Author’s Note:

This is transcript by V. S. of a talk that I gave to the Atlanta Philosophical Society in 2000. As usual, I have eliminated some wordy constructions and some back-and-forth with the audience.

We live in a time when there’s a lot of talk about the ends of ages. Last year, at the end of 1999, the vast majority of people celebrating the New Year were celebrating the millennium a year early. But still, there’s a sense that when we reach a round number something important is going to happen. There’s a lot of talk about the “end of modernity” in academia today. So-called postmodernist philosophers and literary critics are quite popular, and certain religious thinkers and writers are of course concerned that time itself may end very soon.

A friend of mine who is an Orthodox monk in Bulgaria emailed me just before the New Year saying that not only did some people in Bulgaria think that all the computers were going to fail, they thought the end of time was at hand. I wrote back saying, “Well, if I don’t hear from you again, it’s been nice knowing you.”

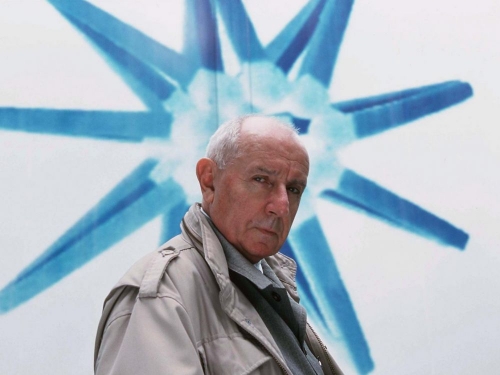

I want to talk about one of the most stunning claims that history is over, namely the claim popularized by Alexandre Kojève, a 20th-century philosopher who I think is probably the most influential single philosopher in the 20th century, although at the same time he’s one of the least known. He’s influential not only in the world of ideas but also in the world of politics. In fact, he’s had an enormous influence on the post-Second World War global economic and political order that we live in today. People sometimes call it the “New World Order.” It’s very much influenced by his thought and action.

Kojève claimed that history is not about to end, but that it had already ended, and that it ended in 1806. So, all of the expectant people who are waiting for the millennium have already missed it. History is already over. It’s been over for nearly two centuries, and it came to an end in 1806 when Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel was sitting in his study in Jena writing his book Phenomenology of Spirit and nearby Napoleon was defeating his enemies at the great Battle of Jena, which turned the tide of resistance in Europe toward the ideas of the French Revolution.

According to Kojève, history ended with the triumph of the ideals of liberty, equality, and fraternity and Hegel’s understanding of the significance of these events. Everything that’s happened since then, he said, including the two World Wars, is just post-historical “mopping up.” It’s of no real historical significance. It’s just a matter of carrying the ideals of the French Revolution to the furthest corners of the globe.

Last night I saw a trailer for a film called The Cup, which is set in Bhutan in the Himalayas. This is a movie about the mopping-up process. It’s about some intrepid young Buddhist monks who fall in love with soccer and decide to bring satellite television to Bhutan. According to Kojève, this is just the kind of mopping-up process you’d expect as the world becomes completely integrated and its culture becomes entirely homogenized. Of course, this is presented as a heart-warming tale of intrepid youth.

Now, who was Alexandre Kojève? He was born in 1902 as Aleksandr Vladimirovič Koževnikov. He was born in Moscow to a very wealthy family. After the Russian Revolution, the family fell on hard times, and he was eventually reduced to selling black-market soap on the street. He was arrested for this and narrowly escaped execution. His experiences with the GPU led to a rather unusual outcome. He converted to Marxism and maintained that he was an ardent Stalinist to the very end of his life.

Now, who was Alexandre Kojève? He was born in 1902 as Aleksandr Vladimirovič Koževnikov. He was born in Moscow to a very wealthy family. After the Russian Revolution, the family fell on hard times, and he was eventually reduced to selling black-market soap on the street. He was arrested for this and narrowly escaped execution. His experiences with the GPU led to a rather unusual outcome. He converted to Marxism and maintained that he was an ardent Stalinist to the very end of his life.

In 1920, ardent Marxist-Stalinist that he was, he still saw fit to flee the Soviet Union to Germany. He enrolled at the University of Heidelberg, studying philosophy with the great German existentialist thinker Karl Jaspers, and he wrote a dissertation on Vladimir Soloviev, a Russian mystical philosopher of some interest, although he is rather unknown in the West.

Apparently, the Koževnikovs had money abroad, so while he was in Germany Kojève was actually something of a bon vivant. He lived the high life. He was a sort of limousine Stalinist. But he invested his family money poorly, and in 1929 he was pretty much wiped out by the great stock market crash.

In that year, he moved to France and started trying to find work. He had many friends, Russian émigrés, who helped him out. One of them was Alexandre Koyré, who was a historian of philosophy and science who had to go off to Egypt as a visiting professor and got Kojève the job in 1933 of subbing for him in a seminar on Hegel’s Phenomenology of Spirit.

Kojève did such a spectacular job that he gave the seminar every year until 1939, when the Germans moved in and French intellectual life changed somewhat. Kojève spent the war in the south of France, writing, and some of the works that he wrote during the war were published posthumously. He probably sat out the war because he realized that it was of no historical significance.

In 1945, he returned from his exile and was immediately given a position in the French Ministry of Economic Affairs, the head of which had been a student in his Hegel seminar during the 1930s.

From 1945 to 1968, he held the same position, a kind of undersecretary position, yet while he did not have any official leadership role, he was—as one person who knew him put it—the Mycroft Holmes of the French government. He was the guy who knew everything and everybody, and kept everybody abreast of everything else. He was a nerve center or brain center for the French government for a period of more than 20 years.

He claimed, in his typically hyperbolic style, that de Gaulle took care of foreign affairs, and “I, Kojève,” as he put it, “took care of everything else.” And apparently Raymond Aron, who was another of his students and an extremely sober fellow, actually said that this was pretty much true, that Kojève was probably second only to de Gaulle in importance in the French government in the 22 years that he occupied his position.

And what did he do? Well, he was one of the architects of what’s now called the European Economic Community. He was also one of the architects of what is known as the General Agreement on Trades and Tariffs, or GATT.

Right after the Second World War, he gave a speech to a bunch of technocrats in West Germany, where he laid out the model for what was then called pejoratively “neo-colonialism.” In his terms, colonialism after the Second World War and the end of the old colonial empires would now take the form not of taking, but of giving, namely of investing in and developing the underdeveloped countries, the former colonies, and integrating them into the world economic system. His model was basically carried out to a T. Organizations like the World Bank basically follow to this day the Kojèvian model of neo-colonialism.

