La métaphysique de la tripartition indo-européenne, Partie 1

Collin Cleary

Note de l’auteur :

Cet essai fut originellement écrit il y a presque exactement treize ans. Je m’étais abstenu de le publier pendant toutes ces années, parce que je considérais que les idées qu’il contenait étaient un peu trop spéculatives et audacieuses. Je crois cependant que ces idées sont trop intéressantes pour être gardées indéfiniment non-publiées. Dans l’espoir que d’autres puissent en profiter, j’ai décidé que le temps était venu de publier cet essai. Je dois cependant souligner que ces idées sont en effet hautement spéculatives, et la théorie exposée ici demeure un travail en progrès.

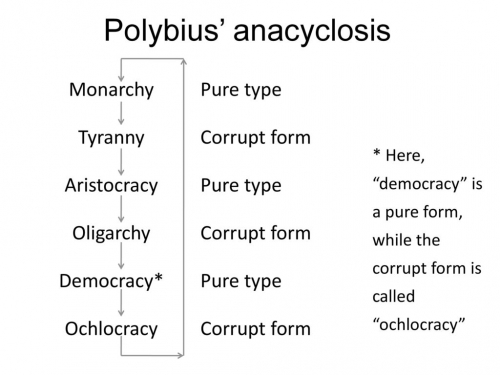

- Introduction : le schéma tripartite de Dumézil

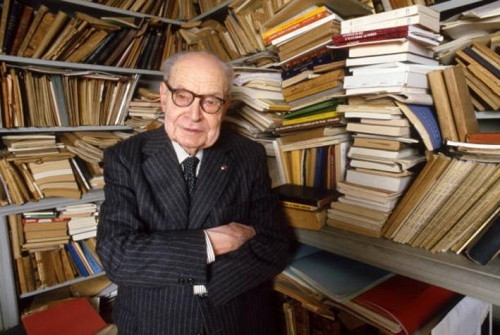

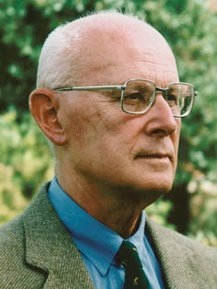

Le plus éminent savant dans le domaine des études indo-européennes est le regretté Georges Dumézil du Collège de France. La contribution de Dumézil à ce domaine plutôt restreint peut être résumée à deux choses : (a) il remarqua que toutes les cultures indo-européennes exhibaient une structure tripartite fondamentale ; et (b) il découvrit que cette structure était codifiée dans la mythologie de chaque peuple indo-européen. Je décrirai d’abord simplement cette tripartition et ensuite j’en proposerai quelques exemples. Ce sujet est déjà familier pour beaucoup de mes lecteurs.

Au sommet de la société indo-européenne se trouve ce que Dumézil appelle la première fonction. Celle-ci incarne des aspects jumeaux : un aspect juridique et un aspect sacerdotal. Elle concerne l’administration de la justice, et la religion. Elle est donc parfois appelée la fonction « sacerdotale-royale » ou « sacerdotale-juridique ». La deuxième fonction est assumée par la classe guerrière ou militaire, qui sert à protéger la société dans son ensemble et à faire la guerre à ses ennemis. La troisième fonction incorpore tous ceux qui s’occupent de la production ou de la fourniture de biens, de services, et de nourriture. Ainsi, cette classe incorpore tous les marchands, fermiers, commerçants, artisans, etc.

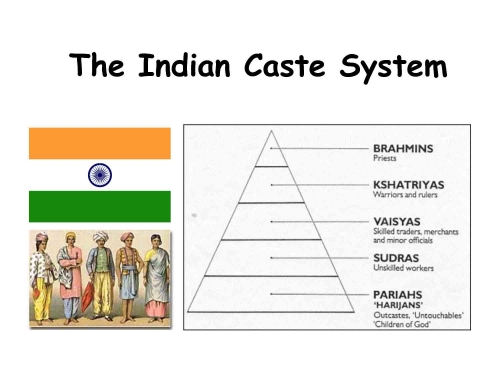

Quant à savoir quelle est la fonction qui règne vraiment dans la société indo-européenne, c’est une question complexe. D’une certaine manière, il semble évident que la première fonction règne. Elle joue un rôle organisateur et structurant dans la société. Parce qu’elle inclut un aspect juridique, elle est impliquée dans la compréhension et l’application de lois abstraites. De plus, puisqu’elle implique aussi un aspect religieux, c’est la première fonction qui fournit à la société l’accès au divin, la plus haute autorité de toutes. Cependant, dans la plupart des sociétés indo-européennes, c’est de la classe guerrière, ou classe de la deuxième fonction, que les souverains provenaient. C’est le cas pour la caste indienne des Kshatriyas, par exemple.

Donc qui règne, la première ou la deuxième fonction ? Le problème est facilement résolu en regardant la description de la société timarchique traditionnelle dans la République de Platon. La timarchie est une société gouvernée par des membres de la classe guerrière, qui sont éduqués et conseillées par des membres de la première fonction, ou classe sacerdotale. Cela fait des guerriers des souverains de facto, mais puisque les prêtres font les lois, et servent d’autorité finale, on pourrait aussi soutenir qu’au sens réel c’est la première fonction qui règne. La timarchie est en fait la forme prise par la plupart des sociétés indo-européennes traditionnelles.

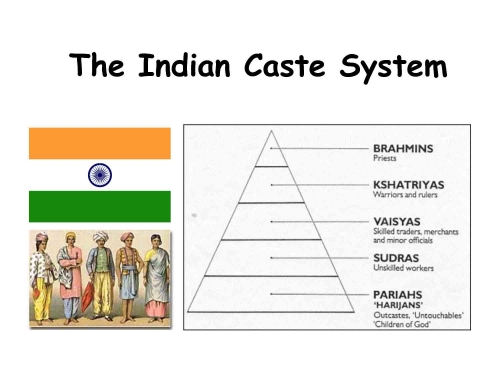

A présent, permettez-moi de donner quelques exemples spécifiques de tripartition dans les cultures indo-européennes, et dans le mythe indo-européen. En Inde nous trouvons trois castes principales : brahmanes (prêtres), kshatriyas (guerriers), et vaishyas (producteurs). Une quatrième caste, les shudras, est simplement celle des serviteurs des autres. Les aspects jumeaux de la première fonction sont représentés par les dieux Varuna et Mitra. La deuxième fonction est représentée par le dieu puissant et belliqueux Indra. La troisième fonction est représentée par les jumeaux Ashvins.

En allant très loin en fait, parmi les Celtes nous trouvons les druides (qui étaient prêtres et juristes), les flaith (qui étaient une aristocratie militaire), et les bo airig, qui signifie littéralement « hommes libres possédant du bétail ». Parmi les tribus germaniques nous trouvons une tripartition sociale similaire, et des dieux similaires. Odin et Tyr représentent, respectivement, l’aspect religieux et l’aspect juridique de la souveraineté. Comme Varuna, Odin est représenté comme un habile magicien. Comme Mitra, Tyr est le contrat personnifié. Thor, qui correspond très clairement à Indra, est le dieu des guerriers. Freyr et Freya représentent la troisième fonction. Il faut noter, à cet égard, que tout ce qui a un rapport avec la production ou la fécondité est associé à la troisième fonction. C’est pourquoi Freyr et Freya, des dieux de la sensualité, sont des dieux de la troisième fonction. Dans le panthéon romain, nous avons Jupiter (première fonction), Mars (deuxième fonction), et Quirinus (troisième fonction). En Iran nous trouvons les Amesa-Spentas, aspects du Seigneur Sage, Ahura Mazda. Ceux-ci incluent Asa et Vohu Manah, qui représentent l’ordre cosmique et la moralité et qui sont donc des déités de la première fonction. Xsathra est puissance ou pouvoir, et est donc associé à la deuxième fonction. Armaiti, Haurvatat, et Amerutat sont les patrons, respectivement, de la terre, de la santé, et de l’immortalité, et semblent donc représenter des caractéristiques de la troisième fonction.

La tripartition est encodée dans le mythe indo-européen par d’autres manières encore. Dans un mythe scythe, par exemple, les dieux envoient à l’humanité quatre objets : un calice, une épée, un joug, et une charrue. Le calice est clairement un objet rituel, représentant la première fonction sacerdotale. L’épée est évidemment un objet de guerre et est donc associée à la deuxième fonction. Le joug et la charrue servent à cultiver le sol, et sont donc des objets de troisième fonction. Dans la légende irlandaise, les Tuatha de Danaan étaient supposés avoir quatre grands trésors. Le premier était la Pierre du Destin, qui servait pour les couronnements. Le deuxième et le troisième étaient l’épée invincible de Lug au Long Bras, et une lance magique (les deux ensemble représentent la deuxième fonction). Le quatrième était le Chaudron du Dagda, qui était une sorte de corne d’abondance.

La tripartition est au cœur de l’Iliade. Ce qui cause la Guerre de Troie est la rivalité entre les déesses Héra, Athéna et Aphrodite, parmi lesquelles un certain Pâris doit choisir la plus belle. Pour le séduire, Héra lui offre la souveraineté (première fonction) ; Athéna lui offre la prouesse militaire (deuxième fonction) ; et Aphrodite lui offre l’amour de la plus belle femme dans le monde (troisième fonction). En choisissant Aphrodite, et Hélène, Pâris voue sa nation à la perte en sortant de l’ordre naturel des choses : pour les Indo-Européens, la souveraineté et la chevalerie doivent toujours passer avant la sensualité.

Ayant fait un bref exposé de la tripartition indo-européenne, je vais maintenant arguer que nos ancêtres avaient raison de penser que la tripartition est plus qu’une simple structure sociale. Les trois fonctions sont en réalité les reflets d’une métaphysique tripartite plus profonde, et chaque niveau de réalité exhibe cette structure. Avant de commencer à défendre cette idée, je veux très brièvement faire trois remarques. Avant tout, je ne dis pas que « toutes les choses vont par trois ». Ce dont je parle ici est une forme particulière de structure triple, et non la triplicité en tant que telle. Ma procédure sera inductive. Je présenterai de nombreux exemples d’aspects de la réalité structurés d’une manière analogue au système social indo-européen. Dans les sections 7 et 8 je proposerai des exposés purement abstraits de la nature de ces principes, m’abstenant de toute application spécifique de ceux-ci.

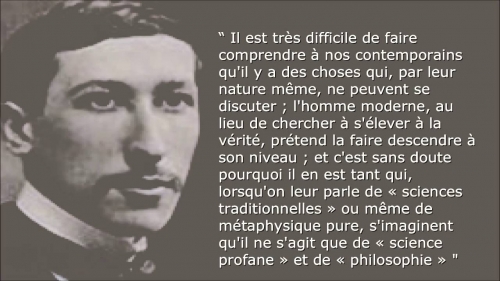

Ensuite, je ne traiterai pas de la question de la manière dont les anciens Indo-Européens auraient pu posséder cette connaissance avancée. Je supposerai que je n’ai pas besoin de convaincre mes lecteurs qu’il est possible que nos lointains ancêtres connaissaient plus de choses que nous, et non pas moins.

