Oswald Spengler’s writings on the subject of the philosophy of science are very controversial, not only among his detractors but even for his admirers. What is little understood is that his views on these matters did not exist in a vacuum. Rather, Spengler’s arguments on the sciences articulate a long German tradition of rejecting English science, a tradition that originated in the eighteenth century.

Luke Hodgkin notes:

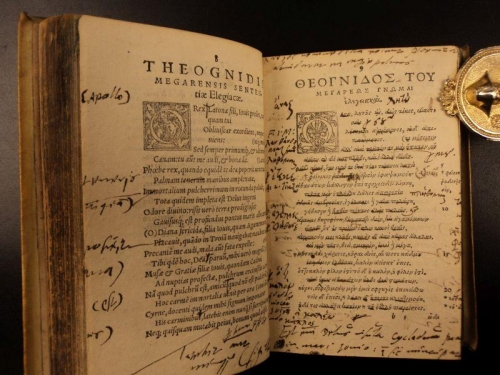

It is today regarded as a matter of historical fact that Isaac Newton and Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz both independently conceived and developed the system of mathematical algorithms known collectively by the name of calculus. But this has not always been the prevalent point of view. During the eighteenth century, and much of the nineteenth, Leibniz was viewed by British mathematicians as a devious plagiarist who had not just stolen crucial ideas from Newton, but had also tried to claim the credit for the invention of the subject itself.[1] [2]

This wrongheaded view stems from Newton’s own catty libel of Leibniz on these matters. During this time, the beginning of the eighteenth century, Leibniz’s native Prussia had not yet become a serious power through the wars of Frederick the Great. Leibniz, together with Frederick the Great’s grandfather, founded the Royal Prussian Academy of Sciences. Newton’s slanderous account of Leibniz’s achievements would never be forgiven by the Germans, to whom Newton remained a bête noire as long as Germany remained a proud nation.

In the context of inquiring into the matter of how such a pessimist as Spengler could admire so notorious an optimist as Leibniz, two foreign members of the Prussian Academy of Sciences merit attention. The thought of French scientist and philosopher Pierre Louis Moreau de Maupertuis, an exponent and defender of Leibnizian ideas, was in many ways a precursor to modern biology. Maupertuis wrote under the patronage of Frederick the Great, about a generation after Leibniz. Compared to other eighteenth-century philosophies, Maupertuis’ worldview, like modern biology and unlike most Enlightenment thought, presents nature as rather “red in tooth and claw.”

An earlier foreign member of the Prussian Academy of Sciences, a contemporary and correspondent of Leibniz, Moldavian Prince (and eccentric pretender to descent from Tamerlane) Dimitrie Cantemir, left two cultural legacies to Western history. Initially an Ottoman vassal, he gave traditional Turkish music its first system of notation, ushering in the classical era of Turkish music that would later influence Mozart. Later – after he had turned against the Ottoman Porte in an alliance with Petrine Russia, but was driven out of power and into exile due to his abysmal battlefield leadership – he wrote much about history. Most impactful in the West was a two-volume book that would be translated into English in 1734 as The History of the Growth and Decay of the Othman Empire. Voltaire and Gibbon later read Cantemir’s work, as did Victor Hugo.[2] [3]

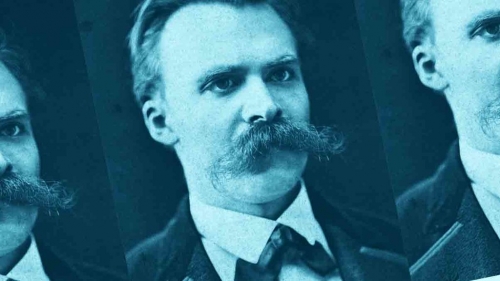

Notes one biographer, “Cantemir’s philosophy of history is empiric and mechanistic. The destiny in history of empires is viewed . . . through cycles similar to the natural stages of birth, growth, decline, and death.”[3] [4] Long before Nietzsche popularized the argument, Cantemir proposed that high cultures are initially founded by barbarians, and also that a civilization’s level of high culture has nothing to do with its political success.[4] [5] Thus was the Leibnizian intellectual legacy mixed with pessimism even in Leibniz’s own lifetime.

It was most likely in the context of this scientific tradition and its enemies that Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, generally recognized as Germany’s greatest poet (or one of them, at any rate), later authored attacks on Newton’s ideas, such as Theory of Colors. Goethe, an early pioneer in biology and the life sciences, loathed the notion that there is anything universally axiomatic about the mathematical sciences. Goethe had one major predecessor in this, the Anglo-Irish philosopher and Anglican bishop George Berkeley. Like Berkeley, Goethe argued that Newtonian abstractions contradict empirical understandings. Both Berkeley and Goethe, though for different reasons, took issue with the common (or at least, commonly Anglo-Saxon) wisdom that “mathematics is a universal language.”

It was most likely in the context of this scientific tradition and its enemies that Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, generally recognized as Germany’s greatest poet (or one of them, at any rate), later authored attacks on Newton’s ideas, such as Theory of Colors. Goethe, an early pioneer in biology and the life sciences, loathed the notion that there is anything universally axiomatic about the mathematical sciences. Goethe had one major predecessor in this, the Anglo-Irish philosopher and Anglican bishop George Berkeley. Like Berkeley, Goethe argued that Newtonian abstractions contradict empirical understandings. Both Berkeley and Goethe, though for different reasons, took issue with the common (or at least, commonly Anglo-Saxon) wisdom that “mathematics is a universal language.”

By the early modern age of European history, when Goethe’s Faust takes place, cabalistic doctrines, notes Carl Schmitt, “became known outside Jewry, as can be gathered from Luther’s Table Talks, Bodin’s Demonomanie, Reland’s Analects, and Eisenmenger’s Entdecktes Judenthum.”[5] [6] This phenomenon can be traced to the indispensable influence of the very inventors of cabalism, collectively speaking, on the West’s transition from feudalism to modern capitalism since the Age of Discovery, and in some cases even earlier. In 1911’s The Jews and Modern Capitalism, Werner Sombart points out that “Venice was a city of Jews” as early as 1152.

Cabalism deeply permeates the worldviews of many influential secret societies of Western history since medieval times, and certainly continuing with the official establishment of Freemasonry in 1717. Although the details will never be entirely clear, it is known that Goethe was involved with the Bavarian Illuminati in his youth. He seems to have experienced conservative disillusionment with it later in life. It is possible that the posthumous publication of Faust: The Second Part of the Tragedy was due at least in part to the book’s ambivalently revealing too much about the esoterica of Goethe’s former occult activities.

What is clear is that he was directly interested in cabalistic concepts. Karin Schutjer persuasively argues that “Goethe had ample opportunity to learn about Jewish Kabbalah – particularly that of the sixteenth-century rabbi Isaac Luria – and good reason to take it seriously . . . Goethe’s interest in Kabbalah might have been further sparked by a prominent argument concerning its philosophical reception: the claim that Kabbalistic ideas underlie Spinoza’s philosophy.”[6] [7]

At one point in the second part of Faust, Goethe shows an interest in monetary issues related to usury or empty currency, as Schopenhauer after him would.[7] [8] This is fitting for a story that takes place in early modern Europe and concerns an alchemist. Some early modern alchemists were known as counterfeiters and would have most likely had contact with Jewish moneylenders. Insofar as his scientific philosophy had a social, and not just an intellectual, significance, this desire on Goethe’s part for economic concreteness was perhaps what led him to reject and combat one key cabalistic doctrine: numerology.

Numerology is the belief that numbers are divine and have prophetic power over the physical world. Goethe held the virtually opposite view of numbers and mathematical systems, proposing that “strict separation must be maintained between the physical sciences and mathematics.” According to Goethe, it is an “important task” to “banish mathematical-philosophical theories from those areas of physical science where they impede rather than advance knowledge,” and to discard the “false notion that a phrase of a mathematical formula can ever take the place of, or set aside, a phenomenon.” To Goethe, mathematics “runs into constant danger when it gets into the terrain of sense-experience.”[8] [9]

In his well-researched 1927 book on Freemasonry, General Erich Ludendorff remarks, “One must study the cabala in order to understand and evaluate the superstitious Jew correctly. He then is no longer a threatening opponent.”[9] [10] In his proceeding discussion of the subject, Ludendorff focuses exclusively on the numerological superstitions in cabalism. Such beliefs are affirmed by a Jewish cabalistic source, which informs us that “Sefirot” is the Hebrew word for numbers, which represent “a Tree of Divine Lights.”[10] [11]

Everything about Goethe’s rejection of scientific materialism can be seen as a rebellion against numerology in the sciences – and certainly, the modern mathematical sciences stand on the shoulders of numerology, as modern chemistry does on alchemy. Schmitt once mentioned the “mysterious Rosicrucian sensibility of Descartes,” a reference to the mysterious cabalistic initiatory movement that dominated the scientific philosophies of the seventeenth century.[11] [12] In this Descartes was hardly alone; the entire epoch of mostly French and English mathematicians in the early modern centuries, which ushered in the modern infinitesimal mathematical systems, was infused with cabalism. Even if it were possible to ignore the growing Jewish intellectual and economic influence on that age, one would still be left with the metaphysical affinities between numerology and even the most scientifically accomplished worldview that takes literally the assumption that numbers are eternal principles.