He was also the first person to announce what is sometimes called the convergence thesis. Zbigniew Brzezinski, National Security Adviser to Jimmy Carter, is often credited with this view. The convergence thesis is basically that as the Cold War wore on, the pressures of fighting it would cause both sides to gradually converge and become indistinguishable from one another.

He was also the first person to announce what is sometimes called the convergence thesis. Zbigniew Brzezinski, National Security Adviser to Jimmy Carter, is often credited with this view. The convergence thesis is basically that as the Cold War wore on, the pressures of fighting it would cause both sides to gradually converge and become indistinguishable from one another.

Kojève was instrumental in creating—through the economic and political integration of the Western, non-Communist nations—one of the most important factors in helping them win the Cold War, but the French intelligence service believed that he was passing information to the KGB the whole time. So he was playing both sides in a very dangerous game. I want to give some suggestions about what Kojève’s dangerous game actually was.

Before I do that, though, I want to talk about his influence in the world of ideas. I’ve talked about his political activity. Really, of all the philosophers in the 20th century, he’s had the most impressive record of actually changing the world instead of just theorizing about it. Much of the world that we know today and think of as normal was influenced by this strange Russian. So, we need to understand the ideas behind his actions.

Kojève’s students at his Hegel seminar in the 1930s included the following people: Raymond Aron, who was probably the most brilliant conservative political theorist in France in the 20th century; Maurice Merleau-Ponty, who was something of a Marxist-Stalinist at one time and one of the most significant phenomenological philosophers in 20th-century France; Jacques Lacan, the great interpreter of Freud, who fused Freud with Kojève’s Hegel and is probably the leading Freudian thinker after Freud; Henry Corbin, who made the first (partial) French translation of Heidegger’s Being and Time but is far more famous for the work that he did in medieval Arabic philosophy and mysticism; Robert Marjolin, who was the leader of the French Ministry of Economic Affairs, the guy who gave Kojève his job; Gaston Fessard, who was little-known outside France but was an extraordinary scholar and a Jesuit priest as well; André Breton, who was one of the founders of French Surrealism; Georges Bataille, famous for writing really rather gross and I think quite untitillating pornography, as well as many books and essays on the philosophy of culture—a rather profound although difficult and quite perverted thinker; and Raymond Queneau, a novelist whose most famous novels are translated as The Sunday of Life and Zazie in the Metro—these are “end of history” novels and were very much influenced by Kojève’s vision of life at the end of history.

And of course these members of the seminar in turn had their own students and readers. Among them are some of the most important 20th-century French thinkers of the next generation: Jacques Derrida, Michel Foucault, Gilles Deleuze, Jean-François Lyotard, and the like. None of them were students of Kojève himself, but I would maintain that nobody can really understand these French postmodernists—especially their use of certain words like “metaphysics,” “modernity,” “difference,” and “negativity”—without understanding how all of these derive from Kojève’s interpretation of Hegel. The peculiar vehemence with which terms like “metanarrative,” “history,” “being,” “absolute knowledge,” and so forth are spoken by these writers has everything to do with Kojève’s specific interpretation of the meaning of these terms in Hegel’s Phenomenology of Spirit. One can’t read French postmodernism and understand it without understanding that most of these thinkers are reacting to Kojève. They would not call themselves Kojèvians. They’re all anti-Kojèvians. But insofar as they’re opposing themselves to him and to his very peculiar takes on things, they’re very much influenced by him. They bear the trace of Kojève.

Another contemporary thinker who’s really quite trendy today is the Slovene writer Slavoj Žižek. I hope there are no Slovenians in the audience who will knock my pronunciation. Žižek has written quite a number of books with titles like Everything You Always Wanted to Know About Lacan . . . But Were Afraid to Ask Hitchcock, and he’s enormously influenced by Kojève’s view of Hegel, and also Lacan’s reading of Kojève’s Hegel.

Another contemporary thinker who’s really quite trendy today is the Slovene writer Slavoj Žižek. I hope there are no Slovenians in the audience who will knock my pronunciation. Žižek has written quite a number of books with titles like Everything You Always Wanted to Know About Lacan . . . But Were Afraid to Ask Hitchcock, and he’s enormously influenced by Kojève’s view of Hegel, and also Lacan’s reading of Kojève’s Hegel.

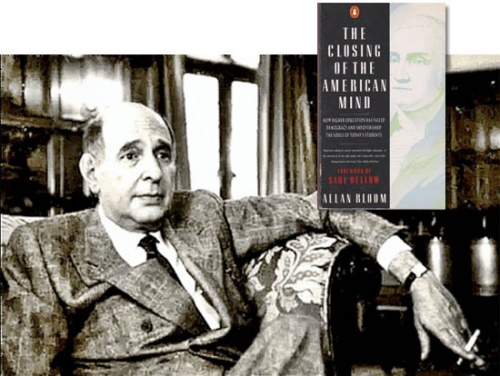

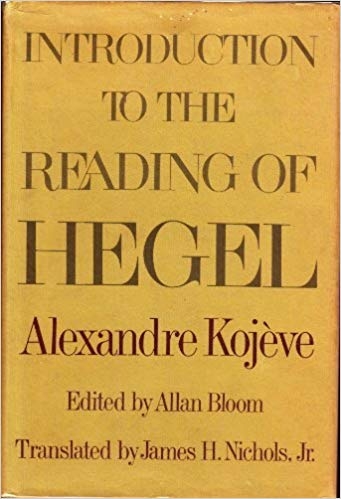

Kojève attracted students even after he stopped teaching. Two of them were Allan Bloom, the author of The Closing of the American Mind, and Stanley Rosen, who is a very well-known commentator on Greek philosophy, as well as on Hegel and Heidegger. Their teacher, Leo Strauss, sent them to study with Kojève in the early 1960s. Bloom and Rosen would go to his office at the Ministry. He would close the door, and they would talk philosophy.

More recently, Francis Fukuyama, who was a student of Allan Bloom, became famous for his book The End of History and the Last Man, which is really a popularization of Kojèvian ideas. Just as the Communist regimes in Eastern Europe were coming down, Fukuyama raised the question: What if Kojève was wrong and history hadn’t ended in 1806, as Hegel wrote the Phenomenology of Spirit? What if history ended in 1989, as Communism fell and Fukuyama was in the process of interpreting it as the global triumph of Western liberal democracy? That started a huge debate.