Enfin, il est inévitable que certains objecteront à ma procédure ici en disant que les Indo-Européens tentaient simplement de justifier leur structure sociale en la « lisant » dans la structure même du cosmos. Cette objection sera émise spécialement par ceux qui objectent aux traits de l’« idéologie » indo-européenne qui sont « politiquement incorrects », par exemple le patriarcat, l’aristocratie, le militarisme, et, mon « isme » préféré, ce que Jacques Derrida appelait le « phallo-logocentrisme ». Il est bien sûr possible que les Indo-Européens aient simplement pu lire leur structure sociale dans les cieux, mais nous devons au moins envisager que cela a pu être l’inverse – qu’ils ont pu lire cette structure dans les cieux, et ensuite bâtir leur société autour d’elle. Mais cette objection est vraiment à coté de la question, car les exemples de tripartition que je présenterai ici sont principalement mes propres observations, ma propre application des catégories indo-européennes à d’autres régions du réel.

La Métaphysique de la Tripartition indo-européenne, Partie 2

La tripartition dans la Société Humaine Société, Psychologie, et Physiologie

Collin Cleary

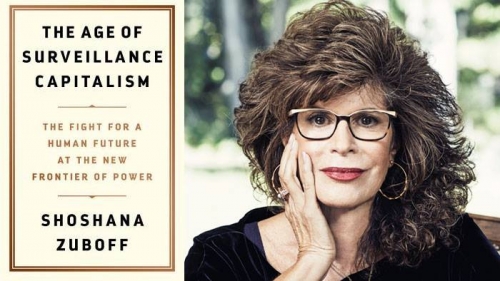

Le Jugement de Pâris par Rubens

- L’Ame Humaine Tripartite

Pour commencer, les Indo-Européens pensaient traditionnellement que la société doit être structurée en trois parties ou « fonctions », parce que les gens eux-mêmes exhibent trois types d’âmes basiques.

Les étudiants de la philosophie grecque réaliseront que c’est exactement la vision de Platon. Dans la République, Platon divise sa cité idéale en trois classes : les philosophes, les gardiens ou guerriers, et les producteurs. Cela correspond précisément à la tripartition indo-européenne, les philosophes-rois prenant la place des prêtres-juristes. Mais dans la République, Platon ne fait cette remarque politique que pour faire une remarque psychologique. Il dit que chaque être humain exhibe cette structure tripartite.

Dans nos âmes il y a un élément-guide – un élément qui contrôle, qui dit oui ou non, qui parle « sens » en nous quand les émotions s’égarent. Cet élément se préoccupe à la fois des règles, de l’ordre, de la logique, et de ce que nous appelons la spiritualité. Il correspond donc à la fonction juridique-sacerdotale de la société indo-européenne. Nous avons aussi ce que Platon appelle un élément « passionné » [spirited] (à ne pas confondre avec « spirituel ») qui bat sauvagement dans la poitrine dès que le corps ou l’honneur de quelqu’un est menacé. Il nous pousse à combattre, parfois stupidement. Cela correspond évidemment à l’élément gardien ou guerrier (deuxième fonction). Enfin, nous avons ce que Platon appelle la partie « appétitive » ou « désirante » de l’âme. C’est la partie de nous qui est avide de biens physiques : nourriture, sexe, plaisirs sensuels de toutes sortes, argent, trésors, biens immobiliers, etc. La vertu, pour Platon, est présente dans une âme quand ces trois éléments coexistent harmonieusement, l’harmonie étant largement imposée par le contrôle de la première fonction, ou fonction rationnelle.

- Les trois types humains

L’autre remarque psychologique de Platon est que les gens diffèrent selon la proportion de ces éléments dans leur âme individuelle. Pour le dire simplement, certains humains tendent naturellement à être intellectuels ou spirituels. D’autres sont principalement passionnés, agressifs, préoccupés par les choses comme la compétition, l’honneur, et la gloire. D’autres encore sont principalement appétitifs, avec des préoccupations qui ne s’élèvent jamais au-dessus du niveau de la satisfaction physique et sensuelle, ou du gain matériel.

Bref, pour Platon et pour les Indo-Européens, il existe des souverains et des prêtres naturels, des guerriers naturels, et des producteurs et des commerçants naturels. Pour les Indo-Européens, la société doit exhiber une structure tripartite parce que les humains eux-mêmes se répartissent dans un tel groupement. Soit dit au passage, Platon pensait que la plus grande partie de l’humanité tombait dans la troisième classe appétitive, et c’est pourquoi il s’opposait à la démocratie. Le règne de « la majorité » signifie inévitablement le règne de ceux qui ne sont pas principalement raisonnables, spirituels, ou honorables, mais plutôt de ceux qui sont principalement préoccupés par le gain personnel, et par l’instant.

- Les types somatiques et tempéramentaux

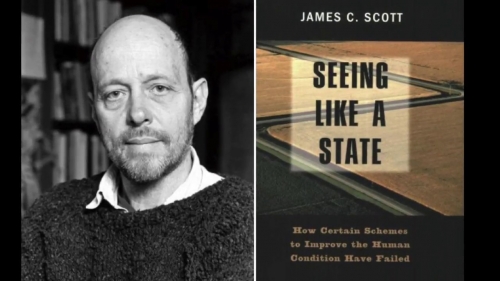

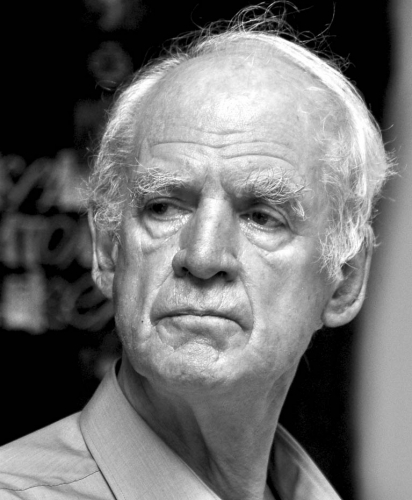

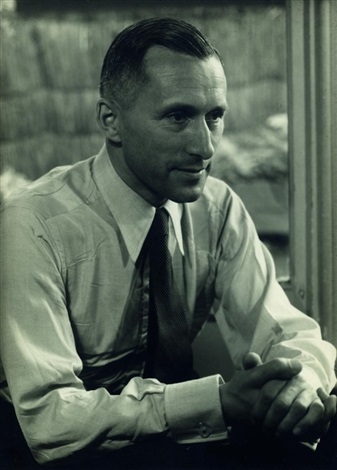

William Herbert Sheldon

William Herbert Sheldon

Ainsi, ce que nous avons vu jusqu’ici est que la tripartition indo-européenne nous fournit une psychologie selon laquelle nous pouvons comprendre la dynamique de notre âme individuelle, et selon laquelle nous pouvons nous catégoriser et nous comprendre, nous-mêmes et les autres. Cependant, la tripartition n’est pas seulement présente dans l’âme mais aussi dans le corps. Dans ce qui suit je m’inspirerai des travaux du psychologue W. H. Sheldon, dont le travail a été déclaré « discrédité » aujourd’hui (tous ses livres sont épuisés), parce qu’il a commis le péché impardonnable de suggérer que la biologie forme notre destin [1].

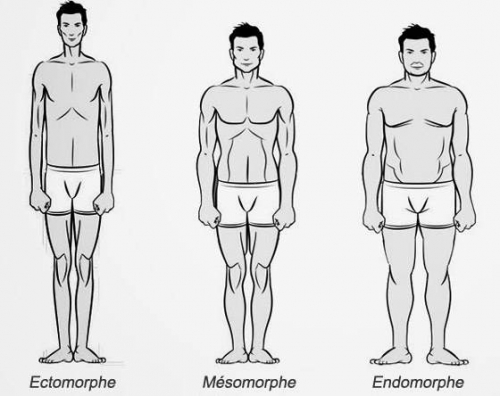

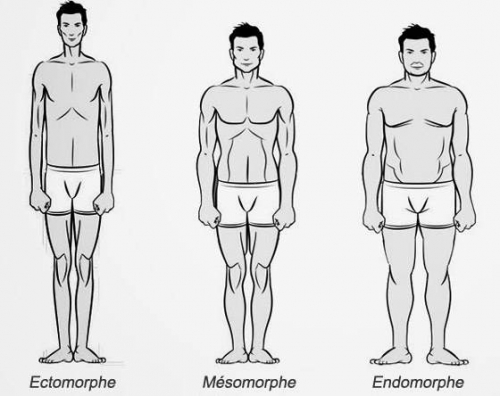

Sheldon distingue trois types physiques ou « morphes », et trois types de tempérament, ou « tonies ». Les morphes seront familiers à beaucoup d’entre vous : ce sont l’ectomorphe, le mésomorphe, et l’endomorphe [2] (la signification littérale de ces noms sera discutée dans la section 4, plus loin).

L’ectomorphe est typiquement mince, peut-être quelque peu fragile et délicat. La linéarité prédomine. Il y a peu de graisse et peu de masse musculaire. Le tempérament typiquement exhibé par l’ectomorphe est cérébrotonique. Il est souvent introverti, souvent complètement absorbé dans ses propres processus de pensée. La plupart des schizophrènes exhibent un type ectomorphique. Le cérébrotonique tend à un comportement nerveux, obsessif, et est souvent hautement doué pour les recherches théoriques. Je n’ai pas besoin de souligner ce que nous avons tous observé dans nos vies : que les « cérébraux » et les « dingues de science » tendent à être minces, dégingandés, et nerveux. Mais ce type, qui est attiré par l’abstrait et le rationnel, peut aussi être attiré par le spirituel et le mystique.

Le mésomorphe a typiquement des épaules larges, avec une taille étroite, lui donnant une apparence triangulaire. Il est naturellement bien-proportionné. Comme l’ectomorphe, il tend à avoir peu de graisse, mais à la différence de l’ectomorphe sa musculature est prononcée. C’est un athlète naturel, avec un corps construit pour le conflit et la compétition. Concernant son tempérament, Sheldon l’appelle somatotonique. C’est un tempérament orienté vers l’action. Le somatotonique est un guerrier, recherchant la compétition, l’effort, la victoire, et la gloire de toutes sortes. De tels individus tendent vers l’extraversion. Ils veulent faire des choses, plutôt que s’asseoir et y réfléchir. Ils tendent à l’insensibilité, et même parfois à la brutalité. Ils veulent diriger, mais ils peuvent aussi être des partisans fanatiques s’ils rencontrent quelqu’un qu’ils estiment plus hautement qu’eux-mêmes.

L’endomorphe est de forme ovale, tendant souvent à l’obésité. Il est l’opposé diamétral de l’ectomorphe. En termes géométriques, il est rond plutôt que droit. La musculature qu’il peut avoir est très souvent cachée sous la graisse. L’endomorphe est viscérotonique ou « dominé par les boyaux ». Un représentant des théories de Sheldon remarque que pour les viscérotoniques « l’amour du confort physique, de la nourriture, des cérémonies polies, de la compagnie, et du sommeil sont des caractéristiques dominantes ». Il est caractérisé par « la douceur du corps et de l’esprit » [3]. Cette « douceur de l’esprit » se manifeste par une tendance à la passivité, à la complaisance, à l’amabilité indiscriminée, à la jovialité, et à une absence de volonté ou une incapacité à faire des jugements fermes ou tracer des distinctions fermes.