According to early National Socialist economist Gottfried Feder, “When the Babylonians overcame the Assyrians, the Romans the Carthaginians, the Germans the Romans, there was no continuance of interest slavery; there were no international world powers . . . Only the modern age with its continuity of possession and its international law allowed loan capitals to rise immeasurably.”[12] [13] Writing in 1919, Feder argues with the help of a graph that that “loan-interest capital . . . rises far above human conception and strives for infinity . . . The curve of industrial capital on the other hand remains within the finite!”[13] [14] Goethe may have similarly drawn connections between the kind of economic parasitism satirized in the second part of Faust and what he, like Berkeley, saw as the superstitious modern art of measuring the immeasurable.

The fusion of science with numerology, it should be noted, is actually not of Hebrew or otherwise pre-Indo-European origin. It originates from pre-Socratic Greek philosophy’s debt, particularly that of the Pythagoreans, to the Indo-Iranian world, chiefly Thrace.[14] [15] (Possibly of note in this regard is that Schopenhauer admired the Thracians for their arch-pessimistic ethos, as though this mindset were the polar opposite of the world-affirming Jewish worldview he loathed.)[15] [16] In any case, Goethe recognized it as a powerful weapon. That he studied numerology has been established by scholars.[16] [17]

A generation before Goethe, Immanuel Kant had propounded the idea that the laws of polarity – the laws of attraction and repulsion – precede the Newtonian laws of matter and motion in every way. This argument would influence Goethe’s friend Friedrich Wilhelm von Schelling, another innovator in the life sciences as well as part of the literary and philosophical movement known as Romanticism. By the time Goethe propounded his anti-Newtonian theories and led a philosophical milieu, he had an entire German tradition of such theories to work from.

Goethe’s work was influential in Victorian Britain. Most notably, at least in terms of the scientific history of that era, Darwin would cite Goethe as a botanist in On the Origin of the Species. Darwin’s philosophy of science, to the extent that he had one, was largely built on that of Goethe and the age of what came to be known as Naturphilosophie. Historian of science Robert J. Richards has found that “Darwin was indebted to the Romantics in general and Goethe in particular.”[17] [18] Darwin had been introduced to the German accomplishments in biology, and the German ideas about philosophy of science, mainly through the work of Alexander von Humboldt.[18] [19]

Why has this influence been forgotten? “In the decade after 1918,” explains Nicholas Boyle, “when hundreds of British families of German origin were forcibly repatriated, and those who remained anglicized their names, British intellectual life was ethnically cleansed and the debt of Victorian culture to Germany was erased from memory, or ridiculed.”[19] [20] To some extent, this process had already started since the outbreak of the First World War.

This intellectual ethnic cleansing would not go unreciprocated. In 1915’s Händler und Helden (Merchants and Heroes), German economist and sociologist Werner Sombart attacked the “mercantile” English scientific tradition. Here, Sombart is particularly critical of what he calls the “department-store ethics” of Herbert Spencer, but in general Sombart calls for most English ideas – including English science – to be purged from German national life. In his writings on the philosophy of science, Spengler would answer this call.

Spengler heavily drew on the ideas of Goethe, and evidently also on the views of a pre-Darwinian French Lutheran paleontologist of German origin, Georges Cuvier. For instance, Spengler’s assault on universalism in the physical sciences mostly comes from Goethe, but his rationale for rejecting Darwinian evolution appears to come from Cuvier. The idea that life-forms are immutable, and simply die out, only to be superseded by unrelated new ones – a persistent theme in Spengler – comes more from Cuvier than Goethe.

Cuvier, however, does not belong to the German transcendentalist tradition, so Spengler mentions him only peripherally. On the other hand, in the third chapter of the second volume of The Decline of the West, Spengler uses a word that Charles Francis Atkinson translates as “admitted” to describe how Cuvier propounded the theory of catastrophism. Clearly, Spengler shows himself to be more sympathetic to Cuvier than to what he calls the “English thought” of Darwin.[20] [21]

Cuvier, however, does not belong to the German transcendentalist tradition, so Spengler mentions him only peripherally. On the other hand, in the third chapter of the second volume of The Decline of the West, Spengler uses a word that Charles Francis Atkinson translates as “admitted” to describe how Cuvier propounded the theory of catastrophism. Clearly, Spengler shows himself to be more sympathetic to Cuvier than to what he calls the “English thought” of Darwin.[20] [21]

Several asides about Cuvier are in order. First of all, this criminally underrated thinker is by no means outmoded, at least not in every way. Modern geology operates on a more-Cuvieran-than-Darwinian plane.[21] [22] Secondly, it is worth noting that Ernst Jünger once astutely observed that Cuvier is more useful to modern military science than Darwin.[22] [23] It may also be of interest that the Cuvieran system is even further removed from Lamarckism – and its view of heredity, as a consequence, more thoroughly racialist – than the Darwinian system.[23] [24]

Another scientist of German origin who may have influenced Spengler is the Catholic monk Gregor Mendel, the discoverer of what is now known as genetics. One biography notes:

Though Mendel agreed with Darwin in many respects, he disagreed about the underlying rationale of evolution. Darwin, like most of his contemporaries, saw evolution as a linear process, one that always led to some sort of better product. He did not define “better” in a religious way – to him, a more evolved animal was no closer to God than a less evolved one, an ape no morally better than a squirrel – but in an adaptive way. The ladder that evolving creatures climbed led to greater adaption to the changing world. If Mendel believed in evolution – and whether he did remains a matter of much debate – it was an evolution that occurred within a finite system. The very observation that a particular character trait could be expressed in two opposing ways – round pea versus angular, tall plant versus dwarf – implied limits. Darwin’s evolution was entirely open-ended; Mendel’s, as any good gardener of the time could see, was closed.[24] [25]

How very Goethean – and Spenglerian.

His continuation of the German mission against English science explains, even if it does not entirely excuse, Spengler’s citation of Franz Boas’ now-discredited experiments in craniology in the second volume of The Decline of the West. In his posthumously-published book on Indo-Europeanology, the unfinished but lucid Frühzeit der Weltgeschichte, Spengler cites the contemporary German Nordicist race theorist Hans F. K. Günther in writing that “urbanization is racial decay.”[25] [26] This would seem quite a leap, from citing Boas to citing Günther. However, in the opinion of one historian, Boas and Günther had more in common than they liked to think, because they were both heirs more of the German Idealist tradition in science than what the Anglo-Saxon tradition recognizes as the scientific method.[26] [27] Spengler must have keenly detected this commonality, for his views on racial matters were never synonymous with those of Boas, any more than they were identical to Günther’s.

He probably went too far in his crusade against the Anglo-Saxon scientific tradition, but as we have seen, Spengler was not without his reasons. He was neither the first nor the greatest German philosopher of science to present alternatives to the ruling English paradigms in the sciences, but was rather an heir to a grand tradition. Before dismissing this anti-materialistic tradition as worthless, as today’s historiographers of science still do, we should take into account what it produced.

Darwin’s philosophy of nature was predominantly German; only his Malthusianism, the least interesting aspect of Darwin’s work, was singularly British. As for Einstein, that proficient but unoriginal thinker was absolutely steeped in the German anti-Newtonian tradition, to which he merely put a mathematical formula. These are only the most celebrated examples of scientists influenced by the German tradition defended – maniacally, perhaps, but with noble intentions – in the works of Oswald Spengler.

Whether we consider Spengler’s ideas useful to science or utterly hateful to it, one question remains: Should the German tradition of philosophy of science he defended be taken seriously? Ever since the post-Second World War de-Germanization of Germany, euphemistically called “de-Nazification,” this tradition is now pretty much dead in its own fatherland. But does that make it entirely wrong?

Notes

[1] [28] Luke Hodgkin, A History of Mathematics: From Mesopotamia to Modernity (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013).

[2] [29] See the booklet of the CD Istanbul: Dimitrie Cantemir, 1630-1732, written by Stefan Lemny and translated by Jacqueline Minett.