Of course, people on the Right in America were particularly delighted to hear that their perseverance in the Cold War had brought about not just the end of Communism but the end of history itself, and everything would be smooth sailing from then on. Little things like the Gulf War were just mopping-up.

Some of Kojève’s peers—people that he corresponded with and interacted with and influenced him—include Leo Strauss, who is one of the most important 20th-century philosophers. He was a German-Jewish philosopher who met Kojève in the 1920s. They met again in Paris in the 1930s, where they spent a lot of time together, and they corresponded throughout the rest of their lives. Strauss, of course, was a conservative thinker, a thinker of the Right, and yet he derived both pleasure and knowledge from his friendship with Kojève, the ardent Stalinist.

Carl Schmitt was the notorious German jurist and political philosopher who wrote the brief showing how Hitler’s seizure of power in 1933 was perfectly legal according to the Weimar constitution—which was indeed a brief anybody could have written because, strictly speaking, it was legal. Schmitt, of course, had been tarred with the Nazi association until he died at a very old age recently. Schmitt was a friend of Kojève’s, and they corresponded over a period of many decades. Another improbable intellectual friendship.

Georges Bataille was not just a student of Kojève, but really a peer. I think Bataille dramatically influenced Kojève’s intellectual development. Bataille is certainly a thinker of the far Left.

So, we have a strange phenomenon: Kojève had close intellectual relationships with, and a powerful influence on, thinkers on the Right and on the Left, but the thing that all of these thinkers have in common is a vehement rejection of modernity, precisely the modernity that Kojève himself is so eager to proclaim as inevitable. All of Kojève’s students and most passionate admirers ended by rejecting, vehemently, his vision of the end of history. That’s an interesting thing to puzzle through.

If Hegel and Kojève believe that history came to an end in 1806, then they obviously mean something very different by “history” than all of us do. If history can come to an end, it has to be something different from what is reported every day in the newspapers. They didn’t claim that human events would cease. There are post-historical human events, just as there were pre-historical human events. So, history isn’t just the record of human events. It is a very specific thing.

For Hegel, history is the human quest for self-knowledge and self-actualization. There was a time when human beings were not actively pursuing those aims. This was characteristic of prehistorical forms of life, when men were brutish and dumb. And there will be a time when human beings will no longer actively pursue self-knowledge and self-actualization, because we will have already achieved them. That will be post-historical life.

History is the human quest for self-knowledge and self-actualization. When that quest comes to an end, when we know ourselves and become ourselves, then there will be no more history. That’s how history will stop.

Hegel posits that human beings have a fundamental need for self-knowledge. In fact, in the last analysis, for him self-actualization just is self-knowledge. So, human beings are fulfilled by knowing themselves. That’s what it’s all about. That’s what we’re all striving for. That’s what the whole record of history has been pointing to: self-knowledge.

How is the pursuit of self-knowledge connected with history? Isn’t self-knowledge just something we have through introspection? Can’t you just have self-knowledge on a desert island or lying in bed in the morning? Why do we need to do things like build civilizations or cathedrals and fight wars? Why do we need history in order to pursue self-knowledge?

How is the pursuit of self-knowledge connected with history? Isn’t self-knowledge just something we have through introspection? Can’t you just have self-knowledge on a desert island or lying in bed in the morning? Why do we need to do things like build civilizations or cathedrals and fight wars? Why do we need history in order to pursue self-knowledge?

Hegel would agree that we do have a kind of immediate self-awareness, which Rousseau would call the “sentiment of existence.” But that feeling is shared with all the animals, too. Therefore, insofar as we have an immediate feeling of self that really doesn’t constitute knowledge of us as distinctly human creatures. Second, knowledge as such requires more than just immediate feeling. It has to be more articulated, reflective, and, as he puts it, mediated rather than immediate. It has to be on the level of thought rather than the level of feeling. In order to arrive at self-knowledge of our distinctly human characteristics, and to know that in a distinctly human way through reason, through thought, we have to go beyond just feeling. We have to do things.

Now, to know ourselves as physical beings we can look in a mirror. Although we have to recognize the being we see in the mirror as ourselves. Animals don’t seem to be able to recognize their own reflections. But when human beings reach a certain point in our development, we realize, “Aha! That’s us!” And there’s something extraordinary about recognizing ourselves as reflected in something other, something external.

Hegel believes that self-knowledge of our soul, if you will, requires a similar process. We need to find a mirror in which our soul can be reflected, and in which we can recognize our reflection, and thereby come to know ourselves as spiritual beings.

Now, what is the appropriate mirror of the soul? Well, the first and most obvious answer would be another soul, another human being. The way that we come to know ourselves as human beings is by recognizing ourselves in others. The best form of recognition would be to recognize ourselves in the eyes of somebody who is very similar to us, who can really show us who we are. The kind of relationship where that happens is friendship or love. We can know ourselves through people who antagonize us, but the best kind of self-awareness is through love and friendship. The most complete sort of self-awareness is through love and friendship.

But that’s not enough. Love is not enough for Hegel. Friendship is not enough to explain history. If we could know ourselves adequately, if we could satisfy our need for self-knowledge simply through interpersonal relationships, we never would have embarked on this long quest towards civilization, because we could have satisfied that need in the prehistorical family, in the little villages, in thatched huts, in hunter-gatherer bands. We don’t need buildings and technologies and civilizations that extend thousands of miles. We don’t need cathedrals and skyscrapers or any of that just to have interpersonal relationships.

So, the quest for self-knowledge has to be understood more precisely here. We need to know ourselves. To know ourselves as individuals does not require history, so what kind of self-knowledge requires history? Hegel seems to believe that history is required if we are to know ourselves universally, to know ourselves in an abstract sense, and not just as a particular individual—in other words, to know what is man in general. Ultimately, this is the aim of philosophy.

Your best friend or your spouse is not going to be adequate to give you this kind of universal self-knowledge. Another human being isn’t an adequate mirror for that. Only philosophy can show that to you, and so Hegel believes that we have to understand history as arising out of the need for universal self-knowledge.

But of course philosophy wasn’t there at the beginning of history. So, how do we try to begin to satisfy that need for universal self-knowledge?