Il devrait être évident que ces trois types corporels et tempéramentaux correspondent aux trois fonctions indo-européennes. L’ectomorphe et cérébrotonique est l’intellectuel, le raisonneur abstrait, le juge, ainsi que le mystique. Le mésomorphe et somatotonique est le guerrier naturel. L’endomorphe et viscérotonique est naturellement incliné vers la production, la consommation, et la satisfaction sensuelle. La description par Sheldon des trois tempéraments peut être considérée comme un supplément à la discussion par Platon des types rationnel, passionné, et appétitif. Dans la distinction des trois « morphes » associés à ces types nous trouvons une expression physique de la tripartition, ce qui est particulièrement remarquable.

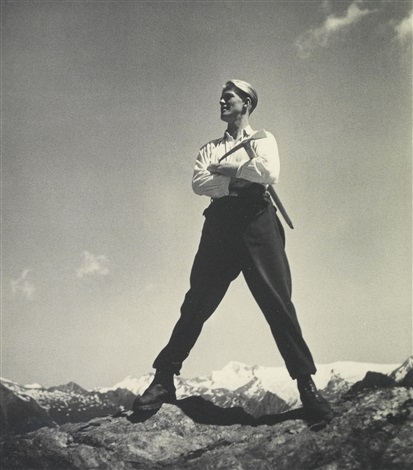

- La signification du mésomorphe

Ce qui est particulièrement intéressant ici est la « position médiane », au niveau physique aussi bien qu’au niveau spirituel, occupée par les mésomorphes-somatotoniques. Comme l’ectomorphe, il est maigre. Comme l’endomorphe, il est épais. Mais sa maigreur épaisse est musculaire. Il manque de la graisse de l’endomorphe, mais à la différence de l’ectomorphe sa musculature tend à être visible.

Dans l’enseignement ésotérique de Platon – rapporté sous forme fragmentaire par Aristote et d’autres – le grand philosophe distingue deux principes ultimes et métaphysiques qu’il appelle l’Un et la Dyade Indéfinie. L’Un est conçu comme mesure, ordre, proportion. La Dyade est conçue comme les principes jumeaux du Grand et du Petit. On peut facilement surimposer les trois morphes à ces catégories, le mésomorphe représentant un milieu entre des extrêmes. C’est le type parfaitement mesuré, ordonné, proportionnel. C’est dans l’espoir d’approcher de sa forme que des millions de dollars sont dépensés chaque année pour adhérer à des sociétés de gymnastique. L’endomorphe et l’ectomorphe sont, respectivement, le Grand et le Petit. C’est comme si l’endomorphe avait trop de quelque chose et l’ectomorphe trop peu.

Il y a une autre manière plus importante par laquelle le mésomorphe-somatotonique est un « milieu » entre les deux autres. L’ectomorphe tend vers l’abstrait, le cérébral, et l’intellectuel. L’endomorphe-viscérotonique est à l’opposé : inclinant vers la sensualité, la physicalité, et l’oubli insouciant. En termes platoniciens-aristotéliens, l’un est plus proche du domaine du Formel et de l’Idéal, l’autre du matériel. Il est probable que les deux mènent des existences problématiques. Le mésomorphe, d’autre part, est un heureux milieu entre les deux. Il est incontestablement physique, et se réjouit de sa physicalité. Mais à la différence de l’endomorphe, sa physicalité n’est pas celle de l’autosatisfaction et de la sensualité. Le mésomorphe utilise sa physicalité pour poursuivre des idéaux. Ceux-ci vont de buts triviaux, comme gagner une partie, ou marquer un point, à des questions plus sérieuses, comme défendre l’honneur, vaincre une menace contre soi-même ou son peuple, ou défendre les sans-défense.

Le mésomorphe-somatotonique possède ainsi l’idéalisme de l’ectomorphe, mais sans sa tendance aux choses détachées-du-monde et à l’obsession de soi. Il possède la physicalité de l’endomorphe, mais sans sa tendance à la recherche du plaisir et à la passivité. C’est essentiellement pour cette raison que les anciens peuples, en particulier les Indo-Européens, regardaient ce type comme le type humain idéal. Ils lui érigeaient des statues, écrivaient des poèmes épiques et des sagas sur lui, et en général lui rendaient un culte comme étant l’être humain qui pouvait le plus approcher du divin (je reviendrai sur ce point quand je discuterai de la tripartition dans le tantrisme).

Le buste triangulaire du mésomorphe (souvent appelé la « forme en V ») est également intéressant. N’est-il pas fascinant que ce type, qui est une sorte d’équilibre entre les deux autres, approche d’une forme « triangulaire », et que cette forme soit trouvée si attirante ?

- Les organes corporels

Si nous regardons l’arrangement du corps humain, nous trouvons quatre systèmes principaux alignés autour de son axe central, l’épine dorsale. Ce sont le cerveau, le cœur, les boyaux, et les organes génitaux. Dans la pensée traditionnelle, ils sont l’expression physique des trois fonctions : le cerveau représentant, bien sûr, la première fonction. La passion de la deuxième fonction a depuis longtemps été associée à la région du cœur. Le terme de Platon qui est traduit par « passion » est thumos, qui était conçu comme une partie physique du corps, situé dans la région du cœur. Les boyaux et les organes génitaux représentent clairement la troisième fonction. Il est également intéressant de remarquer que le cœur occupe à peu près une position médiane entre le cerveau et les organes génitaux, de même que le mésomorphe-somatotonique est le milieu entre les deux autres types.

Une « qualité yang » dure caractérise les organes associés à la première et à la deuxième fonctions. Une « qualité yin » douce est typique des organes associés à la troisième fonction. Spécifiquement, les organes de la cavité abdominale sont non seulement mous, mais ils sont aussi les moins protégés par les os. Tout durcissement de ces organes signifie une maladie. La tête, par contre, une région associée à la première fonction, est l’une des parties les plus dures du corps. On peut aussi trouver des structures dures et cristallines dans le cerveau lui-même, dans la glande pinéale [4]. A la deuxième fonction sont associées les muscles les plus importants et les plus visiblement apparents du corps, dont la « dureté » est un signe de puissance. Nous utilisons le terme « durcir » pour décrire le processus de perfectionnement de ces muscles, qui sont si nécessaires pour l’attaque et la défense. Bien que les organes sexuels soient associés à la troisième fonction, chez le mâle ils ont, du moins une partie du temps, la qualité yang dure. C’est grâce à l’interaction de l’anatomie sexuelle mâle avec le système circulatoire, qui est un système de deuxième fonction, comme je le discuterai brièvement.

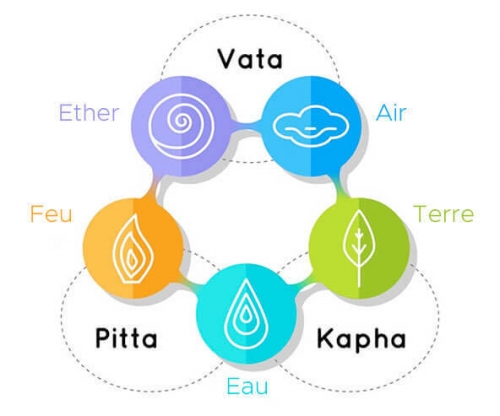

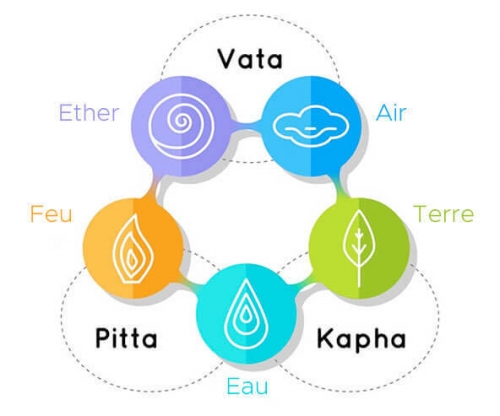

- Les Doshas ayurvédiques et les types sexuels

La typologie physique et tempéramentale précédente fut considérablement développée par les anciens peuples indo-européens, en utilisant un vocabulaire très différent, bien sûr. Le meilleur exemple de cela peut être trouvé dans l’ancien système indien de la médecine ayurvédique. Ce matériel a été popularisé dans les années récentes dans un certain nombre de best-sellers, en particulier ceux de Deepak Chopra (envers qui nous devrions à part cela adopter un sain scepticisme). Le système dépend d’une division des êtres humains en trois types, appelés doshas : Vata, Pitta, et Kapha. Ceux-ci sont conçus comme des forces opérant dans le corps.

Tout comme dans l’image platonicienne de l’âme, nous avons trois types en nous, mais chez la plupart des gens un dosha prédomine. Un type Vata est mince et dégingandé, avec une tendance à la crainte et à l’obsession de soi. Il est aussi imaginatif, introspectif, et souvent intellectuel. En d’autres mots, ectomorphique-cérébrotonique. Ce qui est particulièrement fascinant ici, c’est que l’Ayurveda conçoit le dosha Vata comme « dirigeant » les autres doshas. Deepak Chopra parle en fait du Vata comme du « roi » des doshas [5]. Le type Pitta est musculaire et bien-proportionné, agressif, impérieux, et déterminé. En d’autres mots, le type « guerrier » ; le mésomorphe-somatotonique. Le type Kapha a une tendance à l’obésité, à la bonne humeur, à l’autosatisfaction, et à la paresse mentale. Evidemment, l’endomorphe-viscérotonique.

Cette tripartition fut remarquée par les Indiens même dans le domaine du sexe. L’Ananga Ranga, un manuel sexuel indien de date incertaine (bien que clairement rédigé durant le dernier millénaire) divise les hommes en trois types sexuels : le Shasha ou homme-lièvre, le Vrishabha ou homme-taureau, et l’Ashwa ou homme-étalon. Je commencerai par l’homme-taureau. On le reconnaît, affirme l’Ananga Ranga, à son phallus ou lingam d’une longueur correspondant à la largeur de neuf doigts. Autant que je puisse me l’imaginer, cela correspond approximativement à la moyenne de Kinsey. D’après le texte, le corps de cet homme est « solide, comme celui d’une tortue ; sa poitrine est charnue, son ventre dur, et les grenouilles [= les triceps] de ses bras sont tournées de manière à être mises de face ». Bref, c’est un mésomorphe classique. Le texte nous informe que sa disposition est « cruelle et violente, agitée et irascible, et son Kama-salila [= semence] est toujours prêt » [6]. L’homme-étalon a un lingam d’une longueur correspondant à peu près à la largeur de douze doigts. Il est de forme épaisse. Le texte nous dit qu’il est « d’esprit insouciant, passionné et avide, glouton, changeant, paresseux, et rempli de sommeil » [7]. Il s’agit clairement du type endomorphe-viscérotonique, correspondant à la troisième fonction indo-européenne.

