écrivez-vous dans Comprendre le malheur français. Vous semblez ainsi remettre en question l’idée, chère aux europhiles, selon laquelle l’Union serait un rempart contre les conflits armés.

Cette idée est une vulgate propagandiste d’une telle absurdité historique que sa longévité me stupéfie. Soyons sérieux : une possible guerre européenne aurait concerné trois pays : la France, le Royaume-Uni et l’Allemagne. Or de 1945 à 1948, aucune de ces trois nations n’était en mesure de mener une guerre quelconque, avec une armée américaine omniprésente et une armée rouge stationnant à trois cents kilomètres de Strasbourg.

Je ne suis pas sûr que sans la Guerre froide l’impératif de la construction européenne aurait eu la même vigueur.

Avec la guerre froide, cette pression s’est encore accentuée. Même en imaginant un retour sur le devant de la scène politique de bellicistes, qui n’étaient pas au rendez-vous, et pour cause, comment auraient-ils pu mener une guerre ? Le projet européen est d’abord bâti comme un moyen de résister à l’URSS en renforçant la cohésion de l’Ouest. Un des points trop souvent oubliés est le rôle majeur des États-Unis dans la construction européenne. Le plan Marshall n’était pas un geste philanthropique et désintéressé des Américains. Il avait une finalité très précise : renforcer l’Europe de l’Ouest à un moment où elle semblait menacée. La paix s’imposait donc aux Européens. Dans l’ensemble, ils étaient alignés sur les États-Unis, et il était parfaitement raisonnable de l’être. Il y avait une évidence stratégique du renforcement de l’Union à l’intérieur de l’OTAN.

Avec la guerre froide, cette pression s’est encore accentuée. Même en imaginant un retour sur le devant de la scène politique de bellicistes, qui n’étaient pas au rendez-vous, et pour cause, comment auraient-ils pu mener une guerre ? Le projet européen est d’abord bâti comme un moyen de résister à l’URSS en renforçant la cohésion de l’Ouest. Un des points trop souvent oubliés est le rôle majeur des États-Unis dans la construction européenne. Le plan Marshall n’était pas un geste philanthropique et désintéressé des Américains. Il avait une finalité très précise : renforcer l’Europe de l’Ouest à un moment où elle semblait menacée. La paix s’imposait donc aux Européens. Dans l’ensemble, ils étaient alignés sur les États-Unis, et il était parfaitement raisonnable de l’être. Il y avait une évidence stratégique du renforcement de l’Union à l’intérieur de l’OTAN.

C’est dans ce contexte qu’il faut comprendre la politique gaullienne ; Elle fut une tentative de desserrer l’étreinte que représentait la Guerre froide. Elle fut rendue possible seulement par les débuts de la Détente.

Je ne suis pas sûr que sans la Guerre froide l’impératif de la construction européenne aurait eu la même vigueur. Il n’aurait pas eu de ressort suffisant pour rompre avec les politiques institutionnelles propres à chaque pays.

Les nouveaux mouvements néo-nationalistes européens peuvent être définis comme des nationalistes internationalistes en ce qu’ils n’ont pas de visées expansionnistes, mais bien plutôt tissent des alliances avec leurs voisins. Pour ce faire, des pays comme la Hongrie s’appuient de plus en plus sur une rhétorique imprégnée de références eschatologiques. Quel regard portez-vous sur le renouveau de la spiritualité en politique ?

Premièrement, il y a une grande difficulté à définir une nébuleuse, elle-même très confuse. C’est une grande différence avec les totalitarismes du vingtième siècle, qui avaient une dimension idéologique très marquée, notamment le communisme.

Les « néo-nationalistes » appartiennent à des mouvements plus affectivo-identitaires que politiques […] Ils sont à peine politiques, au sens où ils sont plus réactifs que programmatiques.

Que dire sur le discours d’Orban ? C’est un potage démagogique qui agite classiquement des motivations très fortes : le sentiment d’un danger et la nécessité d’un pouvoir fort pour s’en défendre. C’est un discours décourageant sur le plan de l’analyse idéologique, mais qui met le doigt là où ça fait mal ! Il ne réussit pas par hasard. De manière générale, vos « néo-nationalistes » appartiennent à des mouvements plus affectivo-identitaires que politiques, au sens classique du terme, avec des programmes et des visées bien identifiables.

Deuxièmement, l’élément religieux que vous pointez existe effectivement à l’échelle globale, mais il concerne essentiellement le continent américain, avec l’électorat évangéliste. Quand Trump déplace l’ambassade américaine à Jérusalem, c’est pour plaire à une fraction bien déterminée de l’électorat. Plus largement, l’eschatologie est inscrite dans l’identité américaine avec l’idée de Destinée manifeste (2). Ce qui est nouveau, c’est la percée de l’eschatologie au sud du continent américain. Cette dimension pourrait jouer un rôle très important pour la suite, je n’en disconviens pas.

Le christianisme d’Orban me semble beaucoup moins eschatologique qu’identitaire.

En revanche, quand Orban parle de la Hongrie chrétienne, son christianisme me semble beaucoup moins eschatologique qu’identitaire. La perspective qu’il mobilise, c’est la défense de la culture chrétienne contre la culture musulmane. Tous les électeurs comprennent que quand on parle de culture chrétienne, on parle d’une culture sans-les-musulmans ! Si vous parlez d’eschatologie aux électeurs de Salvini, je doute même qu’ils sachent de quoi il est question.

En revanche, quand Orban parle de la Hongrie chrétienne, son christianisme me semble beaucoup moins eschatologique qu’identitaire. La perspective qu’il mobilise, c’est la défense de la culture chrétienne contre la culture musulmane. Tous les électeurs comprennent que quand on parle de culture chrétienne, on parle d’une culture sans-les-musulmans ! Si vous parlez d’eschatologie aux électeurs de Salvini, je doute même qu’ils sachent de quoi il est question.

En somme, il me semble que les mouvements « néo-nationalistes » sont à peine politiques, au sens où ils sont plus réactifs que programmatiques. Trump et Bolsonaro n’ont pas de projet, mais réagissent à une situation, la globalisation, avec ses traductions locales particulières.

La déstabilisation identitaire provoquée par la mondialisation est un ressort tout à fait nouveau qui est le vrai cœur des mouvements qualifiés un peu vite de populistes.

La mondialisation constitue un double défi identitaire pour l’ensemble des sociétés du monde, plus ou moins ressenti selon le degré de cohésion identitaire et culturel qu’elles ont. En effet, elle les oblige à se définir par rapport à l’extérieur comme elles n’ont jamais eu à le faire dans le passé. La réponse à la question : « qui sommes-nous ? » passait essentiellement par l’histoire, par l’héritage, par la continuité d’une tradition et dans une moindre mesure par la comparaison avec ses voisins immédiats. Cette réponse classique est balayée par l’inscription obligée dans une géographie globale. Cette exigence de redéfinition interne sous la pression de l’extérieur est un élément qui joue diversement selon le degré où les gens se sentent atteints dans leur définition traditionnelle.

Les ex-puissances coloniales ont une certaine habitude du monde. Pour des Hongrois ou des Polonais, en revanche, il s’agit d’un choc brutal. Même les États-Unis sont concernés, car s’ils jouent un rôle dans le monde depuis un siècle, ils l’ont toujours fait par projection à l’extérieur. Avec le 11 septembre, le monde arrive sur le sol américain. À la limite, au fond de l’Iowa on pouvait pratiquement ignorer qu’il y avait eu des guerres mondiales. En tout cas, si on le savait, cela ne faisait que conforter la définition interne de l’Amérique dans sa vocation providentielle. La nouveauté, c’est cette irruption du monde extérieur avec ce qu’elle appelle de redéfinition en profondeur.

Quand on parle de définition stratégique, cela ne concerne donc plus seulement des diplomates ou des militaires, mais n’importe qui œuvrant, en tant que citoyen, dans un champ culturel et politique. J’ajoute que dans cette mondialisation technico-économique il y a un phénomène d’uniformisation qui ébranle gravement les manières de faire locales. Elle introduit une norme très contraignante à tous les niveaux qui s’impose à tous les acteurs en rupture avec des coutumes, des façons de faire, de penser qui étaient très établies.

La déstabilisation identitaire provoquée par la mondialisation me paraît le grand facteur méconnu par la plupart des analyses politiques. On est là dans un ressort tout à fait nouveau qui est le vrai cœur de ces mouvements qualifiés un peu vite de populistes.