Hegel’s argument is simple: We have to make a mirror for ourselves. We have this material called nature—rocks and rivers and trees—and we need to remake it. We need to go out there and transform the world, to put the stamp of humanity upon it, to humanize the world, to remake the world in our own image—and to recognize ourselves, to recognize the truth about mankind in general, in our work.

Every culture is basically an ensemble of practices, artifacts, and institutions in which, and by which, human beings embody a particular attempt to understand themselves. Culture is the mirror in which human beings know themselves in a universal way. The record of cultures and their transformation is what we call history. Therefore, history is necessitated as our first step towards universal self-understanding.

There are many cultures and thus many interpretations of our nature. But there is only one truth. Therefore, all cultures can’t be rated equally. Some are truer to man and his nature than others. So it’s possible to rank cultures in a hierarchy in terms of how well or how poorly they reflect the true nature of man. But Hegel is also clear that ultimately, culture as such is an inadequate medium for coming to universal self-understanding. Thus what happens at a certain point in at least some cultures—three, to be exact—is the emergence of philosophy. The Greeks, the Indians, and the Chinese all spontaneously evolved philosophical traditions.

Hegel’s view is that we finally come to universal self-understanding through philosophy—ultimately through Hegel’s philosophy, as it turns out. History is the pursuit of wisdom. Hegel has become wise. He knows the truth about man, and therefore the philosophical quest and the historical quest both came to an end in 1806, when Hegel wrote his book The Phenomenology of Spirit.

Now, this might sound grandiose to you, but really every philosopher worth his salt is grandiose, because they’re searching for the Truth with a capital T. Hegel is just one of the more immodest philosophers, because he claims that not only is he searching for it, he’s actually found it, and therefore he’s not really a philosopher anymore. He’s a wise man. He’s a sage.

What is this big Truth that has brought history to an end? According to Kojève, the truth about man is that we’re all free and equal. That might sound banal, but he says that that’s what human beings have been fighting for and struggling for—sculpting and painting, composing music and writing books for, over thousands of years—in order to discover that we’re all free and equal. Once this discovery has been announced, and once the world has been remade in the image of freedom and equality, history has come to an end.

Kojève claims that history comes to an end with what he calls the universal and homogeneous state. When we recognize that all men are free and all men are equal, the only thing left is to create a form of society that recognizes this freedom and equality. That form of society has to be universal. It can’t be attached to any particular culture, because culture is over, too. History is just a record of cultures, and when history ends, culture is over, too. Culture becomes, in some sense, unnecessary, because it’s really not the best medium for coming to self-understanding. Kojève glimpses a tendency towards the complete homogenization of the world within this universal state. So he calls the end of history the universal homogeneous state, and he thinks this is great. This is wonderful.

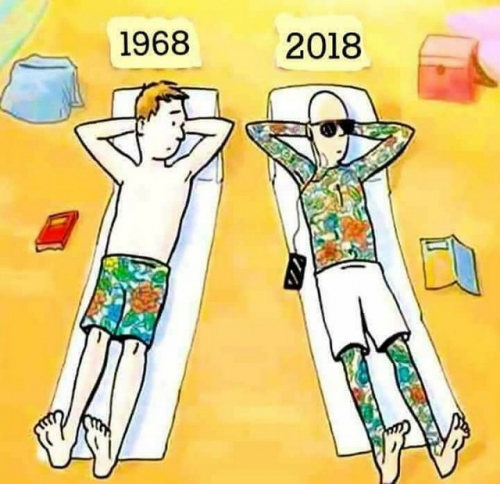

We’re rapidly seeing this all around us. In Bhutan, they’re getting TV today. Tomorrow, they’re going to be wearing little baseball caps—backwards, of course—listening to rap music, and wearing t-shirts with American brand names on them. Eventually it will be more practical to just learn one language: English. As one friend puts it, “language par excellence.” And we’ll all be English speakers; we’ll all be buying the same things; we’ll all be watching the same TV shows. We’ll be one big, happy, peaceful world, and mankind will be entirely satisfied, because we’ll all be free and we’ll all be equal. But we won’t all be philosophers. Only the very smart ones will become philosophers. Because we’re not going to all be equal in that respect. We’ll be politically equal.

That’s the Hegelian story, in a very crude overview. It’s crude, but it’s completely correct and accurate. It’s completely correct and accurate to Hegel’s view, if not to reality; let’s put it that way.

This is Kojève’s description of the end of history: “In the final state, there are naturally no more human beings.” Why? Because man is a historical being, too, and when history comes to an end, what is distinctively human disappears. “The healthy automata are satisfied. They have sports, art, eroticism, and so forth, and the sick ones get locked up.” Or they get Prozac. Or other mood-altering drugs to make them happier. “The philosophers become gods. The tyrant becomes an administrator, a cog in the machine fashioned by automata for automata.”

This is his view of the end of things. Now, if somebody were to step forward and declare, “I have a dream of a world of healthy, well-fed automata, de-humanized robots ruled over by technocrats that think they are gods,” would you be at all inclined to be inspired by that vision of things? It is a very strange way of speaking about something that Kojève at least officially regards as utopia, the form of society that totally satisfies all of mankind.

Here we arrive at the odd problem, because as he becomes more and more enthusiastic about the end of history—at least putatively enthusiastic, apparently enthusiastic—he begins phrasing it in ways that are more and more chilling, unappetizing, and unappealing.

The notes for Kojève’s Hegel seminar were edited and published in 1947 by Queneau as Introduction to the Reading of Hegel. After it was published, it was reprinted in a number of different editions. As the new editions came out, Kojève would add notes to them. About half of the French volume has been translated into English. The good stuff. There’s a famous note in here. Kojève adds a note to the second edition and then adds a note to that note in the third edition. As the notes pile up, the vision of the end of history becomes more and more disturbing and unappealing.

What’s going on here? Surely, Kojève, who was a master of rhetoric, knew the likely effects of his rhetoric. So, why was he praising something in terms designed to produce discomfort and disgust? It’s a very interesting question.

His second thoughts about the end of history were expressed in his later writings as a thesis that man is coming to an end. The end of history is the end of man. Man, properly understood, is being erased. The masses of people at the end of history, he said, will become beasts. And another term for them, he said, are slaves without masters.

He said, “Bourgeois man is a slave without a master. He is a slave spiritually, because there is nothing he is willing to die for.”