J’ai gardé l’homme-lièvre pour la fin, parce qu’ici la correspondance n’est pas aussi précise. Le texte nous dit que son lingam est d’une longueur correspondant à peu près à la largeur de six doigts. « Sa figure est courte et maigre, mais bien proportionnée en forme et en fabrication … son visage est rond … Il est d’une disposition tranquille ; il fait le bien pour l’amour de la vertu ; il est impatient de se faire un nom ; il est humble dans son comportement… » [8]. Rien ici sur l’aspect mince, dégingandé et introspectif. Mais l’adjectif « maigre » suggère la minceur. Le fait qu’il fasse le bien « pour l’amour de la vertu » suggère le goût des principes du cérébrotonique classique. Notez, à ce propos, que l’homme-taureau ou mésomorphe est le milieu mathématique précis entre l’homme-lièvre et l’homme-étalon. L’homme-lièvre a une taille de six doigts, l’homme-taureau de neuf, et l’homme-étalon de douze. Neuf est un nombre très important dans les traditions indo-européennes, particulièrement dans la tradition germanique.

- Paracelse

Paracelse

Paracelse

Nous trouvons quelque chose de remarquablement similaire à ces distinctions physiologiques indiennes tripartites dans les ouvrages du médecin et alchimiste allemand du XVIe siècle, Theophrastus Bombastus von Hohenheim, appelé Paracelse. Il y a une sorte d’esprit indo-européen à l’œuvre chez ce penseur, car il insiste pour passer du système quadripartite des éléments (Terre, Air, Feu, et Eau – qui est peut-être bien une conception d’origine proche-orientale et non indo-européenne) au système tripartite du Soufre, du Mercure et du Sel. Mais ce n’est pas la pure triplicité de ce système qui est curieuse, mais plutôt sa correspondance exacte avec les trois fonctions indo-européennes.

Dans son Opus Paramirum (1530-1), Paracelse écrit, « La première chose que le médecin devrait savoir est que l’homme est composé de trois substances » [9]. Ce sont le Mercure, le Soufre et le Sel, dit-il, qui se combinent pour faire un corps. « Pour rendre les choses visibles, la Nature doit être obligée de se montrer … Prenez un morceau de bois. C’est le corps. Maintenant brûlez-le. La partie inflammable est le Soufre, la fumée est le Mercure, et la cendre est le Sel » [10]. Comme le note un commentateur, « Il utilisait ces termes pour décrire des principes de constitution, représentant l’organisation (Soufre), la masse (Sel), et l’activité (Mercure), toutes des variétés des formes spécifiques accomplies par les intelligences et semences immanentes de la matière » [11]. La correspondance avec le système indo-européen est donc comme suit : le Soufre, le principe organisateur = Première Fonction ; le Mercure, le principe actif et volatile = Deuxième fonction ; et le Sel, le principe de la pure masse ou matière = Troisième Fonction.

Notes

[1] Mêmes les bibliothèques se débarrassent des livres de Sheldon. Des exemplaires sont encore en circulation, mais souvent pour un prix élevé. Voir en particulier les ouvrages suivants : The Varieties of Human Physique (New York: Harper, 1940); The Varieties of Temperament (New York: Harper, 1942); Atlas of Men: Guide for Somatotyping the Adult Male at All Ages (New York: Gramercy Publishing, 1954).

[2] La terminologie de Sheldon continue à vivre dans les milieux de la santé et du fitness – particulièrement dans le bodybuilding.

[3] Robert S. De Ropp, The Master Game (New York: Delacorte Press, 1968), 116.

[4] Ces remarques peuvent être trouvées dans Wolfang Schad, Man and Mammals: Toward a Biology of Form, trans. Carroll Scherer (Garden City, New York: Waldorf Press, 1977), 17.

[5] Deepak Chopra, Perfect Health (New York: Harmony Books, 1991), 36.

[6] Kalayana Malla, Ananga Ranga, trans. F.F. Arbuthnot and Richard F. Burton (New York: Medical Press, 1964), 16

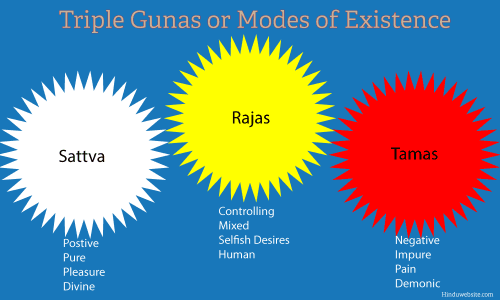

[7] Ibid., 16. Il est intéressant de noter que Shiva, l’incarnation de la troisième fonction, le principe du Tamas dans la théorie indienne des gunas, est appelé « seigneur du sommeil ». Plus de détails là-dessus plus tard.

[8] Ibid, 15.

[9] Paracelse, Essential Readings, ed. Nicholas Goodrick-Clarke (Berkeley, California: North Atlantic Books), 76.

[10] Ibid., 78.

[11] Ibid., 28.

La métaphysique de la tripartition indo-européenne, Partie 3

La tripartition chez les animaux et dans la nature en général

La tripartition chez les animaux

- Les trois systèmes de Schad

Jusqu’ici j’ai appliqué la tripartition indo-européenne au domaine humain, à l’ordre politique et sociétal, à la psychologie individuelle et de groupe, à la physionomie, à l’anatomie, et à la sexualité. Je vais maintenant passer à un niveau d’abstraction plus élevé, à la nature de l’organisme des mammifères en général. Dans les remarques qui suivent, je m’inspirerai principalement de l’œuvre des scientifiques Wolfgang Schad et Henri Bortoft, adeptes de l’anthroposophie.

Schad identifie trois processus fonctionnels fondamentaux dans l’organisme des mammifères : le système nerveux-sensoriel, le système respiratoire-circulatoire, et le système métabolique-membres. En termes de tripartition indo-européenne, les correspondances sont assez évidentes. Le système nerveux-sensoriel fonctionne pour guider le corps. Il correspond donc à la première fonction (souvenez-vous que l’ectomorphe, que j’ai identifié à la première fonction, a été décrit en termes de tempérament comme un cérébrotonique, où le système nerveux domine). Le système respiratoire-circulatoire correspond à la deuxième fonction. Une coïncidence heureuse fait que dans les traductions [anglaises] de Platon, nous utilisons le terme « spirited » pour décrire les gardiens ou guerriers, qui sont censés posséder l’« esprit ». Les anciens Indo-Européens pensaient que leurs guerriers étaient littéralement inspirés. Les types guerriers sont aussi connus pour leur manière de respirer et de gonfler la poitrine, une forme de parade destinée à intimider les autres mâles. Ainsi, il y a une association naturelle entre la deuxième fonction, le guerrier, et le système respiratoire-circulatoire. Mais beaucoup plus important est le fait que c’est dans le système circulatoire que nous trouvons les principaux gardiens du corps : les globules blancs qui servent à attaquer les envahisseurs.

Il nous reste à examiner le système métabolique-membres. Il y a là aussi une association entre le métabolisme et la troisième fonction indo-européenne. Dans la société indo-européenne, la troisième fonction est la fonction nourricière ; elle inclut tout ce qui est concerné par la fabrication ou l’apport de nourriture. Les deux organes du corps qui représentent le plus les différents aspects de la troisième fonction (qui sont complexes) sont l’estomac et les organes génitaux (souvenez-vous que l’endomorphe, que j’ai identifié à la troisième fonction, est fréquemment caractérisé par un estomac protubérant, et une tendance à la gloutonnerie). Le « caractère négatif » de la troisième fonction (que je discuterai en détail plus tard) est illustré par l’action des organes digestifs, qui suppriment l’identité de la matière étrangère et la convertissent en la propre substance du corps.

- Rongeurs, ongulés, et carnivores

Dans l’être humain, les trois systèmes de Schad existent dans un état d’équilibre. Chez d’autres mammifères, cependant, ces systèmes existent d’une manière telle que l’un domine les autres. Schad affirme que les rongeurs (castors, spermophiles, lemmings, souris, taupes, rats, écureuils, etc.) sont dominés par le système nerveux-sensoriel. On peut voir cela non seulement dans leur activité nerveuse frénétique (similaire à celle de l’ectomorphe-cérébrotonique humain), mais aussi dans le fait que leur tête est beaucoup plus grosse et plus développée que leurs membres. Les ongulés (buffles, chameaux, vaches, chevreuils, chèvres, chevaux, cochons, etc.) sont dominés par le système métabolique-membres. Cela se reflète dans leur grande taille. En particulier, leur estomac est habituellement très grand, et leurs membres sont aussi allongés et massifs. Comme l’endomorphe-viscérotonique humain, ils tendent à être passifs, à se déplacer lentement, et aiment manger.

Les carnivores (chats, loups, dauphins, blaireaux, belettes, etc.) sont dominés par le système respiratoire-circulatoire, que Bortoft décrit significativement comme « intermédiaire entre les deux autres [systèmes] » [1]. Il écrit : « Dans leur forme bien proportionnée, dans laquelle aucune partie du corps n’est développée plus que les autres, aussi bien que par leur taille intermédiaire, ils représentent un équilibre actif entre les deux extrêmes du rongeur et de l’ongulé » [2]. Cette description correspond exactement à mon traitement du mésomorphe-somatotonique humain. Les carnivores, comme les guerriers de la deuxième fonction, sont bien sûr caractérisés par une nature de prédateur. Et qui sont les souverains de facto du royaume animal ? Les carnivores, bien sûr.

Schad dit des choses fascinantes sur la vie de ces trois types de conduite des mammifères, et sur leur relation particulière avec la mort. Le rongeur, dit-il, « vit involontairement » et « meurt avec joie ». Sa vie nerveuse hyper-cinétique semble le rendre fatigué de l’existence, et il meurt généralement facilement et sans combat. Le cas extrême serait celui du lemming. L’ongulé, par contre, « vit avec joie » et « meurt involontairement ». L’ongulé meurt mal. Il est souvent difficile à achever, et se débat et proteste bruyamment. Lorsqu’il se trouve face à une menace réelle ou potentielle, le rongeur réagit généralement par la fuite ; l’ongulé réagit par l’« évitement tranquille ». Par contre, le carnivore attaque. « Il s’expose également à la vie ou à la mort. Avec la mort aussi bien qu’avec la vie, il a une relation active ». Plus loin, il nous dit que le carnivore « accepte également la possibilité de la vie ou de la mort » [3]. En termes humains, cette étrange combinaison d’héroïsme et de résignation est typique, bien sûr, du guerrier tel qu’il est classiquement conçu.

- Exemples anatomique : dents et os

Nous pouvons trouver la tripartition même à un niveau beaucoup plus concret, reflété dans le dessin des parties individuelles du corps. Prenez les dents, par exemple : les incisives, les canines et les molaires. Schad nous montre que chez les rongeurs les incisives dominent, chez les carnivores les canines, et chez les ongulés les molaires. Chacun accentue le type de dents dont il a besoin pour sa forme de vie. Mais chez l’être humain, ces trois types sont également développés, parce que nous pouvons manger – et en faire notre subsistance – toutes les nourritures mangées par les rongeurs, les carnivores, et les ongulés.