Vous parlez de puissances qui ne sont pas habituées au monde et qui vivent un bouleversement identitaire face à la globalisation. Dès lors, il peut sembler étonnant que le Royaume-Uni ait voté majoritairement le Brexit, alors même qu’il s’agit d’une puissance habituée au monde, par son empire passé, et son ouverture économique et culturelle internationale.

Le peuple anglais fait partie des quelques peuples politiques de la planète. Tous les peuples ne sont pas politiques, au sens où ils n’ont pas tous une forme de tradition historique, nourrie par une longue réflexion collective, sur la manière de se conduire à l’égard du monde extérieur. Or en la matière, la tradition anglaise est très déterminée : elle a consisté à tirer les ficelles de la politique continentale tout en se tenant à l’écart. Cette tradition a été ébranlée par les deux guerres mondiales mais elle reste ancrée profondément. Elle a encore présidé à l’entrée dans la communauté européenne, après une expectative prolongée. Elle y a très bien fonctionné, d’ailleurs, jusqu’à ce que l’inertie de la machine ne finisse par la digérer. D’où le réveil brutal le jour où cette absorption est devenue palpable. Le refus de se diluer dans une politique européenne collégiale me paraît le ressort fondamental pour comprendre la diversité des rejets qui se sont coalisés, des déclassés de Birmingham aux conservateurs les mieux nantis, dont on ne voit pas en quoi l’Union a pu les léser en quoi que ce soit !

L’appartenance à l’Union a ébranlé quelque chose de la vision que les Britanniques avaient d’eux-mêmes.

Une des erreurs d’analyse courante est de douter de leur sincérité et d’attribuer leur euroscepticisme à des manœuvres politiciennes. C’est ne pas voir comment l’appartenance à l’Union a fini par ébranler quelque chose de la vision qu’ils avaient d’eux-mêmes, surtout depuis son élargissement. Cette classe dominante avait l’habitude d’un monde qu’elle avait le sentiment de maîtriser et la voilà confrontée à un monde qui lui échappe, même si elle en profite.

Ne peut-on aussi penser que l’accueil des migrants a renforcé la méfiance contre l’Union européenne ?

C’est en effet un facteur qui a joué un rôle important, manifestement, mais pas forcément celui qu’on croit – la simple xénophobie. Il y a là une bizarrerie qui doit faire réfléchir. L’immigration ex coloniale ne posait de problèmes particuliers. Ce qui a posé un problème, ce sont les polonais ! Comment peut-il se faire que l’immigration polonaise, bien que plus proche géographiquement et culturellement que l’immigration pakistanaise ou indienne, ait représenté un défi plus grand pour les Britanniques ? C’est le signe que ce ne sont pas des spécificités culturelles inassimilables qui ont fait la question, mais le mécanisme politique non maîtrisé qui a présidé à cette immigration et la signification que cela lui a donné. Au contraire, quand on bâtit un empire, on conçoit que le contrôle de certaines régions entraîne en retour une certaine immigration.

Ce ne sont pas des spécificités culturelles inassimilables qui ont fait la question migratoire, mais le mécanisme politique non maîtrisé qui a présidé à cette immigration et la signification que cela lui a donné.

Faites-vous la même analyse concernant l’Union européenne ?

De manière générale, oui. Pour ses peuples, l’Union se présente comme un ensemble qui n’a aucun contrôle direct de son environnement direct, au Sud. L’absence de maîtrise de cet environnement est mise en évidence par des flux migratoires incontrôlés.

De manière générale, oui. Pour ses peuples, l’Union se présente comme un ensemble qui n’a aucun contrôle direct de son environnement direct, au Sud. L’absence de maîtrise de cet environnement est mise en évidence par des flux migratoires incontrôlés.

La population européenne représente 7 % de la population mondiale. Les Européens sont en train de se rendre compte confusément de la petitesse de leur « Grand continent », comme vous dites, à l’échelle globale. Ils sont comparativement très riches, mais leur poids relatif est mince et ils sont faibles. C’est un élément crucial de leur perception d’eux-mêmes et des perspectives que cela dessine quant à leur destin. Ajoutez-y cet élément culturel, qui prend les Européens à contre-pied par rapport à leur propre éloignement de la religion, que constitue l’effervescence de l’Islam et vous n’avez pas de peine à comprendre l’inquiétude qui les travaille. Le problème de l’Union, désormais, c’est qu’elle ne paraît pas faite pour répondre à cette inquiétude.

Pour ses peuples, l’Union se présente comme un ensemble qui n’a aucun contrôle direct de son environnement direct, au Sud.

L’Union s’est absorbée dans un processus interne alors que la demande des peuples, dans le contexte de la mondialisation, est, très logiquement, une demande de réponse à la pression de l’extérieur. Dans ce contexte-là, le libre-échange tel qu’il est conçu à Bruxelles et tel qu’il est pratiqué, apparaît comme un irénisme naïf. Non que des accords de libre-échange ne puissent être une arme stratégique de première importance. Encore faut-il qu’ils s’inscrivent dans un cadre intellectuel solidement pensé comme une manière de défendre et d’affirmer sa position dans le monde.

À terme les mouvements affectivo-identitaires ne risquent-ils pas de gagner sur les positionnements européistes ? Comment renverser la tendance, si ce n’est en développant, comme vous le suggérez, une vision stratégique de ce que doit être l’Union européenne ?

L’histoire est ouverte, mais si on continue sans rien faire, les mouvements affectivo-identitaires l’emporteront – encore qu’ils aient un problème de crédibilité politique évident – ou constitueront un facteur de blocage insurmontable, ce qui n’est pas beaucoup mieux. C’est une course de vitesse à beaucoup d’égards. Tout tient dans la réponse qu’on peut leur apporter. Je vous avoue que je suis tristement sceptique sur cette capacité : nous n’avons pas de dirigeants politiques qui ont une vraie conscience de ces enjeux, je ne vois pas dans la technocratie européenne telle qu’elle fonctionne des gens qui aient des idées sur la question. L’Europe est aussi tragiquement somnambulique en 2019 que ses milieux dirigeants pouvaient l’être en 1914.

Si on continue sans rien faire, les mouvements affectivo-identitaires l’emporteront ou constitueront un facteur de blocage insurmontable.

Je vous recommande le livre de Luuk Van Middelaar : Quand l’Europe improvise (3). C’est un livre passionnant mais accablant par rapport à cet autisme situation bureaucratique. Il le résume en disant en substance : « L’UE ne sait pratiquer qu’une politique de la règle, alors que ce qui lui est demandé est une politique de l’événement ». Ma différence avec lui, qui me rend plus pessimiste, serait que la politique de l’événement ne suffit pas. Elle se contente de faire face à des situations qui s’imposent, alors qu’une politique stratégique est celle qui permet d’anticiper ces événements et de parer à toute éventualité. A ce jour nous n’en avons aucune. Et je ne vois pas par quelles voies le Conseil des chefs d’État qui s’est imposé comme l’instance la moins inadéquate de riposte aux crises, Van Middelaar le montre bien, pourrait en élaborer une.

Je vous recommande le livre de Luuk Van Middelaar : Quand l’Europe improvise (3). C’est un livre passionnant mais accablant par rapport à cet autisme situation bureaucratique. Il le résume en disant en substance : « L’UE ne sait pratiquer qu’une politique de la règle, alors que ce qui lui est demandé est une politique de l’événement ». Ma différence avec lui, qui me rend plus pessimiste, serait que la politique de l’événement ne suffit pas. Elle se contente de faire face à des situations qui s’imposent, alors qu’une politique stratégique est celle qui permet d’anticiper ces événements et de parer à toute éventualité. A ce jour nous n’en avons aucune. Et je ne vois pas par quelles voies le Conseil des chefs d’État qui s’est imposé comme l’instance la moins inadéquate de riposte aux crises, Van Middelaar le montre bien, pourrait en élaborer une.

Ce qui est un peu vivant en Europe, ce sont les mouvements protestataires. Mais sur l’Europe ils sont prisonniers d’une contradiction paralysante. Les politiques redistributives qu’ils préconisent supposent pour être acceptées un cadre politique arrêté et reconnu. Or, leur idéologie universaliste s’oppose à la définition d’un tel cadre. Ce qui fait que c’est le plus petit dénominateur commun qui l’emporte : un petit peu de social, un petit peu d’Europe mais pas trop. Le statu quo l’emporte de tous les côtés.