[3] [30] Eugenia Popescu-Judetz, Prince Dimitrie Cantemir: Theorist and Composer of Turkish Music (Istanbul: Pan Yayıncılık, 1999), p. 34.

[4] [31] Dimitrie Cantemir, The History of the Growth and Decay of the Othman Empire, vol. I, tr. by Nicholas Tindal (London: Knapton, 1734), p. 151, note 14.

[5] [32] Carl Schmitt, The Leviathan in the State Theory of Thomas Hobbes: Meaning and Failure of a Political Symbol, tr. by George Schwab and Erna Hilfstein (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2008), p. 8.

[6] [33] Karin Schutjer, “Goethe’s Kabbalistic Cosmology [34],” Colloquia Germanica, vol. 39, no. 1 (2006).

[7] [35] J. W. von Goethe, Faust, Part Two, Act I, “Imperial Palace” scene; Schopenhauer, The Wisdom of Life, Chapter III, “Property, or What a Man Has.”

[8] [36] Jeremy Naydler (ed.), Goethe on Science: An Anthology of Goethe’s Scientific Writings (Edinburgh: Floris Books, 1996), pp. 65-67.

[9] [37] Erich Ludendorff, The Destruction of Freemasonry Through Revelation of Their Secrets (Mountain City, Tn.: Sacred Truth Publishing), p. 53.

[10] [38] Warren Kenton, Kabbalah: The Divine Plan (New York: HarperCollins, 1996), p. 25.

[11] [39] Schmitt, Leviathan, p. 26.

[12] [40] Gottfried Feder, Manifesto for Breaking the Financial Slavery to Interest, tr. by Alexander Jacob (London: Black House Publishing, 2016), p. 38.

[13] [41] Ibid., pp. 17-18.

[14] [42] See, i.e., Walter Wili, “The Orphic Mysteries and the Greek Spirit,” collected in Joseph Campbell (ed.), The Mysteries: Papers from the Eranos Yearbooks (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1955).

[15] [43] Arthur Schopenhauer, tr. by E. F. J. Payne, The World as Will and Representation, vol. II (Mineola, N.Y.: Dover, 2014), p. 585.

[16] [44] Ronald Douglas Gray, Goethe the Alchemist (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010), p. 6.

[17] [45] Robert J. Richards, The Romantic Conception of Life: Philosophy and Science in the Age of Goethe (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2010), p. 435.

[18] [46] Ibid, pp. 518-526.

[19] [47] Nicholas Boyle, Goethe and the English-speaking World: Essays from the Cambridge Symposium for His 250th Anniversary (Rochester, N.Y.: Camden House, 2012), p. 12.

[20] [48] Oswald Spengler, tr. by Charles Francis Atkinson, The Decline of the West vol. II (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1928), p. 31.

[21] [49] Elizabeth Kolbert, The Sixth Extinction: An Unnatural History (London: Bloomsbury, 2015), p. 94.

[22] [50] From Jünger’s Aladdin’s Problem: “It is astounding to see how inventiveness grows in nature when existence is at stake. This applies to both defense and pursuit. For every missile, an anti-missile is devised. At times, it all looks like sheer braggadocio. This could lead to a stalemate or else to the moment when the opponent says, ‘I give up’, if he does not knock over the chessboard and ruin the game. Darwin did not go that far; in this context, one is better off with Cuvier’s theory of catastrophes.”

[23] [51] See Georges Cuvier, Essay on the Theory of the Earth (London: Forgotten Books, 2012), pp. 125-128 & pp. 145-165.

[24] [52] Robin Marantz Henig, The Monk in the Garden: The Lost and Found Genius of Gregor Mendel, the Father of Genetics (New York: Houghton Mifflin, 2017), p. 125.

[25] [53] Oswald Spengler, Frühzeit der Weltgeschichte (Munich: C. H. Beck, 1966), Fragment 101.

[26] [54] Amos Morris-Reich, “Race, Ideas, and Ideals: A Comparison of Franz Boas and Hans F. K. Günther [55],” History of European Ideas, vol. 32, no. 3 (2006).

« On était exempt de ces fléaux quand on ne s’était pas encore laissé fondre aux délices, quand on n’avait de maître et de serviteur que soi. On s’endurcissait le corps à la peine et au vrai travail ; on le fatiguait à la course, à la chasse, aux exercices du labour. On trouvait au retour une nourriture que la faim toute seule savait rendre agréable. Aussi n’était-il pas besoin d’un si grand attirail de médecins, de fers, de boîtes à remèdes. Toute indisposition était simple comme sa cause : la multiplicité des mets a multiplié les maladies. Pour passer par un seul gosier, vois que de substances combinées par le luxe, dévastateur de la terre et de l’onde ! »

« On était exempt de ces fléaux quand on ne s’était pas encore laissé fondre aux délices, quand on n’avait de maître et de serviteur que soi. On s’endurcissait le corps à la peine et au vrai travail ; on le fatiguait à la course, à la chasse, aux exercices du labour. On trouvait au retour une nourriture que la faim toute seule savait rendre agréable. Aussi n’était-il pas besoin d’un si grand attirail de médecins, de fers, de boîtes à remèdes. Toute indisposition était simple comme sa cause : la multiplicité des mets a multiplié les maladies. Pour passer par un seul gosier, vois que de substances combinées par le luxe, dévastateur de la terre et de l’onde ! » Et d’évoquer la pédophilie festive de nos romains diners :

Et d’évoquer la pédophilie festive de nos romains diners :

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

Writing in 1963, Oliver avoids mention of Yockey’s “culture-distorter” or the Jewish Question (although he makes a nod to that Birchite proxy, the International Communist Conspiracy). Years later, with the “Birch Business” well behind him,

Writing in 1963, Oliver avoids mention of Yockey’s “culture-distorter” or the Jewish Question (although he makes a nod to that Birchite proxy, the International Communist Conspiracy). Years later, with the “Birch Business” well behind him,

Car pour lui, nos sociétés occidentales sont caractérisées par le passage d’une phase solide de la modernité, stable, immobile et enracinée, à une phase liquide, fluide, volatile et néo-nomade où tout semble se désagréger et se liquéfier, phase « dans laquelle les formes sociales (les structures qui limitent les choix individuels, les institutions qui veillent au maintien des traditions, les modes de comportement acceptables) ne peuvent plus se maintenir durablement en l’état parce qu’elles se décomposent en moins de temps qu’il ne leur en faut pour être forgées et se solidifier

Car pour lui, nos sociétés occidentales sont caractérisées par le passage d’une phase solide de la modernité, stable, immobile et enracinée, à une phase liquide, fluide, volatile et néo-nomade où tout semble se désagréger et se liquéfier, phase « dans laquelle les formes sociales (les structures qui limitent les choix individuels, les institutions qui veillent au maintien des traditions, les modes de comportement acceptables) ne peuvent plus se maintenir durablement en l’état parce qu’elles se décomposent en moins de temps qu’il ne leur en faut pour être forgées et se solidifier

Above all, we must shed from within ourselves the idea that we, personally, are “entitled” to free speech or that the masses can welcome the whole truth. If we still have these notions, then we are in fact still slaves to our time’s democratic naïveté. No, free speech is at once a duty and a prize, to be exercised only once we have become worthy, by our own personal excellence and self-mastery. That was, at any rate, the way Diogenes the Cynic saw things, calling free speech “the finest thing of all in life.”

Above all, we must shed from within ourselves the idea that we, personally, are “entitled” to free speech or that the masses can welcome the whole truth. If we still have these notions, then we are in fact still slaves to our time’s democratic naïveté. No, free speech is at once a duty and a prize, to be exercised only once we have become worthy, by our own personal excellence and self-mastery. That was, at any rate, the way Diogenes the Cynic saw things, calling free speech “the finest thing of all in life.”

One might fairly assert that Berdyaev did himself little good publicity-wise by cultivating a style of presentation which, while often resolving its thought-processes in a brilliant, aphoristic utterance, nevertheless takes its time, looks at phenomena from every aspect, analyzes every proposition to its last comma and period, and tends to assert its findings bluntly rather than to argue them politely in the proper syllogistic manner. In Berdyaev’s defense, a sensitive reader might justifiably interpret his leisurely examination of the modern agony as a deliberate and quite appropriate response to the upheavals that harried him from the time of the 1905 Revolution to the German occupation of France during World War II. If the Twentieth Century insisted on being precipitate and eruptive in everything, without regard to the lethal mayhem it wreaked, then, by God, Berdyaev, regarding his agenda, would take his sweet time. Not for him the constant mobilized agitation, the sloganeering hysteria, the goose-stepping and dive-bombing spasms of modernity in full self-apocalypse. That is another characteristic of Berdyaev – he is all at once leisurely in style and apocalyptic in content. Berdyaev was quite as apocalyptic in his expository prose as his idol Fyodor Dostoevsky was in his ethical narrative, and being a voice of revelation he expressed himself, again like Dostoevsky, in profoundly religious and indelibly Christian terms. Berdyaev follows Dostoevsky and anticipates Alexander Solzhenitsyn in his conviction that no society can murder God, as Western secular society has gleefully done, and then go its insouciant way, without consequence.