The worst possible thing for the bourgeoisie, he says, is a violent death. They’ll do anything to avoid that. The greatest possible thing is comfortable living. They’ll betray virtually anything for that. “Do it to Julia!” He says that the end of history is a society where the vast majority of human beings are slaves without masters. They’re officially free, but spiritually speaking, they are slavish. They have no ideals. There’s nothing they’re willing to die for. Nothing is more important than just being comfortable and secure.

The small minority who will rule everything will at least understand everything. They are the philosophers. And they too are dehumanized. Not by becoming beasts, but by becoming gods.

What’s left out are just men, and by “man” Kojève means people who have what Plato called spiritedness. And what is spiritedness? Well, part of spiritedness for Plato is the capacity to respond passionately to ideals. In the most primitive sense, spiritedness is just a kind of touchiness about points of honor. A desire to be treated with respect. But the same kind of attachments to one’s ideal vision of one’s self that used to lead us to fight duels to the death over matters of honor can also be attached to higher things like countries and causes, and so forth. It can even be attached to a love of the good itself.

Kojève thinks that the end of history will mark the elimination of the spirited part of man’s soul. Once we know the truth about mankind—that we are all free and equal—there will be nothing to fight over and no propensity to fight, anyway. The capacity to get angry over points of honor or ideology will simply disappear. This is what he means by the end of man.

Again, it’s not a very appealing picture. Yet it’s a picture that’s increasingly true.

The philosophers, as I said, are increasingly dehumanized as well. They become gods, which means that they are de-spirited creatures as well—effete, cosmopolitan, rootless, and so forth. They jet from one end of the globe to another. They interpret things. They give little papers at conferences. They graze at the buffets and crowd around the open bars. And they experience nothing greater than themselves. They look down on the cultures of the past with detachment, but they buy their artifacts and playfully display them in an eclectic jumble on their mantlepieces.

At the very time Kojève was painting this bleak picture of the end of man, he maintained it was his dream—indeed, that it’s all of our dreams. This is what history is aiming towards, and we’ll all be completely satisfied by it. You’ll love it! Believe me! You’re already loving it! But why in the world did he say things that undermine his overall thesis?

The interpretation I want to give is this: Kojève became very much influenced by Nietzsche, and Nietzsche is really the great 19th-century antipode of Hegel. If you want to find two thinkers who are most fundamentally opposed in philosophy of history and culture, Nietzsche and Hegel are the most opposite you can find. The influence of Nietzsche, I think, was primarily mediated through the influence of Georges Bataille, Kojève’s student, peer, and friend. Bataille was something of a Nietzschean, and I think that as their friendship progressed and as Kojève thought more about things, he came to think that Bataille was fundamentally correct that there was something true about Nietzsche’s view of history.

So, what is Nietzsche’s view of history? Hegel has a linear view of history. History proceeds in a straight line from a beginning to an end. The progress of history arises from a single fundamental need, which is the human need for self-knowledge. Once we achieve that goal, history ends, and that’s it. It’s paradise.

Nietzsche, by contrast, has a cyclical view of history, and he believes that there are two fundamental principles that make the historical world go around. One is the need for self-knowledge, but the other is what I would like to call “the need for vitality,” the need to feel alive and express that feeling.

In Nietzsche’s view, history begins with a kind of vital upsurge, which is leading towards self-knowledge. History begins with a kind of barbarous vitality. As culture progresses, however, and become more refined, our reflectiveness and refinement come to interfere and undermine the sources of cultural vitality.

Culture, at the beginning, is something that’s necessary for us to be healthy, but as it progresses and becomes more refined, it becomes a source of sickness, decline, and decay. So, at this point we have a decadent culture where people are very reflective, dispassionate, corrupt, and lacking in virtue. And what eventually happens when decadence grows widespread? Everything collapses, everything falls apart. You can’t have a functioning society full of rotten people. The few survivors who are left return to barbarism. All the cobwebs of fine-spun theories are swept away, human vitality returns, and history begins again.

Now, in the portrait that Kojève paints at the end of history, you really can see this Nietzschean perspective at work. The “last man,” which was Nietzsche’s term for decadent and dehumanized men, is the true outcome of Hegel’s drive for universal freedom and equality. But the last man can’t sustain civilization, so history must start all over again. The last man, in Nietzsche’s terms, is precisely what Kojève is describing as slaves without masters and masters without slaves, the dehumanized beasts and gods that exist at the end of history. Both beasts and gods lack a distinctively human vitality to give rise to culture and values.

I want to argue that Kojève’s ambivalence about the end of history really arises out of the fact that he simultaneously affirms two completely contradictory theories of history. One is Hegel’s and the other is Nietzsche’s. Kojève was not an idiot. In fact, people who I respect enormously said that he was the smartest man they ever knew. He was extraordinarily intelligent. The best-functioning and best-stocked brain of the century, according to one person who knew him. Thus he was not so stupid as to overlook the fact that he was affirming two diametrically opposed views. So why was he doing this?

I’ll answer this question, but I want to raise another one first. Why did Kojève play both sides of the Cold War? Clearly he had to see that there was something a little immoral, or there was at least an appearance of impropriety, in passing secrets to the KGB. Why did he do this? Why was he affirming opposed theories of history, and why was he playing both sides against another in the Cold War? I think that the answers to both questions are related.

Let me answer the first question this way. I follow Plato, and Plato recommends that in order to understand a philosopher’s teachings, you don’t just look at his words, you also look at his deeds, and then you put the words and the deeds together and look at the total effect. The total effect of a philosopher’s teaching is what he is really getting at. Not necessarily what he says or what he does, but the total effect of the two together on the actions of the people who read it, understand it, and follow it. These guys are smart. They know the likely effect of their writings. So, if you want to understand the meaning of a philosopher’s teachings, look at the effect, not what he says in isolation, not what he does in isolation, but the effect of what he says and what he does taken together.

What’s the effect of Kojève’s teaching about modernity? The fact is that every single person who took Kojève seriously as a teacher—Left or Right, far Left or far Right—ended up rejecting the end of history, the vision of modernity that Kojève was loudly trumpeting as his dream—and everybody’s dream—come true. He was not so stupid as to be caught unaware by this. I refuse to believe that.

I think that the meaning of Kojève’s teachings is precisely this: Kojève presented Hegel’s view of history in such dire and dystopian terms to induce people to revolt against it. He was presenting the end of history in a way that was designed to make people want to get history started all over again. If history can start all over again, that means that, fundamentally, we affirm the Nietzschean cyclical view rather than the Hegelian linear view. So, I think that ultimately Kojève was a kind of Nietzschean who was deeply disturbed by modernity and wanted to bring it to an end.