Il y a eu en Europe l’invention d’un modèle politique, social, intellectuel et culturel préférable à celui qui règne partout ailleurs dans le monde : c’est ce que pense l’immense majorité des Européens, mais ils n’ont pas le droit de le dire !

« On a inventé la modernité », dîtes-vous. Pourquoi ne pas mettre en avant, pour renforcer notre soft power, l’invention de la démocratie libérale, afin de faire (re)naître une forme d’orgueil européen ?

Ce devrait être en effet notre ligne de conduite. Mais cette histoire n’est pas assumée par les Européens, ou du moins par leurs élites. C’est la folie de la situation que nous connaissons. Le discours académique dominant s’emploie en sens inverse à dénoncer l’eurocentrisme et son prolongement pratique, la domination coloniale. Ce n’est pas ce que l’Europe a fait de plus glorieux, c’est évident – mais le visage de notre passé qui en épuise le sens.

Qu’il y ait une invention de la modernité, d’un modèle politique, social, intellectuel et culturel préférable à celui qui règne partout ailleurs dans le monde, c’est ce que pense l’immense majorité des Européens in petto, mais ils n’ont pas le droit de le dire ! Il s’agit pourtant d’un sentiment sur lequel il serait essentiel de s’appuyer, si l’on souhaitait mener une construction européenne vivante. Qui sommes-nous ? Certainement plus les maîtres du monde ! Au fond, tout le monde est très content de ne plus l’être. Personne ne rêve de recommencer la grande aventure impérialiste. Tout cela est derrière nous. Mais il y a un legs de notre histoire qui est tout à fait avouable et dont le sens d’une construction européenne digne de ce nom serait de le porter à un plus grand degré d’achèvement.

Il faut trouver une manière d’assumer cette qualité spécifique de l’invention européenne, dont les Européens n’ont pas à rougir, en commençant par nouer un rapport critique intelligent avec le passé. Ce rapport des Européens à leur histoire, c’est en quelque sorte le vrai défi, car c’est la clef de la réponse à la question « Qui sommes-nous par rapport au reste du monde ? ».

C’est sur cette base là que l’on pourrait, par exemple, développer une vraie politique d’accueil, en sachant ce qu’on veut obtenir dans cet accueil, en ayant à l’esprit des raisons d’accueillir. Ce n’est pas seulement parce que nous disposons d’un niveau de vie par habitant plus élevé que nous devons accueillir des réfugiés. Si l’on commence à réfléchir de la sorte, on est rapidement entraîné à mettre les victimes en concurrence : les défavorisés de chez nous contre les défavorisés de la planète. On ne s’en sort pas ! En revanche, si le sens collectif de l’accueil est déterminé par une fierté civique, pourquoi pas ? Cela change tout : nous savons que c’est un comportement sensé d’avoir envie de venir chez nous et de s’y installer pour contribuer à cette qualité européenne, et pas simplement pour venir profiter des allocations familiales ou d’un cadre économique plus favorable.

Les défenseurs d’une politique d’accueil élargie invoquent régulièrement les droits de l’homme. Or, vous êtes assez critique des droits de l’homme, dès lors qu’on essaie de les ériger en une politique (4). Pouvez-vous développer ce thème ?

Droits de l’homme et politique : toute la question est celle de l’alliance des deux termes et du passage de l’un à l’autre. Je ne suis pas critique à l’égard de l’idée des droits de l’homme en elle-même. La question porte sur les conditions de leur utilisation et de leur application : qu’en fait-on ? J’ai assez écrit sur lesdits droits de l’homme pour qu’on ne me suspecte pas de penser qu’il y a mieux à côté ! Qu’on les aime ou non, il faut faire avec. C’est le principe de légitimité inventé par la modernité et qui est en train de devenir planétaire. J’ai bien dit : en train.

Droits de l’homme et politique : toute la question est celle de l’alliance des deux termes et du passage de l’un à l’autre. Je ne suis pas critique à l’égard de l’idée des droits de l’homme en elle-même. La question porte sur les conditions de leur utilisation et de leur application : qu’en fait-on ? J’ai assez écrit sur lesdits droits de l’homme pour qu’on ne me suspecte pas de penser qu’il y a mieux à côté ! Qu’on les aime ou non, il faut faire avec. C’est le principe de légitimité inventé par la modernité et qui est en train de devenir planétaire. J’ai bien dit : en train.

Les droits de l’homme sont le principe de légitimité qui se substitue au principe de légitimité religieux : c’est le cœur de l’invention européenne.

Si j’ai consacré beaucoup de temps à cette problématique des droits de l’homme, c’est d’abord pour identifier ce qu’elle représente et ce qui s’y joue. Le grand problème des droits de l’homme, c’est que ceux qui s’en réclament avec le plus de véhémence ne s’interrogent pas sur ce qu’ils veulent dire, sur ce qu’est leur fonction. Les droits de l’homme sont le principe de légitimité qui se substitue au principe de légitimité religieux : c’est le cœur de l’invention européenne (5).

Puisque les droits de l’homme sont la source du pouvoir au sein des États européens, ne suffit-il pas de les respecter pour mettre en oeuvre une politique cohérente ?

Les droits de l’homme peuvent-ils à eux seuls fournir la clef de construction d’une cité juste ? L’histoire et l’analyse me semblent établir que non, car les droits de l’homme sont faits pour s’appliquer à une matière politique et à une réalité sociale qui leur est hétérogène. Le problème politique de nos régimes, dès lors, réside dans la composition de ces impératifs distincts. C’est là le vrai pluralisme des sociétés modernes. Il y a le principe de légitimité, il y a un cadre politique dont on voit bien qu’il ne répond pas spontanément, de manière nécessaire, aux dits droits de l’homme. S’enfermer dans la politique des droits de l’homme, c’est s’interdire de penser ce qu’il y a en-dehors d’eux, qui conditionne pourtant leur expression.

Peut-on honnêtement espérer retrouver la maîtrise de l’économie par un programme tiré des droits de l’homme ?

L’économie est un élément de cette politique, elle est même devenue son principal objet, puisque l’économie a pris le pas sur la politique. Le problème de la politique est de retrouver la maîtrise sur l’économie. Peut-on honnêtement espérer retrouver la maîtrise de l’économie par un programme tiré des droits de l’homme ? Il définira à la rigueur l’objectif, et encore, mais certainement pas les moyens. Les normes d’efficacité du monde économique sont extrinsèques à la problématique des droits de l’homme. Elles ont leur parfaite justification dans leur ordre, une économie se doit d’être efficace ou elle est dépourvue de sens. Le problème est l’ajustement de ces réalités : comment rendre le salariat compatible avec les droits des individus, qui sont par principe menacés dans la relation salariale. Mais on voit bien qu’il ne peut y avoir d’économie sans organisation hiérarchique au sein des entreprises. Donc il faut trouver les moyens de rendre compatible la structure de commandement que suppose une entreprise avec le respect de la dignité de ses salariés.

Le problème est analogue dans le champ politique avec la structure de commandement qu’est un État, qu’il s’agit d’ajuster avec l’impératif de liberté des citoyens. Or la politique des droits de l’homme escamote ce problème en posant comme postulat que tout doit s’aligner ou découler dans la vie collective de ses normes premières. Certes, elles sont une indispensable source de légitimité mais elles ne définissent pas le cadre politique. Au nom des droits de l’homme, comment voulez-vous justifier la représentation politique ? Si l’on pose au départ des individus également libres, pourquoi certains auraient-ils plus de capacités normatives que d’autres ? C’est insoluble. De la même façon, les droits de l’homme permettent-ils de choisir un système électoral, dont on sait pourtant qu’il est la pièce déterminante d’un régime ? Pourquoi plutôt la proportionnelle ou le scrutin majoritaire ? La réponse est d’un autre ordre.

L’enjeu de la question des droits de l’homme est de circonscrire leur domaine d’application et de comprendre la fonction qu’ils jouent, ce qu’on peut en tirer et comment s’en servir. C’est cette démarche nécessaire que la notion de politique des droits de l’homme escamote complètement.

Propos recueillis par Pierre Ramond et Uriel Gadessaud.