One might fairly assert that Berdyaev did himself little good publicity-wise by cultivating a style of presentation which, while often resolving its thought-processes in a brilliant, aphoristic utterance, nevertheless takes its time, looks at phenomena from every aspect, analyzes every proposition to its last comma and period, and tends to assert its findings bluntly rather than to argue them politely in the proper syllogistic manner. In Berdyaev’s defense, a sensitive reader might justifiably interpret his leisurely examination of the modern agony as a deliberate and quite appropriate response to the upheavals that harried him from the time of the 1905 Revolution to the German occupation of France during World War II. If the Twentieth Century insisted on being precipitate and eruptive in everything, without regard to the lethal mayhem it wreaked, then, by God, Berdyaev, regarding his agenda, would take his sweet time. Not for him the constant mobilized agitation, the sloganeering hysteria, the goose-stepping and dive-bombing spasms of modernity in full self-apocalypse. That is another characteristic of Berdyaev – he is all at once leisurely in style and apocalyptic in content. Berdyaev was quite as apocalyptic in his expository prose as his idol Fyodor Dostoevsky was in his ethical narrative, and being a voice of revelation he expressed himself, again like Dostoevsky, in profoundly religious and indelibly Christian terms. Berdyaev follows Dostoevsky and anticipates Alexander Solzhenitsyn in his conviction that no society can murder God, as Western secular society has gleefully done, and then go its insouciant way, without consequence. By the mid-1930s, in the extended aftermaths of World War I and the Bolshevik Revolution, and in the context of the ideological dictatorships, the conviction had impressed itself on Berdyaev that the existing Western arrangement, pathologically disordered, betokened the dissolution of civilization, not its continuance. In The Fate of Man in the Modern World, Berdyaev summarizes his discovery. In modernity, a brutal phase of history, the human collectivity must endure the effects of ancestral decisions, which subsequent generations might have altered but chose instead to endorse, and live miserably or perhaps die according to them. Modernity is thus history passing judgment on history, as Berdyaev sees it; and modernity’s brutality, its nastiness, and its inhumanity all stem from the same cause – the repudiation of God and the substitution in His place of a necessarily degraded “natural-social realm.” Berdyaev writes, “We are witnessing the socialization and nationalization of human souls, of man himself.” Some causes of this degeneracy lie proximate to their effects. “Modern bestialism and its attendant dehumanization are based upon idolatry, the worship of technics, race or class or production, and upon the adaptation of atavistic instincts to worship.” Again, “Dehumanization is… the mechanization of human life.” With mechanization comes also the “dissolution of man into… functions.”

By the mid-1930s, in the extended aftermaths of World War I and the Bolshevik Revolution, and in the context of the ideological dictatorships, the conviction had impressed itself on Berdyaev that the existing Western arrangement, pathologically disordered, betokened the dissolution of civilization, not its continuance. In The Fate of Man in the Modern World, Berdyaev summarizes his discovery. In modernity, a brutal phase of history, the human collectivity must endure the effects of ancestral decisions, which subsequent generations might have altered but chose instead to endorse, and live miserably or perhaps die according to them. Modernity is thus history passing judgment on history, as Berdyaev sees it; and modernity’s brutality, its nastiness, and its inhumanity all stem from the same cause – the repudiation of God and the substitution in His place of a necessarily degraded “natural-social realm.” Berdyaev writes, “We are witnessing the socialization and nationalization of human souls, of man himself.” Some causes of this degeneracy lie proximate to their effects. “Modern bestialism and its attendant dehumanization are based upon idolatry, the worship of technics, race or class or production, and upon the adaptation of atavistic instincts to worship.” Again, “Dehumanization is… the mechanization of human life.” With mechanization comes also the “dissolution of man into… functions.” One of the pleasures of reading backwards into the dissentient discussion of modernity is the discovery of contrarian judgments, such as Berdyaev’s concerning the Florentine revival of classicism, that stand in refreshing variance with existing conformist opinion. Will Durant sums up the standing textbook view of the Renaissance in Volume 5 (1953) of his Story of Civilization. When “the humanists captured the mind of Italy,” as Durant writes, they “turned it from religion to philosophy, from heaven to earth, and revealed to an astonished generation the riches of pagan thought and art.” Having accomplished all that, according once again to Durant, the umanisti reorganized education on the premise that “the proper study of man was now to be man, in all the potential strength and beauty of his body, in all the joy and pain of his senses and feelings, [and] in all the frail majesty of his reason.” Durant’s tone implies something beyond mere description; it implies laudatory approval. Before turning back to Berdyaev, it is worth remarking how obviously wrongheaded Durant is in so few words. Insofar as the umanisti adopted Platonism – or rather late Neo-Platonism – they cannot exactly be said exclusively to have “turned” the general attention “from heaven to earth.” Rather, they refocused that attention from the transcendent God of the Bible and the Church Doctors to the celestial powers of Porphryian cosmology, the ones who might be manipulated by magical formulas to serve their earthly masters. Now in adopting Protagoras’ maxim that, man is the measure, the umanisti did, in fact, “terrestrialize” thinking. They achieved their end, however, only at the cost of swapping a cosmic-teleological perspective for an egocentric-instrumental one. It was an act of self-demotion. Had Berdyaev lived to read Durant’s Renaissance, he himself would inevitably have remarked these easy-to-spot misconceptions.

One of the pleasures of reading backwards into the dissentient discussion of modernity is the discovery of contrarian judgments, such as Berdyaev’s concerning the Florentine revival of classicism, that stand in refreshing variance with existing conformist opinion. Will Durant sums up the standing textbook view of the Renaissance in Volume 5 (1953) of his Story of Civilization. When “the humanists captured the mind of Italy,” as Durant writes, they “turned it from religion to philosophy, from heaven to earth, and revealed to an astonished generation the riches of pagan thought and art.” Having accomplished all that, according once again to Durant, the umanisti reorganized education on the premise that “the proper study of man was now to be man, in all the potential strength and beauty of his body, in all the joy and pain of his senses and feelings, [and] in all the frail majesty of his reason.” Durant’s tone implies something beyond mere description; it implies laudatory approval. Before turning back to Berdyaev, it is worth remarking how obviously wrongheaded Durant is in so few words. Insofar as the umanisti adopted Platonism – or rather late Neo-Platonism – they cannot exactly be said exclusively to have “turned” the general attention “from heaven to earth.” Rather, they refocused that attention from the transcendent God of the Bible and the Church Doctors to the celestial powers of Porphryian cosmology, the ones who might be manipulated by magical formulas to serve their earthly masters. Now in adopting Protagoras’ maxim that, man is the measure, the umanisti did, in fact, “terrestrialize” thinking. They achieved their end, however, only at the cost of swapping a cosmic-teleological perspective for an egocentric-instrumental one. It was an act of self-demotion. Had Berdyaev lived to read Durant’s Renaissance, he himself would inevitably have remarked these easy-to-spot misconceptions. In The Meaning of the Creative Act, Berdyaev takes Benvenuto Cellini – a much-romanticized figure, using the adjective “romanticized” in its populist connotation – for one signal specimen of the “Renaissance Man.” Berdyaev is fully aware that describing the Renaissance simply as a revival of paganism amounts to inexcusable naïvety. “The great Italian Renaissance,” he writes, “is vastly more complex than is usually thought.” Berdyaev sees the so-called rebirth of classical letters and art as a botched experiment in dialectics, during which “there occurred such a powerful clash between pagan and Christian elements in human nature as had never occurred before.” The tragedy of the Renaissance consists in the fact, as Berdyaev insists, that, “the Christian transcendental sense of being had so profoundly possessed men’s nature that the integral and final confession of the immanent ideals of life became impossible.” Cellini embodies the conflict. In his life, no matter how declaredly “pagan,” “there is still too much of Christianity.” Cellini could never have been “an integral man,” as his moral degeneracy and spasmodic repentance attested. In Berdyaev’s argument, Christianity has effectuated, however imperfectly, a theurgic alteration in being towards a higher level. Cellini’s life illustrates the point. The attempt to return to being at a lower level must fail, as it failed for Cellini; it can bring only suffering to the subject and in the milieu that attempts it.