How is this connected with his political actions? Well, some people may say, “Look, the reason why he was on both sides of the Cold War is because he believed in the convergence thesis and didn’t think there was any difference between the two.”

But that really doesn’t explain it, for this reason: If he didn’t believe that either side was fundamentally different from the other, then why wouldn’t he have worked as hard as possible on one side to ensure its ultimate triumph? It would be a matter of indifference as to which side he supported. But why was he helping both sides? That can’t be explained, because by helping both sides in the Cold War, you would think that that was actually helping to perpetuate the Cold War rather than bring it to an end. Why would he want us to keep fighting?

But this makes sense if Kojève is fundamentally a Nietzschean who wanted to forestall as long as possible the end of history that Fukuyama—his somewhat unsubtle and popularizing student—was so happy about.

I think that perhaps his very dangerous political game had a similar aim as his philosophical game, namely not to bring history to an end but to keep it going, keep the conflict going. Why? Because as a Nietzschean, he believed that, ultimately, conflict about values is the thing that makes us most human. The capacity to aspire to and ultimately die for ideals, is the most glorious and distinctly human characteristic we have. And the Cold War was one, long conflict over fundamental ideas, and it would be perfectly consistent with the Nietzschean view to want to keep that conflict going, especially if he foresaw that the outcome of one side winning would be McWorld. If that was the case, then it makes perfect sense that he would be playing both sides. He didn’t want either one to win. The longer Kojève could forestall the end of history, the better. The better for all of us.

And now that history has ended, we need to go to Plan B, which is to start history all over again. And we don’t need to wait for the barbarians. They are already here.

Carl Jung

Carl Jung Alexis Carrel

Alexis Carrel Konrad Lorenz

Konrad Lorenz

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

L’ouvrage est essentiel car depuis le délire a débordé des campus et gagné la société occidentale toute entière. En même temps qu’elle déboulonne les statues, remet en cause le sexe de Dieu et diabolise notre héritage littéraire et culturel, cette société intégriste-sociétale donc menace le monde libre russe, chinois ou musulman (je ne pense pas à Riyad…) qui contrevient à son alacrité intellectuelle. Produit d’un nihilisme néo-nietzschéen, de l’égalitarisme démocratique et aussi de l’ennui des routines intellos (Bloom explique qu’on voulait « débloquer des préjugés, « trouver du nouveau »), la pensée politiquement correcte va tout dévaster comme un feu de forêt de Stockholm à Barcelone et de Londres à Berlin. On va dissoudre les nations et la famille (ou ce qu’il en reste), réduire le monde en cendres au nom du politiquement correct avant d’accueillir dans les larmes un bon milliard de réfugiés. Bloom pointe notre lâcheté dans tout ce processus, celle des responsables et l’indifférence de la masse comme toujours.

L’ouvrage est essentiel car depuis le délire a débordé des campus et gagné la société occidentale toute entière. En même temps qu’elle déboulonne les statues, remet en cause le sexe de Dieu et diabolise notre héritage littéraire et culturel, cette société intégriste-sociétale donc menace le monde libre russe, chinois ou musulman (je ne pense pas à Riyad…) qui contrevient à son alacrité intellectuelle. Produit d’un nihilisme néo-nietzschéen, de l’égalitarisme démocratique et aussi de l’ennui des routines intellos (Bloom explique qu’on voulait « débloquer des préjugés, « trouver du nouveau »), la pensée politiquement correcte va tout dévaster comme un feu de forêt de Stockholm à Barcelone et de Londres à Berlin. On va dissoudre les nations et la famille (ou ce qu’il en reste), réduire le monde en cendres au nom du politiquement correct avant d’accueillir dans les larmes un bon milliard de réfugiés. Bloom pointe notre lâcheté dans tout ce processus, celle des responsables et l’indifférence de la masse comme toujours. « Les aventuriers sexuels comme Margaret Mead et d'autres qui ont trouvé l'Amérique trop étroite nous ont dit que non seulement nous devons connaître d'autres cultures et apprendre à les respecter, mais nous pourrions aussi en tirer profit. Nous pourrions suivre leur exemple et nous détendre, nous libérer de l'idée que nos tabous ne sont rien d'autre que des contraintes sociales. »

« Les aventuriers sexuels comme Margaret Mead et d'autres qui ont trouvé l'Amérique trop étroite nous ont dit que non seulement nous devons connaître d'autres cultures et apprendre à les respecter, mais nous pourrions aussi en tirer profit. Nous pourrions suivre leur exemple et nous détendre, nous libérer de l'idée que nos tabous ne sont rien d'autre que des contraintes sociales. » Bloom enfin a compris l’usage ad nauseam qu’on fera de la référence hitlérienne : tout est décrété raciste, fasciste, nazi, sexiste dans les campus US dès 1960, secrétaires du rectorat y compris ! Mais lui reprenant Marx ajoute que ce qui passe en 1960 n’est ni plus ni moins une répétition comique du modèle tragique de 1933. Les juristes nazis comme Carl Schmitt décrétaient juive la science qui ne leur convenait pas comme aujourd’hui on la décrète blanche ou sexiste.

Bloom enfin a compris l’usage ad nauseam qu’on fera de la référence hitlérienne : tout est décrété raciste, fasciste, nazi, sexiste dans les campus US dès 1960, secrétaires du rectorat y compris ! Mais lui reprenant Marx ajoute que ce qui passe en 1960 n’est ni plus ni moins une répétition comique du modèle tragique de 1933. Les juristes nazis comme Carl Schmitt décrétaient juive la science qui ne leur convenait pas comme aujourd’hui on la décrète blanche ou sexiste.