Ce simple fait nous oriente vers des questions de grande importance concernant la place de l’homme dans l’univers ; son rôle cosmique, si vous voulez. Non seulement les êtres humains possèdent les trois types de dents, également développées, mais, comme je l’ai déjà mentionné, dans l’être humain les trois systèmes corporels (nerveux-sensoriel, respiratoire-circulatoire, et métabolique-membres) sont équilibrés, sans qu’aucun ne domine les autres. Qu’est-ce que cela signifie ? Dans le concept indo-européen traditionnel de la royauté, le roi, bien qu’il vienne d’une caste, était en réalité considéré comme incarnant les trois fonctions. Maintenant, je dirais que l’homme est à la nature ce que le roi est à son royaume. Comme le roi, qui incarne tous les aspects de son royaume dans sa personne, l’homme incarne tous les aspects de la nature. L’homme est à la fois rongeur, carnivore et ongulé. L’homme est le microcosme. Si on peut dire qu’il est le « roi de la nature », sa royauté est une intendance. Son rôle n’est pas d’être un tyran, ni de piller son royaume, mais d’y travailler presque comme un jardinier travaille dans un jardin : s’assurer que le sol est capable de supporter la croissance, planter les graines d’une manière judicieuse, guider la croissance de ses plantes, et bien sûr éliminer les herbes mauvaises et nuisibles.

Comme exemple anatomique supplémentaire de tripartition, considérez les trois types de cellules osseuses. Les ostéoblastes synthétisent les nouveaux os, et réparent les os existants en prenant du calcium dans le sang et en créant des matrices osseuses. Les ostéocytes maintiennent la force osseuse. Enfin, les ostéoclastes dissolvent les os dans le sang afin de briser et de réassimiler les vieilles structures osseuses. Nous avons ici un mécanisme organisateur positif, un mécanisme préservateur, et un mécanisme destructeur négatif. Comme un auteur le remarque, cela correspond étroitement à la trinité des dieux hindous, Vishnou, Brahma, et Shiva [4]. Comme nous le verrons plus loin, ces trois dieux sont conçus comme l’incarnation de forces qui correspondent exactement aux trois fonctions indo-européennes.

- Vie microscopique

Maintenant, pour l’instant je n’ai rien à dire sur les groupes d’animaux autres que les mammifères. Je n’ai rien à dire non plus sur les plantes. Ce sont des domaines pour une réflexion ultérieure. Je dirai cependant quelque chose sur la forme de vie la plus primale, la cellule de base et le micro-organisme.

Il y a différentes sortes de cellules, avec des structures différentes, mais dans la structure basique de chaque cellule nous pouvons voir une tripartition. Le noyau, dont le reste de la cellule reçoit ses ordres de marche, semblerait correspondre à la première fonction. La membrane de la cellule, qui entoure la cellule et la protège, serait la deuxième fonction. Enfin, la mitochondrie, et d’autres structures, qui déconstruisent et assimilent les molécules de nourriture pour fournir de l’énergie à la cellule, semblerait représenter la troisième fonction.

En prenant à nouveau les humains comme exemple, nos corps commencent par être des organismes microscopiques tripartites. Après environ trois semaines, l’embryon humain se développe en une sphère composée de soixante cellules appelées une blastula. La blastula se replie sur elle-même et développe trois structures de base, l’ectoderme, le mésoderme, et l’endoderme. De l’ectoderme se développeront la protection extérieure du corps, l’épiderme, ainsi que le cerveau et le système nerveux. L’ectomorphe est simplement quelqu’un chez qui cette composante prédomine. Le mésoderme se développe en muscles, os, système respiratoire et circulatoire, et est le trait saillant du mésomorphe. Enfin, l’endoderme, qui prédomine dans l’endomorphe, se développe en système digestif, ainsi que dans la parité du système respiratoire et du canal alimentaire.

Si on regarde la structure de la blastula originelle, on découvre que l’ectoderme et l’endoderme naissants sont mis ensemble, pour former la couche extérieure de la blastula. Le mésoderme est le noyau intérieur. Cela suggère le lien entre les opposés polaires de la première fonction et de la troisième fonction. En un certain sens, ceux-ci existent sur un continuum. Les anciens reconnaissaient cela, et c’est pourquoi Platon parlait de sa Dyade Indéfinie comme du Grand et du Petit. Similairement, les deux extrêmes qui s’opposent au milieu dans la doctrine aristotélicienne des vertus sont conçus comme s’ils étaient sur un continuum. Même plus tard, quand l’ectoderme et l’endoderme sont plus complètement différenciés, ces deux sont encore visiblement présents sur un continuum. Et le mésoderme réside encore au centre de l’organisme, à l’intérieur de la coquille extérieure formée par l’ectoderme et l’endoderme.

Que le mésoderme doive se trouver à l’intérieur des deux autres, plutôt que sur le continuum avec eux, est hautement significatif. Cela reflète le caractère spécial de la deuxième fonction : son coté à part, son statut de médiation entre les autres fonctions. De plus, parce que dans la deuxième fonction les deux autres sont harmonisées et réalisées (un point sur lequel je reviendrai plus loin), la deuxième fonction est, d’une certaine manière, la « vérité intérieure » des autres. La position du mésoderme comme noyau intérieur est la vérité intérieure exprimée physiquement.

La tripartition dans le monde physique en général

- Le macrocosme

Le niveau le plus abstrait que nous considérerons sera l’existence en tant que telle. Mais avant d’atteindre ce niveau, regardons d’abord simplement notre monde physique, et ensuite les constituants physiques de ce monde. A nouveau, c’est un domaine dans lequel beaucoup de spéculations sont possibles, et ici je ne peux proposer que quelques suggestions.

Une division triple évidente de notre monde serait celle de la terre, du ciel et de l’atmosphère, et des cieux au-delà. Sur la terre nous trouvons du liquide et du solide, des océans et des continents. La terre est la source d’abondance, de la subsistance. A ce niveau de la réalité, elle est donc la troisième fonction. La coprésence du liquide et du solide représente la coprésence dans la troisième fonction du chaos (« les eaux » sont un symbole pérenne de la force du chaos), et de l’abondance ; l’indéfinition, et la fécondité précise. Le ciel plane au-dessus de la terre. L’atmosphère entoure celle-ci et la protège. Le ciel a souvent représenté une force mâle, et la terre la force féminine. Dans le système germanique, le ciel correspond à Tyr, la terre à Ing. Les deux sont des dieux mâles, mais Tyr fait partie des Ases, Ing des Vanes. De même, je dirais que le ciel et l’atmosphère représentent la deuxième fonction. Il est aussi remarquable que, comme je l’ai montré, la deuxième fonction soit associée à l’inspiration, au sens littéral ; à l’air et à la respiration. La première fonction est représentée par les corps célestes, en particulier le soleil, qui exerce une influence sur la terre depuis en-haut, une influence que les scientifiques commencent seulement à comprendre. Le soleil est aussi un symbole pérenne de la première fonction. Il apparaît dans la République de Platon comme un symbole de l’idéal. Comme je le discuterai brièvement, le soleil joue aussi ce rôle dans la pensée indienne.

- Physique

L’équation d’Einstein E=mc2 décrit l’univers physique en termes d’énergie, de masse, et de lumière. Comme nous le verrons, dans la philosophie indienne la première fonction indo-européenne est identifiée à la lumière, la troisième fonction à la masse, et la deuxième, une fonction de médiation avec l’énergie. La masse ou matière dans la physique contemporaine est décrite comme un « tourbillon d’atomes », de même que, en termes métaphysiques, la troisième fonction est souvent identifiée au chaos, ou au « flux » d’Héraclite. Nous pouvons aussi remarquer que tous les atomes après l’hydrogène sont tripartites, composés de protons positifs, d’électrons négatifs, et de neutrons à charge neutre. L’électron négatif exhibe l’aspect d’indétermination et de « flux » normalement associé à la troisième fonction. Les électrons sont conçus pour être toujours en mouvement (dans le modèle classique, orbitant autour du noyau), de sorte qu’il est impossible d’établir précisément leur position.

Notes

[1] Henri Bortoft, The Wholeness of Nature (Hudson, New York: Lindisfarne Press, 1996), 94.

[2] Ibid., 94-95. Caractères italiques ajoutés.

[3] Schad, 228-229; 216.

[4] Michael S. Schneider, A Beginner’s Guide to Constructing the Universe (New York: HarperCollins, 1995), 55. Schneider identifie en fait les ostéoblastes à Brahma, les ostéocytes à Vishnou, et les ostéoclastes à Shiva. Pour des raisons qui deviendront évidentes, j’ai changé cet ordre.

La métaphysique de la tripartition indo-européenne, Partie 4

La tripartition dans la pensée et le langage humains

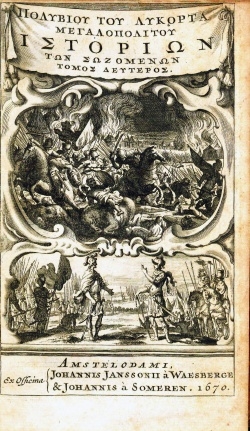

Arjuna

Arjuna

- Universel, particulier, et individuel

Avant de nous tourner vers le niveau de ce qui est purement idéal et transcendant, notre niveau d’abstraction le plus élevé, je parlerai brièvement de la manière dont la tripartition se manifeste quand nous tentons d’incarner l’idéal dans la pensée et le langage.

Avant tout, il y a trois types fondamentaux de noms : l’universel, le particulier, et le singulier. Nous parlons du « loup » comme d’une espèce (ou de la gent « lupine »), et nous parlons des « loups » ou d’« un loup », et nous parlons de loups singuliers ou individuels (par exemple « Fenris »). L’universel représente la troisième fonction en ce qu’elle est une réalité potentiellement illimitée, et, pour cette raison, indéfinie. Il n’est pas sans caractère, mais son caractère n’est pas d’être un individu déterminé. Le particulier représente la première fonction : c’est l’universel rendu plus spécifique et précis. L’universel est un potentiel indéfini pour l’existence multiple. Le particulier réalise le potentiel de l’universel pour l’instanciation. Mais bien qu’« un loup » soit un existant, « un loup » est « un loup » est « un loup », etc. C’est un générique, et donc encore en un certain sens une existence indéfinie. Le singulier, l’individuel, qui serait un loup unique et non un loup générique, a vraiment une existence réelle. Comme la relation du mésomorphe avec l’ectomorphe et l’endomorphe, il fait la médiation entre l’universel et le particulier. C’est une existence particulière élevée au niveau de la réalité pleinement concrète, dans et par la réalisation de certaines des facettes, mais pas de toutes, de l’universel lui-même.