In The Meaning of the Creative Act, Berdyaev takes Benvenuto Cellini – a much-romanticized figure, using the adjective “romanticized” in its populist connotation – for one signal specimen of the “Renaissance Man.” Berdyaev is fully aware that describing the Renaissance simply as a revival of paganism amounts to inexcusable naïvety. “The great Italian Renaissance,” he writes, “is vastly more complex than is usually thought.” Berdyaev sees the so-called rebirth of classical letters and art as a botched experiment in dialectics, during which “there occurred such a powerful clash between pagan and Christian elements in human nature as had never occurred before.” The tragedy of the Renaissance consists in the fact, as Berdyaev insists, that, “the Christian transcendental sense of being had so profoundly possessed men’s nature that the integral and final confession of the immanent ideals of life became impossible.” Cellini embodies the conflict. In his life, no matter how declaredly “pagan,” “there is still too much of Christianity.” Cellini could never have been “an integral man,” as his moral degeneracy and spasmodic repentance attested. In Berdyaev’s argument, Christianity has effectuated, however imperfectly, a theurgic alteration in being towards a higher level. Cellini’s life illustrates the point. The attempt to return to being at a lower level must fail, as it failed for Cellini; it can bring only suffering to the subject and in the milieu that attempts it. Berdyaev emphasizes the drastic diremption of the Quattrocento by reminding his readers of the earliest, purely Christian phase of the Renaissance. “It was in mystic Italy, in Joachim de Floris, that the prophetic hope of a new world-epoch of Christianity was born, an epoch of love, and epoch of spirit.” The pre-perspective painters also loom large in Berdyaev’s appreciation: “Giotto and all the early religious painting of Italy, Arnolfi and others, followed St. Francis and Dante.” Where Raphael and Leonardo, as Berdyaev intimates, worked in a realm of literalism – copying from nature in a mechanical way – these earlier figures exercised their genius on the level of “symbolism.” In Berdyaev’s view, “mystic Italy” prefigures late-Nineteenth Century Symbolism, a movement that he found rich in meaning and hopeful in implication. Joachim, Dante, and St. Francis all violated what Berdyaev calls “the bounds of the average, ordered, canonic way”; their “revolt” precludes “any sort of compromise with the bourgeois spirit,” as did the later revolt of Charles Baudelaire, Henrik Ibsen, and Joris-Karl Huysmans. Whether it is Giotto or Baudelaire, the theurgic impulse aims, not to “create culture,” but to create “new being.”

Berdyaev emphasizes the drastic diremption of the Quattrocento by reminding his readers of the earliest, purely Christian phase of the Renaissance. “It was in mystic Italy, in Joachim de Floris, that the prophetic hope of a new world-epoch of Christianity was born, an epoch of love, and epoch of spirit.” The pre-perspective painters also loom large in Berdyaev’s appreciation: “Giotto and all the early religious painting of Italy, Arnolfi and others, followed St. Francis and Dante.” Where Raphael and Leonardo, as Berdyaev intimates, worked in a realm of literalism – copying from nature in a mechanical way – these earlier figures exercised their genius on the level of “symbolism.” In Berdyaev’s view, “mystic Italy” prefigures late-Nineteenth Century Symbolism, a movement that he found rich in meaning and hopeful in implication. Joachim, Dante, and St. Francis all violated what Berdyaev calls “the bounds of the average, ordered, canonic way”; their “revolt” precludes “any sort of compromise with the bourgeois spirit,” as did the later revolt of Charles Baudelaire, Henrik Ibsen, and Joris-Karl Huysmans. Whether it is Giotto or Baudelaire, the theurgic impulse aims, not to “create culture,” but to create “new being.” Caliban and emergent mechanical mastery taken together might well form an image to make one skip a breath. For once the “ebullience” of liberation-from-religion neutralizes “spiritual authority” and stimulates the “differentiation,” natural man, ego-driven and undisciplined, is bound to end up in possession of the Neo-Atlantean instrumentality, whereupon the prospect opens out on no end of mischief. Berdyaev’s historical diagnosis indeed runs in this direction. He even formulates the law of what he calls “the strange paradox”: “Man’s self-affirmation leads to his perdition; the free play of human forces unconnected with any higher aim brings about the exhaustion of man’s creative powers.” The Protestant Reformation of the German North and the so-called Enlightenment of the Eighteenth Century in France and the German states represent, in Berdyaev’s scheme, ever-lower stages of this descent into dissolution rather than the steps-upward of the ready version of Progress. The paradox of humanism consists in its having “affirmed man’s self-confidence” while also having “debased [man] by ceasing to regard him as a being of a higher and divine origin.”

Caliban and emergent mechanical mastery taken together might well form an image to make one skip a breath. For once the “ebullience” of liberation-from-religion neutralizes “spiritual authority” and stimulates the “differentiation,” natural man, ego-driven and undisciplined, is bound to end up in possession of the Neo-Atlantean instrumentality, whereupon the prospect opens out on no end of mischief. Berdyaev’s historical diagnosis indeed runs in this direction. He even formulates the law of what he calls “the strange paradox”: “Man’s self-affirmation leads to his perdition; the free play of human forces unconnected with any higher aim brings about the exhaustion of man’s creative powers.” The Protestant Reformation of the German North and the so-called Enlightenment of the Eighteenth Century in France and the German states represent, in Berdyaev’s scheme, ever-lower stages of this descent into dissolution rather than the steps-upward of the ready version of Progress. The paradox of humanism consists in its having “affirmed man’s self-confidence” while also having “debased [man] by ceasing to regard him as a being of a higher and divine origin.” Berdyaev certainly never stood alone in his diagnosis of modern despiritualization. Similar if not identical insights occur under the scrutiny not only of the other writers mentioned at the outset (from Blixen to Undset) but more recently in the work of Jacques Barzun (especially in his great late-career book, From Dawn to Decadence), Roberto Calasso, Jacques Ellul, René Girard, Paul Gottfried, Kenneth Minogue, Roger Scruton, and Eric Voegelin, to name but a few more or less at random. Yet however many names one crowds together in a sentence, the shared judgment remains in the minority and under exclusion. In the prevailing liberal-progressive view, the world is monistic and one-dimensional: Everything is race, class, gender, or the state. In Berdyaev’s dissenting view, the world is dualistic and three-dimensional: “Christianity reveals and confirms man’s belonging to two planes of being, to the spiritual and to the natural-social, to the Kingdom of God and the Kingdom of Caesar.” It is the first dimension – actually a double dimension – of height and depth that guarantees freedom in the second dimension. The denial of the realm of height and depth is therefore the essence, a totally negative essence, of the Kingdom of Caesar intransigent. Berdyaev values man over society because he values spirit over matter,” the sole concern of men on the “natural-social” plane. The existing society indeed values matter exclusively, to the extent of having fixated itself on the finished product – the latest cell phone or handheld electronic game-player or that contradiction-in-the-adjective, the smart car – while deputizing foreign nations to produce these things. This same society, a kind of super cargo-cult, deracinated, demoralized, despiritualized, badly educated, deluged in pornography and ideology, and as conformist as any primitive tribe, vigorously denies the spirit, where not explicitly as articulate theory then in behavior.

Berdyaev certainly never stood alone in his diagnosis of modern despiritualization. Similar if not identical insights occur under the scrutiny not only of the other writers mentioned at the outset (from Blixen to Undset) but more recently in the work of Jacques Barzun (especially in his great late-career book, From Dawn to Decadence), Roberto Calasso, Jacques Ellul, René Girard, Paul Gottfried, Kenneth Minogue, Roger Scruton, and Eric Voegelin, to name but a few more or less at random. Yet however many names one crowds together in a sentence, the shared judgment remains in the minority and under exclusion. In the prevailing liberal-progressive view, the world is monistic and one-dimensional: Everything is race, class, gender, or the state. In Berdyaev’s dissenting view, the world is dualistic and three-dimensional: “Christianity reveals and confirms man’s belonging to two planes of being, to the spiritual and to the natural-social, to the Kingdom of God and the Kingdom of Caesar.” It is the first dimension – actually a double dimension – of height and depth that guarantees freedom in the second dimension. The denial of the realm of height and depth is therefore the essence, a totally negative essence, of the Kingdom of Caesar intransigent. Berdyaev values man over society because he values spirit over matter,” the sole concern of men on the “natural-social” plane. The existing society indeed values matter exclusively, to the extent of having fixated itself on the finished product – the latest cell phone or handheld electronic game-player or that contradiction-in-the-adjective, the smart car – while deputizing foreign nations to produce these things. This same society, a kind of super cargo-cult, deracinated, demoralized, despiritualized, badly educated, deluged in pornography and ideology, and as conformist as any primitive tribe, vigorously denies the spirit, where not explicitly as articulate theory then in behavior.