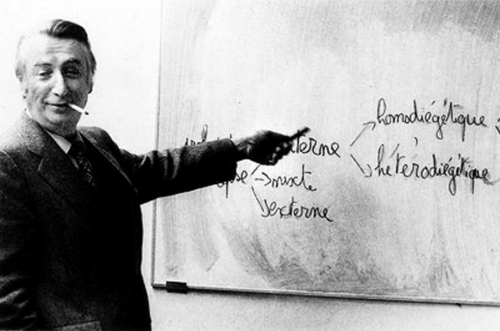

A l’époque la SF nous rassure. Les martiens ne peuvent être que comme nous. Le caustique auteur de S/Z Seraphita ajoute :

A l’époque la SF nous rassure. Les martiens ne peuvent être que comme nous. Le caustique auteur de S/Z Seraphita ajoute :

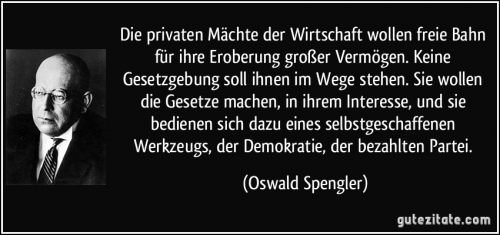

On a parlé de l’écologie. Spengler écrit sur cette fatigue (plus que crise) du monde moderne :

On a parlé de l’écologie. Spengler écrit sur cette fatigue (plus que crise) du monde moderne :

Que dit le maître à penser de Georges Soros ? En substance, qu’une société ouverte, au contraire d’une société fermée, distingue ce qui relève du droit de ce qui relève de la culture. Le philosophe explique que la société ne doit plus être soudée par des valeurs partagées mais par des lois qui respectent le droit naturel et n’entravent pas le pluralisme des idées ou des croyances. Une société ouverte fondée sur des lois acceptables par tous les hommes peut, et même doit selon Popper, être multiculturelle et multiraciale. En résumé, Popper, inspiré par le républicanisme « français », nous explique que les cultures doivent perdre leur caractère sociétal sous l’effet de lois culturicides. La loi émanant de l’identité doit s’effacer devant une loi abstraite émanant de l’universalité. Le philosophe propose un

Que dit le maître à penser de Georges Soros ? En substance, qu’une société ouverte, au contraire d’une société fermée, distingue ce qui relève du droit de ce qui relève de la culture. Le philosophe explique que la société ne doit plus être soudée par des valeurs partagées mais par des lois qui respectent le droit naturel et n’entravent pas le pluralisme des idées ou des croyances. Une société ouverte fondée sur des lois acceptables par tous les hommes peut, et même doit selon Popper, être multiculturelle et multiraciale. En résumé, Popper, inspiré par le républicanisme « français », nous explique que les cultures doivent perdre leur caractère sociétal sous l’effet de lois culturicides. La loi émanant de l’identité doit s’effacer devant une loi abstraite émanant de l’universalité. Le philosophe propose un

Vous avez ainsi émis des réserves sur les expérimentations du LHC, le grand collisionneur du Cern, car vous redoutez la création d'un " trou noir " (lire S. et A. n° 735, mai 2008). Vous croyez vraiment à un pareil danger ?

Vous avez ainsi émis des réserves sur les expérimentations du LHC, le grand collisionneur du Cern, car vous redoutez la création d'un " trou noir " (lire S. et A. n° 735, mai 2008). Vous croyez vraiment à un pareil danger ?

C’est « Paris et le désert français » cent ans avant Jean-François Gravier ; mais pour être honnête Rousseau avait déjà méprisé l’usage inconvenant de l’hyper-capitale Paris pour la France.

C’est « Paris et le désert français » cent ans avant Jean-François Gravier ; mais pour être honnête Rousseau avait déjà méprisé l’usage inconvenant de l’hyper-capitale Paris pour la France.

Now, who was Alexandre Kojève? He was born in 1902 as Aleksandr Vladimirovič Koževnikov. He was born in Moscow to a very wealthy family. After the Russian Revolution, the family fell on hard times, and he was eventually reduced to selling black-market soap on the street. He was arrested for this and narrowly escaped execution. His experiences with the GPU led to a rather unusual outcome. He converted to Marxism and maintained that he was an ardent Stalinist to the very end of his life.

Now, who was Alexandre Kojève? He was born in 1902 as Aleksandr Vladimirovič Koževnikov. He was born in Moscow to a very wealthy family. After the Russian Revolution, the family fell on hard times, and he was eventually reduced to selling black-market soap on the street. He was arrested for this and narrowly escaped execution. His experiences with the GPU led to a rather unusual outcome. He converted to Marxism and maintained that he was an ardent Stalinist to the very end of his life. He was also the first person to announce what is sometimes called the convergence thesis. Zbigniew Brzezinski, National Security Adviser to Jimmy Carter, is often credited with this view. The convergence thesis is basically that as the Cold War wore on, the pressures of fighting it would cause both sides to gradually converge and become indistinguishable from one another.

He was also the first person to announce what is sometimes called the convergence thesis. Zbigniew Brzezinski, National Security Adviser to Jimmy Carter, is often credited with this view. The convergence thesis is basically that as the Cold War wore on, the pressures of fighting it would cause both sides to gradually converge and become indistinguishable from one another. Another contemporary thinker who’s really quite trendy today is the Slovene writer Slavoj Žižek. I hope there are no Slovenians in the audience who will knock my pronunciation. Žižek has written quite a number of books with titles like Everything You Always Wanted to Know About Lacan . . . But Were Afraid to Ask Hitchcock, and he’s enormously influenced by Kojève’s view of Hegel, and also Lacan’s reading of Kojève’s Hegel.

Another contemporary thinker who’s really quite trendy today is the Slovene writer Slavoj Žižek. I hope there are no Slovenians in the audience who will knock my pronunciation. Žižek has written quite a number of books with titles like Everything You Always Wanted to Know About Lacan . . . But Were Afraid to Ask Hitchcock, and he’s enormously influenced by Kojève’s view of Hegel, and also Lacan’s reading of Kojève’s Hegel. How is the pursuit of self-knowledge connected with history? Isn’t self-knowledge just something we have through introspection? Can’t you just have self-knowledge on a desert island or lying in bed in the morning? Why do we need to do things like build civilizations or cathedrals and fight wars? Why do we need history in order to pursue self-knowledge?

How is the pursuit of self-knowledge connected with history? Isn’t self-knowledge just something we have through introspection? Can’t you just have self-knowledge on a desert island or lying in bed in the morning? Why do we need to do things like build civilizations or cathedrals and fight wars? Why do we need history in order to pursue self-knowledge?

Les auteurs ne cachent pas, du reste, les réserves que peuvent leur inspirer ce plan de travail, qui est celui de l’éducation nationale, mais ils ont choisi d’en montrer les éventuelles limites de l’intérieur. Le déploiement de ce modèle classique d’exposition de la philosophie a le mérite de susciter des échos chez tous les lecteurs, avancés ou moins avancés, de thèmes philosophiques. Il montre aussi qu’il est possible d’entrer dans la philosophie par différentes portes. C’est pourquoi Alain Renaut précise à juste titre qu’il n’est aucunement indispensable de lire ce livre dans l’ordre des parties et des chapitres. Nous ne sommes donc ni face à un manuel scolaire/universitaire à proprement parler, ni face à un anti-manuel, ce qui serait bien prétentieux, et une vaine coquetterie.