Suite à lire sur : Le Grand Continent, Pierre Ramond et Uriel Gadessaud, 06-02-2019

NOTES

1. Marcel Gauchet définit la modernité européenne comme le passage à la structuration sociale autonome, en fonction du processus de sortie de la religion et de la structuration hétéronome à laquelle elle est associée. Lire « Pourquoi l’avènement de la démocratie ? », Le Débat, n°193 (2017)

2. Dans le contexte de la sécession texane du Mexique puis de son rattachement aux Etats-Unis en 1845, à la fin du mandat de John Tyler, le journaliste John O’Sullivan publie un article dans le Democratic review où il défend l’idée d’une “Destinée manifeste”. Une vingtaine d’années après la doctrine Monroe (1823), il réaffirme le lien unissant les Etats-Unis et le continent américain. Elus par Dieu, les premiers auraient pour mission de s’étendre sur le continent américain pour y implanter leurs institutions.

3. Luuke Van Middelaar, Quand l’Europe improvise, Gallimard, 2018. Lire aussi Dieter Grimm « L’Europe par le droit: jusqu’où », Le Débat, n°187 (2015) et Dieter Grimm « Quand le juge dissout l’électeur », Le Monde diplomatique (juillet 2017)

4. Lire « Les Droits de l’homme ne sont pas une politique », Le Débat, n°3 (1980) et « Quand les droits de l’homme deviennent une politique », Le Débat, n°110 (2000)

5. Ici, Marcel Gauchet s’intéresse à la religion non comme croyance individuelle mais comme mode de structuration des communautés humaines fondées sur l’hétéronomie, ou pour ainsi dire, déterminées du dehors. Parler de « fin de la religion » revient alors non à postuler l’avènement d’un monde sans croyant, mais l’émergence de sociétés fonctionnant en dehors du religieux comme principe régulateur, dans un double mouvement d’autonomisation de l’ici-bas et d’internalisation de l’au-delà. Lire « Fin de la religion » , Le Débat, n°28 (1984).

Nous vous proposons cet article afin d'élargir votre champ de réflexion. Cela ne signifie pas forcément que nous approuvions la vision développée ici. Dans tous les cas, notre responsabilité s'arrête aux propos que nous reportons ici. [Lire plus]

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

It may be Nock’s “

It may be Nock’s “

Je lis Michael Snyder et son blog apocalyptique depuis des années et je fais donc attention chaque fois qu’à la télévision on montre des images de la vie quotidienne en Amérique. Or de petits films sur mes espagnols à travers le monde démontrent qu’effectivement les conditions de vie aux USA sont devenues sinistres et hors de prix, sans qu’on puisse évoquer la poétique de Blade runner…Plusieurs amis fortunés qui font aussi des allers et retours et m’ont confirmé que le vieil oncle Sam coûte bien cher, comme Paris, Londres et des milliers d’endroits (même se loger en Bolivie devient un exploit, vive Morales-Bolivar-Chavez…), pour ce qu’il offre ; d’autres amis moins fortunés, universitaires, survivent durement. Car il y a en plus les persécutions politiques qui gagent nos si bienveillantes démocraties…

Je lis Michael Snyder et son blog apocalyptique depuis des années et je fais donc attention chaque fois qu’à la télévision on montre des images de la vie quotidienne en Amérique. Or de petits films sur mes espagnols à travers le monde démontrent qu’effectivement les conditions de vie aux USA sont devenues sinistres et hors de prix, sans qu’on puisse évoquer la poétique de Blade runner…Plusieurs amis fortunés qui font aussi des allers et retours et m’ont confirmé que le vieil oncle Sam coûte bien cher, comme Paris, Londres et des milliers d’endroits (même se loger en Bolivie devient un exploit, vive Morales-Bolivar-Chavez…), pour ce qu’il offre ; d’autres amis moins fortunés, universitaires, survivent durement. Car il y a en plus les persécutions politiques qui gagent nos si bienveillantes démocraties… En vérité les gens supporteraient tout (« l’homme s’habitue à tout », dixit Dostoïevski dans la maison des morts), mais le problème est que cette m… au quotidien est hors de prix ! Donc…

En vérité les gens supporteraient tout (« l’homme s’habitue à tout », dixit Dostoïevski dans la maison des morts), mais le problème est que cette m… au quotidien est hors de prix ! Donc… Les impôts pleuvent comme en France :

Les impôts pleuvent comme en France :

On reprend donc Raskolnikoff dans ces pages immortelles :

On reprend donc Raskolnikoff dans ces pages immortelles : « En un mot, je démontre que non seulement les grands hommes, mais tous ceux qui sortent tant soit peu de l’ornière, tous ceux qui sont capables de dire quelque chose de nouveau, même pas grand-chose, doivent, de par leur nature, être nécessairement plus ou moins des criminels. »

« En un mot, je démontre que non seulement les grands hommes, mais tous ceux qui sortent tant soit peu de l’ornière, tous ceux qui sont capables de dire quelque chose de nouveau, même pas grand-chose, doivent, de par leur nature, être nécessairement plus ou moins des criminels. »

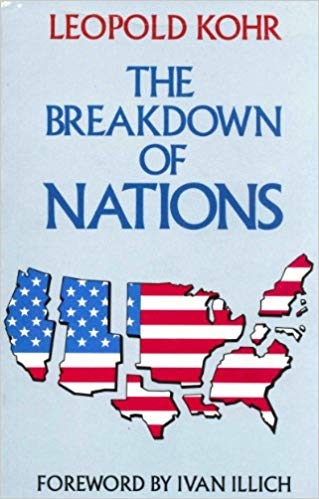

Une chaîne d’information en continu, afin de tenir l’antenne pendant des heures, doit créer de nouvelles formes de discours, inventer des méthodes de remplissage contraires à toute logique proportionnelle, pour reprendre le concept essentiel de Leopold Kohr. Nous appelons encore aujourd’hui information ou journalisme des discours et des pratiques récemment apparus à partir d’un certain seuil critique. Au-delà de ce seuil s’opère une réversion. L’information de masse, diffusée en continu, en direct, ce babille incontinent de discours incapables de faire retour sur eux-mêmes, de s’entendre, se transforme en désinformation de masse. Le journalisme, sommé de capter tous les bruits du monde, de faire droit aux moindres insignifiances, de tout accueillir pour ne rien rater, de se brancher sur tous les flux, s’effondre sous les données qu’il amasse aléatoirement. Toujours grossir, tel est l’adage de la modernité tardive. Augmenter sa taille, accroître sa diffusion, saturer les écrans, envahir les étals. Jusqu’au collapse. A une certaine échelle de taille, plus rien n’est possible. Il en va de même pour le discours critique qui a besoin, pour se déployer, d’être protégé de l’inflation, de se tenir en-deçà de toute masse critique, de créer son propre écosystème.

Une chaîne d’information en continu, afin de tenir l’antenne pendant des heures, doit créer de nouvelles formes de discours, inventer des méthodes de remplissage contraires à toute logique proportionnelle, pour reprendre le concept essentiel de Leopold Kohr. Nous appelons encore aujourd’hui information ou journalisme des discours et des pratiques récemment apparus à partir d’un certain seuil critique. Au-delà de ce seuil s’opère une réversion. L’information de masse, diffusée en continu, en direct, ce babille incontinent de discours incapables de faire retour sur eux-mêmes, de s’entendre, se transforme en désinformation de masse. Le journalisme, sommé de capter tous les bruits du monde, de faire droit aux moindres insignifiances, de tout accueillir pour ne rien rater, de se brancher sur tous les flux, s’effondre sous les données qu’il amasse aléatoirement. Toujours grossir, tel est l’adage de la modernité tardive. Augmenter sa taille, accroître sa diffusion, saturer les écrans, envahir les étals. Jusqu’au collapse. A une certaine échelle de taille, plus rien n’est possible. Il en va de même pour le discours critique qui a besoin, pour se déployer, d’être protégé de l’inflation, de se tenir en-deçà de toute masse critique, de créer son propre écosystème. Leopold Kohr cite Jonathan Swift : « on observe que plus les créatures humaines sont corpulentes, plus elles sont sauvages et cruelles en proportion. » Cette corpulence doit être comprise comme la métaphore d’une disproportion qui s’accroit avec l’accumulation tératologique des capitaux des uns, de la misère économique, culturelle et symbolique des autres. Cette tendance s’accompagne d’un retrait progressif de la contestation. En face d’une force sans partage, dont on sait qu’elle nous écrasera plutôt que de se limiter en reconnaissant sa limite, « la force du désaccord humain, de l’esprit critique, montre une tendance proportionnelle à décroitre tout aussi naturellement » remarque Leopold Kohr. Il attribue cette tendance, cette sensibilité décroissante, à une sorte d’instinct, à l’intérêt pour notre propre survie. Cet intérêt s’accompagne « d’un engourdissement moral adapté aux situations ». Paradoxalement, au-lieu de se révolter contre l’accumulation d’injustices, impuissant à agir face à un géant qui le piétine, « l’être humain ordinaire, ajoute Leopold Kohr, est plutôt enclin à perdre le peu de conscience qui lui restait quand les victimes n’étaient pas encore trop nombreuses. » Cette structure défensive transforme l’être humain ordinaire en un simple spectateur de ce qui lui arrive. Il contemple la démesure, sidéré, préférant renoncer à l’esprit critique plutôt que d’éprouver dans sa chair la réalité de son impuissance.

Leopold Kohr cite Jonathan Swift : « on observe que plus les créatures humaines sont corpulentes, plus elles sont sauvages et cruelles en proportion. » Cette corpulence doit être comprise comme la métaphore d’une disproportion qui s’accroit avec l’accumulation tératologique des capitaux des uns, de la misère économique, culturelle et symbolique des autres. Cette tendance s’accompagne d’un retrait progressif de la contestation. En face d’une force sans partage, dont on sait qu’elle nous écrasera plutôt que de se limiter en reconnaissant sa limite, « la force du désaccord humain, de l’esprit critique, montre une tendance proportionnelle à décroitre tout aussi naturellement » remarque Leopold Kohr. Il attribue cette tendance, cette sensibilité décroissante, à une sorte d’instinct, à l’intérêt pour notre propre survie. Cet intérêt s’accompagne « d’un engourdissement moral adapté aux situations ». Paradoxalement, au-lieu de se révolter contre l’accumulation d’injustices, impuissant à agir face à un géant qui le piétine, « l’être humain ordinaire, ajoute Leopold Kohr, est plutôt enclin à perdre le peu de conscience qui lui restait quand les victimes n’étaient pas encore trop nombreuses. » Cette structure défensive transforme l’être humain ordinaire en un simple spectateur de ce qui lui arrive. Il contemple la démesure, sidéré, préférant renoncer à l’esprit critique plutôt que d’éprouver dans sa chair la réalité de son impuissance.

Comme toute guerre, celle dans laquelle nous sommes engagés sans réserve nécessite une mobilisation totale. Et comme toujours dans l’histoire, les porteurs de vérité sont peu nombreux. Ils assument le rôle d’avant-garde sur le front intellectuel, portant la responsabilité morale d’une élite authentique pour guider leur nation vers l’objectif consistant à se libérer du joug de ce nouveau type d’impérialisme extraterritorial. Lucien Cerise défie fermement toutes les limitations imposées par la dictature du politiquement correct. Il parvient à détruire jusque dans les moindres détails le fonctionnement du Système dans ses dimensions géopolitique, militaire, économique, culturelle, éducative et médiatique. L’enjeu de cette guerre totale est sans précédent dans l’histoire de l’humanité puisqu’il s’agit, ni plus ni moins, de sauver l’espèce humaine de son extinction.

Comme toute guerre, celle dans laquelle nous sommes engagés sans réserve nécessite une mobilisation totale. Et comme toujours dans l’histoire, les porteurs de vérité sont peu nombreux. Ils assument le rôle d’avant-garde sur le front intellectuel, portant la responsabilité morale d’une élite authentique pour guider leur nation vers l’objectif consistant à se libérer du joug de ce nouveau type d’impérialisme extraterritorial. Lucien Cerise défie fermement toutes les limitations imposées par la dictature du politiquement correct. Il parvient à détruire jusque dans les moindres détails le fonctionnement du Système dans ses dimensions géopolitique, militaire, économique, culturelle, éducative et médiatique. L’enjeu de cette guerre totale est sans précédent dans l’histoire de l’humanité puisqu’il s’agit, ni plus ni moins, de sauver l’espèce humaine de son extinction.  Dans notre cas, cela évoque l’exacerbation maladive des obsessions et des traumatismes des communautés roumanophone et russophone en nourrissant des représentations catastrophiques sur certaines périodes historiques. L’une des parties du conflit occupe la place de la victime, et l’autre partie a le rôle de bourreau, chacune des parties ayant sur sa propre identité une perception narcissique en symétrie inversée dans une structure duelle où les rôles bourreau-victime sont interchangeables. Ainsi, le sentiment de frustration suscité par une injustice réelle ou imaginaire se transforme en une soif de vengeance par annihilation du groupe bourreau, associé au mal absolu. Ce procédé d’ingénierie sociale négative connaît un succès majeur en République de Moldavie en raison de la rivalité d’influence entre la Russie et la Roumanie sur notre territoire, historiquement explicable, mais contre-productive et exploitée avec perversité à l’heure actuelle. Par conséquence, les russophiles qui sont obligatoirement roumanophobes se confrontent avec les roumanophiles qui sont par définition russophobes, les moldovenistes sont en guerre avec les unionistes identitaires, et cela dure depuis des décennies. Et les efforts d’éclaircissements sur le caractère stérile de cette guerre d’identité sans fin sont rejetés avec agressivité et dans l’opacité totale. Qui profite de cette bataille absurde de deux camps également perdants ? Il existe deux niveaux d’acteurs gagnants qui restent plus ou moins dissimulés.

Dans notre cas, cela évoque l’exacerbation maladive des obsessions et des traumatismes des communautés roumanophone et russophone en nourrissant des représentations catastrophiques sur certaines périodes historiques. L’une des parties du conflit occupe la place de la victime, et l’autre partie a le rôle de bourreau, chacune des parties ayant sur sa propre identité une perception narcissique en symétrie inversée dans une structure duelle où les rôles bourreau-victime sont interchangeables. Ainsi, le sentiment de frustration suscité par une injustice réelle ou imaginaire se transforme en une soif de vengeance par annihilation du groupe bourreau, associé au mal absolu. Ce procédé d’ingénierie sociale négative connaît un succès majeur en République de Moldavie en raison de la rivalité d’influence entre la Russie et la Roumanie sur notre territoire, historiquement explicable, mais contre-productive et exploitée avec perversité à l’heure actuelle. Par conséquence, les russophiles qui sont obligatoirement roumanophobes se confrontent avec les roumanophiles qui sont par définition russophobes, les moldovenistes sont en guerre avec les unionistes identitaires, et cela dure depuis des décennies. Et les efforts d’éclaircissements sur le caractère stérile de cette guerre d’identité sans fin sont rejetés avec agressivité et dans l’opacité totale. Qui profite de cette bataille absurde de deux camps également perdants ? Il existe deux niveaux d’acteurs gagnants qui restent plus ou moins dissimulés.

« Les Argonautes ont fait tomber la première barrière et ce premier écroulement a provoqué de proche en proche la chute de toutes les barrières qui séparaient les peuples les uns des autres, le monde civilisé du monde barbare, le cosmos de tous les au-delà, merveilleux ou épouvantables. »

« Les Argonautes ont fait tomber la première barrière et ce premier écroulement a provoqué de proche en proche la chute de toutes les barrières qui séparaient les peuples les uns des autres, le monde civilisé du monde barbare, le cosmos de tous les au-delà, merveilleux ou épouvantables. »

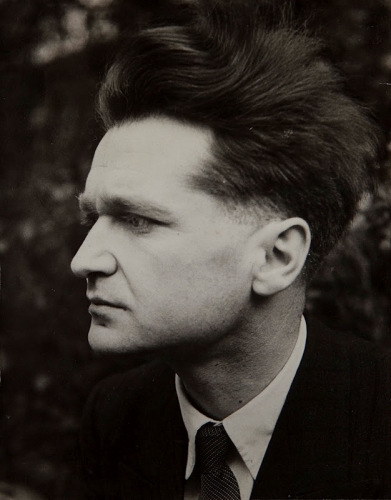

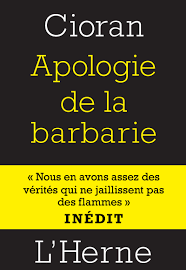

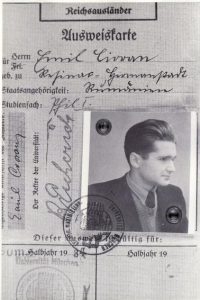

Emil Cioran

Emil Cioran A rare and stimulating combination in Cioran’s writings: unsentimental observation and intense pathos.

A rare and stimulating combination in Cioran’s writings: unsentimental observation and intense pathos. But fascism cannot work miracles. Politics must work with the human material and historical trajectory that one has. That is being true to oneself. To wish for total transformation and the tabula rasa is to invite disaster. Such revolutions are generally an exercise in self-harm. Once the passions and intoxications have settled, one finds the nation stunted and lessened: by civil war, by tyranny, by self-mutilation and deformation in the stubborn in the name of utopian goals. The historic gap with the ‘advanced’ nations is widened further still by the ordeal.

But fascism cannot work miracles. Politics must work with the human material and historical trajectory that one has. That is being true to oneself. To wish for total transformation and the tabula rasa is to invite disaster. Such revolutions are generally an exercise in self-harm. Once the passions and intoxications have settled, one finds the nation stunted and lessened: by civil war, by tyranny, by self-mutilation and deformation in the stubborn in the name of utopian goals. The historic gap with the ‘advanced’ nations is widened further still by the ordeal.

Mais permettez-moi de citer deux passages de The Benedict Option :

Mais permettez-moi de citer deux passages de The Benedict Option :

René Girard a parlé de l’Amérique comme puissance mimétique. Sur cette planète de crétins en effet tout le monde veut devenir américain, y compris quand il s’agit de payer des études à quarante mille euros/an, des opérations à 200 000 euros, de devenir obèse et même abruti par la consommation de médias et d’opiacés...

René Girard a parlé de l’Amérique comme puissance mimétique. Sur cette planète de crétins en effet tout le monde veut devenir américain, y compris quand il s’agit de payer des études à quarante mille euros/an, des opérations à 200 000 euros, de devenir obèse et même abruti par la consommation de médias et d’opiacés... Le cinéaste Tim Burton a bien moqué ce comportement homogénéisé/industriel dans plusieurs de ses films, par exemple Edouard aux mains d’argent. Kazan avait fait de même dans l’Arrangement. Aujourd’hui ce comportement monolithique/industriel s’applique à l’humanitaire, à la déviance, à la marginalité, au transsexualisme, au tatouage, au piercing, etc.

Le cinéaste Tim Burton a bien moqué ce comportement homogénéisé/industriel dans plusieurs de ses films, par exemple Edouard aux mains d’argent. Kazan avait fait de même dans l’Arrangement. Aujourd’hui ce comportement monolithique/industriel s’applique à l’humanitaire, à la déviance, à la marginalité, au transsexualisme, au tatouage, au piercing, etc.  La musique est rarement entendue en Amérique, ayant été remplacée par le battement de tambour sans culture du noir. Comme le dit un musicologue américain: «Le rythme du jazz, tiré de tribus sauvages, est à la fois raffiné et élémentaire et correspond aux dispositions de notre âme moderne. Cela nous excite sans répit, comme le battement de tambour primitif du danseur de la prière. Mais il ne s'arrête pas là. Il doit en même temps tenir compte de l'excitabilité de la psyché moderne. Nous avons soif de stimuli rapides, excitants et en constante évolution. La musique est un excellent moyen d’excitation, syncopé, qui a fait ses preuves. »

La musique est rarement entendue en Amérique, ayant été remplacée par le battement de tambour sans culture du noir. Comme le dit un musicologue américain: «Le rythme du jazz, tiré de tribus sauvages, est à la fois raffiné et élémentaire et correspond aux dispositions de notre âme moderne. Cela nous excite sans répit, comme le battement de tambour primitif du danseur de la prière. Mais il ne s'arrête pas là. Il doit en même temps tenir compte de l'excitabilité de la psyché moderne. Nous avons soif de stimuli rapides, excitants et en constante évolution. La musique est un excellent moyen d’excitation, syncopé, qui a fait ses preuves. »

Le progrès, une idéologie d’avenir ?

Le progrès, une idéologie d’avenir ? La société multiculturelle était l’avenir ; elle abolit les frontières ; elle ne connaît la diversité qu’individuelle, et elle nous promet la paix et l’amitié entre tous les hommes unis par le commerce. Ils ne formeront plus des peuples, mais une humanité dans laquelle tous font valoir les mêmes droits, partagent les mêmes désirs, bref, deviennent les mêmes. La croissance allait sauver le monde ; la Chine marchait vers la démocratie à mesure que le bol de riz se remplissait. Le droit et le marché en avaient fini avec la politique ; la puissance, la souveraineté, la Nation, autant de vestiges à mettre au grenier. Ajoutons que le monde est à nous, que nous nous levons chaque matin pour tout changer, que tous les milliardaires du monde n’aspirent qu’à construire un monde meilleur, et que la liberté oublieuse du passé assure que chacune, que chacun se construise lui-même un avenir radieux.

La société multiculturelle était l’avenir ; elle abolit les frontières ; elle ne connaît la diversité qu’individuelle, et elle nous promet la paix et l’amitié entre tous les hommes unis par le commerce. Ils ne formeront plus des peuples, mais une humanité dans laquelle tous font valoir les mêmes droits, partagent les mêmes désirs, bref, deviennent les mêmes. La croissance allait sauver le monde ; la Chine marchait vers la démocratie à mesure que le bol de riz se remplissait. Le droit et le marché en avaient fini avec la politique ; la puissance, la souveraineté, la Nation, autant de vestiges à mettre au grenier. Ajoutons que le monde est à nous, que nous nous levons chaque matin pour tout changer, que tous les milliardaires du monde n’aspirent qu’à construire un monde meilleur, et que la liberté oublieuse du passé assure que chacune, que chacun se construise lui-même un avenir radieux. L’avenir a changé de sens, et le progrès est l’inverse de ce qu’une politique française entêtée, aveugle et autiste, fait subir aux Français. Partout, l’État Nation est la forme politique de la modernité, et partout, les États Nations cherchent à affirmer leur unité interne, pour mieux faire face aux défis extérieurs qui se multiplient. Partout, la frontière retrouve sa fonction vitale ; faire le tri entre ce qui vient de l’extérieur, qui est utile, choisi, et qui entre, et ce qui est dangereux, toxique, et qui reste à l’extérieur. Partout, l’unité nationale est une priorité.

L’avenir a changé de sens, et le progrès est l’inverse de ce qu’une politique française entêtée, aveugle et autiste, fait subir aux Français. Partout, l’État Nation est la forme politique de la modernité, et partout, les États Nations cherchent à affirmer leur unité interne, pour mieux faire face aux défis extérieurs qui se multiplient. Partout, la frontière retrouve sa fonction vitale ; faire le tri entre ce qui vient de l’extérieur, qui est utile, choisi, et qui entre, et ce qui est dangereux, toxique, et qui reste à l’extérieur. Partout, l’unité nationale est une priorité. Voilà notre situation historique. Un nouvel obscurantisme nous rend prisonniers. Il s’appelle globalisme, multiculturalisme, individualisme. L’idéologie qu’il constitue est rétrograde, elle répète des refrains qui ont trente ans d’âge, et elle nous bouche l’avenir. Nous devons allumer d’autres Lumières pour faire reculer l’obscurité, et nous libérer des mensonges officiels comme des inquisiteurs qui appellent « fake news » ce qui révèle les mensonges de l’oligarchie au pouvoir. Nous devons suivre l’enseignement de Spinoza, de Kant, et nous libérer de la religion laïque de l’économie, qui a remplacé les religions divines sans rien tenir de leurs promesses ! L’avenir s’appelle Nation, s’appelle citoyen, s’appelle frontières. Le changement s’appelle sécurité, autorité, et stabilité. Et le progrès s’appelle demeurer Français, bien chez nous, bien sûr notre territoire, bien dans nos frontières, pour être à l’aise dans le monde.

Voilà notre situation historique. Un nouvel obscurantisme nous rend prisonniers. Il s’appelle globalisme, multiculturalisme, individualisme. L’idéologie qu’il constitue est rétrograde, elle répète des refrains qui ont trente ans d’âge, et elle nous bouche l’avenir. Nous devons allumer d’autres Lumières pour faire reculer l’obscurité, et nous libérer des mensonges officiels comme des inquisiteurs qui appellent « fake news » ce qui révèle les mensonges de l’oligarchie au pouvoir. Nous devons suivre l’enseignement de Spinoza, de Kant, et nous libérer de la religion laïque de l’économie, qui a remplacé les religions divines sans rien tenir de leurs promesses ! L’avenir s’appelle Nation, s’appelle citoyen, s’appelle frontières. Le changement s’appelle sécurité, autorité, et stabilité. Et le progrès s’appelle demeurer Français, bien chez nous, bien sûr notre territoire, bien dans nos frontières, pour être à l’aise dans le monde.

Les caractéristiques et le comportement des abeilles et d'autres insectes

Les caractéristiques et le comportement des abeilles et d'autres insectes

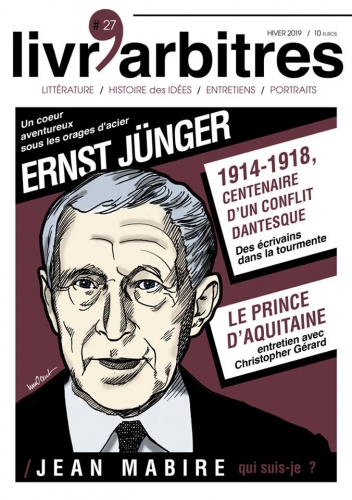

La phase du « Travailleur » a toutefois été très brève dans la longue vie de Jünger. Mais même après sa sortie sereine et graduelle hors de l’idéologie techniciste , Jünger refuse tout « escapisme romantique » : il rejette l’attitude de Cassandre et veut regarder les phénomènes en face, sereinement. Pour lui, il faut pousser le processus jusqu’au bout afin de provoquer, à terme, un véritablement renversement, sans s’encombrer de barrages ténus, érigés avec des matériaux surannés, faits de bric et de broc. Sa position ne relève aucunement du technicisme naïf et bourgeois de la fin du 19ème siècle : pour lui, l’Etat, la chose politique, le pouvoir sera déterminé par la technique, par la catégorie du « Travail ». Dans cette perspective, la technique n’est pas la source de petites commodités pour agrémenter la vie bourgeoise mais une force titanesque qui démultipliera démesurément le pouvoir politique. L’individu, cher au libéralisme de la Belle Epoque, fera place au « Type », qui renoncera aux limites désuètes de l’idéal bourgeois et se posera comme un simple rouage, sans affects et sans sentimentalités inutiles, de la machine étatique nouvelle, qu’il servira comme le soldat sert sa mitrailleuse, son char, son avion, son sous-marin. Le « Type » ne souffre pas sous la machine, comme l’idéologie anti-techniciste le voudrait, il s’est lié physiquement et psychiquement à son instrument d’acier comme le paysan éternel est lié charnellement et mentalement à sa glèbe. Jünger : « Celui qui vit la technique comme une agression contre sa substance, se place en dehors de la figure du Travailleur ». Parce que le Travailleur, le Type du Travailleur, s’est soumis volontairement à la Machine, il en deviendra le maître parce qu’il s’est plongé dans le flux qu’elle appelle par le fait même de sa présence, de sa puissance et de sa croissance. Le Type s’immerge dans le flux et refuse d’être barrage bloquant, figeant.

La phase du « Travailleur » a toutefois été très brève dans la longue vie de Jünger. Mais même après sa sortie sereine et graduelle hors de l’idéologie techniciste , Jünger refuse tout « escapisme romantique » : il rejette l’attitude de Cassandre et veut regarder les phénomènes en face, sereinement. Pour lui, il faut pousser le processus jusqu’au bout afin de provoquer, à terme, un véritablement renversement, sans s’encombrer de barrages ténus, érigés avec des matériaux surannés, faits de bric et de broc. Sa position ne relève aucunement du technicisme naïf et bourgeois de la fin du 19ème siècle : pour lui, l’Etat, la chose politique, le pouvoir sera déterminé par la technique, par la catégorie du « Travail ». Dans cette perspective, la technique n’est pas la source de petites commodités pour agrémenter la vie bourgeoise mais une force titanesque qui démultipliera démesurément le pouvoir politique. L’individu, cher au libéralisme de la Belle Epoque, fera place au « Type », qui renoncera aux limites désuètes de l’idéal bourgeois et se posera comme un simple rouage, sans affects et sans sentimentalités inutiles, de la machine étatique nouvelle, qu’il servira comme le soldat sert sa mitrailleuse, son char, son avion, son sous-marin. Le « Type » ne souffre pas sous la machine, comme l’idéologie anti-techniciste le voudrait, il s’est lié physiquement et psychiquement à son instrument d’acier comme le paysan éternel est lié charnellement et mentalement à sa glèbe. Jünger : « Celui qui vit la technique comme une agression contre sa substance, se place en dehors de la figure du Travailleur ». Parce que le Travailleur, le Type du Travailleur, s’est soumis volontairement à la Machine, il en deviendra le maître parce qu’il s’est plongé dans le flux qu’elle appelle par le fait même de sa présence, de sa puissance et de sa croissance. Le Type s’immerge dans le flux et refuse d’être barrage bloquant, figeant.

Cioran, like Nietzsche, writes with a kind of visceral identification with human history and the evolution of our consciousness as recorded in our literature and philosophy. For Cioran, how could one live without being part of a great nation? For him, a nation is a social, linguistic, and ethnic reality culminating in a shared psychic reality; a great nation is an agent influencing the course of human history, rather than a collection of individuals. A nation is a kind of conversation, a shared mind, extending across the centuries; at the same time, nations are equally mortal and artificial creations. Hence for Cioran, “France,” “Germany,” and “Romania” are entities which are at once conventional and whose potentialities and defects are intimately felt, about which the stakes could not be higher.

Cioran, like Nietzsche, writes with a kind of visceral identification with human history and the evolution of our consciousness as recorded in our literature and philosophy. For Cioran, how could one live without being part of a great nation? For him, a nation is a social, linguistic, and ethnic reality culminating in a shared psychic reality; a great nation is an agent influencing the course of human history, rather than a collection of individuals. A nation is a kind of conversation, a shared mind, extending across the centuries; at the same time, nations are equally mortal and artificial creations. Hence for Cioran, “France,” “Germany,” and “Romania” are entities which are at once conventional and whose potentialities and defects are intimately felt, about which the stakes could not be higher. Cioran, a voracious reader with a vast intellectual culture, is extremely critical of French thought and culture throughout history. Cioran foresees a great convergence: France’s bourgeois decadence indicates where all the other nations are heading, and by that decadence she will also really become a “normal” country, as afflicted by doubt and inferiority complexes as all the rest (45, 49). Cioran writes implausibly, “Her decline, obvious for almost a century, has not been opposed by any of her sons with a desperate protest” (63).

Cioran, a voracious reader with a vast intellectual culture, is extremely critical of French thought and culture throughout history. Cioran foresees a great convergence: France’s bourgeois decadence indicates where all the other nations are heading, and by that decadence she will also really become a “normal” country, as afflicted by doubt and inferiority complexes as all the rest (45, 49). Cioran writes implausibly, “Her decline, obvious for almost a century, has not been opposed by any of her sons with a desperate protest” (63). France is “a consoling space” for Cioran: “With what impatience I have awaited this outcome, so fertile for melancholic inspiration!” (70). The wandering and soon-to-be stateless Cioran wants to limit himself to a particular culture and place: “He who embraces too much falsifies the world, but in the first instance, himself . . . A great soul enclosed in the French forms, what a fecund type of humanity!” (87). France’s comfortable decadence will shield Cioran from his own excesses: “Let her measure cure us of pathetic and fatal wanderings” (32), “A country’s lack of life will protect us against the dangers of life” (88). Crepuscular France will finally give Cioran the opportunity to be in harmony with his time: “Alexandrianism is erudite debauchery as a system, theoretical breathing at the twilight, a moaning of concepts – and the only moment when the soul can harmonize its darkness with the objective unfolding of the culture” (70).