« Walter Laqueur l’a montré : une vie accélérée remplace l’atmosphère calme et recueillie de l’avant-guerre. De cent mille voitures particulières au sortir de la guerre, l’Allemagne passe à un million deux cent mille dix ans plus tard.

« Walter Laqueur l’a montré : une vie accélérée remplace l’atmosphère calme et recueillie de l’avant-guerre. De cent mille voitures particulières au sortir de la guerre, l’Allemagne passe à un million deux cent mille dix ans plus tard. Conclusion apocalyptique :

Conclusion apocalyptique :

Votre publication a eu récemment l’occasion de faire écho de façon favorable au livre de Bernard-Henri Lévy, Le Testament de Dieu, publié aux Éditions Grasset dans la collection « Figures ». Je pense que votre bonne foi a été surprise. [Il suffit, en effet, de jeter un rapide coup d’œil sur ce livre pour s’apercevoir que loin d’être un ouvrage majeur de philosophie politique, il fourmille littéralement d’erreurs grossières, d’à-peu-près, de citations fausses, ou d’affirmations délirantes. Devant l’énorme tapage publicitaire dont bénéficie cet ouvrage, et indépendamment de toute question politique et notamment de la nécessaire lutte contre le totalitarisme,

Votre publication a eu récemment l’occasion de faire écho de façon favorable au livre de Bernard-Henri Lévy, Le Testament de Dieu, publié aux Éditions Grasset dans la collection « Figures ». Je pense que votre bonne foi a été surprise. [Il suffit, en effet, de jeter un rapide coup d’œil sur ce livre pour s’apercevoir que loin d’être un ouvrage majeur de philosophie politique, il fourmille littéralement d’erreurs grossières, d’à-peu-près, de citations fausses, ou d’affirmations délirantes. Devant l’énorme tapage publicitaire dont bénéficie cet ouvrage, et indépendamment de toute question politique et notamment de la nécessaire lutte contre le totalitarisme,  Il est bon pourtant d’analyser les arguments de Bernard-Henri Lévy. Il y en a de quatre types :

Il est bon pourtant d’analyser les arguments de Bernard-Henri Lévy. Il y en a de quatre types :

Mais Fustel décrit la corvée démocratique au jour le jour (pp.451-452) :

Mais Fustel décrit la corvée démocratique au jour le jour (pp.451-452) :

For those seeking something like a “how to” guide for living as a Traditionalist, it is mainly the second division of the book (“In the World Where God is Dead”) that offers something, and chiefly it is to be found in Chapter Eight: “The Transcendent Dimension – ‘Life’ and ‘More than Life.’” My purpose in this essay is to piece together the miniature “survival manual” provided by Chapter Eight – some of which consists of little more than hints, conveyed in Evola’s often frustratingly opaque style. It is my view that what we find in these pages is of profound importance for anyone struggling to hold on to his sanity in the face of the decadence and dishonesty of today’s world. It is also essential reading for anyone seeking to achieve the ideal of “self-overcoming” taught by Evola – seeking, in other words, to “ride the tiger.”

For those seeking something like a “how to” guide for living as a Traditionalist, it is mainly the second division of the book (“In the World Where God is Dead”) that offers something, and chiefly it is to be found in Chapter Eight: “The Transcendent Dimension – ‘Life’ and ‘More than Life.’” My purpose in this essay is to piece together the miniature “survival manual” provided by Chapter Eight – some of which consists of little more than hints, conveyed in Evola’s often frustratingly opaque style. It is my view that what we find in these pages is of profound importance for anyone struggling to hold on to his sanity in the face of the decadence and dishonesty of today’s world. It is also essential reading for anyone seeking to achieve the ideal of “self-overcoming” taught by Evola – seeking, in other words, to “ride the tiger.”

Still, through this gloom one may detect exactly the position that Evola correctly attributes to Nietzsche. Like Kant, Nietzsche demands that the overman practice autonomy, that he give a law to himself. However, Kant held that our self-legislation simultaneously legislates for others: the law I give to myself is the law I would give to any other rational being. The overman, by contrast, legislates for himself only – or possibly for himself and the tiny number of men like him. If we recognize fundamental qualitative differences between human types, then we must consider the possibility that different rules apply to them. Fundamental to Kant’s position is the egalitarian assertion that people do not get to “play by their own rules” (indeed, for Kant the claim to be an exception to general rules, or to make an exception for oneself, is the marker of immorality). If we reject this egalitarianism, then it does indeed follow that certain special individuals get to play by their own rules.

Still, through this gloom one may detect exactly the position that Evola correctly attributes to Nietzsche. Like Kant, Nietzsche demands that the overman practice autonomy, that he give a law to himself. However, Kant held that our self-legislation simultaneously legislates for others: the law I give to myself is the law I would give to any other rational being. The overman, by contrast, legislates for himself only – or possibly for himself and the tiny number of men like him. If we recognize fundamental qualitative differences between human types, then we must consider the possibility that different rules apply to them. Fundamental to Kant’s position is the egalitarian assertion that people do not get to “play by their own rules” (indeed, for Kant the claim to be an exception to general rules, or to make an exception for oneself, is the marker of immorality). If we reject this egalitarianism, then it does indeed follow that certain special individuals get to play by their own rules.

As with the passions, the average man “owns” his moods: “this unhappiness is mine, it is me,” he says, in effect. The superior man learns to see his moods as if they were the weather – or, better yet, as if they were minor demons besetting him: external mischief makers, to whom he has the power to say “yes” or “no.” The superior man, upon finding that he feels unhappiness, says “ah yes, there it is again.” Immediately, seeing “his” unhappiness as other – as a habit, a pattern, a kind of passing mental cloud – he refuses identification with it. And he sets about intrepidly conquering unhappiness. He will not acquiesce to it.

As with the passions, the average man “owns” his moods: “this unhappiness is mine, it is me,” he says, in effect. The superior man learns to see his moods as if they were the weather – or, better yet, as if they were minor demons besetting him: external mischief makers, to whom he has the power to say “yes” or “no.” The superior man, upon finding that he feels unhappiness, says “ah yes, there it is again.” Immediately, seeing “his” unhappiness as other – as a habit, a pattern, a kind of passing mental cloud – he refuses identification with it. And he sets about intrepidly conquering unhappiness. He will not acquiesce to it. If we consult the context in which the quote appears – an important section of Twilight of the Idols – Nietzsche offers us little help in understanding specifically what he means by “the distance that separates us.” But the surrounding context is a goldmine of reflections on the superior type, and it is surprising that Evola does not quote it more fully. Nietzsche remarks that “war educates for freedom” (a point on which Evola reflects at length in his Metaphysics of War), then writes:

If we consult the context in which the quote appears – an important section of Twilight of the Idols – Nietzsche offers us little help in understanding specifically what he means by “the distance that separates us.” But the surrounding context is a goldmine of reflections on the superior type, and it is surprising that Evola does not quote it more fully. Nietzsche remarks that “war educates for freedom” (a point on which Evola reflects at length in his Metaphysics of War), then writes: Evola’s very long sentence about the superior man now ends with the following summation:

Evola’s very long sentence about the superior man now ends with the following summation:

First, a few words about Spengler’s writing in this book, which I found to be terrible: like Heidegger, overly dense and sometimes nearly incomprehensible in the pompous old school German style (in contrast, Nietzsche, particularly apart from Zarathustra, was exceedingly comprehensible and easily understandable). Contrary to all of Spengler’s breathless fans, I did not find his magnum opus to be very well written. It’s a terribly boring, turgid compilation of rambling prose. I can only imagine the full-scale version is worse (and if memory serves, it was). Another point is that Spengler’s deconstructivism is highly annoying to the more empiricist among us, his idea that Nature is a function of a particular culture. Well (and the same applies to some of Yockey’s [plagiarized] rambling on the subject), for some cultures, Nature apparently is a more accurate “function” of reality than for others, and this more accurate representation of objective reality has real world consequences that cannot be evaded.

First, a few words about Spengler’s writing in this book, which I found to be terrible: like Heidegger, overly dense and sometimes nearly incomprehensible in the pompous old school German style (in contrast, Nietzsche, particularly apart from Zarathustra, was exceedingly comprehensible and easily understandable). Contrary to all of Spengler’s breathless fans, I did not find his magnum opus to be very well written. It’s a terribly boring, turgid compilation of rambling prose. I can only imagine the full-scale version is worse (and if memory serves, it was). Another point is that Spengler’s deconstructivism is highly annoying to the more empiricist among us, his idea that Nature is a function of a particular culture. Well (and the same applies to some of Yockey’s [plagiarized] rambling on the subject), for some cultures, Nature apparently is a more accurate “function” of reality than for others, and this more accurate representation of objective reality has real world consequences that cannot be evaded. The sections “Race is Style” and “People and Nation” are of course relevant from a racial nationalist perspective, and reflects Spengler’s anti-scientific stupidity, this time about biological race. Those of you familiar with Yockey’s wrong-headed assertions on this topic will see all the same in Spengler’s work (from which Yockey lifted his assertions). This has been critiqued by many – from Revilo Oliver to myself – and it is not necessary to rehash all of the arguments against the Spenglerian (Boasian) deconstructivist attitudes toward biological race. We can just shake our heads sadly about Spengler’s racial fantasies – that is as absurd as that of any hysterical leftist SJW race-denier – and move on to other issues.