Les auteurs ne cachent pas, du reste, les réserves que peuvent leur inspirer ce plan de travail, qui est celui de l’éducation nationale, mais ils ont choisi d’en montrer les éventuelles limites de l’intérieur. Le déploiement de ce modèle classique d’exposition de la philosophie a le mérite de susciter des échos chez tous les lecteurs, avancés ou moins avancés, de thèmes philosophiques. Il montre aussi qu’il est possible d’entrer dans la philosophie par différentes portes. C’est pourquoi Alain Renaut précise à juste titre qu’il n’est aucunement indispensable de lire ce livre dans l’ordre des parties et des chapitres. Nous ne sommes donc ni face à un manuel scolaire/universitaire à proprement parler, ni face à un anti-manuel, ce qui serait bien prétentieux, et une vaine coquetterie.

Het probleem van zo’n essaybundel, waarin we naast Cliteur namen terugvinden als

Het probleem van zo’n essaybundel, waarin we naast Cliteur namen terugvinden als  Sid Lukkassen komt tot een andere conclusie: de culturele hegemonie van links moeten we laten voor wat ze is. We moeten compleet nieuwe, eigen media, netwerken en instellingen oprichten die niet ‘besmet’ zijn door het virus en voor echte vrijheid gaan: ‘De enige weg voorwaarts is dus het scheppen van een eigen thuishaven, een eigen Nieuwe Zuil met bijbehorende instituties en cultuurdragende organen. Die alternatieve media zijn volop aan het doorschieten, Doorbraak is er een van.

Sid Lukkassen komt tot een andere conclusie: de culturele hegemonie van links moeten we laten voor wat ze is. We moeten compleet nieuwe, eigen media, netwerken en instellingen oprichten die niet ‘besmet’ zijn door het virus en voor echte vrijheid gaan: ‘De enige weg voorwaarts is dus het scheppen van een eigen thuishaven, een eigen Nieuwe Zuil met bijbehorende instituties en cultuurdragende organen. Die alternatieve media zijn volop aan het doorschieten, Doorbraak is er een van.

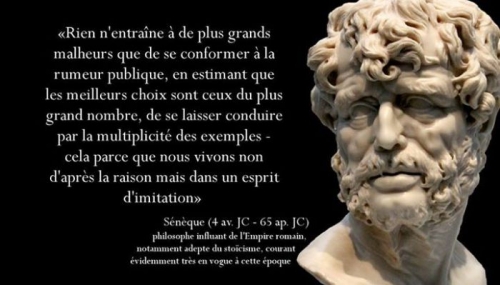

« On était exempt de ces fléaux quand on ne s’était pas encore laissé fondre aux délices, quand on n’avait de maître et de serviteur que soi. On s’endurcissait le corps à la peine et au vrai travail ; on le fatiguait à la course, à la chasse, aux exercices du labour. On trouvait au retour une nourriture que la faim toute seule savait rendre agréable. Aussi n’était-il pas besoin d’un si grand attirail de médecins, de fers, de boîtes à remèdes. Toute indisposition était simple comme sa cause : la multiplicité des mets a multiplié les maladies. Pour passer par un seul gosier, vois que de substances combinées par le luxe, dévastateur de la terre et de l’onde ! »

« On était exempt de ces fléaux quand on ne s’était pas encore laissé fondre aux délices, quand on n’avait de maître et de serviteur que soi. On s’endurcissait le corps à la peine et au vrai travail ; on le fatiguait à la course, à la chasse, aux exercices du labour. On trouvait au retour une nourriture que la faim toute seule savait rendre agréable. Aussi n’était-il pas besoin d’un si grand attirail de médecins, de fers, de boîtes à remèdes. Toute indisposition était simple comme sa cause : la multiplicité des mets a multiplié les maladies. Pour passer par un seul gosier, vois que de substances combinées par le luxe, dévastateur de la terre et de l’onde ! » Et d’évoquer la pédophilie festive de nos romains diners :

Et d’évoquer la pédophilie festive de nos romains diners :

It was most likely in the context of this scientific tradition and its enemies that Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, generally recognized as Germany’s greatest poet (or one of them, at any rate), later authored attacks on Newton’s ideas, such as Theory of Colors. Goethe, an early pioneer in biology and the life sciences, loathed the notion that there is anything universally axiomatic about the mathematical sciences. Goethe had one major predecessor in this, the Anglo-Irish philosopher and Anglican bishop George Berkeley. Like Berkeley, Goethe argued that Newtonian abstractions contradict empirical understandings. Both Berkeley and Goethe, though for different reasons, took issue with the common (or at least, commonly Anglo-Saxon) wisdom that “mathematics is a universal language.”

It was most likely in the context of this scientific tradition and its enemies that Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, generally recognized as Germany’s greatest poet (or one of them, at any rate), later authored attacks on Newton’s ideas, such as Theory of Colors. Goethe, an early pioneer in biology and the life sciences, loathed the notion that there is anything universally axiomatic about the mathematical sciences. Goethe had one major predecessor in this, the Anglo-Irish philosopher and Anglican bishop George Berkeley. Like Berkeley, Goethe argued that Newtonian abstractions contradict empirical understandings. Both Berkeley and Goethe, though for different reasons, took issue with the common (or at least, commonly Anglo-Saxon) wisdom that “mathematics is a universal language.”

Cuvier, however, does not belong to the German transcendentalist tradition, so Spengler mentions him only peripherally. On the other hand, in the third chapter of the second volume of The Decline of the West, Spengler uses a word that Charles Francis Atkinson translates as “admitted” to describe how Cuvier propounded the theory of catastrophism. Clearly, Spengler shows himself to be more sympathetic to Cuvier than to what he calls the “English thought” of Darwin.

Cuvier, however, does not belong to the German transcendentalist tradition, so Spengler mentions him only peripherally. On the other hand, in the third chapter of the second volume of The Decline of the West, Spengler uses a word that Charles Francis Atkinson translates as “admitted” to describe how Cuvier propounded the theory of catastrophism. Clearly, Spengler shows himself to be more sympathetic to Cuvier than to what he calls the “English thought” of Darwin.