- Jugement perceptuel : identité, différence, et fondement

Dans le perceptuel et toutes les autres formes de jugement, trois concepts prédominent : identité, différence, et le fondement. Nous disons que les choses sont les mêmes ou autres, et nous disons cela dans la conscience d’un certain fondement ou base pour l’identification ou la distinction. Par exemple, deux hommes sont les mêmes, ou différents par la taille, qui est le fondement. Ici, l’identité représente la première fonction qui unit, égalise, rend un. La différence représente la troisième fonction qui divise et désagrège (cela deviendra plus clair quand je discuterai des gunas indiens dans un moment). Le fondement représente la deuxième fonction, faisant à nouveau la médiation entre les deux. Il représente une constante résolue dans le jeu des identités et des différences. Comme la classe guerrière, il fournit la condition même sous laquelle les hommes, ou quoi que ce soit, peuvent être associés ensemble, ou tenus à part.

- Le syllogisme

En logique, nous distinguons entre trois types basiques d’argument ou de syllogisme : la catégorique, l’hypothétique, et le disjonctif. Le catégorique nous permet d’associer des concepts ou d’appliquer des concepts à des cas particuliers. Voici un exemple :

Tous les princes sont des Kshatriyas.

Tous les Kshatriyas sont des guerriers.

Donc, tous les princes sont des guerriers.

Cet argument opère entièrement à l’intérieur du domaine de l’idéal ou de l’abstrait, associant des catégories de choses. Ou prenons cet exemple :

Tous les princes sont des Kshatriyas.

Arjuna est un prince.

Donc, Arjuna est un Kshatriya.

Cet argument subsume un particulier sous un universel. Il inverse l’ordre ontologique des choses. L’existence est une réalisation de l’universel dans le monde, un cas particulier. L’argument catégorique « fait revenir » le cas dans l’universel. Les deux formes de pensée (passer d’une catégorie abstraite à une catégorie abstraite, et subsumer des particuliers dans des universaux) sont caractéristiques de la cérébralité de la première fonction.

Un exemple d’un syllogisme disjonctif serait celui-ci :

Arjuna est chez lui ou il est parti chasser.

Il n’est pas chez lui.

Donc il est parti chasser.

Cette forme d’argument dépend de la distinction nette – de l’exclusion des possibilités, l’une par rapport à l’autre. Elle exhibe donc l’aspect diviseur et fractionneur de la troisième fonction.

Un syllogisme hypothétique ressemble à cela :

Si Arjuna découvre que son fils est mort, alors il cherchera à se venger.

Arjuna a découvert que son fils est mort.

Donc, il cherchera à se venger.

La proposition hypothétique a un but, elle est orientée vers l’action, et conséquente. Elle exprime les conséquences qui s’ensuivront si une condition antécédente est satisfaite. Un syllogisme hypothétique ne subsume pas simplement un particulier dans un universel, il nous dit quelque chose que nous pouvons attendre du monde. Il est intéressant de noter que tous les syllogismes catégoriques peuvent être convertis en syllogismes hypothétiques. Par exemple :

Tous les princes sont des Kshatriyas.

Arjuna est un prince.

Donc, Arjuna est un Kshatriya.

devient

Si quelqu’un est un prince, alors il est un Kshatriya.

Arjuna est un prince.

Donc, Arjuna est un Kshatriya.

Notez la subtile différence que fait la conversion. Elle semble maintenant dire : « Si vous découvrez que quelqu’un est un prince, alors vous pouvez savoir que c’est un Kshatriya, donc faites attention, car Arjuna, qui est un prince, etc.… ». L’hypothétique est un argument mondain, dynamique, et donc il représente la deuxième fonction [1].

En étudiant spécifiquement le syllogisme catégorique, il consiste en termes majeur, mineur, et médian. Pour reprendre le même argument —

Tous les princes sont des Kshatriyas.

Arjuna est un prince.

Donc, Arjuna est un Kshatriya.

— « Kshatriya » est le terme mineur, « Arjuna » est le terme majeur, et « prince » est le terme médian. Le terme mineur est la catégorie la plus large dans cet argument, le plus abstrait des universaux nommés à l’intérieur de lui. De même, suivant mon identification de l’universel avec la troisième fonction, le terme mineur représente aussi la troisième fonction. Le terme majeur donne une spécificité au terme mineur : il nomme un quelque chose spécifique qui appartient au terme mineur (l’universel). De même, du fait de ce rôle de « spécifieur » ou d’« identifieur », le terme majeur représente la première fonction. Le médian relie le mineur et le majeur, puisqu’il est présent dans les deux prémisses. Du fait de cette fonction médiatrice, que j’ai déjà discutée dans d’autres contextes, le terme médian semble correspondre à la deuxième fonction.

— « Kshatriya » est le terme mineur, « Arjuna » est le terme majeur, et « prince » est le terme médian. Le terme mineur est la catégorie la plus large dans cet argument, le plus abstrait des universaux nommés à l’intérieur de lui. De même, suivant mon identification de l’universel avec la troisième fonction, le terme mineur représente aussi la troisième fonction. Le terme majeur donne une spécificité au terme mineur : il nomme un quelque chose spécifique qui appartient au terme mineur (l’universel). De même, du fait de ce rôle de « spécifieur » ou d’« identifieur », le terme majeur représente la première fonction. Le médian relie le mineur et le majeur, puisqu’il est présent dans les deux prémisses. Du fait de cette fonction médiatrice, que j’ai déjà discutée dans d’autres contextes, le terme médian semble correspondre à la deuxième fonction.

Il y a aussi, en général, une tendance souvent notée dans notre pensée à grouper les choses par trois (cela peut être universel, mais je soupçonne que cela pourrait être plus répandu parmi les Indo-Européens). On apprend aux enfants leur « A-B-C », par exemple, pas leur « A-B-C-D ». La plupart des gens ont trois noms : un premier, un médian, et un dernier. Nos histoires et fables abondent de trois : trois ours, trois frères, trois vœux, trois sorcières, trois demi-sœurs laides, trois haricots, trois voies sur la route, etc. De nombreux dictons ou rimes ont trois parties : « Jeannot sois agile ! Jeannot sois rapide ! Jeannot saute par-dessus le chandelier ! » ; Je crie ! Vous criez ! Nous crions tous pour de la crème glacée ! [“I scream! You scream! We all scream for ice cream!”] ; « Menteur, menteur, pantalon en feu ! » [“Liar, Liar, pants on fire!”] ; « Plus de stylos, plus de livres, plus de foutus professeurs ! » ; « Hip ! Hip ! Hourrah ! » ; « Du peuple, par le peuple, pour le peuple » ; « Crac, zim, boum » [Snap, Crackle, Pop], etc. Le mythe indo-européen est rempli de trois. Dans le mythe nordique il y a trois puits, trois racines, trois Nornes, trois frères (Odin, Vili et Vé), trois enfants de Loki, etc. Les Grecs avaient trois parques, trois grâces, une déesse à trois faces (Hécate), un loup à trois têtes (Cerbère), etc. La plupart des traditions indo-européennes parlent aussi d’une bataille entre un héros et un monstre à trois têtes. Il suffit de dire que de même que le monde exhibe la triplicité fondamentale que j’ai décrite, nos esprits pourraient être conçus de manière à ordonner même les choses les plus triviales en modèles triples.

Voir aussi mon article « The Gifts of Odin and His Brothers » [Les cadeaux d’Odin et de ses frères] dans What is a Rune? And Other Essays (San Francisco: Counter-Currents Publishing, 2015) pour une discussion de la structure triple fondamentale de l’esprit humain.

Note

- Il y a certaines raisons de dire que la forme hypothétique « fait la médiation » entre la catégorique et la disjonctive. Examinez les trois formes posées à plat :

Categorical Disjunctive Hypothetical (Modus Ponens)

P are Q P v Q P > Q

R is P -P P

R is Q Q Q

Notez que dans la forme hypothétique, P et Q sont d’abord mis ensemble (comme dans l’argument catégorique) par une implication (« P implique Q ») puis séparés (comme dans l’argument disjonctif), mais pas opposés.

La métaphysique de la tripartition indo-européenne, Partie 5

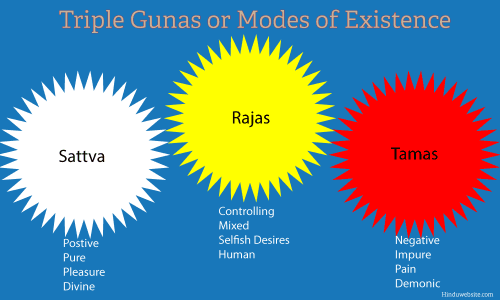

La tripartition et les gunas

- L’émergence des gunas du Brahman

Nous avons manifestement affaire à trois principes qui se manifestent sous différentes formes. Ces principes ont le statut des idées platoniciennes : des formes transcendantes que nous pouvons approcher par leurs diverses expressions dans le monde. Mais pouvons-nous exprimer les trois principes dans l’abstrait ?

Le domaine de recherche le plus évident est celui des traditions philosophiques et mystiques indo-européennes. Ici nous avons de la chance, car il y a beaucoup de sources d’inspiration. Comme on pouvait s’y attendre, la tradition indienne est la source la plus riche. Les anciens Aryens reconnaissaient et discutaient explicitement et exactement ce que j’ai soutenu dans cet article : que toutes les choses exhibent la même structure tripartite.

Ce dont je parle spécifiquement est l’ancienne doctrine des gunas. Guna signifie quelque chose comme « qualité », et cela peut aussi avoir signifié « partie d’un tout ». Guna est donc le même concept désigné dans la philosophie allemande par « moment ». Un moment est une partie d’un tout séparable seulement en pensée. Les gunas sont trois moments de l’Etre, dont nous pouvons parler séparément, mais qui ne peuvent pas réellement exister en séparation.

Les gunas proviennent du Brahman, qui est l’Absolu ou Immensité Transcendante existant au-delà de toute la création. Je comprends le Brahman comme étant le « fondement de l’Etre ». Quel est le fondement sur lequel l’existence ou la création devient elle-même présente ? C’est le Brahman. Pour cette raison, on en parle parfois comme d’un néant. Le brahman est en effet « néant » [« no-thing »], mais ce n’est pas un véritable néant : il doit être réel pour être le fondement sur lequel la figure de la création apparaît.

Par le pouvoir de Maya ou Illusion, le mouvement apparaît dans cette immensité transcendante du néant. Ce mouvement a, par nécessité, trois et seulement trois formes : centripète, centrifuge, et orbitante (mouvement autour d’un point). Comme le remarque Alain Daniélou : « cette triade imprègne toutes choses et apparaît dans tous les aspects de l’univers, physique aussi bien que conceptuel » [1].

- Sattva, Tamas, et Rajas

La force centripète d’attraction crée la cohésion, ou agrégation. Les hindous l’appellent Sattva ou « existence », car toute existence est une agrégation [d’éléments différents]. Le Sattva est donc le principe d’unité, ayant une fonction liante ou préservatrice. Il est figuré par la lumière, et comme le Soleil. Il est associé à l’intelligence, et avec le rêve. Il devrait être évident qu’il s’agit de la première des fonctions indo-européennes. Le Sattva est incarné par le dieu Vishnou, le « Préservateur ».

La force centrifuge est l’opposée de Sattva. Ce n’est pas une force d’attraction, mais de répulsion. Ce n’est pas une force de cohésion, mais de dispersion, d’annihilation, et de retour dans l’Immensité. Elle empêche la concentration. Cette force est appelée Tamas, obscurité ou inertie. Le Tamas est l’obscurité, parce que là où il y a dispersion il y a dispersion d’énergie, et donc absence de lumière. De même, à cause de cette association avec le chaos, l’obscurité, et l’absence d’unité, il s’agit de la troisième fonction. Le dieu Rudra incarne le Tamas. Il est aussi appelé Shiva, le destructeur et seigneur du sommeil. Le Tamas ou Shiva est considéré comme la nature intérieure de toutes choses, puisque toutes choses sortent de la désintégration, pour ensuite se désintégrer à nouveau. Comme le Sattva, le Tamas est associé au sommeil, mais cette fois c’est un sommeil sans rêves – un sommeil sans formes ni images.

L’équilibre entre le Sattva et le Tamas donne naissance à une troisième force, le Rajas. En cosmologie, c’est le mouvement tournant, circulaire (que, soit dit au passage, les Grecs associaient à la perfection). Rajas signifie « activité ». C’est la source de toutes les formes et espèces différentes de la création. Tout mouvement rythmique – le type de mouvement exhibé par la vie – vient du Rajas. A la différence du Sattva et du Tamas, le Rajas n’est pas lié au sommeil, mais à la conscience éveillée. Le Sattva est associé à la forme ou à l’intelligence, le Tamas à la masse ou à la matière, et le Rajas à l’énergie. Ces associations correspondent étroitement au soufre, au sel et au mercure de Paracelse. Chose intéressante, le Rajas est considéré comme incarné dans Brahma, qui est le singulier nominatif masculin de Brahman, c’est-à-dire la personnification du Brahman. Le Rajas est évidemment la deuxième fonction indo-européenne.

Daniélou remarque : « L’une ou l’autre des trois tendances prédomine dans chaque sorte de chose, dans chaque espèce d’être » [2]. Nous avons vu cela dans les êtres humains, dans la tendance de certains hommes à être rationnels ou spirituels, d’autres passionnés, et d’autres appétitifs. Et cette doctrine des types humains peut justement être trouvée dans la psychologie tantrique. D’après le Tantra, les hommes appartiennent au Sattva, au Rajas, et au Tamas. Seuls les deux premiers sont aptes à entreprendre des pratiques spirituelles.

- Divya, Vira, et Pashu

L’homme du Tamas (troisième fonction) est appelé Pashu, qui signifie « animal ». Pashu vient de « pac », lier. Le Pashu est lié à des désirs animaux – faim, sexe, confort, avidité – ainsi que par la convention sociale (à ce propos, c’est précisément de cette manière que les Grecs regardaient l’homme appétitif : ils le voyaient largement comme un animal ; comme non pleinement humain). Le tantrisme soutient que dans l’âge actuel, qui est appelé le Kali Yuga, le type Pashu prédomine.

L’homme du Sattva (première fonction) est appelé Divya, un « être divin ». Comme le Pashu, il est en un certain sens non-humain, parce qu’il est plus qu’humain. Cet homme suit un chemin intérieur, se détachant du monde. Le Divya est très rare dans le Kali Yuga.

L’homme du Rajas (deuxième fonction) est appelé Vira. Ce mot vient de la racine indo-européenne vir- dont viennent les mots modernes viril et vertu. Le vira est un être humain pleinement réalisé : un être viril et héroïque. Il y a des viras de la main droite et des viras de la main gauche. Le vira de la main droite est héroïque mais dépourvu de sens critique. Il combat pour des idéaux qu’il a à peine examinés, et se met au service de l’autorité qu’il ne conteste jamais. En fait, avec le vira de la main droite, la soumission à l’autorité et l’accomplissement aveugle du devoir sont considérés comme les vertus suprêmes.

Le vira de la main gauche peut commencer dans cet état, mais, comme le Divya, il suit un chemin intérieur. Il peut être comparé à l’idéal taoïste chinois du « guerrier lettré ». Julius Evola écrit : « Montant des niveaux inférieurs aux niveaux supérieurs, les viras sont soumis à toujours moins de limitations et de liens » [3]. Le vira atteint un point au-delà du bien et du mal, où il devient autonome au sens littéral de se donner une loi à soi-même. L’idéal pour le vira de la main gauche, et donc l’idéal humain tout court, est l’indépendance, l’autosuffisance, la complétude, et le détachement. Ce sont des caractéristiques que nous retrouvons dans la tradition grecque, dans le concept aristotélicien de Dieu, le Moteur Immobile. Pour Aristote, l’homme idéal approche le plus possible des qualités du Moteur Immobile. Dans le Tantra, l’homme idéal est celui qui incarne le plus pleinement Brahma, l’incarnation du Rajas.

Le fait que le mot « vertu » soit dérivé de la même racine que vira est très significatif. Avant tout, il suggère un lien inattendu entre virilité et vertu, ou entre masculinité et vertu. La conclusion évidente à tirer est que les anciens considéraient les vertus comme des réalisations masculines. Cela se confirme si nous nous tournons vers Aristote. Le mot grec normalement traduit par le mot latin vertu est arete, qui est peut-être le mieux traduit par « excellence ». Dans son Ethique à Nicomaque, Aristote discute la nature de l’homme vertueux, et ne lie nulle part ses observations à la femme. De plus, Aristote conçoit la vertu comme un milieu entre deux extrêmes. Par exemple, le courage est un milieu entre la lâcheté et l’irréflexion. Le vira indien – qui, comme je l’ai dit, est le type guerrier mésomorphe et somatotonique – est une sorte de milieu entre le Divya et le Pashu. En effet, tout ce qui est analogue à la deuxième fonction indo-européenne occupe une position médiane entre les deux autres fonctions. Si nous regardons la liste des vertus d’Aristote, son milieu entre les extrêmes équivaut à une description du vira. Je soupçonne que les deux extrêmes opposés au milieu décriront aussi très bien les caractéristiques du Divya et du Pashu.

Ceux chez qui le Tamas prédomine, les Pashus, adorent des fantômes et des esprits (Bhuta et Preta). Ceux chez qui le Sattva prédomine, les Divyas, adorent les Devas. Ceux chez qui le Rajas prédomine, les viras, adorent les génies (Yakshas) et les anti-dieux (Asuras). Ce dernier fait est extrêmement intéressant, car le terme Asura est relié au vieux-norrois Aesir [= Ases], qui est le nom du groupe des dieux de première et de deuxième fonctions dans la tradition germanique : Odin, Thor, Tyr, etc.

D’après le Tantra, le Tamas est en réalité le chemin vers l’illumination. Mais en dépit du fait qu’il est une créature du Tamas, le Pashu ne peut pas en tirer avantage. Le Tamas est annihilation et absence d’unité. Souvenez-vous qu’il est aussi associé au sommeil profond, sans rêves. La voie de l’illumination, de la compréhension du fondement ultime de toutes choses, l’Immensité transcendante du Brahman, passe par l’annihilation et la multiplicité. Sur le plan de l’action, le vira détruit avec son épée. Le vira de la main gauche tourne son pouvoir vers l’intérieur, et détruit le jeu de la multiplicité dans sa propre âme. Il tente d’atteindre un état comme celui du sommeil sans rêves, mais dans un état d’éveil, sous son contrôle. D’où l’usage de la méditation, et de pratiques conçues pour parvenir à la maîtrise totale du corps, comme les diverses formes de yoga et d’arts martiaux.

Mais le monde externe des choses et le monde interne des pensées et des images sont tous deux issus de Sattva, la force centripète. Tout ce qui s’oppose à Sattva s’oppose au monde lui-même, et à l’intention du créateur. « Le but de tout créateur est d’empêcher une compréhension qui détruirait sa création », note Daniélou. « C’est pourquoi [il est dit que] ‘l’Ame [l’Atman, le vrai Soi] n’est pas à la portée du faible’. Elle doit être conquise en s’opposant à toutes les forces de la nature, à toutes les lois de la création » [14]. Ainsi, celui qui cherche l’illumination doit devenir un guerrier contre toute la création, en fait contre les dieux eux-mêmes. C’est pourquoi l’homme le plus adapté à la quête de l’illumination doit être l’homme qui répond à la description du vira de la main gauche – du moins, c’est le cas dans le Kali Yuga.

Notes

[1] Alain Danielou, The Myths and Gods of India (Rochester, Vermont: Inner Traditions, 1991), 22.

[2] Ibid., 27.

[3] Julius Evola, The Yoga of Power, trans. Guido Stucco (Rochester, Vermont: Inner Traditions, 1992), 55.

[4] Danielou, 33.

La métaphysique de la tripartition indo-européenne, partie 6

F. W. J. Schelling et la tripartition indo-européenne

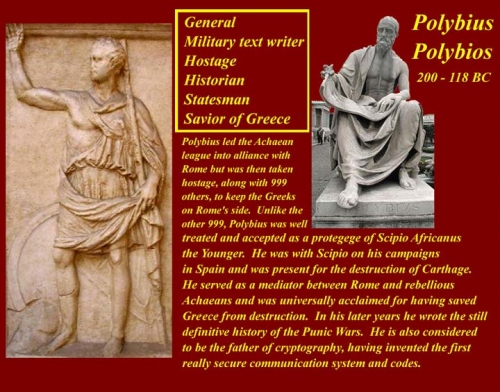

Friedrich Schelling, 1775–1854

Friedrich Schelling, 1775–1854

- Les influences de Schelling : la Trinité chrétienne et Jacob Boehme

Je me tourne finalement vers une tradition indo-européenne différente, celle de l’Idéalisme allemand du XIXe siècle. J’inclus ce matériel afin de prouver le caractère pérenne de la pensée indo-européenne. On pourrait dire que toute l’histoire de la philosophie occidentale (et indienne) est une longue et inconsciente tentative pour retrouver la sagesse connue « directement » par nos ancêtres indo-européens.

Remarquablement, dans la philosophie tardive de F. W. J. Schelling, qui était un ancien copain d’école de Hölderlin et Hegel, nous trouvons une doctrine qui correspond exactement à l’ancienne théorie aryenne des gunas. Ceci en dépit du fait que Schelling avait, autant que nous le sachions, une faible connaissance de la philosophie indienne. Il écrivait à une époque où les détails de la pensée indienne commençaient seulement à être connus des intellectuels européens. Les détails ésotériques des gunas n’étaient certainement pas connus de Schelling, et pourtant il écrit comme s’il les traduisait dans le langage de la philosophie idéaliste.

Spécifiquement, je parle de la Potenzlehre de Schelling, une doctrine des Puissances, qu’il développa durant toute sa carrière, mais qui ne s’épanouit pleinement que dans sa tardive et dénommée « philosophie de la mythologie ». Pour pleinement comprendre cette doctrine, on doit explorer ses antécédents dans la tradition mystique occidentale. Avant tout, Schelling, Hegel et les philosophes allemands en général étaient fascinés par le mystère de la Trinité chrétienne. On pourrait démontrer que ce que nous connaissons sous le nom de « la Trinité » n’est pas une conception proche-orientale originale mais en réalité un résultat de la « germanisation » du christianisme, développée après la conversion de nos ancêtres païens. L’idée de trois « personnes » en une seule correspond à peu près à la notion aryenne de l’unité des trois gunas dans le Brahman. Sans trop entrer dans les détails, je suggérerais que le Père correspond à la première fonction indo-européenne, le Fils à la troisième fonction, et le Saint Esprit à la deuxième fonction. En cela je suis influencé par Hegel, qui traitait le Père comme le logos, ou Idée Absolue, le Fils comme la Nature, et le Saint Esprit comme l’homme, qui est l’unité du logos et de la nature, ou de Dieu et de l’animal [1].

L’influence mystique immédiate sur Schelling fut l’Allemand Jacob Boehme, qui concevait toute la réalité comme possédant une structure triple. Considérez la citation suivante de Boehme :

« Ainsi donc la lumière éternelle, et la vertu de la lumière, ou paradis céleste, se meut dans l’obscurité éternelle ; et l’obscurité ne peut pas comprendre la lumière ; car ce sont deux Principes [séparés] ; et l’obscurité désire la lumière, parce que l’esprit s’y contemple lui-même, et parce que la divine vertu est manifestée en elle. Mais bien qu’elle n’ait pas compris la divine vertu et la lumière, elle s’est cependant continuellement et ardemment élevée vers elle, jusqu’à ce qu’elle ait allumé la racine du feu en elle-même, à partir des rayons de la lumière de Dieu ; et alors naquit le Troisième Principe, sortant de la matrice obscure, par la spéculation de la vertu [ou puissance] de Dieu. » [2]

Il y a donc trois principes, un de lumière, un d’obscurité, et un qui réconcilie. Boehme conçoit les trois principes comme étant réunis au sein de ce qu’il nomme l’Ungrund : le fondement transcendant et ineffable de tout l’être qui est lui-même sans fondement, parce qu’il n’y a rien au-delà de lui qui pourrait servir de fondement. A nouveau, nous avons une correspondance avec l’existence des gunas à l’intérieur du Brahman. Boehme conçoit ses trois principes comme imprégnant toute la réalité [3]. L’homme, affirme-t-il, est la véritable réalisation des trois principes. A cause de la coprésence des trois principes dans l’homme, ce dernier a le potentiel pour comprendre l’ensemble de la création.

- Les Trois Puissances

Tournons-nous maintenant vers Schelling : celui-ci parle de Trois Puissances, qu’il conçoit comme des principes ou des idéaux, et comme des agences de volition. Schelling a une manière particulière et algébrique de parler des Puissances comme –A ou A1, +A ou A2, et A3. J’abandonnerai cet usage, et je ferai une nouvelle violence à la terminologie de Schelling en parlant de la première puissance comme étant la troisième, la seconde comme étant la première, et la troisième comme étant la seconde. L’idée est de faire apparaître les corrélations avec les fonctions indo-européennes. Ma présentation ne fera cependant pas violence aux idées de Schelling.

Schelling conçoit un temps primordial où les trois puissances existaient par elles-mêmes, avant qu’elles puissent s’exprimer dans un monde d’objets. De plus il voit les puissances comme des aspects de l’Absolu – l’équivalent du Brahman dans sa philosophie.

La Troisième Puissance est conçue par Schelling comme une pure et indéfinie possibilité d’être (das sein Koennende). C’est une sorte d’« être-en-soi » primal, qui est indéfini, illimité, et négatif. Il possède, affirme-t-il, un pur pouvoir d’auto-négation. Il peut annuler ou rejeter tout ce qu’il est et devenir n’importe quoi d’autre. Il n’a pas d’identité fixée. Les parallèles philosophiques incluent le flux d’Héraclite, et l’apeiron d’Anaximandre. Il correspond à peu près au Yin chinois, et est donc le principe féminin. Schelling conçoit aussi cette Puissance comme de la pure subjectivité. La Troisième Puissance est manifestement équivalente au Tamas indien.

La Première Puissance est un principe d’ordre et d’objectivité. Elle est l’opposée de la Troisième Puissance : spécifique, légale, précise, distincte. C’est le principe de l’identité, et de la différentiation. La Première Puissance est être pur, par opposition à la pure possibilité de l’être. Sa fonction est de placer des « limites » autour du chaos qui est la Troisième Puissance, et de faire exister des entités précises. Alors que la Troisième Puissance est das sein Koennende, « l’être possible », la Première Puissance est das sein Muessende, « l’être obligé ». La Troisième Puissance est « être-en-soi », mais la Première Puissance est « être-en-dehors-de-soi », parce que les limites fournies par la Première Puissance sont en-dehors d’elle, placées autour d’une autre. C’est donc un principe mâle, équivalent au Yang chinois, et au Sattva indien. La raison en est simple : la nature de la femelle est de générer en elle-même, la nature du mâle est de générer dans un autre (donc, « être-en-dehors-de-soi »). Parce que la Première Puissance est pure objectivité et non subjectivité, elle ne possède pas de volonté propre, ce qui est l’une des facettes d’un sujet.

Ces deux Puissances ne peuvent coexister parce qu’elles sont des opposés totaux. Sans elles, il ne peut y avoir de monde. Donc quelque chose d’autre doit fonctionner pour les réunir. Entrez ce que j’appelle la Seconde Puissance, simplement pour l’identifier avec la deuxième fonction indo-européenne. A nouveau, tout ce qui correspond à la deuxième fonction constitue une sorte de milieu entre les première et troisième fonctions. Ainsi, la Seconde Puissance doit posséder un être objectif (comme la Première Puissance), mais avec la possibilité de changement (comme la Troisième Puissance). Pour le dire d’une autre manière, la Seconde Puissance doit être quelque chose de précis, mais elle doit aussi être libre.

La Troisième Puissance est pure subjectivité, et la Première Puissance est pure objectivité, donc d’une manière ou d’une autre la Seconde Puissance unira sujet et objet. Ce fait est significatif, car Schelling conçoit l’Absolu comme le « point d’indifférence » entre sujet et objet. Il y a ici une correspondance exacte, encore une fois, avec la théorie indienne des gunas. Le vira est l’homme dans lequel le Rajas prédomine, et la personnification de Rajas est Brahma. Ainsi, c’est le vira qui est dans la position unique d’atteindre le Brahman lui-même par une transformation de sa propre nature. Chez Schelling, la Seconde Puissance, qui correspond au Rajas, est la réunion du sujet et de l’objet, alors que l’Absolu, qui correspond au Brahman, est la transcendance du sujet et de l’objet. C’est comme si la Seconde Puissance était l’Absolu « tourné vers l’intérieur », et vice-versa. L’implication semble être que celui qui s’identifie à la Seconde Puissance, ou Rajas, peut s’élever vers l’Absolu, ou Brahman, par une sorte d’héroïque changement de Gestalt.

Alors que la Première Puissance est « être en-dehors de soi », et que la Troisième Puissance est « être en soi », la Seconde Puissance est « être avec soi ». Ce choix des mots suggère que dans la Seconde Puissance il y a une sorte de totalité, d’accomplissement, de réconciliation, et d’autosuffisance [4]. Schelling remarque plus loin que si la Troisième Puissance est l’Illimité, et la Première Puissance est le Limitant, la Seconde Puissance est le « purement autolimitant ». Ici encore, nous voyons une anticipation métaphysique du vira. J’ai dit plus haut que le vira atteint un point où il devient autonome au sens littéral de se donner une loi à soi-même. C’est l’autolimitation dans sa forme la plus élevée. Le vira est autonome, indépendant, autosuffisant, et complet, tout comme la Seconde Puissance primale. La Troisième Puissance est « l’être possible », la Première Puissance est « l’être obligé », et la Seconde Puissance est das sein Sollende, « l’être qui devrait ». Sollen signifie « devrait », et donc dans la Seconde Puissance une dimension éthique ou idéaliste apparaît. C’est prévisible, puisque la Seconde Puissance se manifeste au niveau humain dans l’homme « passionné ».

Si nous pouvons parler de la Troisième Puissance comme étant la matière ou élément matériel, et de la Première Puissance comme étant la forme, alors qu’est-ce que la Seconde Puissance ? Encore une fois, puisqu’elle constitue une sorte de milieu entre les deux autres, en un certain sens la Seconde Puissance doit être une union de la matière et de la forme. Je me souviens ici de la théorie hégélienne des trois types d’art : symbolique, classique, et romantique. Le symbolique est l’art qui est excessivement formel, stylisé, et contraint. Il prend l’art égyptien comme exemple. L’art romantique se soucie avant tout de soulever des émotions et de soupeser des mamelles : un art qui a perdu toute retenue. Ici, la forme est brisée ou dépassée par un excès de contenu ; par un sentiment sans contraintes. L’art classique occupe une position moyenne, une unité parfaite de la forme et du matériel. Et qu’utilise Hegel comme exemple de l’art classique ? Les sculptures grecques de dieux et d’athlètes, bien sûr. En d’autres mots, des mésomorphes : des corps de deuxième fonction gouvernés par le Rajas, ou la Seconde Puissance schellingienne. Dans tout ce qui occupe la position de deuxième fonction, il y a une complémentarité presque parfaite de la forme et de la matière, de la raison et de l’émotion, des forces centripètes et centrifuges, etc.

La Seconde Puissance est donc l’union primale et parfaite de la forme et de la matière. C’est la forme platonicienne d’un dieu (et il faut répéter que les Grecs utilisaient le mésomorphe, la parfaite union humaine de la forme et de la matière, pour représenter leurs dieux), alors que la Première Puissance et la Seconde Puissance sont de simples forces (comme l’« amour » et la « haine » d’Empédocle). La Seconde Puissance est l’union éternelle des deux autres Puissances. Quand les trois Puissances s’extériorisent dans la création, la relation éternelle entre elles s’exprime d’une manière temporelle. Le monde est simplement la réunion et la séparation de la Première Puissance et de la Troisième Puissance, Sattva et Tamas, étendues dans le temps. L’agent ultime de ce processus dans le monde est le vira, l’homme de la deuxième fonction, qui est à la fois préservateur et destructeur. Edward Allen Beach, parlant de la Potenzlehre de Schelling, dit que « [la Seconde Puissance] est … la cause finale [aristotélicienne] ou but final vers quoi tend tout l’organisme idéal de l’univers » [5].

- Les Anti-Puissances

Schelling appelle les trois Puissances prises ensemble « la figure de l’être ». Mais l’histoire ne se termine pas ici, car Schelling dit que l’exposé jusqu’ici n’est qu’un exposé d’essences pures. Comment exactement un monde spatio-temporel concret vient-il à l’être, à partir de ces Puissances ? J’ai parlé un peu plus haut des Puissances s’extériorisant dans la création. Mais comment cela a-t-il lieu ? La réponse de Schelling à cela est très obscure.