The sections “Race is Style” and “People and Nation” are of course relevant from a racial nationalist perspective, and reflects Spengler’s anti-scientific stupidity, this time about biological race. Those of you familiar with Yockey’s wrong-headed assertions on this topic will see all the same in Spengler’s work (from which Yockey lifted his assertions). This has been critiqued by many – from Revilo Oliver to myself – and it is not necessary to rehash all of the arguments against the Spenglerian (Boasian) deconstructivist attitudes toward biological race. We can just shake our heads sadly about Spengler’s racial fantasies – that is as absurd as that of any hysterical leftist SJW race-denier – and move on to other issues. Those are mere details however. Important details, but not the fundamental, the main thesis. So, what about the main thesis of his work? The overall idea of cyclical history? Yockey’s lifting of that idea in his own work? Rereading Spengler’s major thesis hasn’t changed my mind about it in any major way, but there are some further points to make.

Those are mere details however. Important details, but not the fundamental, the main thesis. So, what about the main thesis of his work? The overall idea of cyclical history? Yockey’s lifting of that idea in his own work? Rereading Spengler’s major thesis hasn’t changed my mind about it in any major way, but there are some further points to make. Let’s get back to Spengler’s content, and some of my objections alluded to above. Thus, as far as content goes, my “take” on it remains the same; I agree with much but I disagree with much as well, particularly the “pessimistic” inevitability of it, and the smug arrogance in suggesting, or implying, that disagreement with that aspect of the work implies some sort of mental weakness, delusion, or cowardice on the part of the reader. Spengler himself suggests that he “truth” of the book is a “truth” for him, a “truth” for a particular Culture in a particular time, and should not necessarily be viewed as an absolute truth in any or every sense (indeed, it everything from science to mathematics is, according to Spengler, formed by the Culture which creates it, and is thus no absolute in any universal sense, then we can quote Pilate ‘“what is truth?”). Therefore, my “truth” in the current year leads me to conclusions different from Spengler; one can again assert that Spengler himself, by writing the book and outlining he problem, himself undermined his assertion of inevitability, since know we can understand the trajectories of Cultures and, possibly, how to affect those trajectories.

Let’s get back to Spengler’s content, and some of my objections alluded to above. Thus, as far as content goes, my “take” on it remains the same; I agree with much but I disagree with much as well, particularly the “pessimistic” inevitability of it, and the smug arrogance in suggesting, or implying, that disagreement with that aspect of the work implies some sort of mental weakness, delusion, or cowardice on the part of the reader. Spengler himself suggests that he “truth” of the book is a “truth” for him, a “truth” for a particular Culture in a particular time, and should not necessarily be viewed as an absolute truth in any or every sense (indeed, it everything from science to mathematics is, according to Spengler, formed by the Culture which creates it, and is thus no absolute in any universal sense, then we can quote Pilate ‘“what is truth?”). Therefore, my “truth” in the current year leads me to conclusions different from Spengler; one can again assert that Spengler himself, by writing the book and outlining he problem, himself undermined his assertion of inevitability, since know we can understand the trajectories of Cultures and, possibly, how to affect those trajectories. That is related to an important deficit in the work of Spengler that I have read. He describes the lifecycle of High Cultures, but never really dissects why the cultures inevitably (or so he says) move from Culture to Civilization to Fellahdom. What actually are the mechanistic causes of Spring to Summer to Fall to Winter? I guess that Spengler (and Yockey) would just say that it is what it is, that the Culture is life an organism that grows old and dies. The problem is that this analogy is just that, an analogy. A Culture is composed of living organisms, humans, but is itself not alive. And esoteric rambling about a “cosmic beat” explains nothing. If ones buys into the Spenglerian premise, then some rigorous analysis as to why High Cultures progress in particular ways is necessary. We need an anatomical and molecular analysis of the “living organism” of the High Culture. Does Frost’s genetic pacification play a role? The cycle, noted by Hamilton, of barbarian invasions, the influx of altruism genes, followed by the aging of the civilization at which point fresh barbarian genes are required to spark a renaissance in the depleted fellhahs? The moral decay that occurs with too much luxury, too much wealth, too much power? A form of memetic exhaustion?

That is related to an important deficit in the work of Spengler that I have read. He describes the lifecycle of High Cultures, but never really dissects why the cultures inevitably (or so he says) move from Culture to Civilization to Fellahdom. What actually are the mechanistic causes of Spring to Summer to Fall to Winter? I guess that Spengler (and Yockey) would just say that it is what it is, that the Culture is life an organism that grows old and dies. The problem is that this analogy is just that, an analogy. A Culture is composed of living organisms, humans, but is itself not alive. And esoteric rambling about a “cosmic beat” explains nothing. If ones buys into the Spenglerian premise, then some rigorous analysis as to why High Cultures progress in particular ways is necessary. We need an anatomical and molecular analysis of the “living organism” of the High Culture. Does Frost’s genetic pacification play a role? The cycle, noted by Hamilton, of barbarian invasions, the influx of altruism genes, followed by the aging of the civilization at which point fresh barbarian genes are required to spark a renaissance in the depleted fellhahs? The moral decay that occurs with too much luxury, too much wealth, too much power? A form of memetic exhaustion?  I maintain that those of us in the interregnum between High Cultures have the power to shape

I maintain that those of us in the interregnum between High Cultures have the power to shape  Speaking of Russia, another part of Spengler’s work that I found reasonably well argued and somewhat convincing (as well as fairly novel) is his idea of applying the concept of pseudomorphosis to human populations. In particular, one cannot really dispute some of his points about the Magian and Russian cultures in this regard, but when he says that Antony should have won at Actium – what nonsense is that? So, that Rome should have become more tainted with Near Eastern cults and ideas even more than it was? What’s the opposite of pseudomorphosis – where a Civilization becomes memetically conquered by a meme originating from a young Culture? How did the memetic virus of Christianity infect the West? Wouldn’t it have been worse if Actium was won by the East? When Spengler writes of “syncretism” he begins to touch upon this reversal, which eventually goes in both directions (and as Type I “movement” apologists for Christianity like to tell us, that religion was eventually “Germanized” in the West).

Speaking of Russia, another part of Spengler’s work that I found reasonably well argued and somewhat convincing (as well as fairly novel) is his idea of applying the concept of pseudomorphosis to human populations. In particular, one cannot really dispute some of his points about the Magian and Russian cultures in this regard, but when he says that Antony should have won at Actium – what nonsense is that? So, that Rome should have become more tainted with Near Eastern cults and ideas even more than it was? What’s the opposite of pseudomorphosis – where a Civilization becomes memetically conquered by a meme originating from a young Culture? How did the memetic virus of Christianity infect the West? Wouldn’t it have been worse if Actium was won by the East? When Spengler writes of “syncretism” he begins to touch upon this reversal, which eventually goes in both directions (and as Type I “movement” apologists for Christianity like to tell us, that religion was eventually “Germanized” in the West). And if Spengler’s main thesis is flawed by its own self-realization, what can one say about his side ideas? Those, particularly dealing with science, are absolute hogwash. In that sense, Spengler is over-rated, never mind his poor writing, including his horrifically turgid style. Yockey may have been offended by this “blasphemy” against his idol – “The Philosopher of History” – but it is nevertheless warranted.

And if Spengler’s main thesis is flawed by its own self-realization, what can one say about his side ideas? Those, particularly dealing with science, are absolute hogwash. In that sense, Spengler is over-rated, never mind his poor writing, including his horrifically turgid style. Yockey may have been offended by this “blasphemy” against his idol – “The Philosopher of History” – but it is nevertheless warranted.