France is “a consoling space” for Cioran: “With what impatience I have awaited this outcome, so fertile for melancholic inspiration!” (70). The wandering and soon-to-be stateless Cioran wants to limit himself to a particular culture and place: “He who embraces too much falsifies the world, but in the first instance, himself . . . A great soul enclosed in the French forms, what a fecund type of humanity!” (87). France’s comfortable decadence will shield Cioran from his own excesses: “Let her measure cure us of pathetic and fatal wanderings” (32), “A country’s lack of life will protect us against the dangers of life” (88). Crepuscular France will finally give Cioran the opportunity to be in harmony with his time: “Alexandrianism is erudite debauchery as a system, theoretical breathing at the twilight, a moaning of concepts – and the only moment when the soul can harmonize its darkness with the objective unfolding of the culture” (70).

Le problème de l’Union européenne est l’inversion de l’idée selon laquelle l’union fait la force. Or je dirais, dans le cas précis : l’union fait la faiblesse. Et ce sur tous les plans.

Le problème de l’Union européenne est l’inversion de l’idée selon laquelle l’union fait la force. Or je dirais, dans le cas précis : l’union fait la faiblesse. Et ce sur tous les plans. Avec la guerre froide, cette pression s’est encore accentuée. Même en imaginant un retour sur le devant de la scène politique de bellicistes, qui n’étaient pas au rendez-vous, et pour cause, comment auraient-ils pu mener une guerre ? Le projet européen est d’abord bâti comme un moyen de résister à l’URSS en renforçant la cohésion de l’Ouest. Un des points trop souvent oubliés est le rôle majeur des États-Unis dans la construction européenne. Le plan Marshall n’était pas un geste philanthropique et désintéressé des Américains. Il avait une finalité très précise : renforcer l’Europe de l’Ouest à un moment où elle semblait menacée. La paix s’imposait donc aux Européens. Dans l’ensemble, ils étaient alignés sur les États-Unis, et il était parfaitement raisonnable de l’être. Il y avait une évidence stratégique du renforcement de l’Union à l’intérieur de l’OTAN.

Avec la guerre froide, cette pression s’est encore accentuée. Même en imaginant un retour sur le devant de la scène politique de bellicistes, qui n’étaient pas au rendez-vous, et pour cause, comment auraient-ils pu mener une guerre ? Le projet européen est d’abord bâti comme un moyen de résister à l’URSS en renforçant la cohésion de l’Ouest. Un des points trop souvent oubliés est le rôle majeur des États-Unis dans la construction européenne. Le plan Marshall n’était pas un geste philanthropique et désintéressé des Américains. Il avait une finalité très précise : renforcer l’Europe de l’Ouest à un moment où elle semblait menacée. La paix s’imposait donc aux Européens. Dans l’ensemble, ils étaient alignés sur les États-Unis, et il était parfaitement raisonnable de l’être. Il y avait une évidence stratégique du renforcement de l’Union à l’intérieur de l’OTAN. En revanche, quand Orban parle de la Hongrie chrétienne, son christianisme me semble beaucoup moins eschatologique qu’identitaire. La perspective qu’il mobilise, c’est la défense de la culture chrétienne contre la culture musulmane. Tous les électeurs comprennent que quand on parle de culture chrétienne, on parle d’une culture sans-les-musulmans ! Si vous parlez d’eschatologie aux électeurs de Salvini, je doute même qu’ils sachent de quoi il est question.

En revanche, quand Orban parle de la Hongrie chrétienne, son christianisme me semble beaucoup moins eschatologique qu’identitaire. La perspective qu’il mobilise, c’est la défense de la culture chrétienne contre la culture musulmane. Tous les électeurs comprennent que quand on parle de culture chrétienne, on parle d’une culture sans-les-musulmans ! Si vous parlez d’eschatologie aux électeurs de Salvini, je doute même qu’ils sachent de quoi il est question. De manière générale, oui. Pour ses peuples, l’Union se présente comme un ensemble qui n’a aucun contrôle direct de son environnement direct, au Sud. L’absence de maîtrise de cet environnement est mise en évidence par des flux migratoires incontrôlés.

De manière générale, oui. Pour ses peuples, l’Union se présente comme un ensemble qui n’a aucun contrôle direct de son environnement direct, au Sud. L’absence de maîtrise de cet environnement est mise en évidence par des flux migratoires incontrôlés. Je vous recommande le livre de Luuk Van Middelaar : Quand l’Europe improvise (3). C’est un livre passionnant mais accablant par rapport à cet autisme situation bureaucratique. Il le résume en disant en substance : « L’UE ne sait pratiquer qu’une politique de la règle, alors que ce qui lui est demandé est une politique de l’événement ». Ma différence avec lui, qui me rend plus pessimiste, serait que la politique de l’événement ne suffit pas. Elle se contente de faire face à des situations qui s’imposent, alors qu’une politique stratégique est celle qui permet d’anticiper ces événements et de parer à toute éventualité. A ce jour nous n’en avons aucune. Et je ne vois pas par quelles voies le Conseil des chefs d’État qui s’est imposé comme l’instance la moins inadéquate de riposte aux crises, Van Middelaar le montre bien, pourrait en élaborer une.

Je vous recommande le livre de Luuk Van Middelaar : Quand l’Europe improvise (3). C’est un livre passionnant mais accablant par rapport à cet autisme situation bureaucratique. Il le résume en disant en substance : « L’UE ne sait pratiquer qu’une politique de la règle, alors que ce qui lui est demandé est une politique de l’événement ». Ma différence avec lui, qui me rend plus pessimiste, serait que la politique de l’événement ne suffit pas. Elle se contente de faire face à des situations qui s’imposent, alors qu’une politique stratégique est celle qui permet d’anticiper ces événements et de parer à toute éventualité. A ce jour nous n’en avons aucune. Et je ne vois pas par quelles voies le Conseil des chefs d’État qui s’est imposé comme l’instance la moins inadéquate de riposte aux crises, Van Middelaar le montre bien, pourrait en élaborer une. Droits de l’homme et politique : toute la question est celle de l’alliance des deux termes et du passage de l’un à l’autre. Je ne suis pas critique à l’égard de l’idée des droits de l’homme en elle-même. La question porte sur les conditions de leur utilisation et de leur application : qu’en fait-on ? J’ai assez écrit sur lesdits droits de l’homme pour qu’on ne me suspecte pas de penser qu’il y a mieux à côté ! Qu’on les aime ou non, il faut faire avec. C’est le principe de légitimité inventé par la modernité et qui est en train de devenir planétaire. J’ai bien dit : en train.

Droits de l’homme et politique : toute la question est celle de l’alliance des deux termes et du passage de l’un à l’autre. Je ne suis pas critique à l’égard de l’idée des droits de l’homme en elle-même. La question porte sur les conditions de leur utilisation et de leur application : qu’en fait-on ? J’ai assez écrit sur lesdits droits de l’homme pour qu’on ne me suspecte pas de penser qu’il y a mieux à côté ! Qu’on les aime ou non, il faut faire avec. C’est le principe de légitimité inventé par la modernité et qui est en train de devenir planétaire. J’ai bien dit : en train.

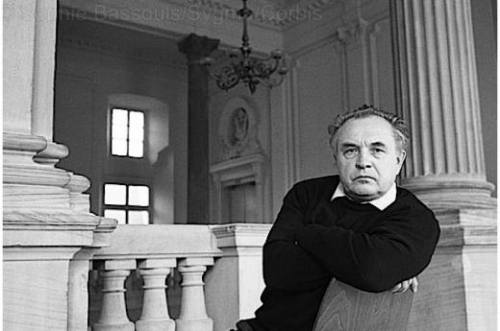

Les traces du totalitarisme

Les traces du totalitarisme

Car si l’on est dans une ère post-vérité, c’est donc qu’on est dans une ère post-langage. Certes, déjà les sophistes usaient du langage comme d’un simple outil de pouvoir, au demeurant fort rémunérateur (cf. Les Zemmour qui en font profession et gagnent très bien leur vie, à proportion de leurs outrances – l’outrance est aujourd’hui économiquement rentable) – ce qui tendrait à relativiser le préfixe de « post ».

Car si l’on est dans une ère post-vérité, c’est donc qu’on est dans une ère post-langage. Certes, déjà les sophistes usaient du langage comme d’un simple outil de pouvoir, au demeurant fort rémunérateur (cf. Les Zemmour qui en font profession et gagnent très bien leur vie, à proportion de leurs outrances – l’outrance est aujourd’hui économiquement rentable) – ce qui tendrait à relativiser le préfixe de « post ».