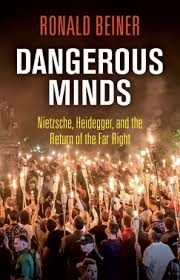

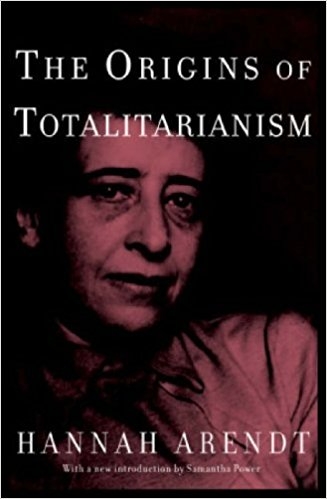

Ronald Beiner is a Canadian Jewish political theorist who teaches at the University of Toronto. I’ve been reading his work since the early 1990s, starting with What’s the Matter with Liberalism? (1992). I have always admired Beiner’s clear and lively writing and his ability to see straight through jargon and cant to hone in on the flaws of the positions he examines. He is also refreshingly free of Left-wing sectarianism and willing to engage with political theorists of the Right, like Leo Strauss, Eric Voegelin, Michael Oakeshott, and Hans-Georg Gadamer. Thus, although I was delighted that a theorist of his caliber had decided to write a book on the contemporary far Right, I was also worried that he might, after a typically open and searching engagement with our outlook, discover some fatal flaw.

Ronald Beiner is a Canadian Jewish political theorist who teaches at the University of Toronto. I’ve been reading his work since the early 1990s, starting with What’s the Matter with Liberalism? (1992). I have always admired Beiner’s clear and lively writing and his ability to see straight through jargon and cant to hone in on the flaws of the positions he examines. He is also refreshingly free of Left-wing sectarianism and willing to engage with political theorists of the Right, like Leo Strauss, Eric Voegelin, Michael Oakeshott, and Hans-Georg Gadamer. Thus, although I was delighted that a theorist of his caliber had decided to write a book on the contemporary far Right, I was also worried that he might, after a typically open and searching engagement with our outlook, discover some fatal flaw.

Beiner doesn’t offer a very clear account of why Nietzsche thinks liberalism undermines human nobility. The short answer is that it is simply the political application of the slave revolt in morals, in which the aristocratic virtues of the ancients were transmuted into Christian and eventually liberal vices, and the vices of the enslaved and downtrodden were transmuted into virtues.

Beiner doesn’t offer a very clear account of why Nietzsche thinks liberalism undermines human nobility. The short answer is that it is simply the political application of the slave revolt in morals, in which the aristocratic virtues of the ancients were transmuted into Christian and eventually liberal vices, and the vices of the enslaved and downtrodden were transmuted into virtues.

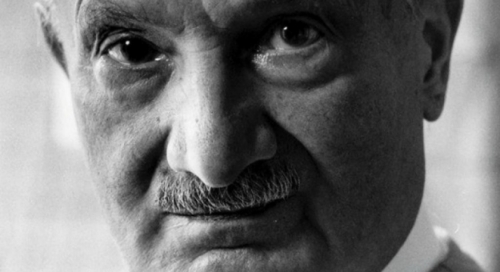

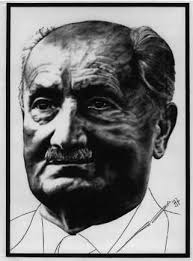

In Heidegger’s later terminology, Nietzsche and National Socialism were both “humanistic,” premised on the idea that the human mind creates culture, whereas in fact culture creates the human mind. No genuine belief can be chosen. It has to seize us. This is one of the senses of Heidegger’s later concept of Ereignis, often translated “the event of appropriation”: the beginning of a new historical epoch seizes and enthralls us. This is the meaning of Heidegger’s later claim that “Only a god can save us now” — as opposed to a philosopher-dictator.

In Heidegger’s later terminology, Nietzsche and National Socialism were both “humanistic,” premised on the idea that the human mind creates culture, whereas in fact culture creates the human mind. No genuine belief can be chosen. It has to seize us. This is one of the senses of Heidegger’s later concept of Ereignis, often translated “the event of appropriation”: the beginning of a new historical epoch seizes and enthralls us. This is the meaning of Heidegger’s later claim that “Only a god can save us now” — as opposed to a philosopher-dictator. Beiner is even more blatant in his advocacy of self-censorship in Heidegger’s case:

Beiner is even more blatant in his advocacy of self-censorship in Heidegger’s case:

Dans cette optique, la résistance autochtone peut mener une multitude d’actions non-violentes : blocages momentanés de certains nœuds routiers, autoroutiers ou ferroviaires ; résistance fiscale ; boycott des élections ; lobbying ; constitution de ZAD identitaires ; interpellation d’élus républicains ; sit-in ; occupation d’écoles ; manifestations ; harcèlement ; etc. Il n’y a de limites que notre imagination… et l’étendue du Grand Rassemblement, c’est-à-dire des forces disponibles.

Dans cette optique, la résistance autochtone peut mener une multitude d’actions non-violentes : blocages momentanés de certains nœuds routiers, autoroutiers ou ferroviaires ; résistance fiscale ; boycott des élections ; lobbying ; constitution de ZAD identitaires ; interpellation d’élus républicains ; sit-in ; occupation d’écoles ; manifestations ; harcèlement ; etc. Il n’y a de limites que notre imagination… et l’étendue du Grand Rassemblement, c’est-à-dire des forces disponibles.

Ludwig Klages was a one-of-a-kind brilliant man who is firstly known for his graphology work. But it is his philosophical work especially which deserves our attention. In fact, Klages belongs to what used to be called Lebensphilopsohie, a term that applies to Nietzsche’s. One thing they share is this dionysiac view on life which is often called « biocentric » when applied to Klages’ philosophy. His anti-christianity is another common point with Friedrich Nietzsche, and the same goes for a genre of paganism, or pantheism, shared by both philosophers.

Ludwig Klages was a one-of-a-kind brilliant man who is firstly known for his graphology work. But it is his philosophical work especially which deserves our attention. In fact, Klages belongs to what used to be called Lebensphilopsohie, a term that applies to Nietzsche’s. One thing they share is this dionysiac view on life which is often called « biocentric » when applied to Klages’ philosophy. His anti-christianity is another common point with Friedrich Nietzsche, and the same goes for a genre of paganism, or pantheism, shared by both philosophers.

The Apollonian and the Dionysian are two cognitive states in which art appears as the power of nature in man.[6] Art for Nietzsche is fundamentally not an expression of culture, but is what Heidegger calls “eine Gestaltung des Willens zur Macht” a manifestation of the will to power. And since the will to power is the essence of being itself, art becomes “die Gestaltung des Seienden in Ganzen,” a manifestation of being as a whole.[7] This concept of the artist as a creator, and of the aspect of the creative process as the manifestation of the will, is a key component of much of Nietzsche’s thought – it is the artist, the creator who diligently scribes the new value tables. Taking this into accord, we must also allow for the possibility that Thus Spake Zarathustra opens the doors for a new form of artist, who rather than working with paint or clay, instead provides the Uebermensch, the artist that etches their social vision on the canvas of humanity itself. It is in the character of the Uebermensch that we see the unification of the Dionysian (instinct) and Apollonian (intellect) as the manifestation of the will to power, to which Nietzsche also attributes the following tautological value “The Will to Truth is the Will to Power”.[8] This statement can be interpreted as meaning that by attributing the will to instinct, truth exists as a naturally occurring phenomena – it exists independently of the intellect, which permits many different interpretations of the truth in its primordial state. The truth lies primarily in the will, the subconscious, and the original raw instinctual state that Nietzsche identified with Dionysus. In The Gay Science Nietzsche says:

The Apollonian and the Dionysian are two cognitive states in which art appears as the power of nature in man.[6] Art for Nietzsche is fundamentally not an expression of culture, but is what Heidegger calls “eine Gestaltung des Willens zur Macht” a manifestation of the will to power. And since the will to power is the essence of being itself, art becomes “die Gestaltung des Seienden in Ganzen,” a manifestation of being as a whole.[7] This concept of the artist as a creator, and of the aspect of the creative process as the manifestation of the will, is a key component of much of Nietzsche’s thought – it is the artist, the creator who diligently scribes the new value tables. Taking this into accord, we must also allow for the possibility that Thus Spake Zarathustra opens the doors for a new form of artist, who rather than working with paint or clay, instead provides the Uebermensch, the artist that etches their social vision on the canvas of humanity itself. It is in the character of the Uebermensch that we see the unification of the Dionysian (instinct) and Apollonian (intellect) as the manifestation of the will to power, to which Nietzsche also attributes the following tautological value “The Will to Truth is the Will to Power”.[8] This statement can be interpreted as meaning that by attributing the will to instinct, truth exists as a naturally occurring phenomena – it exists independently of the intellect, which permits many different interpretations of the truth in its primordial state. The truth lies primarily in the will, the subconscious, and the original raw instinctual state that Nietzsche identified with Dionysus. In The Gay Science Nietzsche says: